Obesity has now become the world's most significant

public health issue, intimately intertwined with an assortment of

metabolic dysregulations, encompassing insulin resistance, type 2

diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular pathologies (1). Over the past few years, there has

been a burgeoning interest in the role of immune cells in obesity

and its associated pathologies, which has risen to prominence as a

pivotal area of investigation (2).

Bariatric surgery, recognized as an effective

intervention for obesity and its associated metabolic disorders,

has become widely utilized in clinical settings (3). Research indicates that the

peripheral immune cells of obese individuals experience substantial

alterations prior to and following bariatric surgery (4). The observed alterations pertain to

the restructuring of immune cell populations, alterations in their

activation levels and changes in the expression patterns of

molecules that regulate immune checkpoints (4). Bariatric surgery is known to elicit

transformations in the circulation of T cells among obese

individuals, notably affecting the regulatory dynamics of cluster

of differentiation (CD)4+ and CD8+T cell

populations. Additionally, alterations in the gut microbiome

following bariatric surgery may influence the progression of

obesity-related diseases by modulating the host's immune system

(5).

Nevertheless, research into the changes in

peripheral immune cells following bariatric surgery remains an area

of ongoing exploration and refinement (6). Variations in sample selection,

detection methods and observation time across different studies

have contributed to some inconsistencies in the findings. Moreover,

the causal link between changes in immune cells and the improvement

of obesity-related diseases, as well as the underlying molecular

mechanisms, remain incompletely understood (7). The risk of complications following

bariatric surgery can now be quantified by four categories of

biomarkers: Pre-operative albumin <3.5 g/dl increases 30-day

mortality and anastomotic leak risk by 1.4-2.3-fold (8); C-reactive protein (CRP) >12

mg/dl plus white blood count >12×109/l on

post-operative day 1 yields an 82% positive predictive value for

major complications (9); rising

oxidative-stress markers [malondialdehyde (MDA),

8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG)] and interleukin (IL)-6 peaks

show a dose-response relationship with Clavien-Dindo ≥III

complications (8); and

pre-operative deficiencies in Fe, B12 and 25-hydroxy vitamin D

affect 35-60% of patients, with a 25% anemia rate at one year,

indicating that peri-operative inflammatory and nutritional

biomarkers jointly forewarn of both early and late adverse events

(10).

The present review sought to comprehensively

synthesize the latest research advances regarding the changes in

peripheral immune cells following bariatric surgery. It aims to

investigate the underlying links between these immune cell

alterations and obesity-related diseases and to suggest potential

directions for future research. By doing so, it hopes to offer a

new theoretical foundation and innovative research perspectives for

the management of obesity and its associated conditions.

Following bariatric surgery, there is a noted

augmentation in the population of CD4+T lymphocytes and

the CD4+T cell profile returned to a phenotype

resembling that of lean controls, along with an expansion of T

follicular helper (Tfh) cells. However, no changes were noted in

CD8+T cells (4).

Bariatric surgery altered the subset composition of

CD4+T cells and B cells to more closely resemble that of

lean controls. Furthermore, there was an enhancement in the

capacity of CD4+T cells to synthesize IL-2 and IFN-γ,

observed three months following the surgical procedure.

Nonetheless, the cytokine production capabilities of

CD8+T cells and B cells did not exhibit any significant

alteration three months post-operation (16). However, while reviewing the

literature, it was found that this study indicated a significant

increase in the number of CD8+T cells following

bariatric surgery (4,6). Therefore, the key reason for the

divergent conclusions lies in the different metrics used: One study

focused on the relative proportion of cells within lymphocytes,

whereas others monitored the absolute count in blood (4,6,16). Post-surgical weight loss and

hemoconcentration can raise the total number of cells while keeping

their proportion among lymphocytes unchanged.

Obesity disrupts the subset of regulatory T cells

that provide metabolic protection in visceral adipose tissue (VAT),

leading to heightened VAT inflammation and aggravated insulin

resistance (17). Regulatory T

cells (Tregs) gather in VAT to sustain systemic metabolic balance,

but their numbers decrease during obesity; restoring Treg

cholesterol homeostasis was found to rescue VAT Treg accumulation

in obese mice (15). Patients

with low Treg levels showed more significant metabolic improvement

after surgery, likely due to their more severe preoperative

inflammatory state (18). After

the removal of inflammatory adipose tissue during surgery, the

proportion of Tregs in the remaining fat tissue may increase

relatively, though further research is needed to confirm this

(19).

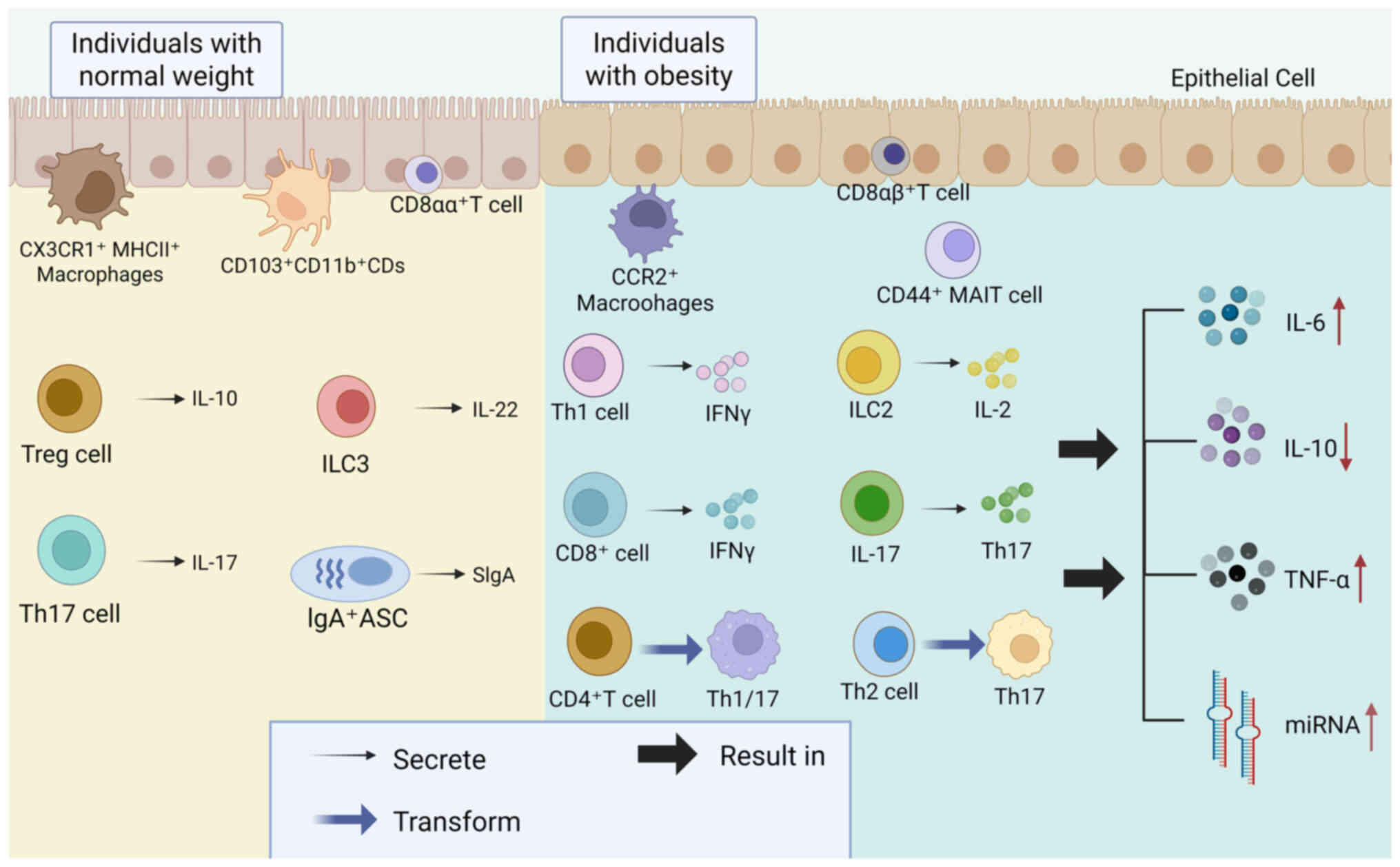

In B cells, the adipose tissue size in obese

individuals grows with age, causing systemic and intrinsic B cell

inflammation (20). This leads

to a decline in protective B cell responses and an upsurge in

pathogenic B cell responses, which in turn results in increased

secretion of autoantibodies (20). In addition, obese individuals

experience heightened IL-6 production and diminished IL-10

production. Furthermore, immune activation markers like tumor

necrosis factor (TNF)-α and micro-RNAs are found to be elevated in

stimulated B cells and these alterations are inversely associated

with B cell function (21). At 6

months post-bariatric surgery, patients exhibited a unique B cell

profile that is nearly unrecognizable compared with their

preoperative state and is somewhat similar to that of healthy lean

individuals (22). Despite

overall improvements in inflammation and metabolic health,

discrepancies within the B cell compartment in comparison to lean

controls continue to be observed (22).

Following bariatric surgery, the ability of B cells

to produce cytokines in patients with obesity stays at levels

comparable to those before the surgery and does not reach the

levels seen in healthy individuals (16). This alteration in function might

be linked to the persistent inflammation often seen in obesity.

Even though bariatric surgery helps reduce inflammation, it may

take B cells a longer time to regain full function (16). Thus, the juxtaposition of

'structural similarity' with 'functional non-recovery' is not

contradictory; rather, it reflects the staged nature of

post-surgical immune remodeling: First achieving 'form', then

'function', with the latter requiring a more prolonged period of

inflammation resolution.

Among obese individuals, there is a decline in the

expression of activating receptors on NK cells, while inhibitory

receptors on NK cells are more highly expressed. In addition,

studies have shown that in the natural killer cells of overweight

and obese subjects, the expression of the maturation and

differentiation marker CD27 is found to be insufficient (23). Additionally, the functionality of

natural killer cells is markedly diminished in both obese animals

and humans (24). In obesity,

human adipose tissue-resident NK cells exhibit a wide range of

phenotypic variations (25).

NKT cells are capable of detecting lipid antigens

displayed by cells that express CD1d (28). Within adipose tissue, they

interact with a variety of CD1d-expressing cells, such as

adipocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells. Through these

interactions, NKT cells play a pivotal role in orchestrating either

a pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory environment. This

environment, in turn, has a significant effect on the progression

of obesity and insulin resistance. The intricate interactions of

NKT cells within adipose tissue help to shape a specialized

microenvironment that exerts influence over both obesity and

insulin resistance. A study revealed that, compared with healthy

individuals, the body weight and waist circumference of patients

with obesity do not affect the proportion of invariant (i)NKT cells

(29). However, excessive intake

of free sugars can diminish the levels of iNKT cells, thereby

leading to immune dysfunction. Particularly, free sugars from solid

foods can reduce the proportion of iNKT cells by 22% (29). The abundance of NKT cells and

iNKT cells markedly escalates subsequent to bariatric surgery,

which implies that these interventions might ameliorate

obesity-associated metabolic derangements through the recalibration

of immune cells residing in adipose tissue (30).

In individuals with obesity, there is a notable rise

in the quantity of monocytes present in the peripheral blood

(31-33). These monocytes are marked by a

high rate of glycolysis and markedly higher mitochondrial oxygen

consumption (32). Additionally,

such changes may result in abnormal cytokine secretion, including

elevated levels of IL-8 (32).

Conversely, the recruited monocytes tend to differentiate into M2

macrophages, which in turn amplifies the inflammatory response

(33). Following bariatric

surgery, the phenotypic alterations of monocytes, including the

proportion of CCR5+ monocytes, showed improvement, yet

they did not completely revert to normal levels (4). Post-bariatric surgery, the

frequency of hCD7+ monocytes in peripheral blood

exhibited a negative correlation with regaining weight (31). Among those who achieved weight

loss and sustained it, a higher proportion of hCD7+

monocytes was observed, whereas individuals who experienced weight

regain had a lower proportion (31). Following bariatric surgery,

monocytes in adipose tissue still retain certain pro-inflammatory

characteristics, which may serve as a potential mechanism

underlying weight regain and metabolic disorders (34).

Macrophages associated with lipids, known as LAMs,

release the cytokine transforming growth factor-β1. This factor,

via interaction with aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1,

instigates a loss of brown adipocyte characteristics and

facilitates the metamorphosis of brown adipose tissue into white

adipose tissue, a phenomenon often observed in conditions such as

obesity and type 2 diabetes (35). Extracellular vesicles released by

bone marrow macrophages in obese mice can lead to bone loss in lean

mice by enhancing fat formation and suppressing bone formation

through the regulation of skeletal stem/progenitor cells (36). Moreover, a newly identified

subset of adipose tissue macrophages, termed interstitial

adipose-tissue macrophages (iMAMs) has been discovered using

single-nucleus RNA sequencing (37). These iMAMs display traits of

inflammatory and metabolic activation, where protein

disulfide-isomerase A3 plays a key role in sustaining their

migratory and pro-inflammatory functions (37). Following bariatric surgery, there

is a reduction in the number of pro-inflammatory macrophages within

adipose tissue, whereas the count of anti-inflammatory macrophages,

such as M2 macrophages, increases (38). This alteration aids in

diminishing the inflammatory condition of adipose tissue and

enhancing metabolic status (38). Despite the reduction in

pro-inflammatory macrophages following bariatric surgery, the

inflammatory gene expression levels, including those of TNF and

IL-6, persist at higher levels than those observed in individuals

who are healthy (34).

Obesity has the potential to amplify the functional

activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (39-41). Obesity triggers the upregulation

of PD-1 on macrophages, leading to the suppression of anti-tumor

immunity (39). Furthermore,

obesity drives the expansion of MDSCs in ovarian cancer by

elevating IL-6 production, which strengthens the tumor's capacity

to evade immune detection (41).

However, it is regrettable that there is still a lack of research

on myeloid-derived suppressor cells following bariatric

surgery.

In obese individuals, there is a marked elevation in

the mast cell count within adipose tissue (42,43). Additionally, these mast cells

become activated and show a positive correlation with indicators of

fibrosis, inflammation and diabetes (42). By releasing a cascade of

inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and proteolytic enzymes, these

cells foster both angiogenesis and apoptosis within adipose tissue,

this dual action exacerbates the conditions of obesity and glucose

intolerance (43). Adipocytes

release adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin, which modulate

mast cell activity. Although both substances can induce the

migration of mast cells, leptin amplifies the release of histamine

and cysteinyl leukotrienes, along with the expression of chemokine

cc motif ligand 2, while adiponectin, conversely, encourages the

generation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. This

demonstrates how obesity drives chronic inflammation by altering

mast cell behavior (44).

Indeed, the major tissue injury during surgery itself is the heart

and relevant biomarkers reflect this: In heart failure, the heart's

capacity to generate energy via oxidative phosphorylation (using

oxygen) is impaired, forcing it to rely more heavily on glycolysis

or other metabolic pathways. Bariatric surgery may alleviate mast

cell (MC)-driven inflammation through the following pathways:

reducing adipocyte stress→decreasing MC activation; improving the

adipokine profile (such as lowering leptin and increasing

adiponectin)→inhibiting MC-mediated cytokine release; remodeling

the immune microenvironment of adipose tissue→reducing MCs in

visceral fat after surgery (45).

In mice undergoing high-fat diet and fecal

microbiota transplantation linked to obesity, the differentiation

of bone marrow precursor cells into MDSCs is enhanced, whereas

their potential to develop into dendritic cells (DCs) is reduced

(46). This indicates a decline

in dendritic cell populations in individuals with obesity (47). Moreover, in obese mice,

CD103+ DCs in the mesenteric lymph nodes exhibit

elevated expression of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 and TNF-α,

potentially influencing Treg expansion and directly causing Treg

loss via interactions with cyclophilin A (47). Post metabolic surgery, there is

observed a significant elevation in the proportion of myeloid

dendritic cells within the peripheral blood circulation of patients

with obesity, with these levels eventually gravitating towards

normalization after the surgical intervention (48). Following the operation, the total

count of peripheral blood DCs dropped in both patient groups but

later recovered. In the open surgery group, the proportion and

activation level of tolerogenic DCs were relatively lower, whereas

the proportion of immature dendritic cells was comparatively higher

(49).

Diet-induced obese mice show earlier infiltration of

neutrophils and enhanced formation of neutrophil extracellular

traps (NETs) during the process of fracture healing (50). NETs can hinder the process of

bone healing by activating the NOD-like receptor family pyrin

domain containing 3 inflammasome. The activation process exerts a

dual effect on the cellular landscape, simultaneously inhibiting

the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells and driving macrophages toward the M1 polarization phenotype,

a hallmark of pro-inflammatory activity (50). A strong positive correlation

exists between neutrophil count and measures of body mass index,

triglycerides and uric acid levels (51). Transformations in the peripheral

immune cell composition post-bariatric surgery are shown in

Fig. 2. Bariatric surgery

markedly affects neutrophil populations, with low-density

neutrophils showing a substantial reduction within months following

the procedure (52). The dynamic

changes in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) following

bariatric surgery reveal a significant decline in NLR within 3

months post-surgery, driven by a more marked reduction in

neutrophil counts compared with lymphocytes (53).

In patients with obesity, a decrease in eosinophils

within adipose tissue, or their complete absence as seen in

ΔdblGATA knockout mice, results in elevated body weight and

worsened insulin resistance (54,55). Eosinophils enhance the browning

and thermogenic activity of adipose tissue by releasing Th2-type

cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13 (55). However, excessive activation of

the Th2 response in the liver can contribute to fibrosis and the

progression of liver disease (54). Investigations into the efficacy

of bariatric interventions among subjects afflicted with

eosinophilic esophagitis have demonstrated that procedures such as

the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy are notably

successful in facilitating considerable weight reduction. Moreover,

these surgical interventions do not lead to an increase in the

severity of eosinophilic esophagitis symptoms following the

operations (56). However,

direct evidence on eosinophil changes remains scarce, suggesting

that bariatric surgery could potentially benefit eosinophil-related

inflammatory diseases.

Studies have delineated the sophisticated interplay

among bariatric surgery, metabolic well-being and the modulation of

the immune system. Evidence suggests that adiponectin exerts an

anti-inflammatory effect by suppressing the expression of TNF-α, a

mechanism that could be instrumental in the metabolic shifts and

inflammatory responses observed post-bariatric surgery (57). Additionally, it has been

established that obesity may dampen anti-tumor immunity by

elevating PD-1 expression on macrophages, implying that bariatric

surgery could potentially augment the immune system's

tumor-combating prowess through the modification of this pathway

(58).

The prospect of harnessing the immune

microenvironment linked to obesity for the advancement of cancer

therapies has been studied within the scientific community

(59). Discussions have centered

on the potential to target the immune milieu in obese individuals

to refine cancer treatments, a process that may be markedly

influenced by the alterations prompted by bariatric surgery

(59). Moreover, investigations

have probed the impact of obesity and adipose tissue on T-cell

responses and the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy through immune

checkpoint inhibitors, indicating that bariatric surgery could

potentially alter the dynamics between adipose tissue and T-cells,

thereby enhancing the impact of immunotherapeutic interventions

(60). Bariatric surgery

markedly improves immunotherapy response through several converging

immune mechanisms: Post-operative restoration of peripheral Tregs,

expansion of Tfh cells and downregulation of PD-1 relieve T-cell

suppression (4). Concomitant

reduction of PD-1+ macrophages and MDSCs remodels the

tumor microenvironment, converting 'cold' into 'hot' tumors

(59). A systematic review

confirmed polarization from Th1/Th17 toward Th2/Treg profiles with

decreased IL-17 and IFN-γ, thereby enhancing checkpoint-inhibitor

sensitivity and increased Breg cells secreting IL-10 and TGF-β,

further dampening pro-inflammatory responses (61). Additionally, recovery of

MAIT-cell frequencies and diminished IL-17 indicate reprogramming

of the metabolic-immune axis that synergistically strengthens

anti-tumor immunity (62).

Furthermore, the intricate effects of obesity on

T-cell functionality during tumor progression and immune checkpoint

blockade have been subjected to intense examination, underscoring

the necessity for a more nuanced comprehension of how bariatric

surgery could influence these interactions by modulating T-cell

functions to refine immunotherapeutic strategies (63). To a greater extent, the

administration of gut-targeted therapies, such as probiotics and

prebiotics, can markedly optimize the health of the gut microbiota,

thereby augmenting the integrity of the intestinal barrier and

exerting a regulatory effect on immune responses (64).

According to current research, there are significant

differences in immune responses to various weight-loss strategies

(pharmacological, dietary and exercise interventions) and to

biological markers such as age and sex. The differences are showed

in Table I (65-70).

Glycolysis is one of the most studied metabolic

pathways in immune cells, with its high metabolic flux being a

hallmark of activated immune cells, especially in pro-inflammatory

immune cells (71).

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a key subunit of HIF-1, is

activated in hypoxic environments and can upregulate glycolysis in

immune cells (72). Moreover, it

exerts a substantial influence on oxidative stress, cancer

progression and a myriad of other diseases (72). Research has demonstrated that

inhibiting HIF-1α can effectively diminish glycolysis in immune

cells, including macrophages and T cells (73). This finding suggests a promising

therapeutic strategy for addressing autoimmune diseases, metabolic

disorders and various inflammatory conditions.

Within the intricate landscape of immunometabolic

regulation, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling

cascade emerges as a pivotal actor orchestrating glycolysis within

immune cells, exerting its influence through downstream effectors

such as 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3

(PFKFB3) and glucose transporter type 1 (74-76). PFKFB3, a sentinel enzyme

governing glycolytic flux, is subject to activation by the PI3K/Akt

axis, thereby amplifying the glycolytic program (78). This metabolic amplification can

be attenuated by specific PFKFB3 inhibitors, which have

demonstrated efficacy in diminishing both glycolysis and the

pro-inflammatory vigor of immune cells (74-76).

In the aftermath of bariatric surgery, patients

undergo substantial metabolic transformations that are inextricably

linked to glycolysis. The elevation of bile acid levels

post-surgery precipitates the activation of receptors such as TGR5

and farnesoid X receptor (FXR), thereby exerting a profound

influence on glycolytic metabolism (79). For example, the activation of

TGR5 catalyzes the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1, which in

turn modulates glucose metabolism (79). Concurrently, an enhancement in

insulin sensitivity is observed, as evidenced by the upregulation

of hepatic lipid oxidation gene expression and the downregulation

of lipogenic gene expression, both of which have a significant

impact on glycolysis (79).

These metabolic modifications present novel avenues for targeted

therapeutic interventions following bariatric surgery.

In the realm of oncology, the metabolic alterations

elicited by bariatric surgery may have a substantial effect on the

glycolytic metabolism of tumor cells. Extant research posits that

tumor cells predominantly engage in aerobic glycolysis as a means

of metabolic reprogramming (80). By targeting glycolysis-related

metabolic enzymes, such as lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A) and

hexokinase 2 (HK2), it is possible to curtail tumor progression

(80). For instance, the

inhibition of LDH-A results in a reduction of lactate production,

which subsequently mitigates immune suppression and fortifies

anti-tumor immune responses (80). Moreover, post-surgery

improvements in pancreatic β-cell function lead to more efficient

and coordinated insulin secretion. The regulation of glycolysis can

further optimize insulin secretion and enhance glucose control

(79).

Strategies for glycolysis-targeted treatment

encompass the development of specific metabolic enzyme inhibitors,

such as those targeting LDH-A and HK2, to suppress tumor cell

glycolysis, diminish lactate production and augment anti-tumor

immune responses (81).

Additionally, modulating bile acid levels or activating bile acid

receptors like TGR5 and FXR can indirectly influence glycolytic

metabolism, thereby improving glucose control and insulin

sensitivity. The potential applications of these strategies merit

further exploration (79).

Therapeutic targeting of immunometabolism offers a

novel approach to treat various diseases, including cancer,

autoimmune disorders and inflammatory conditions (82). Several strategies have emerged

from preclinical and clinical studies. Modulation of oxidative

phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is one such strategy. Downregulating

OXPHOS in immune cells, particularly in Tregs has shown potential

in cancer immunotherapy. For instance, targeting FABP5 to reduce

OXPHOS in Tregs can impair their immunosuppressive function,

enhancing anti-tumor immunity (83). Similarly, OXPHOS inhibitors such

as IACS-010759 have demonstrated efficacy in targeting cancer cells

with high Myc activity, although the exact mechanism remains

unclear (84,85). Conversely, upregulating OXPHOS in

immune cells, such as CD8+T cells, can improve their

anti-tumor activity. For example, incorporating the 4-1BB domain

into chimeric antigen receptor T cells upregulates OXPHOS, leading

to enhanced persistence and efficacy in cancer immunotherapy

(86). Additionally, drugs like

NX-13, which upregulate OXPHOS, have shown anti-inflammatory

effects in ulcerative colitis (87,88).

In the realm of cancer therapeutics, the inhibition

of glycolysis in immune cells has garnered significant attention.

However, given the immunosuppressive milieu that characterizes the

cancer microenvironment, the strategy of inhibiting immune cell

glycolysis in cancer, excluding immune cell-derived tumors,

requires nuanced consideration. JHU083, a glutamine antagonist,

exemplifies a dual-action inhibitor capable of suppressing

glycolysis in both tumor cells and effector CD8+T cells

(89). Intriguingly, the

reduction of glycolysis in CD8+T cells precipitates an

upregulation of OXPHOS, thereby activating potent anti-tumor immune

responses (89,90). This phenomenon is inextricably

intertwined with the replenishment of tricarboxylic acid cycle

intermediates, a mechanism that has been thoroughly investigated

and elucidated (90).

In a similar vein, L-arginine imitates the effects

of glutamine antagonists by catalyzing a metabolic transition from

glycolysis to OXPHOS in effector T cells, thereby enhancing their

anti-tumor efficacy (91). HK2,

a crucial rate-limiting enzyme in the glycolytic pathway, has

garnered significant attention as a potential therapeutic target in

cancer treatment (92). The

inhibition of HK2 has been shown to suppress glycolysis, thereby

disrupting the expression of PD-L1 and subsequently reactivating

CD8+T cells (93). In

summary, rather than merely suppressing inflammation, glycolysis

inhibitors have exhibited anti-tumor immune effects by enhancing

OXPHOS. This phenomenon is likely due to the non-specific targeting

of glycometabolism in immune cells by existing inhibitors. In the

aftermath of bariatric surgery, adipose tissue undergoes a marked

enhancement in mitochondrial function, characterized by an

upregulation of gene expression associated with OXPHOS (94). This, in turn, amplifies the

oxidative capacity of adipose tissue, facilitating fatty acid

oxidation and energy expenditure. These metabolic alterations not

only contribute to weight reduction but also exert a salutary

effect on insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health.

Furthermore, obesity is frequently accompanied by mitochondrial

dysfunction, a condition that bariatric surgery can effectively

ameliorate by diminishing mitochondrial fragmentation and

bolstering mitochondrial OXPHOS function (95). In the context of oncology, OXPHOS

emerges as a pivotal metabolic vulnerability for certain tumor

subtypes, such as lung cancer cells harboring SWI/SNF mutations and

prostate cancer cells with PTEN deficiency, as these cells are

highly reliant on OXPHOS for their proliferation and survival,

OXPHOS inhibitors, including Gboxin and berberine, have been

demonstrated to exert a potent inhibitory effect on tumor growth

(96,97). Additionally, the OXPHOS activity

of tumor cells in obese individuals may be attenuated due to the

improved mitochondrial function, thereby reducing the recurrence

rate of tumors. Consequently, targeting OXPHOS presents a novel and

promising therapeutic strategy for drug-resistant tumors, offering

the potential to enhance anti-tumor efficacy (95). The present review posits that

these findings furnish a theoretical foundation for the development

of therapeutic strategies targeting OXPHOS, which holds promise for

playing a significant role in the treatment of metabolic disorders

and oncology.

Lipid metabolism modulation is another area of

interest. Modulating fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in immune cells has

been explored in common diseases, including cancer, autoimmune

diseases, metabolic disease, atherosclerosis and lung inflammation

(78,86,98-105). Downregulating FAO in M2

macrophages can alleviate immunosuppression in cancer, while

upregulating FAO in macrophages can promote anti-inflammatory

effects in conditions like ulcerative colitis (105). peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor α activators, such as fibrates,

have shown promise in enhancing FAO and reducing inflammation.

Inhibiting lipid synthesis in immune cells, particularly in Tregs

and CD8+T cells, has been shown to suppress

immunosuppression and pro-inflammatory responses, respectively

(101,106,107). For example, inhibiting SREBP

signaling in Tregs can reduce tumor growth without causing

autoimmune toxicity (108).

Bariatric surgery, by ameliorating lipid metabolism, markedly

reduces serum cholesterol levels, enhances the oxidative capacity

of adipose tissue and promotes fatty acid oxidation and energy

expenditure, thereby alleviating body weight and improving insulin

sensitivity and overall metabolic health (109).

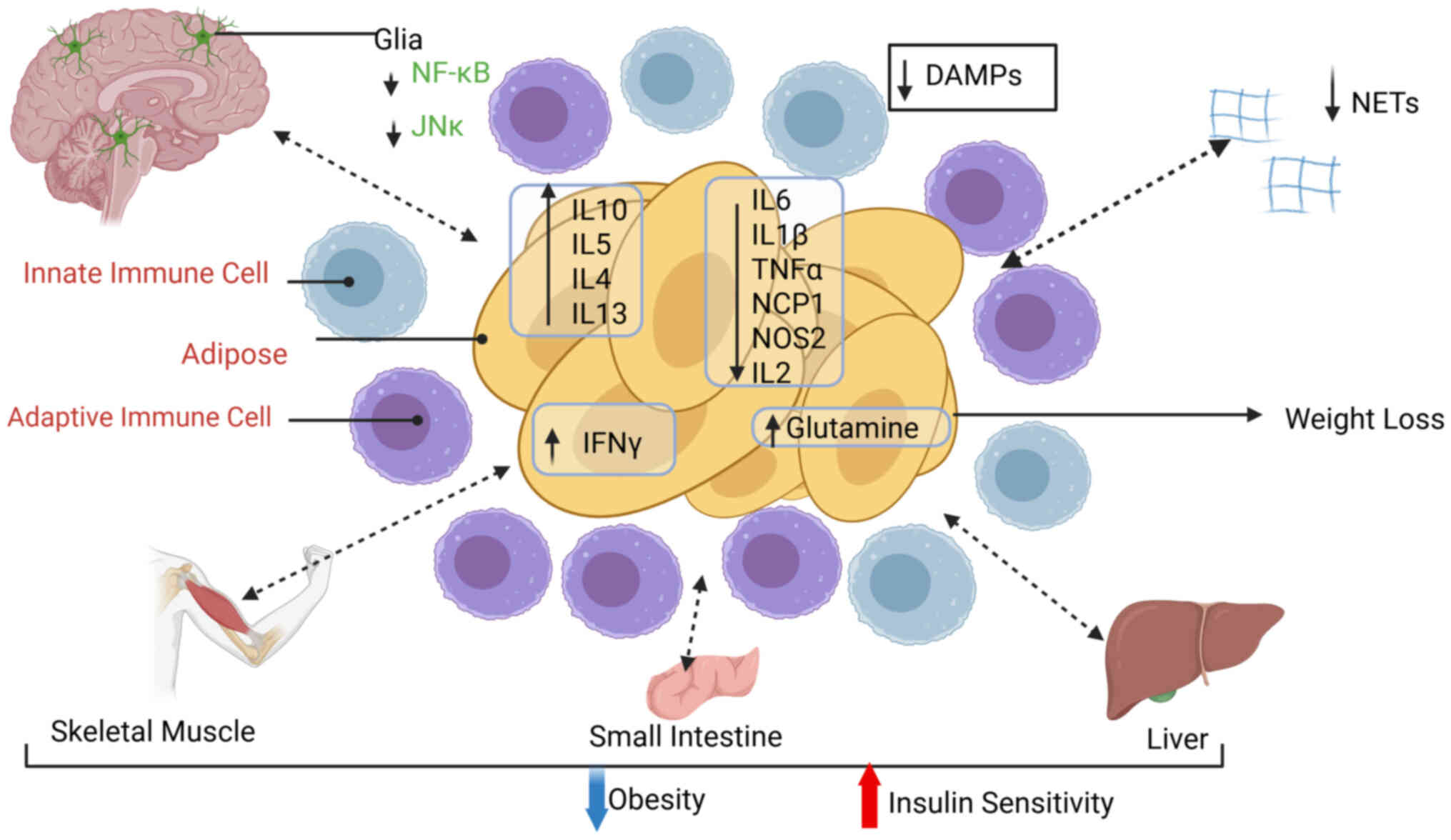

In the context of obesity-associated chronic

low-grade inflammation, both macrophages and T cells are

prominently present within adipose tissue, exerting significant

influence on the inception and propagation of inflammatory

processes (18). Post-bariatric

surgery, a notable regulatory shift occurs in macrophage function,

characterized by a polarization transition from the

pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2

phenotype. This transformation effectively curtails the generation

of inflammatory cytokines (131).

Concurrently, the signaling pathways governing T

cell behavior undergo substantial alterations (132). Specifically, the expression

profiles of several key genes, including CXCR1, CXCR2, CCR7, IL7R

and G-protein coupled receptor 97 (GPR97), are modulated. These

genetic changes subsequently affect the activation and functional

dynamics of T cells, thereby contributing to a mitigated

inflammatory response (133).

Moreover, the cytokine IL-6, which exhibits a

complex dual role in obesity-related inflammation, is subject to

significant changes post-surgery (134). In obese individuals, elevated

IL-6 levels are typically associated with heightened inflammation

and insulin resistance (134).

However, following bariatric intervention, the levels and

functional attributes of IL-6 are reconfigured. The

pro-inflammatory effects of IL-6 are attenuated, while its

beneficial metabolic regulatory functions are preserved. Similarly,

TNF-α, a pivotal pro-inflammatory cytokine intricately linked to

obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance, experiences

a marked reduction in concentration following bariatric surgery

(135). This decline in TNF-α

levels plays a crucial role in dampening the overall inflammatory

cascade (135).

In individuals with obesity, visceral adipose tissue

exhibits markedly augmented IL-16 expression, which is intimately

intertwined with a state of smoldering, low-grade inflammation

(136). Following bariatric

surgery, IL-16 undergoes an early, transient surge; yet, as

adiposity and body mass progressively wane, its concentrations

regress to, or even below, pre-operative baselines.

Immunomodulatory interventions that target IL-16 or its processing

proteases could emerge as an adjunct anti-inflammatory strategy

beyond bariatric surgery itself (137). Collectively, these dynamics

intimate that bariatric surgery exerts an indirect but potent

anti-inflammatory effect by alleviating the adipose-tissue burden,

thereby dampening IL-16-driven inflammatory cascades, ameliorating

metabolic homeostasis and mitigating post-surgical inflammatory

sequelae (138).

In addition to these cellular and cytokine changes,

the activity of key signaling pathways is also modulated. The

Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, a primary initiator of

inflammation in adipose tissue, is suppressed post-surgery, leading

to a reduction in inflammatory cytokine production (139). The Janus kinase-signal

transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway, which

is integral to the regulation of both adipose tissue inflammation

and metabolic homeostasis, also undergoes functional alterations

(140). These changes

collectively contribute to the overall attenuation of the

inflammatory response observed following bariatric surgical

interventions.

Peculiarly, recent studies show that residual

inflammatory 'imprints' can epigenetically reprogram innate and

adaptive immunity, leading to long-term reductions in vaccine

efficacy and immunotherapy success: Prior infection- or

inflammation-induced suppressive programs persist for at least a

month and hinder T-cell expansion and dendritic-cell priming, while

repeated mRNA vaccination in a chronic inflammatory milieu sustains

IFN-α/IL-6 signals that exacerbate inflammation and blunt

subsequent therapeutic responses (141-143).

Obesity is associated with IL-7Rα overexpression,

which disrupts immune cell function (27). Targeting IL-7Rα with specific

antibodies can stabilize T cells, reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines

and control obesity-related inflammation (27). This approach is well-tolerated in

healthy individuals and may be applicable to patients with obesity.

Other immune cell surface molecules, such as CXCR1, CXCR2, CCR7,

IL7R and GPR97, are also being explored as potential targets to

enhance immune cell activation and function, thereby reducing

inflammation (132).

Obesity also alters the gut microbiota and

bariatric surgery can improve its composition (64). Supplementing with specific

probiotics, like those containing Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium species, can further lower serum TNF-α

levels and increase postoperative weight loss (64). Probiotics can modulate cytokine

levels by increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines and decreasing

pro-inflammatory cytokines, while simultaneously enhancing

intestinal barrier function, reducing bacterial translocation and

attenuating systemic inflammation (144,145). Additionally, metabolic

reprogramming of immune cells following bariatric surgery,

particularly shifting T cells and B cells from a pro-inflammatory

to an anti-inflammatory state, may help alleviate chronic

inflammation in obesity (118).

Lastly, while inflammation is a necessary part of the body's

defense against injury and infection, surgical procedures and the

anesthetic agents used can either enhance or alter biomarkers

(146,147). Evidence indicates that

anesthesia modality markedly modulates perioperative immunity: A

meta-analysis found propofol TIVA more effectively suppressed

pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) and elevated IL-10 than

sevoflurane, while a hysterectomy trial showed spinal vs. general

anesthesia further reduced postoperative IL-6, CRP and MDA while

preserving antioxidant enzymes. Thus, both propofol over

sevoflurane and spinal over general anesthesia confer

immunoprotection by attenuating systemic inflammation and oxidative

stress (146,147).

New progress has been made in the research of

intracellular target therapy of immune cells following bariatric

surgery. IL-27 enhances the anti-tumor function of CD8+T

cells and inhibits immune suppressor factors by activating the

STAT1/3 signaling pathway (119). It also acts on adipocytes to

promote the expression of uncoupling protein 1 via the

p38MAPK/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator

1-α pathway, thereby regulating obesity (18). In addition, the pro-inflammatory

characteristics of circulating T cells in patients with obesity are

improved following bariatric surgery, with the recovery of

CD4+ Treg cell levels and increased proliferation and

activation of Tfh and B cells (4). The activation status and expression

changes of immune checkpoint molecules in obesity-related T cell

subsets may serve as potential targets (4). In a study, it was found that

glutamate receptor scaffold proteins (PSD-95 and PICKL) were

involved in the anchoring and transport of glutamate receptors and

their PDZ domains have become therapeutic targets for various

central nervous system diseases (148).

Bariatric surgery is no longer simply a mechanical

restriction or malabsorptive procedure; it functions as a

systems-level 'immuno-metabolic reboot'. By simultaneously

correcting the chronic, low-grade inflammatory tone of obesity and

re-wiring the bioenergetic circuitry of virtually every circulating

immune subset, surgery converts pathologic adipose-immune

cross-talk into a homeostatic dialogue that sustains weight loss

and metabolic remission. Over the next decade, three converging

developments will redefine post-surgical care, besides single-cell

multi-omics and AI-driven trajectory mapping will allow real-time

identification of patients who retain pro-inflammatory immune

'scars', enabling precision rescue therapy before weight regain or

diabetes relapse occurs; pharmacologic fine-tuning of discrete

metabolic checkpoints, glycolytic rate-limiting enzymes, OXPHOS

modulators and glutamine/FAO switches, will be combined with

microbiota-directed interventions to accelerate functional

maturation of Treg, NK and antigen-presenting cell compartments and

these same immuno-metabolic insights will be exported to oncology:

Leveraging the bariatric-induced reduction in PD-1hi macrophages

and MDSCs to convert the obesity-associated 'cold' tumor

microenvironment into one that is highly responsive to

immune-checkpoint blockade. Ultimately, bariatric surgery will

evolve from a last-resort metabolic operation into a programmable

gateway for lifelong immuno-metabolic precision medicine,

delivering not just sustained weight loss, but durable protection

against diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Not applicable.

YS and KS were both responsible for the conception

and writing of the present review. RY contributed to the design of

the figures. HX contributed to literature search and collating

references. CL was responsible for language editing and for

critical revision and for making substantial contributions to

conception and design. YD was responsible for preparing analysis

and interpretation of data and stylistic refinement. YR and YZ were

both in charge of the conception and design of the present review.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present review was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82370601) and Natural Science

Foundation of Sichuan Province (grant no. 2025NSFJQ0066).

|

1

|

Schulze MB and Stefan N: Metabolically

healthy obesity: From epidemiology and mechanisms to clinical

implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 20:633–646. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang P, Watari K and Karin M: Innate

immune cells link dietary cues to normal and abnormal metabolic

regulation. Nat Immunol. 26:29–41. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Moris D, Barfield R, Chan C, Chasse S,

Stempora L, Xie J, Plichta JK, Thacker J, Harpole DH, Purves T, et

al: Immune phenotype and postoperative complications after elective

surgery. Ann Surg. 278:873–882. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Barbosa P, Pinho A, Lázaro A, Paula D,

Tralhão JG, Paiva A, Pereira MJ, Carvalho E and Laranjeira P:

Bariatric surgery induces alterations in the immune profile of

peripheral blood T cells. Biomolecules. 14:2192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mohammadzadeh N, Razavi S and Ebrahimipour

G: Impact of bariatric surgery on gut microbiota composition in

obese patients compared to healthy controls. AMB Express.

14:1152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rivera-Carranza T, Azaola-Espinosa A,

Bojalil-Parra R, Zúñiga-León E, León-Téllez-Girón A,

Rojano-Rodríguez ME and Nájera-Medina O: Immunometabolic changes

following gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: A comparative

study. Obes Surg. 35:481–495. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shaikh SR, Beck MA, Alwarawrah Y and

MacIver NJ: Emerging mechanisms of obesity-associated immune

dysfunction. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 20:136–148. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hart A, Sun Y, Titcomb TJ, Liu B, Smith

JK, Correia MLG, Snetselaar LG, Zhu Z and Bao W: Association

between preoperative serum albumin levels with risk of death and

postoperative complications after bariatric surgery: A

retrospective cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 18:928–934. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hart JWH, Takken R, Hogewoning CRC, Biter

LU, Apers JA, Zengerink H, Dunkelgrün M and Verhoef C: Markers for

major complications at day-one postoperative in fast-track

metabolic surgery: Updated metabolic checklist. Obes Surg.

33:3008–3016. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Riva-Moscoso A, Martinez-Rivera RN,

Cotrina-Susanibar G, Príncipe-Meneses FS, Urrunaga-Pastor D,

Salinas-Sedo G and Toro-Huamanchumo CJ: Factors associated with

nutritional deficiency biomarkers in candidates for bariatric

surgery: A cross-sectional study in a peruvian high-resolution

clinic. Nutrients. 14:822021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Giovenzana A, Bezzecchi E, Bichisecchi A,

Cardellini S, Ragogna F, Pedica F, Invernizzi F, Di Filippo L,

Tomajer V, Aleotti F, et al: Fat-to-blood recirculation of

partially dysfunctional PD-1(+)CD4 Tconv cells is associated with

dysglycemia in human obesity. iScience. 27:1090322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ma Q, Ran H, Li Y, Lu Y, Liu X, Huang H,

Yang W, Yu L, Chen P, Huang X, et al: Circulating Th1/17 cells

serve as a biomarker of disease severity and a target for early

intervention in AChR-MG patients. Clin Immunol. 218:1084922020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wood S, Branch J, Vasquez P, DeGuzman MM,

Brown A, Sagcal-Gironella AC, Singla S, Ramirez A and Vogel TP:

Th17/1 and ex-Th17 cells are detected in patients with

polyarticular juvenile arthritis and increase following treatment.

Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 22:322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shirakawa K and Sano M: Drastic

transformation of visceral adipose tissue and peripheral CD4 T

cells in obesity. Front Immunol. 13:10447372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Elkins C, Ye C, Sivasami P, Mulpur R,

Diaz-Saldana PP, Peng A, Xu M, Chiang YP, Moll S, Rivera-Rodriguez

DE, et al: Obesity reshapes regulatory T cells in the visceral

adipose tissue by disrupting cellular cholesterol homeostasis. Sci

Immunol. 10:eadl49092025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wijngaarden LH, Taselaar AE, Nuijten F,

van der Harst E, Klaassen RA, Kuijper TM, Jongbloed F, Ambagtsheer

G, Klepper M, Ijzermans JNM, et al: T and B cell composition and

cytokine producing capacity before and after bariatric surgery.

Front Immunol. 13:8882782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fernández-Ruiz I: Obesity alters

cholesterol homeostasis in regulatory T cells of visceral adipose

tissue. Nat Rev Cardiol. 22:1462025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Villarreal-Calderon JR, Cuellar-Tamez R,

Castillo EC, Luna-Ceron E, García-Rivas G and Elizondo-Montemayor

L: Metabolic shift precedes the resolution of inflammation in a

cohort of patients undergoing bariatric and metabolic surgery. Sci

Rep. 11:121272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jalilvand A, Blaszczak A, Bradley D, Liu

J, Wright V, Needleman B, Hsueh W and Noria S: Low visceral adipose

tissue regulatory T cells are associated with higher comorbidity

severity in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc.

35:3131–3138. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Frasca D: Obesity accelerates age defects

in human B cells and induces autoimmunity. Immunometabolism.

4:e2200102022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Artimovič P, Špaková I, Macejková E,

Pribulová T, Rabajdová M, Mareková M and Zavacká M: The ability of

microRNAs to regulate the immune response in ischemia/reperfusion

inflammatory pathways. Genes Immun. 25:277–296. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Šlisere B, Arisova M, Aizbalte O, Salmiņa

MM, Zolovs M, Levenšteins M, Mukāns M, Troickis I, Meija L,

Lejnieks A, et al: Distinct B cell profiles characterise healthy

weight and obesity pre- and post-bariatric surgery. Int J Obes

(Lond). 47:970–978. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Naujoks W, Quandt D, Hauffe A, Kielstein

H, Bähr I and Spielmann J: Characterization of surface receptor

expression and cytotoxicity of human NK cells and NK cell subsets

in overweight and obese humans. Front Immunol. 11:5732002020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bähr I, Spielmann J, Quandt D and

Kielstein H: Obesity-associated alterations of natural killer cells

and immunosurveillance of cancer. Front Immunol. 11:2452020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Haugstøyl ME, Cornillet M, Strand K,

Stiglund N, Sun D, Lawrence-Archer L, Hjellestad ID, Busch C,

Mellgren G, Björkström NK and Fernø J: Phenotypic diversity of

human adipose tissue-resident NK cells in obesity. Front Immunol.

14:11303702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang YY, Chang EQ, Zhu RL, Liu XZ, Wang

GZ, Li NT, Zhang W, Zhou J, Wang XD, Sun MY and Zhang JQ: An atlas

of dynamic peripheral blood mononuclear cell landscapes in human

perioperative anaesthesia/surgery. Clin Transl Med. 12:e6632022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gihring A, Gärtner F, Mayer L, Roth A,

Abdelrasoul H, Kornmann M, Elad L and Knippschild U: Influence of

bariatric surgery on the peripheral blood immune system of female

patients with morbid obesity revealed by high-dimensional mass

cytometry. Front Immunol. 14:11318932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Satoh M and Iwabuchi K: Contribution of

NKT cells and CD1d-expressing cells in obesity-associated adipose

tissue inflammation. Front Immunol. 15:13658432024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Alhamawi RM, Almutawif YA, Aloufi BH,

Alotaibi JF, Alharbi MF, Alsrani NM, Alinizy RM, Almutairi WS,

Alaswad WA, Eid HMA and Mumena WA: Free sugar intake is associated

with reduced proportion of circulating invariant natural killer T

cells among women experiencing overweight and obesity. Front

Immunol. 15:13583412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Van Kaer L, Parekh VV and Wu L: Invariant

natural killer T cells: Bridging innate and adaptive immunity. Cell

Tissue Res. 343:43–55. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhou HY, Feng X, Wang LW, Zhou R, Sun H,

Chen X, Lu RB, Huang Y, Guo Q and Luo XH: Bone marrow immune cells

respond to fluctuating nutritional stress to constrain weight

regain. Cell Metab. 35:1915–1930.e8. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Radushev V, Karkossa I, Berg J, von Bergen

M, Engelmann B, Rolle-Kampczyk U, Blüher M, Wagner U, Schubert K

and Rossol M: Dysregulated cytokine and oxidative response in

hyper-glycolytic monocytes in obesity. Front Immunol.

15:14165432024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Blaszkiewicz M, Gunsch G, Willows JW,

Gardner ML, Sepeda JA, Sas AR and Townsend KL: Adipose tissue

myeloid-lineage neuroimmune cells express genes important for

neural plasticity and regulate adipose innervation. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:8649252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hinte LC, Castellano-Castillo D, Ghosh A,

Melrose K, Gasser E, Noé F, Massier L, Dong H, Sun W, Hoffmann A,

et al: Adipose tissue retains an epigenetic memory of obesity after

weight loss. Nature. 636:457–465. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sciarretta F, Ninni A, Zaccaria F,

Chiurchiù V, Bertola A, Karlinsey K, Jia W, Ceci V, Di Biagio C, Xu

Z, et al: Lipid-associated macrophages reshape BAT cell identity in

obesity. Cell Rep. 43:1144472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Luo JH, Wang FX, Zhao JW, Yang CL, Rong

SJ, Lu WY, Chen QJ, Zhou Q, Xiao J, Wang YN, et al: PDIA3 defines a

novel subset of adipose macrophages to exacerbate the development

of obesity and metabolic disorders. Cell Metab. 36:2262–2280.e5.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

He C, Hu C, He WZ, Sun YC, Jiang Y, Liu L,

Hou J, Chen KX, Jiao YR, Huang M, et al: Macrophage-derived

extracellular vesicles regulate skeletal stem/progenitor Cell

lineage fate and bone deterioration in obesity. Bioact Mater.

36:508–523. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang T, Zhang Y, Duan C, Liu H, Wang D,

Liang Q, Chen X, Ma J, Cheng K, Chen Y, et al: CD300E(+)

macrophages facilitate liver regeneration after splenectomy in

decompensated cirrhotic patients. Exp Mol Med. 57:72–85. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bader JE, Wolf MM, Lupica-Tondo GL, Madden

MZ, Reinfeld BI, Arner EN, Hathaway ES, Steiner KK, Needle GA,

Hatem Z, et al: Author Correction: Obesity induces PD-1 on

macrophages to suppress anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 631:E162024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu W, Li B, Liu D, Zhao B, Sun G and Ding

J: Obesity correlates with the immunosuppressive ILC2s-MDSCs axis

in advanced breast cancer. Immun Inflamm Dis. 12:e11962024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yang Q, Yu B, Kang J, Li A and Sun J:

Obesity promotes tumor immune evasion in ovarian cancer through

increased production of myeloid-derived suppressor cells via IL-6.

Cancer Manag Res. 13:7355–7363. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Divoux A, Moutel S, Poitou C, Lacasa D,

Veyrie N, Aissat A, Arock M, Guerre-Millo M and Clément K: Mast

cells in human adipose tissue: link with morbid obesity,

inflammatory status, and diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

97:E1677–E1685. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Liu J, Divoux A, Sun J, Zhang J, Clément

K, Glickman JN, Sukhova GK, Wolters PJ, Du J, Gorgun CZ, et al:

Genetic deficiency and pharmacological stabilization of mast cells

reduce diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Nat Med.

15:940–945. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Milling S: Adipokines and the control of

mast cell functions: From obesity to inflammation? Immunology.

158:1–2. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Arivazhagan L, Ruiz HH, Wilson RA,

Manigrasso MB, Gugger PF, Fisher EA, Moore KJ, Ramasamy R and

Schmidt AM: An eclectic cast of cellular actors orchestrates innate

immune responses in the mechanisms driving obesity and metabolic

perturbation. Circ Res. 126:1565–1589. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen J, Liu X, Zou Y, Gong J, Ge Z, Lin X,

Zhang W, Huang H, Zhao J, Saw PE, et al: A high-fat diet promotes

cancer progression by inducing gut microbiota-mediated leucine

production and PMN-MDSC differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

121:e23067761212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li C, Wang G, Sivasami P, Ramirez RN,

Zhang Y, Benoist C and Mathis D: Interferon-α-producing

plasmacytoid dendritic cells drive the loss of adipose tissue

regulatory T cells during obesity. Cell Metab. 33:1610–1623.e5.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Zhang J, Chen X, Liu W, Zhang C, Xiang Y,

Liu S and Zhou Z: Metabolic surgery improves the unbalanced

proportion of peripheral blood myeloid dendritic cells and T

lymphocytes in obese patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 185:819–829. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

McAuliffe PF, Efron PA, Scumpia PO, Uchida

T, Mutschlecner SC, Rout WR, Moldawer LL and Cendan JC: Varying

blood monocyte and dendritic cell responses after laparoscopic

versus open gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 15:1424–1431. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhao X, Wang Q, Wang W and Lu S: Increased

neutrophil extracellular traps caused by diet-induced obesity delay

fracture healing. FASEB J. 38:e701262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lyu H, Fan N, Wen H, Zhang X, Mao H, Bian

Q and Chen J: Interplay between BMI, neutrophil, triglyceride and

uric acid: A case-control study and bidirectional multivariate

mendelian randomization analysis. Nutr Metab (Lond). 22:72025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Roberts CF and Sheu EG: Low density, high

impact? Neutrophil changes in obesity and bariatric surgery.

EBioMedicine. 79:1039882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chi PJ, Wu KT, Chen PJ, Chen CY, Su YC,

Yang CY and Chen JH: The serial changes of Neutrophile-Lymphocyte

Ratio and correlation to weight loss after Laparoscopic Sleeve

Gastrectomy. Front Surg. 9:9398572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Hu Y and Chakarov S: Eosinophils in

obesity and obesity-associated disorders. Discov Immunol.

2:kyad0222023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Oliveira MC, Silveira ALM, de Oliveira

ACC, Lana JP, Costa KA, Vieira É LM, Pinho V, Teixeira MM,

Merabtene F, Marcelin G, et al: Eosinophils protect from metabolic

alterations triggered by obesity. Metabolism. 146:1556132023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Deiss-Yehiely N, Lidor A and Hillman L:

Outcomes of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis undergoing

bariatric surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 28:1706–1708. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yuan B, Huang L, Yan M, Zhang S, Zhang Y,

Jin B, Ma Y and Luo Z: Adiponectin downregulates TNF-α expression

in degenerated intervertebral discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).

43:E381–E389. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Bader JE, Wolf MM, Lupica-Tondo GL, Madden

MZ, Reinfeld BI, Arner EN, Hathaway ES, Steiner KK, Needle GA,

Hatem Z, et al: Obesity induces PD-1 on macrophages to suppress

anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 630:968–975. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Desharnais L, Walsh LA and Quail DF:

Exploiting the obesity-associated immune microenvironment for

cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 229:1079232022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Pasquarelli-do-Nascimento G, Machado SA,

de Carvalho JMA and Magalhães KG: Obesity and adipose tissue impact

on T-cell response and cancer immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

Immunother Adv. 2:ltac0152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Villarreal-Calderón JR, Cuéllar RX,

Ramos-González MR, Rubio-Infante N, Castillo EC,

Elizondo-Montemayor L and García-Rivas G: Interplay between the

adaptive immune system and insulin resistance in weight loss

induced by bariatric surgery. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2019:39407392019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Conroy MJ, Dunne MR, Donohoe CL and

Reynolds JV: Obesity-associated cancer: An immunological

perspective. Proc Nutr Soc. 75:125–138. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Wang Z, Aguilar EG, Luna JI, Dunai C,

Khuat LT, Le CT, Mirsoian A, Minnar CM, Stoffel KM, Sturgill IR, et

al: Paradoxical effects of obesity on T cell function during tumor

progression and PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Nat Med. 25:141–151.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

64

|

Galyean S, Sawant D and Shin AC:

Immunometabolism, micronutrients, and bariatric surgery: The use of

transcriptomics and microbiota-targeted therapies. Mediators

Inflamm. 2020:88620342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Chen DB and Wang W: Human placental

microRNAs and preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 88:1302013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Mehrdad M, Norouzy A, Safarian M, Nikbakht

HA, Gholamalizadeh M and Mahmoudi M: The antiviral immune defense

may be adversely influenced by weight loss through a calorie

restriction program in obese women. Am J Transl Res.

13:10404–10412. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ji J, Fotros D, Sohouli MH, Velu P, Fatahi

S and Liu Y: The effect of a ketogenic diet on inflammation-related

markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 83:40–58. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Nemet I and Monnier VM: Vitamin C

degradation products and pathways in the human lens. J Biol Chem.

286:37128–37136. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhu R, Craciun I, Bernhards-Werge J, Jalo

E, Poppitt SD, Silvestre MP, Huttunen-Lenz M, McNarry MA, Stratton

G, Handjiev S, et al: Age- and sex-specific effects of a long-term

lifestyle intervention on body weight and cardiometabolic health

markers in adults with prediabetes: results from the diabetes

prevention study PREVIEW. Diabetologia. 65:1262–1277. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Potenza L, Vallerini D, Barozzi P, Riva G,

Gilioli A, Forghieri F, Candoni A, Cesaro S, Quadrelli C, Maertens

J, et al: Mucorales-Specific T cells in patients with hematologic

malignancies. PLoS One. 11:e01491082016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson

KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Martens JH, Rao

NA, Aghajanirefah A, et al: mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic

glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science.

345:12506842014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Ke X, Fei F, Chen Y, Xu L, Zhang Z, Huang

Q, Zhang H, Yang H, Chen Z and Xing J: Hypoxia upregulates CD147

through a combined effect of HIF-1α and Sp1 to promote glycolysis

and tumor progression in epithelial solid tumors. Carcinogenesis.

33:1598–1607. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Liu L, Wang Y, Bai R, Yang K and Tian Z:

MiR-186 inhibited aerobic glycolysis in gastric cancer via HIF-1α

regulation. Oncogenesis. 6:e3182017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Zhou Z, Plug LG, Patente TA, de

Jonge-Muller ESM, Elmagd AA, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Everts B,

Barnhoorn MC and Hawinkels LJAC: Increased stromal PFKFB3-mediated

glycolysis in inflammatory bowel disease contributes to intestinal

inflammation. Front Immunol. 13:9660672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Hu X, Xu Q, Wan H, Hu Y, Xing S, Yang H,

Gao Y and He Z: PI3K-Akt-mTOR/PFKFB3 pathway mediated lung

fibroblast aerobic glycolysis and collagen synthesis in

lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Lab Invest.

100:801–811. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

He Q, Yin J, Zou B and Guo H: WIN55212-2

alleviates acute lung injury by inhibiting macrophage glycolysis

through the miR-29b-3p/FOXO3/PFKFB3 axis. Mol Immunol. 149:119–128.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zhai GY, Qie SY, Guo QY, Qi Y and Zhou YJ:

sDR5-Fc inhibits macrophage M1 polarization by blocking the

glycolysis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 18:271–280. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Hao S, Zhang S, Ye J, Chen L, Wang Y, Pei

S, Zhu Q, Xu J, Tao Y, Zhou N, et al: Goliath induces inflammation

in obese mice by linking fatty acid β-oxidation to glycolysis. EMBO

Rep. 24:e569322023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Sandoval DA and Patti ME: Glucose

metabolism after bariatric surgery: Implications for T2DM remission

and hypoglycaemia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 19:164–176. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Zhou D, Duan Z, Li Z, Ge F, Wei R and Kong

L: The significance of glycolysis in tumor progression and its

relationship with the tumor microenvironment. Front Pharmacol.

13:10917792022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

81

|

DeBerardinis RJ and Chandel NS:

Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv. 2:e16002002016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Cadassou O and Jordheim LP: OXPHOS

inhibitors, metabolism and targeted therapies in cancer. Biochem

Pharmacol. 211:1155312023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Pan Y, Tian T, Park CO, Lofftus SY, Mei S,

Liu X, Luo C, O'Malley JT, Gehad A, Teague JE, et al: Survival of

tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and

metabolism. Nature. 543:252–256. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Donati G, Nicoli P, Verrecchia A,

Vallelonga V, Croci O, Rodighiero S, Audano M, Cassina L, Ghsein A,

Binelli G, et al: Oxidative stress enhances the therapeutic action

of a respiratory inhibitor in MYC-driven lymphoma. EMBO Mol Med.

15:e169102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Purhonen J, Klefström J and Kallijärvi J:

MYC-an emerging player in mitochondrial diseases. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 11:12576512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Kawalekar OU, O'Connor RS, Fraietta JA,

Guo L, McGettigan SE, Posey AD Jr, Patel PR, Guedan S, Scholler J,

Keith B, et al: Distinct signaling of coreceptors regulates

specific metabolism pathways and impacts memory development in CAR

T cells. Immunity. 44:7122016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Leber A, Hontecillas R, Zoccoli-Rodriguez

V, Bienert C, Chauhan J and Bassaganya-Riera J: Activation of NLRX1

by NX-13 alleviates inflammatory bowel disease through

immunometabolic mechanisms in CD4(+) T cells. J Immunol.

203:3407–3415. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Verstockt B, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet

L, Mosig R, Feagan BG, Colombel JF, Siegmund B, Rieder F, Schreiber

S, Yarur A, et al: The safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and

clinical efficacy of the NLRX1 agonist NX-13 in active ulcerative

colitis: Results of a phase 1b study. J Crohns Colitis. 18:762–772.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

89

|

Leone RD, Zhao L, Englert JM, Sun IM, Oh

MH, Sun IH, Arwood ML, Bettencourt IA, Patel CH, Wen J, et al:

Glutamine blockade induces divergent metabolic programs to overcome

tumor immune evasion. Science. 366:1013–1021. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Praharaj M, Shen F, Lee AJ, Zhao L,

Nirschl TR, Theodros D, Singh AK, Wang X, Adusei KM, Lombardo KA,

et al: Metabolic reprogramming of tumor-associated macrophages

using glutamine antagonist JHU083 drives tumor immunity in

myeloid-rich prostate and bladder cancers. Cancer Immunol Res.

12:854–875. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Geiger R, Rieckmann JC, Wolf T, Basso C,

Feng Y, Fuhrer T, Kogadeeva M, Picotti P, Meissner F, Mann M, et

al: L-arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival

and anti-tumor activity. Cell. 167:829–842.e13. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Wiel C, Le Gal K, Ibrahim MX, Jahangir CA,

Kashif M, Yao H, Ziegler DV, Xu X, Ghosh T, Mondal T, et al: BACH1

stabilization by antioxidants stimulates lung cancer metastasis.

Cell. 178:330–345.e22. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Guo D, Tong Y, Jiang X, Meng Y, Jiang H,

Du L, Wu Q, Li S, Luo S, Li M, et al: Aerobic glycolysis promotes

tumor immune evasion by hexokinase2-mediated phosphorylation of

IκBα. Cell Metab. 34:1312–1324.e6. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

van der Kolk BW, Muniandy M, Kaminska D,

Alvarez M, Ko A, Miao Z, Valsesia A, Langin D, Vaittinen M,

Pääkkönen M, et al: Differential mitochondrial gene expression in

adipose tissue following weight loss induced by diet or bariatric

surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 106:1312–1324. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Xia W, Veeragandham P, Cao Y, Xu Y, Rhyne

TE, Qian J, Hung CW, Zhao P, Jones Y, Gao H, et al: Obesity causes

mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in white adipocytes due

to RalA activation. Nat Metab. 6:273–289. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Wu C, Liu Y, Liu W, Zou T, Lu S, Zhu C, He

L, Chen J, Fang L, Zou L, et al: NNMT-DNMT1 axis is essential for

maintaining cancer cell sensitivity to oxidative phosphorylation

inhibition. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e22026422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

He P, Feng J, Xia X, Sun Y, He J, Guan T,

Peng Y, Zhang X, Liu M, Pang X and Chen Y: Discovery of a potent

and oral available complex I OXPHOS inhibitor that abrogates tumor

growth and circumvents MEKi resistance. J Med Chem. 66:6047–6069.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Wu MM, Wang QM, Huang BY, Mai CT, Wang CL,

Wang TT and Zhang XJ: Dioscin ameliorates murine ulcerative colitis

by regulating macrophage polarization. Pharmacol Res.

172:1057962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Wu L, Zhang X, Zheng L, Zhao H, Yan G,

Zhang Q, Zhou Y, Lei J, Zhang J, Wang J, et al: RIPK3 orchestrates

fatty acid metabolism in tumor-associated macrophages and

hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Immunol Res. 8:710–721. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Shriver LP and Manchester M: Inhibition of

fatty acid metabolism ameliorates disease activity in an animal

model of multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep. 1:792011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

101

|

Cao D, Khan Z, Li X, Saito S, Bernstein

EA, Victor AR, Ahmed F, Hoshi AO, Veiras LC, Shibata T, et al:

Macrophage angiotensin-converting enzyme reduces atherosclerosis by

increasing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α and

fundamentally changing lipid metabolism. Cardiovasc Res.

119:1825–1841. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Nomura M, Liu J, Yu ZX, Yamazaki T, Yan Y,

Kawagishi H, Rovira II, Liu C, Wolfgang MJ, Mukouyama YS and Finkel

T: Macrophage fatty acid oxidation inhibits atherosclerosis

progression. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 127:270–276. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Hinshaw DC, Hanna A, Lama-Sherpa T, Metge

B, Kammerud SC, Benavides GA, Kumar A, Alsheikh HA, Mota M, Chen D,

et al: Hedgehog signaling regulates metabolism and polarization of

mammary tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Res. 81:5425–5437.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Liu PS, Chen YT, Li X, Hsueh PC, Tzeng SF,

Chen H, Shi PZ, Xie X, Parik S, Planque M, et al: CD40 signal

rewires fatty acid and glutamine metabolism for stimulating

macrophage anti-tumorigenic functions. Nat Immunol. 24:452–462.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

An L, Lu M, Xu W, Chen H, Feng L, Xie T,

Shan J, Wang S and Lin L: Qingfei oral liquid alleviates

RSV-induced lung inflammation by promoting fatty-acid-dependent

M1/M2 macrophage polarization via the Akt signaling pathway. J

Ethnopharmacol. 298:1156372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Bougarne N, Weyers B, Desmet SJ, Deckers

J, Ray DW, Staels B and De Bosscher K: Molecular actions of PPARα

in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Endocr Rev. 39:760–802. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Wang D, Liu B, Tao W, Hao Z and Liu M:

Fibrates for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and

stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:Cd0095802015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Lim SA, Wei J, Nguyen TM, Shi H, Su W,

Palacios G, Dhungana Y, Chapman NM, Long L, Saravia J, et al: Lipid

signalling enforces functional specialization of T(reg) cells in

tumours. Nature. 591:306–311. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Fu Y, Zou T, Shen X, Nelson PJ, Li J, Wu

C, Yang J, Zheng Y, Bruns C, Zhao Y, et al: Lipid metabolism in

cancer progression and therapeutic strategies. MedComm. 2:27–59.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Altman BJ, Stine ZE and Dang CV: From

Krebs to clinic: Glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat Rev

Cancer. 16:619–34. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Cluntun AA, Lukey MJ, Cerione RA and

Locasale JW: Glutamine metabolism in cancer: Understanding the

heterogeneity. Trends Cancer. 3:169–180. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Hensley CT, Wasti AT and DeBerardinis RJ:

Glutamine and cancer: Cell biology, physiology, and clinical

opportunities. J Clin Invest. 123:3678–3684. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagés M,

Pestell RG, Sotgia F and Lisanti MP: Cancer metabolism: A

therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:1132017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Oh MH, Sun IH, Zhao L, Leone RD, Sun IM,

Xu W, Collins SL, Tam AJ, Blosser RL, Patel CH, et al: Targeting

glutamine metabolism enhances tumor-specific immunity by modulating

suppressive myeloid cells. J Clin Invest. 130:3865–3884. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Pillai R, LeBoeuf SE, Hao Y, New C, Blum

JLE, Rashidfarrokhi A, Huang SM, Bahamon C, Wu WL, Karadal-Ferrena

B, et al: Glutamine antagonist DRP-104 suppresses tumor growth and

enhances response to checkpoint blockade in KEAP1 mutant lung

cancer. Sci Adv. 10:eadm98592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Liu N, Chen L, Yan M, Tao Q, Wu J, Chen J,

Chen X, Zhang W and Peng C: Eubacterium rectale improves the

efficacy of anti-PD1 immunotherapy in melanoma via