Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) accounts for 10-15%

of all stroke cases, with >2 million patients worldwide

annually. Characterized by complex pathophysiology and a one-month

mortality rate of ~70%, ICH poses a severe clinical challenge

(1-7). Globally, the incidence of ICH has

demonstrated an upward trend with advancing medical understanding

(8,9), driven by factors such as the

increasing elderly population, widespread use of anticoagulants,

antiplatelets and thrombolytics (10,11). While preclinical research using

animal ICH models has yielded promising developments in potential

treatments (12-15), the absence of evidence-based

therapeutic strategies in clinical settings remains a critical

barrier to improving ICH prognosis. This gap underscores the urgent

need for translating preclinical advancements into clinically

viable interventions to address the unmet therapeutic needs in ICH

management.

Following ICH, rupture of brain parenchymal vessels

leads to erythrocytes accumulation and hematoma formation, which

directly compresses brain tissue and causes primary brain injury

(PBI). In the hematoma, erythrocyte hemolysis releases toxic

hemolytic products that induce secondary brain injury (SBI) and

irreversible neurological deficits (16,17). Mounting evidence indicates that

inflammatory responses are central to the pathophysiology of SBI

(18). During this process,

circulating monocyte-derived macrophages and resident microglia in

the central nervous system (CNS) infiltrate the hemorrhagic site.

These microglia/macrophages serve as key regulators of

neuroinflammation and hematoma resolution mitigation in SBI

(19,20), highlighting their critical role

in shaping post-ICH neuroinflammatory trajectories and potential as

therapeutic targets.

Microglia, the primary immune cells of the CNS,

constitute 5-10% of brain cells and are often referred to as the

'resident macrophages' of the brain (21,22). They interact dynamically with

neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes under physiological

conditions, playing a fundamental role in sustaining brain

homeostasis (23). The highly

plastic nature of microglia, including their phenotypic diversity,

hinges on the type of stressor or neuropathology that they

encounter (24). Specifically,

during distinct pathological phases of ICH, microglia polarization

generates pro-inflammatory (M1-like) or anti-inflammatory (M2-like)

mediators, which directly influence the progression of ICH and

neurological outcomes (20,25). This dual functionality

underscores the central role of microglia in modulating

neuroinflammation and tissue repair after ICH.

The hematoma and hemolysis resulting from ICH

trigger robust microglial activation, exacerbating

neuroinflammation (26,27). Chang et al (28) demonstrated that microglia rapidly

respond to hemorrhagic insult within 1-1.5 h after ICH onset by

initially adopting a protective phenotype, in which IL-10 mediates

microglial phagocytosis of hematoma components and promotes

hematoma resolution, thereby highlighting the early protective role

of microglia in mitigating SBI. By contrast, microglial depletion

exacerbates brain damage after ICH, manifesting as brain swelling,

neuronal degeneration and worsened neurological impairments

(29-31). Critically, emerging evidence

suggests that microglia do not act in isolation. Therefore, the

present review will discuss whether the pathological and reparative

processes following ICH are determined not by any single cell type,

but by a microglia-centered, spatiotemporally dynamic neuroimmune

network. The present review systematically evaluated the microglial

inflammatory response and its therapeutic targets after ICH, while

integrating current understanding of their anti-inflammatory

therapeutic potential. Notably, key hurdles to clinical translation

were emphasized, including ICH-induced iron overload, mass effect,

persistent inflammatory responses and oxidative damage.

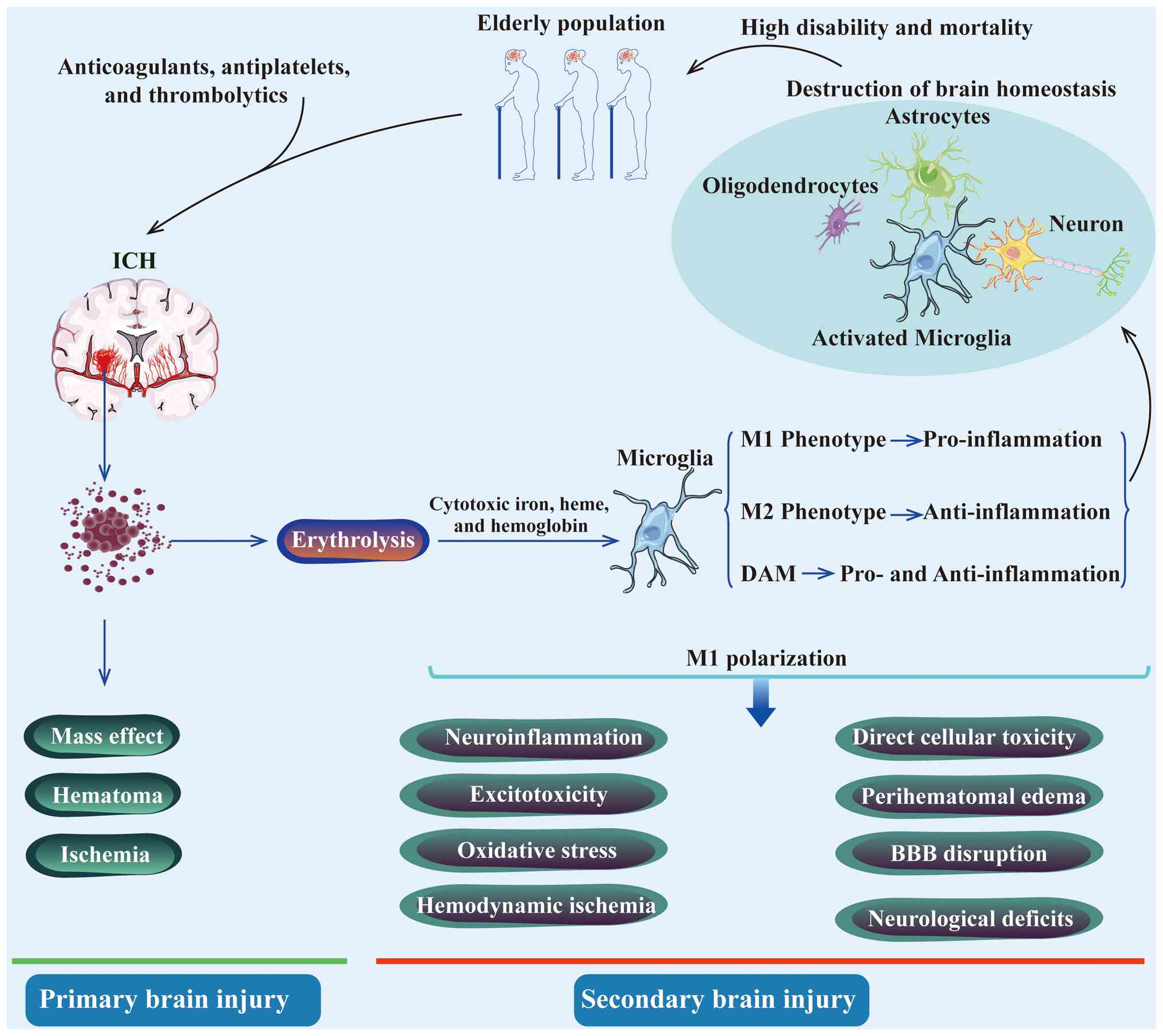

ICH-induced brain injury, characterized by a high

risk of recurrent bleeding and ischemia, typically unfolds as a

cascade of pathological processes comprising two successive stages:

PBI and SBI (32,33). During the PBI stage, blood from

ruptured vessels forms a hematoma within the first few hours,

exerting a mass effect through mechanical compression of brain

parenchymal structures. This process leads to elevated intracranial

pressure and potential brain herniation, often managed clinically

through advanced surgical interventions (33,34). The SBI stage follows, driven by

hemolytic products from erythrolysis, including hemoglobin, heme,

free iron, along with neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity and

oxidative stress (35-38). Concomitant pathological changes

include hemodynamic ischemia, cerebral edema exacerbation, direct

cellular toxicity and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption

(1,15,18,35,39,40). Hemolytic byproducts infiltrate

the perihematomal region, activating microglia/macrophages for

hematoma clearance (7,39,41,42), while thrombin activation

contributes to vasculogenic edema via endothelial cell and BBB

damage (43). Perihematomal

edema (PHE), a hallmark of SBI linked to poorer prognosis, has

emerged as a key therapeutic target in post-ICH pathophysiology

(44-46). Additionally, intracranial

hematomas can expand into adjacent brain tissue via perivascular

spaces, white matter tracts and perineurium, distorting and

disrupting nerve fibers beyond repair (7,47,48). Collectively, these SBI-related

pathological changes culminate in permanent brain tissue damage and

severe neurological deficits, underscoring the critical need for

continuous focus on mitigating SBI mechanisms in ICH management

(43,49).

The neuroinflammatory response following ICH is a

highly dynamic and temporally regulated process, in which

microglial polarization plays a central role. Post-ICH

neuroinflammation evolves through distinct yet overlapping phases,

each characterized by specific pathological drivers, shifting

microglial phenotypes and unique molecular signatures. This

chronological progression dictates the functional outcome of

microglia, transforming them from sentinels of acute damage to

modifiers of chronic recovery. Understanding this temporal

regulation is therefore central for deciphering the dual roles of

microglia in injury exacerbation and resolution, and for designing

stage-specific therapeutic interventions.

ICH-induced hematoma represents a primary driver of

brain injury. A rapid neuroinflammatory reaction emerges within

minutes to hours post-ICH ictus, characterized by glial population

activation and the production of cytotoxic factors, reactive oxygen

species, matrix metalloproteinases and related pro-inflammatory

mediators (50). Single-cell RNA

sequencing of peri-injury cortical tissue from patients with

traumatic brain injury (TBI) and ICH identified five microglial

subpopulations: (i) Homeostatic; (ii) pro-inflammatory; (iii)

stressed; (iv) ribosome biogenesis; and (v) phagocytic (51). Specific knockout of microglial

C5aR1 ameliorated neurological outcomes in mice with TBI and ICH,

attenuating neuroinflammatory responses and reducing cerebral edema

(51). Concurrently, within

hours to days, extravasated erythrocytes in the hematoma release

neurotoxic blood products, including cytotoxic iron, heme and

hemoglobin, triggering SBI and inducing persistent cerebral edema

and progressive tissue damage (52,53). Emerging evidence highlights

regulatory mechanisms that may mitigate this process by modulating

the CCR4/ERK/Nrf2 signaling pathway and activating peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ). These mechanisms

facilitate microglial phagocytosis and phenotypic polarization

toward immune homeostasis, offering potential therapeutic

strategies to counteract SBI (34,54,55).

The breakdown of the BBB and subsequent cerebral

edema represent life-threatening events in ICH (56,57). Microglia, through nuclear

receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1, can alleviate

neuroinflammation in the acute phase after stroke and ameliorate

ischemic brain injury (58).

Accumulating evidence highlights the key role of microglial

activation in driving SBI after ICH (59,60). Microglial M1 polarization

promotes the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, exacerbating

neuroinflammation (61,62). Chen et al (63) demonstrated that TNF-α derived

from M1-type microglia induces endothelial necroptosis, resulting

in BBB disruption. In ischemic stroke models, anti-TNF-α therapy

significantly mitigated endothelial necroptosis, BBB damage and

neurological deficits, underscoring the causal link between

microglial inflammation and vascular pathology. Neuroprotective

agents have been shown to attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced NO

release, TNF-α secretion and NF-κB activation in microglia, while

promoting anti-inflammatory cytokine production to protect the BBB

and facilitate neural repair (64-66). Similarly, cytokines such as IL-4

and IL-10 promote microglial polarization toward an

anti-inflammatory phenotype termed M2, emerging as potential

therapeutic targets for modulating BBB integrity after ICH

(67).

Previously, microglial subtype termed

disease-associated microglia (DAM) was identified through

transcriptional single-cell analysis in the brains of Alzheimer's

disease (AD)-transgenic (Tg-AD) mice and triggering receptor

expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2)−/− Tg-AD mice

(68-70). The differentiation of microglia

into DAM occurs in two distinct phases, including an initial

TREM2-independent activation program, followed by a TREM2-dependent

maturation stage. This specialized microglial subset exhibits the

potential to limit neurodegeneration, offering critical insights

for future therapy in AD and other brain disorders (70,71). Subsequent genome-wide

transcriptomic analyses revealed the presence of DAM-like states

across diverse pathological contexts, including aging and ALS

(70). While DAM shares partial

molecular overlap with the classical M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype,

their transcriptional signatures exhibit distinct differences

(72). Notably, transcriptomic

profiling of microglial activation in AD and aging models has

revealed that DAM co-expresses anti- and pro-inflammatory

sub-programs, highlighting their dual functional complexity

(73,74). The progressive transition from

homeostatic microglia to reactive DAM is critically dependent on

TREM2, a receptor predominantly expressed on microglial surfaces

(75-77). After ICH, activated TREM2 in

perihematomal regions mitigates neuronal loss, neuroinflammation

and neurological deficits through the activation of the PI3K/Akt

signaling pathway (78). The

activation of TREM2 can significantly alter the phagocytic and

inflammatory functions of microglial cells, making it a critical

regulator of DAM polarization (79). Additionally, exosomes derived

from human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cells

(hiPSC-NSC-Exos) have been shown to suppress pro-inflammatory

cascades in DAM within AD mouse models (80). Wang et al (81) further demonstrated that

hiPSC-NSC-Exos stabilize the BBB by downregulating monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1 secretion in astrocytes via the PI3K/Akt

pathway activation, underscoring the therapeutic versatility of

DAM-targeted interventions across neurological diseases (81). Moreover, Gao et al

(74) reported that

transcription factors such as IRF1, CEBPα and LXRβ modulated anti-

and pro-inflammatory DAM gene expression through regulating the Erk

signaling pathway. Collectively, these findings underscore the

notable sensitivity of microglia to dynamic pathological cues in

brain tissue, emphasizing their role as highly plastic sensors and

effectors of CNS injury and disease.

Notably, several studies have explored the

spatiotemporal specialization of microglial subsets during

evolution and disease, leveraging single-cell analyses to define

precise molecular signatures and cellular dynamics (82,83). Olah et al (84) identified that 9/10 myeloid

clusters express high levels of microglia-enriched genes (such as

C1QA, C1QB, C1QC and GPR34), and they identified these nine

clusters as distinct microglial clusters. Ochocka et al

(85) demonstrated microglial

cellular and functional heterogeneity through scRNA-seq and flow

cytometry by isolating distinct microglial clusters with unique

gene expression profiles and functional roles, revealing that in

naïve and GL261 glioma-bearing mice, reactive microglia exhibited

spatially segregated distributions when analyzing CD11b+

myeloid cells. Furthermore, Hammond et al (86) and Li et al (87) revealed that microglial

heterogeneity reaches its peak during early development, indicating

that microglia exhibit diverse transcriptional states across

development, homeostasis, aging and disease (88). These findings not only identify

microglial subclasses linked to neurodegenerative diseases and

behavioral disorders but also provide a framework to dissect the

multifaceted roles of microglia in human brain pathologies

(89).

Following ICH, modulators of microglial activation

and polarization, including key signaling pathways, transcription

factors and specific markers of M1/M2 subclasses, hold clinical and

translational importance, providing a basis for modulating

microglial function to mitigate brain injury (38). While the classical M1/M2

dichotomy has provided a practical conceptual framework for

describing pro-inflammatory vs. anti-inflammatory microglial

responses following ICH, it has become increasingly clear that this

binary model oversimplifies the diversity of microglial states

in vivo. Following ICH onset, pro-inflammatory

microglia-derived mediators often overwhelm the reparative capacity

of anti-inflammatory microglia (20). Thus, identifying these modulators

and influencing factors is essential for promoting microglial

polarization toward neuroprotective subclasses, offering novel

insights into alleviating post-ICH microglial pathology. Based on

the aforementioned analyses of microglial polarization in ICH and

investigations into surface markers of microglial subtypes,

shifting microglia from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory

state represents a critical strategy to improve outcomes after SBI

(Fig. 1).

By integrating the microglial response in ICH within

a dynamic continuum framework, the present review offers distinct

added value over traditional classification perspectives. First,

this framework can reconcile and unify seemingly contradictory

findings in the literature. For example, the differential

expression of the same marker in the injury core vs. remote

regions, or at different time points, can be interpreted as

positional shifts of the same cell population along the state

continuum. Second, it emphasizes the critical importance of

spatiotemporal dimensions by explicitly linking microglial states

to proximity to the hematoma and specific disease stages. This

directly suggests the existence of key time windows and spatial

targets for therapeutic intervention. Finally, this paradigm points

to new directions for future research: Encouraging the use of

spatial transcriptomics to map the whole-brain landscape of

microglial states post-ICH; employing single-cell multi-omics to

identify key regulatory nodes driving state transitions; and

ultimately designing next-generation smart therapies aimed at

dynamically steering microglia toward beneficial functional states,

rather than simply suppressing or activating them. Therefore,

adopting a dynamic continuum perspective not only more accurately

reflects the biological reality but also serves as a conceptual

prerequisite for advancing ICH immunotherapy from broad

interventions toward precise modulation.

Microglia do not act in isolation but orchestrate a

complex multicellular network with astrocytes, infiltrating immune

cells and endothelial cells. This crosstalk constitutes a critical

amplification loop of SBI and a potential therapeutic target after

ICH.

Activated microglia and astrocytes form a

bidirectional regulatory loop to modulate neuroinflammation and

glial scar formation. Astrocytes promote an anti-inflammatory

milieu by secreting costimulatory molecules such as CD200 and

interacting with microglia to activate anti-inflammatory cytokines

(90). In preclinical models,

C5aR1 on microglia integrates local and peripheral C5a signals,

triggering a cascade of neuroinflammation amplification, neurotoxic

astrocyte polarization and neutrophil recruitment that culminates

in cerebral edema (51). In ICH,

the C3-C3aR signaling axis, formed by astrocytic C3 and microglial

C3aR, mediates the inhibitory effect of A1 astrocytes on the

phagocytosis of myelin debris (91). The release of IL-15 from

astrocytes triggers a shift in microglia toward a pro-inflammatory

phenotype, creating a feedback loop that exacerbates

neuroinflammation following ICH (92). TRPA1 in astrocytes regulates

neuroinflammation and neurological deficits post-ICH, by

suppressing the MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway, driving a shift

toward the neuroprotective A2 astrocytic phenotype and enhancing

the proliferation of phagocytic microglia (93). Bidirectional regulation between

microglia and astrocytes serves as a key mechanism modulating the

inflammatory response after ICH, primarily through influencing

cytokine profiles and cellular phenotypic transitions. The

crosstalk between microglia and astrocytes represents a focal point

and cutting-edge area in immunology research, with their

bidirectional modulation of phenotypic and functional states

warranting particular attention in the field of ICH.

Microglia serve as a bridge linking central and

peripheral immunity after ICH. IL-10 modulates both microglial

phagocytic function and the infiltration of monocyte-derived

macrophages following ICH, with CD36 serving as a key phagocytic

effector downstream of IL-10 signaling (94). Activin-A, derived from M2

microglia/macrophages, plays a crucial role in promoting

oligodendrocyte differentiation and thereby fostering myelin

regeneration, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target

for white matter injury following cerebral hemorrhage (95). In PHE, crosstalk between

microglia-derived osteopontin and CD44-positive cells plays a

critical role in regulating the local immune milieu, thereby

influencing the pathological progression (96). Extracellular vesicles secreted by

bone marrow-derived macrophages have the potential to boost

microglial phagocytosis in the aftermath of ICH (97). Microglia act as an immune bridge,

regulating phagocytic function and repair processes through

specific molecules and responding to external signals such as

extracellular vesicles. However, current findings largely remain as

isolated mechanisms, and the mechanisms by which they integrate

into a coordinated spatiotemporal network within the dynamically

evolving ICH milieu remains unclear.

The communication between microglia and endothelial

cells constitutes a critical axis within the neurovascular unit,

fundamentally influencing the pathophysiology of ICH. This

bidirectional crosstalk regulates central processes including BBB

integrity, neuroinflammation and vascular repair, making it a

pivotal focus for therapeutic intervention. Their functional

interplay is facilitated by spatial proximity and involves both

contact-dependent and soluble mediators. Activated microglia can

directly influence BBB permeability through the release of

inflammatory factors and proteases interacting with endothelial

cells (67). In the context of

ICH, endothelial cells lining the choroid plexus are prone to

pyroptosis at the 24-h time point (98). ICH-induced pyroptosis in

endothelial cells is accompanied by the release of pro-inflammatory

cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β, which engage with microglia to activate

the NF-κB signaling pathway and ultimately lead to increased

transcriptional expression of Lcn2 and Msr1 (98). This initiates a cycle of

endothelial damage activating microglia, whose response further

exacerbates vascular dysfunction and inflammation. Hence,

therapeutic strategies aimed at the microglia-endothelial axis,

such as inhibiting key inflammatory pathways or protecting

endothelial health, offer a promising avenue to alleviate SBI

post-ICH.

Microglia play a dual role as both drivers of

secondary injury and promoters of repair, which presents both

challenges and opportunities for the treatment of ICH. This dual

role not only poses complex challenges for the treatment of ICH but

also identifies novel opportunities to achieve neuroprotection by

modulating microglial functions. At present, although numerous

molecular targets have been proven to regulate microglial

functions, translating such findings from preclinical models to

successful clinical applications faces a core issue: The need to

shift from merely enumerating discrete mechanisms to prioritizing

the development of therapeutic strategies based on translational

feasibility, target specificity and their integration into the

dynamic pathophysiology of ICH.

The pro-damaging properties of microglia have been

widely validated. Soluble epoxide hydrolase expression is

upregulated in microglia following ICH and potently drives

neuroinflammatory responses, whereas its inhibition suppresses

microglia-mediated inflammation (99). Additionally, deficiency of

TWIK-related K+ channel 1 exacerbates microglial and

neutrophil recruitment and pro-inflammatory factor production in

ICH-induced SBI (100).

Furthermore, microglia-expressed integrin Mac-1, acting in

conjunction with the endocytic receptor LRP1 in the neurovascular

unit, promotes thrombolytic tissue plasminogen activator

(tPA)-induced activation of platelet-derived growth factor-cc,

thereby increasing BBB permeability in ischemic stroke (56). These studies collectively

indicate that targeting the pro-inflammatory pathways of microglia

represents a viable therapeutic direction for alleviating

early-stage injury.

The anti-inflammatory and reparative potential of

microglia is equally prominent. The crosstalk between regulatory T

lymphocytes and microglial neuroinflammation has been well

documented. Studies have shown that regulatory T lymphocytes

relieve ICH-induced neuroinflammation by enhancing a phenotypic

shift from M1 to M2 microglia via modulation of the

IL-10/GSK3β/PTEN signaling pathway (101-103). This Treg-mediated

immunomodulation highlights the therapeutic potential of harnessing

microglial plasticity to drive neurorepair following ICH. However,

both Treg-based and M2-polarization strategies face notable

translational hurdles in clinical translation, including the lack

of robust, non-invasive biomarkers of microglial phenotype in

humans, the potential risk of systemic immunosuppression and

substantial uncertainty regarding the optimal intervention timing.

Simple functional inhibition or promotion may be insufficient to

address the spatiotemporal complexity of microglial dynamics

following ICH. Therefore, future development of therapeutic

strategies must undergo a fundamental shift in logic. It is

hypothesized that prioritizing and integrating intrinsic regulatory

targets that possess relative microglia selectivity, high

druggability and well-defined therapeutic time windows. This

approach should aim to develop precision interventions capable of

adapting to the pathological progression of ICH, rather than merely

describing isolated mechanisms.

Following ICH, the anti-inflammatory functions of

microglia are mediated by diverse signaling axes that form complex

networks intertwined with multiple biological processes.

Elucidating these signaling pathways and their molecular

foundations is critical for identifying promising therapeutic

targets to mitigate neuropathological deficits in ICH. Among them,

targeting intrinsic regulatory axes is particularly promising. This

approach directly modulates the cell-autonomous mechanisms of

microglia, including phagocytosis, polarization and inflammatory

signaling, by acting on their intrinsic signaling pathways. Due to

this cell-specific mode of action, it offers high target

specificity with a potentially favorable systemic side-effect

profile, representing the most promising direction for current

clinical translation efforts in post-ICH neuroinflammation.

Studies have demonstrated that

rosiglitazone-mediated activation of PPAR-γ protects against BBB

damage and ameliorates hemorrhage transformation, potentially by

promoting anti-inflammatory polarization of microglia (104,105). Phagocytosis is critical for

enhancing hematoma resolution, promoting healing after ICH injury.

Zhao et al (106) found

that PPAR-γ activators significantly upregulated PPAR-γ-regulated

genes such as CD36 catalase, while downregulating pro-inflammatory

genes and alleviating neuronal injury by enhancing microglial

phagocytosis, whereas PPAR-γ gene knockdown or anti-CD36 antibody

treatment significantly impaired this phagocytic function following

ICH. PPAR-γ activation also enhances the phagocytic capacity of

anti-inflammatory microglia via CD36 (52). Building on preclinical research,

PPAR-γ activators have entered clinical applications.

Simvastatin-activated PPAR-γ improves microglia-induced erythrocyte

phagocytosis and exhibits neuroprotective effects in patients with

ICH (107,108). These findings highlight PPAR-γ

as a pivotal regulator of microglial phagocytosis and inflammation,

with therapeutic activators offering promise for clinical

translation in ICH.

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

(AMPK) regulates the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory

microglial subclasses by acting as a central sensor of brain injury

(109,110). Adiponectin receptor 1

(AdipoR1), constitutively expressed in microglia, is activated by

endogenous C1q/TNF-related protein 9 (CTRP9), which exhibits

increased expression within the first 24 h after ICH. CTRP9

treatment upregulates AdipoR1 and phosphorylated (p-) AMPK protein

levels while reducing inflammatory cytokines, thereby decreasing

neuroinflammation by modulating the AdipoR1/AMPK/NF-κB signaling

pathway (111). Following ICH,

CTRP9-activated AdipoR1 further mitigates neuropathological damage

and BBB dysfunction by engaging APPL1/AMPK/Nrf2 signaling,

highlighting CTRP9 as a promising therapeutic agent for improving

BBB integrity (112,113). Similarly, activation of

melanocortin receptor 4 alleviates neuropathological deficits by

regulating the AMPK signaling pathway (114). Future research should focus on

developing brain-specific AMPK activators to enhance translational

feasibility.

Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β)

confers neuroprotective effects in in vivo experiments

(115-117). By enhancing microglial

phagocytosis and promoting M2-phenotype microglial differentiation,

GSK-3β inhibition significantly improves hematoma resolution and

cognitive deficits in rats with ICH (118,119). Additionally, lithium chloride

treatment downregulated GSK-3β activity, reducing mature

oligodendrocytes death and upregulating brain-derived neurotrophic

factor expression (120). Thus,

GSK-3β is classified as a medium-priority target, requiring

time-window stratified studies and dose-optimization research to

confirm its clinical applicability.

As aforementioned, regulatory T lymphocytes suppress

the microglia-induced inflammatory response and improve

neurological deficits by inhibiting NF-κB activation via the

JNK/ERK pathway (38,101,121). Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has

been shown to reduce the expression levels of pro-inflammatory

cytokines and p-JNK, proposing a link between JNK signaling and

downregulation of M1 microglial immune activity (122,123). Current clinical management of

ICH faces notable limitations, including concerns about treatment

efficacy, surgical trauma, complications and drug side effects,

with few standardized interventions available. Hyperbaric oxygen

therapy (HOT) emerges as a promising alternative approach, although

the specific mechanisms by which HOT modulates ICH pathophysiology

require further investigation and validation. These findings

highlight the need to explore non-pharmacological, pathway-targeted

strategies such as HOT to address unmet clinical needs in ICH

treatment.

Intrinsic regulatory targets with high druggability

and existing clinical repurposing potential should be prioritized

for subsequent translational studies. AMPK and GSK-3β, while

mechanistically promising, require specificity enhancement and

clinical feasibility validation to advance toward clinical

application.

Intercepting detrimental extracellular signals

targeting microglial pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) is a key

upstream intervention strategy. This approach aims to block the

initial 'trigger' of microglial activation, thereby inhibiting

downstream inflammatory cascades. However, PRRs are often widely

expressed in myeloid cells, leading to potential systemic immune

suppression, which poses a major translational issue for this class

of targets.

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a central player in

innate immune responses, has been recognized as a key pattern

recognition receptor (124).

TLR4 deficiency attenuated perihematomal inflammation by reducing

the infiltration of pro-inflammatory microglia in in vivo

ICH experiments (125,126). By contrast, TLR4 activation

impairs microglial phagocytosis of erythrocytes, delaying

CD36-mediated hematoma resolution and exacerbating neurological

deficits in ICH (127,128). Additionally, TLR4-driven

microglial autophagy has been linked to exacerbated

neuroinflammation in ICH mouse models (129). Collectively, these studies

highlight the dual role of TLR4 in modulating both inflammatory

recruitment and hematoma clearance after ICH. Targeting TLR4

signaling represents a promising therapeutic strategy to balance

anti-inflammatory effects with enhanced phagocytic function,

positioning it as a potential candidate for future ICH

interventions.

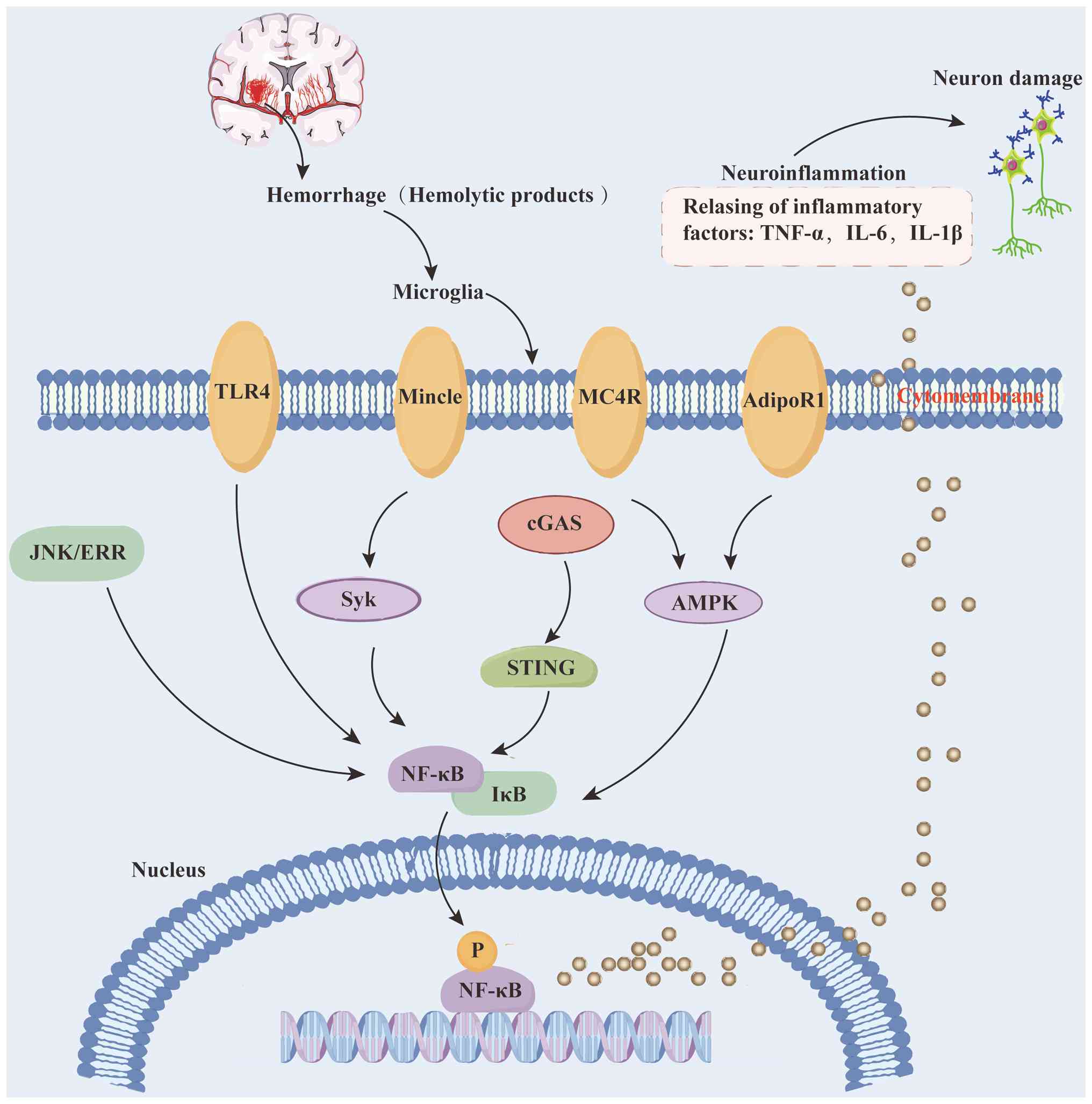

DNA damage initiates the innate immune response,

with cGAS, a key DNA sensor, detecting disease-associated damaged

DNA to activate its downstream effector, STING. This cascade

results in the upregulation of type I interferon production and

phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (130). cGAS acts as a critical

regulator of inflammation and autophagy, with upregulated cGAS in

striatal brain damage mediating inflammation via increased

expression of pro-inflammatory genes (Ccl5 and Cxcl10) and

activating autophagy through the major initiators LC3A and LC3B

(131). In ischemic stroke

models, tPA therapy enhances neutrophil extracellular trap

expression in plasma and brain tissue. DNase I treatment or

peptidyl-arginine deiminase 4 deficiency, both of which inhibit

neutrophil extracellular trap formation, reverse tPA-induced cGAS

upregulation. By contrast, in tPA-treated mice, cGAMP (a

cGAS-derived second messenger) suppresses DNase I-induced

anti-hemorrhagic effects by dampening STING and type I interferon

signaling (132). Jiang et

al (133) further

demonstrated that cGAS knockdown furthers M2 microglial

polarization and attenuates the inflammatory response by disrupting

the cGAS-STING axis in stroke mice. Shi et al (134) extended these findings,

demonstrating that a cGAS inhibitor delivered via immunosuppressive

nanoparticles reduces microglial inflammation and enhances

anti-inflammatory polarization in post-stroke rats. IronQ

pretreatment confers mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with a

synergistic effect to alleviate neuroinflammation and improve

neurological function, achieved by inhibiting the cGAS-STING

signaling pathway (135).

C-type lectin-like receptors, a family of

transmembrane PRRs predominantly expressed in myeloid cells, play a

critical role in innate immunity (136). Dysregulation of C-type

lectin-like receptors following tissue injury can drive excessive

production of inflammatory mediators and exacerbate inflammatory

progression. Among C-type lectin-like receptors, microglial

macrophage-inducible C-type lectin (Mincle), widely expressed on

macrophages, binds nuclear spliceosome-associated protein 130

released from necrotic cells, potently enhancing the inflammatory

response (137,138). In alcohol-induced liver injury

models, Mincle activation via its downstream effector spleen

tyrosine kinase (Syk) upregulates the expression levels of

pro-inflammatory genes (139),

while in Crohn's disease, the Mincle/Syk axis exacerbates

intestinal mucosal inflammation through macrophage pyroptosis

(140). Inhibiting this pathway

attenuates inflammatory responses, highlighting its therapeutic

potential. Preclinical studies across multiple neurological

disorders have demonstrated that blocking the Mincle/Syk signaling

axis confers neuroprotection (141). For example, interventions

including the Syk inhibitor BAY61-3606, acupuncture and MSC

transplantation suppress Mincle/Syk-mediated microglial activation,

reducing neuroinflammation in in vivo stroke models

(138,141-145). Collectively, these findings

establish the Mincle/Syk pathway as a promising therapeutic target

for ICH, offering a rationale for developing novel immunomodulatory

strategies to mitigate post-ICH neuroinflammation and promote

neurological recovery.

To date, autophagy exhibits dualistic functions,

making it challenging to assess whether its effects after ICH are

predominantly harmful or beneficial. Excessive autophagy

exacerbates endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS)-induced brain injury

as early as 6 h following ICH. By contrast, at day 7 post-ICH in

rats, autophagy strengthens ERS protective functions by clearing

cellular debris (146). Tan

et al (147)

demonstrated that enhanced autophagy attenuates oxidative stress

injury following ICH by upregulating antioxidant protein

expression, while autophagy inhibitors reverse this neuroprotective

effect. Previous studies further indicate that autophagy positively

regulates the inflammatory response in the context of ICH (148,149).

The levels of ILs during ICH progression are

modulated by microglial functions. Xu et al (150) demonstrated that IL-4-loaded

nanoparticles activating the IL-4/STAT6 axis promoted hematoma

resolution and functional recovery in mice with ICH. By contrast,

IL-15, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, regulates homeostasis and

microglial immunoreactivity following CNS inflammatory events

(92). Yu et al (151) showed that an

IL-17A-neutralizing antibody attenuates microglial activation and

blocks ICH-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokines. Shi et al

(152) further revealed that

IL-17A enhances microglial autophagy and neuroinflammation.

Administration of an IL-17A-neutralizing antibody significantly

reduced brain edema and improved neurological outcomes in mice with

ICH, while genetic inhibition of autophagy-related genes ATG5 and

ATG7 suppressed microglial autophagy and inflammation (153). Intraventricular injection of

IL-33 alleviated white matter and neuronal injury by promoting

microglial M2 polarization following ICH (154). Additionally, inhibiting the

NF-κB signaling pathway through diverse interventions, including

microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs), GATA-binding protein 4 and traditional

Chinese medicines, can reduce neuroinflammation in ICH therapy

(155-159). These findings highlight the

bidirectional role of ILs and NF-κB in regulating microglial

phenotypes and underscore their therapeutic potential in modulating

neuroinflammation after ICH.

Intercepting extracellular signals via PRRs

represents a rational upstream therapeutic strategy, yet its

translational potential is constrained by insufficient target

specificity and limited validation in ICH-specific models.

Therefore, future research should focus on developing

microglia-specific PRR modulators and conduct in-depth validation

in clinically relevant ICH models. In summary, although extensive

preclinical studies have made notable progress at the mechanistic

level, successfully translating these findings into clinical

applications requires further systematic investigation of promising

interventions (Fig. 2).

Exosomes and miRNAs represent emerging precision

therapeutic tools for modulating microglia after ICH, offering

advantages such as low immunogenicity, high target specificity and

the ability to regulate multiple pathways simultaneously, thereby

effectively addressing the spatiotemporal complexity of microglial

dynamics post-ICH. To translate these promising tools into precise

therapies, a rational framework is required. This involves

identifying key molecular targets within microglial dynamic

continuum, categorizing them based on their pathological function,

and employing engineered exosomes for spatiotemporally controlled

delivery. Current evidence points to three strategic categories of

targets: (i) Inflammatory initiators (for example, TLR4), the

suppression of which quenches upstream danger signaling; (ii)

polarization nodes (for example, CKIP-1 and C/EBP-α), the

modulation of which actively reprogrammes microglia toward a

reparative phenotype; and (iii) Cellular stress regulators (for

example, mTOR), the intervention of which maintains microglial

homeostasis. The convergence of exosome biology and miRNA

targetology offers a unique path to address these targets in a

combined and specific manner.

Given their minimal risks of immunogenicity and

tumorigenicity, exosomes secreted by human umbilical cord

mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSC-exo) represent a promising

alternative to cell-based therapies. Evidence indicates that

hUCMSC-exo administration can alleviate astrocyte inflammation and

mitochondrial damage associated with ICH by inhibiting the

TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway (160). Exosomal PTEN-induced kinase 1

from hUCMSCs attenuates neurological deficits, dysregulated

microglial M1/M2 polarization and inflammatory responses after ICH

in mice (161). Exosomes

derived from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells

(hADSCs-Exo) were successfully internalized by microglia cells and

exerted robust anti-inflammatory actions by suppressing the exerted

robust anti-inflammatory actions of inflammatory factors and

promoting M1 to M2 transition (162). Exosomes, which are nanoscale

vesicles measuring 30-150 nm in diameter, encapsulate a diverse

cargo encompassing mRNA, miRNA, proteins and growth factors

(163,164). Beyond serving as delivery

vehicles, the specific contents of exosomes, especially miRNAs, are

pivotal for their immunomodulatory effects. Consequently,

identifying key miRNAs and elucidating their mechanisms in

microglial polarization has become a major research frontier in

developing RNA-based therapeutics for ICH.

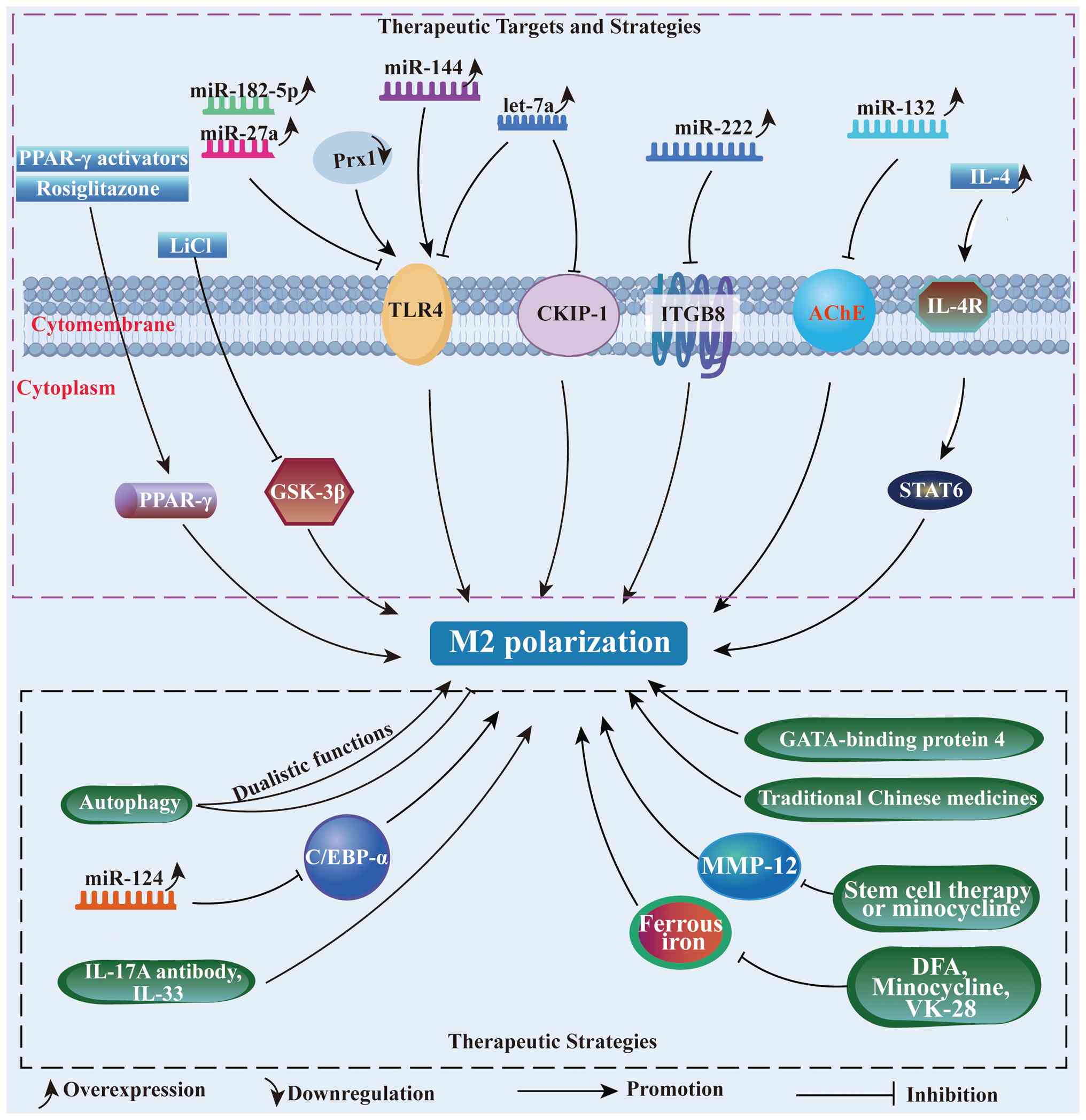

Increasing genetic and epigenetic evidence

highlights the critical role of miRNAs in modulating gene

expression and microglial polarization following ICH (165). For example, let-7a modulates

microglial M2 polarization by targeting CKIP-1 at day 3 post-ICH in

mice. In the aforementioned study, let-7a overexpression reduced

CKIP-1 protein levels, promoted M2 polarization characterized by

increased expression of IL-10 and Arg-1, and alleviated

neuroinflammation. By contrast, let-7a inhibition upregulated

CKIP-1, driving M1 polarization (165). Similarly, miR-7 overexpression

suppresses TLR4 protein expression, attenuating microglial

inflammation in both ICH rats and lipoprotein-stimulated microglial

inflammation models (166).

Further research has demonstrated that targeting TLR4 through the

inhibition of the Prx1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling axis at day 3 post-ICH

provides neuroprotection against ICH-induced brain injury,

presenting a promising anti-neuroinflammatory strategy (155). In stroke in vivo and

in vitro experiments, miR-182-5p and miR-27a modulate

inflammation by targeting TLR4, and their overexpression

downregulates TLR4 protein levels while reducing the release of

pro-inflammatory factors (167,168).

Previous evidence identified that integrin subunit

β8, a direct target of miR-222, can be negatively regulated by

miR-222 to alleviate microglial inflammation and apoptosis

(169). Previously, miR-132 was

shown to inhibit the cholinergic inflammatory response by targeting

acetylcholinesterase. Zhang et al (170) reported that lentivirus-mediated

miR-132 overexpression in the right caudate nucleus 14 days before

autologous blood-induced ICH suppressed pro-inflammatory microglial

activation, alleviated BBB dysfunction and reduced neuronal

reduction at day 3 post-ICH. miRNAs also act as key mediators of

autophagy-induced microglial inflammation, post-transcriptionally

suppressing gene expression and function (171). It has been demonstrated that

miR-144 enhances hemoglobin-mediated microglial autophagic

inflammation by directly targeting the 3' untranslated regions

(UTRs) of mTOR (171,172). Similarly, miR-124 promotes

microglial M2 polarization and alleviates inflammation by targeting

the 3'-UTR of C/EBP-α. In ICH mice, miR-124 mimic administration

significantly reduced neurological deficits, brain water content

(BWC) and C/EBP-α expression at day 3, compared with miR-124

inhibitor treatment. Consistent negative regulation of C/EBP-α by

miR-124 was also observed in erythrocyte lysate-stimulated

microglia transduced with miR-124 mimics or inhibitors (173).

Exosomes and miRNAs represent more than just a list

of promising entities; they form the core of an emerging precision

immunomodulation paradigm for ICH. Moving beyond the generic

suppression of neuroinflammation, this paradigm is defined by the

rational selection of targets across the microglial functional

spectrum (for example, TLR4, CKIP-1 and mTOR) and their precise

manipulation via engineered exosomes loaded with specific miRNA

combinations. The primary translational challenge no longer lies

solely in target identification, but in optimizing these

intelligent delivery systems to ensure their stability, targeting

efficiency, and controlled cargo release, and in validating their

synergistic efficacy in advanced disease models. This approach

heralds a shift from broad anti-inflammatory strategies toward

context-sensitive immune remodeling tailored to the spatiotemporal

dynamics of ICH.

Modulating downstream effector molecules targets

the terminal pathological processes of microglial activation,

aiming to block the final 'damage cascade' rather than regulating

microglial function directly. This strategy is characterized by

clear mechanisms of action but may lack specificity due to the

widespread involvement of effector molecules in normal

physiological processes.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a universal

superfamily of structurally related zinc-dependent endopeptidases,

are upregulated following ICH and contribute to extracellular

matrix degradation. The role of MMPs in ECM disruption driven by

inflammation serves as a pathological basis for stroke, as

evidenced in numerous studies (174). Wells et al (175) investigated MMP function in ICH

mice and found that MMP-12 was the most significantly elevated

isoform, with experiments revealing that MMP-12 knockout mice

exhibited substantial forelimb motor recovery compared with WT

mice, while WT mice showed increased recruitment of

Iba1+ cells with macrophage morphology to the injury

site, indicating that MMP-12 exacerbates SBI after ICH (175). Subsequent studies demonstrated

that stem cell therapy or minocycline administration following ICH

reduced perihematomal MMP-12 expression and attenuated

microglia-infiltrated inflammatory responses (176,177), positioning MMP-induced

microglial activation as a potential therapeutic target. For

example, minocycline promotes the microglial phenotypic shift from

pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 (178). However, while minocycline

therapy effectively mitigates the early elevation of MMP-12 and

TNF-α, its therapeutic efficacy diminishes by 1-week post-ICH.

Additional studies have revealed that stem cell therapy notably

reduces microglial infiltration and MMP-12 expression in

perihematomal regions after ICH (177,179).

Increasing evidence indicates that ferrous iron

released from hemolysis represents a key pathogenic factor in

hematoma following ICH (180).

Iron toxicity-mediated microglial activation and pro-inflammatory

response are major contributors to brain injury after ICH.

Deferoxamine, an iron chelator capable of crossing the BBB to bind

iron, has been identified to moderately modulate microglial

activation following ICH when administered intraperitoneally to

decrease iron accumulation (181-183). As a microglial activation

inhibitor, minocycline can also reduce iron levels to prevent

neuronal death after ICH (184,185). Similarly, VK-28, a

brain-permeable iron chelator, promotes microglial M2 phenotype

polarization, reduces BWC, alleviates white matter injury and

improves neurobehavioral deficits after ICH (186,187). Observational studies highlight

the complexity of regulatory systems governing microglial function,

underscoring the critical need to decipher phenotypic and genotypic

variations to develop promising therapeutic strategies for ICH.

Modulating downstream effector molecules offers

mechanism-specific intervention for post-ICH injury. Iron chelation

is a high-priority strategy due to its ICH-specific mechanisms and

existing clinical drug availability, while MMP-12 is limited by

narrow intervention windows and poor specificity. For downstream

targets, defining precise intervention timelines (aligned with

pathological progression) is critical for balancing therapeutic

efficacy and safety. Therefore, advancing these downstream

strategies into the clinic critically depends on translational

research that rigorously defines their optimal therapeutic windows

in complex, time-course models (Fig.

3).

The core academic contribution of this review lies

in the establishment of an innovative conceptual framework for the

hierarchical targeted regulation of microglial neuroinflammation,

which systematically categorizes regulatory strategies into four

dimensions: Targeting the intrinsic regulatory axes of microglia,

intercepting detrimental extracellular signals, implementing

precise interventions with exosomes and miRNAs, and regulating

downstream effector molecules, thus achieving a logical upgrade

from mechanistic description to translation-oriented research. Its

unique research perspective is reflected in taking translational

feasibility, targeting specificity and pathological dynamic

adaptability as the core criteria to clarify the regulatory

priority and clinical translational potential of each signaling

axis; it combines with the time dependence of pathological

progression in ICH to distinguish the intervention windows and

applicable scenarios of different regulatory strategies, and

meanwhile focuses on the key challenges in translational medicine

to analyze the clinical translational bottlenecks and optimization

directions of various strategies. In summary, the present review

systematically integrates the latest regulatory mechanisms of

microglial neuroinflammation following ICH.

ICH is distinguished by the concurrent presence of

hyperdense and hypodense areas within a single hematoma, resulting

in a 'blended' appearance, with hyperdense areas typically

indicative of more coagulated or organized clots and hypodense

areas often signifying relatively newly extravasated, incompletely

coagulated blood (188,189). The upregulation of MAPT, CYCS,

GAP43 and MAP1B, coupled with the enrichment of ferroptotic,

mitochondrial dysfunction-related, oxidative stress-associated,

inflammatory and cytoskeletal pathways, suggests that the intricate

biological processes occurring within hematomas (190). While this association

establishes a theoretical bridge between radiology and molecular

biology, direct causal evidence verifying the mechanisms by which

these genetic and pathway alterations drive the formation of

hyperdense-hypodense regions remains scarce.

In terms of diagnostic and discriminative value,

multiple molecular biomarkers exhibit promising performance in ICH

management. Serum levels of matrix MMP-9, VEGF, GFAP and S100

calcium-binding protein B are significantly higher in patients with

ICH, and the serum levels of these molecular biomarkers are

correlated with a larger volume of PHE. The biomarkers GFAP, MMP-9

and APO-C1 independently discriminated between ischemic stroke and

ICH within 24 h and markedly boosted the discriminative capacity of

predictive models (191). The

cerebral blood flow-based neurological score serves as an

independent predictor of post-treatment ICH risk in adult patients

with moyamoya disease (192).

Despite these encouraging results, the specificity of these

biomarkers remains incompletely validated. Notably, key

inflammatory mediators such as MMP-9 and VEGF are also elevated in

other acute cerebrovascular events and systemic inflammatory

conditions. This overlap may limit their discriminative accuracy,

especially in clinically heterogeneous patient populations.

Furthermore, most supporting evidence originates from single-center

studies with limited sample sizes. Therefore, multicenter,

prospective validation is essential to confirm their true clinical

applicability.

The association between molecular signatures and

ICH prognosis further highlights the translational potential of

these biomarkers. Elevation of inflammatory biomarkers is

associated with adverse outcomes in ICH (193), and serum YKL-40 levels may

serve as a candidate prognostic biomarker for the recurrence of

cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related ICH (194). Moreover, the onset of acute

anemia following ICH is prevalent, rapidly progressive and closely

linked to inflammatory processes (195). Given that anemia development is

associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes, it is proposed as a

potential modifiable target to improve patient prognosis. The

current understanding of anemia as a therapeutic target remains

superficial as most studies only confirm the correlation between

anemia and poor outcomes but lack interventional trials to verify

whether correcting anemia can ameliorate ICH prognosis.

For early diagnosis and prevention, a panel of

novel biomarkers has emerged as complementary tools when computed

tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are either

unavailable or fail to reveal distinct signs of potential vascular

rupture. To facilitate early diagnosis, ICH prevention and predict

patient prognosis following hemorrhagic events, several parameters

can be assessed including: Red cell distribution width, Red cell

distribution width to lymphocyte ratio, resolvin D2 levels,

C-reactive protein to albumin ratio levels, nucleotide-binding

oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing

1 levels, and the precise and reliable assessment of circulating

miRNAs, long non-coding RNA, circular RNA and mRNA expression in

biological fluids (196-202).

Furthermore, an in-depth investigation into differentially

expressed inflammatory proteins, serum secretoneurin, and levels of

soluble TLR4 and TLR2 in the early stage of ICH will facilitate an

improved understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying ICH,

enable more accurate prediction of patient prognosis and facilitate

the exploration of novel therapeutic strategies (198,203-205). A major difficulty in

translating these biomarkers to clinical practice is the lack of

standardized detection protocols, as different laboratories adopt

varying assay methods, leading to inconsistent results that hinder

cross-study comparison. Additionally, the optimal combination of

these biomarkers for multi-marker diagnosis has not been

systematically determined, and cost-effectiveness analysis is

needed to evaluate their feasibility in resource-limited clinical

settings.

Emerging evidence indicates that pro-inflammatory

and anti-inflammatory microglial phenotypes exhibit divergent

functions and implications, offering mechanistic insights into

microglial regulation through intracellular and extracellular

signaling pathways. Post-ICH brain injury and repair are not driven

by isolated cellular responses, but are orchestrated by a highly

dynamic, microglia-centered neuroimmune network. The functional

regulation of microglia after ICH is a central therapeutic target

for neuroinflammation. In the present review, a comprehensive

overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms governing

microglial activation after ICH was provided. Substantial progress

has been made in identifying signaling molecular pathways linked to

SBI following ICH in preclinical studies. PPAR-γ agonists,

microglia-targeted exosomes and TLR4-specific inhibitors may

represent the most promising directions in terms of current

translational potential. However, extended clinical trials are

essential for further validation.

The present review had several critical challenges

which must be addressed. First, although animal models are widely

used to investigate ICH etiology and pathophysiology, current

models, predominantly rodent-based, do not fully recapitulate the

complex etiology of human spontaneous ICH. Rodents exhibit robust

spontaneous sensorimotor recovery and limited cognitive

dysfunction, failing to reflect multifaceted clinical risk factors

(such as hypertension and anticoagulant use). Second, experimental

models do not fully replicate the pathological complexity of human

ICH. To address this, preclinical research increasingly employs

large animal models and advanced 3.0T MRI techniques to

characterize key parameters such as hematoma expansion, white

matter injury and hematoma evacuation, enabling cross-species

comparisons with human disease. Third, most studies on ICH-induced

brain injury focus on single-factor interventions. Future research

should prioritize developing multi-targeted agents or combinatorial

therapies to address the interconnected pathways driving

neuroinflammation and tissue damage. While the current landscape of

robust clinical trials remains limited and molecular genetic

investigations into microglial phenotypic transitions are lacking,

the present review offers an optimistic perspective on practical

intervention strategies targeting microglial function in ICH.

Further research into therapeutic strategies addressing microglial

activation-driven neuroinflammation is critical for evaluating the

translational potential of these promising approaches.

Not applicable.

GY, GC and XB conceptualized the study. XF, CP, LZ

and OW wrote and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. DL

and BZ wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. GY and XF

prepared figures. XF, GY and XB acquired funding. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by The National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82200361), the Sichuan Science and

Technology Program (grant no. 2025NSFSC2140), the Health Commission

of Sichuan Province Medical Science and Technology Program (grant

no. 24QNMP012), the Brain Disease Innovation Team of the Affiliated

Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Southwest Medical

University (grant no. 2022-CXTD-05), the Luzhou Science and

Technology Program (grant no. 2025LZXNYDJC53), the Xuyong People's

Hospital-Southwest Medical University Strategic Cooperation in

Science and Technology (grant no. 2025XYXNYD13) and the Southwest

Medical University Technology Program (grant no. 2024ZXYZX14).

|

1

|

Keep RF, Hua Y and Xi G: Intracerebral

haemorrhage: Mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet

Neurol. 11:720–731. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Schrag M and Kirshner H: Management of

intracerebral hemorrhage: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol.

75:1819–1831. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rajashekar D and Liang JW: Intracerebral

Hemorrhage. StatPearls; Treasure Island, FL: 2021

|

|

4

|

Jain A, Malhotra A and Payabvash S:

Imaging of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuroimaging Clin

N Am. 31:193–203. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Witsch J, Siegerink B, Nolte CH, Sprügel

M, Steiner T, Endres M and Huttner HB: Prognostication after

intracerebral hemorrhage: A review. Neurol Res Pract. 3:222021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Biffi A, Anderson CD, Battey TW, Ayres AM,

Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A and Rosand J: Association between blood

pressure control and risk of recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage.

JAMA. 314:904–912. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bosche B, Mergenthaler P, Doeppner TR,

Hescheler J and Molcanyi M: Complex clearance mechanisms after

intraventricular hemorrhage and rt-PA treatment-a review on

clinical trials. Transl Stroke Res. 11:337–344. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wu S and Anderson CS: A need to re-focus

efforts to improve long-term prognosis after stroke in China.

Lancet Glob Health. 8:e468–e469. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der

Tweel I, Algra A and Klijn CJ: Incidence, case fatality, and

functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time,

according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 9:167–176. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Carpenter AM, Singh IP, Gandhi CD and

Prestigiacomo CJ: Genetic risk factors for spontaneous

intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol. 12:40–49. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wu S, Wu B, Liu M, Chen Z, Wang W,

Anderson CS, Sandercock P, Wang Y, Huang Y, Cui L, et al: Stroke in

China: Advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and

management. Lancet Neurol. 18:394–405. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Alharbi BM, Tso MK and Macdonald RL:

Animal models of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Res.

38:448–455. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen-Roetling J, Li Y, Cao Y, Yan Z, Lu X

and Regan RF: Effect of hemopexin treatment on outcome after

intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Brain Res. 1765:1475072021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bentz K, Molcanyi M, Schneider A, Riess P,

Maegele M, Bosche B, Hampl JA, Hescheler J, Patz S and Schäfer U:

Extract derived from rat brains in the acute phase following

traumatic brain injury impairs survival of undifferentiated stem

cells and induces rapid differentiation of surviving cells. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 26:821–830. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Xiong XY, Wang J, Qian ZM and Yang QW:

Iron and intracerebral hemorrhage: From mechanism to translation.

Transl Stroke Res. 5:429–441. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ziai WC: Hematology and inflammatory

signaling of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 44(Suppl 1):

S74–S78. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chiang PT, Tsai LK and Tsai HH: New

targets in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Curr Opin Neurol.

38:10–17. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

18

|

Chen S, Yang Q, Chen G and Zhang JH: An

update on inflammation in the acute phase of intracerebral

hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 6:4–8. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liu J, Zhu Z and Leung GK:

Erythrophagocytosis by microglia/macrophage in intracerebral

hemorrhage: From mechanisms to translation. Front Cell Neurosci.

16:8186022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bai Q, Xue M and Yong VW: Microglia and

macrophage phenotypes in intracerebral haemorrhage injury:

Therapeutic opportunities. Brain. 143:1297–1314. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Eldahshan W, Fagan SC and Ergul A:

Inflammation within the neurovascular unit: Focus on microglia for

stroke injury and recovery. Pharmacol Res. 147:1043492019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bian Z, Gong Y, Huang T, Lee CZW, Bian L,

Bai Z, Shi H, Zeng Y, Liu C, He J, et al: Deciphering human

macrophage development at single-cell resolution. Nature.

582:571–576. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Prinz M, Jung S and Priller J: Microglia

biology: One century of evolving concepts. Cell. 179:292–311. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wolf SA, Boddeke HW and Kettenmann H:

Microglia in physiology and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 79:619–643.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Friedman BA, Srinivasan K, Ayalon G,

Meilandt WJ, Lin H, Huntley MA, Cao Y, Lee SH, Haddick PCG, Ngu H,

et al: Diverse brain myeloid expression profiles reveal distinct

microglial activation states and aspects of Alzheimer's disease not

evident in mouse models. Cell Rep. 22:832–847. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang M, Hua Y, Keep RF, Wan S, Novakovic N

and Xi G: Complement inhibition attenuates early erythrolysis in

the hematoma and brain injury in aged rats. Stroke. 50:1859–1868.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Vinukonda G, Liao Y, Hu F, Ivanova L,

Purohit D, Finkel DA, Giri P, Bapatla L, Shah S, Zia MT, et al:

Human cord blood-derived unrestricted somatic stem cell infusion

improves neurobehavioral outcome in a rabbit model of

intraventricular hemorrhage. Stem Cells Transl Med. 8:1157–1169.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chang CF, Wan J, Li Q, Renfroe SC, Heller

NM and Wang J: Alternative activation-skewed microglia/macrophages

promote hematoma resolution in experimental intracerebral

hemorrhage. Neurobiol Dis. 103:54–69. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sekerdag E, Solaroglu I and Gursoy-Ozdemir

Y: Cell death mechanisms in stroke and novel molecular and cellular

treatment options. Curr Neuropharmacol. 16:1396–1415. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jin WN, Shi SX, Li Z, Li M, Wood K,

Gonzales RJ and Liu Q: Depletion of microglia exacerbates

postischemic inflammation and brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow

Metab. 37:2224–2236. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yang X, Ren H, Wood K, Li M, Qiu S, Shi

FD, Ma C and Liu Q: Depletion of microglia augments the

dopaminergic neurotoxicity of MPTP. FASEB J. 32:3336–3345. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Baang HY and Sheth KN: Stroke prevention

after intracerebral hemorrhage: Where are we now? Curr Cardiol Rep.

23:1622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Huang AP, Hsu YH, Wu MS, Tsai HH, Su CY,

Ling TY, Hsu SH and Lai DM: Potential of stem cell therapy in

intracerebral hemorrhage. Mol Biol Rep. 47:4671–4680. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tschoe C, Bushnell CD, Duncan PW,

Alexander-Miller MA and Wolfe SQ: Neuroinflammation after

intracerebral hemorrhage and potential therapeutic targets. J

Stroke. 22:29–46. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Aronowski J and Zhao X: Molecular

pathophysiology of cerebral hemorrhage: Secondary brain injury.

Stroke. 42:1781–1786. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Babu R, Bagley JH, Di C, Friedman AH and

Adamson C: Thrombin and hemin as central factors in the mechanisms

of intracerebral hemorrhage-induced secondary brain injury and as

potential targets for intervention. Neurosurg Focus. 32:E82012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Duan X, Wen Z, Shen H, Shen M and Chen G:

Intracerebral hemorrhage, oxidative stress, and antioxidant

therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016:12032852016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Yang QW and Wang J:

Modulators of microglial activation and polarization after

intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol. 13:420–433. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zheng Y, Tan X and Cao S: The critical

role of erythrolysis and microglia/macrophages in clot resolution

after intracerebral hemorrhage: A review of the mechanisms and

potential therapeutic targets. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 43:59–67. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Mohammed Thangameeran SI, Tsai ST, Hung

HY, Hu WF, Pang CY, Chen SY and Liew HK: A role for endoplasmic

reticulum stress in intracerebral hemorrhage. Cells. 9:7502020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lua J, Ekanayake K, Fangman M and Dore S:

Potential role of soluble toll-like receptors 2 and 4 as

therapeutic agents in stroke and brain hemorrhage. Int J Mol Sci.

22:99772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wei Y, Song X, Gao Y, Gao Y, Li Y and Gu

L: Iron toxicity in intracerebral hemorrhage: Physiopathological

and therapeutic implications. Brain Res Bull. 178:144–154. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wilkinson DA, Pandey AS, Thompson BG, Keep

RF, Hua Y and Xi G: Injury mechanisms in acute intracerebral

hemorrhage. Neuropharmacology. 134:240–248. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Chen Y, Chen S, Chang J, Wei J, Feng M and

Wang R: perihematomal edema after intracerebral hemorrhage: An

update on pathogenesis, risk factors, and therapeutic advances.

Front Immunol. 12:7406322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bautista W, Adelson PD, Bicher N,

Themistocleous M, Tsivgoulis G and Chang JJ: Secondary mechanisms

of injury and viable pathophysiological targets in intracerebral

hemorrhage. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 14:175628642110492082021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Brouwers HB and Greenberg SM: Hematoma

expansion following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc

Dis. 35:195–201. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yin J, Lu TM, Qiu G, Huang RY, Fang M,

Wang YY, Xiao D and Liu XJ: Intracerebral hematoma extends via

perivascular spaces and perineurium. Tohoku J Exp Med. 230:133–139.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Fu X, Zhou G, Zhuang J, Xu C, Zhou H, Peng

Y, Cao Y, Zeng H, Li J, Yan F, et al: White matter injury after

intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 12:5620902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD and Hanley DF:

Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. 373:1632–1644. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chen W, Guo C, Huang S, Jia Z, Wang J,

Zhong J, Ge H, Yuan J, Chen T, Liu X, et al: MitoQ attenuates brain

damage by polarizing microglia towards the M2 phenotype through

inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome after ICH. Pharmacol Res.

161:1051222020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhou J, Ma S, Feng D, Tian Y, Li L, Guo H,

Shi Y, Cui W, Dong J, Hao S, et al: C5aR1(+) microglia exacerbate

neuroinflammation and cerebral edema in acute brain injury. Neuron.

114:444–462.e9. 2026. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Zhao X, Grotta J, Gonzales N and Aronowski

J: Hematoma resolution as a therapeutic target: The role of

microglia/macrophages. Stroke. 40(Suppl 3): S92–S94. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wang G, Wang L, Sun XG and Tang J:

Haematoma scavenging in intracerebral haemorrhage: from mechanisms

to the clinic. J Cell Mol Med. 22:768–777. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

54

|

Deng S, Sherchan P, Jin P, Huang L, Travis

Z, Zhang JH, Gong Y and Tang J: Recombinant CCL17 enhances hematoma

resolution and activation of CCR4/ERK/Nrf2/CD163 signaling pathway

after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Neurotherapeutics.

17:1940–1953. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhuang J, Peng Y, Gu C, Chen H, Lin Z,

Zhou H, Wu X, Li J, Yu X, Cao Y, et al: Wogonin accelerates

hematoma clearance and improves neurological outcome via the PPAR-ү

pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res.

12:660–675. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Su EJ, Cao C, Fredriksson L, Nilsson I,

Stefanitsch C, Stevenson TK, Zhao J, Ragsdale M, Sun YY, Yepes M,

et al: Microglial-mediated PDGF-CC activation increases

cerebrovascular permeability during ischemic stroke. Acta

Neuropathol. 134:585–604. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Fang Y, Gao S, Wang X, Cao Y, Lu J, Chen

S, Lenahan C, Zhang JH, Shao A and Zhang J: Programmed cell deaths

and potential crosstalk with blood-brain barrier dysfunction after

hemorrhagic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 14:682020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Liu P, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Yuan Z, Sun JG,

Xia S, Cao X, Chen J, Zhang CJ, Chen Y, et al: Noncanonical

contribution of microglial transcription factor NR4A1 to

post-stroke recovery through TNF mRNA destabilization. PLoS Biol.

21:e30021992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Carson MJ, Doose JM, Melchior B, Schmid CD

and Ploix CC: CNS immune privilege: Hiding in plain sight. Immunol

Rev. 213:48–65. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Gong Y, Li H, Cui H and Gong Y: Microglial

mechanisms and therapeutic potential in brain injury

post-intracerebral hemorrhage. J Inflamm Res. 18:2955–2973. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang J: Preclinical and clinical research

on inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Prog Neurobiol.

92:463–477. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhou Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Anne Stetler R and

Yang QW: Inflammation in intracerebral hemorrhage: From mechanisms

to clinical translation. Prog Neurobiol. 115:25–44. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Chen AQ, Fang Z, Chen XL, Yang S, Zhou YF,

Mao L, Xia YP, Jin HJ, Li YN, You MF, et al: Microglia-derived

TNF-alpha mediates endothelial necroptosis aggravating blood

brain-barrier disruption after ischemic stroke. Cell Death Dis.

10:4872019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Zlokovic BV: The blood-brain barrier in

health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 57:178–201.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Liu X, Chen X, Zhu Y, Wang K and Wang Y:

Effect of magnolol on cerebral injury and blood brain barrier

dysfunction induced by ischemia-reperfusion in vivo and in vitro.

Metab Brain Dis. 32:1109–1118. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Chen J, Jin H, Xu H, Peng Y, Jie L, Xu D,

Chen L, Li T, Fan L, He P, et al: The neuroprotective effects of

necrostatin-1 on subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats are possibly

mediated by preventing blood-brain barrier disruption and

RIP3-Mediated necroptosis. Cell Transplant. 28:1358–1372. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ronaldson PT and Davis TP: Regulation of

blood-brain barrier integrity by microglia in health and disease: A

therapeutic opportunity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 40(Suppl 1):

S6–S24. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Ozaki E, Delaney C, Campbell M and Doyle

SL: Minocycline suppresses disease-associated microglia (DAM) in a

model of photoreceptor cell degeneration. Exp Eye Res.