Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a metabolic

disorder characterized by pathological features including

triglyceride accumulation in cardiomyocytes, reduced glucose

utilization, and structural alterations such as cardiac steatosis,

myocardial fibrosis, hypertrophy and cardiomyocyte death. According

to the 2024 ESC guidelines, DCM can be diagnosed in diabetic

patients based on evidence of systolic or diastolic dysfunction,

such as ventricular hypertrophy or diffuse myocardial fibrosis,

when other cardiovascular risk factors or comorbidities are not

present. DCM encompasses a spectrum of cardiac abnormalities,

including coronary artery disease and heart failure (HF) (1). Its prevalence among diabetic

patients reaches up to 67%, and it is a recognized precursor to HF

(2).

In the diabetic heart, energy metabolism shifts

toward fatty acid oxidation (FAO) as the predominant adenosine

triphosphate (ATP) source. Despite elevated circulating free fatty

acids (FFAs), mitochondrial efficiency in ATP production is

impaired. Current therapeutic strategies remain limited, although

glycemic control is traditionally emphasized, intensive

glucose-lowering has not significantly reduced cardiovascular

mortality in clinical trials. Intriguingly, recent studies

challenge the conventional view of glucotoxicity as the initiating

factor, positioning lipotoxicity as a primordial event in DCM

pathogenesis (3). Given that

both lipids and glucose are the primary energy sources for

maintaining cardiac energy homeostasis, targeting cellular

metabolic dysregulation represents a promising therapeutic

direction.

When cellular metabolic homeostasis is disrupted,

excess fatty acids (FAs) cannot be efficiently oxidized, leading to

further lipid accumulation and the subsequent biogenesis of lipid

droplets (LDs). Typically, surplus lipids in cardiomyocytes,

macrophages, fibroblasts and neurons are stored within LDs as

neutral lipids that consist of triglycerides (TGs), cholesterol

esters (CEs), or retinol esters. Structurally, LDs are

evolutionarily conserved organelles composed of a neutral lipid

core surrounded by a phospholipid (PL) monolayer, that binds

specific proteins and cholesterol (4). The types and functions of LDs lead

to differences in their protein and lipid composition.

Nevertheless, the precise regulatory role of LD dynamics in overall

lipid metabolism remains incompletely understood.

Insulin resistance exacerbates lipolysis of adipose

tissue, leading to excessive systemic release of FAs. This elevated

FA flux promotes the expression of LD associated protein Plin5,

increases triacylglycerol (TAG) levels and enlarges LD size in

insulin-sensitive tissues such as the heart (5). Plin5 enrichment at LD-mitochondria

contact interface, implicates these inter-organellar contacts in

governing FA trafficking and cellular metabolic balance. At this

contact interface, Plin5 restricts mitochondrial respiration and

lipolysis through inhibiting adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), as

well as the decrease in lipolysis levels promotes dynamin-related

protein 1 (Drp1) to mediate mitochondrial fission (6,7).

Although insulin resistance impairs myocardial glucose uptake,

emerging evidence indicates that LDs also regulate glucose

metabolism (8). Restricting LD

accumulation has been shown to ameliorate insulin resistance

(9). Besides, LDs in

cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts confer cytoprotective effects

against lipotoxicity damage through lipase-mediated lipolysis and

autophagy-dependent lipophagy, thereby attenuating energy

metabolism dysregulation and structural cardiac damage.

Furthermore, LD biogenesis is facilitated through LD-endoplasmic

reticulum (ER) contact sites, where the conversion of

non-esterified FAs (NEFAs) into neutral lipids sequestered within

LDs serves to alleviate ER stress (10).

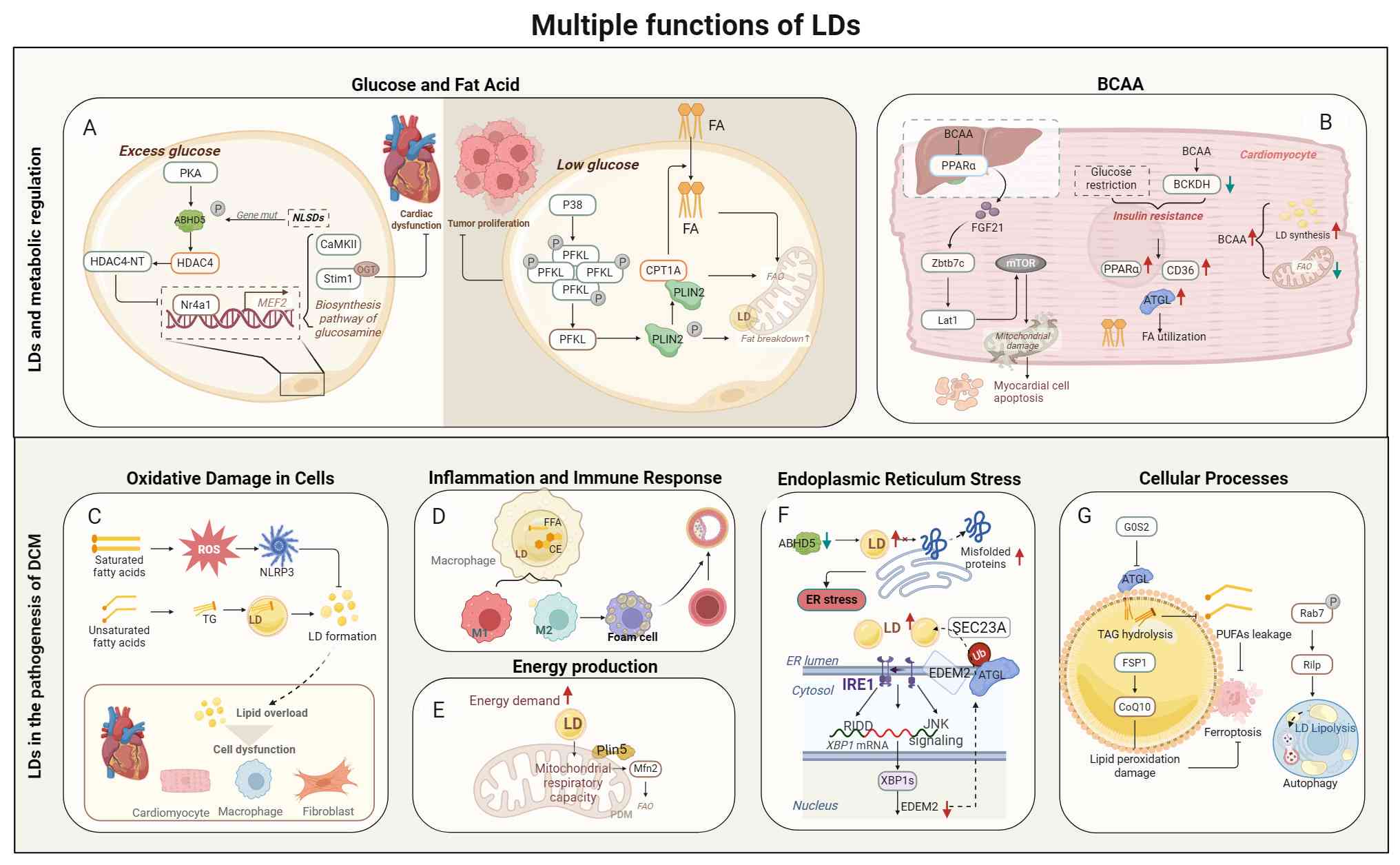

Beyond their metabolic functions, LDs serve as

multifunctional organelles that orchestrate diverse cellular

processes. LDs regulate substrate availability, mitigate oxidative

stress, modulate inflammatory responses, and function as critical

mediators in the immune signaling and cellular quality control

mechanisms, including autophagy and ferroptosis. Through these

pleiotropic roles, LDs facilitate energy production and alleviate

ER stress under physiological conditions. However, abnormal

accumulation of LDs is causally linked to mitochondrial

dysfunction, ER stress, and broader metabolic perturbations

(11,12). Collectively, these LD-associated

alterations disrupt cardiac homeostasis and contribute to

characteristic pathological features of DCM, including lipotoxic

injury, plaque formation and cardiac steatosis. Therefore, the

authors propose that LDs represent a pivotal therapeutic target for

DCM.

In the present review, LD biology was

comprehensively examined in the context of DCM, encompassing the

biogenesis of LDs, lipolytic pathways and lipophagy. It was further

analyzed how LD associated proteins modulate the processes of DCM.

Particular emphasis is placed on cell type-specific and

stage-dependent LD characteristics throughout disease progression.

Finally, existing pharmacological interventions targeting LD

dynamics and lipid metabolism were evaluated, proposing that

targeting LDs may offer a novel avenue for DCM treatment.

In cardiac tissue, the ER serves as the site of LD

biogenesis, where neutral lipid synthesis precedes their assembly

into nascent LDs (13). The ER

harbors essential enzymes responsible for synthesizing the two

major neutral lipid species: Acyl-CoA: cholesterol

O-acyltransferases 1 (ACAT1, as ACAT2 is not expressed in the

heart) primarily catalyzes CEs (14), and TAGs, synthesized by

diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) 1 and DGAT2 (15). Whereby deficiency in specific

lipid synthesis enzymes can be compensated by alternative pathways

to maintain neutral lipid production and LD formation (16). DGAT1 localizes exclusively to the

ER membrane, whereas DGAT2 displays dynamic subcellular

distribution, localizing to ER membrane and LD interface. When

intracellular FA concentrations increase, DGAT2 translocates to the

LD surface, thereby facilitating TAG storage and LD expansion

(15).

Beyond the canonical DGAT-mediated pathway,

alternative mechanisms contribute to TAG synthesis, including

transmembrane thioredoxin 1, which catalyzes storage lipid

production independently of DGAT1/2, though the mechanism requires

further investigation (17). LD

nucleation occurs when TAG and CEs accumulate to concentrations of

5-10 mmol/l within the ER bilayer, forming lipid lenses that

coalesce under the action of PL acid and diacylglycerol (DAG)

(4,18-20). The subsequent LD budding is

orchestrated by ER-intra TAG concentration and the scaffolding

protein Seipin which localizes to nascent lipid lenses to drive LD

growth and facilitate the detachment of the PL monolayer-enveloped

LD through ER-to-cytoplasm (21). LD budding directionality and size

are determined by the asymmetric distribution of the PL monolayer

cap, which is governed by ER membrane asymmetry, lipid composition

and the spatial positioning of budding site (22,23). Perturbations in neutral lipids

trafficking to the ER membrane or aberrant retention on the

cytoplasmic leaflet impair the clearance of misfolded proteins,

thereby triggering ER stress and inflammatory responses that

necessitate continuous PL supplementation to sustain budding

(24). Notably, a fundamental

distinction exists between mammalian and yeast LD biology; whereas

mammalian LDs exist as independent cytoplasmic organelles, yeast

LDs maintain persistent ER membrane continuity. This evolutionary

divergence reflects species-specific adaptations in lipid storage

compartmentalization and ER-LD membrane dynamics (25,26).

To meet cardiac energy demands, stored LDs undergo

catabolism through lipolysis and lipohagy, processes that hydrolyze

TAG into FA for subsequent oxidation. Lipolysis proceeds through a

sequential three-step enzymatic cascade: (i) ATGL mediates

rate-limiting TAG hydrolysis at the sn-2 position, generating DAG

and FAs. (ii) Hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) subsequently cleaves

DAG into FAs and monoacylglycerol (MAG). (iii) MAG lipase (MGL)

completes the process by liberating the final FAs and MAG (27,28). The specificity and efficiency of

ATGL-mediated lipolysis are enhanced by its cofactor comparative

gene identification 58/Alpha beta hydrolase domain-containing

protein 5, which redirects ATGL activity toward the sn-1 position

and cooperates with DGAT2 to generate SN1,3DAG. SN1,3DAG is a

stereoisomer that bypasses protein kinase C activation but serves

as the optimal HSL substrate for continued lipolytic flux (27,28). CGI 58 inhibited the lipolysis

rate after interacting with Plin1, and the inhibitory effect

disappeared after PKA phosphorylation of Plin1 (29,30). Similarly, Plin5 phosphorylation

orchestrates a functional switch from a lipolysis barrier to a

promoter of TAG breakdown, as phosphorylated PLIN5 recruits both

CGI 58 and ATGL, facilitating the coordinated hydrolysis of TAG

into glycerol and Fas (31,32). This phosphorylation-dependent

regulation of perilipin-lipase interactions represents a critical

control node integrating hormonal signals with cellular energy

status to modulate cardiac lipid catabolism.

LDs are partially or completely decomposed into

glycerol and FAs in a process known as lipophagy. Lipophagy mainly

degrades neutral lipids such as TAGs and CEs through three

autophagy modes, including molecular chaperon-mediated autophagy

(CMA), macro-autophagy and micro-autophagy, each characterized by

specific molecular mechanisms. In CMA, the 71 kDa heat shock

cognate protein (HSC70) proteins directly recognizes Plin2, Plin3

and Plin5 via the five-peptide motif protein KFERQ like

pentapeptide motifs, facilitating their selective degradation, and

subsequently eliminating their protective shielding of ATGL at the

LD surface (33). Following

HSC70-mediated recognition, the KFERQ-bearing perilipins binds to

lysosome-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP2A), assembling into a

translocation complex that delivers these cargo proteins into the

lysosomal lumen for degradation. The CMA-mediated removal of Plin2

and Plin3 consequently enables ATGL accessibility to LDs, thereby

promoting both ATGL-mediated lipolysis and subsequent lipophagy

(34). During macro-autophagy,

LDs recruit autophagy related proteins to initiate the biogenesis

of autophagosomes, facilitating the selective sequestration and

lysosomal degradation of lipid cargo (35). Micro-autophagy mediates direct LD

engulfment by lysosomes through membrane contact site tethering

mechanisms, wherein LD contents are transferred to the lysosomal

lumen via direct injection or membrane transfer remains unclear,

potentially regulated by membrane fusion associated small GTPases,

and hydrolyzed by lysosomal acid lipase independent of cytoplasmic

lipases and autophagy (36).

It should be noted that the degradation of LD

through lipolysis or lipohagy is determined by the size of the LD.

Lipohagy can only degrade smaller LDs in liver, while LDs exceeding

the degradation capacity of lipohagy will trigger ATGL-mediated

cytoplasmic neutral lipolysis under normal conditions, with

starvation or cellular stress inducing acid lipolysis to release

FAs for FAO. Thus, the liberation of lipids and TGs from LDs for

energy production is facilitated by neutral and acidic lipolysis

(37). Whether similar

size-dependent and pathway-selective mechanisms operate across DCM

warrants further investigation (Fig.

1).

The dynamic stability and regulatory function of LDs

are significantly reliant on surface-binding proteins. The

categorization of these LD-associated proteins remains

insufficient: One perspective separates them according to the

mechanism of metastasis. Class I proteins such as DGAT2, ACSL3 and

GPAT4 are translocated from the ER to LDs through the ERTOLD and

include hydrophobic hairpin motifs that directly engage with LDs

(38).

The CYTOLD pathway mediates the direct transport of

Class II proteins from the cytosol to LDs. These proteins include

Plins, members of the Perilipin family that possess an amphipathic

helix, as well as cell death-inducing DNA Fragmentation Factor

Alpha (DFFA)-like effector (CIDE) family of proteins. Conversely,

CGI58, which is associated with LDs via protein-protein

interactions, engages with proteins, including histones and the

small GTPase Rab18 (RAB18), which is anchored to LDs through lipid

modification (39,40).

Based on their roles, these proteins can be

categorized into LD structural proteins/resident proteins, lipid

metabolism enzymes, and transport/signal transduction proteins.

Such proteins are produced through fusion or localized lipid

synthesis.

DGAT2: LD biogenesis involves functional coupling of

FA transporter protein 1 on the ER membrane and DGAT2 at nascent LD

surfaces, which coordinately promote TAG synthesis and lipid

transfer (41). However, DGAT2

expression must be tightly controlled, as overexpression

compromises ER membrane stability (42). Post-translational modification

provides additional regulation, H2S intervention

enhances ubiquitin-mediated degradation of DGAT1 and DGAT2 and

enhanced the expression of the E3 ligase Hrd1 to reduce LDs

accumulation (43). The small

GTPase RAB1B dynamically regulates DGAT2 subcellular distribution

by facilitating its trafficking from ER to LDs via secretory

pathways, promoting the expansion and growth of LDs (44). Collectively, these mechanisms

encompassing protein interactions, expression control, proteolytic

regulation and vesicular trafficking converge to fine-tune LD

dynamics in response to metabolic demands.

The perilipin family represents the major

LD-resident proteins in mammalian cells. In cardiac tissue, PLIN2

and PLIN5 predominate; whereas Plin1 is mainly located in

adipocytes, Plin5 facilitates TAG storage. During the metabolic

transition from glycolysis to β-oxidation, Plin2 upregulation

activates the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs)

signaling pathway (45,46). Plin2 regulates the shape, size

and morphology of LDs, while both Plin2 and Plin5 inhibit ATGL

mediated lipolysis, thereby modulating lipid accumulation (47,48).

ABHD5/CGI 58: CGI 58, a highly conserved regulator,

is characterized by its interaction with Plin and ATGL to function

as a coactivator in ATGL-mediated lipolysis (52). PKA-mediated phosphorylation of

Plin5 in the heart enhances the expression of CGI 58. By contrast,

non-phosphorylated Plin5 binds CGI 58 and inhibits lipase activity.

Beyond Plin regulation, cellular homeostasis also requires

coordinated action of other key metabolic enzymes. Lipolysis is

primarily mediated by three enzymes: ATGL, HSL and MGL.

Upregulation of these key lipolysis enzymes ameliorate cardiac

steatosis and myocardial fibrosis (53). Decreased expression of lipolysis

enzymes aggravates mitochondrial dysfunction (54).

ATGL acts as the rate-limiting enzyme for TAG

hydrolysis in LDs, ATGL deficiency reduces PPARα expression and FAO

levels, resulting in human neutral lipid storage disorder and

cardiomyopathy (55).

Restricting lipid absorption alone fails to reverse ATGL deficiency

induced cardiomyotoxicity (56).

Yet ATGL overexpression ameliorates myocardial injury by enhancing

lipolysis (55). This indicates

that ATGL deficiency extends beyond mere lipid accumulation, as its

mediated lipolysis liberates PPAR agonists that activate downstream

PPARα/PGC-1α-regulated FAO and mitochondrial biogenesis (57). Although pharmacological

interventions partially restore FAO, the signaling function of ATGL

remains indispensable for cardiac protection.

HSL: Overexpression of Plin2 markedly reduces HSL

expression, indicating that Plin2 as a functional inhibitor of HSL

(53). HSL exerts a

cardioprotective effect that precedes the overt development of

cardiac lipotoxicity. In the context of DCM, overexpression of HSL

does not influence VLDL absorption but effectively downregulates

key profibrotic factors, including collagen, TGF-β and matrix

metalloproteinase (MMP) 2. This suppression alleviates the

lipotoxicity and LDs accumulation driven by TAG and DAG (58).

LDs sequester excess histones, preventing histone

toxicity, and supplies histones for chromatin assembly during DNA

replication (59,60). Multiple proteins govern stability

of LDs while concurrently engaging in membrane transport and signal

transduction, thereby influencing cellular metabolic remodeling

(61). Proteins of the LD

proteome related to LD biogenesis in DCM are included in Table I.

LDs establish contact sites with multiple

organelles, most notably mitochondria; the adult heart derives ~95%

of its ATP from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, with FAO

contributing 40-60% of reduction equivalents. Mitochondrial

dysfunction generates lipotoxicity intermediates that promote

intracellular lipid accumulation. LDs counteract lipotoxicity by

sequestering excessive FAs and lipid intermediates. During energy

stress such as fasting or β-adrenergic stimulation, increased

cardiac energy demand and elevated adipocyte lipolysis lead to

heightened expression of LDs, Plin5, and mitochondrial LDs contact

sites in cardiac tissue. This metabolic demand promotes formation

of 'peridroplet mitochondria (PDM)', a specialized mitochondrial

subpopulation with unique functional, ridge-structured, and

proteomically distinct mitochondrial compartment attached to LDs

(5,69). Plin5 mediates these

LD-mitochondria contacts (LDMCs) and preferentially targets PDMs

(5). In cardiomyocytes, enhanced

Plin5-dependent LDMC improve mitochondrial respiratory capacity and

metabolic flexibility. Paradoxically, FAO remains independent of

LDMC (70). This may relate to

PDM primarily promoting FA activation and TAG synthesis with

stronger oxidative phosphorylation and ATP supply capacity, which

are not mainly responsible for FAO (71).

Previous studies have revealed a link between LDs

and mitophagy. Mitophagy leads lysosomes to phagocytose PDM and

release FAs, which aggravates intracellular lipid peroxidation and

iron accumulation and eventually cause ferroptosis. Inhibiting

mitophagy significantly reduces LD accumulation and FFA levels, yet

DGAT1 expression remains elevated and continues to drive nascent

LDs formation (72).

PLIN2 regulates LD homeostasis and mitochondrial

remodeling through epigenetic mechanisms. By suppressing lipolysis,

Plin2 elevates acetyl-CoA and histone acetylation levels,

maintaining embryonic stem cell pluripotency (73). Loss of Plin2 shifts cellular

metabolism from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation and

accelerates pluripotency exit. Under these conditions, Plin2 is

recognized by Hsc70 and degraded through CMA, promoting

mobilization of LDs (74). This

is similar to the metabolic transition of cardiomyocytes from

embryonic to adult stages. Although short-term glucose deprivation

alters Plin2 conformation, weakening its interaction with ATGL and

enhancing lipolysis, though the impact on cardiac metabolism

remains uncertain (75).

In fact, the link between LDs and mitochondria is

largely established by specific molecules or pathways that serve

multiple functions in both LD dynamics and mitochondrial operation.

Under nutrient excess conditions, mitophagy becomes dysregulated

and AMPK activity declines (76). Only part of AMPK-mediated

phosphorylation of ACC1 and ACC2 fails to effectively inhibit FA

synthesis, paradoxically promoting LD formation. AMPK activates

PPARs γ coactivator 1 alpha (PGC1α) is blocked, disrupting the

formation of complexes between PGC-1α, Plin5 and silent information

regulator 1 (SIRT1), and impairing mitochondrial biosynthesis

(77).

Concurrently, excessive mammalian target of

rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling stimulates lipid

accumulation by activating its key downstream effector sterol

regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c). Autophagy is

inhibited by Akt-mediated suppression of FOXO transcription and

further impaired by elevated branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs),

which suppress the mTORC1/autophagy-related protein (ATG)/ULK

pathway (78,79). SIRT1 mediated deacetylation

activates FOXO1, whose deacetylation status regulates the

expression of ATGL and PPARα (80).

Under energy-deficient conditions, FOXO1 also

recruits Rab7 to sustain autophagy, a process involved in the

micro-lipophagy degradation of LDs. In DCM, the inhibitory effect

of FOXO on transcription factor EB (TFEB) is weakened (81). It is worth noting that PKA

promotes lipolysis mediated by Plin5, CGI58 and ATGL (8). Therefore, LD metabolism is

coordinately regulated by upstream kinases, for instance, PKA,

mTOR, as well as AMPK and transcription factors including silent

information regulator 1 (SIRT1), PGC-1α, FOXO, SREBP1, PPARs and

TFEB (31).

LDs represent the principal cellular compartment

specialized for neutral lipid storage, distinguished from other

organelles by both structural architecture and functional capacity.

The ER despite serving as the site of lipid biosynthesis,

incorporates lipids within its PL bilayer rather than sequestering

them in concentrated deposits, limiting its storage capacity and

potentially compromising membrane function under lipid excess

(4). Mitochondria maintain

membrane lipids essential for bioenergetics but actively oxidize

rather than store FAs, making them vulnerable to lipotoxic damage

when substrate availability exceeds oxidative capacity. Peroxisomes

metabolize very-long-chain and BCAAs through β-oxidation yet lack

mechanisms for TAG or CEs accumulation (72). Lysosomes degrade lipids delivered

via endocytosis or autophagy but function as catabolic rather than

storage compartments.

By contrast, LDs possess a unique PL monolayer

encompassing a hydrophobic neutral lipid core, an architecture that

enables massive expansion without membrane stress or dysfunction of

organelles (4). This specialized

structure allows LDs to accumulate energy-dense TAGs and CEs while

protecting other organelles from lipotoxic intermediates. The

dynamic nature of LD expansion, lipophagy and lipolysis regulate

lipid mobilization coordinated with metabolic demands, whereas

lipid accumulation in other organelles typically signals

pathological dysfunction rather than adaptive storage.

Consequently, LDs serve as the primary defense against abnormal

lipid deposition, protecting mitochondria, ER, and plasma membrane

integrity from lipotoxicity-induced cellular damage.

Beyond their canonical storage function, LDs protect

cells from lipotoxicity by limiting lipid peroxidation and

buffering excess FAs during metabolic dysregulation. LDs regulate

diverse metabolic substrates, including BCAAs and glucose, both

central to DCM pathogenesis. LDs participate in intermembrane lipid

trafficking, store precursor molecules for lipids, mitigate

oxidative damage, and modulate inflammatory responses. By

coordinating these diverse functions, LDs protect mitochondria and

other organelles while regulating cellular processes such as

autophagy, ferroptosis, and cell division (11,12).

Hyperglycemia induces cardiac lipid overload and

metabolic dysregulation, with insulin resistance exacerbating

lipotoxic injury to cardiomyocytes, disrupts metabolic homeostasis,

manifesting as mitochondrial dysfunction, ER stress and calcium

overload. LDs likely play multiple roles in modulating these

pathological responses through their capacity to store and mobilize

lipids. Under conditions of sustained hyperglycemia, excessive FA

influx overwhelms oxidative capacity, triggering abnormal lipid

accumulation that compromises cellular homeostasis. Insulin

resistance further impairs metabolic flexibility, preventing

adaptive substrate switching and intensifying reliance on FAO

despite limited mitochondrial capacity (82). The resultant accumulation of

lipotoxic intermediates, including DAG, ceramides and

acyl-carnitines, directly impairs mitochondrial respiration, induce

calcium dysregulation and ER stress.

LDs limit FAs' incorporation into membrane PLs and

reducing susceptibility to peroxidative damage. This antioxidant

function preserves organellar integrity and prevents ferroptosis

driven by lipid peroxidation (72). Conversely, LDs mobilize stored

lipids through two pathways: Neutral lipase-mediated lipolysis and

autophagy-dependent acid lipolysis. Lipolysis liberates FAs for FAO

during energy demand. Insulin resistance impairs autophagy, a

mechanism essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Lipophagy, representing a cargo-selective autophagy pathway,

specifically targets LDs for lysosomal degradation. Current

evidence indicates that both CMA and micro-autophagy contribute to

metabolic regulation in DCM, although the role of macro-autophagy

remains controversial (81). The

proteins and PLs on the surface of LDs interact with specific

enzymes to exert important functions. The balance between LD

storage and degradation thus determines lipid flux, organelle

function, and influence cellular metabolic homeostasis in DCM.

Cardiomyocytes mainly rely on oxidative

phosphorylation for energy supply and can also generate energy

through glycolysis and other ways. Nowadays, the change of FAO in

DCM remains controversial (83).

It may be related to the stage of DCM. A multimeric complex

consisting of extended synaptotagmin 1 (ESYT1), ESYT2, VAMP

Associated Protein B and C localizes to ER-LD-mitochondria contact

sites. Loss of this complex reduces LD-derived FAO by 67% and

promotes LDs accumulation, indicating that the complex facilitates

lipid mobilization and prevents lipotoxicity (84,85). This reduced oxidation capacity

appears paradoxical given previous studies of elevated FAO in DCM,

suggesting compensatory mechanisms may operate under different

metabolic conditions (57).

These findings demonstrate that LD accumulation and the resulting

imbalance in FAO are important pathogenic mechanisms in DCM.

Normally, acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family

member 1 activates FAs to fatty acyl-CoA for subsequent

β-oxidation, which directly generates acetyl-CoA for the TCA cycle.

Long-chain FAs require CPT1/2-mediated mitochondrial transport

before oxidation (88). In DCM,

long term overload of FAO promotes electron leakage, generating

reactive oxygen species (ROS) and aggravates oxidative stress.

Plin5 suppresses the ROS-activated Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

(PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway and the mitogen-activated

protein kinase pathway (p38/ERK/JNK), hence preventing oxidative

stress and apoptosis (89,90).

LDs protect against ferroptosis through antioxidant

mechanisms. FSP1, located in LDs, and maintains antioxidant

capacity by reducing Coenzyme Q10, preventing peroxidation of

neutral lipids. Impairment of FSP1 function induces the

peroxidation of polyunsaturated FA-LDs (PUFA-LDs), triggering

ferroptosis of cardiomyocytes (91). In type 1 diabetic patients,

glucolipotoxicity reduces LAMP2A, Hsc70 and Hsc90 expression,

inhibits the clearance of autophagosomes and inactivates TFEB,

causing autophagy disorders and rendering the myocardium vulnerable

to ER stress and metabolic injury (92).

Cardiomyocytes maintain lipid homeostasis by

balancing the FAO rate with LD biosynthesis. Under nutrient excess,

insulin activates acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) to generate

malonyl-CoA, which inhibits the acetylation level of CPT1 and MPC2,

thereby restricting FAO (93,94). Studies in CPT1b-deficient

skeletal muscle confirm that reducing FAO alleviates mitochondrial

lipid burden during energy surplus (95). Conversely, ACC2 knockdown

maintains FAO and reduced cardiac hypertrophy, demonstrating that

preserving oxidative capacity protects cardiac function (96).

DGAT1 and GPAT4 are upregulated to enhance TAG

synthesis, and the elevation of TAG levels is positively correlated

with systolic dysfunction, suggesting that excessive accumulation

of LDs adversely affects cardiac structure (97).

Downregulated TGR5 fails to inhibit DHHC4, which

mediates the palmitoylation of CD36, consequently promoting CD36

overexpression, the abnormal FAO, and the elevated LDs'

accumulation (98,99). Exceeding the LDs' buffering

capacity results in surplus FAs, leading to cellular lipotoxicity

and disruption of energy supply. Concurrently, the inhibitory

effect of ATGL on ceramide will be weakened, resulting in increased

ROS production and triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately

inducing apoptosis and aggravating insulin resistance (100,101) (Figs. 2 and 3).

Macrophages primarily orchestrate inflammatory and

immunological responses to sustain cellular metabolic homeostasis.

While numerous studies have researched lipotoxicity in

cardiomyocytes, studies on lipotoxicity in macrophages remain

insufficient. Macrophages modulate their energy acquisition through

dynamic remodeling of membrane receptors coupled with metabolic

reprogramming of glucose and lipid pathways. These cells meet their

lipid requirements by engulfing apoptotic cells, lipoprotein

particles and LDs.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is oxidized to OxLDL,

which macrophages internalize via CD36-mediated endocytosis.

Lysosomal hydrolysis releases FFAs and TC which are stored in LDs

as CE. Reduced lipid autophagy and cholesterol efflux further lead

to LDs accumulation, ultimately impairing phagocytic capacity and

transforming into foam cells (102).

Macrophages form LDs under conditions of

inflammation and oxidative stress. With different phenotypic

switches, the expression levels of LD-related proteins are also

different. Plin1 and Plin2 regulate both polarization of

macrophages and LD size. Plin1 was found to promote larger LDs when

overexpressed in M1 macrophages. With Plin1 overexpression

promoting larger LDs in M1 macrophages, Plin1 associates with the

inflammatory phenotype whereas Plin2 correlates with the

anti-inflammatory phenotype and collectively governing lipid

storage (103). Current

investigations of LD biology in macrophage subtypes remain confined

to classic M1 macrophages and M2 macrophages despite the

identification of diverse macrophage phenotypes. Nevertheless, LDs

serve critical functions in maintaining cellular homeostasis and

macrophage function, processes fundamentally linked to

atherosclerosis (104).

Advanced glycation end products in the diabetic

cardiac microenvironment promote M1 macrophage polarization through

the miR-471-3p/SIRT1 pathway. M1 macrophages enhance glycolysis

while suppressing FAO, thereby activating the pentose phosphate

pathway to generate pro-inflammatory and bactericidal mediators

(105). M2 macrophages, by

contrast, exhibit greater LD accumulation and elevated FAO levels,

maintaining their anti-inflammatory phenotype through PPARγ

(101). TGF-β promotes LDs

synthesis via the ERK1/2 pathway and attenuates STAT1 to inhibit M1

polarization (106). Activation

of the PPAR pathway upregulates CD36 and Plin2, thereby promoting

LD formation, and influences immunophenotypic switching (107,108). CX3CR1 signaling appears to

inhibit M1 polarization while promoting foam cell formation

(109). The expanding lipid

core subsequently elevates the levels of MMP, nitric oxide and

endothelin, and eventually causes plaque rupture (110).

Macrophage-derived LD-associated hydrolase

upregulates Abca1 and Abcg1 expression through an LXR dependent

mechanism, thereby attenuating the inflammatory response induced by

SE accumulation (111).

Although conventional perspective considers that accumulation of

LDs fosters insulin resistance or inflammation, protective

regulatory mechanisms exist. Forkhead box protein C2 (foxc2)

suppresses the angiopoietin-like 2 (angptl2)/NOD-like receptor

thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome

pathway, reducing the expression of NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1. Foxc2

also modulates Bcl-2/Bax to diminish apoptosis, oxidative stress

and LDs' accumulation in macrophages (112,113).

Foam cell formation is regulated by lipophagy

factors including HSPA5, UBE2G2 and AUP1. Upon autophagy

activation, LDs initiate lipophagy by recruiting LC3 and adaptor

protein Sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1). Sirt6-dependent chromatin

remodeling factor SNF2H inhibits Wnt family member 1/β-catenin

pathway to accelerate lipophagy and autophagosome lysosome mediated

lipolysis and accelerating autophagosome-lysosome-mediated

lipolysis and FA transfer to mitochondria for FAO. A key unresolved

question concerns the specific mechanism through which sirtuin6

regulates this transfer (114).

In vascular smooth muscle cells, Plin2 similarly facilitates

lipophagy through elevated LC3II levels and enhanced autophagosomes

biogenesis, which impedes foam cell formation (115). Targeting lipophagy may

represent a promising strategy for stabilizing vulnerable plaques

(Fig. 4).

Cardiac fibroblasts exhibit region-specific

distribution patterns and undergo distinct phenotypic transitions

during pathological remodeling. Following acute myocardial

infarction (MI) and HF, F9 (FAP/POSTN+) fibroblasts

differentiate into the POSTN lineage through PI3K-Akt and AGE-RAGE

signaling rather than adopting an ACTA2+ myofibroblasts

phenotype (116). The

transition of CD34+ cells to FABP4+

fibroblasts represents a critical fibrotic process, enhancing lipid

storage via the PPARγ/Akt/Gsk3β pathway activation (117). Therapeutically targeting the

NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin/GSK3β pathways may mitigate pathological

cardiac remodeling, including cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis

(118), underscoring how

inflammatory signals govern fibroblast activation and

differentiation. Lipotoxic intermediates, for instance, long-chain

acyl-CoA, ceramide, acylcarnitine and DAG, can directly induce

myocardial fibrosis (119).

Hypoxia and cellular stress stimulate intracellular LD accumulation

in fibroblasts. During early stage of myocardial fibrosis, cardiac

fibroblasts proliferate excessively and excessive secretion of

α-smooth muscle actin and alongside extracellular matrix (ECM)

proteins generated in large quantities (116).

Fibroblasts-derived kinesin-like protein 23 (Kif23)

activates the Ras homolog family member a pathway to enhance

proliferation while suppressing LD hydrolase carboxylesterase 1d

through ROCK1, thereby impairing FAO and promoting lipid

accumulation in fibroblasts, and facilitating myofibroblast

transformation (120). Thus,

targeting Kif23 may represent a new direction for attenuating

myocardial fibrosis. Nevertheless, additional investigation is

required to define how LDs in fibroblasts contribute to myocardial

fibrosis. Fully exploring the effects of cellular stress,

inflammation, and LD accumulation on cardiac lipotoxicity

represents a novel target for fibroblasts in DCM.

Elevated glucose levels promote the production of

LDs, while excessive glucose and FFAs can damage peripheral

neurons, disrupting the sympathetic nervous system's control over

the heart (121). The

conventional viewpoint points out that lipotoxicity is considered a

key driver of metabolic heart disease. Nevertheless, certain

investigations indicate that cardiac dysfunction in neutral lipid

storage disorders resulting from genetic mutations in CGI58 and

ATGL is predominantly influenced by CGI58 rather than ATGL. This

indicates that LDs may have a possible correlation with glucose

metabolism. CGI58, serving as a serine protease, responds to

phosphorylation by PKA and subsequently cleaves the epigenetic

regulator histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4), producing the N-terminal

polypeptide of HDAC4 (HDAC4-NT), HDAC4-NT transcriptionally repress

Nr4a1 expression, which interacts with myocyte enhancer factor 2

(MEF2). Nr4a1 prevents CaMKII from driving HDAC4 to activate MEF2.

This blocks MEF2 from subsequently activating the hexosamine

biosynthesis pathway, a metabolism linked to protein

O-GlcNAcylation. Consequently, the calcium-handling protein Stim1

avoids undergoing O-GlcNAcylation, thereby protecting cardiac

function (8,31,57,122). ATGL is blocked by Plin5;

however, the ablation of Plin5 does not affect gene expression

involved in glucose metabolism, FAO, along with glycogen metabolism

(123).

Glucose deprivation activates P38 to phosphorylate

glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase, liver type (PFKL) at Thr331,

converting it from a tetramer to a monomer. PFKL then acts as a

protein kinase, phosphorylating Plin2 to enhance its interaction

with CPT1A, therefore facilitating FA transfer, FAO and lipolysis.

PFKL, which inhibits glycolysis during low glucose availability, is

posited to promote the anchoring of PLIN2 to LDs' phosphorylation

and mitochondria to modulate lipolysis. This direct transfer of FAs

from glucose to LDs may prevent lipid accumulation and mitigate

cellular lipotoxic damage (75).

Clinical studies report elevated plasma

concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) in patients

with DCM. Animal experiments show that inhibiting FGF21 reduces

PGC1α expression and upregulates CD36, leading to LD accumulation

and cardiac dysfunction. PGC1α is a downstream factor of FGF21,

effectively reduces blood glucose as well as lipid levels while

enhancing insulin sensitivity. Under dual intervention of knocking

down FGF21 and fasting, glucose production and ketone body

synthesis are damaged, suggesting that FGF21 holds promise as a

potent therapeutic target for DCM management (124,125). Alterations in BCAA and FGF21

signaling establish metabolic links between the heart and the

liver.

BCAAs inhibit the PPARα-FGF21 axis in the liver and

reduce FGF21 secretion in the liver, thereby upregulating the

content of BCAA in the heart and the expression levels of

zinc-finger and BTB domain-containing 7B and Lat1, activating mTOR

signaling and inducing mitochondrial damage and cardiomyocyte

apoptosis, ultimately accelerating myocardial fibrosis in mice with

type 1 diabetes (126).

Knockout of PPARα in mice induced a metabolic shift towards

glycolysis, HIF1α, as well as augmented glucose metabolism

alongside ECM remodeling, finally decreasing FAO (127). PGC1α is also involved in

regulating the rate of glycolysis BRM-associated factor 60c

facilitates the transition of oxidative muscle fibers to glycolytic

muscle fibers via the PGC1α-PPARα-mTOR pathway, thereby preserving

oxidative metabolism/glycolysis balance and enhancing mitochondrial

function in rats with HF (128). The metabolic disorder of BCAA

in cardiomyocytes results into an abnormal rise in the biosynthesis

of LD as well as a reduction in FAO rate, which coincides with

suppression of branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH)

located in the ER and the excessive expression of AMPD3.

Interestingly, there is a mutual repulsion between BCAA oxidation

and glucose metabolism (83). In

the DCM state, BCKDH cannot restrict the upregulation of AMPD3.

Subsequently, the uncoupling of AMPD3 activation induces excessive

adenine nucleotide degradation and ROS production. After knocking

out BCKDH-E1α in cardiomyocytes, the expression levels of PPARα,

CD36 and ATGL significantly increase, making the utilization of

cardiac substrates more inclined towards FA, which is similar to

the rat model of obese type 2 diabetes state (129).

FFAs derived from food are transported to

cardiomyocytes, with excess lipids stored in LDs and VLDL. VLDL and

LDL transfer lipids to the heart and adipose tissue. As TAG

reserve, LDs maintain the supply of circulating FAs and maintain

cardiac lipid homeostasis and energy demand (130). Most of the TAGs constituting

LDs come from lipoproteins and NEFAs, and a small amount of FA is

provided by the heart via de novo lipogenesis (DNL) pathway.

This process activates transcription factors such as

insulin-responsive SREBP1 and Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR), enhancing

adipogenic gene expression to drive FA trafficking into the ER for

neutral lipid synthesis (TAG and CE). Increased expression of

DGAT2, which regulates TAG synthesis in prediabetes and type II

diabetes, leads to abnormal nerve lipid signaling (131). In the presence of

electronegative LDL (-), the intracellular levels of NEFA, TAG and

ROS in cardiomyocytes lacking plin5 are substantially increased

(132). Acetylcholine may

reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis through PLIN5, activating the

interaction between LDL and mitochondria (133).

The biogenesis and degradation of LDs finely

regulate lipid homeostasis. Prolonged lipid excess in diabetic

heart triggers the dysfunction in cardiomyocytes, macrophages,

along with vascular endothelial cells, with lipotoxic injury being

the primary cause. The response of cardiomyocytes to different

kinds of FAs remains incompletely understood. Evidence suggests

that lipotoxicity is closely tied to FA saturation levels,

saturated FAs (SFAs), such as palmitate, hinder LD formation and

inflict significant cellular damage. The activation of the ULK1

autophagy signaling cascade may be linked to the ROS-dependent

NLRP3, driving IL-1β/IL-18 production, leading to subsequent

insulin signaling disruption. Conversely, unsaturated FAs such as

oleic acid encourage the accumulation of TAG in LDs and store

excess palmitic acid in the TAG pool, thereby preventing palmitic

acid from triggering apoptosis and consequently reducing lipotoxic

cellular damage (134). The

previously mentioned investigations have overlooked the potential

excess of FAs, while an appropriate amount of palmitic acid can

actually promote the formation of LDs.

The accumulation of TAG and stearoyl-CoA desaturase

1 in LDs enables endothelial cells to sequester palmitic acid and

prevent the palmitoylation of ciliary proteins, which would

otherwise lead to lipotoxic injury. Upon reinstating the supply of

PA, ciliary homeostasis is restored, subsequently delaying AS

(135). PA also activates the

Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4/MyD88 pathway in macrophages, triggering

expression of TNF-α and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (136,137).

Impaired TAG synthesis within cells can trigger

lipotoxicity, which is associated with the synthesis of lipotoxic

intermediates. Elevated DGAT2 expression in type 2 diabetic mice

promotes TAG synthesis (131).

Myocardial-specific knockout of DGAT1 significantly reduces LD

formation, leading to DAG and ceramide accumulation, which activate

PKCα and induce cardiac dysfunction (138); conversely, overexpression of

DGAT1 promotes TAG storage in LDs without harming the heart

(139). Lipid overload

upregulates CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα), increasing

the transcription of reticulon 3 (RTN3), subsequently driving LD

accumulation and cardiac dysfunction through the DGAT2-dependent

RTN3-FABP5 pathway (140).

Therefore, isolating TAG and promoting LD formation represent

potential strategies to alleviate lipotoxicity.

Lipotoxicity is closely associated with ROS; ROS

induces post-translational modifications of a-kinase anchor protein

121 (AKAP121), DRP1 as well as optic atrophy 1, enhancing

mitochondrial fission and leading to mitochondrial dysfunction

(141). Increased ceramide DAG

levels activate NADPH oxidase to damage mtDNA and reduce ATP

synthesis (142), ultimately

impairing left ventricular compensatory function (143). Targeting Sirt5 to mediate CPT2

dessuccinylation and C1q/tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related

protein 3 to inhibit mitochondrial apoptosis can reduce

lipotoxicity (144,145). CPT2 is a regulator of FA

uptake, and further studies have confirmed the relationship between

CD36 and lipotoxicity and ER stress. Endogenous H2S

stimulates Hrd1 to mediate S-sulfation to regulate VAMP3

ubiquitination and inhibit CD36 membrane translocation to reduce FA

uptake. Exogenous H2S can reduce ER stress and

lipotoxicity (146,147).

SREBP1c represents another potential target for

reducing lipotoxicity, p21-activated kinase 3 in the myocardium

promotes SREBP1c expression to induce lipid peroxidation deposition

through the mTOR/S6 kinase 1 pathway (148,149). SREBP1c activation linked to

myocardial injury in patients with aortic stenosis and metabolic

syndrome, and statins can trigger lipotoxic injury through the DNL

pathway (149,150).

LDs first convert stored constituent lipids into

active lipid mediator precursors, which then generate active lipid

mediators that interact with cells to interact with cells and

participate in inflammatory responses. FAs stored in LDs include

SFAs, monounsaturated FAs and PUFAs, of which PUFAs are precursors

of two key lipid mediators-pro-inflammatory eicosanoid compounds

are mainly derived from ω6-PUFAs, while specific pro-resolved

mediators (SPMs) are derived from ω3-PUFAs (151).

Active lipid precursors on the monolayer PL shells

of LDs rely on cytosolic phospholipase A2α to produce lysoPLs and

PUFAs such as arachidonic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), along

with docosahexaenoic acid. TAG releases PUFAs through the lipolytic

pathway mediated by ATGL and HSL. During ATGL-regulated lipolysis,

released FFAs act as agonists for FFA receptor 4 (FFA4), which in

turn inhibits adenylate cyclase via Gi/o protein and

reduces high levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in LDs

and ER regions, thus balancing energy mobilization and storage.

FFA4 thus regulates the lipolysis process at LDs through cellular

endocrine signaling (152).

EPA inhibits TGFβ-mediated myocardial fibrosis via

FFA4, possibly through its ability to activate PKC and induce

phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)

(153). Cyclooxygenase (COX)

co-localizes with 5-lipoxygenase on the LDs' surface, cooperatively

regulating the generation of lipid mediators (154). Although eicosanoids and SPMs

produced by COX and LOX have partial anti-inflammatory properties,

immune and inflammatory responses can also be stimulated by these

mediators via their interactions with receptors such as PPARs and

TLRs (155). However,

hypoxia-induced overexpression of the LD-associated protein

(HILPDA) inhibits ATGL-mediated lipolysis and obstructs the

generation of prostaglandin E2 as well as interleukin-6 (156). Similarly, the removal of HILPDA

in adipose tissue reduced LDs' accumulation and lipid excess,

although did not ameliorate inflammation, possibly due to tissue

specificity (157).

Research shows that viruses and bacteria can target

and interact with LDs. The integration of ORF6 into the LD

monolayer is mediated by its two amphipathic helices. ORF6 inhibits

UBXD8-Plin2 binding in LD-mitochondrial interactions to enhance

lipolysis, and it also promotes lipid synthesis by binding to

DGAT1/2 at LD-ER contact sites. Finally, accelerated FAO provides

energy for virus replication (84). It has been recently indicated

that LDs are not just energy storage units but also help regulate

immune responses in cells like macrophages. Pneumococcus

accelerates LDs' accumulation in macrophages by producing ROS

through glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase (158), Mycobacterium

tuberculosis protein (Mtb) Ure C inhibits DNA repair in

macrophages, genomic instability and intracellular micronucleus

stimulation activate the cGAS-STING pathway, phosphorylating TBK1

and IRF3 to induce IFN-β to upregulate the scavenger receptor SR-A1

as well as promote the formation of LDs that provides energy for

pathogen survival (114).

Subsequently, Mtb activates the anti-glycolysis G protein-coupled

receptor 109a, shifting macrophages from glycolysis to the ketone

body synthesis pathway and accelerating foamy transformation

(159). Thus, targeting the

composition and formation of LDs may be a new direction for

immunotherapy.

ROS are generated by the cytosolic nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX) as well as

mitochondrial ETC complexes Ⅰ/Ⅱ/Ⅲ. Large amounts of ROS damage

mitochondria and affect cellular homeostasis. Therefore, the

presence of LDs makes it possible for cells to store excess FFAs

and also relieves oxidative stress and reduces the accumulation of

lipotoxic intermediates; storage of FAs occurs through their

incorporation into neutral lipids' pools. In times of energy demand

such as starvation and cellular nutrient deprivation, it is

supplied to mitochondria to maintain energy production.

During energy stress, PDM facilitates targeted

transfer of FA from LDs to mitochondria, rapidly replenishing

energy deficits while mitigating lipotoxicity damage caused by FA

accumulation (75). Besides PDM,

LDs can transport FAs to lysosomes via an autophagy-dependent

pathway for cytoplasmic release and mitochondrial energy supply.

This mechanism appears better suited for energy-deficient states

such as starvation (160,161).

Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) enrichment after aerobic

exercise reduces LD accumulation and increases FAO levels in PDM.

Mfn2 acts as a mitochondrial outer membrane protein that enables

mitochondria to link both LD and ER (162,163). It is hypothesized that PDM may

promote FAO through a special pattern related to Mfn2 (164). After the interaction between

Mfn2 and ATGL, the lipolysis of liver LDs, FA transport and the

formation of more PDM are enhanced, and the ATP synthesis capacity

and high FAO level of PDM are maintained (165). Mfn2 as well as LD-localized

Hsc70 assemble into a complex to promote FA transfer in myocardial

LDMC. Upregulation of Mfn2 after lipid overload may restore the

coupling between LDs and mitochondria and reduce

lipotoxicity-induced myocardial damage via the ubiquitin-proteasome

degradation pathway (166).

However, the mechanisms of lipids' transfer from

LDs to mitochondria remain uncertain. Investigations show that

mitochondria and ER contact sites enlist seipin to accelerate LDs'

biosynthesis and lipid transfer, mitigating neutral lipid

accumulation. Mutations in the seipin protein can result in

irregularities at the LD-ER contact interface, suggesting its

potential role in regulating the construction of membrane bridges

by stabilizing this contact interface (167). Seipin keeps the level of

phosphatidic acid in the ER under control and achieves protein

transport through LD-ER contact, transferring TAG to nascent LDs

and counteracting the shrinkage of small LDs induced by LD

maturation (168,169).

Seipin forms a complex with Oxysterol binding

protein-related protein 5 (ORP5) and ORP8 within the PA-enriched

mitochondrial-associated membrane subdomain. ORP8 enhances

interaction with ORP5 via a coiled-coil domain, maintaining lipid

transport across the mitochondrial ER-LD tri-interface and

promoting LD biogenesis (67).

This mechanism is widely conserved in mammals. Additionally, there

are two necessary factors for Plin5 transferring FAs from LDs to

mitochondria: Plin5 requires PKA-mediated phosphorylation at serine

155 and an intact C-terminal domain (31). Its interaction with the chaperone

ACSL4 at the MCS enables the conversion of FA into acyl-CoA for

FAO, completing the lipid movement from LDs to mitochondria

(170,171).

ER stress, featured by insufficient protein folding

capacity, calcium ion imbalance as well as lipid metabolism

disorder, is a key metabolic feature of DCM (172). Increased intracellular lipid

accumulation induces ER stress and LD formation. It has been

suggested that ER stress can degrade Plin2 and inhibit the

generation of LDs (48),

therefore it can be concluded that LDs and ER stress influence each

other. Researchers point out that ROS-triggered ER stress in DCM

induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis mainly through protein kinase

RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) pathway, but not IRE1 or activating

transcription factor (ATF) 6 signaling pathways (173). At this time, G protein-coupled

receptor 78 (GPR78) dissociates from PERK, and PERK activates the

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit α/ATF4 pathway

to enhance cardiac autophagy and alter normal myocardial morphology

(174).

LDs likely represent a common therapeutic for

mitigating ER stress and preserving lipid homeostasis. Patients

with HF with preserved ejection fraction exhibit decreased LDs and

PDMs, abnormal LD dynamics, lipid overload, and downregulation of

X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), which affects the ER degradation

enhancing alpha mannosidase-like protein 2 (EDEM2), which regulates

protein glycosylation, endoplasmic reticulum-associated

degradation, and maintains ER stability (175). The absence of XBP1 or EDEM2 in

cardiomyocytes leads to decreased cardiac systolic function and

exacerbates LD formation and lipid disorders. Under excessive FFA

stimulation, EDEM2 interacts with SEC23A in an ATGL-dependent

manner to efficiently alleviate lipotoxic damage, including

myocardial LDs' accumulation and elevated TAG and DAG levels

(176). These data suggest that

enhancing cellular lipid oxidation and accumulating comparatively

'non-toxic' lipids to partially regulate lipid flow may be a viable

approach to reduce lipotoxicity (177).

LDs participate in the regulation of normal cell

division, ferroptosis, autophagy as well as other cellular

processes and indirectly affect the progression of DCM. LD

regulates normal cell division and induces DGAT-dependent LD

biosynthesis during cell cycle arrest. The G0/G1 switch 2 gene

(G0S2) inhibits ATGL-mediated TAG hydrolysis and prevents excessive

leakage of PUFAs within TAG, which is essential for LDs to protect

cells against ferroptosis (178). During iron depletion, cells

enhance LD biosynthesis through the DGAT1-dependent pathway to

regulate mitophagy and maintain cellular homeostasis (179).

During the process of DCM micro-autophagy, Rab7 is

phosphorylated at the 183 site of tyrosine and interacts with

Rab-interacting lysosome protein (Rilp) to accelerate the lipolysis

of LDs via the lysosomal pathway (81). Additionally, RAB18 may regulate

the process of autophagy by downregulating adipogenic genes'

expression and reducing TC and TAG levels. RAB18 knockout did not

affect lipolysis gene expression, but the liver lipophagy was

weakened and LD accumulation was observed in mice (180). While RNA is mainly involved in

the transmission of genetic information, it was recently revealed

that RNA regulates lipid metabolism (181). Previous experiments have shown

that overexpression of LIPTER can alleviate cardiac dysfunction and

ameliorate cardiomyopathy in mice, and that LIPTER in

cardiomyocytes connects long non-coding RNAs to strengthen the

connection between LDs and actin by binding

PA/Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate and interacting with myosin

heavy chain 10 protein, facilitating LD transfer (182) (Fig. 5).

Abnormal cardiac LD accumulation constitutes a key

feature of cardiac steatosis in diabetic patients. It is associated

with a large accumulation of TAG and an enhanced lipolytic barrier

in the heart after overexpression of Plin5 (64,183). This imbalance in LD dynamics

accelerates ventricular remodeling and cardiac dysfunction. Studies

in PPARα knockout mice have shown reduced TAG accumulation after

fasting, while normal mice fasting for 16-48 h exhibit an

upregulation of Plin2 expression and a concurrent increase in

accumulation of LDs (184),

suggesting that LDs can provide energy supply. Cardiac lipid

accumulation is independent of systemic metabolism, and PPARα

downregulation itself does not induce cardiac pathology (185).

During starvation, vacuolar protein

sorting-associated protein 13D (VPS13D), endosomal sorting complex

required for transport protein tumor susceptibility 101, along with

adaptor-binding domain of VPS13, facilitate FAs transport at the

LDMC site to achieve high-efficiency oxidation (186). This pathway may become

dysregulated in diabetic hearts due to chronic energy excess.

LD-associated proteins form a complex regulatory

network in the heart. Reduced expression levels of ATGL and CGI58

jointly impair lipolysis, which instead increases TG synthesis,

promotes cardiac steatosis, and raises oxidative stress levels

(65). Plin2 is involved in

regulating LDL hydrolysis, and the increased TAG accumulation

following Plin2 knockout may be associated with lipophagy.

Overexpression of Plin2 reduces HSL levels, suggesting that energy

stress during metabolic remodeling stimulates Plin2 to enhance

lipase affinity for LDs, consequently exacerbating cardiac

steatosis and dysfunction (53,187).

Plin5 inhibits lipolysis to preserve TAG storage

within LDs, thereby limiting the rate of FAO and reducing excessive

oxidative stress in heart. Upon Plin5 knockout, the upregulation of

PPARα as well as PGC-1α induces mitochondrial proliferation,

resulting in higher FAO and lipolysis, which can worsen cardiac

hypertrophy potentially leading to HF (188). The deletion of Plin5 exerted no

notable impact on heart function. During fasting, Plin5 associates

with Rab8a in skeletal muscle and collaborates with ATGL, this

process couples LCFAs transfer from LDs to mitochondria, indicating

that Plin5 may have a cardioprotective effect through preserving

mitochondrial integrity (64,189).

Myocardial steatosis and fibrosis are the basis of

ventricular remodeling in DCM. Computed tomography scans of

patients with MI have revealed substantial lipid deposition

(190). Reduced expression of

eNOS at the infarct site exacerbates abnormal myocardial lipid

accumulation. This in turn promotes LD formation, increases

oxidative stress, and activates the TGFβ/TβRII pathway,

phosphorylating Smad2/3, inducing Smad4 to modulate transcription

of ECM genes and hindering myocardial repair (190,191).

Macrophages also help regulate fibroblast

activation through IL-1β and its downstream target mesenchyme

homeobox 1 (116). In fact, the

process of macrophage-to-myofibroblast transition (MMT) may involve

LD regulation. In chronic pancreatitis, high expression of

mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) regulates ACSL3 to

promote acinar cell release of LDs. Stimulation of SIRT1 and

activation of downstream TGF-β/Smad3 signal transduction affect MMT

and fibrosis process, while whether UCP2 has a similar regulatory

effect still needs to be explored (192).

In this process, ATGL-dependent lipolysis promotes

FA accumulation and inhibits ECM remodeling in fibroblasts

(193). Low levels of CGI58 in

the heart decrease the lipolysis rate and aggravate oxidative

stress and myocardial steatosis (65). This indicates that the regulation

of lipolysis is particular to cell type.

In addition to lipid metabolic disorders,

alterations in cardiomyocyte energy metabolism are also considered

to indirectly affect fibrosis progression (194). Wilms' tumor 1-associating

protein promotes AR methylation in a YTHDF2-dependent way,

subsequently promoting FAO proliferation, along with cardiac

fibroblasts migration (195).

Direct investigations of cardiac fibroblasts and

LDs are limited; however, alternative cellular models offer

insights. In mouse embryonic fibroblasts, FAs generated by

non-specific autophagy can be directed to LDs. This process is

considered a protective regulatory technique, as LDs sequester

excess FFAs to mitigate lipotoxicity (196). DGAT1 can channel FFAs generated

during mTORC1-regulated autophagy to TAG-rich LDs, which then hold

onto the FAs and reduce mitochondrial damage caused by

acylcarnitine accumulation (160). TANGO2 is associated with LDs

and the ER to modulate acyl-CoA metabolism. The cardiomyopathy and

arrhythmia caused by the TANGO2 mutation may result in disturbance

of LDs' morphology, function, and neutral lipid metabolism

homeostasis. Consequently, lipid peroxide levels in

TanGO2-deficient fibroblasts were raised metabolized, and LDs

increased (197). Patients with

neutral lipid storage disease with myopathy exhibit muscular,

cardiac and hepatic impairment due to defective LD functions,

similar to cells deficient in ATGL or CGI58, therefore providing a

suitable model for investigating LD function (198). Collectively, these findings

suggest that LDs may influence cardiac steatosis and myocardial

fibrosis.

Cardiac lipid-lowering therapeutics have gained

substantial research attention over recent decades. Emerging

strategies now target multiple approaches of cellular lipid

homeostasis, including biosynthesis, uptake, trafficking and

catabolism, with the dynamic regulation of LDs representing a

critical target. Currently, pharmacological approaches targeting

LDs encompass three principal mechanisms: Modulating lipid

metabolism to prevent excessive accumulation, indirectly

suppressing LD biogenesis, and promoting LD degradation through

enhanced lipophagy or lipolysis pathways (197,199).

Statins lower blood lipids by blocking the

mevalonate pathway, inhibiting Rho/Ras/Rac, and activating PPARα/β,

resulting in anti-inflammatory pleiotropic effects (200,201). They also downregulate the

expression of Plin5 in hepatocytes (202). However, long-term usage of

activated cardiac SREBP1 to speed up the process of DCM may make

myocardial lipid deposition and lipid peroxidation worse (149). Niacin reduces the progression

of atherosclerosis by diminishing the synthesis of proinflammatory

cytokines by macrophages (203). It also facilitates reverse

cholesterol transport through adipocyte lipolysis via the cAMP/PKA

and 15d-PGJ2/PPARγ pathways, inhibits the expression of Plin4 in

neuroblastoma to prevent the formation of LDs and promotes

macrophage polarization to the anti-inflammatory M2 type (204,205). However, the regulating

mechanism of cardiac LDs remains ambiguous. CL2-57, an ABCA1

inducer that targets cholesterol transport, promotes cholesterol

efflux from macrophages, reduces inflammation, and prevents lipid

abnormalities caused by LXR agonists (206,207). The MEK1/2 inhibitor (U0126) in

conjunction with the LXR ligand (T0901317) modulates lipid

metabolism through lipolysis and FAO to reduce LXR-associated

adverse effects (208). IL4 via

the STAT6/PPARγ axis, boosts ABCA1/ABCG1 expression, decreases

lipid overload and foam cell formation, and stimulates M2

polarization to control late adipogenic phase suppression, which

prevents inflammation and formation of LDs (199). Notably, IL4 did not influence

C/EBPβ and PPARγ in lipogenesis and lipid metabolism during the

first phase of lipid synthesis, nor did it affect HSL. Moreover,

ezetimibe impedes cholesterol absorption (209,210). In addition, ezetimibe can

accelerate LDs synthesis through LD-mitochondrial membrane contact

sites, store excess FAs in LDs, reduce lipotoxic damage, and at the

same time, LDs degradation may also be accelerated, thus alleviates

podocyte apoptosis (211). It

indicates that LD-organelle interaction may serve as an effective

target for intervention. Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9

(PCSK9) inhibitors enhance LDL-LDLR binding by preventing LDLR

degradation and promoting lipophagy to eliminate lipids (212), with PCSK9 mediating lipid

degradation independently of LDLR (213). Inclisiran, a small interfering

RNA targeting PCSK9, significantly reduces LDL-C levels in patients

with cardiovascular risk (214). This effect may be associated

with the suppression of AKT activation, affecting downstream mTOR

and the facilitation of ULK1 kinase complex formation, which

regulates Beclin1 and enhances the degradation of intracellular

lipids via lipophagy (215).

Short-term continuous and excessive administration

of prednisolone substantially elevates the mRNA levels of CGI-58,

CEIDE-C and CEIDE-A in serum FA and adipose tissue and reduce the

expression of G0S2 mRNA. CIDE proteins block ATGL-mediated

lipolysis and promote lipid storage (216,217), indicating that prednisolone is

involved in both lipolysis and lipid storage through complex

pathways and alleviates insulin resistance by inhibiting insulin

receptor phosphorylation and Akt activation (218,219).

Fibrates, such as fenofibrate, activate PPARα to

reduce blood glucose and lipid levels, modulate insulin resistance,

markedly enhance cardiac function, and maintain glucose metabolism

via the downstream Nr4a1/hexokinase 2 pathway. They also enhance

the sirtuin 3/superoxide dismutase 2 pathway to achieve

anti-oxidative stress (122,220). Furthermore, the elevation of

LC3 and SQSTM1 in a diabetic condition hinders the heart's

autophagic capacity, potentially linked to the formation of LD and

macrophage foam cells. Fenofibrate restores autophagy ability

through FGF21/SIRT1 to alleviate macrophage foam cell formation and

myocardial fibrosis caused by LD accumulation (221).

Pemafibrate, a novel PPARα agonist, also improves

cardiac diastolic function in diabetic patients (222). Thiazolidinediones, such as

troglitazone, reduce lipotoxicity through AMPK activation, but

full-acting PPARγ agonists are associated with obesity and cardiac

risk (223,224). However, the incomplete agonist

dihydrosanguinarine is safer, reducing LD accumulation and

enhancing glucose uptake (225). SGLT2i inhibitors exhibit

multidimensional cardioprotection: Empagliflozin regulates

autophagy balance through AMPK/GS3Kβ and mTOR/ULK1 pathways

(79). In vitro models of

SGLT2i inhibitors all increase LD biosynthesis in a DGAT1-dependent

manner, but the specific pathways differ. Canagliflozin does not

reduce LD formation in vascular endothelium via an AMPK-dependent

pathway, while empagliflozin may reduce lipogenesis through the

SREBP1/PPARγ pathway (226,227). In the meantime, empagliflozin

also reprograms energy metabolism in podocytes, inhibiting glucose

utilization and switching to FAs for energy, enhancing lipolysis

and ketone body formation, providing additional fuel for the heart,

and alleviating ER stress and lipotoxicity, which is extremely

similar to metabolism shift observed in the diabetic heart

(228-230). In summary, as the intersection

of metabolism and inflammation, the formation and decomposition of

LDs and the targeted intervention of cellular homeostasis

constitute an emerging therapeutic frontier in DCM.

Despite gaining substantial progress,

investigations of LD biology in DCM exhibit critical knowledge

gaps. Studies on LDs in cardiac fibroblasts and vascular

endothelial cells remain markedly underdeveloped, while the

existing studies on macrophages have predominantly focused on M1

and M2 polarization states, neglecting other types related to DCM

pathogenesis. The present review predominantly explores the role of

LDs in DCM and does not comprehensively address their involvement

in other heart diseases, such as atherosclerosis and HF. Exploring

dynamic functions of LD across diverse cardiovascular diseases

would provide comprehensive insights into their regulatory

mechanisms and therapeutic potential in the heart.

Contemporary understanding of LD evolved beyond

their classical role as inert lipid reservoirs to recognize their

multiple regulatory functions in metabolic substrates, oxidative

stress responses, inflammation, immunity, and cellular processes

such as autophagy and ferroptosis, ER stress.

LDs sequester excess lipids through diverse

mechanisms, effectively mitigating the accumulation of lipotoxic

intermediates that trigger cellular oxidative damage. In addition,

LDs catabolize stored lipids to supply FAs for oxidation and delay

cardiac energy depletion. Under pathological conditions, lipophagy

attenuates myocardial injury induced by glucotoxicity and

lipotoxicity while delaying myocardial fibrosis remodeling and

macrophage foam cell formation. LDs participate extensively in cell

proliferation, development and signal transduction, with

LD-associated proteins maintaining cellular metabolic homeostasis

through protein-protein interactions that modulate signaling

cascades. However, research on macrophages and fibroblasts remains

in its infancy. As central hubs of lipid metabolism, LDs critically

influence metabolic homeostasis, and their dysregulation drives

metabolic imbalance in DCM. Therapeutic strategies targeting LD

accumulation include modulating lipid metabolism, interfering with

Plin2 or DGAT1 to inhibit biogenesis, and promoting lipophagy and

lipolysis to accelerate degradation. PDM localize at LD surfaces

and establish functional coupling that facilitates metabolic

exchange, suggesting that mitochondrial-directed interventions,

including regulation of FAO rate or antioxidant treatment, may

alleviate LDs accumulation. However, the safety profiles and

off-target effects of these approaches remain incompletely

characterized, and existing pharmacological agents exhibit

significant adverse effects that necessitate mechanistic

clarification for rational drug development. Understanding of the

regulation of heart function by LDs remains limited. The mechanism

of action of LDs in each stage of DCM still needs to be studied,

and the impact of the cellular heterogeneity of LDs on the

occurrence of DCM remains unclear. The development of related drugs

targeting LD to reduce lipid deposition holds great promise for the

treatment of DCM.

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

YL was responsible for conceptualization of the

review, literature search, drafting of the manuscript, and

visualization of table and graphs. XF conceived the study, wrote

the original manuscript and prepared the figures. XG, YJ, WS, XSu,

JG and GY curated data and collected references. BZ, ZZ, YK and XSh

organized the table, JZ acquired funding and contributed to writing

review and editing. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 8257152346 and 82574965), the QI

HUANG Scholars (Junping Zhang) Special Funding [National TCM

People's Education Letter (2022) No. 6] and the Inheritance and

Innovation Team for Traditional Chinese Medicine Prevention and

Treatment of Atherosclerosis (grant no. 4042502037).

|

1

|

Seferović PM, Paulus WJ, Rosano G,

Polovina M, Petrie MC, Jhund PS, Tschöpe C, Sattar N, Piepoli M,

Papp Z, et al: Diabetic myocardial disorder. A clinical consensus

statement of the heart failure association of the ESC and the ESC

working group on myocardial & pericardial diseases. Eur J Heart

Fail. 26:1893–1903. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Segar MW, Khan MS, Patel KV, Butler J,

Tang WHW, Vaduganathan M, Lam CSP, Verma S, McGuire DK and Pandey

A: Prevalence and prognostic implications of diabetes with

cardiomyopathy in community-dwelling adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.

78:1587–1598. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lewis GF, Carpentier A, Adeli K and Giacca

A: Disordered fat storage and mobilization in the pathogenesis of

insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 23:201–229.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Olzmann JA and Carvalho P: Dynamics and

functions of lipid droplets. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:137–155.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Varghese M, Kimler VA, Ghazi FR, Rathore

GK, Perkins GA, Ellisman MH and Granneman JG: Adipocyte lipolysis

affects Perilipin 5 and cristae organization at the cardiac lipid

droplet-mitochondrial interface. Sci Rep. 9:47342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kuramoto K, Sakai F, Yoshinori N, Nakamura

TY, Wakabayashi S, Kojidani T, Haraguchi T, Hirose F and Osumi T:

Deficiency of a lipid droplet protein, perilipin 5, suppresses

myocardial lipid accumulation, thereby preventing type 1

diabetes-induced heart malfunction. Mol Cell Biol. 34:2721–2731.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kolleritsch S, Kien B, Schoiswohl G,

Diwoky C, Schreiber R, Heier C, Maresch LK, Schweiger M, Eichmann

TO, Stryeck S, et al: Low cardiac lipolysis reduces mitochondrial

fission and prevents lipotoxic heart dysfunction in perilipin 5

mutant mice. Cardiovasc Res. 116:339–352. 2020.

|

|

8

|

Jebessa ZH, Shanmukha KD, Dewenter M,

Lehmann LH, Xu C, Schreiter F, Siede D, Gong XM, Worst BC, Federico

G, et al: The lipid-droplet-associated protein ABHD5 protects the

heart through proteolysis of HDAC4. Nat Metab. 1:1157–1167. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kuo CY, Tsou SH, Kornelius E, Chan KC,

Chang KW, Li JC, Huang CN and Lin CL: The protective effects of

liraglutide in reducing lipid droplets accumulation and myocardial

fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 82:392025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bosma M, Dapito DH, Drosatos-Tampakaki Z,

Huiping-Son N, Huang LS, Kersten S, Drosatos K and Goldberg IJ:

Sequestration of fatty acids in triglycerides prevents endoplasmic