Introduction

Lung and colon cancers are among the main causes of

death in developed countries. The life expectancy of patients is

very limited, especially in metastatic disease. Nevertheless, in

recent years, the development of targeted therapies (Tyrosine

Kinase inhibitors or inhibitors of receptors which hyperactivate

survival pathways) has shown great therapeutic promise. For

example, patients with a mutated EGFR gene and wild-type

KRAS gene lung tumor are eligible for gefitinib therapy

(1). In colon cancer, patients

with wild-type KRAS and BRAF could be treated with

panitumumab or cetuximab (2). In

skin cancer, vemurafenib (3) or

imatinib (4) can be used to treat

mutated BRAF (V600E) or c-KIT melanoma, respectively.

As the efficacy of these targeted therapies depends on specific

genetic abnormalities, molecular diagnosis has become essential for

the treatment of cancers. Since 2008, molecular biology platforms

have screened for genetic alterations in EGFR (exons 18–21),

KRAS (codons 12 and 13) and BRAF (codon 600). At the

beginning, the gold standard was Sanger sequencing, but the

technique has low sensitivity and is expensive. With the increasing

number of samples and gene alterations to screen for,

alternon-amplified techniques were developed. For example, allelic

discrimination (5) was developed

to screen for a specific mutation quickly at a relatively low

price. In parallel, screening technologies, such as High Resolution

Melting (6) or fragment analysis

(for indel alterations), were developed to use with Sanger

sequencing, but only in the presence of potential mutations in the

region of interest. Over the years, the number of genes with

genetic alterations that could be targeted by therapies has

increased rapidly. This medical progress has led to the need for

more and more molecular diagnoses. This need has now been met by

the recent development of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), which

has revolutionized molecular diagnosis. Indeed, the sequencing

capacity allows the analysis of dozens of genes on multiplexed

samples. In this paper, we describe the results we obtained with

the Truseq Cancer Panel. In addition to the routinely detected

mutations, NGS analysis, thanks to its high sensitivity, revealed

new mutations in routinely analyzed genes.

Materials and methods

Patients and DNA samples

Eighteen tissue samples with >400 ng gDNA

(Table I) from patients treated at

the Centre Georges-François Leclerc between 2009 and 2013 were

randomly chosen. Genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE tissues with

either the QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Heidelberg, Germany) or the

Maxwell 16 FFPE Plus LEV DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison,

USA). The samples had already been genotyped by allelic

discrimination, fragment analysis and Sanger sequencing. Written

consent was provided by all patients, and the researchers obtained

authorization from the diagnostic centers to use the tumor

samples.

| Table IClinical details of studied

patients. |

Table I

Clinical details of studied

patients.

| Patients | Organ of

origin | Histology | Age (years) |

|---|

| L1 | Lung | Keratinizing poorly

differentiated squamous carcinoma | 61 |

| L2 | Lung | Moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma | 67 |

| L3 | Lung | Poorly

differentiated adenocarcinoma | 62 |

| L4 | Lung | Adenocarcinoma | 50 |

| L5 | Lung | Adenocarcinoma | 69 |

| L6 | Lung | Adenocarcinoma | 55 |

| L7 | Lung | Mucus-secreting

adenocarcinoma | 68 |

| L8 | Lung | Acinar

differentiated mucus-secreting adenocarcinoma | 86 |

| C1 | Colon | Moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma | 55 |

| C2 | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 64 |

| C3 | Colon | Moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma | 59 |

| C4 | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 72 |

| C5 | Colon | Adenosquamous

adenocarcinoma | 70 |

| C6 | Colon | Poorly

differentiated adenocarcinoma | 55 |

| C7 | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 80 |

| C8 | Colon | Poorly

differentiated adenocarcinoma | 72 |

| C9 | Colon | Well differentiated

infiltrating lieberkunien adenocarcinoma | 58 |

| C10 | Colon | Colloidal

adenocarcinoma | 67 |

Whole genome amplification

The Repli-g FFPE kit (Qiagen) was used to amplify

300 ng of gDNA from patients L7 and L8: 10 μl of gDNA solution were

mixed with 8 μl of FFPE buffer, 1 μl of ligation enzyme and 1 μl of

FFPE enzyme. The solution was then incubated at 24°C for 30 min, at

95°C for 5 min and then kept at 4°C. The Repli-g master mix was

prepared by mixing, per sample, 29 μl of Repli-g Midi reaction

buffer and 1 μl of Repli-g Midi DNA Polymerase. This second mixture

(30 μl) was added to the gDNA solution. This solution was then

incubated at 30°C for 2 h, 95°C for 10 min and kept at 4°C.

Amplified DNA was stored at −20°C. Thanks to this protocol, we

obtained 6900 and 6400 ng of amplified gDNA.

Preparation of libraries

Libraries were prepared with the Truseq Cancer Panel

(Illumina, San Diego, USA) by following the manufacturer protocol.

Briefly, 400–1250 ng of gDNA in 5 μl water was hybridized with an

oligo pool. Then, unbound oligos were removed, and

extension-ligation of bound oligos was followed by PCR

amplification. PCR products were cleaned and checked for quality

using Tapestation analysis (Agilent). The PCR product size had to

be around 350 bp. Before sequencing, the libraries were normalized

by the normalization process of the Truseq Cancer Panel.

Sequencing with MiSeq device

As each library possessed a specific primer index

combination (i5 and i7), the libraries were pooled for 2 sequencing

runs (pool no. 1, 10 libraries; pool no. 2, 9 libraries). For the

MiSeq sample sheet, each sample was identified by its specific

index combination. Libraries were paired-end sequenced with 2×151

bp cycles.

Analysis of obtained sequences

At the end of the run, sequences were aligned to the

human genome reference hg19. Generated BAM files were analyzed with

the Genome Golden Helix software (Golden Helix, Bozeman, USA). A

genetic variation was defined by a Q-score above 30 (except for

indel alteration).

Results

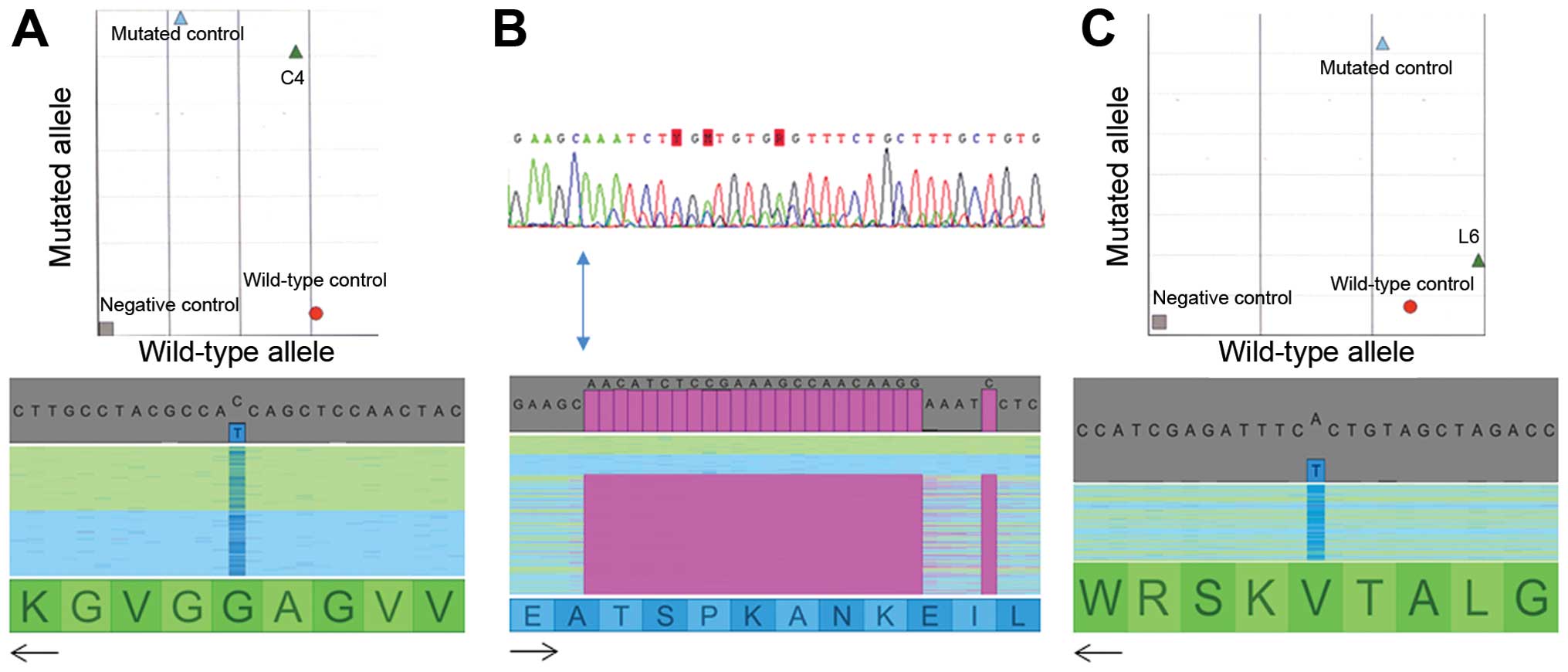

All mutations detected with standard

methods were detected with NGS

In the routine diagnosis of lung or colon

carcinomas, mutations in KRAS (exon 2), EGFR (exon

18–21), BRAF (exon 15) and HER2 (exon 20) genes are

analyzed using three different methods: allelic discrimination for

targeted mutations, fragment analysis for the screening of indel

variations and Sanger sequencing for non-targeted mutations or

characterization of indel abnormalities detected by fragment

analysis. All mutation hotspots are analyzed one by one. Over the

years, more and more genes and mutation hotspots will need to be

explored. For example, exons 3 and 4 of KRAS, and exons 2–4

of NRAS and HRAS need to be analyzed before anti-EGFR

antibody can be prescribed for colon cancer (7,8). In

the first step of our study, we used the Truseq Cancer Panel kit to

sequence samples that had already been analyzed in routine

diagnosis. We then compared the results obtained by NGS with the

results of the routine diagnosis at the same mutational hotspots.

All the mutations detected in the routine diagnosis were also

detected by NGS (Fig. 1 and

Table II). Moreover, mutations

not found in routine diagnosis were detected by NGS. These included

a 15-nt deletion (c.2235_2249delGGAATTAAGAGAAGC) in two lung

carcinomas classified as wild-type using routine methods (patients

L1 and L6). In the L1 sample, another mutation in the KRAS gene

(G12D) was also identified. In patient L6, this 15-nt deletion in

EGFR was concomitant with a V600E BRAF mutation.

| Table IIComparison of results obtained

routinely and with NGS. |

Table II

Comparison of results obtained

routinely and with NGS.

| KRAS | BRAF | EGFR | HER2 |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Patients | Routinea | NGS | Routineb | NGS | Routinec | NGS | Routined | NGS |

|---|

| L1 | WT | G12D | WT | WT | WT | 15-nt

E19 | WT | WT |

| L2 | WT | WT | WT | WT | 15-nt E19 | 15-nt E19 | WT | WT |

| L3 | WT | WT | WT | WT | 24-nt E19 | 24-nt E19 | WT | WT |

| L4 | WT | WT | WT | WT | L858R | L858R | WT | WT |

| L5 | WT | WT | WT | WT | 15-nt E19

T790M | 15-nt E19

T790M | WT | WT |

| L6 | WT | WT | V600E | V600E | WT | 15-nt

E19 | WT | WT |

| L7 | G12C | G12C | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT |

| L8 | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT |

| C1 | WT | WT | WT | V600R | ND | | ND | |

| C2 | WT | WT | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C3 | G13D | G13D | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C4 | G12D | G12D | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C5 | WT | WT | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C6 | WT | WT | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C7 | G13D | G13D | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C8 | WT | WT | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C9 | WT | WT | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

| C10 | WT | WT | WT | WT | ND | | ND | |

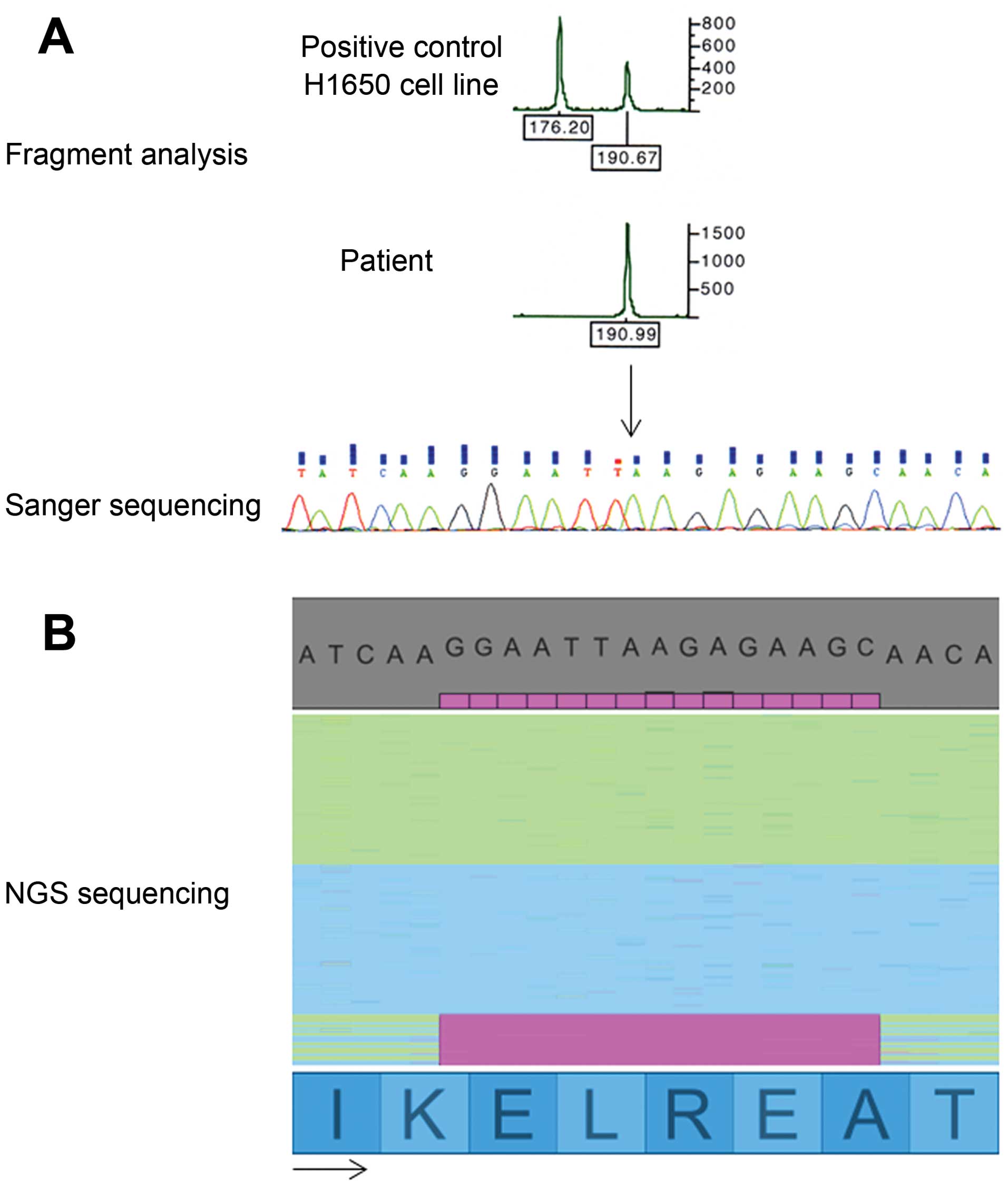

In colon cancer, a ‘common’ 15-nt

deletion in the EGFR gene was detected only with NGS

Up to now, rare mutations of the KRAS gene

have not been routinely analyzed in lung carcinomas. In our small

population, a Q61H mutation in the KRAS gene was found in

the sample L8. This mutation was localized in exon 3, which is not

routinely analyzed in lung cancer. No other alteration was found in

the routinely analyzed genes (HRAS and NRAS).

In colon cancer, only the genes KRAS,

BRAF and very recently NRAS and HRAS are

studied. Concerning rare mutations of KRAS, NRAS and

HRAS, we detected a Q61K mutation in the NRAS gene in

patient C5. As numerous genes were sequenced by the Cancer Panel

kit, we analyzed the results obtained for the PIK3CA,

HER2 and EGFR genes, which are routinely analyzed in

lung carcinomas. No mutations were detected in exon 20 of

HER2, or in exons 18, 20 or 21 of EGFR. In exon 20 of

PIK3CA, an H1047L mutation was detected in patient C9.

Concerning exon 19 of EGFR, a 15-nt deletion (the same as

that observed in lung carcinomas) was detected in three patients

(C4, C6 and C7). As this region was not routinely analyzed for

colon cancer, we decided to perform both fragment analysis and

Sanger sequencing. Neither fragment analysis, nor Sanger sequencing

was able to detect the 15-nt deletion in exon 19 of EGFR in

colon cancer (Fig. 2A). In

contrast, NGS sequencing detected the deletion in >8% of

sequenced fragments (Fig. 2B) for

one patient. The two other patients harbored the mutation in

approximately 4% of read sequences. Among these three patients,

only one did not present a concomitant KRAS mutation.

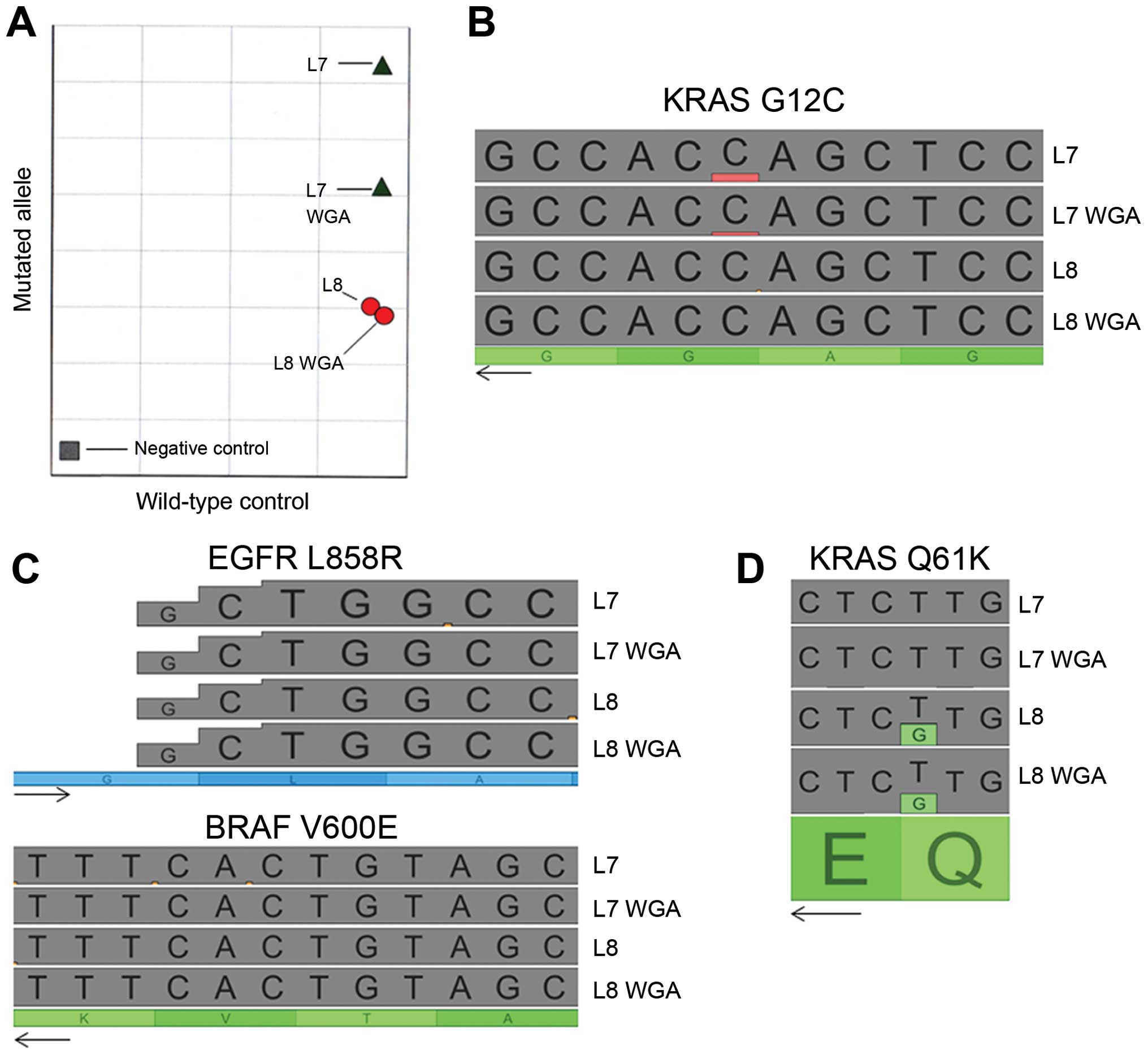

WGA does not alter the NGS sequencing

results

An important limitation in routine diagnosis is the

quantity of gDNA extracted from FFPE samples and another paraffin

block cannot be obtained in most cases. To counteract this

limitation, we tested the impact of Whole Genome Amplification

(WGA) on two samples of gDNA obtained from FFPE tissues. We then

performed allelic discrimination on non-amplified gDNA and

amplified gDNA (Fig. 3A). A

KRAS G12C mutation was detected in both the amplified and

non-amplified sample from patient L7. For patient L8, no

KRAS G12C mutation was observed in either sample. In NGS

analysis, the KRAS G12C mutation was also observed in

patient L7 (non-amplified and WGA) but not in patient L8 (Fig. 3B). We also analyzed other routinely

studied genes to compare the sequences before and after WGA.

Whatever the gene analyzed, no point mutation was induced by the

WGA (e.g., with the V600E BRAF and L858R EGFR

hotpoint mutations in Fig. 3C).

Even the rare mutation Q61H of KRAS was detected in both

non-amplified and WGA gDNA from patient L8 (Fig. 3D). Moreover, the variant allele

fraction was not modified after amplification.

NGS analysis revealed cancer

susceptibility SNP and genetic alterations in some genes

The Illumina Cancer Panel kit studies exons with

mutation hotpoints of 48 genes. We therefore analyzed all covered

sequences for the 8 lung carcinomas and 10 colon carcinomas.

Twenty-eight genetic alterations and three SNP related to cancer

susceptibility or different protein activities were found (Table III). The most frequently altered

gene was TP53 with nine alterations detected in nine

patients. Double mutations in the colon cancer susceptibility genes

APC and SMAD4 were detected in two patients (C3 and

C8, respectively), suggesting a familial risk of colon cancer in

these patients. For the patient with the APC mutation, we

detected a concomitant c-MET activating mutation E168D.

Concerning patient C8, we found a large number of alterations in

different genes (c-KIT, c-MET, FBXW7,

FGFR3, FLT3, IDH1, KRAS, RB1,

SMAD4 and TP53), suggesting high genetic instability

in this SMAD4 mutated tumor. Moreover, thanks to the

non-targeted analysis, we detected two BRAF exon 15

mutations, N581S and V600R, which induce intermediate and strong

activation of the protein, respectively. Furthermore, two mutations

with unknown impact were detected in PIK3CA and PTEN.

Concerning SNP, two patients (L7 and C4) harbored the breast cancer

susceptibility ATM F858L SNP, and one patient (C10) had the

rare c-KIT M541L SNP, which may influence the response to

imatinib. Finally, 10 patients (8 heterozygotes and 2 homozygotes

H472H) harbored the KDR Q472H polymorphism, which has been

reported to increase tumor microvasculature.

| Table IIIExonic SNP and genetic alterations in

other analyzed genes. |

Table III

Exonic SNP and genetic alterations in

other analyzed genes.

| Genes | Nucleotide

variation | Protein sequence

variation | Patients | Impact |

|---|

| APC | c.2626C→T | R876X | C3 | Loss of function

(familial mutation) |

| c.3944C→T | S1315X | C3 | Loss of function

(somatic mutation) (26) |

| ATM | c.2572T→C | F858L | L7, C4 | Breast cancer

susceptibility SNP (23) |

| BRAF | c.1742A→G | N581S | C2 | Intermediate

activated (27) |

|

c.1798_1799GT→AG | V600R | C1 | Strongly activated

(28) |

| c-KIT | c.1621A→C | M541L | C10 | SNP with a

potential effect on imatinib response (29) |

| c.2146G→A | D716N | C8 | Possible resistance

to imatinib (24) |

| c-MET | c.504G→T | E168D | C3 | Activated (19) |

| c.1156C→A | L386I | C8 | Unknown (never

observed) |

| FBXW7 | c.832C→T | R278X | C8 | Uncertain

significance (30) |

| FGFR3 |

c.1196_1197GC→AG | R399H | C8 | Unknown (31) |

| FLT3 | c.2039C→T | A680V | C8 | Activated (32) |

| IDH1 | c.290G→A | G97V | C8 | Loss of wild-type

function (33) |

| KDR | c.1416A→T | Q472H | H: L1-L3, L5,

L7-L8, C5-C6

O: C7, C9 | Increased activity

SNP (25) |

| KRAS | c.408T→A | S136K | C8 | Unknown |

| PIK3CA | c.2176G→A | E726K | C2 | Unknown (34) |

| PTEN | c.563A→T | D187V | L1 | Unknown |

| RB1 |

c.2074_2075insATGA | Y692FsX2 | L2, L5 | Loss of

function |

| c.2119T→C | S707P | C8 | Unknown |

| SMAD4 | c.1009G→A | E337K | C8 | Unknown |

| c.1082G→A | R361H | C8 | Loss of function

(35) |

| TP53 | c.310C→T | Q104X | L1 | Unknowna |

| c.523C→T | R175V | C8 | Unknown |

| c.527G→T | C176F | L5 | Partially

functional/deleteriousa |

| c.536A→G | H179R | C3 |

Non-functional/deleteriousa |

| IVS5+2T→G | G187Fs | C1 | Unknown |

| c.709A→C | M237L | C10 | Partially

functional/deleteriousa |

| c.743G→A | R248Q | C6 |

Non-functional/deleteriousa |

| c.742C→T | R248W | C5 |

Non-functional/deleteriousa |

| c.830G→T | C277F | C7 |

Non-functional/deleteriousa |

Discussion

Molecular diagnosis is the current challenge in

cancer management. Indeed, with the increased number of targeted

therapies and resistance mechanisms developed by cancer cells, the

molecular analysis of tumors is a very important task to achieve

optimal cancer therapy. Sanger sequencing, even when accompanied by

alternon-amplified technologies, such as allelic discrimination or

high resolution melting technology, has shown its limits. Today,

next-generation sequencing is providing exciting new perspectives.

In this study, we tested Truseq Amplicon technology for the

analysis of mutation hotspots of 48 genes in gDNA extracted from

FFPE samples. All of the mutations detected by routine Sanger

sequencing, allelic discrimination or fragment analysis (in

KRAS, BRAF, EGFR genes) were also identified

with NGS analysis. Moreover, other alterations at the mutation

hotspots of the routinely analyzed genes were also detected. These

additional alterations included a G12D KRAS, a V600R

BRAF and a 15-nt deletion in exon 19 of EGFR. The

additional deletion in the EGFR gene was concomitant with

the G12D KRAS mutation in one patient, and with a V600E

BRAF mutation in another patient. KRAS, BRAF and

EGFR mutations are normally exclusive (9) but concomitant KRAS and

EGFR mutations have already been described (10,11).

The identification of concomitant mutations should increase with

the higher sensitivity of NGS technologies. Nevertheless, as it may

be impossible to confirm these ‘new’ mutations using routine

techniques, their clinical relevance and even their existence may

be debatable (12). In the same

way, some mutations are detected by NGS in very few of the read

sequences. For example, the 15-nt deletion found in three colon

carcinomas was detected in less than 8% of the read sequences, and

among these three colon carcinomas, one had no KRAS/BRAF

mutation, one had a concomitant G12D KRAS mutation, and one

also had a G13D KRAS mutation. This observation is quite

disturbing, and raises two questions: was the 15-nt deletion true,

and if so, was this alteration clinically relevant given the small

number detected. Today, the only way to have an answer would be to

treat these patients with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors or to

observe anti-EGFR antibody resistance in these patients. To date,

only patients with KRAS (13), HRAS or NRAS mutations

(7,8) can be diagnosed as immediately

resistant. Concerning our three colon carcinomas, two may benefit

from treatment with EGFR TKI as the G13D KRAS mutation does

not seem to interfere with the inhibition of the EGFR pathway

(14).

With the increase in the number of genes to be

analyzed for molecular diagnosis, the quantity of gDNA obtained

from FFPE tissues will rapidly become a major problem, especially

for lung carcinomas. In this work, we tested Whole Genome

Amplification in two lung carcinomas and analyzed the resulting

samples by NGS. The genetic profile obtained before and after WGA

was qualitatively the same and quantitatively close. Indeed, only

the intensity of the G12C KRAS mutation in patient L7 was

slightly lower in the amplified sample. The strong similarity

between amplified and non-amplified samples is in accordance in

very recent studies, which showed that WGA can be safely used for

diagnosis (15,16). Moreover, through this experiment,

we showed that Truseq Amplicon technology is compatible with

samples treated by WGA.

Among the genes or codons studied in the panel but

not analyzed in routine molecular diagnosis, we detected 27

different alterations in 14 genes. Of these, 9 were detected in the

TP53 gene, which is the most frequently altered gene in

cancer (17). Eight mutations were

in the DNA binding domain of the protein, indicating that these

mutations are deleterious. One mutation occurred in a splice site,

inducing a frameshift that may not be deleterious (18). We detected 2 genes with a double

mutation, APC and SMAD4. The presence of two

mutations in these two colon cancer predisposition genes indicated

that these patients could have been members of families with a high

risk of colon cancer. Both patients harbored mutations in the c-MET

genes. The APC mutated patient had the activating mutation E168D

(19), making him/her eligible for

crizotinib therapy, which is generally used in lung cancer

(20). Concerning the SMAD4

mutated tumor, we detected eight other altered genes, suggesting

high genetic instability in this tumor type (21,22).

The impact of most of these alterations is unknown. Nevertheless,

the activating A680V mutation of FLT3 may be targeted by anti-FLT3

therapies currently in clinical development for the treatment of

leukemia.

Three SNP modifying protein sequences were found.

ATM F858L polymorphism, detected in two patients, is

associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (23), but the small number of patients in

our study does not allow us to draw any conclusions with regard to

the predisposition for colon and lung cancer. Then, c-KIT

M541L polymorphism was found in only one patient. The impact of

this polymorphism in not known, but it has been suggested that it

may affect the response to imatinib (24). Finally, KDR Q472H polymorphism was

the most interesting alteration. Indeed, tumors with histidine show

higher vascularization than do tumors with glutamine (25). In the Caucasian population, the

frequency of each genotype is 58, 36 and 6% for Q472Q, Q472H and

H472H, respectively. In our small population of tumors (n=18), we

found enrichment of the histidine allele in 55.5% of our tumors

(44.5% Q/Q, 44.5% Q/H and 11% H/H). In lung carcinomas we observed

an enrichment of heterozygous tumors (75%), whereas in colon, the

enrichment concerned homozygous H/H tumors. Moreover, during the

analysis, we found that the presence of each allele was not 50/50

in heterozygous tumors, but varied from 9 to 96% of the read

sequences. This raises the question of true polymorphism or a

selection of tumor cells with a high angiogenic capacity. To answer

this question, it would be necessary to analyze the constitutive

DNA of each patient. According to the study by Glubb et al,

patients with heterozygous or homozygous histidine tumors could be

more sensitive to inhibiting treatments of VEGFR2 or to

bevacizumab.

In conclusion, the analysis by NGS of FFPE lung and

colon carcinomas identified the alterations highlighted by routine

molecular diagnosis techniques. Thanks to its higher sensitivity,

NGS analysis revealed new mutations that were not detected

routinely. The impossibility to confirm the presence of these

mutations by another technology is problematic, and the only way to

answer this question is by conducting clinical trials that compare

treatments of patients diagnosed by routine techniques or by NGS.

Finally, the use of NGS in routine practice could revolutionize the

management of cancer patients. Indeed, simultaneous analysis of

numerous genes could identify drug-sensitive alterations generally

observed in other cancer types (for example a c-MET

alteration in a colon carcinoma that would be treated with

crizotinib in lung cancer). Nevertheless, high throughput studies

that combine NGS analysis and clinical trials need to be performed

before NGS analysis can be generalized in routine molecular

diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Philip Bastable for editing the

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R,

Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat

SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG, Louis DN, Christiani DC, Settleman J and

Haber DA: Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor

receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to

gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 350:2129–2139. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F,

Sartore-Bianchi A, Arena S, Saletti P, De Dosso S, Mazzucchelli L,

Frattini M, Siena S and Bardelli A: Wild-type BRAF is required for

response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal

cancer. J Clin Oncol. 26:5705–5712. 2008.

|

|

3

|

Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen

JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, Dummer R, Garbe C, Testori A, Maio M,

Hogg D, Lorigan P, Lebbe C, Jouary T, Schadendorf D, Ribas A, O’Day

SJ, Sosman JA, Kirkwood JM, Eggermont AM, Dreno B, Nolop K, Li J,

Nelson B, Hou J, Lee RJ, Flaherty KT and McArthur GA; BRIM-3 Study

Group. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF

V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 364:2507–2516. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD,

Chapman PB, Roman RA, Teitcher J, Panageas KS, Busam KJ,

Chmielowski B, Lutzky J, Pavlick AC, Fusco A, Cane L, Takebe N,

Vemula S, Bouvier N, Bastian BC and Schwartz GK: KIT as a

therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA. 305:2327–2334.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lee LG, Connell CR and Bloch W: Allelic

discrimination by nick-translation PCR with fluorogenic probes.

Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3761–3766. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liew M, Pryor R, Palais R, Meadows C,

Erali M, Lyon E and Wittwer C: Genotyping of single-nucleotide

polymorphisms by high-resolution melting of small amplicons. Clin

Chem. 50:1156–1164. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S,

Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham

D, Jassem J, Rivera F, Kocákova I, Ruff P, Błasińska-Morawiec M,

Šmakal M, Canon JL, Rother M, Williams R, Rong A, Wiezorek J, Sidhu

R and Patterson SD: Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations

in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 369:1023–1034. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fornaro L, Lonardi S, Masi G, Loupakis F,

Bergamo F, Salvatore L, Cremolini C, Schirripa M, Vivaldi C, Aprile

G, Zaniboni A, Bracarda S, Fontanini G, Sensi E, Lupi C, Morvillo

M, Zagonel V and Falcone A: FOLFOXIRI in combination with

panitumumab as first-line treatment in quadruple wild-type (KRAS,

NRAS, HRAS, BRAF) metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a phase II

trial by the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest (GONO). Ann Oncol.

24:2062–2067. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Reddi HV: Mutations in the EGFR pathway:

clinical utility and testing strategies. Clin Lab News. 39:14–16.

2013.

|

|

10

|

Schmid K, Oehl N, Wrba F, Pirker R, Pirker

C and Filipits M: EGFR/KRAS/BRAF mutations in primary lung

adenocarcinomas and corresponding locoregional lymph node

metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 15:4554–4560. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tuononen K, Mäki-Nevala S, Sarhadi VK,

Wirtanen A, Rönty M, Salmenkivi K, Andrews JM, Telaranta-Keerie AI,

Hannula S, Lagström S, Ellonen P, Knuuttila A and Knuutila S:

Comparison of targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) and

real-time PCR in the detection of EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF mutations on

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor material of non-small cell

lung carcinoma-superiority of NGS. Genes Chromosomes Cancer.

52:503–511. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

McCourt CM, McArt DG, Mills K, Catherwood

MA, Maxwell P, Waugh DJ, Hamilton P, O’Sullivan JM and Salto-Tellez

M: Validation of next generation sequencing technologies in

comparison to current diagnostic gold standards for BRAF, EGFR and

KRAS mutational analysis. PLoS One. 8:e696042013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Misale S, Yaeger R, Hobor S, Scala E,

Janakiraman M, Liska D, Valtorta E, Schiavo R, Buscarino M,

Siravegna G, Bencardino K, Cercek A, Chen CT, Veronese S, Zanon C,

Sartore-Bianchi A, Gambacorta M, Gallicchio M, Vakiani E, Boscaro

V, Medico E, Weiser M, Siena S, Di Nicolantonio F, Solit D and

Bardelli A: Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to

anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature. 486:532–536.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tejpar S, Celik I, Schlichting M,

Sartorius U, Bokemeyer C and Van Cutsem E: Association of KRAS G13D

tumor mutations with outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal

cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without

cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 30:3570–3577. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Della Starza I, De Novi LA, Nunes V, Del

Giudice I, Ilari C, Marinelli M, Negulici AD, Vitale A, Chiaretti

S, Foà R and Guarini A: Whole-genome amplification for the

detection of molecular targets and minimal residual disease

monitoring in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol.

165:341–348. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hasmats J, Gréen H, Orear C, Validire P,

Huss M, Käller M and Lundeberg J: Assessment of whole genome

amplification for sequence capture and massively parallel

sequencing. PLoS One. 9:e847852014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vogelstein B, Sur S and Prives C: p53: the

most frequently altered gene in human cancers. Nat Educat.

3:62010.

|

|

18

|

Végran F, Rebucci M, Chevrier S, Cadouot

M, Boidot R and Lizard-Nacol S: Only missense mutations affecting

the DNA binding domain of p53 influence outcomes in patients with

breast carcinoma. PLoS One. 8:e551032013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ma PC, Jagadeeswaran R, Jagadeesh S,

Tretiakova MS, Nallasura V, Fox EA, Hansen M, Schaefer E, Naoki K,

Lader A, Richards W, Sugarbaker D, Husain AN, Christensen JG and

Salgia R: Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and its

therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in

non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 65:1479–1488. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tanizaki J, Okamoto I, Okamoto K, Takezawa

K, Kuwata K, Yamaguchi H and Nakagawa K: MET tyrosine kinase

inhibitor crizotinib (PF-02341066) shows differential antitumor

effects in non-small cell lung cancer according to MET alterations.

J Thorac Oncol. 6:1624–1631. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Markowitz S, Wang J, Myeroff L, Parsons R,

Sun L, Lutterbaugh J, Fan RS, Zborowska E, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein

B, et al: Inactivation of the type II TGF-beta receptor in colon

cancer cells with microsatellite instability. Science.

268:1336–1338. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Woodford-Richens KL, Rowan AJ, Gorman P,

Halford S, Bicknell DC, Wasan HS, Roylance RR, Bodmer WF and

Tomlinson IP: SMAD4 mutations in colorectal cancer probably occur

before chromosomal instability, but after divergence of the

microsatellite instability pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

98:9719–9723. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Struewing JP: Genomic approaches to

identifying breast cancer susceptibility factors. Breast Dis.

19:3–9. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Debiec-Rychter M, Cools J, Dumez H, Sciot

R, Stul M, Mentens N, Vranckx H, Wasag B, Prenen H, Roesel J,

Hagemeijer A, Van Oosterom A and Marynen P: Mechanisms of

resistance to imatinib mesylate in gastrointestinal stromal tumors

and activity of the PKC412 inhibitor against imatinib-resistant

mutants. Gastroenterology. 128:270–279. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Glubb DM, Cerri E, Giese A, Zhang W, Mirza

O, Thompson EE, Chen P, Das S, Jassem J, Rzyman W, Lingen MW,

Salgia R, Hirsch FR, Dziadziuszko R, Ballmer-Hofer K and Innocenti

F: Novel functional germline variants in the VEGF receptor 2 gene

and their effect on gene expression and microvessel density in lung

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 17:5257–5267. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Albuquerque C, Breukel C, van der Luijt R,

Fidalgo P, Lage P, Slors FJ, Leitão CN, Fodde R and Smits R: The

‘just-right’ signaling model: APC somatic mutations are selected

based on a specific level of activation of the beta-catenin

signaling cascade. Hum Mol Genet. 11:1549–1560. 2012.

|

|

27

|

Fratev FF and Jónsdóttir SO: An in silico

study of the molecular basis of B-RAF activation and conformational

stability. BMC Struct Biol. 9:472009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Klein O, Clements A, Menzies AM, O’Toole

S, Kefford RF and Long GV: BRAF inhibitor activity in V600R

metastatic melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 49:1073–1079. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Grabellus F, Worm K, Sheu SY, Siffert W,

Schmid KW and Bachmann HS: The prevalence of the c-kit exon 10

variant, M541L, in aggressive fibromatosis does not differ from the

general population. J Clin Pathol. 64:1021–1024. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Davis H, Lewis A, Behrens A and Tomlinson

I: Investigation of the atypical FBXW7 mutation spectrum in human

tumours by conditional expression of a heterozygous propellor tip

missense allele in the mouse intestines. Gut. 63:792–799. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS,

Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, Cho J, Suh J, Capelletti M,

Sivachenko A, Sougnez C, Auclair D, Lawrence MS, Stojanov P,

Cibulskis K, Choi K, de Waal L, Sharifnia T, Brooks A, Greulich H,

Banerji S, Zander T, Seidel D, Leenders F, Ansén S, Ludwig C,

Engel-Riedel W, Stoelben E, Wolf J, Goparju C, Thompson K, Winckler

W, Kwiatkowski D, Johnson BE, Jänne PA, Miller VA, Pao W, Travis

WD, Pass HI, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Thomas RK, Garraway LA, Getz G

and Meyerson M: Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with

massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 150:1107–1120. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Piccaluga PP, Bianchini M and Martinelli

G: Novel FLT3 point mutation in acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet

Oncol. 4:6042003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ward PS, Cross JR, Lu C, Weigert O,

Abel-Wahab O, Levine RL, Weinstock DM, Sharp KA and Thompson CB:

Identification of additional IDH mutations associated with

oncometabolite R(−)-2-hydroxyglutarate production. Oncogene.

31:2491–2498. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Jaiswal BS, Janakiraman V, Kljavin NM,

Chaudhuri S, Stern HM, Wang W, Kan Z, Dbouk HA, Peters BA, Waring

P, Dela Vega T, Kenski DM, Bowman KK, Lorenzo M, Li H, Wu J,

Modrusan Z, Stinson J, Eby M, Yue P, Kaminker JS, de Sauvage FJ,

Backer JM and Seshagiri S: Somatic mutations in p85alpha promote

tumorigenesis through class IA PI3K activation. Cancer Cell.

16:463–474. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Miyaki M, Iijima T, Konishi M, Sakai K,

Ishii A, Yasuno M, Hishima T, Koike M, Shitara N, Iwama T,

Utsunomiya J, Kuroki T and Mori T: Higher frequency of Smad4 gene

mutation in human colorectal cancer with distant metastasis.

Oncogene. 18:3098–3103. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C,

Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P and Olivier M: Impact of mutant p53

functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor

phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53

database. Hum Mutat. 28:622–629. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|