Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed

type of cancer in women, accounting for one in eight cancer

diagnoses globally, with >2,000,000 new breast cancer cases

diagnosed and 685,000 breast cancer-associated deaths recorded in

2020 (1). Due to population growth

and aging alone, the global burden of breast cancer is expected to

increase to >3,000,000 new cases and >1,000,000 deaths by

2040 (2). Notably, there has been

a significant decrease in the breast cancer-related death rate over

the years, with an overall decline of 43% in 2020 compared with in

1989 (1); however, this decline

has slowed slightly in recent years. This decrease has been due to

advances in treatment and earlier disease detection through

screening. An improved understanding of the biological

heterogeneity of breast cancer has also led to advances in the

effective and personalized approach of molecular targeted therapies

(2).

Based on the expression of hormone receptors (HRs)

and growth factor receptors, breast cancer is categorized into

distinct molecular subtypes: Luminal A [HR+ and human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2−)]; luminal B

(HR+/HER2+); HER2+/HR−;

and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC;

HR−/HER2−) (3). Globally, of patients with breast

cancer, 83% have HR+ subtypes; of which 71% are luminal

A and 12% are luminal B (4). The

luminal A subgroup is less aggressive, more responsive to hormonal

interventions and has a better prognosis compared with the luminal

B subgroup, which is further defined by its high expression of the

proliferation marker antigen Ki67 and HER2+. The

HER2+ subtype has high expression of the HER2 oncogene;

thus, anti-HER2 therapies may be used for treatment. Globally, the

HER2+ subgroup accounts for only 5% of patients with

breast cancer, while the remaining 12% of the total patient

population has the TNBC subtype (4). Due to the absence of molecular

targets, such as overexpression of hormone receptors and HER2, TNBC

is more difficult to treat than other subtypes of breast cancer

(5).

Clinical classification of breast cancer informs the

choice of treatment. In women with advanced or metastatic estrogen

receptor (ER)+ and HER2− breast cancer,

palbociclib and abemaciclib were recently approved by the United

States Food and Drug Administration for their use in combination

with hormone therapy. In addition, alspelisib has been approved as

combination therapy with hormonal therapy for the treatment of

HR+ and HER2− breast cancer with

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α

(PIK3CA) gene mutations (6). Trastuzumab and pertuzumab are target

therapies selected for the treatment of HER2+ breast

cancer. Additionally, trastuzumab has been used in the prevention

of relapsed early-stage HER2+ breast cancer.

Chemotherapy is the main treatment for TNBC due to its lack of

expression of both HRs and HER2; therefore, patients with this type

of cancer do not exhibit a response to targeted therapies (7). Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab are

some of the immunotherapy drugs recommended for use in patients

with metastatic TNBC with tumors expressing programmed death ligand

1 (PD-L1). PARP inhibitor drugs, including olaparib and

talazoparib, have been used as targeted therapies for TNBC caused

by inherited breast cancer gene (BRCA) alterations (8).

Several biomarkers for the diagnosis, prognostic

prediction and treatment selection of breast cancer have been

developed. These include HRs, HER2 and multigene tests, such as

Oncotype DX, EndoPredict, MammaPrint and Prosigna (9). Breast cancer biomarkers are

constantly evolving from the conventional biomarkers used in

immunohistochemistry, such as ER, progesterone receptor (PR) and

HER2, to genetic biomarkers with therapeutic implications, such as

BRCA1/2, ER, HER2, PIK3CA and neurotrophic tyrosine receptor

kinase gene mutations, and microsatellite instability (10). Additionally, immunomarkers, such as

PD-L1, are being employed. While these biomarkers have been

developed, they are still limited in their specificity and clinical

efficacy (11). Therefore, it is

crucial to develop targeted molecular therapies with high accuracy

and easily measurable companion diagnostics.

In a preliminary study, target screening for the

diagnosis and treatment of cancer was performed by gene expression

profile analyses, followed by tissue microarray analyses of solid

breast cancer and normal tissues (Fig. S1). Several oncoantigens that were

related to carcinogenesis and cancer development have previously

been isolated using this screening process (12–32).

Following target screening shown in Fig. S1, the present study identified

kinesin family member 20B [KIF20B, also known as M-phase

phosphoprotein 1 (MPHOSPH1)] as a candidate molecular target that

was frequently and highly expressed in breast cancer. KIF20B

belongs to the kinesin superfamily, which possesses a highly

conserved motor domain, the ATPase activity of which enables it to

undergo microtubule-dependent plus-end movement. As a

microtubule-associated protein, KIF20B is important for cytokinesis

(33). There has been increasing

evidence of high expression levels of kinesin family proteins in

cancer, suggesting that, in addition to their normal physiological

cell function, their upregulation may have oncogenic potential in

some types of cancer. Previous reports have suggested that

KIF20B is highly expressed in some types of human cancer,

including hepatocellular carcinoma, bladder, colorectal, pancreatic

and tongue cancer (34–38); however, to the best of our

knowledge, there has been no detailed investigation on the function

of KIF20B in tumorigenesis, and its value as a therapeutic and

diagnostic target of various subtypes of breast cancer. This

prompted an investigation into the possible role of KIF20B in the

development of breast cancer. Therefore, the present study reveals

the functional role of KIF20B in breast cancer development, and

demonstrates its value as a therapeutic target and prognostic

biomarker.

Materials and methods

Breast cancer cell lines and clinical

tissue samples

The present study used eight breast cancer cell

lines (T-47D, ZR-75-1, MCF7, AU565, SK-BR-3, HCC1599, HCC1937 and

MDA-MB-468), which were commercially purchased. Normal primary

human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) were also commercially

purchased and the use of primary human cells was approved by the

ethics committee. The features of all cells are described in

Table I. RPMI-1640 (FUJIFILM Wako

Pure Chemical Corporation), EMEM (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical

Corporation), McCoy's 5A (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and Leibovitz's L-15 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) media

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) were prepared and the cells were cultured in

monolayers. The cells were incubated at 37°C in an incubator

containing 5% CO2, with the exception of the MDA-MB-468

cells, which required 0% CO2 incubation. HMECs were

maintained in Mammary Epithelial Cell Basal Medium (cat. no.

PCS-600-030) supplemented with Mammary Epithelial Cell Growth Kit

(cat. no. PCS-600-040) (both from American Type Culture

Collection).

| Table I.Human breast cancer cell lines and

normal breast cells. |

Table I.

Human breast cancer cell lines and

normal breast cells.

| Cell line | Histology | Subtype | Medium | Catalog no. |

|---|

| T-47D | Ductal

carcinoma | Luminal A | RPMI-1640 | HTB-133 |

| ZR-75-1 | Ductal

carcinoma | Luminal B | RPMI-1640 | CRL-1500 |

| MCF7 | Adenocarcinoma | Luminal A | EMEM | HTB-22 |

| AU565 | Adenocarcinoma |

HER2+ | RPMI-1640 | CRL-2351 |

| SK-BR-3 | Adenocarcinoma |

HER2+ | McCoy's 5A | HTB-30 |

| HCC1599 | Ductal

carcinoma | TNBC | RPMI-1640 | CRL-2331 |

| HCC1937 | Primary ductal

carcinoma | TNBC | RPMI-1640 | CRL-2336 |

| MDA-MB-468 | Adenocarcinoma | TNBC | Leibovitz's

L-15 | HTB-132 |

| HMECs | Normal breast | N/A | Mammary epithelial

cell basal medium | PCS-600-030 |

For reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR), 15 breast tumor samples and three normal breast tissue

samples were collected between June 2005 and April 2010 from

patients who provided written informed consent at Kanagawa Cancer

Center (Yokohama, Japan) (Table

SI). The pathologist confirmed that the obtained normal tissues

were non-neoplastic and were not contaminated with tumor cells.

The use of the tissues was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Kanagawa Cancer Center (approval date: June 8, 2005).

In addition, 251 formalin-fixed primary breast cancer tissues and

adjacent healthy tissues were obtained from Japanese female

patients (median age, 65 years; range, 28–89 years) from Kanagawa

Cancer Center for tissue microarray generation. The clinical stage

of the breast cancer samples was determined according to the Union

for International Cancer Control TNM classification 7th Edition

(39). The project to establish

tumor tissue microarrays from archival formalin-fixed and

paraffin-embedded, surgically obtained tissues and to use the

tissue microarrays for later researches was approved by the

Kanagawa Cancer Center Ethics Committee (approval no. Rin-177;

Yokohama, Japan). The patients whose tissues were used to generate

the breast cancer tissue microarrays received surgery at Kanagawa

Cancer Center Hospital between January 2004 and March 2006. Written

informed consent was obtained from the patients for the use of

their clinical information and for specimens remaining after

clinical examinations, such as archival formalin-fixed and

paraffin-embedded specimens. The ethics committee at Shiga

University of Medical Science (approval no. 21-163) approved the

present study including the use of all aforementioned clinical

materials.

RT-qPCR

Maxwell® 16 LEV simplyRNA Cells and

Tissue kits (Promega Corporation) were used to extract total RNA

from the cultured cells and clinical tissues according to the

manufacturer's protocol. PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Bio,

Inc.) was used to synthesize cDNA from total RNA according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 15

min and 85°C for 5 sec. mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR

analysis using TaqMan® Fast Universal PCR Master Mix

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and QuantStudio™ 3

Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the

assays, KIF20B (assay ID Hs01027505_m1) primers were used,

and β-actin (ACTB; assay ID Hs01060665_g1) (both from Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used as a control. All experiments

were performed in triplicate. The thermal cycling conditions were

as follows: Initial denaturation for 20 sec at 95°C, followed by 40

cycles at 95°C for 1 sec and 60°C for 20 sec. Using the

2−ΔΔCq method (40) and

with ACTB mRNA expression as a reference, KIF20B mRNA

expression levels were quantified.

Western blot analysis

Cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used to

wash the cells, and RIPA buffer (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) containing a 1% protease inhibitor cocktail was used to lyse

the cells. After homogenization, lysates were incubated at 4°C for

30 min, and the supernatant was centrifuged at 20,400 × g for 15

min at 4°C to separate proteins from debris. The DC Protein assay

kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to measure total

protein concentration. A sample buffer containing SDS was then

added to the proteins, boiled for 5 min at 100°C and then incubated

at room temperature for 5 min. Using Mini-Protean® TGX

7.5% precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), proteins were

electrophoresed and transferred onto Trans-Blot® Turbo

0.2 µm polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (cat. no. 1704156;

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The membranes were blocked in 5%

nonfat dried milk in 1X TBS-0.05% Tween 20 (cat. no. 9997; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C, after which they were

incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-KIF20B antibody (1:200; cat.

no. ab122165; Abcam) or anti-ACTB antibody (1:2,000; cat. no.

12262S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C.

Membranes were then incubated with anti-rabbit horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2,000; cat. no.

NA934; Cytiva) for 1 h at room temperature. A Fusion Solo S system

(Vilber Lourmat) was used to visualize protein bands with

chemiluminescence western blotting detection reagents (cat no.

RPN2232; Cytiva).

Immunocytochemistry

Cells (5.0×103 cells/well) were seeded

onto an 8-well Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Nalge Nunc

International]. The cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution

for 15 min at room temperature, washed and then permeabilized using

PBS (−) containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 2 min at room temperature.

Thereafter, they were blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA;

FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) in PBS (−) for 30 min at

4°C. The cells were then incubated with the rabbit polyclonal

anti-KIF20B antibody (1:100; cat. no. ab122165; Abcam) in PBS (−)

containing 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20 at 4°C overnight. After washing

with PBS (−), the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor®

488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:800; cat.

no. A11008; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a wet chamber for 90

min at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with VECTASHIELD

Antifade Mounting Medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories,

Inc.) and visualized with a confocal laser scanning microscope

(Leica TCS SP8 X; Leica Microsystems, Inc.).

Immunohistochemistry and tissue

microarray analysis

Tumor tissue microarrays were constructed according

to a previously published process (13). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

breast cancer tissues and normal tissues were obtained from the

Kanagawa Cancer Center. A visually aligned section of hematoxylin-

and eosin-stained tissue was used to select the areas for sampling.

Slides for tissue microarrays were deparaffinized in xylene and

rehydrated in graded concentrations of ethanol. Target Retrieval

Solution (pH 9) (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was used in a

microwave oven for heat-induced antigen retrieval. After blocking

endogenous peroxidase activity with a 0.3% hydrogen

peroxide/methanol mixture and nonspecific protein binding sites

with protein blocking buffer (cat. no. X0909; Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.), the sections were incubated with anti-KIF20B

antibody (1:200; cat. no. ab122165; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After

primary antibody incubation, sections were incubated at room

temperature for 30 min with polymer anti-rabbit secondary

antibodies labeled with EnVision+System-HRP (cat. no. K4003; Dako;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Specimens were counterstained at room

temperature with hematoxylin for 1 min, after being incubated with

3,3′-DAB chromogen and DAB substrate buffer. Since the staining

intensity within each tumor tissue core was mostly homogenous, the

semi-quantitative evaluation of KIF20B staining intensity was

performed by three independent investigators. The expression

patterns of KIF20B in tissue arrays were classified from

absent/weak to strong. Images of the immunostained samples were

acquired with a NanoZoomer whole slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics

K.K.) and positivity of the KIF20B protein was semi-quantitatively

analyzed (30,32) by three independent investigators

without prior knowledge of the clinicopathological data. Since the

intensity of staining within each tumor tissue core was mostly

homogeneous, the staining intensity for KIF20B was recorded as

strong positive, weak positive or negative. The staining patterns

were defined as strong positive if all of the three reviewers

independently classified them as such.

RNA interference assay

To examine the biological functions of KIF20B, small

interfering RNAs (siRNAs, 100 µM; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) were

transfected into T-47D, HCC1937 and SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells

(0.5×106 cells/dish in 10-cm culture dishes) at 37°C for

5 h using Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Each gene was targeted using the following sequences:

si-KIF20B-#1, sense 5′-GAUGUAUCACUAGACAGUA-3′, antisense

5′-UACUGUCUAGUGAUACAUC-3′; si-KIF20B-#2, sense

5-CAACGAAUUUCAGAACCUA-3, antisense 5′-UAGGUUCUGAAAUUCGUUG-3′;

si-LUC control 1, sense 5′-CGUACGCGGAAUACUUCGA-3′, antisense

5′-UCGAAGUAUUCCGCGUACG-3′; and si-EGFP control 2, sense

5′-GAAGCAGCACGACUUCUUC-3′, antisense 5′-GAAGAAGUCGUGCUGCUUC-3′

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Western blot analysis was performed 72

h post-transfection, with antibodies against KIF20B to confirm

inhibition of KIF20B expression by siRNAs.

For the cell viability assay, breast cancer cells

transfected with siRNAs against KIF20B or si-controls were plated

in 6-well plates at a density of 0.5×105 cells/well. On

day 7 post-transfection, the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) solution

(Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) was used to measure cell viability.

The cells were incubated with CCK-8 reagent for 4 h and the

absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a multi-label plate reader

(ARVO X4 system; PerkinElmer, Inc.).

Colony formation assay

A total of 0.5×106 cells/dish were seeded

in 10-cm culture dishes and transfected with siRNAs against KIF20B

or si-LUC at 37°C for 5 h. After 7 days, the cells were washed with

PBS (−) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde phosphate-buffered

solution (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) at 4°C for 30

min. The cells were then stained with Giemsa at room temperature

for 1 h. A Canon PIXUS-MP990 multifunction device was used to

capture the images and colonies, defined as ≥50 cells, were

counted.

Annexin V fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC)-propidium iodide (PI) assay

Breast cancer cells that had been transfected with

siRNAs against KIF20B or si-LUC at 37°C for 5 h were plated in

10-cm dishes at a density of 0.5×106 cells/dish. After

48 h, the cells were trypsinized, washed twice with PBS and then

resuspended in 1X binding buffer at a concentration of

1×106 cells/ml. Apoptotic cells were stained using the

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen; BD

Biosciences) according to manufacturer's instructions. Control

assays were performed to set up compensation and quadrants. The

PI-A and Annexin V FITC-A plots were used for gating cells and

identifying changes in the scatter properties of the cells. The

data were analyzed and the plots were automatically generated using

the BD FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer (Ver1.2) and BD

FACSDiva™ software (Ver7.0), (BD Biosciences).

Caspase 3/7 expression assay

Caspase 3/7 activities were analyzed using the

CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent (cat. no. C10423;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to

manufacturer's instructions. Breast cancer cells transfected with

si-KIF20B or si-LUC (0.5×106 cells/dish) were seeded

into 6-well plates at a density of 0.5×105 cells/well in

an appropriate culture medium containing 10% FBS. The cells were

then incubated with CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent

at a final concentration of 4 µM for 30 min at 37°C, and then

monitored by live cell imaging at 15 min interval for 6 h using the

Evos M7000 Auto Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

Flow cytometric analysis

The BD FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer

(Ver1.2), BD FACSDiva™ software (Ver7.0) and the

CycleTEST PLUS DNA Reagent Kit (cat. no. 340242), (all BD

Biosciences) were used to carry out flow cytometric analysis of

cell cycle progression following the manufacturer's instructions.

The breast cancer cell lines were transfected with si-KIF20B-#2 or

si-LUC siRNA oligonucleotides at 37°C for 5 h. To assess DNA

ploidy, 1×106 cells/ml were harvested 72 h

post-transfection. Briefly, 250 µl solution A (trypsin buffer) was

added to the cells and incubated at room temperature for 10 min.

Subsequently, 200 µl solution B (trypsin inhibitor and RNase

buffer) was then added to the cells, gently mixed by tapping the

tube and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After

incubation, 200 µl cold solution C (PI staining solution) was added

to the cells and incubated in the dark at 4°C for 10 min. A 70-µm

nylon mesh was used to filter the samples and DNA content was

analyzed within 3 h in 20,000 ungated cells.

Live cell imaging

The Evos M7000 Auto Imaging System (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was used to monitor cytokinetics. Briefly, breast

cancer cells (0.5×106 cells/dish) transfected with

si-KIF20B or si-LUC were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of

0.5×105 cells/well in an appropriate culture medium

containing 10% FBS. Cell morphology and dynamics were monitored

using the Evos M7000 Auto Cell Imaging System. Images were captured

every 15 min over a period of 24 h up to 120 h.

Matrigel invasion assay

Cells transfected with siRNA against KIF20B or with

si-LUC were grown to 60% confluence in culture medium containing

10% FBS. After trypsinization, cells were washed with PBS (−) and

suspended in medium without serum or protease inhibitor. Matrigel

invasion assay was conducted according to the manufacturer's

recommendation using Matrigel matrix (BD Biosciences) as described

previously (30).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Stat

View 5.0 Statistical Program (SAS Institute, Inc.). The unpaired

Student's t-test was used to analyze the difference between two

groups in cell-based assays. Multiple comparisons were conducted

using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test to compare

means of each group with those of the other groups. The results are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and each experiment was

performed in triplicate. An analysis of the association between

KIF20B expression and clinical variables, including age,

histological type, ER, PR and HER2 status, pathological T (pT) and

N (pN) stages was conducted using Fisher's exact test. An overall

survival (OS) curve was calculated based on the date of surgery and

the date of breast cancer-related death or last follow-up. Breast

tumors were analyzed for KIF20B expression and Kaplan-Meier curves

were calculated for each relevant variable. Log-rank tests were

used to analyze differences in survival duration between patient

subgroups. To determine whether clinicopathological factors and

cancer-related mortality were associated, a Cox proportional hazard

regression model was used for univariate and multivariate analyses.

In the first step, individual associations between death and

possible prognostic factors were examined, including age, ER

status, PR status, HER2 status, pT classification and pN

classification. Using backward (stepwise) procedures, a

multivariate analysis was conducted incorporating KIF20B expression

into the model, along with all the variables statistically

significant (P<0.05) and independent of the other variables.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Database analysis

BioGPS (http://biogps.org/#goto=welcome), GTex Dataset

(https://gtexportal.org/home/) and UALCAN

(http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) databases

were used to examine the expression of KIF20B in tumor and normal

tissues and organs. cBioportal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org/) was used to investigate

the mutational status of the KIF20B gene. The PrognoScan

(http://www.prognoscan.org/) database was

used to assess the association between KIF20B expression and the OS

of patients with breast cancer.

Results

KIF20B expression in breast cancer

cell lines and tissues

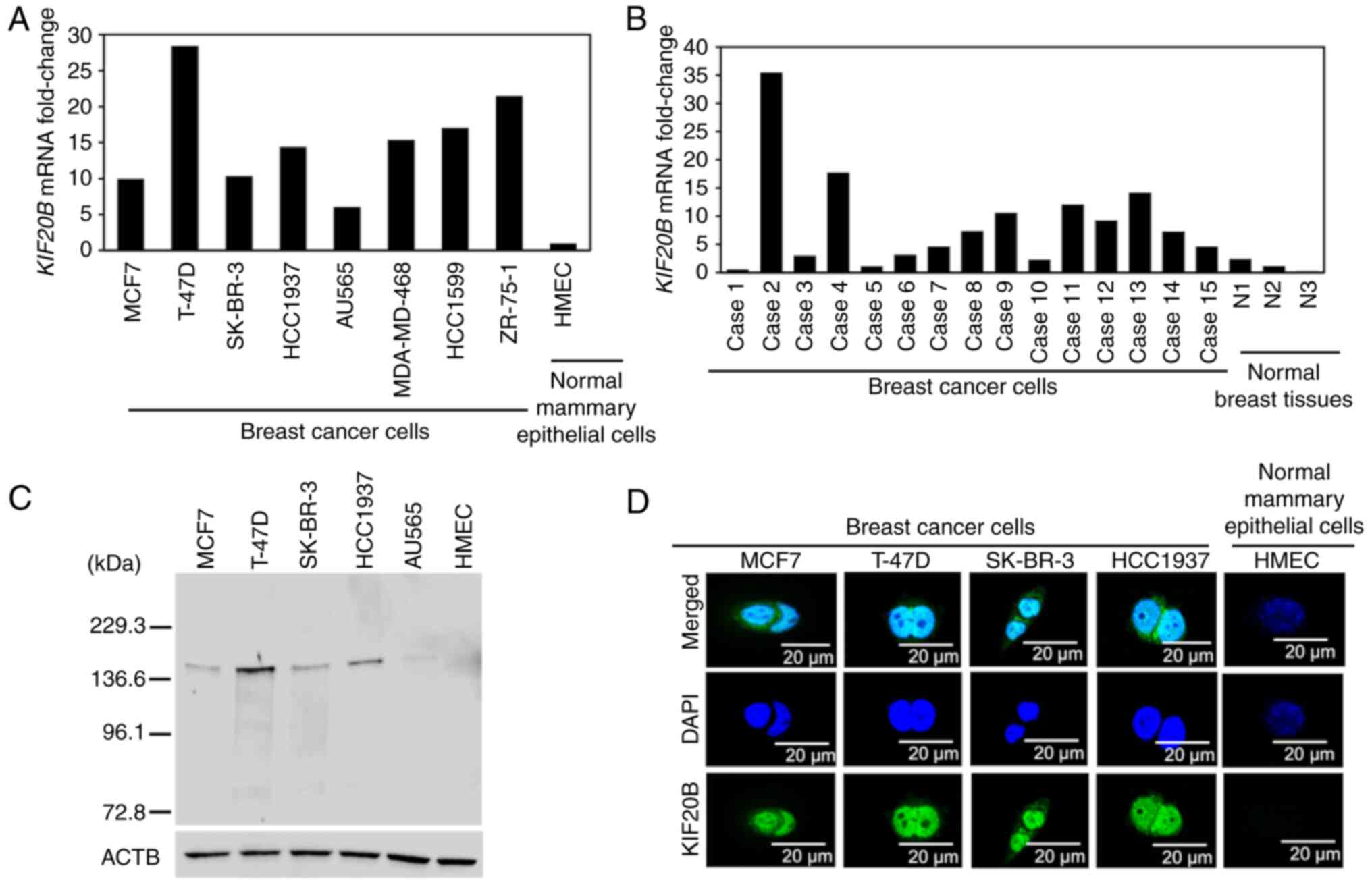

Using RT-qPCR, KIF20B mRNA expression was

detected in all of the breast cancer cell lines and tissues;

however, scarce expression was observed in normal breast epithelial

cells (HMECs) and tissues (Fig. 1A and

B). Cell lines representing each of the three breast cancer

subtypes were selected for western blotting and immunocytochemistry

experiments in the present study. KIF20B protein was found to be

highly expressed in breast cancer cells when compared with HMECs as

detected by western blotting (Fig.

1C). Furthermore, immunocytochemical analysis showed that

KIF20B protein was mainly localized in the cytoplasm and nuclei of

KIF20B-positive breast cancer cells (Fig. 1D).

Association of KIF20B expression with

poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer

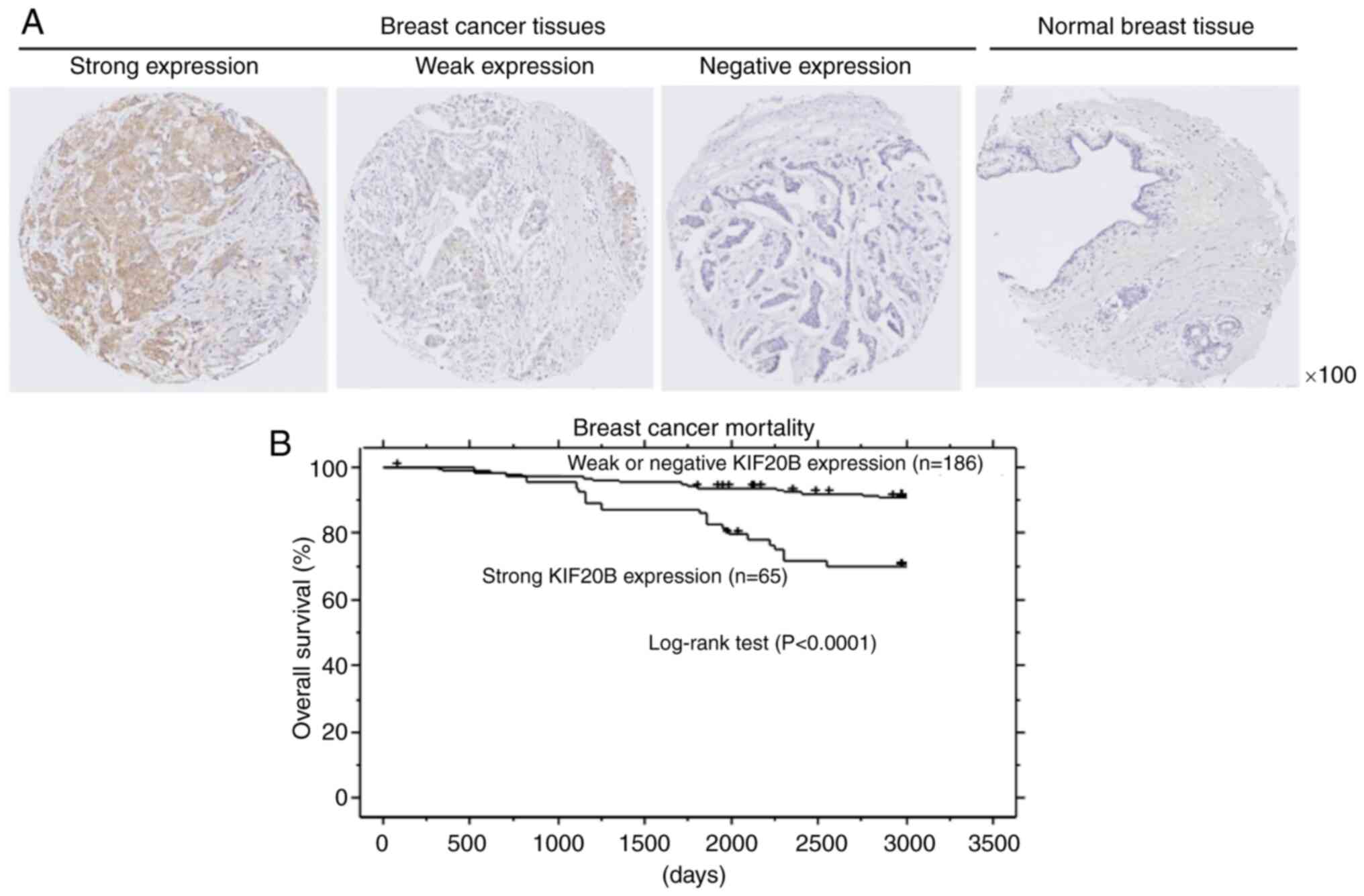

Immunohistochemical analysis detected KIF20B

expression in 145 (57.8%) out of the 251 breast cancer tissues

(Fig. 2A and Table II). In addition,

clinicopathological parameters related to KIF20B protein expression

were evaluated (Table II). Strong

KIF20B expression was significantly related to advanced pN stage.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that strong KIF20B protein expression

was associated with a poorer prognosis in patients with breast

cancer (Fig. 2B). Furthermore,

univariate analysis was conducted to determine the relationship

between patient prognosis and variables, such as KIF20B expression

status (strong positive vs. weak positive and negative), age (≥65

vs. <65 years), Luminal type (negative vs. positive), HER2

status (positive vs. negative), pT classification (T3-4 vs. T1-2)

and pN classification (N1-2 vs. N0). A strong positive KIF20B

expression, an advanced pT stage and an advanced pN stage were

significantly associated with a worse prognosis. Furthermore, in

multivariate analysis, both strong positive KIF20B expression and

advanced pN stage were independent prognostic factors (Table III).

| Table II.Association of KIF20B protein

expression in breast cancer tissues with patient characteristics

(n=251). |

Table II.

Association of KIF20B protein

expression in breast cancer tissues with patient characteristics

(n=251).

| Parameter | All patients | Strong positive

KIF20B expression | Weak positive

KIF20B expression | Negative KIF20B

expression |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Total | 251 | 65 | 80 | 106 |

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

| 0.2419 |

|

<65 | 188 | 45 | 59 | 84 |

|

|

≥65 | 63 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

|

| Luminal |

|

|

|

| 0.2687 |

|

Positive | 177 | 42 | 59 | 76 |

|

|

Negative | 74 | 23 | 21 | 30 |

|

| HER2 |

|

|

|

| 0.3145 |

|

Positive | 61 | 19 | 22 | 20 |

|

|

Negative | 190 | 46 | 58 | 86 |

|

| pT stage |

|

|

|

| 0.2331 |

|

T1-2 | 86 | 16 | 28 | 42 |

|

|

T3-4 | 165 | 49 | 52 | 64 |

|

| pN stage |

|

|

|

| 0.0134b |

| N0 | 142 | 28 | 45 | 69 |

|

|

N1-2 | 109 | 37 | 35 | 37 |

|

| Table III.Cox's proportional hazards model

analysis of prognostic factors in patients with breast cancer. |

Table III.

Cox's proportional hazards model

analysis of prognostic factors in patients with breast cancer.

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Univariate

analysis |

|

|

|

| KIF20B

expression (strong positive vs. weak positive and negative) | 3.509 | 1.823–6.755 | 0.0002a |

| Age

(≥65 vs. <65 years) | 1.382 | 0.68–2.808 | 0.3717 |

| Luminal

type (negative vs. positive) | 1.834 | 0.945–3.558 | 0.0729 |

| HER2

(positive vs. negative) | 2.157 | 0.725–2.997 | 0.2835 |

| pT

stage (T3-4 vs. T1-2) | 2.886 | 1.201–6.936 | 0.0178a |

| pN

stage (N1-2 vs. N0) | 5.998 | 2.627–13.695 |

<0.0001a |

| Multivariate

analysis |

|

|

|

| KIF20B

expression (strong positive vs. weak positive and negative) | 2.674 | 1.375–5.198 | 0.0002a |

| pT

stage (T3-4 vs. T1-2) | 1.76 | 0.714–4.339 | 0.2198 |

| pN

stage (N1-2 vs. N0) | 4.554 | 1.94–10.69 | 0.0005a |

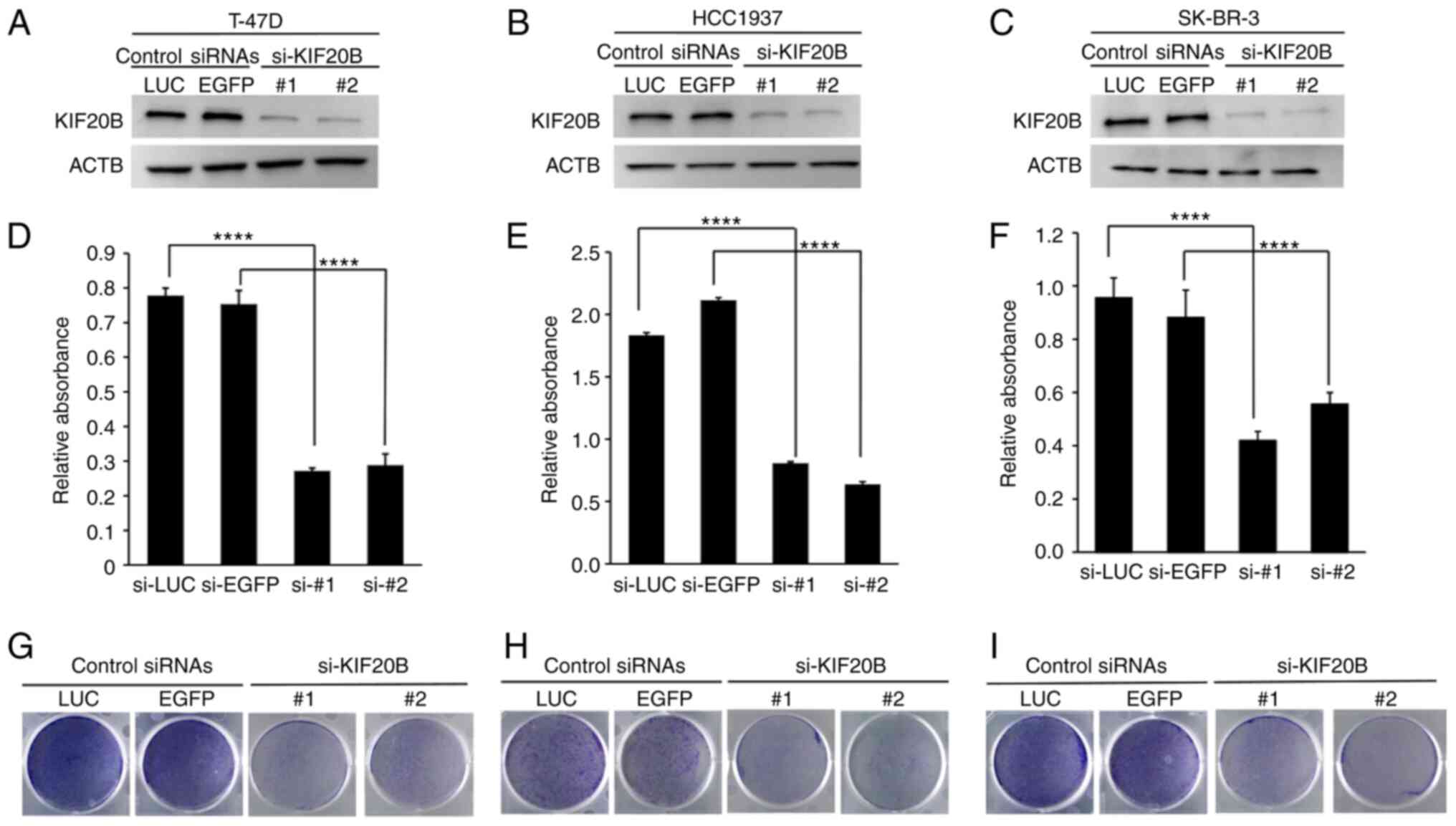

KIF20B knockdown inhibits breast

cancer cell proliferation

The expression of KIF20B was suppressed using

si-KIF20Bs in T-47D (luminal A), HCC1937 (TNBC) and SK-BR-3

(HER2/neu-positive) breast cancer cell lines. Compared with control

siRNAs, si-KIF20B decreased KIF20B protein expression levels in

breast cancer cells (Fig. 3A-C).

Additionally, MTT assay revealed that si-KIF20B significantly

inhibited breast cancer cell viability compared with control siRNAs

(Fig. 3D-F). Moreover, colony

formation assay showed a marked reduction in breast cancer cell

proliferation in response to KIF20B knockdown (Fig. 3G-I).

KIF20B knockdown induces dysregulation

of cell division, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer

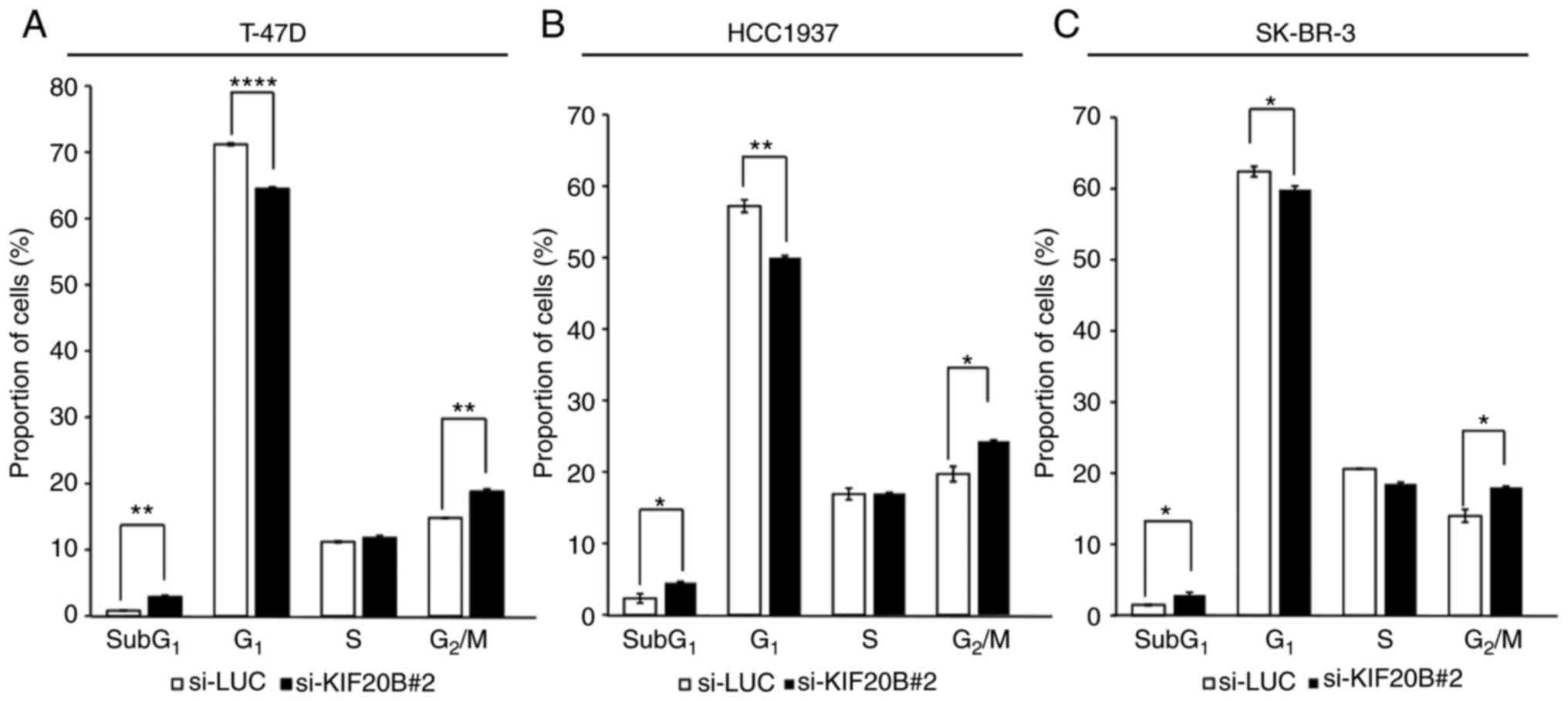

cells

To further examine the mechanism of breast cancer

cell proliferation controlled by KIF20B, flow cytometric analysis

of cell cycle progression was performed after siRNA transfection.

si-LUC was selected for further experiments due to its stability

and lower toxicity to breast cancer cells, whereas si-KIF20B-#2 was

selected for further experiments because it showed better knockdown

effect on KIF20B expression. Compared with si-LUC, at 72 h

post-transfection, si-KIF20B#2 significantly increased the

proportion of cells at the sub-G1 and G2/M

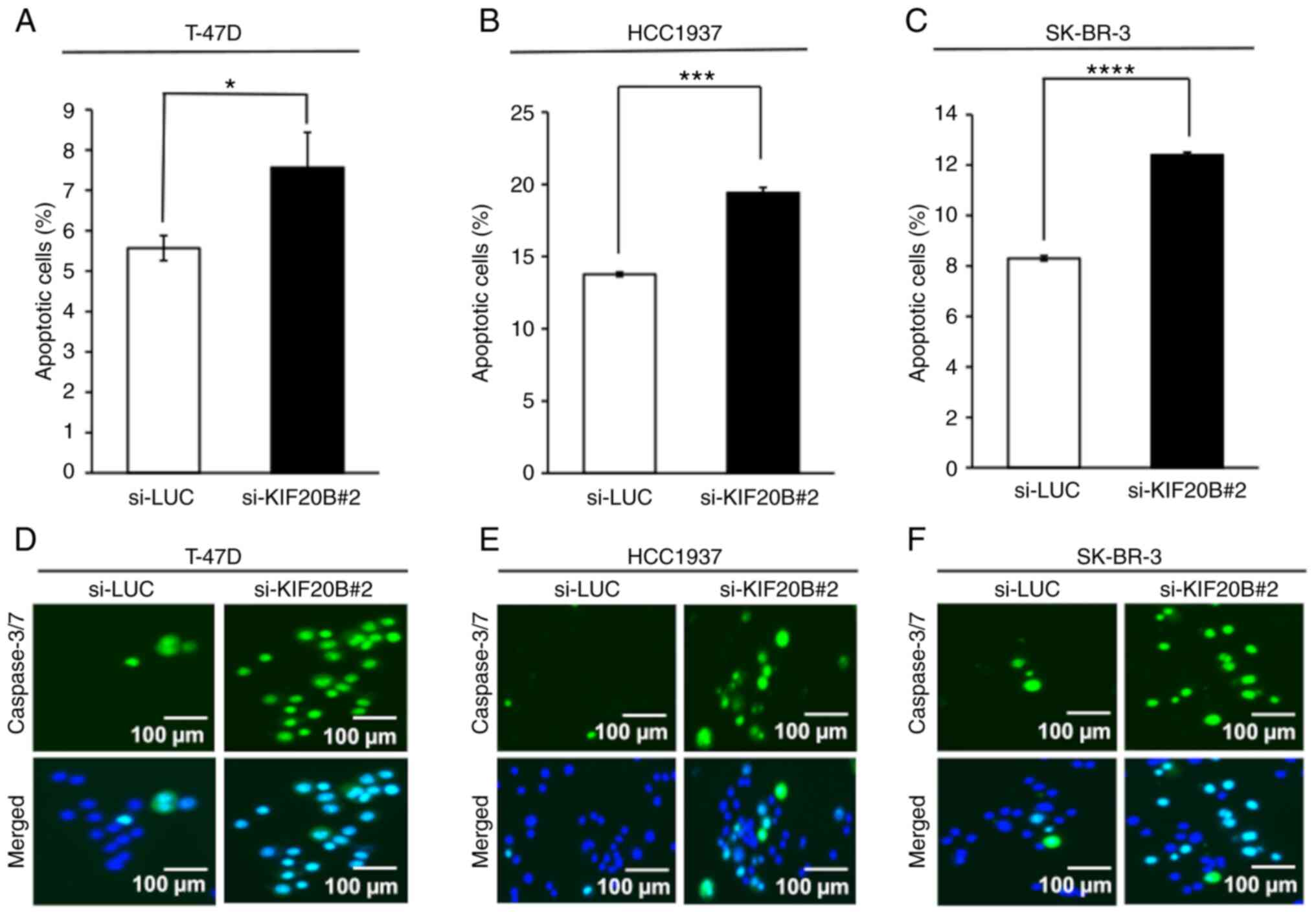

phases (Figs. 4A-C and S2). In addition, the number of apoptotic

cells was significantly increased after siRNA-mediated KIF20B

knockdown compared with that in the control group (Figs. 5A-C and S3). Additionally, the caspase 3/7 assay

demonstrated increased activation of caspase 3/7 in breast cancer

cells transfected with si-KIF20B#2 compared with the control siRNA

(Fig. 5D-F).

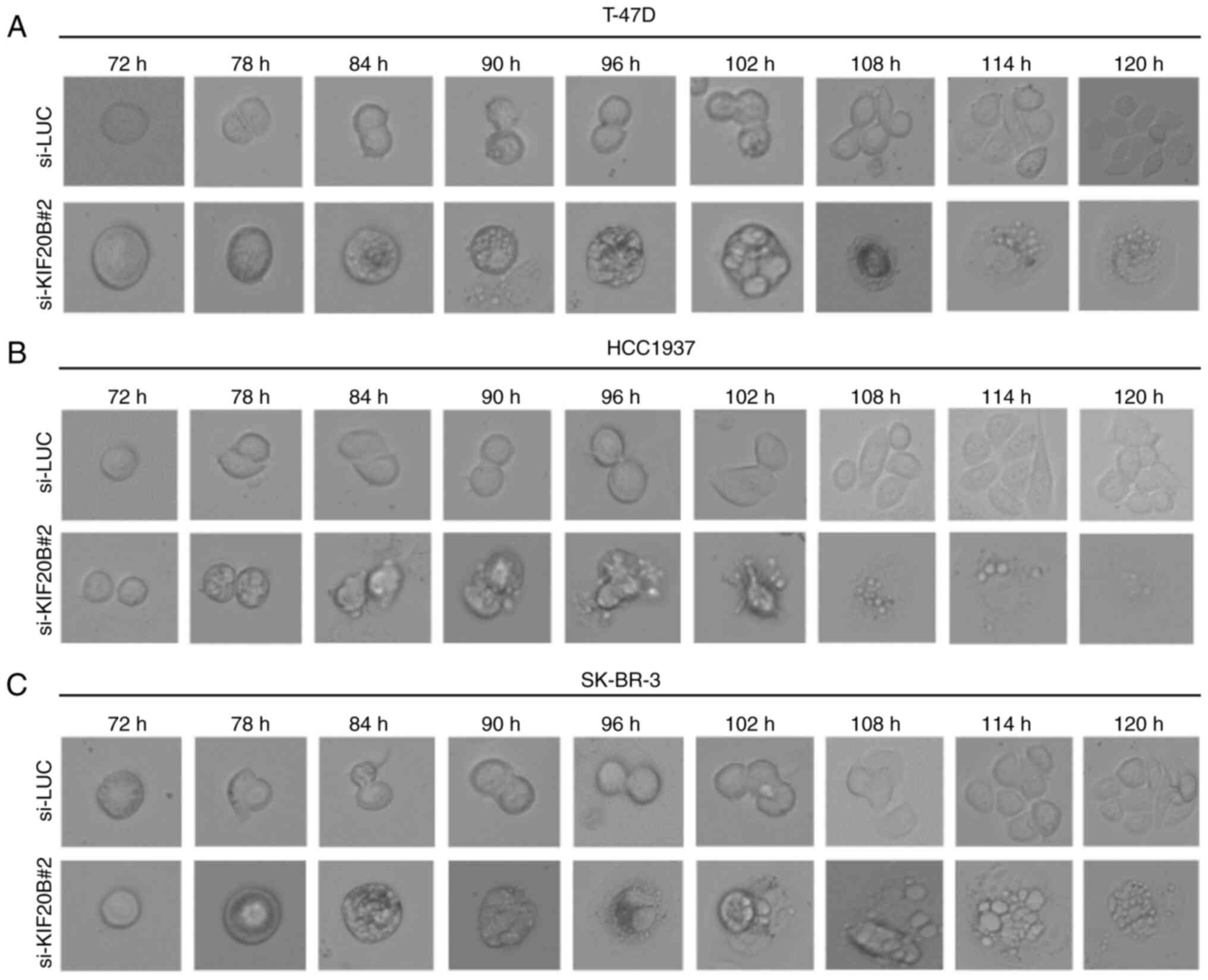

Morphological changes in T-47D, HCC1937 and SK-BR-3

cells transfected with si-KIF20B#2 were further monitored by live

cell imaging (Fig. 6A-C). Cells

transfected with control siRNAs divided regularly, whereas cells

transfected with si-KIF20B#2 did not properly divide and exhibited

increased cell death, suggesting that knockdown of KIF20B induces

G2/M arrest and subsequent cell death.

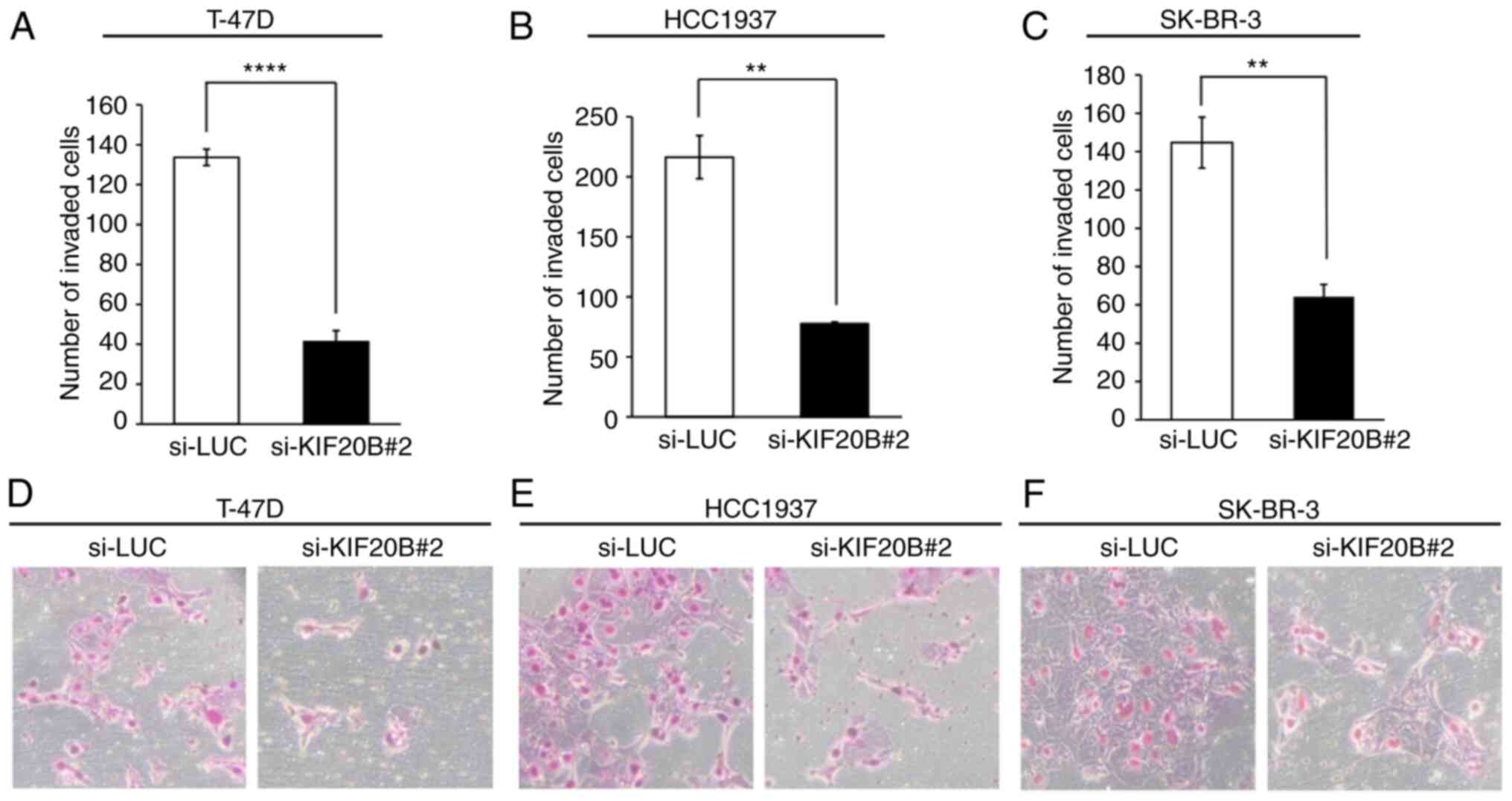

KIF20B knockdown inhibits the invasive

phenotype of breast cancer cells

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the

effects of strong KIF20B expression on advanced pN stage, as

detected by tissue microarray analysis, Matrigel assays were

performed to assess the potential role of KIF20B in the invasion of

breast cancer cells. The invasive activity of T-47D, HCC1937 and

SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells was significantly reduced after

knockdown of KIF20B with si-KIF20B#2 compared with that in the

control group (Fig. 7A-F).

Database analysis of KIF20B

expression, OS and mutations

In order to validate the expression of KIF20B

in breast cancer and normal tissues, we examined KIF20B data

using databases. The BioGPS, GTex Dataset and UALCAN databases

showed scarce expression of KIF20B gene in normal tissues

and organs, and indicated that KIF20B was significantly upregulated

in breast cancer tissues compared to normal tissues (data not

shown). Using PrognoScan, a significant association between high

KIF20B expression and reduced OS of patients with breast

cancer was identified (dataset no. GSE143; P=0.036199). In order to

examine the mechanisms underlying the effects of KIF20B

upregulation in breast cancer, KIF20B genetic alterations were

investigated using cBioportal for cancer genomics. The genetic

aberrations in KIF20B were detected in only 9 of 1,084 breast

invasive carcinoma cases (0.83%) (data not shown). Therefore, it

was hypothesized that the high expression of KIF20B may be due to

several epigenetic mechanisms.

Discussion

Breast cancer is a biologically heterogeneous

disease; therefore, the treatment responses and survival outcomes

of patients vary. Although significant advances in breast cancer

research have been made, it still has high incidence and mortality

rates. A wide range of treatments have been developed; however, the

OS rates remain low and some subtypes, such as TNBC, are difficult

to treat (41). Therefore, the

development of new molecular targeted drugs, as well as biomarkers

that are novel, precise and cost effective, is desired.

In the present study, KIF20B was found to be highly

expressed in breast cancer cells and tissues, but was barely

expressed in normal breast epithelial cells and tissues. In

addition, knockdown of KIF20B markedly inhibited the proliferation

of breast cancer cells and subsequently induced apoptosis. These

data suggested the potential of KIF20B as a diagnostic and

therapeutic target. Moreover, patients with breast cancer and

strong KIF20B expression had a significantly poorer prognosis than

those with weak or negative KIF20B expression. The findings from

the PrognoScan database independently support the current

experimental findings, indicating that KIF20B might be a prognostic

biomarker for breast cancer.

As determined by tissue microarray analysis, strong

KIF20B expression was significantly related to advanced pN stage

(nodal involvement). Furthermore, the results of a Matrigel cell

invasion assay showed that the invasiveness of breast cancer cells

was significantly decreased by KIF20B silencing. These data

potentially highlight the relevance of KIF20B activation in the

malignant potential of breast cancer cells, such as in cell

invasion, which is an important factor and the first step in cancer

metastasis, a hallmark of malignant tumors, which leads to the

dissemination of primary tumor cells to distant organs (42).

KIF20B, a member of the kinesin-6 family, is also

known as membrane palmitoylated protein 1 or MPHOSPH1. It is a

plus-end-directed kinesin-related protein that serves a crucial

role in cytokinesis. In addition, it has been reported to be

phosphorylated during the G2/M transition (43). KIF20B also influences

microtubule-binding and microtubule-bundling properties, and

microtubule-stimulated adenosine triphosphatase activity in

vitro (44). Knockdown of

KIF20B also potentially induced failed cytokinesis, due to the

observed dysregulation of cell division monitored by the live cell

imaging and subsequent apoptotic cell death. The present data

demonstrated that siRNA-mediated knockdown of KIF20B increased the

proportion of breast cancer cells in the sub-G1 and

G2/M phases. These data independently suggested that

KIF20B-mediated cytokinesis and G2/M transition are

important factors in breast cancer cell proliferation and/or

survival, and are potential therapeutic targets (Fig. S4). KIF20B is a mitotic target

regulated by Pin1, as evidenced by an in vitro interaction

of the tail domain of KIF20B with the WW domain of Pin1 (45). Pin1 serves an essential role in the

regulation of mitosis through its interaction with various mitotic

phosphorylated proteins at G2/M phase transition

(46). Furthermore, Pin1 protein

is involved in multiple cellular processes, including suppression

of apoptosis by directly regulating anti-apoptotic proteins

(47). Pin1 has also been reported

to be highly expressed in most types of cancer, including human

breast cancer (48). These reports

indicated the important role of KIF20B in the completion of

cytokinesis and that of Pin1 in the regulation of mitosis. In

addition, the present data demonstrated the increased proportion of

breast cancer cells in the sub-G1 and G2/M

phases, dysregulation of cell division and subsequent cell death

after knockdown of KIF20B. Based on these findings, it was

hypothesized that the dysregulation of cell division in

KIF20B-depleted breast cancer cells may be caused by mitotic

arrest, probably due to failure in cytokinesis, which may lead to

errors in chromosomal segregation and subsequent induction of

apoptotic cell death. Notably, direct elucidation of the role of

KIF20B in cytokinesis, and its relation to microtubules and

chromosomal segregation in breast cancer is required. Future

studies that examine the potential molecular function of the

KIF20B-Pin1 interaction, as well as the oncogenic functions of

KIF20B in breast cancer progression, are also warranted.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

suggested that KIF20B is an oncoprotein that serves an essential

role in breast cancer cell proliferation and survival, probably

through various unknown oncogenic pathways. Notably, KIF20B was

also shown to serve a pivotal role in breast cancer cell invasion.

Therefore, targeting KIF20B could be an effective approach in the

development of new molecular therapies and cancer biomarkers for

patients with breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific

Research (B), Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory),

and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from

the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI grant

nos. 15H04761, 19H03559, 21K19444, 16H06277, 22H04923 and

23H02815). YD is a member of Shiga Cancer Treatment Project

supported by Shiga Prefecture (Japan) and the International Joint

Research Project (grant no. FY2016-2024) of the Institute of

Medical Sciences (The University of Tokyo).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding authors.

Authors' contributions

RWM, AT and YD conceived the research concept and

designed the study. RWM, AT and YD developed the study methodology.

TYa, TYo, YM and YD acquired the data, managed the patients and

provided the facilities. RWM, AT, BT and YD analyzed and

interpreted the data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics and

computational analysis) and also confirm the accuracy of all the

raw data. RWM, AT and YD wrote, reviewed, and/or revised the

manuscript. RWM, AT and YD were involved in administrative,

technical, and/or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing

data, constructing databases). YD supervised the study. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The ethics committee at Kanagawa Cancer Center

(approval date: June 8, 2005; approval no. Rin-177) approved the

present research and the use of clinical materials. The project to

establish tumor tissue microarrays from archival formalin-fixed and

paraffin-embedded, surgically obtained tissues and to use the

tissue microarrays for later researches was approved by the

Kanagawa Cancer Center Ethics Committee (approval no. Rin-177;

Yokohama, Japan). Written informed consent was obtained from all

patients from Kanagawa Cancer Center for the use of the clinical

materials in this study. The ethics committee at Shiga University

of Medical Science (approval no. 21-163) approved the present study

including the use of all clinical materials.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

KIF20B

|

kinesin family member 20B

|

|

HMECs

|

human mammary epithelial cells

|

|

TNBC

|

triple-negative breast cancer

|

References

|

1

|

Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, Kramer

JL, Newman LA, Minihan A, Jemal A and Siegel RL: Breast cancer

statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:524–541. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A,

Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Gralow JR, Cardoso F, Siesling S

and Soerjomataram I: Current and future burden of breast cancer:

Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 66:15–23. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Voduc KD, Cheang MCU, Tyldesley S, Gelmon

K, Nielsen TO and Kennecke H: Breast cancer subtypes and the risk

of local and regional relapse. J Clin Oncol. 28:1684–1691. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tong CWS, Wu M, Cho WCS and To KKW: Recent

advances in the treatment of breast cancer. Front Oncol. 8:2272018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jamdade VS, Sethi N, Mundhe NA, Kumar P,

Lahkar M and Sinha N: Therapeutic targets of triple negative breast

cancer: A review. Br J Pharmacol. 172:4228–4237. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Raphael A, Salmon-Divon M, Epstein J,

Zahavi T, Sonnenblick A and Shachar SS: Alpelisib efficacy in

hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative PIK3CA-mutant advanced

breast cancer post-everolimus treatment. Genes (Basel).

29:17632022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Hudis CA and Gianni L: Triple-negative

breast cancer: An unmet medical need. Oncologist. 16 (Suppl

1):S1–S11. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu B, Domchek

SM, Masuda N, Delaloge S, Li W, Tung N, Armstrong A, et al:

Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline

BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 377:523–533. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hou Y, Peng Y and Li Z: Update on

prognostic and predictive biomarkers of breast cancer. Semin Diagn

Pathol. 39:322–332. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chung C, Yeung VTY and Wong KCW:

Prognostic and predictive biomarkers with therapeutic targets in

breast cancer: A 2022 update on current developments, evidence, and

recommendations. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 15:1343–1360. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ovcaricek T, Takac I and Matos E:

Multigene expression signatures in early hormone receptor positive

HER 2 negative breast cancer. Radiol Oncol. 53:285–292. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Daigo Y and Nakamura Y: From cancer

genomics to thoracic oncology: Discovery of new biomarkers and

therapeutic targets for lung and esophageal carcinoma. Gen Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg. 56:43–53. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Daigo Y, Takano A, Teramoto K, Chung S and

Nakamura Y: A systematic approach to the development of novel

therapeutics for lung cancer using genomic analyses. Clin Pharmacol

Ther. 94:218–223. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ishikawa N, Daigo Y, Takano A, Taniwaki M,

Kato T, Hayama S, Murakami H, Takeshima Y, Inai K, Nishimura H, et

al: Increases of amphiregulin and transforming growth factor-alpha

in serum as predictors of poor response to gefitinib among patients

with advanced non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Res.

65:9176–9184. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ishikawa N, Daigo Y, Yasui W, Inai K,

Nishimura H, Tsuchiya E, Kohno N and Nakamura Y: ADAM8 as a novel

serological and histochemical marker for lung cancer. Clin Cancer

Res. 10:8363–8370. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kakiuchi S, Daigo Y, Ishikawa N, Furukawa

C, Tsunoda T, Yano S, Nakagawa K, Tsuruo T, Kohno N, Fukuoka M, et

al: Prediction of sensitivity of advanced non-small cell lung

cancers to gefitinib (Iressa, ZD1839). Hum Mol Genet. 13:3029–3043.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kato T, Daigo Y, Hayama S, Ishikawa N,

Yamabuki T, Ito T, Miyamoto M, Kondo S and Nakamura Y: A novel

human tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase involved in pulmonary

carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 65:5638–5646. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kikuchi T, Daigo Y, Katagiri T, Tsunoda T,

Okada K, Kakiuchi S, Zembutsu H, Furukawa Y, Kawamura M, Kobayashi

K, et al: Expression profiles of non-small cell lung cancers on

cDNA microarrays: identification of genes for prediction of

lymph-node metastasis and sensitivity to anticancer drugs.

Oncogene. 22:2192–2205. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Suzuki C, Daigo Y, Ishikawa N, Kato T,

Hayama S, Ito T, Tsuchiya E and Nakamura Y: ANLN plays a critical

role in human lung carcinogenesis through the activation of RHOA

and by involvement in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway.

Cancer Res. 65:11314–11325. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kakiuchi S, Daigo Y, Tsunoda T, Yano S,

Sone S and Nakamura Y: Genome-wide analysis of organ-preferential

metastasis of human small cell lung cancer in mice. Mol Cancer Res.

1:485–499. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Taniwaki M, Daigo Y, Ishikawa N, Takano A,

Tsunoda T, Yasui W, Inai K, Kohno N and Nakamura Y: Gene expression

profiles of small-cell lung cancers: Molecular signatures of lung

cancer. Int J Oncol. 29:567–575. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Oshita H, Nishino R, Takano A, Fujitomo T,

Aragaki M, Kato T, Akiyama H, Tsuchiya E, Kohno N, Nakamura Y and

Daigo Y: RASEF is a novel diagnostic biomarker and a therapeutic

target for lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 11:937–951. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hayama S, Daigo Y, Yamabuki T, Hirata D,

Kato T, Miyamoto M, Ito T, Tsuchiya E, Kondo S and Nakamura Y:

Phosphorylation and activation of cell division cycle associated 8

by aurora kinase B plays a significant role in human lung

carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 67:4113–4122. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ishikawa N, Daigo Y, Takano A, Taniwaki M,

Kato T, Tanaka S, Yasui W, Takeshima Y, Inai K, Nishimura H, et al:

Characterization of SEZ6L2 cell-surface protein as a novel

prognostic marker for lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 97:737–745. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kato T, Sato N, Hayama S, Yamabuki T, Ito

T, Miyamoto M, Kondo S, Nakamura Y and Daigo Y: Activation of

Holliday junction recognizing protein involved in the chromosomal

stability and immortality of cancer cells. Cancer Res.

67:8544–8553. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Takano A, Ishikawa N, Nishino R, Masuda K,

Yasui W, Inai K, Nishimura H, Ito H, Nakayama H, Miyagi Y, et al:

Identification of nectin-4 oncoprotein as a diagnostic and

therapeutic target for lung cancer. Cancer Res. 69:6694–6703. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kobayashi Y, Takano A, Miyagi Y, Tsuchiya

E, Sonoda H, Shimizu T, Okabe H, Tani T, Fujiyama Y and Daigo Y:

Cell division cycle-associated protein 1 overexpression is

essential for the malignant potential of colorectal cancers. Int J

Oncol. 44:69–77. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Thang PM, Takano A, Yoshitake Y, Shinohara

M, Murakami Y and Daigo Y: Cell division cycle associated 1 as a

novel prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for oral cancer.

Int J Oncol. 49:1385–1393. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Daigo K, Takano A, Thang PM, Yoshitake Y,

Shinohara M, Tohnai I, Murakami Y, Maegawa J and Daigo Y:

Characterization of KIF11 as a novel prognostic biomarker and

therapeutic target for oral cancer. Int J Oncol. 52:155–165.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nakamura M, Takano A, Thang PM, Tsevegjav

B, Zhu M, Yokose T, Yamashita T, Miyagi Y and Daigo Y:

Characterization of KIF20A as a prognostic biomarker and

therapeutic target for different subtypes of breast cancer. Int J

Oncol. 57:277–288. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tsevegjav B, Takano A, Zhu M, Yoshitake Y,

Shinohara M and Daigo Y: Holliday junction recognition protein as a

prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for oral cancer. Int J

Oncol. 60:262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhu M, Takano A, Tsevegjav B, Yoshitake Y,

Shinohara M and Daigo Y: Characterization of Opa interacting

protein 5 as a new biomarker and therapeutic target for oral

cancer. Int J Oncol. 60:272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hirokawa N, Noda Y and Okada Y: Kinesin

and dynein superfamily proteins in organelle transport and cell

division. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 10:60–73. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kanehira M, Katagiri T, Shimo A, Takata R,

Shuin T, Miki T, Fujioka T and Nakamura Y: Oncogenic role of

MPHOSPH1, a cancer-testis antigen specific to human bladder cancer.

Cancer Res. 67:3276–3285. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lin WF, Lin XL, Fu SW, Yang L, Tang CT,

Gao YJ, Chen HY and Ge ZZ: Pseudopod-associated protein KIF20B

promotes Gli1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition modulated

by pseudopodial actin dynamic in human colorectal cancer. Mol

Carcinog. 57:911–925. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu X, Zhou Y, Liu X, Peng A, Gong H,

Huang L, Ji K, Petersen RB, Zheng L and Huang K: MPHOSPH1: A

potential therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer

Res. 74:6623–6634. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen J, Zhao CC, Chen FR, Feng GW, Luo F

and Jiang T: KIF20B promotes cell proliferation and may be a

potential therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. J Oncol.

2021:55724022021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li ZY, Wang ZX and Li CC: Kinesin family

member 20B regulates tongue cancer progression by promoting cell

proliferation. Mol Med Rep. 19:2202–2210. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK and Wittekind

C: TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th edition. John Wiley

& Sons; 2011

|

|

40

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cao L and Niu Y: Triple negative breast

cancer: Special histological types and emerging therapeutic

methods. Cancer Biol Med. 17:293–306. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Pearson GW: Control of invasion by

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition programs during metastasis. J

Clin Med. 8:6462019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Matsumoto-Taniura N, Pirollet F, Monroe R,

Gerace L and Westendorf JM: Identification of novel M phase

phosphoproteins by expression cloning. Mol Biol Cell. 7:1455–1469.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Abaza A, Soleilhac JM, Westendorf J, Piel

M, Crevel I, Roux A and Pirollet F: M phase phosphoprotein 1 is a

human plus-end-directed kinesin-related protein required for

cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 278:27844–27852. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kamimoto T, Zama T, Aoki R, Muro Y and

Hagiwara M: Identification of a novel kinesin-related protein,

KRMP1, as a target for mitotic peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1. J

Biol Chem. 276:37520–37528. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cheng CW and Tse E: PIN1 in cell cycle

control and cancer. Front Pharmacol. 9:13672018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liou YC, Zhou XZ and Lu KP: Prolyl

isomerase Pin1 as a molecular switch to determine the fate of

phosphoproteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 36:501–514. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wulf GM, Ryo A, Wulf GG, Lee SW, Niu T,

Petkova V and Lu KP: Pin1 is overexpressed in breast cancer and

cooperates with Ras signaling in increasing the transcriptional

activity of c-Jun towards cyclin D1. EMBO J. 20:3459–3472. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|