Programmed cell death (PCD) is defined as an

intrinsic component of physiological developmental programs or

tissue renewal, occurring independently of exogenous environmental

factors (1). Importantly,

accumulating evidence indicates that PCD has strong effects on a

number of lesions including chronic inflammation and cancer

(2-4). Ferroptosis, a term introduced by

Brent Stockwell in 2012, is a distinct form of iron-dependent PCD

characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides and subsequent

disruption of the cell membrane, ultimately leading to cell death

(5). Recent advances in molecular

biology have revealed the critical involvement of ferroptosis in

the pathophysiology of gastrointestinal diseases, establishing it

as a rapidly evolving research frontier in gastroenterology

(6).

According to the global cancer statistics in 2022

released by GLOBOCAN, gastric cancer (GC) ranks fifth in both

incidence and mortality worldwide, with >950,000 new cases and

>650,000 mortalities in the whole year (7). Helicobacter pylori (H.

pylori) infection, the most prevalent chronic bacterial

infection worldwide, is a major etiological factor for GC (8). Studies have demonstrated that H.

pylori mediates chronic inflammation by upregulating

proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-8, IL-1β and

tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (9-11).

H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis, also referred to as

type B gastritis, can progress to GC through a sequence of

histopathological changes, a process first described in 1975 and

termed as Correa's cascade (12).

Despite significant advancements in the prevention and treatment of

GC based on Correa's cascade, several critical challenges persist.

In the precancerous lesions of GC (PLGC), traditional therapies

such as H. pylori eradication and symptomatic treatment

often fail to effectively suppress chronic inflammation or halt the

progression of Correa's cascade (13,14). Moreover, the early detection of GC

is substantially hampered by the absence of specific clinical

manifestations in the initial stages, the suboptimal sensitivity of

current screening biomarkers, and the low popularity rate of

endoscopic screening (15,16).

Consequently, a substantial proportion of patients are diagnosed at

advanced stages of disease progression. In the management of

advanced GC, several therapeutic limitations remain unresolved,

including the development of chemoresistance, the paucity of novel

molecular targets for targeted therapies, and the low response rate

of immunotherapy, all of which represent pressing unmet needs in

contemporary oncology practice (17-20). Targeted regulation of

ferroptosis-related strategies, characterized by precision

targeting, antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory effects and

potential anticancer activity, represents a promising approach to

overcoming these limitations.

This comprehensive review systematically

investigated the intricate interplay between H. pylori

infection and ferroptosis, while proposing novel promising

strategies for GC prevention and treatment through targeted

regulation of ferroptosis-related pathways across several different

stages of the Correa's cascade.

Oxygen serves as the terminal electron acceptor in

the majority of metabolic oxidation-reduction reactions for most

organisms, highlighting the necessity of oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress induces oxidative modifications of the cell's

bilayer membrane, particularly lipid oxidation, which impacts

various cellular physiological processes such as developmental

regulation, immune response, tumor suppression, metabolic balance

and aging. Ferroptosis, a form of PCD, is characterized by

extensive lipid peroxidation (21). Since its introduction in 2012,

ferroptosis research has centered around several fundamental

components: i) The systemic xc−-glutathione

(GSH)-glutathione peroxidase (GPX)4 ferroptosis suppression

pathway; ii) phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOHs); iii) iron

regulation; iv) GPX4-independent regulatory pathways; and v) other

important regulators such as tumor suppressor p53 and related

signaling pathways.

GSH is a crucial intracellular reductant, and also

functions as a cofactor for enzymes such as GPXs and

GSH-S-transferases. GSH biosynthesis relies on cysteine, which can

be imported from the environment via neutral amino acid

transporters, taken up in its oxidized form (cystine) through the

xc−-cystine/glutamate antiporter system

[comprising solute carrier family 7 member 11 and solute carrier

family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2 subunits)], or synthesized through the

trans-sulfuration pathway utilizing methionine and glucose

(21-23). The transporter protein in the

xc− system is a disulfide-linked heterodimer

consisting of a light chain (xCT) and a heavy chain (4F2hc)

(24). GPX4 plays a pivotal role

in the ferroptosis process, serving as the primary enzyme that

catalyzes the reduction and detoxification of PLOOHs in mammalian

cells (25).

As a type of lipid-derived reactive oxygen species

(ROS), PLOOHs mark the beginning of lipid peroxidation. This

process begins with the abstraction of a bisallylic hydrogen atom

from the polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) acyl chain of

phospholipids within the lipid bilayer, generating a

carbon-centered phospholipid radical (PL•). This radical

subsequently reacts with molecular oxygen to form a phospholipid

peroxyl radical (PLOO•) (26),

which abstracts hydrogen from another PUFA, resulting in PLOOH

formation. In the absence of timely reduction of PLOOHs to their

corresponding alcohols (PLOH) by GPX4, the chain reaction products,

including lipid peroxide breakdown products [e.g., 4-hydroxynonenal

(4-HNE) and malondialdehyde] and oxidized/modified proteins,

disrupt membrane integrity and ultimately lead to organelle and/or

membrane breakdown (21).

The regulation of ferroptosis has emerged as a

critical focus in disease mechanism research. In the context of

ferroptosis modulation, two distinct mechanisms have been

identified: Erastin exerts its effect through indirect inhibition

of GPX4 by targeting system xc, thereby disrupting

cystine uptake, while RSL3 demonstrates direct GPX4 inhibition.

These compounds represent two fundamental classes of ferroptosis

inducers, as indicated in previous studies (27,28). Furthermore, PUFAs and

PUFA-containing lipids within biofilms are susceptible to direct

oxidation by certain lipoxygenases (LOXs), suggesting that LOXs may

also constitute a target for ferroptosis induction (29). Additionally, iron is also crucial

for the regulation of ferroptosis. Inhibition of GPX4 triggers the

Fenton reaction, leading to a rapid accumulation of PLOOHs, a

characteristic of iron toxicity (26). Moreover, it has been shown that

cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase can directly or indirectly trigger

lipid peroxidation by removing hydrogen from PUFAs or by reducing

ferric iron (Fe3+) to its ferrous form (Fe2+)

after its downstream electron acceptor is reduced (30).

Apart from the GSH-GPX4 inhibitory pathway, which is

recognized as the predominant ferroptosis regulatory system

(31), one such mechanism

involves ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1, also known as

AIFM2), which inhibits lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by

synthesizing panthenol and rejuvenating oxidized α-tocopherol

radicals (vitamin E) (32,33).

Another mechanism entails guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase 1

protecting against ferroptosis through its metabolites

tetrahydrobiopterin and dihydrobiopterin (34).

There is compelling evidence linking ferroptosis to

a spectrum of pathologies involving tissue damage, encompassing

cancer, neurodegeneration, inflammation and infection (35). Targeting ferroptosis mostly may

offer a therapeutic avenue for related disorders. However, a number

of cancer cells exhibit heightened vulnerability to ferroptosis,

suggesting its potential as an anticancer strategy. Ferroptosis has

been closely implicated in several cancer-associated signaling

pathways. A study on the interplay between energy stress and

ferroptosis has revealed that energy stress can inhibit ferroptosis

through AMP-activated protein kinase pathway (36). Furthermore, lactate produced by

cancer cells under energy stress may inhibit ferroapoptosis of

tumor cells and promote their metastatic spread (37). The phosphoinositide 3-kinase

(PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)

signaling axis has also been shown to shield cancer cells from

oxidative stress and ferroptosis through sterol regulatory

element-binding protein 1/stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1-mediated lipid

synthesis (38).

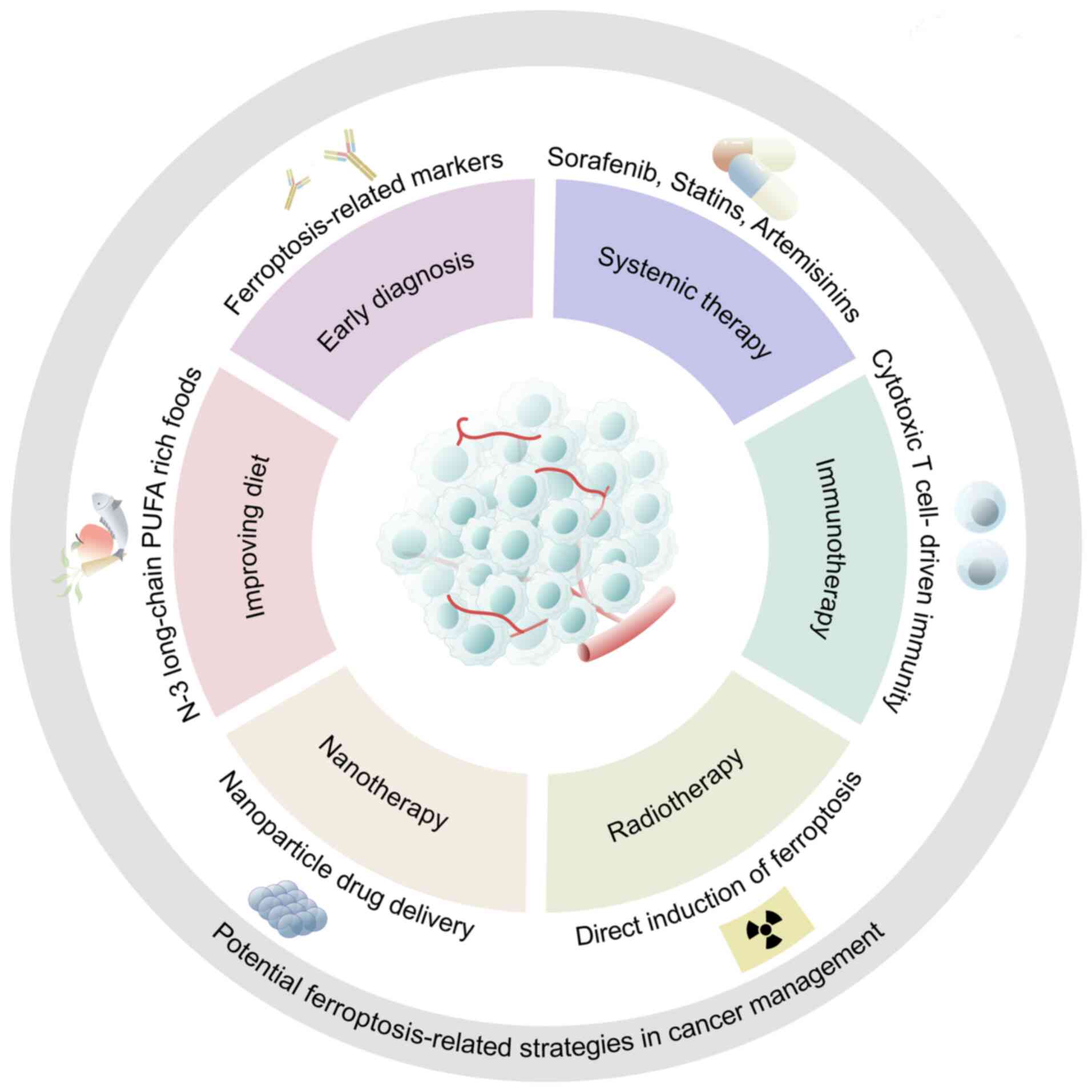

At present, cancer management research targeting

ferroptosis has achieved breakthroughs in a number of aspects

(Fig. 1). First, the

identification of ferroptosis-related biomarkers is one of the

promising strategies in cancer management (47,48). Secondly, in addition to being

transformed in chemoradiotherapy and immunotherapy, therapeutic

strategies to induce ferroptosis have also been applied in the

emerging field of nanotherapy (49). Additionally, some external factors

that can lead to the dysregulation of ferroptosis are also worthy

of attention. It has been documented that some infectious pathogens

such as H. pylori can cause dysregulation of ferroptosis

(50). Furthermore, N-3 PUFA

peroxidation has been shown to selectively induce ferroptosis in

cancer cells. Consequently, N-3 long-chain PUFA-rich foods may be a

dietary strategy for patients with cancer (51). In general, targeting ferroptosis

is a promising strategy for cancer treatment in the future.

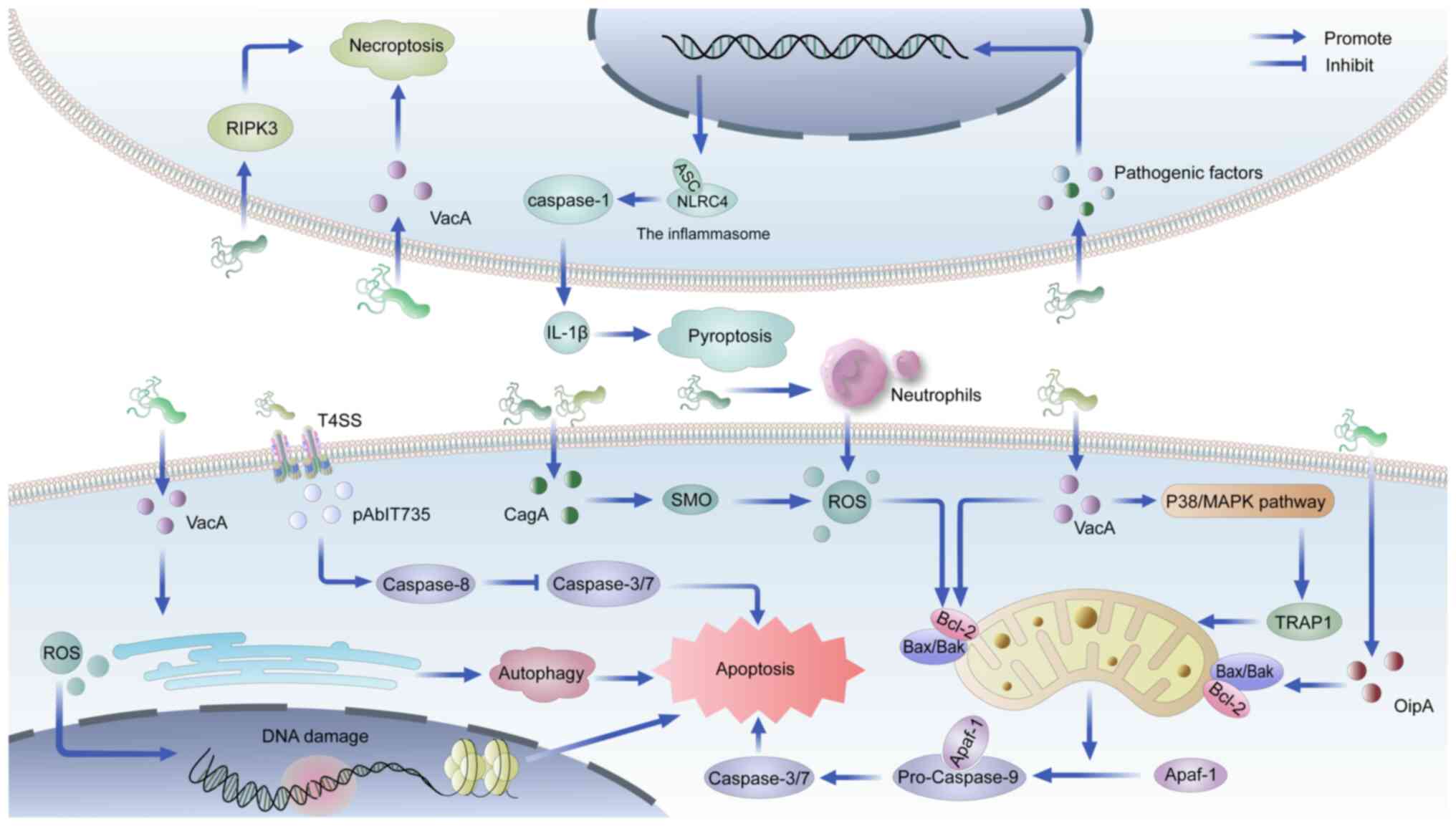

Autophagy and apoptosis represent the most prominent

forms of PCD in GC, with their dysregulation being closely linked

to specific virulence factors of H. pylori infection

(52,53). Vacuolar cell toxin (VacA), a key

virulence factor, induces autophagic cell death through endoplasmic

reticulum (ER) stress in gastric epithelial cells (54), while simultaneously promoting

apoptosis via the p38/MAPK pathway-mediated downregulation of TNF

receptor-associated protein 1 (55). Another critical virulence

determinant, cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), triggers

mitochondrial membrane depolarization by elevating hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2) levels through spermine

oxidase activation, subsequently initiating caspase-dependent

apoptosis (56). The oxidative

stress induced by H. pylori infection, characterized by

excessive production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS)

from neutrophils, leads to DNA damage (57,58), which may be mitigated through

apoptosis induction to prevent oncogenic mutations (59). The mitochondrial apoptotic pathway

is further regulated by H. pylori through modulation of the

B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2)-associated X/Bcl-2 ratio by outer

inflammatory protein A and VacA (60,61).

Accumulating evidence indicates that bacterial

infection can promote ferroptosis following tissue damage.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), for instance, secretes protein

tyrosine phosphatase A, which inhibits GPX4 expression, thereby

inducing ferroptosis and enhancing Mtb pathogenicity and

transmission (66). Similarly,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilizes host polyunsaturated

phosphatidylethanolamine to induce lipid peroxidation and

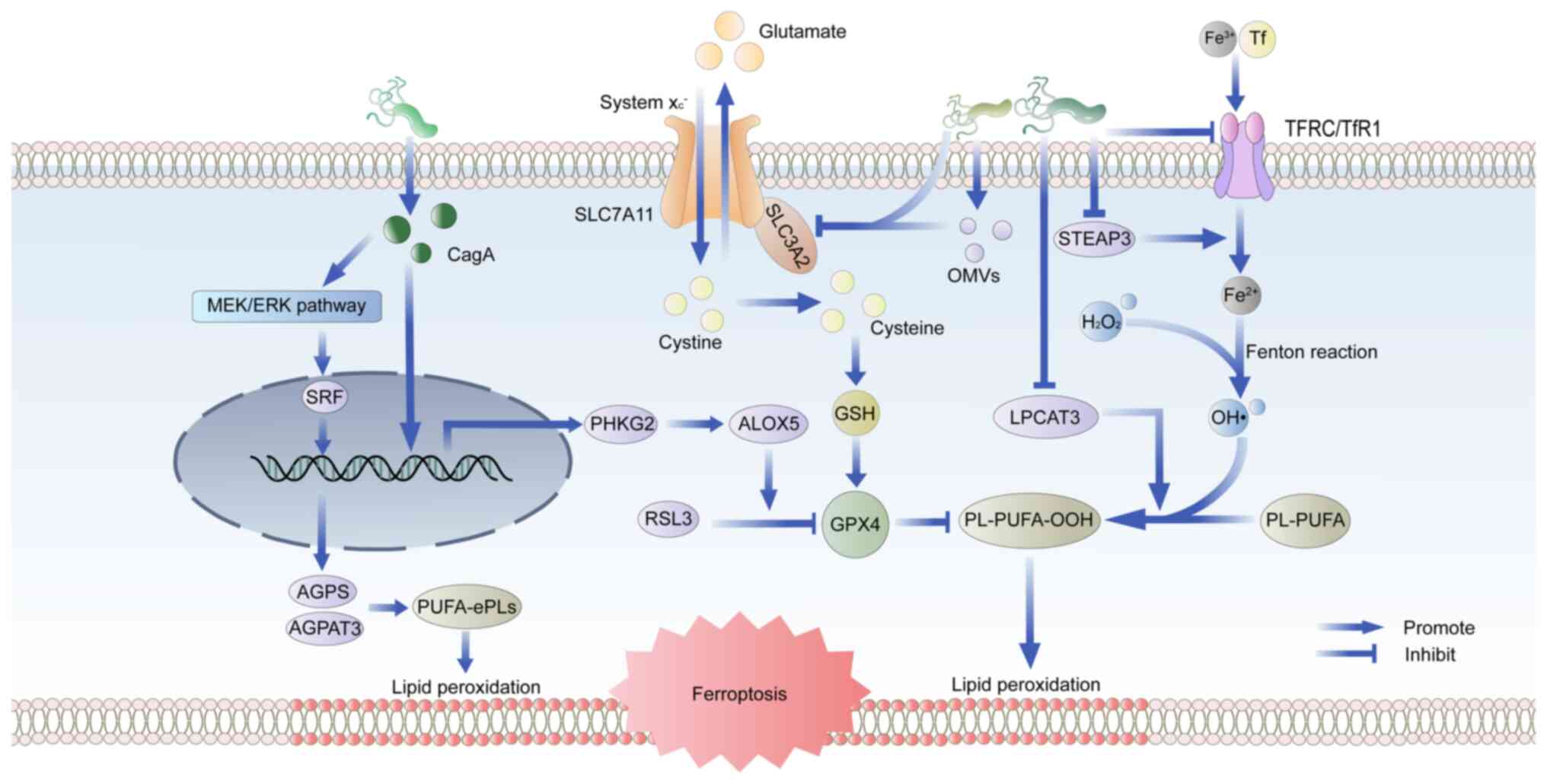

ferroptosis in bronchial epithelial cells (67). H. pylori infection elicits

a robust inflammatory response in the gastric mucosa, leading to

the generation of ROS and RNS, which in turn facilitates lipid

peroxidation (68). In H.

pylori infection, the release of virulence factors also affects

ferroptosis (Fig. 3). Inhibition

of GPX4 by RSL3 renders cells unable to eliminate accumulated lipid

hydroperoxides, ultimately leading to ferroptosis. A study has

corroborated that phosphorylase kinase G2 promotes RSL3-induced

ferroptosis in GC cells by enhancing arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase

expression in CagA-positive H. pylori infections, but the

mechanism of action of CagA in this process requires further

investigation (50). Another

study clarified that CagA could promote the synthesis of

polyunsaturated ether phospholipids through the MEK/ERK/serum

response factor pathway, leading to the susceptibility to

ferroptosis (69). An

investigation into the iron toxicity-associated gene tyrosine

3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein

epsilon (YWHAE) demonstrated significantly elevated YWHAE

expression levels in H. pylori-induced GC, which was

positively correlated with ferroptosis in GC (70).

Notably, ferroptosis interacts with other types of

PCD in the process of GC induced by H. pylori infection.

Ferroptosis-driven lipid peroxidation activates pro-apoptotic

signals, while apoptosis-related proteins (e.g., caspases) may

conversely enhance ferroptosis by degrading inhibitors such as GPX4

(42,73). Autophagy further promotes

ferroptosis sensitivity through ferritin degradation (releasing

free iron) or depletion of antioxidants such as GPX4 (74,75). Additionally, ferroptosis-induced

oxidative stress in the GC microenvironment activates the

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3

inflammasome, triggering IL-1β release and pyroptosis (76). These findings indicate that H.

pylori infection induces dysregulation of multiple PCD

pathways, which functionally interact during tumorigenesis.

Critically, H. pylori-driven PCD dysregulation-including

aberrant ferroptosis-significantly accelerates Correa's cascade of

GC, underscoring H. pylori eradication as a foundational

strategy for GC prevention (77).

Nevertheless, chronic inflammatory responses and pathological

progression frequently persist during intermediate to advanced

precancerous stages despite successful H. pylori eradication

therapy (78,79). This persistent pathological

progression highlights the potential therapeutic value of

strategies targeting various types of PCD, including ferroptosis,

as adjunctive interventions to complement conventional eradication

therapy in PLGC.

Studies on the regulation of ferroptosis not only

provide a new perspective on the pathogenesis of H. pylori

but also provide a direction for exploring new therapeutic targets

in Correa's cascade. The systematic review of ferroptosis in the

three key stages of chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), intestinal

metaplasia (IM) and GC is conducive to bringing new breakthroughs

in the prevention and treatment of GC.

CAG is the initial stage in the 'inflammation-cancer

transformation model'. Knowing how to treat CAG timely and

accurately, and block or reverse the development of CAG to GC is

crucial for the prevention of GC. Conventional therapeutic

approaches for CAG primarily encompass H. pylori eradication

therapy, gastric mucosal protection and gastrointestinal function

enhancement. However, clinical evidence indicates that these

interventions demonstrate limited efficacy in reversing gastric

mucosal damage, particularly in patients presenting with extensive

or moderate-to-severe mucosal atrophy (80). Notably, accumulating evidence from

multiple studies has demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition

of ferroptosis can directly modulate the core pathological

processes of CAG through dual mechanisms: Attenuating gastric

mucosal injury and suppressing inflammatory responses (81,82).

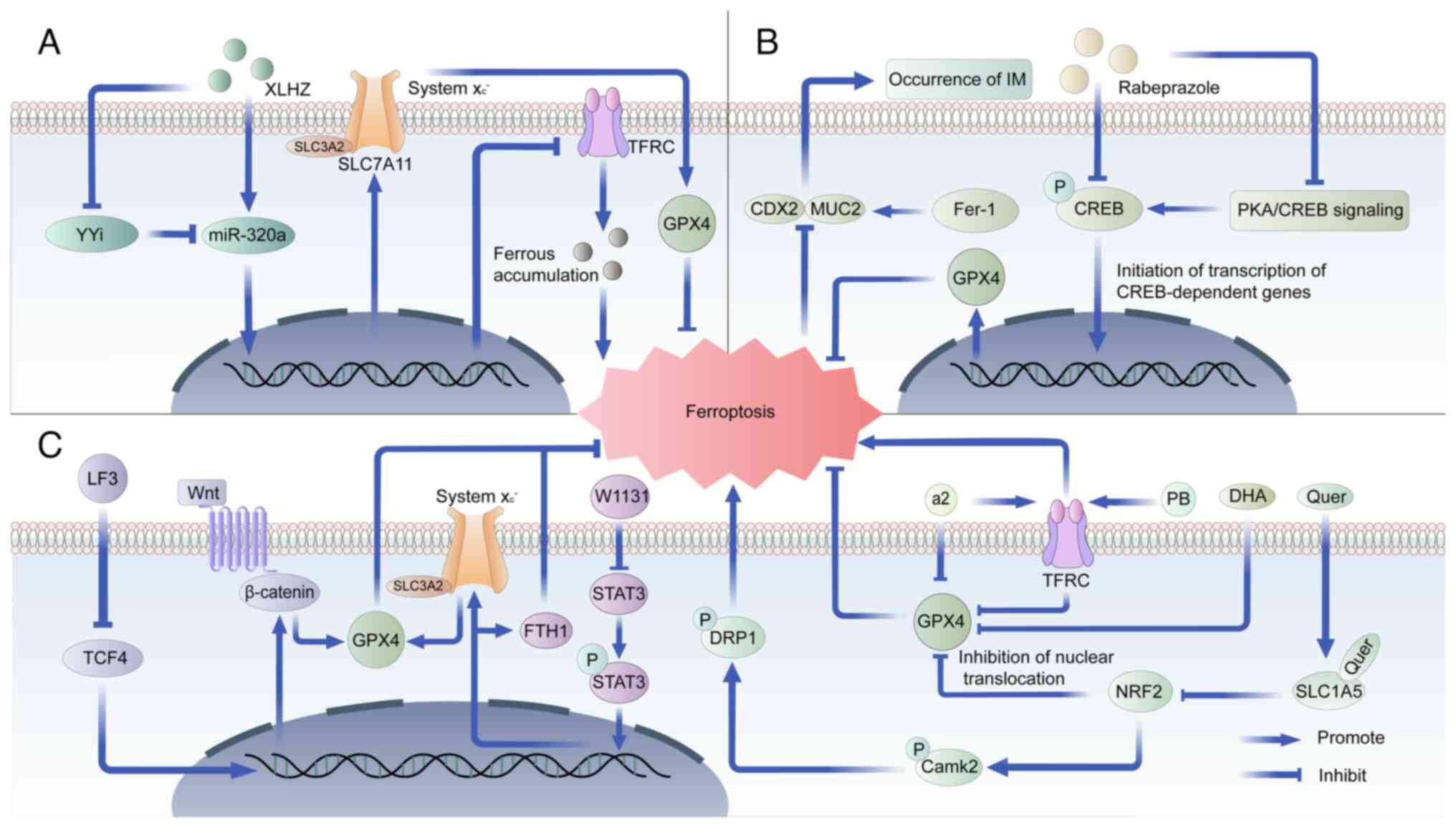

A number of studies have focused on differentially

expressed genes associated with ferroptosis in CAG (83,84). Mechanistically, previous clinical

studies have revealed that patients with CAG frequently exhibit

abnormal iron metabolism or iron deficiency anemia, which is

associated with hepcidin, an antimicrobial polypeptide secreted by

gastric parietal cells (Fig. 4)

(85,86). Hepcidin inhibits iron efflux by

directly binding to ferroportin to cause conformational change and

trigger endocytosis and lysosomal degradation, which plays an

important role in regulating iron balance (87). Furthermore, CAG has been shown to

mediate hepcidin expression via the IL-6/signal transducer and

activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathway, with

increased IL-6 expression being intimately linked to H.

pylori infection (84,88).

Elevated hepcidin levels decrease the expression of divalent metal

transporter 1 and ferroportin 1 proteins, inhibiting duodenal iron

absorption and leading to disrupted iron metabolism and gastric

cell ferroptosis (84).

The current clinical drug mechanisms for the

treatment of CAG mainly include regulation of gastric acid

secretion, eradication of H. pylori, protection of gastric

mucosa and inhibition of inflammatory factors (89). However, due to the limitations and

adverse effects associated with the long-term use of conventional

medications, recent studies have explored the therapeutic efficacy

and underlying mechanisms of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

drugs and natural molecular compounds in CAG, particularly focusing

on their modulation of inflammation and ferroptosis (81,82). One notable study demonstrated that

Xianglianhuazhuo can regulate the Yin Yang 1/miR-320a/TFRC axis,

effectively inhibiting gastric epithelial cell proliferation,

promoting apoptosis, suppressing ferroptosis, ameliorating gastric

mucosa pathology and alleviating CAG symptoms (81). These beneficial effects are

postulated to be related to the anti-inflammatory, anticancer and

antioxidant properties of components like berberine (Fig. 4) (81). Similar studies have also reported

the potential value of Galangin targeting ferroptosis in the

treatment of CAG (82).

Therefore, the therapeutic strategy of inhibiting ferroptosis in

CAG through low-toxicity TCM and natural molecular compounds has

potential.

The most controversial issue regarding the stage of

IM is whether its progression can be reversed by therapeutic

strategies such as eradication of H. pylori (90,91). A previous study has revealed an

important role of apoptosis in the transformation of IM to GC

(92). However, to the best of

our knowledge, there are relatively few studies related to other

types of PCD in IM. Notably, several studies have identified

ferroptosis-related genes in IM as potential biomarkers for IM

diagnosis and novel therapeutic targets such as GOT1, ACSF2, SESN2,

HMOX1 and FTL (93-95). Furthermore, a recent study

reported that ranolrazole could attenuate IM by inhibiting GPX4

expression to enhance ferroptosis (Fig. 4) (96). However, in general, the regulatory

mechanism of ferroptosis in IM remains to be elucidated.

Although progress has been made in exploring

ferroptosis as a therapeutic target for PLGC, significant

limitations remain. First, systematic studies are lacking to

definitively establish whether dysregulated ferroptosis constitutes

a key mechanism driving lesion progression or regression. Due to

the well-documented relationship between ferroptosis and chronic

inflammation, research focusing on the inflammation-cancer

transformation axis may offer an insight in addressing this

fundamental question (97,98).

Secondly, suitable experimental models are still deficient for

elucidating the temporal dynamics and spatial heterogeneity of

ferroptosis regulation within PLGC, particularly in IM. Emerging

technologies such as single-cell sequencing and spatial

transcriptomics, alongside models such as spasmolytic polypeptide

expressing metaplasia, hold promise for providing novel insights

and guiding future experimental designs (99,100). Finally, the related research on

targeting ferroptosis in PLGC is still at the basic theoretical

stage and lacks evidence to achieve clinical translation. The

establishment of gastric organoids derived from CAG/IM patient

tissues may be a key model to highly mimic the in vivo

environment in the future (101).

At present, there are notable issues in the

first-line conventional treatment regimens and experimental novel

treatment regimens for GC. Current therapeutic strategies for GC

face significant challenges in both conventional first-line

treatments and emerging experimental regimens. Persistent issues

including acquired drug resistance, restricted patient eligibility

for targeted therapies and dose-limiting toxicities associated with

combination therapies necessitate urgent optimization (102,103). Furthermore, the clinical

application of innovative approaches such as CAR-T cell therapy is

constrained by suboptimal efficacy and the absence of well-defined

molecular targets, which substantially impedes the advancement of

novel treatment paradigms (104,105).

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that oxidative

stress plays a pivotal role in the initial phases of

inflammation-associated carcinogenesis. Mechanistic studies have

revealed that reduced iron uptake and diminished intracellular iron

reserves may significantly contribute to GC pathogenesis. These

findings provide a compelling rationale for developing targeted

therapeutic strategies against GC through selective induction of

ferroptosis in malignant cells (Table

I) (106-108). The systemic

xc−-GSH-GPX4 pathway plays a pivotal role in

ferroptosis inhibition, thereby promoting the development of GC.

Specifically, the transcription factor megakaryocytic leukemia

factor 1 binds to CArG box sites in the promoters of SLC3A2 and

SLC7A11, enhancing their transcription and subsequently increasing

GSH levels, which inhibits ferroptosis in GC cells (109). Glutamate-cysteine ligase, the

rate-limiting enzyme for GSH synthesis, is crucial for this process

(110). Furthermore, Aldo-keto

reductase 1 member B1 participates in lipid metabolism regulation

by removing the aldehyde group from GSH. It specifically modulates

GPX4 by decreasing ROS accumulation and lipid peroxidation,

lowering intracellular ferrous ion and malondialdehyde levels, and

increasing GSH expression, thereby inhibiting RSL3-induced

ferroptosis in GC.

Previous evidence has increasingly highlighted the

pivotal role of ferroptosis in the metastasis and invasion of GC.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is well recognized as a

critical mechanism driving tumor metastasis. Specifically,

2,2'-dipyridinone hydrazide dithiocarbamate butyrate demonstrates

anticancer efficacy in gastric and esophageal cancer cells. It

inhibits transforming growth factor-β1 in GC cells by inducing

ferritinophagy and activating the p53 and prolyl hydroxylase domain

protein 2/hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) pathways, ultimately

suppressing EMT (111,112). Additionally, its homolog,

2,2'-dipyridyl ketone hydrazine-thiocarbamate, also exhibits

inhibitory effects on EMT in GC cells through the induction of

ferritinophagy and activation of the p53/AKT/mTOR pathway (113). Furthermore, ferroptosis

triggered by ferritin autophagy, coupled with the generation of

excessive ROS, further mediates the suppression of EMT (112). Moreover, A previous study

revealed that the cystatin inhibitor, cystatin SN, regulates GPX4

protein stability by recruiting OTU domain-containing ubiquitin

aldehyde-binding protein 1 to inhibit ferroptosis, thereby

promoting GC metastasis (114).

Collectively, these findings suggest that targets associated with

ferroptosis may offer promising avenues for inhibiting tumor

metastasis and progression.

Epigenetic modulation of ferroptosis also

constitutes a pivotal mechanism in the development and progression

of GC. A recent study has demonstrated that mesenchymal GC cells

exhibit upregulated expression of very long chain fatty acid

elongation protein 5 and fatty acid desaturase 1, sensitizing them

to ferroptosis. Conversely, intestinal-type GC cells display

resistance to ferroptosis due to the silencing of these enzymes via

DNA methylation (115).

Additionally, non-coding RNAs are linked to ferroptosis regulation.

Furthermore, research on long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) PMAN has

revealed that HIF-1α inhibits ferroptosis in peritoneal metastasis

of GC by upregulating lncRNA-PMAN, which is highly expressed in

peritoneal metastases and is associated with poor prognosis

(116).

The induction of ferroptosis as a novel strategy for

the treatment of GC has made some achievements in recent years. On

the one hand, emerging studies indicate that novel molecular

compounds exert antitumor effects in GC through ferroptosis

induction, offering a promising therapeutic alternative for

patients with compromised tolerance to conventional

chemoradiotherapy-associated systemic toxicity (Fig. 4) (117-120). On the other hand, inducing

ferroptosis to improve the chemoresistance of GC has been shown to

be an indirect way to inhibit the development of GC. Related

studies have further explored and developed substances that can

regulate ferroptosis-related genes (121,122) (Fig. 4). Ferroptosis negative

regulation-related genes (GPX4, SLC7A11 and ferritin heavy chain 1)

and STAT3 have been reported to be upregulated in 5-FU-resistant

cells and xenografts (121).

W1131 can alleviate chemoresistance in GC by inducing ferroptosis

as a novel STAT3 inhibitor, which makes it combine with

chemotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of chemotherapy-resistant

GC (121). In addition to the

aforementioned strategies, there are some innovative studies that

provide novel perspectives for the treatment of GC. One study has

proposed that atanorin driven by nanomaterials superparamagnetic

iron oxide nanoparticles can be used to induce ferroptosis of GC

stem cells (122).

In summary, ferroptosis-targeting strategies hold

significant therapeutic promise for GC. However, several key

challenges require further elucidation. The current mechanistic

understanding remains insufficient. Critical unresolved questions

include the differential regulation of ferroptosis across molecular

GC subtypes and the influence of the tumor microenvironment on

ferroptosis sensitivity (123,124). Future investigations should

prioritize applying single-cell multi-omics analyses and GC

organoid/immune cell co-culture models to address these gaps

(124). In addition, the

clinical translation of ferroptosis induction faces substantial

limitations. Specifically, existing ferroptosis inducers lack

tumor-specific targeting, and the synergistic potential of

ferroptosis induction combined with immunotherapy or targeted

therapy lacks robust theoretical and experimental validation.

Consequently, future research efforts should focus on integrating

advanced drug delivery technologies (e.g., responsive nanocarriers)

and rigorously exploring novel combination therapeutic strategies

(125,126).

The high diagnosis rate of advanced GC indicates

that the prevention and treatment of GC remain to be improved. The

prognostic markers related to ferroptosis screened by relevant

studies have important clinical significance in guiding the

treatment of GC (Table II). A

study from Japan investigated the relationship between GPX4, FSP1

and 4-HNE in tissues of patients with GC and their prognosis

(127). In this study, by

combining 163 pT3 or pT4 GC tissue samples and OS analysis, it was

found that patients with high GPX4 expression and low 4-HNE

accumulation had a poor prognosis (P=0.023), while patients with

low FSP1 expression and high 4-HNE accumulation had an improved

prognosis (P=0.033) (127). The

results also suggest that GPX4 and FSP1 may be potential

therapeutic targets for patients with GC with poor prognosis.

SLC2A3 is another ferroptosis marker. Univariate and multivariate

Cox regression analysis revealed that high expression of SLC2A3 was

associated with poor prognosis of patients with GC. Functional

enrichment analysis showed that SLC2A3 was related to

cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, epithelial-mesenchymal

transition, T cell receptor signaling pathway, B cell receptor

signaling pathway, immune checkpoints and tumor microenvironment

regulation. SLC2A3 and related miRNAs are potential prognostic

biomarkers and therapeutics (128).

In addition, lncRNAs can regulate ferroptosis on the

epigenetic mechanism of GC, and the use of a variety of lncRNAs to

construct GC risk models has shown great advantages. A relative

study developed a novel ferroptosis-related prognostic model

incorporating 2 mRNAs and 15 lncRNAs to predict outcomes in

patients with GC. The model combined clinical features and key

factors, showed good predictive ability, and performed well in

external patient data validation, which is expected to improve the

clinical treatment effect of patients with GC (129). Another study identified 26

ferroptosis-related lncRNAs with independent prognostic value and

constructed a risk score model based on four high-risk lncRNAs

associated with poor prognosis of gastric adenocarcinoma (130).

Ferroptosis, a newly identified form of regulated

cell death, plays a key role in numerous physiological and

pathological processes. While significant progress has been made in

elucidating the molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis through basic

research, its precise role in diseases-particularly H.

pylori-associated GC-remains incompletely understood. In the

context of limited effective treatments for GC, systematic

investigations into ferroptosis dysregulation during H.

pylori pathogenesis and the identification of

ferroptosis-related therapeutic targets within Correa's cascade are

critical for developing novel and effective strategies. By

integrating multidisciplinary approaches, including systems

biology, nanotechnology and computational drug design, innovative

drug platforms can be developed to precisely modulate ferroptosis

pathways. These advancements could pave the way for novel

strategies to halt or even reverse the progression of Correa's

cascade. In conclusion, targeting ferroptosis represents a

promising strategy with significant potential for the timely

intervention of PLGC, as well as the early diagnosis and precision

treatment of GC.

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

CW wrote the manuscript. MW and CX revised the

manuscript. CY and MW contributed to the manuscript equally. All

authors have read and approved the final read manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

These authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Huan Wang of

the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang,

China) for her guidance in the development of the framework for the

article as well as her help in writing this paper.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82100599 and 82560121); the Jiangxi

Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant no.

20242BAB26122); the Science and Technology Plan of Jiangxi

Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant

no. 2023Z021); the Project of Jiangxi Provincial Academic and

Technical Leaders Training Program for Major Disciplines (grant no.

20243BCE51001); and the Ganpo Talent Program - Innovative High end

Talents (grant no. gpyc20240212).

|

1

|

Yuan J and Ofengeim D: A guide to cell

death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25:379–395. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Koren E and Fuchs Y: Modes of regulated

cell death in cancer. Cancer Discov. 11:245–265. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kolb JP, Oguin TH III, Oberst A and

Martinez J: Programmed Cell Death and Inflammation: Winter Is

Coming. Trends Immunol. 38:705–718. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tong X, Tang R, Xiao M, Xu J, Wang W,

Zhang B, Liu J, Yu X and Shi S: Targeting cell death pathways for

cancer therapy: Recent developments in necroptosis, pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, and cuproptosis research. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Escuder-Rodríguez JJ, Liang D, Jiang X and

Sinicrope FA: Ferroptosis: Biology and Role in Gastrointestinal

Disease. Gastroenterology. 167:231–249. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Moss SF, Shah SC, Tan MC and El-Serag HB:

Evolving Concepts in Helicobacter pylori Management.

Gastroenterology. 166:267–283. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lei CQ, Wu X, Zhong X, Jiang L, Zhong B

and Shu HB: USP19 Inhibits TNF-α- and IL-1β-Triggered NF-κB

Activation by Deubiquitinating TAK1. J Immunol. 203:259–268. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bartchewsky W Jr, Martini MR, Masiero M,

Squassoni AC, Alvarez MC, Ladeira MS, Salvatore D, Trevisan M,

Pedrazzoli J Jr and Ribeiro ML: Effect of Helicobacter pylori

infection on IL-8, IL-1beta and COX-2 expression in patients with

chronic gastritis and gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol.

44:153–161. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

El Filaly H, Desterke C, Outlioua A, Badre

W, Rabhi M, Karkouri M, Riyad M, Khalil A, Arnoult D and Akarid K:

CXCL-8 as a signature of severe Helicobacter pylori infection and a

stimulator of stomach region-dependent immune response. Clin

Immunol. 252:1096482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, Tannenbaum

S and Archer M: A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet.

2:58–60. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tahara S, Tahara T, Horiguchi N, Kato T,

Shinkai Y, Yamashita H, Yamada H, Kawamura T, Terada T, Okubo M, et

al: DNA methylation accumulation in gastric mucosa adjacent to

cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Int J Cancer.

144:80–88. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Qu X and Shi Y: Bile reflux and bile acids

in the progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia. Chin Med J

(Engl). 135:1664–1672. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Matsuoka T and Yashiro M: Novel biomarkers

for early detection of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol.

29:2515–2533. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bae S, Lee H, Her EY, Lee K, Kim JS, Ahn

J, Choi IJ, Jun JK, Choi KS and Suh M: Cost Utility analysis of

National cancer screening program for gastric cancer in Korea: A

markov model analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 40:e432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sugimoto N, Kawada J, Oka Y, Ueda S,

Murakami K, Nishikawa K, Kurokawa Y, Fujitani K, Kawakami H, Endo

S, et al: Salvage-line of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin therapy

(XELOX) for patients with inoperable/advanced gastric cancer

resistant/intolerant to cisplatin (OGSG1403). Anticancer Res.

45:307–313. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nakamura Y, Kawazoe A, Lordick F,

Janjigian YY and Shitara K: Biomarker-targeted therapies for

advanced-stage gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction cancers: An

emerging paradigm. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:473–487. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shitara K, Özgüroğlu M, Bang YJ, Di

Bartolomeo M, Mandalà M, Ryu MH, Fornaro L, Olesiński T, Caglevic

C, Chung HC, et al: Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously

treated, advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer

(KEYNOTE-061): A randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial.

Lancet. 392:123–133. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M,

Garrido M, Salman P, Shen L, Wyrwicz L, Yamaguchi K, Skoczylas T,

Campos Bragagnoli A, et al: First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy

versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal

junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): A

randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 398:27–40. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bannai S and Kitamura E: Transport

interaction of L-cystine and L-glutamate in human diploid

fibroblasts in culture. J Biol Chem. 255:2372–2376. 1980.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T and Bannai S:

Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate

exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J Biol

Chem. 274:11455–11458. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sato H, Tamba M, Kuriyama-Matsumura K,

Okuno S and Bannai S: Molecular cloning and expression of human

xCT, the light chain of amino acid transport system xc. Antioxid

Redox Signal. 2:665–671. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ursini F, Maiorino M, Valente M, Ferri L

and Gregolin C: Purification from pig liver of a protein which

protects liposomes and biomembranes from peroxidative degradation

and exhibits glutathione peroxidase activity on phosphatidylcholine

hydroperoxides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 710:197–211. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Conrad M and Pratt DA: The chemical basis

of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 15:1137–1147. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yang WS and Stockwell BR: Synthetic lethal

screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent,

nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells.

Chem Biol. 15:234–245. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC and

Stockwell BR: Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents

using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor

cells. Cancer Cell. 3:285–296. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Cao Z, Liu X, Zhang W, Zhang K, Pan L, Zhu

M, Qin H, Zou C, Wang W, Zhang C, et al: Biomimetic macrophage

membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles induce ferroptosis by promoting

mitochondrial damage in glioblastoma. ACS Nano. 17:23746–23760.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zou Y, Li H, Graham ET, Deik AA, Eaton JK,

Wang W, Sandoval-Gomez G, Clish CB, Doench JG and Schreiber SL:

Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase contributes to phospholipid

peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 16:302–309. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Liu Y, Wan Y, Jiang Y, Zhang L and Cheng

W: GPX4: The hub of lipid oxidation, ferroptosis, disease and

treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1878:1888902023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong

L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, et al:

The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit

ferroptosis. Nature. 575:688–692. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M,

da Silva MC, Ingold I, Goya Grocin A, Xavier da Silva TN, Panzilius

E, Scheel CH, et al: FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis

suppressor. Nature. 575:693–698. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP cyclohydrolase

1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 6:41–53. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tang D, Chen X, Kang R and Kroemer G:

Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell

Res. 31:107–125. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

36

|

Lee H, Zandkarimi F, Zhang Y, Meena JK,

Kim J, Zhuang L, Tyagi S, Ma L, Westbrook TF, Steinberg GR, et al:

Energy-stress-mediated AMPK activation inhibits ferroptosis. Nat

Cell Biol. 22:225–234. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhao Y, Li M, Yao X, Fei Y, Lin Z, Li Z,

Cai K, Zhao Y and Luo Z: HCAR1/MCT1 regulates tumor ferroptosis

through the lactate-mediated AMPK-SCD1 activity and its therapeutic

implications. Cell Rep. 33:1084872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yi J, Zhu J, Wu J, Thompson CB and Jiang

X: Oncogenic activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling suppresses

ferroptosis via SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

117:31189–31197. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu J, Minikes AM, Gao M, Bian H, Li Y,

Stockwell BR, Chen ZN and Jiang X: Intercellular interaction

dictates cancer cell ferroptosis via NF2-YAP signalling. Nature.

572:402–406. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

van Roy F and Berx G: The cell-cell

adhesion molecule E-cadherin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 65:3756–3788.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kim NG, Koh E, Chen X and Gumbiner BM:

E-cadherin mediates contact inhibition of proliferation through

Hippo signaling-pathway components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:11930–11935. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T,

Hibshoosh H, Baer R and Gu W: Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated

activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 520:57–62. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tarangelo A, Magtanong L, Bieging-Rolett

KT, Li Y, Ye J, Attardi LD and Dixon SJ: p53 suppresses metabolic

stress-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells. Cell Rep. 22:569–575.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xie Y, Zhu S, Song X, Sun X, Fan Y, Liu J,

Zhong M, Yuan H, Zhang L, Billiar TR, et al: The tumor suppressor

p53 limits ferroptosis by blocking DPP4 activity. Cell Rep.

20:1692–1704. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Guo J, Xu B, Han Q, Zhou H, Xia Y, Gong C,

Dai X, Li Z and Wu G: Ferroptosis: A novel anti-tumor action for

cisplatin. Cancer Res Treat. 50:445–460. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

46

|

Lachaier E, Louandre C, Godin C, Saidak Z,

Baert M, Diouf M, Chauffert B and Galmiche A: Sorafenib induces

ferroptosis in human cancer cell lines originating from different

solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 34:6417–6422. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang X, Hong B, Li H, Sun Z, Zhao J, Li

M, Wei D, Wang Y and Zhang N: Disulfidptosis and ferroptosis

related genes define the immune microenvironment and NUBPL serves

as a potential biomarker for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy

response in bladder cancer. Heliyon. 10:e376382024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kuang Y, Yang K, Meng L, Mao Y, Xu F and

Liu H: Identification and validation of ferroptosis-related

biomarkers and the related pathogenesis in precancerous lesions of

gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 13:160742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G and Tang D:

Broadening horizons: The role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 18:280–296. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhu W, Liu D, Lu Y, Sun J, Zhu J, Xing Y,

Ma X, Wang Y, Ji M and Jia Y: PHKG2 regulates RSL3-induced

ferroptosis in Helicobacter pylori related gastric cancer. Arch

Biochem Biophys. 740:1095602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Dierge E, Debock E, Guilbaud C, Corbet C,

Mignolet E, Mignard L, Bastien E, Dessy C, Larondelle Y and Feron

O: Peroxidation of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the

acidic tumor environment leads to ferroptosis-mediated anticancer

effects. Cell Metab. 33:1701–1715.e5. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Greenfield LK and Jones NL: Modulation of

autophagy by Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastric

carcinogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 21:602–612. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Genta RM: Helicobacter pylori,

inflammation, mucosal damage, and apoptosis: Pathogenesis and

definition of gastric atrophy. Gastroenterology. 113(6 Suppl):

S51–S55. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhu P, Xue J, Zhang ZJ, Jia YP, Tong YN,

Han D, Li Q, Xiang Y, Mao XH and Tang B: Helicobacter pylori VacA

induces autophagic cell death in gastric epithelial cells via the

endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Cell Death Dis. 8:32072017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Teng Y, Liu X, Han B, Ma Q, Liu Y, Kong H,

Lv Y, Mao F, Cheng P, Hao C, et al: Helicobacter

pylori-downregulated tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated

protein 1 mediates apoptosis of human gastric epithelial cells. J

Cell Physiol. 234:15698–15707. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Romero-Gallo J,

Barry DP, Hoge S, de Sablet T, Delgado AG, Wroblewski LE, Piazuelo

MB, Yan F, et al: Spermine oxidase mediates the gastric cancer risk

associated with Helicobacter pylori CagA. Gastroenterology.

141:1696-1708.e1–e2. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Wu S, Chen Y, Chen Z, Wei F, Zhou Q, Li P

and Gu Q: Reactive oxygen species and gastric carcinogenesis: The

complex interaction between Helicobacter pylori and host.

Helicobacter. 28:e130242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Salvatori S, Marafini I, Laudisi F,

Monteleone G and Stolfi C: Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer:

Pathogenetic mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 24:28952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Srinivas US, Tan BWQ, Vellayappan BA and

Jeyasekharan AD: ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox

Biol. 25:1010842019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Teymournejad O, Mobarez AM, Hassan ZM and

Talebi Bezmin Abadi A: Binding of the Helicobacter pylori OipA

causes apoptosis of host cells via modulation of Bax/Bcl-2 levels.

Sci Rep. 7:80362017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Jain P, Luo ZQ and Blanke SR: Helicobacter

pylori vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) engages the mitochondrial

fission machinery to induce host cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 108:16032–16037. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Posselt G, Wiesauer M, Chichirau BE,

Engler D, Krisch LM, Gadermaier G, Briza P, Schneider S, Boccellato

F, Meyer TF, et al: Helicobacter pylori-controlled c-Abl

localization promotes cell migration and limits apoptosis. Cell

Commun Signal. 17:102019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lin Y, Liu K, Lu F, Zhai C and Cheng F:

Programmed cell death in Helicobacter pylori infection and related

gastric cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 14:14168192024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kumar S and Dhiman M: Inflammasome

activation and regulation during Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis.

Microb Pathog. 125:468–474. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Cui G, Yuan A and Li Z: Occurrences and

phenotypes of RIPK3-positive gastric cells in Helicobacter pylori

infected gastritis and atrophic lesions. Dig Liver Dis.

54:1342–1349. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Qiang L, Zhang Y, Lei Z, Lu Z, Tan S, Ge

P, Chai Q, Zhao M, Zhang X, Li B, et al: A mycobacterial effector

promotes ferroptosis-dependent pathogenicity and dissemination. Nat

Commun. 14:14302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Dar HH, Tyurina YY, Mikulska-Ruminska K,

Shrivastava I, Ting HC, Tyurin VA, Krieger J, St Croix CM, Watkins

S, Bayir E, et al: Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilizes host

polyunsaturated phosphatidylethanolamines to trigger

theft-ferroptosis in bronchial epithelium. J Clin Invest.

128:4639–4653. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Drake IM, Mapstone NP, Schorah CJ, White

KL, Chalmers DM, Dixon MF and Axon AT: Reactive oxygen species

activity and lipid peroxidation in Helicobacter pylori associated

gastritis: Relation to gastric mucosal ascorbic acid concentrations

and effect of H pylori eradication. Gut. 42:768–771. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Peng Y, Lei X, Yang Q, Zhang G, He S, Wang

M, Ling R, Zheng B, He J, Chen X, et al: Helicobacter pylori

CagA-mediated ether lipid biosynthesis promotes ferroptosis

susceptibility in gastric cancer. Exp Mol Med. 56:441–452. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Liu D, Peng J, Xie J and Xie Y:

Comprehensive analysis of the function of helicobacter-associated

ferroptosis gene YWHAE in gastric cancer through multi-omics

integration, molecular docking, and machine learning. Apoptosis.

29:439–456. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Melo J, Cavadas B, Pereira L, Figueiredo C

and Leite M: Transcriptomic remodeling of gastric cells by

Helicobacter pylori outer membrane vesicles. Helicobacter.

29:e130312024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Shen C, Liu H, Chen Y, Liu M, Wang Q and

Liu J and Liu J: Helicobacter pylori induces GBA1 demethylation to

inhibit ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Mol Cell Biochem.

480:1845–1863. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao

N, Sun B and Wang G: Ferroptosis: Past, present and future. Cell

Death Dis. 11:882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Gryzik M, Asperti M, Denardo A, Arosio P

and Poli M: NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy promotes ferroptosis

induced by erastin, but not by RSL3 in HeLa cells. Biochim Biophys

Acta Mol Cell Res. 1868:1189132021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Chen X, Yu C, Kang R, Kroemer G and Tang

D: Cellular degradation systems in ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ.

28:1135–1148. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Huang Y, Xu W and Zhou R: NLRP3

inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell Mol Immunol.

18:2114–2127. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Liu Y, Miao R, Xia J, Zhou Y, Yao J and

Shao S: Infection of Helicobacter pylori contributes to the

progression of gastric cancer through ferroptosis. Cell Death

Discov. 10:4852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Piscione M, Mazzone M, Di Marcantonio MC,

Muraro R and Mincione G: Eradication of helicobacter pylori and

gastric cancer: A controversial relationship. Front Microbiol.

12:6308522021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

White JR, Winter JA and Robinson K:

Differential inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori

infection: Etiology and clinical outcomes. J Inflamm Res.

8:137–147. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Shah SC, Piazuelo MB, Kuipers EJ and Li D:

AGA clinical practice update on the diagnosis and management of

atrophic gastritis: Expert review. Gastroenterology.

161:1325–1332.e7. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Guo Y, Jia X, Du P, Wang J, Du Y, Li B,

Xue Y, Jiang J, Cai Y and Yang Q: Mechanistic insights into the

ameliorative effects of Xianglianhuazhuo formula on chronic

atrophic gastritis through ferroptosis mediated by

YY1/miR-320a/TFRC signal pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 323:1176082024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Yang T, Lu M, Jiang W, Jin D, Sun M, Mao H

and Han H: Galangin alleviates gastric mucosal injury in rats with

chronic atrophic gastritis by reducing ferroptosis. Histol

Histopathol. January 24–2025.Epub ahead of print.

|

|

83

|

Pan W, Liu C, Ren T, Chen X, Liang C, Wang

J and Yang J: Exploration of lncRNA/circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network in

patients with chronic atrophic gastritis in Tibetan plateau areas

based on DNBSEQ-G99 RNA sequencing. Sci Rep. 14:92122024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zhao Y, Zhao J, Ma H, Han Y, Xu W, Wang J,

Cai Y, Jia X, Jia Q and Yang Q: High hepcidin levels promote

abnormal iron metabolism and ferroptosis in chronic atrophic

gastritis. Biomedicines. 11:23382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lanser L, Fuchs D, Kurz K and Weiss G:

Physiology and inflammation driven pathophysiology of iron

homeostasis-mechanistic insights into anemia of inflammation and

its treatment. Nutrients. 13:37322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Schwarz P, Kübler JA, Strnad P, Müller K,

Barth TF, Gerloff A, Feick P, Peyssonnaux C, Vaulont S, Adler G and

Kulaksiz H: Hepcidin is localised in gastric parietal cells,

regulates acid secretion and is induced by Helicobacter pylori

infection. Gut. 61:193–201. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Ganz T and Nemeth E: Hepcidin and

disorders of iron metabolism. Annu Rev Med. 62:347–360. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Santos MP, Pereira JN, Delabio RW, Smith

MAC, Payão SLM, Carneiro LC, Barbosa MS and Rasmussen LT: Increased

expression of interleukin-6 gene in gastritis and gastric cancer.

Braz J Med Biol Res. 54:e106872021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Jia J, Zhao H, Li F, Zheng Q, Wang G, Li D

and Liu Y: Research on drug treatment and the novel signaling

pathway of chronic atrophic gastritis. Biomed Pharmacother.

176:1169122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhu F, Zhang X, Li P and Zhu Y: Effect of

Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric precancerous lesions: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 28:e130132023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Liang Y, Yang Y, Nong R, Huang H, Chen X,

Deng Y, Huang Z, Huang J, Cheng C, Ji M, et al: Do atrophic

gastritis and intestinal metaplasia reverse after Helicobacter

pylori eradication? Helicobacter. 29:e130422024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Bir F, Calli-Demirkan N, Tufan AC, Akbulut

M and Satiroglu-Tufan NL: Apoptotic cell death and its relationship

to gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 13:3183–3188.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Li T, Yang Q, Liu Y, Jin Y, Song B, Sun Q,

Wei S, Wu J and Li X: Machine learning identify ferroptosis-related

genes as potential diagnostic biomarkers for gastric intestinal

metaplasia. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 23:153303382412720362024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Song B, Li T, Zhang Y, Yang Q, Pei B, Liu

Y, Wang J, Dong G, Sun Q, Fan S and Li X: Identification and

verification of ferroptosis-related genes in gastric intestinal

metaplasia. Front Genet. 14:11524142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Hamedi Asl D, Naserpour Farivar T, Rahmani

B, Hajmanoochehri F, Emami Razavi AN, Jahanbin B, Soleimani Dodaran

M and Peymani A: The role of transferrin receptor in the

Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis; L-ferritin as a novel marker for

intestinal metaplasia. Microb Pathog. 126:157–164. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Xie J, Liang X, Xie F, Huang C, Lin Z, Xie

S, Yang F, Zheng F, Geng L, Xu W, et al: Rabeprazole suppressed

gastric intestinal metaplasia through activation of GPX4-mediated

ferroptosis. Front Pharmacol. 15:14090012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Ebrahimi N, Adelian S, Shakerian S,

Afshinpour M, Chaleshtori SR, Rostami N, Rezaei-Tazangi F,

Beiranvand S, Hamblin MR and Aref AR: Crosstalk between ferroptosis

and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition: Implications for

inflammation and cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.

64:33–45. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Zhang M, Zhong J, Song Z, Xu Q, Chen Y and

Zhang Z: Regulatory mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets in

precancerous lesions of gastric cancer: A comprehensive review.

Biomed Pharmacother. 177:1170682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Gu L, Chen H, Geng R, Sun M, Shi Q, Chen

Y, Chang J, Wei J, Ma W, Xiao J, et al: Single-cell and Spatial

transcriptomics reveals ferroptosis as the most enriched programmed

cell death process in hemorrhage stroke-induced

oligodendrocyte-mediated white matter injury. Int J Biol Sci.

20:3842–3862. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Miao ZF, Sun JX, Adkins-Threats M, Pang

MJ, Zhao JH, Wang X, Tang KW, Wang ZN and Mills JC: DDIT4 licenses

only healthy cells to proliferate during injury-induced metaplasia.

Gastroenterology. 160:260–271.e10. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Pang MJ, Burclaff JR, Jin R,

Adkins-Threats M, Osaki LH, Han Y, Mills JC, Miao ZF and Wang ZN:

Gastric organoids: Progress and remaining challenges. Cell Mol

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 13:19–33. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Hu X, Ma Z, Xu B, Li S, Yao Z, Liang B,

Wang J, Liao W, Lin L, Wang C, et al: Glutamine metabolic

microenvironment drives M2 macrophage polarization to mediate

trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer

Commun (Lond). 43:909–937. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Yang F, Li A, Liu H and Zhang H: Gastric

cancer combination therapy: Synthesis of a hyaluronic acid and

cisplatin containing lipid prodrug coloaded with sorafenib in a

nanoparticulate system to exhibit enhanced anticancer efficacy and

reduced toxicity. Drug Des Devel Ther. 12:3321–3333. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Qi C, Gong J, Li J, Liu D, Qin Y, Ge S,

Zhang M, Peng Z, Zhou J, Cao Y, et al: Claudin18.2-specific CAR T

cells in gastrointestinal cancers: Phase 1 trial interim results.

Nat Med. 28:1189–1198. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Yasuda T and Wang YA: Gastric cancer

immunosuppressive microenvironment heterogeneity: Implications for

therapy development. Trends Cancer. 10:627–642. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Gorrini C, Harris IS and Mak TW:

Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev

Drug Discov. 12:931–947. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Fonseca-Nunes A, Agudo A, Aranda N, Arija

V, Cross AJ, Molina E, Sanchez MJ, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Siersema

P, Weiderpass E, et al: Body iron status and gastric cancer risk in

the EURGAST study. Int J Cancer. 137:2904–2914. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Noto JM, Piazuelo MB, Shah SC,

Romero-Gallo J, Hart JL, Di C, Carmichael JD, Delgado AG, Halvorson

AE, Greevy RA, et al: Iron deficiency linked to altered bile acid

metabolism promotes Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation-driven

gastric carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 132:e1478222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Dai ZT, Wu YL, Li XR and Liao XH: MKL-1

suppresses ferroptosis by activating system Xc- and increasing

glutathione synthesis. Int J Biol Sci. 19:4457–4475. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Lu SC: Regulation of glutathione

synthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 30:42–59. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

111

|

Guan D and Li C, Li Y, Li Y, Wang G, Gao F

and Li C: The DpdtbA induced EMT inhibition in gastric cancer cell

lines was through ferritinophagy-mediated activation of p53 and

PHD2/hif-1α pathway. J Inorg Biochem. 218:1114132021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Guan D, Zhou W, Wei H, Wang T, Zheng K,

Yang C, Feng R, Xu R, Fu Y, Li C, et al: Ferritinophagy-mediated

ferroptosis and activation of Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway were

conducive to EMT inhibition of gastric cancer cells in action of

2,2'-Di-pyridineketone hydrazone dithiocarbamate butyric acid

ester. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:39206642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Xu Z, Feng J, Li Y, Guan D, Chen H, Zhai

X, Zhang L and Li C and Li C: The vicious cycle between

ferritinophagy and ROS production triggered EMT inhibition of

gastric cancer cells was through p53/AKT/mTor pathway. Chem Biol

Interact. 328:1091962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Li D, Wang Y, Dong C, Chen T, Dong A, Ren

J, Li W, Shu G, Yang J, Shen W, et al: CST1 inhibits ferroptosis

and promotes gastric cancer metastasis by regulating GPX4 protein

stability via OTUB1. Oncogene. 42:83–98. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

115

|

Lee JY, Nam M, Son HY, Hyun K, Jang SY,

Kim JW, Kim MW, Jung Y, Jang E, Yoon SJ, et al: Polyunsaturated

fatty acid biosynthesis pathway determines ferroptosis sensitivity

in gastric cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:32433–32442. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Lin Z, Song J, Gao Y, Huang S, Dou R,

Zhong P, Huang G, Han L, Zheng J, Zhang X, et al: Hypoxia-induced

HIF-1α/lncRNA-PMAN inhibits ferroptosis by promoting the

cytoplasmic translocation of ELAVL1 in peritoneal dissemination

from gastric cancer. Redox Biol. 52:1023122022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Liu Y, Song Z, Liu Y, Ma X, Wang W, Ke Y,

Xu Y, Yu D and Liu H: Identification of ferroptosis as a novel

mechanism for antitumor activity of natural product derivative a2

in gastric cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:1513–1525. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Hu C, Zu D, Xu J, Xu H, Yuan L, Chen J,

Wei Q, Zhang Y, Han J, Lu T, et al: Polyphyllin B suppresses

gastric tumor growth by modulating iron metabolism and inducing

ferroptosis. Int J Biol Sci. 19:1063–1079. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Ding L, Dang S, Sun M, Zhou D, Sun Y, Li

E, Peng S, Li J and Li G: Quercetin induces ferroptosis in gastric

cancer cells by targeting SLC1A5 and regulating the p-Camk2/p-DRP1

and NRF2/GPX4 Axes. Free Radic Biol Med. 213:150–163. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Wang H, Lu C, Zhou H, Zhao X, Huang C,

Cheng Z, Liu G and You X: Synergistic effects of dihydroartemisinin

and cisplatin on inducing ferroptosis in gastric cancer through

GPX4 inhibition. Gastric Cancer. 28:187–210. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|

Ouyang S, Li H, Lou L, Huang Q, Zhang Z,

Mo J, Li M, Lu J, Zhu K, Chu Y, et al: Inhibition of

STAT3-ferroptosis negative regulatory axis suppresses tumor growth

and alleviates chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Redox Biol.

52:1023172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Ni Z, Nie X, Zhang H, Wang L, Geng Z, Du

X, Qian H, Liu W and Liu T: Atranorin driven by nano materials

SPION lead to ferroptosis of gastric cancer stem cells by weakening

the mRNA 5-hydroxymethylcytidine modification of the Xc-/GPX4 axis

and its expression. Int J Med Sci. 19:1680–1694. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Cui JX, Xu XH, He T, Liu JJ, Xie TY, Tian

W and Liu JY: L-kynurenine induces NK cell loss in gastric cancer

microenvironment via promoting ferroptosis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

42:522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Kumar V, Ramnarayanan K, Sundar R,

Padmanabhan N, Srivastava S, Koiwa M, Yasuda T, Koh V, Huang KK,

Tay ST, et al: Single-cell atlas of lineage states, tumor

microenvironment, and subtype-specific expression programs in

gastric cancer. Cancer Discov. 12:670–691. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Zhang Q, Kuang G, Li W, Wang J, Ren H and

Zhao Y: Stimuli-responsive gene delivery nanocarriers for cancer

therapy. Nanomicro Lett. 15:442023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Cheng X, Dai E, Wu J, Flores NM, Chu Y,

Wang R, Dang M, Xu Z, Han G, Liu Y, et al: Atlas of metastatic

gastric cancer links ferroptosis to disease progression and

immunotherapy response. Gastroenterology. 167:1345–1357. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Tamura K, Tomita Y, Kanazawa T, Shinohara

H, Sakano M, Ishibashi S, Ikeda M, Kinoshita M, Minami J, Yamamoto

K, et al: Lipid peroxidation regulators GPX4 and FSP1 as prognostic

markers and therapeutic targets in advanced gastric cancer. Int J

Mol Sci. 25:92032024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Lin L, Que R, Wang J, Zhu Y, Liu X and Xu

R: Prognostic value of the ferroptosis-related gene SLC2A3 in

gastric cancer and related immune mechanisms. Front Genet.

13:9193132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Liu Y, Liu Y, Ye S, Feng H and Ma L: A new

ferroptosis-related signature model including messenger RNAs and

long non-coding RNAs predicts the prognosis of gastric cancer

patients. J Transl Int Med. 11:145–155. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Cai Y, Wu S, Jia Y, Pan X and Li C:

Potential key markers for predicting the prognosis of gastric

adenocarcinoma based on the expression of ferroptosis-related

lncRNA. J Immunol Res. 2022:12492902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Ryu MH, Lee KH, Shen L, Yeh KH, Yoo C,

Hong YS, Park YI, Yang SH, Shin DB, Zang DY, et al: Randomized

phase II study of capecitabine plus cisplatin with or without

sorafenib in patients with metastatic gastric cancer (STARGATE).

Cancer Med. 12:7784–7794. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

132

|

Xu X and Li Y, Wu Y, Wang M, Lu Y, Fang Z,

Wang H and Li Y: Increased ATF2 expression predicts poor prognosis

and inhibits sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Redox

Biol. 59:1025642023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

133

|

Zhuang J, Liu X, Yang Y, Zhang Y and Guan

G: Sulfasalazine, a potent suppressor of gastric cancer

proliferation and metastasis by inhibition of xCT: Conventional

drug in new use. J Cell Mol Med. 25:5372–5380. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Shitara K, Doi T, Nagano O, Fukutani M,

Hasegawa H, Nomura S, Sato A, Kuwata T, Asai K, Einaga Y, et al:

Phase 1 study of sulfasalazine and cisplatin for patients with

CD44v-positive gastric cancer refractory to cisplatin (EPOC1407).

Gastric Cancer. 20:1004–1009. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Wang Y, Zheng L, Shang W, Yang Z, Li T,

Liu F, Shao W, Lv L, Chai L, Qu L, et al: Wnt/beta-catenin

signaling confers ferroptosis resistance by targeting GPX4 in

gastric cancer. Cell Death Differ. 29:2190–2202. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Wu C, Wang S, Huang T, Xi X, Xu L, Wang J,

Hou Y, Xia Y, Xu L, Wang L and Huang X: NPR1 promotes cisplatin

resistance by inhibiting PARL-mediated mitophagy-dependent

ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Cell Biol Toxicol. 40:932024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Fu D, Wang C, Yu L and Yu R: Induction of

ferroptosis by ATF3 elevation alleviates cisplatin resistance in

gastric cancer by restraining Nrf2/Keap1/xCT signaling. Cell Mol

Biol Lett. 26:262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Zhou Q, Liu T, Qian W, Ji J, Cai Q, Jin Y,

Jiang J and Zhang J: HNF4A-BAP31-VDAC1 axis synchronously regulates

cell proliferation and ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Cell Death

Dis. 14:3562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Qu X, Liu B, Wang L, Liu L, Zhao W, Liu C,

Ding J, Zhao S, Xu B, Yu H, et al: Loss of cancer-associated

fibroblast-derived exosomal DACT3-AS1 promotes malignant

transformation and ferroptosis-mediated oxaliplatin resistance in

gastric cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 68:1009362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Yao L, Hou J, Wu X, Lu Y, Jin Z, Yu Z, Yu

B, Li J, Yang Z, Li C, et al: Cancer-associated fibroblasts impair

the cytotoxic function of NK cells in gastric cancer by inducing

ferroptosis via iron regulation. Redox Biol. 67:1029232023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Sun J, Li J, Pantopoulos K, Liu Y, He Y,

Kang W and Ye X: The clustering status of detached gastric cancer

cells inhibits anoikis-induced ferroptosis to promote metastatic

colonization. Cancer Cell Int. 24:772024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Yao X, He Z, Qin C, Deng X, Bai L, Li G

and Shi J: SLC2A3 promotes macrophage infiltration by glycolysis

reprogramming in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 20:5032020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Li Y, Xu X, Wang X, Zhang C, Hu A and Li

Y: MGST1 expression is associated with poor prognosis, enhancing

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway via regulating AKT and inhibiting

ferroptosis in gastric cancer. ACS Omega. 8:23683–23694. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Wang C, Shi M, Ji J, Cai Q, Zhao Q, Jiang

J, Liu J, Zhang H, Zhu Z and Zhang J: Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1

(SCD1) facilitates the growth and anti-ferroptosis of gastric

cancer cells and predicts poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Aging

(Albany NY). 12:15374–15391. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Sun X, Yang S, Feng X, Zheng Y, Zhou J,

Wang H, Zhang Y, Sun H and He C: The modification of ferroptosis

and abnormal lipometabolism through overexpression and knockdown of

potential prognostic biomarker perilipin2 in gastric carcinoma.

Gastric Cancer. 23:241–259. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

146

|

Zang J, Cui M, Xiao L, Zhang J and Jing R:

Overexpression of ferroptosis-related genes FSP1 and CISD1 is

related to prognosis and tumor immune infiltration in gastric

cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 25:2532–2544. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Li X, Qian J, Xu J, Bai H, Yang J and Chen

L: NRF2 inhibits RSL3 induced ferroptosis in gastric cancer through

regulation of AKR1B1. Exp Cell Res. 442:1142102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Tu RH, Wu SZ, Huang ZN, Zhong Q, Ye YH,

Zheng CH, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Chen QY, et al: Neurotransmitter

receptor HTR2B regulates lipid metabolism to inhibit ferroptosis in

gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 83:3868–3885. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|