Introduction

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) play a pivotal role in

tumorigenesis and have been extensively investigated as a

prospective target for anticancer therapy (1,2).

An association exists between the presence of CSCs and tendencies

towards recurrence, treatment resistance and immunological

tolerance in bladder cancer (BC); nevertheless, the mechanisms by

which bladder CSCs (BCSCs) sustain their stemness are not fully

elucidated (3).

Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 (PYCR1) has been identified as

a carcinogenic factor of BC and has been shown to promote BC

proliferation, metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT) (4-6). PYCR1 can promote proliferation,

metastasis and EMT of BC, and its role is similar to that of tumor

stemness; therefore (7), it is

plausible to hypothesize the potential role of PYCR1 in the

regulation of BCSC stemness.

Histone methylation, a well-known epigenetic

modification mediated by histone demethylases, methyltransferases

and methylation reader proteins, is instrumental in cancer

pathogenesis (8). SET and MYND

domain-containing protein 2 (SMYD2) is a protein methyltransferase,

including a catalytic SET domain, known to facilitate

monomethylation of lysine residues on both histone and non-histone

proteins (8,9). Expression of SMYD2 is significantly

enhanced in breast cancer tissues, and patients with BC with

elevated SMYD2 expression show a poor prognosis (10). Elevated levels of SMYD2 may

promote the proliferation of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells

(11), as well as regulate gene

expression by modulating histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation

(H3K4me3) modification in the promoter region of its target gene,

thereby affecting gastric cancer cell glycolysis and proliferation

(12). It was proposed that SMYD2

may stimulate the transcriptional expression of PYCR1 by regulating

the levels of H3K4me3 in the promoter region of PYCR1 to regulate

BC stemness.

Mitophagy facilitates maintenance of stemness in

CSCs (13,14). Mitophagy enhances the plasticity

of CSCs via metabolic recombination, thereby improving their

adaptation to the tumor microenvironment (15). The putative kinase 1

(PINK1)/Parkin signaling pathway is one of the key mechanisms

regulating mitophagy (16,17).

When the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway is stimulated, SRY-box

transcription factor 2 (Sox2) promotes Nanog expression,

potentiates CSC self-renewal and preserves CSC stemness (18). PYCR1/2 serves as a crucial enzyme

in the proline biosynthetic pathway, and proline is capable of

inducing mitophagy via activation of AMPKα and the upregulation of

the Parkin expression (19). Our

previous study revealed that overexpression of PYCR1 has the

potential to boost the protein expression of PINK1 and Parkin,

leading to mitophagy in BC (4).

Also, PYCR1-augmented proline synthesis serves a crucial role in

sustaining the stemness of CSCs (20). Therefore, PYCR1 might regulate

BCSC stemness by controlling mitophagy via the PINK1/Parkin

pathway. It was hypothesized that SMYD2 may increase PYCR1

expression by upregulating the H3K4me3 levels in the PYCR1 promoter

region and promote BCSC stemness through PINK1/Parkin-regulated

mitophagy.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

SMYD2 expression in BC and normal bladder tissue and

the association between SMYD2 and PYCR1 in BC were analyzed using

the GEPIA database (gepia.cancer-pku.cn/).

Cell culture and grouping

Human BC cell lines T24 (SCSP-536) and EJ (YS1803C)

were procured from Institute of Chinese Academy of Sciences and

Yaji Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (both Shanghai, China), respectively.

T24 and EJ cells were cultured in DMEM/Ham's F-12 with 10% fetal

bovine serum (both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin solution (Shanghai Zeye Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells from the P3 generation

with 80% confluence were collected for subsequent experiments.

Human BC cell lines were grouped as follows: Blank

(untreated); small interfering (si)-PYCR1 (cells were transfected

with PYCR1 siRNA for 6 h and cultured for 18 h].); si-SMYD2 (BC

cells were transfected with SMYD2 siRNA for 24 h); si-negative

control (NC) (transfected with scramble siRNA for 24 h);

overexpression (oe)-PYCR1 (pcDNA3.1-PYCR1-transfected for 24 h);

oe-SMYD2 (transfected with pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 for 24 h); oe-NC

(transfected with pcDNA3.1-NC for 24 h); oe-SMYD2 + si-PYCR1

(transfection of pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 while being treated with PYCR1

siRNA for 24 h); oe-SMYD2 + si-NC (treated with scramble siRNA for

24 h while being transfected with pcDNA3.1-SMYD2); oe-PYCR1 +

si-PINK1 (24-h simultaneous treatment with pcDNA3.1-PYCR1 and PINK1

siRNA) and oe-PYCR1 + si-NC group (co-treatment with pcDNA3.1-PYCR1

and scramble siRNA for 24 h). si-PYCR1 forward 5′-UGC UAU CAA CGC

UGU GG-3′ and reverse 5′-CCA CAG CGU UGA UAG CA-3′; si-SMYD2:

forward: 5′-CAC CAG UUC UAC UCC AAG UTT-3′, reverse: 5′-ACU UGG AGU

AGA ACU GGU GTT-3′; si-NC: forward 5′-UUC UCC GAA CGU GUC ACG

UTT-3′ and reverse 5′-ACG UGA CAC GUU CGG AGA ATT-3′.

Cell transfection was performed using Lipofectamine

2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 24 h

with 10 nmol/l pcDNA3.1-PYCR1, pcDNA3.1-SMYD2, pcDNA3.1-NC, PYCR1

siRNA, SMYD2 siRNA, PINK1 siRNA, and scramble siRNA, with a final

concentration of 3.75 µl/ml, as previously described

(21).

Flow cytometry

Cells were prepared into a single-cell suspension

for the screening of BCSCs. After being washed twice with PBS,

cells were resuspended in PBS to adjust the cell concentration to

1×109/l. Cells were cultured in the presence of

antibodies labeled with CSC markers, such as CD44 (IM7) Rat mAb

(Alexa Fluor® 555 Conjugate; cat. no. #95235) and CD133

(A8N6N) Mouse mAb (Alexa Fluor® 647 Conjugate; cat. no.

#53276; both 1:50; both Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) on ice

without light for 30 min, followed by PBS rinsing three times.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting Aria III (BD Biosciences) was

employed to sort CD44+CD133+ cells.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

Total RNA extraction from cells was performed using

TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total RNA

underwent RT to complementary DNA using a PrimeScript RT reagent

kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was performed using TB

Green® Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

and primers (Table I) on the

ABI7900 fluorescence PCR instrument. Thermocycling conditions were

as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40

cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 60°C for 20

sec and extension at 72°C for 34 sec. β-actin was used as the

internal reference, and data analysis was conducted using the

2−ΔΔCq method (22).

| Table IPrimer sequences. |

Table I

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Forward, 5′→3′ | Reverse, 5′→3′ |

|---|

| PYCR1 |

GGCTGCCCACAAGATAATGGC |

GGCTGCCCACAAGATAATGGC |

| SMYD2 |

ATCTCCTGTACCCAACGGAAG |

CACCTTGGCCTTATCCTTGTCC |

| β-actin |

TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA |

TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA |

| Nanog |

CCCCAGCCTTTACTCTTCCT |

CCAGGTTGAATTGTTCCAGGTC |

| Sox2 |

ATCAGGAGTTGTCAAGGCAGAG |

AGAGGCAAACTGGAATCAGGA |

Colony formation assay

BC cells were seeded in 6 cm culture dishes at a

density of 1×103 cells/ml and cultured at 37°C for 14

days to colony formation. After the culture dish was washed with

distilled water, cells were immobilized at room temperature with 4%

paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 15 min and then

stained with crystal violet (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

for 30 min at room temperature. Images were captured and the

quantification of cell colonies was performed manually. The colony

was defined as a cell population large enough to be observed with

the naked eye.

CSC sphere-forming assay

Serum-free DMEM/F-12 (Gibco) was supplemented with

20 ng/ml each epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen) and basic

fibroblast growth factor (Gibco; all Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Then, 5 µg/ml insulin (Procell Life Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) and 100 µg/ml penicillin/streptomycin

were added to a low adhesion 6-well plate. Cells were re-suspended

with 1 ml medium added to the plate every 3 days. Afterward, cells

were seeded at 1,000 cells/well into DMEM/F-12 (serum-free).

Following 7 days of culture at 37°C, tumor spheres were collected

once the diameter reached 50-100 µm. Spheres were detached

and dispersed into single cells and re-seeded to form new tumor

spheres once again. After 14 days at 37°C, the culture was

terminated and the number of tumor sphere (diameter >50

µm) was calculated manually under the Leica DMi8 inverted

light microscope (200X magnification).

Cell mitophagy analysis

Cells were stained at 37°C with 400 nM Mito-Tracker

Green (cat. no. #C1046, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 40

min, and then blocked at 37°C for 1 h with 1% bovine serum albumin

(BSA, cat. no. #735094; Amresco, LLC) in PBS. Following 1 h

incubation at 37°C with the primary antibody light chain-3B (LC3B;

cat. no. ab192890, 1:100), the secondary antibody 6478-Conjugated

Goal Anti-Rabbit IgG (cat. no. ab150083, 1:200; both Abcam) was

added to cells for 30-min at 37°C and nuclei were stained with 5

µg/ml DAPI (cat. no. #C1002; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) at room temperature for 3 min. Finally, the

immunofluorescence was visualized using a laser confocal microscope

(200×).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

Analysis was conducted utilizing a

simpleChIP®Plus ultrasonic ChIP kit (cat. no. #56383,

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Cells at 80% confluence were

fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and

treated with glycine at room temperature for 15 sec at a final

concentration of 0.125 M (both Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

to halt the fixation process. Cells were lysed and centrifuged at

300 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Chromatin was resuspended in ChIP lysis

buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8, 1%

Triton X-100, 0.1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS), 1% protease inhibitor)

and sonicated on ice for 2 min (sonication: 3 sec on, 2 s off) to

shear DNA-protein fragments to approximately 500 bp. 20 µl

of cell lysate was incubated overnight at 4°C with 5 µg of

rabbit Anti-H3K4me3 antibody (#9751S, 1:50, Cell Signaling

Technology) or rabbit IgG (2729S, 1:100, Cell Signaling

Technology). Protein-A beads (20 µl) were then used to

capture the antibody complex. The beads were washed 7 times with

wash buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 500 mM LiCl; 1 mM EDTA; 1% NP-40

and 0.7% deoxycholate), followed by one wash with Tris-EDTA buffer

(10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). The precipitated DNA was purified

using a purification column and the expression of PYCR1 was

detected by RT-qPCR as aforementioned. Primers were as follows:

PYCR1-forward, 5′-CCT GTC ATC ATC TAA GAT AC-3′; PYCR1-reverse,

5′-CCC TGT CGG TGG CCA AGA TT-3′.

In vivo xenograft experiment

BALB/C nude mice (male, n=30; age, 5 weeks; weight

20-22 g) were purchased from Experimental Animal Resource Platform

of the Chinese Academy of Sciences [animal license no. SYXK

(Beijing) 2021-0063, Beijing, China]. Nude mice were housed in a

standard animal house (25±2°C, 50±10% relative humidity, 12/12-h

light-dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and

water).

The BC xenograft model was established by

subcutaneously injecting T24 cells (2×106 cells in 100

µl PBS) into nude mice. Mice were randomly divided (six

mice/group) into groups as follows: BC; BC + lentivirus

(Lv)-oe-SMYD2 (T24 cells delivered with pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 Lv were

subcutaneously injected); BC + Lv-oe-NC (injection of T24 cells

transfected with pcDNA3.1-NC Lv plasmid); BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 +

Lv-si-PYCR1 (T24 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 + si-PYCR1

Lv plasmids were hypodermically injected); BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 +

Lv-si-NC (T24 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 + si-NC Lv

plasmids were subcutaneously injected). After 4 weeks, mice were

euthanized via intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg sodium

pentobarbital and tumor tissue was obtained to measure the longest

longitudinal (a) and transverse diameter (b). The tumor volume was

calculated and weighed using the formula (a x b2)/2

(23), followed by protein

extraction, hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and

immunohistochemistry (IHC). The humane endpoints were body weight

of the mice decreased by 40% or the tumor diameter more than 3 cm).

No mice reached the humane endpoints.

Western blotting

The homogenates of cells or tumor tissues were lysed

using RIPA lysis solution (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

containing protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and

supernatants were obtained upon 20 min centrifugation at 12,000 × g

at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit. The

protein loading amount of each well was 10 µg. Following

separation via 10% SDS-PAGE, protein bands were moved to a PVDF

membrane and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies: Anti-PYCR1 (cat. no. ab226340, 1:2,000), anti-SMYD2

(cat. no. ab108217, 1:2,000), anti-Nanog (cat. no. ab21624, 1:200),

anti-Sox2 (cat. no. ab92494, 1:1,000), anti-H3K4me3 (cat. no.

ab272143, 1:500), anti-PINK1 (cat. no. ab216144, 1:1,000, all

Abcam), anti-Parkin (cat. no. PA5-13399, 1:2,000, Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), anti-LC3B (cat. no. ab192890,

1:2,000), anti-p62 (cat. no. ab109012, 1:10,000) and β-actin (cat.

no. ab8227, 1:1,000; all Abcam). Subsequently, the membrane was

washed with TBS-tween (0.1% Tween 20; cat. no. ST673; Beyotime) and

incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG

(cat. no. ab205718, 1:2,000, Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature.

Protein bands were visualized using the ultrasensitive enhanced

chemiluminescence kit (cat. no. P0018S, Beyotime) and the gray

values were quantified using Image J 1.8 software (National

Institutes of Health), with β-actin serving as the internal

reference. Cell experiments were repeated three times.

HE staining

Rat tumor tissues were subjected to paraffin

embedding after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 24 hand cut into 5-µm sections. The sections

were stained at room temperature for 20 min with HE Stain kit (cat.

no. G1120; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and

photographed under a light microscope (200×) (Olympus

Corporation).

IHC

The tumor tissue subjected to 24-h fixation with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature was embedded in paraffin,

serially sectioned (4 µm), dewaxed with xylene, and hydrated

with gradient alcohol. Sections were treated with 3%

H2O2 for 10 min to neutralize endogenous

peroxidase activity. The samples were subjected to antigen

retrieval in 0.01 mol/l sodium citrate buffer (pH=6.0, 15 min)

using microwave heating at 95°C. The sections were blocked at room

temperature for 20 min using 5% BSA (cat. no. A602440-0050, Sangon

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies against H3K4me3 (cat. no. ab8580, 1:100), SMYD2

(cat. no. ab234862, 1:200), CD44 (cat no. ab316123, 1:5,000) and

CD133 (cat. no. ab19898, 1:500; all Abcam). HRP labeled goat anti

rabbit IgG (cat. no. ab6721, 1:1,000; Abcam) was incubated at room

temperature for 20 min. After sections were rinsed with PBS, the

color was developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (cat. no.

B-IMWRS51, AmyJet Scientific, Inc.). The staining was observed

under a light microscope (200X magnification; Olympus Corporation).

The percentages of positive cells were counted and averaged using

Image J 1.8 (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

All data analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM

Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 9.5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics).

The data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent

experiments. Comparisons between two groups were performed using

unpaired t-test, while multi-group comparisons were analyzed using

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

PYCR1 promotes stemness maintenance of

BCSCs

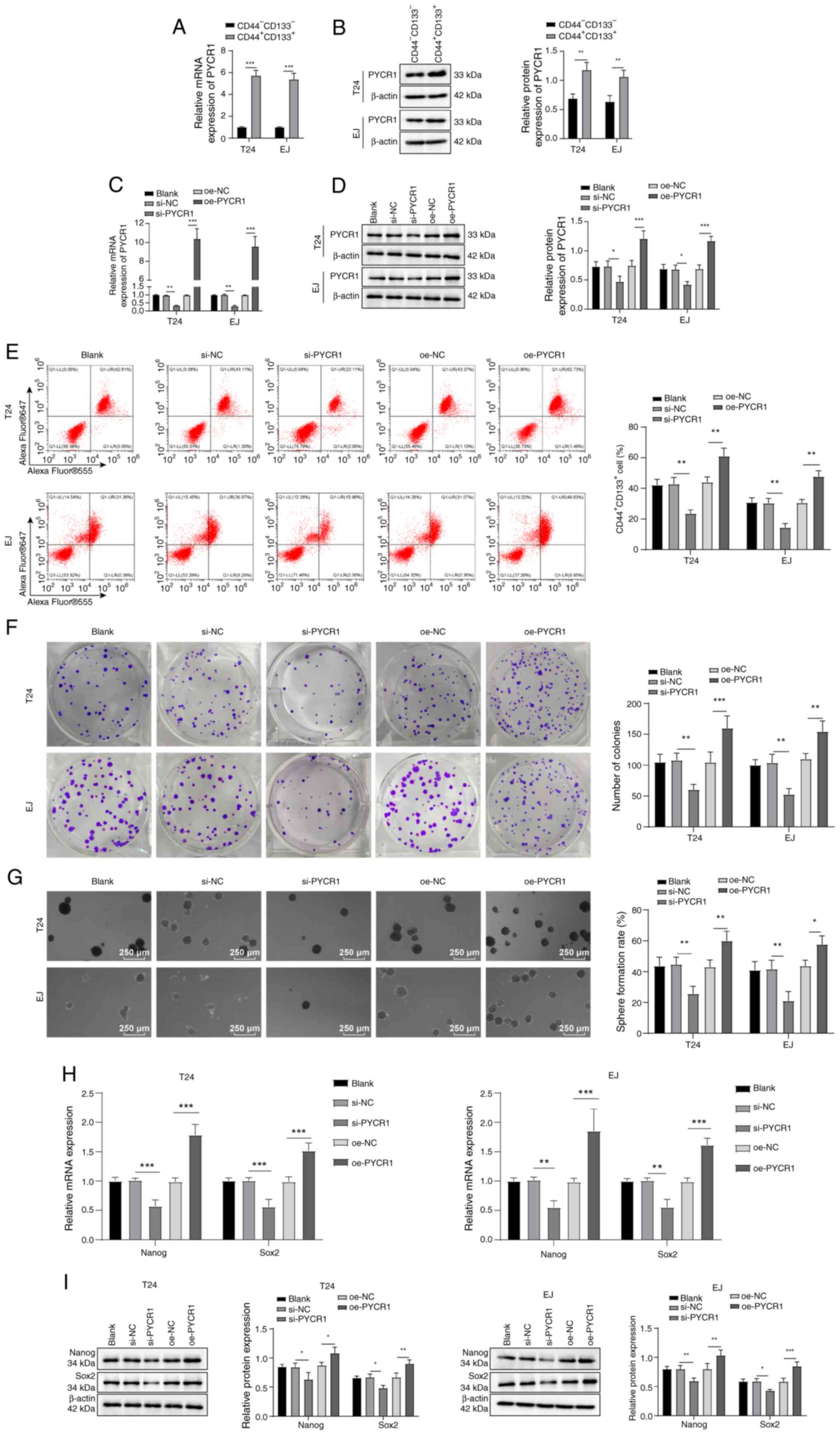

To investigate whether PYCR1 is involved in

regulating BCSC stemness, BC cell lines (EJ and T24) were cultured

in vitro. Subpopulations exhibiting SC characteristics

(CD44+CD133+) were sorted from BC cells by

flow cytometry and expression of PYCR1 mRNA and proteins in

CD44+CD133+ and

CD44−CD133− cells was assessed via RT-qPCR

and western blot. The results showed that PYCR1 mRNA and its

protein expression were higher in the

CD44+CD133+ BC cell subpopulation than in

CD44−CD133− cells (Fig. 1A and B). Following PYCR1 siRNA

treatment, PYCR1 mRNA and protein expression in BC cells (Fig. 1C and D),

CD44+CD133+ cell levels (Fig. 1E) and colony tumor sphere

formation (Fig. 1F and G) and

Nanog and Sox2 expression was reduced (Fig. 1H and I). Following transfection of

pcDNA3.1-PYCR1, BC cells had increased expression of PYCR1 mRNA and

protein (Fig. 1C and D) levels of

CD44+CD133+ cells (Fig. 1E), increased formation of cancer

cell colonies and tumor spheres (Fig.

1F and G) and elevated expression of Nanog and Sox2 (Fig. 1H and I). These results indicated

that PYCR1 enhanced BCSC stemness maintenance.

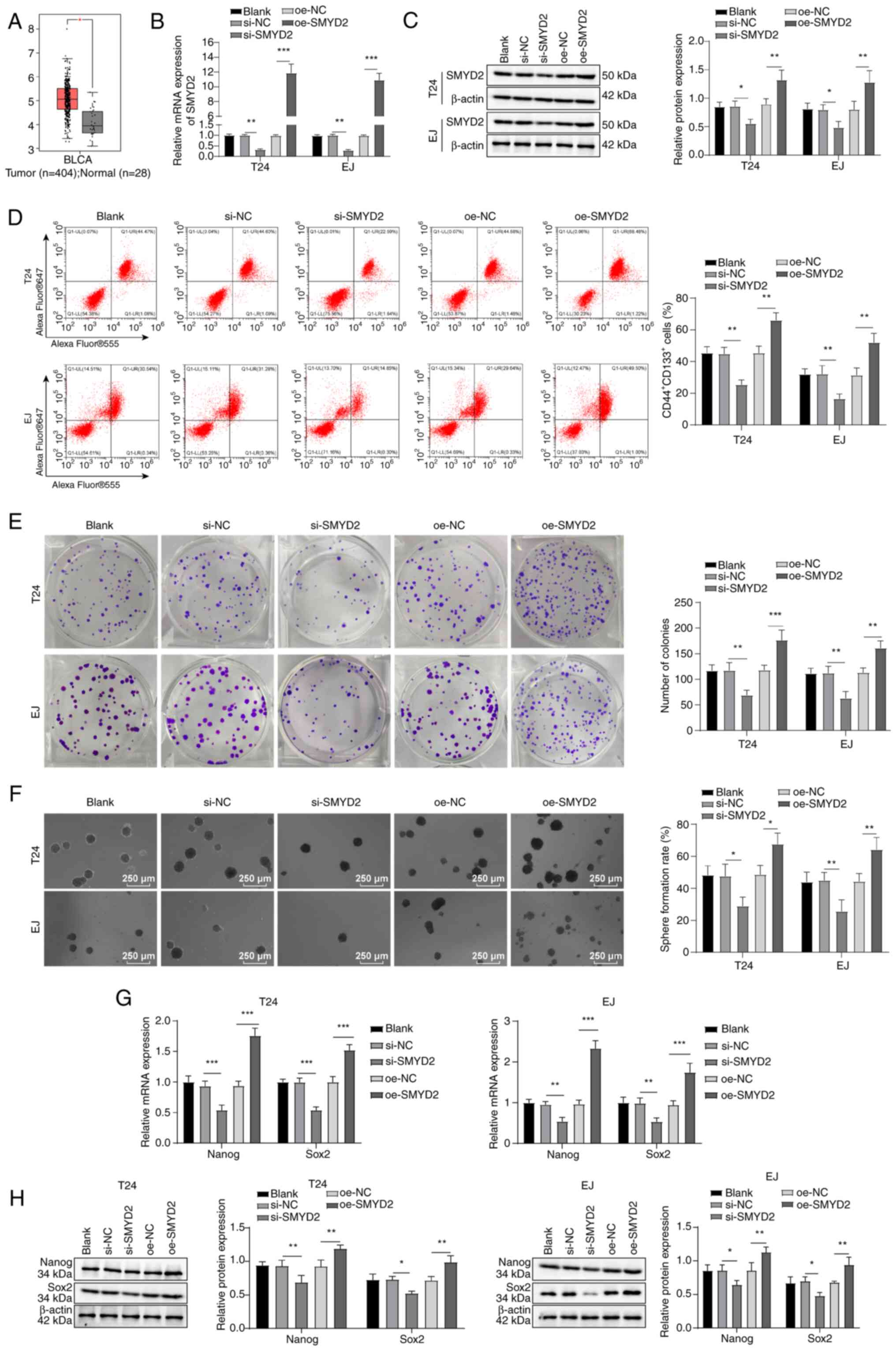

SMYD2 promotes stemness maintenance of

BCSCs

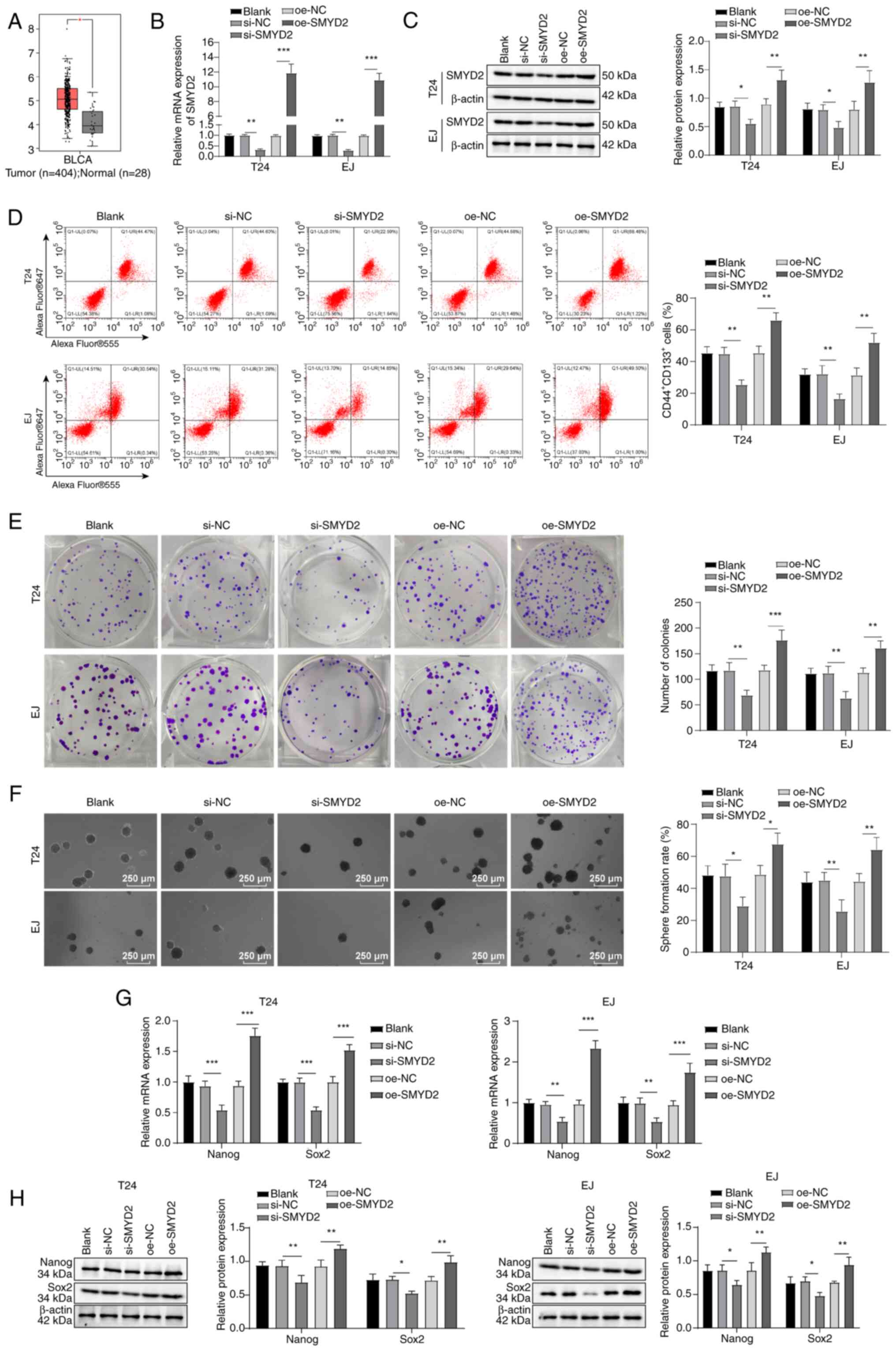

Multiple post-translational modifications of

proteins serve crucial roles in tumor progression, with methylation

modification being common (24).

SMYD2 is a protein lysine methyltransferase involved in the

advancement of BC (10). SMYD2

was found to be significantly highly expressed in BC through the

analysis of the GEPIA database (Fig.

2A). When BC cells were treated with SMYD2 siRNA, SMYD2 mRNA

and protein expression (Fig. 2B and

C), CD44+CD133+ cell levels (Fig. 2D), colony and tumor sphere

formation (Fig. 2E and F) and

Sox2 and Nanog expression decreased (Fig. 2G and H). However, following

transfection of pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 into BC cells, SMYD2 mRNA and

protein expression (Fig. 2B and

C), levels of CD44+CD133+ cells (Fig. 2D), colony and tumor sphere

formation (Fig. 2E and F) and the

protein expression of stemness markers Nanog and Sox2 was increased

(Fig. 2G and H). Altogether,

these findings illustrated that the stemness retention of BCSCs was

promoted by SMYD2.

| Figure 2SMYD2 promotes stemness retention in

bladder CSCs. (A) Analysis of SMYD2 expression in normal bladder

tissue and bladder cancer using Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis database. SMYD2 (B) mRNA and (C) protein

expression using RT-qPCR and western blotting. (D) Flow cytometry

to determine CD44+CD133+ cell levels. (E)

In vitro colony formation capability. (F) CSC sphere-forming

assay to examine tumor stemness. (G) RT-qPCR and (H) western

blotting were used to evaluate the expression of Nanog and Sox2.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. SMYD2, SET and MYND domain-containing

protein 2; CSC, cancer stem cell; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription

quantitative polymerase chain reaction; si, small-interfering; NC,

negative control; oe, overexpression; ns, not significant; BLCA,

bladder urothelial carcinoma. |

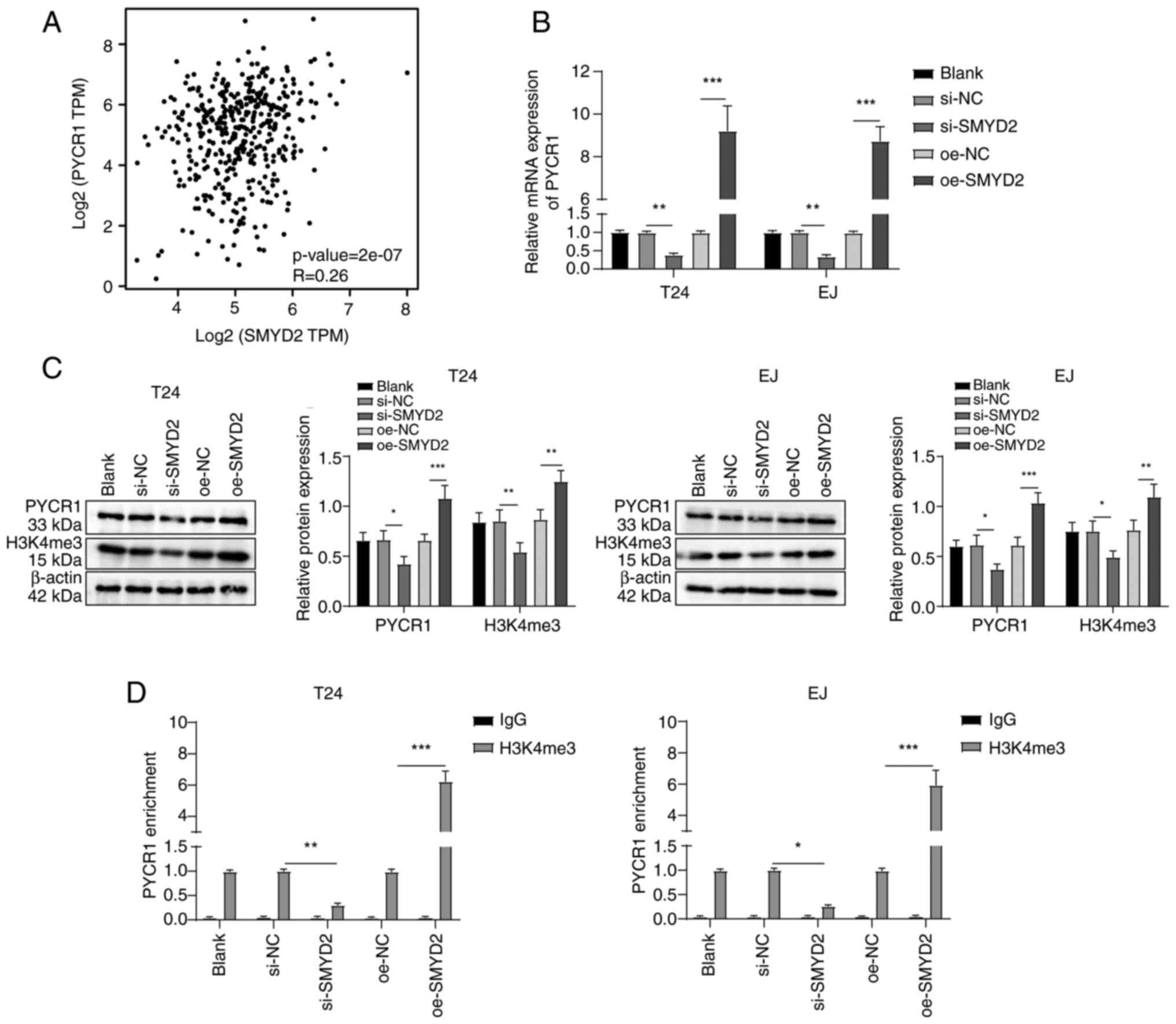

SMYD2 modulates H3K4me3 to upregulate

PYRC1 expression in BC cells

SMYD2 was positively associated with PYCR1

expression in BC according to the GEPIA database analysis (Fig. 3A). Following transfection of SMYD2

siRNA in BC cells, PYCR1 mRNA and its protein expression and

H3K4me3 levels decreased, while transfection of pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 into

BC cells increased PYCR1 mRNA and protein expression and H3K4me3

levels (Fig. 3B and C). ChIP

assay demonstrated enrichment of H3K4me3 in the PYCR1 promoter

region was decreased following SMYD2 siRNA but increased following

pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 transfection (Fig.

3D). Overall, SMYD2 modulated the expression of PYRC1 in BC

cells by controlling the H3K4me3 levels in the PYRC1 promoter

region.

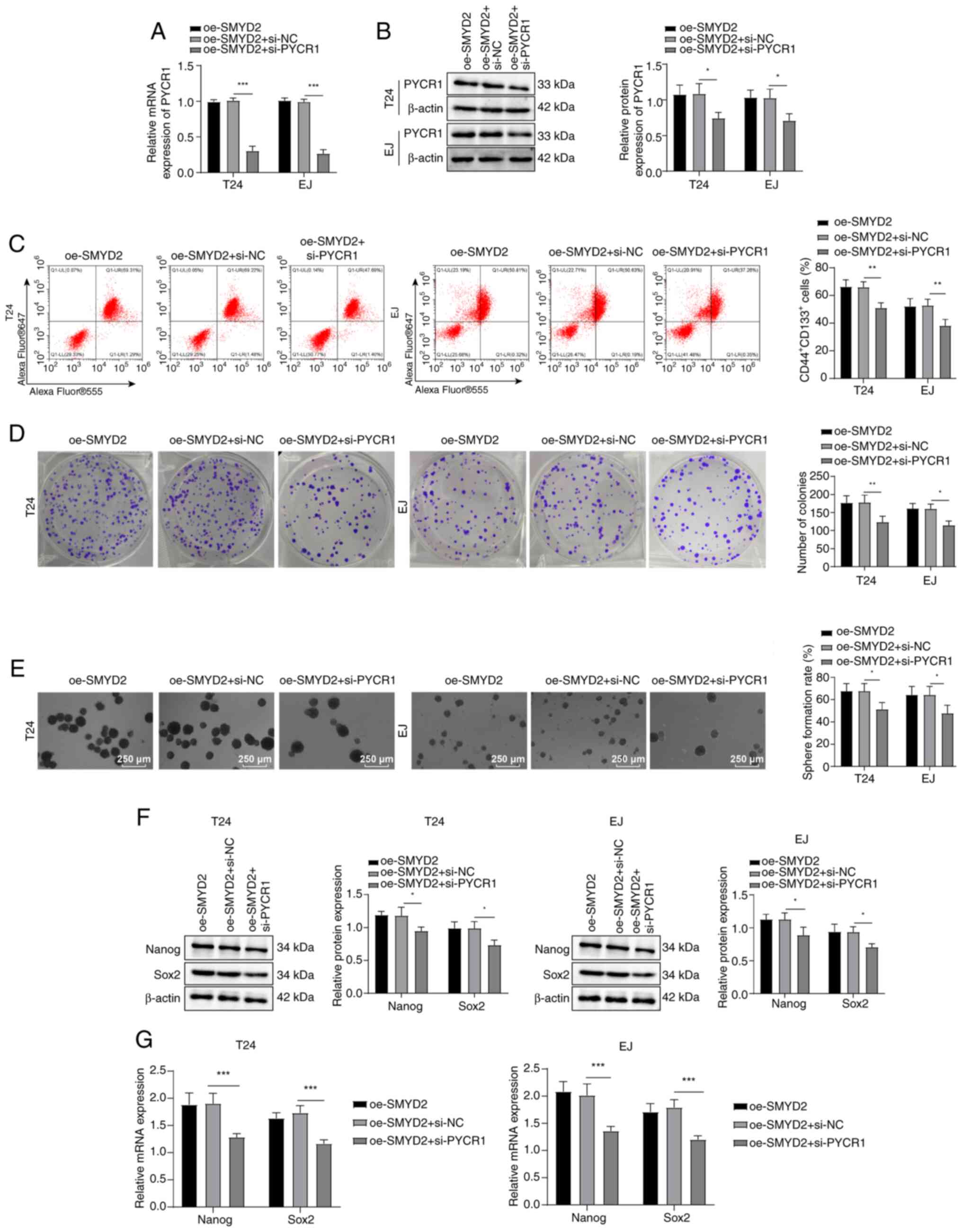

SMYD2 facilitates BCSC stemness

maintenance by regulating PYCR1

To explore whether SMYD2 can promote stemness

maintenance of BCSCs by modulating PYCR1, BC cells were transfected

with pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 and PYCR1 siRNA. Compared with oe-SMYD2 + si-NC

group, cells in the oe-SMYD2 + si-PYCR1 group exhibited decreased

expression of PYCR1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 4A and B),

CD44+CD133+ cell levels (Fig. 4C), colony and tumor sphere

formation (Fig. 4D and E) and

Nanog/Sox2 expression Fig. 4F and

G). These results suggested that SMYD2 contributed to BCSC

stemness maintenance by modulating expression of PYCR1.

PYCR1 potentiates BCSC stemness

maintenance via the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway

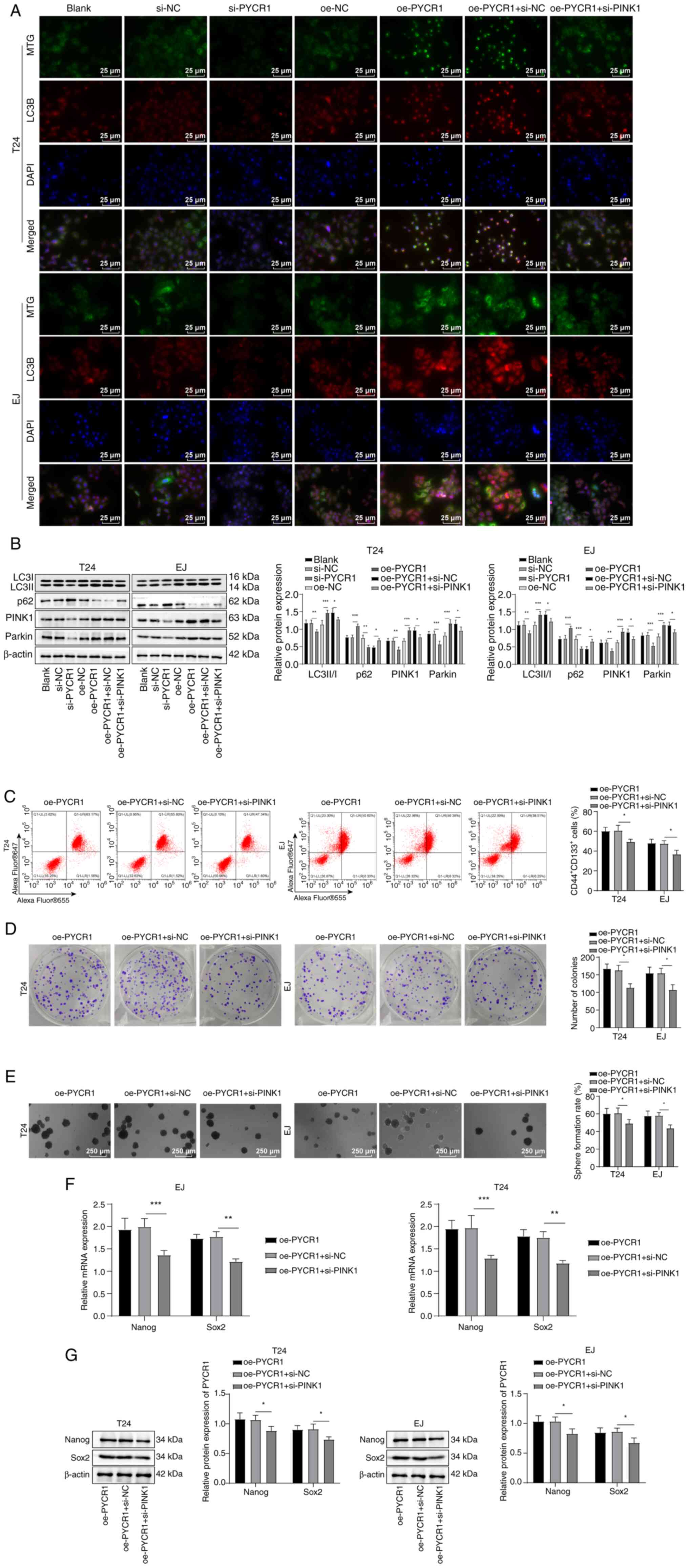

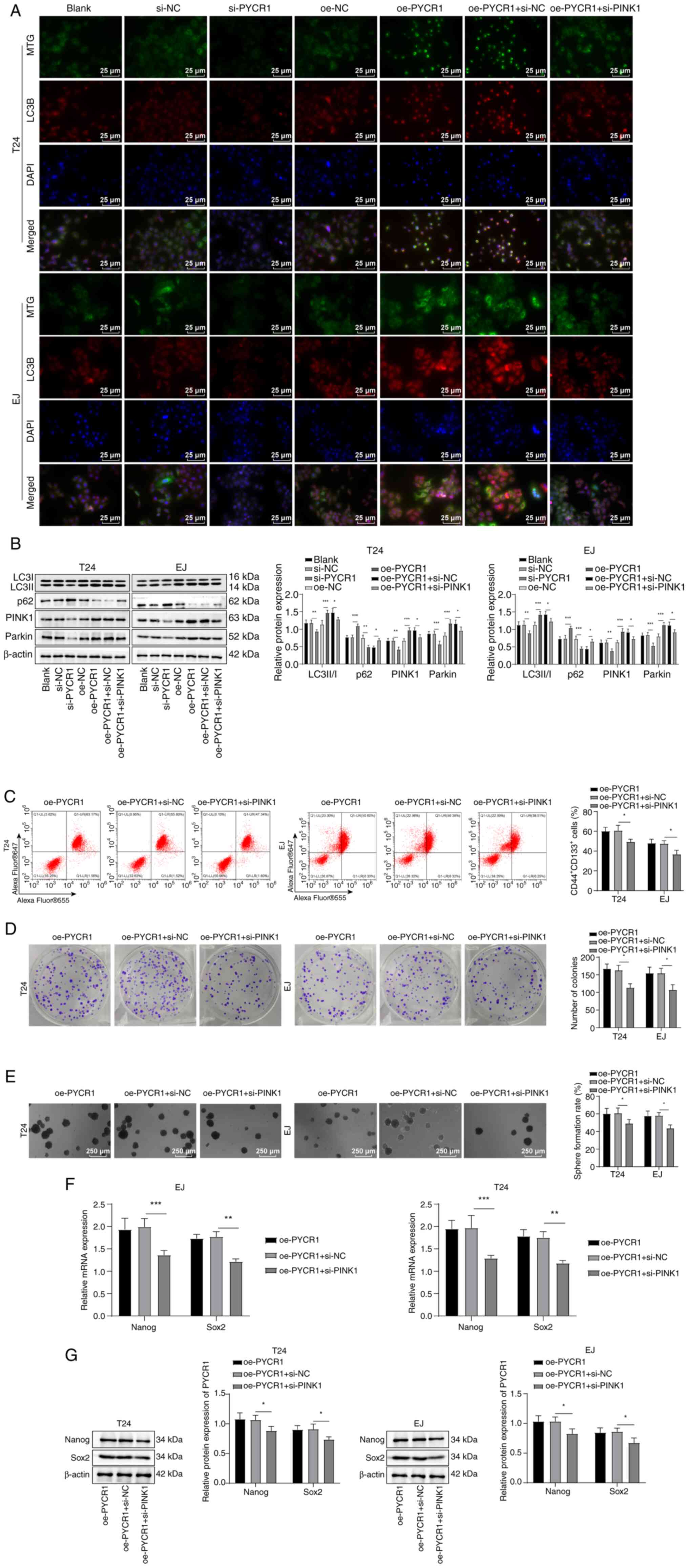

Following PYCR1 siRNA treatment, mitochondrial LC3B

expression (Fig. 5A) and LC3B

II/I ratio decreased and p62 protein expression was augmented

(Fig. 5B); these alterations were

reversed following pcDNA3.1-PYCR1 transfection. Additionally,

following treatment with PYCR1 siRNA, expression of PINK1 and

Parkin proteins was decreased; after transfection of

pcDNA3.1-PYCR1, expression of PINK1 and Parkin proteins increased

(Fig. 5B). BC cells were

transfected with PINK1 siRNA and pcDNA3.1-PYCR1. In comparison with

the oe-PYCR1 + si-NC group, oe-PYCR1 + si-PINK1 group exhibited

reduced PINK1/Parkin protein (Fig.

5B) and LC3B expression (Fig.

5A) and LC3B II/I ratio, raised p62 protein expression

(Fig. 5B) and inhibited

CD44+CD133+ cell levels (Fig. 5C), formation of tumor spheres and

colonies (Fig. 5D and E) and

expression of Sox2 and Nanog (Fig. 5F

and G). Collectively, these findings demonstrated that PYCR1

enhanced BCSC stemness maintenance via regulation of the

PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway.

| Figure 5PYCR1 promotes bladder CSC stemness

sustenance via the PINK1/Parkin pathway. (A) Immunofluorescence

detection of mitochondrial (MTG; green) and autophagy marker (LC3B;

red) expression. (B) Assessment of the protein levels of LC3B II/I,

p62, PINK1 and Parkin by western blot. (C) Measurement of

CD44+CD133+ cell level by flow cytometry. (D)

Colony formation assay. (E) CSC sphere-forming assay to estimate

tumor stemness. Expression of stemness marker proteins Nanog and

Sox2 (F) mRNA and (G) protein was assessed by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and western blot.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. SMYD2, SET and MYND domain-containing

protein 2; PYRC1, pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1; si,

small-interfering; NC, negative control; oe, overexpression; PINK1,

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; MTG, Mito-Tracker Green; CSC,

cancer stem cell. |

SMYD2 strengthens BCSC stemness

sustenance by activating the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway via

upregulation of PYCR1

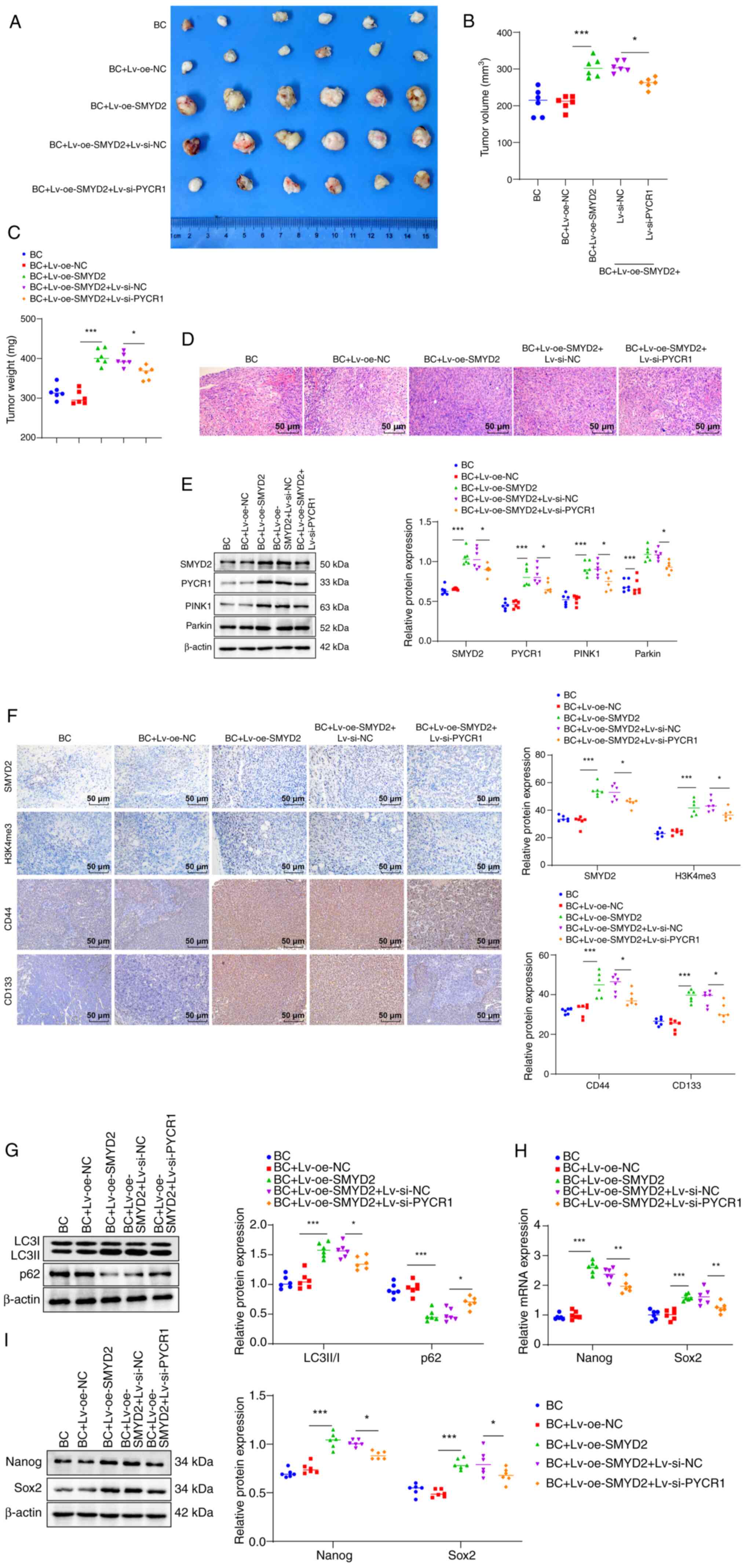

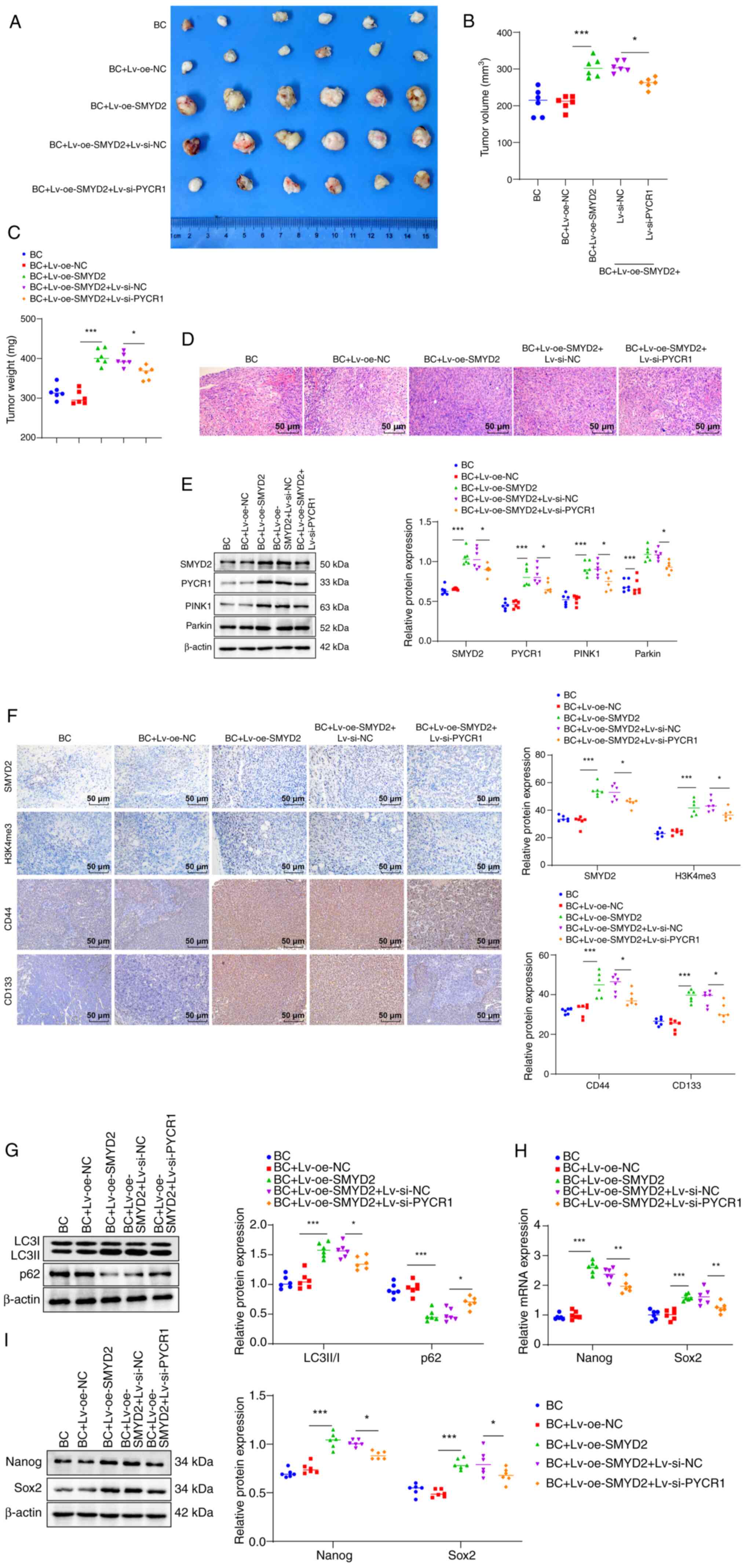

A BC xenograft model was established for in

vivo validation experiments by subcutaneously injecting T24

cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-SMYD2 or si-PYCR1 Lv plasmid into

nude mice. Tumor size and weight in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 group were

higher than those in the BC + Lv-oe-NC group; tumor weight and size

in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + Lv-si-PYCR1 group were lower than those

in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + si-NC group (Fig. 6A-C). HE staining showed that

compared with the BC + Lv-oe-NC group, the tumor cell density of

the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 group was elevated and the proportion of

necrotic cells (unstructured eosinophilic substances) were

decreased; compared with the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + si-NC group, the

tumor cell density of nude mice in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 +

Lv-si-PYCR1 group was decreased and the proportion of necrotic

cells increased (Fig. 6D). By

contrast with the BC + Lv-oe-NC group, protein levels of SMYD2,

PYCR1, PINK1 and Parkin in tissue homogenate of nude mice in the BC

+ Lv-oe-SMYD2 group were elevated (Fig. 6E). SMYD2, Parkin, PYCR1 and PINK1

expression in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + Lv-si-PYCR1 group was lower

than in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + si-NC group (Fig. 6E). As demonstrated by IHC results,

SMYD2-, H3K4me3-, CD44- and CD133-positive cell numbers in the BC +

Lv-oe-SMYD2 group were significantly augmented relative to the BC +

Lv-oe-NC group; nude mice in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + Lv-si-PYCR1

group displayed lower CD133- and CD44-positive cell numbers than

those in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + si-NC group (Fig. 6F). Western blot results revealed

that nude mice in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 group exhibited a higher

LC3B II/I ratio and lower p62 protein levels than the BC + Lv-oe-NC

group; BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + Lv-si-PYCR1 group exhibited a higher LC3B

II/I ratio and lower p62 protein expression compared with BC +

Lv-oe-SMYD2 + si-NC group (Fig.

6G). Moreover, Nanog and Sox2 protein levels were raised in the

BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 group vs. BC + Lv-oe-NC group but these protein

levels dropped in the BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + Lv-si-PYCR1 compared with

BC + Lv-oe-SMYD2 + si-NC group (Fig.

6H and I). In summary, these results indicated that SMYD2

sustained BCSC stemness by increasing PYCR1 expression to stimulate

the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway.

| Figure 6SMYD2 increases the maintenance of

bladder cancer stem cell stemness by upregulating PYCR1 to

stimulate the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Tumor (A) size, (B) volume and

(C) weight. (D) Hematoxylin-eosin staining to detect pathological

changes in tumor tissue. (E) Western blot to measure SMYD2, PYCR1,

PINK1 and Parkin levels in nude mouse tissue homogenate. (F)

Immunohistochemistry was performed to detect the number of SMYD2-,

H3K4me3-, CD44- and CD133-positive cells in tumor tissues. (G)

Protein expression of autophagy markers LC3B II/I and p62 was

determined by western blotting. (H) Expression of stemness marker

proteins Nanog and Sox2 mRNA was measured by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. (I) Western blot assay to detect

protein levels of Nanog and Sox2 in tissue homogenates of nude

mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. SMYD2, SET and MYND domain-containing

protein 2; PYCR1, pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1; PINK1,

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; H3K4me3, histone H3 lysine 4

trimethylation; BC, bladder cancer; Lv, lentiviral; oe,

overexpression; NC, negative control; si, small-interfering. |

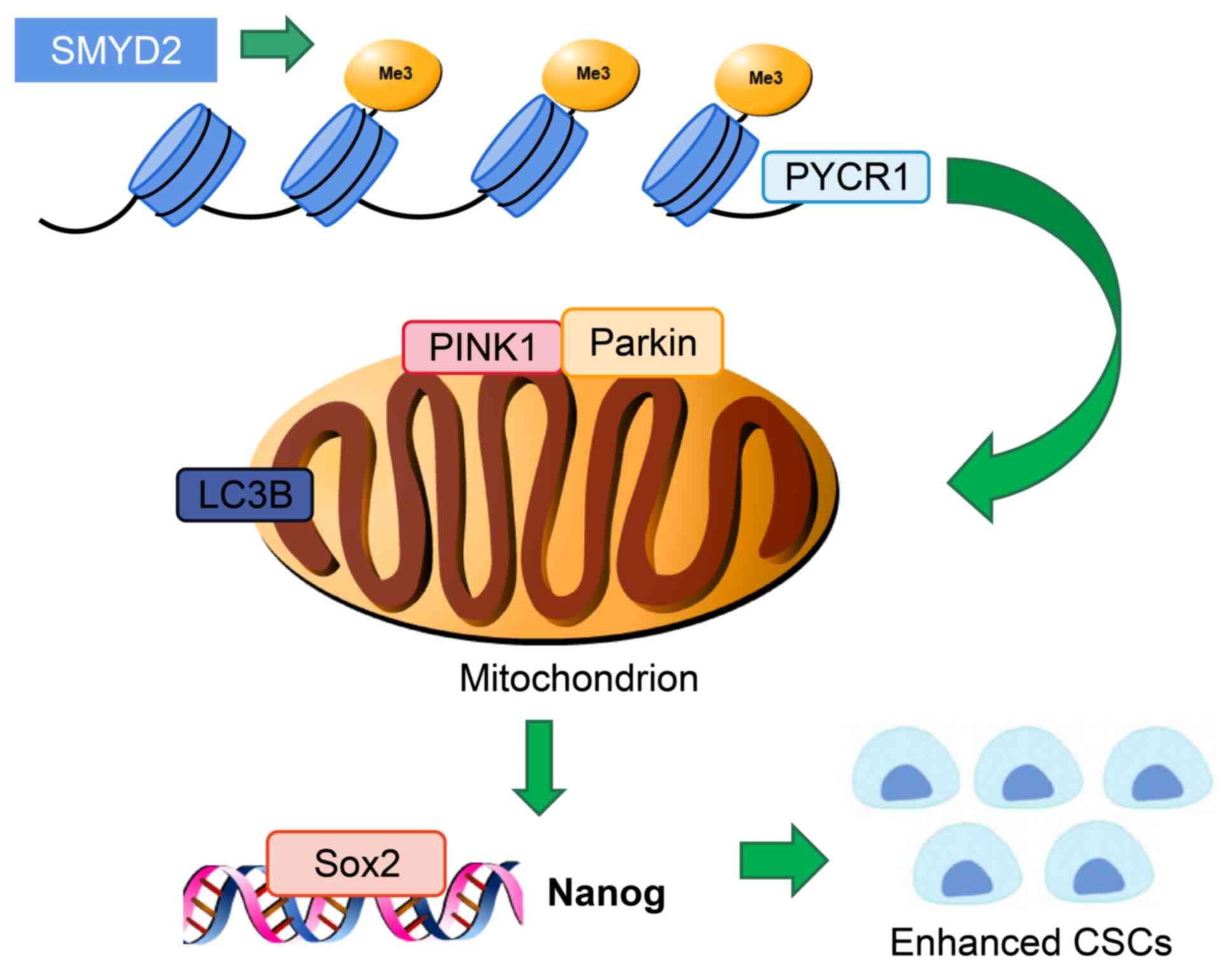

Discussion

Lysine methyltransferases, which affect numerous

oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins, play a key role in the

development of various types of malignancies, such as colorectal

cancer and lung cancer (25-27). SMYD2, an extensively studied

lysine methyltransferase, is associated with regulation of

transcription, epigenetics and tumorigenesis (28,29). However, the potential impact of

SMYD2 on the stemness maintenance of BCSCs remains unclear. The

present study demonstrated that histone methyltransferase SMYD2 is

involved in the stemness of BCSCs by upregulating PYCR1 expression

and activating the PINK1/Parkin pathway (Fig. 7).

PYCR1 strengthens BC proliferation and EMT, which is

associated with expression of stemness markers Nanog and Sox2

(4,30), suggesting that PYCR1 plays a role

in BCSC stemness. GEPIA database analysis demonstrated that SMYD2

was significantly highly expressed in BC. Correspondingly, SMYD2

expression is significantly increased in human BC compared with

normal bladder tissue, underscoring that inhibiting SMYD2 may have

therapeutic promise for BC (31).

The present study assessed the mechanism of SMYD2/PYCR1 in

maintaining BCSC stemness. CD44, a hallmark of BCSCs, indicates

stemness and activates many signaling pathways to maintain

self-renewal capacity (32,33). The potential role of CD44 and

CD133 as markers for BCSCs has been proposed (34). PYCR1 and SMYD2 knockdown in

CD44+CD133+ BCSC subpopulation with stem

cell-like characteristics decreased

CD44+CD133+ cell levels, Nanog and Sox2

expression and colony and sphere formation, whereas overexpressing

PYCR1 or SMYD2 resulted the opposite effects. Similarly,

suppression of PYCR1 in vitro decreases colony formation and

proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest (35). Cui et al (20) confirmed that ablation of PYCR1 can

lead to reduced expression of Sox2 and Nanog, CSC-associated

aldehyde dehydrogenase+ population and ability of breast

CSCs to form spheres, suggesting that PYCR1 is involved in

preserving the stemness of breast cancer cells. In addition, Shang

and Wei (36) demonstrated that

inhibition of SMYD2 impedes tumor sphere formation and cell

migration in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. To the best of our

knowledge, the impact of SMYD2 on the stemness of BCSCs has not

been reported. It was hypothesized that both SMYD2 and PYCR1

amplified maintenance of stemness in BCSCs.

H3K4me3 is abnormally expressed in lung, liver and

colon cancer (37-39). SMYD2 serves as a histone

methyltransferase of H3K4me3, facilitating transcriptional

activation of its downstream target genes by catalyzing

trimethylation of histone H3K4, which is associated with modulation

of target gene transcription (12,40). A notable positive association

between SMYD2 and PYRC1 was observed in the present study. To the

best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to

demonstrate that SMYD2 may promote PYCR1 expression via H3K4me3;

in vitro demonstrated increased PYCR1 and H3K4me3 levels,

along with heightened enrichment levels of H3K4me3 in the PYCR1

promoter region in SMYD2-overexpressing BC cells. Furthermore,

previous research has confirmed that proline produced by PYCR1 can

activate the cGMP/cGMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway,

thereby enhancing breast cancer stemness (20). Here, SMYD2 heightened stemness in

BCSCs by regulating PYCR1.

The PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway is one of the

primary regulatory mechanisms of mitophagy (17). The accumulation of PINK1 augments

PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, which efficiently removes impaired

mitochondria (41). The

feedforward signaling pathway, including PINK1 and Parkin, is

responsible for facilitating mitophagy (42). Here, PYCR1 silencing resulted in

elevated p62 and Parkin/PINK1 expression, as well as lessened LC3B

expression and LC3B II/I ratios, which were negated by PYCR1

overexpression. This indicated that PYCR1 could mediate the

Parkin/PINK1 mitophagy axis. Moreover, it is well-established that

mitophagy encourages the obtainment of tumor cell stemness

(14,43). The present experiments verified

the promoting effect of the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway in BCSC

stemness. Other investigations have established a connection

between mitophagy and SC stemness (44,45). Augmentation of mitophagy can

contribute to the stemness of mesenchymal SCs (46). Conversely, the reduction of

mitophagy-related PINK1/Parkin leads to diminished stemness of bone

marrow-derived mesenchymal SCs, as indicated by decreased

expression of stemness markers Sox2 and Octamer-binding

transcription factor 4 (44).

Here, PYCR1 stimulated stemness maintenance in BCSCs via the

PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway. Furthermore, in vivo

verification demonstrated that SMYD2 preserved BCSC stemness by

activating the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway via enhancement of

PYCR1 expression.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the

regulatory effect and mechanism by which SMYD2 affects PYCR1.

Additionally, in vitro and in vivo experiments

demonstrated the role of PYCR1 in modulating the PINK1/Parkin

signaling pathway, which affects mitophagy and regulates stemness

of BCSCs. However, the present study only verified that PYCR1

regulates mitophagy via regulation of PINK1/Parkin to regulate BCSC

stemness; other target genes and signaling pathways regulated by

PYCR1 require further investigation. Upstream influencing factors

of PYCR1 also need to be further explored. Future investigations

investigate the role of mitophagy in preserving the stemness of

CSCs, as well as the mechanisms by which PYCR1 modulates other

target genes and signaling pathways.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. JC contributed to the study concepts, study design; SX

and XY performed the literature review. JC and YW performed

experiments. JC and WS contributed to the data analysis. JC and SX

wrote and revised the manuscript. JC and SX confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the

Animal Ethics Committee of Hunan Provincial People's Hospital, The

First Affiliated Hospital of Hunan Normal University (approval no.

2024-84).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of

Hunan Province (grant no. 2025JJ50640), Hunan Provincial Health

High-Level Talent Scientific Research Project (grant no. R2023154)

and Hunan Provincial People's Hospital Doctoral Fund Project (grant

no. BSJJ202106).

References

|

1

|

Chen S, Zhu J, Wang F, Guan Z, Ge Y, Yang

X and Cai J: LncRNAs and their role in cancer stem cells.

Oncotarget. 8:110685–110692. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Eid RA, Alaa Edeen M, Shedid EM, Kamal AS,

Warda MM, Mamdouh F, Khedr SA, Soltan MA, Jeon HW, Zaki MS and Kim

B: Targeting Cancer Stem Cells as the Key Driver of Carcinogenesis

and Therapeutic Resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 24:2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Aghaalikhani N, Rashtchizadeh N, Shadpour

P, Allameh A and Mahmoodi M: Cancer stem cells as a therapeutic

target in bladder cancer. J Cell Physiol. 234:3197–3206. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Li Z, Liu J, Fu H, Li Y, Liu Q, Song W and

Zeng M: SENP3 affects the expression of PYCR1 to promote bladder

cancer proliferation and EMT transformation by deSUMOylation of

STAT3. Aging (Albany NY). 14:8032–8045. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Song W, Li Z, Yang K, Gao Z, Zhou Q and Li

P: Antisense lncRNA-RP11-498C9.13 promotes bladder cancer

progression by enhancing reactive oxygen species-induced mitophagy.

J Gene Med. 25:e35272023. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Song W, Yang K, Luo J, Gao Z and Gao Y:

Dysregulation of USP18/FTO/PYCR1 signaling network promotes bladder

cancer development and progression. Aging (Albany NY).

13:3909–3925. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang Y, Zhang X, Huang X, Tang X, Zhang

M, Li Z, Hu X, Zhang M, Wang X and Yan Y: Tumor stemness score to

estimate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem

cells (CSCs) characterization and to predict the prognosis and

immunotherapy response in bladder urothelial carcinoma. Stem Cell

Res Ther. 14:152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ye Y, Li L, Dai Q, Liu Y and Shen L:

Comprehensive analysis of histone methylation modification

regulators for predicting prognosis and drug sensitivity in lung

adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:9919802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

McCabe MT, Mohammad HP, Barbash O and

Kruger RG: Targeting Histone Methylation in Cancer. Cancer J.

23:292–301. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tan Z, Fu S, Feng R, Huang Y, Li N, Wang H

and Wang J: Identification of potential biomarkers for progression

and prognosis of bladder cancer by comprehensive bioinformatics

analysis. J Oncol. 2022:18027062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Xu W, Chen F, Fei X, Yang X and Lu X:

Overexpression of SET and MYND domain-containing protein 2 (SMYD2)

is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in patients

with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 24:7357–7365.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xu H, Ba Z, Liu C and Yu X: Long noncoding

RNA DLEU1 promotes proliferation and glycolysis of gastric cancer

cells via APOC1 upregulation by recruiting SMYD2 to induce

trimethylation of H3K4 modification. Transl Oncol. 36:1017312023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Whelan KA, Chandramouleeswaran PM, Tanaka

K, Natsuizaka M, Guha M, Srinivasan S, Darling DS, Kita Y, Natsugoe

S, Winkler JD, et al: Autophagy supports generation of cells with

high CD44 expression via modulation of oxidative stress and

Parkin-mediated mitochondrial clearance. Oncogene. 36:4843–4858.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu K, Lee J, Kim JY, Wang L, Tian Y, Chan

ST, Cho C, Machida K, Chen D and Ou JJ: Mitophagy controls the

activities of tumor suppressor p53 to regulate hepatic cancer stem

cells. Mol Cell. 68:281–292. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Panigrahi DP, Praharaj PP, Bhol CS,

Mahapatra KK, Patra S, Behera BP, Mishra SR and Bhutia SK: The

emerging, multifaceted role of mitophagy in cancer and cancer

therapeutics. Semin Cancer Biol. 66:45–58. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Lou Y, Ma C, Liu Z, Shi J, Zheng G, Zhang

C and Zhang Z: Antimony exposure promotes bladder tumor cell growth

by inhibiting PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Ecotoxicol Environ

Saf. 221:1124202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nguyen TN, Padman BS and Lazarou M:

Deciphering the molecular signals of PINK1/Parkin mitophagy. Trends

Cell Biol. 26:733–744. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lee J, Liu K, Stiles B and Ou JJ:

Mitophagy and hepatic cancer stem cells. Autophagy. 14:715–716.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Choudhury D, Rong N, Senthil Kumar HV,

Swedick S, Samuel RZ, Mehrotra P, Toftegaard J, Rajabian N,

Thiyagarajan R, Podder AK, et al: Proline restores mitochondrial

function and reverses aging hallmarks in senescent cells. Cell Rep.

43:1137382024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cui B, He B, Huang Y, Wang C, Luo H, Lu J,

Su K, Zhang X, Luo Y, Zhao Z, et al: Pyrroline-5-carboxylate

reductase 1 reprograms proline metabolism to drive breast cancer

stemness under psychological stress. Cell Death Dis. 14:6822023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zietzer A, Hosen MR, Wang H, Goody PR,

Sylvester M, Latz E, Nickenig G, Werner N and Jansen F: The

RNA-binding protein hnRNPU regulates the sorting of microRNA-30c-5p

into large extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles.

9:17869672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Han Y, Liu C, Zhang D, Men H, Huo L, Geng

Q, Wang S, Gao Y, Zhang W, Zhang Y and Jia Z: Mechanosensitive ion

channel Piezo1 promotes prostate cancer development through the

activation of the Akt/mTOR pathway and acceleration of cell cycle.

Int J Oncol. 55:629–644. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dai X, Ren T, Zhang Y and Nan N:

Methylation multiplicity and its clinical values in cancer. Expert

Rev Mol Med. 23:e22021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Hirajima S, Nagata

H, Nishimura Y, Kawaguchi T, Miyamae M, Okajima W, Ohashi T,

Konishi H, et al: Overexpression of SMYD2 contributes to malignant

outcome in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 112:357–364. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

26

|

Zhang Y, Zhou L, Xu Y, Zhou J, Jiang T,

Wang J, Li C, Sun X, Song H and Song J: Targeting SMYD2 inhibits

angiogenesis and increases the efficiency of apatinib by

suppressing EGFL7 in colorectal cancer. Angiogenesis. 26:1–18.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kim K, Ryu TY, Jung E, Han TS, Lee J, Kim

SK, Roh YN, Lee MS, Jung CR, Lim JH, et al: Epigenetic regulation

of SMAD3 by histone methyltransferase SMYD2 promotes lung cancer

metastasis. Exp Mol Med. 55:952–964. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sakamoto LH, Andrade RV, Felipe MS,

Motoyama AB and Pittella Silva F: SMYD2 is highly expressed in

pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and constitutes a bad

prognostic factor. Leuk Res. 38:496–502. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yi X, Jiang XJ and Fang ZM: Histone

methyltransferase SMYD2: Ubiquitous regulator of disease. Clin

Epigenetics. 11:1122019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Migita T, Ueda A, Ohishi T, Hatano M,

Seimiya H, Horiguchi SI, Koga F and Shibasaki F:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition promotes SOX2 and NANOG

expression in bladder cancer. Lab Invest. 97:567–576. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cho HS, Hayami S, Toyokawa G, Maejima K,

Yamane Y, Suzuki T, Dohmae N, Kogure M and Kang D: RB1 methylation

by SMYD2 enhances cell cycle progression through an increase of RB1

phosphorylation. Neoplasia. 14:476–486. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gao RL, Chen XR, Li YN, Yan XY, Sun JG, He

QL and Cai FZ: Upregulation of miR-543-3p promotes growth and stem

cell-like phenotype in bladder cancer by activating the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol.

10:9418–9426. 2017.

|

|

33

|

Hu Y, Zhang Y, Gao J, Lian X and Wang Y:

The clinicopathological and prognostic value of CD44 expression in

bladder cancer: A study based on meta-analysis and TCGA data.

Bioengineered. 11:572–581. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xia P, Liu DH, Xu ZJ and Ren F: Cancer

stem cell markers for urinary carcinoma. Stem Cells Int.

2022:36116772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Cai F, Miao Y, Liu C, Wu T, Shen S, Su X

and Shi Y: Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 promotes

proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer.

Oncol Lett. 15:731–740. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shang L and Wei M: Inhibition of SMYD2

sensitized cisplatin to resistant cells in NSCLC through activating

p53 pathway. Front Oncol. 9:3062019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lin X, Chen JD, Wang CY, Cai Z, Zhan R,

Yang C, Zhang LY, Li LY, Xiao Y, Chen MK and Wu M: Cooperation of

MLL1 and Jun in controlling H3K4me3 on enhancers in colorectal

cancer. Genome Biol. 24:2682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Phoyen S, Sanpavat A, Ma-On C, Stein U,

Hirankarn N, Tangkijvanich P, Jindatip D, Whongsiri P and Boonla C:

H4K20me3 upregulated by reactive oxygen species is associated with

tumor progression and poor prognosis in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma. Heliyon. 9:e225892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhou Z, Zhang B, Deng Y, Deng S, Li J, Wei

W, Wang Y, Wang J, Feng Z, Che M, et al: FBW7/GSK3 β mediated

degradation of IGF2BP2 inhibits IGF2BP2-SLC7A5 positive feedback

loop and radioresistance in lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

43:342024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Abu-Farha M, Lambert JP, Al-Madhoun AS,

Elisma F, Skerjanc IS and Figeys D: The tale of two domains:

proteomics and genomics analysis of SMYD2, a new histone

methyltransferase. Mol Cell Proteomics. 7:560–572. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wang S, Long H, Hou L, Feng B, Ma Z, Wu Y,

Zeng Y, Cai J, Zhang DW and Zhao G: The mitophagy pathway and its

implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

8:3042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Silvian LF: PINK1/parkin pathway

activation for mitochondrial quality control-which is the best

molecular target for therapy? Front Aging Neurosci. 14:8908232022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yuan X, Chen K, Zheng F, Xu S, Li Y, Wang

Y, Ni H, Wang F, Cui Z, Qin Y, et al: Low-dose BPA and its

substitute BPS promote ovarian cancer cell stemness via a

non-canonical PINK1/p53 mitophagic signaling. J Hazard Mater.

452:1312882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Feng X, Yin W, Wang J, Feng L and Kang YJ:

Mitophagy promotes the stemness of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal

stem cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 246:97–105. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Liu D, Sun Z, Ye T, Li J, Zeng B, Zhao Q,

Wang J and Xing HR: The mitochondrial fission factor FIS1 promotes

stemness of human lung cancer stem cells via mitophagy. FEBS Open

Bio. 11:1997–2007. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Vazquez-Martin A, Van den Haute C, Cufi S,

Corominas-Faja B, Cuyàs E, Lopez-Bonet E, Rodr iguez-Gallego E,

Fernández-Arroyo S, Joven J, Baekelandt V and Menendez JA:

Mitophagy-driven mitochondrial rejuvenation regulates stem cell

fate. Aging (Albany NY). 8:1330–1352. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|