Introduction

Proteins are fundamental components of cells and

form the essential material basis for sustaining and regulating

life processes. Disturbances in protein abundance, folding,

function or localization can disrupt physiological homeostasis,

underscoring the importance of maintaining protein homeostasis, or

proteostasis (1,2). Proteostasis is maintained by a

highly coordinated network of quality control mechanisms that

regulate protein synthesis, folding, modification, trafficking and

degradation, thereby ensuring the stability and functionality of

the proteome (3). When this

delicate balance is perturbed by genetic mutations, environmental

stress or aging, misfolded and aggregated proteins accumulate,

driving proteotoxic stress, organelle dysfunction and, ultimately,

disease (4). Proteostasis

collapse has been recognized as a unifying driver of diverse human

disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases, malignancies,

cardiovascular dysfunction and metabolic syndromes.

Against this backdrop, FK506-binding proteins

(FKBPs) have emerged as particularly intriguing regulators of

proteostasis. FKBPs are members of the immunophilin family, which

also comprises cyclophilins that share conserved peptidyl-prolyl

cis-trans isomerase activity but differ in structural domains and

functional specialization. Defined by a conserved peptidyl-prolyl

cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) domain and diversified by additional

modules conferring organelle targeting and chaperone interactions,

FKBPs extend far beyond their classical role as

immunosuppressant-binding proteins (5-7).

Increasing evidence shows that they actively shape proteostasis

networks by accelerating conformational maturation, scaffolding

protein complexes, modulating stress responses and directing

selective degradation, positioning them as key molecular links

between proteostasis regulation and disease pathogenesis (8-12).

Despite substantial progress in characterizing

individual FKBPs, no review has systematically integrated their

diverse roles in proteostasis regulation across multiple disease

contexts, yet, to the best of our knowledge. This article provides

the first unified framework, linking FKBP structure to proteostatic

function and disease relevance. In cancer, FKBPs adjust

translation, folding and degradation pathways to sustain the high

protein load of malignant cells, driving proteome remodeling and

tumor progression (13). In

neurodegenerative diseases, FKBPs influence the conformational fate

of pathogenic proteins by regulating folding and aggregation

processes, thereby determining neuronal survival and function

(14). In cardiovascular

disease, FKBPs stabilize the conformation of ion channel complexes

to preserve calcium signaling homeostasis, ensuring precise cardiac

contraction and electrical activity (15). In metabolic regulation, they act

as scaffolds to fine-tune kinase phosphorylation, integrating

energy sensing with metabolic signaling to maintain systemic

balance (16). These functions

not only underscore the multifaceted role of FKBPs as central

regulators of proteostasis but also establish them as critical

bridges linking proteostatic regulation to disease mechanisms. The

present study proposes targeting FKBPs as a novel target to correct

proteostasis imbalance and halt disease progression, thereby

opening new avenues for precision therapies across multiple organ

systems.

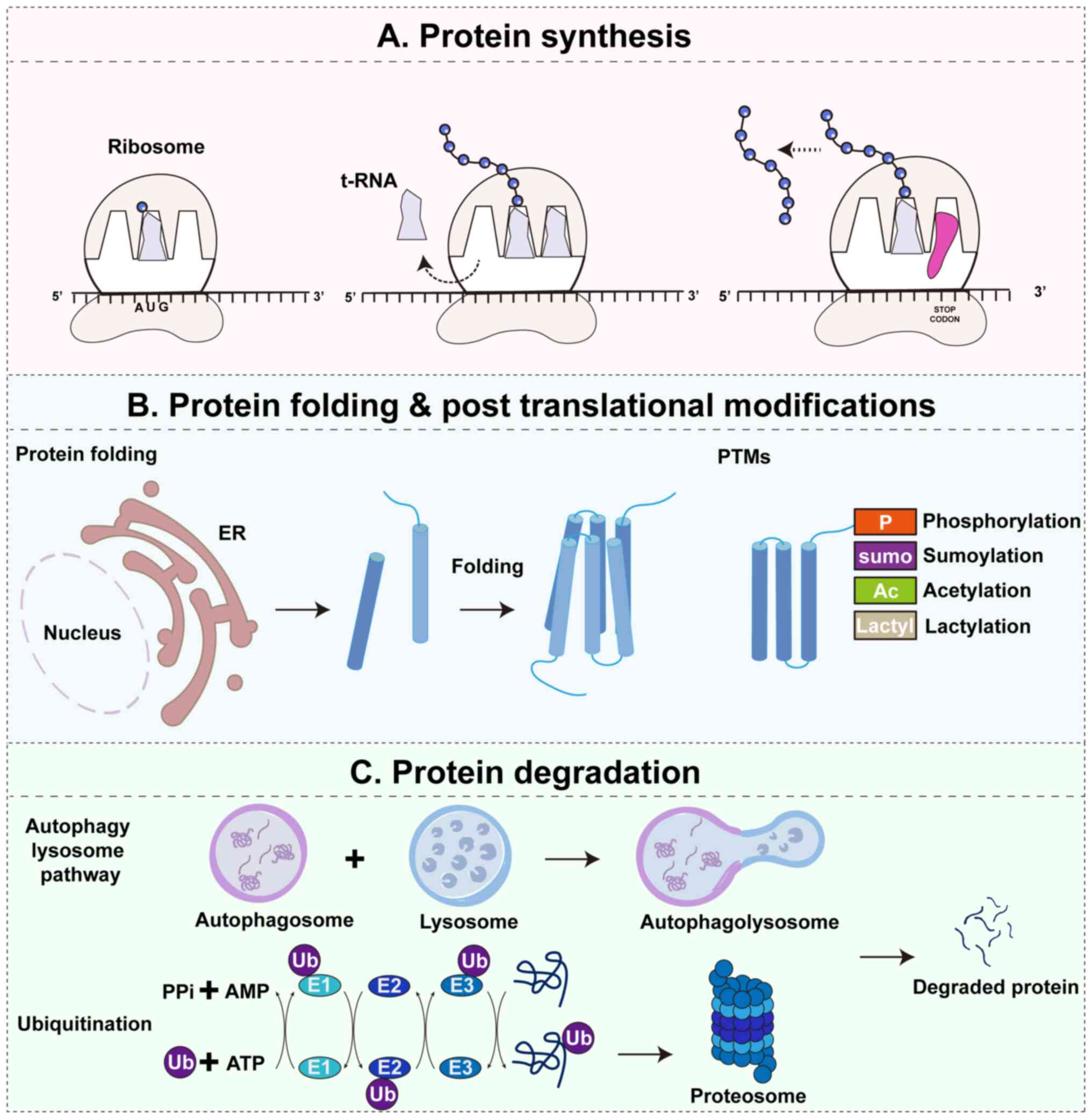

Overview of proteostasis

Proteostasis is the cellular process that maintains

a dynamic balance of protein synthesis, folding, modification,

trafficking, and degradation, ensuring proteins remain in the

proper quantity and functional conformation (8). Its core mechanisms are tightly

coordinated. Proteins are synthesized on ribosomes as nascent

polypeptides that are often unstable or partially folded, requiring

molecular chaperones and foldases for correct folding or assembly

into multimeric complexes (Fig.

1A). Before becoming functionally active, many proteins undergo

post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation,

acetylation, or ubiquitination, which regulate their stability,

activity, and interactions (Fig.

1B). Proteins must also be directed with precision to

organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria, or

nucleus to execute specific functions. When proteins misfold,

become damaged, or accumulate abnormally, two major degradation

systems maintain quality control: the ubiquitin-proteasome system

(UPS), which removes short-lived and defective proteins, and the

autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP), which clears protein aggregates

and damaged organelles. Together, these mechanisms uphold the

dynamic equilibrium of the proteome (1,17).

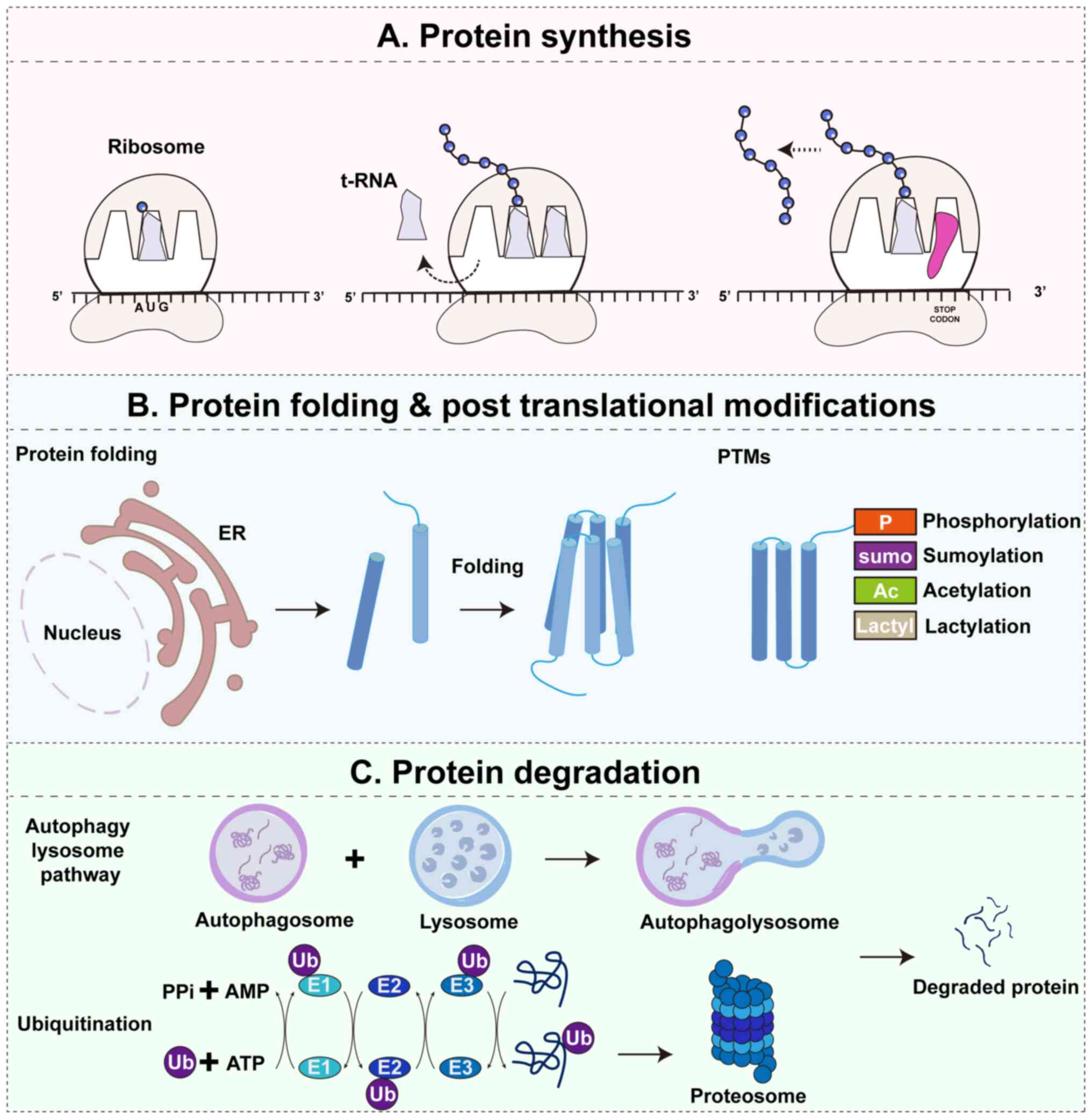

| Figure 1Overview of proteostasis and its core

pathways. Proteostasis is maintained through a dynamic balance of

protein synthesis, folding and post-translational modifications,

and degradation. (A) Protein synthesis. Ribosomes translate mRNA

into nascent polypeptide chains, which often require assistance

from molecular chaperones and foldases to achieve stable

structures. (B) Protein folding and post-translational

modifications. Newly synthesized proteins fold in the ER and

undergo PTMs, such as phosphorylation, sumoylation, acetylation and

lactylation, which regulate protein stability, activity and

interactions. (C) Protein degradation. Misfolded, damaged or

surplus proteins are eliminated through two major pathways: The

UPS, where substrates are sequentially ubiquitinated by E1, E2 and

E3 enzymes and degraded by the 26S proteasome into peptides; and

the ALP, where cytoplasmic substrates, including protein aggregates

and damaged organelles, are sequestered into autophagosomes, fused

with lysosomes and degraded into reusable biomolecules. Together,

these pathways establish a quality control cycle that preserves

proteome integrity and cellular homeostasis under both

physiological and stress conditions. P, phosphorylation; sumo,

sumoylation; Ac, acetylation; Lactyl, lactylation; UPS,

ubiquitin-proteasome system; ALP, autophagy-lysosome pathway; E1,

ubiquitin-activating enzyme; E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; E3,

ubiquitin ligase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; AMP, adenosine

monophosphate; PPi, inorganic pyrophosphate; PTMs,

post-translational modifications; Ub, ubiquitin. |

The UPS primarily eliminates short-lived or

misfolded monomeric proteins. Substrates are first tagged with

ubiquitin chains through a cascade involving E1 activating enzymes,

E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases. These ubiquitinated proteins

are then directed to the 26S proteasome, where they are unfolded

and degraded into short peptides, allowing rapid protein turnover

and removal of potentially toxic species (18). In parallel, the ALP is

responsible for the clearance of larger substrates, including

protein aggregates, damaged organelles and long-lived proteins.

During this process, isolation membranes form autophagosomes that

engulf the target substrates, which subsequently fuse with

lysosomes. Hydrolytic enzymes within the lysosome degrade the

contents into amino acids and lipids for cellular reuse (19). Together, UPS and ALP establish an

integrated quality control cycle that prevents harmful aggregate

accumulation while maintaining metabolic balance (Fig. 1C).

Under conditions of high translational load or

environmental stress, large amounts of misfolded or unfolded

proteins accumulate in the ER lumen, disturbing folding balance and

triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) (20). The initiation of UPR depends on

the molecular chaperone glucose-regulated protein 78/binding

immunoglobulin protein (BiP), which serves as a central sensor.

Under normal conditions, BiP binds to the three principal ER stress

receptors, inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), PKR-like ER kinase

(PERK) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), keeping them

inactive. When unfolded proteins accumulate, BiP preferentially

associates with these substrates and dissociates from the

receptors, thereby activating downstream signaling pathways.

Activated IRE1α mediates the unconventional splicing of spliced

X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA, producing the transcription

factor XBP1s, which upregulates chaperones, foldases and

ER-associated degradation (ERAD) genes to enhance folding and

clearance capacity. PERK phosphorylates eIF2α to reduce global

translation, while selectively promoting ATF4 translation, which

activates antioxidant, autophagy and metabolic pathways. ATF6 is

transported to the Golgi apparatus, where proteolytic cleavage

releases its cytosolic fragment, which translocates to the nucleus

to induce transcription of chaperones and ERAD-related genes

(20). Together, these

mechanisms restore ER folding and degradation balance under

moderate stress, allowing cells to adapt. However, when stress is

excessive or persistent, UPR signaling shifts toward apoptosis,

e.g. through PERK-ATF4-C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) induction,

thereby converting proteostatic imbalance into pathological injury

(20). Thus, the UPR functions

as a critical protective mechanism of proteostasis, but also as a

decisive switch between adaptation and cell death, with BiP acting

as the essential gatekeeper of this process.

Altogether, these processes form a highly integrated

proteostasis network that safeguards protein quality and cellular

function. Breakdown of this network leads to the accumulation of

toxic species, driving pathology in neurodegenerative, oncogenic,

cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Against this backdrop,

FKBPs have emerged as critical regulators that interface with

multiple proteostatic pathways, highlighting their importance in

both physiological adaptation and disease progression.

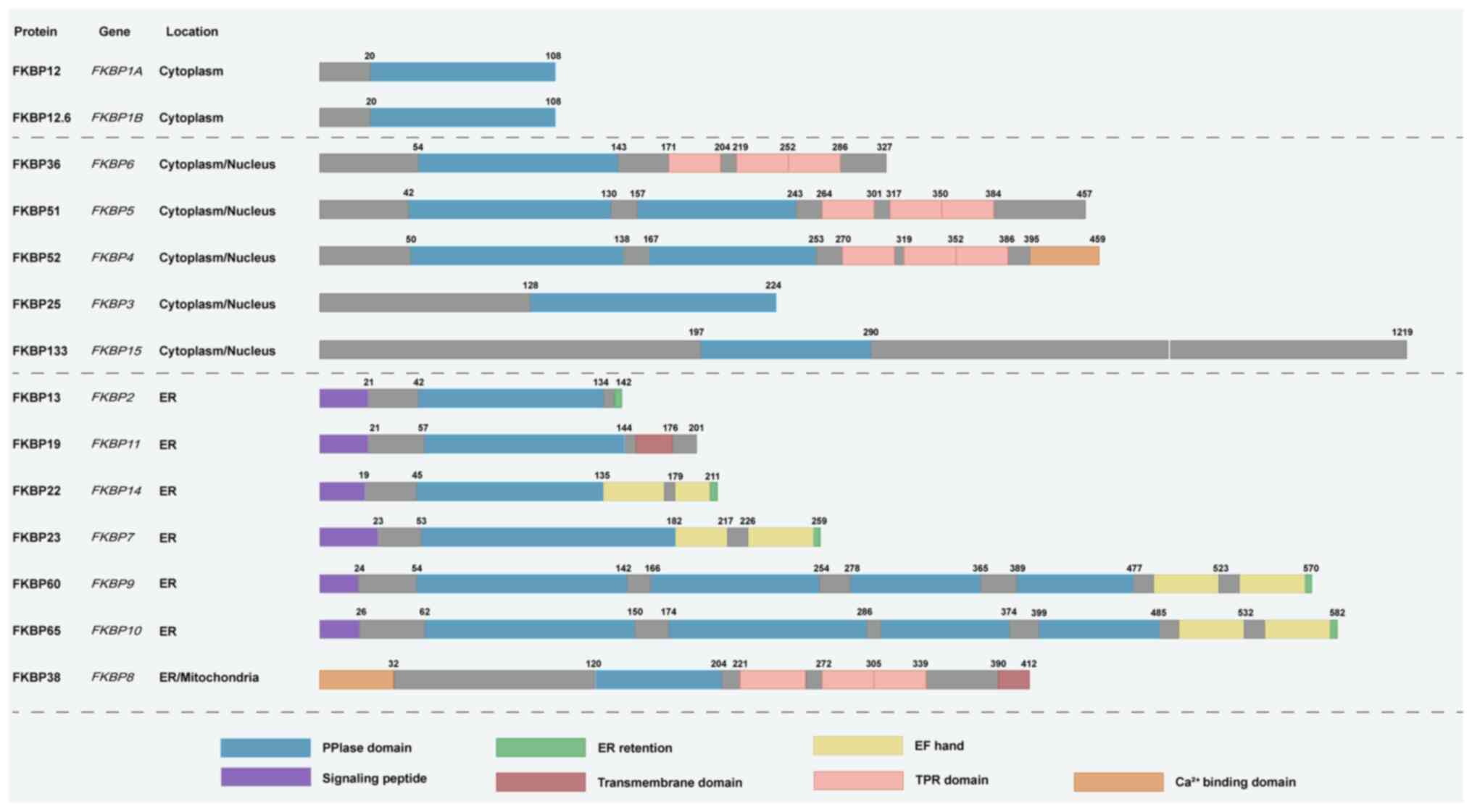

Structural basis of FKBP functions in

protein homeostasis

The FKBP family shares a conserved core domain, the

PPIase domain (21). This domain

catalyzes the cis-trans isomerization of proline residues in

polypeptide chains, accelerating folding kinetics and ensuring that

nascent proteins rapidly reach their correct conformation (22). This activity is critical for

maintaining protein homeostasis, as proline isomerization often

represents a rate-limiting step in folding. Under stress or high

translational load, PPIase activity facilitates timely restoration

of folding equilibrium (23).

The smallest members, such as FKBP12 and FKBP12.6, consist almost

entirely of the PPIase domain and interact directly with substrates

or complexes, modulating their stability and function through

conformational control (24).

Larger members often contain multiple PPIase domains, for instance,

FKBP52 has two and FKBP65 has four, potentially broadening

substrate specificity or enabling cooperative folding of

multidomain proteins (25).

Beyond the PPIase core, numerous FKBPs possess

additional functional modules that expand their regulatory

capacity. The most prominent is the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)

domain, a 34-amino acid tandem repeat that mediates protein-protein

interactions and is found in proteins such as FKBP51 and FKBP52

(26). The TPR domain enables

specific binding to the molecular chaperone heat shock protein

(Hsp)90, integrating FKBPs into chaperone complexes. Hsp90 is a

highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed eukaryotic chaperone

that, unlike many other chaperones, primarily acts on partially or

fully folded proteins (27).

Through ATP-dependent conformational changes, Hsp90 maintains the

functional state of client proteins and stabilizes diverse

signaling proteins, receptors and transcription factors (28). This association allows FKBPs not

only to catalyze substrate folding independently but also to

contribute to protein maturation, conformational maintenance and

complex stability within the chaperone network (29). FKBP51 and FKBP52 act as molecular

scaffolds within this system. FKBP52 promotes hormone receptor

maturation and facilitates their active transport to the nucleus,

whereas FKBP51 modulates complex conformation or recruit

phosphatases to fine-tune signaling output (30,31). These activities directly

influence protein complex stability, subcellular localization and

signal transduction, thereby exerting precise control over protein

homeostasis.

Certain FKBPs contain other specialized domains that

confer distinct subcellular localization and regulatory

specificity. FKBP13, FKBP19, FKBP22, FKBP23, FKBP60 and FKBP65

possess N-terminal ER signal peptides and localize to the ER lumen,

where they regulate the folding and assembly of secretory and

membrane proteins (32-35). FKBP25 contains a DNA-binding

domain, enabling it to participate in transcriptional regulation

and chromatin remodeling (36).

FKBP38 features a transmembrane anchor that targets it to

mitochondria, where it recruits anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family

proteins to regulate apoptosis and mitophagy (7,37). These additional domains extend

the influence of FKBPs to multiple organelles and signaling

networks, allowing them to maintain protein homeostasis across

diverse cellular contexts (Fig.

2).

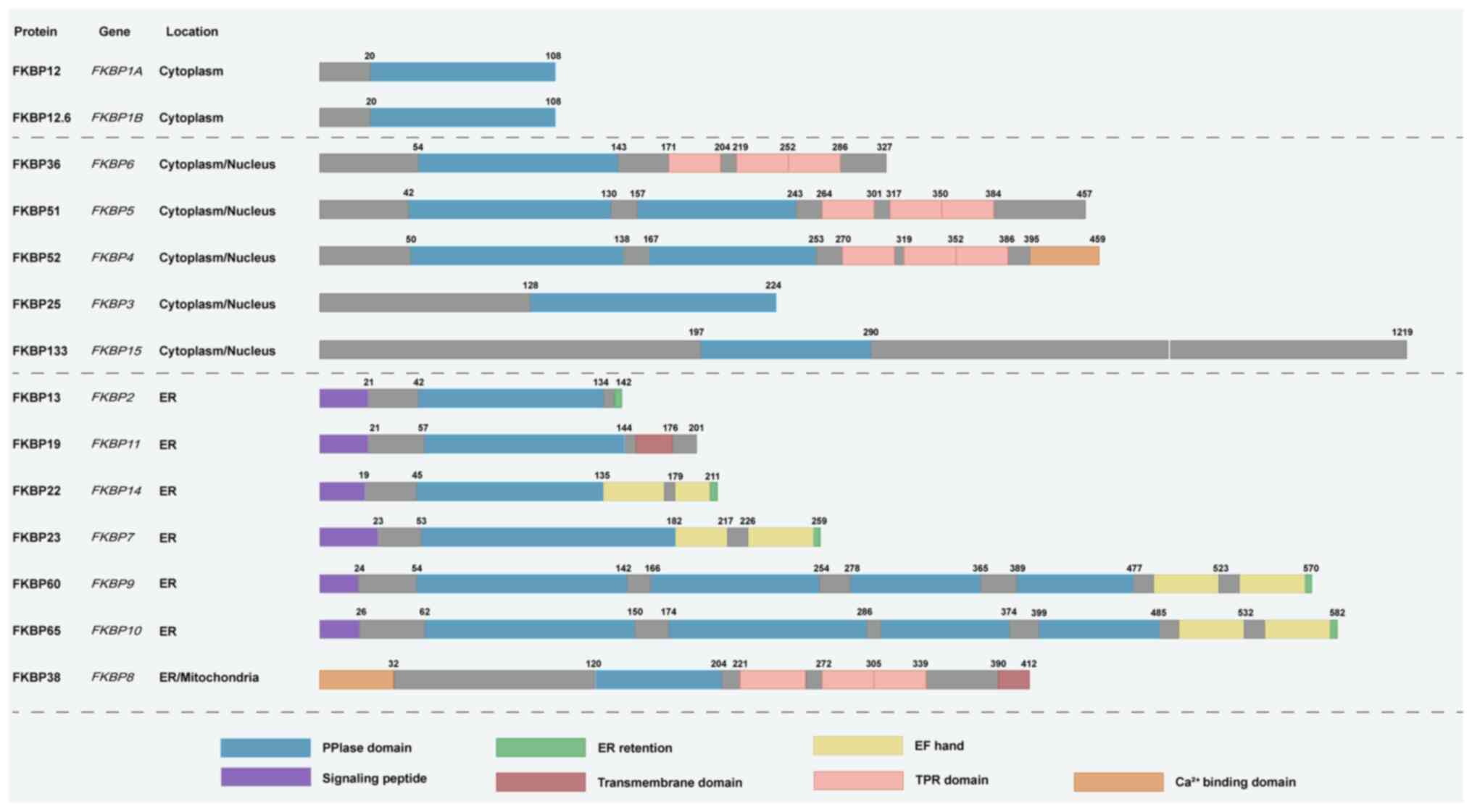

| Figure 2Structural diversity and subcellular

localization of FKBP family members. Schematic representation of

FKBPs, organized by their predominant localization in the

cytoplasm/nucleus or ER/mitochondria. The figure illustrates the

modular architecture of FKBPs and highlights how distinct domains

support their functional diversity in protein homeostasis. All

family members share the conserved PPIase domain, which catalyzes

proline isomerization to accelerate protein folding and

conformational stabilization. Several larger members, such as

FKBP51 and FKBP52, also contain TPR domains that mediate docking to

heat shock protein 90, enabling scaffold functions in protein

folding, complex stabilization and nuclear receptor trafficking.

Members including FKBP13, FKBP19, FKBP22, FKBP23, FKBP60 and FKBP65

harbor N-terminal ER signal peptides and ER retention motifs, which

target them to the ER lumen for the folding and assembly of

secretory and membrane proteins. FKBP38 contains a C-terminal

transmembrane anchor that localizes it to mitochondria and

facilitates anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 recruitment, linking FKBPs to

apoptosis and mitophagy regulation. Additional modules such as

EF-hand motifs and Ca2+-binding domains provide

responsiveness to calcium signaling, further expanding functional

versatility. Together, this structural heterogeneity enables FKBPs

to regulate protein folding, modification, trafficking and

degradation across diverse subcellular compartments. PPIase,

peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase; TPR, tetratricopeptide repeat;

ER, endoplasmic reticulum; EF-hand, helix-loop-helix

calcium-binding motif; FKBPs, FK506-binding proteins. |

In summary, the structural diversity of FKBPs

underpins their multilayered roles in protein homeostasis. The

PPIase domain directly modulates folding kinetics and

conformational stability. The TPR domain connects FKBPs to the

molecular chaperone network, mediating complex assembly and

maintenance. Specialized domains confer subcellular specificity and

functional diversification. Through coordinated action of these

modular elements, FKBPs regulate folding, complex stability,

localization and degradation, providing a structural and functional

basis for maintaining protein homeostasis in physiological and

stress conditions, as well as in disease states. In this review,

FKBP nomenclature refers to the protein products unless otherwise

specified. For clarity, gene symbols such as FKBP7,

FKBP9 and FKBP10 are used to denote their

corresponding protein products (FKBP7, FKBP9, FKBP10). This

convention is adopted to maintain consistency with other family

members (e.g., FKBP12, FKBP51, FKBP52), which are widely recognized

by their protein names.

FKBPs coordinate proteostasis networks to

drive tumor progression

Protein homeostasis is essential for tumor cells to

survive the proteotoxic stress generated by rapid proliferation and

harsh microenvironments. To cope with the increased burden of

protein synthesis and quality control, cancer cells rely on finely

tuned proteostasis networks that regulate folding, stability,

signaling and degradation (38).

Members of the FKBP family have emerged as central regulators in

this process, leveraging their structural modules to influence

distinct layers of proteostasis. Certain FKBPs within the ER

safeguard protein folding and translational balance, others

integrate post-translational modifications and selective

degradation to adapt the tumor microenvironment, while still others

stabilize nuclear receptors to amplify hormone-driven

proliferation. Together, these multifaceted functions highlight

FKBPs as key molecular nodes linking proteostasis to cancer

progression.

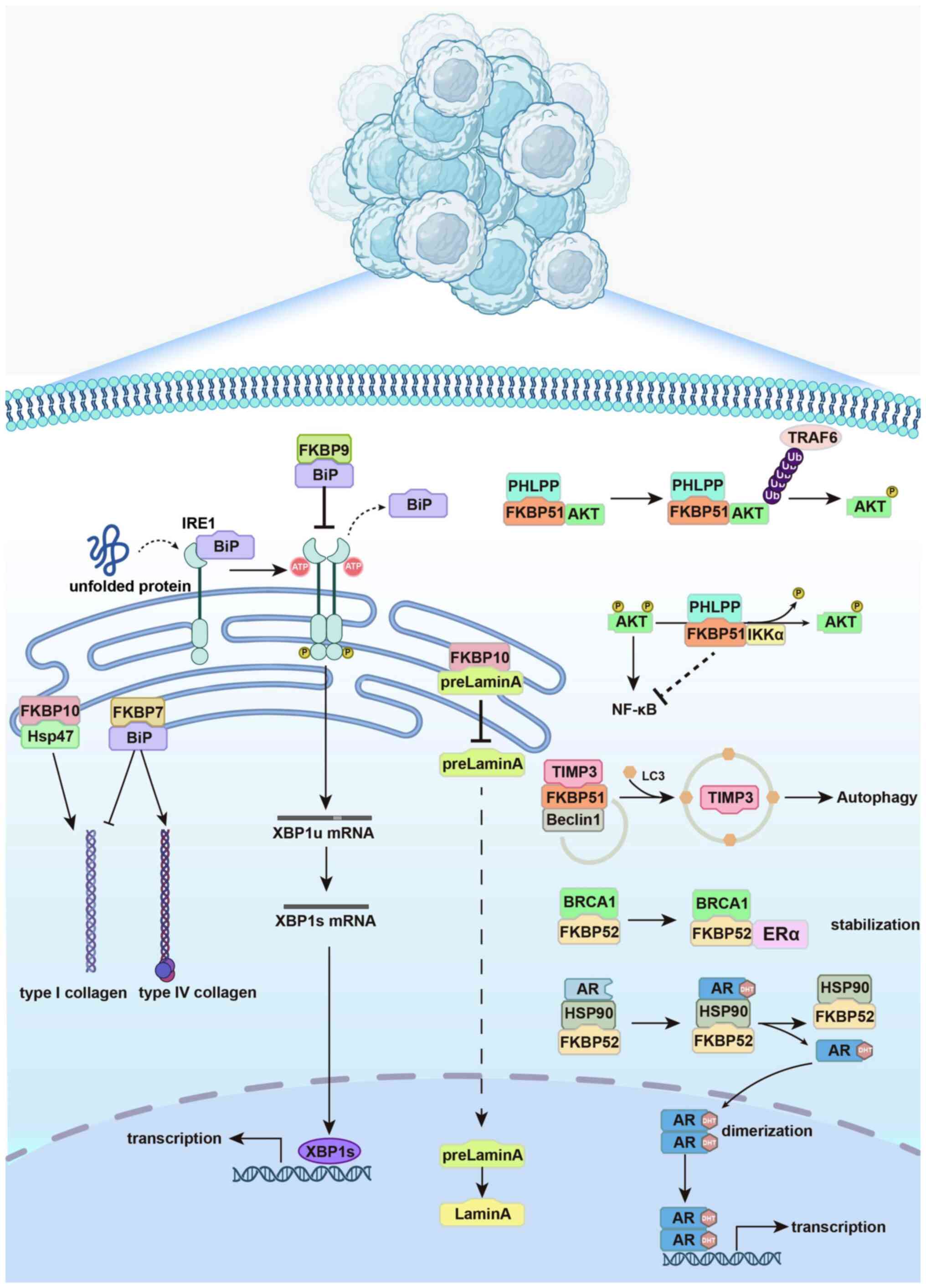

ER-resident FKBPs maintain ER

proteostasis to promote tumor invasion and metastasis

The ER is the principal site for protein synthesis,

folding and quality control, and its homeostasis is indispensable

for sustaining the rapid growth and survival of cancer cells.

Disruption of ER proteostasis caused by high translational demand

and oncogenic stress activates adaptive mechanisms such as the UPR,

which enables tumor cells to tolerate proteotoxic stress and resist

apoptosis. Several FKBPs localize to the ER lumen. Among them,

FKBP7, FKBP9 and FKBP10 (hereafter referring to the protein) have

been most extensively studied in the context of tumor biology.

FKBP9 and FKBP7 help tumor cells adapt to increased

protein synthesis and folding pressure by regulating the ER

proteostasis network. FKBP9 forms a complex with the molecular

chaperone BiP to support correct protein folding and assembly,

maintaining folding equilibrium within the ER. In glioblastoma,

FKBP9 inhibits the IRE1α-XBP1 signaling pathway and suppresses

CHOP-mediated apoptosis, preventing overactivation of the UPR and

enhancing resistance to ER stress (39). FKBP9 expression correlates

positively with BiP levels, and their co-expression is associated

with poor prognosis, underscoring its key role in ER homeostasis

(40).

FKBP7 contributes to proteostasis and extends its

influence to the tumor microenvironment. In pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma, FKBP7 is highly expressed in cancer-associated

fibroblasts (CAFs). By competing with BiP, FKBP7 alters the

secretion of collagen subtypes, reducing type I and increasing type

IV collagen. This promotes a dense extracellular matrix that

restricts immune infiltration and supports tumor invasion (41). These functions demonstrate that

FKBP7 modulates both ER stress adaptation and extracellular matrix

remodeling (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3ER-resident and cytoplasmic FKBPs

regulate proteostasis to support tumor progression. Schematic

illustration of how representative FKBPs contribute to protein

homeostasis in cancer. In the ER, FKBP9 binds to BiP to maintain

folding equilibrium and suppress excessive IRE1α-XBP1 activation,

protecting cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis. FKBP7 interacts

with BiP in cancer-associated fibroblasts to modulate collagen

subtype secretion, favoring extracellular matrix remodeling and

tumor invasion. FKBP10 regulates substrate maturation and

localization, including retention of prelamin A in the ER and

stabilization of type I procollagen through cooperation with Hsp47,

and also supports translational efficiency at the ribosome. Outside

the ER, FKBP51 functions as a scaffold that shapes

post-translational modifications and autophagic turnover: It

recruits PHLPP to regulate AKT dephosphorylation, promotes Akt

ubiquitination via TRAF6 and directs TIMP3 degradation through the

Beclin1 complex, thereby modulating survival signaling and

microenvironment remodeling. FKBP52 acts as an Hsp90 co-chaperone

that stabilizes steroid hormone receptors such as AR and ERα,

facilitates their nuclear transport via dynein and enhances

transcriptional activation of oncogenic programs. Collectively,

these mechanisms highlight how distinct FKBPs integrate ER stress

responses, protein folding, post-translational regulation and

receptor signaling to maintain proteostasis and promote malignant

progression. FKBP, FK506-binding protein; ER, endoplasmic

reticulum; BiP, binding immunoglobulin protein (GRP78); IRE1α,

inositol-requiring enzyme 1α; XBP1s, X-box binding protein 1

spliced isoform; UPR, unfolded protein response; CAF,

cancer-associated fibroblast; PPIase, peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans

isomerase; AKT, protein kinase B; PHLPP, PH domain and leucine-rich

repeat protein phosphatase; TRAF6, TNF receptor-associated factor

6; TIMP3, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3; AR, androgen

receptor; ERα, estrogen receptor α; Hsp, heat shock protein; IKKα,

IκB kinase α; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; Ub, ubiquitin; BRCA1,

breast cancer 1, early onset. |

Unlike FKBP9 and FKBP7, FKBP10 plays a distinct role

in protein homeostasis that is less dependent on classical ER

stress signaling. FKBP10 primarily contributes to proteostasis by

regulating substrate folding and subcellular localization. Through

its PPIase domain, FKBP10 binds directly to specific client

proteins to influence their conformational maturation and

intracellular trafficking. In bladder cancer, FKBP10 binds prelamin

A, leading to its retention in the ER and preventing its

translocation into the nucleus, thereby disrupting Lamin A

formation and nuclear structure (42). This results in nuclear atypia and

enhances the migratory and invasive capacity of cancer cells. In

glioma, FKBP10 interacts with Hsp47 via its third PPIase domain to

promote the folding and stabilization of type I procollagen, which

directly facilitates extracellular matrix organization and the

establishment of a tumor-supportive microenvironment (10).

Beyond its role in folding and localization, FKBP10

also supports translational homeostasis in highly proliferative

cancer cells. Its conserved PPIase domain catalyzes the

isomerization of proline residues in nascent polypeptides,

accelerating translation elongation, particularly for proline-rich

ribosomal and structural proteins. Loss of FKBP10 impairs this

isomerization process, leading to ribosomal stalling at proline

motifs and reduced synthesis of proline-rich proteins, underscoring

the dependence of such proteins on FKBP10-mediated PPIase activity.

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), FKBP10 localizes to the

ribosomal catalytic center, reinforcing its function in supporting

translation (43). Loss of

FKBP10 or impairment of its enzymatic activity reduces translation

efficiency, impairs cell cycle progression and induces apoptosis.

FKBP10 is upregulated in multiple malignancies, including NSCLC,

colorectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma, bladder cancer and glioma,

and is associated with poor prognosis (44-46). Its knockdown not only inhibits

proliferation and migration but also sensitizes tumor cells to

chemotherapy and targeted therapies, highlighting its potential as

a therapeutic target (Fig.

3).

In conclusion, FKBP7, FKBP9 and FKBP10 are

ER-resident FKBPs that regulate proteostasis through distinct

mechanisms. FKBP9 and FKBP7 primarily participate in unfolded

protein responses and protein folding control, while FKBP10 governs

translational efficiency and substrate localization. These proteins

enable cancer cells to manage translational stress and maintain

proteome integrity under oncogenic pressure, linking ER

proteostasis to malignant progression. Targeting the functional

domains of these FKBPs may offer promising therapeutic strategies

for cancers characterized by dysregulated protein homeostasis and

elevated ER stress.

FKBP51 integrates post-translational

modifications (PTMs) and selective degradation to promote

microenvironment remodeling

PTMs are key regulatory mechanisms that control

protein function, stability and subcellular localization. They play

a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and in

coordinating responses to external stimuli. In the tumor

microenvironment, PTMs are extensively involved in signal

transduction, cell cycle regulation, metabolic reprogramming and

immune evasion (47).

Dysregulation of PTMs is closely linked to tumor initiation,

progression and treatment resistance.

FKBP51 (also known as FKBP5) has emerged as a

critical regulator that integrates PTM-dependent signaling with

protein stability and cellular adaptation. FKBP51 contributes to

tumor progression by modulating phosphorylation, ubiquitination and

acetylation of key signaling proteins, thereby shaping the

functional output of oncogenic pathways.

One of the core functions of FKBP51 is to modulate

PTMs of key signaling proteins, maintaining the integrity of

signaling complexes and regulating downstream signaling outputs. A

well-characterized example is its bidirectional regulation of the

Akt pathway. In melanoma, FKBP51 interacts with Hsp90 to enhance

K63-linked ubiquitination of Akt, which increases Akt stability and

activity, thereby activating downstream effectors such as P70S6K

and Cyclin D1 to promote cell proliferation (48). By contrast, in prostate and

pancreatic cancers, FKBP51 enhances its interaction with PH domain

and leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP), facilitating

dephosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and attenuating Akt activity,

thereby suppressing survival signaling (49). The direction of FKBP51-mediated

Akt regulation depends on factors such as PHLPP expression, Hsp90

status and FKBP51's own PTM state, reflecting its functional

plasticity as a scaffold protein within signaling complexes

(Fig. 3).

Furthermore, in castration-resistant prostate

cancer, FKBP51 forms a complex with PHLPP and inhibitor of NF-κB

kinase subunit α to inhibit both Akt and NF-κB pathways (50). In melanoma, FKBP51 enhances

acetylation of the transcription factor YY1, which suppresses the

expression of the pro-apoptotic death receptor 5 and reduces

sensitivity to apoptosis triggered by TNF-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand (51).

These findings collectively indicate that FKBP51 modulates key

signaling pathways by coordinating phosphorylation, ubiquitination

and acetylation, thereby enabling tumor cells to adapt and survive

in hostile microenvironments.

In addition, FKBP51 regulates protein stability and

degradation by mediating selective autophagic turnover of specific

substrates. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma, FKBP51 binds to the

metalloproteinase inhibitor tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

3 (TIMP3) and recruits it to the Beclin1 autophagy complex,

promoting its lysosome-dependent degradation. Since TIMP3 inhibits

extracellular matrix degradation, its downregulation facilitates

tumor cell invasion (52). This

suggests that FKBP51 contributes to tumor microenvironment

remodeling by modulating the stability and degradation of specific

proteins (Fig. 3).

In summary, FKBP51 maintains protein homeostasis by

coordinating PTMs and selective degradation. Through its roles in

signal regulation, apoptosis resistance and microenvironment

adaptation, FKBP51 supports sustained proliferation, migration and

therapy resistance in tumor cells, highlighting its potential as a

key regulator of proteostasis and a promising therapeutic

target.

FKBP52 stabilizes and translocates

nuclear receptors to enhance hormone-driven tumor growth

FKBP52 (also known as FKBP4) is a key co-chaperone

within the Hsp90 complex. In various cancers, its oncogenic role is

closely linked to the regulation of nuclear receptor stability,

activity and subcellular localization. A central mechanism involves

its ability to assemble and stabilize hormone receptor-chaperone

complexes, enhance receptor conformational integrity and facilitate

their nuclear translocation. Through its TPR domain, FKBP52 binds

to Hsp90 and forms a stable chaperone complex (53). Its PPIase domain further

modulates the conformation of steroid receptors-such as androgen

receptor (AR), estrogen receptor α (ERα) and glucocorticoid

receptor (GR)-via prolyl isomerization, thereby enhancing ligand

binding and transcriptional activity (54,55). In breast and prostate cancers,

FKBP52 increases the abundance and activity of ERα and AR, and its

elevated expression is strongly associated with tumor progression

and poor prognosis (56,57).

Notably, FKBP52 plays a critical role in regulating

the subcellular trafficking of nuclear receptors. Upon ligand

binding, FKBP52 facilitates the recruitment of the dynein motor

complex to the receptor-Hsp90 complex. This interaction promotes

active transport of the receptor complex along microtubules toward

the nucleus, enabling efficient nuclear import through the nuclear

pore complex. This nuclear translocation is essential for

receptor-mediated transcriptional activation. For instance, FKBP52

enhances GR nuclear accumulation and transcriptional output by

supporting its interaction with the dynein complex (58). Similarly, FKBP52 promotes the

nuclear import of RelA (p65) in the NF-κB pathway by stabilizing

its association with Hsp70, thereby amplifying NF-κB

transcriptional activity and contributing to tumor proliferation

and inflammatory signaling (59)

(Fig. 3).

In summary, FKBP52 acts as a molecular scaffold that

regulates both the stability and nuclear localization of key

transcriptional regulators. By coordinating the chaperoning,

transport and activation of nuclear receptors and signaling

proteins, FKBP52 helps maintain protein homeostasis and promotes

cancer cell growth and adaptation. These findings highlight FKBP52

as a critical node in oncogenic signaling and a promising

therapeutic target.

FKBPs orchestrate the dual regulation of

pathogenic proteins in neurodegenerative diseases

Protein homeostasis is a central determinant of

neuronal survival, as the brain is particularly vulnerable to the

toxic effects of misfolded or aggregated proteins. In

neurodegenerative diseases, the collapse of proteostatic control

leads to the pathological accumulation of proteins such as

α-synuclein (α-Syn) and tau, which form aggregates that disrupt

synaptic integrity, impair intracellular trafficking and ultimately

drive neuronal death (60,61). Maintaining the balance between

protein folding, degradation and aggregation is therefore critical

for preventing neurotoxicity. FKBPs have emerged as important

regulators of pathogenic protein dynamics. By modulating

conformational states, post-translational processing and

degradation pathways, FKBPs directly shape the fate of

disease-related proteins, positioning them as key players in the

onset and progression of Parkinson's disease (PD) and Alzheimer's

disease (AD).

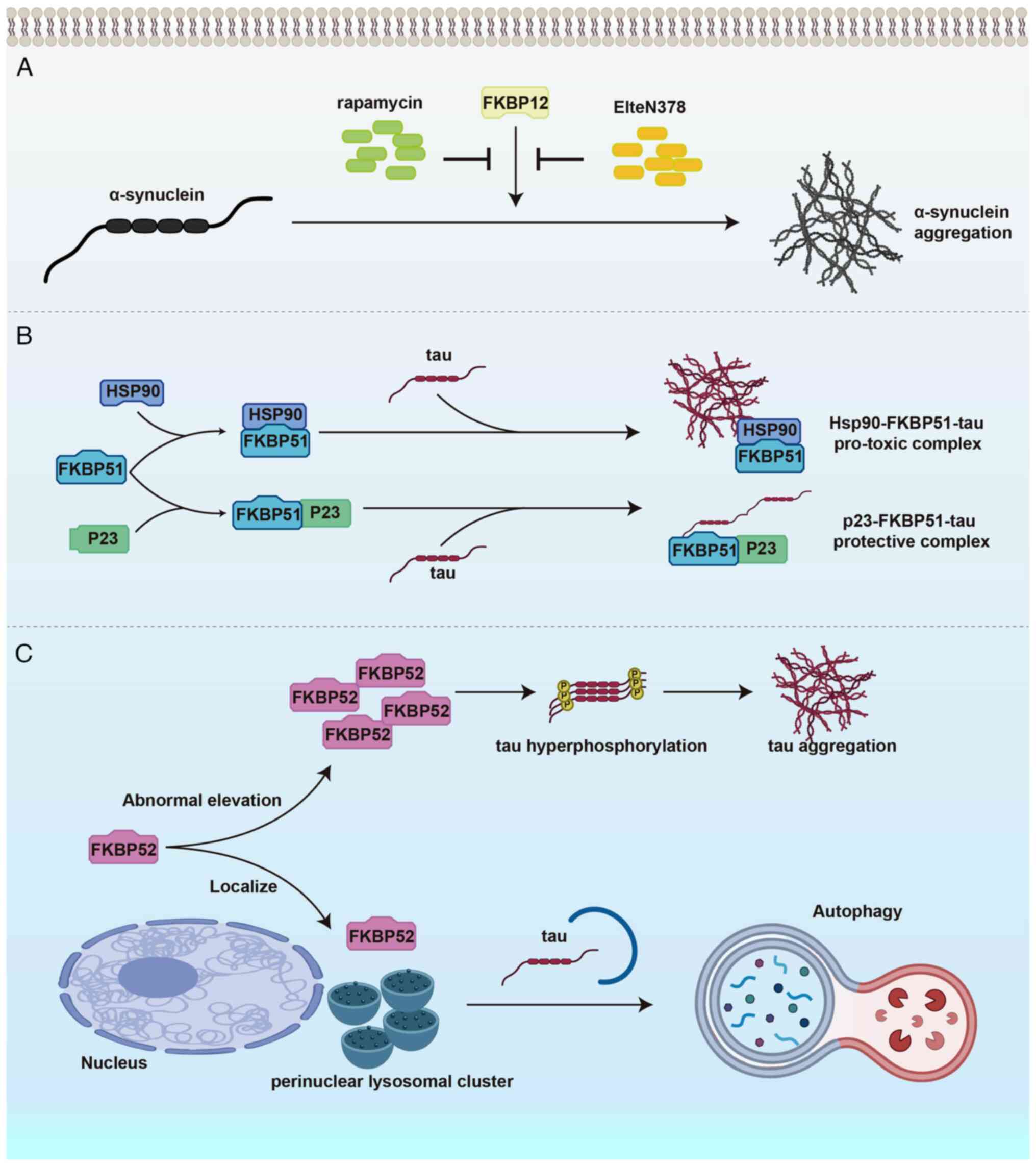

FKBP12 drives α-Syn misfolding and

aggregation to exacerbate PD pathogenesis

PD is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder

primarily characterized by the selective degeneration of

dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to impaired

motor function (62,63). Although the precise mechanisms

underlying the disease remain incompletely elucidated, accumulating

evidence indicates that the aberrant aggregation of α-Syn

constitutes a critical pathological hallmark of PD (64). α-Syn is a widely expressed

cytoplasmic protein that normally participates in the regulation of

synaptic function. However, in PD, α-Syn undergoes pathological

aggregation into fibrillar structures within neurons, forming Lewy

bodies, which in turn induce neurotoxicity and contribute to

neurodegeneration (65).

Investigations have revealed that the PPIase

activity of FKBPs and their role in modulating protein folding are

intricately linked to the aggregation of α-Syn (66). FKBP12 contributes to the

pathogenesis of PD through multiple mechanisms that disrupt

proteostasis. It directly interferes with the folding and

aggregation of α-Syn by binding to its proline-rich C-terminal

region and catalyzing cis/trans isomerization of terminal prolines,

inducing pathogenic conformational changes in the monomer. This

markedly accelerates and alters aggregation kinetics, promoting the

formation of highly branched dendritic structures (66). In addition, FKBP12 forms a

complex with calcineurin under conditions of sustained cytosolic

Ca2+ elevation induced by α-Syn toxicity. This complex

drives pathological dephosphorylation of key presynaptic proteins

involved in vesicle trafficking, endocytosis and cytoskeletal

organization, including growth associated protein 43 and brain acid

soluble protein 1. The resulting synaptic dysfunction destabilizes

dopamine transporters at the plasma membrane, reduces dopamine

release and leads to neuronal death (67). Given FKBP12's pivotal role in the

disease process, targeting this protein represents a promising

strategy for disease-modifying therapeutic interventions. A recent

study demonstrated that rapamycin, through the inhibition of FKBP12

independent of the mTORC1 pathway, confers neuroprotective effects,

underscoring FKBP12 as a novel therapeutic target for PD (68). Furthermore, non-immunosuppressive

FKBP12 inhibitors, such as ElteN378, have shown efficacy in

preventing α-Syn aggregation, presenting a potential new class of

therapeutics for early-stage PD treatment (69) (Fig. 4A). However, challenges remain in

achieving adequate brain penetration and isoform selectivity for

these compounds, which may limit their translational applicability

and require further optimization.

| Figure 4FKBPs regulate neuronal protein

homeostasis through distinct mechanisms in neurodegenerative

diseases. (A) FKBP12 accelerates α-synuclein misfolding and

aggregation via prolyl isomerization, promoting Parkinson's disease

pathology. Pharmacological inhibition of FKBP12 by rapamycin or the

non-immunosuppressive compound ElteN378 suppresses α-SYN

aggregation, conferring neuroprotective effects. (B) FKBP51

modulates tau proteostasis through the Hsp90 chaperone complex,

balancing tau aggregation and stabilization in Alzheimer's disease.

The Hsp90-FKBP51-tau complex promotes pathogenic tau

oligomerization, while the p23-FKBP51-tau complex stabilizes tau in

a non-aggregated state, exerting a protective effect. (C) Under

physiological conditions, FKBP52 facilitates tau degradation

through the autophagy-lysosome pathway. However, its abnormal

elevation enhances tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation,

contributing to neurofibrillary tangle formation and

neurodegeneration. α-SYN, α-synuclein; PD, Parkinson's disease; AD,

Alzheimer's disease; FKBP, FK506-binding protein; Hsp, heat shock

protein. |

In summary, FKBP12, through its PPIase activity,

disrupts neuronal proteostasis via multiple pathways, including the

regulation of α-Syn conformation, alteration of its aggregation

dynamics and calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation of synaptic

proteins. These processes collectively drive the onset and

progression of PD. The multifaceted role of FKBP12 in disease

pathogenesis not only reveals a new dimension of proteostasis

imbalance in PD but also provides a solid theoretical foundation

and potential avenues for the development of disease-modifying

therapies targeting FKBP12.

FKBP51 and FKBP52 modulate tau

aggregation-degradation balance to shape AD pathology

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder

characterized by cognitive decline, with hallmark pathological

features including β-amyloid plaque deposition and neurofibrillary

tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (70-72). Tau, a microtubule-associated

protein, undergoes conformational alterations and aggregation that

are considered central to the neuronal dysfunction and cell death

observed in AD (71,73-75). In recent years, FKBP51 and FKBP52

have garnered increasing attention for their regulatory roles in

tau pathology.

FKBP51 promotes tau oligomer formation through

cooperation with Hsp90. Hsp90 functions as a scaffold, precisely

positioning the proline-rich region of tau into the PPIase

catalytic pocket of FKBP51, thereby catalyzing proline cis/trans

isomerization. This process alters tau conformation and

phosphorylation status, accelerating oligomer accumulation. The

resulting changes enhance tau pathogenicity, disrupt neuronal

proteostasis and drive the progression of neurodegeneration

(76). By contrast, FKBP51 can

also form a complex with the Hsp90 co-chaperone p23, whose

negatively charged C-terminal tail binds to the positively charged,

aggregation-prone repeat domain of tau, inhibiting its

fibrillization kinetics. When p23 and FKBP51 are both present, a

p23-FKBP51-tau ternary complex may form, partially counteracting

the aggregation-promoting effect of FKBP51 and exerting a

protective regulatory influence on tau aggregation (77). These findings indicate that

FKBP51 can either exacerbate or suppress tau aggregation depending

on its interaction partners, with the functional outcome determined

by the composition and dynamic balance of the chaperone network

(Fig. 4B).

In parallel, FKBP52 plays a pivotal role in

regulating tau protein homeostasis, influencing both its

degradation and the formation of pathological aggregates (78). Under tau proteotoxic stress,

FKBP52 localizes to perinuclear lysosomal clusters and supports the

function of the ALP, promoting lysosomal degradation of tau and

preventing its abnormal secretion, thereby limiting extracellular

tau propagation (12). By

contrast, abnormally elevated FKBP52 levels markedly enhance tau

hyperphosphorylation and aggregation, with a more pronounced

pathological effect in the aged brain. This pro-aggregation

activity is not only associated with its regulation of tau

conformation and aggregation kinetics through the Hsp90 chaperone

network, but may also involve activation of glial cells and the

release of inflammatory mediators, creating a feedforward loop

between tau aggregation and neuroinflammation that accelerates

neuronal injury (79). These

findings indicate that FKBP52 exerts dual, context-dependent

effects on tau pathology, with its regulatory direction shifting

under different physiological and pathological conditions,

providing important insights into the progression of tauopathies

and potential therapeutic strategies (Fig. 4C).

Collectively, FKBP51 and FKBP52 play multifaceted

and context-dependent roles in tau proteostasis. They act through

distinct yet overlapping mechanisms, including PPIase activity,

Hsp90 co-chaperone interactions and regulation of the

autophagy-lysosome pathway. Depending on the cellular context, they

can either promote or restrain tau aggregation. This dual

regulation shifts the balance between neuronal resilience and

degeneration, highlighting their importance as modulators of AD

progression and as potential therapeutic targets. An important

unresolved question is what specific cellular or pathological cues

dictate whether FKBP51 and FKBP52 act to promote or suppress tau

aggregation, a topic that warrants further investigation.

FKBPs stabilize ion channel conformation to

protect against cardiac dysfunction

Protein homeostasis is central to cardiovascular

physiology, where the stability of ion channel complexes and

contractile proteins is indispensable for maintaining cardiac

excitability and pump function. Disruption of proteostasis under

pathological stress contributes to electrical instability, impaired

contractility and progressive remodeling, forming the basis of

numerous cardiovascular diseases (80,81). Within this framework, FKBPs have

emerged as critical modulators of protein conformation and complex

stability. Among them, FKBP12.6 plays a particularly important role

in governing ion channel regulation, positioning it as a key

determinant of cardiac function and a potential therapeutic target

in heart failure and arrhythmias.

FKBP12.6 stabilizes ryanodine receptor 2

(RyR2) conformation to prevent diastolic calcium leak in heart

failure (HF) and arrhythmia

In cardiomyocytes, RyR2 is the primary calcium

release channel on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), and its protein

homeostasis is essential for regulating cardiac contractility and

rhythm (82,83). During excitation-contraction

coupling, RyR2 channels open in response to membrane

depolarization, releasing stored Ca2+ from the SR into

the cytosol to initiate contraction. In diastole, RyR2 channels are

expected to remain closed to prevent abnormal Ca2+

efflux and allow for Ca2+ reuptake and myocardial

relaxation (84,85). However, in HF and arrhythmias

such as atrial fibrillation (AF), dysregulation of the RyR2

macromolecular complex leads to pathological diastolic

Ca2+ leak, disrupting cytosolic Ca2+

homeostasis (86,87). This Ca2+ dysregulation

promotes delayed afterdepolarizations and triggered activity,

forming a shared pathological basis for HF and AF (88).

Within the RyR2 complex, FKBP12.6, also known as

calstabin2, acts as a key stabilizer of channel structure and

function. Cryo-electron microscopy studies reveal that RyR2

assembles as a homotetramer, with one FKBP12.6 molecule binding to

each protomer at specific interfacial regions. These sites are

located between the helical domain and SPRY domains, where FKBP12.6

stabilizes the closed conformation of the channel (89). Its binding extends the mean

closed time of RyR2, suppresses spontaneous openings and promotes

coupled gating between adjacent channels, thereby preventing

Ca2+ leakage in the resting state (90).

Under pathological conditions, particularly during

sustained sympathetic activation or oxidative stress, RyR2

homeostasis becomes disrupted. Post-translational modifications

such as protein kinase A-mediated hyperphosphorylation at Ser2808,

cysteine oxidation and S-nitrosylation result in the dissociation

of FKBP12.6 from the channel complex (15). This destabilizes the closed

conformation of RyR2, increases the open probability and promotes

diastolic Ca2+ leak, which in turn contributes to

Ca2+ overload, electrophysiological instability and

progressive cardiac dysfunction (91,92).

Multiple animal models support the central role of

FKBP12.6 in RyR2 regulation. In murine models of HF, RyR2 channels

exhibit increased Ser2808 phosphorylation and oxidative

modifications, accompanied by reduced FKBP12.6 binding. These

alterations correlate with enhanced Ca2+ leak and

reduced contractility (93).

Mice lacking FKBP12.6 develop spontaneous arrhythmias, whereas

FKBP12.6 overexpression or treatment with rycals such as S107

restores FKBP12.6 binding to RyR2, stabilizes channel closure,

reduces aberrant Ca2+ release and improves cardiac

function. Importantly, rycals do not directly block RyR2 openings

but enhance FKBP12.6 affinity for the channel, thereby stabilizing

the RyR2 macromolecular complex at a structural level (94). Similar mechanisms are observed in

AF, where atrial myocytes from patients with AF and animal models

show increased RyR2 phosphorylation and oxidation, decreased

FKBP12.6 binding and elevated diastolic Ca2+ spark

frequency. FKBP12.6-deficient mice, despite having structurally

normal hearts, exhibit enhanced susceptibility to pacing-induced

AF. Treatment with S107 suppresses this phenotype only in the

presence of FKBP12.6, indicating its essential role in the

therapeutic effect (94)

(Fig. 5).

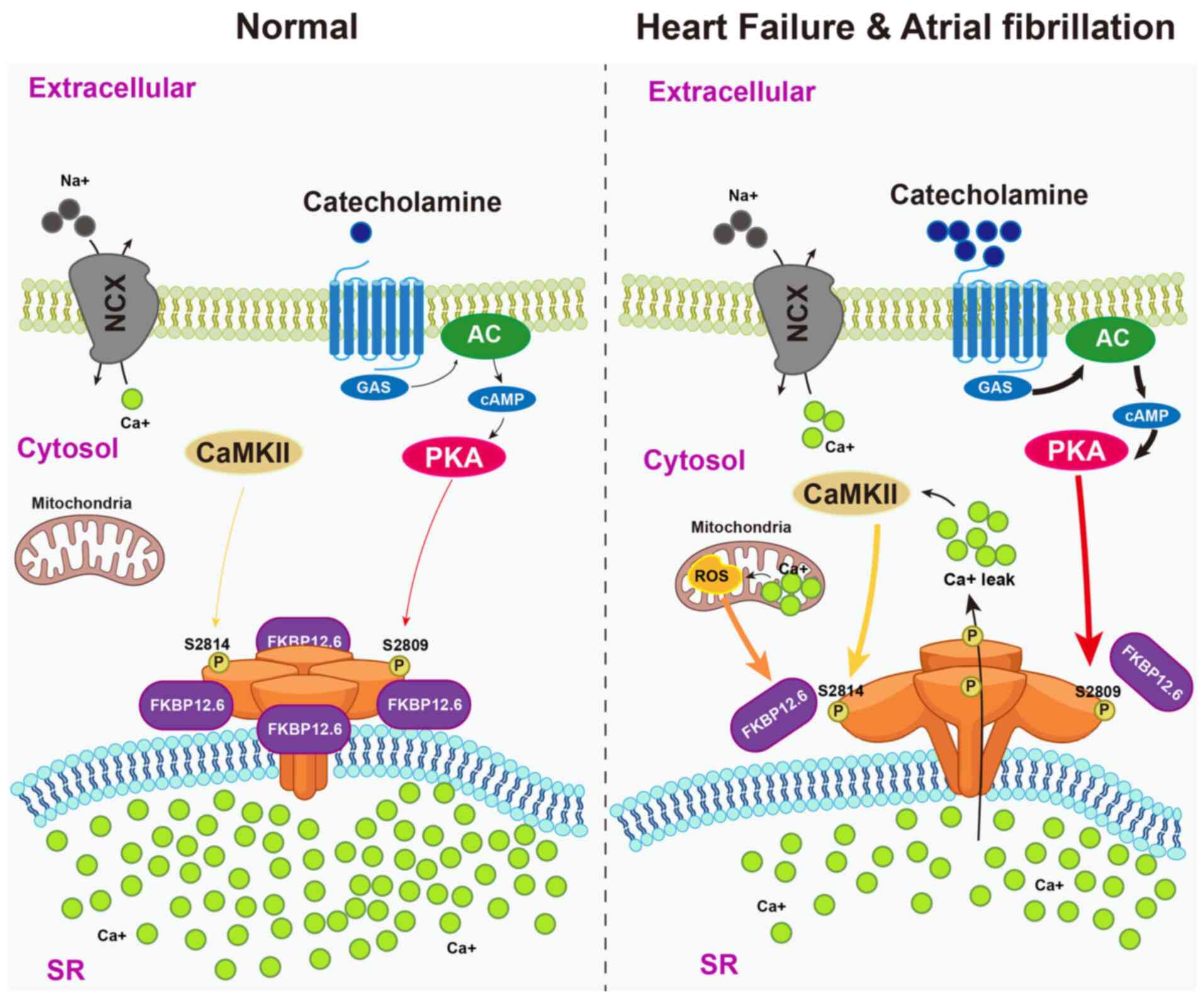

| Figure 5FKBP12.6 stabilizes RyR2 conformation

to prevent pathological Ca2+ leak in heart failure and

atrial fibrillation. Under physiological conditions (left),

catecholamine stimulation activates PKA and CaMKII, but RyR2

channels on the SR remain stabilized in the closed state by

FKBP12.6, preventing diastolic Ca2+ leak and preserving

Ca2+ cycling. In pathological settings such as heart

failure and atrial fibrillation (right), sustained sympathetic

drive and oxidative stress induce PKA hyperphosphorylation at

Ser2809, CaMKII phosphorylation at Ser2814 and oxidative

modifications of RyR2. These alterations disrupt FKBP12.6 binding,

destabilize the channel complex and promote aberrant

Ca2+ leak. The resulting cytosolic Ca2+

overload contributes to delayed afterdepolarizations,

arrhythmogenic activity and progressive cardiac dysfunction.

FKBP12.6, FK506-binding protein 12.6; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2;

SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; PKA, protein kinase A; CaMKII,

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; P, phosphorylation; GAS, GMP-AMP synthase; NCX,

sodium-calcium exchanger; AC, adenylyl cyclase. |

In summary, maintenance of RyR2 protein homeostasis

is critical for normal cardiac function. FKBP12.6 plays a pivotal

role in stabilizing the RyR2 complex and preventing pathological

Ca2+ leak. Therapeutic strategies targeting the

FKBP12.6-RyR2 interaction, particularly with rycal compounds, offer

a promising approach for precision treatment of HF and

arrhythmias.

FKBPs control metabolic kinase activity to

maintain metabolism balance

Metabolic homeostasis depends on the precise

regulation of key kinases that govern glucose utilization, lipid

turnover and energy sensing. The stability and activity of these

kinases are tightly controlled by proteostasis networks, which

ensure their correct folding, modification and timely degradation

(95,96). As pivotal regulators within this

system, FKBPs influence metabolic adaptation through multiple

proteostatic mechanisms. Among them, FKBP51 stands out for its role

as a molecular scaffold that shapes post-translational

modifications, particularly phosphorylation, thereby fine-tuning

the activity of central metabolic kinases and linking stress

responses to metabolic balance.

FKBP51 serves as a scaffold to modulate

kinase phosphorylation in metabolic regulation

In the central nervous system, FKBP51 influences

metabolic balance by modulating the activity of key kinases in the

autophagy pathway. Autophagy initiation requires activation of

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and is inhibited by mechanistic

target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) (97). AMPK activation depends on

phosphorylation of its upstream kinase liver kinase B1 (LKB1) at

Thr172, whereas mTORC1 activity is suppressed by the tuberous

sclerosis complex (TSC)1/2 complex (98). Members of the WD repeat domain

phosphoinositide-interacting (WIPI) protein family, WIPI4 and

WIPI3, act as scaffolds for LKB1-AMPK and TSC2, respectively,

coupling energy sensing to autophagy regulation (99,100). FKBP51 interacts with WIPI4 to

recruit LKB1 to the AMPK complex, enhancing Thr172 phosphorylation

and promoting UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) phosphorylation at Ser555

to initiate autophagy. In parallel, FKBP51 binds the WIPI3-TSC2

complex to cooperatively inhibit mTORC1 activity, further relieving

autophagy suppression (16).

The physiological relevance of these scaffold-based

mechanisms is supported by in vivo findings demonstrating

their dose-dependent effects on energy homeostasis and autophagy

regulation. In vivo, this regulation shows a clear dose

dependency. Mediobasal hypothalamus-specific deletion of FKBP51

reduces AMPK-ULK1 activation, enhances mTORC1 signaling, decreases

autophagy and leads to obesity, impaired glucose tolerance and

increased food intake. Moderate FKBP51 overexpression enhances AMPK

activity and autophagy in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue,

inhibits mTORC1 signaling, improves insulin sensitivity and limits

weight gain under high-fat diet conditions (101). By contrast, excessive FKBP51

expression activates AKT-mTORC1 signaling, suppresses autophagy and

disrupts proteostasis. This bidirectional effect of deficiency and

overexpression highlights FKBP51 as a dose-sensitive regulator of

autophagy and metabolic balance (102) (Fig. 6A). In glucose metabolism, FKBP51

modulates the AKT-forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) signaling axis in

pancreatic β cells to regulate cell function and survival. AKT is a

serine/threonine kinase activated by phosphorylation at Thr308 and

Ser473 downstream of insulin receptor-PI3K-pyruvate dehydrogenase

kinase 1/mTORC2 signaling (103). Activated AKT phosphorylates the

transcription factor FOXO1 at Ser256, promoting its nuclear export

and repressing the transcription of target genes (104,105). FOXO1 is essential for β-cell

differentiation, maturity and stress adaptation (106,107). As a scaffold protein, FKBP51

recruits the phosphatase PHLPP to AKT, facilitating

dephosphorylation at Ser473 and reducing AKT activity. This

decreases FOXO1 Ser256 phosphorylation, promotes its nuclear

retention and preserves transcriptional activity. Under

inflammatory stress, this mechanism helps maintain β-cell function,

enhance survival and sustain glucose-stimulated insulin secretion,

forming a protective FKBP51-PHLPP-AKT-FOXO1 regulatory pathway

(16,108) (Fig. 6B).

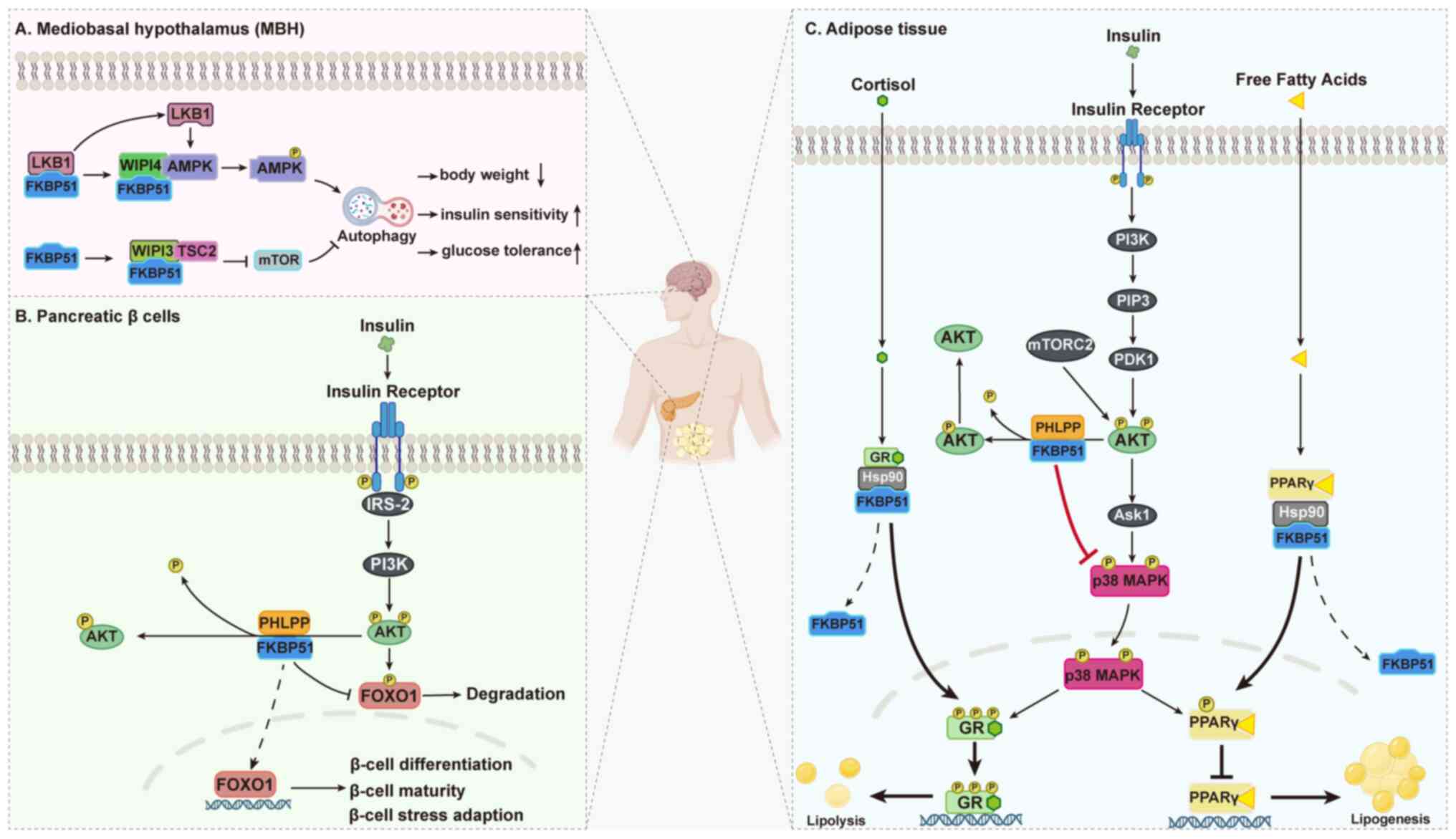

| Figure 6FKBP51 regulates metabolic

homeostasis by scaffolding kinase phosphorylation across multiple

tissues. Schematic representation of FKBP51-mediated regulation of

metabolic signaling. (A) In the MBH, FKBP51 interacts with WIPI4 to

recruit LKB1 to the AMPK complex, enhancing AMPK phosphorylation

and ULK1 activation to promote autophagy, while binding WIPI3-TSC2

to inhibit mTORC1 signaling. (B) In pancreatic β cells, FKBP51

scaffolds the phosphatase PHLPP to AKT, facilitating

dephosphorylation of AKT at Ser473 and decreasing FOXO1

phosphorylation, which preserves FOXO1 transcriptional activity and

supports β-cell differentiation, maturity and stress adaptation.

(C) In adipose tissue, FKBP51 suppresses AKT activity, indirectly

modulating p38 MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of PPARγ and GR,

thereby balancing lipogenesis and lipolysis. Together, these

mechanisms highlight FKBP51 as a dose-sensitive scaffold that

fine-tunes kinase phosphorylation to coordinate glucose

utilization, lipid storage and energy sensing, ultimately

maintaining systemic metabolic homeostasis. AMPK, AMP-activated

protein kinase; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1;

ULK1, UNC-51-like kinase 1; LKB1, liver kinase B1; WIPI, WD repeat

domain phosphoinositide-interacting protein; PHLPP, PH domain

leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase; AKT, protein kinase B;

FOXO1, forkhead box protein O1; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; PPARγ,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; MAPK,

mitogen-activated protein kinase; MBH, mediobasal hypothalamus;

HSP90, heat shock protein 90. |

In lipid metabolism, FKBP51 influences two key

nuclear receptors in adipocytes, peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor γ (PPARγ) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR), to balance

lipogenesis and lipolysis. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

phosphorylates PPARγ at Ser112, decreasing its transcriptional

activity and suppressing lipogenesis, while phosphorylation of GR

enhances its transcriptional activity, promoting lipolysis

(109). FKBP51 suppresses AKT

activity, which indirectly reduces p38 activation, thereby lowering

GR phosphorylation and lipolytic gene transcription while relieving

inhibitory phosphorylation of PPARγ to enhance lipogenic activity

(16). FKBP51, as part of the

Hsp90 chaperone complex, also retains GR and PPARγ in the

cytoplasm, preventing their nuclear translocation and

phosphorylation (31). Upon

ligand binding, FKBP52 replaces FKBP51 in the GR complex, enabling

GR nuclear import, whereas PPARγ is released from FKBP51 by protein

phosphatase 5 to dephosphorylate Ser112 and restore activity

(16). Notably, during early

adipocyte differentiation, FKBP51 translocates from mitochondria to

the nucleus, where it binds GRα and inhibits its transcriptional

activity, linking stress signaling to lipid metabolic gene

expression in a time-dependent manner (110) (Fig. 6C).

Collectively, these findings establish FKBP51 as a

central scaffold that orchestrates kinase phosphorylation to

fine-tune metabolic signaling. By bridging phosphatases and kinases

such as AKT, p38, AMPK and mTORC1, FKBP51 exerts precise control

over glucose utilization, lipid storage and autophagy. This

scaffold-dependent regulation allows cells to dynamically adapt to

nutritional and stress cues, thereby safeguarding systemic

metabolic balance. Importantly, the dose-sensitive nature of FKBP51

underscores its dual capacity to either maintain homeostasis or

drive metabolic dysfunction, highlighting its significance as a

pivotal regulator of proteostasis within energy metabolism.

Therapeutic targeting of FKBPs to restore

proteostasis

Targeting FKBPs offers a novel and unifying

therapeutic strategy to correct proteostasis imbalance across

diverse diseases. Given their structural modularity and central

positioning in protein quality control, FKBPs provide actionable

nodes for pharmacological intervention. As summarized in Table I, representative FKBP members

participate in distinct pathological contexts-from

neurodegeneration and cancer to cardiovascular and metabolic

disorders-through diverse proteostasis-related mechanisms and

corresponding therapeutic strategies. In neurodegenerative

diseases, FKBP12 accelerates α-Syn misfolding and aggregation in

PD, making it a candidate for non-immunosuppressive inhibitors such

as ElteN378, which block its interaction with α-Syn and thereby

mitigate proteotoxic stress (69). FKBP51 and FKBP52, on the other

hand, regulate tau conformational fate in AD. Ligands or interface

inhibitors that selectively modulate FKBP51-Hsp90 or FKBP52-tau

complexes may restore tau homeostasis and attenuate neurotoxicity

(12,77).

| Table IFKBPs as therapeutic targets to

restore proteostasis. |

Table I

FKBPs as therapeutic targets to

restore proteostasis.

| FKBP (protein;

gene) | Disease

context | Proteostasis axis

leveraged | Therapeutic

strategy | (Refs.) |

|---|

| FKBP12

(FKBP1A) | Parkinson's disease

(α-synuclein aggregation) | Protein folding and

aggregation control |

Non-immunosuppressive PPIase inhibitors

(e.g., ElteN378), peptidomimetics disrupting FKBP12-α-syn

interaction | (66,67,69) |

| FKBP51

(FKBP5) | Alzheimer's disease

(tau aggregation) | Chaperone-dependent

folding and oligomer stabilization | Selective FKBP51

ligands; inhibitors of FKBP51-Hsp90-tau interface | (77) |

| Cancer (melanoma,

prostate, pancreatic) | Post-translational

modification scaffolding (Akt/PTM balance) | Scaffold

modulators; PROTACs/ASOs to downregulate overexpression | (50-52) |

| Metabolic disorders

(obesity, insulin resistance) | Kinase

phosphorylation scaffolding (AKT, AMPK, mTORC1) | Small-molecule

FKBP51 modulators; PROTACs; siRNA/ASO therapies | (16,101,102) |

| FKBP52

(FKBP4) | Alzheimer's disease

(tau degradation/aggregation) | Autophagy-lysosome

pathway and Hsp90 co-chaperone network | Allosteric

inhibitors of PPIase pocket; inhibitors disrupting FKBP52-tau/Hsp90

interaction | (12,78,79) |

| Prostate/breast

cancers (hormone-driven growth) | Nuclear receptor

folding and trafficking | Inhibitors of

FKBP52-dynein interaction; blockade of FKBP52-Hsp90-AR/ER

complexes | (56-58) |

| FKBP12.6

(FKBP1B) | Heart failure,

atrial fibrillation (RyR2 destabilization) | Ion channel complex

stabilization | Rycals (e.g., S107)

to strengthen FKBP12.6-RyR2 binding | (94) |

| FKBP9/FKBP60

(FKBP9) | Glioblastoma (ER

stress adaptation) | ER proteostasis

(BiP-mediated folding and UPR tuning) | RNAi/ASO knockdown;

inhibitors of FKBP9-BiP interface | (40) |

| FKBP7/FKBP23

(FKBP7) | Pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (CAF-mediated ECM remodeling) | ER proteostasis and

extracellular matrix modulation | Inhibitors

preventing FKBP7-BiP competition; stromal-targeted strategies | (41) |

| FKBP10/FKBP65

(FKBP10) | NSCLC, CRC, RCC,

bladder cancer, glioma | Translational

homeostasis and collagen/protein maturation | PPIase inhibitors;

blockade of FKBP10-Hsp47 or FKBP10-prelamin A interactions;

RNAi/ASO knockdown | (10,42,45,46) |

In oncology, ER-resident proteins FKBP9, FKBP7 and

FKBP10 enable tumor cells to adapt to translational overload and ER

stress. FKBP9 sustains glioblastoma growth by restraining

IRE1α-XBP1 signaling, while FKBP7 in pancreatic cancer-associated

fibroblasts remodels collagen deposition to enhance invasion

(40,41). FKBP10, overexpressed in multiple

solid tumors, supports ribosomal translation and stabilizes

structural proteins (10,42).

These functions highlight FKBPs as tractable targets for either

enzymatic inhibition, interference with client binding (e.g., BiP,

Hsp47), or RNA interference/antisense oligonucleotide-based

knockdown to impair tumor proteostasis and sensitize cancers to

therapy.

In the cardiovascular system, FKBP12.6 stabilizes

the RyR2 calcium channel and prevents diastolic calcium leak. Small

molecules such as rycals (e.g., S107) that strengthen FKBP12.6-RyR2

binding have shown promise in preclinical HF and arrhythmia models

by restoring calcium homeostasis (94). In metabolism, FKBP51 acts as a

scaffold to fine-tune kinase phosphorylation, balancing AKT, AMPK

and mTORC1 signaling. Selective FKBP51 modulators, degraders or

oligonucleotide-based strategies represent emerging tools to

correct its dose-dependent bidirectional effects on glucose

tolerance, lipid balance and autophagy (16,100,101) (Table I).

Collectively, these examples establish FKBPs as a

novel class of proteostasis regulators that bridge molecular

folding networks with system-level disease mechanisms. Therapeutic

strategies tailored to individual family members and disease

contexts not only expand our understanding of the

proteostasis-disease axis but also provide a foundation for

precision interventions targeting multi-organ disorders.

Proteostasis-regulating roles of

less-studied FKBPs across disease contexts

While much attention in the literature has focused

on canonical FKBPs such as FKBP51, FKBP52 and FKBP12, emerging

evidence highlights the functional significance of other,

less-studied FKBP family members in regulating proteostasis across

diverse disease contexts. FKBP38 (FKBP8) regulates epithelial

barrier integrity in inflammatory bowel disease by recruiting MLCK1

to the perijunctional actomyosin ring, and also modulates Bcl-2

stability and autophagy in glioblastoma to preserve tumor cell

proteostasis (111,112). FKBPL has been shown to interact

with DLK to inhibit its kinase activity and promote

lysosome-dependent degradation, thereby maintaining axonal

proteostasis in neuronal injury (113). In connective tissue disorders

such as vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, FKBP22 (FKBP14) functions

as an ER-resident PPIase that ensures proper collagen folding and

secretion (33). FKBP25 (FKBP3)

influences proteostasis by suppressing mTORC1 activity and

promoting autophagy, while its stability is tightly regulated by

ubiquitination (36). Table II summarizes the current

understanding of these underexplored FKBPs, their associated

pathologies and the key mechanisms by which they influence protein

homeostasis.

| Table IIProteostasis-regulating roles of

less-studied FKBPs across disease contexts. |

Table II

Proteostasis-regulating roles of

less-studied FKBPs across disease contexts.

| FKBP (protein;

gene) | Disease

context | Mechanism of

proteostasis regulation | (Refs.) |

|---|

| FKBP38

(FKBP8) | Inflammatory bowel

disease | Binds MLCK1 to

facilitate its recruitment to the perijunctional actomyosin ring,

regulating epithelial barrier protein stability | (111) |

| Glioblastoma | Modulates Bcl-2

stability and participates in protein folding and autophagy,

maintaining tumor cell proteostasis | (112) |

| FKBPL | Neuronal injury

(axon degeneration, RGC death) | Interacts with DLK

to inhibit its kinase activity and promotes lysosome-dependent

degradation, regulating axonal proteostasis | (113) |

| FKBP22

(FKBP14) | Connective tissue

disorders (vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) | ER-resident PPIase

catalyzing proline isomerization in collagen, ensuring proper

collagen folding and secretion | (33) |

| FKBP25

(FKBP3) | Cancer | Suppresses mTORC1

activity and promotes autophagy; its stability is regulated by

ubiquitination, influencing protein degradation and tumor

growth | (36) |

| FKBP51

(FKBP5) | Huntington's

disease | PPIase activity

modulates folding and aggregation of mHTT; inhibition enhances

autophagic clearance of mHTT | (9) |

Conclusion

Protein homeostasis is fundamental to the

preservation of cellular integrity and its disruption represents a

common pathological axis across cancer, neurodegeneration,

cardiovascular dysfunction and metabolic disorders. This review

highlights FKBPs as versatile modulators of proteostasis, acting

through diverse mechanisms including conformational control,

chaperone-assisted folding, complex stabilization, stress

adaptation and selective degradation. By integrating these

processes, FKBPs emerge not merely as accessory factors but as

central regulators that shape the fate of disease-related proteins

and determine cellular resilience or vulnerability.

The synthesis of the present review demonstrates

that distinct FKBP isoforms exert disease-specific functions:

ER-resident members such as FKBP7/9/10 orchestrate tumor proteome

remodeling, FKBP12 drives pathogenic protein aggregation in PD,

FKBP51 and FKBP52 modulate tau balance in AD, FKBP12.6 safeguards

cardiac rhythm by stabilizing RyR2 and FKBP51 fine-tunes metabolic

kinase signaling to maintain systemic balance. These findings

collectively establish FKBPs as critical bridges linking

proteostasis to multi-system pathogenesis.

Importantly, their structural modularity and

context-dependent functions position FKBPs as novel and druggable

nodes within proteostasis networks. Therapeutic strategies

targeting FKBP-client interactions, their scaffold functions or

their enzymatic activity provide unprecedented opportunities to

restore proteostasis in disease states. Moving forward, integrating

chemical biology, structural proteomics and translational studies

will be essential to exploit FKBPs as precision targets. By

reframing FKBPs within the proteostasis paradigm, this review not

only expands our conceptual understanding of disease biology but

also charts a new course for therapeutic innovation across multiple

organ systems.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZL was involved in the conceptualization of the

study and in writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. XL

contributed to the writing-review and editing, performed

visualization and provided supervision. HZ obtained resources,

acquired funding and was involved in writing-review and editing.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific

writing

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools ChatGPT (GPT-5; 2025 version; OpenAI) were used

to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or to

generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and edited

the content produced by the artificial intelligence tools as

necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of

the present manuscript'

Abbreviations:

|

AD

|

Alzheimer's disease

|

|

AF

|

atrial fibrillation

|

|

AKT

|

protein kinase B

|

|

AMPK

|

AMP-activated protein kinase

|

|

AR

|

androgen receptor

|

|

ASO

|

antisense oligonucleotide

|

|

BiP

|

binding immunoglobulin protein

|

|

CAF

|

cancer-associated fibroblast

|

|

CaMKII

|

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein

kinase II

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

ER

|

endoplasmic reticulum

|

|

FKBP

|

FK506-binding protein

|

|

HF

|

heart failure

|

|

Hsp90

|

heat shock protein 90

|

|

mTORC1

|

mechanistic target of rapamycin

complex 1

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer

of activated B cells

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

PD

|

Parkinson's disease

|

|

PPIase

|

peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans

isomerase

|

|

PROTAC

|

proteolysis targeting chimera

|

|

PTM

|

post-translational modification

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

RyR2

|

ryanodine receptor 2

|

|

Ub

|

ubiquitin

|

|

UPR

|

unfolded protein response

|

Acknowledgements

The figures of this paper were prepared with

Figdraw 2.0 and BioRender (https://www.biorender.com).

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81873523).

References

|

1

|

Díaz-Hung ML and Hetz C: Proteostasis and

resilience: On the interphase between individual's and

intracellular stress. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 33:305–317. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hetz C: Adapting the proteostasis capacity

to sustain brain healthspan. Cell. 184:1545–1560. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Weinberg J, Gaur M, Swaroop A and Taylor

A: Proteostasis in aging-associated ocular disease. Mol Aspects

Med. 88:1011572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gressler AE, Leng H, Zinecker H and Simon

AK: Proteostasis in T cell aging. Semin Immunol. 70:1018382023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lu Q, Qin X, Chen C, Yu W, Lin J, Liu X,

Guo R, Reiter RJ, Ashrafizadeh M, Yuan M and Ren J: Elevated levels

of alcohol dehydrogenase aggravate ethanol-evoked cardiac

remodeling and contractile anomalies through FKBP5-yap-mediated

regulation of ferroptosis and ER stress. Life Sci. 343:1225082024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jeanne X, Török Z, Vigh L and Prodromou C:

The role of the FKBP51-Hsp90 complex in Alzheimer's disease: An

emerging new drug target. Cell Stress Chaperones. 29:792–804. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nakamura K, Aoyama-Ishiwatari S, Nagao T,

Paaran M, Obara CJ, Sakurai-Saito Y, Johnston J, Du Y, Suga S,

Tsuboi M, et al: Mitochondrial complexity is regulated at

ER-mitochondria contact sites via PDZD8-FKBP8 tethering. Nat

Commun. 16:34012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Akbar M, Toppo P and Nazir A: Ageing,

proteostasis, and the gut: Insights into neurological health and

disease. Ageing Res Rev. 101:1025042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bailus BJ, Scheeler SM, Simons J, Sanchez

MA, Tshilenge KT, Creus-Muncunill J, Naphade S, Lopez-Ramirez A,

Zhang N, Lakshika Madushani K, et al: Modulating FKBP5/FKBP51 and

autophagy lowers HTT (huntingtin) levels. Autophagy. 17:4119–4140.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cai HQ, Zhang MJ, Cheng ZJ, Yu J, Yuan Q,

Zhang J, Cai Y, Yang LY, Zhang Y, Hao JJ, et al: FKBP10 promotes

proliferation of glioma cells via activating AKT-CREB-PCNA axis. J

Biomed Sci. 28:132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mei L, Zheng YM, Song T, Yadav VR, Joseph

LC, Truong L, Kandhi S, Barroso MM, Takeshima H, Judson MA and Wang

YX: Rieske iron-sulfur protein induces FKBP12.6/RyR2 complex

remodeling and subsequent pulmonary hypertension through

NF-κB/cyclin D1 pathway. Nat Commun. 11:35272020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chambraud B, Daguinot C, Guillemeau K,

Genet M, Dounane O, Meduri G, Poüs C, Baulieu EE and Giustiniani J:

Decrease of neuronal FKBP4/FKBP52 modulates perinuclear lysosomal

positioning and MAPT/Tau behavior during MAPT/Tau-induced

proteotoxic stress. Autophagy. 17:3491–3510. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ke H, Chen Z, Chen L, Zhang H, Wang Y,

Song T, Bi A, Li Q, Sheng H, Jia Y, et al: FK506-binding proteins:

Emerging target and therapeutic opportunity in multiple tumors. Int

J Biol Macromol. 307:1419142025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jiang L, Chakraborty P, Zhang L, Wong M,

Hill SE, Webber CJ, Libera J, Blair LJ, Wolozin B and Zweckstetter

M: Chaperoning of specific tau structure by immunophilin FKBP12

regulates the neuronal resilience to extracellular stress. Sci Adv.

9:eadd97892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Richardson SJ, Thekkedam CG, Casarotto MG,

Beard NA and Dulhunty AF: FKBP12 binds to the cardiac ryanodine

receptor with negative cooperativity: Implications for heart muscle

physiology in health and disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol

Sci. 378:202201692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Smedlund KB, Sanchez ER and Hinds TD Jr:

FKBP51 and the molecular chaperoning of metabolism. Trends

Endocrinol Metab. 32:862–874. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cozachenco D, Ribeiro FC and Ferreira ST:

Defective proteostasis in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev.

85:1018622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dikic I and Schulman BA: An expanded

lexicon for the ubiquitin code. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:273–287.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Nixon RA and Rubinsztein DC: Mechanisms of

autophagy-lysosome dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25:926–946. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen X, Shi C, He M, Xiong S and Xia X:

Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic

targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Agam G, Atawna B, Damri O and Azab AN: The

Role of FKBPs in complex disorders: Neuropsychiatric diseases,

cancer, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cells. 13:8012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stauffer WT, Goodman AZ and Gallay PA:

Cyclophilin inhibition as a strategy for the treatment of human

disease. Front Pharmacol. 15:14179452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhuang S, Chakraborty P and Zweckstetter

M: Regulation of tau by peptidyl-prolyl isomerases. Curr Opin

Struct Biol. 84:1027392024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Deutscher RCE, Meyners C, Repity ML,

Sugiarto WO, Kolos JM, Maciel EVS, Heymann T, Geiger TM, Knapp S,

Lermyte F and Hausch F: Discovery of fully synthetic FKBP12-mTOR

molecular glues. Chem Sci. 16:4256–4263. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hanaki S and Shimada M: Impact of FKBP52

on cell proliferation and hormone-dependent cancers. Cancer Sci.

114:2729–2738. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Soto OB, Ramirez CS, Koyani R,

Rodriguez-Palomares IA, Dirmeyer JR, Grajeda B, Roy S and Cox MB:

Structure and function of the TPR-domain immunophilins FKBP51 and

FKBP52 in normal physiology and disease. J Cell Biochem.

125:e304062024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Singh MK, Shin Y, Ju S, Han S, Choe W,

Yoon KS, Kim SS and Kang I: Heat shock response and heat shock

proteins: Current understanding and future opportunities in human

diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 25:42092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gu J, He Y, He C, Zhang Q, Huang Q, Bai S,

Wang R, You Q and Wang L: Advances in the structures, mechanisms

and targeting of molecular chaperones. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 10:842025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pokhrel S, Devi S and Gestwicki JE:

Chaperone-dependent and chaperone-independent functions of

carboxylate clamp tetratricopeptide repeat (CC-TPR) proteins.

Trends Biochem Sci. 50:121–133. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|