Introduction

Lung cancer accounts for 18% of global cancer

deaths, with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprising 85% of

cases (1). Despite advances in

targeted agents and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), the 5-year

survival rate remains at ≤25% (2). Notably, primary or acquired

resistance occurs in 50-60% of patients with EGFR mutations within

12-18 months (3) and in ≥30% of

patients treated with ICB (4).

Intratumoral heterogeneity and clonal evolution are recognized

drivers of resistance; however, the tumor microenvironment (TME) is

increasingly appreciated as an active factor that imposes

metabolic, physical and immunological barriers to therapy (5).

The heterogeneity of NSCLC further complicates

treatment. Genomic analyses have revealed distinct molecular

subtypes of NSCLC, such as KRAS, BRAF and RET, each requiring

tailored therapies (6). However,

even within the same subtype, intratumoral heterogeneity drives

clonal evolution and therapeutic escape (5). For example, KRAS G12C inhibitors,

such as sotorasib, achieve objective response rates (ORRs) of 37%;

however, resistance emerges through alternative pathway activation

or phenotypic switching (7).

Immunotherapy resistance is equally complex, with TME-mediated

mechanisms such as T-cell exhaustion, myeloid-derived suppressor

cells (MDSCs) and collagen-rich physical barriers impeding immune

cell infiltration (8).

The TME has emerged as a critical factor in cancer

progression and therapeutic resistance, as supported by both

preclinical models and clinical trial data (9-14).

Comprising tumor cells, immune cells, stromal components,

extracellular matrix (ECM) and bioactive molecules, the TME is a

dynamic ecosystem that actively promotes tumor evolution, immune

evasion and therapeutic resistance (10). Chronic inflammation within the

TME, for example, has been linked to the development of an

immunosuppressive environment, which facilitates tumor progression

and resistance to immunotherapy (11). Studies have shown that components

of the TME, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), MDSCs and

regulatory T cells (Tregs), serve key roles in suppressing

antitumor immune responses (12,13). Additionally, the ECM and its

degradative enzymes contribute to tumor invasion and metastasis by

remodeling the physical structure of the TME (14). Understanding these interactions is

crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies that target the

TME to overcome resistance and improve patient outcomes.

The present review aims to provide a comprehensive

analysis of the role of the TME in lung cancer progression and

therapeutic resistance. Firstly, the molecular mechanisms

underlying TME-mediated immune evasion and resistance to

chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy were explored.

Furthermore, emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the TME,

such as immunotherapy combinations, anti-angiogenic therapies and

nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems, were critically

evaluated, and their potential to overcome resistance and enhance

treatment efficacy discussed. The current review will highlight the

importance of integrating TME profiling into personalized medicine

approaches, and emphasize the need for further research to address

the challenges posed by TME heterogeneity and plasticity. By

bridging gaps in the current knowledge, the review seeks to inform

future research directions and clinical applications in the

management of lung cancer.

Heterogeneity of the lung cancer

microenvironment

The heterogeneity of the lung cancer

microenvironment arises from the complex interplay of cellular and

non-cellular components, as well as emerging factors such as

microbiota and neuronal crosstalk (15,16). This heterogeneity poses notable

challenges for therapeutic intervention, necessitating a deeper

understanding of the dynamic interactions within the TME to develop

effective treatment strategies.

Cellular components

The TME in lung cancer is characterized by a complex

array of immune cells, including TAMs, MDSCs and Tregs, which

collectively contribute to an immunosuppressive environment

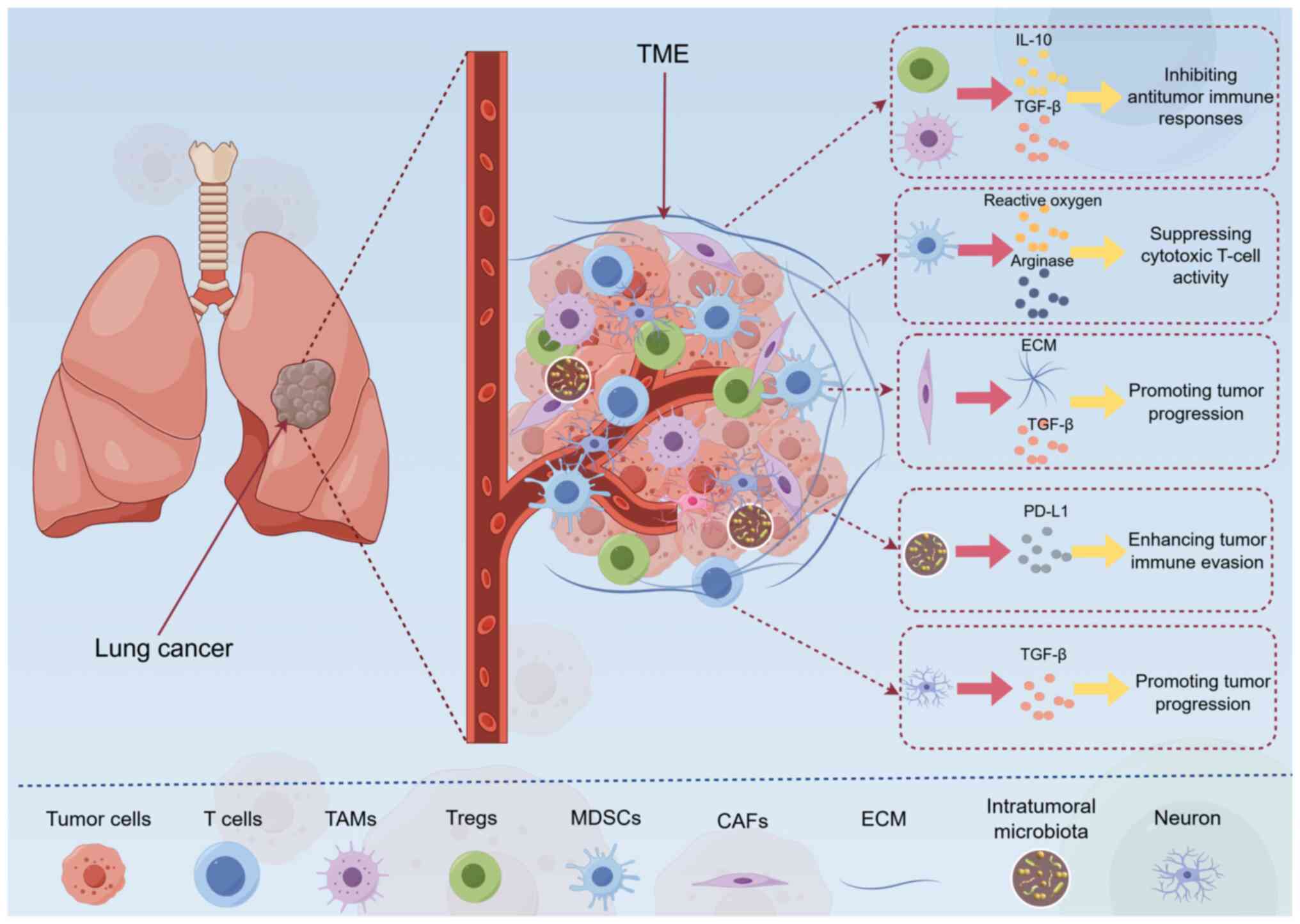

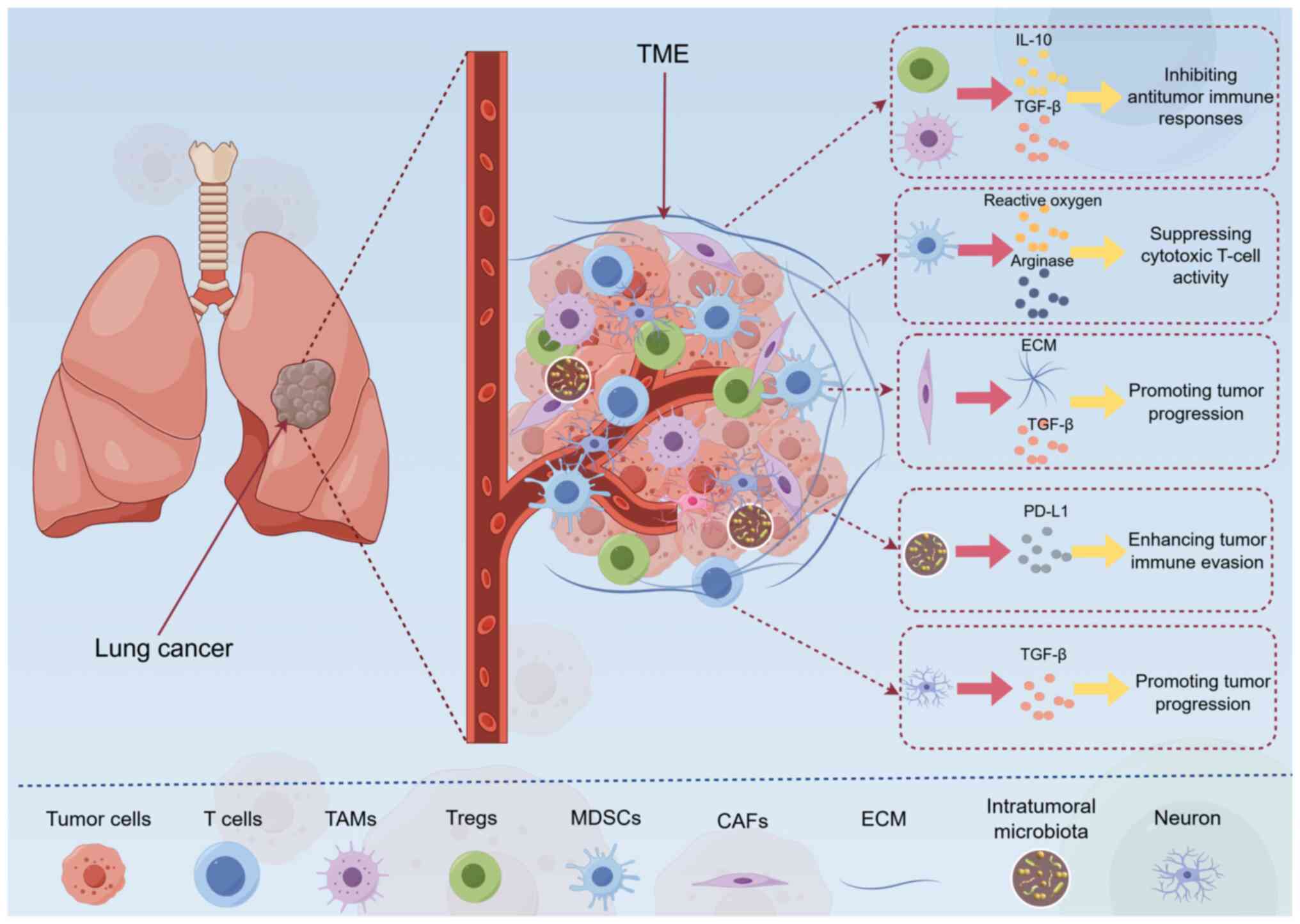

(5) (Fig. 1). TAMs, particularly the

M2-polarized subset, secrete interleukin (IL)-10 and transforming

growth factor-β (TGF-β) to inhibit antitumor immunity and support

tumor progression (5). Similarly,

MDSCs impair cytotoxic T-cell function via reactive oxygen species

and arginase production (17),

and Tregs further reinforce immunosuppression through secretion of

immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β (18). However, studies have highlighted

the heterogeneity of these immune cells within the TME (19,20). For example, it has been suggested

that TAMs can exhibit both protumorigenic and antitumorigenic

functions depending on their spatial distribution and functional

orientation within the tumor (21,22). This heterogeneity complicates

therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs, as interventions may need to

account for their dual roles (23).

| Figure 1TME composition and interactions in

lung cancer. Components of the TME, including immune cells (such as

TAMs, MDSCs and Tregs), stromal cells (for example, CAFs and

endothelial cells), ECM and soluble factors (cytokines, chemokines

and growth factors), are shown, as are the interaction between

these components. For example, TAMs secrete IL-10 and TGF-β, thus

inhibiting antitumor immune responses, and CAFs promote tumor

progression by secreting ECM components and growth factors. This

figure was created using Figdraw (www.figdraw.com, ID: YTYOW4a999). CAFs,

cancer-associated fibroblasts; ECM, extracellular matrix; IL-10,

interleukin-10; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; PD-L1,

programmed death-ligand 1; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; TME,

tumor microenvironment; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; Tregs,

regulatory T cells. |

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) contribute to

tumor progression and therapeutic resistance by remodeling the ECM

and secreting growth factors such as TGF-β and fibroblast growth

factor (FGF) (24) (Fig. 1). Through ECM deposition and

cross-linking, CAFs create a physical barrier that impedes drug

penetration and immune cell infiltration, while also promoting

angiogenesis and metastatic dissemination (25,26). Additionally, the presence of other

immune cell subsets, such as natural killer (NK) cells and γδ T

cells, has been shown to influence tumor outcomes. NK cells, known

for their ability to recognize and lyse tumor cells without prior

sensitization, can be impaired in the TME due to factors such as

TGF-β and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression (27). γδ T cells, which are involved in

both innate and adaptive immunity, have also been shown to serve a

role in shaping the TME and affecting therapeutic responses

(28).

Non-cellular components

The ECM undergoes dynamic remodeling in the TME,

driven by matrix stiffness, collagen crosslinking and protease

activity (29). Matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other proteases degrade the ECM,

facilitating tumor invasion and metastasis (30). Additionally, increased matrix

stiffness can enhance tumor cell proliferation and resistance to

therapy by promoting mechanotransduction pathways (30). These changes in the ECM create a

physical barrier that limits drug delivery and contributes to

therapeutic resistance.

Soluble factors, such as cytokines (for example,

IL-6 and TNF-α), chemokines and growth factors, are critical

drivers of TME heterogeneity. IL-6, for example, promotes tumor

progression by activating the STAT3 pathway, which enhances cell

survival and proliferation (31).

TNF-α, while often associated with inflammation, can also

contribute to immunosuppression by upregulating PD-L1 expression on

tumor cells (31). Growth factors

such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drive

angiogenesis and create an immunosuppressive microenvironment,

further complicating therapeutic strategies (32).

Emerging factors

Recent studies have identified the presence of

intratumoral microbiota within the lung cancer microenvironment,

with microbial metabolites influencing oncogenic signaling and

immune evasion (33,34). For example, certain bacterial

species have been shown to modulate the expression of immune

checkpoint molecules, such as PD-L1, thereby enhancing tumor immune

evasion (35) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the role of the

gut-lung axis in shaping the lung TME has garnered attention. The

gut microbiota can influence systemic immunity and inflammation,

which in turn affects the composition and function of the lung

microbiota and TME (36). This

interplay between the gut and lung may offer novel targets for

therapeutic intervention.

Neuronal interactions within the TME have also

emerged as a novel area of research (37). Neurotrophic factors and

axonogenesis promote tumor innervation, which can enhance tumor

growth and metastasis (38).

Studies have suggested that neural signaling may influence the

secretion of protumorigenic factors, such as TGF-β, and create a

permissive environment for tumor progression (39,40) (Fig.

1). Additionally, the involvement of neuronal-derived exosomes

in transmitting signals that promote tumor cell survival and

therapeutic resistance has been revealed (41), highlighting the importance of

understanding the bidirectional communication between neurons and

tumor cells in shaping the TME.

The heterogeneity of the lung cancer

microenvironment, driven by diverse cellular interactions and

dynamic non-cellular components, presents a notable barrier to

effective therapy. Understanding these complex interactions is

essential for developing targeted approaches that can modulate the

TME to enhance treatment efficacy. By addressing the dual roles of

immune cells, the fibrotic networks created by CAFs and the

physical barriers of the ECM, future therapeutic strategies may be

better designed to overcome resistance and improve patient

outcomes.

Dynamic crosstalk in the TME: Mechanisms of

progression

The intricate crosstalk within the TME facilitates

immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modulation,

thereby creating a permissive niche for tumor growth and

therapeutic resistance (12,42). Understanding these dynamic

interactions is crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies

that target the TME to enhance treatment efficacy and overcome

resistance in lung cancer.

Immune evasion and checkpoint

dysregulation

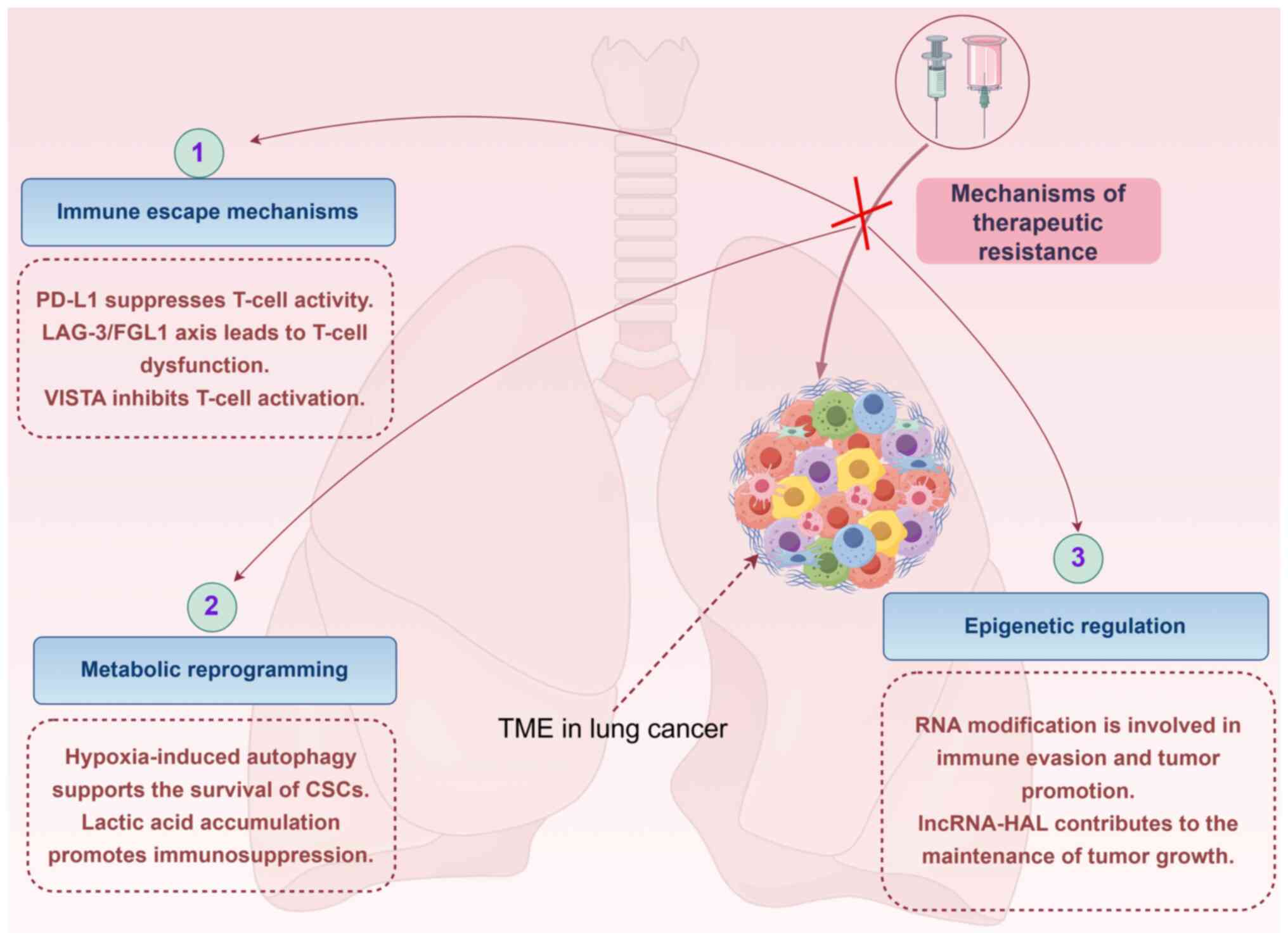

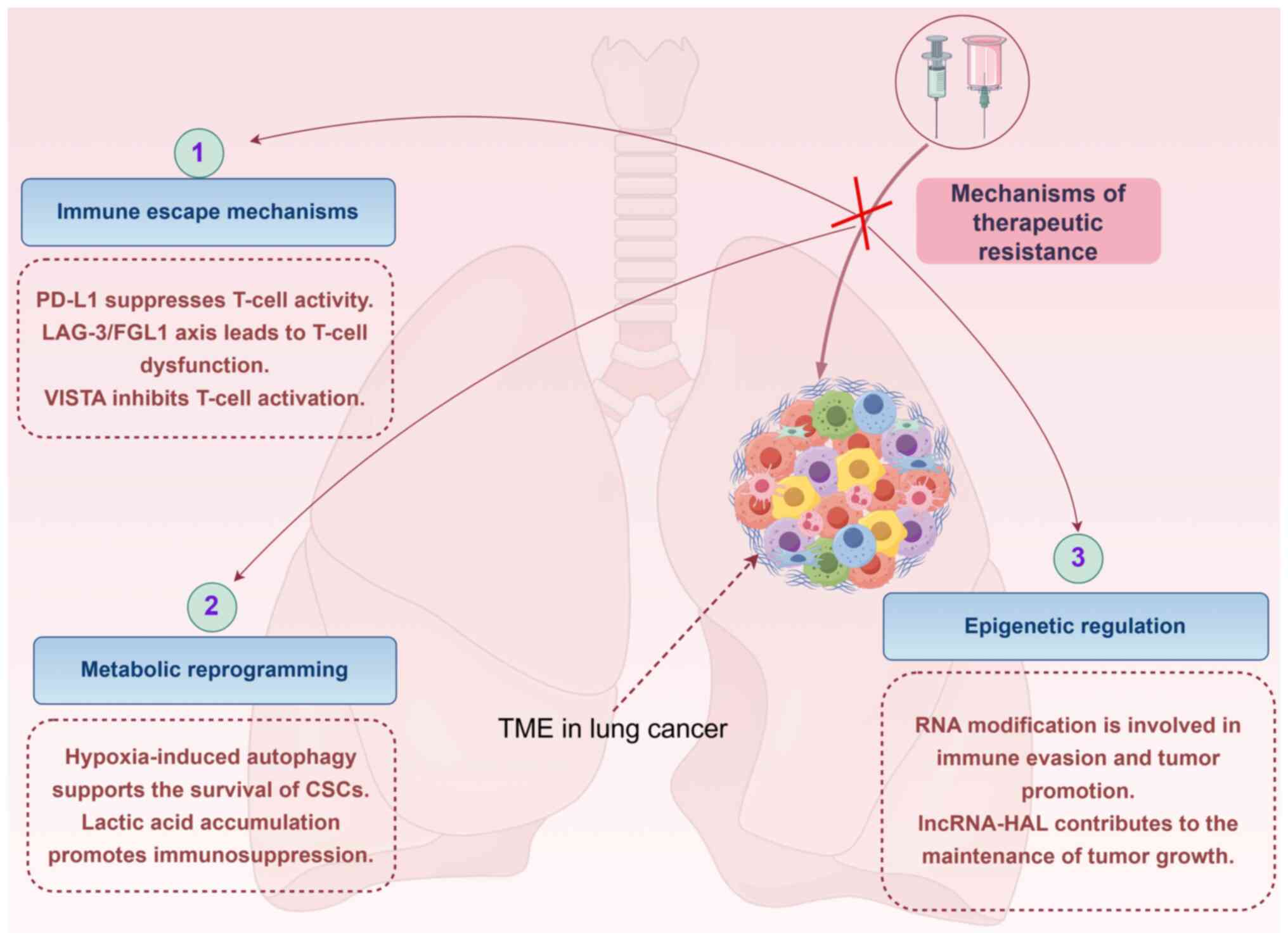

The TME facilitates immune evasion through various

mechanisms, including the upregulation of immune checkpoint

molecules and the polarization of immune cells (11). PD-L1, a well-known immune

checkpoint protein, is often upregulated in lung cancer cells,

enabling them to suppress T-cell activity and evade immune

detection (43,44) (Fig.

2). Previous studies have also highlighted the role of the

lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3)/fibrinogen-like protein 1

(FGL1) axis and V-type immunoglobulin domain-containing suppressor

of T-cell activation (VISTA) in immune evasion. LAG-3, expressed on

exhausted T cells, interacts with FGL1, leading to T-cell

dysfunction (45). VISTA, another

immune checkpoint molecule, contributes to the immunosuppressive

environment by inhibiting T-cell activation (46). TAMs serve a notable role in immune

evasion by polarizing toward an M2 phenotype. This polarization is

driven by cytokines such as colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1),

which activates CSF-1 receptor signaling in macrophages (47). However, the extent to which these

mechanisms contribute to immune evasion may vary among different

lung cancer subtypes and patient populations, necessitating further

investigation to clarify their roles and potential therapeutic

targets.

| Figure 2Mechanisms of therapeutic resistance

in the TME. The mechanism by which the TME drives treatment

resistance is shown, including immune escape mechanisms (such as

PD-L1 upregulation, the LAG-3/FGL1 axis and the role of VISTA),

metabolic reprogramming (for example, hypoxia-induced autophagy and

immunosuppression due to lactic acid accumulation) and epigenetic

regulation (such as RNA modification and the role of lncRNAs). This

figure was created using Figdraw (www.figdraw.com, ID: STSWAa4006). CSCs, cancer stem

cells; FGL1, fibrinogen-like protein 1; LAG-3,

lymphocyte-activation gene 3; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; PD-L1,

programmed death-ligand 1; TME, tumor microenvironment; VISTA,

V-type immunoglobulin domain-containing suppressor of T-cell

activation. |

Metabolic reprogramming and hypoxia

Hypoxia is a common feature of the TME, and has

marked effects on tumor progression and therapeutic resistance

(48) (Fig. 2). Hypoxia-induced autophagy,

mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and BCL-2/adenovirus E1B 19

kDa protein-interacting protein 3, supports the survival of cancer

stem cells (CSCs). CSCs are known for their ability to self-renew

and differentiate, contributing to tumor heterogeneity and

resistance to therapy (49). By

maintaining CSC survival, hypoxia-induced autophagy ensures a

reservoir of cells capable of repopulating the tumor after

treatment.

Lactate, a byproduct of anaerobic metabolism,

accumulates in the TME under hypoxic conditions and serves a role

in promoting immunosuppression (50) (Fig.

2). Lactate-mediated signaling in stromal cells, such as

Notch/C-C motif chemokine ligand 5, fosters an immunosuppressive

environment by attracting Tregs and inhibiting the function of

cytotoxic T cells (51). This

metabolic reprogramming not only supports tumor growth but also

creates a barrier to effective immune responses, highlighting the

complex interplay between metabolic changes and immune modulation

in the TME.

Epigenetic modulation in the TME

Epigenetic changes within the TME markedly influence

tumor progression and therapeutic resistance (42) (Fig.

2). RNA modifications, including m6A, m5C and ac4C, have

emerged as critical regulators of mRNA stability and translation.

These modifications can affect the expression of immune-related

genes, such as PD-L1, STAT1 and IRF7, thereby

modulating immune cell function and the overall immune response

within the TME (52). For

example, m6A methylation of specific mRNA transcripts can enhance

their stability and translation efficiency, leading to increased

production of proteins involved in immune evasion and tumor

promotion (53).

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) also serve a role in

shaping the TME through epigenetic mechanisms (54). Hypoxia-induced lncRNA-HAL has been

shown to promote stemness and therapeutic resistance by interacting

with chromatin remodeling complexes (55). By altering the epigenetic

landscape, lncRNA-HAL contributes to the maintenance of a favorable

environment for tumor growth and resistance to treatment (56). Understanding the specific roles of

these epigenetic modulators and their interactions within the TME

is crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at

reversing epigenetic changes and enhancing treatment efficacy in

lung cancer.

The intricate crosstalk within the TME, involving

immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modulation,

creates a complex landscape of resistance mechanisms in lung

cancer. By targeting key nodes in these networks, such as immune

checkpoint regulation, hypoxia-driven pathways and epigenetic

modifiers, novel therapies can be developed to disrupt the

supportive role of the TME in tumor progression. These approaches

hold promise for enhancing the effectiveness of existing treatments

and addressing the challenge of therapeutic resistance.

Resistance to targeted therapy

Resistance to targeted therapies, such as

EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), is a notable challenge in

lung cancer treatment. One of the key mechanisms underlying this

resistance is the activation of alternative signaling pathways.

TAMs contribute to resistance against targeted therapies such as

EGFR-TKIs by secreting hepatocyte growth factor, which activates

the c-MET pathway and bypasses EGFR inhibition (57). Moreover, TAMs and CAFs

collaboratively foster a fibrotic niche via ECM remodeling, which

physically restricts drug access and activates alternative survival

pathways (58,59).

Genetic alterations, including secondary EGFR

mutations (such as T790M) and MET amplification, remain key drivers

of acquired resistance (60).

These changes are often facilitated by a pro-inflammatory TME,

which promotes genomic instability and enriches for resistant

clones (61).

Resistance to ICB

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have

revolutionized the treatment landscape for lung cancer, but

resistance to these therapies remains a key issue. Resistance to

ICIs can be influenced by various factors within the TME (62). For example, the presence of

immunosuppressive cells, such as MDSCs and Tregs, can inhibit the

activation and function of cytotoxic T cells. These

immunosuppressive cells can be recruited and activated by cytokines

such as TGF-β and IL-10, which are often upregulated in the TME.

The dense infiltration of MDSCs and Tregs creates a suppressive

milieu that limits the efficacy of ICB (63).

Moreover, physical barriers within the TME, such as

a dense ECM and poor vascularization, can prevent immune cells from

infiltrating the tumor (64). A

recent study demonstrated that the ECM stiffness, mediated by

collagen crosslinking and MMPs, can physically impede T-cell

migration and reduce the delivery of ICIs to their targets. This

structural barrier is further exacerbated by the presence of

immunosuppressive cytokines, which collectively contribute to the

resistance of tumors to immunotherapy (64).

The interplay between targeted therapeutic

resistance and immune evasion is complex and can be influenced by

the TME. Metabolic changes induced by targeted therapies can alter

the TME and contribute to immune resistance (65). For example, hypoxia resulting from

tumor growth can lead to the upregulation of PD-L1 and the

recruitment of immunosuppressive cells. Additionally, the release

of damage-associated molecular patterns from dying cancer cells

during targeted therapy can activate innate immune responses that

paradoxically promote immunosuppression.

TME-driven therapeutic resistance in lung

cancer

Comprehending TME-mediated resistance mechanisms is

essential to devise new lung cancer therapies that restore drug

sensitivity and prolong patient survival. Future research should

focus on assessing the molecular and cellular interactions within

the TME and exploring combination therapies that target multiple

resistance pathways simultaneously.

Immune evasion and resistance

mechanisms

Previous studies have highlighted the role of immune

evasion mechanisms in therapeutic resistance (Table I). Utsumi et al (66) demonstrated that AXL-mediated drug

resistance in ALK-rearranged NSCLC was enhanced by growth-arrest

specific protein 6 from macrophages and MMP11-positive fibroblasts,

underscoring the importance of cellular interactions within the

TME. Moreover, Peyraud et al (67) utilized spatially resolved

transcriptomics to reveal determinants of primary resistance to

immunotherapy in NSCLC with mature tertiary lymphoid structures,

suggesting that the spatial organization of immune cells may impact

therapy outcomes. However, Nishinakamura et al (68) showed that coactivation of innate

immune suppressive cells induced acquired resistance against

combined Toll-like receptor 7/8 agonist treatment and programmed

cell death protein 1 (PD-1) blockade, further illustrating the

dynamic nature of immune resistance mechanisms. Notably, large

clinical trials, such as KEYNOTE-189, have validated the impact of

TME features on immunotherapy response, reinforcing the clinical

relevance of these mechanisms (69).

| Table IStudies on the TME driving drug

resistance in lung cancer. |

Table I

Studies on the TME driving drug

resistance in lung cancer.

| First author,

year | Treatment

measures | Study type | Model | Resistance

mechanisms | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Utsumi, 2025 | AXL inhibition +

GAS6/MMP11 blockade | Preclinical |

ALK-rearranged

NSCLC cell lines | Macrophage-derived

GAS6 and fibroblast MMP11 activated AXL to bypass ALK

inhibition | (66) |

| Peyraud, 2025 | Spatially resolved

transcriptomics | Clinical | NSCLC with tertiary

lymphoid structures | Spatial exclusion

of CD8+ T cells by stromal barriers and

immunosuppressive cytokine gradients | (67) |

| Nishinakamura,

2025 | Toll-like receptor

agonist + PD-1 blockade | Preclinical | Syngeneic murine

models | MDSC recruitment

via CCL2/CCR2 axis and Treg activation through TGF-β/IL-10

signaling | (68) |

| Ebid, 2025 | Cisplatin +

fibroblast crosstalk | In

vitro | NSCLC cell lines +

fibroblast co-culture | CAF-secreted IL-6

activated STAT3 to upregulate anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family

proteins | (78) |

| Zhang, 2024 | LDHA-targeted

inhibition | Pan-cancer

analysis | NSCLC clinical

datasets | Lactate-driven

acidosis induced PD-L1 upregu lation and impaired T-cell

cytotoxicity | (79) |

| Wang, 2024 | POSTN CAF/ACKR1 EC

interaction |

Single-cell

RNA-sequencing |

TKI-resistant

NSCLC xenografts | CAF-derived POSTN

activated endothelial ACKR1 to recruit immunosuppressive

neutrophils | (80) |

| Wang, 2024 | SMARCA4 mutation

analysis | Preclinical | NSCLC

organoids | Chromatin

remodeling defects reduced neoantigen presentation and

CD8+ T-cell infiltration | (81) |

| Huang, 2024 | EGFR-TKI + TGF-β

blockade | In vivo | EGFR-mutant PDX

models | ERK1/2-p90RSK axis

enhanced TGF-β secretion, promoting T-cell exhaustion and Treg

expansion | (82) |

| Kobayashi,

2024 | Bevacizumab +

miR-200c delivery | Organoid

models | EGFR-mutant NSCLC

organoids | EMT-mediated

VEGF-independent angiogenesis and ECM remodeling via ZEB1/MMP9

activation | (83) |

| Tan, 2024 | Lung-on-a-chip drug

screening | Multicellular

model |

EGFR-TKI-resistant

NSCLC | Fibroblast-mediated

paracrine HGF/c-MET signaling drove bypass survival pathways | (84) |

| Pan, 2024 | Disulfidptosis gene

targeting | Radiogenomics | Lung adenocarcinoma

cohorts | Cysteine metabolism

rewiring protected against radiation-induced ferroptosis | (85) |

| Han, 2024 | Osimertinib + anti

angiogenic therapy | Phase II trial |

Osimertinib-resistant

NSCLC | VEGFR2/PDGFRβ

crosstalk induced CAF activation and hyaluronan-rich ECM

deposition | (86) |

| Shen, 2023 | T1-mapping MRI

nanoprobe | Diagnostic

study | Patients with

multidrug-resistant

NSCLC | Hypoxia-induced

collagen crosslinking reduced drug permeability and enhanced efflux

pumps | (87) |

| Lu, 2023 | STAT3/CD47-SIRPα

axis inhibition | Preclinical |

EGFR-TKI-resistant

PDX models | TAM phagocytosis

evasion via CD47 upregulation and STAT3-driven immunosuppressive

niche | (88) |

The involvement of specific T-cell subsets in lung

cancer resistance mechanisms has garnered attention in previous

research. γδ T cells, which are part of the innate-like T-cell

population, have been shown to serve a dual role in the TME

(70). Some studies have

indicated that γδ T cells can mediate antitumor responses through

the secretion of IFN-γ and the killing of tumor cells (71,72). However, other research has

suggested that γδ T cells may also contribute to immunosuppression

by producing immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β,

in the TME, thereby promoting tumor progression and resistance to

therapy (73). For example, Liu

et al (28) demonstrated

that the frequency and function of γδ T cells were altered in

patients with lung cancer, and these cells may influence the

efficacy of immunotherapy. Additionally, tissue-resident memory T

cells (Trm) have been identified as key players in local immune

responses. Trm cells persist in tissues long-term and can provide

immediate protection against tumor recurrence (74). However, in the context of chronic

inflammation and an immunosuppressive TME, Trm cells may lose their

function or even promote tumor growth. It has been shown that the

expression of checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1 and LAG-3, on Trm

cells can limit their antitumor activity, contributing to

therapeutic resistance (75).

In addition to T-cell subsets, other immune cells

such as innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) have been implicated in

shaping the TME and influencing therapeutic outcomes. ILCs,

including ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s, can regulate tumor inflammation

and immune responses through the secretion of cytokines. For

example, ILC3s have been reported to promote tumor progression by

secreting IL-22, which can enhance tumor cell survival and

resistance to therapy (76).

Furthermore, the interaction between ILCs and other immune cells,

such as macrophages and dendritic cells, can modulate the overall

immune response in the TME, affecting the efficacy of immunotherapy

(77).

Fibroblast-induced resistance and

metabolic reprogramming

Additionally, paracrine signaling mechanisms between

tumor cells and CAFs can synergize with the TME to drive resistance

(Table I). Ebid et al

(78) investigated the cross-talk

signaling between NSCLC cell lines and fibroblasts, demonstrating

that this interaction can attenuate the cytotoxic effect of

cisplatin. This previous study highlighted the role of CAFs in

mediating chemoresistance. Additionally, Zhang et al

(79) identified lactate

dehydrogenase A as a novel predictor for immunotherapy resistance,

linking metabolic reprogramming within the TME to therapy outcomes.

Wang et al (80) conducted

single-cell transcriptomics analysis and revealed an

immunosuppressive network between periostin (POSTN) CAFs and

atypical chemokine receptor 1 (ACKR1) endothelial cells (ECs) in

TKI-resistant lung cancer, providing insights into the cellular and

molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to targeted

therapies.

Genetic alterations and resistance

Additionally, genetic alterations within tumor cells

can synergize with the TME to drive resistance (Table I). Wang et al (81) showed that SMARCA4 mutations

induced tumor cell-intrinsic defects and resistance to

immunotherapy, suggesting that genetic alterations within tumor

cells may synergize with the TME to drive resistance. Huang et

al (82) demonstrated that

EGFR mutations can induce suppression of CD8+ T cells

and anti-PD-1 resistance via the ERK1/2-p90RSK-TGF-β axis, linking

genetic alterations to immune evasion mechanisms. Kobayashi et

al (83) explored the impact

of bevacizumab and microRNA (miR)-200c on epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) and EGFR-TKI resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer

organoids, suggesting that targeting EMT-related pathways may offer

a promising strategy to overcome resistance.

Multicellular models and combination

therapies

Moreover, advanced multicellular models and

combination therapies are being explored to better understand and

overcome TME-driven resistance (Table

I). Tan et al (84)

evaluated drug resistance for EGFR-TKIs in lung cancer using a

multicellular lung-on-a-chip model, allowing for a more accurate

simulation of the TME and providing valuable data on resistance

mechanisms. Pan et al (85) investigated the role of

disulfidptosis-related genes in radiotherapy resistance of lung

adenocarcinoma, emphasizing the importance of understanding

TME-driven resistance across different therapeutic modalities. Han

et al (86) showed that

osimertinib in combination with anti-angiogenesis therapy may be a

promising option for osimertinib-resistant NSCLC, highlighting the

potential of combination therapies in overcoming resistance

mediated by the TME.

Nanotechnology and resistance

management

Finally, nanotechnology offers innovative approaches

to monitor and manage resistance within the TME (Table I). Shen et al (87) developed an adaptable nanoprobe

integrated with quantitative T1-mapping MRI for accurate

differential diagnosis of multidrug-resistant lung cancer, offering

a novel option for monitoring and managing resistance within the

TME. Lu et al (88) showed

that reprogramming of TAMs via the STAT3/CD47-signal regulatory

protein α axis promoted acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs in lung

cancer, emphasizing the role of immune cell reprogramming in

resistance.

Challenges and future directions

The heterogeneity of the TME presents notable

challenges for the development of effective biomarkers for lung

cancer. Spatial transcriptomics has emerged as a powerful tool for

mapping immune-stromal interactions among different lung cancer

subtypes (89). This technology

allows for the simultaneous analysis of multiple cell types and

their spatial configurations, providing insights into how immune

cells, such as CD8+ T cells and TAMs, interact with

stromal components including CAFs and ECM proteins (90). Studies have shown that the spatial

distribution of immune cells within the TME can influence

therapeutic responses, with immune-excluded or immune-desert tumors

exhibiting poor responses to immunotherapy (90,91). By leveraging spatial

transcriptomics, researchers can better characterize the TME

landscape and identify key biomarkers that predict treatment

outcomes (91). This approach may

not only enhance the understanding of TME heterogeneity but also

aid in the development of personalized therapeutic strategies.

The integration of single-cell sequencing and

artificial intelligence (AI) offers promising options for

developing personalized TME-targeted therapies (92). However, translation into clinical

practice requires validation through large-scale trials, as

exemplified by the ongoing efforts in biomarker-driven studies.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the

understanding of cellular heterogeneity within the TME, revealing

distinct subpopulations of immune cells and their functional states

(92). AI algorithms can analyze

vast datasets generated from scRNA-seq to predict therapeutic

vulnerabilities and optimize treatment combinations. For example,

AI models can identify specific immune cell subsets or signaling

pathways that are critical for tumor progression and resistance,

enabling the design of targeted therapies that disrupt these

interactions (93). This approach

has shown potential in improving the efficacy of immunotherapy and

overcoming resistance in patients with lung cancer (93). However, challenges remain in

translating these findings into clinical practice, including the

need for standardized protocols and the integration of multiomics

data to capture the full complexity of the TME.

Translating TME-targeted therapies into clinical

practice faces several barriers, particularly related to off-target

effects and delivery systems (19,94,95). TME-modulating agents, such as ICIs

and anti-angiogenic drugs, often exhibit off-target effects that

can limit their therapeutic efficacy and cause adverse events

(96). For example, the secretion

of FGL1 by hepatocytes and tumor cells can blunt the efficacy of

anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, highlighting the need for strategies to

enhance treatment specificity (97). Additionally, optimizing delivery

systems to ensure targeted drug delivery and minimize systemic

toxicity remains a critical challenge. Nanoparticle-based drug

delivery systems and targeted conjugates are being explored as

potential solutions to overcome these barriers (98). These approaches aim to enhance the

precision of TME-targeted therapies, ensuring that drugs reach

their intended targets while minimizing off-target effects. Further

research is needed to refine these technologies and evaluate their

clinical feasibility in patients with lung cancer.

The complexity of TME heterogeneity poses notable

hurdles in developing effective therapeutic strategies. The dynamic

nature of the TME, with its diverse cell types and signaling

pathways, makes it difficult to identify consistent biomarkers for

patient stratification and treatment monitoring (99). For example, the coexistence of

immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory signals within the TME can

lead to variable responses to immunotherapy, complicating the

prediction of treatment outcomes. Recent studies have highlighted

the need for a deeper understanding of TME plasticity and the

identification of stable biomarkers that can reliably predict

therapeutic responses across different patient populations

(9,100).

Another critical challenge lies in the technical

limitations of advanced imaging and sequencing technologies. While

spatial transcriptomics and single-cell sequencing have markedly

advanced the understanding of TME heterogeneity, these techniques

require highly specialized equipment and expertise, limiting their

widespread adoption in clinical settings. Furthermore, the

integration of multiomics data remains a complex task, as it

necessitates sophisticated bioinformatics tools and standardized

protocols to ensure data comparability and reproducibility.

In addition, addressing the challenges posed by TME

heterogeneity and developing personalized TME-targeted therapies

requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates advanced

technologies, including spatial transcriptomics, single-cell

sequencing and AI. Overcoming clinical translation barriers will

necessitate innovative strategies to enhance drug specificity and

delivery. By addressing these challenges, more effective and

personalized treatments may be developed for patients with lung

cancer.

Therapeutic strategies and clinical

application of the TME

Therapeutic strategies targeting the TME offer

innovative approaches to overcome resistance and improve outcomes

in lung cancer treatment (100).

By modulating the immune microenvironment (Table II) and targeting metabolic and

epigenetic pathways (Table

III), researchers and clinicians are developing more effective

and personalized treatment regimens. These strategies hold the

promise of enhancing the efficacy of existing therapies and

addressing the challenges posed by the dynamic and heterogeneous

nature of the TME.

| Table IIStudies on immune

microenvironment-modulating therapeutic strategies in lung cancer

treatment. |

Table II

Studies on immune

microenvironment-modulating therapeutic strategies in lung cancer

treatment.

| First author,

year |

Intervention/Target | Study type | Model | Clinical

value/Treatment outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Forde, 2018 | Neoadjuvant

PD-1 | Phase II trial | Resectable

NSCLC | 45% major

pathological response; enhanced T-cell clonality and reduced

immunosuppressive cells | (104) |

| Niemeijer,

2018 | PD-1/PD-L1 PET

imaging | Observational | Advanced NSCLC | Identified spatial

heterogeneity of PD-1/PD-L1; associated with ICI response | (105) |

| Zhang, 2018 | Anti-PD-1 vs.

anti-PD-L1 + chemo | Retrospective | Squamous NSCLC | Comparable efficacy

(ORR: 40-45%); higher pneumonitis risk with anti-PD-L1 | (106) |

| Bozorgmehr,

2019 | Nivolumab +

radiotherapy | Phase II trial | Advanced NSCLC | Synergistic effect:

ORR 45 vs. 29% (monotherapy); increased CD8+ T-cell

infiltration | (107) |

| Zhao, 2019 | Apatinib + PD-1

blockade | Phase Ib/II | NSCLC | Optimized TME via

VEGF inhibition; improved PFS (7.1 vs. 4.2 months) | (108) |

| Leighl, 2021 | Durvalumab +

tremelimumab | Phase II trial | PD-1-resistant

NSCLC | Modest activity

(ORR: 9%); grade 3-4 toxicity in 35% of patients | (109) |

| Ott, 2020 | Neoantigen vaccine

+ anti-PD-1 | Phase Ib trial | Advanced NSCLC | Enhanced

tumor-specific T-cell responses; ORR 50% in NSCLC cohort | (110) |

| Awad, 2022 | NEO-PV-01 vaccine +

chemotherapy/ICI | Phase I/II | Non-squamous

NSCLC | Feasibility

confirmed; 2-year OS rate 75% in responders | (111) |

| Li, 2015 | TAM reprogramming

(Fuzheng Sanjie) | Preclinical | Lewis lung

cancer | Reduced tumor

growth via M2-to-M1 polarization; improved CD8+ T-cell

infiltration | (112) |

| Li, 2018 | Hydroxychloroquine

+ chemotherapy | Preclinical | NSCLC | Enhanced

chemosensitivity; reduced M2-TAMs and increased M1-like

macrophages | (113) |

| Zhang, 2021 |

EGFR-specific

CAR-T cells | Phase I trial | Relapsed NSCLC | Manageable safety;

median PFS 4.1 months; 30% disease control rate | (121) |

| Table IIIStudies on therapeutic strategy that

target tumor microenvironment components in lung cancer

treatment. |

Table III

Studies on therapeutic strategy that

target tumor microenvironment components in lung cancer

treatment.

| First author,

year |

Intervention/Target | Study type | Model | Clinical

value/Treatment outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Li, 2020 | FUT8 inhibition in

CAFs | Preclinical | NSCLC | Reduced EGFR core

fucosylation; suppressed CAF-mediated tumor proliferation | (128) |

| Yang, 2020 | CAF-derived

exosomal miR-210 | Preclinical | NSCLC | Promoted metastasis

via the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway; reversed by miR-210 inhibition | (129) |

| Chen, 2024 | CAF-secreted

SERPINE2 | Preclinical | NSCLC | Enhanced tumor

resistance via exosomal transfer; SERPINE2 knockdown restored

chemosensitivity | (130) |

| Sun, 2024 | PRRX1-OLR1 axis in

CAFs | Preclinical | NSCLC | Promoted immune

suppression; dual targeting reduced MDSC infiltration | (131) |

| Wang, 2013 | Integrin β1

inhibition | Preclinical | NSCLC | Suppressed

metastasis via ERK1/2 pathway inhibition; reduced ECM adhesion | (133) |

| Wang, 2013 | miR-29c targeting

ECM | Preclinical | NSCLC | Inhibited integrin

β1/MMP2; reduced lung metastasis in xenografts | (134) |

| Shie, 2023 | Acidosis-induced

ECM remodeling | Preclinical | NSCLC | Promoted

vasculogenic mimicry; acidosis blockade suppressed metastatic

colonization | (138) |

| Abdel-Hafez,

2024 | Inhalable

ECM-modulating nanoparticles | Preclinical | NSCLC | Enhanced drug

delivery via ECM degradation; improved tumor penetration | (140) |

| Cai, 2024 | Apatinib +

chemotherapy/ICI | Phase II trial |

KRAS-mutant

NSCLC | Improved PFS (8.2

vs. 5.1 months); tumor cavitation linked to anti-angiogenic therapy

response | (145) |

| Zhang, 2024 | Anti-angiogenic

therapy + RT/ICI | Retrospective | NSCLC brain

metastasis | Intracranial ORR

45%; median OS 14.7 months | (146) |

Immune microenvironment modulation

ICIs

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment landscape of

NSCLC by targeting key pathways such as PD-1, PD-L1 and cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) (101). Large clinical trials, including

CHECKMATE-227 and KEYNOTE-024, have established the efficacy of

ICIs in improving overall survival, underscoring their clinical

importance (102,103). These therapies aim to enhance

the antitumor immune response by blocking inhibitory signals that

suppress T-cell activity within the TME. PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors

are the most extensively studied ICIs in NSCLC. Forde et al

(104) demonstrated the

potential of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade (pembrolizumab) in

resectable lung cancer, showing notable tumor regression and

increased major histological response rates. In addition, grade ≥3

adverse events were reported in <10% of patients, with the most

common being fatigue and elevated transaminases. Similarly,

Niemeijer et al (105)

utilized PET imaging to identify PD-1 and PD-L1 expression patterns

in patients with NSCLC, providing insights into the spatial

distribution of these targets within the TME. However,

discrepancies in response rates across studies highlight the need

for biomarker-guided patient selection. Zhang et al

(106) compared the efficacy of

anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies in combination with chemotherapy

for advanced squamous NSCLC, concluding that both approaches were

effective but with varying toxicity profiles. This finding

underscores the importance of optimizing treatment combinations

based on tumor subtype and patient-specific factors.

Combining ICIs with other therapies, such as

radiotherapy or anti-angiogenic agents, has shown promise in

enhancing therapeutic efficacy. Nivolumab plus radiotherapy has

been reported to yield an ORR of 45%, with grade ≥3 toxicities in

18% of patients (primarily radiation pneumonitis and lymphopenia)

(107). By contrast, low-dose

apatinib combined with PD-1 blockade resulted in grade ≥3 adverse

events in 15% of patients, mainly hypertension and hand-foot

syndrome (108). These data

facilitate comparative risk-benefit assessment across TME-targeted

strategies.

Targeting multiple immune checkpoints, such as PD-1

and CTLA-4, has emerged as a strategy to amplify immune responses;

however, this approach is often limited by substantial toxicity.

Leighl et al (109)

evaluated the combination of durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) and

tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4) in patients with

anti-PD-1/PD-L1-resistant NSCLC, showing only modest activity (ORR:

9%) but grade 3-4 toxicities in 35% of patients. Similarly, the

CHECKMATE-227 trial, while demonstrating survival benefit, reported

treatment-related adverse events in 76% of patients receiving

nivolumab plus ipilimumab, with 33% experiencing grade 3-4 events

(103). These findings highlight

the challenging risk-benefit balance of dual checkpoint blockade,

particularly in heavily pretreated patients, and underscore the

need for better patient stratification and toxicity management

strategies.

Previous studies have explored innovative

combinations, such as personalized neoantigen vaccines. Ott et

al (110) reported promising

results with a neoantigen vaccine combined with anti-PD-1 therapy

in patients with advanced melanoma and NSCLC. Similarly, Awad et

al (111) demonstrated the

feasibility of integrating neoantigen vaccines with chemotherapy

and anti-PD-1 therapy in non-squamous NSCLC. These approaches

leverage tumor antigens to enhance immune recognition, potentially

overcoming resistance mechanisms within the TME.

Immune cells

Immune cells within the TME serve a critical role in

modulating tumor progression and therapeutic resistance in lung

cancer. This section focuses on the therapeutic strategies and

clinical applications of targeting specific immune cell

populations, such as TAMs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)

and chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells.

Natural product-based interventions, such as herbal

extracts, have shown immunomodulatory potential in preclinical

models. Li et al (112)

demonstrated that the Fuzheng Sanjie recipe could reprogram TAMs

and reduce tumor growth in Lewis lung cancer mice. Similarly, Gao

et al (113) reported

that ginseng extract altered the behavior of A549 lung cancer cells

and TAMs in co-culture systems. However, the translational

potential of these natural products is limited by several factors,

including undefined active components, batch-to-batch variability,

poor bioavailability and a lack of rigorous clinical trial data

(114). While these studies

provide valuable insights into TME modulation, their clinical

applicability remains uncertain without standardized formulations

and validation in human trials. Li et al (115) showed that hydroxychloroquine

could enhance chemosensitivity and promote the transition of

M2-TAMs to M1-like macrophages, thereby suppressing tumor growth in

NSCLC. However, discrepancies exist in the effectiveness of

TAM-targeted therapies, as some studies highlight the challenges of

achieving consistent reprogramming of TAMs across different tumor

models (47,115).

TILs are a diverse population of immune cells that

infiltrate the tumor site and serve a pivotal role in antitumor

immune responses (116).

CD8+ T cells, a major subset of TILs, are particularly

important for their ability to recognize and kill tumor cells;

however, the function of TILs is often suppressed within the

immunosuppressive TME (116).

Mechanistically, TILs can be inhibited through several pathways.

For example, the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules such

as PD-1 and PD-L1 on TILs can lead to T-cell exhaustion, reducing

their cytotoxic activity against tumor cells (117). Furthermore, Tregs and MDSCs

within the TME can secrete immunosuppressive cytokines, including

IL-10 and TGF-β, which further suppress the activation and

proliferation of TILs (118).

Additionally, the metabolic environment of the TME, characterized

by hypoxia and high levels of adenosine, can impair TIL function by

promoting the expression of inhibitory receptors and reducing the

availability of essential nutrients (119).

The spatial distribution and density of TILs within

tumors can predict response to immunotherapy. For example, tumors

with a high density of CD8+ TILs in the tumor core tend

to respond better to ICIs compared with those with a peripheral

distribution of TILs (119).

This highlights the importance of understanding not only the

presence but also the localization and functional state of TILs in

the TME. Sumitomo et al (120) investigated the association

between PD-L1/PD-L2 expression and TILs in NSCLC, revealing that

M2-TAMs and TILs interact to create an immunosuppressive TME. This

previous study underscored the importance of targeting both TAMs

and TILs to enhance therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, CAR-T cells

have shown promise in hematological malignancies but face notable

challenges in solid tumors such as lung cancer. Zhang et al

(121) performed a Phase I trial

of EGFR-specific CAR-T cells in relapsed/refractory NSCLC,

demonstrating manageable safety and preliminary efficacy. However,

the therapeutic potential of CAR-T in solid tumors is limited by

several factors, including on-target/off-tumor toxicity, inadequate

tumor infiltration and the immunosuppressive TME (122). Additionally, manufacturing

complexity, high costs and the risk of cytokine release syndrome

further constrain their widespread clinical application (123). Current research focuses on

improving CAR-T design to overcome these barriers, but their role

in lung cancer remains investigational.

Emerging evidence has suggested that targeting other

immune cells, such as MDSCs, may also enhance therapeutic efficacy.

For example, Kong et al (124) showed that the Modified Bushen

Yiqi formula reduced the chemotactic recruitment of MDSCs in Lewis

lung cancer-bearing mice, thereby enhancing antitumor immunity.

Therapies that target TME components

CAFs

CAFs are a critical component of the TME and serve a

multifaceted role in promoting tumor progression and therapeutic

resistance in lung cancer (125). CAFs contribute to tumor

progression through various mechanisms, including promoting cancer

cell proliferation, enhancing metastasis and inducing therapeutic

resistance (126). Li et

al (127) demonstrated that

α1,6-fucosyltransferase regulates the cancer-promoting capacity of

CAFs by modifying EGFR core fucosylation in NSCLC. Similarly, Yang

et al (128) showed that

exosomes derived from CAFs containing miR-210 promoted NSCLC

migration and invasion through the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway.

CAFs are also implicated in therapeutic resistance.

Chen et al (129)

reported that CAFs can transfer SERPINE2 via exosomes, enhancing

tumor progression and resistance to treatment in lung cancer.

Additionally, Sun et al (130) highlighted the role of the paired

related homeobox 1-oxLDL receptor 1 axis in supporting

CAFs-mediated immune suppression and tumor progression, suggesting

potential therapeutic targets.

CAFs influence tumor metabolism and signaling

pathways to promote resistance. Wang et al (80) revealed an immunosuppressive

network between POSTN CAFs and ACKR1 ECs in TKI-resistant lung

cancer, emphasizing the role of CAFs in mediating resistance to

targeted therapies. Furthermore, studies have shown that CAFs

promote glycolysis in NSCLC cells, enhancing DNA damage repair and

radioresistance (126,128,129).

ECM

The ECM is a critical component of the TME, and

serves an important role in lung cancer progression and therapeutic

resistance. Targeting the ECM offers promising therapeutic

strategies to enhance treatment outcomes. Integrins and MMPs are

key mediators of cancer cell adhesion and invasion. Wang et

al (131) demonstrated that

shikonin attenuated lung cancer cell adhesion to the ECM and

metastasis by inhibiting integrin β1 expression and the ERK1/2

signaling pathway. Similarly, Wang et al (132) showed that miR-29c suppressed

lung cancer cell adhesion to the ECM and metastasis by targeting

integrin β1 and MMP2. These studies highlight the potential of

targeting integrins and MMPs to reduce metastasis and improve

patient outcomes.

ECM degradation is a critical step in tumor

invasion and metastasis. Bi et al (133) reported that PRDM14 could promote

the migration of human NSCLC cells through ECM degradation in

vitro. Additionally, Zhang et al (134) demonstrated that protein arginine

methyltransferase 1 small hairpin RNA inhibited NSCLC cell

migration by suppressing EMT, ECM degradation, and Src

phosphorylation. These findings underscore the importance of

targeting ECM degradation pathways to prevent tumor

progression.

ECM remodeling contributes to therapeutic

resistance in lung cancer. Wang et al (135) revealed that stromal ECM is a

microenvironmental cue that can promote resistance to EGFR-TKIs in

lung cancer cells. Furthermore, Shie et al (136) showed that acidosis promoted the

metastatic colonization of lung cancer via remodeling of the ECM

and vasculogenic mimicry. These studies emphasize the role of ECM

remodeling in mediating therapeutic resistance and the need for

strategies to modulate ECM composition.

Previous studies have explored innovative

approaches to target the ECM. Peláez et al (137) demonstrated that sterculic acid

can alter the expression of adhesion molecules and ECM compounds to

regulate the migration of lung cancer cells. Additionally,

Abdel-Hafez et al (138)

investigated inhalable nano-structured microparticles for ECM

modulation as a potential delivery system for lung cancer. These

approaches offer promising avenues to enhance therapeutic efficacy

by modulating the ECM.

Immune cells

Emerging evidence has underscored the therapeutic

value of targeting immune cell-TME crosstalk. For example, beyond

herbal compounds, previous studies have highlighted that modulation

of TAM polarity via STAT3 inhibition or CD47-SIRPα axis blockade

can resensitize EGFR-TKI-resistant tumors by restoring phagocytic

clearance and enhancing T-cell infiltration (88,115). Furthermore, the interaction

between immune cells and other TME components, such as CAFs and

ECM, can modulate the overall immune response, affecting the

efficacy of immunotherapy.

Anti-angiogenic therapy

Anti-angiogenic therapy has emerged as a promising

strategy in the treatment of lung cancer, targeting the VEGF

pathway and other angiogenic factors to normalize tumor blood

vessels, alleviate hypoxia and enhance drug delivery (139). The VEGF pathway is a critical

target for anti-angiogenic therapy (140). The phase III IMpower150 trial

demonstrated that combining atezolizumab, bevacizumab and

chemotherapy markedly improved survival in non-squamous NSCLC,

providing robust clinical validation (141). Similarly, Qiang et al

(142) demonstrated the efficacy

of first-line chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy or

anti-angiogenic therapy in advanced KRAS-mutant NSCLC, showing

improved progression-free survival. Similarly, Cai et al

(143) reported tumor cavitation

in patients with NSCLC receiving anti-angiogenic therapy with

apatinib, highlighting the potential of this approach in specific

patient populations.

Combining anti-angiogenic therapy with other

modalities has shown promise in enhancing therapeutic efficacy.

Zhang et al (146)

evaluated the combination of anti-angiogenic therapy, radiotherapy

and PD-1 inhibitors in patients with driver gene-negative NSCLC

brain metastases, demonstrating improved outcomes. Additionally,

Song et al (145)

reported the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors combined with

anti-angiogenic therapy in NSCLC with brain metastases, further

supporting the benefits of multi-modal approaches.

Despite initial success, resistance to

anti-angiogenic therapy remains a challenge. Studies have

identified mechanisms, such as upregulation of compensatory

pro-angiogenic factors (for example, basic FGF, platelet-derived

growth factor and VEGF-C) and recruitment of bone marrow-derived

endothelial progenitor cells as key contributors to resistance

(146,147). Furthermore, tumor heterogeneity

and the TME serve notable roles in mediating resistance,

necessitating strategies to overcome these limitations.

Novel therapeutic approaches:

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and bispecific antibodies

In addition to the aforementioned therapies, novel

approaches such as ADCs and bispecific antibodies are emerging as

promising strategies in the treatment of lung cancer. ADCs are

engineered molecules that combine the specificity of antibodies

with the potency of cytotoxic drugs. They selectively deliver

chemotherapy agents to cancer cells expressing specific antigens,

thereby minimizing off-target effects (141). For example, enfortumab vedotin,

an ADC targeting Nectin-4, has shown notable efficacy in patients

with advanced NSCLC. In a phase I/II trial, an ORR of 41% and a

median duration of response of 10.5 months was demonstrated

(141). Another ADC, sacituzumab

govitecan, which targets Trop-2, has also exhibited promising

results in early-phase trials for NSCLC (6). These ADCs represent a novel frontier

in personalized lung cancer therapy by leveraging antigen

specificity to enhance treatment efficacy and reduce systemic

toxicity. Bispecific antibodies, which can simultaneously bind to

two different antigens, offer unique advantages in cancer

immunotherapy. They can redirect immune cells to tumor cells or

modulate immune checkpoints more effectively. For example,

bispecific antibodies targeting PD-L1 and TGF-β have been developed

to overcome immunosuppression in the TME (148). Preclinical studies have shown

that these bispecific antibodies can enhance T-cell activation and

tumor cell killing (148,149).

Additionally, bispecific T-cell engagers are being explored to

redirect T cells to cancer cells expressing specific antigens, such

as EGFR or HER2, which are frequently upregulated in lung cancer

(149,150). Early clinical trials have

indicated that bispecific antibodies can achieve tumor regression

in a subset of patients with refractory NSCLC, highlighting their

potential as next-generation immunotherapies (148-150).

These emerging therapies, including ADCs and

bispecific antibodies, are expected to markedly impact the

treatment landscape of lung cancer by addressing the limitations of

current targeted therapies and immunotherapies. Further clinical

research is warranted to optimize their application and combination

strategies in the context of the TME.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the TME drives drug resistance in

lung cancer through immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming and

epigenetic modulation. While targeting TME components shows

promise, several challenges remain. Immune-based strategies, such

as dual checkpoint blockade and CAR-T therapy, are limited by

toxicity and poor efficacy in solid tumors. Natural product

interventions face translational hurdles due to undefined

mechanisms and a lack of clinical validation. Emerging

technologies, such as spatial transcriptomics and nanodrug

delivery, offer potential solutions but require further

optimization for clinical application. Future research should

prioritize not only multiomics integration but also rigorous

preclinical models and well-designed clinical trials to distinguish

promising research possibilities from preliminary findings.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

LiL contributed to the literature review on the

heterogeneity of the lung cancer microenvironment. LY wrote the

part about the role of the tumor microenvironment in treatment

resistance. HL and TS were involved in the literature search and

analysis, as well as in the writing of the manuscript. LihL, as the

corresponding author, oversaw the entire review process, provided

critical guidance and revised the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the First People's Hospital of Baiyin

College Scientific Research Project (grant no. 2021YK-01; project

name: Clinical research on thoracoscopic lobectomy and

segmentectomy in the treatment of early lung cancer).

References

|

1

|

Wéber A, Morgan E, Vignat J, Laversanne M,

Pizzato M, Rumgay H, Singh D, Nagy P, Kenessey I, Soerjomataram I

and Bray F: Lung cancer mortality in the wake of the changing

smoking epidemic: A descriptive study of the global burden in 2020

and 2040. BMJ Open. 13:e0653032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Oxnard GR, Arcila ME, Sima CS, Riely GJ,

Chmielecki J, Kris MG, Pao W, Ladanyi M and Miller VA: Acquired

resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant lung

cancer: Distinct natural history of patients with tumors harboring

the T790M mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 17:1616–1622. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Miyata H, Shigeto H, Ikeya T, Ashizawa T,

Iizuka A, Kikuchi Y, Maeda C, Kanematsu A, Yamashita K, Urakami K,

et al: Localization of epidermal growth factor receptor-mutations

using PNA: DNA probes in clinical specimens from patients with

non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 15:113142025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Son B, Lee S, Youn H, Kim E, Kim W and

Youn B: The role of tumor microenvironment in therapeutic

resistance. Oncotarget. 8:3933–3945. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Yu H, Zhang W, Xu XR and Chen S: Drug

resistance related genes in lung adenocarcinoma predict patient

prognosis and influence the tumor microenvironment. Sci Rep.

13:96822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ,

Falchook GS, Wolf J, Italiano A, Schuler M, Borghaei H, Barlesi F,

et al: Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl

J Med. 384:2371–2381. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Said SS and Ibrahim WN: Cancer resistance

to immunotherapy: Comprehensive insights with future perspectives.

Pharmaceutics. 15:11432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Glaviano A, Lau HS, Carter LM, Lee EHC,

Lam HY, Okina E, Tan DJJ, Tan W, Ang HL, Carbone D, et al:

Harnessing the tumor microenvironment: Targeted cancer therapies

through modulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Hematol

Oncol. 18:62025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tian Y, Yang Y, He L, Yu X, Zhou H and

Wang J: Exploring the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer to

develop a prognostic model and predict immunotherapy responses. Sci

Rep. 15:125692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tan Z, Xue H, Sun Y, Zhang C, Song Y and

Qi Y: The role of tumor inflammatory microenvironment in lung

cancer. Front Pharmacol. 12:6886252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu Y, Liang J, Zhang Y and Guo Q: Drug

resistance and tumor immune microenvironment: An overview of

current understandings (Review). Int J Oncol. 65:962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Heydenreich B, Bellinghausen I, Lorenz S,

Henmar H, Strand D, Würtzen PA and Saloga J: Reduced in vitro

T-cell responses induced by glutaraldehyde-modified allergen

extracts are caused mainly by retarded internalization of dendritic

cells. Immunology. 136:208–217. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mai Z, Lin Y, Lin P, Zhao X and Cui L:

Modulating extracellular matrix stiffness: A strategic approach to

boost cancer immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 15:3072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen K, Luo L, Li Y and Yang G:

Reprogramming the immune microenvironment in lung cancer. Volume.

16:16848892025.

|

|

16

|

Chandra R, Ehab J, Hauptmann E, Gunturu

NS, Karalis JD, Kent DO, Heid CA, Reznik SI, Sarkaria IS, Huang H,

et al: The current state of tumor Microenvironment-specific

therapies for Non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel).

17:17322025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

He ZN, Zhang CY, Zhao YW, He SL, Li Y, Shi

BL, Hu JQ, Qi RZ and Hua BJ: Regulation of T cells by

myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Emerging immunosuppressor in lung

cancer. Discov Oncol. 14:1852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lim JU, Lee E, Lee SY, Cho HJ, Ahn DH,

Hwang Y, Choi JY, Yeo CD, Park CK and Kim SJ: Current literature

review on the tumor immune micro-environment, its heterogeneity and

future perspectives in treatment of advanced non-small cell lung

cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 12:857–876. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Genova C, Dellepiane C, Carrega P,

Sommariva S, Ferlazzo G, Pronzato P, Gangemi R, Filaci G, Coco S

and Croce M: Therapeutic implications of tumor microenvironment in

lung cancer: Focus on immune checkpoint blockade. Front Immunol.

12:7994552021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Cao Q, Li C, Li Y, Kong X, Wang S and Ma

J: Tumor microenvironment and drug resistance in lung

adenocarcinoma: Molecular mechanisms, prognostic implications, and

therapeutic strategies. Discov Oncol. 16:2382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chu X, Tian Y and Lv C: Decoding the

spatiotemporal heterogeneity of Tumor-associated macrophages. Mol

Cancer. 23:1502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Mei S, Zhang H, Hirz T, Jeffries NE, Xu Y,

Baryawno N, Wu S, Wu CL, Patnaik A, Saylor PJ, et al: Single-cell

and spatial transcriptomics reveal a Tumor-associated macrophage

subpopulation that mediates prostate cancer progression and

metastasis. Mol Cancer Res. 23:653–665. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ashrafi A, Akter Z, Modareszadeh P,

Modareszadeh P, Berisha E, Alemi PS, Chacon Castro MDC, Deese AR

and Zhang L: Current landscape of therapeutic resistance in lung

cancer and promising strategies to overcome resistance. Cancers

(Basel). 14:45622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Guo T and Xu J: Cancer-associated

fibroblasts: A versatile mediator in tumor progression, metastasis,

and targeted therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 43:1095–1116. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wu C, Gu J, Gu H, Zhang X, Zhang X and Ji

R: The recent advances of cancer associated fibroblasts in cancer

progression and therapy. Front Oncol. 12:10088432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Papavassiliou KA, Sofianidi AA, Gogou VA

and Papavassiliou AG: Drugging the tumor microenvironment epigenome

for therapeutic interventions in NSCLC. J Cancer. 16:1832–1835.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tong L, Jiménez-Cortegana C, Tay AHM,

Wickström S, Galluzzi L and Lundqvist A: NK cells and solid tumors:

Therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Mol Cancer.

21:2062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu J, Wu M, Yang Y, Wang Z, He S, Tian X

and Wang H: γδ T cells and the PD-1/PD-L1 axis: A love-hate

relationship in the tumor microenvironment. J Transl Med.

22:5532024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mancini A, Gentile MT, Pentimalli F,

Cortellino S, Grieco M and Giordano A: Multiple aspects of matrix

stiffness in cancer progression. Front Oncol. 14:14066442024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Henke E, Nandigama R and Ergün S:

Extracellular matrix in the tumor microenvironment and its impact

on cancer therapy. Front Mol Biosci. 6:1602019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Marrugal Á, Ojeda L, Paz-Ares L,

Molina-Pinelo S and Ferrer I: Proteomic-based approaches for the

study of cytokines in lung cancer. Dis Markers. 2016:21386272016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang A, Miao K, Sun H and Deng CX: Tumor

heterogeneity reshapes the tumor microenvironment to influence drug

resistance. Int J Biol Sci. 18:3019–3033. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li X, Shang S, Wu M, Song Q and Chen D:

Gut microbial metabolites in lung cancer development and

immunotherapy: Novel insights into gut-lung axis. Cancer Lett.

598:2170962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li J, Shi B, Ren X, Hu J, Li Y, He S,

Zhang G, Maolan A, Sun T, Qi X, et al: Lung-intestinal axis,

Shuangshen granules attenuate lung metastasis by regulating the

intestinal microbiota and related metabolites. Phytomedicine.

132:1558312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ankudavicius V, Nikitina D, Lukosevicius

R, Tilinde D, Salteniene V, Poskiene L, Miliauskas S, Skieceviciene

J, Zemaitis M and Kupcinskas J: Detailed characterization of the

Lung-gut microbiome axis reveals the link between PD-L1 and the

microbiome in Non-Small-cell lung cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci.

25:23232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dong Q, Chen ES, Zhao C and Jin C:

Host-Microbiome interaction in lung cancer. Front Immunol.

12:6798292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hunt PJ, Andújar FN, Silverman DA and Amit

M: Mini-review: Trophic interactions between cancer cells and

primary afferent neurons. Neurosci Lett. 746:1356582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hernandez S, Serrano AG and Solis Soto LM:

The role of nerve fibers in the tumor Immune microenvironment of

solid tumors. Adv Biol (Weinh). 6:22000462022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Li X, Peng X, Yang S, Wei S, Fan Q, Liu J,

Yang L and Li H: Targeting tumor innervation: Premises, promises,

and challenges. Cell Death Discov. 8:1312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yang Y, Ye WL, Zhang RN, He XS, Wang JR,

Liu YX, Wang Y, Yang XM, Zhang YJ and Gan WJ: The role of TGF-β

signaling pathways in cancer and its potential as a therapeutic

target. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021:66752082021.

|

|

41

|

Jiang C, Zhang N, Hu X and Wang H:

Tumor-associated exosomes promote lung cancer metastasis through

multiple mechanisms. Mol Cancer. 20:1172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yang J, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Yu X and

Shi S: Epigenetic regulation in the tumor microenvironment:

Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 8:2102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yu W, Hua Y, Qiu H, Hao J, Zou K, Li Z, Hu

S, Guo P, Chen M, Sui S, et al: PD-L1 promotes tumor growth and

progression by activating WIP and β-catenin signaling pathways and

predicts poor prognosis in lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 11:5062020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Xiao K, Zhang S, Peng Q, Du Y, Yao X, Ng

II and Tang H: PD-L1 protects tumor-associated dendritic cells from

ferroptosis during immunogenic chemotherapy. Cell Rep.

43:1148682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Shi AP, Tang XY, Xiong YL, Zheng KF, Liu

YJ, Shi XG, Lv Y, Jiang T, Ma N and Zhao JB: Immune checkpoint LAG3

and its ligand FGL1 in cancer. Front Immunol. 12:7850912021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Villarroel-Espindola F, Yu X, Datar I,

Mani N, Sanmamed M, Velcheti V, Syrigos K, Toki M, Zhao H, Chen L,

et al: Spatially resolved and quantitative analysis of VISTA/PD-1H

as a novel immunotherapy target in human Non-small cell lung

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 24:1562–1573. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

47

|

Wang S, Wang J, Chen Z, Luo J, Guo W, Sun

L and Lin L: Targeting M2-like tumor-associated macrophages is a

potential therapeutic approach to overcome antitumor drug

resistance. NPJ Precis Oncol. 8:312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Li Y, Zhao L and Li XF: Hypoxia and the

tumor microenvironment. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

20:153303382110363042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zaarour RF, Azakir B, Hajam EY, Nawafleh

H, Zeinelabdin NA, Engelsen AST, Thiery J, Jamora C and Chouaib S:

Role of Hypoxia-mediated autophagy in tumor cell death and

survival. Cancers (Basel). 13:5332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Sasidharan Nair V, Saleh R, Toor SM,

Cyprian FS and Elkord E: Metabolic reprogramming of T regulatory

cells in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 70:2103–2121. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Li X, Yan X, Wang Y, Kaur B, Han H and Yu

J: The Notch signaling pathway: A potential target for cancer

immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 16:452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Luo H, Liu L, Liu X, Xie Y, Huang X, Yang

M, Shao C and Li D: Interleukin-33 (IL-33) promotes DNA

damage-resistance in lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 16:2742025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Boo SH and Kim YK: The emerging role of

RNA modifications in the regulation of mRNA stability. Exp Mol Med.

52:400–408. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Guo Y, Xie Y and Luo Y: The role of Long

Non-coding RNAs in the tumor immune microenvironment. Front

Immunol. 13:8510042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Jiang J, Lu Y, Zhang F, Huang J, Ren XL

and Zhang R: The emerging roles of long noncoding RNAs as hallmarks

of lung cancer. Front Oncol. 11:7615822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Entezari M, Ghanbarirad M, Taheriazam A,

Sadrkhanloo M, Zabolian A, Goharrizi MASB, Hushmandi K, Aref AR,

Ashrafizadeh M, Zarrabi A, et al: Long non-coding RNAs and exosomal

lncRNAs: Potential functions in lung cancer progression, drug

resistance and tumor microenvironment remodeling. Biomed

Pharmacother. 150:1129632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Tian Z, Cen L, Wei F, Dong J, Huang Y, Han

Y, Wang Z, Deng J and Jiang Y: EGFR mutations in non-small cell

lung cancer: Classification, characteristics and resistance to

third-generation EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Review). Oncol

Lett. 30:3752025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Parente P, Parcesepe P, Covelli C,

Olivieri N, Remo A, Pancione M, Latiano TP, Graziano P, Maiello E

and Giordano G: Crosstalk between the tumor microenvironment and

immune system in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Potential

targets for new therapeutic approaches. Gastroenterol Res Pract.