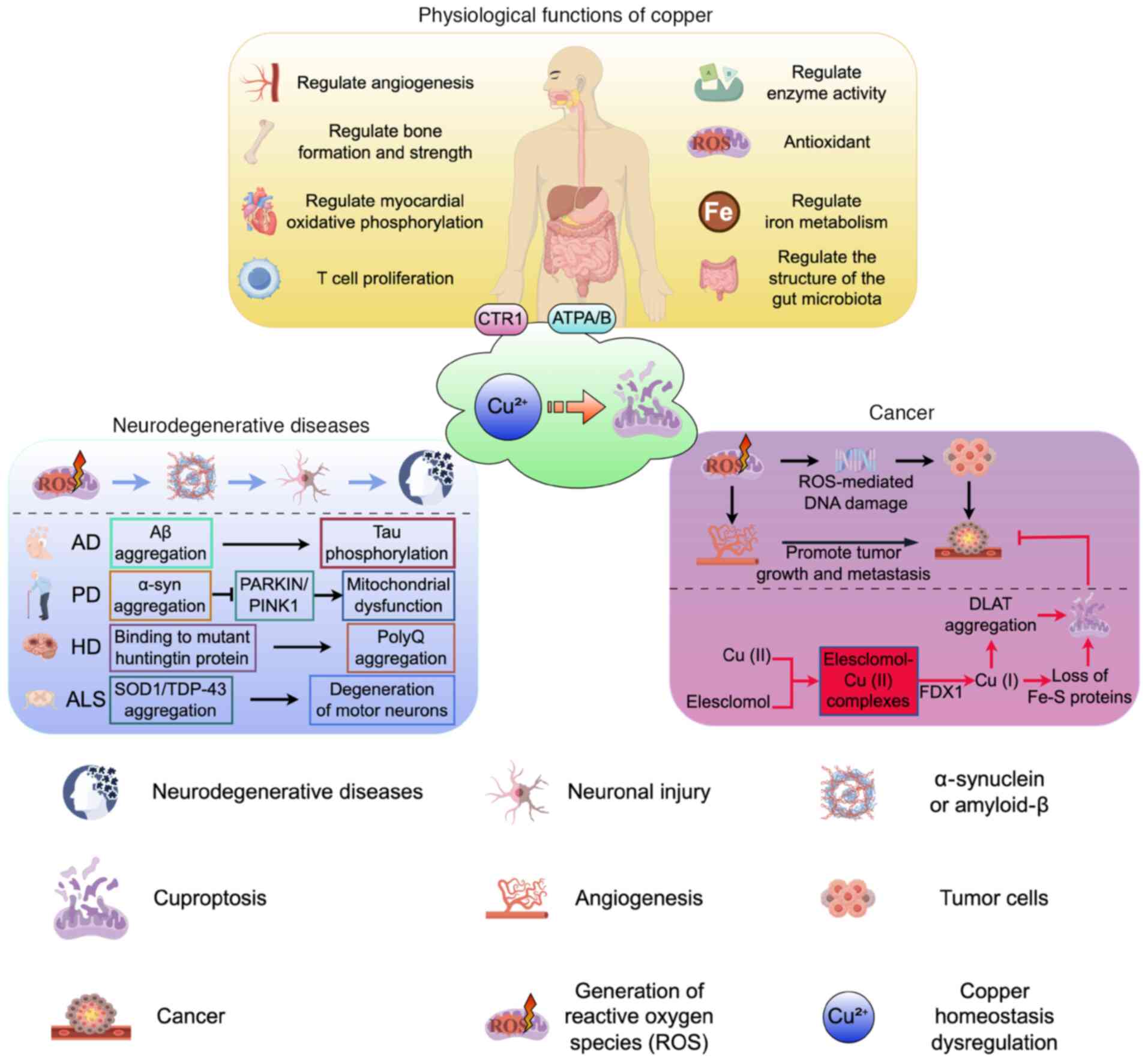

Copper is an essential trace element and the

recommended daily intake for adults ranges from 0.8 to 2.4 mg per

day (1). Copper is required for

almost all the functions of tissues and organs, in particular for

oxidative phosphorylation in the heart and brain, scavenging of

free radicals (2), angiogenesis

(3), bone formation and

regeneration (4,5), modulation of bone strength

(6,7) and the regulation of rest-activity

cycles (8) (Fig. 1). Copper also participates in the

synthesis of copper-dependent enzymes, including superoxide

dismutase (SOD) (9), cytochrome

c oxidase (10), tyrosinase

(11), lysyl oxidase and

dopamine (DA) β-hydroxylase (12,13). Copper enzymes play a crucial role

in key physiological processes such as energy metabolism,

antioxidant defense and neurotransmitter synthesis. Their

dysfunction directly leads to a variety of genetic and acquired

diseases (14,15) (Table I).

Copper homeostasis regulation can be classified into

three processes: Absorption, utilization/storage and excretion.

Disruptions in copper homeostasis can result in impaired

physiological functions and the onset of various related diseases

(Fig. 1). In response to these

challenges, researchers have developed a range of copper-targeted

therapeutic strategies designed to manage such conditions. These

interventions specifically address pathological states caused by

copper deficiency, copper overload or disturbances in copper

metabolism, and they exert their effects by modulating copper

concentration, distribution or biological activity within the body.

These therapeutic approaches show significant potential in the

treatment of hereditary copper metabolism disorders,

neurodegenerative diseases and cancers. This article provides a

comprehensive and timely review of the dual role of copper in human

biology, with a particular emphasis on its implications for health,

neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. This review provides a

theoretical foundation and offers diverse perspectives for the

development of treatments for related diseases.

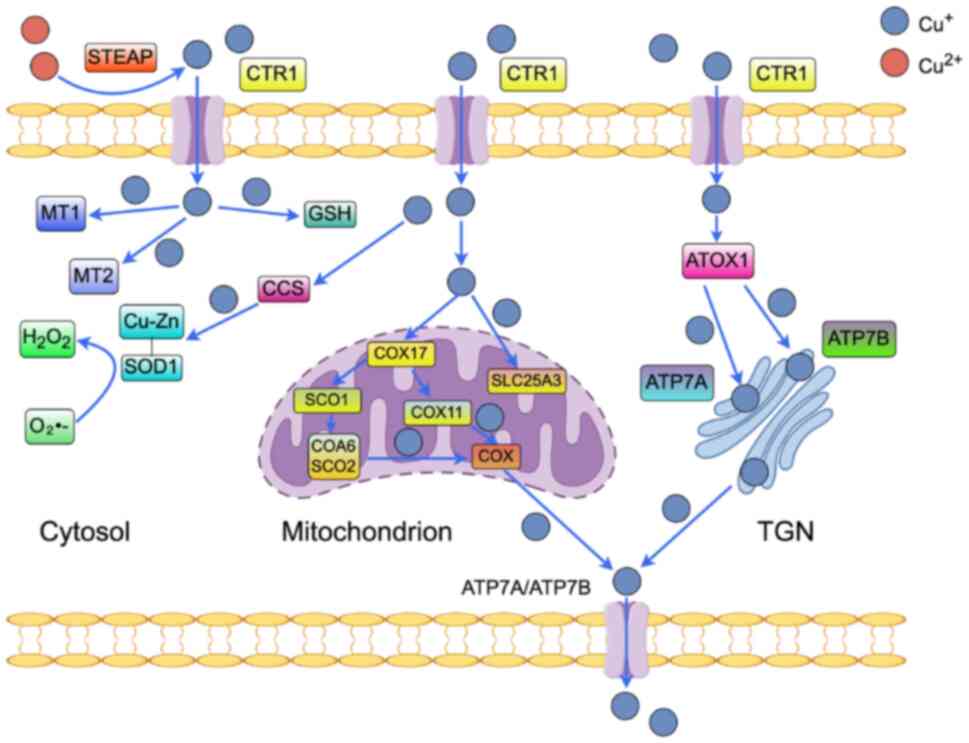

Copper absorption primarily occurs in the small

intestine, particularly in the duodenum, which serves as the key

site for this process (16). In

dietary sources, copper is predominantly present as Cu(II). The

six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate proteins

(17), localized on the apical

membrane of small intestinal epithelial cells, possess reductase

activity that facilitates the reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I).

Subsequently, Cu(I) is taken up by the copper transporter 1 (CTR1),

also known as solute carrier family 31 member 1 (SLC31A1) (18,19), which is expressed on the

intestinal epithelial membrane. Once Cu(I) enters the enterocytes,

it is transported into the bloodstream through vesicular transport

mediated by ATPase copper transporting α (ATP7A) (Fig. 2). In the bloodstream, copper

binds to various proteins, including human serum albumin (20), ceruloplasmin (21), albumin, α-2-macroglobulin

(22), histidine and

transcupreins. These complexes either support copper's

physiological functions through the systemic circulation or enable

its uptake and storage by the liver (23-25).

The high-affinity copper transporter protein CTR1

facilitates the transfer of extracellular Cu(I) into the cell

(26). In mice,

intestinal-specific knockout of CTR1 resulted in severe growth and

developmental defects, leading to embryonic lethality by

mid-gestation. These findings indicate that CTR1-mediated copper

uptake is essential for mammalian copper homeostasis and embryonic

development (27). Additionally,

CTR1 gene expression is regulated by changes in specificity protein

1 (Sp1) activity and extracellular copper concentrations (28,29). Specifically, the human

high-affinity copper transporter hCTR1 is transcriptionally

upregulated during copper deficiency and downregulated under

copper-replete conditions. Elevated hCTR1 levels also suppress its

own expression. Notably, Sp1 modulates hCTR1 expression under

copper stress (30).

Once inside the cell, copper rapidly binds to

co-chaperone proteins such as antioxidant 1 copper chaperone

(Atox1), copper chaperone for SOD (CCS) and cytochrome c oxidase

copper chaperone COX17 (COX17). This interaction is essential for

the safe and targeted delivery of copper to its specific functional

sites, thereby supporting and maintaining critical cellular

processes (29).

Atox1 functions as a key cytoplasmic copper

chaperone, directly binding Cu(I) and mediating its delivery to the

copper-transporting ATPases ATP7A and ATP7B located on the Golgi

membrane (Fig. 2). This process

is essential for the systemic distribution of copper ions and the

maintenance of copper homeostasis (31,32). Importantly, research by Lutsenko

has revealed that Atox1 promotes the synthesis of ceruloplasmin, a

protein critical for iron metabolism, as well as tyrosinases

(33).

The CCS is localized in compartments such as the

cytoplasm and the mitochondrial intermembrane space (34), binds copper and activates SOD1

(Cu/Zn SOD), a copper/zinc-dependent enzyme. In eukaryotes, SOD is

expressed as SOD1 in the cytoplasm and extracellularly, and as

Mn-SOD2 in the mitochondria. The SOD enzymes catalyze the

disproportionation of superoxide (O2•-) to

produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and the

balance between copper and reactive oxygen species (ROS) is

physiologically crucial (35,36). Furthermore, CCS expression is

strongly negatively correlated with copper levels, serving as a

feedback regulatory mechanism to prevent excessive activation of

SOD1 under conditions of copper overload (37).

The COX is associated with oxidative phosphorylation

in mitochondria, and its function is mainly mediated by five

proteins: COX17, synthesis of cytochrome C oxidase 1 (SCO1), SCO2,

cytochrome c oxidase assembly factor 6 (COA6) and COX11, each of

which is essential. COX17 transfers copper ions from the cytoplasm

to the mitochondrial intermembrane space (38), and then, through the formation of

a disulfide bond, transfers them to SCO1 (39). Copper is transported primarily

through the action of COA6 with SCO2 in the maintenance of redox

homeostasis within mitochondria or through COX11 (40).

In addition to these chaperones, copper can be

transported into the mitochondria by the mitochondrial phosphate

transporter SLC25A3 (41).

Another key component is the intracellular copper storage proteins

metallothionein 1 (MT1) and MT2, which have a high affinity for

copper (40), while copper, as a

catalyst for the Fenton reaction, is also capable of binding to

glutathione (GSH) (42). These

proteins are essential for the effective utilization of copper and

the synthesis of key copper enzymes, including SOD, cytochrome c

oxidase, tyrosinase, lysyl oxidase, DA β-hydroxylase, ATPase

copper-transporting α (ATP7A) and ATP7B to maintain normal cellular

functions (40).

The regulation of copper homeostasis is

fundamentally dependent on the copper-transporting ATPases ATP7A

and ATP7B. In response to elevated intracellular copper [Cu(I)]

levels, ATP7A and ATP7B translocate from the trans-Golgi network

(TGN) to vesicles that subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane,

thereby facilitating the efflux of Cu(I) from the cell. Conversely,

when intracellular Cu(I) levels are reduced, these ATPases are

retained within the TGN, where they actively transport Cu(I) into

the TGN lumen to support the maturation of copper-dependent

proteins. Once physiological Cu(I) levels are restored, ATP7A and

ATP7B are recycled back to the TGN, re-establishing their basal

localization and maintaining responsiveness to fluctuations in

cellular copper concentrations (43). ATP7A can mediate copper transport

across polarized cellular barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier

(BBB) and the blood-placenta barrier, thereby enabling copper

export and ensuring that the fetus receives adequate copper during

development. ATP7B, predominantly expressed in the liver, becomes

active under conditions of elevated hepatic copper concentrations

(33). In hepatic cells, ATP7B

plays a crucial role in the regulation of copper homeostasis by

mediating the transport of excess copper into bile, leading to its

excretion via feces, a process essential for maintaining the

systemic copper balance (44).

This protein facilitates copper elimination via bile secretion or

through binding to soluble proteins for delivery to specific

tissues and organs (45).

Copper deficiency is associated with impaired immune

function and reduced T-cell proliferation, which leads to decreased

production of interleukin-2 (IL-2). The capacity of immune cells to

generate superoxide anions and eliminate bacteria is diminished in

mild copper deficiency, and the number of neutrophils in the

peripheral blood is reduced in severe copper deficiency (46,47). Menkes syndrome (MD) is an

X-linked recessive disorder caused by mutations in ATP7A and is

characterized by systemic copper deficiency, primarily due to

impaired intestinal copper uptake, progressive neurodegeneration,

connective tissue disorders, and brittle, kinky hair (48). Infants with severe MD often do

not survive beyond the third year of life, with neurological

deficits, matted hair, developmental delays, genitourinary

abnormalities, skin abnormalities, vascular abnormalities, skeletal

abnormalities and spasticity of the limbs that transform into

muscle weakness of the limbs along with other abnormal signs. Most

patients die within the third year of life from cerebral hemorrhage

due to vascular fragility or infection-related complications

(49). This indicates that

copper plays a crucial role in infant development: Copper imbalance

driven by ATP7A mutations leads to extensive multi-organ

dysfunction in MD, which is manifested as multi-system

abnormalities and fatal outcomes in infants. Another disorder

caused by mutations in ATP7A leading to copper deficiency is

occipital horn syndrome (OHS), which is a phenotype of MD but with

milder symptoms than those of MD (50). Bone exostoses, radial head

dislocations, keloid-like skin lesions and dental abnormalities are

specific to OHS, which can also present with developmental delay

and mild neurological symptoms (14). An early study indicated that the

ATP7A transcript lacking exon 10 encodes a partially functional

protein, and this residual function is associated with a milder

form of occipital horn syndrome (OHS), which is caused by mutations

at the ATP7A splicing site. Unlike the loss-of-function mutations

observed in classical Menkes disease (MD), OHS is characterized by

relatively mild clinical symptoms (50). In 2022, Batzios et al

(51) identified a genetic

disorder of brain copper metabolism caused by CTR1 deficiency,

which presents with hypotonia, global developmental delay, seizures

and rapid cerebral atrophy. Brain CTR1, ATP7A and ATP7B protein

levels may be affected by factors other than gene expression, such

as the rate of copper transport mediated by these proteins. The key

to treating MD is supplementation with additional copper (52-54), which is not replenished orally

because of impaired intestinal absorption caused by ATP7A

deficiency. The most widely used treatment is parenteral or

subcutaneous supplementation with copper histidine (55,56).

Copper overload disrupts the expression and function

of antioxidant enzymes and induces oxidative stress, while

oxidative stress and increased ROS levels are thought to be the

main cause of Cu-induced cytotoxicity (57,58). When copper is overloaded,

hydrogen peroxide can be converted into highly reactive hydroxyl

radicals, which can cause DNA and membrane damage (59,60). Excessive copper intake has also

been linked to alterations in the gut microbiota, which in turn can

lead to a range of conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome

(61). Studies have shown that

increased intracellular Cu activates autophagy through unc-51 like

autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1)/ULK2 signaling, thereby

promoting cancer cell growth and survival (62,63). Wilson disease (WD) is an

autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in ATP7B that is

primarily due to ATP7B mutations that result in impaired copper

excretion from hepatocytes into bile, a significant increase in

copper levels in hepatocytes and subsequent liver injury; excess

copper is released into the circulation, where it is deposited in

areas such as the brain or the eyeballs, causing damage. WD is

clinically heterogeneous and may present with neurological

dysfunction, acute liver failure and the presence of hemolysis,

rhabdomyolysis, renal tubular injury, leukopenia and

thrombocytopenia (64-66). Long-term management of WD

includes chelating agents such as tetrathiomolybdate (TM) (67), trientine or d-penicillamine

(68-70), as well as zinc salts to reduce

copper absorption (40,71,72).

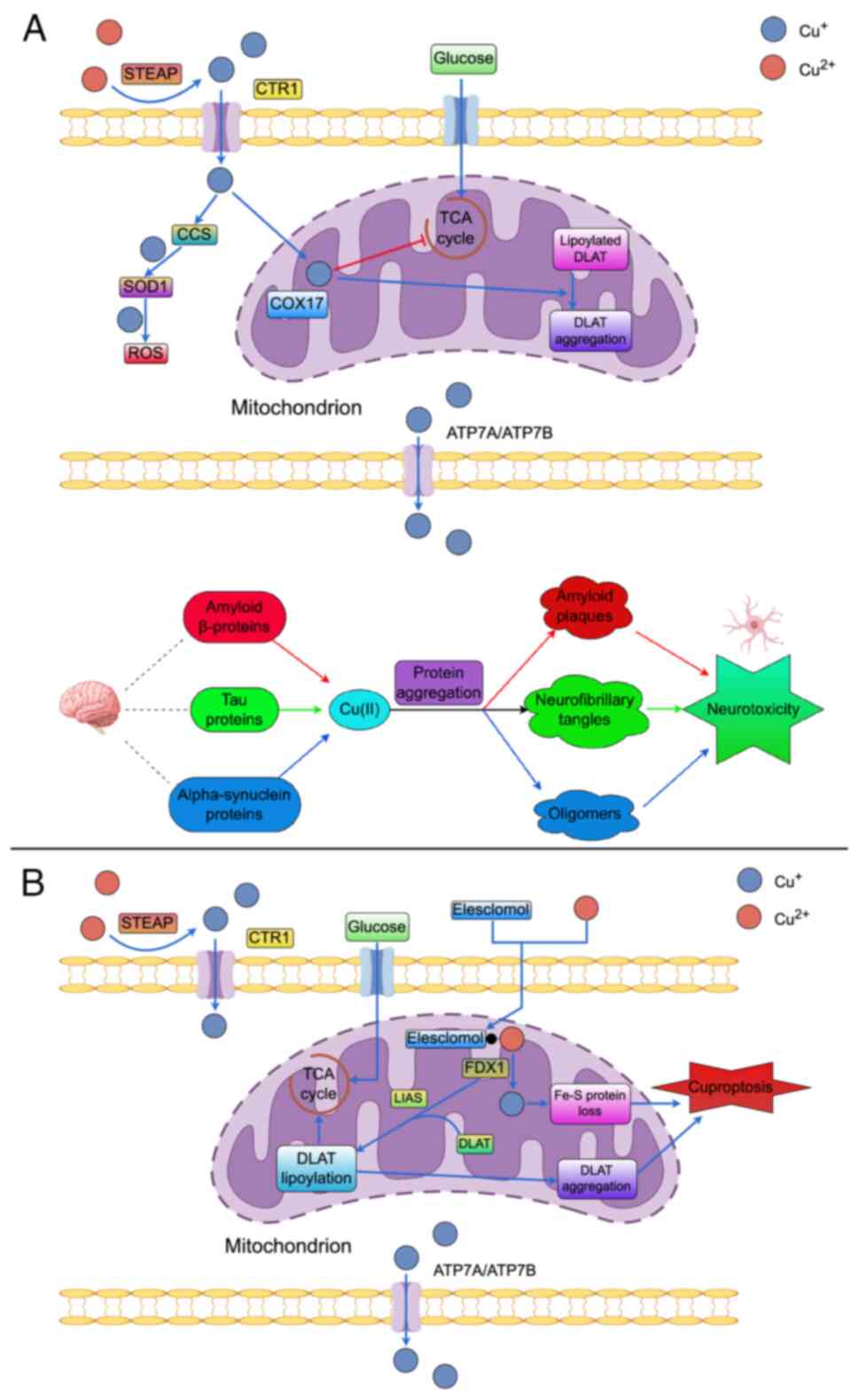

AD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by

the presence of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and tau protein tangles in

the brain (Fig. 3A). Initially,

these pathological features were regarded as the primary pathogenic

drivers of AD, prompting a focus on therapeutic strategies aimed at

reducing the accumulation of Aβ or tau proteins (73,74). However, drug development

targeting these proteins has faced substantial challenges: >30

Phase III clinical trials have shown that Aβ inhibitors do not

significantly improve cognitive function in patients with AD, and

some interventions have even led to adverse effects following

plaque removal (75-77). This research and development

predicament not only highlights the limitations of traditional

target therapy but also prompts researchers to re-examine and

explore the pathogenesis of AD.

While the precise molecular mechanisms underlying AD

remain elusive, accumulating evidence suggests that dysregulation

of brain metal ions, particularly copper and zinc, may contribute

to the hallmark Aβ neuropathology associated with the disease

(78,79). Transition metals such as copper,

iron and zinc are essential for normal physiological functions;

however, copper has been specifically implicated in promoting Aβ

aggregation and the formation of harmful species. Notably,

individuals with AD exhibit reduced copper levels in brain tissue,

yet elevated concentrations in serum and age-related pigments

(80-82). Copper's role in promoting Aβ

precipitation and generating redox-active species warrants further

investigation. Serum levels of both free and total copper are

significantly elevated in individuals with AD, and increased copper

deposition is observed in the age-related pigments of these

patients (82,83). Following the observation that

copper promotes Aβ precipitation under acidic conditions, the

interactions between copper and Aβ have been increasingly explored

in detail (84-86). Critically, copper can form

complexes with Aβ that drive redox reactions, involving lipids to

induce oxidative stress, ultimately leading to cellular apoptosis

and contributing to cognitive decline (87-89).

HD is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder

characterized by neuropsychiatric symptoms, movement disorders

(most commonly choreoathetosis) and progressive cognitive

impairment. HD is currently treated symptomatically and scientists

have struggled to identify effective disease-modifying therapies.

Metal homeostasis is disrupted during the progression of HD,

although its exact role in the pathogenesis of the disease remains

elusive. Meanwhile, some researchers have observed tissue

abnormalities and deposition of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) in

HD-affected brain regions, which may contribute to disease

initiation and progression through mechanisms including

mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and BBB dysfunction

(110). It has been reported

that copper-regulated genes are upregulated in HD and that copper

binds to the N-terminal fragment of huntingtin, supporting the

involvement of aberrant copper metabolism in HD. Copper has been

shown to accelerate fibril formation of the N-terminal fragment of

huntingtin in vitro via the expanded polyglutamine (polyQ)

stretch (httExon1). Copper has also been found to enhance polyQ

aggregation and toxicity in mammalian cells expressing httExon1.

Studies in a yeast model of HD demonstrated that overexpression of

several genes involved in copper metabolism reduced polyQ-mediated

toxicity. The MT3 gene belongs to the metallothionein family and is

mainly expressed in the central nervous system. It regulates zinc

and copper homeostasis and acts as a neuronal growth inhibitory

factor (111). Overexpression

of MT3 in mammalian cells significantly reduced polyQ aggregation

and toxicity (112). Animal

studies have also shown that copper chelators modulate the early

events of Htt misfolding and reduce neurotoxicity in the

Drosophila HD model (90,113,114). Despite the promising

therapeutic potential of MT3 in HD, its clinical translation

remains limited by technical and mechanistic challenges.

PD is an age-related neurodegenerative disease, and

the role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the

progression of PD has been widely recognized in relation to the

selective loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta

(SNpc) of the nigrostriatal DA pathway and the reduction of DA

levels in the striatum (115).

The normal substantia nigra contains twice as much copper as other

brain regions, suggesting that copper plays an important role in

this brain area (116). Autopsy

brain samples from patients with PD show increased iron and

decreased copper in the substantia nigra and basal ganglia

(117,118).

At the cellular level, PD is associated with the

overproduction of ROS. While copper may contribute to intracellular

oxidative stress by participating in the Fenton and Haber-Weiss

reactions or by interfering with iron homeostasis, either directly

or indirectly through the formation of hydroxyl radicals,

experimental evidence linking copper deficiency and the formation

of SOD1 aggregates to the progression of PD is also discussed in

terms of its therapeutic implications (119,120). Copper causes a decrease in SOD1

activity by interfering with SOD1 synthesis, leading to a loss of

cellular protection against neuronal oxidative damage (121,122).

It is important to note that mitochondrial

dysfunction represents a central mechanism driving oxidative stress

in PD. Mutations in the phosphatase and tensin homolog-induced

kinase 1 (PINK1) and PARKIN RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase (PARKIN) genes

are associated with familial forms of the disease. Parkin and PINK1

play critical roles in mitochondrial quality control, particularly

in the process of mitophagy, and are essential for the survival of

dopaminergic neurons. Under normal physiological conditions, PINK1

accumulates on damaged mitochondria by sensing changes in the

mitochondrial membrane potential. This accumulation promotes Parkin

recruitment and activates its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity,

resulting in the ubiquitination of damaged mitochondria and the

initiation of autophagic degradation. This pathway limits the

release of ROS and reduces mitochondrial toxicity (123,124).

Dysregulation of copper homeostasis interferes with

the PARKIN/PINK1 pathway through multi-layered mechanisms (125). Excessive copper downregulates

the transcription of PINK1 and PARKIN in cellular models, although

the exact regulatory mechanism (e.g., involvement of NF-κB) remains

to be fully elucidated. Importantly, copper can also impair the

activity of PINK1 and PARKIN proteins by inducing conformational

changes, specifically through binding to the kinase domain of PINK1

and the RING finger domain of PARKIN. Notably, the role of copper

in regulating PINK1/PARKIN is context-dependent: It inhibits

PINK1/PARKIN function under pathological conditions (e.g., copper

excess), while promoting their transcriptional regulation and

autophagic processes under physiological conditions (125,126). It further impairs PINK1 kinase

activity and Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity by coordinating

with cysteine/histidine residues within their respective functional

domains, the kinase domain of PINK1 and the RING finger domain of

Parkin, thereby inducing conformational changes (125). These disruptions prevent Parkin

recruitment to damaged mitochondria, inhibit mitochondrial

substrate ubiquitination and perturb the PARKIN/PINK1-regulated

balance of mitochondrial dynamics, ultimately leading to the

accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and exacerbated

oxidative stress. This cascade reflects the pathological shift in

copper's regulatory role in mitophagy under homeostatic imbalance,

which contrasts with its physiological role in promoting

mitophagy-mediated tissue regeneration (126). However, the underlying

mechanisms remain incompletely understood and require further

investigation. In addition, exposure to elevated copper levels has

been shown to accelerate the formation of toxic α-synuclein

aggregates, a key pathological contributor to neuronal loss in PD

(127).

Second, microglia-mediated neuroinflammation is an

important component of the pathogenesis of PD. In animal studies,

researchers have observed inflammatory changes in mouse brain

tissue, including activation of microglia, loss of dopaminergic

neurons and aggregation of α-syn in the substantia nigra. Copper

has been shown to activate BV2 cells via the NF-κB pathway and to

increase ROS levels in BV2 cells (128,129). Sustained copper accumulation in

BV2 cells resulted in a decrease in mitochondrial membrane

potential, a reduction in Parkin and PINK1 expression, an increase

in P62 expression and light chain 3BII/I ratio, and upregulation of

NLR family pyrin domain containing 3/caspase-1/gasdermin D axis

proteins (130,131).

Research on the treatment of PD with copper-based

compounds, such as 8-hydroxyquinoline-2-carboxaldehyde

isonicotinoylhydrazine, a moderate metal-binding compound that

binds to copper ions, has been shown to efficiently compete with

ortho-nucleosides for Cu(I) and Cu(II) binding and to inhibit

protein aggregation in vitro and in cells (132). Copper(II)

diacetylbis(4-methylthiosemicarbazone), also known as CuII(atsm),

is an orally available, biologically active BBB-penetrant compound

that is widely used to selectively label hypoxic tissues in

cellular imaging experiments (133). It has been shown to accumulate

in the striatum of patients with PD at levels that positively

correlate with disease stage (134). Furthermore, CuII(atsm) has

demonstrated therapeutic potential in rescuing dopaminergic neuron

loss and alleviating motor dysfunction in PD models (119,135). In addition, CuII(atsm)

supplementation has been shown to significantly reduce the

misfolding and deposition of wild-type SOD1 protein associated with

PD in a novel mouse model, enhance DA neuron survival and improve

motor function, suggesting its potential as a novel therapeutic

strategy for PD treatment (136). However, further research and

clinical trials are necessary to validate these findings.

ALS is a progressive neurodegenerative disease of

the motor neurons that leads to the worsening of casual muscle

weakness until death from respiratory failure ~3 years after onset

(137). Numerous symptoms of

ALS are associated with signs of copper deficiency, leading to

defects in the vasculature, antioxidant system and mitochondrial

oxidative respiration, but there are also signs of copper toxicity,

such as increased ROS generation and protein aggregation (138).

About 2% of ALS cases have mutations in SOD1, which

neutralizes harmful reactive oxygen superoxide (139). Familial ALS is at times linked

to the gene encoding Cu/Zn-binding SOD. Mutations in ALS are

thought to result in functional enhancement of dismutase activity

(140). Mutations in human SOD1

are found in ~20% of patients with familial ALS. They are

characterized by a conformational dysfunction of the electrostatic

and zinc-binding elements (mutant SOD1-mediated pathogenesis of

ALS). A study using transgenic mice expressing wild-type or mutant

human SOD confirmed that dominant mutations in SOD and the

acquisition of function are important factors in the pathogenesis

of familial ALS (141).

Previous studies have shown that CuII(atsm) in ALS

can restore SOD1 dysfunction caused by copper deficiency (135). Therefore, the use of Cu as a

new target for treating familial progressive ALS becomes possible.

However, further studies are necessary to validate these

findings.

Overall, for copper-related diseases, including both

the copper metabolism disorders discussed earlier and the

neurodegenerative conditions addressed in this chapter, therapeutic

strategies targeting copper homeostasis have been developed, with

drug selection guided by the underlying disease etiology

(deficiency, overload or imbalance). This establishes a clear

pathophysiological and etiological foundation for clinical

intervention (Table II).

According to the most recent estimates provided by

the International Agency for Research on Cancer, ~20 million new

cancer cases, including non-melanoma skin cancers, and 9.7 million

cancer-related deaths were reported globally in 2022. Lung cancer

emerged as the most frequently diagnosed cancer, accounting for

nearly 2.5 million new cases, representing approximately one in

eight cancer diagnoses worldwide (12.4% of all cancers). This was

followed by female breast cancer (11.6%), colorectal cancer (9.6%),

prostate cancer (7.3%) and gastric cancer (4.9%). Furthermore, lung

cancer was identified as the leading cause of cancer-related

mortality, with an estimated 1.8 million deaths (18.7% of total

cancer deaths), followed by colorectal cancer (9.3%), liver cancer

(7.8%), female breast cancer (6.9%) and stomach cancer (6.8%)

(142).

Abnormal accumulation or deficiency of trace

elements plays a significant role in cancer pathogenesis and

progression, with dysregulation of copper metabolism being

particularly notable (143,144). Research suggests that there is

an increased demand for copper during tumor proliferation and

metastasis (40,145). Elevated serum copper levels

have been reported in various cancers, including breast cancer

(146,147), lung cancer (148) and prostate cancer (149). By contrast, reduced serum

copper levels have been observed specifically in hepatocellular

carcinoma and endometrial cancer (150,151), although the underlying

mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated.

Copper can promote tumorigenesis by promoting

oxidative stress that damages DNA and related molecular structures

(152), and contributes to

tumor development by promoting angiogenesis, metastasis and cell

proliferation through multiple mechanisms: Increased intracellular

copper enhances oxidative stress caused by the formation of ROS,

leading to elevated intracellular ROS levels (153), DNA damage and activation of

oncogenes (59), whereas reduced

intracellular copper results in decreased SOD1 activity, nearly

complete loss of resistance to oxidative damage and impaired

maintenance of normal cellular life activities (121).

Copper has also been found to directly bind

ULK1/ULK2 and activate autophagy by Tsang et al (62). Cellular autophagy is inhibited

when CTR1 is deficient, which can suppress oncogene-induced cancer

cell proliferation; autophagosomes are reduced and tumor size is

significantly decreased in mice in which CTR1 is knocked out using

single-guide RNA (62). Copper

promotes cancer by stimulating the MAPK pathway (166). Copper binds to MAPK kinase

(MEK)1/2 and activates downstream ERK1/2 phosphorylation, thereby

promoting tumor proliferation. MEK1/2 activity was inhibited in

BRAFV600E-positive cancer cells, and proliferation was

significantly suppressed after TM treatment, suggesting that MEK1/2

activity is highly correlated with copper levels (167,168). The epidermal growth factor

receptor (EGFR), as a key upstream regulator of the MAPK pathway,

is overexpressed or mutated in various cancers (including ovarian

cancer), driving cell proliferation, survival and metastasis.

Copper binds to and inhibits protein tyrosine phosphatase N2

(PTPN2), leading to the loss of its phosphatase activity. This

inhibition relieves the suppression of EGFR dephosphorylation,

thereby activating EGFR signaling. In turn, activated EGFR

suppresses the transcription of CTR1 via the cAMP responsive

element binding protein (CREB) signaling pathway, forming a

closed-loop regulatory circuit: 'copper-PTPN2-EGFR-CREB-CTR1'.

Fluctuations in intracellular copper levels can thus modulate EGFR

activity through this feedback axis, highlighting a mechanistic

link between copper homeostasis and EGFR signaling (169). Research by Jakhmola et

al (147) revealed the

significant role of EGFR in ovarian cancer through computational

simulation methods and pointed out that the DADETL segment

(including the self-phosphorylated tyrosine 992) is the key region

leading to receptor overexpression. This is similar to the

copper-mediated activation mechanism of the MAPK pathway,

suggesting that copper may indirectly affect tumor development by

regulating EGFR activity or downstream signal transduction. Future

studies are necessary to deeply explore the direct association

between copper and the EGFR pathway, providing new ideas for the

combined application of copper-targeted therapy and EGFR inhibitors

(147).

Copper also mediates the activation of programmed

cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in

cancer cells, enabling immune evasion. When copper chelators are

used, phosphorylation of STAT3 and EGFR is inhibited, promoting

ubiquitination-mediated degradation of PD-L1, and slowing tumor

growth by increasing the number of CD8+ T cells and NK

cells (170,171).

It has been shown that the metabolic profile of

cancer cells differs from that of normal cells in that cancer cells

maintain a higher metabolic rate to support a higher proliferation

rate and to resist cell death signals (172). Cell death involves proteins and

lipids and includes apoptosis (173,174), necroptosis (175), pyroptosis (176) and ferroptosis (177,178). The demand for copper is high

during cell growth and abnormal accumulation of excess copper

within the cell leads to cellular dysfunction and ultimately cell

death (179,180). Mechanisms of copper-induced

toxicity include induction of apoptosis (181-183), caspase-independent cell death

pathways (184-186), induction of ROS or inhibition

of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (129,187-189).

However, the mechanism underlying copper-induced

cell death remained unclear until a study published in Science in

2022 by Tsvetkov et al (190) proposed the concept of

cuproptosis - a novel form of copper-induced cell death that is

distinct from other known forms of cell death (Fig. 3B). This study demonstrated that

copper ionophore-induced cell death is predominantly dependent on

the accumulation of intracellular copper (191,192). Notably, treatment with

inhibitors targeting other established mechanisms of cell death,

including ferroptotic apoptosis (ferrostatin-1), necroptosis

(necrostatin-1) and oxidative stress (N-acetylcysteine), did not

abolish copper ionophore-induced cytotoxicity (190). Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9

knockdown experiments identified seven specific genes that

significantly mitigated the cytotoxic effects associated with the

copper ionophore elesclomol (193). Among the identified genes was

ferredoxin 1 (FDX1), a reductase known for its role in reducing

Cu(II) to the more toxic Cu(I) and serving as a direct target for

elesclomol (194,195). Additionally, six genes encoding

components of the lipoic acid pathway - specifically

lipoyltransferase 1, lipoic acid synthase (LIAS) and

dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase - or targets associated with

lipoylated proteins within the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

[including dihydrolipoyl transacetylase (DLAT), pyruvate

dehydrogenase E1 subunit α1 (PDHA1) and PDHB] were also identified

(196). Importantly, single

gene knockout analyses revealed that FDX1 and LIAS were

particularly effective at diminishing cytotoxicity associated with

copper ion carriers. Furthermore, inhibition of complex I was found

to obstruct copper-induced cell death. This finding suggests that

applying an electron transport chain inhibitor can prevent the

cytotoxic effects induced by copper when administered alongside

elesclomol in both serum-containing and serum-free media. Under

serum-free conditions, cells exhibited significant resistance to

elesclomol-mediated cytotoxicity; substantial toxicity was observed

only when elesclomol-Cu(II) complexes were present. This effect was

inhibited by the addition of TM. Furthermore, buthionine

sulfoximine has been demonstrated to sensitize cells to

copper-induced cell death by inhibiting glutamate cysteine ligase,

which results in a direct depletion of the endogenous copper

chelator GSH. The underlying mechanism involves the role of FDX1 in

promoting the lipoylation of DLAT and dihydrolipoamide

S-succinyltransferase proteins (190,197). Cu(II) binds to lipoylated DLAT,

facilitating the production of insoluble DLAT that promotes cell

death. Conversely, the conversion of Cu(II) to the more toxic Cu(I)

induces cell death and intracellular oxidative stress, leading to

an increase in heat shock protein 70 expression levels (190).

P53 activity maintains the functional integrity of

mitochondrial morphology and structure, and mutations or

deficiencies in p53 lead to significant reductions in cytochrome c

oxidase (COX) activity and respiratory metabolism (198-200). P53 also promotes the conversion

of pyruvate to acetyl coenzyme A by promoting lactate dehydrogenase

A to maintain high pyruvate levels and by promoting

dephosphorylation to activate PDH complexes (201,202). Copper-induced cell death is

also highly dependent on cellular oxidative phosphorylation, the

circulating component that targets tricarboxylic acid, and cells

are more susceptible to copper death when glycolysis is inhibited.

Studies have shown that cells dependent on mitochondrial oxidative

phosphorylation for energy are 1,000-fold more sensitive to copper

ion carriers than glycolysis-dependent cells (190).

New studies have also shown that advanced clear

cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) accumulates Cu and allocates it

to CuCOX. Copper promotes ccRCC growth through a combination of

bioenergetics, biosynthesis and redox oncogenic remodeling of body

homeostasis (203).

Through bioinformatics analysis, more and more

researchers are focusing on the important link between cuproptosis

and the cancer process (128,204). With the discovery of

cuproptosis (205-207), the interactions between copper

ionophores (208,209), copper and mitochondria, and

drugs that had previously been considered as potential anti-tumor

therapies (71), have become

increasingly clear. This has accelerated research into

copper-targeting therapies, with numerous studies on copper

chelators and ionophores demonstrating significant therapeutic

efficacy across various cancer types (Table III).

Copper-targeted therapies exhibit promising

potential in the treatment of cancer and neurodegenerative

diseases, while their immunomodulatory properties merit

comprehensive investigation. Copper ions serve as cofactors for

various enzymes and are involved in the regulation of immune cell

activity and oxidative stress responses, thereby potentially

affecting the functions of critical immune cells, such as dendritic

cells (DCs). A copper-manganese (Cu-Mn) nanocomposite demonstrates

therapeutic potential by selectively releasing Cu2+ in

the acidic tumor microenvironment (TME). The localized accumulation

of Cu2+ induces cuproptosis in cancer cells, promotes

the release of damage-associated molecular patterns, enhances DC

activation - evidenced by a 2.3-fold increase in CD80/CD86

expression - and facilitates increased infiltration of

CD8+ T cells (1.8-fold) in murine melanoma models,

thereby augmenting anti-tumor immune responses. Utilizing the

enhanced permeability and retention effect, the nanocomposite

achieves intratumoral Cu2+ concentrations 5.2-fold

higher than those attained with free chelators, without inducing

off-target toxicity, as indicated by normal liver enzyme levels

(210).

Importantly, DCs also play a critical role in

maintaining immune tolerance and their dysfunction has been

associated with the development of autoimmune disorders. In recent

years, exogenously derived tolerogenic DCs (tolDCs) have emerged as

a novel cell-based immunotherapy approach, designed to restore

immune tolerance in patients with autoimmune disorders. For

instance, Jonny et al (47) conducted a systematic review on

the therapeutic potential of tolDCs in autoimmune diseases,

including systemic lupus erythematosus, demonstrating that the

induction of tolDCs in vitro can effectively modulate T-cell

responses and promote antigen-specific immune tolerance. This

approach aligns with the objectives of copper-regulating therapies

(47).

Recent reviews have highlighted the importance of

metabolic complications in cancer (211-213), such as hypercalcemia, which

affect a significant proportion of patients with advanced

malignancies and contribute to morbidity and treatment challenges.

While hypercalcemia involves dysregulation of calcium homeostasis

often mediated by parathyroid hormone-related protein and

osteoclast activation, it shares with copper dysregulation a common

theme of metal ion imbalance in cancer pathophysiology.

Understanding these parallel mechanisms may provide synergistic

insights into targeting ion homeostasis as a therapeutic strategy.

For instance, just as bisphosphonates and denosumab are used to

manage cancer-related hypercalcemia by inhibiting bone resorption

(143), copper-chelation and

ionophore-based therapies are being explored to modulate copper

levels and induce selective cancer cell death (214,215). This complementary approach

underscores the broader potential of metal-targeting therapies in

oncology.

Among metal elements that perform essential

biological functions, such as iron, zinc, and copper, copper

demonstrates distinct advantages due to its unique chemical

properties. Copper, iron and zinc fulfil distinct roles in cellular

redox processes. The Cu+/Cu2+ redox couple

functions at a high reduction potential, facilitating efficient

catalytic activity in essential enzymatic reactions such as

cytochrome c oxidase-mediated mitochondrial respiration and

SOD-dependent antioxidant defence. Unlike iron - which can induce

non-specific oxidative damage through Fenton reactions - or zinc,

which contributes to structural and catalytic stability without

participating in redox cycling, copper supports tightly regulated

electron transfer and dynamic, chaperone-mediated signaling

processes via proteins such as Atox1. These unique properties

position copper as a specialized redox messenger capable of

mediating compartmentalized signaling pathways that are

inaccessible to iron or zinc (216,217).

Copper-based targeted therapeutic strategies,

including chelators, ionophores, and copper nanoparticles (CuNPs)

(218,219), have made notable progress in

clinical translational research (Table IV). Chelators primarily correct

copper metabolic imbalances by sequestering excess copper ions

(189), ionophores exploit

copper-dependent pathological processes by facilitating the

transport of copper ions across biological membranes (220) and CuNPs integrate the

biological activity of controlled copper ion release with the

targeted delivery capabilities of nanocarriers, thereby expanding

their application scenarios in precision therapy (221).

TM is a primary copper chelator under investigation

for its role in copper-induced cell death. Preclinical studies

indicate that TM exerts antitumor effects by inhibiting

angiogenesis and directly suppressing tumor cell proliferation

(222-224). Mechanistically, copper

depletion - achieved either through TM treatment or knockdown of

the copper transporter SLC31A1 - inhibits the progression of oral

squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) by selectively targeting cancer

stem-like cells and reducing the stability of the histone

methyltransferase EZH2. This identifies a novel 'copper-dependent

proliferation' pathway that is essential for tumor growth. Notably,

a recent clinical study evaluating TM combined with anti-PD-1

therapy in patients with locally advanced OSCC reported an

objective response rate (ORR) of 57.8% and a 12-month overall

survival (OS) rate of 80.0%, highlighting its potential to overcome

immunotherapy resistance (225).

Beyond cuproptosis, copper also modulates

ferroptosis. In pancreatic cancer models, copper promotes

ferroptosis by inducing Tax1 binding protein 1-mediated autophagic

degradation of GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4). By contrast, copper

chelators such as TM protect against ferroptosis-related tissue

damage (e.g., in acute pancreatitis) by promoting GPX4

ubiquitination and aggregation through direct binding to cysteine

residues (C107/C148) (226).

Consistent with these findings, the chelator bathocuproine sulfonic

acid enhances ferroptosis via copper depletion-mediated

mitochondrial dysfunction and impairment of antioxidant defense

(227).

Given copper's involvement in fibrosis and

angiogenesis, TM has also been evaluated in related pathological

conditions. In a bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis model, TM

downregulated VEGF expression and improved lung function (228). Its anti-inflammatory effects,

mediated by the inhibition of copper-dependent cytokines, may

further contribute to its antitumor efficacy by reducing the

infiltration of pro-angiogenic immune cells (229). Additionally, NRF2 activation

suppresses angiogenesis by inducing autophagy in vascular

endothelial cells, thereby disrupting the energy supply to cancer

cells (230).

The therapeutic potential of copper chelation

extends beyond oncology. In patients with WD with reproductive

dysfunction, engineered extracellular vesicles delivering a

copper-chelating ligand significantly reduced

non-ceruloplasmin-bound copper (42.7%) and urinary copper (47.7%),

normalized gonadotropin levels in 87.5% of patients and exhibited a

favorable safety profile (6.25% mild gastrointestinal events)

(231). In oncology clinical

settings, trientine combined with radiotherapy improved the ORR in

hepatocellular carcinoma (65.5 vs. 37.9% with radiotherapy alone)

and achieved a 12-month OS rate of 75.9% (232-234). For HER2-negative metastatic

breast cancer (235-237), a polymer-based nano-copper

chelator delivering paclitaxel achieved an ORR of 44.4% and a

6.8-fold increase in intratumoral drug accumulation (238). In case of drug-resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia, nebulized copper-chelator

nanoparticles achieved an 82.1% sputum bacterial clearance rate and

significantly shortened antipyretic time, while maintaining a

favorable safety profile (239).

Elesclomol, a highly selective copper ionophore,

binds Cu(II) to form a complex that is rapidly transported into

mitochondria (184). Within the

mitochondria, FDX1 facilitates the reduction and dissociation of

the elesclomol-Cu(II) complex, leading to the generation of ROS

(240). Notably, elesclomol

also operates through an FDX1-independent pathway that enables an

extracellular Cu(II) release pathway, distinguishing it from other

ionophores (241). This

sustained copper delivery mechanism results in a chronic elevation

of intracellular copper and ROS levels, ultimately inducing cell

death (242).

The anticancer effects of elesclomol have been

demonstrated across various malignancies. In colorectal cancer

(CRC) models, elesclomol promotes ATP7A degradation (243), leading to mitochondrial copper

accumulation, oxidative stress and the subsequent degradation of

SLC7A11 - a key component of the cystine/glutamate transporter -

thereby inducing ferroptosis (178,184). Beyond CRC, a novel natural

copper ionophore, Pochonin D (PoD), was identified in

triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). PoD covalently binds to

Cys173 on peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1), inhibiting its peroxidase

activity, promoting copper accumulation and ROS generation, and

ultimately triggering copper-dependent cell death. This study

unveils PRDX1 as a critical mediator in copper-induced cell death

and highlights a new regulatory axis between copper metabolism and

oxidative stress (244).

CuNPs have emerged as promising agents for

therapeutic applications due to their tunable physicochemical

properties and multifunctional capabilities. For instance, a CuO

nanoplatform co-loaded with elesclomol potently induces

copper-dependent cell death and enhances antitumor immunity. When

combined with PD-1 inhibitors, this strategy achieves an 85% tumor

suppression rate in melanoma models (219). In prostate cancer, the

combination of elesclomol and CuCl2 induces DLAT

aggregation and inhibits protective autophagy through mTOR

activation, thereby synergizing with docetaxel chemotherapy

(245). The application of

CuNPs extends beyond oncology. Electrospun nanofiber membranes

embedded with CuNPs exhibit broad-spectrum antibacterial activity

against pathogenic Escherichia coli (246). Furthermore, CuNPs have

demonstrated neuroprotective effects in models of AD by improving

cognitive function (247), and

ultra-small CuNPs embedded in hydrogels have been shown to

significantly accelerate diabetic wound healing (248). Despite these promising

findings, the clinical translation of CuNPs requires further

optimization to address challenges related to long-term stability

(249), targeting specificity

and scalable manufacturing (250,251).

In summary, copper-targeting approaches introduce

novel concepts and hold substantial promise in disease diagnosis

and treatment, representing a potential therapeutic strategy.

However, further comprehensive research and validation are required

for its clinical application to refine therapeutic protocols,

enhance treatment efficacy and minimize adverse effects.

The cellular uptake of copper-related therapeutics

is tightly regulated by key transporters: CTR1 and the P-type

ATPases ATP7A and ATP7B. As the primary mediator of copper influx,

CTR1 also facilitates the entry of platinum-based drugs into tumor

cells, a process that is critical for achieving therapeutic

concentrations. By contrast, ATP7A and ATP7B act as copper efflux

transporters, regulating the extrusion and subcellular

sequestration of excess copper and platinum drugs (250). Dysregulation of CTR1 and

ATP7A/B, whether through altered expression (e.g., CTR1

downregulation in drug-resistant tumors) or genetic mutations,

disrupts copper homeostasis and impairs drug accumulation. For

instance, ATP7A loss-of-function mutations cause MD (48), whereas ATP7B mutations underlie

WD (251). In neurodegenerative

diseases (such as AD), abnormal activity of copper-related

transporters can disrupt brain copper homeostasis. Excess copper

promotes Aβ protein aggregation and ROS overproduction, thereby

exacerbating neuronal damage (79,252).

Copper-targeted therapy is significantly limited by

the TME. In the hypoxic microenvironment of solid tumors (253), HIF-1α biaxially induces

resistance to copper-dependent cell death by upregulating pyruvate

dehydrogenase kinase 1/3-mediated degradation of DLAT and promoting

MT2A-mediated chelation of free copper. This results in resistance

to copper ionophores in nearly 60% of clinical samples, with the

IC50 of elesclomol increasing by 7.2-fold under hypoxic

conditions (254). Meanwhile,

vascular abnormalities, elevated interstitial pressure and

infiltration of immunosuppressive cells within the TME

significantly impair drug delivery. For instance, in hepatocellular

carcinoma, multidrug resistance mechanisms, such as the

overexpression of ATP-binding cassette transporters, act

synergistically with these TME-associated barriers to reduce

intratumoral drug accumulation (255).

Copper, an essential micronutrient, maintains

precise systemic homeostasis through coordinated regulatory

mechanisms. However, long-term administration of copper-related

therapeutics (e.g., copper ionophores and chelators), disrupts this

balance. Excess copper catalyzes the generation of ROS via the

Fenton reaction, causing oxidative damage to lipids, proteins and

DNA, and ultimately leads to cytotoxicity (249).

Although cuproptosis induced by copper ionophores

exhibits anti-tumor potential, preclinical studies have

demonstrated that prolonged high-dose treatment elicits severe

toxicity in normal tissues. For instance, mitochondrial-targeted

copper-depleting nanoparticles effectively inhibit the growth of

TNBC but still pose toxicity risks to healthy mice, thereby

narrowing the therapeutic window (256). Additionally, the hypoxic TME

promotes resistance to cuproptosis through HIF-1α activation, which

further compromises therapeutic efficacy (254).

Copper is the third most abundant trace element in

the body after iron and zinc. It is essential for processes such as

oxidative phosphorylation, free radical scavenging, angiogenesis,

bone metabolism, neurotransmission and the synthesis of

copper-dependent enzymes. On the other hand, both copper overload

and deficiency can lead to impaired cellular function or even cell

death, and their prolonged presence can trigger associated

dysfunctions or neurodegenerative disorders such as hepatomegaly,

MD, AD and PD.

It has been found that there are interactions among

copper, iron and zinc, and the use of combination drug formulations

for the treatment of related diseases may represent a new

therapeutic strategy. In the treatment of diseases associated with

copper overload, strategies such as reducing dietary copper intake,

administering oral zinc to inhibit copper absorption or employing

copper chelators to decrease intracellular copper levels may

represent promising therapeutic approaches.

In the context of cancer, copper levels in cancer

cells can exceed the tolerance threshold of normal cells, leading

to significant adverse effects. Conversely, reducing intracellular

copper levels can diminish the synthesis of the copper-dependent

enzyme SOD1, thereby substantially impairing the organism's

antioxidant capacity. Copper-induced cell death exhibits greater

sensitivity in cells reliant on oxidative phosphorylation than in

those dependent on glycolysis for energy production. Thus,

converting the metabolic pathway of cancer cells from glycolysis to

oxidative phosphorylation, coupled with exploiting the

characteristic of elevated intracellular copper, may offer a

promising new approach to cancer therapy. Comprehensive studies of

the mechanisms of copper-induced cell death may help to identify

more effective therapeutic agents, thus providing new insights and

approaches for the treatment of related diseases and improving the

prognosis of affected patients.

Copper regulation therapy has demonstrated

significant potential in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases.

Copper chelating agents, copper ion carriers and copper-based

nanoparticles have shown therapeutic effects across various disease

models. For instance, clinical studies have shown that the

combination of the copper chelating agent TM with anti-PD-1 therapy

achieves promising outcomes in the treatment of locally advanced

OSCC. The copper ion carrier elesclomol exhibits anticancer effects

in multiple malignant tumor models. CuNPs have yielded remarkable

results in cancer therapy, antibacterial applications,

neuroprotection and wound healing. However, the clinical

application of this therapeutic approach faces several challenges.

These include drug uptake dependence on key transporters such as

CTR1, ATP7A and ATP7B, whose dysregulation can compromise

therapeutic efficacy; the influence of the TME, including hypoxia

and vascular abnormalities, which may limit treatment outcomes; and

the potential toxicity associated with long-term copper exposure,

which also narrows the therapeutic window.

Not applicable.

All authors contributed to the study conception and

design. TD and HM were responsible for article design and

manuscript writing. TD and XJ were involved in the design of the

images. JT, JZ and YT were involved in the design of the study and

funding application. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Support

Program of Guizhou Province [grant nos. QKH-ZK (2023)506 and

QKH-MS(2025)373], the Education Department of Guizhou Province

[grant no. QJJ(2022)242] and Zunyi City Science and Technology and

Big Data Bureau & Zunyi Medical University joint project [grant

nos. HZ(2023)175, HZ(2023)189, (2021)1350-011 and

(2021)1350-025].

|

1

|

Bost M, Houdart S, Oberli M, Kalonji E,

Huneau JF and Margaritis I: Dietary copper and human health:

Current evidence and unresolved issues. J Trace Elem Med Biol.

35:107–115. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Huang F, Lu X, Kuai L, Ru Y, Jiang J, Song

J, Chen S, Mao L, Li Y, Li B, et al: Dual-Site Biomimetic Cu/Zn-MOF

for atopic dermatitis catalytic therapy via suppressing

FcүR-mediated phagocytosis. J Am Chem Soc. 146:3186–3199. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ash D, Sudhahar V, Youn SW, Okur MN, Das

A, O'Bryan JP, McMenamin M, Hou Y, Kaplan JH, Fukai T and

Ushio-Fukai M: The P-type ATPase transporter ATP7A promotes

angiogenesis by limiting autophagic degradation of VEGFR2. Nat

Commun. 12:30912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ding H, Gao YS, Wang Y, Hu C, Sun Y and

Zhang C: Dimethyloxaloylglycine increases the bone healing capacity

of adipose-derived stem cells by promoting osteogenic

differentiation and angiogenic potential. Stem Cells Dev.

23:990–1000. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

5

|

Akhtar H, Alhamoudi FH, Marshall J, Ashton

T, Darr JA, Rehman IU, Chaudhry AA and Reilly G: Synthesis of

cerium, zirconium, and copper doped zinc oxide nanoparticles as

potential biomaterials for tissue engineering applications.

Heliyon. 10:e291502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Han J, Luo J, Wang C, Kapilevich L and

Zhang XA: Roles and mechanisms of copper homeostasis and

cuproptosis in osteoarticular diseases. Biomed Pharmacother.

174:1165702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wei M, Huang Q, Dai Y, Zhou H, Cui Y, Song

W, Di D, Zhang R, Li C, Wang Q and Jing T: Manganese, iron, copper,

and selenium co-exposure and osteoporosis risk in Chinese adults. J

Trace Elem Med Biol. 72:1269892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xiao T, Ackerman CM, Carroll EC, Jia S,

Hoagland A, Chan J, Thai B, Liu CS, Isacoff EY and Chang CJ: Copper

regulates rest-activity cycles through the locus

coeruleus-norepinephrine system. Nat Chem Biol. 14:655–663. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Benatar M, Robertson J and Andersen PM:

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by SOD1 variants: From genetic

discovery to disease prevention. Lancet Neurol. 24:77–86. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Horvath R, Kemp JP, Tuppen HA, Hudson G,

Oldfors A, Marie SK, Moslemi AR, Servidei S, Holme E, Shanske S, et

al: Molecular basis of infantile reversible cytochrome c oxidase

deficiency myopathy. Brain. 132(Pt 11): 3165–3174. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Qu Y, Zhan Q, Du S, Ding Y, Fang B, Du W,

Wu Q, Yu H, Li L and Huang W: Catalysis-based specific detection

and inhibition of tyrosinase and their application. J Pharm Anal.

10:414–425. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Foehr R, Anderson K, Dombrowski O, Foehr A

and Foehr ED: Dysregulation of extracellular matrix and lysyl

oxidase in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV skin fibroblasts.

Orphanet J Rare Dis. 19:92024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wassenberg T, Deinum J, van Ittersum FJ,

Kamsteeg EJ, Pennings M, Verbeek MM, Wevers RA, van Albada ME, Kema

IP, Versmissen J, et al: Clinical presentation and long-term

follow-up of dopamine beta hydroxylase deficiency. J Inherit Metab

Dis. 44:554–565. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

De Feyter S, Beyens A and Callewaert B:

ATP7A-related copper transport disorders: A systematic review and

definition of the clinical subtypes. J Inherit Metab Dis.

46:163–173. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Stalke A, Behrendt A, Hennig F, Gohlke H,

Buhl N, Reinkens T, Baumann U, Schlegelberger B, Illig T, Pfister

ED and Skawran B: Functional characterization of novel or yet

uncharacterized ATP7B missense variants detected in patients with

clinical Wilson's disease. Clin Genet. 104:174–185. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li Y, Ma J, Wang R, Luo Y, Zheng S and

Wang X: Zinc transporter 1 functions in copper uptake and

cuproptosis. Cell Metab. 36:2118–2129 e6. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ohgami RS, Campagna DR, McDonald A and

Fleming MD: The Steap proteins are metalloreductases. Blood.

108:1388–1394. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wyman S, Simpson RJ, McKie AT and Sharp

PA: Dcytb (Cybrd1) functions as both a ferric and a cupric

reductase in vitro. FEBS Lett. 582:1901–1906. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kleven MD, Dlakic M and Lawrence CM:

Characterization of a Single b-type Heme, FAD, and metal binding

sites in the transmembrane domain of six-transmembrane epithelial

antigen of the prostate (STEAP) family proteins. J Biol Chem.

290:22558–22569. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kirsipuu T, Zadorožnaja A, Smirnova J,

Friedemann M, Plitz T, Tõugu V and Palumaa P: Copper(II)-binding

equilibria in human blood. Sci Rep. 10:56862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Linder MC: Ceruloplasmin and other copper

binding components of blood plasma and their functions: An update.

Metallomics. 8:887–905. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Moriya M, Ho YH, Grana A, Nguyen L,

Alvarez A, Jamil R, Ackland ML, Michalczyk A, Hamer P, Ramos D, et

al: Copper is taken up efficiently from albumin and

alpha2-macroglobulin by cultured human cells by more than one

mechanism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 295:C708–C721. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu N, Lo LS, Askary SH, Jones L, Kidane

TZ, Trang T, Nguyen M, Goforth J, Chu YH, Vivas E, et al:

Transcuprein is a macroglobulin regulated by copper and iron

availability. J Nutr Biochem. 18:597–608. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang Y, Hodgkinson V, Zhu S, Weisman GA

and Petris MJ: Advances in the understanding of mammalian copper

transporters. Adv Nutr. 2:129–137. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

25

|

Chen L, Li N, Zhang M, Sun M, Bian J, Yang

B, Li Z, Wang J, Li F, Shi X, et al: APEX2-based proximity labeling

of Atox1 Identifies CRIP2 as a nuclear copper-binding protein that

regulates autophagy activation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl.

60:25346–25355. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

González-Ballesteros MM, Sánchez-Sánchez

L, Espinoza-Guillén A, Espinal-Enríquez J, Mejía C, Hernández-Lemus

E and Ruiz-Azuara L: Antitumoral and antimetastatic activity by

mixed chelate copper(II) Compounds (Casiopeínas®) on

triple-negative breast cancer, in vitro and in vivo models. Int J

Mol Sci. 25:88032024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kuo YM, Gybina AA, Pyatskowit JW,

Gitschier J and Prohaska JR: Copper transport protein (Ctr1) levels

in mice are tissue specific and dependent on copper status. J Nutr.

136:21–26. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Vizcaíno C, Mansilla S and Portugal J: Sp1

transcription factor: A long-standing target in cancer

chemotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 152:111–124. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xue Q, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D, Liu J

and Chen X: Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy.

Autophag. 19:2175–2195. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Liang ZD, Tsai WB, Lee MY, Savaraj N and

Kuo MT: Specificity protein 1 (sp1) oscillation is involved in

copper homeostasis maintenance by regulating human high-affinity

copper transporter 1 expression. Mol Pharmacol. 81:455–464. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Ohse VA, Klotz LO and Priebs J: Copper

homeostasis in the model organism C. elegans. Cells. 13:7272024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hatori Y and Lutsenko S: The role of

copper chaperone Atox1 in coupling redox homeostasis to

intracellular copper distribution. Antioxidants (Basel). 5:252016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lutsenko S, Barnes NL, Bartee MY and

Dmitriev OY: Function and regulation of human copper-transporting

ATPases. Physiol Rev. 87:1011–1046. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sturtz LA, Diekert K, Jensen LT, Lill R

and Culotta VC: A fraction of yeast Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase and

its metallochaperone, CCS, localize to the intermembrane space of

mitochondria. A physiological role for SOD1 in guarding against

mitochondrial oxidative damage. J Biol Chem. 276:38084–38089. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang Y, Branicky R, Noë A and Hekimi S:

Superoxide dismutases: Dual roles in controlling ROS damage and

regulating ROS signaling. J Cell Biol. 217:1915–1928. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Miriyala S, Spasojevic I, Tovmasyan A,

Salvemini D, Vujaskovic Z, St Clair D and Batinic-Haberle I:

Manganese superoxide dismutase, MnSOD and its mimics. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1822:794–814. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

37

|

Boyd SD, Calvo JS, Liu L, Ullrich MS,

Skopp A, Meloni G and Winkler DD: The yeast copper chaperone for

copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (CCS1) is a multifunctional

chaperone promoting all levels of SOD1 maturation. J Biol Chem.

294:1956–1966. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

38

|

Ding Y, Chen Y, Wu Z, Yang N, Rana K, Meng

X, Liu B, Wan H and Qian W: SsCox17, a copper chaperone, is

required for pathogenic process and oxidative stress tolerance of

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Sci. 322:1113452022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Banci L, Bertini I, Ciofi-Baffoni S,

Hadjiloi T, Martinelli M and Palumaa P: Mitochondrial copper(I)

transfer from Cox17 to Sco1 is coupled to electron transfer. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 105:6803–6808. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ge EJ, Bush AI, Casini A, Cobine PA, Cross

JR, DeNicola GM, Dou QP, Franz KJ, Gohil VM, Gupta S, et al:

Connecting copper and cancer: From transition metal signalling to

metalloplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 22:102–113. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

41

|

McCann C, Quinteros M, Adelugba I, Morgada

MN, Castelblanco AR, Davis EJ, Lanzirotti A, Hainer SJ, Vila AJ,

Navea JG and Padilla-Benavides T: The mitochondrial Cu(+)

transporter PiC2 (SLC25A3) is a target of MTF1 and contributes to

the development of skeletal muscle in vitro. Front Mol Biosci.

9:10379412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

van Rensburg MJ, van Rooy M, Bester MJ,

Serem JC, Venter C and Oberholzer HM: Oxidative and haemostatic

effects of copper, manganese and mercury, alone and in combination

at physiologically relevant levels: An ex vivo study. Hum Exp

Toxicol. 38:419–433. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ruturaj, Mishra M, Saha S, Maji S,

Rodriguez-Boulan E, Schreiner R and Gupta A: Regulation of the

apico-basolateral trafficking polarity of the homologous

copper-ATPases ATP7A and ATP7B. J Cell Sci. 137:jcs2612582024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Guttmann S, Nadzemova O, Grünewald I,

Lenders M, Brand E, Zibert A and Schmidt HH: ATP7B knockout

disturbs copper and lipid metabolism in Caco-2 cells. PLoS One.

15:e02300252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Dmitriev OY and Patry J: Structure and

mechanism of the human copper transporting ATPases: Fitting the

pieces into a moving puzzle. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr.

1866:1843062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Percival SS: Copper and immunity. Am J

Clin Nutr. 67(5 Suppl): 1064S–1068S. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Jonny, Sitepu EC, Nidom CA, Wirjopranoto

S, Sudiana IK, Ansori ANM and Putranto TA: Ex vivo-generated

tolerogenic dendritic cells: Hope for a definitive therapy of

autoimmune diseases. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 46:4035–4048. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Backal A, Velinov M, Garcia J and Louis

CL: Novel, likely pathogenic variant in ATP7A associated with

Menkes disease diagnosed with ultrarapid genome sequencing. BMJ

Case Rep. 17:e2597922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Tümer Z and Møller LB: Menkes disease. Eur

J Hum Genet. 18:511–518. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

50

|

Moller LB, Mogensen M, Weaver DD and

Pedersen PA: Occipital horn syndrome as a result of splice site

mutations in ATP7A. no activity of ATP7A splice variants missing

exon 10 or exon 15. Front Mol Neurosci. 14:5322912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Batzios S, Tal G, DiStasio AT, Peng Y,

Charalambous C, Nicolaides P, Kamsteeg EJ, Korman SH, Mandel H,

Steinbach PJ, et al: Newly identified disorder of copper metabolism

caused by variants in CTR1, a high-affinity copper transporter. Hum

Mol Genet. 31:4121–4130. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Garnica A, Chan WY and Rennert O:

Copper-histidine treatment of Menkes disease. J Pediatr.

125:336–338. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Moini M, To U and Schilsky ML: Recent

advances in Wilson disease. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6:212021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Weiss KH, Członkowska A, Hedera P and

Ferenci P: WTX101 - an investigational drug for the treatment of

Wilson disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 27:561–567. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kreuder J, Otten A, Fuder H, Tümer Z,

Tønnesen T, Horn N and Dralle D: Clinical and biochemical

consequences of copper-histidine therapy in Menkes disease. Eur J

Pediatr. 152:828–832. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Christodoulou J, Danks DM, Sarkar B,

Baerlocher KE, Casey R, Horn N, Tümer Z and Clarke JT: Early

treatment of Menkes disease with parenteral copper-histidine:

Long-term follow-up of four treated patients. Am J Med Genet.

76:154–164. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ramchandani D, Berisa M, Tavarez DA, Li Z,

Miele M, Bai Y, Lee SB, Ban Y, Dephoure N, Hendrickson RC, et al:

Copper depletion modulates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation

to impair triple negative breast cancer metastasis. Nat Commun.

12:73112021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Xu B, Wang S, Li R, Chen K, He L, Deng M,

Kannappan V, Zha J, Dong H and Wang W: Disulfiram/copper

selectively eradicates AML leukemia stem cells in vitro and in vivo

by simultaneous induction of ROS-JNK and inhibition of NF-κB and

Nrf2. Cell Death Dis. 8:e27972017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Theophanides T and Anastassopoulou J:

Copper and carcinogenesis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 42:57–64. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhong CC, Zhao T, Hogstrand C, Chen F,

Song CC and Luo Z: Copper (Cu) induced changes of lipid metabolism

through oxidative stress-mediated autophagy and Nrf2/PPARγ

pathways. J Nutr Biochem. 100:1088832022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Wang Q, Sun Y, Zhao A, Cai X, Yu A, Xu Q,

Liu W, Zhang N, Wu S, Chen Y and Wang W: High dietary copper intake

induces perturbations in the gut microbiota and affects host

ovarian follicle development. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

255:1148102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Tsang T, Posimo JM, Gudiel AA, Cicchini M,

Feldser DM and Brady DC: Copper is an essential regulator of the

autophagic kinases ULK1/2 to drive lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Cell

Biol. 22:412–424. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Conforti RA, Delsouc MB, Zorychta E,

Telleria CM and Casais M: Copper in gynecological diseases. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:175782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Compston A: Progressive lenticular

degeneration: a familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis

of the liver, by S. A. Kinnier Wilson, (From the National Hospital,

and the Laboratory of the National Hospital, Queen Square, London)

Brain 1912: 34; 295-509. Brain. 132:1997–2001. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kipker N, Alessi K, Bojkovic M, Padda I

and Parmar MS: Neurological-type wilson disease: Epidemiology,

clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Cureus.

15:e381702023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Członkowska A, Litwin T, Dusek P, Ferenci

P, Lutsenko S, Medici V, Rybakowski JK, Weiss KH and Schilsky ML:

Wilson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 4:212018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Kirk FT, Munk DE, Swenson ES, Quicquaro

AM, Vendelbo MH, Larsen A, Schilsky ML, Ott P and Sandahl TD:

Effects of tetrathiomolybdate on copper metabolism in healthy

volunteers and in patients with Wilson disease. J Hepatol.

80:586–595. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Bruha R, Marecek Z, Pospisilova L,

Nevsimalova S, Vitek L, Martasek P, Nevoral J, Petrtyl J, Urbanek

P, Jiraskova A and Ferenci P: Long-term follow-up of Wilson

disease: natural history, treatment, mutations analysis and

phenotypic correlation. Liver Int. 31:83–91. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Członkowska A, Litwin T, Karliński M,

Dziezyc K, Chabik G and Czerska M: D-penicillamine versus zinc

sulfate as first-line therapy for Wilson's disease. Eur J Neurol.

21:599–606. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Brewer GJ: Practical recommendations and

new therapies for Wilson's disease. Drugs. 50:240–249. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Xie J, Yang Y, Gao Y and He J:

Cuproptosis: Mechanisms and links with cancers. Mol Cancer.

22:462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Członkowska A and Litwin T: Wilson disease

- currently used anticopper therapy. Handb Clin Neurol.

142:181–191. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Lambert C, Beraldo H, Lievre N,

Garnier-Suillerot A, Dorlet P and Salerno M: Bis(thiosemicarbazone)

copper complexes: Mechanism of intracellular accumulation. J Biol

Inorg Chem. 18:59–69. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Ayton S and Bush AI: β-amyloid: The known

unknowns. Ageing Res Rev. 65:1012122021. View Article : Google Scholar

|