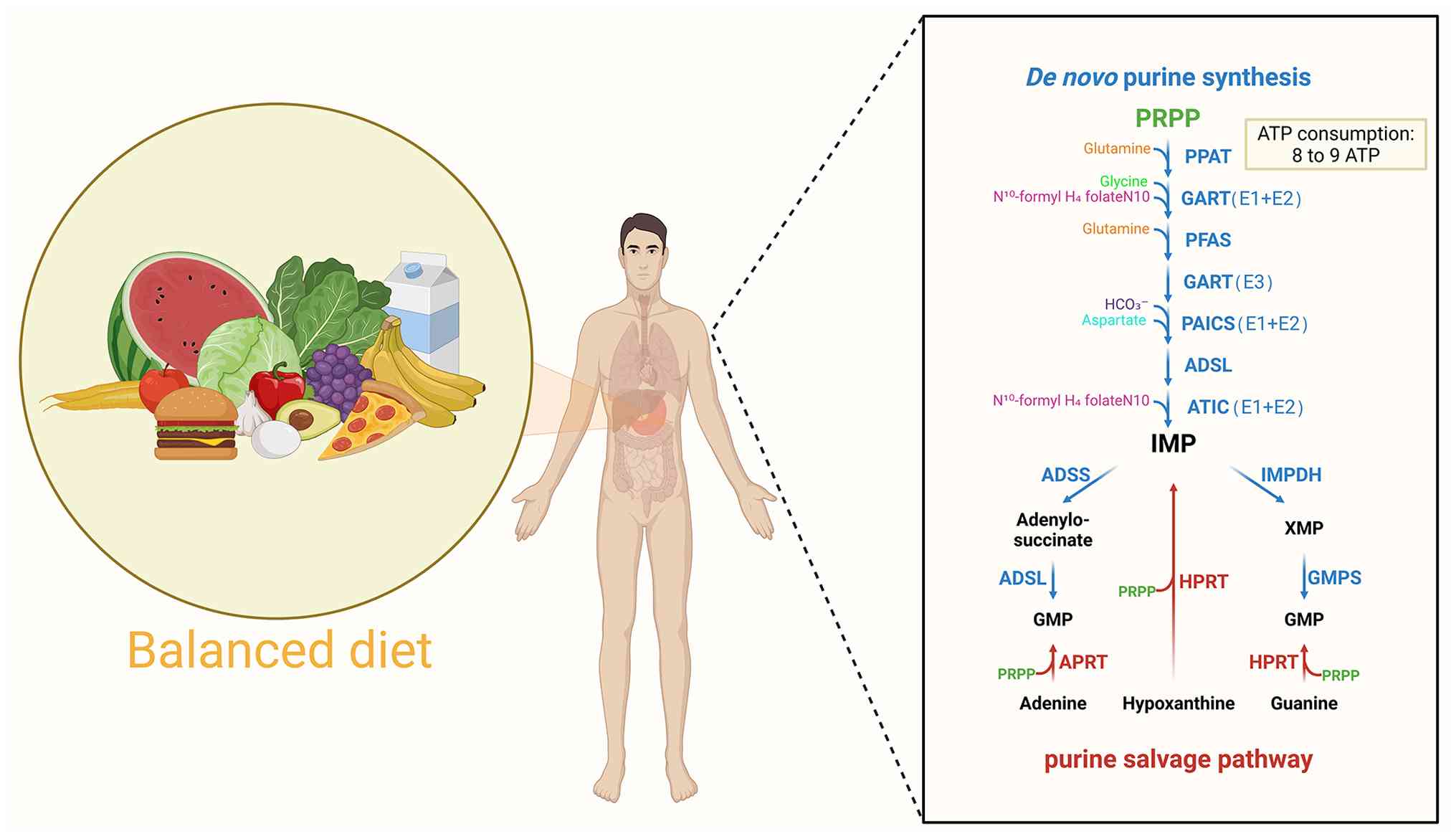

Inosine monophosphate (IMP), as a crucial

intermediate in the metabolism of purine nucleotides, is essential

for both de novo synthesis and salvage synthesis pathways

(1). The body effectively

recovers ~90% of free bases in the salvage pathway through

hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase, using resources to

synthesize the necessary IMP and guanine monophosphate. The regular

demands of the body are mainly satisfied by this mechanism

(2). However, salvage synthesis

is unable to keep up with the growing need for purines due to the

rapid proliferation of tumor cells. The primary mechanism at this

stage is de novo synthesis (3,4),

which uses 5'-ribose-5'-phosphate as its absolute starting

substrate (a common precursor for all purine nucleotide synthesis,

usually not listed separately) and catalyzes reactions through

trifunctional enzymes [trifunctional glycinamide nucleoside

transcarboxylase (GART) protein containing glycinamide nucleoside

synthase, GART and aminoimidazole nucleoside synthase domains],

bifunctional enzymes [phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase and

succinocarboxamide synthetase (PAICS) containing

carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide and

succinylaminoimidazolecarboxamide ribonucleotide domains],

5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase/IMP

cyclohydrolase (ATIC) containing 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide

ribonucleotide (AICAR) and IMP cyclohydrolase domains] and

monofunctional enzymes [phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate

amidotransferase (PPAT), formylglycinamide ribonucleotide synthase

(FGAMS) and adenylosuccinate lyase (ADSL)] (5-7).

This process consumes large amounts of ATP, glutamine, formate,

glycine, aspartate and carbon dioxide to synthesize the necessary

purine nucleotides. Among these, IMP is crucial for adenine and

guanine monophosphate, which are indicators of cellular

proliferation and development (5,8).

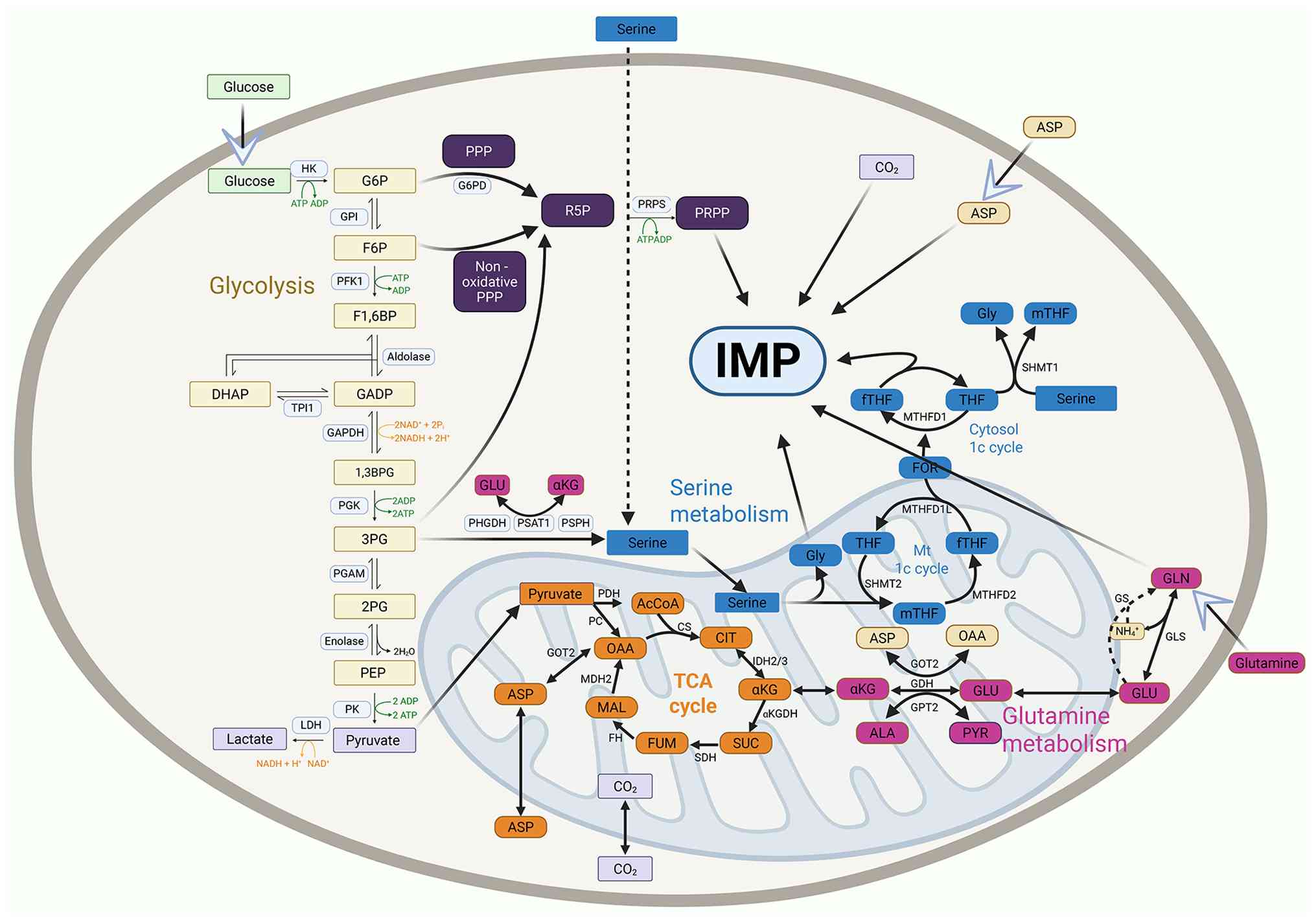

Furthermore, the need for purine synthesis precursors is

significantly increased because of the rapid proliferation

characteristics of tumor cells. This drives the regulation of

related metabolic pathways, such as reprogramming of glucose

metabolism, regulation of serine and glutamine metabolism, the

one-carbon cycle and mitochondrial function. Collectively, these

processes constitute an extensive metabolic network that surrounds

the primary axis of IMP metabolism (9-11). Major metabolic pathways are

intricately linked and mutually reinforced within the dysregulated

tumor cell, continuously delivering IMP to support its rampant

proliferation (11). These

pathways also include RAS-ERK, PI3K/AKT-mTORC1 and

Hippo-Yes-associated protein (YAP), which modulate various enzymes

and metabolic changes through demand-driven and feedback-regulated

mechanisms, thereby maintaining the uncontrolled growth of tumor

cells. Numerous enzymes, including hypoxanthine dehydrogenase,

purinosomes, which are multi-enzyme complexes responsible for de

novo purine biosynthesis, and modifications in the immune

microenvironment linked to hypoxanthine metabolism, have been

identified as important targets for preventing tumors or

suppressing pathogens. Although it has been thoroughly examined in

disciplines such as protozoology and immunology, research on its

function in tumor cells has accelerated recently. The objective is

to develop novel IMP inhibitors for treating tumors (12-14) (Fig. 1).

Numerous previous studies have suggested targeting

IMP metabolism as a highly promising cancer therapeutic strategy,

precisely because of the critical role of hypoxanthine. We have

developed an integrated conceptual framework that includes

precursor supply, dynamic enzyme regulation and signaling pathway

modulation based on a series of metabolic reprogramming events in

tumor cells. This framework has excellent potential to understand

and exploit IMP metabolism in tumor cells. Additionally, targeted

inhibition strategies for hypoxanthine dehydrogenase and the

effects of IMP metabolism on the immune microenvironment were

systematically reviewed. Certain techniques have demonstrated

successful reduction of tumor cell proliferation in preclinical

models. These studies shed light on the physiological significance

of IMP synthesis regulation and offer more precise targets and

theoretical foundations for developing IMP metabolism-targeted

cancer therapies.

Aerobic glycolysis in tumor cells serves as the

foundation for producing IMP synthesis precursors. Most cancer

cells adhere to the Warburg effect, which prioritizes glycolysis to

convert glucose into lactate even in the presence of abundant

oxygen, whereas normal cells usually generate energy by

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. According to the theory by

early Warburg, tumor cells prefer aerobic glycolysis, an

inefficient ATP production method that yields only 2 ATP molecules,

whereas oxidative phosphorylation produces 36 ATP. Warburg

explained that this was a passive adaptation due to mitochondrial

dysfunction caused by hypoxia, lactate accumulation and other

factors, which results in irreversible respiratory impairment

(15). However, subsequent

studies revealed that most cancer cells have normal mitochondrial

function and are still capable of oxidative phosphorylation; their

metabolic activity has changed to glycolysis (16-18). It has been found that cancer

cells preferentially use aerobic glycolysis to meet the

biosynthetic demands of proliferation by allocating glucose-derived

carbon toward biosynthesis rather than complete oxidative

phosphorylation. The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) converts ~10%

of glucose into 5-phosphoribose to supply nucleotide synthesis;

another portion is metabolized into acetyl-CoA for lipid synthesis;

and only a small fraction is completely oxidized to carbon dioxide

(CO2) to meet basic ATP requirements. Cancer cells

coordinate the PPP with glutamine metabolism in an integrated

process, in addition to allocating carbon through aerobic

glycolysis (19). A total of

three vital enzymes are critical to the aerobic glycolysis of tumor

cells: Hexokinase 2 (HK2), pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) and lactate

dehydrogenase A (LDH-A) (20).

HK2 is highly expressed in many tumors and localizes to the outer

mitochondrial membrane to bind with the voltage-dependent anion

channel (VDAC) along with hexokinase 1 and hexokinase domain

component 1. This arrangement allows direct use of VDAC-derived ATP

for glucose phosphorylation, thereby improving hexokinase activity,

accelerating glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) synthesis, modulating

glycolytic flux and inhibiting G-6-P accumulation (21). By contrast, LDH-A inhibition

significantly suppresses cell proliferation. LDH-A-specific

inhibitors (such as oxaloacetate) block lactate production in tumor

cells, causing intracellular carbon accumulation, impaired

diversion of glycolytic intermediates toward nucleotide and lipid

synthesis, decreased NAD+ regeneration, reduced

glycolytic flux and diminished NADPH production, because glutamine

metabolism depends on glycolysis-coupled NAD+

regeneration, ultimately leading to growth arrest or apoptosis.

Therefore, LDH-A is crucial for preserving the precursors needed

for IMP synthesis (22).

Furthermore, proliferative signals inhibit the activity of PKM2, a

tumor-specific isoform. Glycolytic intermediates, such as

3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), in their

low-activity dimeric forms, are inefficiently converted to pyruvate

and are instead redirected into anabolic pathways. Particularly,

3-PG and fructose-6-phosphate enter the non-oxidative branch of the

PPP to produce ribose-5-phosphate, whereas PEP facilitates the

biosynthesis of alanine and serine (23,24).

The PPP, which is an essential part of carbohydrate

metabolism, is primarily responsible for producing

5'-phosphoribulose and NADPH. The former serves as a critical

precursor for IMP synthesis within the body, whereas the latter is

essential for maintaining redox homeostasis (25). The PPP consists of two

functionally complementary branches: Oxidative and non-oxidative.

The oxidative branch in tumor cells, driven mainly by

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and 6-phosphogluconate

dehydrogenase, produces NADPH to support antioxidant defense and

lipid biosynthesis, while the non-oxidative branch is adapted to

hypoxic and highly proliferative conditions. This branch

circumvents the limitations of oxidative phosphorylation under

hypoxia by converting glycolytic intermediates into 5-phosphoribose

independently of mitochondria. It is catalyzed by

transketolase-like 1 (TKTL1) and transaldolase. This reversible

pathway supplies >60% of the 5-phosphoribose required by tumor

cells and dynamically connects glycolysis to biosynthetic pathways

to distribute carbon in accordance with energetic and anabolic

requirements (26,27). These two branches are

interconnected rather than independent: The oxidative branch

produces NADPH, which is generated by the oxidative branch,

protects non-oxidative enzymes such as TKTL1 from reactive oxygen

species (ROS)-mediated damage, whereas the non-oxidative branch

replenishes G-6-P for the oxidative pathway by recycling

intermediates into glycolysis, forming a metabolic cycle that

collectively supports tumor proliferation, apoptosis resistance and

metastatic potential (26). It

is now recognized that tumor cells exhibit upregulation of the PPP

pathway, particularly in rapidly growing tumors such as

glioblastoma. Increased expression of enzymes such as G6PD

indicates enhanced PPP activity, providing an abundance of

ribose-5-phosphate and promoting de novo IMP synthesis.

Elevated IMP, adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and guanosine

monophosphate (GMP) levels were verified in five patient-derived

glioblastoma models, maintaining cellular proliferation and

stemness. Furthermore, concurrent NADPH synthesis also improves

invasive phenotypes by maintaining tumor cell redox homeostasis. In

conclusion, tumor cells modulate the PPP pathway to boost

5-phosphoribose needed for IMP synthesis and NADPH to maintain a

stable tumor microenvironment (28). It has been demonstrated that

combining therapy with G6PD and glycolysis inhibitors significantly

improves radiosensitivity in human gliomas, suggesting that this

combination may be a novel targeted treatment approach (29).

Glucose is taken up by cancer cells and metabolized

into precursors such as serine and glycine, which are essential for

one-carbon metabolism and provide the carbon units needed to

synthesize IMP and glycine (30). The primary source of cytoplasmic

serine is extracellular uptake through the

alanine/serine/cysteine/threonine transporter 1 and the diversion

of ~10% of the glycolytic intermediate 3-PG into de novo

serine synthesis, which is catalyzed by phosphoglycerate

dehydrogenase (PHGDH). Serine is subsequently produced through

transamination by phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 and

dephosphorylated by phosphoserine phosphatase. Cytoplasmic serine

hydroxymethyltransferase 1 (SHMT1) or mitochondrial serine

hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2) then catalyze the combination

with tetrahydrofolate (THF) to produce glycine and

5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (31-33). Most cancer cells preferentially

use mitochondrial SHMT2 to boost mitochondrial folate synthesis

rather than cytoplasmic SHMT1 to convert serine to glycine; SHMT2

knockout leads to increased accumulation of AICAR, an intermediate

in IMP synthesis (34). It is

interesting to note that SHMT2 generates S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)

through one-carbon metabolism, increasing N6-methyladenosine

(m6A) modification of PPAT mRNA. This modification

enables recognition and stabilization by insulin-like growth factor

(IGF) 2 mRNA-binding protein 2, which eventually increases PPAT

expression to promote renal cell cancer development (35). Tumor cells synthesize required

IMP through extracellular serine uptake when serine availability is

limited. This finding suggests that lowering IMP synthesis may

enhance the efficacy of therapies in specific tumor cells (36). The primary carbon source for

purine ring formation in the cancerous tissues of non-small cell

lung cancer (NSCLC) is glucose. This process involves the

activation and compartmentalization of the glucose-to-serine

pathway in the cytoplasm, as well as an enhanced reverse one-carbon

flux that reduces the incorporation of external serine into purine

synthesis (30,37). Numerous types of tumor cell have

been shown to exhibit a significant increase in gene expression

linked to serine metabolism. For instance, PHGDH is markedly

overexpressed in melanoma, breast cancer and NSCLC, particularly in

70% of triple-negative breast cancers, which is associated with

poor prognosis (37,38).

Serine metabolism and glycolysis are closely related

due to complex feedback regulation. Elevated serine levels activate

the low-activity M2 isoform of PKM2, which catalyzes the conversion

of phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate in the final stage of glycolysis

(39). This process maintains

glycolytic flux while restricting diversion of 3-PG into de

novo serine synthesis. Serine depletion lowers PKM2 activity,

impairs the terminal glycolytic step and results in 3-PG

accumulation that is redirected into the serine biosynthetic

pathway. Simultaneously, elevated 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PG)

activates PHGDH, a crucial enzyme in serine and glycine synthesis,

thereby increasing de novo serine production; 2-PG is

converted to 3-PG by phosphoglycerate mutase, which is immediately

upstream of PHGDH. As a result, rapid tumor proliferation and high

IMP consumption cause serine deficiency, inhibit PKM2 activity,

increase 3-PG accumulation and promote compensatory serine

synthesis. This feedback circuit partially explains the limited

effectiveness of the purine synthesis inhibitor methotrexate.

Furthermore, ribonucleotides-purine biosynthetic intermediates-can

allosterically activate PKM2 under glucose-restricted conditions,

offering an additional adaptive mechanism for cancer cell survival

(40). Thus, focusing on the

association between serine metabolism and glycolysis may provide a

viable strategy for managing cell growth and developing cancer

therapies.

Glutamine is necessary for cancer cell proliferation

and, together with its metabolite aspartate, serves as a crucial

precursor for IMP synthesis. Rapid tumor proliferation diverts

vital tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle) intermediates toward

biosynthesis, disrupting the balance of the TCA cycle. Glutamine is

converted to glutamate through the glutaminase pathway and then

metabolized by glutamate dehydrogenase 1 into α-ketoglutarate,

which enters the TCA cycle to replenish carbon sources (41,42). Furthermore, α-ketoglutarate can

be further oxidized to produce succinate and fumarate. These

metabolites assist the TCA cycle in cancer cells by providing ATP,

NADH and FADH2. They also act as essential tumor

metabolites that promote rapid tumor cell proliferation (41,43,44). Additionally, glutamate is

converted by glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) and

glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) into alanine and aspartate,

which provide tumor cells with nitrogen sources. In particular, GPT

catalyzes the conversion of glutamate and pyruvate into

α-ketoglutarate and alanine, with α-ketoglutarate replenishing the

TCA cycle and alanine supporting protein synthesis. It has been

demonstrated that GPT2 has a crucial role in breast cancer,

glioblastoma and KRAS-driven colorectal cancer (45-47). GOT catalyzes the transformation

of glutamate and oxaloacetate into α-ketoglutarate and aspartate.

Endogenous synthesis is essential since cancer cells have a limited

ability to absorb exogenous aspartate. Aspartate production exerts

a central oncogenic function by promoting nucleotide and protein

synthesis and contributing to the malate-aspartate shuttle, which

produces NADPH to maintain tumor cell redox homeostasis (43,48). Additionally, asparagine

synthetase (ASNS) utilizes glutamate as a substrate to produce

asparagine. This process consumes significant amounts of aspartate

and stimulates its synthesis in tumor cells (49). Research has revealed the

involvement of ASNS in tumor development and metastasis, in

addition to its link to poor survival rates in several cancers,

including NSCLC (50). Notably,

glutamate catalyzed from glutamine serves as an important precursor

for glutathione (GSH). It produces GSH, an essential reducing agent

that scavenges ROS and protects cancer cells from apoptosis,

together with cysteine and glycine (51). Furthermore, the ability of this

metabolic pathway to convert glutamine into biosynthetic precursors

is particularly critical in hypoxic conditions (52).

Mitochondria, as the primary metabolic organelles in

cells, coordinate cellular energy production and provide the raw

materials needed for cell proliferation, given the marked demand of

tumor cells for TCA cycle precursors and the energy produced by

de novo IMP synthesis. Their critical role in the IMP

metabolic pathway is undeniable. Mitochondria replenish TCA cycle

intermediate metabolites by oxidizing glutamine-derived

α-ketoglutarate or acetyl-CoA and maintain TCA cycle activity

(53). Furthermore,

mitochondrial respiration produces aspartate, which increases IMP

synthesis in low-oxygen environments, promoting tumor growth and

the progression of cancer (54,55). The blocking of mitochondrial

respiration reduces intracellular aspartate levels, which in turn

restricts the production of asparagine, which is derived from

aspartate (56). Interestingly,

fibroblasts associated with cancer serve as an additional source of

aspartate, which promotes the proliferation of tumor cells

(54). Furthermore, SHMT2

converts serine into glycine and one-carbon units in mitochondria,

whereas mitochondria produce ATP and CO2 by oxidative

phosphorylation (57).

Therefore, mitochondria serve as factories for the synthesis of

de novo IMP precursors and are crucial for IMP metabolism.

Additionally, purinosomes involved in IMP synthesis are

intrinsically linked to mitochondria. Targeting mitochondrial

function may be a viable strategy for inhibiting purine

biosynthesis due to this mitochondrial dependence (8) (Fig.

2).

The rate-limiting enzyme is the one that catalyzes

the slowest step in a metabolic pathway; its activity controls the

overall flux of the pathway and is a crucial component of metabolic

regulation. Tumor cells have been demonstrated to stimulate

proliferation by enzymatically modulating the metabolism of

hypoxanthine nucleotides. Rate-limiting enzymes such as

phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) synthetase (PRPS), PPAT and

IMPDH are important players. Additionally, purinosomes, functional

assemblies of enzymes involved in de novo purine synthesis,

are critical for the metabolic reprogramming of nucleotides in

tumors. This review systematically summarizes how these enzymes

dynamically modulate IMP production to satisfy tumor proliferative

demands and explores variations in IMPDH dependency among tumor

cell types (58-72) (Table I).

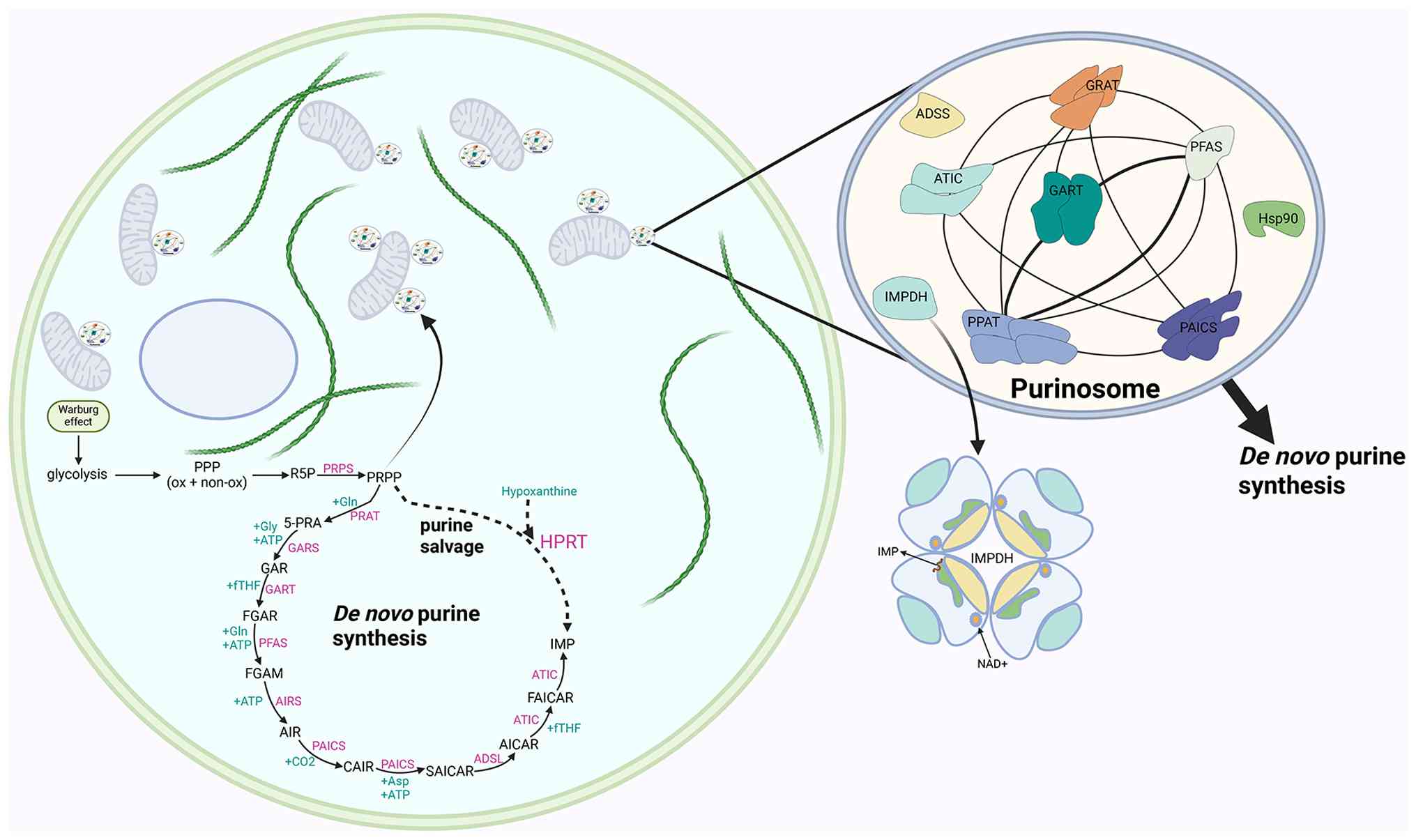

Purinosomes, initially identified in 2008, are

dynamic intracellular structures made up of six enzymes involved in

de novo purine synthesis. The core scaffold comprises PPAT,

GART and FGAMS, while PAICS, ADSL and ATIC are associated with

peripheral structures. This spatial organization facilitates

metabolic channeling in order to produce IMP and downstream purines

to meet cellular demands effectively. Notably, purinosomes are

functionally coupled to mitochondria, suggesting a link between

de novo purine synthesis and cellular energy metabolism. The

primary function of purinosomes in growth-related pathways makes

them attractive therapeutic targets, despite the fact that their

significance in cancer is still unclear (8,73-75). Its formation is driven by reduced

cellular purine levels and increased metabolic demand. Enzymes of

the de novo synthesis pathway assemble into purinosomes when

cells require high purine levels, such as during

G1/S-phase proliferation or when salvage pathways are

compromised. This organization improves metabolic efficiency by

channeling substrates, limiting diffusion or degradation of

intermediates, and increasing de novo synthesis flux by

~50%, thereby increasing IMP production threefold as compared to

normal growth conditions. Pyrimidine body production rises by 25%

in cells with impaired salvage pathways, such as HGPRT knockout

cells, thereby compensating to maintain purine supply. Pathway flux

may be markedly more noticeable during the G1 phase of

cell proliferation because these investigations are asynchronous

(8,76,77). Functional loss of any purinosomes

component disrupts its stability and structure (78,79), and purine supplementation causes

complete or significant depletion of purinosomes (8). According to time-lapse fluorescence

microscopy analysis, the proportion of purinosome-positive cells

peaked during the G1 phase, providing essential purine

nucleotides for cell growth, and progressively decreases throughout

the course of the remaining cell cycle. Interestingly, expression

levels of de novo purine synthesis enzymes did not change

across the cell cycle, suggesting that mechanisms other than

purinosome assembly and disassembly may also regulate this process

(77). Available evidence

suggests that a significant portion of purinosomes in

purinosome-positive cells localize to mitochondria rather than

being randomly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, indicating a

close mitochondrial association due to the high energetic needs of

purine synthesis. Microtubules provide a structural foundation for

purinosome function, as evidenced by the spatial regulation of

purinosome assembly being dependent on microtubules. Purinosomes

travel along the microtubule network, and microtubule

depolymerization disrupts their mitochondrial colocalization,

leading to a roughly 50% reduction in the flux of de novo

purine synthesis. Super-resolution fluorescence microscopy further

revealed colocalization of purinosomes with mitochondria, with at

least nine purinosome components located at the

microtubule-mitochondria interface. This organization allows

purinosomes to directly access ATP, one-carbon units (formate),

aspartate and glutamine, thereby maximizing the efficiency of

purine synthesis. Notably, purinosome formation is increased by

defects in mitochondrial functions, including electron transport or

oxidative phosphorylation, whereas excessive purinosome

accumulation can impair mitochondrial function (5,80,81). Although the role of purine

synthase in cancer has not been extensively studied, it is a

promising target for possible treatments due to its crucial

involvement in notable cellular growth pathways. Furthermore, its

dependence on mitochondria suggests that targeting mitochondria can

be a strategy to inhibit purine biosynthesis (8). Additionally, molecular chaperones

heat shock protein (HSP70)/HSP90 actively contribute to purinosomes

assembly, stability maintenance and functional execution by direct

binding, folding assistance and degradation regulation. They serve

as essential regulators of the biophysical properties and

structural integrity of purinosomes, and they also provide a

potential therapeutic strategy targeting purinosomes by interfering

with chaperone function (82-84). Tumor cells use mechanisms to

regulate the assembly and disassembly of purinosomes or their

interactions with other organelles to meet their high IMP demand.

Tumor cells use microtubules to assemble purinosomes when IMP is

deficient, a crucial adaptive mechanism that enables cancer cells

to respond to purine scarcity. The process can be inhibited by

docetaxel, a microtubule-stabilizing chemotherapeutic agent

(85) (Fig. 3).

Numerous vital concerns about the structure and

function of purinosomes remain unresolved despite initial

observations. The present review summarized the main knowledge gaps

and emerging hypotheses in purine vesicle biology to highlight

their potential for cancer research.

Purinosomes play a central role in cellular

metabolism, but little is known about their regulatory mechanisms

and functional properties in the tumor context. First, whether

various tumor types exhibit distinct patterns of purinosome

assembly remains unknown. For instance, although myelocytomatosis

oncogene (MYC)-driven tumors frequently exhibit increased de

novo purine synthesis flux (86), systematic studies of assembly

principles unique to tumor subtypes are limited. Second,

purinosomes are markedly enriched in the vicinity of mitochondria;

nevertheless, the functional mechanism responsible for this spatial

coupling remains undefined. Additionally, purinosomes may receive

essential substrates from mitochondria, such as ATP, formate and

aspartate (8). Can purinosomes

specifically inhibit tumor cells by disrupting mitochondrial

colocalization, potentially developing a new therapeutic

avenue?

Furthermore, the assembly of purinosomes depends on

molecular chaperones such as HSP90/HSP70, indicating that they

constitute functional targets for chaperone inhibitors (83). However, the extent of their

dependence on the chaperone system and their specificity in tumor

cells remains to be confirmed. Finally, the morphological, dynamic

and functional traits of the purinosome closely resemble those of

liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS)-formed aggregates (82,87,88). Although LLPS is the most favored

proposed mechanism to explain its development and characteristics,

there is still limited evidence. There are likely other/further

mechanisms.

Overall, these unresolved issues constitute

important areas of research in purine metabolism. An in-depth

investigation of their mechanisms may help clarify patterns of

nucleotide metabolism in tumors and provide crucial information for

developing novel metabolic-targeted treatment approaches.

The human genome encodes two isoforms of IMPDH:

IMPDH1, located on chromosome 7, and IMPDH2, located on chromosome

3. These isoforms are essential enzymes that catalyze the

conversion of IMP to xanthosine monophosphate, regulating the

influx of guanine nucleotides. Interestingly, they are found in

nearly all organisms (100).

The assembly of intracellular IMPDH filaments forms rod-like and

ring-like structures. This process enables proliferating cells to

maintain high levels of guanine nucleotides, which are necessary

for rapid cell division. Furthermore, IMPDH is frequently

overexpressed in numerous types of tumor cells (101).

According to available data, IMPDH is highly

expressed in a variety of tumor types, with IMPDH2 expression being

particularly high. Increased IMPDH activity enhances the GMP

biosynthetic pathway, leading to markedly elevated GMP and GTP

production. This elevated nucleotide output meets tumor cell

demands for purines, energy and signaling necessary for DNA and RNA

synthesis, thereby promoting proliferation (102). For instance, increased

expression of IMPDH in colorectal cancer encourages cell

proliferation, invasion and migration. Similar results were

observed in acute myeloid leukemia, glioblastoma and small-cell

lung cancer (67,70,103,104). There is evidence that the

conversion of IMP to GMP consumes NAD+ and produces

NADH. This process is accelerated by high IMPDH expression in tumor

cells, which increases NADH synthesis and significantly lowers the

cytoplasmic NAD+/NADH ratio. This change impairs GAPDH

activity and disrupts glycolytic flux because the glycolytic enzyme

GAPDH needs NAD+ as a cofactor. As a result,

glucose-derived intermediates are redirected toward the PPP,

thereby increasing 5-phosphoribose synthesis and accelerating de

novo nucleotide synthesis in tumor cells (105,106). Furthermore, IMPDH is essential

in the tumor microenvironment. De novo purine synthesis is

inhibited when important substrates such as 5'-ribose-5-phosphate

and glucose are limited; under these conditions, increased IMPDH

expression compensates by using salvage pathway-derived IMP to

maintain GMP and GTP production (1). According to recent research,

cellular hypoxia also increases IMPDH expression, which encourages

GMP production to sustain basal proliferation in hypoxic conditions

(107). However, further

research on this mechanism is still needed.

Malignant tumors of the hematopoietic system exhibit

a high degree of dependence on IMPDH2. This dependency arises from

their high rates of proliferation, reduced ability to recycle

purines and a MYC-driven increase in purine synthesis metabolism.

For instance, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with mixed lineage

leukemia (MLL) rearrangements exhibits high sensitivity to IMPDH

inhibition, highlighting the crucial role of IMPDH2 in the

initiation and maintenance of leukemia (72). Multiple myeloma and certain acute

lymphoblastic leukemia subtypes also depend on IMPDH2 to maintain

GTP supply, thereby sustaining their proliferative capacity

(109,110). These tumors frequently struggle

to maintain nucleotide homeostasis through metabolic compensation

pathways when IMPDH is inhibited, making IMPDH inhibition a unique

metabolic vulnerability in such tumors.

By contrast, solid tumors exhibit subtype-specific

dependence on IMPDH. IMPDH2 is consistently increased in

glioblastoma and is involved in ribosome biosynthesis and DNA

damage repair. Inhibiting IMPDH2 improves the effectiveness of

radiotherapy and Temozolomide chemotherapy, indicating a distinct

metabolic therapeutic window (70). IMPDH2 is also markedly elevated

in highly proliferative solid tumors such as ovarian cancer, and is

associated with disease progression and poor prognosis. Its

suppression influences purine synthesis and may also regulate

microenvironmental processes, including inflammation and

angiogenesis (111,112). Despite having higher IMPDH2

levels, colorectal cancer is more sensitive to local

pharmacokinetic features (104). Meanwhile, IMPDH1 expression can

be increased in certain solid tumors under conditions such as

hypoxia or nutritional deprivation to maintain oxidative metabolism

and NADPH homeostasis, thereby reducing sensitivity to pure D-type

IMPDH inhibitors. This implies that combination strategies must be

considered (70).

Furthermore, IMPDH2 upregulation and elevated

nucleolar activity are observed in certain virus-associated or

immune-coupled tumors (such as Epstein-Barr virus-associated

lymphoproliferative disorders), a dependency resulting from GTP

metabolic requirements and aberrant immune regulation (108,113). IMPDH inhibition may have both

antiproliferative and immunomodulatory effects in these diseases,

providing unique therapeutic potential.

Overall, the dependencies of various tumors on IMPDH

vary widely, ranging from high-proliferation-dependent types

centered on IMPDH2 to adaptive dependency types regulated by the

microenvironment and pharmacokinetics, and finally to

metabolism-immune coupling types. These differences imply that

IMPDH-targeted therapies should be customized through specialized

investigation of tumor type, subtype characteristics, IMPDH1/2

expression patterns and metabolic compensatory capacity to improve

treatment selectivity and clinical translation potential.

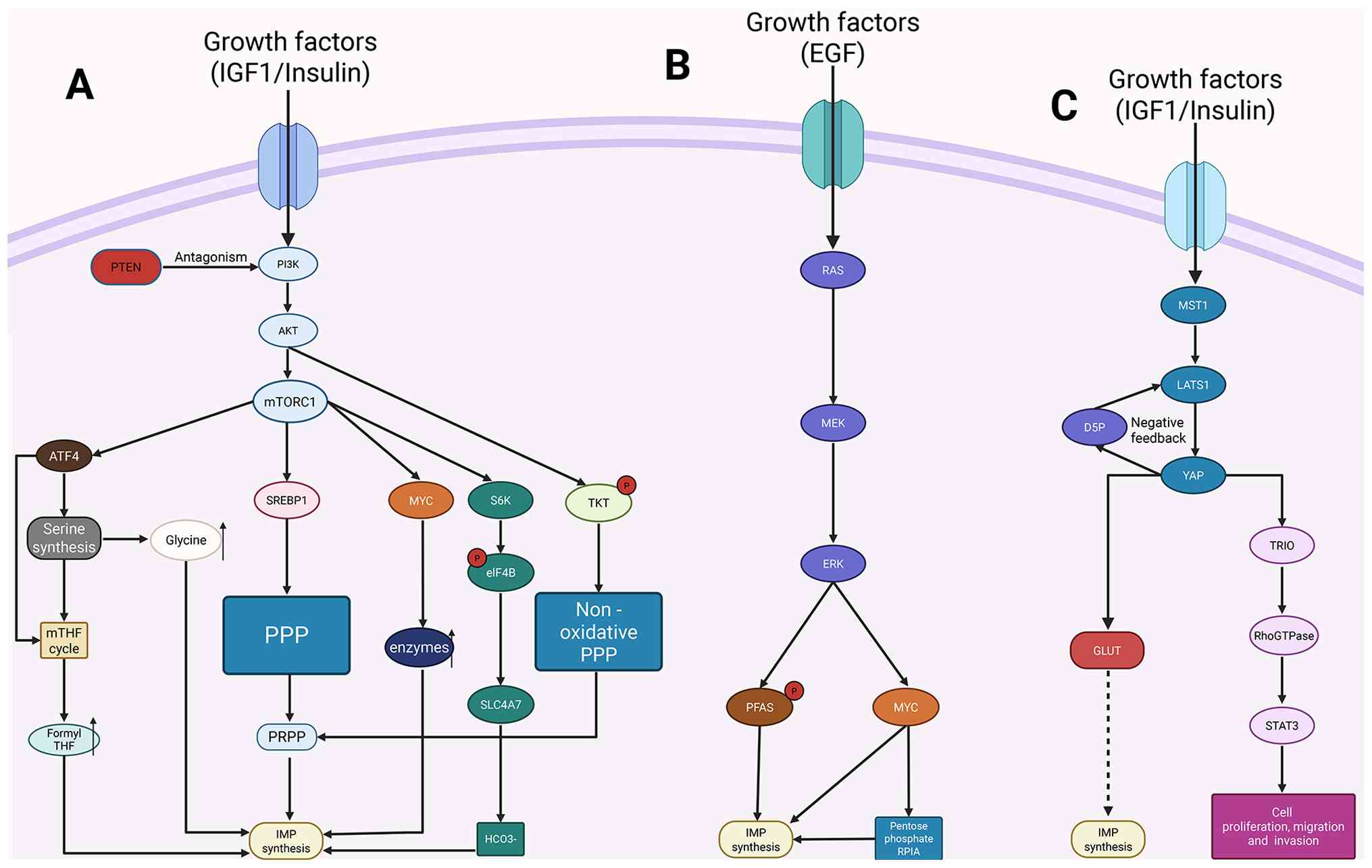

Significant progress is being made in studying the

regulation of purine synthesis through multiple signaling pathways.

Currently, the most commonly acknowledged signaling pathways

implicated in IMP synthesis are RAS-ERK, PI3K/AKT-mTORC1 and

Hippo-YAP.

Additionally, mTORC1 serves as a major hub for

signaling and metabolism and regulates the balance between anabolic

and catabolic processes in cells (114). Growth factors enhance mTORC1

signaling by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway, and establishing the

PI3K/AKT-mTORC1 signaling axis (Fig.

4A) (115). Furthermore,

mTORC1 signaling triggers the synthesis of de novo IMP

through its regulatory mechanisms by activating the transcription

factors activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and MYC (116,117). ATF4, a metabolic effector of

mTORC1, increases the synthesis of enzymes in the serine/glycine

synthesis pathway and the mitochondrial THF cycle upon induction.

These pathways respectively generate glycine and one-carbon acyl

units for de novo IMP synthesis (116). The production of activated

ribose needed for nucleotide synthesis is also increased by the

regulation of the mTORC1's oxidative branch of the PPP through the

transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1

(118). Growth signals activate

TKT through Akt signaling, which in turn activates the

non-oxidative PPP pathway to promote PRPP production (119). Notably, ATF4 increases the

expression of the cystine transporter solute carrier family 7

member 11 in its mTORC1 function, which improves cellular cystine

uptake. After being converted to cysteine, cystine acts as a direct

precursor for the synthesis of GSH, which reduces oxidative stress

in tumor cells driven by rapid nucleotide and protein synthesis

(120).

Furthermore, mTORC1 activation stimulates MYC-driven

purine biosynthesis by upregulating de novo purine synthase.

MYC plays a crucial function in regulating genes involved in

nucleotide synthesis by directly binding to the promoters of most

nucleotide metabolism genes and increasing their expression. For

instance, MYC upregulates the expression of genes such as PPAT,

carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2/aspartate

transcarbamylase/dihydroorotase and IMPDH by directly binding to

the promoters (121). MYC

increases the expression levels of IMPDH1 and IMPDH2 in both an

in vitro human B-lymphocyte model and an in vivo

mouse inducible MYC transgenic hepatocarcinoma model. MYC directly

binds to the promoter regions of these two genes, recruiting

histone acetyltransferases and chromatin remodeling complexes, such

as transketolase, to induce histone acetylation, alter chromatin

structure and initiate transcription (122,123). Furthermore, MYC regulates the

expression of GPN-loop GTPase 1 and 3, leveraging their connections

with GTP and RNA polymerase I (Pol I), while improving Pol II

assembly efficiency to fulfill global transcription demands,

thereby modulating related enzymes and ribosomal biogenesis

pathways (124). Furthermore,

growth factors (such as insulin, IGF1 and EGF) activate mTORC1 and

selectively promote mRNA translation of the bicarbonate

cotransporter solute carrier family 4 member 7 (SLC4A7) via

S6K-dependent eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B

phosphorylation, thereby increasing intracellular

HCO3− levels. Additionally, SLC4A7 deficiency

reduces HCO3− uptake and de novo IMP

synthesis in tumor cells without affecting intracellular pH.

Simultaneously, SLC4A7 deficiency increases tumor sensitivity to

the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin, demonstrating that mTORC1 regulates

HCO3− metabolism through SLC4A7 to promote

IMP synthesis and cellular growth (125).

Purinosomes assembly in tumor cells has been linked

to mTORC1, which has been demonstrated to be essential for its

localization to mitochondria. Nevertheless, the precise mechanism

by which mTORC1 regulates this process remains unclear. It will be

fascinating to investigate the possible mechanisms behind

mTOR-mediated purinosomes-mitochondrial localization and

purinosomes assembly in cancer. Additionally, the increase in

lysosomes within tumor cells is a particular response to purine

imbalance, with mTORC1 functioning as a crucial kinase that

connects purinosomes and lysosomal activity (126). Furthermore, the tumor

suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) inhibits the

activation of PI3K/AKT, and the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated in

the absence of PTEN. This then improves purine and pyrimidine de

novo synthesis pathways through mTORC1, including upregulating

IMPDH translation (127,128).

It remains elusive how mTORC1 activation integrates diverse

metabolic pathways to consistently stimulate metabolic output and

maintain cell proliferation during tumor metabolic reprogramming.

Furthermore, translational opportunities for cancer treatment are

provided by the collaborative mechanisms between mTORC1 and

signaling pathways such as RAS/ERK.

The ERK pathway regulates the extended expression of

genes involved in purine and pyrimidine synthesis by activating the

MYC transcription factor. This acts as an important mechanism for

the continuous increase in nucleotide production in cancer cells, a

process that is now commonly recognized (Fig. 4B) (129). The RAF-MEK-ERK pathway

phosphorylates downstream 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase on RAS

activation, which further stimulates the transcriptional activity

of MYC (130). MYC, the primary

regulator of nucleotide synthesis, directly binds to the promoters

of essential purine synthesis enzymes such as PPAT, PAICS and ATIC,

upregulating their expression to activate the nucleotide synthesis

pathway fully (28,131,132). Additionally,

phosphofructokinase-platelet has been demonstrated to enhance

ERK-mediated c-Myc stability (133). Furthermore, mutant K-RAS

activates MYC through ERK, which upregulates ribose-5-phosphate

isomerase-A, a crucial enzyme in the non-oxidative PPP. This

reroutes glucose intermediates into the PPP and increases PRPP

synthesis (134-137), while concurrently regulating

glutamine metabolism to supply nitrogen sources for nucleotide

synthesis, maintaining elevated intracellular nucleotide levels

(138,139). MYC contributes to tumor growth

in two ways: Promoting nucleotide synthesis and introducing a

distinct oncogenic stress through activation of RNA degradation and

nucleotide catabolism. Novel therapeutic approaches for MYC-driven

cancers can be achieved by targeting the compensatory mechanisms of

this process (140). The acute

regulation of IMP synthesis by the ERK pathway is still being

investigated. It is hypothesized that RAS-ERK may directly modulate

the activity of purine synthase enzymes such as PPAT and PAICS

because IMP synthesis is significantly higher in ERK-hyperactivated

cancers than in normal cells. This mechanism guides the development

of direct ERK-targeting drugs that support purine synthesis, even

though the specific phosphorylation sites remain unknown. It has

been revealed that ERK2 increases purine synthesis rates by

directly adding a phosphate group to threonine T619 at position 619

of phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase (PFAS), an important

enzyme in the purine synthesis pathway (141). This implies that the ERK2-PFAS

axis may be a metabolic vulnerability in RAS pathway-driven cancer

cells. Concurrently targeting the purine synthesis pathway and ERK

signaling may emerge as a novel treatment strategy for

RAS/RAF-mutated cancers.

YAP acts as a key effector in the Hippo pathway,

playing an essential role in organ size regulation and

tumorigenesis (Fig. 4C). YAP

improves glutamate ammonia ligase (GLUL) by directly binding and

transcriptionally upregulating GLUL, thereby promoting de

novo nucleotide synthesis. This provides the raw materials for

rapid cell proliferation, which promotes liver growth and

tumorigenesis (142). Yap1

stimulates de novo nucleotide synthesis by inducing glucose

transporter glucose transporter 1, thereby boosting glucose uptake

and anabolic utilization (143,144). Furthermore, YAP regulates

deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate synthesis by upregulating key

enzymes required for their production, such as ribonucleotide

reductase regulatory subunit M2 and deoxythymidine kinase (145). YAP regulates the Ras-related C3

botulinum toxin substrate 1/Ras homolog family member A switch and

STAT3 by directly activating triple functional domain protein

(TRIO), forming the YAP-TRIO-RhoGTPase-STAT3 signaling network that

controls cell migration and invasion (146). Additionally, it has been

demonstrated that YAP is regulated by cell-cell interactions and

mechanical signals in addition to serving as a crucial sensor of

the cellular metabolic state, being directly controlled by the

metabolite D-ribose-5-phosphate (D5P). Myosin heavy chain 9-large

tumor suppressor kinase 1 (LATS1) complex assembly is induced by a

decrease in intracellular D5P, which results in LATS1 degradation

and subsequent YAP activation. As a result, purine nucleoside

phosphorylase levels rise, causing purine nucleoside degradation

and establishing a negative feedback loop that elevates the D5P

concentration. This research places D5P at the center stage,

establishing it as a key metabolic node that connects glucose and

nucleotide metabolism with the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway

(147). D5P or its precursors

may serve as novel anticancer metabolites or, in conjunction with

current metabolic treatments, such as GLUT inhibitors, offer new

therapeutic approaches for cancers with high YAP activity.

In conclusion, while originating from distinct

oncogene activations, the mTORC1, ERK and YAP pathways exhibit

notable functional convergence in de novo IMP synthesis.

First, all three pathways improve the supply of carbon, nitrogen

and one-carbon units required for IMP synthesis by regulating

glucose metabolism, serine/one-carbon metabolism and glutamine use.

Second, the ERK-MYC axis and mTORC1 upregulate the expression or

activity of necessary rate-limiting enzymes (PPAT, PFAS and IMPDH),

increasing the flux of purine de novo synthesis. Third,

mTORC1 and YAP work together to increase purinosomes assembly and

mitochondrial localization, achieving spatial coupling of

nucleotide synthesis with energy/substrate supply at the

subcellular level. Additionally, the D5P-YAP feedback signal

establishes a dynamic equilibrium between purine degradation and

resynthesis, providing an adaptive mechanism for cancer cells to

maintain nucleotide homeostasis under nutritional changes.

Therefore, these three mechanisms ultimately promote rapid

proliferation, maintain RNA/DNA synthesis and guarantee GTP-driven

signaling by enhancing IMP synthesis while having differing

drivers. Accordingly, IMP/GTP metabolism appears to be a downstream

metabolic vulnerability shared by several signaling pathways.

IMP metabolism is a critical node in purine

metabolism. The downstream conversion of its metabolites, GMP/GTP,

directly or indirectly impacts T-cell activation, myeloid cell

polarization and the transmission of adenosine signaling pathways,

thereby exerting significant effects on the human immune

system.

First, T cells exhibit a marked rise in GTP demand

during activation and proliferation. GTP possesses dual roles as

both an essential metabolic substrate and signaling molecule. It

serves as a crucial substrate for RNA synthesis, supporting T-cell

clonal expansion, while also functioning as a key molecule in

receptor signaling mediated by small GTPases. GTP is involved in

vital activities, including immunological synapse formation, T-cell

receptor signal amplification, cytoskeletal remodeling and integrin

activation (148-151). Furthermore, it is the only

precursor needed to synthesize tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). BH4 is

essential for T-cell mitochondrial electron transport, ATP supply

maintenance and cell cycle progression. It affects nucleotide

synthesis, ultimately resulting in decreased T-cell proliferation

(152). Thus, a substantial GTP

pool is a metabolic requirement for T cells to progress from

initial activation to effector differentiation. T cells demonstrate

functional suppression when IMPDH is inhibited because

intracellular GTP levels significantly decrease, and T cells are

unable to maintain normal clonal expansion and effector

differentiation. These mechanisms explain why IMPDH inhibitors

cause immunosuppression in clinical settings (138) and suggest that the metabolic

imbalance of IMPs in the tumor microenvironment may weaken

antitumor immunity by limiting GTP availability, providing an

important theoretical foundation for targeting IMP metabolism to

boost immune responses (153).

Second, IMP metabolism is closely associated with

macrophage polarization. An adequate supply of purine nucleotides

significantly increases the pro-inflammatory gene expression,

migration, phagocytosis and anti-pathogen capabilities of

classically activated macrophages under inflammatory conditions,

suggesting that IMP/GMP/GTP levels are essential for M1 macrophage

function (154). Increased

purine degradation and uric acid production in the tumor

microenvironment cause macrophages to adopt an immunosuppressive

tumor-associated macrophage phenotype with high programmed cell

death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, which can be re-polarized by

inhibiting IMP metabolism (155). Furthermore, impaired purine

degradation in monocyte-derived macrophages raises isocitrate

dehydrogenase 3 activity and causes increased production of α33sdz5

d-ketoglutarate, which promotes M2-like polarization (156).

Furthermore, the body maintains equilibrium by an

intriguing cross-regulation mechanism in which high levels of AMP

and GMP block their own synthesis, while GTP stimulates AMP

synthesis. By contrast, ATP promotes the synthesis of GMP.

Accordingly, increased IMP/GMP/GTP metabolism in tumor cells leads

to enhanced IMP/AMP/ATP metabolism. Subsequently, AMP/ATP can

catalyze the production of additional adenosine using

ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase

1/ecto-5'-nucleotidase (157,158). The role of adenosine in

immunology is unmatched. It is an essential class of

immunosuppressive signaling molecules in immune regulation that

maintains immune homeostasis, limits inflammatory responses and

modulates the tumor immune microenvironment (156,159,160). Consequently, the balance of

IMP/GMP/GTP metabolism affects the operation of the adenosine

signaling pathway, eventually affecting the immune

microenvironment, including tumor cells.

In conclusion, immune system function depends on

the equilibrium of IMP/GMP/GTP metabolism. It exhibits significant

associations with T cells, macrophages, adenosine and other

components and exerts an unparalleled impact on the immune

microenvironment. Scientific investigation into the immunological

implications of this extraordinarily complex process has never

stopped.

Current IMPDH-targeting strategies in tumors

primarily take advantage of the metabolic dependence of cancer

cells on the synthesis of guanine nucleotides from scratch. These

methods disrupt DNA/RNA or GTP synthesis, causing apoptosis, by

inhibiting the rate-limiting enzyme IMPDH to prevent GMP

production.

Targeted therapies developed specifically against

IMPDH can cause the production of highly potent IMPDH inhibitors.

First, it is possible to exploit tumor cell heterogeneity, which

reflects the unique specificity of IMPDH across various tumor cell

types. For instance, IMPDH2 is markedly expressed in cells in

breast cancer and melanoma. BMS-566419 and AVN944 were designed to

target this characteristic, significantly inhibiting the growth of

tumors with high IMPDH2 expression. Recent studies have also

revealed that berberine, a natural product, inhibits the

progression of colorectal cancer by targeting IMPDH2. However, the

structural basis for IMPDH2 selective inhibition remains unclear,

necessitating further structural optimization to improve activity

(161). By contrast, IMPDH1 is

significantly elevated in high-risk groups of tumors like head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), with the purine biosynthesis

pathway being the most notably increased metabolic pathway. MPA/MMF

markedly reduced the viability of HNSCC cells, inhibited

proliferation, increased apoptosis rates, and suppressed migration

and invasion (162).

Additionally, targeted drugs that only inhibit IMPDH activity in

urothelial carcinoma associated 1 (UCA1)-overexpressing cells can

be developed to reduce toxicity to normal cells by leveraging the

IMPDH1/2-dependent regulation specificity of UCA1/twist family bHLH

transcription factor 1 in bladder cancer (163). Furthermore, a thorough

examination of the structural characteristics of IMPDH can

completely clarify its distinct role in purine synthesis, which

will help develop more specific inhibitors (100,164,165). For instance, highly specific

inhibitors targeting the cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) domain

could be developed due to the substantial homology between IMPDH1

and IMPDH2, their tetrameric structure and the presence of CBS

domains capable of binding GTP/GDP for negative feedback regulation

(166). Furthermore,

investigating associations between IMP synthesis precursors and

other metabolic pathways can lead to the identification of dual- or

multi-target inhibitors. For instance, the dual-covalent inhibitor

HA344 blocks both metabolic pathways to target and eradicate tumor

cells by covalently binding to both PKM2, the essential enzyme in

glycolysis, and IMPDH, the crucial enzyme in de novo purine

production (167). When used in

combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), it increases

immune activation because the antitumor effect of IMPDH inhibitors

balances the immunosuppressive effect of PD-L1 upregulation.

Co-administration with ICIs does not affect their antitumor

effectiveness (68).

Importantly, IMPDH inhibitors can reduce tumor cell

progression when combined with other targeted therapies. Studies

have revealed that toll-like receptor 1/2 agonists induce

differentiation in MLL-fusion AML cells, complementing the

mechanism of IMPDH inhibitors with significant synergistic effects

(72). In vitro

experiments verified synergistic inhibition of AML cell growth when

coupled with the B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor venetoclax (168). When co-administered with Ataxia

telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein inhibitors, they cause

p53-independent replication catastrophe, significantly raising

in vitro replication stress levels and markedly inhibiting

tumor growth in MKL-1 xenograft models, suggesting a potential

treatment approach for Merkel cell carcinoma (169). Even though the Food and Drug

Administration has not yet approved IMPDH inhibitors for oncology

indications, ongoing preclinical studies and exploratory clinical

trials are still being conducted to improve their therapeutic

potential (109,110,170-195) (Table II).

IMP metabolism is an essential part of tumor cell

metabolic reprogramming that plays an important role in cell

proliferation, energy balance and nucleotide supply. The metabolic

network that supplies precursors for IMP synthesis provides a

continuous material basis for tumor cell proliferation within the

framework presented in this study. Dynamic regulation of crucial

enzymes, such as PRPS, PPAT, IMPDH and purinosomes, ensures

effective de novo IMP synthesis across a variety of tumor

types. Simultaneously, signaling pathways such as RAS-ERK,

PI3K/AKT-mTORC1 and Hippo-YAP improve the adaptability of IMP

metabolism, allowing sustained tumor cell proliferation in complex

microenvironments. IMPDH inhibition reveals notable differences in

dependence across hematologic malignancies and some solid tumors,

offering potential for precision therapies. Additionally, the

interplay between IMP metabolism and the immune microenvironment

provides a theoretical framework for combined metabolic-immune

therapies.

IMP metabolism in tumor cells remains under

investigation. According to previous studies, targeting this

pathway for cancer treatment holds great potential: i) Integrating

metabolic networks based on precursor supply, such as combining IMP

metabolism with aerobic glycolysis to uncover deeper mechanisms;

ii) developing combined intervention strategies by focusing on

intersection points between IMP metabolism and signaling pathways;

iii) current IMPDH inhibitors face challenges in cancer treatment

because of high therapeutic doses, notable interindividual

differences and limited effectiveness against certain cancers. New,

highly effective IMPDH inhibitors can be developed based on

structural specificity, such as targeting the CBS domain.

Furthermore, exploring combination therapies with other drugs or

optimizing IMPDH inhibitor delivery routes is warranted; iv)

identifying IMPDH-dependent tumors using multi-omics and metabolic

imaging technologies to enable personalized treatment; v) examining

synergistic effects between IMPDH inhibition and immune modulation

to advance metabolic-immune combination treatment strategies.

Future comprehensive investigation of IMP metabolism in tumor

cellular metabolic reprogramming will contribute to building

fundamental knowledge of tumor metabolism, thereby advancing the

field of tumor treatment engineering.

Not applicable.

HZ, HW and XL wrote the original draft. XL was

involved in the conceptualization of the study. YW, DY, WZ and QT

contributed to manuscript editing. ZS and JS provided supervision

and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the

manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

No funding was received.

|

1

|

Tran DH, Kim D, Kesavan R, Brown H, Dey T,

Soflaee MH, Vu HS, Tasdogan A, Guo J, Bezwada D, et al: De novo and

salvage purine synthesis pathways across tissues and tumors. Cell.

187:3602–3618.e20. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zarrella S, Miranda MR, Covelli V, Restivo

I, Novi S, Pepe G, Tesoriere L, Rodriquez M, Bertamino A, Campiglia

P, et al: Endoplasmic reticulum stress and its role in metabolic

reprogramming of cancer. Metabolites. 15:2212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Villa E, Ali ES, Sahu U and Ben-Sahra I:

Cancer cells tune the signaling pathways to empower de novo

synthesis of nucleotides. Cancers (Basel). 11:6882019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Murray AW: The biological significance of

purine salvage. Annu Rev Biochem. 40:811–826. 1971. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pareek V, Pedley AM and Benkovic SJ: Human

de novo purine biosynthesis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 56:1–16.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Camici M, Garcia-Gil M, Pesi R, Allegrini

S and Tozzi MG: Purine-metabolising enzymes and apoptosis in

cancer. Cancers (Basel). 11:13542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

He J, Zou LN, Pareek V and Benkovic SJ:

Multienzyme interactions of the de novo purine biosynthetic protein

PAICS facilitate purinosome formation and metabolic channeling. J

Biol Chem. 298:1018532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pedley AM and Benkovic SJ: A new view into

the regulation of purine metabolism: The purinosome. Trends Biochem

Sci. 42:141–154. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lu M, Wu Y, Xia M and Zhang Y: The role of

metabolic reprogramming in liver cancer and its clinical

perspectives. Front Oncol. 14:14541612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hon KW, Zainal Abidin SA, Othman I and

Naidu R: The crosstalk between signaling pathways and cancer

metabolism in colorectal cancer. Front Pharmacol. 12:7688612021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pandey S, Singh R, Habib N, Tripathi RM,

Kushwaha R and Mahdi AA: Regulation of hypoxia dependent

reprogramming of cancer metabolism: Role of HIF-1 and its potential

therapeutic implications in leukemia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

25:1121–1134. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shi JZ, Zhu YJ, Zhang MJ, Yan Y, Zhao LL,

Zhang HD, Liu Y, Wu WH, Cheng Z, Qiu CG, et al: Hypoxanthine

promotes pulmonary vascular remodeling and adenosine deaminase is a

therapeutic target for pulmonary hypertension. JACC Basic Transl

Sci. 10:1012732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cuny GD, Suebsuwong C and Ray SS:

Inosine-5'-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) inhibitors: A patent

and scientific literature review (2002-2016). Expert Opin Ther Pat.

27:677–690. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cholewiński G, Iwaszkiewicz-Grześ D, Prejs

M, Głowacka A and Dzierzbicka K: Synthesis of the inosine

5'-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib

Med Chem. 30:550–563. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Weinhouse S: The Warburg hypothesis fifty

years later. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

87:115–126. 1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Moreno-Sánchez R, Rodríguez-Enríquez S,

Marín-Hernández A and Saavedra E: Energy metabolism in tumor cells.

FEBS J. 274:1393–418. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Moreno-Sánchez R, Rodríguez-Enríquez S,

Saavedra E, Marín-Hernández A and Gallardo-Pérez JC: The

bioenergetics of cancer: Is glycolysis the main ATP supplier in all

tumor cells? Biofactors. 35:209–225. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson

CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of

cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jing Z, Liu Q, He X, Jia Z, Xu Z, Yang B

and Liu P: NCAPD3 enhances Warburg effect through c-myc and E2F1

and promotes the occurrence and progression of colorectal cancer. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:1982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fang J, Luo S and Lu Z: HK2: Gatekeeping

microglial activity by tuning glucose metabolism and mitochondrial

functions. Mol Cell. 83:829–831. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fantin VR, St-Pierre J and Leder P:

Attenuation of LDH-A expression uncovers a link between glycolysis,

mitochondrial physiology, and tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell.

9:425–434. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH,

Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL and

Cantley LC: The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important

for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 452:230–233. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Wu N,

Asara JM and Cantley LC: Pyruvate kinase M2 is a

phosphotyrosine-binding protein. Nature. 452:181–186. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Patra KC and Hay N: The pentose phosphate

pathway and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 39:347–354. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Riganti C, Gazzano E, Polimeni M, Aldieri

E and Ghigo D: The pentose phosphate pathway: An antioxidant

defense and a crossroad in tumor cell fate. Free Radical Biol Med.

53:421–436. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

TeSlaa T, Ralser M, Fan J and Rabinowitz

JD: The pentose phosphate pathway in health and disease. Nat Metab.

5:1275–1289. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang X, Yang K, Xie Q, Wu Q, Mack SC, Shi

Y, Kim LJY, Prager BC, Flavahan WA, Liu X, et al: Purine synthesis

promotes maintenance of brain tumor initiating cells in glioma. Nat

Neurosci. 20:661–673. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Manganelli G, Masullo U, Passarelli S and

Filosa S: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency:

Disadvantages and possible benefits. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug

Targets. 13:73–82. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fan TWM, Bruntz RC, Yang Y, Song H,

Chernyavskaya Y, Deng P, Zhang Y, Shah PP, Beverly LJ, Qi Z, et al:

De novo synthesis of serine and glycine fuels purine nucleotide

biosynthesis in human lung cancer tissues. J Biol Chem.

294:13464–13477. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wu D, Zhang K, Khan FA, Pandupuspitasari

NS, Guan K, Sun F and Huang C: A comprehensive review on signaling

attributes of serine and serine metabolism in health and disease.

Int J Biol Macromol. 260:1296072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Shunxi W, Xiaoxue Y, Guanbin S, Li Y,

Junyu J and Wanqian L: Serine metabolic reprogramming in

tumorigenesis, tumor immunity, and clinical treatment. Adv Nutr.

14:1050–1066. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Geeraerts SL, Heylen E, De Keersmaecker K

and Kampen KR: The ins and outs of serine and glycine metabolism in

cancer. Nat Metab. 3:131–141. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tibbetts AS and Appling DR:

Compartmentalization of Mammalian folate-mediated one-carbon

metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 30:57–81. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Huo FC, Xie M, Zhu ZM, Zheng JN and Pei

DS: SHMT2 promotes the tumorigenesis of renal cell carcinoma by

regulating the m6A modification of PPAT. Genomics. 114:1104242022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hennequart M, Labuschagne CF, Tajan M,

Pilley SE, Cheung EC, Legrave NM, Driscoll PC and Vousden KH: The

impact of physiological metabolite levels on serine uptake,

synthesis and utilization in cancer cells. Nat Commun. 12:61762021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

DeNicola GM, Chen PH, Mullarky E, Sudderth

JA, Hu Z, Wu D, Tang H, Xie Y, Asara JM, Huffman KE, et al: NRF2

regulates serine biosynthesis in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat

Genet. 47:1475–1481. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Locasale JW, Grassian AR, Melman T,

Lyssiotis CA, Mattaini KR, Bass AJ, Heffron G, Metallo CM, Muranen

T, Sharfi H, et al: Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase diverts

glycolytic flux and contributes to oncogenesis. Nat Genet.

43:869–874. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Locasale JW: Serine, glycine and

one-carbon units: Cancer metabolism in full circle. Nat Rev Cancer.

13:572–583. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kamynina E, Lachenauer ER, DiRisio AC,

Liebenthal RP, Field MS and Stover PJ: Arsenic trioxide targets

MTHFD1 and SUMO-dependent nuclear de novo thymidylate biosynthesis.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E2319–E2326. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Jin L, Li D, Alesi GN, Fan J, Kang HB, Lu

Z, Boggon TJ, Jin P, Yi H, Wright ER, et al: Glutamate

dehydrogenase 1 signals through antioxidant glutathione peroxidase

1 to regulate redox homeostasis and tumor growth. Cancer Cell.

27:257–270. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yelamanchi SD, Jayaram S, Thomas JK,

Gundimeda S, Khan AA, Singhal A, Keshava Prasad TS, Pandey A,

Somani BL and Gowda H: A pathway map of glutamate metabolism. J

Cell Commun Signal. 10:69–75. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

43

|

Choi YK and Park KG: Targeting glutamine

metabolism for cancer treatment. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 26:19–28.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

44

|

Vanhove K, Derveaux E, Graulus GJ,

Mesotten L, Thomeer M, Noben JP, Guedens W and Adriaensens P:

Glutamine addiction and therapeutic strategies in lung cancer. Int

J Mol Sci. 20:2522019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang B, Chen Y, Bao L and Luo W: GPT2 is

induced by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-2 and promotes

glioblastoma growth. Cells. 11:25972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kim M, Gwak J, Hwang S, Yang S and Jeong

SM: Mitochondrial GPT2 plays a pivotal role in metabolic adaptation

to the perturbation of mitochondrial glutamine metabolism.

Oncogene. 38:4729–4738. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Shen Y, Huang Q, Zhang Y, Hsueh CY and

Zhou L: A novel signature derived from metabolism-related genes GPT

and SMS to predict prognosis of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer Cell Int. 22:2262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ahn CS and Metallo CM: Mitochondria as

biosynthetic factories for cancer proliferation. Cancer Metab.

3:12015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Krall AS, Xu S, Graeber TG, Braas D and

Christofk HR: Asparagine promotes cancer cell proliferation through

use as an amino acid exchange factor. Nat Commun. 7:114572016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Cai DJ, Zhang ZY, Bu Y, Li L, Deng YZ, Sun

LQ, Hu CP and Li M: Asparagine synthetase regulates lung-cancer

metastasis by stabilizing the β-catenin complex and modulating

mitochondrial response. Cell Death Dis. 13:5662022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Ma G, Zhang Z, Li P, Zhang Z, Zeng M,

Liang Z, Li D, Wang L, Chen Y, Liang Y and Niu H: Reprogramming of

glutamine metabolism and its impact on immune response in the tumor

microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 20:1142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini

KR, Yang J, Hiller K, Jewell CM, Johnson ZR, Irvine DJ, Guarente L,

et al: Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis

under hypoxia. Nature. 481:380–384. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Spinelli JB and Haigis MC: The

multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism.

Nat Cell Biol. 20:745–754. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Bertero T, Oldham WM, Grasset EM, Bourget

I, Boulter E, Pisano S, Hofman P, Bellvert F, Meneguzzi G, Bulavin

DV, et al: Tumor-stroma mechanics coordinate amino acid

availability to sustain tumor growth and malignancy. Cell Metab.

29:124–140.e10. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Sullivan LB, Gui DY, Hosios AM, Bush LN,

Freinkman E and Vander Heiden MG: Supporting aspartate biosynthesis

is an essential function of respiration in proliferating cells.

Cell. 162:552–563. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Krall AS, Mullen PJ, Surjono F, Momcilovic

M, Schmid EW, Halbrook CJ, Thambundit A, Mittelman SD, Lyssiotis

CA, Shackelford DB, et al: Asparagine couples mitochondrial

respiration to ATF4 activity and tumor growth. Cell Metab.

33:1013–1026.e6. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Newman AC and Maddocks ODK: One-carbon

metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer. 116:1499–1504. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Li T, Song LL, Zhang YW, Han YL, Zhan ZY,

Xv Z, Li Y, Tang Y, Yang Y, Wang S, et al: Molecular mechanism of

c-Myc and PRPS1/2 against thiopurine resistance in Burkitt's

lymphoma. J Cell Mol Med. 24:6704–6715. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Macmillan AC, Karki B, Yang JC, Gertz KR,

Zumwalde S, Patel JG, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Meller J and Cunningham

JT: PRPS activity tunes redox homeostasis in Myc-driven lymphoma.

Redox Biol. 84:1036492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Liu T, Wang Z, Ye L, Duan Y, Jiang H, He

H, Xiao L, Wu Q, Xia Y, Yang M, et al: Nucleus-exported CLOCK

acetylates PRPS to promote de novo nucleotide synthesis and liver

tumour growth. Nat Cell Biol. 25:273–284. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Song L, Li P, Sun H, Ding L, Wang J, Li B,

Zhou BS, Feng H and Li Y: PRPS2 mutations drive acute lymphoblastic

leukemia relapse through influencing PRPS1/2 hexamer stability.

Blood Sci. 5:39–50. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Lv Y, Wang X, Li X, Xu G, Bai Y, Wu J,

Piao Y, Shi Y, Xiang R and Wang L: Nucleotide de novo synthesis

increases breast cancer stemness and metastasis via cGMP-PKG-MAPK

signaling pathway. PLoS Biol. 18:e30008722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Goswami MT, Chen G, Chakravarthi BV, Pathi

SS, Anand SK, Carskadon SL, Giordano TJ, Chinnaiyan AM, Thomas DG,

Palanisamy N, et al: Role and regulation of coordinately expressed

de novo purine biosynthetic enzymes PPAT and PAICS in lung cancer.

Oncotarget. 6:23445–23461. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Liu B, Song M, Qin H, Zhang B, Liu Y, Sun

Y, Ma Y and Shi T: Phosphoribosyl Pyrophosphate amidotransferase

promotes the progression of thyroid cancer via regulating pyruvate

kinase M2. Onco Targets Ther. 13:7629–7639. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kitagawa Y, Kondo S, Fukuyo M, Wakae K,

Dochi H, Mizokami H, Komura S, Kobayashi E, Hirai N, Ueno T, et al:

Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate amidotransferase: Novel biomarker and

therapeutic target for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Sci.

115:3587–3595. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ding M, Ma C, Lin Y, Fang H, Xu Y, Wang S,

Chen Y, Zhou J, Gao H, Shan Y, et al: Therapeutic targeting de novo

purine biosynthesis driven by β-catenin-dependent PPAT upregulation

in hepatoblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 16:1792025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Huang F, Ni M, Chalishazar MD, Huffman KE,

Kim J, Cai L, Shi X, Cai F, Zacharias LG, Ireland AS, et al:

Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase dependence in a subset of small

cell lung cancers. Cell Metab. 28:369–382.e5. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zheng MM, Li JY, Guo HJ, Zhang J, Wang LS,

Jiang KF, Wu HH, He QJ, Ding L and Yang B: IMPDH inhibitors

upregulate PD-L1 in cancer cells without impairing immune

checkpoint inhibitor efficacy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 46:1058–1067.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Zhao JZ, Wang W, Liu T, Zhang L, Lin DZ,

Yao JY, Peng X, Jin G, Ma TT, Gao JB, et al: MYBL2 regulates de

novo purine synthesis by transcriptionally activating IMPDH1 in

hepatocellular carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer. 22:12902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Kofuji S, Hirayama A, Eberhardt AO,

Kawaguchi R, Sugiura Y, Sampetrean O, Ikeda Y, Warren M, Sakamoto

N, Kitahara S, et al: IMP dehydrogenase-2 drives aberrant nucleolar

activity and promotes tumorigenesis in glioblastoma. Nat Cell Biol.

21:1003–1014. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Liu X, Wang J, Wu LJ, Trinh B and Tsai

RYL: IMPDH inhibition decreases TERT expression and synergizes the

cytotoxic effect of chemotherapeutic agents in glioblastoma cells.

Int J Mol Sci. 25:59922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Liu X, Sato N, Yabushita T, Li J, Jia Y,

Tamura M, Asada S, Fujino T, Fukushima T, Yonezawa T, et al: IMPDH

inhibition activates TLR-VCAM1 pathway and suppresses the

development of MLL-fusion leukemia. EMBO Mol Med. 15:e156312023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

73

|

An S, Kumar R, Sheets ED and Benkovic SJ:

Reversible compartmentalization of de novo purine biosynthetic

complexes in living cells. Science. 320:103–106. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Deng Y, Gam J, French JB, Zhao H, An S and

Benkovic SJ: Mapping protein-protein proximity in the purinosome. J

Biol Chem. 287:36201–36207. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wu D, Yang S, Yuan C, Zhang K, Tan J, Guan

K, Zeng H and Huang C: Targeting purine metabolism-related enzymes

for therapeutic intervention: A review from molecular mechanism to

therapeutic breakthrough. Int J Biol Macromol. 282:1368282024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|