Introduction

With an aging population and the continuation of

organized cancer screening programs, gastric cancer (GC) has shown

a consistent trend of increasing morbidity and mortality (1,2).

GC has a significant demographic disparity, with male prevalence

rates nearly twice that of females (1,3).

Geographical variations are also evident, with disproportionately

high incidence rates in East Asia (particularly Japan and Mongolia)

and Eastern Europe, which together account for 87% of GC cases

worldwide (1,3). GC has thus become a global public

health challenge and even surgically treated patients, such as

those with gastric stump cancer, still face a considerable disease

burden and poor outcomes (4). The

low detection rate of early-stage GC can be attributed to the lack

of specific clinical symptoms (5). GC screening can detect precancerous

lesions and early-stage GC in asymptomatic patients, reducing

mortality and improving treatment efficacy (6). The majority (>70%) of patients

are diagnosed at advanced stages, mainly due to the absence of

clinical symptoms during early pathogenesis (7). This delay in diagnosis contributes

to a poor prognosis and the clinical management of GC presents

obvious challenges. Despite the availability of chemotherapy and

radiotherapy, treatment outcomes for advanced gastrointestinal

malignancies, such as pancreatic and GC, remain unsatisfactory

(8). Patients diagnosed at a late

stage have a poor prognosis without targeted treatment (2). Traditional Chinese Medicine

(TCM)-derived polysaccharides, such as Rhizoma Coptidis

polysaccharides and Anemarrhena asphodeloides

polysaccharides, have been explored as adjuncts in GC management

(9,10). To address these clinical

challenges, there is a pressing need to improve our understanding

of the pathogenesis of GC. Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate

the mechanisms associated with the pathogenesis and progression of

GC and to explore potential targets for effective treatment. Such

discoveries are essential for the development of more effective

treatment strategies and improved survival outcomes.

Mitochondria are vital for cellular homeostasis

concerning energy production, calcium regulation and apoptosis.

Their dysfunction has been widely reported to be associated with

neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes and chronic pulmonary

conditions (11-14). Mitophagy, the selective

degradation of defective mitochondria, is essential for maintaining

cellular homeostasis and influencing various cancer-related

pathways. In various types of cancer, including bladder and

colorectal, mitophagy has been linked to survival and therapy

resistance. The influence of mitophagy on tumor microenvironments

and immune responses has the potential to facilitate tumor growth

(15-17). Conversely, the progression of

breast cancer is inhibited by Urolithin A, which activates

transcription factor EB (TFEB)-mediated mitophagy in tumor

macrophages (18). Esophageal

cancer was associated with a reduction in mitophagy, which has been

linked to an increased potential for metastasis (19). These results indicate that

mitophagy inhibition may facilitate tumor spread. Consequently, the

manipulation of mitophagy pathways may present a novel therapeutic

strategy with the potential to enhance treatment outcomes in cancer

management.

The Ras homolog family member T1 (RHOT1) gene

encodes a mitochondrial GTPase that plays a crucial role in various

processes within mitochondria, including mitochondrial transport,

mitochondrial calcium buffering and mitophagy. Its role in disease

pathogenesis, particularly neurodegenerative disorders and

metabolic conditions, has been well-documented. For instance, the

dysfunction of RHOT1 has been demonstrated to disrupt

Parkin-mediated mitophagy, leading to the accumulation of damaged

mitochondria and exacerbating neuronal loss in Parkinson's disease

(20). Additionally, the

dysfunction of RHOT1 has been observed to impede calcium handling

and mitochondrial transport, thereby contributing to metabolic

dysregulation in diabetes (11).

RHOT1 plays a pivotal role in maintaining mitochondrial

quality control and has been identified as essential for preserving

mitochondrial integrity (20). In

GC, increasing research has identified mitochondrial dysfunction as

a pivotal factor driving tumor progression, therapy resistance and

metabolic reprogramming (21-24). Peng et al (25) investigated the correlation between

the expression of RHOT1 and the clinicopathological features of

tumor-node-metastasis staging and lymph node metastasis. RHOT1 has

been thought to serve as a biomarker for GC. However, to date, no

studies have reported the specific role of RHOT1 in the regulation

of mitophagy in GC. Its conserved function in mitochondrial quality

control suggests that aberrant RHOT1 activity may influence tumors

by regulating mitophagy. Consequently, the investigation of RHOT1

in GC cells has the potential to reveal novel associations between

mitochondrial dynamics and oncogenesis, thus providing potential

therapeutic targets for diseases associated with mitochondrial

dysfunction.

The present study hypothesized that RHOT1 may affect

the behavior of GC cells through mitophagy. It aimed to investigate

the role of RHOT1 in regulating mitochondrial quality control,

energy metabolism and mitophagy-related signaling in GC.

Furthermore, its effect on the proliferation, invasion and

migration of GC cells in vitro was examined. These findings

may provide a theoretical basis for considering RHOT1 as a

potential alternative therapeutic target for GC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

The cell lines used were HGC-27, MKN-45, AGS, SNU-1

and GES-1 (human gastric cancer cell lines and a human gastric

epithelial cell line, respectively) obtained from Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd. (cell batch: IM-H084202303). They were

cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; Clark Bioscience), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

μg/ml streptomycin and maintained at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Total RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

RNA Easy Fast Tissue/Cell Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) was prepared for total RNA extraction according to the

manufacturer's instructions under RNase-free conditions. Total RNA

was extracted from GC cell lines (HGC-27, MKN-45, AGS, SNU-1) and

GES-1 after transfection or treatment, depending on the

experimental group. PrimeScript RT Master Mix Kit (Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used for reverse transcription and the

SYBR Green Master Mix Kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was

employed to detect the relative expression of mRNAs. The reaction

conditions were performed under the following conditions: 95°C for

2 min, 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 30 sec for 40

cycles. Primer sequences are presented in Table I. All primers were designed based

on Homo sapiens RefSeq/NCBI sequences and targeted exon-exon

junctions to ensure specificity for mRNA. GAPDH was used to

normalize the gene being tested. All primers were synthesized by

Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. and validated by melt curve analysis and

agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm specificity. Each sample was

run in triplicate using the 7500 Fast (Applied Biosystems; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Gene expression results were expressed as

fold changes relative to GAPDH using the 2-ΔΔCq method

(26).

| Table IPrimer information. |

Table I

Primer information.

| Gene | Forward

(5'-3') | Reverse

(5'-3') | Amplicon size

(bp) | RefSeq/NCBI |

|---|

| RHOT1 |

CTGATTTCTGCAGGAAACACAA |

GCAAAAACAGTAGCACCAAAAC | 142 | NM_001033566.3 |

| PINK1 |

GTGGACCATCTGGTTCAACAGG |

GCAGCCAAAATCTGCGATCACC | 110 | NM_032409.4 |

| Parkin |

CCAGAGGAAAGTCACCTGCGAA |

CTGAGGCTTCAAATACGGCACTG | 125 | NM_004562.3 |

| Tomm20 |

CGACCGCAAAAGACGAAGTGAC |

GCTTCAGCATCTTTAAGGTCAGG | 130 | NM_007019.5 |

| Timm23 |

ACACGAGGTGCAGAAGATGACC |

CTGTCAGACCACCTCGTGCTAT | 115 | NM_006991.3 |

| GAPDH |

GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT |

TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG | 101 | NM_002046.7 |

Short interfering (si)RNA

transfection

Target-specific siRNA (si-RHOT1) (Table II) and a negative control siRNA

(si-NC) were transfected into HGC-27 cells cultured in six-well

plates. Cells were transfected with 20 μM siRNA using Lipo

6000 transfection reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and

then cultured for 48 h at 37°C. The silencing efficiency was

evaluated by qPCR. The si-NC used in the present study was a

non-targeting control siRNA purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd. and its sequence was not disclosed by the manufacturer.

| Table IIsiRNA sequences. |

Table II

siRNA sequences.

| siRNA | Sense (5'-3') | Antisense

(5'-3') |

|---|

| RHOT1-homo-393 |

CCAACACACAUUGUAGAUUTT |

AAUCUACAAUGUGUGUUGGTT |

|

RHOT1-homo-1384 |

GCUAUCUAGGCUAUUCAAUTT |

AUUGAAUAGCCUAGAUAGCTT |

|

RHOT1-homo-1804 |

GCUUAAUCGUAGCUGCAAATT |

UUUGCAGCUACGAUUAAGCTT |

|

RHOT1-homo-1174 |

CCUUUGACAAGCAUGAUUUTT |

AAAUCAUGCUUGUCAAAGGTT |

CCK-8 proliferation assay

Cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8; MedChemExpress) was used

for the detection of proliferation of HGC-27 cells. Cells

(~2×103) were seeded in 100 μl of medium in a

96-well plate and incubated at 37°C. CCK-8 reagent (10 μl)

was added to each well at 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Incubation was

performed at 37°C for 2 h. A microplate reader (Molecular Devices,

LLC) was used to read OD values at 450 nm. Blank control wells

containing medium and CCK-8 reagent without cells were included and

their absorbance values were subtracted from sample readings to

eliminate background interference. Cell proliferation results were

expressed as OD values at 450 nm, normalized to control wells.

Wound healing assay

A wound-healing assay was used to evaluate the

migration ability of HGC-27 cells. Cells were cultured at

3×105/ml per well in a 12-well plate. After 6 h of

incubation, 1 ml of cell medium was added to the 12-well plate. A

20 μl pipette tip was used to create a wound and PBS was

used to wash the slide 2-3 times. Then serum-free medium was

prepared and the images were captured under the microscope at 0, 24

and 48 h. The experiment was performed three times.

Transwell assay

For the Transwell migration assay, 200 μl of

cell suspension was transferred to a Transwell upper chamber

(Corning, Inc.) and 500 μl of medium with 20% FBS was

transferred to a Transwell lower chamber and incubated with 5%

CO2 in a 37°C incubator for 48 h. Finally, 50 μl

of the diluted cell suspension was added to the upper chamber of

the Transwell (Corning, Inc.) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. For

the invasion assay, a layer of Matrigel matrix glue (Corning, Inc.;

ratio of serum-free medium:matrix glue 8:1) was coated within the

lower chamber, and the cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After

incubation, a 4% paraformaldehyde solution was used to fix the

cells in the Transwell. The Transwell was subsequently stained with

0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. Cell counts for migration and

invasion were recorded by bright-field microscopy. Three biological

replicates were performed. The migration and invasion abilities

were expressed as the number of stained cells counted under the

microscope.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed to evaluate the cell

cycle and apoptosis of the cells. HGC-27 cells were stained with

propidium iodide (PI; cat. Y267501; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for the cell cycle assay and Annexin Ⅴ and PI

(Annexin Ⅴ; cat. C1062M; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were

used for the apoptosis assay. Cells were stained with PI for cell

cycle and Annexin Ⅴ and PI for apoptosis at 37°C for 30 min.

FACSCalibur and FACSCelesta (BD Biosciences) were used for cell

cycle and apoptosis detection, respectively. The flow cytometer was

operated with a 488 nm excitation laser at standard power. For cell

cycle analysis, gating was based on PI fluorescence intensity to

distinguish populations with different DNA content, corresponding

to G0/G1, S and G2/M phases. For apoptosis

analysis, gating was performed on Annexin V/PI two-parameter dot

plots to classify cells as viable (Annexin V−/PI−), early apoptotic

(Annexin V+/PI-), or late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+).

Three biological replicates were performed. Cell cycle distribution

was expressed as the percentage of cells in

G0/G1, S and G2/M phases and

apoptosis results were expressed as the percentage of apoptotic

cells.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and

mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

ROS were detected using the Reactive Oxygen Specific

Test Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). ROS levels were

measured using 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA).

HGC-27 cells (1×106) were divided equally. In the

positive control group, 1 μl of Rosup stimulating drug was

added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The treatment group was

directly treated with 10 μM DCFH-DA dissolved in serum-free

culture medium (1 ml) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min.

Fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry at an excitation

wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm and

changes in MMP were detected using the Mitochondrial Membrane

Potential Detection Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The

HGC-27 cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5

min at 37°C and resuspended in 50 mM phosphate-buffered saline (pH

7.0). A total of 5×104 cells collected by centrifugation

were resuspended in 188 μl Annexin V-FITC conjugate. Then 2

μl Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos was added and incubated at 25°C

for 30 min and the cells placed in an ice bath. Fluorescence was

detected by flow cytometry using an excitation wavelength of 579 nm

and an emission wavelength of 599 nm. ROS levels were expressed as

mean fluorescence intensity and MMP was expressed as fluorescence

intensity. The experiment was performed three times.

Bioinformatics analysis

The String website (https://cn.string-db.org/) was used to retrieve target

genes for analysis of protein-protein interactions (PPI). The

species was limited to Homo sapiens and the parameters were

set as follows: Choice of significance term for network edges;

evidence: Choice of active interaction source; experimental: Choice

of minimum required interaction score; confidence: 0.2.

After downloading the enriched gene set,

de-duplication of the gene set was carried out to obtain the set of

interacting genes. The final PPI network map was calculated by

selecting the top 10 pivotal genes in the Hubba node using the

Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/; version 3.8.0)

plugin cyto-Hubba. R software (https://www.r-project.org/; version 3.6.3) was used to

analyze the RHOT1 mRNA expression levels of STAD RNA-seq based on

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and a single-gene

co-expression heatmap was constructed. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses of

selected data were performed using the clusterProfiler package

(https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html;

version 3.14.3) and visualized using the ggplot2 package

(https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html;

version 3.3.3). The intersection of mitophagy genes obtained from

the Reactome database (https://curator.reactome.org; version 87) with those

obtained from the KEGG database was taken and plotted as a Venn

diagram. The expression matrix of 20 mitophagy pathway core genes

was screened based on the intersection of mitophagy pathways from

KEGG and Reactome. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed

(after normalization) using Omicstudio (https://www.omicstudio.cn/tool) and the correlation

heatmap of these core genes was plotted.

Western blotting

Total proteins from transfected HGC-27 cells were

isolated by RIPA buffer (cat. no. R0010; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) and then separated by 8-11% SDS-PAGE.

Protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay

kit (cat. no. WLA019; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.). The 20 μg

protein samples were dissolved and transferred to 0.45 μm

polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (cat. no. IPVH00010;

MilliporeSigma). The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed

milk powder for 2 h at room temperature and then incubated with

primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The antibodies were RHOT1

(cat. no. A5838; 1:500; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), PINK1 (cat.

no. WL04963; 1:500; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.), Parkin (cat. no. WL02512;

1:500; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.), GAPDH (cat. no. 5174, 1:1,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.). The PVDF membranes were then washed

with tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (0.1% TBST-20; cat. GC204002;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no.

WLA023; 1:5,000; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.) for 1.5 h at room

temperature. The membranes were scanned and analyzed using the

Gel-Pro Analyzer 4.5 program for Windows (Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Three biological replicates were performed. Protein expression

levels were expressed as band intensities normalized to GAPDH.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. The findings from each experiment were corroborated

through independent replicates. Normality of data distribution was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test prior to parametric analyses.

For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed unpaired Student's

t-test was applied. For comparisons among multiple groups with a

single variable, one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer post

hoc test was used. For datasets involving more than one variable,

two-way ANOVA with appropriate post-hoc analyses was performed.

SPSS (version 29.0; IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.0;

Dotmatics) were used for statistical analyses. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

RHOT1 is involved in mitophagy via

PINK1/Parkin pathway

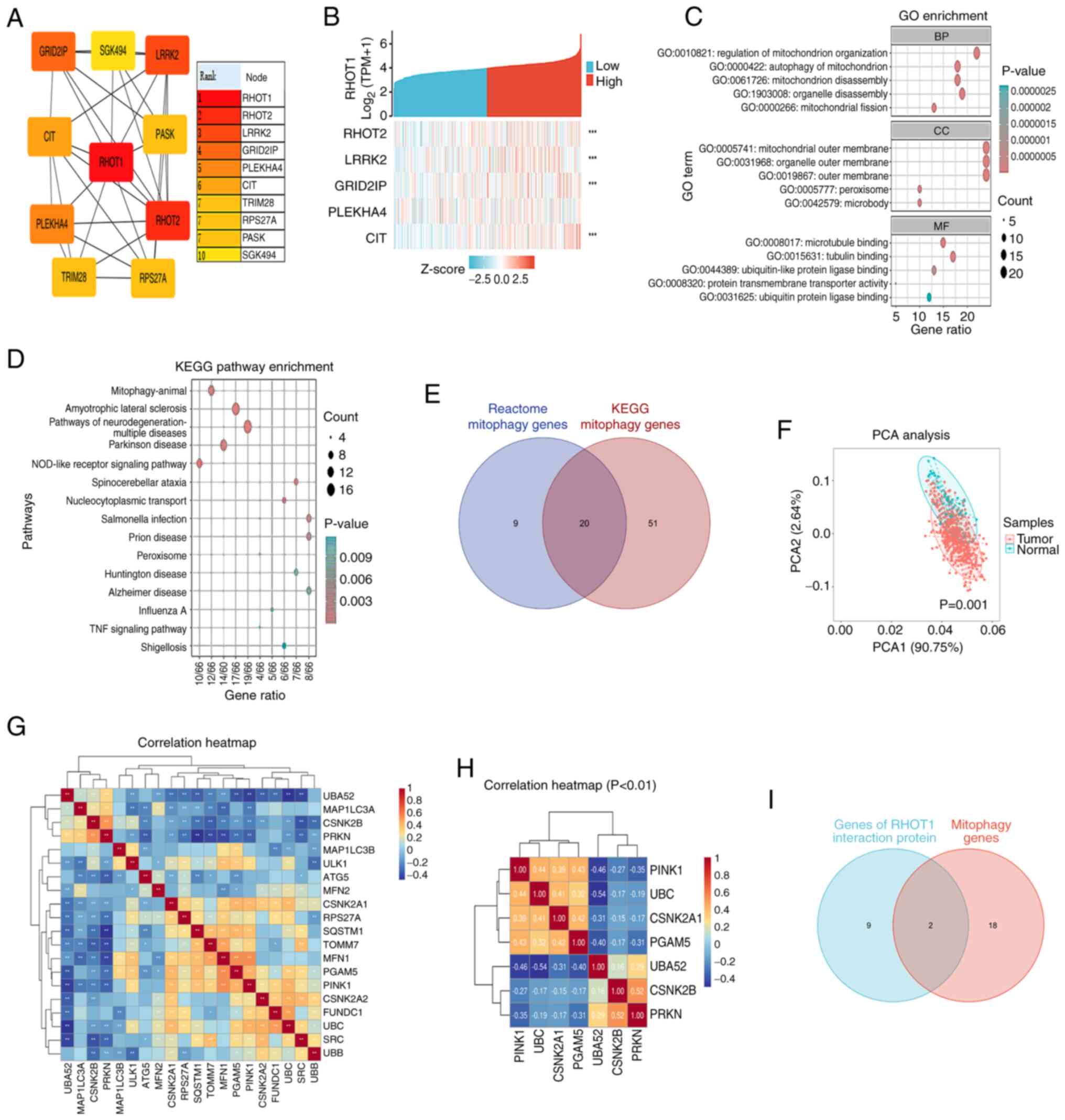

To investigate the function of RHOT1, the

interacting proteins of RHOT1 were investigated from the STRING

search sets. Analysis of RHOT1-interacting proteins identified

RHOT2, LRRK2, GRID2IP, PLEKHA4 and CIT as hub genes

(Fig. 1A). Single-gene

co-expression analysis using TCGA-STAD RNA-seq data showed that

RHOT2, LRRK2, GRID2IP and CIT were significantly

co-expressed with RHOT1 (P<0.001; Fig. 1B). GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

indicated involvement in mitochondrion organization, mitophagy,

microtubule binding and pathways including Parkinson's disease and

neurodegeneration (Fig. 1C and

D).

A Venn diagram identified 20 mitophagy-related genes

from Reactome and KEGG databases (Fig. 1E) and PCA showed significant

differences between tumor and normal groups (Fig. 1F). Next, a correlation heatmap was

constructed from the 20 mitophagy genes (Fig. 1G). The correlation heatmap

displayed the genes with a statistically significant difference

P<0.01 (Fig. 1H). Intersection

of RHOT1-interacting genes and mitophagy genes revealed

PINK1 and Parkin (Fig.

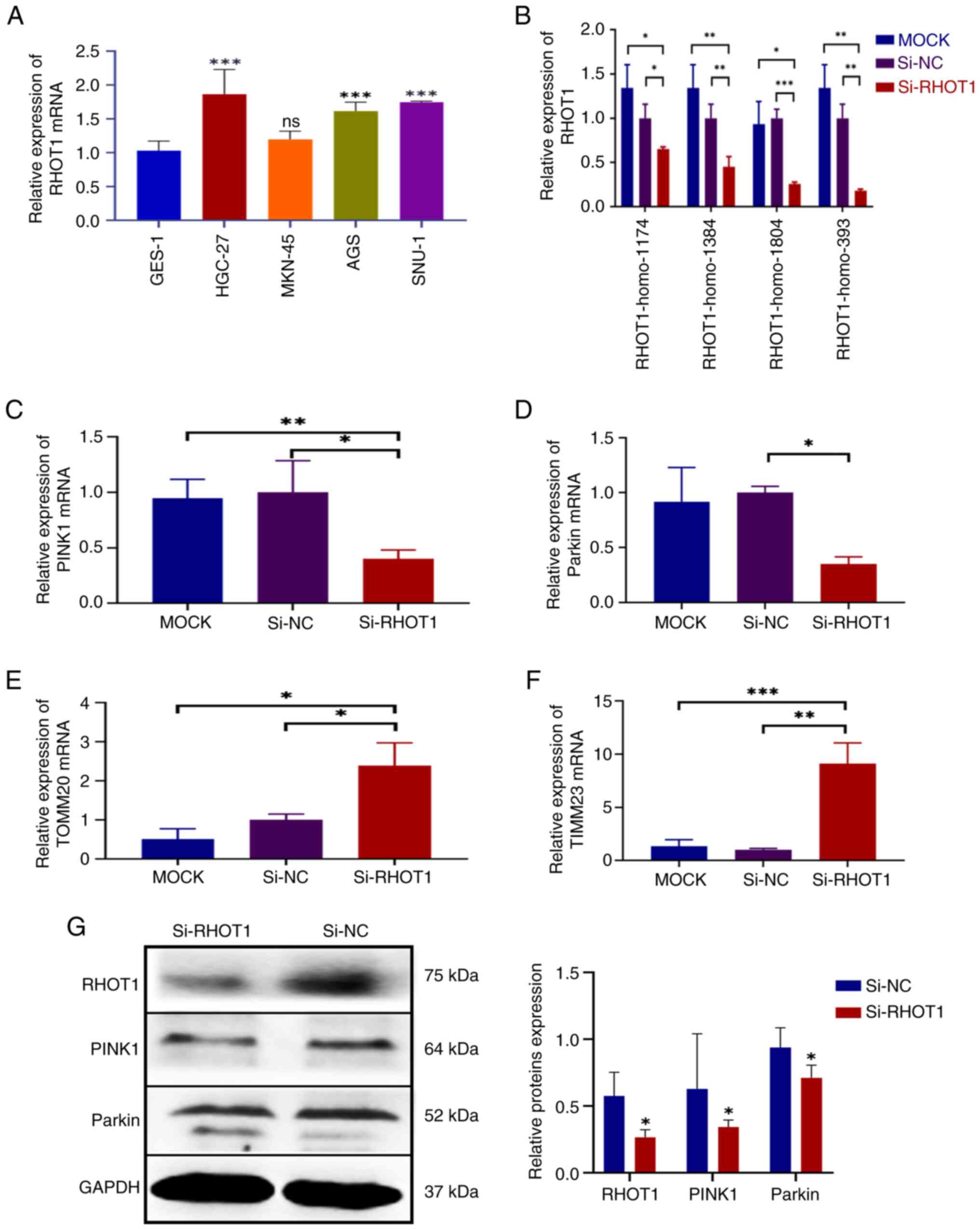

1I). RHOT1 expression was upregulated in GC cell lines

HGC-27, MKN-45, AGS and SNU-1 compared with GES-1, with HGC-27

showing the highest expression (Fig.

2A). Among four siRHOT1 constructs, siRNA RHOT1-homo-393

achieved the highest silencing efficiency (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, the mRNA

expression levels of the genes were examined. The result showed

that the mRNA expression of PINK1 and Parkin were

both downregulated after silencing RHOT1, with PINK1

decreased by 59.75% (P=0.025) and Parkin decreased by 65.12%

compared with the si-NC group (P=0.0189) (Fig. 2C and D). Additionally, the mRNA

expression of mitochondrial membrane-related genes TOMM20

(translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane 20) and

TIMM23 (translocase of the inner mitochondrial membrane 23)

were increased after silencing RHOT1 (Fig. 2E and F). The protein expression of

PINK1 and Parkin were downregulated after silencing RHOT1 (Fig. 2G).

These results indicated that silencing RHOT1 leads

to decreased PINK1 and Parkin expression and inhibition of

mitophagy.

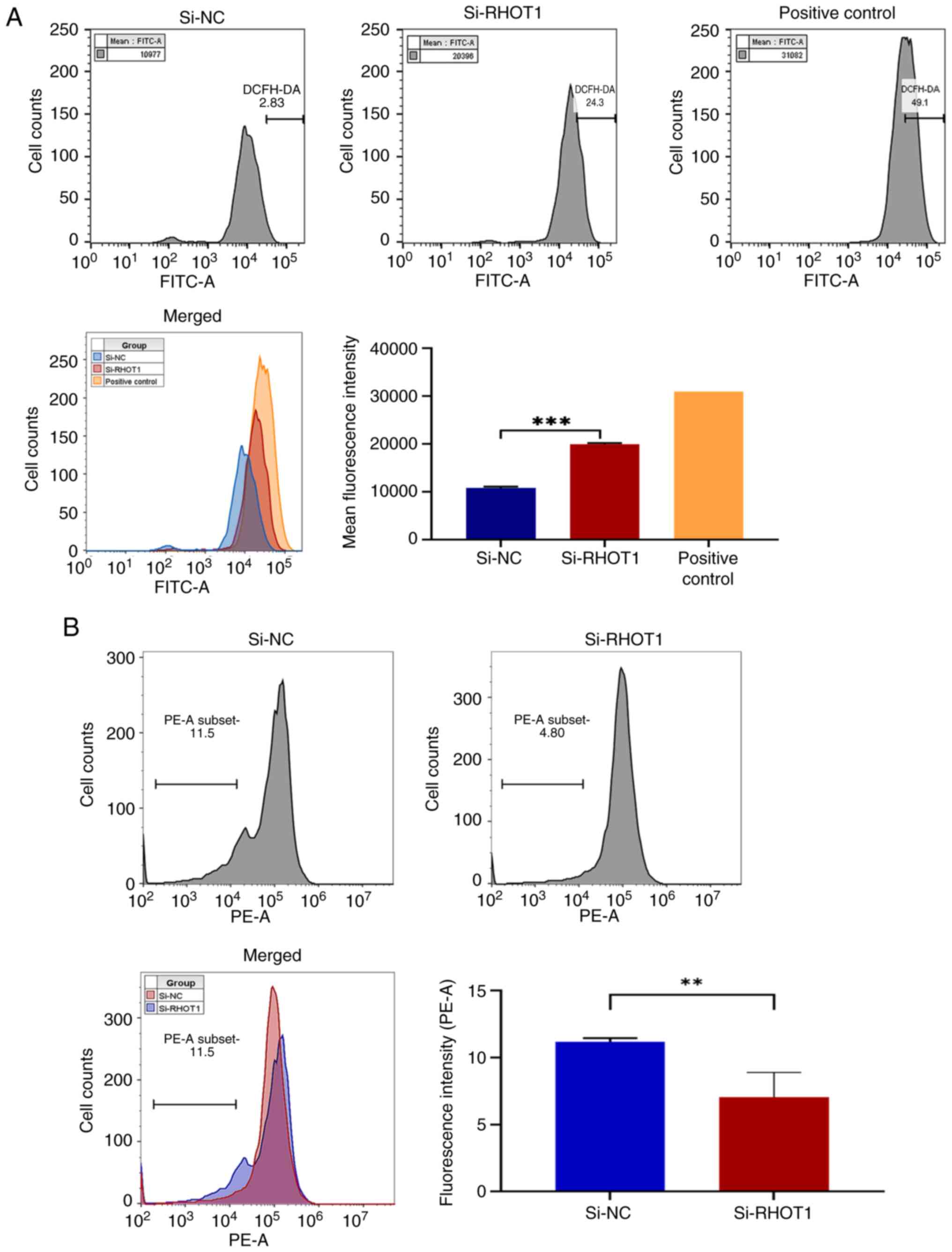

Silencing RHOT1 affects ROS and MMP in GC

cells

Based on the aforementioned results for PINK1,

Parkin and mitochondrial membrane-related genes, mitochondrial

function was further examined to assess mitophagy. Flow cytometry

analysis showed that the average ROS fluorescence intensity in

HGC-27 cells was increased by 84.73% (P<0.001) after silencing

RHOT1 compared with the negative control, while it remained lower

than the positive control (Fig.

3A). MMP assessment indicated that silencing RHOT1 caused a

36.94% decrease in MMP compared with the negative control

(P=0.0061), reflecting mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 3B).

These results demonstrate that silencing RHOT1

elevates ROS levels and depolarizes the mitochondrial membrane,

indicating mitochondrial damage and dysfunction in HGC-27

cells.

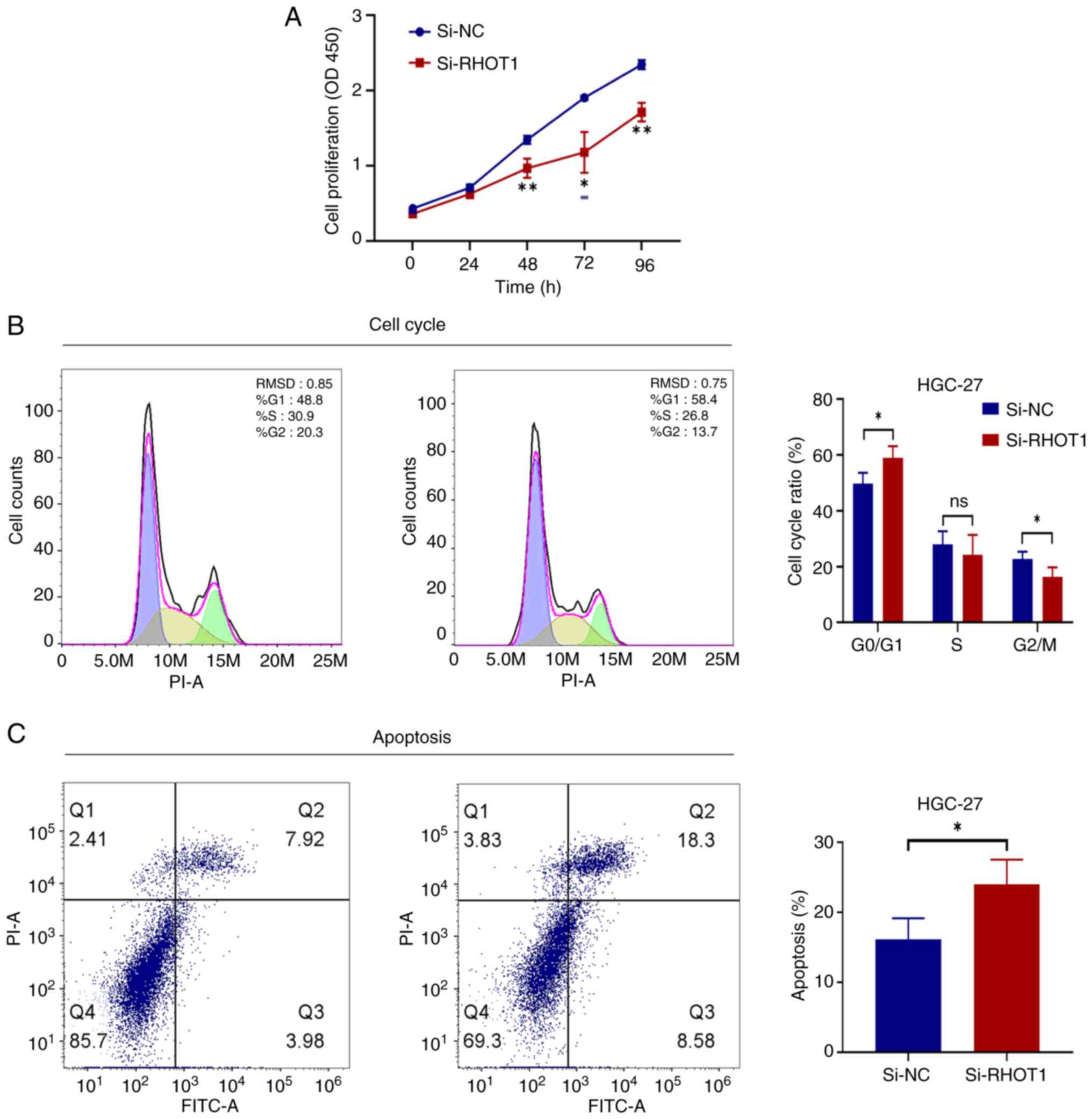

Silencing RHOT1 inhibits the

proliferation of GC cells arrests the cell cycle and promotes cell

apoptosis

Mitochondria were damaged and dysfunctional, which

would cause abnormal cellular energy metabolism and affect cell

growth. The effect of silencing RHOT1 on the growth state and

apoptosis of GC cells was assessed in HGC-27 cells. CCK-8 assay

showed that silencing RHOT1 markedly slowed HGC-27 cell

proliferation from 48 h to 96 h compared with the si-NC group

(Fig. 4A). Flow cytometry

analysis revealed that silencing RHOT1 increased the proportion of

cells in G0/G1 phase, causing cell cycle

arrest. Specifically, the G0/G1 phase

proportion was markedly higher than the si-NC group (P<0.05)

(Fig. 4B). Apoptosis assessment

demonstrated that silencing RHOT1 elevated the percentage of

apoptotic cells compared with the si-NC group (P<0.05) (Fig. 4C).

These results indicated that silencing RHOT1

affected mitophagy to reduce the proliferation of GC cells, arrest

the cell cycle in the G0/G1 phase and promote

cell apoptosis.

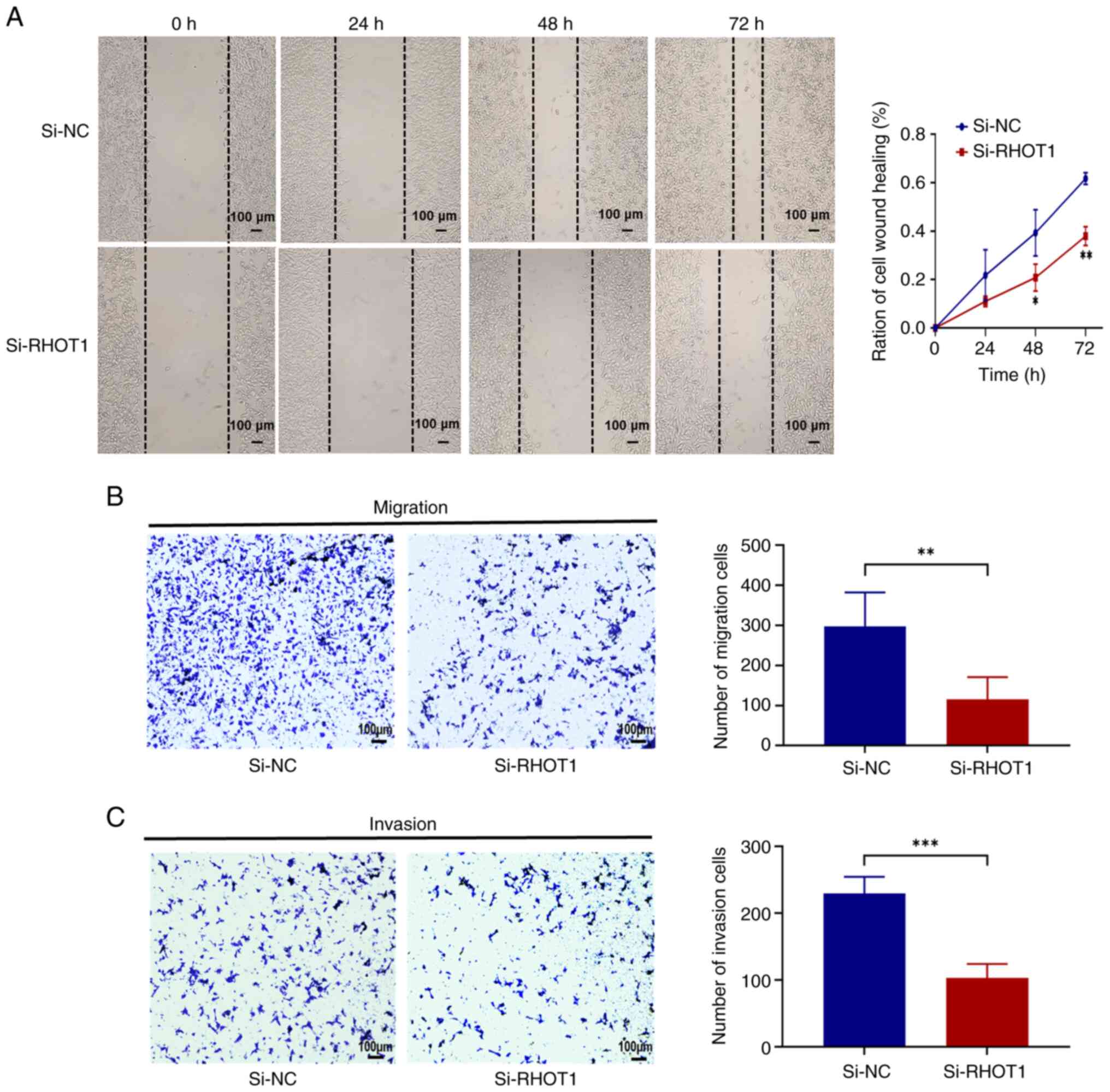

Silencing RHOT1 inhibits the migration

and invasion of GC cells

The present results showed that the expression of

PINK1 and Parkin was downregulated after silencing

RHOT1, so RHOT1 may affect mitophagy, leading to the accumulation

of damaged mitochondria, which further increased ROS and depleted

energy in the cells and consequently affected the invasion and

migration phenotypes of the cells. The effects of RHOT1 on the

invasion and migration of GC cells were subsequently investigated.

Wound healing and Transwell migration assays were employed to

evaluate the migration ability of HGC-27 cells. Wound healing assay

showed that silencing RHOT1 markedly reduced the migration of

HGC-27 cells compared with the si-NC group (Fig. 5A); Transwell migration assay

confirmed that the number of migrating cells in the si-RHOT1 group

was markedly lower than in the si-NC group (P<0.05) (Fig. 5B). Transwell invasion assay

further demonstrated that silencing RHOT1 markedly reduced the

number of invasive HGC-27 cells through Matrigel compared with the

control group (P<0.05; Fig.

5C).

These results indicated that silencing RHOT1

affected mitophagy to reduce the migration and invasion of GC

cells.

Discussion

GC is the fifth most common cause of cancer-related

death worldwide, contributing to 8.8% of all such deaths (27). Screening programs have reduced

mortality in some cancers by detecting early-stage and precancerous

lesions in asymptomatic patients, but organized GC screening has

only been implemented in a few high-prevalence countries (1). The etiology of GC is complex and

multifactorial, with numerous molecular alterations influencing

tumorigenesis and progression through aberrant gene expression or

protein dysfunction (28). At

present, there remains a necessity to explore treatment targets and

effective biomarkers.

Mitochondrial health is critical for cellular

function and mitophagy, the selective degradation of damaged

mitochondria, is central to maintaining mitochondrial quality

(29,30). Mitophagy exerts dual roles in

cancer, either prompting or suppressing carcinogenesis (31). RHOT1, an outer mitochondrial

membrane protein, serves as a molecular switch in the mitochondrial

dynamics and mitophagy (11,20,32). Mutations in RHOT1 disrupt

mitochondria transport, impair quality control and have been linked

to neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's (11,33-35). RHOT1 is upregulated in several

cancers: Jiang et al (36)

predicted its prognostic value in pancreatic cancer and Li et

al (37) found that silencing

RHOT1 inhibited pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and migration.

In mice, RHOT1 knockdown reduced mitochondrial motility and

impaired quality control (38).

It was also found that RHOT1 interacted with LRRK2, consistent with

findings that LRRK2 knockdown or mutation impaired basal mitophagy

(39). Collectively, these data

position RHOT1 as a critical regulator of mitochondrial dynamics

and mitophagy. Database analyses revealed strong associations

between RHOT1 and PINK1/Parkin, the canonical ubiquitin-dependent

mitophagy pathway (40). In the

present study, silencing RHOT1 altered PINK1 and Parkin expression,

suggesting that RHOT1 modulates mitophagy via this axis. GO and

KEGG enrichment of RHOT1-interacting genes further supported

predominant effects on mitochondrial function and the involvement

of the PINK1/Parkin pathway.

Silencing RHOT1 also induced mitochondrial

dysfunction, characterized by increased ROS production and MMP

depolarization. ROS are central regulators of proliferation,

differentiation and metabolism, but excessive ROS promotes

oxidative stress, mtDNA mutations and mitochondrial damage

(41,42). RHOT1 has been implicated in

peroxisomal transport, which contributes to ROS clearance (43,44). Thus, the present findings of ROS

accumulation and MMP depolarization aligned with reports that RHOT1

deficiency aggravates oxidative stress and compromises

mitochondrial homeostasis. Consequently, dysfunctional mitochondria

accumulate, reinforcing oxidative stress and energy imbalance.

In addition, silencing RHOT1 upregulated TOMM20 and

TIMM23, proteins essential for mitochondrial protein import. This

upregulation probably reflects a compensatory response to

mitochondrial stress (45-47),

consistent with previous studies showing increased import machinery

and UPRmt components to preserve organelle integrity (48-50). Thus, RHOT1 deficiency appears to

couple impaired mitophagy with a UPRmt-like compensatory mechanism,

which will be a subgoal for future research.

Mitochondrial dysfunction also influenced cell cycle

progression and apoptosis. Oxidative stress stabilizes p53,

upregulates p21, inhibits CDK2/Cyclin E and blocks G1-S

transition (48,51-53). Disruption of MMP triggers

cytochrome c release, caspase activation and PARP cleavage,

promoting apoptosis (54-56). In agreement, silencing RHOT1 in GC

cells induced G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis,

linking mitochondrial quality control to cell-cycle regulation and

survival. Furthermore, RHOT1 loss impaired migration and invasion.

Reduced ATP production and ROS accumulation inhibit cytoskeletal

remodeling and pseudopodia formation (57,58), while ROS modulates EMT gene

expression via NF-κB and HIF-1α signaling (59). Myc has been shown to

transcriptionally regulate RHOT1, coordinating mitochondrial

trafficking with cytoskeletal dynamics (60). Dysregulated mitophagy and

accumulation of damaged mitochondria further promote tumor

progression (61).

In summary, RHOT1 deficiency in GC cells perturbs

mitophagy, exacerbates oxidative stress, disrupts mitochondrial

homeostasis and impairs key cellular processes, including cell

cycle progression, apoptosis and invasion. These findings

highlighted RHOT1 as a potential therapeutic target in GC. A

potential limitation of the present study is that functional assays

were mainly conducted in the HGC-27 cell line, which showed the

highest RHOT1 expression among the GC cell lines examined. While

this strengthens the rationale for its selection as the primary

model, further validation in additional GC subtypes would help to

generalize the findings. Addressing this limitation will be an

important focus of future research. In addition, the results

remained correlative, as no additional experiments were designed to

directly validate the causal relationship. This limitation was

acknowledged and the findings were therefore interpreted with

caution. Future studies will be required to provide more definitive

evidence of causality.

Silencing RHOT1 induced mitochondrial dynamics

disorder, resulting in the inhibition of the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy

pathway, which impaired mitophagy and caused the accumulation of

intracellular ROS and depolarization of MMP. The aforementioned

multiple ways triggered cell cycle arrest and promoted apoptosis,

resulting in decreased proliferation of GC cells and weakened

invasion and migration ability. Therefore, suppression of RHOT1 may

become a new strategy for the treatment of GC and provide a new

direction for the study of targeted treatment and drug resistance

mechanisms in GC.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YQP and XC conceived and designed the research; YQP,

XC, FK, JZ, SY were responsible for data analysis. RF, JW and YYP

were provided supervision and project administration. XC provided

supervision. YQP wrote the first draft and YYP reviewed and edited

the manuscript. FK, JZ and YYP confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Doctoral Start-up

Foundation of Liaoning Province, China (grant no. 2022-BS-340); the

Science and Technology Research Project of Department of Education

of Liaoning Province (grant no. JYTZD2023145), the Science and

Technology Key Research Project of Liaoning Province (grant no.

2024JH2/102500059) and the Research Project on Integrated

Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine for Chronic Disease

Management (grant no. CXZH2024134).

References

|

1

|

Conti CB, Agnesi S, Scaravaglio M,

Masseria P, Dinelli ME, Oldani M and Uggeri F: Early gastric

cancer: Update on prevention, diagnosis and treatment. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. 20:21492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rocken C: Predictive biomarkers in gastric

cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:467–481. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, Van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Drizlionoks E, Tercioti V Junior, Coelho

Neto JS, Andreollo NA and Lopes LR: Surgical treatment of gastric

stump cancer: A cohort study of 51 patients. Arq Bras Cir Dig.

37:e18502025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang WJ, Zhao HP, Yu Y, Wang JH, Guo L,

Liu JY, Pu J and Lv J: Updates on global epidemiology, risk and

prognostic factors of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol.

29:2452–2468. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Qiu H, Cao S and Xu R: Cancer incidence,

mortality, and burden in China: A time-trend analysis and

comparison with the United States and United Kingdom based on the

global epidemiological data released in 2020. Cancer Commun (Lond).

41:1037–1048. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Veitch AM, Uedo N, Yao K and East JE:

Optimizing early upper gastrointestinal cancer detection at

endoscopy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 12:660–667. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Haggstrom L, Chan WY, Nagrial A, Chantrill

LA, Sim HW, Yip D and Chin V: Chemotherapy and radiotherapy for

advanced pancreatic cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

12:CD0110442024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gao S, Wang Y, Shan Y, Wang W, Li J and

Tan H: Rhizoma Coptidis polysaccharides: Extraction, separation,

purification, structural characteristics and bioactivities. Int J

Biol Macromol. 320(Pt 1): 1456772025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gao S, Xu T, Wang W, Li J, Shan Y, Wang Y

and Tan H: Polysaccharides from Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bge, the

extraction, purification, structure characterization, biological

activities and application of a traditional herbal medicine. Int J

Biol Macromol. 311(Pt 1): 1434972025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kavyashree S, Harithpriya K and Ramkumar

KM: Miro1-a key player in β-cell function and mitochondrial

dynamics under diabetes mellitus. Mitochondrion. 84:1020392025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Li JM, Li X, Chan LWC, Hu R, Zheng T, Li H

and Yang S: Lipotoxicity-polarised macrophage-derived exosomes

regulate mitochondrial fitness through Miro1-mediated mitophagy

inhibition and contribute to type 2 diabetes development in mice.

Diabetologia. 66:2368–2386. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jeong YY, Jia N, Ganesan D and Cai Q:

Broad activation of the PRKN pathway triggers synaptic failure by

disrupting synaptic mitochondrial supply in early tauopathy.

Autophagy. 18:1472–1474. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Maremanda KP, Sundar IK and Rahman I:

Protective role of mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem

cell-derived exosomes in cigarette smoke-induced mitochondrial

dysfunction in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 385:1147882019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li D, Su H, Deng X, Huang Y, Wang Z, Zhang

J, Chen C, Zheng Z, Wang Q, Zhao S, et al: DARS2 promotes bladder

cancer progression by enhancing PINK1-mediated mitophagy. Int J

Biol Sci. 21:1530–1544. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Deng X, Huang Y, Zhang J, Chen Y, Jiang F,

Zhang Z, Li T, Hou L, Tan W and Li F: Histone lactylation regulates

PRKN-Mediated mitophagy to promote M2 Macrophage polarization in

bladder cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 148:1141192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang Z, Yu C, Xie G, Tao K, Yin Z and Lv

Q: USP14 inhibits mitophagy and promotes tumorigenesis and

chemosensitivity through deubiquitinating BAG4 in microsatellite

instability-high colorectal cancer. Mol Med. 31:1632025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zheng B, Wang Y, Zhou B, Qian F, Liu D, Ye

D, Zhou X and Fang L: Urolithin A inhibits breast cancer

progression via activating TFEB-mediated mitophagy in tumor

macrophages. J Adv Res. 69:125–138. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

19

|

Zheng S, Zhang Y, Gong X, Teng Z and Chen

J: CREB1 regulates RECQL4 to inhibit mitophagy and promote

esophageal cancer metastasis. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 75:102–110.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chemla A, Arena G, Sacripanti G, Barmpa K,

Zagare A, Garcia P, Gorgogietas V, Antony P, Ohnmacht J, Baron A,

et al: Parkinson's disease mutant Miro1 causes mitochondrial

dysfunction and dopaminergic neuron loss. Brain. Feb 6–2025.Epub

ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cavinato M: Mitochondrial dysfunction and

cisplatin sensitivity in gastric cancer: GDF15 as a master player.

FEBS J. 291:1111–1114. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lo YL, Wang TY, Chen CJ, Chang YH and Lin

AM: Two-in-one nanoparticle formulation to deliver a tyrosine

kinase inhibitor and microRNA for targeting metabolic reprogramming

and mitochondrial dysfunction in gastric cancer. Pharmaceutics.

14:17592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen W, Zou P, Zhao Z, Weng Q, Chen X,

Ying S, Ye Q, Wang Z, Ji J and Liang G: Selective killing of

gastric cancer cells by a small molecule via targeting TrxR1 and

ROS-mediated ER stress activation. Oncotarget. 7:16593–16609. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rong Y, Teng Y and Zhou X: Advances in the

study of metabolic reprogramming in gastric cancer. Cancer Med.

14:e709482025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Peng YY, Sun D and Xin Y: Hsa_circ_0005230

is up-regulated and promotes gastric cancer cell invasion and

migration via regulating the miR-1299/RHOT1 axis. Bioengineered.

13:5046–5063. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Li M, Pi H, Yang Z, Reiter RJ, Xu S, Chen

X, Chen C, Zhang L, Yang M, Li Y, et al: Melatonin antagonizes

cadmium-induced neurotoxicity by activating the transcription

factor EB-dependent autophagy-lysosome machinery in mouse

neuroblastoma cells. J Pineal Res. 61:353–369. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Procaccio L, Schirripa M, Fassan M,

Vecchione L, Bergamo F, Prete AA, Intini R, Manai C, Dadduzio V,

Boscolo A, et al: Immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancers. Biomed

Res Int. 2017:43465762017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Leites EP and Morais VA: Mitochondrial

quality control pathways: PINK1 acts as a gatekeeper. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 500:45–50. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yao RQ, Ren C, Xia ZF and Yao YM:

Organelle-specific autophagy in inflammatory diseases: A potential

therapeutic target underlying the quality control of multiple

organelles. Autophagy. 17:385–401. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Wang Z, Chen C, Ai J, Shu J, Ding Y, Wang

W, Gao Y, Jia Y and Qin Y: Identifying mitophagy-related genes as

prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets of gastric carcinoma

by integrated analysis of single-cell and bulk-RNA sequencing data.

Comput Biol Med. 163:1072272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Eberhardt EL, Ludlam AV, Tan Z and

Cianfrocco MA: Miro: A molecular switch at the center of

mitochondrial regulation. Protein Sci. 29:1269–1284. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lopez-Domenech G, Howden JH, Covill-Cooke

C, Morfill C, Patel JV, Burli R, Crowther D, Birsa N, Brandon NJ

and Kittler JT: Loss of neuronal Miro1 disrupts mitophagy and

induces hyperactivation of the integrated stress response. EMBO J.

40:e1007152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Diaz-Moreno I and De La Rosa MA: IUBMB

focused meeting/FEBS workshop: Crosstalk between nucleus and

mitochondria in human disease (CrossMitoNus). IUBMB Life.

73:489–491. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Grossmann D, Berenguer-Escuder C, Chemla

A, Arena G and Kruger R: The Emerging role of RHOT1/Miro1 in the

pathogenesis of parkinson's disease. Front Neurol. 11:5872020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jiang H, He C, Geng S, Sheng H, Shen X,

Zhang X, Li H, Zhu S, Chen X, Yang C and Gao H: RhoT1 and Smad4 are

correlated with lymph node metastasis and overall survival in

pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 7:e422342012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li Q, Yao L, Wei Y, Geng S, He C and Jiang

H: Role of RHOT1 on migration and proliferation of pancreatic

cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 5:1460–1470. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lopez-Domenech G, Higgs NF, Vaccaro V, Ros

H, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, Macaskill AF and Kittler JT: Loss of

dendritic complexity precedes neurodegeneration in a mouse model

with disrupted mitochondrial distribution in mature dendrites. Cell

Rep. 17:317–327. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Singh F, Prescott AR, Rosewell P, Ball G,

Reith AD and Ganley IG: Pharmacological rescue of impaired

mitophagy in Parkinson's disease-related LRRK2 G2019S knock-in

mice. Elife. 10:e676042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cao Y, Zheng J, Wan H, Sun Y, Fu S, Liu S,

He B, Cai G, Cao Y, Huang H, et al: A mitochondrial SCF-FBXL4

ubiquitin E3 ligase complex degrades BNIP3 and NIX to restrain

mitophagy and prevent mitochondrial disease. EMBO J.

42:e1130332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lu Y, Li Z, Zhang S, Zhang T, Liu Y and

Zhang L: Cellular mitophagy: Mechanism, roles in diseases and small

molecule pharmacological regulation. Theranostics. 13:736–766.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lemasters JJ: Selective mitochondrial

autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative

stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res.

8:3–5. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Covill-Cooke C, Toncheva VS, Drew J, Birsa

N, Lopez-Domenech G and Kittler JT: Peroxisomal fission is

modulated by the mitochondrial Rho-GTPases, Miro1 and Miro2. EMBO

Rep. 21:e498652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Costello JL, Castro IG, Camoes F, Schrader

TA, Mcneall D, Yang J, Giannopoulou EA, Gomes S, Pogenberg V,

Bonekamp NA, et al: Predicting the targeting of tail-anchored

proteins to subcellular compartments in mammalian cells. J Cell

Sci. 130:1675–1687. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Raiff A, Zhao S, Bekturova A, Zenge C,

Mazor S, Chen X, Ru W, Makaros Y, Ast T, Ordureau A, et al:

TOM20-driven E3 ligase recruitment regulates mitochondrial dynamics

through PLD6. Nat Chem Biol. Apr 22–2025.Epub ahead of print.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Saleem A, Iqbal S, Zhang Y and Hood DA:

Effect of p53 on mitochondrial morphology, import, and assembly in

skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 308:C319–C329. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

47

|

Zha J, Li J, Yin H, Shen M and Xia Y:

TIMM23 overexpression drives NSCLC cell growth and survival by

enhancing mitochondrial function. Cell Death Dis. 16:1742025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kumar N, Shukla A, Kumar S, Ulasov I,

Singh RK, Kumar S, Patel A, Yadav L, Tiwari R, Paswan R, et al: FNC

(4'-azido-2'-deoxy-2'-fluoro(arbino)cytidine) as an effective

therapeutic agent for NHL: ROS generation, cell cycle arrest, and

mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. Cell Biochem Biophys. 82:623–639.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Tian X, Yuan M, Li L, Chen D, Liu B, Zou

X, He M and Wu Z: Enterovirus 71 induces mitophagy via PINK1/Parkin

signaling pathway to promote viral replication. FASEB J.

39:e706592025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Lu J, Zhang Y, Song H, Wang F, Wang L,

Xiong L and Shen X: A novel polysaccharide from tremella fuciformis

alleviated high-fat diet-induced obesity by promoting

AMPK/PINK1/PRKN-Mediated mitophagy in mice. Mol Nutr Food Res.

69:e2024006992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Bai LY, Su JH, Chiu CF, Lin WY, Hu JL,

Feng CH, Shu CW and Weng JR: Antitumor effects of a sesquiterpene

derivative from marine sponge in human breast cancer cells. Mar

Drugs. 19:2442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Bhavya K, Mantipally M, Roy S, Arora L,

Badavath VN, Gangireddy M, Dasgupta S, Gundla R and Pal D: Novel

imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine derivatives induce apoptosis and cell cycle

arrest in non-small cell lung cancer by activating NADPH oxidase

mediated oxidative stress. Life Sci. 294:1203342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Minella AC, Swanger J, Bryant E, Welcker

M, Hwang H and Clurman BE: p53 and p21 form an inducible barrier

that protects cells against cyclin E-cdk2 deregulation. Curr Biol.

12:1817–1827. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Yu C, Sun J, Lai X, Tan Z, Wang Y, Du H,

Pan Z, Chen T, Yang Z, Ye S, et al: Gefitinib induces apoptosis in

Caco-2 cells via ER stress-mediated mitochondrial pathways and the

IRE1alpha/JNK/p38 MAPK signaling axis. Med Oncol. 42:712025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Guefack MF, Talukdar D, Mukherjee R, Guha

S, Mitra D, Saha D, Das G, Damen F, Kuete V and Murmu N: Hypericum

roeperianum bark extract suppresses breast cancer proliferation via

induction of apoptosis, downregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling

cascade and reversal of EMT. J Ethnopharmacol. 319(Pt 1):

1170932024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Huang J, Zhang Y, Cheng A, Wang M, Liu M,

Zhu D, Chen S, Zhao X, Yang Q, Wu Y, et al: Duck Circovirus

genotype 2 ORF3 protein induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial

pathway. Poult Sci. 102:1025332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Peng J, Yang Z, Li H, Hao B, Cui D, Shang

R, Lv Y, Liu Y, Pu W, Zhang H, et al: Quercetin reprograms

immunometabolism of macrophages via the SIRT1/PGC-1alpha signaling

pathway to ameliorate lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative damage.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:55422023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Chen JT, Wei L, Chen TL, Huang CJ and Chen

RM: Regulation of cytochrome P450 gene expression by ketamine: A

review. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 14:709–720. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Qin W, Li C, Zheng W, Guo Q, Zhang Y, Kang

M, Zhang B, Yang B, Li B, Yang H and Wu Y: Inhibition of autophagy

promotes metastasis and glycolysis by inducing ROS in gastric

cancer cells. Oncotarget. 6:39839–39854. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Agarwal E, Altman BJ, Ho Seo J, Bertolini

I, Ghosh JC, Kaur A, Kossenkov AV, Languino LR, Gabrilovich DI,

Speicher DW, et al: Myc regulation of a mitochondrial trafficking

network mediates tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Mol Cell Biol.

39:e00109–19. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Panigrahi DP, Praharaj PP, Bhol CS,

Mahapatra KK, Patra S, Behera BP, Mishra SR and Bhutia SK: The

emerging, multifaceted role of mitophagy in cancer and cancer

therapeutics. Semin Cancer Biol. 66:45–58. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|