Population aging represents a significant social

challenge on a global scale. As human lifespans extend and

fertility rates continue to decline in developed nations,

projections indicate that by 2050, the global population of

individuals aged 65 years and older will reach 2.1 billion

(1). Among the most substantial

social burdens associated with aging is the prevalence of

neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) (2). NDDs encompass a group of

neurological disorders characterized by the progressive

degeneration of neurons within the central nervous system (CNS)

(3), thereby adversely impacting

the quality of life and well-being of millions worldwide. The

incidence of NDDs increases exponentially with advancing age

(2). Current research indicates

that significant damage to the structure and function of neural

networks, coupled with extensive neuronal loss leading to

heterogeneity and disruption of neural circuit integrity, are key

characteristics of NDDs (3-5).

Nevertheless, due to the intricate biological mechanisms underlying

NDDs and the challenges associated with developing targeted

pharmacological interventions, effective treatment of these

disorders remains a formidable challenge (6,7).

Studies have shown that pathological protein

aggregation, synaptic and neuronal network dysfunction, protein

homeostasis abnormalities, cytoskeletal abnormalities, energy

metabolism changes, DNA and RNA defects, and inflammation are

typical features of NDDs such as Alzheimer's disease (AD),

Parkinson's disease (PD), primary tauopathies, frontotemporal

dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (3). Neuroinflammation is a significant

pathological marker of NDDs, and the activation of

neuroinflammatory signals plays a clear role in neurodegeneration

(8).

The interaction between astrocytes and both resident

and infiltrating cells within the CNS is pivotal in modulating

tissue states under both physiological and pathological conditions.

Research has demonstrated that astrocytes are responsive to

inflammatory signals and can promote inflammation (9,10), thereby regulating various life

processes within the nervous system under these conditions.

Importantly, the pathological microenvironment of the nervous

system can activate astrocytes (11-13), which are essential for preserving

neuronal health and function. Recent studies have indicated that

astrocytes provide critical support to neurons (14), and their phenotypic

transformation is intricately linked to the onset and progression

of NDDs (15). Further

investigations have revealed that astrocytes are involved not only

in the formation of synaptic networks but also in maintaining

glutamate homeostasis between astrocytes and neurons (16,17), a balance crucial for normal

neuronal function. Furthermore, reactive astrocytes are

characteristically activated in NDDs, interacting with various

types of neurons and thereby accelerating the progression of these

disorders. Research has demonstrated that reactive astrocytes have

a substantial impact on synaptic function, energy homeostasis,

protein aggregation and neurodegeneration (18). The rapid advancements in

single-cell sequencing, flow cytometry sorting and metabolomics

have progressively illuminated the critical role of astrocytes in

the risk association of NDDs. However, the precise biological

mechanisms underlying these associations have yet to be fully

elucidated.

Lipid metabolism constitutes a fundamental aspect of

the brain's metabolic processes, with fatty acids serving as the

primary substrates in this context (19-23). LDs function as essential

organelles for the storage of fatty acids and play critical roles

in inflammation, metabolic disorders and cellular communication

(24,25). While the biological functions of

LDs have been extensively investigated in peripheral organs such as

the liver and heart, their roles within the brain, a central organ,

have received comparatively less attention (26). Recently, there has been a growing

recognition among researchers regarding the presence and

significance of LDs as dynamic organelles within the CNS (25,26). LDs are found in various neural

cell types, with a particularly high concentration in astrocytes

(27,28). Nonetheless, the implications of

abnormal astrocytic LDs in the onset and progression of NDDs, as

well as the specific mechanisms involved, remain inadequately

elucidated. This article aims to synthesize and discuss the

functions of astrocytic LDs and the impact of LD abnormalities on

the initiation and progression of NDDs, with the objective of

exploring potential therapeutic strategies and innovative research

directions focused on LDs.

The CNS exhibits considerable cellular

heterogeneity. Its cellular composition encompasses not only

neurons but also a diverse array of glial cells, including

astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells and peripheral glial

cells. Among these, astrocytes are the most prevalent glial cell

type within the CNS, fulfilling essential functions such as

supporting and nourishing neurons (29,30), regulating the integrity of the

blood-brain barrier (BBB) (31),

maintaining the homeostasis of the cellular microenvironment

(32) and mediating immune

responses (33). Recent

investigations have elucidated the heterogeneity among astrocytes,

with single-cell RNA sequencing technology identifying

multitudinous transcriptionally distinct astrocyte states,

including ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit

β 2 astrocytes, S100 calcium binding protein A4 astrocytes, G

protein-coupled receptor 84 astrocytes, complement C3/G0/G1 switch

2 astrocytes, glial fibrillary acidic protein/transmembrane 4L6

family member 1 astrocytes, glutathione synthetase/crystallin αB

astrocytes (30,34). In individuals with temporal lobe

epilepsy, as well as in murine models of epilepsy, there is a

notable accumulation of lipids within astrocytes, resulting in the

emergence of lipid-accumulating reactive astrocytes, termed LARAs.

This newly identified subtype of reactive astrocytes is

distinguished by an upregulation of apolipoprotein E (APOE)

expression. Reactive astrocytes are prevalent in a range of human

NDDs, providing valuable insights and potential research pathways

for targeting lipid metabolism in specific astrocyte subtypes

during the development and treatment of NDDs (35). Research suggests that the various

astrocyte subtypes are not only integral to the maintenance of

nervous system homeostasis but also help to find new astrocyte

subtypes as a target for CNS repair (30,34).

Astrocytes play a crucial role in the construction

of neural circuits by engaging in calcium signaling responses

(36), neurotransmitter reuptake

(37,38), maintenance of ion (39) and inorganic phosphate homeostasis

(40), and involvement in

synaptic formation and elimination (41). The membranes of astrocytes are

enriched with glutamate transporters, such as glutamate transporter

1 (42) and glutamate-aspartate

transporter (43), which

facilitate the rapid clearance of glutamate from the synaptic cleft

following neurotransmission, effectively preventing

glutamate-induced excitotoxicity and providing metabolic and

nutritional support to neurons. Research indicates that this

adaptive inflammatory response of astrocytes encompasses both

anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory effects (44). In the initial phase of infection,

characterized by acute inflammatory injury, anti-inflammatory

cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β and interleukin 10

(IL-10) play a protective role by mitigating inflammation and

safeguarding neuronal integrity. Conversely, during the chronic

phase of infection, the extensive release of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-1β,

significantly contributes to neuronal dysfunction and the

advancement of NDDs. Studies have demonstrated that IL-1β

stimulates over-activated astrocytes to secrete vascular

endothelial growth factor, which increases the permeability of the

BBB and exacerbates inflammation (45).

The intricate coordination between astrocytes and

neurons is essential for the functionality of the CNS. Empirical

evidence indicates that astrocyte-neuron coupling not only

furnishes metabolic support to neurons (46), but also modulates the ionic

milieu of the neuronal microenvironment (47) and facilitates the release and

transmission of synaptic vesicles. Concurrently, under

physiological conditions, astrocytes synthesize and release various

lipids while facilitating their transport to neurons, thereby

supporting synaptic formation and function (48,49). In the context of brain injury and

NDDs, the activation of astrocytes and the presence of aberrant

inflammatory responses can profoundly impact neuronal function and

survival, leading to disruptions in neural network

connectivity.

LDs serve as the primary organelles for lipid

metabolism and storage within cells, encapsulated by a monolayer of

phospholipid membrane. These organelles predominantly consist of

neutral lipids and phospholipids. LDs function as energy storage

entities, playing a crucial role in lipid metabolism and energy

homeostasis. They are ubiquitously present across various cell

types, with a pronounced presence in adipocytes, where they occupy

a significant portion of the cytoplasmic volume and exhibit a

unique organelle architecture. Notably, LDs are the sole organelles

characterized by a core of hydrophobic neutral lipids enveloped by

a phospholipid monolayer. The core is primarily composed of

triglycerides and a minor fraction of cholesterol esters. Research

indicates that the expansion of LDs involves the lipid transport

facilitated by APOE and the accumulation and budding of newly

synthesized neutral lipids at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

(27). The budding process of

LDs is regulated by alterations in the contact angle between the ER

and LDs, as well as the asymmetry in monolayer tension. LDs

originate in the ER, where acetyl-CoA and glycerol 3-phosphate

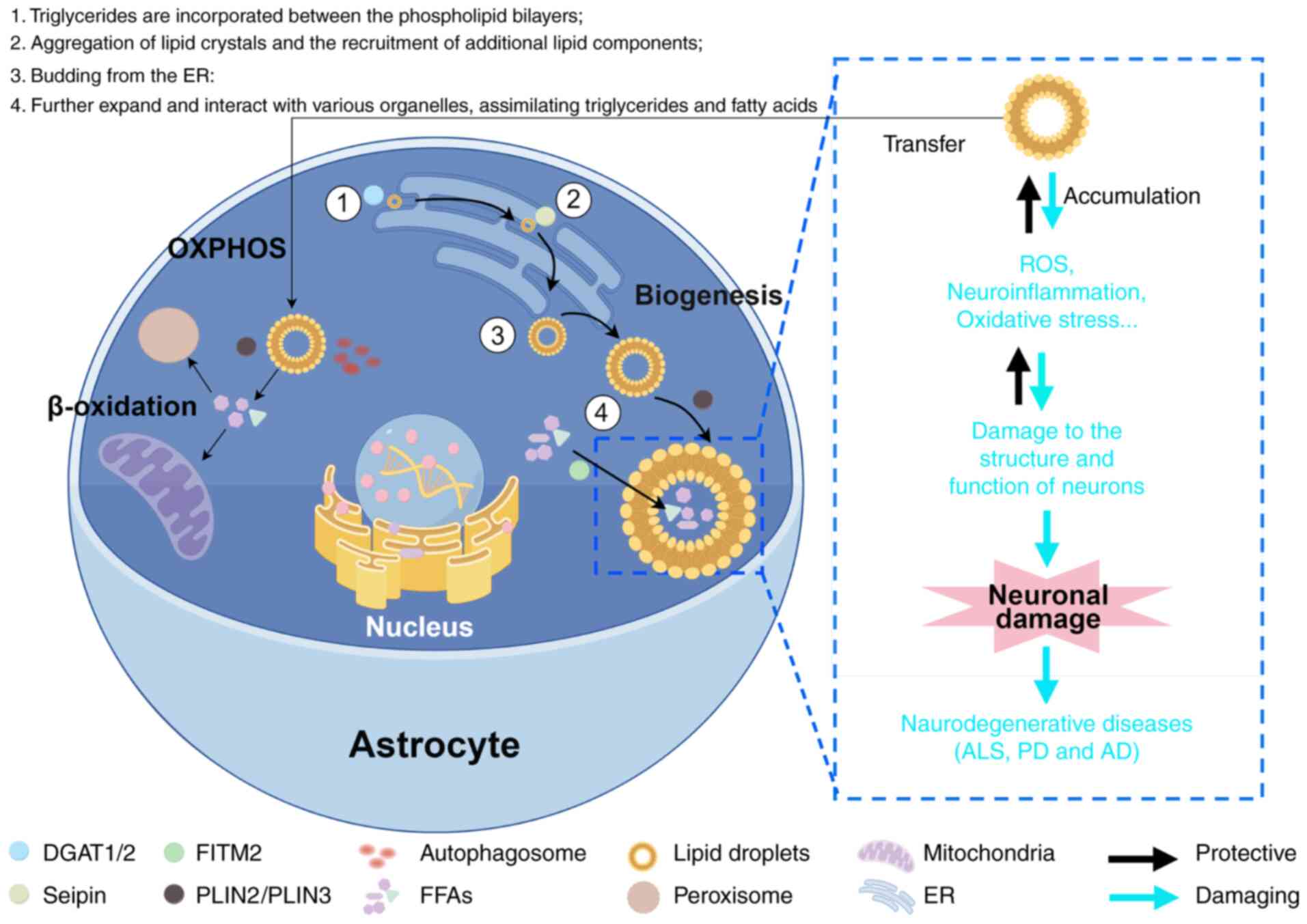

facilitate the synthesis of triglycerides (50). Initially, triglycerides are

incorporated between the phospholipid bilayers, subsequently

promoting the localized aggregation of lipid crystals and the

recruitment of additional lipid components, thereby facilitating

the expansion of LDs formation. Upon budding from the ER, LDs

migrate into the cytoplasm, where they can further expand and

interact with various organelles, assimilating triglycerides and

fatty acids, which contributes to their volumetric increase

(51). The elevation of neutral

lipid levels within the ER enhances LD formation, serving to

sequester potentially harmful free fatty acids (FFAs) and mitigate

lipotoxicity (52). Cellular

stress can trigger LD biogenesis, stimulating lipid synthesis,

autophagy, lysosomal phospholipid conversion or an increase in

phospholipase activity, thereby modulating LD formation and

maintaining intracellular lipid homeostasis (Fig. 1).

Proteins associated with LDs are essential for their

functional roles. These proteins are transported to LDs via

distinct mechanisms, influencing the development, maturation and

degradation of LDs. Class I proteins are directly targeted to LDs

from the ER. Examples of Class I LD proteins include the lipid

biosynthesis enzymes glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 4 and

diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2), caveolin-1 and

caveolin-2 (53). An example is

ceramide - the production of acylated ceramides is catalyzed by the

key lipid-synthesizing enzyme DGAT2 on lipid droplets. It relies on

its N-terminal hydrophobic domain to embed itself in the ER

membrane, ensuring stable localization to LDs and efficient

catalysis of triglyceride synthesis, thereby targeting biogenesis

to LDs. By contrast, Class II proteins are directed to the surface

of LDs from the cytoplasm through amphipathic helices or extended

hydrophobic residues. The recruitment of these proteins by LDs is

modulated by developmental requirements or the metabolic state of

the cell. Specific proteins, including recombinant perilipin 3

(PLIN3), reticulon 4 (RTN4), cytoskeletal linker protein 7,

receptor expression-enhancing protein 5, Seipin and peroxisome

biogenesis factor 30 (PEX30), are integral to LD formation. DGAT1/2

catalyzes the final step of triglyceride synthesis and marks the

initiation point of LD biogenesis (54); Seipin promotes the initial

aggregation of neutral lipids through tissue-specific ER domains

and ensures the proper morphology and size of nascent LDs (55); Fat storage-inducing transmembrane

protein 2 facilitates the transfer of neutral lipids into

developing LDs, promoting LD expansion (56). Notably, Seipin influences the

budding and formation of LDs through its impact on the levels of

phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol and diacylglycerol (DAG).

Newly formed LDs bud from the ER and require the core regulatory

actions of PLIN family proteins to develop into fully functional

LDs. The cell death-inducing DFF45-like effector family proteins

serve as key regulators of LD growth and fusion. They mediate the

directed transfer of neutral lipids from small to large LDs by

forming bridging structures between adjacent LDs, thereby promoting

LD growth and fusion (57). The

PLIN family members (PLIN1 to PLIN5) are representative proteins

found on the surface of LDs, classified as type II proteins that

regulate interactions between LDs and the cytoplasmic environment.

Each PLIN family member exhibits unique expression patterns and

possesses distinct fundamental functions (58). PLIN4 possesses the ability to

interact with the LD membrane and establish a protective barrier,

thereby shielding LDs from degradation by lipases. PLIN3

contributes to the stability and metabolic processes of LDs

(59), while RTN4 is implicated

in their formation and localization. Cytoskeletal linker protein 7

potentially regulates LD formation by modulating the cytoskeletal

architecture. Additionally, PEX30 facilitates LDs formation by

modulating the ER domain (60).

The brain is the organ with the highest cholesterol

content in the body, and maintaining cholesterol homeostasis is

essential for proper brain function. A deficiency in cholesterol

can impair memory formation, while excessive cholesterol

accumulation can damage neuronal synaptic plasticity and induce

neuronal apoptosis (61).

Although cholesterol in the brain is synthesized locally, the

capacity for cholesterol synthesis varies among different cell

types. Astrocytes, for instance, possess a greater ability to

synthesize cholesterol from acetyl-CoA compared to neurons, which

have lower levels of cholesterol synthesis enzymes (62). Astrocytes can supply cholesterol

to surrounding neurons. Research has identified key cholesterol

transporters, including APOE (63) and members of the ATP-binding

cassette transporter family, such as ATP-binding cassette subfamily

A member 1 (ABCA1) (64) and

ABCG4 (65). Astrocytes

facilitate cholesterol transport by synthesizing lipoproteins and

apolipoproteins. Research indicates that astrocytes secrete

cholesterol-rich lipoproteins containing APOE, primarily mediating

neuronal lipid uptake through endocytosis facilitated by

low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and LDLR-related protein 1

(LRP1) co-receptors. Different APOE homozygous expression states

also determine the efficiency and specificity of lipid shuttles.

Phospholipid-rich, small high-density lipoprotein particles are

readily recognized by APOE2 and APOE3, whereas APOE4 more

frequently binds to triglyceride-rich large very-LDL particles

(66). The presence of the BBB

renders cholesterol metabolism in the brain relatively independent

from systemic cholesterol metabolism. Lipoproteins are exclusively

synthesized within the CNS, where cholesterol sourced from

astrocytes is crucial for the formation of neuronal membranes and

synapses. This astrocytic cholesterol is instrumental in modulating

various biochemical processes within the synaptic membrane, such as

membrane fluidity and ion channel function (67). Furthermore, evidence from

macrophage-specific ABCA1-knockout mice demonstrates that

cholesterol significantly influences multiple regulatory

mechanisms, including membrane protein activity and localization,

lipid raft formation, glucose transport and inflammatory signaling

(61,68). Lipid rafts, which are membrane

microdomains enriched with cholesterol and sphingolipids, are

recognized as pivotal regulators of numerous membrane protein

activities (69). The activation

of pro-inflammatory receptors, such as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4),

predominantly occurs within these cholesterol-rich membrane

regions. Cholesterol also impacts the membrane transport and

functionality of the glucose transporter glucose transporter 1

(70). In comparison to the

APOE3 isoform, APOE4 demonstrates reduced efficacy in inhibiting

neuronal cholesterol synthesis and facilitating

acetylation-mediated memory formation (63).

Astrocyte-secreted lipid factors function as

signaling molecules that significantly impact neuronal

proliferation, migration and synapse formation (71). The sterol regulatory

element-binding protein (SREBP) family, particularly SREBP2, is

integral to lipid metabolism, as it regulates the transcription of

numerous genes involved in sterol synthesis (72). Presently, it is yet to be

determined and confirmed whether astrocyte-derived effectors can be

transported to neurons and subsequently influence memory formation.

Furthermore, the degree to which astrocytes adapt to neuronal

demands and sustain brain cholesterol homeostasis warrants further

investigation.

Sphingolipids, a class of lipids containing

sphingosine, encompass ceramides and sphingomyelins and serve as

essential components of cellular membranes, including lipid rafts.

Metabolites derived from sphingolipids have been recognized as

significant regulators of inflammation, autophagy, cellular growth

and survival (73). Notably,

ceramides, which can be further modified to form gangliosides, are

implicated in the pathogenesis of NDDs (74). Given that de novo

synthesis of sphingolipids also occurs in the ER, recent research

has demonstrated that ceramides can be converted into

acylglyceramide through the action of DAG O-acyltransferase and

subsequently stored in LDs (75). Sphingolipids fulfill multiple

roles in astrocyte function, particularly in the context of NDDs,

where alterations in their structure and metabolism are observed.

Astrocytes modulate synaptic architecture and neuronal

functionality through the regulation of sphingolipids, including

the production of gangliosides. In the context of AD, membrane

gangliosides engage in interactions with amyloid proteins, thereby

facilitating plaque formation and influencing the fibrillation

process of α-synuclein (76).

This conclusion has been validated in vitro using human

SH-SY5Y cells and membrane liposome models (77). The aggregation of gangliosides,

mediated by antibodies, has the potential to activate signaling

pathways that suppress neuronal growth. Gangliosides synthesized by

astrocytes contribute to the enhancement of neurite outgrowth, the

regulation of neuronal inflammation and the stabilization of

neuron-astrocyte interactions (78).

Phospholipids constitute essential components of

cellular membranes, forming phospholipid bilayers that are vital

for maintaining neuronal membrane fluidity, facilitating signal

transduction and supporting synaptic function. The brain

synthesizes substantial quantities of phospholipids, including

phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine

and phosphatidylinositol. These phospholipids are conveyed to

neurons via vesicle and protein-mediated transport systems, thereby

influencing neuronal fate (71).

Empirical studies have demonstrated that phosphatidylethanolamine

promotes the differentiation of nerve cells into astrocytes by

interacting with phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein 1 through

the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular

signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway, whereas

phosphatidylcholine exerts an antagonistic effect (79,80).

Neurons possess a restricted capacity for fatty acid

oxidation. Together, neurons and astrocytes constitute a critical

coupled unit for cerebral energy metabolism. Astrocytes supply

metabolic substrates and antioxidant factors to neurons, thereby

enhancing the efficiency of neuronal information transmission

(81). By storing and releasing

lipids via LDs, astrocytes fulfill the metabolic demands of

neurons, which is essential for neuronal function and the

maintenance of brain homeostasis. Lipid metabolism represents a

significant aspect of the interaction between neurons and

astrocytes. Research indicates that lipids recycled from neurons

are transferred to astrocytes, where they are stored in LDs prior

to mitochondrial metabolism (82).

The accumulation of neutral lipids in astrocytes

primarily occurs through two pathways. Firstly, activated neurons

produce FFAs, which are subsequently secreted as APOE4 lipid

particles. These particles are internalized by neighboring

astrocytes via endocytosis and are stored in LDs. Docosahexaenoic

acid (DHA) is an unsaturated fatty acid with neuroprotective

effects on cognitive function and memory, and its reduced levels

are associated with the progression of NDDs (83). In the brain, DHA exists in two

forms: Phospholipid-bound and free. The major facilitator

superfamily domain containing 2A (MFSD2A) is exclusively present in

the endothelial cells forming the BBB and transports

phospholipid-bound DHA in the form of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC)

in a sodium-dependent manner, enabling its passage across the BBB

into the brain. This process is critical for maintaining brain

lipid composition (84). FFAs

bind to cell membrane proteins, such as the MFSD2A protein that

transports omega-3 DHA into the brain as LPC-DHA (84), and plasma membrane fatty

acid-binding proteins (FABPs) located on the BBB endothelial cell

membrane, which promotes the uptake and activation of long-chain

fatty acids and CD36 (85,86), which mediates cellular uptake of

various lipids including long-chain fatty acids, enabling their

passage through the BBB into cells. Once inside the body, fatty

acids form complexes with FABP7, facilitating their transport from

the cell membrane to various metabolic sites within the cell.

Although FABP3 and FABP5 are present, FABP7 is the predominant

isoenzyme in the brain and is crucial for the regulation of

dendritic morphology and synaptic transmission in neurons (87). Furthermore, in the

astrocyte-specific carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT-1) A

knockout mouse model, astrocytes exhibit preferential expression of

CPT-1, an essential enzyme in the β-oxidation of long-chain fatty

acids, thereby providing energy for cellular functions (88). LPC-DHA differs from

non-esterified DHA transport mediated by fatty acid transport

protein 1 and cellular metabolic pathways mediated by CD36 as a

long-chain free fatty acid transporter (89). Lipids acquired through these

distinct pathways can be utilized in astrocytes for energy

production, membrane synthesis or storage within LDs, thereby

participating in the brain-wide lipid distribution network.

The formation of LDs is integral to the regulation

of fatty acid storage and hydrolysis, as well as providing

substrates for β-oxidation, thereby playing a pivotal role in lipid

metabolism. Under conditions of stress, such as starvation,

β-oxidation of LDs serves as an alternative energy generation

pathway for various cell types, including astrocytes. Research has

highlighted the significance of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)

activity in astrocytes for fatty acid degradation and the

maintenance of lipid homeostasis in the brain. A deficiency in

OXPHOS activity within astrocytes not only leads to the

accumulation of LDs but also precipitates AD-like pathologies,

including synaptic loss, neuroinflammation, demyelination and

cognitive dysfunction (82).

When the fatty acid load surpasses the OXPHOS capacity of

astrocytes, there is an increase in acetyl-CoA levels, which

subsequently promotes the acetylation and activation of signal

transducer and activator of transcription 3 (82). Following lipid overload, these

abnormally activated astrocytes will stimulate neuronal fatty acid

oxidation and oxidative stress responses, which in turn activate

microglia through IL-3 signaling and start inflammatory signaling

cascades (82). Research has

established that the formation of LDs can subsequently impact

mitochondrial function. For instance, astrocytes exposed to lipid

mixtures can initiate the formation of intracellular LDs, which

results in a reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential and an

increase in mature apoptotic inducible factor levels, culminating

in mitochondrial dysfunction (90). The defects in OXPHOS and the

accumulation of LDs exhibit a mutually reinforcing and synergistic

relationship. Further investigations have demonstrated that OXPHOS

defects contribute to abnormal LD accumulation and trigger NDDs

(91). A targeted knockout of

the key OXPHOS gene, mitochondrial transcription factor A, in

astrocytes has shown significantly elevated levels of FFAs,

triacylglycerols, monoglycerides and cholesterol esters in the

brains of mice, accompanied by progressive neurodegeneration

(82). This study confirmed that

mitochondrial dysfunction impairs astrocytic energy metabolism,

with a pronounced enrichment in lipid metabolism pathways.

Consequently, this leads to abnormal LD accumulation and drives

astrocyte-mediated neurotoxicity.

LDs form tight physical connections with

mitochondria and peroxisomes via membrane contact sites, actively

participating in and regulating the network hub of lipid

trafficking. In normal astrocytes, LDs typically cluster near the

nucleus and reside adjacent to mitochondria and the ER. Through

direct connections, these droplets create microenvironments that

direct fatty acid transport to mitochondria. The key mechanism

involves efficient flow from the LD core to mitochondria for

β-oxidation, rapidly generating ATP to fuel astrocyte

energy-consuming processes (28). Very long-chain fatty acids

(VLCFAs), which mitochondria cannot directly β-oxidize, are

primarily degraded by peroxisomes. Research indicates peroxisomes

play a vital role in the oxidation and degradation of long-chain

and VLCFAs, contributing significantly to reactive oxygen species

(ROS) production and clearance, thereby helping maintain cellular

redox balance. VLCFAs require preliminary oxidation within

peroxisomes before entering mitochondria for β-oxidation, a process

facilitated by the LD-peroxisome contact site (92).

In the CNS, neurons rely on autophagy to maintain

synaptic neurotransmission and prevent neurodegeneration (93). Autophagosomes selectively engulf

LDs to promote lysosomal degradation-a process termed lipophagy.

During energy deficiency, phagocytes ensure LD degradation through

this pathway, which is crucial for lipid and energy homeostasis

(94). During lipophagy, a

double-membrane autophagosome engulfs LDs or partial LDs and fuses

with lysosomes containing acid hydrolases, degrading LDs into FFAs

(95). Studies in PD models

reveal that pathological progression correlates with the

PLIN4/LD/mitochondrial autophagy axis, where PLIN4 upregulation

leads to abnormal LD accumulation (96).

Enzymatic lipolysis is the primary mechanism for

fatty acid mobilization. Research indicates that adipose

triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) are

two key enzymes in lipid mobilization. ATGL hydrolyzes the first

ester bond to produce DAG and fatty acids, followed by HSL

converting DAG into monoglyceride and fatty acids (97). Modulating ATGL expression alters

LD mobilization in cells and tissues (98). Studies reveal that ATGL promotes

LD accumulation in mouse microglia and suppresses

lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation (99). Enzyme-controlled lipolysis is

tightly coupled with the OXPHOS capacity of astrocytes. Research

indicates that knocking out carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1A (a

key enzyme in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation) in adult mouse

astrocytes inhibits fatty acid oxidation and alters the brain's

metabolomic profile, leading to cognitive impairment (100). Against a backdrop of heightened

synaptic activity, efficient lipolysis provides substrates for

OXPHOS, ensuring astrocytes effectively support neuronal

function.

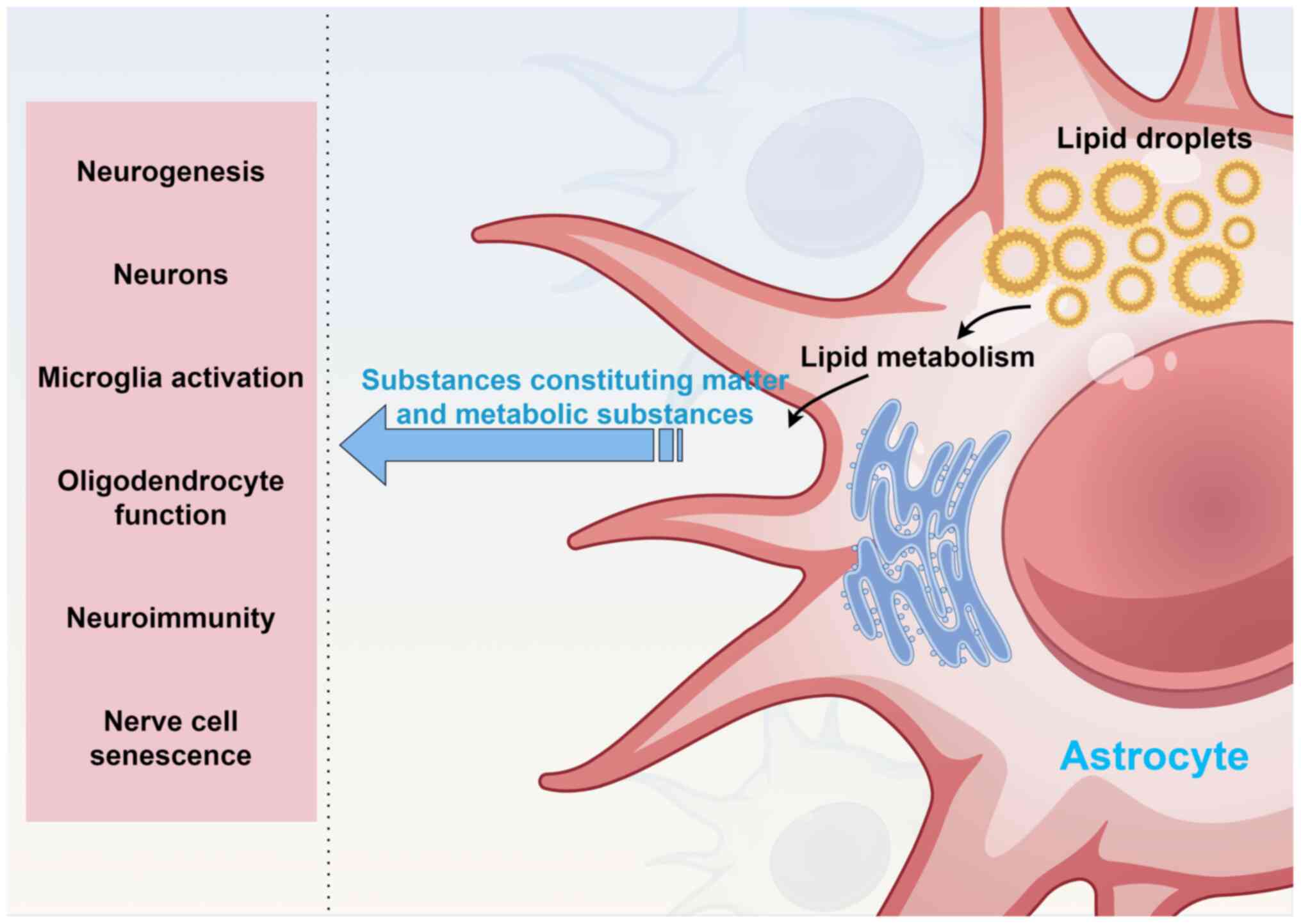

Astrocyte LDs influence numerous neurobiological

processes through lipid metabolism, such as neurogenesis, neuronal

structure and function, microglial activation, oligodendrocyte

function, neuroimmunity and nerve cell senescence (Fig. 2).

Astrocytes play a critical role in regulating

neuronal metabolism and maintaining brain homeostasis through the

storage and release of lipids via LDs. Their lipid metabolism is

essential for supporting energy production, cell membrane synthesis

and neuronal repair, as well as modulating neuronal activity, which

in turn influences neurogenesis (101). Studies using a mouse model of

middle cerebral artery occlusion indicate that the overexpression

of endothelin-1 (ET-1) in astrocytes within the murine brain can

adversely affect hippocampal neurogenesis following cerebral

ischemic injury, with peroxiredoxin 6 implicated in this process

(102). Nonetheless, the impact

of ET-1 overexpression in astrocytes on lipid metabolism and the

underlying pathways requires further elucidation. Given that

neurons possess a limited capacity for lipid synthesis during

development, the provision of lipids by astrocytes is vital for

neuronal growth and differentiation. Lipids, including cholesterol

and fatty acids, are indispensable for the formation of neuronal

membranes and synapses, and lipid factors secreted by astrocytes

also influence neuronal proliferation and migration.

Lipid metabolism is intricately regulated by the

PLINs and SREBPs, which subsequently influence the formation and

functionality of LDs (103,104). Regulatory factors of lipolysis,

such as PLINs, modulate the lipolytic process by governing the

recruitment of lipases and their cofactors to the surface of LDs.

For instance, PLIN1 acts as an inhibitor of lipolysis, and in a

chronic PD mouse model induced by

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine combined with

probenecid, PLIN4 was confirmed to promote the formation of LDs

(105,106). Transcription factors, including

the SREBP family, play a crucial role in regulating the expression

of genes involved in lipid synthesis. The depletion of

astrocyte-specific SREBP2 has significant implications for brain

development and function, manifesting in reduced synaptic growth of

neurons and a decrease in overall brain size and weight (107).

The coordination of lipid metabolism between neurons

and glial cells is essential for the proper functioning of the

nervous system. Astrocytes play a pivotal role in this process by

storing and releasing lipids through LDs, thereby supplying lipids

necessary for energy production, cell membrane synthesis and repair

in neurons. Additionally, these lipids serve as signaling molecules

that modulate neuronal activity. Research has demonstrated that

regulating neuronal glycerolipid metabolism by enhancing the

synthesis of phospholipids, which are integral to cell membrane

composition, while concurrently reducing the synthesis of storage

lipids such as triglycerides, can facilitate the regeneration of

nerve axons following injury (108).

Recent research has increasingly elucidated the

critical role of cholesterol and phospholipids supplied by

astrocytes in neuronal synapse formation and axon growth (109). Initial investigations

established that cholesterol derived from glial cells, secreted by

astrocytes and transported via the lipoprotein APOE, serves as a

potent cofactor in the induction of retinal ganglion cell synapse

formation (110). Subsequent

studies identified additional astrocyte-secreted proteins,

including thrombospondin ½ (111), hevin (112) and glypicans (113), which facilitate the formation

of excitatory synapses and enhance glutamatergic activity. However,

the mechanisms by which developing astrocytes regulate axon growth

remain less understood. Recent investigations have revealed that

astrocyte-derived exosomes, particularly the hepatic and glial cell

adhesion molecule signal present on their surface, play a

developmental role in modulating the axon growth of cortical

pyramidal neurons (114). APOE,

the primary cholesterol transporter secreted by astrocytes, plays a

crucial role in promoting synaptogenesis while markedly inhibiting

the stimulatory impact of astrocyte-derived exosomes on axonal

growth (114). Notably, a

deficiency in APOE during developmental stages has been indicated

to lead to a significant reduction in the spine density of cortical

pyramidal neurons (114). This

study suggests that astrocyte exosomes, through their surface

contact mechanisms, work in opposition to APOE to collectively

regulate axonal growth and dendritic spine formation in pyramidal

neurons during the early postnatal period (114). Consequently, astrocytes are

capable of transferring lipids to neurons via both direct and

indirect pathways, including the active transport of APOE and

lipoprotein particles.

Fatty acids constitute the fundamental building

blocks of all lipid types, rendering the precise regulation of

their metabolic balance in the brain essential for optimal lipid

functionality. Excessive FFA intake can lead to cellular

accumulation and subsequent damage (115); thus, mitigating excessive FFA

intake is an effective strategy to avert lipid toxicity. Neurons

facilitate the release of FFAs via APOE particles, which are

subsequently internalized by astrocytes through endocytosis and

sequestered in LDs as triglycerides, thereby mitigating their

cytotoxic effects (116). Upon

entry into astrocytes, the FFAs released are assimilated by LDs and

utilized as substrates for mitochondrial β-oxidation. This process

enables mitochondria to catabolize stored fatty acids, thereby

generating energy and sustaining normal neurological function. The

formation of astrocytic LDs and the intercellular lipid transport

from neurons to glial cells are modulated by APOE levels.

Astrocytic APOE may play a regulatory role in lipid transfer, while

neuron-derived APOE is implicated in lipid transport during

oxidative stress, collectively contributing to the maintenance of

lipid metabolic equilibrium and neurological function in the brain

(117).

Microglia serve as the principal immune cells within

the CNS, playing a crucial role in the clearance of cellular debris

and the modulation of neuroinflammation. A substantial body of

research suggests that the activation of microglia and their

interactions with astrocytes significantly influence the

inflammatory processes associated with NDDs and brain injury

(9,118,119). Under stress conditions,

including oxidative stress, inflammation and aging, the phagocytic

activity and inflammatory responses of microglia may contribute to

LD accumulation in the brain. This process is predominantly

regulated by the TLR4 and nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of

nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathways. LPS, functioning as

TLR4 ligands, initiate the TLR4 signaling cascade, subsequently

activating downstream signaling molecules such as myeloid

differentiation factor 88 and Toll/IL-1 receptor-domain-containing

adapter-inducing interferon (IFN)-β, and facilitating the formation

of LDs within microglia (120).

The substantial accumulation of LDs in microglia may result from

enhanced lipid synthesis coupled with diminished lipid catabolism.

Fatty acids stored in microglial LDs can be mobilized through the

enzymatic activity of two lipases, ATGL and HSL, when required for

stress responses, thereby contributing to metabolic processes or

inflammatory reactions (121).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs)

and NF-κB transcription factors are integral to lipid metabolism

and inflammatory responses. The activation of TLR4 can further

stimulate the NF-κB signaling pathway, resulting in substantial

production of inflammatory cytokines and the onset of

neuroinflammation. Research has identified a strong association

between the accumulation of LDs in microglia and the dysfunction of

the aging brain, as well as the establishment of a pro-inflammatory

state. Astrocytes promote phagocytic activity in microglia by

secreting cytokines. When microglia undergo metabolic changes

characterized by LD accumulation, phagocytosis becomes impaired.

This process is often regarded as an inflammatory marker involved

in NDDs, thereby accelerating neuronal degeneration (122). This accumulation is

significantly implicated in the pathogenesis of various

neuroinflammatory and NDDs. Evidence suggests that LD accumulation

in microglia within the aging mouse brain can induce the production

of ROS and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby

contributing to neurodegeneration (122). In AD, both postmortem brain

tissue from patients with AD and AD mouse models demonstrate that

amyloid β (Aβ) deposition and hyperphosphorylated tau protein can

activate microglia, leading to chronic inflammation and

neurodegeneration (123). In

PD, studies using human induced pluripotent stem cell

(iPSC)-derived astrocyte models (carrying the APOE4 genotype) and

APOE-targeted replacement mouse brain tissue models reveal that the

degeneration of dopaminergic neurons activates microglia, which

release inflammatory mediators that further damage the remaining

neurons (124). Thus,

microglial activation is a critical factor in the development of

neuroinflammation and NDDs.

Lipid metabolism plays a crucial role in modulating

inflammation and neuroprotection by regulating LD formation and

fatty acid release. As research progresses, genome-wide

transcriptome analyses have elucidated that the human-specific

variant APOE4 disrupts lipid metabolism in astrocytes and microglia

(125). This disruption

elucidates how APOE4-induced dysregulation, both cell-autonomous

and non-cell-autonomous, may elevate the risk of AD. Studies have

demonstrated that the activation of microglia in a male rat spinal

cord injury model can stimulate astrocytes to secrete and release

increased levels of lipocalin 2 (LCN2), resulting in neuronal

damage and extensive neuronal loss within the CNS (126,127). Glial cells exhibit distinct

interactions in lipid metabolism. Aβ-exposed astrocytes secrete

LCN2, which activates the pro-inflammatory function of microglia

and further stimulates astrocytes to secrete and release higher

levels of LCN2 in a bidirectional manner (128). Research indicates that reducing

LCN2 levels can diminish the activation of neurotoxic α1-subtype

astrocytes, offering a more effective pathway for preventing

neuronal cell death (129).

Microglia bridge the gap between lipid dysregulation and

neurodegeneration in PD by sensing metabolic disturbances. Oxidized

lipids and glycosphingolipids activate microglia, which in turn

promote A1-type astrocyte activation through inflammatory cytokine

release, further accelerating PD progression (130). Therefore, modulating the lipid

metabolism interaction pathway between these cells holds promise

for achieving precise interventions against various NDDs.

Furthermore, another research group has highlighted the significant

role of BTB and CNC homolog 1 (BACH1) in maintaining metabolic

homeostasis in microglia during mouse brain development (131). BACH1 influences microglial

metabolism by inhibiting key glycolytic enzymes, hexokinase 2 and

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, thereby reducing lactate

production. This metabolic alteration leads to a decrease in

lactate-dependent histone modifications at the leucine rich repeat

containing 15 (LRRC15) promoter region, consequently affecting the

expression of the LRRC15 gene. LRRC15 is a factor secreted by

microglia, which participates in the JAK/STAT signaling pathway by

binding to the CD248 receptor and regulates astrocyte generation

(131).

The brain primarily relies on glucose for its energy

requirements and lacks alternative forms of energy storage, except

for glycogen present in astrocytes. During conditions such as

starvation, the brain can utilize ketone bodies (KB), which are

derived from the breakdown of fatty acids in the liver, to meet the

energy demands of central neurons. Recent research has identified

that cortical glial cells in the fruit fly brain can synthesize KB

from their own stored LDs and subsequently transport these to

neurons via monocarboxylate transporters for energy provision

(132). Oligodendrocytes, in

addition to their role in myelin formation, contribute to the

energy metabolism of axons by supplying pyruvate and lactate. A

recent study highlighted that the interaction between astrocytes

and oligodendrocytes is crucial for myelin regeneration (133). Persistent activation of the

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway in

astrocytes has been shown to inhibit the cholesterol biosynthesis

pathway, consequently impairing myelin regeneration. The experiment

demonstrated in a mouse model of focal demyelination that

activation of Nrf2 in astrocytes results in the suppression of the

cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, consequently impairing myelin

regeneration (133). In the

CNS, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes collaborate, particularly in

lipid metabolism and the maintenance of myelin, to ensure efficient

nerve conduction. Astrocytes supply oligodendrocytes with essential

lipids, including cholesterol and phospholipids, which are crucial

for myelination. Astrocytes supply lipids to oligodendrocytes via

an SREBP2-dependent pathway to regulate myelin

maintenance/regeneration. Under the regulation of the key

transcription factor SREBP2, astrocytes synthesize large amounts of

cholesterol through their own mevalonate pathway and transport it

to oligodendrocytes via lipoproteins such as APOE. Research

confirms that SREBP controls gene transcription in the cholesterol

biosynthesis pathway, enhancing cholesterol synthesis when SREBP2

is overexpressed (134). By

contrast, phospholipids and fatty acids are conveyed through

vesicular and protein-mediated mechanisms, as well as via

lipoproteins and FABPs. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism can lead

to myelin damage and neurodegeneration (135).

The heterogeneity of astrocyte responses in CNS

pathology involves the roles of astrocytes and recruited peripheral

cells in facilitating disease progression. Research indicates that

in postmortem brain tissue from patients with ischemic stroke and

in mouse models of transient focal cerebral ischemia, astrocytes

express IL-15 upon stimulation. This factor recruits CD8+ T cells

during brain injury and enhances their effector functions (136). Notably, the interaction between

astrocytes and T cells is reciprocal; T cells can also influence

astrocyte responses. Astrocytes express receptors for IL-17 and

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF),

cytokines produced by pro-inflammatory T helper 17 (Th17) cells,

which are implicated in the pathologies of multiple sclerosis (MS),

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), and other

diseases. Initial findings from in vivo mouse experimental

autoimmune EAE models and in vitro primary mouse astrocyte

models suggested that IL-17 derived from Th17 cells upregulates the

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines GM-CSF and C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand 1, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 and C-C motif

chemokine ligand 20 in an NF-κB activator 1-dependent manner,

thereby promoting leukocyte recruitment to the CNS during EAE

(137,138). Recently, it has been reported

that IFN-γ produced by natural killer (NK) cells can induce

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand expression in syngeneic

astrocytes, enabling pro-inflammatory T cells expressing death

receptor 5 to undergo apoptosis (137,139). Notably, NK cells acquire the

ability to produce IFN-γ in intestinal tissues through the

meningeal circulation in response to signals provided by the

commensal microbiota (140).

These findings identify mechanisms of the gut-CNS axis for

controlling inflammation, which not only reveal the potential role

of the microbiota in the pathologies of neurological diseases but

also provide promising targets for therapeutic intervention.

Astrocyte-derived lipid metabolites play a crucial

role in modulating the activation and differentiation of immune

cells, including T cells and B cells, and in safeguarding neurons

against oxidative stress by activating antioxidant pathways, such

as the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Empirical evidence indicates that

disruptions in astrocytic lipid metabolism can initiate neuroimmune

responses and contribute to the pathogenesis of NDDs (82). Notably, through specific knockout

of genes encoding key components of OXPHOS mitochondrial

dysfunction in mouse astrocytes results in the abnormal

accumulation of LDs within the hippocampus, which subsequently

activates both astrocytes and microglia, thereby eliciting a

neuroimmune response (82). This

aberration in lipid metabolism has also been observed in AD model

mice, implying a potential link between lipid metabolic

disturbances in AD and dysfunctional mitochondrial activity in

astrocytes.

Cell senescence refers to the state where cells

enter an irreversible non-dividing state after undergoing a certain

number of divisions, preventing the excessive proliferation of

damaged cells and inhibiting the occurrence of pathological

reactions (141) such as

cancer. Certain studies have found that glial cells with high

activating protein 1 (AP-1) activity have abnormal morphology,

produce matrix metalloproteinases and promote tau-related aging

pathological reactions (20,142). However, the mechanism of

senescent glial cell generation and how they affect neuronal

senescence remain elusive.

Recent studies have elucidated the origin of

senescent glial cells characterized by abnormally elevated AP-1

activity and their influence on neuronal aging (20,143). It has been discovered that

mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons initiates the formation of

senescent glial cells, which subsequently induce the excessive

accumulation of LDs in non-senescent glial cells. Under chronic

oxidative stress conditions (such as persistent mitochondrial

damage), the excessive accumulation of LDs observed in AD mouse

models becomes maladaptive, impairing phagocytic function and

promoting tau protein aggregation. Chronic inflammation and lipid

metabolism disorders activate inflammatory signaling pathways, such

as NF-κB and MAPK, thereby enhancing the production of inflammatory

mediators and exacerbating neuronal aging. In addition, lipid

metabolites adversely affect mitochondrial function, resulting in

dysfunction and further accelerating neuronal aging.

Abnormal LDs in astrocytes are critical initiators

of NDDs, including AD, PD and ALS. In AD, dysregulated lipid

metabolism impairs Aβ clearance and inflammatory responses, leading

to Aβ accumulation, neuroinflammation and increased neuronal injury

(115). In PD, impaired lipid

metabolism disrupts dopaminergic neurons, accelerating disease

progression. Similarly, in ALS, studies of postmortem spinal cord

tissue from patients and ALS mouse models reveal that astrocyte

dysmetabolism contributes to inflammation and neuronal death, with

aberrant LDs accumulation enhancing ROS production and exacerbating

neuronal damage (144). The

accumulation of glial cell LDs is a prominent feature in motor

neuron diseases such as ALS and may be prevalent across various

NDDs (145). Astrocytic lipid

metabolism is intricately linked to neuronal function, and

oxidative stress can induce LD formation, thereby accelerating

neurodegenerative processes. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism in

astrocytes has been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders,

affecting neuronal activity regulation, neurotransmitter release

and synaptic pruning processes. Astrocytes facilitate synaptic

pruning through interactions with microglia during developmental

stages. For instance, astrocytes promote synaptic pruning during

development through an IL-33-mediated mechanism related to

microglia-dependent synaptic pruning (146,147). In addition, the complement

produced by astrocytes in an acute epilepsy mouse model has been

shown to trigger microglia-dependent pruning to reshape neural

circuits (148) (Fig. 1).

The formation of LDs in the brains of AD mouse

models is intricately linked to processes such as inflammation,

oxidative stress and aging. A reduction in the OXPHOS capacity of

astrocytes adversely affects the lipid distribution, leading to

issues such as synaptic loss, altered astrocyte reactivity and

heightened oxidative stress (82). These factors are critical

contributors to neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction.

Various alleles of APOE, including E2 and E3, exhibit

neuroprotective effects, in contrast to the APOE4 allele, which is

a significant genetic risk factor for AD. Previous studies have

demonstrated that PLIN3, possessing apolipoprotein-like

characteristics, promotes the conversion of liposomes into lipid

rafts. This membrane remodeling function is attributed to the

C-terminal (quadruple helix bundle) domain of PLIN3. The C-terminal

region of PLIN3 shares homology with the N-terminal domain of APOE,

which is known to promote small LD formation. This domain binds to

PLIN3 via a hydrophobic cleft, jointly regulating LD transport and

facilitating droplet-lysosome contact (59,149). This interaction provides a

potential therapeutic target for developing strategies to address

NDDs by specifically modulating the interaction between APOE4 and

LD regulatory proteins. APOE4 affects lipid transfer ability and

reduces the production of LDs. In glial cells expressing APOE4,

there is an increase in LDs, and functional deletion of APOE4

results in fewer lipoprotein particles and lipid accumulation in

astrocytes (150). APOE4 is

characterized by low lipid-binding capacity, reduced protein

stability and diminished affinity for brain lipoprotein particles.

Neuronal lipid transport proteins such as ABCA1 (151) and ABCA7 (152), LRP1 (153), and genes related to endocytosis

are associated with an elevated risk of AD. Astrocytes produce

cytokines that are associated with depression and anxiety-like

behaviors. For instance, adenosine signaling in amygdala astrocytes

promotes anxiety-related phenotypes in regionally and synaptically

specific ways (154). Targeting

astrocyte cytokine production may provide new treatment options for

depression and related disorders. The accumulation of LDs in

astrocytes has the potential to activate inflammatory signaling

pathways, thereby exacerbating neuroinflammation. This process can

disrupt normal metabolic functions, resulting in energy

deficiencies and abnormalities in metabolite production, which may

exert neurotoxic effects. Furthermore, the accumulation of LDs in

astrocytes is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and can

compromise protein quality control mechanisms, leading to the

accumulation of misfolded proteins and the induction of apoptosis

or necrosis (90). In the early

stages of AD, lipid imbalances and LD accumulation are particularly

pronounced in astrocytes of individuals carrying the APOE4 allele,

who exhibit increased LD accumulation and diminished fatty acid

uptake and oxidation (155).

These phenomena have been confirmed in postmortem brain tissue from

APOE4 carriers and in APOE4 mouse models. Additionally, neuronal

mitochondrial abnormalities that contribute to astrocytic LD

accumulation, as observed in a mouse model of Leigh syndrome with

mitochondrial dysfunction, may represent an early indicator of

neurodegeneration (156).

While the brain primarily utilizes glucose as its

main energy source, lipids play a crucial structural and functional

role in brain activity. Given that excessive FFAs are linked to

lipid toxicity, their concentrations must be meticulously

regulated. Research indicates that OXPHOS in astrocytes is

essential for the catabolism of fatty acids, thereby maintaining

lipid homeostasis (82). A

deficiency in astrocytic OXPHOS can lead to significant damage to

brain lipid structures and activate several critical pathological

mechanisms. These mechanisms include synaptic loss and dysfunction,

reactive astrocyte dysfunction, reactive astrogliosis, microglial

activation, oxidative stress and demyelination. Collectively, these

pathological processes contribute to neuroinflammation,

neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment (157). Consequently, strategies aimed

at preserving or restoring the equilibrium between fatty acid load

and mitochondrial catabolism hold promise for mitigating reactive

astrocyte hyperplasia. Furthermore, such strategies may enhance the

adverse cerebral environment and ameliorate cognitive deficits.

This represents a potentially promising avenue for future research

(Table I).

Astrocytes play a crucial role in maintaining the

normal functioning of the nervous system and safeguarding it

against diseases. The pathophysiology of astrocytes is intricate,

highly heterogeneous and variable, with responses that can differ

based on the specific contexts and environments associated with

disease. Any form of brain injury elicits an astrocytic response

aimed at preserving or restoring homeostasis. In cases of severe

injury, reactive astrogliosis is initiated, which serves to protect

the surrounding neural tissue. A significant mechanism underlying

neurological dysfunction in most neurological disorders is the loss

of astrocytic function. Although the role of lipids in the

distribution of brain regions and NDDs has not been fully

elucidated, advancements in single-cell sequencing technology and

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry

imaging mass spectrometry have enabled the direct detection of

intramembranous LDs and lipid metabolism (158).

The impairment of astrocyte function can result in

the accumulation of detrimental lipid metabolism byproducts and the

progressive loss of neuronal support functions. While there are

currently no specific therapies or drugs that directly target

astrocyte LD storage and lipid metabolism, numerous pharmacological

agents are known to influence astrocyte reactivity and

astroglia-neuron interactions. Observations in adult mouse fasting

models revealed elevated lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) levels in

blood/cerebrospinal fluid following fasting. Upon crossing the BBB

into the cortex, LPA increased cortical neuronal excitability

(159). In a mouse model of

ischemic stroke induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion,

autotaxin (ATX) and LPA levels significantly increased in the

cortex, leading to sustained glutamate-mediated hyperexcitability.

However, when mice were genetically engineered to specifically

knockout ATX or when ATX was pharmacologically inhibited, LPA

levels decreased, the cortical excitatory/inhibitory balance was

restored and neurological function improved (153). Research has demonstrated that

ATX, an enzyme responsible for LPA synthesis and expressed by

astrocytes in excitatory synaptic regions, can modulate glutamate

transmission and is itself regulated by neuronal activity (160). This model proposes that

pharmacologically inhibiting ATX through indirect mechanisms of

neurotransmission may offer a novel therapeutic approach for

neurological disorders such as schizophrenia. Enhancing the

catabolic pathways and mobilizing internal energy reserves can

improve the bioenergetic efficiency of astrocytes and their

capacity to support neurons under stress, representing a promising

metabolic therapeutic strategy. Supplementation with omega-3

polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as DHA, has been demonstrated to

mitigate astrocyte activation and inflammatory responses by

inhibiting inflammatory signaling pathways like NF-κB and AP-1,

enhancing cell membrane fluidity and thereby indirectly improving

astrocyte function (161,162). However, large-scale human

clinical trials have yielded inconsistent results regarding

cognitive enhancement, suggesting that efficacy may depend on

disease stage and APOE genotype. The PPAR-δ agonist GW0742 has

demonstrated potential therapeutic efficacy in preclinical models

of AD by promoting fatty acid β-oxidation capacity in astrocytes

and directly reducing LD accumulation (163). It has been observed to enhance

CPT1A expression and fatty acid oxidation capacity in iPSC-derived

astrocytes from fatty acid oxidation-deficient patients with AD, as

well as to improve memory, increase neurogenesis and reduce

inflammation-related gene expression in Aβ precursor

protein/presenilin 1 AD mouse models. GW0742 can also significantly

reduce BBB leakage and metalloproteinase-9 expression, while

upregulating tight junction protein expression, reducing neutrophil

recruitment to the brain and protecting BBB integrity (164). Nonetheless, GW0742 does not

prevent the pro-inflammatory activation of iPSCs or astrocyte

proliferation and may be insufficient to fully reverse metabolic

damage, particularly in the context of glucose metabolism

deficiencies, which could lead to uncoupled mitochondrial

respiration and elevated oxidative stress (163). However, due to variations in

APOE genotypes, the effects may differ, and this potential risk has

not yet been fully evaluated. Glucose metabolism modulators can

correct the metabolic reprogramming of astrocytes, thereby

significantly reducing the expression of proinflammatory factors

such as TNF-α and IL-6 in IL-1β-stimulated astrocytes (165). In the future, the combination

of 'GW0742 combined with glucose metabolism modulator' holds

promise for reshaping astrocytes into a neuroprotective phenotype.

This approach may positively and indirectly enhance their glutamate

transport function and BBB maintenance capacity, thereby improving

therapeutic outcomes for NDDs. Similarly, liver X receptor (LXR)

agonists can significantly attenuate tau pathology and

neurodegeneration in APOE4 mice by promoting lipid efflux in

astrocytes. These data suggest that enhancing glial lipid efflux

may serve as a therapeutic approach to improve tau and

APOE4-associated neurodegeneration. However, most non-selective LXR

agonists strongly induce lipogenic genes such as SREBP-1c and fatty

acid synthase in the liver, leading to hypertriglyceridemia and

hepatic steatosis (166).

Therefore, the beneficial effects of LXR agonists in AD models must

be weighed against their known systemic side effects. Long-term

regulation of cellular LDs is not without risk. Multiple studies

indicate that inhibiting LD formation weakens the detoxification

capacity of glial cells under acute oxidative stress. Research

reveals that endogenous tau deficiency impairs LD formation in

astrocytes, leading to elevated lipid peroxides, enhanced ROS

production and increased cellular sensitivity to neurotoxicity

(167). Similarly, studies on

glioblastoma indicate that targeted inhibition of DGAT1 disrupts

lipid homeostasis, exacerbating oxidative stress and increasing

cell mortality, suggesting the critical role of LDs in buffering

lipotoxicity (168). Therefore,

future interventions should not simply aim to 'reduce LDs' but

rather focus on restoring lipid homeostasis.

A significant challenge in developing therapies

targeting astrocytes lies in the heterogeneity of these cells in

both healthy and diseased states. Astrocyte subpopulations exhibit

considerable variability in their distribution across different

regions of the CNS, as well as in their roles in various diseases

or disease states. Notably, certain pathogenetic mechanisms

associated with astrocytes are prevalent across numerous

neurological disorders. These mechanisms include neurotoxicity,

dysregulation of extracellular glutamate levels, defects in

potassium ion cycling and impaired lactate shuttling (169). Modulating these commonly

dysregulated pathways in astrocyte activity may offer therapeutic

targets for a range of neurological diseases that are influenced by

astrocytic dysfunction.

Astrocytes are integral to the CNS, where they

contribute to the maintenance of the BBB, facilitate intercellular

communication and uphold metabolic homeostasis. The lipid

metabolism of astrocytes is essential for preserving membrane

fluidity, mitigating inflammation, and influencing the structure

and signaling of organelles. The interplay of these metabolic

pathways is crucial for the metabolic equilibrium of the nervous

system; disruptions in these pathways can result in disorders of

energy production, inflammation, excitotoxicity and the

accumulation of toxic substances, all of which are common causative

factors in various NDDs (170,171). A comprehensive understanding of

these pathways in both health and disease contexts can elucidate

the underlying causes of such diseases and provide a foundation for

the development of novel therapeutic and nutritional strategies

aimed at enhancing patient outcomes. In various disease contexts, a

range of emerging astrocyte-related molecules may serve as

potential therapeutic targets. Consequently, treatment strategies

should focus on modulating specific molecules involved in astrocyte

responses to bolster astrocyte defense mechanisms and improve

astrocyte homeostasis, ultimately addressing CNS diseases through

pathophysiological interventions.

Not applicable.

YKZ and CCZ contributed to the overall

conceptualization of the review. YCW, BXW and JCH drafted and

revised the manuscript. XDH, CLL and RLG generated the figures.

HGC, YZ and JBZ edited the manuscript and figures. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation

of China (grant nos. 82302116, 82020108026 and 82404215), Shaanxi

Outstanding Youth Fund Project (grant no. 2023-JC-JQ-65) and the

Fourth Military Medical University pilotage operation new flight

program project (grant no. 2023-rcjfzyk).

|

1

|

Rudnicka E, Napierala P, Podfigurna A,

Meczekalski B, Smolarczyk R and Grymowicz M: The world health

organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 139:6–11.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch

SG, Croteau DL and Bohr VA: Ageing as a risk factor for

neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 15:565–581. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wilson DM III, Cookson MR, Van Den Bosch

L, Zetterberg H, Holtzman DM and Dewachter I: Hallmarks of

neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. 186:693–714. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dugger BN and Dickson DW: Pathology of

neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

9:a0280352017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bhat MA and Dhaneshwar S:

Neurodegenerative diseases: New hopes and perspectives. Curr Mol

Med. 24:1004–1032. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Temple S: Advancing cell therapy for

neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Stem Cell. 30:512–529. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Singh K, Sethi P, Datta S, Chaudhary JS,

Kumar S, Jain D, Gupta JK, Kumar S, Guru A and Panda SP: Advances

in gene therapy approaches targeting neuro-inflammation in

neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 98:1023212024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Shi FD and Yong VW: Neuroinflammation

across neurological diseases. Science. 388:eadx00432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kwon HS and Koh SH: Neuroinflammation in

neurodegenerative disorders: The roles of microglia and astrocytes.

Transl Neurodegener. 9:422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Guttenplan KA, Weigel MK, Prakash P,

Wijewardhane PR, Hasel P, Rufen-Blanchette U, Munch AE, Blum JA,

Fine J, Neal MC, et al: Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes induce cell

death via saturated lipids. Nature. 599:102–107. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cameron EG, Nahmou M, Toth AB, Heo L,

Tanasa B, Dalal R, Yan W, Nallagatla P, Xia X, Hay S, et al: A

molecular switch for neuroprotective astrocyte reactivity. Nature.

626:574–582. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

12

|

Debom GN, Rubenich DS and Braganhol E:

Adenosinergic signaling as a key modulator of the glioma

microenvironment and reactive astrocytes. Front Neurosci.

15:6484762021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Acioglu C, Li L and Elkabes S:

Contribution of astrocytes to neuropathology of neurodegenerative

diseases. Brain Res. 1758:1472912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kozachkov L, Kastanenka KV and Krotov D:

Building transformers from neurons and astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 120:e22191501202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yamagata K: Lactate supply from astrocytes

to neurons and its role in ischemic stroke-induced

neurodegeneration. Neuroscience. 481:219–231. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Tewari BP, Woo AM, Prim CE, Chaunsali L,

Patel DC, Kimbrough IF, Engel K, Browning JL, Campbell SL and

Sontheimer H: Astrocytes require perineuronal nets to maintain

synaptic homeostasis in mice. Nat Neurosci. 27:1475–1488. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Aldana BI, Zhang Y, Jensen P,

Chandrasekaran A, Christensen SK, Nielsen TT, Nielsen JE, Hyttel P,

Larsen MR, Waagepetersen HS and Freude KK: Glutamate-glutamine

homeostasis is perturbed in neurons and astrocytes derived from

patient ipsc models of frontotemporal dementia. Mol Brain.

13:1252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Qian K, Jiang X, Liu ZQ, Zhang J, Fu P, Su

Y, Brazhe NA, Liu D and Zhu LQ: Revisiting the critical roles of

reactive astrocytes in neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry.

28:2697–2706. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yin F: Lipid metabolism and Alzheimer's

disease: Clinical evidence, mechanistic link and therapeutic

promise. FEBS J. 290:1420–1453. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Byrns CN, Perlegos AE, Miller KN, Jin Z,

Carranza FR, Manchandra P, Beveridge CH, Randolph CE, Chaluvadi VS,

Zhang SL, et al: Senescent glia link mitochondrial dysfunction and

lipid accumulation. Nature. 630:475–483. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nakamura A, Sakai S, Taketomi Y, Tsuyama

J, Miki Y, Hara Y, Arai N, Sugiura Y, Kawaji H, Murakami M and

Shichita T: PLA2G2E-mediated lipid metabolism triggers

brain-autonomous neural repair after ischemic stroke. Neuron.

111:2995–3010 e9. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chausse B, Kakimoto PA and Kann O:

Microglia and lipids: How metabolism controls brain innate

immunity. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 112:137–144. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Duquenne M, Folgueira C, Bourouh C, Millet

M, Silva A, Clasadonte J, Imbernon M, Fernandois D, Martinez-Corral

I, Kusumakshi S, et al: Leptin brain entry via a tanycytic

LepR-EGFR shuttle controls lipid metabolism and pancreas function.

Nat Metab. 3:1071–1090. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mathiowetz AJ and Olzmann JA: Lipid

droplets and cellular lipid flux. Nat Cell Biol. 26:331–345. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ralhan I, Chang CL, Lippincott-Schwartz J

and Ioannou MS: Lipid droplets in the nervous system. J Cell Biol.

220:e2021021362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mallick K, Paul S and Banerjee S and

Banerjee S: Lipid droplets and neurodegeneration. Neuroscience.

549:13–23. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Windham IA, Powers AE, Ragusa JV, Wallace

ED, Zanellati MC, Williams VH, Wagner CH, White KK and Cohen S:

Apoe traffics to astrocyte lipid droplets and modulates

triglyceride saturation and droplet size. J Cell Biol.

223:e2023050032024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Smolic T, Tavcar P, Horvat A, Cerne U,

Haluzan Vasle A, Tratnjek L, Kreft ME, Scholz N, Matis M, Petan T,

et al: Astrocytes in stress accumulate lipid droplets. Glia.

69:1540–1562. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kim NS and Chung WS: Astrocytes regulate

neuronal network activity by mediating synapse remodeling. Neurosci

Res. 187:3–13. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

de Ceglia R, Ledonne A, Litvin DG, Lind

BL, Carriero G, Latagliata EC, Bindocci E, Di Castro MA, Savtchouk

I, Vitali I, et al: Specialized astrocytes mediate glutamatergic

gliotransmission in the CNS. Nature. 622:120–129. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Liu D, Liao P, Li H, Tong S, Wang B, Lu Y,

Gao Y, Huang Y, Zhou H, Shi L, et al: Regulation of blood-brain

barrier integrity by dmp1-expressing astrocytes through

mitochondrial transfer. Sci Adv. 10:eadk29132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jayaram MA and Phillips JJ: Role of the

microenvironment in glioma pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol.

19:181–201. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Giovannoni F and Quintana FJ: The role of

astrocytes in CNS inflammation. Trends Immunol. 41:805–819. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hou J, Bi H, Ge Q, Teng H, Wan G, Yu B,

Jiang Q and Gu X: Heterogeneity analysis of astrocytes following

spinal cord injury at single-cell resolution. FASEB J.

36:e224422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen ZP, Wang S, Zhao X, Fang W, Wang Z,

Ye H, Wang M, Ke L, Huang T, Lv P, et al: Lipid-accumulated

reactive astrocytes promote disease progression in epilepsy. Nat

Neurosci. 26:542–554. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Veiga A, Abreu DS, Dias JD, Azenha P,

Barsanti S and Oliveira JF: Calcium-dependent signaling in

astrocytes: Downstream mechanisms and implications for cognition. J

Neurochem. 169:e700192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Iovino L, Tremblay ME and Civiero L:

Glutamate-induced excitotoxicity in Parkinson's disease: The role

of glial cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 144:151–164. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fang Y, Ding X, Zhang Y, Cai L, Ge Y, Ma

K, Xu R, Li S, Song M, Zhu H, et al: Fluoxetine inhibited the

activation of a1 reactive astrocyte in a mouse model of major

depressive disorder through astrocytic 5-HT(2b)R/β-arrestin2

pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 19:232022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chen Z, Yuan Z, Yang S, Zhu Y, Xue M,

Zhang J and Leng L: Brain energy metabolism: Astrocytes in

neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther. 29:24–36. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

40

|

Cheng X, Zhao M, Chen L, Huang C, Xu Q,

Shao J, Wang HT, Zhang Y, Li X, Xu X, et al: Astrocytes modulate

brain phosphate homeostasis via polarized distribution of phosphate

uptake transporter PiT2 and exporter XPR1. Neuron.

112:3126–3142.e8. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sharma V, Oliveira MM, Sood R, Khlaifia A,

Lou D, Hooshmandi M, Hung TY, Mahmood N, Reeves M, Ho-Tieng D, et

al: mRNA translation in astrocytes controls hippocampal long-term

synaptic plasticity and memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120:e23086711202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Guo F, Fan J, Liu JM, Kong PL, Ren J, Mo

JW, Lu CL, Zhong QL, Chen LY, Jiang HT, et al: Astrocytic alkbh5 in