Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most

aggressive malignancies worldwide. Twenty percent of primary

colorectal cancer diagnoses reveal remote metastases. Available

therapies still offer a poor prognosis and patients have a <10%

five-year survival rate (1). As

evidenced by genetic modifications, environmental impacts, diet and

lifestyles, the underlying mechanisms of CRC have been intensively

studied.

Dysregulation of cell energetics was just counted in

as one of the cancer hallmarks. Most cancers have a high request

for nutrients and energy to support their rapid growth. Almost a

century ago, the Nobel laureate Otto Warburg discovered more

lactate (indicating higher glycolysis) was secreted in cancer cells

than normal cells under aerobic conditions (2). This finding was later termed as the

'Warburg effect', indicating the hypothesis that even equipped with

normal mitochondria, cancer cells still relied on both

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and glycolysis to

sustain survival and growth (3).

Mitochondria are important players in the

maintenance of cellular homeostasis, as they generate ATP via

OXPHOS. Mitochondrial metabolism occurs during the tricarboxylic

acid (TCA) cycle. Electron transport chain (ETC) has, therefore,

become a crucial focus of cancer treatment. In addition, TCA cycle

provides intermediates for amino acid and lipid synthesis. The

amplified demand for energy supplement in cancer cells endows

targeting ETC a promising strategy to restrict cancer progression.

Compounds that target the mitochondria have drawn worldwide

attention. For example, metformin, a diabetes drug, obstructed

mitochondrial complex I and exhibited impressing effects on various

cancer models (4).

As a metabolic sensor in energy homeostasis,

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is important for regulating

mitochondrial content and maintaining glucose homeostasis. In

metabolically active cancer cells, impaired mitochondrial OXPHOS

would lead to AMPK activation. AMPKα can be phosphorylated by

upstream kinases, including calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein

kinase 2 (CaMKK2), liver kinase B1 and TAK1 (5). Reactive oxygen species

(ROS)-dependent increases in cytosolic calcium activated AMPK

signaling via CAMKK2 (6). One of

the most important consequences of AMPK activation was mTORC1

inactivation. AMPK/mTOR activation has been demonstrated to be

involved in mesenchymal stem cells promoted-colorectal cancer

progression (7). Moreover, mTOR

signaling was greatly provoked in glandular elements of CRC and

colorectal adenomas with advanced intraepithelial neoplasia

(8).

Other than inhibiting TCA, blunting aerobic

glycolysis is also a promising approach to selectively inhibit

cancer cells which mainly rely on this pathway. Enzymes involved in

the glycolytic pathway served as substrates for anticancer therapy.

Right-sided colon tumors showed significantly higher glucose

transporter 1 (GLUT1) mRNA levels, which is a rate-limiting

transporter for glucose uptake (8). Hexokinase II (HKII) catalyzes the

ATP-dependent phosphorylation of glucose. High HKII and low

p-pyruvate dehydrogenase expression in the invasive lesions of CRC

tumors is predictive of tumor aggressiveness (9,10).

Recently, several potent glycolytic inhibitors have been developed,

such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) and 3-bromopyruvate (3BP). 3BP is

an inhibitor of HKII (11,12).

The mitochondrial damage induced by caulerpin, a

Caulerpa spp. algal pigment, was first mentioned by Liu

et al (13), who suggested

that mitochondrial respiration can be intervened by caulerpin via

suppressing ETC complex I of breast cancer cells in hypoxia.

Recently, the study group of Ferramosca et al found that

caulerpin selectively repressed the activity of complex II in rat

liver mitochondria (14). The

observations that caulerpin suppresses HIF-1 activation and

displays cytotoxicity to human dermal fibroblasts support further

exploration into the anticancer mechanism of caulerpin. Recent

studies showed that glycolysis inhibitors stimulated cell death and

sensitized cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents in various types

of cancers (15,16). To date, there is no published

literature showing that glycolysis inhibitors sensitized colorectal

cells to caulerpin.

Although caulerpin inhibited mitochondrial

respiration, whether disturbing complex I would abolish cells

proliferation remained obscure. Moreover, activation of the energy

sensor AMPK can promote glycolysis to replenish the loss of ATP.

Herein, our study aimed to explore the intracellular molecular

mechanism involved in caulerpin-modulated energy metabolism in CRC

cell lines and further examine whether the combination of caulerpin

and glycolysis inhibitors will orchestrate the stimulation of cell

death both in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Chemical and reagents

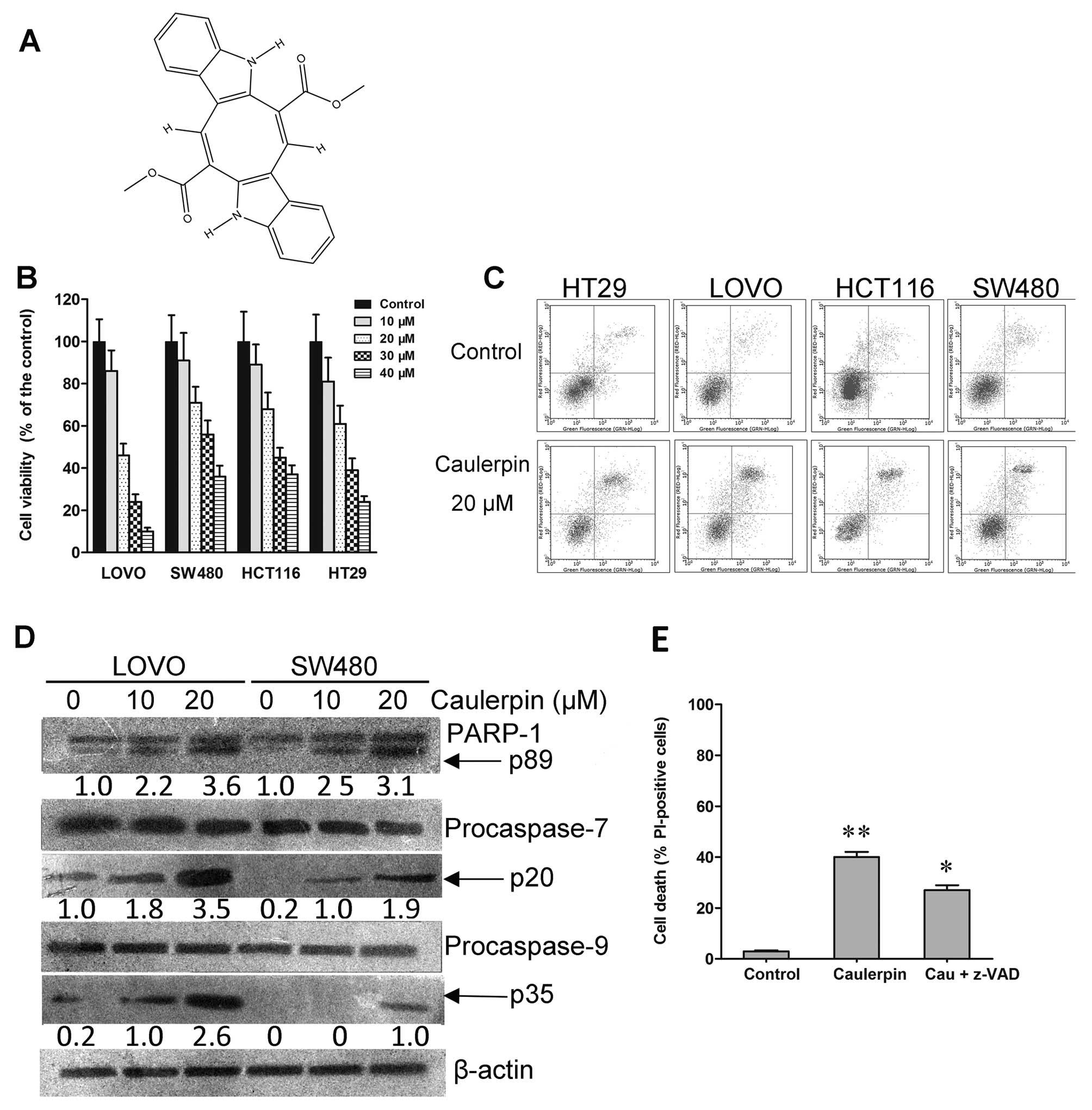

Caulerpin (Fig. 1A)

of 99% purity was purchased from Yuanye Pharmaceutics (Shanghai,

China). A stock solution of metformin was made at a concentration

of 100 mM in DMSO and stored at −20°C. KN93, 2DG and 3BP were

obtained from Sigma (Shanghai, China). Antibodies against PARP,

p-p70S6K, p70S6K, p-S6, S6, p-4EBP1, 4EBP1, AMPKα1, AMPKα2 and

β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa

Cruz, CA, USA). AMPKα, p-AMPKα (Thr172), p-ACC (Ser79), ACC,

procaspase-7, procaspase-9 antibodies were purchased from Cell

Signaling Technology (Denver, MA, USA). Horseradish

peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies were obtained from Promega

(Madison, WI, USA).

Cell culture

The human colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116 and

HT29 were obtained from ATCC. LOVO and SW480 were obtained from the

Cell Bank of the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell

Biology, Shanghai, China (http://www.cellbank.org.cn). All cell lines were

cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum,

100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin and

maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5%

CO2. For glucose deprivation experiments, medium was

replaced with DMEM containing non-glucose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad,

CA, USA).

Cell viability assay

The effects of drug treatment on the viability of

colorectal cell lines were assessed with a cell counting kit-8 from

Sigma (17), as described by the

manufacturer. Briefly, 2×104 cells were seeded into

96-well plates. After treatment, CCK-8 solution was added to each

well and cells were further incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The

absorption was measured using a multiskan spectrum microplate

reader at 450 nm. All the experiments were repeated at least three

times.

Apoptosis detection

Briefly, the cells were treated with caulerpin for

24 h. Cells (1×106) were centrifuged and harvested

(18). Next, the cells were

suspended in binding buffer, containing Annexin V-FITC and PI and

then incubated for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. The

stained cells were analyzed using a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences, Flanklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

and ROS determination

Briefly, LOVO and SW480 cells were seeded in a

12-well plate at ~80% confluence. After receiving indicated

treatment, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in buffer solution

containing lipophilic cation JC-1 (KeyGen, Nanjing, China) or DCFDA

(Invitrogen), cells were re-suspended and fluorescence was measured

using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Two fluorescence parameters,

channel 1 (green fluorescence, FL1) at 530 nm and channel 2 (red

fluorescence, FL2) at 590 nm, were used to measure MMP (19). Bright green fluorescence produced

by DCFDA means high level of ROS (20).

Western blot analysis

Cells following different treatments were lysed with

RIPA buffer. Protein concentration was determined using a Coomassie

blue staining method (21). An

equal amount of protein (50 µg) was separated on 10%

SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were

incubated with primary antibodies in 5% BSA at 4°C overnight. The

membranes were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary

antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoreactive bands were

detected with an ECL kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology,

Shanghai, China).

Metabolic analysis

Rat liver mitochondria (0.3 mg protein/ml) and

saponin-permeabilized or intact cells (5×106) were

incubated with caulerpin for indicated time. The oxygen consumption

rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were

measured using an XFe-96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse

Bioscience, North Billerica, MA, USA). After attachment to XFe cell

culture plates, cells were washed with XF assay medium and

equilibrated for 1 h. ECAR were determined by the supplement of

2DG. ATP content was examined from OCR differences from basal rate

after adding oligomycin. Different substrates were added to

evaluate mitochondrial respiration when respiratory complex I to IV

was stimulated respectively. Bioenergetic profiling to distinguish

the site within the ETC controlled by caulerpin was performed as

previously described (22).

Measurements were normalized by total protein content with Lowry

assay.

Generation of AMPKα1-knockout cell lines

with a CRISPR/Cas9 system

Two single guide RNAs (sgRNA) targeting unique

sequences of the AMPKα1 gene were designed and cloned into the

pSpCas9 (BB)-2A-Puro (PX459) V2.0 (Plasmid #62988; Addgene)

plasmid, which contains a puromycin resistance cassette. sgRNAs

were as follows: 5′-CACCGTACATTCTGGGTGACACGCT-3′ and

5′-AAACAGCGTGTCACCCAGAATGTAC-3′. After transfection, the cells were

cultured in a medium containing puromycin for 48 h (23). Cells resistant to the drug were

then selected by FACS for clonal expansion. Gene deficiency in LOVO

cells was examined by western blotting with an anti-AMPKα1

antibody.

RNA interference

Scramble siRNA, siRNA targeting AMPKα2 and siRNA

transfection reagent were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA,

USA). Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen)

according to the instruction (24).

In vivo tumor growth assay

Four to 6-week-old athymic mice, which were obtained

from SLAC Lab Animal Center of Shanghai (Shanghai, China), were

housed under standard conditions. This experiment was conducted in

accordance with the guidelines issued by the State Food and Drug

Administration (SFDA of China). The experiments were approved by

the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ningbo No. 2

Hospital, Ningbo, China. Cells (1×107) in culture medium

were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of each mouse

(25). Tumor size was monitored by

using micrometer calipers every other day for a 30-days period and

calculated with a formula: tumor volume (mm3) =

width2 × length/2. When tumor volume reached ~75

mm3, nude mice were divided into three groups (6

mice/group): saline control, caulerpin (30 mg/kg, in saline with

0.2% CMC-Na), 3BP (15 mg/kg, in saline) or combination group. The

oral gavage was executed every other day. It began on day 1, and

finished on day 30. At the end of the experiments, all the mice

were euthanized. Tumor tissues were used for immunohistochemistry

assay.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections were heat-fixed,

deparaffinized, and rehydrated through a graded alcohol series

(100, 95, 85 and 75%). Antigen retrieval was performed with citrate

buffer and treated with 3% H2O2 to block

endogenous peroxidase activity prior to the treatment with primary

antibodies (anti-PCNA, 1:100; anti-mTOR, 1:200). The tissues were

then incubated with the secondary biotinylated antispecies

antibody. Counterstaining was performed using hematoxylin (26).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical

significance were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by

unpaired Student's t-test. For comparison of multiple samples, the

Tukey-Kramer test was used. All data were analyzed with GraphPad

PRISM 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Caulerpin inhibits cell viability in

colorectal cell lines

In the present study, we examined the anticancer

property of caulerpin in various colorectal cancer cell lines

(HT29, LOVO, HCT116 and SW480). A growth inhibitory effect was

observed in the four colorectal cell lines after 48 h exposure,

with IC50 values ranging from 20 to 31 µM

(Fig. 1B). Among them, LOVO cells

were most sensitive, with 50% inhibition rate at the concentration

of 20 µM, while SW480 cells were least sensitive to

caulerpin. As shown in Fig. 1C,

caulerpin induced apoptosis to colorectal cells, though to a

different extent. Caulerpin augmented the activities of PARP-1,

caspase-9 and caspase-7 in LOVO cells, as indicated by their

cleavage (Fig. 1D), but the

broad-range caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk only partially prevented

cell death, signifying that other caspase-independent signaling was

engaged in the action of caulerpin (Fig. 1E).

Caulerpin inhibits OXPHOS and disturbs

mitochondrial function via the inhibition of mitochondrial complex

I

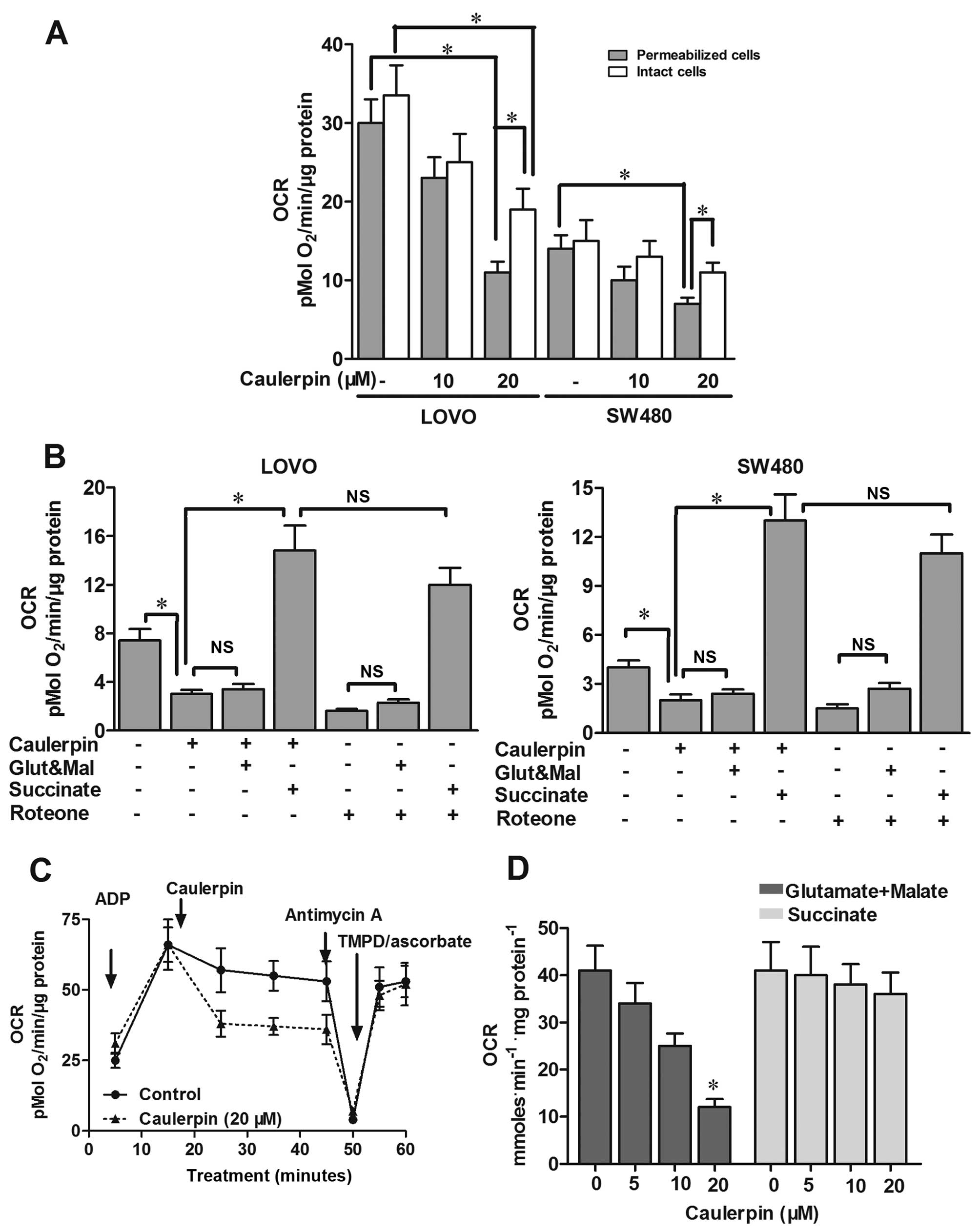

Previous findings illustrated that caulerpin

impaired mitochondrial ETC in cisplatin-resistant C13 cells and

human breast cancer T47D cells (13,14),

but its effects on oxygen consumption have not been fully

addressed. Additionally, whether the emergence of an energy stress

correlates with the anticancer activity of caulerpin in colorectal

cells needs to be explored. In the present study, oxygen

consumption was inhibited by ~60% in SW480 and LOVO cells after

caulerpin treatment. The phenomenon was more obvious in

permeabilized cells than intact cells (Fig. 2A). LOVO cells pretreated with

caulerpin (20 µM, 2 h) were then permeabilized with saponin.

Although malate and glutamate (ETC complex I substrates) failed to

restore caulerpin-triggered downregulation of mitochondrial

respiration in LOVO cells, complex II substrate succinate rescued

mitochondrial respiration in LOVO cells pretreated with caulerpin,

indicating that caulerpin caused impairment to complex I (Fig. 2B). The inhibitory effect of

caulerpin on mitochondria respiration resembled that seen from

rotenone, a complex I inhibitor (Fig.

2B). Moreover, in the incubation media containing succinate,

respiration was suppressed by supplementation with complex III

inhibitor antimycin A, proving that the ETC still works. A

combination of TMPD/ascorbate (complex IV substrates) successfully

rebooted respiration perturbed by antimycin A (Fig. 2C). In mitochondria isolated from

rat liver, similar results were obtained. In the media containing

malate and glutamate, oxygen consumption was suppressed due to

caulerpin treatment, however, not in the presence of succinate

(Fig. 2D). The results

demonstrated that caulerpin brought about an intervention to

mitochondrial function, via inhibition of mitochondrial complex I

without interfering complexes II, III or IV.

Caulerpin induces a drop in mitochondrial

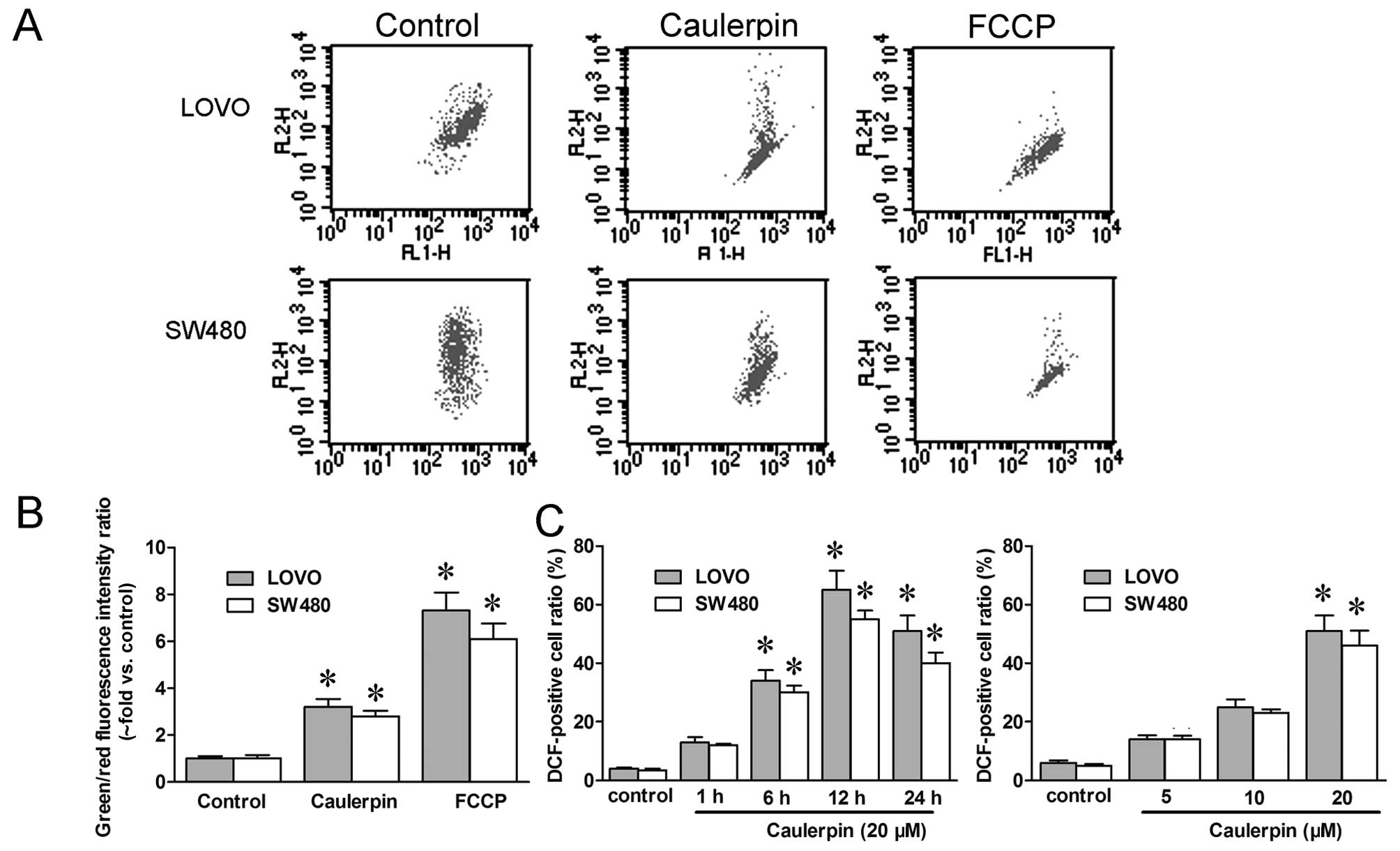

membrane potential and a surge in ROS level

Since mitochondrial function was impaired by

caulerpin, we then examined mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨM)

and ROS with flow cytometry, repectively. JC-1 is a cationic dye

which accumulates in mitochondria in response to potential change,

and the rise in the green/red fluorescence intensity ratio reflects

mitochondrial depolarization. Herein, JC-1 fluorescent probes were

utilized to analyze ΔΨM. In Fig.

3B, a significant advance in green/red fluorescence ratio

(almost 3-fold vs. control) was obtained in both LOVO and SW480

cells treated with caulerpin, pointing to a reduction in ΔΨM. FCCP,

an electron transport chain uncoupler, was applied as the positive

control. Likewise, intracellular ROS concentration was measured by

flow cytometry with the fluorescence dye DCF-DA. In a

concentration-dependent manner, caulerpin rapidly upregulated ROS

level at 1 h post-induction, and up to 24 h (Fig. 3C).

Caulerpin stimulates AMPK signaling and

inhibits mTORC1-4E-BP1 axis

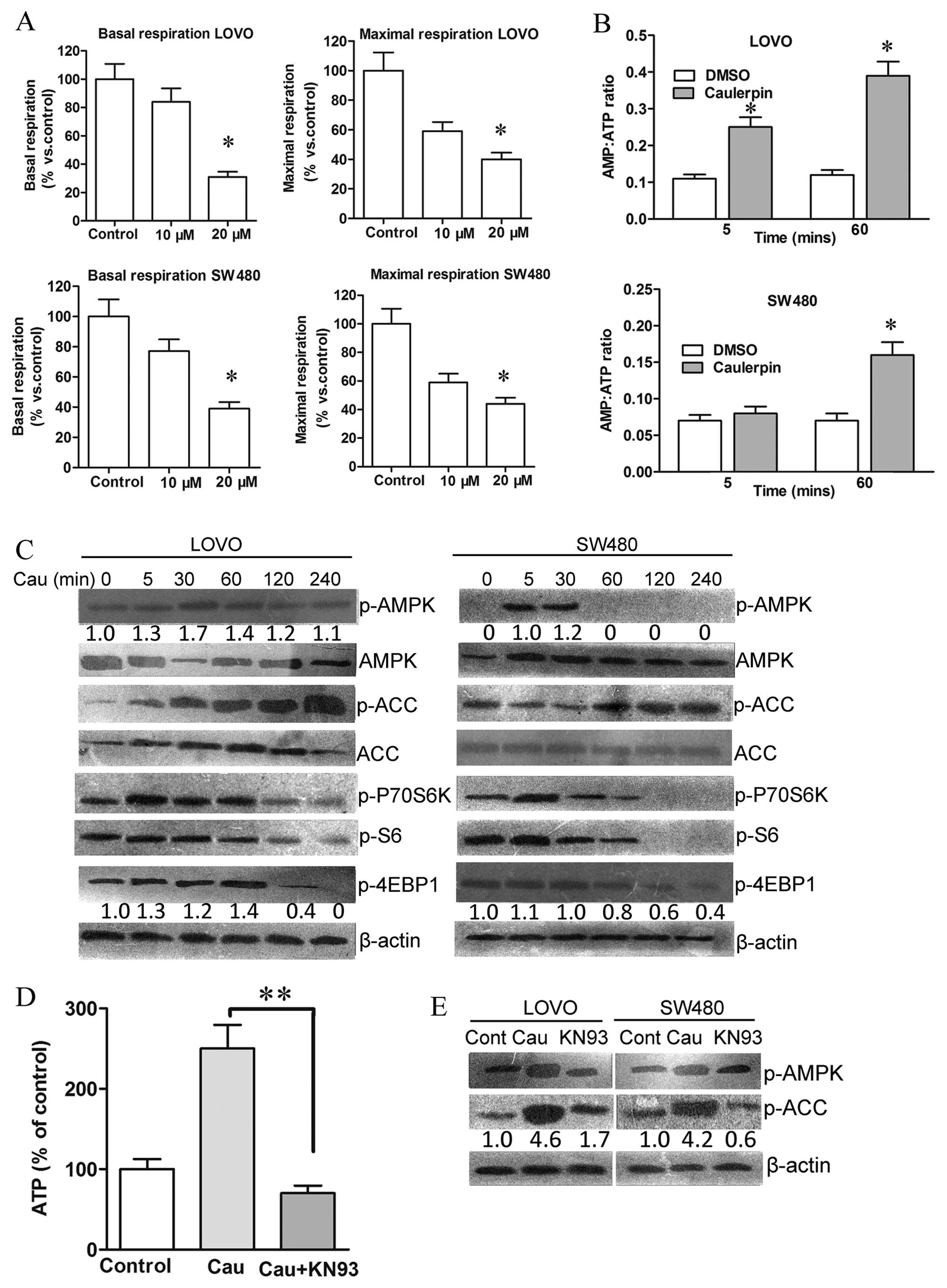

The metabolic profile of colorectal cancer cells was

further examined with the Seahorse XF-e96 analyzer. Caulerpin

treatment inhibited both maximal and basal respiration (Fig. 4A), accompanied by an increment in

AMP/ATP ratio, which could be observed after 5 min and 1 h

incubation with caulerpin in LOVO cells (Fig. 4B). AMPK is a crucial energetic

sensor that is activated either by decreased cellular ATP levels or

by ROS elevation (27). Activated

AMPK will further suppress mTOR signaling for cellular adaptation

in a stress condition (28). In

the present study, caulerpin-triggered phosphorylation of AMPK and

the phosphorylation of the downstream target ACC were observed in

both cell lines, accompanied with inhibition of the downstream

mTORC1 targets 4E-BP1 and S6 (Fig.

4C).

As a kinase responsive to oxidative activation

upstream of AMPK, the essential role of CaMKII was explored to

uncover the mechanism of caulerpin-elicited AMPK activation

(29). As shown in Fig. 4D, the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 reduced

caulerpin-induced ATP levels in colorectal cells, and induced a

remarkable dephosphorylation of AMPK and ACC. These results

signified that caulerpin-stimulated AMPK activation was

CaMKII-dependent.

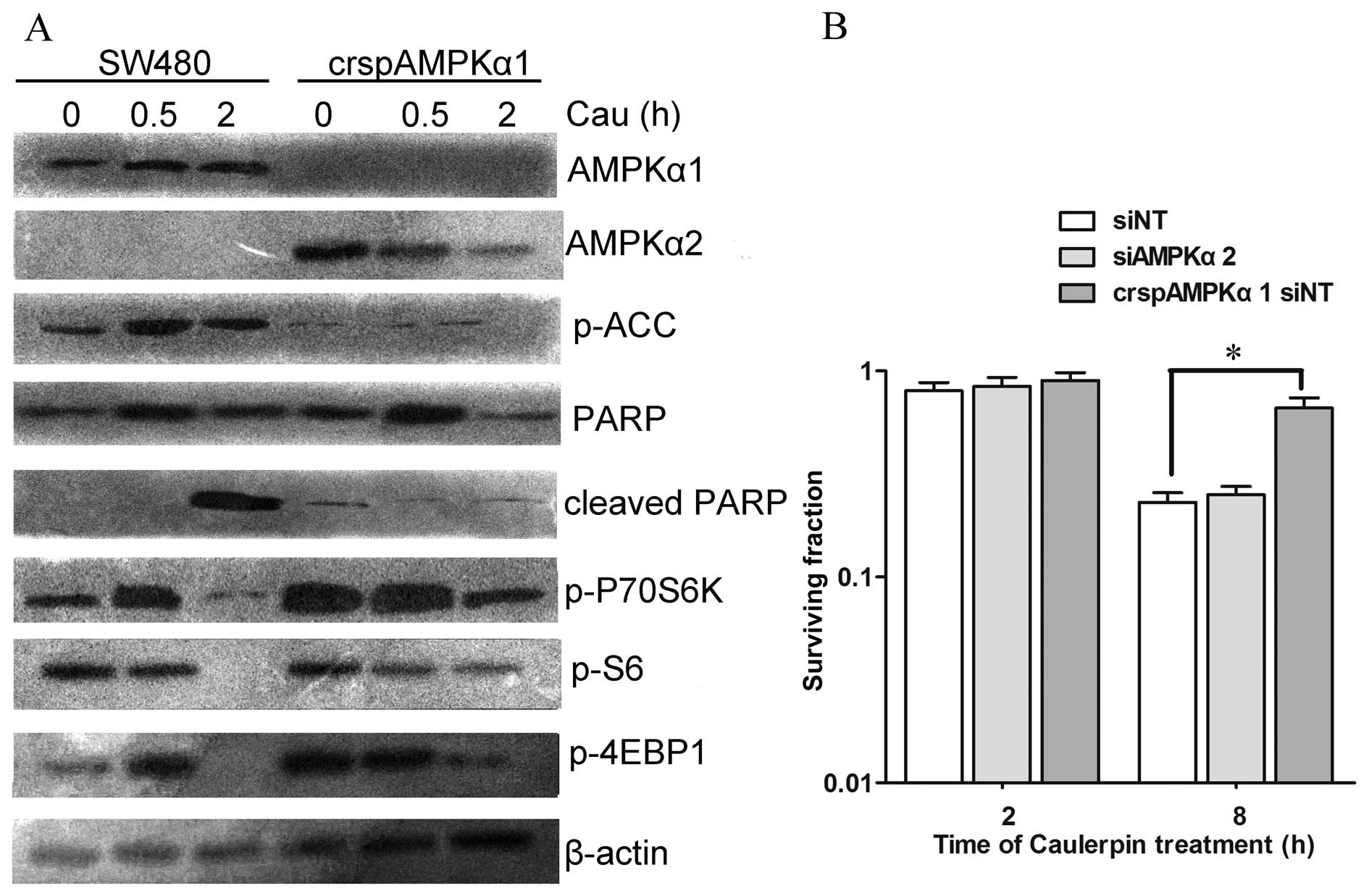

The role of AMPKα1 during caulerpin

treatment

To further dissect the effect of AMPK isoforms on

the viability of cells treated with caulerpin, the CRISPR-cas9

system was applied to knock out AMPKα1. crspAMPKα1 attenuated

caulerpin-induced inactivation of mTOR pathway. Loss of AMPKα1

generated a compensatory growth in AMPKα2 expression (Fig. 5A). CCK-8 assay displayed that knock

out of AMPKα1 protected cells against caulerpin-induced

cytotoxicity (2 and 8 h), while siAMPKα2 exhibited no significant

influence on cell death, which was induced by caulerpin treatment

(Fig. 5B).

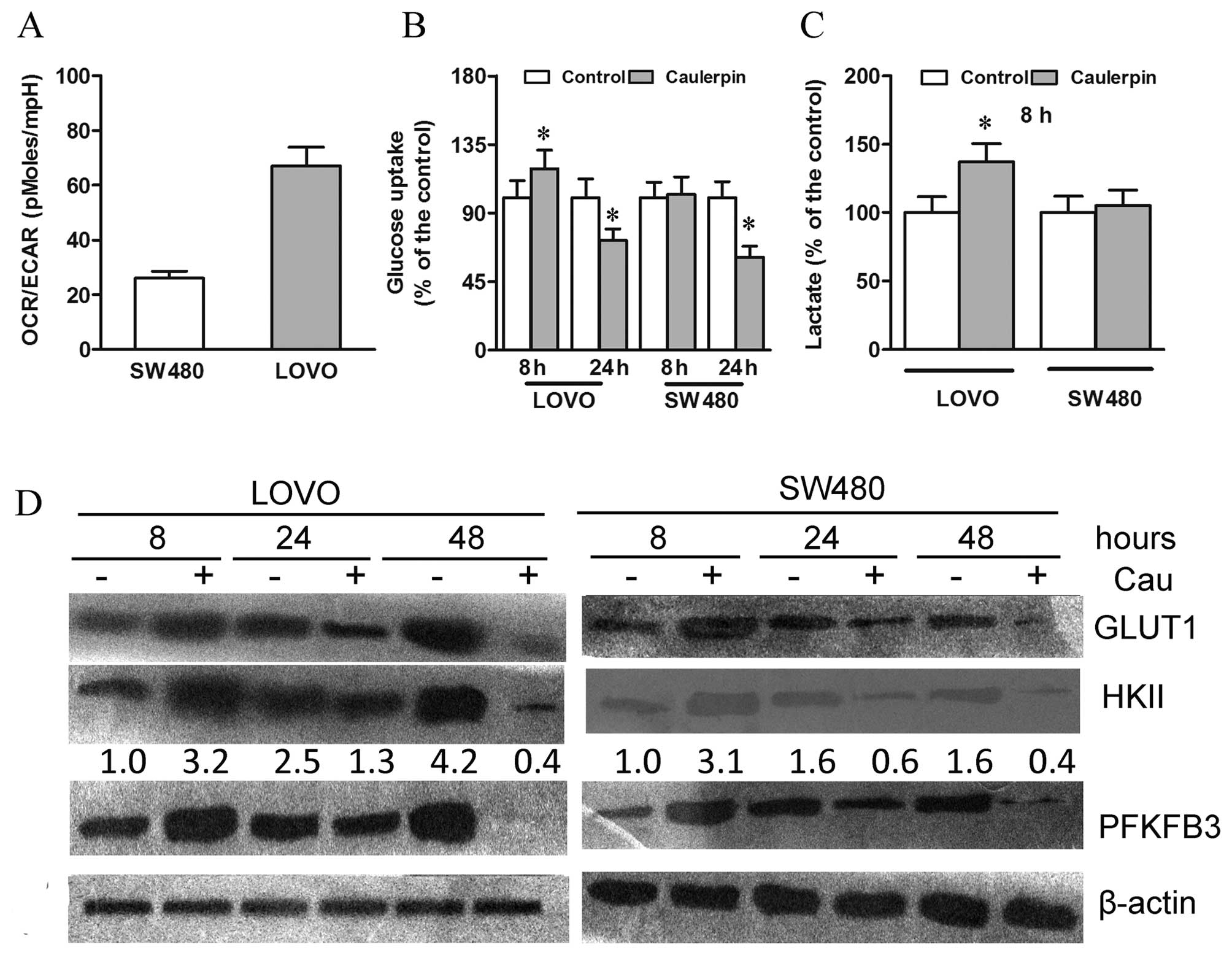

Caulerpin exhibits different early and

long-term effects on glycolysis

As a direct measure of ECAR, lactic acid was

secreted by cells and thus serving as a hint for glycolytic

activity. The baseline OCR/ECAR ratio was low in the SW480 cells

and high in the LOVO cells, indicating a higher intrinsic

glycolytic rate in SW480 cells than LOVO cells, which generate ATP

primarily through OXPHOS (Fig.

6A).

We further examined whether caulerpin-triggered

OXPHOS attenuation altered cell glucose metabolism. After 8 h

treatment with caulerpin, glycolysis in LOVO cells was strengthened

to compensate ATP loss, as revealed by significant increases in

glucose uptake and lactate production (Fig. 6B and C). Moreover, upregulation of

GLUT1, HKII, and 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB3) protein

expression was also observed (Fig.

6D). Nevertheless, a prolonged exposure to caulerpin,

unexpectedly, weakened glucose uptake in LOVO cells, as evidenced

by downregulation of GLUT1 level after 48 h of caulerpin incubation

(Fig. 6B and D). In the highly

glycolytic SW480 cells, 8 h treatment with caulerpin exerted no

significant effect on glucose metabolism; on the other hand, a

remarkable decline of GLUT1 protein expression was observed after

24 h and continued after 48 h. Therefore, in spite of the initial

attempt to adapt to the energy stress, long-term incubation with

caulerpin eventually elicited a notable impairment to glucose

metabolism.

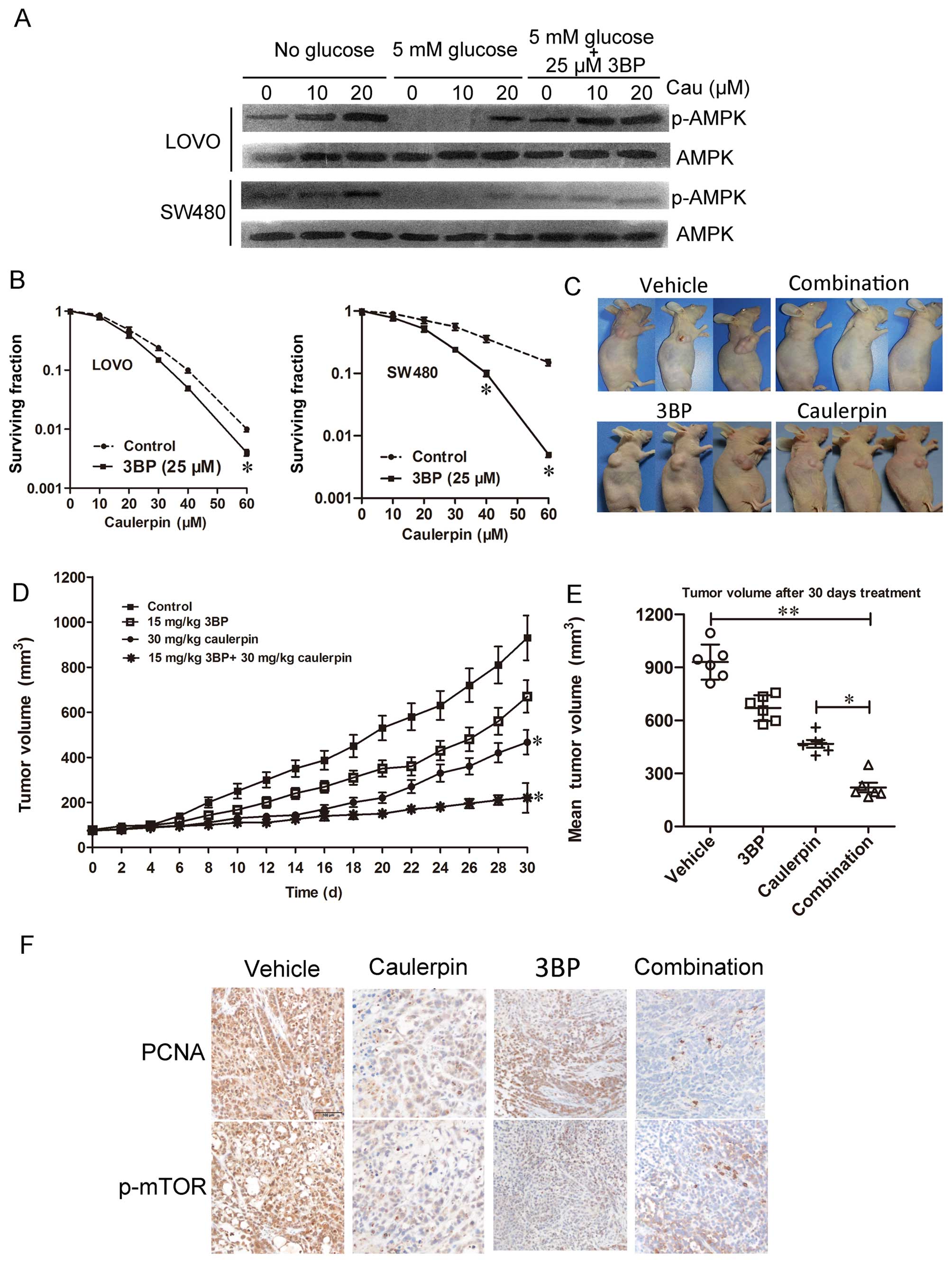

Synergistic effect of caulerpin combined

with glycolysis inhibitors

To further characterize the biochemical events

elicited by caulerpin and to examine its combination with the

glycolytic inhibitor, we investigated nutrient signaling events and

the AMPK kinase pathway. Glucose withdrawal promoted AMPK

activation in both cell lines. Interestingly, levels of p-AMPK is

higher in cells co-treated with caulerpin, 3BP (25 µM) and

glucose than cells treated with glucose only. These data emphasized

the key role of the glycolytic switch for compensating ATP

generation during caulerpin incubation (Fig. 7A). In Fig. 7B, in vitro CCK-8 assays were

applied to examine the cell viability. The IC50 of 3BP

is 41.2±1.6 and 38.9±1.6 µM for LOVO and SW480 cells,

respectively. As can be seen from the surviving factions, the

viability of cells treated with 3BP (25 µM) + caulerpin (60

µM) was significantly lower than cells treated with 3BP or

caulerpin alone. The combination index of 3BP (25 µM) +

caulerpin (60 µM) is 0.67 for LOVO cells and 0.21 for SW480

cells, suggesting a synergistic effect. When CI is >1, it means

antagonism. So we concluded that caulerpin plus 3BP may act

synergistically in inhibiting cellular proliferation in

vitro (Table I).

| Table ICalcusyn analysis reveals synergistic

or antagonistic interactions between caulerpin and 3BP in CRC

cells. |

Table I

Calcusyn analysis reveals synergistic

or antagonistic interactions between caulerpin and 3BP in CRC

cells.

| Caulerpin

(µM) | 3BP

(µM) | Combination index

(CI)

|

|---|

| LOVO | SW480 |

|---|

| 20 | 25 | 1.43 | 1.38 |

| 40 | 25 | 1.02 | 0.68 |

| 60 | 25 | 0.67 | 0.21 |

To further assess the antitumor efficiency of the

combination in vivo, athymic nude mouse model bearing SW480

implanted xenografts were treated with control, 3BP, caulerpin, or

a combination of both agents. Tumor growth was slower in caulerpin

monotherapy group than the vehicle group. No significant difference

was observed in tumor size between mice treated with saline and

3BP. However, the combination of 3BP with caulerpin displayed

remarkable tumor regression (Fig.

7C). Tumor xenograft sections were subjected to

immunohistochemical analysis for p-mTOR and PCNA, which is an

indicator for cell proliferation. PCNA and p-mTOR was significantly

inhibited in combined treatment of 3BP with caulerpin (Fig. 7F).

Discussion

Cancer cell metabolism depends on a delicate balance

between oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. The former keeps

active to sustain energy needs required by the tumor, while the

latter extensively enlarged to afford the needs of an invasive and

rapid tumor growth (30).

Recently, new therapeutic approaches that target multiple

bioenergetics pathways have emerged. Interference with this unique

metabolic setting may provide novel opportunities for targeted

anticancer therapy.

Here, we focused on the energy regulating effect of

caulerpin, a mitochondrial ETC inhibitor. The obvious function

included the inhibition of OXPHOS, the loss of MMP, and the rise of

ROS in colorectal cancer cells. Although longtime treatment would

finally drive cells to death, a cell reprogramming towards

glycolysis largely attenuated the effect of caulerpin on cell death

in the initial few hours after caulerpin treatment. Given that

glycolysis triggered by caulerpin was a compensatory response, we

reasoned that combination with glycolysis inhibitors may reinforce

the anticancer effect of caulerpin. The marked increase in

caulerpin-induced AMPK activation by the glycolysis inhibitor 3BP

or by glucose deprivation evidently proves the above conclusion.

The enhancement of caulerpin sensitivity by 3BP was also confirmed

in the LOVO xenograft model, suggesting a key role of caulerpin in

energy metabolism-based combinational therapies.

As a crucial metabolic organelle during

carcinogenesis, mitochondria is regarded as a target for anticancer

therapy (4). Mostly, cancer cells

produce ATP via mitochondrial metabolism fueled by fatty acids and

amino acids (31). Furthermore,

mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is also required to sustain the

redox balance. Specifically, ATP generation associated with ROS

formation via complex I/III of the ETC (32). It is know that pro-tumorigenicity

is a key characteristic of ROS. When the generation of ROS

surpasses the intracellular clearance of ROS, cell-toxic oxidative

stress will be stimulated. ETC complex I, constitutes the entry

point of electrons and is an essential site for ROS generation

(33). Caulerpin has been reported

to reduce respiratory complex II activity and to exhibit

cytotoxicity to human dermal fibroblasts (14). In this study, caulerpin

considerably reduced oxygen consumption rate and ATP level in both

SW480 and LOVO cells, accompanied by an elevation in ROS.

Mitochondria isolated from rat liver have been selected as a system

in which mechanisms of bioenergetics are not altered (14). Therefore, liver mitochondrial and

LOVO cells were used to explore the complex interactions between

caulerpin and the organelle. Studies showed that complex I

inhibition by biguanides, such as phenformin and metformin,

suppressed cancer development in vitro and in vivo

(34,35). However, the effective inhibiting

concentrations of biguanides reached ~50 mM, with the

IC50 of caulerpin ranging from 20–31 µM. We found

that in the media containing malate and glutamate (substrates of

complex I), caulerpin treatment caused diminution of OCR, but

similar results were not obtained in the presence of succinate

(substrates of complex I), emphasizing the essential role of

complex I in the inhibitory effect of caulerpin.

Dynamic changes in mitochondria are closely

connected with post-translational modifications mediated by

metabolic sensors, such as SIRT1 and AMPK (36). Among them, AMPK acts as a

fuel-sensor that plays a vital role in manipulating bioenergetics

metabolism in both normal and malignant cells (37). Under conditions of metabolic

stress, activated AMPK will keep energy homeostasis by dampening

energy consuming (anabolic) pathways and strengthening energy

producing (catabolic) pathways to restore the loss of cellular ATP

and de-energization (38).

Caulerpin inhibited OXPHOS, accompanied by the decline of ATP

content and concomitant activation of the energy sensor AMPK. Once

activated, AMPK will promote glycolysis to replenish the loss of

ATP. In this study, in both LOVO and SW480 cells, the level of

p-AMPK was highest at 30 min after caulerpin treatment. We

hypothesized that OXPHOS was significantly inhibited by caulerpin,

and after 30 min, glycolysis was activated to some content to

counterbalance the loss of ATP. Therefore, the level of p-AMPK

increased during the initial 30 min and decreased since 60 min.

AMPK activation by caulerpin was dependent on CAMKK2, an upstream

effector of AMPK. In detail, AMPKα1 was demonstrated to mediate the

function of caulerpin, since crspAMPKα1 protected cells against

caulerpin-induced cytotoxicity and attenuated caulerpin-induced

activation of mTOR pathway. But siAMPKα2 failed to exhibit

impressive effect on cell death-induced by caulerpin treatment.

Likewise, AMPKα1-shRNA has been proved to improve mTORC1

phosphorylation in colorectal cancer cells (39). Herein, we concluded that AMPK

isoforms differentially regulated survival in response to caulerpin

treatment.

Under energy stress, activated AMPK can further

inhibit mTOR signaling for cellular adaptation in a stress

condition (28). Several groups

found that AMPK directly phosphorylated multiple components, such

as TSC2 in the mTORC1 pathway (40). Consistently, either AICAR (an AMPK

activator) or glucose withdrawal greatly attenuated mTORC1 activity

in TSC2-deficient cells (41). The

p70S6K and eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), which can be

phosphorylated by the mTOR complex, facilitate protein synthesis.

The p70S6K regulates sterol synthesis and switches glucose

metabolism from glycolysis to pentose phosphate pathway in cancer

cells (42). In the present study,

caulerpin triggered AMPK phosphorylation and further inhibited the

mTORC1/4E-BP1 axis.

Heightened glycolysis is a major cancer hallmark.

Firstly, we compared the basal metabolic profiles between LOVO and

SW480 CRC cells. OCR/ECAR ratio of LOVO cells was significantly

higher than that of SW480 cell, indicating that SW480 cells were

highly glycolytic, while LOVO was a less glycolytic cell line which

depended more on OXPHOS to produce ATP. This result could partially

explain why IC50 in LOVO cells is lower than SW480 cells

in response to caulerpin treatment, which was a potent inhibitor of

mitochondrial respiration. Moreover, mRNA of Transketolase-like

(TKTL)1, one of the key enzymes in glycolysis, was heterogeneously

expressed, with high level in SW480 cells but very low level in

LOVO cells (43,44). HKII is a rate-limiting enzyme in

glycolysis, thus giving rise to ATP decline and cell death. In

colon cancer cells, knockdown of HKII suppressed proliferation,

glycolysis, and lactate production under both normoxic and hypoxic

conditions (45). In this study,

distinguished effect was observed at different time-points after

caulerpin treatment. Glycolysis was enhanced in the initial hours

after treatment with caulerpin in LOVO cells rather than SW480

cells. However, long-term treatment of caulerpin considerably

inactivated mTOR pathway, thus causing cell death in both LOVO and

SW480 cells. GLUT1, HKII and PFKFB3 levels were weakened after 48 h

of caulerpin incubation.

Recently, combined treatment targeting both

glycolysis and mitochondria function emerges as an interesting

alternative for cancer therapy. Mitochondrial ETC blockers have

been reported to facilitate 2DG-induced oxidative stress and cell

killing effect in human colon carcinoma cells (46). In a phase I dose-escalation trial,

the recommended dose of 2DG in combination with weekly docetaxel is

63 mg/kg/day with tolerable adverse effects (47). The most noteworthy side effects at

this trial were reversible hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal bleeding

and reversible grade 3 QTc prolongation (47). 3BP is a small-molecule pyruvate

mimetic and anticancer drug, and its biological activity is

attributed to alkylation of free thiol groups on the cysteine

residues of proteins (48). 3BP

directly inhibits mitochondrial bound HKII. The combination of

caulerpin and 3BP retarded tumor growth in nude mice inoculated

with SW480 cells, along with a decrement of PCNA and mTOR

expression in IHC assays, showing the key role of AMPK/mTOR pathway

in the anticancer activity of caulerpin.

The present study provided a preliminary insight

into the potential use of caulerpin for the treatment of human

colorectal cancer. Only transplanted nude mice model with

xenografts was applied in our study to investigate the anticancer

efficiency of caulerpin plus 3BP. Orthotopic CRC model can also be

used in the future to verify the synergistical effect. In this

study, we demonstrated that caulerpin disturbed the mitochondrial

function mainly via inhibiting mTORC1-4E-BP1 axis. However,

knocking out of AMPKα1 did not lead to a total abolishment of

caulerpin-elicited cytotoxicity on LOVO cells. Moreover, the

broad-range caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk only partially prevented

cell death. Therefore, it is reasonable that other pathways are

also involved in the actions by caulerpin in CRC cells. Thus, it is

valuable to further uncover the interactions between AMPK signaling

and other possible pathways in mediating the effects of caulerpin

on colorectal carcinoma or other cancer models.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Municipal key

disciplines of Ningbo (no. 2013001) and the Natural Science

Foundation of Ningbo (nos. 2014A610225 and 2016A610135).

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

OXPHOS

|

oxidative phosphorylation

|

|

ETC

|

electron transport chain

|

|

AMPK

|

AMP-activated protein kinase

|

|

CaMKK2

|

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein

kinase 2

|

|

GLUT1

|

glucose transporter 1

|

|

HKII

|

hexokinase II

|

|

PFKFB3

|

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase

|

|

2DG

|

2-deoxy-D-glucose

|

|

3BP

|

3-bromopyruvate

|

|

MMP

|

mitochondrial membrane potential

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

PBS

|

phosphate-buffered saline

|

|

OCR

|

oxygen consumption rate

|

|

ECAR

|

extracellular acidification rate

|

|

sgRNA

|

single guide RNA

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel R, Desantis C and Jemal A:

Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 64:104–117.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Warburg O, Wind F and Negelein E: The

metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 8:519–530. 1927.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ward PS and Thompson CB: Metabolic

reprogramming: A cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate.

Cancer Cell. 21:297–308. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wheaton WW, Weinberg SE, Hamanaka RB,

Soberanes S, Sullivan LB, Anso E, Glasauer A, Dufour E, Mutlu GM,

Budigner GS, et al: Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I of

cancer cells to reduce tumorigenesis. eLife. 3:e022422014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Inoki K, Kim J and Guan KL: AMPK and mTOR

in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol

Toxicol. 52:381–400. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Sinha RA, Singh BK, Zhou J, Wu Y, Farah

BL, Ohba K, Lesmana R, Gooding J, Bay BH and Yen PM: Thyroid

hormone induction of mitochondrial activity is coupled to mitophagy

via ROS-AMPK-ULK1 signaling. Autophagy. 11:1341–1357. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wu XB, Liu Y, Wang GH, Xu X, Cai Y, Wang

HY, Li YQ, Meng HF, Dai F and Jin JD: Mesenchymal stem cells

promote colorectal cancer progression through AMPK/mTOR-mediated

NF-κB activation. Sci Rep. 6:214202016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang YJ, Dai Q, Sun DF, Xiong H, Tian XQ,

Gao FH, Xu MH, Chen GQ, Han ZG and Fang JY: mTOR signaling pathway

is a target for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol.

16:2617–2628. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

He X, Lin X, Cai M, Zheng X, Lian L, Fan

D, Wu X, Lan P and Wang J: Overexpression of Hexokinase 1 as a poor

prognosticator in human colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol.

37:3887–3895. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hamabe A, Yamamoto H, Konno M, Uemura M,

Nishimura J, Hata T, Takemasa I, Mizushima T, Nishida N, Kawamoto

K, et al: Combined evaluation of hexokinase 2 and phosphorylated

pyruvate dehydrogenase-E1α in invasive front lesions of colorectal

tumors predicts cancer metabolism and patient prognosis. Cancer

Sci. 105:1100–1108. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gandham SK, Talekar M, Singh A and Amiji

MM: Inhibition of hexokinase-2 with targeted liposomal

3-bromopyruvate in an ovarian tumor spheroid model of aerobic

glycolysis. Int J Nanomedicine. 10:4405–4423. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xintaropoulou C, Ward C, Wise A, Marston

H, Turnbull A and Langdon SP: A comparative analysis of inhibitors

of the glycolysis pathway in breast and ovarian cancer cell line

models. Oncotarget. 6:25677–25695. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu Y, Morgan JB, Coothankandaswamy V, Liu

R, Jekabsons MB, Mahdi F, Nagle DG and Zhou YD: The Caulerpa

pigment caulerpin inhibits HIF-1 activation and mitochondrial

respiration. J Nat Prod. 72:2104–2109. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ferramosca A, Conte A, Guerra F, Felline

S, Rimoli MG, Mollo E, Zara V and Terlizzi A: Metabolites from

invasive pests inhibit mitochondrial complex II: A potential

strategy for the treatment of human ovarian carcinoma? Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 473:1133–1138. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Graham NA, Tahmasian M, Kohli B,

Komisopoulou E, Zhu M, Vivanco I, Teitell MA, Wu H, Ribas A, Lo RS,

et al: Glucose deprivation activates a metabolic and signaling

amplification loop leading to cell death. Mol Syst Biol. 8:5892012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Priebe A, Tan L, Wahl H, Kueck A, He G,

Kwok R, Opipari A and Liu JR: Glucose deprivation activates AMPK

and induces cell death through modulation of Akt in ovarian cancer

cells. Gynecol Oncol. 122:389–395. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen Y, Qing W, Sun M, Lv L, Guo D and

Jiang Y: Melatonin protects hepatocytes against bile acid-induced

mitochondrial oxidative stress via the AMPK-SIRT3-SOD2 pathway.

Free Radic Res. 49:1275–1284. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang SY, Wei YH, Shieh DB, Lin LL, Cheng

SP, Wang PW and Chuang JH: 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose can complement

doxorubicin and sorafenib to suppress the growth of papillary

thyroid carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 10:e01309592015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wei L, Zhou Y, Dai Q, Qiao C, Zhao L, Hui

H, Lu N and Guo QL: Oroxylin A induces dissociation of hexokinase

II from the mitochondria and inhibits glycolysis by SIRT3-mediated

deacetylation of cyclophilin D in breast carcinoma. Cell Death Dis.

4:e6012013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jeong SM, Lee J, Finley LW, Schmidt PJ,

Fleming MD and Haigis MC: SIRT3 regulates cellular iron metabolism

and cancer growth by repressing iron regulatory protein 1.

Oncogene. 34:2115–2124. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Song J, Feng L, Zhong R, Xia Z, Zhang L,

Cui L, Yan H, Jia X and Zhang Z: Icariside II inhibits the EMT of

NSCLC cells in inflammatory microenvironment via down-regulation of

Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Carcinog. Feb 9–2016.Epub ahead of

print.

|

|

22

|

Liu Y, Veena CK, Morgan JB, Mohammed KA,

Jekabsons MB, Nagle DG and Zhou YD: Methylalpinum isoflavone

inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) activation by

simultaneously targeting multiple pathways. J Biol Chem.

284:5859–5868. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

23

|

Bonifati S, Daly MB, St Gelais C, Kim SH,

Hollenbaugh JA, Shepard C, Kennedy EM, Kim DH, Schinazi RF, Kim B,

et al: SAMHD1 controls cell cycle status, apoptosis and HIV-1

infection in monocytic THP-1 cells. Virology. 495:92–100. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhou X, Chen M, Zeng X, Yang J, Deng H, Yi

L and Mi MT: Resveratrol regulates mitochondrial reactive oxygen

species homeostasis through Sirt3 signaling pathway in human

vascular endothelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 5:e15762014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang W, Tong D, Liu F, Li D, Li J, Cheng

X and Wang Z: RPS7 inhibits colorectal cancer growth via decreasing

HIF-1α-mediated glycolysis. Oncotarget. 7:5800–5814.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yamada C, Aikawa T, Okuno E, Miyagawa K,

Amano K, Takahata S, Kimata M, Okura M, Iida S and Kogo M: TGF-β in

jaw tumor fluids induces RANKL expression in stromal fibroblasts.

Int J Oncol. 49:499–508. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang M, Dong Y, Xu J, Xie Z, Wu Y, Song

P, Guzman M, Wu J and Zou MH: Thromboxane receptor activates the

AMP-activated protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells via

hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res. 102:328–337. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Hardie DG, Ross FA and Hawley SA: AMPK: A

nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 13:251–262. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Luczak ED and Anderson ME: CaMKII

oxidative activation and the pathogenesis of cardiac disease. J Mol

Cell Cardiol. 73:112–116. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Dang CV: Links between metabolism and

cancer. Genes Dev. 26:877–890. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hensley CT, Wasti AT and DeBerardinis RJ:

Glutamine and cancer: Cell biology, physiology, and clinical

opportunities. J Clin Invest. 123:3678–3684. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Willems PH, Rossignol R, Dieteren CE,

Murphy MP and Koopman WJ: Redox homeostasis and mitochondrial

dynamics. Cell Metab. 22:207–218. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Murphy MP: How mitochondria produce

reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 417:1–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Pollak M: Overcoming drug development

bottlenecks with repurposing: Repurposing biguanides to target

energy metabolism for cancer treatment. Nat Med. 20:591–593. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Birsoy K, Possemato R, Lorbeer FK,

Bayraktar EC, Thiru P, Yucel B, Wang T, Chen WW, Clish CB and

Sabatini DM: Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to

glucose limitation and biguanides. Nature. 508:108–112. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Duarte FV, Amorim JA, Palmeira CM and Rolo

AP: Regulation of mitochondrial function and its impact in

metabolic stress. Curr Med Chem. 22:2468–2479. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Shackelford DB and Shaw RJ: The LKB1-AMPK

pathway: Metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat

Rev Cancer. 9:563–575. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fennema E, Rivron N, Rouwkema J, van

Blitterswijk C and de Boer J: Spheroid culture as a tool for

creating 3D complex tissues. Trends Biotechnol. 31:108–115. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lu PH, Chen MB, Ji C, Li WT, Wei MX and Wu

MH: Aqueous Oldenlandia diffusa extracts inhibits colorectal cancer

cells via activating AMP-activated protein kinase signalings.

Oncotarget. Jun 13–2016.Epub ahead of print.

|

|

40

|

Inoki K, Zhu T and Guan KL: TSC2 mediates

cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell.

115:577–590. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wolff NC, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Xie XJ,

Castrillon DH, Kabbani W and Brugarolas J: Cell-type-dependent

regulation of mTORC1 by REDD1 and the tumor suppressors TSC1/TSC2

and LKB1 in response to hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 31:1870–1884. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Düvel K, Yecies JL, Menon S, Raman P,

Lipovsky AI, Souza AL, Triantafellow E, Ma Q, Gorski R, Cleaver S,

et al: Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream

of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell. 39:171–183. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Fanciulli M, Bruno T, Giovannelli A,

Gentile FP, Di Padova M, Rubiu O and Floridi A: Energy metabolism

of human LoVo colon carcinoma cells: Correlation to drug resistance

and influence of lonidamine. Clin Cancer Res. 6:1590–1597.

2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bentz S, Cee A, Endlicher E, Wojtal KA,

Naami A, Pesch T, Lang S, Schubert P, Fried M, Weber A, et al:

Hypoxia induces the expression of transketolase-like 1 in human

colorectal cancer. Digestion. 88:182–192. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Qin Y, Cheng C, Lu H and Wang Y: miR-4458

suppresses glycolysis and lactate production by directly targeting

hexokinase2 in colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

469:37–43. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Fath MA, Diers AR, Aykin-Burns N, Simons

AL, Hua L and Spitz DR: Mitochondrial electron transport chain

blockers enhance 2-deoxy-D-glucose induced oxidative stress and

cell killing in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther.

8:1228–1236. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Raez LE, Papadopoulos K, Ricart AD,

Chiorean EG, Dipaola RS, Stein MN, Rocha Lima CM, Schlesselman JJ,

Tolba K, Langmuir VK, et al: A phase I dose-escalation trial of

2-deoxy-D-glucose alone or combined with docetaxel in patients with

advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 71:523–530.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Ko YH, Verhoeven HA, Lee MJ, Corbin DJ,

Vogl TJ and Pedersen PL: A translational study 'case report' on the

small molecule 'energy blocker' 3-bromopyruvate (3BP) as a potent

anticancer agent: From bench side to bedside. J Bioenerg Biomembr.

44:163–170. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|