As a crucial trace element in the human body, copper

serves an essential role in human pathophysiology. Copper is not

only involved in hemoglobin synthesis, supporting the immune system

and neurotransmitter biosynthesis, but also has powerful

antioxidant properties, as well as being involved in the formation

of bone and connective tissue (1). These physiological functions render

copper vital for disease prevention and the maintenance of health.

Copper exhibits dose-dependent dual effects on the cardiovascular

system: i) Copper prevents cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) through

antioxidant effects, protecting endothelial function and

maintaining vascular connective tissue structure (2); ii) however, in CVDs, copper

overload interferes with lipid metabolism, and leads to oxidative

stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and endothelial cell dysfunction

(3). Therefore, maintaining an

appropriate intake of copper is essential to protect the heart and

blood vessels.

In recent years, the discovery of cuproptosis, a

newly identified form of copper-induced cell death, has provided

novel perspectives for resolving the molecular associations between

copper dyshomeostasis and CVDs. Tsvetkov et al (4) revealed that treatment of human cell

lines (such as the lung carcinoma line A549 and the immortalized

kidney line 293T) with the copper ionophore elesclomol induced cell

death and that pharmacologically inhibiting all other known cell

death pathways failed to inhibit elesclomol-induced cell death;

this novel form of cell death was named cuproptosis. Furthermore,

it has been demonstrated that copper ions can induce aberrant

aggregation by targeting mitochondrial lipoylated proteins and,

alongside the loss of iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, trigger

uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, ultimately leading to the

collapse of cellular energy metabolism (4). Bioinformatics studies have revealed

the extensive involvement of cuproptosis in the progression of CVDs

(5-7).

The present review aimed to elucidate the dynamic

balance of copper absorption-transportation-storage-excretion in

the human body, and to outline the mechanism underlying the

regulation of cuproptosis. Furthermore, the review summarizes the

molecular pathways linking copper to CVDs, including

atherosclerosis (AS) and heart failure (HF), and critically

appraises the roles of copper chelators [such as tetrathiomolybdate

(TTM) and triethylenetetramine (TETA)], copper ionophores

(including elesclomol) and therapeutics developed based on

cuproptosis in the treatment of CVDs, according to the progress of

current research. The aim was to clarify the causal relationship

between copper and CVD, and to inform the development of prevention

and treatment strategies based on precise regulation of copper

homeostasis.

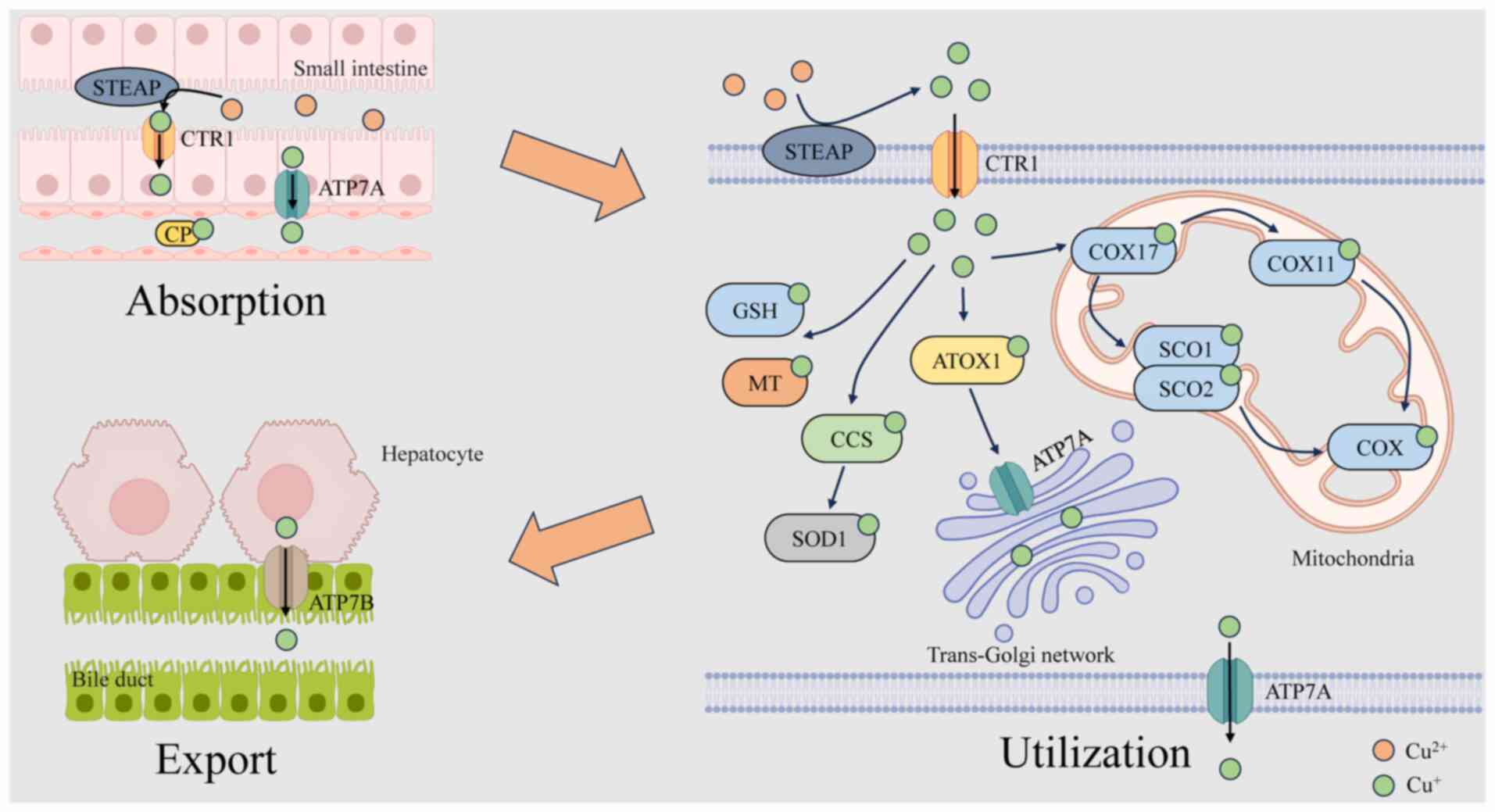

Copper metabolism encompasses the absorption,

distribution, storage, utilization and excretion of copper. These

processes are essential for maintaining copper homeostasis, thereby

supporting the physiological functions of copper. As shown in

Fig. 1, copper metabolism

involves multiple organs and systems, primarily including

intestinal absorption, hepatic storage and release, and excretion

through bile and urine. Abnormalities in any of these processes can

result in disturbances in copper metabolism, thereby affecting

health.

In the cytoplasm, the transportation of copper is

precisely regulated by a network of high-affinity copper chaperones

(16). Copper enters the cell

and forms complexes with reduced glutathione (GSH), metallothionein

(MT), ATOX1 and copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS)

(11,18). ATOX1, which is conserved across

species, acquires Cu+ from CTR1 through its classical

metal-binding site (19) and

subsequently transports Cu+ via ATP7A and

copper-transporting ATPase β (ATP7B) to the trans-Golgi network

(TGN) for the synthesis of tyrosinase, lysyl oxidase and

ceruloplasmin (CP), thereby sustaining copper homeostasis inside

the cell (20-23). CCS, a copper chaperone protein,

facilitates the transport of Cu to certain proteins, including

superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), located in the cytoplasm and

mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS), thereby neutralizing

mitochondria-derived superoxide radicals (24,25). Cellular copper levels inversely

regulate CCS expression (26).

Moreover, CCS modulates the localization of SOD1 between the IMS

and cytosol in an oxygen-dependent manner, preserving the stability

of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in vivo, thereby preventing

oxidative damage caused by copper overload (27). In addition, CCS facilitates the

transport of Cu+ to mitogen-activated protein kinase 1,

hence modulating its activity and influencing cellular

proliferation (28). The

delivery of Cu+ to mitochondria primarily relies on the

cytochrome c oxidase (COX) copper chaperone 17 (COX17), which

facilitates copper transport into the IMS for COX synthesis.

Additionally, the literature has indicated that copper can be

transported to mitochondria through a non-proteinaceous anionic

ligand (CuL) (29). COX

comprises two core subunits, COX1 and COX2, which bind copper at

the conserved CuB and CuA sites, respectively

(16,30). Within the IMS, COX17 transfers

Cu+ to synthesis of COX (SCO)1 and SCO2 for the assembly

of COX subunits. Cu+ is subsequently conveyed to COX2,

contributing to its structure; alternatively, it is transported by

COX17 to the COX copper chaperone 11 (COX11) and then to COX1 for

use in its assembly (12,31).

The liver serves as the main organ responsible for

copper metabolism and storage within the human body. Upon reaching

the liver, copper in the bloodstream is delivered to designated

structures by copper chaperone proteins, including ATOX1, CCS and

COX17. Excess copper is sequestered by MT and GSH for hepatic

storage, thereby preventing cytotoxicity (16,32).

Biliary excretion represents the principal pathway

for hepatic copper elimination. ATP7A and ATP7B are the primary

transporters of Cu+ within cells. Their regulatory roles

in copper absorption and excretion depend largely on their

subcellular localization (33,34). Under physiological copper

concentrations, these ATPases predominantly localize to the TGN,

where they transfer Cu+ into the TGN lumen (23). When intracellular copper rises,

these transporters relocalize from the TGN to vesicular

compartments, subsequently fusing with the plasma membrane to

facilitate Cu+ export. Once homeostatic copper levels

are restored, the transporters are recycled back to the TGN

(35). ATP7A is widely expressed

in most tissues and organs, excluding the liver, whereas ATP7B is

primarily expressed in the liver (23). After being absorbed by the

intestinal epithelium, copper is released into the bloodstream by

ATP7A and thereafter enters the portal circulation, where it is

absorbed by hepatocytes. It is then pumped into the TGN by ATP7B

and delivered to the plasma membrane to form CP, and then secreted

into the bloodstream through exocytosis. In cases of excessive

copper accumulation, ATP7B is relocated from the TGN to the

canalicular membrane of hepatocytes, facilitating the excretion of

surplus copper from the cytoplasm into the bile and ultimately out

of the body. Copper excreted into bile forms complexes with bile

salts, preventing its intestinal reabsorption (34,36). Copper homeostasis in the body is

maintained through absorption in the duodenum and small intestine,

as well as excretion via the biliary system (37,38).

Copper homeostasis refers to the tightly regulated

balance among copper absorption, transport, storage and excretion

(39). It is crucial for

appropriate physiological processes, as it participates in enzyme

activity, cellular respiration, iron metabolism, and the

development and maintenance of nervous system function. Copper

dyshomeostasis can result in oxidative stress, cellular damage and

even illness, such as Wilson disease (caused by ATP7B mutations

leading to copper accumulation) and Menkes disease (due to ATP7A

deficiency causing systemic copper deficiency). An imbalance in

copper homeostasis is a well-established clinical characteristic of

these inherited disorders. Moreover, copper levels can serve as a

predictive indicator for certain conditions; for example, elevated

copper levels are associated with advanced stage and poor prognosis

in prostate, bladder and renal cancers (11).

Copper homeostasis, largely governed by the

transporters ATP7A and ATP7B, is essential for human health.

Dysfunction of these two transporters may result in severe

illnesses. Menkes disease (MD) results from mutations in the ATP7A

gene. The dysfunction of ATP7A in intestinal epithelial cells

results in copper accumulation inside these cells and a reduced

transfer of copper into the bloodstream, culminating in a notable

systemic copper deficit. Patients present with characteristic

clinical features, such as intellectual disability, hypothermia,

neuronal degeneration, bone fractures, and anomalies of the hair,

skin and vasculature (16).

Wilson's disease (WD) results from mutations in the ATP7B gene.

Impaired ATP7B function hinders the efficient elimination of

Cu+ from cells, causing persistent copper accumulation

in the liver, brain and other tissues, which results in copper

toxicity and organ damage in patients. Patients may present with

hepatic manifestations, including acute liver failure, jaundice and

chronic hepatitis, as well as neurological conditions, such as

tremors, Parkinsonism, ataxia, dystonia, dysarthria, spasticity and

a lack of motor coordination (16).

Copper dyshomeostasis is closely associated with the

development and progression of numerous diseases. Emerging evidence

has suggested that copper dyshomeostasis contributes to the

pathogenesis of coronary heart disease. Furthermore, copper

deficiency may result in myocardial diastolic dysfunction and a

diminished β-adrenergic response, and can lead to HF. By contrast,

copper overload disrupts the mitochondrial electron transport chain

(mtETC), which contributes to HF by impairing the antioxidant

defense, ROS accumulation and activation of ischemic/hypoxic

signaling pathways via CP (40).

Copper overload may result in vascular dysfunction by elevating

nitric oxide generation and endothelial oxidative stress (41). Copper dyshomeostasis in

neurological illnesses is associated with the etiology of

Alzheimer's disease. Copper can facilitate the aggregation of

amyloid-β peptides and induce neurotoxicity (16). Abnormal alterations in copper

levels, specifically elevated serum copper and increased urinary

copper excretion, have been observed in patients with diabetic

nephropathy (42). In addition,

cancer cells have a markedly higher demand for copper compared with

normal cells (43); notably,

copper levels in tumor tissue and/or serum are significantly

elevated in patients with various types of cancer, including

prostate, bladder and renal cell carcinoma, compared with in

healthy controls, and are associated with tumor growth and

progression (39). Furthermore,

copper can promote cancer metastasis by activating enzymes, such as

lysyl oxidase, and signaling pathways, including MEK-ERK, both of

which drive tumor invasion and dissemination (16). These findings provide new

insights into the diagnosis and management of disorders associated

with copper homeostasis.

As research advances on copper dysregulation and

associated diseases, an increasing number of pharmaceuticals are

being identified and utilized. In instances of severe systemic

copper deficiency in patients with MD, Cu-histidine may be injected

into the blood to circumvent intestinal absorption, facilitating

the distribution of Cu2+ to various tissues and organs,

thereby aiding in restoring systemic copper levels in affected

individuals. Conversely, to mitigate the continuous copper

accumulation in the brain, liver and other tissues of individuals

with WD, oral zinc may be employed to decrease copper absorption,

while copper chelators such as D-penicillamine and TTM can be

utilized to lower copper levels in the body. Free α-lipoic acid

(α-LA) is a cuproptosis enhancer; however, it has been shown that

α-LA can mitigate cytotoxicity caused by copper overload through

chelation and improve the copper-induced oxidative stress

environment (44).

Serum and tumor tissue copper levels in patients

with cancer are notably higher than those in healthy individuals,

and copper serves a crucial role in tumor angiogenesis (45). Consequently, the accumulation of

copper in tumor tissue may serve as a target for the formulation of

anticancer agents. Two main methods exist for triggering apoptosis

through copper targeting. The first strategy involves employing

copper chelators, such as D-penicillamine and TTM, to bind Cu

directly, hence diminishing its bioavailability, which may inhibit

tumor proliferation in both cellular and animal tumor models

(46). Copper chelators may

inhibit collagen fiber cross-linking by blocking the

copper-dependent lysyl oxidase family, therefore preventing renal

fibrosis (47,48). Notably, copper chelators also

exhibit anti-metastatic effects, primarily by inhibiting the

recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), which are

essential for angiogenesis and the establishment of metastatic

niches (49). Copper chelators

are also used to treat Alzheimer's disease, amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis and Huntington's disease (16). The alternative approach involves

elevating intracellular copper levels through the use of copper

ionophores, such as disulfiram (DSF), to generate ROS, inhibit

proteasomes and trigger apoptosis (50). Nonetheless, some studies have

suggested that copper ionophores eliminate cancer cells by a

distinct process rather than through apoptosis, necrosis or

oxidative stress (46,51,52). Furthermore, cuprous oxide

nanoparticles can destabilize the copper chaperones ATOX1 and CCS,

consequently producing an anticancer impact (11).

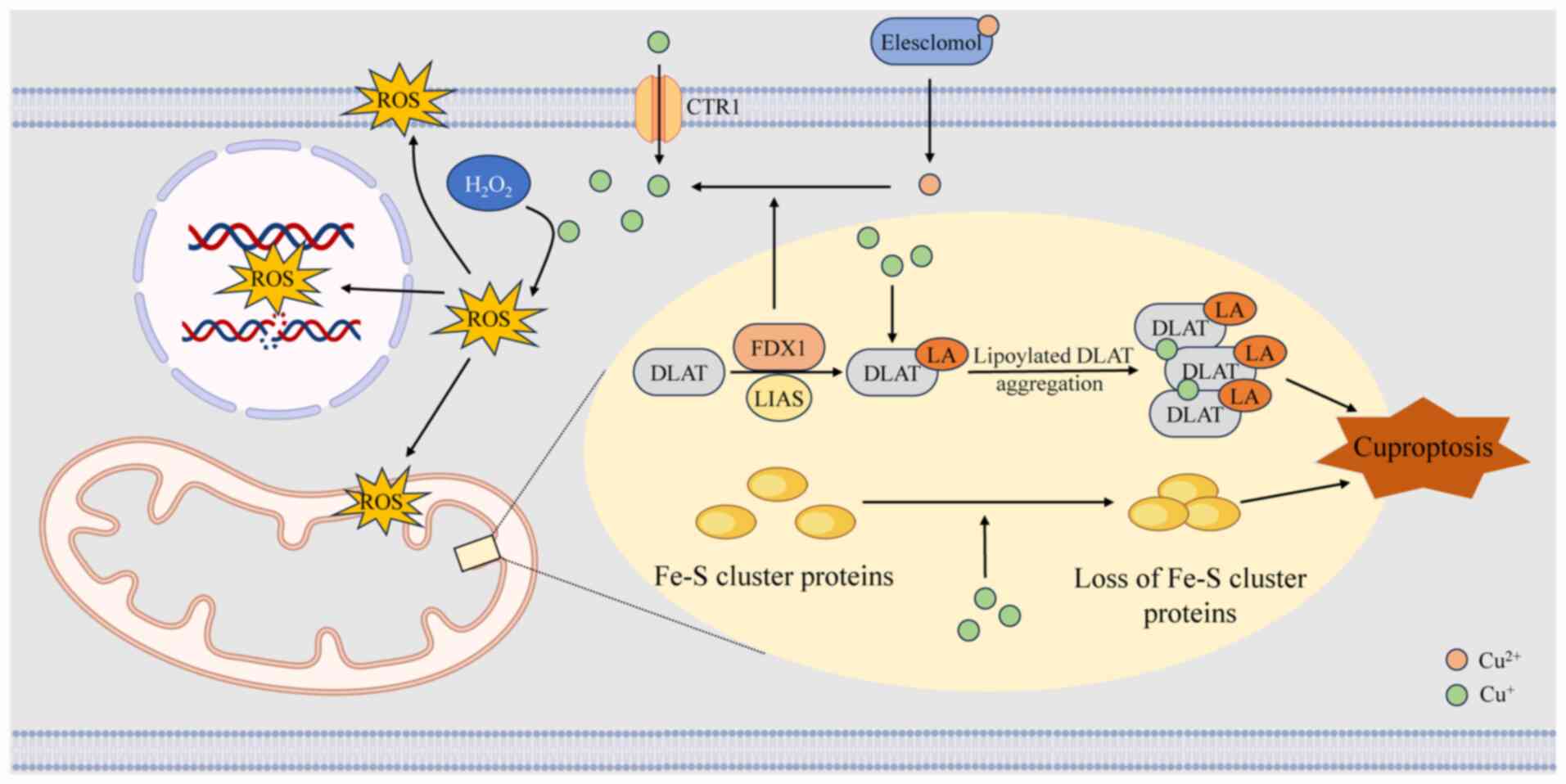

In cells treated with the copper ionophore

elesclomol, the levels of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

intermediates increase over time, highlighting a robust association

between cuproptosis and mitochondrial metabolism. In mitochondria,

ferredoxin 1 directly binds to lipoic acid synthetase, promoting

the post-translational lipoylation of dihydrolipoamide

S-acetyltransferase (DLAT), a key E2 subunit of the pyruvate

dehydrogenase complex. This lipoylation is essential for the

structural integrity and enzymatic activity of DLAT within the TCA

cycle (54,55). It subsequently facilitates the

dissociation of Cu2+ from elesclomol, and reduces

Cu2+ to Cu+ (56). Cu+ exhibits a high

affinity for the disulfide pentane ring structure within the lipoyl

group (57). When excess

Cu+ binds to lipoylated proteins such as DLAT, it

disrupts their native conformational stability, inducing abnormal

cross-linking and irreversible aggregation in these enzymes that

should normally assemble in an ordered, polymeric form. The

resulting protein aggregation leads to inactivation of the pyruvate

dehydrogenase complex, suppressing acetyl-CoA and α-ketoglutarate

oxidation, and causing a sharp decline in ATP synthesis.

Additionally, copper can replace iron in Fe-S clusters or disrupt

their synthesis, leading to the inactivation of Fe-S-dependent

enzymes, and further disturbing metabolic and redox balance. These

events collectively trigger protein toxicity stress, ultimately

resulting in cell death (4).

Drug inhibition of the electron transport chain and pyruvate uptake

can reverse elesclomol-induced cell death, providing compelling

evidence for this process (4).

Furthermore, excessive copper promotes ROS formation via the Fenton

reaction, damages mitochondrial and plasma membranes, disrupts DNA

integrity and broadly impairs cellular functions (58). The process of cuproptosis is

illustrated in Fig. 2.

Cuproptosis and ferroptosis are two metal

ion-dependent modes of regulated cell death that have attracted

considerable attention, particularly in cancer research. Although

their mechanisms are distinct, ferroptosis being driven by

iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, the two processes are

metabolically interconnected.

During cuproptosis, degradation of Fe-S clusters

releases free iron ions, which elevate intracellular oxidative

stress and can subsequently promote ferroptosis. Conversely, during

ferroptosis, depletion of GSH and mitochondrial injury compromise

cellular copper chelation and export, resulting in copper

accumulation and the induction of cuproptosis. This

self-reinforcing feedback loop between copper and iron metabolism

has been exploited in several nanotherapeutic approaches to enhance

anticancer efficacy (59-61).

Copper participates in the Fenton reaction,

continuously generating hydroxyl radicals during the transformation

of Cu2+ to Cu+. This potent oxidant can

directly induce DNA strand breakage and base oxidation (62). Excessive copper-induced systemic

oxidative stress can disrupt lipid metabolic balance and facilitate

lipid accumulation in the intima of vessels; this mechanism

markedly propels the progression of AS (3). Copper-induced oxidative stress also

increases the oxidation of GSH (63). Experimental evidence clarifying

the toxic mechanism of copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) has

been demonstrated through studies involving animal models and

cellular experiments. These studies have revealed that CuO NPs

induce oxidative stress in a stepwise manner, encompassing ROS

burst, compensatory upregulation of heme oxygenase-1, mtETC

dysfunction, and aberrant secretion of proinflammatory and

profibrogenic cytokines (64,65). The copper chelator TTM can

markedly alleviate cardiovascular damage associated with CuO NPs by

chelating excess Cu (66). This

multilayered oxidative damage represents a key pathophysiological

mechanism in copper-related CVD.

Mitochondria serve as the energy-producing

organelles in eukaryotic cells and regulate cellular metabolic

activities, including oxidative phosphorylation. Cuproenzymes in

mitochondria are essential to this process. COX, the major

mitochondrial cuproenzyme, utilizes most of the mitochondrial

copper pool, accounting for 20-25% of the total copper content of

the cell. Another important cuproenzyme, SOD1, is situated in the

IMS of the mitochondria and its primary role is to facilitate the

breakdown of superoxide generated by the mitochondrial respiratory

chain (29). Copper deficiency

impairs the delivery of Cu to SCO1/SCO2 and COX11 through COX17,

which in turn reduces the synthesis of COX. Copper deficiency can

also induce the production of the peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor-γ coactivator-1α protein, thereby altering mitochondrial

ultrastructure, and leading to abnormal mitochondrial proliferation

and dysfunction. This series of changes is closely associated with

myocardial dysfunction (3).

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) functions as a

crucial transcription factor in the regulation of angiogenesis

(3). Copper can regulate the

HIF-1 signaling pathway in multiple ways. Copper can enhance the

stability of HIF-1α in the nucleus under normoxic conditions,

causing the expression of HIF-1-dependent genes (67). CCS mediates the effect of copper

on HIF-1 activity (68).

Furthermore, copper-dependent lysyl oxidases are

vital for maintaining the structural integrity of blood vessel

walls by catalyzing the covalent cross-linking of elastin and

collagen, which confer tensile strength and elasticity to

connective tissues (69).

Abnormal lysyl oxidase expression levels or enzyme activity are

associated with pathological processes such as CVD. Under copper

deficiency, reduced lysyl oxidase synthesis and activity cause

abnormal collagen degradation, which may cause serious

complications such as destruction of the vascular matrix and

rupture of the intima (3,69).

AS is a chronic cardiovascular disorder

characterized by the progressive formation of atherosclerotic

plaques, leading to luminal narrowing and impaired vascular

function. Accumulation of the oxidized form of low-density

lipoprotein (LDL) in cells in the subendothelial space is a key

factor in AS formation (70). In

parallel, in silico screening has demonstrated that natural

compounds derived from Chlorella vulgaris and

Boesenbergia rotunda possess the potential to inhibit key

early steps of AS, such as foam cell formation, by targeting

proteins such as cholesteryl ester transfer protein, lectin-like

oxidized LDL receptor-1, CD36 and acyl-CoA:cholesterol

acyltransferase 1 (71,72). Separately, accumulating evidence

has implicated copper dyshomeostasis in AS pathogenesis, with

increased levels of copper being strongly linked to AS (73) and blood copper levels positively

linked with subclinical carotid plaques (74). Furthermore, increased urinary

levels of copper have been reported to be associated with a

heightened 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD (75). Copper-related DNA methylation

alterations are also associated with an elevated risk of acute

coronary syndrome, potentially resulting from aberrant lipid

metabolism and inflammation (76), which are associated with

copper-mediated ROS formation, elevated CP, expansion of arterial

endocardium and narrowing of the arterial lumen (40).

Currently, stroke ranks as the second most common

cause of death worldwide, following ischemic heart disease. Stroke

disrupts cerebral perfusion, leading to ischemic brain injury and

subsequent neurological impairment (84). A large case-control study in the

USA indicated that elevated dietary copper consumption was

associated with a reduced risk of stroke (84). However, dietary copper intake

does not necessarily reflect systemic or circulating copper levels,

which complicates the interpretation of these findings. Several

studies have shown that while plasma copper levels are not notably

associated with the first hemorrhagic stroke, there is a positive

association between plasma copper levels and the risk of the first

ischemic stroke (85,86). A case-control study further

reported that elevated plasma copper, along with certain trace

metals such as molybdenum and titanium, was associated with higher

ischemic stroke risk (87).

Similarly, multiple meta-analyses have revealed a favorable

association between elevated circulating copper levels and stroke

incidence (88,89). This apparent contradiction may be

explained by the marked elevation of serum non-CP-bound copper

observed in patients with acute ischemic stroke. As free copper

unbound to CP, it exhibits strong pro-oxidant properties. The

increase in blood copper during the acute stroke phase may also

partially stem from a stress response, meaning elevated blood

copper serves both as a risk factor and potentially as a

pathological consequence. Collectively, the impact of copper

appears to be context-dependent, varying with inflammatory status

and disease stage, and may follow a non-linear dose-response

relationship.

The precise biological pathway by which copper

impacts stroke remains unidentified. Notably, copper contributes to

the synthesis of SOD, which mitigates ROS generated by ischemic

stroke and diminishes cellular damage following such events

(90). Conversely, copper can

exacerbate ischemic stroke. EPCs can improve endothelial function

and promote angiogenesis in ischemic brain tissue, whereas

thrombospondin-1 serves as a principal inhibitor of EPC activity.

Research findings have suggested that copper exposure in mice can

lead to elevated thrombospondin-1 levels, hence exacerbating

ischemic stroke in these subjects (3). Copper may influence stroke risk

indirectly through its modulation of lipid metabolism, a hypothesis

that warrants confirmation in prospective cohort studies (91).

I/R injury refers to tissue damage caused by the

restoration of blood flow after a period of ischemia, primarily

driven by oxidative stress (92). This process generates excessive

ROS and provokes a robust inflammatory response, a major pathogenic

mechanism underlying various diseases, such as acute kidney injury,

particularly in the context of kidney transplantation (93). Following I/R-induced myocardial

infarction (MI), substantial remodeling of the extracellular matrix

(ECM) occurs, leading to interstitial fibrosis, scarring and

cardiac dysfunction. The increased copper-dependent lysyl oxidase

subtype following MI may facilitate cardiac ECM remodeling and

dysfunction (40).

The copper-dependent enzyme Cu/Zn-SOD mitigates

oxidative stress-induced cellular edema during reperfusion

(94). When Cu/Zn-SOD is

upregulated in coronary vascular cells, the heart becomes more

resistant to I/R injury (95,96). A meta-analysis showed that

regular exercise can elevate levels of GSH peroxidase and

Cu/Zn-SOD, and enhance cardiac function after myocardial I/R injury

(97). Nonetheless, the

mechanistic links between copper dyshomeostasis, cuproptosis and

myocardial I/R injury remain to be fully elucidated.

HF is prevalent among adults, and has high morbidity

and mortality rates worldwide. Both acute HF (AHF) and chronic HF

(CHF) is linked to heightened oxidative stress resulting from the

elevated generation of ROS and compromised clearance mechanisms

(98). Furthermore, the Cu:Zn

ratio is important in HF. A prospective study conducted in 2022

demonstrated that for every 1-unit increase in serum Cu:Zn ratio,

the risk of HF was increased by 63%, and this association exhibited

a linear dose-response relationship. Incorporating the Cu:Zn ratio

into traditional HF risk prediction models may improve risk

stratification efficacy (99).

However, the Cu:Zn ratio as a single biomarker may be driven by

confounding factors, such as inflammation, liver function or

inadequate zinc intake, and may not necessarily reflect a causal

relationship. In a study of 125 patients, serum copper levels were

elevated and serum zinc levels were decreased in patients with both

AHF and CHF (100). This has

been confirmed in several studies (99,101-103). Although elevated serum copper

is frequently observed in inflammatory states, it does not

necessarily indicate copper overload. Conversely, evidence

regarding the impact of copper deficiency or excess on HF remains

limited and inconsistent. Patients with ischemic and non-ischemic

HF showed differences in dietary zinc and copper intake, but the

median zinc and copper status biomarkers did not show a notable

difference between the two groups (104), suggesting that the serum Cu:Zn

ratio may be regulated by homeostasis during the chronic stable

phase of HF and thus lose the ability to distinguish between

ischemic and non-ischemic etiologies. A Mendelian randomization

investigation analysis also indicated that dietary copper was not

markedly associated with the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic

diseases (105). Although

observational studies have repeatedly reported elevated serum Cu:Zn

ratios in patients with HF (99,106,107), their clinical significance is

highly dependent on disease stage, inflammatory status and

zinc-copper balance. Single-cell transcriptome sequencing of immune

cells in epicardial adipose tissue from patients with HF has

revealed disturbed zinc and copper metabolism (108). Prior studies have also shown

that elevated blood copper levels in patients with HF are linked to

higher mortality and morbidity rates (99,100,109). Nonetheless, certain studies

have indicated that shortages in zinc and copper may elevate the

risk of coronary heart disease, valvular regurgitation, myocardial

lesions and myocardial hypertrophy (110). Supplementation with several

nutrients, including copper, may serve as a viable therapeutic

method for individuals with HF (111,112). Some experiments have even shown

that the serum copper levels of patients with CHF are similar to

those in a healthy control group (102). In summary, the current evidence

linking zinc and copper status to CVD remains fragmented and

inconsistent. Neither zinc nor copper levels should be used alone

for diagnosing HF or guiding supplementation therapy. Additional

research is needed to determine whether the detection of diseases

relies on the degree of association between zinc and copper content

and CVD (110).

Antioxidant mechanisms serve a regulatory role in HF

pathology. In end-stage HF, increased oxidative stress may

specifically upregulate catalase gene expression (113), while copper dyshomeostasis

exacerbates this pathological process. In a study involving

diabetes-induced HF, patients with diabetes had impaired cardiac

mitochondrial copper regulation, with reduced COX17, COX11, CCS and

SCO1 expression, and mitochondrial translocation in the myocardium,

thus affecting copper transport to the mitochondria and COX

assembly, resulting in a decrease in COX activity of ~27%. Notably,

TETA treatment could restore COX activity to normal, improving

cardiac function (114).

Non-pharmacological interventions also have regulatory potential.

In patients with CHF, 12 weeks of aerobic exercise training

(cycling at 50% of peak oxygen uptake for 45 min, four times/week)

has been shown to increase the expression of Cu/Zn-SOD and GSH

peroxidase, and thus improve cardiac function (115). A previous transcriptome

analysis has indicated that genes associated with cuproptosis

regulate the immunological microenvironment in ischemic HF

(116). However, the mechanism

of cuproptosis in HF is currently unclear.

Copper chelators are agents capable of binding

copper ions, thereby preventing their intracellular accumulation,

or depleting excessive copper to modulate redox homeostasis and

induce cell death (117). An

increasing body of preclinical and clinical evidence has suggested

that copper chelation therapy holds therapeutic potential in CVDs.

As shown in Table I (114,118-132), various copper chelators have

been evaluated in different animal models and patient

populations.

TTM exhibits a high affinity for copper and has the

ability to selectively bind to copper ions. Notably, it is

extensively employed in treating WD. In comparison to conventional

therapies, such as D-penicillamine and trientine, which increase

urinary copper excretion but may provoke paradoxical neurological

worsening, TTM may prevent copper-induced harm to the blood-brain

barrier and demonstrate an improved safety profile (133,134). TTM can specifically form a

TTM-copper-ATOX1 complex with ATOX1, thus obstructing copper

transport to the TGN and its subsequent synthesis of cuproprotein,

or diminishing copper bioavailability and vascular inflammation to

prevent AS in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (135). The second-generation TTM analog

(ATN-224; choline TTM) inhibits SOD1 within both tumor cells and

endothelial cells, thus decreasing endothelial cell proliferation

in vitro (136), and TTM

can reduce the proliferation of human pulmonary microvascular

endothelial cells (121).

Intravenous injection of ammonium TTM (ATTM) has been shown to

protect the heart in an MI-reperfusion model in a

drug-exposure-dependent manner (118). Notably, ATTM may function as an

inorganic sulfide-releasing molecule (119). Intervention with TTM has been

reported to markedly inhibit the aggregation of DLAT oligomers and

enhance ATP7A expression in the hearts of spontaneously

hypertensive rats, thereby diminishing cuproptosis and

mitochondrial damage (120).

TETA acts as a selective copper chelator and has a

bidirectional regulatory function in the cardiovascular system. In

copper-deficient myocardial hypertrophy model tissues, TETA can

serve as a copper chaperone to promote the transport of copper ions

to cardiomyocytes. Under copper overload conditions, excess copper

ions are removed by chelation (40). TETA may inhibit the rise in serum

copper levels and efficiently reduce the heightened CP activity

during MI (137). Abnormal ECM

Cu2+ accumulation and a defect in intracellular

Cu+ supply can lead to copper dyshomeostasis in the

myocardium. TETA can restore the balance of copper distribution in

the myocardium and effectively maintain the integrity of the heart

structure (127). In addition,

TETA has been reported to enhance myocardial function in the hearts

of diabetic rats by reinstating myocardial copper transport routes

(114,126), and it may serve as a possible

therapeutic agent for diabetic heart disease (125). However, neither TTM nor TETA

has been systematically evaluated in large-scale clinical trials or

meta-analyses.

EDTA can bind to a range of metals. The results of

the TACT randomized trial showed that individuals with type 1 and

type 2 diabetes who had previously suffered from MI experienced a

reduction in the recurrence of cardiovascular events following

EDTA-based injections (129).

However, EDTA chelation proved ineffective in reducing

cardiovascular events among stable patients with coronary artery

disease who also had a history of diabetes and MI (128). Therefore, current evidence does

not support its routine clinical use in CVD management. A

meta-analysis demonstrated that there is currently insufficient

evidence to determine whether chelation therapy is effective in

improving clinical outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic CVD

(138). More high-quality

randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the effects of

EDTA chelation therapy on CVD.

Although several copper chelators have shown promise

in preclinical models and selected patient populations, their

clinical efficacy remains limited, largely due to poor cellular

permeability. Moreover, these agents pose risks of off-target

toxicity and oxidative stress (139). Prolonged administration may

further result in copper deficiency, myelosuppression,

nephrotoxicity or imbalances in trace elements (140). Therefore, indicators of copper

metabolism should be carefully monitored throughout treatment.

Copper ionophores are compounds that bind copper

ions and promote their transport across cellular membranes, thereby

increasing intracellular copper concentrations. Among these agents,

elesclomol and DSF are the most extensively studied (141). Elesclomol is an antineoplastic

agent that targets mitochondrial metabolism. It can inhibit cancer

by facilitating the delivery of copper ions into cells, thereby

triggering copper-mediated apoptosis (142). DSF can markedly elevate

intracellular copper levels and inhibit angiogenesis through a

number of routes, thereby exerting an anticancer impact (143). Despite these promising findings

in oncology, no copper ionophore has yet been applied to CVD

therapy. Moreover, carrier-mediated copper delivery may aggravate

cardiovascular injury due to its pro-oxidative effects, and its

safety and tissue specificity remain notable challenges.

Dietary copper supplementation serves as a

non-specific approach to restore systemic copper homeostasis. Among

Chinese adults participating in the China Health and Nutrition

Survey, a U-shaped association exists between dietary copper

consumption and the incidence of new-onset hypertension; the

inflection point is ~1.57 mg/day (144). Furthermore, it has been

suggested that dietary copper supplementation may reverse pressure

overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (145). Prolonged supplementation with

multiple micronutrients, including copper, can enhance cardiac

function in older individuals with HF (112). Furthermore, a notable

association exists between lower copper intake in the diet and a

higher occurrence of abdominal aortic calcification (146). Longitudinal and cross-sectional

studies in the US population have suggested that moderately

increasing dietary copper intake may confer cardiovascular

protective effects (147,148). By contrast, a prospective

cohort study in the Chinese population indicated that high copper

intake (>2.45 mg/day) may increase the risk of all-cause and CVD

mortality (149). These

findings indicate that the effects of copper follow a U-shaped or

J-shaped curve, both excessively low and excessively high levels

are detrimental, with the optimal range varying depending on the

individual, dietary patterns and baseline health status.

Nevertheless, Mendelian randomization analyses have not

demonstrated a marked causal relationship between dietary copper

intake and CVDs or metabolic diseases (105). This may be due to

methodological limitations that failed to detect such complex

relationships. Currently, there is a lack of precise copper status

assessment tools for patients with CVD, and indiscriminate copper

supplementation carries potential risks. Further studies are

warranted to clarify the role of dietary copper in CVD prevention

and management.

Although research on the molecular mechanisms of

cuproptosis in cardiovascular cells is still at an early stage,

current evidence has indicated a high degree of tissue specificity.

Compared with other tissues, cardiomyocytes, which are highly

dependent on mitochondrial energy supply, are markedly sensitive to

the stability of lipoylated proteins (150). Cuproptosis in the

cardiovascular system does not occur in isolation; instead, it

reflects systemic copper homeostasis dysregulation involving

coordinated interactions among the liver, kidneys and heart.

Elevated blood copper levels, often associated with hepatic or

renal dysfunction, may increase copper uptake by cardiomyocytes. At

the molecular regulatory level, sirtuin 3 maintains intracellular

copper homeostasis by modulating the interaction between copper

transporters and the autophagy-related protein LC3B, which

suppresses cuproptosis in cardiomyocytes (151). In vascular endothelial cells,

MT2A preserves mitochondrial and vascular function by chelating

free copper, effectively blocking the cuproptosis pathway (152). In cardiomyocytes, TTM reverses

cuproptosis caused by copper overload (153). In a diabetic cardiomyopathy

model, advanced glycation end products have been shown to markedly

upregulate CTR1 mRNA and protein levels, while downregulating the

copper efflux transporters ATP7A and ATP7B; this leads to

intracellular copper accumulation, thereby inducing or exacerbating

cuproptosis (154). As shown in

Table II (5-7,116,155-162), bioinformatics and multi-omics

analyses have suggested that cuproptosis serves a broad role in CVD

pathogenesis. Nevertheless, experimental validation of the

functional relevance of these genes remains limited. For example,

although ATP7B has been proposed as a cuproptosis-associated

biomarker in ischemic cardiomyopathy (6), its direct participation in

copper-induced cardiomyocyte death remains to be experimentally

verified. Furthermore, several genes appear to have dual or

context-dependent roles, underscoring the need for further

mechanistic studies. Future studies should move beyond correlative

findings toward causal validation.

CTR1, SOD1 and ATOX1 are the most common

copper-related biomarkers. In human tumor research, substantial

evidence has supported the clinical value of CTR1. Although animal

models have revealed the role of CTR1 in CVDs (163), human clinical studies remain

extremely limited (164,165).

In a model of I/R injury, dysfunction of CTR1 in cardiomyocytes can

lead to excessive copper ion accumulation, inducing cuproptosis

(166). In addition to

potentially serving as a biomarker and target in cancer treatment,

CTR1-induced regulation of intracellular copper levels to influence

cuproptosis offers novel therapeutic approaches for various

diseases. However, the complexity of its regulation poses

challenges for clinical translation (167). SOD1 has demonstrated clear

clinical value in neurodegenerative diseases (168). Bioinformatics research has

indicated that SOD1 may serve as a potential diagnostic biomarker

for AS (7), but evidence

directly linking it to cuproptosis remains lacking in the field of

CVD. Furthermore, its application is constrained by functional

complexity and insufficient tissue specificity (169). ATOX1, as a copper chaperone and

potential transcription factor, occupies a pivotal position in the

cuproptosis-regulated network. In oncology, ATOX1 expression is

upregulated across multiple types of cancer, with its upregulation

associated with poor patient prognosis (170). However, high-quality human

clinical evidence remains scarce in the CVD field. Its potential

value lies in reflecting copper metabolic status and serving as a

prognostic indicator in both cancer and CVDs. The primary

limitations stem from its complex regulatory network, which may

compromise the specificity of ATOX1 as a standalone biomarker and

complicate activity assessment (171). As key molecules in copper

metabolism and oxidative stress pathways, as well as biomarkers for

specific disease subtypes, these three substances require unified

detection standards and large-scale prospective clinical validation

in the future to prove their predictive or prognostic value.

Precision medicine should be achieved by constructing precision

classification models based on copper homeostasis pathways through

multi-omics integration, and drugs for targeted therapy should also

be developed.

Reagents for CVDs based on cuproptosis have been

formulated. When exposed to aging conditions, copper and iron atoms

accumulate in their lower-oxidized states, triggering a cascade of

cuproptosis and ferroptosis. D-handed PtPd2CuFe can

alleviate the effects of aging in multiple aging models and has

notable therapeutic capabilities in AS, a disease that involves

multiple types of senescent cells (172). Conversely, the

mitochondrial-targeted triphenylphosphonium-modified

Cu2+ bis(diethyldithiocarbamate) can markedly increase

copper accumulation in mitochondria, and severely impair

mitochondrial morphology and functions. Therefore, it may serve as

a mitochondrial-targeted cuproptosis inducer to selectively

eliminate diseased cells (173).

Studies in animal models have shown that targeting

CTR1 during I/R injury reduces intracellular copper accumulation,

thereby suppressing cuproptosis. This intervention also alleviates

inflammation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury in

cardiomyocytes, ultimately providing protection against I/R-induced

damage (166). Serum copper

levels are often elevated in patients with CHF, potentially

enhancing copper deposition in cardiomyocytes. This may lead to

cardiomyocyte loss via cuproptosis and contribute to ventricular

remodeling. However, the clinical relevance of this association is

complicated by multiple confounding factors. In arterial walls,

copper catalyzes Fenton-like reactions that promote oxidized LDL

formation. Moreover, studies have linked copper dysregulation to

the progression of AS, implying that cuproptosis may participate in

AS pathogenesis (82,122). The molecular pathways

underlying cuproptosis in cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells and

vascular smooth muscle cells have not yet been fully elucidated. In

addition, both direct clinical evidence and clinically applicable

copper ionophores are still lacking. Nevertheless, targeting

cuproptosis holds promise as a novel therapeutic strategy for

refractory conditions such as AS and cardiomyopathy.

Copper modulation strategies have demonstrated

therapeutic potential in animal models of atherosclerosis (in

apolipoprotein E-deficient mice fed a high-fat, high-cholesterol

Western-type diet) (122),

ischemia/reperfusion injury (in rats subjected to surgical

induction of myocardial, cerebral or systemic ischemia/reperfusion)

(119) and myocardial

infarction (in female Large White pigs subjected to surgical

induction) (118), yet their

translation to clinical applications remains challenging. Major

obstacles include interspecies differences in copper metabolism,

toxicity risks arising from the dual biological roles of copper,

the absence of reliable biomarkers and clearly defined clinical

endpoints, and variability due to individual genetic and

environmental factors. Collectively, these limitations hinder the

clinical validation of safety and efficacy. Future research should

focus on developing specific inhibitors targeting cuproptosis

pathways to reduce toxic side effects, utilizing biomarkers to

assess disease risk or treatment response, and establishing

reliable technologies for monitoring copper homeostasis

dynamics.

Cuproptosis and ferroptosis, as two novel forms of

programmed cell death, display distinct yet overlapping molecular

mechanisms, regulatory pathways and therapeutic implications.

Simultaneously inducing cuproptosis and ferroptosis can produce

synergistic cytotoxic effects, and multiple nanotherapeutic

strategies (such as DSF@HMCIS-PEG-FA nanoparticles, which enable a

self-accelerating ferroptosis-cuproptosis cycle; HA@ CuCo-NC

nanoconjugates, which hijack Fe-S clusters; and dual-responsive

NSeMON-P@CuT/LipD platforms that disrupt copper metabolism) have

been designed to exploit this effect (59-61). Their combined use can overcome

single-pathway drug resistance in tumors and enhance tumor

targeting; however, the mechanisms underlying cuproptosis are not

yet fully elucidated, and potential clinical applications must

carefully address toxicity and translational limitations.

The present review provides an overview of copper

metabolism, highlights the mechanisms linking copper dysregulation

to CVDs, and summarizes therapeutic strategies that target copper

homeostasis. The recently identified form of regulated cell death,

termed cuproptosis, provides novel insights into the role of copper

in CVD. However, the mechanisms through which copper dysregulation

drives the onset and progression of CVD remain to be elucidated and

warrant validation through well-designed experimental studies.

Current evidence linking cuproptosis to CVD is largely derived from

bioinformatics and multi-omics analyses, with limited experimental

validation in cellular and animal models. The development of safe

and effective modulators of copper homeostasis represents a key

focus for future research aimed at restoring copper homeostasis in

patients with CVD. Furthermore, therapies targeting cuproptosis and

other copper-mediated cell death pathways may provide promising new

options for treating CVDs.

Not applicable.

PL and YL wrote the manuscript, and made

substantial contributions to the conception and design, literature

search, and analysis and interpretation of the literature. QM and

JW drew the figures and tables, and contributed to the literature

search and the analysis and interpretation of the literature. SY

and KW revised the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Qingdao Science and Technology

Benefiting the People Demonstration Project (grant no.

24-1-8-smjk-7-nsh); the Open Project Program of State Key

Laboratory of Frigid Zone Cardiovascular Diseases, Harbin Medical

University (grant no. HDHY2024007); the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82370291); the Major Basic Research

Projects in Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2024ZD46); and the

Taishan Scholar Distinguished Expert, Guiding Fund of Government's

Science and Technology (grant no. YDZX2021004).

|

1

|

Myint ZW, Oo TH, Thein KZ, Tun AM and

Saeed H: Copper deficiency anemia: Review article. Ann Hematol.

97:1527–1534. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mohammadifard N, Humphries KH, Gotay C,

Mena-Sánchez G, Salas-Salvadó J, Esmaillzadeh A, Ignaszewski A and

Sarrafzadegan N: Trace minerals intake: Risks and benefits for

cardiovascular health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 59:1334–1346. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chen X, Cai Q, Liang R, Zhang D, Liu X,

Zhang M, Xiong Y, Xu M, Liu Q, Li P, et al: Copper homeostasis and

copper-induced cell death in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular

disease and therapeutic strategies. Cell Death Dis. 14:1052023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon

M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, Rossen J, Joesch-Cohen L, Humeidi R,

Spangler RD, et al: Copper induces cell death by targeting

lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 375:1254–1261. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen J, Yang X, Li W, Lin Y, Lin R, Cai X,

Yan B, Xie B and Li J: Potential molecular and cellular mechanisms

of the effects of cuproptosis-related genes in the cardiomyocytes

of patients with diabetic heart failure: A bioinformatics analysis.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15:13703872024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tan X, Xu S, Zeng Y, Qin Z, Yu F, Jiang H,

Xu H, Li X, Wang X, Zhang G, et al: Identification of diagnostic

signature and immune infiltration for ischemic cardiomyopathy based

on cuproptosis-related genes through bioinformatics analysis and

experimental validation. Int Immunopharmacol. 138:1125742024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chen YT, Xu XH, Lin L, Tian S and Wu GF:

Identification of three cuproptosis-specific expressed genes as

diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for atherosclerosis.

Int J Med Sci. 20:836–848. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Liu Y and Miao J: An emerging role of

defective copper metabolism in heart disease. Nutrients.

14:7002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mason KE: A conspectus of research on

copper metabolism and requirements of man. J Nutr. 109:1979–2066.

1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pierson H, Yang H and Lutsenko S: Copper

transport and disease: What can we learn from organoids? Annu Rev

Nutr. 39:75–94. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wu J, He J, Liu Z, Zhu X, Li Z, Chen A and

Lu J: Cuproptosis: Mechanism, role, and advances in urological

malignancies. Med Res Rev. 44:1662–1682. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu WQ, Lin WR, Yan L, Xu WH and Yang J:

Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in cancer immunity and therapy.

Immunol Rev. 321:211–227. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lee J, Peña MM, Nose Y and Thiele DJ:

Biochemical characterization of the human copper transporter Ctr1.

J Biol Chem. 277:4380–4387. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Arredondo M, Muñoz P, Mura CV and Nùñez

MT: DMT1, a physiologically relevant apical Cu1+ transporter of

intestinal cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 284:C1525–C1530. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ross MO, Xie Y, Owyang RC, Ye C, Zbihley

ONP, Lyu R, Wu T, Wang P, Karginova O, Olopade OI, et al: PTPN2

copper-sensing relays copper level fluctuations into EGFR/CREB

activation and associated CTR1 transcriptional repression. Nat

Commun. 15:69472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen L, Min J and Wang F: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:3782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li Y, Ma J, Wang R, Luo Y, Zheng S and

Wang X: Zinc transporter 1 functions in copper uptake and

cuproptosis. Cell Metab. 36:2118–2129.e6. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Krężel A and Maret W: The bioinorganic

chemistry of mammalian metallothioneins. Chem Rev. 121:14594–14648.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Yang D, Xiao P, Qiu B, Yu HF and Teng CB:

Copper chaperone antioxidant 1: Multiple roles and a potential

therapeutic target. J Mol Med (Berl). 101:527–542. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Perkal O, Qasem Z, Turgeman M, Schwartz R,

Gevorkyan-Airapetov L, Pavlin M, Magistrato A, Major DT and

Ruthstein S: Cu(I) controls conformational states in human Atox1

metallochaperone: An EPR and multiscale simulation study. J Phys

Chem B. 124:4399–4411. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xue Q, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D, Liu J

and Chen X: Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy.

Autophagy. 19:2175–2195. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Harris ED: Cellular copper transport and

metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 20:291–310. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lutsenko S, Barnes NL, Bartee MY and

Dmitriev OY: Function and regulation of human copper-transporting

ATPases. Physiol Rev. 87:1011–1046. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wong PC, Waggoner D, Subramaniam JR,

Tessarollo L, Bartnikas TB, Culotta VC, Price DL, Rothstein J and

Gitlin JD: Copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase is essential

to activate mammalian Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 97:2886–2891. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Suzuki Y, Ali M, Fischer M and Riemer J:

Human copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase 1 mediates its own

oxidation-dependent import into mitochondria. Nat Commun.

4:24302013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bertinato J and L'Abbé MR: Copper

modulates the degradation of copper chaperone for Cu,Zn superoxide

dismutase by the 26 S proteosome. J Biol Chem. 278:35071–35078.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sturtz LA, Diekert K, Jensen LT, Lill R

and Culotta VC: A fraction of yeast Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase and

its metallochaperone, CCS, localize to the intermembrane space of

mitochondria. A physiological role for SOD1 in guarding against

mitochondrial oxidative damage. J Biol Chem. 276:38084–38089. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Grasso M, Bond GJ, Kim YJ, Boyd S, Matson

Dzebo M, Valenzuela S, Tsang T, Schibrowsky NA, Alwan KB, Blackburn

NJ, et al: The copper chaperone CCS facilitates copper binding to

MEK1/2 to promote kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 297:1013142021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Garza NM, Swaminathan AB, Maremanda KP,

Zulkifli M and Gohil VM: Mitochondrial copper in human genetic

disorders. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 34:21–33. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Maxfield AB, Heaton DN and Winge DR: Cox17

is functional when tethered to the mitochondrial inner membrane. J

Biol Chem. 279:5072–5080. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Sailer J, Nagel J, Akdogan B, Jauch AT,

Engler J, Knolle PA and Zischka H: Deadly excess copper. Redox

Biol. 75:1032562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Boyd SD, Ullrich MS, Skopp A and Winkler

DD: Copper sources for Sod1 activation. Antioxidants (Basel).

9:5002020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Polishchuk EV, Concilli M, Iacobacci S,

Chesi G, Pastore N, Piccolo P, Paladino S, Baldantoni D, van

IJzendoorn SC, Chan J, et al: Wilson disease protein ATP7B utilizes

lysosomal exocytosis to maintain copper homeostasis. Dev Cell.

29:686–700. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Doguer C, Ha JH and Collins JF:

Intersection of iron and copper metabolism in the mammalian

intestine and liver. Compr Physiol. 8:1433–1461. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

La Fontaine S and Mercer JF: Trafficking

of the copper-ATPases, ATP7A and ATP7B: Role in copper homeostasis.

Arch Biochem Biophys. 463:149–167. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Festa RA and Thiele DJ: Copper: An

essential metal in biology. Curr Biol. 21:R877–R883. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Turnlund JR, Keyes WR, Anderson HL and

Acord LL: Copper absorption and retention in young men at three

levels of dietary copper by use of the stable isotope 65Cu. Am J

Clin Nutr. 49:870–878. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

van den Berghe PVE and Klomp LWJ:

Posttranslational regulation of copper transporters. J Biol Inorg

Chem. 15:37–46. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ge EJ, Bush AI, Casini A, Cobine PA, Cross

JR, DeNicola GM, Dou QP, Franz KJ, Gohil VM, Gupta S, et al:

Connecting copper and cancer: From transition metal signalling to

metalloplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 22:102–113. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

40

|

Yang L, Yang P, Lip GYH and Ren J: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in cardiovascular disease therapeutics.

Trends Pharmacol Sci. 44:573–585. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chang W and Li P: Copper and diabetes:

Current research and prospect. Mol Nutr Food Res. 67:e23004682023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Jiayi H, Ziyuan T, Tianhua X, Mingyu Z,

Yutong M, Jingyu W, Hongli Z and Li S: Copper homeostasis in

chronic kidney disease and its crosstalk with ferroptosis.

Pharmacol Res. 202:1071392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Shanbhag VC, Gudekar N, Jasmer K,

Papageorgiou C, Singh K and Petris MJ: Copper metabolism as a

unique vulnerability in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res.

1868:1188932021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

44

|

Lin CH, Chin Y, Zhou M, Sobol RW, Hung MC

and Tan M: Protein lipoylation: Mitochondria, cuproptosis, and

beyond. Trends Biochem Sci. 49:729–744. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Gupte A and Mumper RJ: Elevated copper and

oxidative stress in cancer cells as a target for cancer treatment.

Cancer Treat Rev. 35:32–46. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wang Y, Chen Y, Zhang J, Yang Y, Fleishman

JS, Wang Y, Wang J, Chen J, Li Y and Wang H: Cuproptosis: A novel

therapeutic target for overcoming cancer drug resistance. Drug

Resist Updat. 72:1010182024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Han J, Luo J, Wang C, Kapilevich L and

Zhang XA: Roles and mechanisms of copper homeostasis and

cuproptosis in osteoarticular diseases. Biomed Pharmacother.

174:1165702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chen W, Yang A, Jia J, Popov YV, Schuppan

D and You H: Lysyl oxidase (LOX) family members: Rationale and

their potential as therapeutic targets for liver fibrosis.

Hepatology. 72:729–741. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Doñate F, Juarez JC, Burnett ME, Manuia

MM, Guan X, Shaw DE, Smith EL, Timucin C, Braunstein MJ, Batuman OA

and Mazar AP: Identification of biomarkers for the antiangiogenic

and antitumour activity of the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1)

inhibitor tetrathiomolybdate (ATN-224). Br J Cancer. 98:776–783.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Tsui KH, Hsiao JH, Lin LT, Tsang YL, Shao

AN, Kuo CH, Chang R, Wen ZH and Li CJ: The cross-communication of

cuproptosis and regulated cell death in human pathophysiology. Int

J Biol Sci. 20:218–230. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Han X, Zhang X, Liu Z, Liu H, Wu D, He Y,

Yuan K, Lyu Y and Liu X: Copper-based nanotubes that enhance

starvation therapy through cuproptosis for synergistic cancer

treatment. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e041212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yan C, Lv H, Feng Y, Li Y and Zhao Z:

Inhalable nanoparticles with enhanced cuproptosis and cGAS-STING

activation for synergistic lung metastasis immunotherapy. Acta

Pharm Sin B. 14:3697–3710. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang D, Tian Z, Zhang P, Zhen L, Meng Q,

Sun B, Xu X, Jia T and Li S: The molecular mechanisms of

cuproptosis and its relevance to cardiovascular disease. Biomed

Pharmacother. 163:1148302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Dreishpoon MB, Bick NR, Petrova B, Warui

DM, Cameron A, Booker SJ, Kanarek N, Golub TR and Tsvetkov P: FDX1

regulates cellular protein lipoylation through direct binding to

LIAS. J Biol Chem. 299:1050462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Rowland EA, Snowden CK and Cristea IM:

Protein lipoylation: An evolutionarily conserved metabolic

regulator of health and disease. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 42:76–85.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

56

|

Kuang J, Liu A, Xu L, Wang G, Zhang Z,

Tian C and Yu L: Electron paramagnetic resonance insights into

direct electron transfer between FDX1 and

elesclomol-Cu2+ complex in cuproptosis. Chemistry.

31:e2025011452025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Hu HT, Zhang ZY, Luo ZX, Ti HB, Wu JJ, Nie

H, Yuan ZD, Wu X, Zhang KY, Shi SW, et al: Emerging regulated cell

death mechanisms in bone remodeling: Decoding ferroptosis,

cuproptosis, disulfidptosis, and PANoptosis as therapeutic targets

for skeletal disorders. Cell Death Discov. 11:3352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yang Z, Feng R and Zhao H: Cuproptosis and

Cu: A new paradigm in cellular death and their role in

non-cancerous diseases. Apoptosis. 29:1330–1360. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Huang L, Zhu J, Wu G, Xiong W, Feng J, Yan

C, Yang J, Li Z, Fan Q, Ren B, et al: A strategy of 'adding fuel to

the flames' enables a self-accelerating cycle of

ferroptosis-cuproptosis for potent antitumor therapy. Biomaterials.

311:1227012024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Liu G, Tang R, Wang C, Yu D, Wang Z, Yang

H, Wei J, Zhu S, Gao F, Yuan F and Pan B: Bimetallic nanoconjugate

hijack Fe-S clusters to drive a closed-loop cuproptosis-ferroptosis

strategy for osteosarcoma inhibition. J Colloid Interface Sci.

703:1390522025.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang M, Xu H, Wu X, Chen B, Gong X and He

Y: Engineering dual-responsive nanoplatform achieves copper

metabolism disruption and glutathione consumption to provoke

cuproptosis/ferroptosis/apoptosis for cancer therapy. ACS Appl

Mater Interfaces. 17:20726–20740. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Husain N and Mahmood R: Copper(II)

generates ROS and RNS, impairs antioxidant system and damages

membrane and DNA in human blood cells. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int.

26:20654–20668. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Alqarni MH, Muharram MM, Alshahrani SM and

Labrou NE: Copper-induced oxidative cleavage of glutathione

transferase F1-1 from Zea mays. Int J Biol Macromol. 128:493–498.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wang K, Ning X, Qin C, Wang J, Yan W, Zhou

X, Wang D, Cao J and Feng Y: Respiratory exposure to copper oxide

particles causes multiple organ injuries via oxidative stress in a

rat model. Int J Nanomedicine. 17:4481–4496. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Piret JP, Jacques D, Audinot JN, Mejia J,

Boilan E, Noël F, Fransolet M, Demazy C, Lucas S, Saout C and

Toussaint O: Copper(II) oxide nanoparticles penetrate into HepG2

cells, exert cytotoxicity via oxidative stress and induce

pro-inflammatory response. Nanoscale. 4:7168–7184. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

He H, Zou Z, Wang B, Xu G, Chen C, Qin X,

Yu C and Zhang J: Copper oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative DNA

damage and cell death via copper ion-mediated P38 MAPK activation

in vascular endothelial cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 15:3291–3302.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Martin F, Linden T, Katschinski DM, Oehme

F, Flamme I, Mukhopadhyay CK, Eckhardt K, Tröger J, Barth S,

Camenisch G and Wenger RH: Copper-dependent activation of

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1: Implications for ceruloplasmin

regulation. Blood. 105:4613–4619. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Xiao Y, Wang T, Song X, Yang D, Chu Q and

Kang YJ: Copper promotion of myocardial regeneration. Exp Biol Med

(Maywood). 245:911–921. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Martínez-González J, Varona S, Cañes L,

Galán M, Briones AM, Cachofeiro V and Rodríguez C: Emerging roles

of Lysyl oxidases in the cardiovascular system: New concepts and

therapeutic challenges. Biomolecules. 9:6102019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wang K, Li Y, Luo C and Chen Y: Dynamic

AFM detection of the oxidation-induced changes in size, stiffness,

and stickiness of low-density lipoprotein. J Nanobiotechnology.

18:1672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Widyananda MH, Grahadi R, Dinana IA,

Ansori ANM, Kharisma VD, Jakhmola V, Rebezov M, Derkho M, Burkov P,

Scherbakov P and Zainul R: Anti-atherosclerotic potential of fatty

acids in Chlorella vulgaris via inhibiting the foam cell formation:

An in silico study. Adv Life Sci. 12:296–303. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Widyananda MH, Kurniasari CA, Alam FM,

Rizky WC, Dings TGA, Ansori ANM and Antonius Y: Exploration of

potentially bioactive compounds from Fingerroot (Boesenbergia

rotunda L.) as inhibitor of atherosclerosis-related proteins (CETP,

ACAT1, OSC, sPLA2): An in silico study. Jordan J Pharm Sci.

16:550–564. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Kciuk M, Gielecińska A, Kałuzińska-Kołat

Ż, Yahya EB and Kontek R: Ferroptosis and cuproptosis:

Metal-dependent cell death pathways activated in response to

classical chemotherapy-significance for cancer treatment? Biochim

Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1879:1891242024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Zhou D, Mao Q, Sun Y, Cheng H, Zhao J, Liu

Q, Deng M, Xu S and Zhao X: Association of blood copper with the

subclinical carotid atherosclerosis: An observational study. J Am

Heart Assoc. 13:e0334742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Zhu C, Wang B, Xiao L, Guo Y, Zhou Y, Cao

L, Yang S and Chen W: Mean platelet volume mediated the

relationships between heavy metals exposure and atherosclerotic

cardiovascular disease risk: A community-based study. Eur J Prev

Cardiol. 27:830–839. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Long P, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Zhu X, Yu K,

Jiang H, Liu X, Zhou M, Yuan Y, Liu K, et al: Profile of

copper-associated DNA methylation and its association with incident

acute coronary syndrome. Clin Epigenetics. 13:192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Kuzan A, Wujczyk M and Wiglusz RJ: The

study of the aorta metallomics in the context of atherosclerosis.

Biomolecules. 11:9462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Li H, Zhao L, Wang T and James Kang Y:

Dietary Cholesterol supplements disturb copper homeostasis in

multiple organs in rabbits: Aorta copper concentrations negatively

correlate with the severity of atherosclerotic lesions. Biol Trace

Elem Res. 200:164–171. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Bügel S, Harper A, Rock E, O'Connor JM,

Bonham MP and Strain JJ: Effect of copper supplementation on

indices of copper status and certain CVD risk markers in young

healthy women. Br J Nutr. 94:231–236. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Diaf M and Khaled MB: Associations between

dietary antioxidant intake and markers of atherosclerosis in

middle-aged women from north-western Algeria. Front Nutr. 5:292018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Kärberg K, Forbes A and Lember M: Raised

dietary Zn:Cu ratio increases the risk of atherosclerosis in type 2

diabetes. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 50:218–224. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Sudhahar V, Shi Y, Kaplan JH, Ushio-Fukai

M and Fukai T: Whole-transcriptome sequencing analyses of nuclear

antixoxidant-1 in endothelial cells: Role in inflammation and

atherosclerosis. Cells. 11:29192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Das A, Sudhahar V, Ushio-Fukai M and Fukai

T: Novel interaction of antioxidant-1 with TRAF4: Role in

inflammatory responses in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 317:C1161–C1171. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Yang L, Chen X, Cheng H and Zhang L:

Dietary copper intake and risk of stroke in adults: A case-control

study based on national health and nutrition examination survey

2013-2018. Nutrients. 14:4092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Hu L, Bi C, Lin T, Liu L, Song Y, Wang P,

Wang B, Fang C, Ma H, Huang X, et al: Association between plasma

copper levels and first stroke: A community-based nested

case-control study. Nutr Neurosci. 25:1524–1533. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Lai M, Wang D, Lin Z and Zhang Y: Small

molecule copper and its relative metabolites in serum of cerebral

ischemic stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 25:214–219.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Xiao Y, Yuan Y, Liu Y, Yu Y, Jia N, Zhou

L, Wang H, Huang S, Zhang Y, Yang H, et al: Circulating multiple

metals and incident stroke in Chinese adults. Stroke. 50:1661–1668.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Zhao H, Mei K, Hu Q, Wu Y, Xu Y, Qinling,

Yu P, Deng Y, Zhu W, Yan Z and Liu X: Circulating copper levels and

the risk of cardio-cerebrovascular diseases and cardiovascular and

all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

longitudinal studies. Environ Pollut. 340:1227112024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Zhang M, Li W, Wang Y, Wang T, Ma M and

Tian C: Association between the change of serum copper and ischemic

stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Mol Neurosci.

70:475–480. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Peng Y, Ren Q, Ma H, Lin C, Yu M, Li Y,

Chen J, Xu H, Zhao P, Pan S, et al: Covalent organic framework

based cytoprotective therapy after ischemic stroke. Redox Biol.

71:1031062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Xu J, Xu G and Fang J: Association between

serum copper and stroke risk factors in adults: Evidence from the

national health and nutrition examination survey, 2011-2016. Biol

Trace Elem Res. 200:1089–1094. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Yang F and Smith MJ: Metal profiling in

coronary ischemia-reperfusion injury: Implications for KEAP1/NRF2

regulated redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 210:158–171. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Ding C, Wang B, Zheng J, Zhang M, Li Y,

Shen HH, Guo Y, Zheng B, Tian P, Ding X and Xue W: Neutrophil

membrane-inspired nanorobots act as antioxidants ameliorate

ischemia reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. ACS Appl Mater

Interfaces. 15:40292–40303. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Kokubo Y, Matson GB, Derugin N, Hill T,

Mancuso A, Chan PH and Weinstein PR: Transgenic mice expressing

human copper-zinc superoxide dismutase exhibit attenuated apparent

diffusion coefficient reduction during reperfusion following focal

cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 947:1–8. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Chen Z, Oberley TD, Ho Y, Chua CC, Siu B,

Hamdy RC, Epstein CJ and Chua BH: Overexpression of CuZnSOD in