Cancer presents a considerable challenge in medical

research due to its diversity and breadth. The proposal of cancer

hallmarks attempts to convert the complexity of cancer into a set

of provisional basic principles, which can help researchers

understand the mechanisms underlying cancer development more

comprehensively and logically. Cancer hallmarks are a set of

capabilities acquired by human cells as they progress from a normal

to a proliferative state, and are key to the malignant development

of tumors (1). The tumor

microenvironment (TME) is considered to carry out an important role

in tumorigenesis and malignant progression. The TME is a dynamic

environment that includes all non-cancerous and non-cellular

components of a tumor, such as fibroblasts, immune cells, the

extracellular matrix (ECM) and various secreted factors such as

IL-6 and IFN-γ (2). Among these

components (POSTN), a matricellular protein initially identified in

bone and periodontal ligaments, has emerged as a multifunctional

regulator in both physiological and pathological contexts (3). POSTN was initially discovered in

1993 (4), and numerous

associated studies have since been conducted (5-11). Initially, POSTN was reported to

be expressed minimally or not at all in the vast majority of mature

tissues but, highly expressed in the context of disease states such

as cancer, inflammation and fibrosis (12,13). Additionally, POSTN regulates the

development and maturation of fibrous-rich embryonic tissues, such

as heart valves and other periodontal ligaments (14,15).

In tumors, POSTN is a key player in tumor hallmarks

such as proliferation, metastasis and immune evasion (12). POSTN achieves this through

interactions with integrins and the activation of underlying

downstream signaling pathways (1). Despite growing evidence associating

POSTN with diverse cancer hallmarks, its isoform-specific

functions, regulatory mechanisms within heterogeneous TME

components and therapeutic potential remain incompletely

characterized (16-22). An increasing number of

preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated the potential of

POSTN in oncogenic mechanisms and as a biomarker (12,23-28). The present review primarily

focuses on the latest research on the functional diversity of POSTN

and its role in the tumor niche, which provides insights into

therapeutic strategies.

Early studies of POSTN date back to 1993, when a

gene was identified that encodes the 811 amino acid residue

osteoblast-specific factor 2, later renamed as POSTN (4,29-31). The human POSTN gene, located on

chromosome 13, spans 36,262 bp, contains 24 exons and encodes a

protein of 836 amino acids (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/10631).

Selective splicing is a tightly regulated process

that contributes to the high complexity of the multicellular

eukaryotic transcriptome at the protein level. Various studies have

revealed that in several species, there is alternative splicing of

the POSTN gene in either insertion or deletion patterns (4,32-34), In humans, exons 17, 18, 19 and 21

of the POSTN gene are selectively spliced, resulting in a variety

of isoforms. Moreover, other isoforms of the POSTN gene, including

10 variants of unknown function, have also been discovered in

various types of cancer such as renal cell carcinoma and non-small

cell lung cancer (32,35). Among the physiologically

expressed POSTN isoforms, PN4 (POSTN lacking exons 17 and 21) is

ubiquitously expressed and predominant (34). Several studies have discovered

new isoforms and explored their possible roles (18,36-41). Additionally, POSTN3 containing

exon 17 and 21 (but not containing exon 12) has been shown to

promote the growth and metastasis of breast cancer tumors through

alternative splicing (34).

Similarly, although POSTN is a suppressor in bladder cancer, POSTN

variant I, which is highly expressed in bladder cancer, does not

exhibit a suppressive effect (42).

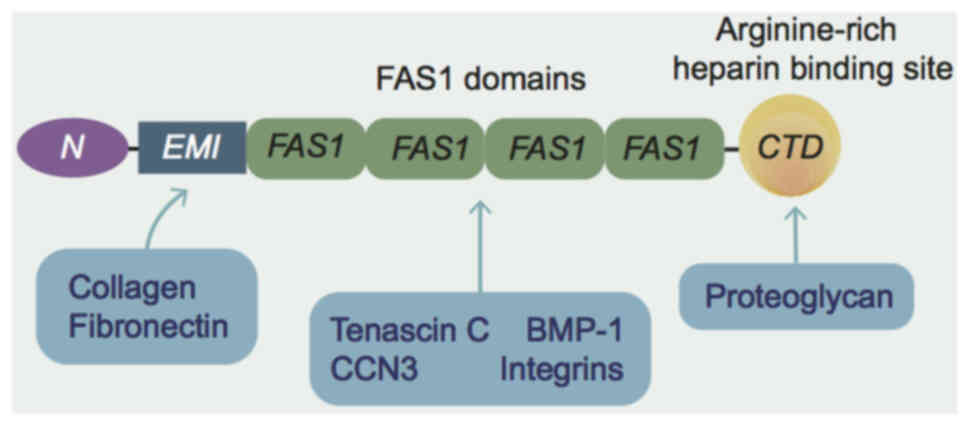

POSTN is a disulfide-linked 90 kDa protein secreted

by osteoblasts and osteoclast-like cell lines (8). The protein consists of six

structural domains, including a cysteine-rich Egf-like module

containing Mucin-like hormone receptor-like structural domain, four

tandemly repeated FAS-1 structural domains and a hydrophilic

C-terminal structural domain (4)

(Fig. 1). The four-repeat

fasciclin structural domain has homology to insect proteins, based

on which the Fas1 structural domain characterizes it as a member of

the fasciclin 1 family. The FAS-1 structural domain has been shown

to interact with fibronectin (43), tenascin-C (44), bone morphogenetic protein-1

(45) and Cellular Communication

Network factor 3 (46). As an

ECM protein, POSTN relies largely on the FAS-1 structural domain to

bind to integrins and thus mediate various signaling pathways

(47). The C-terminal structural

domain, conversely, lacks known functional domains and is

intrinsically disordered (48).

POSTN is a matrix protein that is named after its

preferential expression in mouse periosteum and periodontal

ligaments. The expression of POSTN in these tissues is regulated by

mechanical stresses (49).

Physiologically expressed in collagen-rich connective tissues (such

as, cardiac valves, tendons and lungs), POSTN becomes active during

fetal development but is predominantly absent or minimally

expressed in the majority of adult tissues. It regulates tissue

maturation in embryonic structures such as the periosteum,

periodontal ligaments, liver, kidneys and ureters (14,50). Notably, POSTN drives fetal

cardiomyocyte lineage differentiation and heart valve maturation

(15), positioning it as a

potential biomarker for prenatal non-invasive screening of

congenital heart defects. Additionally, elevated POSTN expression

occurs in stem cell niches of adult organs, including the mammary

gland, intestine, spleen, bone and skin, suggesting

context-dependent roles in tissue homeostasis.

POSTN and its variants are differentially expressed

and are upregulated in inflammation, sites of injury and tumors

(18,51,52). POSTN contributes to pathological

processes such as allergy, inflammation, tissue remodeling,

regeneration, fibrosis and tumor progression. For example, POSTN is

a valuable biomarker of type 2 inflammation (a specific type of

immune response that is primarily mediated by type 2 helper T

cells)as a downstream molecule of IL-4 and IL-13, which has been

closely associated with the pathogenesis of asthma (53), chronic rhinosinusitis (54), allergic dermatitis (55) and pulmonary fibrosis (56). In addition, POSTN is also

involved in the development of myocardial infarction through its

response to TGF-β in inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver and

kidney disease (57), as well as

through its interaction with other ECM proteins (for example,

fibronectin, heparin and Tenascin-C) (58).

POSTN is expressed in several primary types of

cancer, including breast, bladder, colon, pancreatic and ovarian

cancer, as well as non-small cell lung and oral cancer (13,59) (Table I). For example, POSTN is

expressed at low levels in normal breast tissue, but high

expression of POSTN is often detected in breast cancer, with the

average expression level of the periosteal protein being 20-fold

higher compared with the baseline expression level defined by gene

array data for normal breast tissue (60). POSTN is also abnormally elevated

in metastatic cancer types, most notably liver metastases from

colorectal cancer, which has been associated with a supportive

fibrotic microenvironment promoted by both POSTN and TGF-β1

(61). However, the upregulation

of POSTN expression in tumors is not universal. For example, POSTN

is not expressed in hematologic malignancies such as leukemia and

myeloma (62).

Cancer development is a multistep process initiated

by oncogenic mutations that confer clonal advantage, ultimately

driven by genomic instability (63). This progression is marked by

acquired hallmarks including sustained proliferation, evasion of

growth suppression, resistance to apoptosis, replicative

immortality, angiogenesis, invasion/metastasis, metabolic

reprogramming and immune escape. Emerging features such as

phenotypic plasticity, epigenetic dysregulation, microbiome

interactions and senescence further define tumorigenesis (1). Notably, POSTN overexpression and

its alternatively spliced isoforms (such as, in renal, lung, breast

and gastrointestinal cancer) regulate multiple oncogenic processes

(13,40,64).

Cell proliferation is a process regulated by the

synergistic action of mitogenic growth-promoting and

antiproliferative signals (65).

POSTN has been shown to induce proliferation in a variety of

tumors. For example, POSTN can interact with the classical Wnt

signaling pathway to promote colorectal tumorigenesis (66) and proliferation in neuroblastoma

(67). POSTN from tumor stromal

fibroblasts promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by activating

YAP/TAZ through the Integrin-focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-Src

signaling pathway (19). POSTN

also promotes gastric cancer proliferation studies revealed that

POSTN enhances the proliferation of OCUM-2MLN and OCUM-12 diffuse

gastric cancer cell lines in vitro through activation of

ERK, intuitively, tumor growth in POSTN (−/−) mice is markedly

slower compared with that in wild-type mice (68). POSTN-promoted proliferation of

tumor cells is also exemplified in carcinomas such as the A549 lung

carcinoma cell line (69),

triple-negative breast carcinoma (17) and melanoma (70).

Besides promoting cell proliferation, POSTN also

carries out a key role in activating invasion and metastasis. Tumor

invasion and metastasis are an inefficient process requiring the

overcoming of several rate-limiting steps, the occurrence of which

often portends malignancy and a poor prognosis (71). Due to the heterogeneity of tumor

cells, tumor invasion and metastasis are difficult to treat and

remain one of the major challenges in the field of tumor therapy

(72).

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), initially

identified during embryogenesis, is now recognized as a key driver

of developmental processes, disease progression and tumor invasion

(73). POSTN is involved in

tumor invasion and metastasis by regulating EMT, the classical way

of which is that POSTN binds to integrins and activates Akt/PKB and

FAK-mediated signaling pathways (13). Studies demonstrate that stromal

POSTN expression in ovarian cancer promotes tumor invasion and

metastasis via PI3K/Akt pathway activation, mechanistically driving

EMT (27,74,75). POSTN activates STAT3 signaling to

modulate EMT markers such as caveolin-1 and angiogenesis-related

genes such as HIF-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor-A

(VEGF-A), with its knockdown shown to reverse glioblastoma stem

cell (GSC) resistance to anti-VEGF-A therapy (76). POSTN has also been demonstrated

to induce EMT in hepatoblastoma (77) and prostate cancer (78). Moreover, POSTN can inhibit

specific targeted microRNAs (miRNAs) involved in the regulation of

EMT. miRNAs are small endogenous RNAs that post-transcriptionally

regulate gene expression and may target up to one-third of human

mRNAs (79). Song et al

(80) found that the POSTN gene

was markedly upregulated in the gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901

treated with miR-148b mimic, which suggests the possible

involvement of POSTN in the pathways related to the development and

progression of gastric cancer. In lung cancer, POSTN promotes EMT

through the MAPK/miR-381 axis (81).

POSTN promotes cell motility to promote tumor

metastasis. It was demonstrated that secretion of POSTN by von

Hippel-Lindau oncogene non-expressing (VHL-) cells enhanced the

motility of VHL-WT cells and promoted vascular escape in clear cell

renal cell carcinoma tumor cells (82). In a study on colorectal cancer,

POSTN was found to activate FAK and AKT or STAT3, accelerating

metastasis and activating migration of tumor and stromal cells

through stromal remodeling capacity (83). These studies suggest that POSTN

carries out an important role in the development of the TME and

that increased expression of POSTN in the stroma is somewhat

indicative of tumor stage and prognosis (84).

Interestingly, POSTN largely promotes tumor-invasive

metastasis, yet it is regarded as a tumor suppressor in bladder

cancer (85). This may be

associated with the selective sharing of POSTN. Of the two splicing

variations of POSTN (variants I and II) isolated from bladder

cancer, Variant II has key domains that interact with matrix

proteins such as integrins, inhibiting cancer cell invasion and

metastasis. While Variant I, lacking certain exons, has a changed

structure that weakens these interactions, losing its inhibitory

function and potentially promoting cancer progression (42).

Tumor angiogenesis enables nutrient and oxygen

delivery to growing malignancies, with aberrant vascular features,

such as disorganized architecture, sinusoidal vessel formation and

functional heterogeneity, distinguishing tumor vasculature from

normal tissues (86). VEGF is a

central driver of angiogenesis, which binds tyrosine kinase

receptors Flt-1 and Flk-1/KDR to initiate signaling. POSTN has been

identified as a pro-angiogenic factor that facilitates tumor

neovascularization via 'vascular co-option', exploiting

pre-existing vessels in adjacent healthy tissues (87). When the tumor volume is >2

mm3, increased expression of POSTN enhances the

resistance of cancer cells to hypoxic conditions (88). For instance, in colorectal

cancer, POSTN activates the Akt/PKB pathway to increase endothelial

cell survival and vascular proliferation, correlating with

metastasis and serving as a prognostic marker (89). Similarly, ovarian cancer studies

reveal that POSTN overexpression drives angiogenesis and metastatic

spread (11,90-92). Mechanistically, POSTN upregulates

Flk-1/KDR expression in endothelial cells via integrin αvβ3-FAK

signaling, a pathway associated with breast cancer progression

(22,60).

POSTN also promotes lymphangiogenesis, a key step in

metastatic dissemination. Gillot et al (93) demonstrated that POSTN enhances

VEGF-C-mediated lymphangiogenesis and primes lymph nodes for

metastatic colonization. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(HNSCC), POSTN drives lymphatic remodeling through dual mechanisms:

Indirect upregulation of VEGF-C mRNA and direct activation of

Src/Akt pathways. This aligns with observed associations between

POSTN-overexpressing xenografts and lymphatic involvement in HNSCC

(94). Collectively, POSTN

orchestrates tumor vascularization and lymphatic network expansion,

fostering metastatic efficiency.

Apoptosis is a regulated form of programmed cell

death, which carries out dual roles in tumor biology. Its

dysregulation contributes to tumor progression, therapy resistance

and metabolic reprogramming by enabling uncontrolled proliferation

or insufficient apoptosis (95).

Apoptosis also interacts with tumor metabolism to collectively

drive malignancy (96). Notably,

apoptosis can paradoxically support tumor survival through

microenvironmental interactions (97). Emerging concepts such as

pan-apoptosis (combined apoptosis-necroptosis) further highlight

the complexity of apoptosis regulation in cancer immunity (98).

ECM protein POSTN enhances tumor cell survival under

stress conditions (hypoxia, nutrient deprivation). Mechanistically,

POSTN activates β4 integrin/PI3K and Akt/PKB pathways to suppress

apoptosis in pancreatic, colorectal and non-small cell lung cancer

(88,89,99). In hypoxic pancreatic tumors,

POSTN drives a pathological cycle: Hypoxia induces stellate cells

to secrete POSTN, which sustains fibrosis and cellular viability

while exacerbating hypoxia (100). This ECM-mediated adaptation

enables tumor persistence across multiple cancer types by

counteracting environmental stressors and death signals.

Immunomodulation carries out an important role in

tumor development and signaling between POSTN and immune cells can

take place, thus carrying out a role in the immune escape of

tumors. A study noted that GSCs in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM)

secrete POSTN, which can recruit M2-type tumor-associated

macrophages (TAMs) to support GBM growth (101). Similarly, POSTN can promote

ovarian cancer metastasis by enhancing M2 macrophages and

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through integrin-mediated

NF-κB and TGF-β2 signaling (74). Wang et al (102) discovered that POSTN+ CAFs can

recruit secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1)+ macrophages and trigger

an increase in SPP1 expression via the IL-6/STAT3 signaling

pathway, thereby enhancing therapeutic resistance in hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC). In addition, a recent study have shown that

thyroid tumor cells and CAFs can promote tumor development through

crosstalk between IL-4 and POSTN (103). The aforementioned studies may

suggest new targets for cancer inhibition.

Cell senescence is a stress-induced stable growth

arrest that has been regarded as a passive bystander in the

cessation of proliferation. However, research over the past decade

suggests that senescence also serves as the foundation for tissue

development and function (104-107). For tumors, cellular senescence

has two opposing functions. Firstly, senescence halts the cell

cycle, thereby preventing the formation of malignant tumor cells

and promoting tissue regeneration and repair (108). Secondly, senescent cells

present in the TME can induce persistent inflammatory states and

reprogram the TME (109)

through the production of the senescence-associated secretory

phenotype, thereby promoting tumor growth, metastasis and drug

resistance (110). There is

currently evidence suggesting an association between POSTN and

cellular senescence, warranting further investigation. Zhu et

al (111) experiments

indicate that POSTN may promote nucleus pulposus cell senescence

and ECM metabolism by activating the NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathways, carrying out a notable role in the progression

of disc degeneration. Overexpression of POSTN simultaneously leads

to fibrosis and senescence of cardiomyocytes (112). Similarly, POSTN has been

revealed to promote kidney aging by participating in fibrosis and

lipid metabolism (113). Huang

et al (114) used

RNA-Sequencing technology to examine gene expression changes in

primary skin fibroblasts from healthy controls and patients with

pyrroloquinoline quinone reductase 1 (PYCR1) mutations, and found

that POSTN was one of the most downregulated candidate genes. To

the best of our knowledge, although no published articles have yet

described how POSTN influences cancer development through aging,

the aforementioned discussions provide potential avenues for future

research in this direction.

Epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming are closely

related and mutually regulate each other, driving immune escape or

hindering immune surveillance in certain cases, and carrying out an

important role in tumor progression (115). CAFs are recognized as key

components of the TME, which are stable at the genomic level but

differ considerably from normal stromal precursors (116). The transformation of normal

fibroblasts into CAFs involves extensive methylation changes, which

can be induced by various factors such as TGFβ and pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as leukemia inhibitory factor (117,118). The epigenetic modifications in

CAFs not only activate and maintain their pro-invasive phenotype

(118) but also enhances

glycolysis in tumor metabolism. Becker et al (119) demonstrated that the epigenetic

reprogramming of CAFs disrupts glucose metabolism and promotes

breast cancer progression. Additionally, studies have elucidated

the promotional role of the epigenetics of CAFs in prostate cancer

(120) and bladder urothelial

carcinoma (121). POSTN carries

out an important role as a marker of CAFs in this process. Han

et al (122) reported

that POSTN is one of the DNA methylation biomarkers of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma and patients with high POSTN expression

have shorter overall survival times. The methylation of POSTN is

also associated with the molecular mechanisms of important pathways

associated with glioblastoma formation and patient overall survival

(123).

POSTN is a multifunctional, pleiotropic molecule in

cancer, with its effects exhibiting high context-dependence. It

serves as a potent 'oncogenic factor' while also potentially

assuming the complex role of a 'potential collaborator' under

specific conditions, with the underlying core being the dynamic

changes in TME (124,125). First, cancer of different

tissue origins and molecular subtypes exhibit considerable

differences in their TME. POSTN can be secreted by various cell

types (such as, tumor cells and CAFs) and its effects may depend on

the source cells as well as the specific receptors and downstream

signaling pathways with which it interacts. POSTN typically

promotes immune suppression; however, in certain contexts (such as

specific immunotherapy combinations), the immune cells it recruits

may unexpectedly alter the balance of the TME, potentially

producing effects favorable to therapeutic response. This is not a

direct 'beneficial' effect but an indirect outcome of specific

contextual factors (126).

Additionally, different splice variants of POSTN can have opposed

effects, as demonstrated in bladder cancer (85).

Cancer is driven by the accumulation of mutations in

cancerous cells but is not exclusively genetically determined. The

majority of cancer types (90-95%) occur in close association with

the environmental exposures and lifestyle choices of an individual,

while genetic factors account for only a small proportion (5-10%)

of all cancer cases (127).

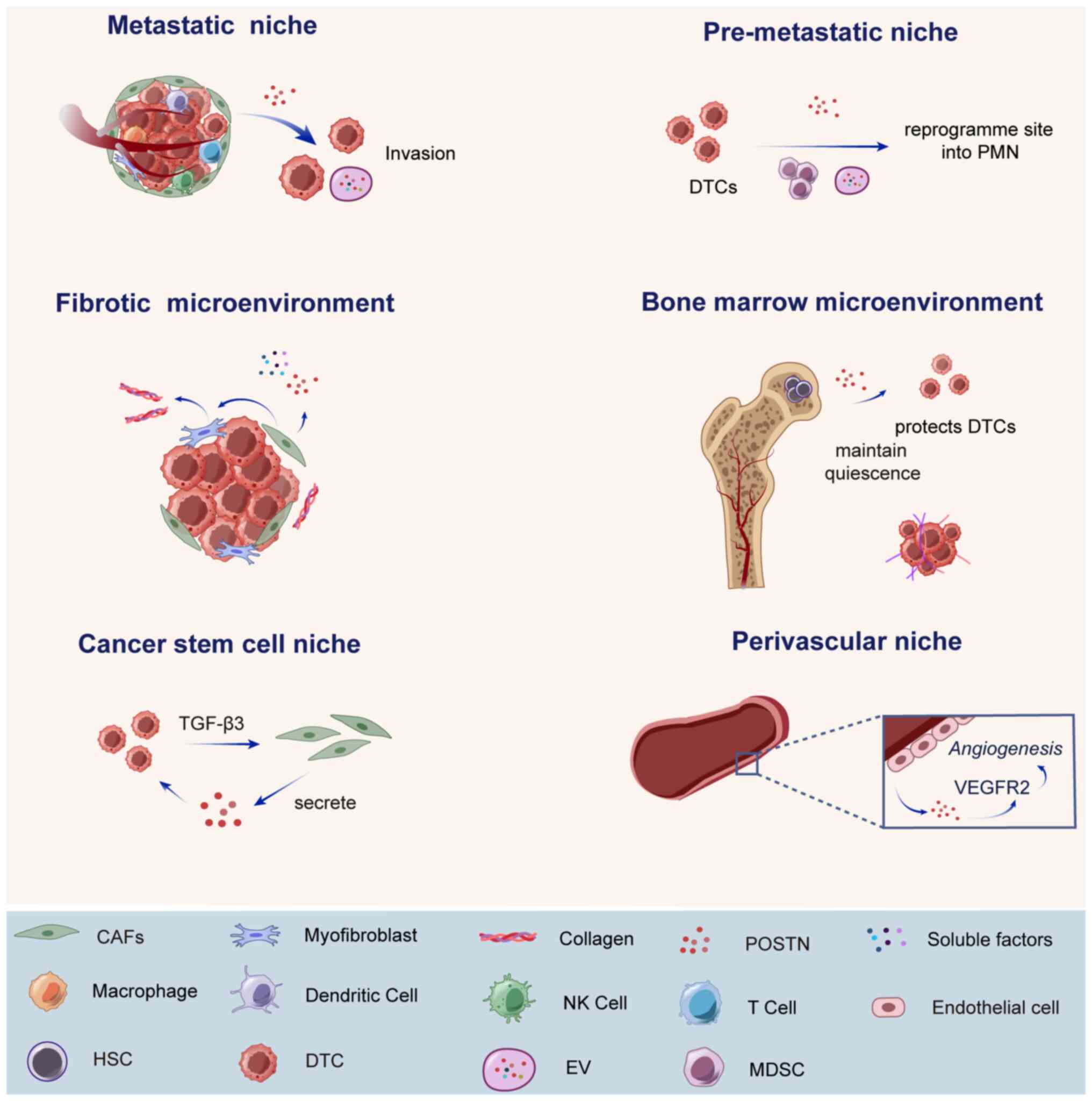

TME refers to all the non-cancerous cells and

non-cellular components in a tumor, which can be regarded as a

special ecological niche where tumor cells are located. The

cellular components include fibroblasts, adipocytes, endothelial

cells, infiltrating immune cells such as lymphocytes and dendritic

cells; while the non-cellular components include ECM and soluble

components such as hormones, growth factors or cytokines (12). These components were previously

considered 'innocent bystanders', but several studies have revealed

that constant, reciprocal and dynamic interactions between tumor

cells and the TME (2,128) are key in the cancer process

(129) (Fig. 2). Current evidence suggests that

POSTN activates key downstream signaling pathways by interacting

with its receptor integrin, remodels the ECM by interacting with

other ECM proteins [such as type I collagen, fibronectin, tenascin

C and thrombospondin 1 (TSP-10)] (44) and remodels TME by cross-talking

with other signaling molecules and recruiting inflammatory and

immune cells (3).

Tumor metastasis is an inefficient process where the

majority of disseminated cells die, with only rare cells

successfully colonizing distant sites. Emerging evidence implicates

cancer stem cells (CSCs) as key drivers of metastasis, facilitated

by interactions with the metastatic niche (130-133). Stromal fibroblast-derived

POSTN, a component of normal stem cell niches, mediates CSC-niche

crosstalk, as demonstrated by Malanchi et al (134). In metastatic tissues, POSTN is

primarily secreted by CAFs, which are activated by paracrine or

autocrine signals to coordinate metastasis through direct

interactions with tumor cells and stromal components (135). For example, in colorectal

cancer, POSTN overexpression in hepatic metastatic niches promotes

tumor cell survival, angiogenesis and metastasis via the Akt/PKB

pathway (89). Similarly,

cervical squamous cell carcinoma studies reveal that POSTN+ CAFs

disrupt lymphatic endothelial barriers by activating

integrin-FAK/Src-VE-calmodulin signaling, facilitating

dissemination (136-138). In ovarian cancer, POSTN drives

metastasis through autocrine NF-κB/TGF-β2 activation in tumor cells

and by recruiting M2 macrophages and CAFs. Stromal POSTN also

enhances metastatic infiltration in skin and head-neck squamous

carcinomas (74). Furthermore,

POSTN can synergize with TNC, for example, POSTN may aggregate Wnt

for stem cells, while TNC may enhance the response of these cells

to Wnt and Notch (139) are

'two sides of the same metastatic ecological niche'.

CSCs or tumor-initiating cells, drive tumor

heterogeneity through self-renewal, clonal initiation and long-term

repopulation capabilities. The CSC niche preserves these

properties, shields CSCs from immune surveillance and facilitates

metastasis (132). As

highlighted by Malanchi et al (134), CD90+CD24+ breast CSCs from

primary tumors metastasize to the lungs and activate CAFs to

secrete POSTN. This stromal POSTN recruits Wnt ligands into CSCs,

amplifying Wnt signaling to fuel CSC expansion and metastatic

colonization. In basal-like breast carcinoma, POSTN maintains CSC

traits and mesenchymal phenotypes by regulating NF-κB-dependent

cytokines (IL4 and IL8) via ERK signaling, thereby promoting

metastasis (140). Similarly,

ovarian cancer studies show that POSTN enhances CSC stemness,

increasing invasiveness, therapy resistance and recurrence

(20,27,74,90,141). In colon cancer, high Wnt

activity defines CSC stemness (142) and POSTN interacts with Wnt

ligands (Wnt1/Wnt3A) in colon CSCs, suggesting its role in

reinforcing stemness (143).

Further supporting this paradigm, Chen et al (144) identified a POSTN/TGF-β1

positive feedback loop in HCC. Through analysis of 110 HCC patient

tissues and xenograft models, this study demonstrated that

POSTN/TGF-β1 activates AP-2α transcription to sustain HCC CSC

stemness and accelerate malignancy.

Perivascular niche is key for maintaining both

hematopoietic stem cells and CSCs, serving as a dynamic hub in

cancer evolution (83). This

niche context-dependently regulates tumor dormancy, metastatic

spread, stemness and immune evasion, shaping tumor progression

(145). Tumor cells exploit

this niche to invade blood vessels (extravasation), a process

involving endothelial cell contractility (via myosin) and

mechanical interactions with the subendothelial matrix (146). However, disseminated tumor

cells (DTCs) often face suppression in secondary organs, with only

a subset surviving or entering dormancy. DTC 'awakening' represents

a key rate-limiting step for metastasis. Stable vasculature

suppresses proliferation through stromal TSP-1, while sprouting neo

vessels exhibit pro-metastatic properties: Their endothelial cells

upregulate POSTN, tenascin-C, fibronectin and TGF-β1, creating a

microenvironment that drives tumor reactivation (3,147-149).

The perivascular niche also modulates immunity by

facilitating immune cell infiltration. Perivascular TAMs promote

angiogenesis, immunosuppression and tumor survival (150). POSTN recruits TAMs to remodel

this niche, as seen in GBM, where GSCs secrete POSTN to attract and

polarize TAMs toward the pro-tumor M2 subtype. This POSTN-mediated

crosstalk sustains GSC-TAM clustering in perivascular regions,

fostering therapy resistance and recurrence (101,151,152). These dual roles, structural

support for metastasis and immunomodulation, highlight the

perivascular niche as a promising therapeutic target.

PMN, consisting of distinct resident cell types, ECM

components and infiltrating cell populations, is a microenvironment

induced by tumors in distant tissues that can provide a conducive

environment for the proliferation of incoming tumor cells (153). It is currently considered that

distant sites can be reprogrammed into the PMN by extracellular

vesicles (EVs) carrying tumor-secreted factors. Potential

mechanisms include enhanced angiogenesis and vascular remodeling,

stromal remodeling, inhibitory effects of EVs on immune cells and

alteration of the metabolic milieu. Formation of PMN is an

integrative process that extends from the local to the systemic

level (146,154,155).

POSTN can be induced by tumor products that reach

distant tissues first and participate in pre-metastatic ecological

niche formation (134). A study

using lung fibroblasts isolated from the lung tissues of C5BL/6 J

mice revealed that CAF EVs induced pre-metastatic ecotone formation

in the SACC lungs of mice and demonstrated more robust matrix

remodeling than SACC EVs. This may be due to POSTN activation of

the TGF-β signaling pathway in lung fibroblasts (156). Previous studies reveal

multifaceted roles of POSTN in pre-metastatic niche formation:

Tumor-derived EVs deliver lncRNA MALAT1 to mediate M2 macrophage

polarization via the POSTN/Hippo/YAP axis in triple-negative breast

cancer (157), while colorectal

cancer EVs carrying ITGBL1 reprogram fibroblasts to prime

metastatic sites (158). POSTN

facilitates immunosuppression by engaging myeloid-derived

suppressor cells in tumor immune evasion (159) and promotes niche establishment

through trauma-induced secretion in melanoma (160). Exosome-mediated POSTN transfer

modifies distant tissue microenvironments (99), with elevated exosomal POSTN

levels in thyroid cancer patients directly accelerating progression

via niche remodeling (161).

Formation of a fibrotic microenvironment is

associated with a series of events, including tissue injury,

inflammation, myofibroblast differentiation and ultimately the

excessive deposition of ECM components. The ECM comprises fibrous

proteins and glycoproteins, forming a dynamic 3D structure that

regulates cell adhesion, migration, tissue repair and disease

processes through mechanotransduction (162,163). POSTN promotes fibrosis in

pathological and cancer contexts, by interacting with soluble

factors to induce myofibroblast differentiation (61,164). Activated myofibroblasts secrete

a large amount of ECM components, primarily collagen, elastin and

glycosaminoglycans (165).

The formation of fibrotic niches is key for tumor

metastasis and the growth of tumors characterized by

fibroproliferation. POSTN is one of the markers of fibrotic niches

and it primarily functions through interactions with key signaling

pathways such as TGF-β1 (61)

and Wnt/β-catenin (166).

Elevated POSTN levels in melanoma lung metastases associate with

bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis progression (167). In uterine fibroids, POSTN acts

as both a biomarker and a therapeutic target by stimulating

collagen overproduction and myometrial cell transformation

(168,169). Additionally,

metastasis-associated macrophages activate hepatic stellate cells

via granulin secretion, generating POSTN-producing myofibroblasts

that remodel liver stroma for tumor growth (170).

Bone is a frequent metastatic site for solid tumors

(for example, breast, prostate and lung cancer) (171,172). Bone marrow, a semi-solid tissue

within bone cavities, facilitates hematopoiesis via hematopoietic

stem cells and comprises cellular components such as mesenchymal

stromal cells, osteoblasts and immune cells, as well as

non-cellular elements including cytokines and growth factors

(173,174). This microenvironment protects

DTCs during colonization, dormancy and growth, and contributes to

hematologic malignancies such as leukemia and myeloma (175,176).

POSTN is associated with bone metastasis. In breast

cancer, BMSC-derived POSTN promotes bone metastasis, with murine

models showing an 8-fold POSTN increase at metastasis sites

compared with controls (177,178). Contrastingly, C-terminal intact

periosteal protein (iPTN) levels decrease in breast cancer bone

metastases due to histone K cleavage, suggesting iPTN as a

potential biomarker for bone recurrence detection (179). POSTN also drives HNSCC

progression via BMSC-induced PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway activation

(180). In multiple myeloma,

elevated POSTN levels are associated with advanced disease

severity, such as International Staging System stage 3 (181) and with dysregulation of bone

metabolism, including an inverse relationship with bone formation

markers and a positive correlation with bone resorption markers

(182). Additionally, POSTN

facilitates prostate cancer bone metastasis via integrin-mediated

interactions with osteoblasts and tumor cells (183) and supports B-cell Acute

Lymphoblastic Leukemia cell proliferation in the bone marrow niche

(184).

Although extensive basic research has confirmed

that POSTN carries a central role in various pathological processes

(185-187), its successful translation from

a basic molecular marker to a clinically useful tool remains

challenging. Currently, the practical application value of POSTN as

a clinical biomarker is still under investigation, and there

remains a notable gap between its potential applications and

clinical practice.

Since the pathological expression levels of POSTN

are markedly higher when compared with normal expression levels

(64,188), POSTN has potential as a

diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for diseases. Since the

upregulation of POSTN is not specific to any particular disease,

this may limit its application as a standalone diagnostic

biomarker. Currently, research is focused on combining POSTN with

other biomarkers to develop more precise diagnostic and prognostic

prediction models. A study demonstrated that the combination of

plasma POSTN and CA19.9 considerably improved the sensitivity,

specificity and AUC for diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma compared with

using a single marker, reaching 87 and 91%, and 0.94, respectively

(plasma POSTN: 78 and 85%, and 0.86; CA19.9: 67 and 90%, and 0.86)

(189). Jia et al

(25) demonstrated that, to

distinguish healthy controls from locally advanced BCa, POSTN

exhibited the highest AUC (AUCPOSTN=0.72, AUCCA153=0.57 and

AUCCEA=0.62), and the AUC of CA153 and CEA were markedly improved

when used in combination with POSTN. Furthermore, multiple studies

have demonstrated that elevated serum POSTN levels are associated

with worse overall survival and progression-free survival (7,190-193). In summary, the potential role

of POSTN as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker holds clinical

value.

With the advent of the era of precision medicine,

accurate identification of subtypes has become increasingly

important. In various types of tumors, the 'POSTN+' subtype is

typically associated with features such as stromal proliferation,

EM and TM characteristics (17,102,126). Patients with this subtype often

exhibit greater invasiveness, increased metastasis risk and worse

response rates to conventional chemotherapy. By contrast, the

'POSTN-' subtype is associated with relatively improved prognosis.

Zhang et al (141)

revealed that the stroma markedly contributes to the molecular

classification of the mesenchymal subtype in high-grade serous

ovarian cancer, with POSTN being one of the genes predominantly

expressed in the stroma. In osteosarcoma, POSTN-positive expression

is notably associated with histological subtype (P=0.000), Enneking

staging (P=0.027) and tumor size (P=0.009) (194).

In invasive basal cell carcinoma (BBC), the two

upregulated genes POSTN and WISP1 were validated at the protein

level as being associated with invasive BCC (195). This subtype classification lays

the foundation for developing precision strategies. A molecular

typing kit based on POSTN expression levels could be developed to

identify high-risk patient groups, guiding more intensive follow-up

and early intervention. In terms of treatment, it provides a basis

for achieving stratified therapy. Patients with high POSTN

expression in this subtype may be the optimal candidate population

for targeted therapies targeting the POSTN pathway itself or its

downstream effector molecules or for immunotherapies targeting the

immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Additionally, new CAF subtypes can be defined based

on POSTN expression levels. Wang et al (102) recently found that high

infiltration of POSTN+ CAFs and SPP1+ macrophages is associated

with resistance to immunotherapy. For example, a study identified

five CAF subtypes in gastric cancer, revealing that the CAF_0

subtype was highly associated with poor prognosis, with POSTN being

the most notable marker gene for this subtype (196). These findings suggest that

targeting specific CAF subpopulations may have potential benefits

for improving clinical responses to immunotherapy.

Targeted therapy for POSTN has progressed from the

proof-of-concept stage to practical application. In preclinical

studies, various targeted strategies have shown great promise. For

example, PNX-001 (a humanized anti-POSTN monoclonal antibody)

effectively blocks the interaction between POSTN and integrin in

preclinical models, inhibits tumor growth and metastasis, and

enhances the delivery of chemotherapy drugs (197). Another neutralizing monoclonal

antibody targeting POSTN (MZ-1) has been shown to have a

considerable growth-inhibitory effect on a subgroup of invasive

ovarian tumors that overexpress POSTN (198). PNDA-3 (human osteopontin-3) is

a DNA aptamer that selectively binds to the FAS-1 domain of POSTN,

disrupting its interaction with its cell surface receptors αvβ3 and

αvβ5 integrins, thereby markedly reducing primary tumor growth and

distant metastasis (199,200).

Due to the increasing number of POSTN-related

diseases, several clinical trials are currently underway. However,

therapies targeting POSTN in the field of oncology remain at a

relatively early stage, with very limited publicly available

clinical data. Key future challenges include: Determining the

optimal treatment window, selecting appropriate biomarkers to

screen for patient populations likely to respond and exploring

combination strategies with other therapies (such as immune

checkpoint inhibitors, anti-angiogenic drugs) to overcome the

complexity of the TME.

Despite considerable progress in POSTN research,

there remain notable knowledge gaps and technical limitations in

this field, which hinder its clinical translation process. First,

there are conflicting data in the existing literature. In certain

types of cancer, high POSTN expression is associated with poor

prognosis [such as, breast cancer (13,128,130,139), glioblastoma (101,123), ovarian cancer (20,27,74,91,141) and liver cancer (13,62,71,89,193), but in other types of cancer

(201,202), such as estrogen

receptor-negative (ER-) or progesterone receptor-negative (PR-)

phenotypes of breast cancer (203), its expression levels show only

a modest association with clinical outcomes (203-205). These inconsistencies may stem

from methodological heterogeneity, differences in patient cohorts

and variations in the cellular origin and tissue localization of

POSTN within the TME. Typically, POSTN is present in the ECM, while

the main presence of POSTN in tumor tissues is in the cancer matrix

(206). Additionally, current

detection methods struggle to distinguish between different POSTN

splice variants, which may possess entirely different or even

opposing biological functions, potentially contributing to the data

inconsistencies (34). Current

research also faces notable technical limitations. The majority of

studies rely on static measurements from tissue biopsies, which

cannot capture the dynamic changes in POSTN expression or its

real-time functional role in treatment response and disease

progression. More importantly, complete inhibition of POSTN may

interfere with important physiological functions, leading to side

effects such as impaired wound healing, abnormal bone fibrosis or

cardiac dysfunction (64).

Although the role of periosteal proteins in promoting metastasis

and chemotherapy resistance has been well established, it remains

unclear how targeting periosteal proteins interacts with existing

treatment modalities, such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy or

radiotherapy, within the TME.

To overcome these challenges and drive further

development in this field, future research should establish unified

POSTN detection standards and conduct large-scale, multicenter

prospective cohort studies to systematically assess the predictive

and prognostic value of POSTN in different disease stages and

treatment settings. Additionally, novel dynamic imaging

technologies, such as molecular imaging probes capable of

non-invasively and real-time monitoring of POSTN expression and

functional activity within the body, should be actively developed.

In terms of treatment strategies, the focus should be on precision

interventions, including the design of inhibitors that can

specifically block pathological protein interactions (such as

integrin binding) without affecting physiological functions, the

development of drugs targeting disease-specific isoforms and the

exploration of prodrug strategies based on TME activation to

minimize off-target risks to normal tissues. Finally, any clinical

translation research must comprehensively assess the potential

long-term effects of inhibiting POSTN on the regenerative and

reparative functions of key organs such as bones, skin and the

heart during the preclinical stage to ensure treatment safety. By

adopting these recommendations, future research will be able to

more reliably evaluate the clinical efficacy of POSTN and design

safer, more effective targeted treatment strategies, ultimately

bridging the gap between basic research and clinical

application.

As an important matricellular protein, POSTN

carries out multifaceted roles in both physiological and

pathological processes, including embryonic development, allergic

inflammation, fibrotic diseases and tumorigenesis (12,64). Increasing evidence indicates that

POSTN can regulate various cancer hallmarks by interacting with

integrins and modulating key signaling pathways such as

Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt and TGF-β (27,49,51,61,74,111,166,168,180,188,207). The present review focuses on

the promoting effects of POSTN on tumor growth,

invasion-metastasis, angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis and immune

evasion. Considering the increasingly recognized role of TME, POSTN

also exerts considerable effects on niche regulation, particularly

in the maintenance of CSCs, remodeling of the ECM and

immune-suppressive reprogramming (102,135,140,144,208).

These findings suggest a promising therapeutic and

prognostic potential for targeting POSTN in tumor management. In

terms of cancer treatment, the main approaches include blocking the

POSTN signaling pathway and using POSTN inhibitors. Studies have

shown that Let-7f reduces angiogenesis mimicry in glioma cells by

inhibiting POSTN (209,210). DNA aptamers targeting POSTN

have been revealed to effectively inhibit the growth and metastasis

of breast and gastric cancer in mouse models (209). POSTN can also be combined with

immune checkpoint inhibitors to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of

colorectal tumors (211).

Moreover, selecting appropriate POSTN isoforms is important. For

instance, POSTN-203 may be a more promising target for glioma

because it is associated with low patient survival and contains

multiple predicted human leukocyte antigen-restricted epitopes

(40). POSTN can also serve as a

prognostic biomarker for gastrointestinal malignancies,

hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer (212), breast cancer, ovarian cancer

(20) and genitourinary cancer

(59).

Key knowledge gaps still exist, including the

functional heterogeneity of POSTN isoforms, the detailed mechanisms

of its molecular interactions and the potential off-target effects

of POSTN-targeted therapies. In summary, future research should

prioritize addressing these challenges to advance POSTN-based

diagnostics and therapeutics and ultimately improve the clinical

outcomes of cancer and associated pathologies.

Not applicable.

YX have made substantial contributions to the

conception of the present review, wrote the main manuscript text,

prepared Figs. 1 and 2, and reviewed the manuscript. LW made

substantial contributions to the conception of the present review

and reviewed the manuscript. Data authentication not applicable.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present work was supported by the Open Research Fund of

Hubei Province Key Laboratory of Precision Radiation Oncology

(grant no. 2024ZLJZFL003) and the Key Laboratory of Anesthesiology

and Resuscitation (Huazhong University of Science and Technology),

Ministry of Education (grant no. 2024MZFS010), which are awarded to

Dr Lufang Wang, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Union

Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science

and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei 430022, P.R. China.

|

1

|

Hanahan D: Hallmarks of cancer: New

Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12:31–46. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xiao Y and Yu D: Tumor microenvironment as

a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 221:1077532021.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Liu AY, Zheng H and Ouyang G: Periostin, a

multifunctional matricellular protein in inflammatory and tumor

microenvironments. Matrix Biol. 37:150–156. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Takeshita S, Kikuno R, Tezuka K and Amann

E: Osteoblast-specific factor 2: Cloning of a putative bone

adhesion protein with homology with the insect protein fasciclin I.

Biochem J. 294:271–278. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Horiuchi K, Amizuka N, Takeshita S,

Takamatsu H, Katsuura M, Ozawa H, Toyama Y, Bonewald LF and Kudo A:

Identification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin,

with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament

and increased expression by transforming growth factor beta. J Bone

Miner Res. 14:1239–1249. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sasaki H, Dai M, Auclair D, Fukai I,

Kiriyama M, Yamakawa Y, Fujii Y and Chen LB: Serum level of the

periostin, a homologue of an insect cell adhesion molecule, as a

prognostic marker in nonsmall cell lung carcinomas. Cancer.

92:843–848. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sasaki H, Dai M, Auclair D, Kaji M, Fukai

I, Kiriyama M, Yamakawa Y, Fujii Y and Chen LB: Serum level of the

periostin, a homologue of an insect cell adhesion molecule, in

thymoma patients. Cancer Lett. 172:37–42. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Borg TK and Markwald R: Periostin: More

than just an adhesion molecule. Circ Res. 101:230–231. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ruan K, Bao S and Ouyang G: The

multifaceted role of periostin in tumorigenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci.

66:2219–2230. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kudo A: Periostin in fibrillogenesis for

tissue regeneration: Periostin actions inside and outside the cell.

Cell Mol Life Sci. 68:3201–3207. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhu M, Fejzo MS, Anderson L, Dering J,

Ginther C, Ramos L, Gasson JC, Karlan BY and Slamon DJ: Periostin

promotes ovarian cancer angiogenesis and metastasis. Gynecol Oncol.

119:337–344. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

González-González L and Alonso J:

Periostin: A matricellular protein with multiple functions in

cancer development and progression. Front Oncol. 8:2252018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Morra L and Moch H: Periostin expression

and Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: A review and an

update. Virchows Arch. 459:465–475. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Norris RA, Moreno-Rodriguez RA, Sugi Y,

Hoffman S, Amos J, Hart MM, Potts JD, Goodwin RL and Markwald RR:

Periostin regulates atrioventricular valve maturation. Dev Biol.

316:200–213. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sorocos K, Kostoulias X, Cullen-McEwen L,

Hart AH, Bertram JF and Caruana G: Expression patterns and roles of

periostin during kidney and ureter development. J Urol.

186:1537–1544. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sun D, Lu J, Tian H, Li H, Chen X, Hua F,

Yang W, Yu J and Chen D: The impact of POSTN on tumor cell behavior

and the tumor microenvironment in lung adenocarcinoma. Int

Immunopharmacol. 145:1137132025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lin S, Zhou M, Cheng L, Shuai Z, Zhao M,

Jie R, Wan Q, Peng F and Ding S: Exploring the association of

POSTN+ cancer-associated fibroblasts with

Triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 268:1315602024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kanemoto Y, Sanada F, Shibata K,

Tsunetoshi Y, Katsuragi N, Koibuchi N, Yoshinami T, Yamamoto K,

Morishita R, Taniyama Y and Shimazu K: Expression of periostin

alternative splicing variants in normal tissue and breast cancer.

Biomolecules. 14:10932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ma H, Wang J, Zhao X, Wu T, Huang Z, Chen

D, Liu Y and Ouyang G: Periostin promotes colorectal tumorigenesis

through integrin-FAK-Src Pathway-mediated YAP/TAZ activation. Cell

Rep. 30:793–806.e6. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kujawa KA, Zembala-Nożyńska E, Cortez AJ,

Kujawa T, Kupryjańczyk J and Lisowska KM: Fibronectin and periostin

as prognostic markers in ovarian cancer. Cells. 9:1492020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pickup MW, Mouw JK and Weaver VM: The

extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep.

15:1243–1253. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Försti A, Jin Q, Altieri A, Johansson R,

Wagner K, Enquist K, Grzybowska E, Pamula J, Pekala W, Hallmans G,

et al: Polymorphisms in the KDR and POSTN genes: Association with

breast cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Breast Cancer Res

Treat. 101:83–93. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Szefler S, Corren J, Silverberg JI,

Okragly A, Sun Z, Natalie CR, Zitnik R, Siu K and Blauvelt A:

Lebrikizumab decreases type 2 inflammatory biomarker levels in

patients with asthma: Data from randomized phase 3 trials (LAVOLTA

I and II). Immunotherapy. 16:1211–1216. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gan C, Li M, Lu Y, Peng G, Li W, Wang H,

Peng Y, Hu Q, Wei W, Wang F, et al: SPOCK1 and POSTN are valuable

prognostic biomarkers and correlate with tumor immune infiltrates

in colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 23:42023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jia L, Li G, Ma N, Zhang A, Zhou Y, Ren L

and Dong D: Soluble POSTN is a novel biomarker complementing CA153

and CEA for breast cancer diagnosis and metastasis prediction. BMC

Cancer. 22:7602022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Alzobaidi N, Rehman S, Naqvi M, Gulati K

and Ray A: Periostin: A potential biomarker and therapeutic target

in pulmonary diseases. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 25:137–148. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yue H, Li W, Chen R, Wang J, Lu X and Li

J: Stromal POSTN induced by TGF-β1 facilitates the migration and

invasion of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 160:530–538. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Olsson L, Hammarström ML, Israelsson A,

Lindmark G and Hammarström S: Allocating colorectal cancer patients

to different risk categories by using a Five-biomarker mRNA

combination in lymph node analysis. PLoS One. 15:e02290072020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sugiura T, Takamatsu H, Kudo A and Amann

E: Expression and characterization of murine osteoblast-specific

factor 2 (OSF-2) in a baculovirus expression system. Protein Expr

Purif. 6:305–311. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ducy P, Geoffroy V and Karsenty G: Study

of Osteoblast-specific expression of one mouse osteocalcin gene:

Characterization of the factor binding to OSE2. Connect Tissue Res.

35:7–14. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ulstrup JC, Jeansson S, Wiker HG and

Harboe M: Relationship of secretion pattern and MPB70 homology with

osteoblast-specific factor 2 to osteitis following Mycobacterium

bovis BCG vaccination. Infect Immun. 63:672–675. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hoersch S and Andrade-Navarro MA:

Periostin shows increased evolutionary plasticity in its

alternatively spliced region. BMC Evol Biol. 10:302010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Nakama T, Yoshida S, Ishikawa K, Kobayashi

Y, Abe T, Kiyonari H, Shioi G, Katsuragi N, Ishibashi T, Morishita

R and Taniyama Y: Different roles played by periostin splice

variants in retinal neovascularization. Exp Eye Res. 153:133–140.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ikeda-Iwabu Y, Taniyama Y, Katsuragi N,

Sanada F, Koibuchi N, Shibata K, Shimazu K, Rakugi H and Morishita

R: Periostin short fragment with Exon 17 via aberrant alternative

splicing is required for breast cancer growth and metastasis.

Cells. 10:8922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

De Oliveira Macena Y, Cezar MEN, Lira CBF,

De Oliveira LBDM, Almeida TN, Costa ADAV, De Araujo BMD, de Almeida

D Junior, Dantas HM, De Mélo EC, et al: The roles of periostin

derived from Cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor progression and

treatment response. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 44:112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Morra L, Rechsteiner M, Casagrande S, Duc

Luu V, Santimaria R, Diener PA, Sulser T, Kristiansen G, Schraml P,

Moch H and Soltermann A: Relevance of periostin splice variants in

renal cell carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 179:1513–1521. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kuebart T, Oezel L, Gürsoy B, Maus U,

Windolf J, Bittersohl B and Grotheer V: Periostin splice variant

expression in human osteoblasts from osteoporotic patients and its

effects on Interleukin-6 and osteoprotegerin. Int J Mol Sci.

26:9322025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Litvin J, Selim AH, Montgomery MO, Lehmann

K, Rico MC, Devlin H, Bednarik DP and Safadi FF: Expression and

function of Periostin-isoforms in bone. J Cell Biochem.

92:1044–1061. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Viloria K and Hill NJ: Embracing the

complexity of matricellular proteins: The functional and clinical

significance of splice variation. Biomol Concepts. 7:117–132. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Xiong Z, Sneiderman CT, Kuminkoski CR,

Reinheimer J, Schwegman L, Sever RE, Habib A, Hu B, Agnihotri S,

Rajasundaram D, et al: Transcript-targeted antigen mapping reveals

the potential of POSTN splicing junction epitopes in glioblastoma

immunotherapy. Genes Immun. 26:190–199. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wenhua S, Tsunematsu T, Umeda M, Tawara H,

Fujiwara N, Mouri Y, Arakaki R, Ishimaru N and Kudo Y: Cancer

Cell-derived novel periostin isoform promotes invasion in head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 12:8510–8525. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kim CJ, Isono T, Tambe Y, Chano T, Okabe

H, Okada Y and Inoue H: Role of alternative splicing of periostin

in human bladder carcinogenesis. Int J Oncol. 32:161–169. 2008.

|

|

43

|

Kii I, Nishiyama T and Kudo A: Periostin

promotes secretion of fibronectin from the endoplasmic reticulum.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 470:888–893. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Kii I and Ito H: Periostin and its

interacting proteins in the construction of extracellular

architectures. Cell Mol Life Sci. 74:4269–4277. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Maruhashi T, Kii I, Saito M and Kudo A:

Interaction between periostin and BMP-1 promotes proteolytic

activation of lysyl oxidase. J Biol Chem. 285:13294–13303. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Takayama I, Tanabe H, Nishiyama T, Ito H,

Amizuka N, Li M, Katsube KI, Kii I and Kudo A: Periostin is

required for matricellular localization of CCN3 in periodontal

ligament of mice. J Cell Commun Signal. 11:5–13. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

47

|

Orecchia P, Conte R, Balza E, Castellani

P, Borsi L, Zardi L, Mingari MC and Carnemolla B: Identification of

a novel cell binding site of periostin involved in tumour growth.

Eur J Cancer. 47:2221–2229. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Rusbjerg-Weberskov CE, Johansen ML, Nowak

JS, Otzen DE, Pedersen JS, Enghild JJ and Nielsen NS: Periostin

C-Terminal is intrinsically disordered and interacts with 143

proteins in an in vitro epidermal model of atopic dermatitis.

Biochemistry. 62:2803–2815. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang Z, Lin M, Pan Y, Liu Y, Yang C, Wu J,

Wang Y, Yan B, Zhou J, Chen R and Liu C: Periostin+ myeloid cells

improved long bone regeneration in a mechanosensitive manner. Bone

Res. 12:592024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

50

|

Norris RA, Borg TK, Butcher JT, Baudino

TA, Banerjee I and Markwald RR: Neonatal and adult cardiovascular

pathophysiological remodeling and repair: Developmental role of

periostin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1123:30–40. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yang L, Guo T, Chen Y and Bian K: The

multiple roles of periostin in Non-neoplastic disease. Cells.

12:502022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Walker JT, McLeod K, Kim S, Conway SJ and

Hamilton DW: Periostin as a multifunctional modulator of the wound

healing response. Cell Tissue Res. 365:453–465. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Matsumoto H: Serum periostin: A novel

biomarker for asthma management. Allergol Int. 63:153–160. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Danielides G, Lygeros S, Kanakis M and

Naxakis S: Periostin as a biomarker in chronic rhinosinusitis: A

contemporary systematic review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol.

12:1535–1550. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Maintz L, Welchowski T, Herrmann N, Brauer

J, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Havenith R, Müller S, Rhyner C, Dreher A,

Schmid M, et al: IL-13, periostin and dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 reveal

endotype-phenotype associations in atopic dermatitis. Allergy. Jan

17–2023. View Article : Google Scholar : Epub ahead of

print. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Ono J, Takai M, Kamei A, Azuma Y and

Izuhara K: Pathological roles and clinical usefulness of periostin

in type 2 inflammation and pulmonary fibrosis. Biomolecules.

11:10842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mael-Ainin M, Abed A, Conway SJ, Dussaule

JC and Chatziantoniou C: Inhibition of periostin expression

protects against the development of renal inflammation and

fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 25:1724–1736. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Qiao B, Liu X, Wang B and Wei S: The role

of periostin in cardiac fibrosis. Heart Fail Rev. 29:191–206. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Nuzzo PV, Buzzatti G, Ricci F, Rubagotti

A, Argellati F, Zinoli L and Boccardo F: Periostin: A novel

prognostic and therapeutic target for genitourinary cancer? Clin

Genitourin Cancer. 12:301–311. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Shao R, Bao S, Bai X, Blanchette C,

Anderson RM, Dang T, Gishizky ML, Marks JR and Wang XF: Acquired

expression of periostin by human breast cancers promotes tumor

angiogenesis through up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth

factor receptor 2 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 24:3992–4003. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Liu B, Wu T, Lin B, Liu X, Liu Y, Song G,

Fan C and Ouyang G: Periostin-TGF-β feedforward loop contributes to

tumour-stroma crosstalk in liver metastatic outgrowth of colorectal

cancer. Br J Cancer. 130:358–368. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Tilman G, Mattiussi M, Brasseur F, van

Baren N and Decottignies A: Human periostin gene expression in

normal tissues, tumors and melanoma: Evidences for periostin

production by both stromal and melanoma cells. Mol Cancer.

6:802007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang S, Xiao X, Yi Y, Wang X, Zhu L, Shen

Y, Lin D and Wu C: Tumor initiation and early tumorigenesis:

Molecular mechanisms and interventional targets. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 9:1492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Dorafshan S, Razmi M, Safaei S, Gentilin

E, Madjd Z and Ghods R: Periostin: Biology and function in cancer.

Cancer Cell Int. 22:3152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Pavlova NN, Zhu J and Thompson CB: The

hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab.

34:355–377. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Moniuszko T, Wincewicz A, Koda M,

Domysławska I and Sulkowski S: Role of periostin in esophageal,

gastric and colon cancer. Oncol Lett. 12:783–787. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Huang M, Fang W, Farrel A, Li L,

Chronopoulos A, Nasholm N, Cheng B, Zheng T, Yoda H, Barata MJ, et

al: ALK upregulates POSTN and WNT signaling to drive neuroblastoma.

Cell Rep. 43:1139272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kikuchi Y, Kunita A, Iwata C, Komura D,

Nishiyama T, Shimazu K, Takeshita K, Shibahara J, Kii I, Morishita

Y, et al: The niche component periostin is produced by

cancer-associated fibroblasts, supporting growth of gastric cancer

through ERK activation. Am J Pathol. 184:859–870. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Hong L, Sun H, Lv X, Yang D, Zhang J and

Shi Y: Expression of periostin in the serum of NSCLC and its

function on proliferation and migration of human lung

adenocarcinoma cell line (A549) in vitro. Mol Biol Rep.

37:2285–2293. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Kotobuki Y, Yang L, Serada S, Tanemura A,

Yang F, Nomura S, Kudo A, Izuhara K, Murota H, Fujimoto M, et al:

Periostin accelerates human malignant melanoma progression by

modifying the melanoma microenvironment. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res.

27:630–639. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Chambers AF, Groom AC and MacDonald IC:

Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat

Rev Cancer. 2:563–572. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Parker TM, Henriques V, Beltran A,

Nakshatri H and Gogna R: Cell competition and tumor heterogeneity.

Semin Cancer Biol. 63:1–10. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Huang Y, Hong W and Wei X: The molecular

mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression

and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Lin SC, Liao YC, Chen PM, Yang YY, Wang

YH, Tung SL, Chuang CM, Sung YW, Jang TH, Chuang SE, et al:

Periostin promotes ovarian cancer metastasis by enhancing M2

macrophages and cancer-associated fibroblasts via integrin-mediated

NF-κB and TGF-β2 signaling. J Biomed Sci. 29:1092022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Cheon DJ, Tong Y, Sim MS, Dering J, Berel

D, Cui X, Lester J, Beach JA, Tighiouart M, Walts AE, et al: A

Collagen-remodeling gene signature regulated by TGF-β signaling is

associated with metastasis and poor survival in serous ovarian

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 20:711–723. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Park SY, Piao Y, Jeong KJ, Dong J and de

Groot JF: Periostin (POSTN) Regulates Tumor Resistance to

Antiangiogenic Therapy in Glioma Models. Mol Cancer Ther.

15:2187–2197. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Chen L, Tian X, Gong W, Sun B, Li G, Liu

D, Guo P, He Y, Chen Z, Xia Y, et al: Periostin mediates

epithelial-mesenchymal transition through the MAPK/ERK pathway in

hepatoblastoma. Cancer Biol Med. 16:89–100. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Tian Y, Choi CH, Li QK, Rahmatpanah FB,

Chen X, Kim SR, Veltri R, Chia D, Zhang Z, Mercola D and Zhang H:

Overexpression of periostin in stroma positively associated with

aggressive prostate cancer. PLoS One. 10:e01215022015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Pauley KM and Chan EK: MicroRNAs and their

emerging roles in immunology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1143:226–239. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Song Y, Sun J, Xu Y, Liu J, Gao P, Chen X,

Zhao J and Wang Z: Microarray analysis of long non-coding RNAs

related to microRNA-148b in gastric cancer. Neoplasma. 64:199–208.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Hu WW, Chen PC, Chen JM, Wu YM, Liu PY, Lu

CH, Lin YF, Tang CH and Chao CC: Periostin promotes

epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the MAPK/miR-381 axis in lung

cancer. Oncotarget. 8:62248–62260. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Hu J, Tan P, Ishihara M, Bayley NA,

Schokrpur S, Reynoso JG, Zhang Y, Lim RJ, Dumitras C, Yang L, et

al: Tumor heterogeneity in VHL drives metastasis in clear cell

renal cell carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:1552023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Ueki A, Komura M, Koshino A, Wang C, Nagao

K, Homochi M, Tsukada Y, Ebi M, Ogasawara N, Tsuzuki T, et al:

Stromal POSTN enhances motility of both cancer and stromal cells

and predicts poor survival in colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel).

15:6062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Miyako S, Koma YI, Nakanishi T, Tsukamoto

S, Yamanaka K, Ishihara N, Azumi Y, Urakami S, Shimizu M, Kodama T,

et al: Periostin in Cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression by enhancing cancer

and stromal cell migration. Am J Pathol. 194:828–848. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kim CJ, Sakamoto K, Tambe Y and Inoue H:

Opposite regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and

cell invasiveness by periostin between prostate and bladder cancer

cells. Int J Oncol. 38:1759–1766. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Ribatti D, Nico B, Crivellato E and Vacca

A: The structure of the vascular network of tumors. Cancer Lett.

248:18–23. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Ribatti D, Vacca A and Dammacco F: New

non-angiogenesis dependent pathways for tumour growth. Eur J

Cancer. 39:1835–1841. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Baril P, Gangeswaran R, Mahon PC, Caulee

K, Kocher HM, Harada T, Zhu M, Kalthoff H, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T and

Lemoine NR: Periostin promotes invasiveness and resistance of

pancreatic cancer cells to hypoxia-induced cell death: Role of the

beta4 integrin and the PI3k pathway. Oncogene. 26:2082–2094. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Bao S, Ouyang G, Bai X, Huang Z, Ma C, Liu

M, Shao R, Anderson RM, Rich JN and Wang XF: Periostin potently

promotes metastatic growth of colon cancer by augmenting cell

survival via the Akt/PKB pathway. Cancer Cell. 5:329–339. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Huang Z, Byrd O, Tan S, Hu K, Knight B, Lo

G, Taylor L, Wu Y, Berchuck A and Murphy SK: Periostin facilitates

ovarian cancer recurrence by enhancing cancer stemness. Sci Rep.

13:213822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Mariani A, Wang C, Oberg AL, Riska SM,

Torres M, Kumka J, Multinu F, Sagar G, Roy D and Jung DB: Genes

associated with bowel metastases in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol.

154:495–504. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Lozneanu L, Caruntu ID, Amalinei C,

Moscalu M, Gafton B, Marinca MV, Rusu A, Balan R and Giusca SE:

Periostin in ovarian carcinoma: From heterogeneity to prognostic

value. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 61:1–16. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Gillot L, Lebeau A, Baudin L, Pottier C,

Louis T, Durré T, Longuespée R, Mazzucchelli G, Nizet C, Blacher S,

et al: Periostin in lymph node pre-metastatic niches governs

lymphatic endothelial cell functions and metastatic colonization.

Cell Mol Life Sci. 79:2952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Kudo Y, Iizuka S, Yoshida M, Nguyen PT,

Siriwardena SB, Tsunematsu T, Ohbayashi M, Ando T, Hatakeyama D,

Shibata T, et al: Periostin directly and indirectly promotes tumor

lymphangiogenesis of head and neck cancer. PLoS One. 7:e444882012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Pistritto G, Trisciuoglio D, Ceci C,

Garufi A and D'Orazi G: Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: Function

and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic

strategies. Aging (Albany NY). 8:603–619. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Vaghari-Tabari M, Ferns GA, Qujeq D,

Andevari AN, Sabahi Z and Moein S: Signaling, metabolism, and

cancer: An important relationship for therapeutic intervention. J

Cell Physiol. 236:5512–5532. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Morana O, Wood W and Gregory CD: The

apoptosis paradox in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 23:13282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Gao L, Shay C and Teng Y: Cell death

shapes cancer immunity: Spotlighting PANoptosis. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 43:1682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Ouyang G, Liu M, Ruan K, Song G, Mao Y and

Bao S: Upregulated expression of periostin by hypoxia in

non-small-cell lung cancer cells promotes cell survival via the

Akt/PKB pathway. Cancer Lett. 281:213–219. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Erkan M, Reiser-Erkan C, Michalski CW,

Deucker S, Sauliunaite D, Streit S, Esposito I, Friess H and Kleeff

J: Cancer-stellate cell interactions perpetuate the

Hypoxia-fibrosis cycle in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Neoplasia. 11:497–508. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Zhou W, Ke SQ, Huang Z, Flavahan W, Fang

X, Paul J, Wu L, Sloan AE, McLendon RE, Li X, et al: Periostin

secreted by glioblastoma stem cells recruits M2 Tumour-associated

macrophages and promotes malignant growth. Nat Cell Biol.

17:170–182. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Wang H, Liang Y, Liu Z, Zhang R, Chao J,

Wang M, Liu M, Qiao L, Xuan Z, Zhao H and Lu L: POSTN+

cancer-associated fibroblasts determine the efficacy of

immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer.

12:e0087212024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

103

|

Jin X, Deng Q, Ye S, Liu S, Fu Y, Liu Y,

Wu G, Ouyang G and Wu T: Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived

periostin promotes papillary thyroid tumor growth through

integrin-FAK-STAT3 signaling. Theranostics. 14:3014–3028. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Muñoz-Espín D and Serrano M: Cellular