Ulcerative colitis (UC), a prototypical clinical

subtype of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is characterized by

chronic and recurrent non-specific inflammation primarily localized

within the mucosal and submucosal layers of the rectum and colon.

Surveillance data have highlighted a concerning rise in the global

incidence of UC (1,2), a trend that not only severely

compromises the quality of life of patients but also significantly

elevates the risk of colorectal carcinogenesis (3,4).

At present, conventional therapeutic agents such as

5-aminosalicylic acid, glucocorticoids and biologics (such as

anti-TNF and anti-integrin agents) are commonly employed.

Nevertheless, these pharmacotherapeutic interventions are hampered

by notable limitations in terms of efficacy, adverse effects,

individual responsiveness and a high relapse rate (5). Moreover, the economic burden and

psychological impact of long-term treatment further exacerbate

patient stress, underscoring the necessity for more effective and

individualized therapeutic approaches. Despite extensive research

efforts, the precise etiological determinants and comprehensive

pathophysiological mechanisms underlying UC remain incompletely

elucidated. Growing evidence accentuates the pivotal role of

intestinal barrier integrity (6,7),

a sophisticated, multi-layered defense system encompassing the

mucus layer, epithelial cells and intercellular junction complexes

(8), in both the initiation and

progression of UC. Mechanistic investigations have demonstrated

that UC pathogenesis involves intricate interactions among immune

dysregulation, disruption of intestinal epithelial homeostasis,

dysbiosis-driven bacterial colonization and compromised epithelial

barrier function (9).

Pathological alterations in tight junction (TJ)

proteins, such as ZO-1 and occludin, result in abnormal intestinal

permeability, facilitating the translocation of luminal bacteria,

endotoxins and undigested dietary antigens into the lamina propria

(10). These microbial

components and metabolites directly activate lamina propria immune

cells, triggering the robust release of pro-inflammatory cytokines

(11). This chemotactic

signaling recruits additional leukocytes to the inflammatory sites,

initiating a cascade that results in characteristic pathological

manifestations, including tissue erythema, exudation and mucosal

erosion. Notably, this self-perpetuating inflammatory milieu

exacerbates the degradation of TJ proteins (12,13), establishing a detrimental cycle

that perpetuates mucosal injury.

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) constitute the

primary defense of the intestinal mucosal barrier, playing a

pivotal role in maintaining mucosal homeostasis through dynamic

cell turnover and selective permeability regulation. Recent

investigations have identified dysregulated IEC death as a key

factor contributing to the perpetuation of colonic inflammation and

the resistance to therapy in UC pathogenesis (14-16). Under physiological conditions,

apoptosis maintains intestinal epithelial homeostasis through

programmed cell turnover. However, an excess of apoptotic activity

exceeding regenerative capacity can lead to extensive depletion of

IECs, causing structural denudation and compromising barrier

integrity (17). In addition to

apoptosis, other cell death mechanisms, including necroptosis,

PANoptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis and autophagy, have been

implicated in the pathogenesis of UC (18-22).

Therefore, elucidating the role of IEC death in UC

pathogenesis and systematically consolidating current research

achievements on modulating excessive IEC death through natural

compounds and nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems to

alleviate UC progression (particularly by integrating recent

advances in mechanistic pathways, bioactive constituents and

molecular targets) may offer novel perspectives for unraveling UC

etiology. This strategy could facilitate the precise identification

of potential therapeutic targets, thereby paving the way for

innovative methods for clinical UC management. Future research

endeavors should concentrate on developing targeted therapies that

address the multifaceted nature of IEC death and its downstream

inflammatory repercussions, ultimately disrupting the cycle of

mucosal damage and the inflammation characteristic of UC.

IECs are characterized by rapid and continuous

cellular renewal. Apoptosis, a key programmed cell death mechanism,

serves as an essential pathway for the physiological elimination of

aged IECs at the end of their life cycle and plays a critical role

in sustaining intestinal homeostasis (23). However, excessive activation of

apoptosis during UC progression may amplify inflammatory responses

via enhanced cytokine signaling (24). Upon exposure to stress stimuli,

such as the inflammatory microenvironment of UC, pro-apoptotic

proteins Bax and Bak undergo oligomerization and translocate to the

mitochondrial outer membrane, forming transmembrane pores (25). This event triggers mitochondrial

swelling and facilitates the efflux of cytochrome c from the

intermembrane space into the cytosol (26). Released cytochrome c subsequently

binds to apoptotic protease-activating factor-1, assembling the

apoptosome complex that activates caspase-9 through proteolytic

cleavage (27). This initiates a

downstream caspase cascade culminating in the execution phase of

apoptosis via caspase-3 activation and eventual cellular

dismantling (28).

In the dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced mouse

model of UC, intestinal tissues display a pronounced state of

oxidative stress, accompanied by upregulated Bax protein

expression, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, increased

cytochrome c release, markedly elevated apoptosis of IECs and

impaired intestinal barrier function, which manifests as increased

intestinal permeability and frequent bacterial translocation

(29,30). Clinical investigations have

demonstrated that patients with UC exhibit significantly elevated

expression levels of Fas and Fas ligand (FasL) in intestinal

mucosal tissues compared with healthy controls, with these levels

positively correlating with clinical severity indices (31,32). These findings collectively

suggest that the Fas/FasL-mediated extrinsic apoptosis pathway is

aberrantly activated during UC pathogenesis, driving excessive IEC

apoptosis and thereby compromising barrier integrity. Within the

colonic tissues of patients with UC, the tumor suppressor p53

functions as a pivotal transcriptional regulator orchestrating

multiple apoptosis-related genes (33). Notably, enhanced phosphorylation

of p53 has been shown to be positively correlated with disease

severity (34). Under

inflammatory conditions, interleukin (IL)-1β released from

activated immune cells potentiates p53-mediated apoptotic

signaling, thereby exacerbating epithelial apoptosis and amplifying

mucosal inflammation (35). An

experimental study employing TNF-α-induced murine models revealed

augmented IEC apoptosis in both acute and chronic inflammation

settings (36). This apoptotic

imbalance disrupts epithelial homeostasis, thereby facilitating UC

progression. Moreover, the upregulated expression of METTL3 and

long non-coding RNAs such as MALAT1 under inflammatory conditions

has been mechanistically linked to suppressed cellular viability

and enhanced IEC apoptosis, unveiling novel molecular pathways in

UC pathogenesis (37,38).

Following IEC apoptosis, multiple chemokines are

released to recruit immune cells to intestinal inflammatory sites,

including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and IL-8, a process

that plays a central role in the pathogenesis of UC. During disease

progression, persistent inflammatory stimuli and sustained cell

death signaling maintain macrophage activation, thereby

establishing a self-amplifying pathological loop (39,40). In DSS-induced murine UC models, a

rapid elevation of IL-8 levels has been observed in intestinal

tissues post-induction, concomitant with robust neutrophil

infiltration. This pathological progression exhibits temporal

synchronization with IEC apoptosis and necrosis, and these three

pathological events mutually reinforce one another through

feed-forward mechanisms. Collectively, this triad drives the

chronicity and perpetuation of intestinal inflammation (41).

Conventional therapies have been predominantly aimed

at suppressing excessive immune responses but have largely

neglected emerging pathological aspects such as the restoration of

intestinal mucosal barrier integrity and the correction of

dysregulated IEC apoptosis, resulting in suboptimal efficacy and

frequent relapses in certain patient populations (42). These limitations have catalyzed

the exploration of natural compounds and novel targeted

therapeutic. Ginkgetin (GK), a natural compound derived from

Ginkgo biloba with multi-protective properties, has been

shown to ameliorate DSS-induced experimental colitis in murine

models. Mechanistic investigations reveal that GK administration

attenuates IEC apoptosis through inhibition of the EGFR/PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway, accompanied by upregulation of the

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and downregulation of pro-apoptotic

proteins Bax and caspase-3, thereby restoring intestinal barrier

integrity (43). Similarly, in

acetic acid-induced rat models of UC, Centella asiatica

treatment effectively normalizes dysregulated apoptosis markers,

including elevated Bcl-2 alongside reduced Bax and caspase-3, while

mitigating oxidative stress and attenuating inflammatory responses

(44). Despite consistent

modulation of key biomarkers, studies on Centella asiatica

often lack rigorous dose-response evaluation and thorough long-term

toxicity assessments, which are essential for translational

applicability. Daphnetin exerts protective effects against IEC

apoptosis by inhibiting the regenerating islet-derived protein

3α-dependent Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/STAT3 signaling pathway,

resulting in reduced expression of pro-apoptotic proteins and

decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (45). Both lipopolysaccharide

(LPS)-treated human colon adenocarcinoma Caco-2 cell inflammatory

models and DSS-induced UC rat models have demonstrated that the

natural bioactive compound paeoniflorin alleviates UC by modulating

serum metabolites and suppressing the CDC42/JNK signaling pathway,

thereby inhibiting IEC apoptosis (46).

Nonetheless, current investigations primarily

emphasize acute therapeutic efficacy, with limited assessment of

remission durability or relapse prevention in chronic UC contexts.

Emerging as a promising therapeutic approach, exosome-based

interventions have gained attention due to their low immunogenicity

and superior circulatory stability. In murine UC models, caprine

milk-derived exosomes have been shown to attenuate oxidative

stress, suppress apoptosis, restore intestinal barrier integrity

and modulate gut microbiota composition (47). Mechanistically, oxidative stress

acts as a key driver of IEC apoptosis and recent evidence indicates

that mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes confer protective

effects by mitigating ROS accumulation in IECs, thereby alleviating

UC-associated tissue damage (48). While exosome therapies offer

multi-modal benefits, current preclinical studies face challenges

including heterogeneity in exosome isolation techniques, lack of

standardized dosing regimens and limited investigation of potential

off-target effects. Furthermore, the precise mechanisms underlying

exosome-mediated immunomodulation, barrier restoration and

concurrent suppression of inflammatory signaling and apoptotic

pathways remain to be fully elucidated.

While active exploration into natural compounds and

biological vectors such as exosomes continues, advances in

pharmaceutical engineering and drug repurposing have concurrently

unveiled innovative avenues for UC therapy. Prior investigations

have substantiated that berberine (BBR), a bioactive constituent of

traditional Chinese medicine, effectively mitigates DSS-induced

colonic inflammation; however, its clinical translation has been

hampered by inherent limitations including poor aqueous solubility

and short half-life (49,50).

In recent years, the advent of nanotechnology-engineered poly

(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles encapsulating BBR has

markedly enhanced drug encapsulation efficiency, aqueous solubility

and bioactivity, thereby conferring superior therapeutic outcomes

in UC experimental models (51).

Donepezil, originally developed for Alzheimer's disease management,

is renowned for its neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory and

antioxidant attributes (52,53). Evidence has further elucidated

its capacity to upregulate low-density lipoprotein receptor-related

protein 1 expression, activate AMPK signaling and suppress the

NF-κB inflammatory cascade, thereby attenuating intestinal

inflammation and epithelial apoptosis (54). Analogously, the small-molecule

inhibitor ruxolitinib ameliorates UC pathological progression by

targeting the JAK/STAT3 pathway, effectively suppressing NF-κB

activation, curtailing apoptosis and fostering barrier repair, thus

presenting a promising targeted therapeutic strategy (55). Notwithstanding these

advancements, emerging modalities continue to confront key

challenges, including unresolved optimal dosing regimens,

tissue-specific targeting and sustained long-term efficacy within

the intestinal milieu.

Necroptosis, a distinct form of programmed necrotic

cell death, exerts a pivotal influence on intestinal inflammation.

The core molecular machinery involves sequential activation and

signaling transduction of receptor-interacting protein kinase

(RIPK) 1, RIPK3 and mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL)

(56). Under homeostatic

conditions, RIPK1 serves as a central signaling hub that

coordinates cellular stress responses and preserves epithelial

integrity (57). During

intestinal inflammation triggered by pathogenic stimuli or

excessive TNF-α release, TNF-α engagement with tumor necrosis

factor receptor 1 initiates RIPK1 oligomerization via death domain

interactions, culminating in kinase activation (58). RIPK1 is subsequently incorporated

into a complex containing Fas-associated death domain (FADD) and

caspase-8 (complex IIa), in which caspase-8 acts as a critical

molecular switch. Upon activation, caspase-8 cleaves RIPK1 and

RIPK3, thereby promoting apoptotic cell death while concurrently

suppressing necroptosis initiation (59). By contrast, when caspase-8

activity is compromised (for example, by genetic deletion or

pharmacological inhibition) RIPK1 interacts with RIPK3 to

facilitate formation of the RIPK1-RIPK3 complex, known as the

necrosome (60-62). Activated RIPK3 phosphorylates

MLKL, converting it from an inactive monomer to a functional

oligomeric state (63). The

phosphorylated MLKL oligomers acquire membrane-targeting capability

through conformational changes and subsequently translocate to the

plasma membrane, ultimately leading to cellular swelling, membrane

rupture and necroptosis. The resultant released of

damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including bioactive

molecules such as high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and ATP, have

been demonstrated to exert immunomodulatory effects (64). Studies have demonstrated that

selective deficiency or functional impairment of caspase-8 in the

intestinal epithelium markedly increases susceptibility to

necroptosis, exacerbates experimental colitis and further

underscores its protective role in the pathogenesis of UC (65,66).

Studies encompassing patients with UC and animal

models have substantiated that hyperactivation of the necroptosis

pathway represents a pivotal pathogenic determinant, contributing

to both intestinal barrier disruption and aberrant inflammatory

cascades (67,68). Histopathological analyses have

revealed markedly elevated expression levels of RIPK1, RIPK3 and

MLKL in IECs, accompanied by enhanced phosphorylation status,

within the inflammatory lesions of patients with UC and

experimental models (22).

Accumulating evidence indicates that additional regulatory

molecules, including purinergic receptor P2Y14 (P2Y14), retinoic

acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and macrophage migration inhibitory

factor (MIF), may participate in the fine-tuned regulation of this

process. For instance, the purinergic receptor P2Y14 is upregulated

in the inflamed colonic mucosa of patients with UC, where it

facilitates RIPK1 transcription via the cAMP/protein kinase A/cAMP

response element-binding protein signaling pathway, thereby

aggravating IEC necroptosis and amplifying intestinal inflammation

(69). Furthermore, upon ligand

engagement, the cytosolic RNA sensor RIG-I upregulates MLKL

expression via interferon signaling, directly facilitating pore

formation (70). Alternatively,

RIG-I may indirectly amplify RIPK3-dependent necroptosis by

eliciting cytokine production, including type I interferons and TNF

(71). Under pathological stress

conditions such as ischemia and inflammation, MIF actively fosters

RIPK1-mediated necroptosis, thereby intensifying tissue injury

(72,73). Collectively, these findings

underscore that necroptosis in UC is governed by a sophisticated,

multifaceted regulatory network. Furthermore, investigations using

the DSS-induced murine colitis model have demonstrated

significantly upregulated expression of A20-binding inhibitor of

NF-κB activation 1, RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL in colonic tissues.

Notably, pharmacological blockade with Nec-1s potently inhibits

RIPK1 kinase activity, markedly suppressing IEC necroptosis and

mitigating colonic inflammatory responses (74). Subsequent analyses of clinical

specimens have corroborated a statistically significant positive

correlation between RIPK3 expression in the colonic tissues of

patients with UC and disease severity indices. Concurrently,

genetic ablation of the RIPK3 gene in mice confers notable

protection against IEC apoptosis through blockade of the Toll-like

receptor 4 (TLR4)/myeloid differentiation primary response protein

88 (MyD88)/NF-κB pathway, effectively alleviating experimental

colitis (75).

Contemporary research endeavors are centered on the

development of targeted inhibitors against pivotal necroptosis

regulators, such as RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL, with accumulating

evidence demonstrating that pharmacologically modulating these

targets in IEC can effectively ameliorate UC. For instance, the

citrus flavonoid naringenin and curcumin have been shown to

suppress IEC necroptosis by downregulating the mRNA expression of

RIPK3 and MLKL, thereby preserving intestinal barrier integrity and

markedly ameliorating colitis pathology (76,77). A natural chalcone derivative,

ermanin from the genus Leptinella, has exhibited dual

inhibition of RIPK1/3 kinases in the DSS-induced colitis model.

Mechanistic elucidation revealed that it attenuates intestinal

barrier impairment via blockade of MLKL phosphorylation,

demonstrating promising therapeutic potential for UC (78). Further investigations

demonstrated that polysaccharides from pine pollen and their

sulfated derivatives markedly attenuate the inflammatory index in

the colitis model, diminish IEC necroptosis incidence and enhance

mucosal barrier function through augmented mucin 2 secretion,

thereby furnishing robust experimental substantiation for clinical

translation (79). The

traditional Chinese herbal remedy Sargentodoxa cuneata

ameliorates disease manifestations in murine colitis models by

curtailing IEC necroptosis (80).

In addition to the aforementioned natural products,

chemically modified compounds and targeted chemical agents have

likewise unveiled therapeutic utility. For instance, the

myricetin-3-O-β-d-lactose sodium salt derivative

M10, engineered via incorporation of a hydrophilic glycosyl moiety,

displays full aqueous solubility and high stability. A study has

established that oral administration of M10 inhibits necroptosis in

inflamed colonic epithelium by suppressing TNF-α signaling,

exhibiting superior efficacy relative to mesalazine in averting

chronic colitis (81).

Indole-3-carbinol, a naturally occurring dietary agonist of the

aryl hydrocarbon receptor, upon receptor engagement, impedes RIPK1

activation and necrosome assembly in a temporally regulated manner,

thereby reducing IEC apoptosis and ameliorating intestinal

inflammation (82). As a

linchpin modulator of necroptosis and inflammatory cascades, RIPK1

inhibitors potently disrupt inflammatory signaling, attenuate IEC

injury and curtail leukocyte infiltration. Multiple studies have

corroborated that RIPK1 inhibitors such as SZ-15, HtrA2 and

LY3009120 markedly attenuate colonic inflammation, foster tissue

regeneration and ameliorate UC progression, thereby illuminating

the compelling therapeutic prospects of RIPK1-targeted

interventions in UC management (83-85).

Dynamic regulatory nodes orchestrate the delicate

equilibrium between necroptosis and apoptosis, ensuring adaptive

responses to inflammatory stimuli. In the nascent phases of

inflammation, where cellular insult remains modest, the organism

preferentially engages programmed apoptotic pathways. This

non-inflammatory clearance modality safeguards tissue homeostasis

and mitigates excessive immune activation (86). This phase is characterized by

selective engagement of apoptotic cascades, where the extrinsic

apoptotic pathway mediated by the Fas/FasL pathway and the

mitochondrial-dependent intrinsic apoptotic pathway are

preferentially activated to facilitate the orderly clearance of

damaged cells (87). As

inflammatory escalation ensues, perturbations in intracellular

homeostasis, such as caspase inhibition or aberrant upregulation of

anti-apoptotic effectors, precipitate a phenotypic shift in cell

death modality toward necroptosis (88). Notably, DAMPs released during

necroptosis engage pattern recognition receptors on adjacent cells

via paracrine signaling, thereby upregulating death receptor

expression and fostering an apoptosis-prone milieu (89). This ultimately leads to a

positive feedback loop of cell death and inflammation,

significantly exacerbating intestinal epithelial barrier

dysfunction and the spread of inflammation (90). Precise modulation of

apoptosis-associated gene expression is expected to fundamentally

restore the homeostasis of cell death and promote the repair of

intestinal epithelial barrier function. This paradigm unveils a

novel molecular intervention strategy for personalized UC

management, holding notable clinical translational promise.

Nonetheless, effectively implementing these conceptual advances

into practical therapeutics mandates surmounting critical

challenges, including target specificity, efficacious delivery

platforms and inter-individual heterogeneity in gene expression

signatures.

Pyroptosis, a distinct programmed inflammatory cell

death modality, has a molecular foundation based on

inflammasome-dependent activation of select caspase family members,

notably caspase-1 and the caspase-4/5/11 isoforms (91,92). In the pathological evolution of

UC, the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome

has emerged as a pivotal regulatory hub mediating inflammatory

cascades within the intestinal mucosa. As an intracellular

multiprotein complex, the canonical NLRP3 inflammasome incorporates

three foundational constituents: The pattern recognition receptor

NLRP3, the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing a CARD (ASC) and the procaspase-1 precursor (93). Under homeostatic conditions,

NLRP3 adopts an auto-inhibited conformation with its activation

meticulously governed by an array of modulatory factors, thereby

safeguarding equilibrium in IECs. Upon perturbation of the

intestinal milieu by pathological cues, pathological stimuli

including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), DAMPs or

metabolic stress, the NLRP3 inflammasome initiates its assembly

process (94). In patients with

UC, intestinal dysbiosis results in a marked elevation of LPS

derived from Gram-negative bacteria. Functioning as a canonical

PAMP, LPS initiates nuclear translocation of NF-κB through

engagement with TLR4. Activated NF-κB upregulates NLRP3 gene

expression and fosters synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines

(95,96). Consequent to secondary signal

stimulation, intracellular potassium efflux, ROS accumulation or

lysosomal destabilization, the nascent NLRP3 undergoes NACHT

domain-mediated oligomerization, recruiting the adaptor protein ASC

to form multiprotein inflammasome complexes. ASC, through PYD-CARD

domain interplay, facilitates autoproteolytic maturation of

procaspase-1, yielding enzymatically proficient caspase-1

heterotetramers (97). Activated

caspase-1 exerts dichotomous biological effects: i) Orchestrates

extracellular release of mature IL-1β and IL-18 through cleavage of

their pro-forms; and ii) specifically cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD)

to generate the pore-forming N-terminal domain (GSDMD-N). GSDMD-N

subsequently oligomerizes to form transmembrane pores on the plasma

membrane, triggering cellular osmotic lysis (98). This lytic event facilitates a

large release of DAMPs and HMGB1, thereby engendering a

self-amplifying feedback loop that intensifies intestinal

inflammatory amplification (99).

Pyroptosis in IECs triggers a cascade of immune

responses that disrupt the intestinal immune perturbations that

destabilize the intestinal immune milieu, a phenomenon intimately

linked to UC pathogenesis. In DSS-induced colitis models,

transgenic overexpression of lipocalin-2 in wild-type mice markedly

exacerbates colonic inflammation and epithelial injury, concomitant

with elevated pyroptosis biomarkers specifically localized to the

IECs of colonic mucosa derived from patients with UC (100). Type III interferons (IFN-λ)

have been demonstrated to augment IEC pyroptosis, thereby

undermining mucosal wound repair and curtailing regenerative

potential (101). Danger

signals released during pyroptosis foster dendritic cell maturation

and enhance their antigen-presenting capacity, driving naïve T cell

differentiation toward pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 subsets

(102). Concurrently, these

signals attenuate regulatory T cell functionality, engendering an

immunosuppressive imbalance that perpetuates uncontrolled

inflammatory responses (103).

Collectively, these observations delineate IEC pyroptosis as a

perpetuator of intestinal inflammation in UC via a self-sustaining

inflammatory circuit, which fundamentally underpins the therapeutic

refractoriness encountered in clinical practice.

While pyroptosis predominantly exerts

pro-inflammatory and tissue-damaging effects in the pathogenesis of

UC, elucidation of its molecular underpinnings furnishes a

foundational rationale for devising targeted therapeutic

interventions. Phytosterols, a class of plant-derived bioactive

sterols, exhibit therapeutic potential through their prototypical

constituent sitosterol (SIT). Mechanistically, SIT modulates the

NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling axis to significantly attenuate IEC

pyroptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokine release, while

concurrently augmenting TJ protein expression to bolster mucosal

barrier integrity (104).

However, most evidence remains preclinical, and the

pharmacokinetics, bioavailability and safety of SIT in chronic UC

contexts remain inadequately characterized. The extract from

Astragalus membranaceus Bunge has been shown to ameliorate

UC by curtailing IEC pyroptosis via upregulation of phospholipase

C-β2 (105). The pathological

characteristics of refractory UC progression primarily encompass a

self-perpetuating cycle linking mucosal barrier disruption and

unrelenting inflammatory amplification. Recent evidence

substantiates that nanocarrier-mediated targeted delivery of

4-octyl itaconate to IECs potently suppresses GSDME-mediated

pyroptosis (14). Further

investigation has revealed that the artemisinin derivative SM934

exhibits dual modulatory effects in experimental colitis models; it

concurrently inhibits programmed cell death modalities and

abrogates caspase-1-dependent pyroptotic cascades, thereby markedly

ameliorating epithelial barrier impairment (106). Nevertheless, the long-term

efficacy, toxicity and dosing regimens for SM934 in chronic models

warrant comprehensive evaluation to surmount translational hurdles.

Schisandrin B attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome activation-mediated

IL-1β secretion and IEC pyroptosis in colitis models by activating

AMPK/Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-dependent

signaling to mitigate ROS-induced mitochondrial damage, suggesting

its potential as a therapeutic strategy for acute colitis (107). In LPS/ATP-induced in

vitro models of IEC pyroptosis and inflammation utilizing HT29

human colonic carcinoma cells, resveratrol forestalls pyroptosis

onset by impeding NF-κB pathway activation (108). Beyond phytogenic agents,

mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their secreted exosomes have

recently garnered notable attention for therapeutic applications.

Hair follicle-derived MSC exosomes convey differentially expressed

microRNAs (miRNAs) that concurrently suppress both tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) signaling and

IFN-γ inflammatory pathways, thereby effectively inhibiting IEC

pyroptosis (109). Notably,

bone marrow-derived MSC exosomes selectively suppress

NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway activation via miR-539-5p shuttling,

thereby modulating the pyroptosis-associated molecular network and

ultimately attenuating UC progression (110).

In recent years, contemporary drug discovery

paradigms targeting pyroptosis have diversified, with numerous

chemical and nucleic acid therapeutics evincing robust efficacy.

For instance, miR-141-3p effectively inhibits LPS-induced IEC

pyroptosis by targeting the HSP90 molecular chaperone, while

concurrently alleviating inflammation in DSS-induced murine

colitis, highlighting its promise as a nucleic acid-based

therapeutic approach for UC (111). The broad-spectrum antiviral

nucleotide remdesivir likewise ameliorates IEC pyroptosis and gut

inflammatory cascades by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome and

downstream caspase-1/GSDMD signaling (112). Meanwhile, ruscogenin, a

steroidal sapogenin from Ophiopogon japonicus, has

demonstrated potential in mitigating inflammatory processes by

suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation and caspase-1-dependent

canonical pyroptosis (113).

Moreover, in acute severe UC, the methyl-donor betaine effectively

inhibits oxidative stress-induced inflammatory pyroptosis, thereby

expanding the therapeutic repertoire for UC (114). These findings suggest that

precision regulation strategies targeting aberrant pyroptosis in

IECs may disrupt the 'pyroptosis-inflammation-barrier disruption'

positive feedback loop, thereby establishing an innovative

therapeutic paradigm for UC pathological intervention.

Ferroptosis, a unique modality of programmed cell

death, was initially characterized and designated in 2012 by Dixon

et al (115) through

systematic investigation. Distinct from other forms of regulated

cell death, ferroptosis is pathologically defined by the intricate

interplay between iron ion homeostasis dysregulation and lipid

peroxidation accumulation (116). IECs predominantly internalize

iron via transferrin receptor 1-dependent endocytosis (117). Upon endocytosis,

Fe3+ is enzymatically reduced to biologically active

Fe2+ species via metalloreductases such as

Six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3 (118,119). During the pathogenesis of UC,

IECs are subjected to a sustained inflammatory milieu, which

elicits dysregulated mobilization of excess Fe2+ from

the labile iron pool and thereby instigates ROS generation through

Fenton reaction cascades (19).

The Fenton reaction employs Fe2+-mediated catalytic

cycles to decompose hydrogen peroxide into highly reactive hydroxyl

radicals. These radicals preferentially attack membrane

phospholipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (120), thereby initiating a

self-amplifying chain reaction of lipid peroxidation. Glutathione

peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a pivotal regulator of lipid redox balance,

forms the cornerstone of ferroptosis suppression. Under homeostatic

conditions, GPX4 utilizes reduced glutathione (GSH) to transmute

deleterious lipid hydroperoxides into innocuous lipid alcohols,

effectively suppressing the cascade amplification of lipid

peroxidation (121). Notably,

in UC progression, multiple pathogenic factors synergistically

inhibit GPX4 enzymatic activity, thereby impairing its

detoxification of peroxidation intermediates. Upon decompensation

of the antioxidant defense system, lipid peroxidation products

surpass cellular homeostatic thresholds, ultimately triggering

ferroptosis in IECs through the disruption of membrane structural

integrity (122,123).

As the principal mucosal interface organ, the

intestinal tract exhibits a characteristic oxidative stress

microenvironment due to persistent exposure to exogenous stimuli

including microbiota, metabolites and food-derived antigens

(124). Investigations have

revealed a reciprocal pathophysiological interplay between

ferroptosis in IECs and gut oxidative stress status. In murine

colitis models, inflammation-orchestrated oxidative perturbations

markedly elevate ferroptosis effectors [cyclooxygenase-2 and

acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4)] in parallel

with diminished protein abundance of GPX4 and ferritin heavy chain

1. These molecular signatures demonstrate positive correlation with

the extent of IEC injury (125). Pharmacological preconditioning

with ferroptosis inhibitors has been demonstrated to markedly

attenuate above-mentioned histopathological manifestations in

DSS-induced colitis. Integrative multi-omics profiling has unveiled

signature expression patterns of ferroptosis-linked genes in

tissues derived from patients with UC (126,127). Mechanistic investigations have

demonstrated that ACSL4, a master regulator of ferroptosis,

accelerates IEC ferroptosis by activating the NF-κB signaling

pathway, thereby contributing to UC pathogenesis (128).

There have been notable advancements in therapeutic

modalities targeting ferroptosis regulation in IECs, with

innovative interventions conferring antioxidant cytoprotection and

inflammatory attenuation via selective ferroptosis pathway

blockade. Astragalus polysaccharide (APS), the predominant

bioactive polysaccharide from the traditional Chinese herb A.

membranaceus, has demonstrated anti-ferroptotic efficacy across

multiple experimental models. Experimental evidence demonstrated

that APS significantly suppresses ferroptosis progression and

sustains cellular homeostasis in DSS-induced murine colitis models

and as well as RSL3-treated human IECs in vitro (129). Multi-omics analyses has

unveiled that vanillic acid (VA) modulates the ferroptosis axis

through targeted ligation to carbonic anhydrase IX and stromal

interaction molecule 1, effectively restoring intestinal epithelial

barrier integrity and emerging as a novel therapeutic candidate for

UC (130). Nevertheless, the

target fidelity and off-target liabilities of VA within intricate

human milieus necessitate rigorous delineation. Emerging data

implicate that disrupted iron homeostasis exacerbates colitis

progression via dual mechanisms involving ferroptosis activation

and gut microbiota dysbiosis (131,132). Pharmacological investigations

confirm that palmatine, a natural isoquinoline alkaloid, markedly

diminishes colonic iron deposition and ameliorates experimental UC

pathology via multi-target modulation, concurrently suppressing

NF-κB inflammatory signaling, ROS generation and ferroptosis signal

cascades (133). Notably, the

oral iron chelator deferasirox represses IEC ferroptosis,

reprograms gut microbiota architecture and augments short-chain

fatty acid (SCFA) biosynthesis, thereby ameliorating DSS-induced UC

inflammation through multifaceted mechanisms and evincing clinical

promise (134). However, the

use of iron chelators still requires cautious monitoring of dosage

and safety to avoid potential adverse effects (135,136).

Beyond directly targeting the ferroptosis pathway,

certain nutritional factors and metabolites also demonstrate

therapeutic value. Butyrate is a microbiota-derived SCFA depleted

in colitis-afflicted murine cohorts. A study has revealed that

sodium butyrate treatment activates the Nrf2/GPX4 signaling

pathway, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis, alleviating oxidative

stress and inflammatory responses and restoring intestinal barrier

function (137). Furthermore,

vitamin D has been demonstrated to attenuate ferroptosis in

DSS-induced murine models and LPS-stimulated HCT116 cells through

ACSL4 repression, consequently tempering UC severity (138). Additionally, supplementation

with the essential trace element selenium, particularly in the form

of sodium selenite, effectively reduces IEC mortality,

intracellular iron content, lipid ROS and mitochondrial membrane

damage, ultimately attenuating DSS-induced colitis (139). Nevertheless, these benefits,

optimal dosing paradigms, delivery modalities and protracted

efficacy demand validation via robust clinical trials.

While breakthrough advances have been achieved in

natural compound research, exosomes (critical mediators of

intercellular communication) have emerged as possessing unique

biomedical potential in the therapeutics of UC. Human umbilical

cord MSC-derived exosomes can deliver miR-129-5p to specifically

suppress the expression of ACSL4, dually regulating the progression

of lipid peroxidation and the function of the GSH-GPX4 antioxidant

axis (142). A recent study has

demonstrated that endometrial regenerative cell-derived exosomes

enhance GSH biosynthesis and GPX4 enzymatic activity while

coordinately attenuating tissue iron accumulation, malondialdehyde

levels and ACSL4 protein expression, demonstrating marked efficacy

in ameliorating both histopathological damage and clinical

manifestations of colitis (143). An in-depth analysis of the

molecular regulatory network underlying abnormal ferroptosis in

IECs would not only yield precise therapeutic targets for UC but

also promises the advent of innovative pharmacotherapeutics through

targeted modulation of key ferroptosis pathways, thereby improving

intestinal barrier function.

Autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved intracellular

degradation system, orchestrates cellular homeostasis and stress

adaptation via regulated material recycling. Based on substrate

transport mechanisms, autophagy is categorized into three subtypes:

Macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy

(144). Among these,

macroautophagy predominates as the primary regulatory mechanism,

forming the cornerstone of autophagy research. Upon

microenvironmental stimuli such as nutrient deprivation or

oxidative stress (145,146), endoplasmic reticulum-resident

unfolded protein response sensors synergize with other stress

detectors to trigger a transcriptional cascade of autophagy-related

genes via regulators including transcription factor EB (147). This process initiates with the

formation of a double-membrane structure termed the phagophore in

the cytoplasm (148), which

achieves quality control by selectively enveloping targeted

substrates including damaged organelles and misfolded proteins.

Following subsequent membrane extension and closure, the phagophore

matures into an autophagosome that fuses with lysosomal membranes

to form an autolysosome (149).

Within the autolysosomal lumen, acid hydrolases degrade the

enclosed cargo into recyclable metabolites, such as amino acids and

free fatty acids (150), that

are effluxed into the cytoplasm through lysosomal transporters.

These metabolites are released into the cytoplasm via lysosomal

membrane transporters, where they re-enter biosynthetic pathways or

fuel the tricarboxylic acid cycle, thereby completing the

closed-loop regulation of intracellular material recycling

(151).

In recent years, the regulatory role of autophagy in

UC pathogenesis has garnered substantial attention in

gastroenterology research, with its dual regulatory properties

exhibiting complex biological effects during disease progression.

Pathologically, UC is characterized by dysregulated dynamic

equilibrium of pro-/anti-inflammatory cytokine networks, coupled

with unrelenting inflammatory cascades, aberrant intestinal barrier

permeability and perturbed expression of TJ proteins, collectively

driving disease chronicity (152). Mechanistic investigations have

elucidated that TNF-α-driven inflammatory microenvironments impair

intestinal epithelial barrier integrity via impaired autophagic

flux, manifesting as aberrant claudin-2 expression and TJ

disruption, a process mechanistically linked to autolysosomal

system dysfunction (153).

Analyses of clinical specimens from patients with active UC reveal

notable downregulation of autophagy regulator activating

transcription factor 4 in intestinal mucosa, implicating diminished

autophagic capacity in disease exacerbation (154). Pharmacological autophagy

activation in LPS-stimulated Caco-2 cell models and experimental

colitis animals significantly reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines

and ameliorates oxidative stress indices, underscoring the

therapeutic potential of autophagy modulation in IBD (155,156). In DSS-induced colitis models,

autophagy impairment intensifies intestinal inflammation through

hyperactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby promoting

caspase-1 cleavage and maturation of IL-1β/IL-18 (157,158). Crucially, excessive autophagy

activation may induce type II programmed cell death, underscoring

the importance of precise autophagic activity regulation given this

dual-edged effect. In Erbin knockout murine models, autophagy

inhibitor chloroquine mitigates DSS-induced hyperinflammation by

blocking autophagosome-lysosome fusion, with mechanisms involving

downregulation of cell death-associated proteins, thereby

illustrating the context-specific utility of autophagy suppression

(159). Collectively, current

evidence establishes autophagy as a homeostatic modulator in UC,

with its pro-survival and pro-death duality being precisely

controlled by microenvironmental signaling networks.

Pharmacological investigations on the classical

formula Baitouweng decoction have demonstrated that it augments

autophagic flux via AMPKα phosphorylation activation and mTORC1

complex inhibition, thereby restoring intestinal epithelial barrier

integrity and attenuating disease activity index scores in

DSS-induced murine colitis models (160). Mechanistic investigations

reveal that procyanidin A1 augments autophagic activity through the

AMPK/mTOR/p70S6K signaling axis in LPS-stimulated IEC inflammation

models, markedly suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion

(161). Notably, the probiotic

strain Lactobacillus plantarum OLL2712 activates protective

autophagy in IECs via the MyD88-dependent pathway, thereby

reorganizing TJ proteins to fortify intestinal barrier mechanics

(162). Although

probiotic-mediated autophagy modulation represents a burgeoning

therapeutic avenue, elucidation of strain specificity, dosage

regimens and host microbiome interplay remains imperative. Compound

sophora decoction significantly alleviates DSS-induced intestinal

inflammation by fostering autophagy through suppression of PI3K/AKT

pathway activation (163).

Moreover, the Jianpi Qingchang (JPQC) decoction, composed of nine

traditional Chinese medicinal herbs, alleviates colitis progression

by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated excessive

autophagy in IECs within a DSS-induced model (164) Notably, JPQC underscores the

contextual therapeutic merits of both autophagy activation and

inhibition, albeit the dose-dependent dichotomous effects warrant

deeper scrutiny.

Accumulating evidence indicates that disrupting

autophagic homeostasis is a pivotal node in UC pathogenesis, with

pharmacological restoration of autophagic dynamic equilibrium

emerging as a novel therapeutic target. Beyond the aforementioned

Chinese herbal and natural products, diverse active compounds and

biomacromolecules have shown therapeutic promise in UC management

via autophagy modulation. For instance, epimedium polysaccharide

(EPS), a bioactive compound, has been shown to engender autophagy

augmentation via the AMPK/mTOR pathway amid colonic inflammation,

exerting a protective effect in DSS-induced UC models, which

suggests EPS as a potential therapeutic target (165). Upregulation of circular RNA

HECTD1 has been shown to orchestrate HuR-dependent autophagy in

IECs via miR-182-5p sequestration, consequently ameliorating UC

histopathology (166) The Slit

family of glycoproteins (Slit1-3), canonically expressed in neural

and immune compartments, exert regulatory oversight on inflammatory

cascades (167,168). Overexpression of Slit2 has been

shown to sustain intestinal stem cell proliferation and normal

autophagic flux in mice following DSS challenge, thereby mitigating

colonic inflammation and curtailing pro-inflammatory cytokine

secretion (169). These

emerging strategies provide innovative perspectives for UC

intervention through the modulation of autophagy; however, the

majority of current studies remain focused on mechanistic

exploration and are still considerably distant from clinical

application. Future research should focus on enhancing target

specificity, optimizing delivery systems and clarifying the

pharmacodynamic-to-toxicological equilibrium, thereby facilitating

their translation into clinical practice.

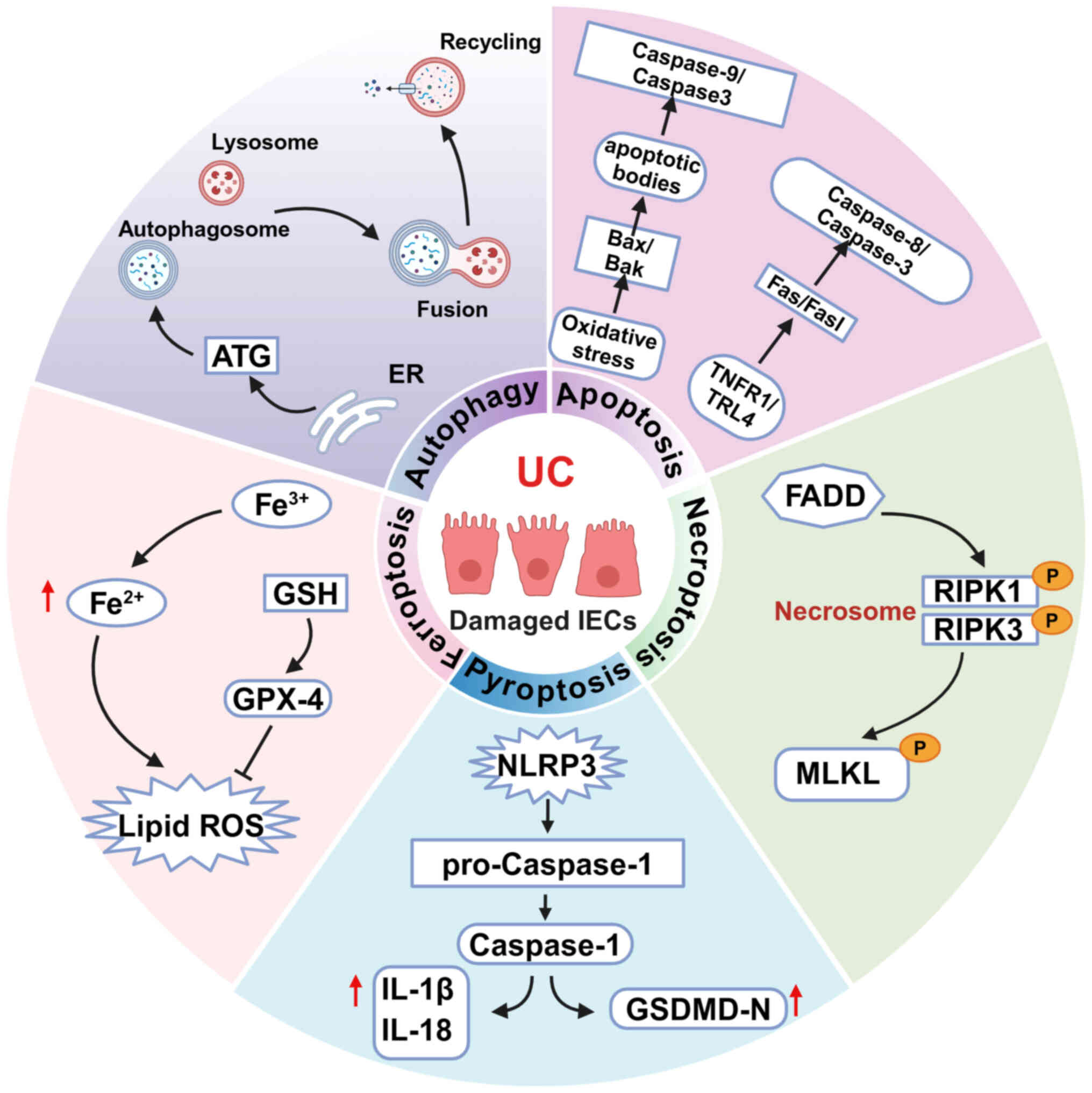

Disruption of intestinal barrier integrity is firmly

established as a central pathological feature of UC, driven by

intricate molecular mechanisms involving a dynamic interplay

between IEC homeostatic imbalance and dysregulation of the immune

microenvironment. The present review summarizes the major

programmed cell death modalities in IECs in UC: Autophagy,

ferroptosis, pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis (Fig. 1). As the principal components of

the intestinal mechanical barrier, dysregulated IEC death directly

impairs TJ complexes, leading to epithelial barrier breakdown and

subsequent hyperactivation of pattern recognition receptor-mediated

innate immune responses. This series of events leads to a

self-sustaining cycle of persistent inflammation and mucosal

injury. Recent progress in single-cell RNA sequencing and

intestinal organoid technologies has yielded unprecedented insights

into the spatiotemporal dynamics of IEC death modalities and their

association with UC pathological phenotypes, providing a molecular

framework for understanding disease heterogeneity and

patient-specific variations (14,17,100,170-172).

Recent studies have unveiled a novel programmed cell

death pathway known as PANoptosis, which merges key molecular

characteristics of pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis to form a

multifaceted death complex (173,174). The regulatory framework of

PANoptosis entails the integration and interplay of multiple

signaling pathways. Research has highlighted the crucial roles of

key regulatory molecules such as Z-DNA binding protein 1 (ZBP1),

RIPK1 and RIPK3 in the PANoptosis pathway (175). The nucleic acid sensor ZBP1,

activated during pathogen infection or cellular stress by

recognizing viral nucleic acids or endogenous DAMPs, undergoes

conformational changes to recruit and phosphorylate RIPK3 (176). Notably, upon activation by

death receptor ligands or PAMPs, RIPK1 initiates PANoptosis

signaling transduction by engaging downstream molecules through its

death domain. Additionally, RIPK1 forms a functional complex with

RIPK3, jointly driving the phosphorylation cascade of MLKL and

ultimately inducing cells to enter the PANoptosis program (177,178). Within IECs, a complex molecular

interplay exists among apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis and the

resulting PANoptosis, all of which play critical roles in the

pathogenesis of IBD. Caspase-8 and its adaptor protein FADD serve

as central molecules interconnecting these three programmed cell

death pathways (59). Upon

excessive stimulation by TNF or TLR signaling, caspase-8 is

activated and regulates cell fate by initiating apoptosis through

the cleavage of downstream caspase-3/7, while also modulating RIPK1

and RIPK3 to inhibit necroptosis (179). Concurrently, caspase-8 can

interact with ASC to activate caspase-1 and cleave GSDMD, thereby

triggering pyroptosis (180).

When caspase-8 function is compromised or inhibited by pathogens,

both apoptotic and pyroptotic pathways are impaired, leading cells

to undergo RIPK3-mediated necroptosis, which exacerbates intestinal

barrier disruption and inflammatory responses. Furthermore, in the

absence of caspase-1 in IECs, inflammasome sensors such as NLRP1b

and NLRC4 can still initiate apoptosis through ASC-dependent

caspase-8 activation (181).

The necroptosis effector MLKL can also promote ASC oligomerization

and caspase-1 activation, thereby linking necroptosis with

pyroptosis (182). These

intricate molecular interactions illustrate that apoptosis,

necroptosis and pyroptosis are interconnected through shared

molecular components, collectively driving epithelial cell death,

barrier dysfunction and exacerbated intestinal inflammation in UC.

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that PANoptosis plays a crucial

regulatory role in the pathogenesis of IBD, particularly UC. In the

DSS-induced murine colitis model, IECs exhibited concurrent

phenotypes of Dynamin related protein 1 mediated mitochondrial

fission and ZBP1-dependent PANoptosis. Notably, analysis of

clinical specimens revealed a significant positive correlation

between the activation levels of PANoptosis in IECs and the

clinical activity index of patients with UC (21,183).

Despite notable advancements in recent years in

elucidating the mechanisms of IEC programmed death in UC, several

crucial issues remain unresolved. For instance, the intricate

interplay between various programmed death pathways, including

apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis, requires

further elucidation. For instance, the novel multimodal cell death

pathway PANoptosis, which integrates key molecular features of

apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis, necessitates in-depth

exploration of its specific regulatory mechanisms in UC and its

synergistic or antagonistic interactions with other death pathways.

Additionally, the dynamic interactions between programmed death

pathways and the intestinal microenvironment, such as dysbiosis and

metabolic products, demand thorough investigation to unravel the

complex networks in the pathological progression of UC. Given the

intricate interconnections and mutual regulation among these

programmed cell death pathways, combination therapies that target

multiple key nodes of apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis

concurrently may enable precise modulation of the cell death

network, leading to more comprehensive intestinal protection and

inflammation control. Furthermore, emerging strategies such as the

utilization of gene-editing technologies (such as CRISPR/Cas9) to

regulate the expression of critical genes including caspase-8 and

RIPK3, or the application of stem cell and genetically engineered

cell-based therapies to restore compromised epithelial function,

offer promising avenues for future therapeutics. Collectively,

interventions that target programmed cell death in IECs at multiple

levels and from various angles hold significant promise for

mitigating epithelial damage and inflammation in UC, thereby

advancing therapeutic strategies for this disease.

Natural bioactive compounds and

nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems have gained significant

attention in biomedical research due to their notable translational

potential, especially in the management of metabolic disorders and

tumor immunomodulation. Their therapeutic efficacy stems from their

unique ability to simultaneously modulate multiple molecular

targets, while maintaining favorable biosafety profiles, offering

innovative and multifaceted strategies for UC treatment. Notably,

an increasing body of evidence highlights the distinct potential of

natural bioactive compounds and nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery

systems in UC therapy, particularly in their capability to preserve

colonic epithelial barrier integrity and mitigate pro-inflammatory

cytokine cascades by precisely regulating programmed cell death

pathways. These compounds and nanoparticles exert their protective

effects by targeting key molecular mechanisms underlying epithelial

dysfunction and immune dysregulation, thereby addressing the dual

pathological axes of UC.

The present review provides a comprehensive analysis

of the central role of IEC death in the pathogenesis of

UC-associated chronic inflammation and mucosal injury. Furthermore,

it consolidates recent progress in the utilization of natural

small-molecule compounds and nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery

systems that selectively target abnormal IEC death to mitigate

barrier dysfunction, as summarized in Table SI. These compounds, sourced from

a variety of natural origins, have exhibited effectiveness in

modulating crucial signaling pathways, presenting promising

therapeutic opportunities for UC management. In terms of clinical

translation, while natural compounds and nanomedicines have

demonstrated significant potential in modulating programmed death

pathways, their targeting and bioavailability encounter challenges.

For instance, the delivery efficiency of nanomedicines is

constrained by the intricate intestinal milieu, and enhancing their

targeting, such as through surface ligand modification or

utilization of intestinal-specific receptors, represents a current

research priority. Additionally, despite the advantages of the

multi-target properties of natural compounds in treating UC, their

potential for unforeseen side effects necessitates further

structural refinement and pharmacological assessment. Future

research should integrate single-cell omics, organoid models and

systems pharmacology techniques to precisely decipher the molecular

mechanisms of programmed death pathways and develop more efficient

and safer targeted therapeutic strategies to surmount existing

treatment bottlenecks and improve the clinical prognosis of

patients with UC.

Looking forward, transformative breakthroughs in UC

therapy will necessitate the development of integrated therapeutic

strategies that concurrently target IEC death pathways and their

downstream hyperinflammatory responses. These strategies aim to

disrupt the self-sustaining cycle of 'barrier damage-inflammation

amplification' that underlies the core of UC pathogenesis. One

approach involves the development of therapeutic agents capable of

synergistically modulating multiple targets within the regulated

cell death network. Given the intricate molecular crosstalk among

different forms of programmed cell death, involving key molecules

such as caspase-8, RIPK3 and GSDMD, inhibitors targeting a single

pathway may be insufficient to fully prevent the dysregulated death

of IECs. The design of small molecules or biologics that

concurrently regulate multiple critical nodes holds potential for

more effectively restoring IEC homeostasis, thereby achieving

comprehensive protection of the intestinal barrier and improved

control of inflammation. Additionally, enhancing targeting

specificity while minimizing systemic side effects is crucial for

successful clinical translation. Employing nanotechnology,

antibody-drug conjugates or oral targeted delivery systems to

selectively accumulate therapeutics within inflamed intestinal

tissues or IECs can enhance local drug concentrations and markedly

reduce off-target effects in other organs. Novel therapeutic

approaches involving gene editing and cell therapy also warrant

exploration. While still in the early stages of investigation,

in vivo or ex vivo editing of dysregulated genes in

IEC (such as caspase-8 or RIPK3) using technologies such as

CRISPR/Cas9, or the administration of genetically engineered stem

cells or organoids to repair damaged epithelium, presents a highly

promising next-generation treatment strategy. These interventions

may provide novel options for patients with refractory UC who are

intolerant to conventional pharmacological or biological therapies.

In summary, future drug development for UC should transcend the

traditional 'single target, single disease' paradigm and adopt

integrated, multi-targeted, multimodal and precision-focused

strategies with an emphasis on local intestinal targeting. By

addressing these unresolved mechanisms and clinical translation

challenges, the present review not only establishes a new

theoretical framework for understanding the pathomechanism of UC

but also establishes a robust basis for the advancement of

innovative therapeutic strategies, offering significant scientific

and clinical implications.

Not applicable.

BW drafted and revised the manuscript. BW and SS

conceptualized the review and contributed to the writing. YL

participated in literature collation and manuscript editing. LG

reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Research Foundation of the

Department of Education of Yunnan Province (grant no. 2025Y1195)

and Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (grant no.

202501AT070405).

|

1

|

Buie MJ, Quan J, Windsor JW, Coward S,

Hansen TM, King JA, Kotze PG, Gearry RB, Ng SC, Mak JWY, et al:

Global hospitalization trends for Crohn's disease and ulcerative

colitis in the 21st century: A systematic review with temporal

analyses. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21:2211–2221. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart

DC and Sandborn WJ: Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 380:1606–1619.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Leppkes M and Neurath MF: Cytokines in

inflammatory bowel diseases - Update 2020. Pharmacol Res.

158:1048352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Le Berre C, Loeuille D and Peyrin-Biroulet

L: Combination therapy with vedolizumab and tofacitinib in a

patient with ulcerative colitis and spondyloarthropathy. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17:794–796. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Abdalla MI and Levesque BG: Progress in

corticosteroid use in the Era of biologics with room for

improvement. Am J Gastroenterol. 116:1187–1188. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Quansah E, Gardey E, Ramoji A,

Meyer-Zedler T, Goehrig B, Heutelbeck A, Hoeppener S, Schmitt M,

Waldner M, Stallmach A and Popp J: Intestinal epithelial barrier

integrity investigated by label-free techniques in ulcerative

colitis patients. Sci Rep. 13:26812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chen Q, Chen T, Xiao H, Wang F, Li C, Hu

N, Bao L, Tong X, Feng Y, Xu Y, et al: APEX1 in intestinal

epithelium triggers neutrophil infiltration and intestinal barrier

damage in ulcerative colitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 225:359–373.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Peterson LW and Artis D: Intestinal

epithelial cells: Regulators of barrier function and immune

homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 14:141–153. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jiminez JA, Uwiera TC, Douglas Inglis G

and Uwiera RR: Animal models to study acute and chronic intestinal

inflammation in mammals. Gut Pathog. 7:292015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yan H and Ajuwon KM: Butyrate modifies

intestinal barrier function in IPEC-J2 cells through a selective

upregulation of tight junction proteins and activation of the Akt

signaling pathway. PLoS One. 12:e01795862017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mehandru S and Colombel JF: The intestinal

barrier, an arbitrator turned provocateur in IBD. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18:83–84. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Su L, Nalle SC, Shen L, Turner ES, Singh

G, Breskin LA, Khramtsova EA, Khramtsova G, Tsai PY, Fu YX, et al:

TNFR2 activates MLCK-dependent tight junction dysregulation to

cause apoptosis-mediated barrier loss and experimental colitis.

Gastroenterology. 145:407–415. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fukuda T, Majumder K, Zhang H, Turner PV,

Matsui T and Mine Y: Adenine inhibits TNF-α signaling in intestinal

epithelial cells and reduces mucosal inflammation in a dextran

sodium sulfate-induced colitis mouse model. J Agric Food Chem.

64:4227–4234. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li W, Chen D, Zhu Y, Ye Q, Hua Y, Jiang P,

Xiang Y, Xu Y, Pan Y, Yang H, et al: Alleviating pyroptosis of

intestinal epithelial cells to restore mucosal integrity in

ulcerative colitis by targeting delivery of 4-Octyl-itaconate. ACS

Nano. 18:16658–16673. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chi F, Zhang G, Ren N, Zhang J, Du F,

Zheng X, Zhang C, Lin Z, Li R, Shi X and Zhu Y: The anti-alcoholism

drug disulfiram effectively ameliorates ulcerative colitis through

suppressing oxidative stresses-associated pyroptotic cell death and

cellular inflammation in colonic cells. Int Immunopharmacol.

111:1091172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen Y, Yan W, Chen Y, Zhu J, Wang J, Jin

H, Wu H, Zhang G, Zhan S, Xi Q, et al: SLC6A14 facilitates

epithelial cell ferroptosis via the C/EBPβ-PAK6 axis in ulcerative

colitis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 79:5632022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Zhang J, Cen L, Zhang X, Tang C, Chen Y,

Zhang Y, Yu M, Lu C, Li M, Li S, et al: MPST deficiency promotes

intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis and aggravates inflammatory

bowel disease via AKT. Redox Biol. 56:1024692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Foerster EG, Mukherjee T, Cabral-Fernandes

L, Rocha JDB, Girardin SE and Philpott DJ: How autophagy controls

the intestinal epithelial barrier. Autophagy. 18:86–103. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

19

|

Xu M, Tao J, Yang Y, Tan S, Liu H, Jiang

J, Zheng F and Wu B: Ferroptosis involves in intestinal epithelial

cell death in ulcerative colitis. Cell Death Dis. 11:862020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ma ZR, Li ZL, Zhang N, Lu B, Li XW, Huang

YH, Nouhoum D, Liu XS, Xiao KC, Cai LT, et al: Inhibition of

GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis triggered by Trichinella spiralis

intervention contributes to the alleviation of DSS-induced

ulcerative colitis in mice. Parasit Vectors. 16:2802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang JM, Yang J, Xia WY, Wang YM, Zhu YB,

Huang Q, Feng T, Xie LS, Li SH, Liu SQ, et al: Comprehensive

analysis of PANoptosis-related gene signature of ulcerative

colitis. Int J Mol Sci. 25:3482023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Akanyibah FA, Zhu Y, Jin T, Ocansey DKW,

Mao F and Qiu W: The function of necroptosis and its treatment

target in IBD. Mediators Inflamm. 2024:72753092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Iwanaga T and Takahashi-Iwanaga H:

Disposal of intestinal apoptotic epithelial cells and their fate

via divergent routes. Biomed Res. 43:59–72. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Soroosh A, Fang K, Hoffman JM, Law IKM,

Videlock E, Lokhandwala ZA, Zhao JJ, Hamidi S, Padua DM, Frey MR,

et al: Loss of miR-24-3p promotes epithelial cell apoptosis and

impairs the recovery from intestinal inflammation. Cell Death Dis.

13:82021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wolf P, Schoeniger A and Edlich F:

Pro-apoptotic complexes of BAX and BAK on the outer mitochondrial

membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1869:1193172022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sheridan C, Delivani P, Cullen SP and

Martin SJ: Bax- or Bak-induced mitochondrial fission can be

uncoupled from cytochrome C release. Mol Cell. 31:570–585. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhou M, Li Y, Hu Q, Bai XC, Huang W, Yan

C, Scheres SH and Shi Y: Atomic structure of the apoptosome:

mechanism of cytochrome c- and dATP-mediated activation of Apaf-1.

Genes Dev. 29:2349–2361. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Albalawi GA, Albalawi MZ, Alsubaie KT,

Albalawi AZ, Elewa MAF, Hashem KS and Al-Gayyar MMH: Curative

effects of crocin in ulcerative colitis via modulating apoptosis

and inflammation. Int Immunopharmacol. 118:1101382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lin S, Zhang X, Zhu X, Jiao J, Wu Y, Li Y

and Zhao L: Fusobacterium nucleatum aggravates ulcerative colitis

through promoting gut microbiota dysbiosis and dysmetabolism. J

Periodontol. 94:405–418. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Li Y, Ma M, Wang X, Li J, Fang Z, Li J,

Yang B, Lu Y, Xu X and Li Y: Celecoxib alleviates the DSS-induced

ulcerative colitis in mice by enhancing intestinal barrier

function, inhibiting ferroptosis and suppressing apoptosis.

Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 46:240–254. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Iwamoto M, Makiyama K, Koji T, Kohno S and

Nakane PK: Expression of Fas and Fas-ligand in epithelium of

ulcerative colitis. Nihon Rinsho. 54:1970–1974. 1996.In Japanese.

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Souza HS, Tortori CJ, Castelo-Branco MT,

Carvalho AT, Margallo VS, Delgado CF, Dines I and Elia CC:

Apoptosis in the intestinal mucosa of patients with inflammatory

bowel disease: Evidence of altered expression of FasL and perforin

cytotoxic pathways. Int J Colorectal Dis. 20:277–286. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Tang R, Jiang L, Ji Q, Kang P, Liu Y, Miao

P, Xu X and Tang M: Resveratrol targeting MDM2/P53/PUMA axis to

inhibit colonocyte apoptosis in DSS-induced ulcerative colitis

mice. Front Pharmacol. 16:15729062025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chen J: The Cell-Cycle Arrest and

Apoptotic Functions of p53 in Tumor Initiation and Progression.

Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6:a0261042016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Eissa N, Hussein H, Diarra A, Elgazzar O,

Gounni AS, Bernstein CN and Ghia JE: Semaphorin 3E regulates

apoptosis in the intestinal epithelium during the development of

colitis. Biochem Pharmacol. 166:264–273. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Parker A, Vaux L, Patterson AM, Modasia A,

Muraro D, Fletcher AG, Byrne HM, Maini PK, Watson AJM and Pin C:

Elevated apoptosis impairs epithelial cell turnover and shortens

villi in TNF-driven intestinal inflammation. Cell Death Dis.

10:1082019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yan R, Liang X and Hu J: MALAT1 promotes

colonic epithelial cell apoptosis and pyroptosis by sponging

miR-22-3p to enhance NLRP3 expression. PeerJ. 12:e184492024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang L, Wu G, Wu Q, Peng L and Yuan L:

METTL3 overexpression aggravates LPS-induced cellular inflammation

in mouse intestinal epithelial cells and DSS-induced IBD in mice.

Cell Death Discov. 8:622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu MM, Wang QM, Huang BY, Mai CT, Wang CL,

Wang TT and Zhang XJ: Dioscin ameliorates murine ulcerative colitis

by regulating macrophage polarization. Pharmacol Res.

172:1057962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Palmela C, Chevarin C, Xu Z, Torres J,

Sevrin G, Hirten R, Barnich N, Ng SC and Colombel JF:

Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel disease.

Gut. 67:574–587. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Chen B, Wang Y, Niu Y and Li S: Acalypha

australis L. Extract attenuates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in

mice by regulating inflammatory factor release and blocking NF-κB

activation. J Med Food. 26:663–671. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lasa JS, Olivera PA, Danese S and

Peyrin-Biroulet L: Efficacy and safety of biologics and small

molecule drugs for patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative

colitis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7:161–170. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Geng Z, Zuo L, Li J, Yin L, Yang J, Duan

T, Wang L, Zhang X, Song X, Wang Y and Hu J: Ginkgetin improved

experimental colitis by inhibiting intestinal epithelial cell

apoptosis through EGFR/PI3K/AKT signaling. FASEB J. 38:e238172024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lokman MS, Kassab RB, Salem FAM,

Elshopakey GE, Hussein A, Aldarmahi AA, Theyab A, Alzahrani KJ,

Hassan KE, Alsharif KF, et al: Asiatic acid rescues intestinal

tissue by suppressing molecular, biochemical, and histopathological

changes associated with the development of ulcerative colitis.

Biosci Rep. 44:BSR202320042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

He Z, Liu J and Liu Y: Daphnetin

attenuates intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis

in ulcerative colitis via inhibiting REG3A-dependent JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway. Environ Toxicol. 38:2132–2142. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hu Q, Xie J, Jiang T, Gao P, Chen Y, Zhang

W, Yan J, Zeng J, Ma X and Zhao Y: Paeoniflorin alleviates

DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by suppressing inflammation,

oxidative stress, and apoptosis via regulating serum metabolites

and inhibiting CDC42/JNK signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol.

142(Pt A): 1130392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Gao F, Wu S, Zhang K, Xu Z, Zhang X, Zhu Z

and Quan F: Goat milk exosomes ameliorate ulcerative colitis in

mice through modulation of the intestinal barrier, gut microbiota,

and metabolites. J Agric Food Chem. 72:23196–23210. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhu F, Wei C, Wu H, Shuai B, Yu T, Gao F,

Yuan Y, Zuo D, Liu X, Zhang L and Fan H: Hypoxic mesenchymal stem

cell-derived exosomes alleviate ulcerative colitis injury by

limiting intestinal epithelial cells reactive oxygen species

accumulation and DNA damage through HIF-1α. Int Immunopharmacol.

113(Pt A): 1094262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Li H, Fan C, Lu H, Feng C, He P, Yang X,

Xiang C, Zuo J and Tang W: Protective role of berberine on

ulcerative colitis through modulating enteric glial

cells-intestinal epithelial cells-immune cells interactions. Acta

Pharm Sin B. 10:447–461. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gao C, Liu L, Zhou Y, Bian Z, Wang S and

Wang Y: Novel drug delivery systems of Chinese medicine for the

treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Chin Med. 14:232019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Liu C, Gong Q, Liu W, Zhao Y, Yan X and

Yang T: Berberine-loaded PLGA nanoparticles alleviate ulcerative

colitis by targeting IL-6/IL-6R axis. J Transl Med. 22:9632024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Buck A, Rezaei K, Quazi A, Goldmeier G,

Silverglate B and Grossberg GT: The donepezil transdermal system

for the treatment of patients with mild, moderate, or severe

Alzheimer's disease: A critical review. Expert Rev Neurother.

24:607–614. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Gwon HJ, Cho W, Choi SW, Lim DS,