Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CCVDs),

encompassing ischemic and hemorrhagic conditions affecting the

heart and brain, are primarily caused by adverse lifestyle factors

such as smoking, physical inactivity, poor diet, hypertension,

hyperlipidemia and inadequate glycemic control (1-4).

These diseases have become the leading cause of death worldwide

(5,6). Coronary heart disease is the

predominant type of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Additionally,

conditions such as heart failure (HF), myocardial hypertrophy and

myocarditis also fall under the spectrum of CVDs (7). Cerebrovascular diseases include

ischemic stroke (IS) and hemorrhagic stroke (6). In China, the burden of CCVDs is

particularly severe. The 2022 China Cardiovascular Health and

Disease Report (8) indicated

that there were ~330 million patients with CVD, with CCVDs

accounting for two out of every five deaths. The incidence is

rising, particularly among individuals aged 30-50 years (9,10). CCVDs continue to pose a global

health challenge, contributing to high rates of morbidity and

mortality, while placing substantial medical and financial strain

on healthcare systems (9).

Although pharmacological and surgical interventions can improve

vascular conditions, they fall short in promoting tissue

regeneration and restoring function in areas affected by CCVDs

(11). Thus, identifying novel

therapeutic targets is crucial for the effective management of

these diseases.

MicroRNA-155 (miR-155/miRNA-155) is a highly

conserved non-coding single-stranded RNA encoded by the B-cell

integration cluster (BIC) gene located on chromosome 21 (12). As a key member of the miRNA

family, miR-155 regulates post-transcriptional processes by binding

to the 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR) of target gene mRNAs through

complementary base pairing (12). As a multifunctional regulatory

molecule, miR-155 is involved in a wide range of biological

processes, including immune responses, inflammation, cell

proliferation and apoptosis, vascular homeostasis, and

tumorigenesis (13-15). Dysregulation of miR-155

expression is closely associated with the onset and progression of

various pathological conditions (such as brain injury, pulmonary

fibrosis and fatty liver disease) (16-18).

miR-155 serves a role in the pathogenesis and

progression of CCVDs, including atherosclerosis (AS), myocardial

hypertrophy, myocardial infarction (MI), ischemia-reperfusion

(I/R), HF, stroke and aneurysm (19-24). The mechanisms of action of

miR-155 include the regulation of inflammation, immunity,

angiogenesis and other key processes (25-28). Currently, miR-155 is considered

to be a promising diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for

CCVDs (29-32). The present review explores the

biogenesis, regulation and function of miR-155, summarizes the

molecular mechanisms by which miR-155 influences the progression of

various CCVDs, and examines therapeutic strategies targeting

miR-155, with the aim of contributing to the understanding of CCVD

pathogenesis and advancing precision treatment approaches. Compared

with previous studies, to the best of our knowledge, the present

review is the first to systematically integrate the dual regulatory

roles of miR-155 in both CVDs and cerebrovascular diseases,

elucidating its contradictory functions in processes such as

inflammation and autophagy through distinct target genes [for

example, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and suppressor of

cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1)]. The present review also compiles

data on miR-155 inhibitors (such as cobomarsen) from the oncology

field, exploring their cross-disciplinary therapeutic potential,

and proposes an innovative biomimetic nanocarrier strategy [such as

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) antibody-modified

exosomes] to address existing technological gaps in prior

research.

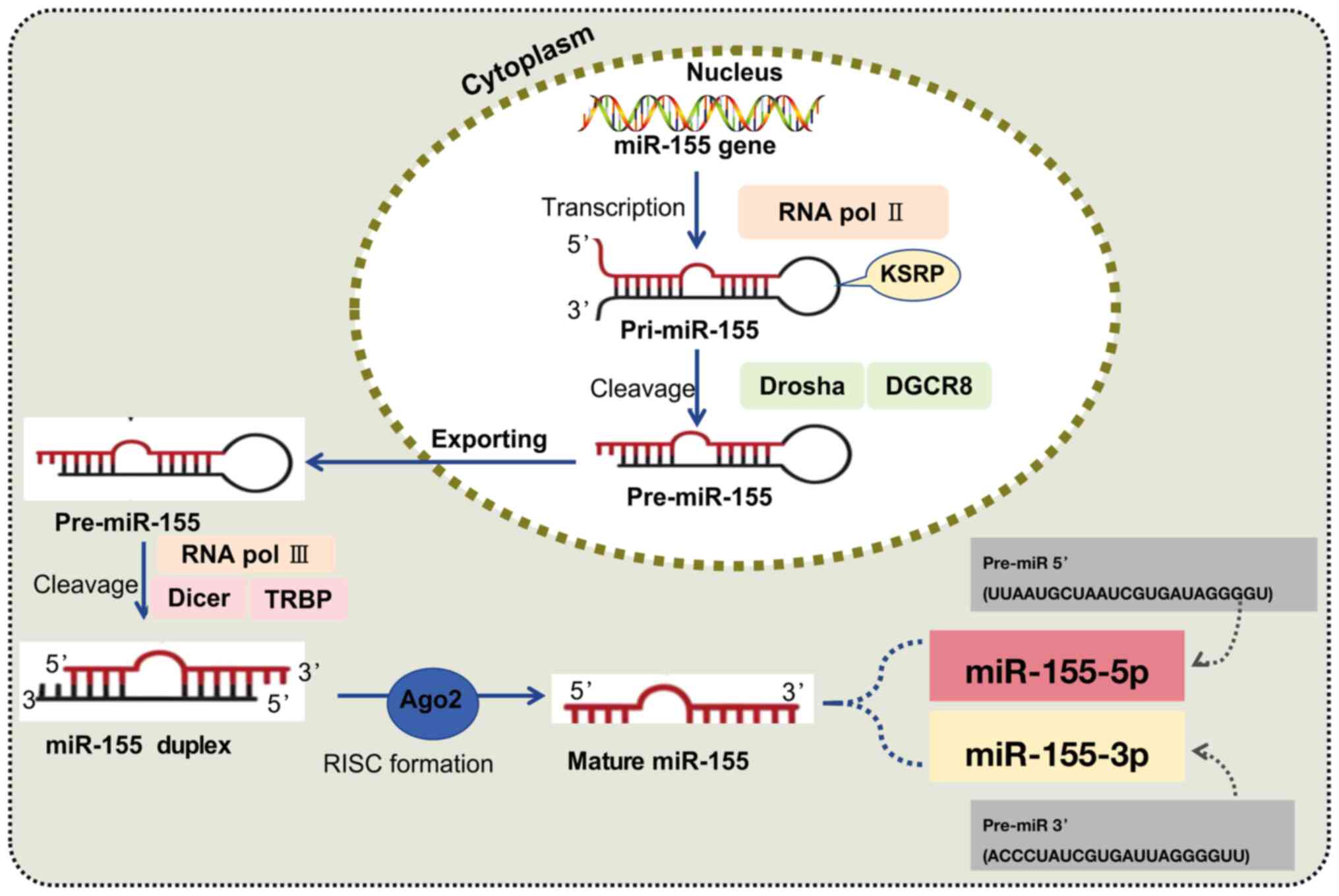

The majority of miRNAs are generated through two

primary steps: First, in the nucleus, the primary transcript

(pri-miRNA) is processed by RNA polymerase II and the

double-stranded RNA-binding protein complex Drosha/DiGeorge

syndrome critical region gene 8 (DGCR8) to produce the miRNA

precursor (pre-miRNA). Second, in the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNA is

further processed by the type III RNA nuclease and the

transactivation-responsive RNA-binding protein complex Dicer/TAR

RNA-binding protein to generate the mature miRNA form (33). The human miR-155 gene is located

within the third exon of the BIC gene on chromosome 21. The mature

sequence of miR-155 is highly conserved across evolution,

specifically targeting the 3'-UTR of target gene mRNAs through its

seed sequence (comprising nucleotides 2-8 at the 5' end), thereby

mediating post-transcriptional gene silencing or mRNA degradation

(34). Argonaute protein 2 binds

to the miR-155 double-stranded complex, forming the core of the

RNA-induced silencing complex and producing single-stranded DNA

molecules (34). The precursor

miRNA hairpin has two arms that can generate biologically active

mature miRNAs. The miRNA derived from the 5' arm is referred to as

miR-155-5p, while that from the 3' arm is referred to as

miR-155-3p. Notably, miR-155-5p exhibits higher biological activity

(34) (Fig. 1). Additionally, miR-155 is

expressed not only in hematopoietic cells but also in a wide range

of tissues, including reproductive tissues, fibroblasts, epithelial

tissues and the central nervous system (35-37).

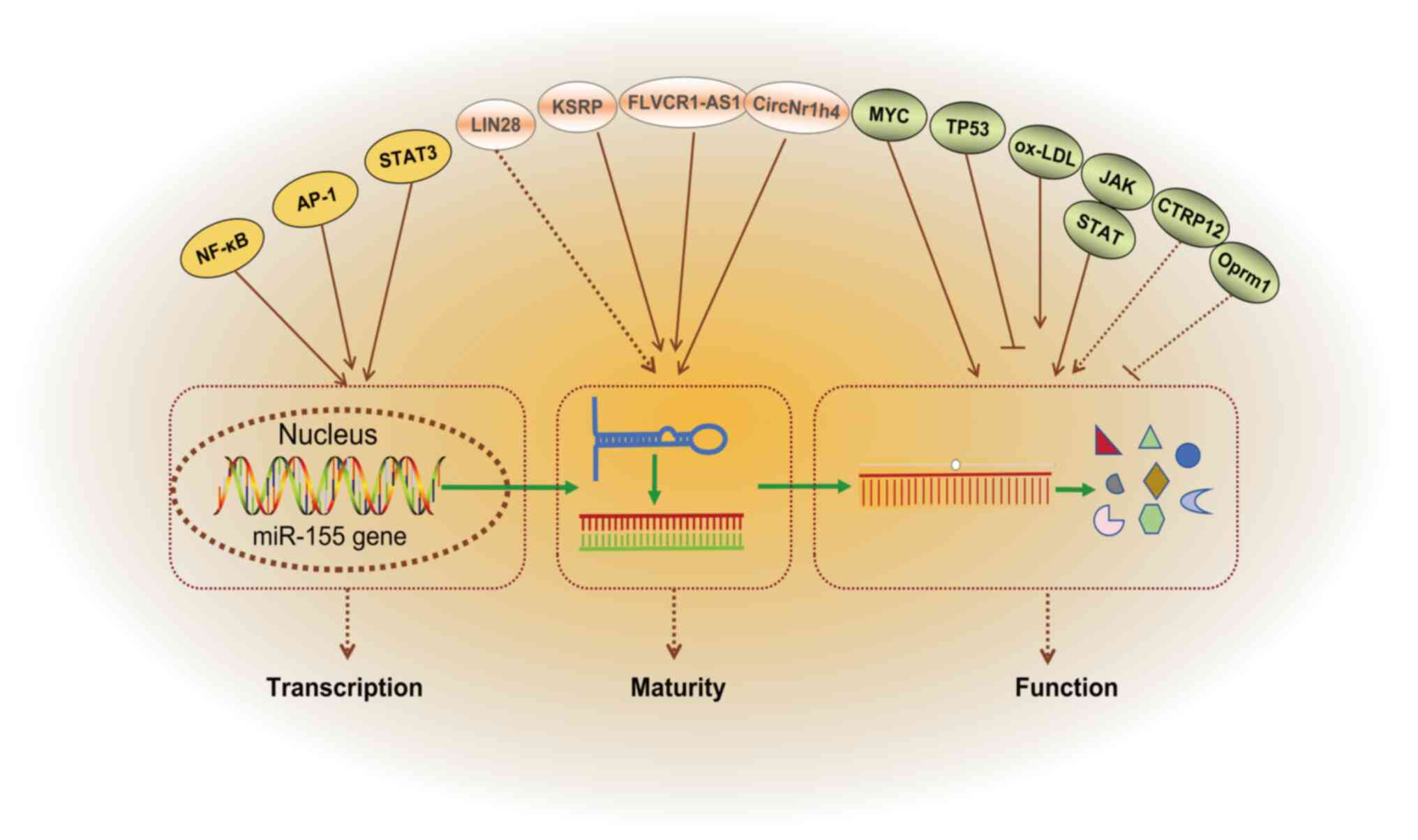

miR-155 is a highly conserved miRNA, and its

expression is tightly regulated at multiple levels, including

transcriptional regulation, post-transcriptional modifications and

epigenetic control (38-40) (Fig. 2). The physiological expression of

miR-155 is essential for immune homeostasis, while pathological

dysregulation contributes to the progression of various diseases,

including AS, stroke and hyperlipidemia (41-43).

The transcription of miR-155 primarily relies on the

synergistic action of cis-regulatory sequences and trans-regulatory

elements in the promoter region (12,44). Activation of toll like receptors

(TLRs) or cytokines (such as TNF-α and IFN-γ) within inflammatory

signaling pathways induces miR-155 expression by activating

transcription factors such as NF-κB and adaptor protein complex-1

(AP-1), which directly bind to the miR-155 promoter region

(38,39). In B and T cells, antigen receptor

(B cell receptor/T cell receptor) signaling activates downstream

transcription factors (such as STAT3) through the PI3K/AKT or MAPK

pathways, promoting miR-155 expression (36,45). Additionally, the transcriptional

activity of the BIC gene can be dynamically regulated by DNA

methylation and histone acetylation. For example, reduced

methylation of the miR-155 promoter region in tumors is closely

associated with its upregulation (46).

The maturation of miR-155 involves the cleavage of

pri-miR-155 to pre-miR-155 and cytoplasmic transport of

pre-miR-155, a process regulated by RNA binding proteins such as

KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP). KSRP binds to the

stem-loop structure of pri-miR-155 and recruits the Drosha-DGCR8

complex to promote the processing of pri-miR-155 into pre-miR-155

(37). Lineage protein 28

(LIN28) family proteins (LIN28A/B), as RNA-binding proteins, can

selectively block the maturation of miRNAs such as let-7 by

inhibiting the processing of pri-miRNAs by Drosha/Dicer complexes

(47). We hypothesized that

LIN28 may regulate miR-155 through a similar mechanism, although

further research is needed to confirm this. Additionally,

competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) can indirectly modulate the

functional activity of miR-155 by sequestering it via the 'sponge

effect'. For example, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) such as feline

leukemia virus subgroup C receptor 1-antisense RNA 1 can bind to

miR-155, thereby reducing its inhibition of target genes (40). Lu et al (48) identified that circNr1h4 acted as

a ceRNA interacting with miR-155-5p, subsequently influencing the

pathological progression of renal damage in salt-sensitive

hypertensive mouse models.

In disease environments, the expression of miR-155

is often dysregulated due to imbalanced regulatory networks

(49). Specifically, the

activation of cancer-related genes (such as MYC) or suppression of

tumor-suppressor genes (such as TP53) within the tumor

microenvironment can trigger persistently elevated levels of

miR-155, enhancing cellular proliferation and metastasis (50-52). For instance, overexpression of

the BIC gene increases miR-155 levels in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma (53). During chronic

inflammatory conditions, sustained inflammatory stimuli [such as

high levels of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) in AS]

maintain miR-155 expression, promoting eNOS production and

exacerbating tissue damage through continuous activation of the

NF-κB signaling pathway (54).

Furthermore, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, synovial

fibroblasts aberrantly activate miR-155 via the Janus kinase

(JAK)-STAT pathway, leading to the release of inflammatory

mediators, including IL-6 and TNF-α (55). Wang et al (56) demonstrated that C1q tumor

necrosis factor related protein 12 (CTRP12) could mitigate AS by

enhancing reverse cholesterol transport and reducing vasculitis

through the miR-155-5p/liver X receptor α (LXRα) pathway. However,

it remains unclear whether CTRP12 directly regulates miR-155-5p

(56). A study (57) utilizing cerebral I/R injury (IRI)

mouse models has demonstrated that upregulated expression levels of

lncRNA opioid receptor Mu 1 (Oprm1) alleviated cellular apoptosis

induced by cerebral IRI via the Oprm1/miR-155/GATA binding protein

3 (GATA3) pathway. However, the direct regulatory relationship

between Oprm1 and miR-155 remains undetermined (57).

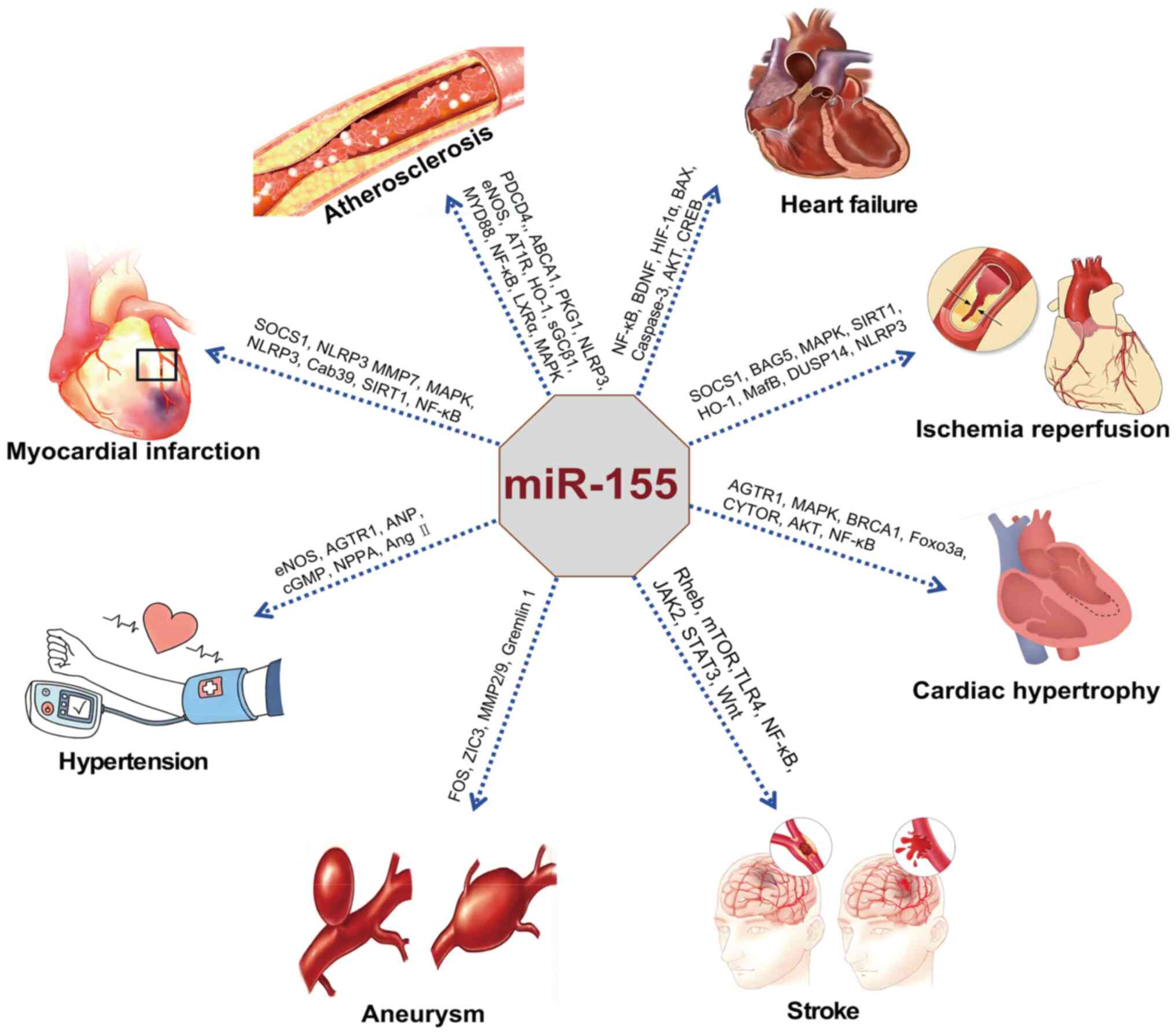

miR-155 is extensively involved in physiological and

pathological processes, including immune regulation, inflammatory

responses, tumorigenesis and metabolic homeostasis, by targeting

the expression of downstream genes (36,38,53,54). miR-155 contributes to the

development of CCVDs by regulating the expression of multiple

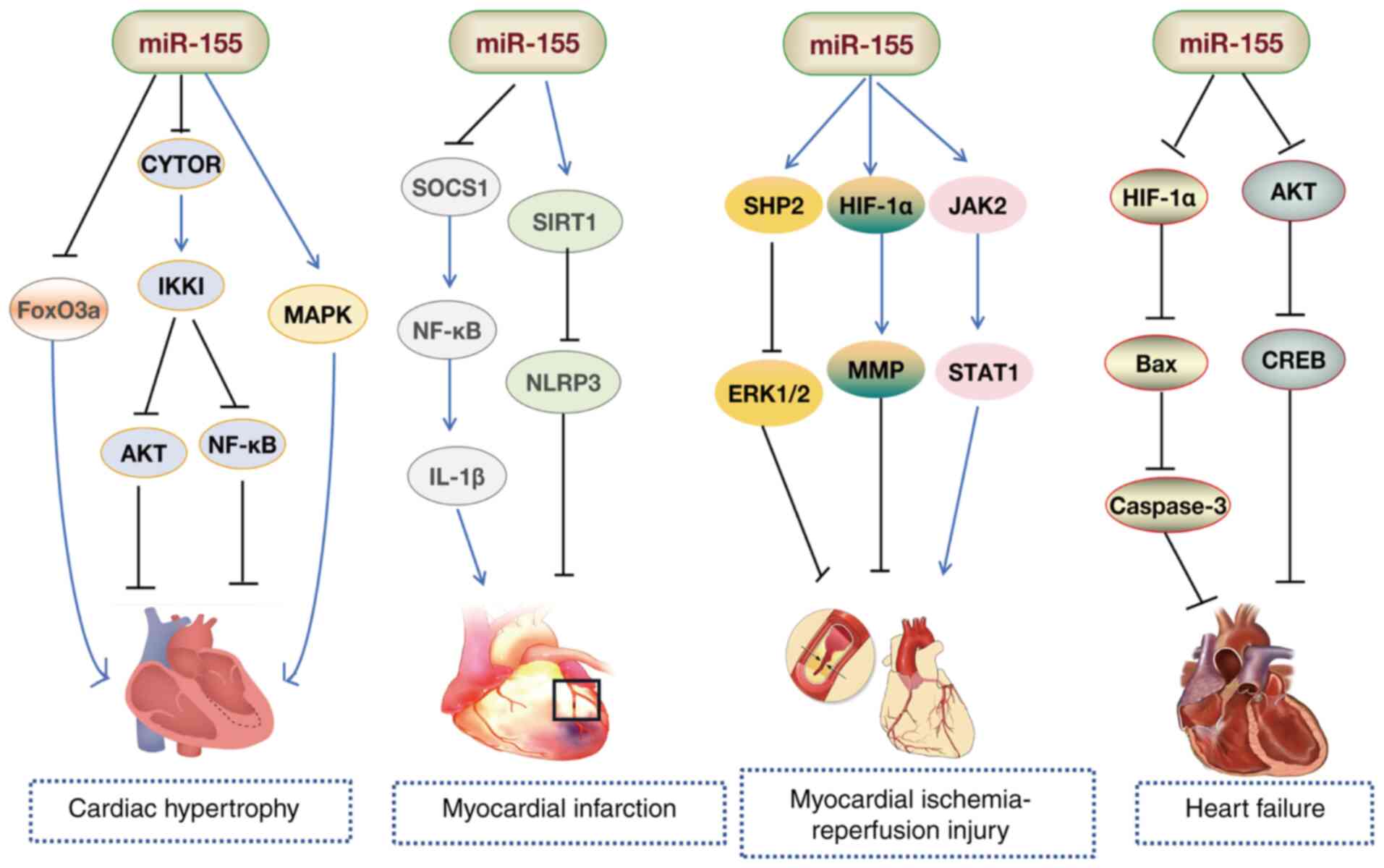

molecules, some of which are shown in Fig. 3. miR-155 serves a critical role

in both adaptive and innate immunity. One study has shown that in T

cells, miR-155 targets and inhibits the protein expression of

SOCS1, enhances STAT5 signaling, promotes the differentiation of T

helper type 1 (Th1) and T helper type 17 (Th17) cells, and sustains

the anti-infective immune response (36). In the regulation of inflammation,

miR-155 is the only miRNA upregulated by macrophages in response to

various inflammatory stimuli, including virus-related signals [such

as the poly(I) synthetic analog of double-stranded RNA and

interferons IFN-β/γ] and bacteria-related stimuli [for example, TLR

ligands such as lipopolysaccharide, CpG DNA and Pam3Cys-Ser-(Lys)

4]. These stimuli activate miR-155 expression via myeloid

differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88)- or Toll/IL-1 receptor

domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-dependent TLR

signaling pathways, while IFN-β/γ indirectly induces miR-155

expression through TNF-α autocrine signaling, involving TNFR1.

miR-155 integrates the TLR, IFN and TNF-α signaling networks,

activating transcription through the JNK/AP-1 pathway (38). miR-155 exhibits notable

carcinogenic properties within the tumor microenvironment. The

overexpression of miR-155 promotes tumor cell proliferation,

invasion and angiogenesis by targeting and inhibiting tumor

suppressor genes, such as tumor protein p53 inducible nuclear

protein 1 (50,51) and SH2-containing inositol

5'-phosphatase 1 (58,59). miR-155 may also exert anticancer

effects in certain solid tumors (for example, breast cancer, liver

cancer and lymphoma) by inhibiting TGF-β signaling (60-63), highlighting its functional

complexity.

As a non-coding RNA molecule, miR-155 serves as a

multidimensional regulator in the pathological processes of CCVDs.

miR-155 participates in key mechanisms such as inflammation,

endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and apoptosis by

targeting the expression of downstream genes (64-68). This section will delve into the

specific molecular mechanisms through which miR-155 influences the

progression of CCVDs, including AS, HF, MI, hypertension, IRI,

stroke and aneurysm (Tables

I-III).

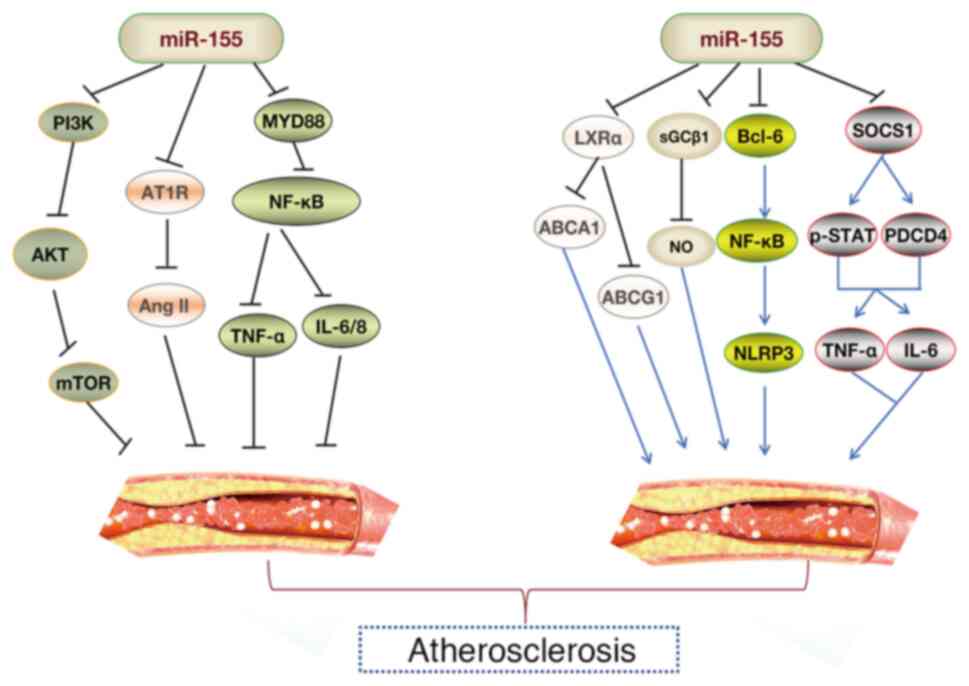

AS represents a pathological condition characterized

by inflammatory responses and lipid accumulation, serving a role in

the progression of CCVDs (69).

The pathogenesis of AS involves a prolonged immunological

inflammatory process, initiated by various pro-inflammatory

mediators interacting with multiple cell types, including

endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and

monocytes/macrophages (25,54,70). miR-155, a versatile miRNA, is

highly expressed in atherosclerotic plaques of both murine and

human subjects (71), emerging

as a critical molecular factor in controlling the initiation and

progression of AS (Fig. 4).

ECs serve as the interface between the blood vessel

wall and the bloodstream, facilitating the exchange of oxygen and

nutrients between the blood and tissues (72). ECs serve a pivotal role in

inflammation responses, thrombosis regulation and vascular tone

modulation, directly influencing CVD progression (72). eNOS generates nitric oxide (NO),

a crucial molecule for maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis.

Aberrant eNOS expression is often linked to endothelial dysfunction

and CVD (73,74). Sun et al (75) demonstrated that miR-155 directly

targeted eNOS, where elevated miR-155 levels reduced eNOS

expression and NO production in HUVECs, impairing

acetylcholine-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation in human

mammary arteries. miR-155 is co-expressed with the angiotensin II

type I receptor (AT1R) in ECs and VSMCs. The molecular mechanism

involves miR-155 binding specifically to the 3'-UTR of AT1R mRNA,

inhibiting its translation, and thus, mitigating the pathological

effects of angiotensin II (Ang II) on HUVECs (76). This finding highlights the

pivotal role of the miR-155-AT1R axis in vascular function

regulation. EC apoptosis is a form of endothelial injury and is

closely associated with the development of AS (73,74). Lee et al (77) demonstrated that G protein subunit

α12 protected HUVECs from serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis by

maintaining miR-155 expression. Additionally, another study

demonstrated that overexpression of miR-155 inhibited palmitic

acid-induced apoptosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

and inflammatory cytokine release in HUVECs by suppressing the Wnt

signaling pathway (78).

Endothelial autophagy, as a cytoprotective mechanism, maintains

endothelial homeostasis by clearing damaged organelles and

misfolded proteins, serving a critical role in preventing the onset

and progression of AS (79,80). Under physiological conditions,

ECs utilize autophagy to remove ox-LDL and ROS, thereby preventing

lipid accumulation and inflammatory cytokine release (81). In HUVECs, ox-LDL induces

autophagy and elevates miR-155 expression. Increased miR-155 levels

promote autophagy, while reduced miR-155 expression suppresses

autophagic activity in vascular ECs (82). Further research by Yin et

al (83) indicated that

elevated miR-155 levels enhanced ox-LDL-mediated autophagy in

HUVECs by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Metabolic

abnormalities and genetic variations in homocysteine (Hcy)

metabolism lead to hyperhomocysteinemia and endothelial

dysfunction, which are both hallmark features of AS and key

contributors to CVD (84).

Research by Witucki and Jakubowski (85) demonstrated that metabolites of

Hcy elevated the expression levels of miR-21, miR-155, miR-216 and

miR-320c, which in turn reduced autophagy in human ECs, a process

critical for maintaining vascular homeostasis. The

stress-responsive enzyme heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) protects cells

under stress conditions and promotes endothelial anti-inflammatory

and vasodilatory responses (86). Pulkkinen et al (87) showed that miR-155 exerted a

protective effect on endothelial inflammation by reducing the

translation of BTB domain and CNC homolog 1 (BACH1), which induced

HO-1 expression in ECs. Another study demonstrated that both

Abelmoschus esculentus and metformin ameliorated endothelial

inflammation induced by a high-fat diet in rats through enhanced

miR-155 expression, primarily by inhibiting TNF receptor associated

factor 6 and NF-κB p65 activation (88). Yang et al (89) found that miR-155 not only

regulated hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) expression under

hypoxic conditions but also enhanced the angiogenic potential of

ECs by targeting E2F transcription factor 2. Promoting angiogenesis

is a key feature of healthy ECs.

miR-155 is a critical regulator involved in cardiac

inflammation and hypertrophic responses (103-106). Bao and Lin (107) observed a marked increase in

miR-155 levels in the myocardial tissue of mice with Coxsackievirus

B3-induced myocarditis. Functional experiments in vitro

showed that miR-155 mitigated myocardial damage by inhibiting the

NF-κB pathway (107).

Macrophage infiltration is a hallmark of viral myocarditis, and

Zhang et al (108) found

that silencing of miR-155 reduced viral myocarditis-induced cardiac

damage and dysfunction by promoting macrophage M2 phenotype

polarization. Additionally, inhibition of miR-155 improved

experimental autoimmune myocarditis in mice by enhancing the

Th17/regulatory T cell (Treg) immune response (109). These findings suggest that

miR-155 suppression could serve as an effective treatment for

autoimmune myocarditis. Zhang et al (110) demonstrated that Astragalus

mongholicus (Fisch.) Bge alleviated immune imbalances in

peripheral Tregs in children with viral myocarditis by reducing

miR-155 levels. Collectively, these studies (107-109) position miR-155 as a promising

diagnostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target for

cardiomyopathy.

Research has also indicated a decrease in miR-155

levels in animal and patient models of myocardial hypertrophy

(111-113). Overexpression of miR-155

induces hypertrophy in H9C2 cardiomyocytes in vitro

(114). Conversely, inhibition

of miR-155 alleviates myocardial hypertrophy in H9C2 rat

cardiomyocytes by downregulating angiotensin II receptor subtype 1

(AGTR1) and inhibiting the calcium signaling pathway activated by

AGTR1 (115). Seok et al

(116) found that the absence

of miR-155 protected the heart from pathological cardiac

hypertrophy, primarily by reducing jumonji and AT-rich interaction

domain containing 2 expression. Another study revealed that EVs

derived from hypertrophic cardiomyocytes activated the

miR-155-mediated MAPK (ERK, JNK and p38) pathway, inducing

macrophage inflammation and exacerbating myocardial cell damage

(117). Studies have

demonstrated that miR-155-overexpressing macrophages directly

targeted and suppressed FoxO3a expression in cardiomyocytes of

uremic mice via EVs, leading to reduced FoxO3a levels, which

promoted cardiomyocyte pyroptosis, and exacerbated hypertrophy and

fibrosis (118,119). Additionally, Fan et al

(120) demonstrated that

resveratrol, a polyphenol compound, alleviated cardiac hypertrophy

and improved cardiac function by activating BRCA1 in

cardiomyocytes. This mechanism involved BRCA1 activation, which

suppressed miR-155 expression, thereby enhancing FoxO3a expression

and reducing cardiac hypertrophy (120). Furthermore, Yuan et al

(121) demonstrated that

cytoskeleton regulator RNA (CYTOR) deletion decreased IKKI protein

expression, while IKKI deficiency triggered cardiac hypertrophy via

the AKT and NF-κB pathways. miR-155 suppression partially

attenuated the effects of CYTOR. The authors proposed that CYTOR

functions as a ceRNA for miR-155, counteracting miR-155-mediated

inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase subunit ε suppression, thus

offering protection against cardiac hypertrophy (121). These studies highlight the

critical role of miR-155 in cardiac hypertrophy (117-121) (Fig. 5).

MI is an acute cardiovascular event resulting from

the rapid reduction or interruption of coronary blood flow, leading

to ischemia, hypoxia and necrosis of myocardial cells. The primary

cause is coronary atherosclerotic plaque rupture or thrombosis

(122). Plaque rupture often

results from an imbalance between macrophage-mediated degradation

and fibroblast repair functions (123). Wang et al (124) found that upregulated miR-155

was predominantly present in macrophages and fibroblasts in the

damaged heart, while pri-miR-155 was exclusively expressed in

macrophages. Mice deficient in miR-155 exhibited increased

proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts and collagen production, along

with reduced inflammation in the damaged heart (124). Notably, suppression of miR-155

reduces nerve growth factor expression by decreasing the phagocytic

activity of M1 macrophages and the inflammation mediated by the

SOCS1/NF-κB pathway, thereby mitigating sympathetic remodeling and

ventricular arrhythmias induced by MI in mice (125,126). Pro-inflammatory

macrophage-mediated degradation of connexin 43 (Cx43) serves a

pivotal role in arrhythmia following MI (127). A study has demonstrated that

miR-155 inhibited the downregulation of macrophage-mediated IL-1β

and MMP7 expression via the SOCS1/NF-κB pathway, reducing Cx43

degradation after MI (128).

Aging impairs the function of human mesenchymal stem

cells (MSCs), reducing their therapeutic potential in MI (129). Hong et al (130) showed that inhibition of

miR-155-5p suppressed MSC aging through the Cab39/AMPK signaling

pathway. This suggests that miR-155-5p could be a novel target for

restoring the vitality of bone marrow MSCs and enhancing their

cardioprotective effects (130). Guo et al (21) also found that miR-155 levels

dynamically increased in the hearts of mice with MI and in neonatal

rat ventricular myocytes injured by hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2). Downregulation of miR-155 promoted

apoptosis induced by MI by targeting RNA binding protein Quaking

(21). Hypoxia/reoxygenation

(H/R)-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis serves a critical role in MI

pathogenesis. Inhibition of miR-155-5p can prevent NLRP3

inflammasome activation by targeting sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), thus

reducing H/R-induced cardiomyocyte pyroptosis (131). lncRNA XIST promotes cardiac

fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix (ECM)

accumulation by acting as a sponge for miR-155-5p, thus

facilitating MI formation (132). Another study demonstrated that

in a mouse model of MI with dyslipidemia, the deletion of the

miR-155 gene did not reduce infarct size or chronic HF but

decreased the density of myofibroblasts in ischemic scars (133). An investigation into

miR-155-based therapeutic strategies has revealed that rosuvastatin

potentially reduces cardiovascular events and inflammatory markers

(INF-γ, TNF-α and IL-6) in patients with acute coronary syndrome by

suppressing the miR-155/Src homology 2-containing inositol

5-phosphatase 1 (SHIP-1) signaling cascade (134). Furthermore, combination of

American ginseng with Danshen increased the serum levels of

hepatocyte growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in

acute MI rats, enhanced myocardial microvascular density and CD31

levels, and suppressed the miR-155-5p/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway,

promoting angiogenesis, compared with those in the acute myocardial

infarction model group (135).

These findings highlight the potential of miR-155 as a target for

the treatment of MI (Fig.

5).

IRI refers to the pathological phenomenon where

tissue, such as cardiac or brain tissue, experiences restored blood

flow after a period of ischemia, but this restoration exacerbates

cell damage (136). This

process is commonly observed in vascular recanalization therapies

(such as thrombolysis and percutaneous coronary intervention

surgery), cardiac or cerebrovascular surgeries, and organ

transplantation following acute MI or IS (137,138). IRI poses a challenge in the

field of CCVDs, highlighting the urgent need for the identification

of novel therapeutic targets.

miR-155 expression increases in myocardial tissue

following IRI, which is associated with elevated levels of TNF-α,

IL-1β, CD105 and caspase-3, as well as enhanced leukocyte

infiltration (139). Knockout

of miR-155 reduces inflammatory cell recruitment and decreases ROS

production in white blood cells (139). Notably, miR-155 exacerbates the

inflammatory response, leukocyte infiltration and tissue damage in

IRI by regulating SOCS-1-dependent ROS production (139). Chen et al (20) found that inhibition of miR-155

reduced the MI area by specifically regulating HIF-1α, inhibited

IRI-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis, maintained MMP levels and

alleviated myocardial injury in rats. Furthermore, inhibition of

miR-155 led to targeted regulation of Bcl-2-associated athanogene 5

and MAPK/JNK signaling, reducing myocardial IRI and the size of MI

(140). Another study found

that, in IRI mice, miR-155 was expressed at high levels, while

SIRT1 expression was low. The expression levels of SIRT1, confirmed

to be a target gene of miR-155, were increased following

sevoflurane treatment, which reduced miR-155 levels, improved

cardiac function, reduced infarct size and inhibited myocardial

cell apoptosis (141). Greco

et al (142) observed

that myocardial IRI-induced EVs exhibited pro-inflammatory

features, exacerbating cardiac injury. The specific molecular

mechanism involved these EVs transferring miR-155-5p to

macrophages, thereby enhancing the inflammatory response via

activation of the JAK2/STAT1 pathway (142). This suggests that targeting EVs

could be a potential therapeutic approach for the management of

IRI. An investigation has demonstrated that miR-155 deletion

improved cardiac ultrasound measurements in IRI mice, with

reductions in MI areas, myocardial fibrosis and cellular apoptosis

(including reducing the expression levels of caspase-3, caspase-4

and caspase-11) (143).

Investigation of the underlying mechanism revealed that decreased

miR-155 expression increased SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine

phosphatase 2 levels and alleviated IRI-induced necroptosis by

suppressing ERK1/2 pathway activation (143). These findings highlight the

potential of miR-155 as a key therapeutic target in the treatment

of myocardial IRI (Fig. 5).

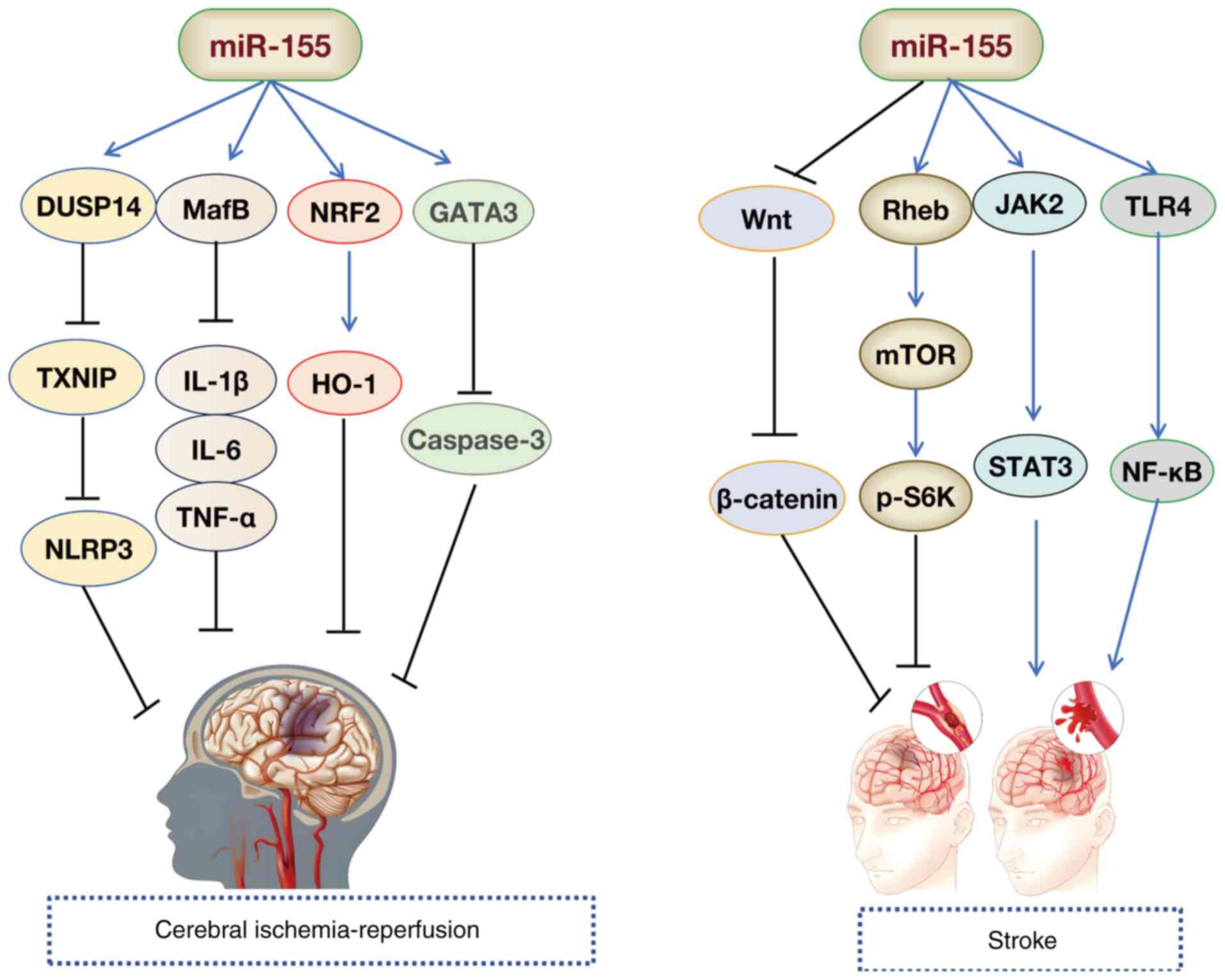

The elimination of the miR-155 gene protects against

brain injury and hemorrhagic transformation induced by I/R

(142). Multiple studies have

corroborated these findings. Jiang et al (144) found that miR-155 deficiency

reduced NO production and eNOS expression by activating the Notch

pathway, thereby alleviating the damage caused by cerebral I/R in

mice with middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Inhibition of

miR-155 increases cell viability and reduces apoptosis by targeting

the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/HO-1 pathway,

preventing neuronal damage induced by cerebral I/R (65). Furthermore, downregulation of

miR-155 mitigates IRI by targeting V-Maf avian musculoaponeurotic

fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B, improving the neurological

function and inhibiting inflammatory responses [IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α,

inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2]

(145). Another study also

found that in MCAO/reperfusion mouse models and oxygen glucose

deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R)-induced SH-SY5Y cells, miR-155-5p

targeted dual specificity phosphatase 14 (DUSP14) by regulating the

NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, thereby accelerating cerebral

IRI (146). Suppression of

miR-155-5p reduces cellular apoptosis and cerebral injury (146). Research by Shi et al

(147) revealed that decreased

miR-155-5p expression alleviated cerebral I/R-induced inflammation

and cell death by modulating the DUSP14/thioredoxin interacting

protein/NLRP3 signaling cascade. Notably, increased expression of

lncRNA Oprm1 mitigates apoptosis following cerebral I/R damage via

the Oprm1/miR-155/GATA3 regulatory axis (57). Furthermore, elevated Parkinson's

disease protein 7 expression suppresses miR-155 levels, thereby

enhancing SHP-1 expression and modulating astrocyte activation

during cerebral IRI (148).

These findings suggest potential therapeutic strategies for

managing cerebral IRI (Fig.

6).

HF is a clinical syndrome characterized by a decline

in the pumping function of the heart, leading to an inability to

meet the metabolic needs of the body, with common symptoms

including dyspnea, fatigue and fluid retention (149). The etiology of HF encompasses

conditions such as hypertension, coronary heart disease and

cardiomyopathy (150). The

underlying pathological mechanisms involve myocardial remodeling,

inflammation and fibrosis (151). Li et al (152) utilized bioinformatics and

experimental validation to investigate the potential role of

miR-155 in HF. The authors found that miR-155 may regulate the

viability and apoptosis of H9c2 cardiomyocytes by targeting and

modulating G protein-coupled receptor 18 (152). In the same year, another study

reported that in established rat and cell models of HF,

overexpression of Sirt1 upregulated NF-κB p65 and miR-155,

promoting brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and

reducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis. The authors proposed that Sirt1

alleviated HF in rats via the NF-κB p65/miR-155/BDNF signaling

cascade (153). Gao et

al (154) found that

schisandrin protected rat cardiomyocytes and prevented congestive

HF by regulating miR-155 expression and mediating the AKT/cAMP

response element-binding protein (CREB) signaling pathway. Another

study revealed that miR-155 expression was downregulated in the

myocardial tissue of mice with HF. Overexpression of miR-155

inhibited myocardial cell apoptosis (via inhibition of Bax and

downstream caspase-3) through HIF-1α, reducing cardiac function

damage in HF mice (155). These

studies (152-154) highlight the critical role of

miR-155 in myocardial protection and suggest its potential for

improving cardiac function through the regulation of specific

molecules (for example, HIF-1α, AKT and CREB) (Fig. 5).

Elevated miR-155 levels in the circulation of

hypertensive patients have been found to be positively associated

with inflammatory markers, indicating their involvement in the

pathological process of hypertension through immune regulation

(68,156). Animal models have confirmed

that miR-155 deficiency alleviates perivascular inflammation and

reduces blood pressure (157).

Yang et al (68)

demonstrated that levamlodipine improved vascular inflammation and

endothelial dysfunction by regulating miR-155 in hypertensive rats,

thereby modulating the receptor activator of nuclear factor

κ-B/receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand/osteoprotegerin

pathway. Additionally, studies have shown that miR-155 regulates

vascular tone and endothelial-dependent vasodilation by targeting

the eNOS and vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathways

(75,158). Overexpression of miR-155 can

inhibit eNOS activity, reducing NO production, promoting

endothelial dysfunction and contributing to hypertension

development (75). VSMCs are

essential for maintaining vascular function, and

inflammation-induced VSMC dysfunction can also lead to hypertension

(159). Park et al

(26) found that miR-155,

induced by NF-κB, downregulated sGCβ1 expression, impaired the VSMC

contractile phenotype and disrupted NO induced vasodilation,

leading to VSMC functional damage. Another study revealed that in

the tunica media (VSMCs) of hypertensive rats, miR-155 expression

was elevated. Inhibition of miR-155 reduced systolic and diastolic

blood pressure, increased expression of p27 and α-smooth muscle

actin (α-SMA) in the tunica media, and decreased the thickness of

the tunica media. These findings suggest that miR-155 has

therapeutic potential for hypertension, with its expression levels

being positively associated with vascular wall thickness (160).

Ang II is a key peptide hormone in the

renin-angiotensin system, serving a critical role in regulating

vasoconstriction and renal sodium reabsorption (161). The physiological and

pathophysiological effects of Ang II are primarily mediated through

AT1R (162). Zheng et al

(157) found that

overexpression of miR-155 in cells reduced Ang II-induced α-SMA

expression, suggesting that miR-155 may regulate the

differentiation of rat aortic adventitia fibroblasts and inhibit

AT1R expression. Additionally, research has shown that vascular

mineralocorticoid receptors promote vasoconstriction and increase

blood pressure with age by modulating miR-155 (163). Specifically restoring miR-155

in aged mineralocorticoid receptor-intact mice reduces calcium

voltage-gated channel subunit α1 2 and AgtR1 mRNA levels,

alleviating L-type calcium channel-mediated and Ang II-induced

vasoconstriction and oxidative stress (163). Atrial natriuretic peptide

(ANP), secreted by primary atrial myocytes, lowers blood pressure

by increasing cGMP levels, inducing vasodilation, diuresis and

sodium excretion (164).

Vandenwijngaert et al (165) found that compared with

individual use of miR-425 or miR-155, the combination of miR-425

and miR-155 demonstrated greater suppression of natriuretic peptide

A expression and cGMP production in cardiomyocytes. These studies

showed that promoting the expression of miR-155 may represent an

effective strategy for regulating blood pressure in hypertensive

disorders (163-165).

Stroke is the second leading cause of death

worldwide, and IS is a major subtype (166). miR-155 serves a role in the

progression of IS (167,168).

With ongoing research, the molecular mechanisms of miR-155 in

protecting against IS are becoming clearer (Fig. 6). Xing et al (169) used an in vivo rat model

of MCAO and an in vitro oxygen-glucose deprivation cell

model to simulate IS onset. The authors found that inhibition of

miR-155 could protect against IS by promoting the phosphorylation

of S6K through the Ras homolog enriched in brain/mTOR pathway

(169). Ischemia induces

autophagy via miR-155, contributing to nerve damage (170). Yang et al (170) revealed that miR-155-induced

autophagy altered inflammatory responses and exacerbated ischemic

brain injury by regulating the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in ischemic brain

tissue. Another study indicated that miR-155 worsened cellular

damage in IS by activating the TLR4/MYD88 signaling pathway

(22). The study by Adly Sadik

et al (171)

demonstrated that miR-155 may promote inflammatory responses

post-IS by activating the JAK2/STAT3 axis. A recent study found

that miR-155 inhibited the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling,

restored the Th17/Treg balance and prevented acute IS in mice

(172). These findings

highlight that miR-155 is involved in multiple signaling pathways

and targets in IS. Knockdown of miR-155 expression and the use of

specific inhibitors to block miR-155 targets may offer a novel

approach for treating IS by interrupting signaling pathway

transmission. Research has shown that geniposide and ginsenoside

Rg1 protect against focal cerebral ischemia in MCAO model rats by

inhibiting miR-155-5p in microglia following ischemic injury

(173). Additionally,

Opa-interacting protein 5-AS1 inhibits oxidative stress and

inflammation by regulating the miR-155-5p/interferon regulatory

factor 2 binding protein 2 axis, alleviating OGD/R-induced damage

in HMC3 and SH-SY5Y cells, offering a novel targeted therapeutic

molecule for IS treatment (174).

Arterial aneurysms are typically asymptomatic in

their early stages, but as the aneurysm expands, the risk of

rupture increases, which can lead to fatal bleeding (175). Based on anatomical location,

aneurysms are classified into abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs),

thoracic aortic aneurysms and intracranial aneurysms (IAs)

(176). miR-155 promotes

macrophage infiltration by upregulating pro-inflammatory factors

such as TNF-α and IL-6, suggesting that miR-155 may contribute to

the inflammatory process during aneurysm development (24,177). Zhang et al (24) found that inhibition of miR-155

prevented AAA formation by regulating macrophage inflammation. The

development of AAA was linked to the proliferation and apoptosis of

VSMCs. Their study also found that overexpression of miR-155

increased the levels of MMP-2, MMP-9, iNOS and monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1 in ApoE-/- mouse models,

stimulating VSMC proliferation and migration. Another study found

that miR-155-5p expression was increased in VSMCs damaged by

H2O2 or NaAsO2. Overexpression of

miR-155-5p inhibited VSMC survival and promoted aneurysm formation

by targeting FOS proto-oncogene (FOS) and Zic family member 3

(ZIC3) (178). These findings

suggest that miR-155 could be a therapeutic target for AAA

treatment. The degradation of the ECM in blood vessels is another

key factor in aneurysm formation. miR-155 enhances the activity of

MMP-2/9, accelerating the degradation of collagen and elastin

(24). Inhibition of miR-155 can

alleviate ECM damage and delay AAA progression (24). Yang et al (178) found that reduced miR-155

expression increased the incidence of IA rupture by upregulating

MMP-2 expression, particularly in subjects with the SNP rs767649

genotype. This SNP in the miR-155 promoter reduces its

transcriptional activity, suggesting a genetic predisposition to

increased aneurysm risk (178).

Additionally, another study found that miR-155-5p, derived from

tumor-associated macrophages, can target IA formation and

macrophage infiltration induced by Gremlin1 (179). These findings highlight

miR-155-5p as a potential therapeutic target for IAs.

miR-155, a key regulatory miRNA, serves a pivotal

role in the onset and progression of CCVDs by influencing

pathological and physiological processes such as inflammation,

oxidative stress and apoptosis (180-182). Research has shown that miR-155

is upregulated in the blood and tissues of patients with CCVDs such

as MI (183) and stroke

(171), indicating its

potential as an effective marker for early diagnosis and prognosis

evaluation.

In a clinical study of 89 patients with

inflammatory cardiomyopathy (iCMP), Obradovic et al

(185) observed elevated plasma

miR-155 levels in patients with iCMP compared with those with

dilated cardiomyopathy, suggesting miR-155 as a novel biomarker for

iCMP diagnosis. Previous studies have indicated a marked increase

in miR-155 expression in both myocardial tissue and blood after MI,

which was strongly associated with inflammatory responses (IL-17A,

IL-6 and TNF-α) and myocardial injury (183,186). Notably, Wang et al

(187) found urinary miR-155

levels to be 30-fold higher in the MI group compared with healthy

individuals, suggesting urinary miR-155 as a potential non-invasive

diagnostic biomarker for MI.

miR-155 holds promise as a biomarker for CCVDs,

serving a pivotal role in their pathogenesis and progression.

Alterations in miR-155 expression are strongly associated with

disease severity and clinical prognosis. Quantitative detection of

miR-155 expression can facilitate earlier identification of disease

risk, providing a foundation for timely clinical intervention and

therapeutic management (171,184,185,189). Therefore, further exploration

of the mechanistic pathways of miR-155, along with the development

of miR-155-based diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies

targeting miR-155, presents substantial potential for breakthroughs

in the prevention and treatment of these diseases.

In the field of precision medicine, innovative

therapies based on miRNAs are gaining increasing attention, with

miR-155 standing out due to its pivotal role in the pathological

and physiological processes of CVDs (19,60,193). As a critical therapeutic

candidate, miR-155 has garnered interest in biomedical research.

While preclinical investigations of miR-155 extend across various

disciplines beyond CCVDs, the mechanistic insights gained have

considerable translational implications for the advancement of

vascular medicine (13,46,58). Notably, cobomarsen, a synthetic

oligonucleotide inhibitor specifically targeting miR-155, has shown

therapeutic promise in oncology. Its action, validated in

hematologic malignancies, demonstrates particular efficacy in

managing non-Hodgkin lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (in a

xenograft NSG mouse model of the activated B-cell subtype of

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), with ongoing clinical trials

confirming favorable pharmacodynamic profiles (194,195). These studies indicate that

cobomarsen can inhibit tumor growth and regulate critical signaling

pathways, such as the JAK/STAT, MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways, to

exert antitumor effects (194,195). In fibrosis research, local

injection of miR-155 antagonists has been shown to inhibit the

Wnt/β-catenin and AKT signaling pathways, thereby reducing skin

collagen deposition and improving fibrosis (196). Experiments have revealed that

this antagomiR-155 targets the regulation of casein kinase 1α and

SHIP-1, blocking key fibrotic pathways (196). Additionally, systemic delivery

of miR-155-5p inhibitors (antigomiR-155) has been shown to reduce

lipid accumulation in macrophages and reduce atherosclerotic plaque

burden in ApoE-/- mice (197). Another study involving

intravenous injection of miR-155 inhibitors starting 48 h

post-distal MCAO in mice demonstrated a reduction in C-C motif

chemokine ligand 3 and C-C motif chemokine ligand 12 cytokine

expression after 7 days, with notable increases in IL-10, IL-4,

IL-6, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, IL-5 and IL-17 levels

after 14 days (27). These

findings suggest that miR-155 inhibition in stroke models alters

the temporal progression of cytokine expression, potentially

influencing inflammation and tissue repair following cerebral

ischemia (27). Furthermore,

magnetic resonance imaging examination revealed that the miR-155

inhibitor group exhibited a 34% reduction in infarct volume

compared with the control group after 21 days (14.43% in controls

vs. 9.5% in the inhibitor group (42). These findings highlight the

potential of miRNA-based therapies in targeting key pathogenic

pathways in diseases. miR-155-based therapies, in particular, hold

great promise for the treatment of CVDs. With ongoing research and

technological advancements, this novel approach may offer new

options for the treatment of patients with CVD.

miR-155, a highly conserved non-coding RNA,

regulates target gene expression and serves a critical role in the

pathological processes of various CCVDs, including AS, MI, HF,

hypertension and stroke. miR-155 is involved in mechanisms such as

endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis

and fibrosis. Notably, miR-155 exhibits a dual nature, exerting

both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects, depending on

the specific disease context and microenvironment. Additionally,

miR-155 holds promise as a diagnostic biomarker for CCVDs and

represents a potential target for gene therapy. For example,

cobomarsen, an anti-miR-155 oligonucleotide, has shown therapeutic

efficacy in a xenograft NSG mouse model of the activated B-cell

subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (195).

However, current research on miR-155 faces several

challenges. Firstly, the mechanistic complexity of miR-155 remains

incompletely understood. For instance, in AS, overexpression of

miR-155 inhibits palmitic acid-induced apoptosis, ROS production

and pro-inflammatory cytokine release in HUVECs by suppressing the

Wnt signaling pathway (78),

thereby mitigating the progression of AS. However, studies have

also demonstrated that overexpression of miR-155-5p reduces AKT1

levels and its phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting VSMC

proliferation and migration (92) while decreasing VSMC apoptosis

(71), which conversely promotes

AS development. Across different diseases, miR-155 exhibits

functional complexity. In AS, elevated miR-155 levels enhance

ox-LDL-mediated autophagy in HUVECs by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway (83), thereby

alleviating inflammation during AS progression. Conversely,

researchers have found that overexpression of miR-155-5p promotes

aneurysm formation by targeting FOS and ZIC3 to inhibit VSMC

survival (178). These

discrepancies may stem from the multifunctionality of its upstream

and downstream genes. While multiple mRNAs have been identified as

direct targets of miR-155-5p, these targets could also be regulated

by other miRNAs. Furthermore, alterations in miR-155-5p may induce

expression changes in associated upstream genes, such as lncRNAs

and circular RNAs, potentially contributing to its differential

expression patterns in the same disease. This remains a key area

for future research. Secondly, validation of miR-155 target genes

remains insufficient. Numerous studies have demonstrated that

miR-155 can regulate the expression levels of various molecules

(for example, Oprm1 and CTRP12) (23,57), but have not yet confirmed whether

miR-155 directly targets and modulates their expression, with the

intermediate molecules between them remaining unclear. Thirdly,

animal models, predominantly murine models (such as

ApoE- mice), have limitations due to species-specific

differences from human diseases, and clinical data are still

limited. Fourthly, most clinical studies related to miR-155 have

small sample sizes, which compromises the stability and reliability

of the findings and makes it difficult to comprehensively and

accurately reflect the true role of miR-155 in relevant diseases or

physiological processes. Additionally, small-scale studies may fail

to adequately account for inter-individual variations, such as

variations in age, sex, ethnicity, lifestyle and underlying medical

conditions, which influence miR-155 expression and function,

thereby limiting the generalizability and clinical applicability of

the conclusions. Lastly, therapeutic strategies targeting miR-155

are in the early stages. While cobomarsen, a miR-155 inhibitor,

shows efficacy in oncology, its safety, delivery efficiency and

long-term effects in CCVDs require further validation.

The proposed solutions to address these challenges

primarily include: First, utilizing single-cell sequencing and

spatial transcriptomics to elucidate the cell type-specific

functions of miR-155, complemented by the development of humanized

animal models that better replicate human disease

microenvironments. Second, employing multimodal experimental

validation, such as dual-luciferase assays to confirm direct

binding interactions, followed by RT-qPCR and western blot analyses

of target genes (such as Oprm1 and CTRP12) after miR-155

overexpression or inhibition, with subsequent validation in both

cellular and animal models. Third, implementing multicenter

clinical studies incorporating organoid models to assess

therapeutic efficacy and safety. Finally, phase I/II trials should

prioritize high-risk CCVD populations (for example, patients with

familial hypercholesterolemia) (198), integrating dynamic monitoring

technologies such as fluorescent reporter genes for real-time

tracking of miR-155 activity, with dosage adjustments based on

circulating miR-155 levels.

Systemic regulation targeting miR-155 requires

careful consideration of several key issues. First, off-target

effects present significant risks: miR-155 modulates hundreds of

genes (such as eNOS, SOCS1 and Bcl-6), and systemic inhibition or

overexpression may disrupt physiological functions in non-target

tissues, potentially causing immune dysregulation. As a key

regulator of Th1/Th17 cell differentiation, miR-155 suppression

could compromise anti-infective immunity and increase

susceptibility to infections (172,199). Paradoxically, inhibition of

miR-155 could enhance VSMC proliferation, leading to vascular

stenosis or restenosis and disrupting vascular homeostasis

(200). Second, delivery

systems lack specificity: Current technologies, such as lipid

nanoparticles or viral vectors, struggle to precisely target

diseased tissues, risking hepatorenal toxicity (201,202). Third, dose-dependent toxicity

may arise: miR-155 exhibits nonlinear disease associations;

insufficient levels may impair anti-inflammatory effects (41), while excessive expression could

promote fibrosis [for example, cardiac fibrosis (203)]. Future research should

integrate single-cell sequencing and CRISPR screening to clarify

cell-specific miR-155 functions and develop tissue-targeted

delivery systems (such as exosomal vectors) (92,177,180,204,205). Conventional carriers, such as

lipid or viral vectors, face issues such as hepatic sequestration

(causing hepatotoxicity) and poor vascular barrier penetration (for

example, of the blood-brain barrier) (206,207). Innovative solutions include: i)

Bioinspired nanocarriers, including engineering exosomes to

encapsulate miR-155 inhibitors (such as antagomirs) for degradation

protection, with surface-conjugated VCAM-1 antibodies for precise

binding to inflamed endothelium; ii) biomimetic membrane coatings,

such as macrophage membrane-wrapped nanoparticles [for example,

poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-polyethylene glycol cores loaded with

inhibitors] that leverage innate chemotaxis to migrate toward

lesions (such as plaques and infarcted myocardium); and iii)

preclinical validation in large animal models with dynamic

monitoring (such as fluorescent reporters) for real-time dose

adjustments (208-210).

Despite being in the early stages of development,

miRNA-based therapies demonstrate substantial potential. As of

August 2025, no miRNA drugs have received global approval, although

~100 candidates are actively being investigated across therapeutic

areas, including oncology, rare diseases, CVDs, metabolic diseases

and inflammatory conditions (211-213). Clinical progress remains

measured, with only a few candidates advancing to clinical trials.

Notably, obefazimod (targeting miR-124) for ulcerative colitis

achieved a 16.4% clinical remission rate in phase III trials

(NCT05507216; July 2025), with the ABTECT-1 subgroup reaching a

clinical remission rate of 19.3% (214). This indicates that it is a

highly promising miRNA drug candidate for the future treatment of

ulcerative colitis. In CVDs, CDR132L (a miR-132 inhibitor)

completed a phase II trial (NCT05350969), demonstrating myocardial

functional recovery in HF (215). Other notable candidates include

miravirsen (miR-122 inhibitor for hepatitis C virus; phase II;

NCT01200420) (216), CWT-001

(miR-29a mimic for tendinopathy; phase II; NCT06192927) and

TTX-MC138 (miR-10b inhibitor for breast/pancreatic cancers; phase

I; NCT06260774). However, safety concerns have stalled some

pipelines. For instance, a trial investigating MRX34 (miR-34a

mimic; NCT01829971) was halted due to severe immune-related adverse

events and is currently under reevaluation (217), highlighting the translational

challenges. No miR-155-targeted therapies have currently entered

clinical trials. However, these clinical studies (214-217) strongly support the general

feasibility of miRNA-based therapeutics, providing robust evidence

for miR-155 as a potential therapeutic target. With deepening

insights into miRNA mechanisms, future development of

miR-155-specific therapies may yield breakthroughs in treating

CCVDs.

In conclusion, the integration of preclinical

research with emerging breakthroughs in miRNA therapeutics across

diverse medical fields positions miR-155 as a promising therapeutic

candidate for CCVDs. This strategic approach may pave the way for

novel therapeutic interventions in cerebrovascular disease. The

expanding understanding of the multifunctional regulation of

miR-155 in CCVD pathophysiology has enhanced the prospects for

precision-targeted therapies, potentially driving paradigm shifts

in vascular medicine. As knowledge of the dual regulatory roles of

this miRNA in both vascular homeostasis and disease progression

deepens, rationally designed miR-155 modulators may ultimately

redefine therapeutic standards for complex cerebrovascular

conditions.

Not applicable.

PW contributed to the conception and design, and

critically revised the manuscript. XZ was responsible for

conceptualization, validation and writing the original draft of the

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Liaoning Province Science

and Technology Plan Joint Program (grant no. 2024-MSLH-305), the

Basic Research Projects for Higher Education Institutions of

Liaoning Province in 2022 (grant no. LJKMZ20221337), and the Joint

Project of Shenyang Science and Technology Bureau (grant no.

21-174-9-13).

|

1

|

Magalhães JE and Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA:

Migraine and cerebrovascular diseases: Epidemiology,

pathophysiological, and clinical considerations. Headache.

58:1277–1286. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zanon Zotin MC, Sveikata L, Viswanathan A

and Yilmaz P: Cerebral small vessel disease and vascular cognitive

impairment: From diagnosis to management. Curr Opin Neurol.

34:246–257. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gottesman RF and Seshadri S: Risk factors,

lifestyle behaviors, and vascular brain health. Stroke. 53:394–403.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nordestgaard LT, Christoffersen M and

Frikke-Schmidt R: Shared risk factors between dementia and

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 23:97772022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson

CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Beaton AZ, Boehme AK,

Buxton AE, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update:

A report from the American heart association. Circulation.

147:e93–e621. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hilkens NA, Casolla B, Leung TW and de

Leeuw FE: Stroke. Lancet. 403:2820–2836. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Goldsborough E III, Osuji N and Blaha MJ:

Assessment of cardiovascular disease risk: A 2022 update.

Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 51:483–509. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang Z, Ma L, Liu M, Fan J and Hu S:

Summary of the 2022 report on cardiovascular health and diseases in

China. Chin Med J (Engl). 136:2899–2908. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang H, Zhang H and Zou Z: Changing

profiles of cardiovascular disease and risk factors in China: A

secondary analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Chin Med J (Engl). 136:2431–2441. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang W, Liu Y, Liu J, Yin P, Wang L, Qi J,

You J, Lin L, Meng S, Wang F, et al: Mortality and years of life

lost of cardiovascular diseases in China, 2005-2020: Empirical

evidence from national mortality surveillance system. Int J

Cardiol. 340:105–112. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yun CW and Lee SH: Enhancement of

functionality and therapeutic efficacy of Cell-based therapy using

mesenchymal stem cells for cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci.

20:9822019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Biasiolo M, Sales G, Lionetti M, Agnelli

L, Todoerti K, Bisognin A, Coppe A, Romualdi C, Neri A and

Bortoluzzi S: Impact of host genes and strand selection on miRNA

and miRNA* expression. PLoS One. 6:e238542011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Due H, Svendsen P, Bødker JS, Schmitz A,

Bøgsted M, Johnsen HE, El-Galaly TC, Roug AS and Dybkær K: miR-155

as a biomarker in B-cell malignancies. Biomed Res Int.

2016:95130372016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen L, Gao D, Shao Z, Zheng Q and Yu Q:

miR-155 indicates the fate of CD4+ T cells. Immunol Lett.

224:40–49. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang X, Zeng X, Shu J, Bao H and Liu X:

MiR-155 enhances phagocytosis of alveolar macrophages through the

mTORC2/RhoA pathway. Medicine (Baltimore). 102:e345922023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tili E, Croce CM and Michaille JJ:

miR-155: On the crosstalk between inflammation and cancer. Int Rev

Immunol. 28:264–284. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Suofu Y, Wang X, He Y, Li F, Zhang Y,

Carlisle DL and Friedlander RM: Mir-155 knockout protects against

Ischemia/reperfusion-induced brain injury and hemorrhagic

transformation. Neuroreport. 31:235–239. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wu L, Pu L and Zhuang Z: miR-155-5p/FOXO3a

promotes pulmonary fibrosis in rats by mediating NLRP3 inflammasome

activation. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 45:257–267. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cao RY, Li Q, Miao Y, Zhang Y, Yuan W, Fan

L, Liu G, Mi Q and Yang J: The emerging role of MicroRNA-155 in

cardiovascular diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2016:98692082016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen JG, Xu XM, Ji H and Sun B: Inhibiting

miR-155 protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via

targeted regulation of HIF-1α in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci.

22:1050–1058. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Guo J, Liu HB, Sun C, Yan XQ, Hu J, Yu J,

Yuan Y and Du ZM: MicroRNA-155 promotes myocardial

infarction-induced apoptosis by targeting RNA-Binding protein QKI.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:45798062019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen W, Wang L and Liu Z: MicroRNA-155

influences cell damage in ischemic stroke via TLR4/MYD88 signaling

pathway. Bioengineered. 12:2449–2458. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Bai B, Ji Z, Wang F, Qin C, Zhou H, Li D

and Wu Y: CTRP12 ameliorates post-myocardial infarction heart

failure through down-regulation of cardiac apoptosis, oxidative

stress and inflammation by influencing the TAK1-p38 MAPK/JNK

pathway. Inflamm Res. 72:1375–1390. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang Z, Liang K, Zou G, Chen X, Shi S,

Wang G, Zhang K, Li K and Zhai S: Inhibition of miR-155 attenuates

abdominal aortic aneurysm in mice by regulating macrophage-mediated

inflammation. Biosci Rep. 38:BSR201714322018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wu XY, Fan WD, Fang R and Wu GF:

Regulation of microRNA-155 in endothelial inflammation by targeting

nuclear factor (NF)-κB P65. J Cell Biochem. 115:1928–1936.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Park M, Choi S, Kim S, Kim J, Lee DK, Park

W, Kim T, Jung J, Hwang JY, Won MH, et al: NF-κB-responsive miR-155

induces functional impairment of vascular smooth muscle cells by

downregulating soluble guanylyl cyclase. Exp Mol Med. 51:1–12.

2019.

|

|

27

|

Pena-Philippides JC, Caballero-Garrido E,

Lordkipanidze T and Roitbak T: In vivo inhibition of miR-155

significantly alters post-stroke inflammatory response. J

Neuroinflammation. 13:2872016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang X, Han W, Zhang Y, Zong Y, Tan N,

Zhang Y, Li L, Liu C and Liu L: Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor

t-AUCB ameliorates vascular endothelial dysfunction by influencing

the NF-κB/miR-155-5p/eNOS/NO/IκB Cycle in hypertensive rats.

Antioxidants (Basel). 11:13722022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Faccini J, Ruidavets JB, Cordelier P,

Martins F, Maoret JJ, Bongard V, Ferrières J, Roncalli J, Elbaz M

and Vindis C: Circulating miR-155, miR-145 and let-7c as diagnostic

biomarkers of the coronary artery disease. Sci Rep. 7:429162017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Huang YQ, Huang C, Zhang B and Feng YQ:

Association of circulating miR-155 expression level and

inflammatory markers with white coat hypertension. J Hum Hypertens.

34:397–403. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang H, Chen G, Qiu W, Pan Q, Chen Y,

Chen Y and Ma X: Plasma endothelial microvesicles and their

carrying miRNA-155 serve as biomarkers for ischemic stroke. J

Neurosci Res. 98:2290–2301. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jin ZQ: MicroRNA targets and biomarker

validation for diabetes-associated cardiac fibrosis. Pharmacol Res.

174:1059412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sun G, Yan J, Noltner K, Feng J, Li H,

Sarkis DA, Sommer SS and Rossi JJ: SNPs in human miRNA genes affect

biogenesis and function. RNA. 15:1640–1651. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tam W: Identification and characterization

of human BIC, a gene on chromosome 21 that encodes a noncoding RNA.

Gene. 274:157–167. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li C, He H, Zhu M, Zhao S and Li X:

Molecular characterisation of porcine miR-155 and its regulatory

roles in the TLR3/TLR4 pathways. Dev Comp Immunol. 39:110–116.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren

MV, Couttet P, Soond DR, van Dongen S, Grocock RJ, Das PP, Miska

EA, et al: Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune

function. Science. 316:608–611. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ruggiero T, Trabucchi M, De Santa F, Zupo

S, Harfe BD, McManus MT, Rosenfeld MG, Briata P and Gherzi R: LPS

induces KH-type splicing regulatory protein-dependent processing of

microRNA-155 precursors in macrophages. FASEB J. 23:2898–2908.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

O'Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng

G and Baltimore D: MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage

inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:1604–1609. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Guo Q, Zhang H, Zhang B, Zhang E and Wu Y:

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) enhances miR-155-Mediated

endothelial senescence by targeting sirtuin1 (SIRT1). Med Sci

Monit. 25:8820–8835. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu Y, Guo G, Zhong Z, Sun L, Liao L, Wang

X, Cao Q and Chen H: Long non-coding RNA FLVCR1-AS1 sponges miR-155

to promote the tumorigenesis of gastric cancer by targeting c-Myc.

Am J Transl Res. 11:793–805. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Huang RS, Hu GQ, Lin B, Lin ZY and Sun CC:

MicroRNA-155 silencing enhances inflammatory response and lipid

uptake in oxidized Low-density Lipoprotein-stimulated human THP-1

macrophages. J Investig Med. 58:961–967. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Caballero-Garrido E, Pena-Philippides JC,

Lordkipanidze T, Bragin D, Yang Y, Erhardt EB and Roitbak T: In

Vivo inhibition of miR-155 promotes recovery after experimental

mouse stroke. J Neurosci. 35:12446–12464. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bruen R, Fitzsimons S and Belton O:

miR-155 in the resolution of atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol.

10:4632019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Uva P, Da Sacco L, Del Cornò M,

Baldassarre A, Sestili P, Orsini M, Palma A, Gessani S and Masotti

A: Rat mir-155 generated from the lncRNA Bic is 'hidden' in the

alternate genomic assembly and reveals the existence of novel

mammalian miRNAs and clusters. RNA. 19:365–379. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Thai TH, Calado DP, Casola S, Ansel KM,

Xiao C, Xue Y, Murphy A, Frendewey D, Valenzuela D, Kutok JL, et

al: Regulation of the germinal center response by microRNA-155.

Science. 316:604–608. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Schliesser MG, Claus R, Hielscher T, Grimm

C, Weichenhan D, Blaes J, Wiestler B, Hau P, Schramm J, Sahm F, et

al: Prognostic relevance of miRNA-155 methylation in anaplastic

glioma. Oncotarget. 7:82028–82045. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Heo I, Joo C, Cho J, Ha M, Han J and Kim

VN: Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor

MicroRNA. Mol Cell. 32:276–284. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lu C, Chen B, Chen C, Li H, Wang D, Tan Y

and Weng H: CircNr1h4 regulates the pathological process of renal

injury in salt-sensitive hypertensive mice by targeting miR-155-5p.

J Cell Mol Med. 24:1700–1712. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Pasca S, Jurj A, Petrushev B, Tomuleasa C

and Matei D: MicroRNA-155 implication in M1 polarization and the

impact in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 11:6252020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang J, Cheng C, Yuan X, He JT, Pan QH

and Sun FY: microRNA-155 acts as an oncogene by targeting the tumor

protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1 in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7:602–610. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Li Y, Zhang L, Dong Z, Xu H, Yan L, Wang

W, Yang Q and Chen C: MicroRNA-155-5p promotes tumor progression

and contributes to paclitaxel resistance via TP53INP1 in human

breast cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 220:1534052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Xiao L, Li X, Mu Z, Zhou J, Zhou P, Xie C

and Jiang S: FTO inhibition enhances the antitumor effect of

temozolomide by targeting MYC-miR-155/23a Cluster-MXI1 feedback

circuit in glioma. Cancer Res. 80:3945–3958. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Costinean S, Zanesi N, Pekarsky Y, Tili E,

Volinia S, Heerema N and Croce CM: Pre-B cell proliferation and

lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155

transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:7024–7029. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Nazari-Jahantigh M, Wei Y, Noels H, Akhtar

S, Zhou Z, Koenen RR, Heyll K, Gremse F, Kiessling F, Grommes J, et

al: MicroRNA-155 promotes atherosclerosis by repressing Bcl6 in

macrophages. J Clin Invest. 122:4190–4202. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kurowska-Stolarska M, Alivernini S,

Ballantine LE, Asquith DL, Millar NL, Gilchrist DS, Reilly J, Ierna

M, Fraser AR, Stolarski B, et al: MicroRNA-155 as a proinflammatory

regulator in clinical and experimental arthritis. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 108:11193–11198. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang G, Chen JJ, Deng WY, Ren K, Yin SH

and Yu XH: CTRP12 ameliorates atherosclerosis by promoting

cholesterol efflux and inhibiting inflammatory response via the

miR-155-5p/LXRα pathway. Cell Death Dis. 12:2542021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Jing H, Liu L, Jia Y, Yao H and Ma F:

Overexpression of the long non-coding RNA Oprm1 alleviates

apoptosis from cerebral Ischemia-reperfusion injury through the

Oprm1/miR-155/GATA3 axis. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol.

47:2431–2439. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Xue H, Hua LM, Guo M and Luo JM: SHIP1 is

targeted by miR-155 in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Rep.

32:2253–2259. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Husain K, Villalobos-Ayala K, Laverde V,

Vazquez OA, Miller B, Kazim S, Blanck G, Hibbs ML, Krystal G,

Elhussin I, et al: Apigenin targets MicroRNA-155, enhances SHIP-1

expression, and augments anti-tumor responses in pancreatic cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 14:36132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Faraoni I, Antonetti FR, Cardone J and

Bonmassar E: miR-155 gene: A typical multifunctional microRNA.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1792:497–505. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Johansson J, Berg T, Kurzejamska E, Pang

MF, Tabor V, Jansson M, Roswall P, Pietras K, Sund M, Religa P, et

al: MiR-155-mediated loss of C/EBPβ shifts the TGF-β response from

growth inhibition to epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion

and metastasis in breast cancer. Oncogene. 32:5614–5624. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Jiang D and Aguiar RC: MicroRNA-155

controls RB phosphorylation in normal and malignant B lymphocytes

via the noncanonical TGF-β1/SMAD5 signaling module. Blood.

123:86–93. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

63

|

Li DP, Fan J, Wu YJ, Xie YF, Zha JM and

Zhou XM: MiR-155 up-regulated by TGF-β promotes

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion and metastasis of human

hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. Am J Transl Res.

9:2956–2965. 2017.

|

|

64

|

Ke F, Wang H, Geng J, Jing X, Fang F, Fang

C and Zhang BH: MiR-155 promotes inflammation and apoptosis via

targeting SIRT1 in hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Exp Neurol.

362:1143172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhai Y, Liu B, Wu L, Zou M, Mei X and Mo

X: Pachymic acid prevents neuronal cell damage induced by

hypoxia/reoxygenation via miR-155/NRF2/HO-1 axis. Acta Neurobiol

Exp (Wars). 82:197–206. 2022.

|

|

66

|

Zhang W, Wang L, Wang R, Duan Z and Wang

H: A blockade of microRNA-155 signal pathway has a beneficial

effect on neural injury after intracerebral haemorrhage via

reduction in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Arch Physiol

Biochem. 128:1235–1241. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Sun L, Ji S and Xing J: Inhibition of

microRNA-155 alleviates neurological dysfunction following

transient global ischemia and contribution of neuroinflammation and

oxidative stress in the hippocampus. Curr Pharm Des. 25:4310–4317.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Yang J, Si D, Zhao Y, He C and Yang P:

S-amlodipine improves endothelial dysfunction via the

RANK/RANKL/OPG system by regulating microRNA-155 in hypertension.

Biomed Pharmacother. 114:1087992019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhu Y, Xian X, Wang Z, Bi Y, Chen Q, Han

X, Tang D and Chen R: Research progress on the relationship between

atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biomolecules. 8:802018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zheng B, Yin WN, Suzuki T, Zhang XH, Zhang

Y, Song LL, Jin LS, Zhan H, Zhang H, Li JS and Wen JK:

Exosome-Mediated miR-155 transfer from smooth muscle cells to

endothelial cells induces endothelial injury and promotes

atherosclerosis. Mol Ther. 25:1279–1294. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

González-López P, Ares-Carral C,

López-Pastor AR, Infante-Menéndez J, González Illaness T, Vega de

Ceniga M, Esparza L, Beneit N, Martín-Ventura JL, Escribano Ó and

Gómez-Hernández A: Implication of miR-155-5p and miR-143-3p in the

vascular insulin resistance and instability of human and

experimental atherosclerotic plaque. Int J Mol Sci. 23:102532022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Gimbrone MA Jr and García-Cardeña G:

Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of

atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 118:620–636. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Ota H, Eto M, Ogawa S, Iijima K, Akishita

M and Ouchi Y: SIRT1/eNOS axis as a potential target against

vascular senescence, dysfunction and atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler

Thromb. 17:431–435. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Hong FF, Liang XY, Liu W, Lv S, He SJ,

Kuang HB and Yang SL: Roles of eNOS in atherosclerosis treatment.

Inflamm Res. 68:429–441. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Sun HX, Zeng DY, Li RT, Pang RP, Yang H,

Hu YL, Zhang Q, Jiang Y, Huang LY, Tang YB, et al: Essential role

of microRNA-155 in regulating Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation