Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes ~80% of

liver malignancies, making it the third most lethal cancer and the

sixth most prevalent malignancy worldwide (1,2).

HCC pathogenesis and progression are influenced by numerous factors

(3,4). Despite recent advances in surgical

resection, targeted pharmacotherapy, precision radiotherapy and

immunotherapy, a significant proportion of HCC patients face

unsatisfactory survival outcomes, attributable to the inherently

aggressive nature of HCC (5-7).

Hence, there is a pressing need to investigate key molecules

involved in HCC development and identify associated diagnostic

markers and treatment targets for enhancing patient prognosis.

The ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0

(RPLP0), an integral component of the RPLP family and a key

ribosomal protein in the 60S subunit, markedly influences cell fate

determination and is intricately involved in tumorigenesis. RPLP0

expression is markedly upregulated in gastric, breast, ovarian,

endometrial and cervical carcinomas and its overexpression is

associated with suboptimal survival outcomes in patients (8-11).

Wang et al (12)

discovered that RPLP0 interacts with NONO independently of the

ribosome and can anchor to damaged DNA, thereby promoting the

autophosphorylation of DNA-dependent protein kinase at the Thr2609

site, enhancing the repair of double-strand breaks and conferring

resistance to radiotherapy. The knockdown of RPLP0 has been

observed to enhance autophagy, a cellular degradation mechanism

targeting cytoplasmic components (13,14) and to trigger G2/M cell

cycle arrest in breast cancer (9). Although RPLP0 abnormal expression

markedly affects tumor progression, its pathophysiological role in

HCC remains to be elucidated.

While prior research has established the involvement

of RPLP0 in HCC development (15), the specific regulatory pathways

and mechanisms governing its regulation remain underexplored.

Therefore, the present study performed an in-depth analysis to

unravel the intricate mechanisms underlying the formation of

regulatory loops through which RPLP0 contributes to HCC

progression. By integrating multiple transcriptomic datasets and

clinical data, coupled with rigorous in vitro and in

vivo experimental procedures, a clinically relevant RPLP0

profile was established in HCC. These results collectively position

RPLP0 as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target, representing a

significant advancement in our understanding of HCC biology and

offering a promising strategy for improving clinical outcomes.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The cell lines THLE-2, SNU-182, Li-7, Huh-7,

PLC/PRF/5, MHCC97-H and HCCLM3 were sourced from the Chinese

Academy of Sciences and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2

in a humidified incubator. THLE-2 cells were cultured in BEGM

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), SNU-182 cells were

propagated in RPMI 1640 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

Li-7 cells were maintained in MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), and Huh-7, PLC/PRF/5, MHCC97-H, and HCCLM3 cells were grown

in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Each of these

media was supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), and the incubator was supplied by Gibco (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For subsequent experiments, Huh-7 and

MHCC97-H cell lines were selected based on their demonstrated

phenotypic stability and experimental reproducibility, making them

suitable for detailed investigation, as well as their

well-characterized properties in HCC research (16). The properties of the cell lines

are given in Table SI.

Tissue samples

Between October 2024 and February 2025, a cohort of

44 paired specimens, comprising tumor and adjacent non-tumor

tissues (designated at sites >5 cm from the tumor margin), was

procured from patients diagnosed with HCC (clinicopathological

features are provided in Table

SII). The median age was 62 years (range, 36-78). These tissue

specimens were exclusively sourced from individuals with untreated

primary HCC who had provided their written informed consent. The

study was performed in strict compliance with the Declaration of

Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Board

under protocol number (2024) CDYFYYLK (07-004).

Bioinformatics analysis

The expression profile and clinical significance of

RPLP0 were systematically evaluated using an integrative

bioinformatics approach that used data from multiple

high-throughput repositories. Specifically, this analysis

incorporated comprehensive datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/),

which includes 371 HCC samples and 50 non-tumor controls; the

Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (https://gtexportal.org/home/index.html), encompassing

110 healthy liver tissues; the Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis (GEPIA)2 repository (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index); and the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) platform (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), using datasets

GSE57957, GSE36411, GSE39791 and GSE76427. R software (version

4.3.2 https://cran.r-project.org/) was used to

assess correlations between RPLP0 expression, histological grading

and tumor staging based on TCGA data. Additionally, pathway

enrichment analysis was performed by stratifying samples into high

and low RPLP0 expression groups. Transcription factors and specific

promoter sequences for RPLP0 were identified using predictive tools

such as the Cistrome Data Browser (http://cistrome.org/db/#/) and JASPAR databases

(https://jaspar.elixir.no/).

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)

PCR

Following the respective manufacturers'

instructions, RNA was extracted with TRIzol® reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), then reverse

transcription and qPCR were performed using the cDNA Synthesis

SuperMix and qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix, respectively (both from

Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The thermocycling

protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min,

followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec.

Melting curve analysis was carried out as follows: 95°C for 15 sec,

60°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 15 sec. Relative mRNA expression

levels were quantified using the comparative 2−ΔΔCq

method (17), with GAPDH serving

as the endogenous control. All experiments were independently

repeated three times. Primer sequences are listed in Table SIII.

Western blotting

To ensure high-fidelity protein extraction, samples

were lysed using RIPA buffer (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors to

preserve post-translational modifications and prevent protein

degradation. The extracted proteins were quantified using a BCA kit

(Thermo Fisher, Inc.). Subsequently, depending on the molecular

weight of the proteins of interest, SDS-PAGE electrophoresis was

executed on gels with either 10 or 12.5% polyacrylamide

concentration. Each lane was loaded with a standardized amount of

total protein (20 μg). Following electrophoresis, proteins

were transferred to 0.45 μm PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma)

using a wet transfer system. The membrane was then blocked with 5%

non-fat milk in TBST (0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature to

prevent non-specific binding. The membrane was incubated overnight

at 4°C with primary antibodies specific to the proteins of

interest, diluted according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

After washing with TBST (0.1% Tween-20), the membrane was incubated

with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room

temperature. The target proteins were ultimately clearly and

precisely detected using an ECL detection system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The resulting band intensities were quantified

by densitometry using ImageJ software (version 1.53m; National

Institutes of Health). Antibodies details are in Table SIV.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered

formalin for 48 h at room temperature, followed by routine

dehydration through a graded ethanol series and embedding in

paraffin. Consecutive sections were cut at a thickness of 4

μm. Following deparaffinization and rehydration, antigen

retrieval was performed using citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous

peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation with 3% hydrogen

peroxide for 10 min. Sections were then permeabilized with 0.2%

Triton X-100 and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; both

from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 1 h at room

temperature. After being placed in contact with the primary

antibody at room temperature for 2 h to promote optimal

antigen-antibody binding, the sections underwent a 30-min

incubation at 37°C with the secondary antibody. Antibodies details

are in Table SIV. Chromogenic

visualization was achieved using a 0.02% diaminobenzidine (DAB)

solution for 5 min, providing clear staining of target proteins.

Subsequently, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for

30 sec to provide nuclear contrast at room temperature, dehydrated

through graded alcohols, cleared in xylene, and air-dried. The

slides were then mounted and examined under light microscopy for

detailed immunohistochemical analysis.

Small interfering (si)RNA, plasmid

transfection and short hairpin (sh)RNA

In the present study, the target cell lines, Huh7

and MHCC97-H cells, were seeded in 6-well plates. Cells were

subjected to transfection using siRPLP0 (150 nM; Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd.) and pECMV-RPLP0 (2.5 μg; MiaoLing

Biology) to knock down and overexpress RPLP0, respectively, using

Lipofectamine® 3000 transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Parallel transfections with si-NC (150 nM) or oe-NC (2.5 μg)

served as negative controls. A c-Myc-specific siRNA (150 nM;

Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) and the plasmid pCMV-c-Myc (2.5

μg; MiaoLing Biology) were employed to knock down and

overexpress c-Myc, respectively. The transfection mixture was

incubated with the cells for 6 h at 37°C, after which it was

replaced with fresh complete medium. Subsequent functional

experiments were typically performed 48 h post-transfection. To

achieve stable RPLP0 knockdown, MHCC97-H cells were transduced with

shRNA specifically targeting RPLP0 (shRPLP0; Hanbio Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50. Following a

48-h incubation at 37°C, stable transductants were selected and

maintained in complete medium supplemented with 2.0 μg/ml

puromycin (Biosharp Life Sciences) for two weeks. Detailed

sequences are listed in Table

SV.

Cell proliferation assay

After successful transfection, the cells were

trypsinized and subsequently resuspended in single-cell

suspensions. For CCK-8 assays, 1,500 cells was dispensed into each

well of a 96-well plate and absorbance was measured at specific

intervals. In the colony-forming efficiency test, 1,000 isolated

cells were uniformly distributed in each well of 6-well plates.

After 12 days, colonies became macroscopically visible and they

were sequentially fixed, stained, air-dried, and photographed.

Transwell assay

Cells were transfected for 48 h, after which 200

μl of a suspension containing 4×104 cells was

introduced into the upper chamber of a Matrigel-coated (incubated

at 37°C for 2 h for gel formation) Transwell system featuring 8

μm pores. Meanwhile, the lower chamber was replenished with

600 μl of DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS. At 48 h, samples

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature,

stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature and

imaged under a light microscope. For migration assays, Transwell

chambers that had not been pretreated with Matrigel were used.

Apoptosis and cell cycle assay

Apoptosis and cell cycle distribution were analyzed

using the Annexin V-PE/7-AAD apoptosis kit and the Cell Cycle

Staining Kit (MultiSciences Biotech Co., Ltd.), respectively,

according to the manufacturer's guidelines. After staining at room

temperature for 30 min in the dark, the samples were analyzed using

a flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Data were processed with

FlowJo software (version 10.1; BD FlowJo) (18). The apoptotic rate was defined as

the combined percentage of early and late apoptotic cells in the

total population.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

Intracellular ROS levels were determined employing

the Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells

underwent staining with 1X Hoechst for 20 min at ambient

temperature and subsequently were incubated in the dark at 37°C

with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min. After incubation, the excess

DCFH-DA was removed by washing the cells three times with

serum-free culture medium to minimize non-specific extracellular

fluorescence. The assessment of ROS levels was performed using

either fluorescence microscopy (Leica Microsystems GmbH) or a flow

cytometer (CytoFLEX; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). During flow cytometry,

the excitation and emission wavelengths were set at 488 nm and 525

nm, respectively, and a total of 10,000 events were acquired per

sample. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.1; BD

FlowJo) (18).

Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) staining

To assess the levels of intracellular

autophagosomes, the present study used an MDC staining kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Cells underwent a 20-min

incubation period in dim conditions at ambient temperature with 1X

Hoechst solution. This was followed by another 30 min of incubation

at 37°C in 500 μl of 1X MDC solution, with darkness

maintained throughout. After washing three times with assay buffer,

the cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Leica

Microsystems GmbH).

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

The collected cells were fixed with a specialized

electron microscopy fixative (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) at 4°C overnight, followed by dehydration through an ethanol

gradient. Subsequently, the samples underwent infiltration with

propylene oxide and were embedded in resin using a progressive

temperature protocol (37°C for 12 h, 45°C for 12 h, and 60°C for 24

h). Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were prepared using an

ultramicrotome, then double-stained with uranyl acetate for 15 min

and lead citrate for 5 min at room temperature. After overnight

drying, the sections were examined utilizing a transmission

electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

The ChIP procedure was performed in strict

accordance with the guidelines furnished by the ChIP assay kit

procured from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Cells grown in 10 cm

dishes at 80-90% confluence were initially fixed with 1%

formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. After quenching with

125 mM glycine, cells were lysed and the chromatin was fragmented

using a non-contact ultrasonicator (Little Scientific Instruments

Co., Ltd.) set at 100% power for 25 min with cycles of 10 sec ON

and 5 sec OFF at 4°C, yielding DNA fragments of 200-600 bp. A 10

μl aliquot of the lysate was reserved and stored at −80°C

for subsequent use as an input. Next, 500 μl of lysate

underwent immunoprecipitation through overnight incubation at 4°C

using protein A/G beads with 5 μl of either anti-c-Myc (4

μg) or anti-IgG antibodies (4 μg). The beads were

washed sequentially with low salt, high salt and LiCl wash buffers

provided in the ChIP assay kit. The purified DNA fragments

subsequently underwent qPCR. Purified DNA fragments were amplified

via PCR using reagents acquired from Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd. and

the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for

3 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing at

60°C for 15 sec, and extension at 72°C for 30 sec; and final

extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were separated on 2%

agarose gels and visualized with GelStain (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.) under UV illumination. The specific primer sequences used for

qPCR in the ChIP assay are presented in Table SVI.

Dual luciferase assay

The promoter sequences of both the native

(wild-type; WT) and altered (mutant; MUT) RPLP0 were cloned into

pGL4 plasmids (Promega Corporation). Afterward, cells seeded in

24-well plates at 70-80% confluence were co-transfected using

Lipofectamine® 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) with either pGL4-RPLP0-WT or pGL4-RPLP0-MUT, together with

the pGL4.74 internal control plasmid and either pCMV-c-Myc or the

corresponding empty vector. After a 48-h incubation period,

luciferase activity was quantified employing the Dual Luciferase

Assay Kit (Promega Corporation).

Xenograft tumor model

A subcutaneous xenograft model was generated using

16 BALB/c nude female mice (4-5 weeks old, 15-16 g; Sibeifu

Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd.) and maintained under strict SPF

conditions (22±1°C; relative humidity 50±10%; a 12/12-h light/dark

cycle, and ad libitum access to sterilized food and water).

Lentivirus-infected MHCC97-H cells, targeting shNC and shRPLP0,

were successfully screened to establish stable cell lines.

Subsequently, an inoculation of 6×106 cells, comprising

either shNC or shRPLP0, was administered at the specified

subcutaneous site in each mouse. The dimensions of the subcutaneous

tumors were precisely assessed and recorded every four days. Tumor

volume was calculated using the formula: length × width2

×0.5. The largest tumor observed in the present study measured

10.82 mm in length and 7.28 mm in width, with a maximum volume of

286.72 mm3. In compliance with animal ethics guidelines,

tumor size was limited to a mean diameter of 20 mm and a volume of

2,000 mm3. Sacrifice was via carbon dioxide

(CO2) inhalation at a chamber displacement rate of

30-50% per min prior to tumor excision, with mortality confirmed by

absent heartbeat and respiration. Animal studies were performed

following ethical guidelines and were approved by the Animal Ethics

Committee (approval no. CDYFY-IACUC-202407QR259).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9

(Dotmatics). For comparisons of RPLP0 mRNA expression between tumor

and adjacent non-tumor tissues from HCC patients, a paired

Student's t-test was applied. Other comparisons between two groups

were conducted using an unpaired Student's t-test. For multiple

group comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc

test was applied. The Spearman correlation coefficient was

determined to assess relationships between variables. Kaplan-Meier

curves and log-rank tests were used to analyze survival prognosis.

Data were presented as mean ± SEM. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

RPLP0 is markedly upregulated in HCC and

its high expression is associated with poorer prognosis

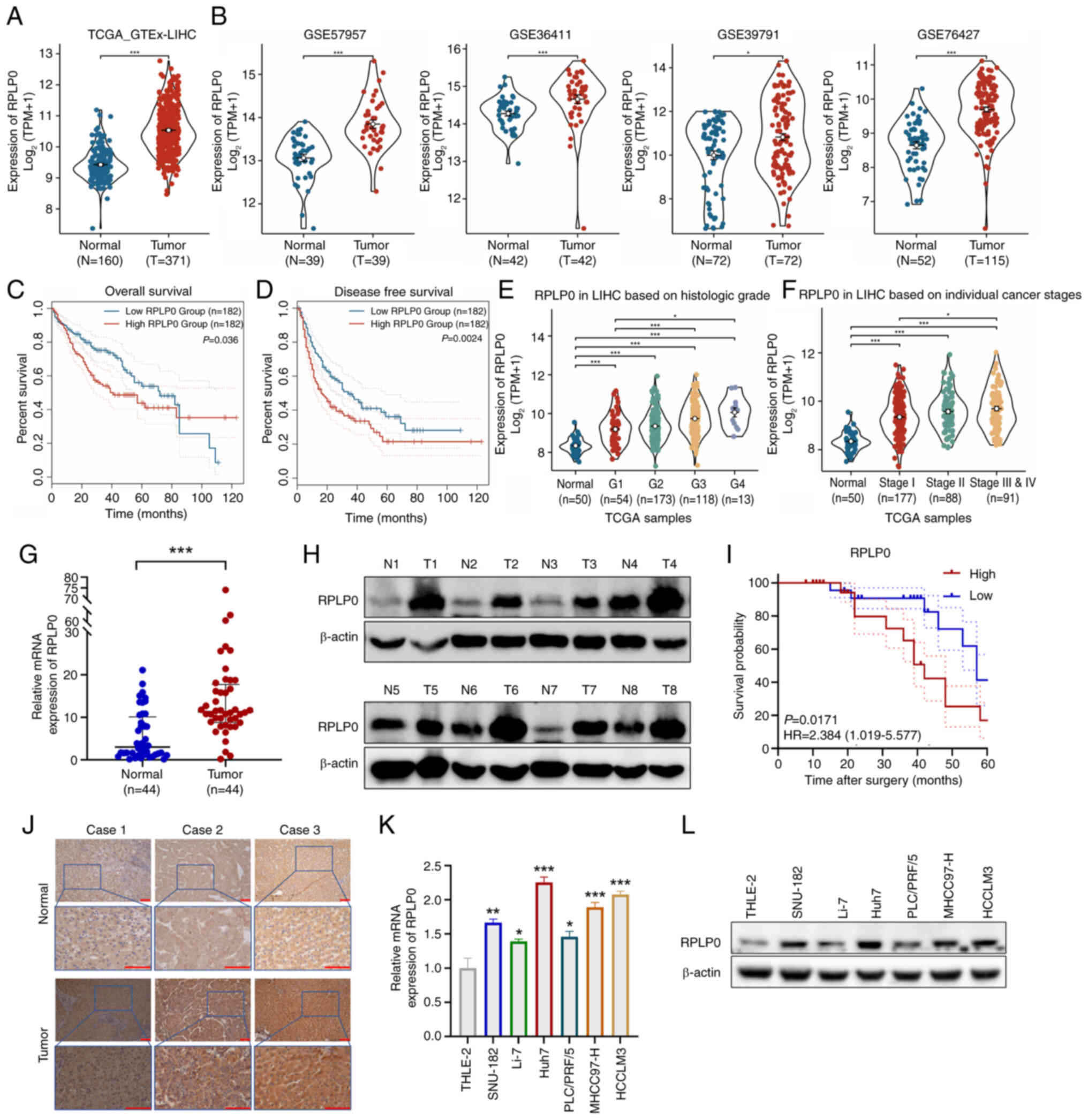

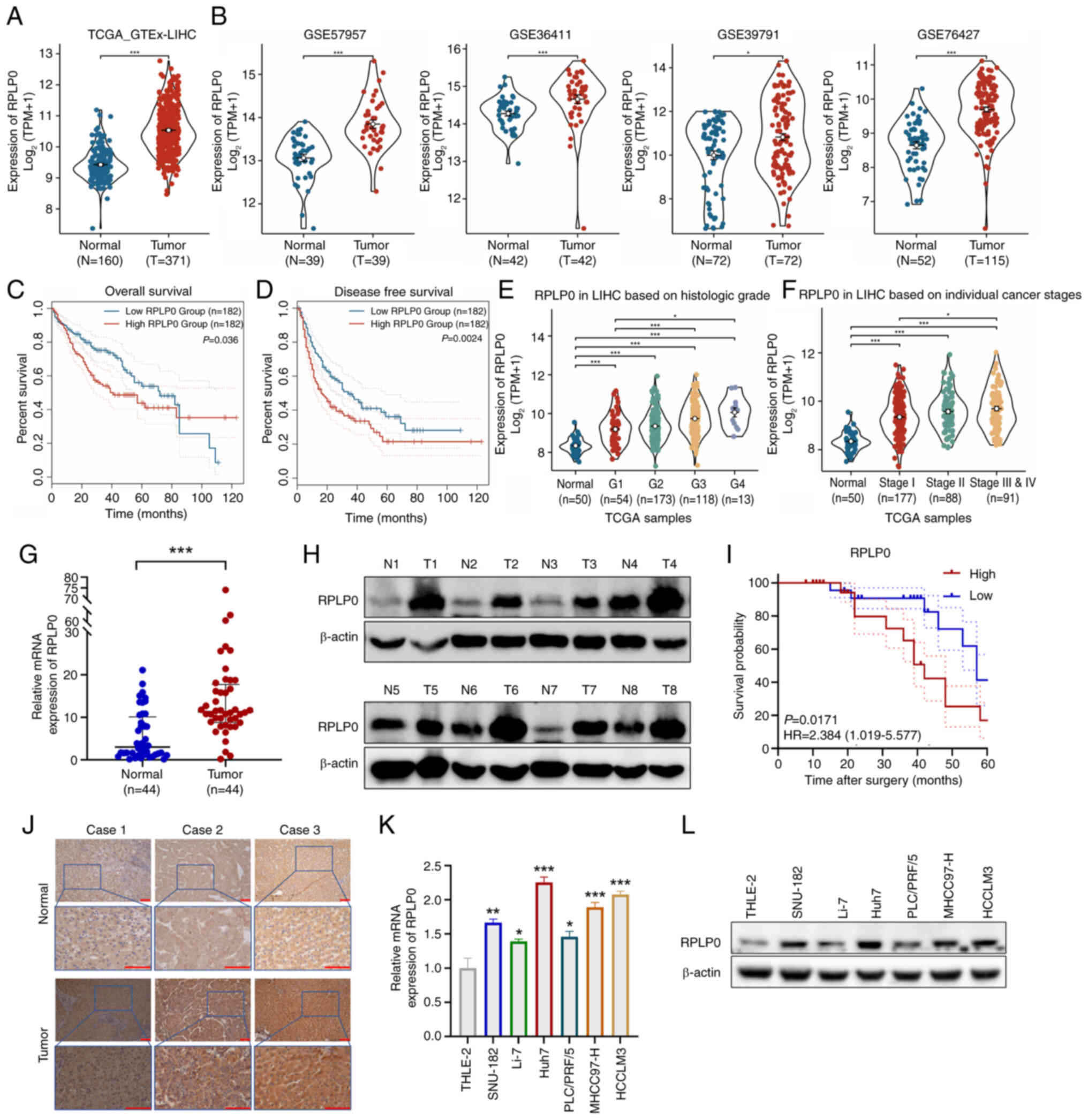

Analyses based on the TCGA and GTEx databases

demonstrated that RPLP0 transcriptome levels were markedly elevated

in HCC samples (Fig. 1A).

Consistent findings were observed in the GSE57957, GSE36411,

GSE39791 and GSE76427 datasets, providing further validation of the

heightened expression of RPLP0 in HCC (Fig. 1B). The GEPIA 2 database revealed

that individuals with elevated RPLP0 levels experienced decreased

overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates

(Fig. 1C and D). TCGA database

analysis showed that high RPLP0 expression levels were associated

with unfavorable histological grades and tumor stages (Fig. 1E and F). Furthermore, comparative

studies of mRNA and protein levels in 44 matched tissues clearly

indicated a marked elevation in RPLP0 in HCC (Fig. 1G and H). After stratifying samples

by median RPLP0 expression, a Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated

that higher RPLP0 expression was markedly associated with inferior

outcomes in HCC patients (Fig.

1I). Immunohistochemical analysis of the collected samples

further validated the upregulation of RPLP0 expression in HCC

tissues (Fig. 1J). Compared with

immortalized hepatocytes, RPLP0 expression was notably higher in

HCC cell lines at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1K and L). Overall, these results

suggest that RPLP0 may be utilized as a diagnostic and prognostic

biomarker in HCC.

| Figure 1Elevated RPLP0 expression is

associated with unfavorable survival outcomes in HCC. (A) RPLP0

expression levels derived from the TCGA_GTEx database. (B)

Confirmation of RPLP0 expression in the GSE57957, GSE36411,

GSE39791 and GSE76427 datasets. Association between RPLP0

expression status and (C) OS and (D) DFS among HCC patients in the

GEPIA2 database. The relationship between RPLP0 expression and (E)

histological grade and (F) cancer stage in the TCGA database. The

expression levels of (G) mRNA and (H) protein for RPLP0 were

analyzed in 44 paired HCC samples. (I) The influence of RPLP0

expression on the survival outcomes of HCC patients. (J)

Immunohistochemical analysis of RPLP0 in HCC and adjacent

non-cancerous tissues (scale bar, 100 μm). RPLP0 (K) mRNA

and (L) protein levels were examined in immortalized hepatocytes

and HCC cell lines. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. RPLP0, ribosomal protein lateral stalk

subunit P0; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TCGA, the cancer genome

atlas; GTEx, the genotype-tissue expression; N, normal; T, tumor;

GEO, gene expression omnibus; GEPIA2, gene expression profiling

interactive analysis; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free

survival. |

RPLP0 downregulation suppresses the

malignant phenotype of HCC cells, inducing apoptosis and

G2/M cell cycle arrest

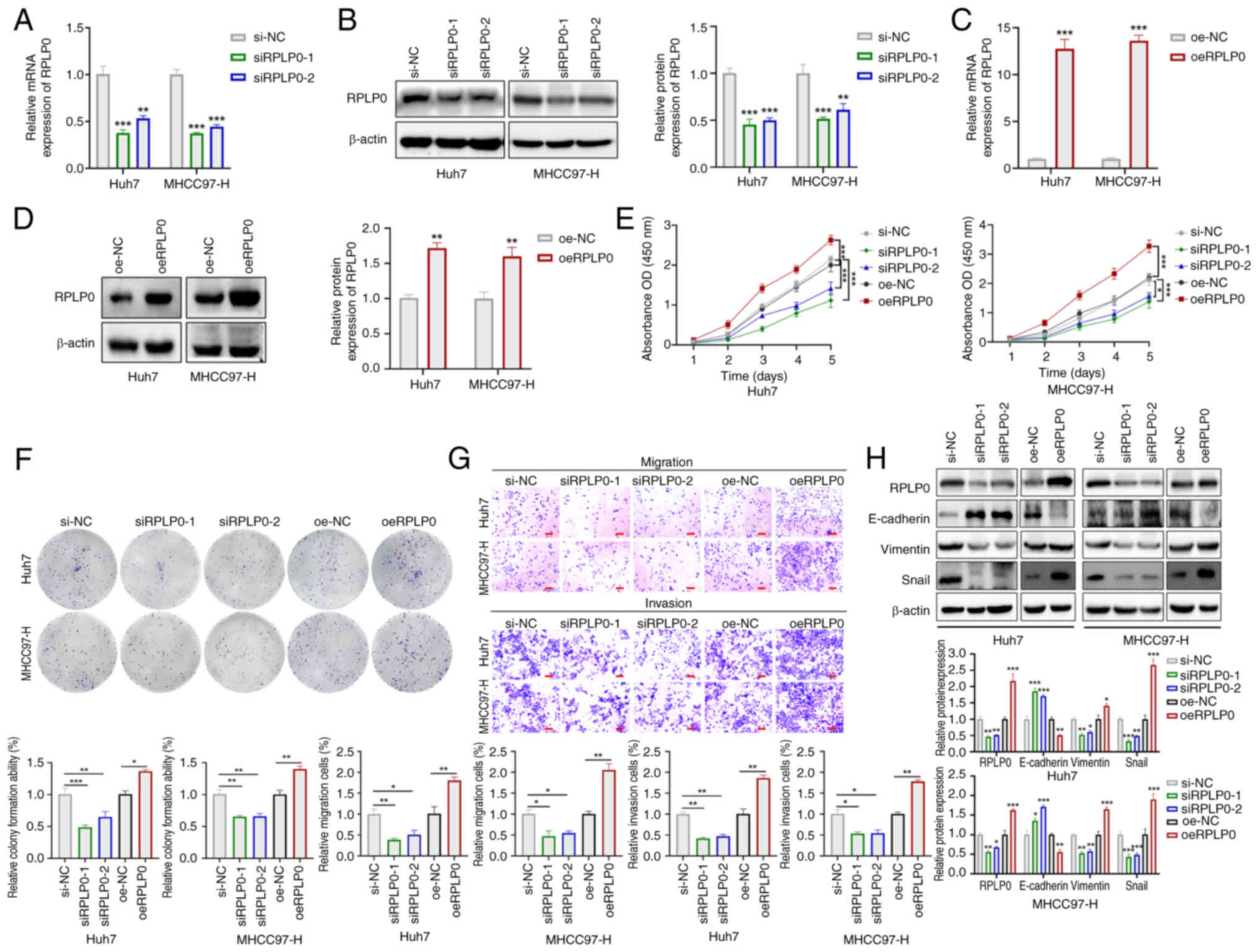

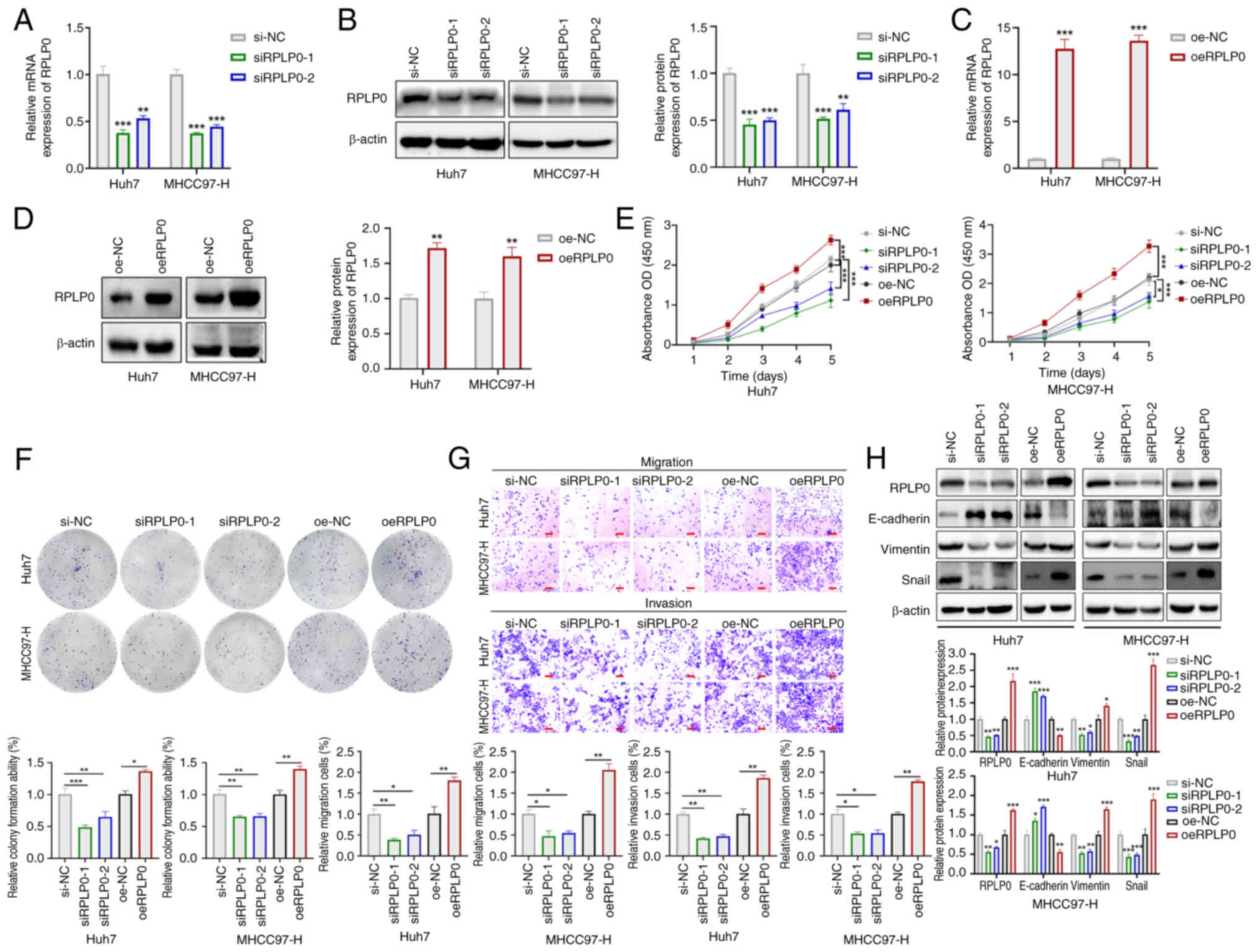

To further explore the biological function of RPLP0

in HCC, its expression was modulated in Huh7 and MHCC97-H cell

lines using siRPLP0 and oeRPLP0, respectively and their controls.

This caused changes in RPLP0 levels at both the mRNA and protein

(Fig. 2A-D) levels. The findings

obtained through the CCK-8, colony formation efficiency test and

Transwell assay showed that RPLP0 downregulation suppressed the

proliferative, invasive and migratory potentials of HCC cells. By

contrast, the upregulation of RPLP0 enhanced these cellular

properties in HCC cells (Fig.

2E-G). Western blot analysis indicated that the siRPLP0 group

exhibited markedly increased levels of E-cadherin in comparison to

the si-NC group, accompanied by notably decreased levels of

Vimentin and Snail. Conversely, the oeRPLP0 group demonstrated

markedly reduced levels of E-cadherin in comparison to the oe-NC

group, with concurrently elevated levels of Vimentin and Snail

(Fig. 2H). Flow cytometry

analysis indicated that downregulation of RPLP0 promoted apoptosis

and mediated G2/M cell cycle arrest, whereas

upregulation of RPLP0 inhibited apoptosis and promoted

G2/M cell cycle transition (Fig. 3A-B). Subsequently, the influence

of RPLP0 modulation on the expression patterns of proteins

implicated in apoptosis and cell cycle regulation was examined.

Western blot analysis showed that Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

(PARP), Bcl-2 and Cyclin D1 levels were markedly decreased in the

siRPLP0 group whereas cleaved (C-)PARP expression levels were

elevated. Conversely, the oeRPLP0 group displayed a marked

up-regulation in PARP, Bcl-2 and Cyclin D1 levels, accompanied by

the downregulation of C-PARP expression (Fig. 3C). These findings conjointly

indicate that the knockdown of RPLP0 delays malignant progression

in HCC cells.

| Figure 2RPLP0 overexpression promotes

malignant phenotypes in HCC cells. Alterations in mRNA and protein

levels following (A and B) RPLP0 knockdown and (C and D)

overexpression in HCC cells. (E) CCK-8, (F) colony formation and

(G) Transwell assays were conducted to assess HCC cell

proliferation, invasion and migration (scale bar, 150 μm).

(H) EMT-related protein expression changes (E-cadherin, Vimentin

and Snail) were observed in treated HCC cells.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. RPLP0, ribosomal protein lateral stalk

subunit P0; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CCK-8, cell counting

kit-8; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition. |

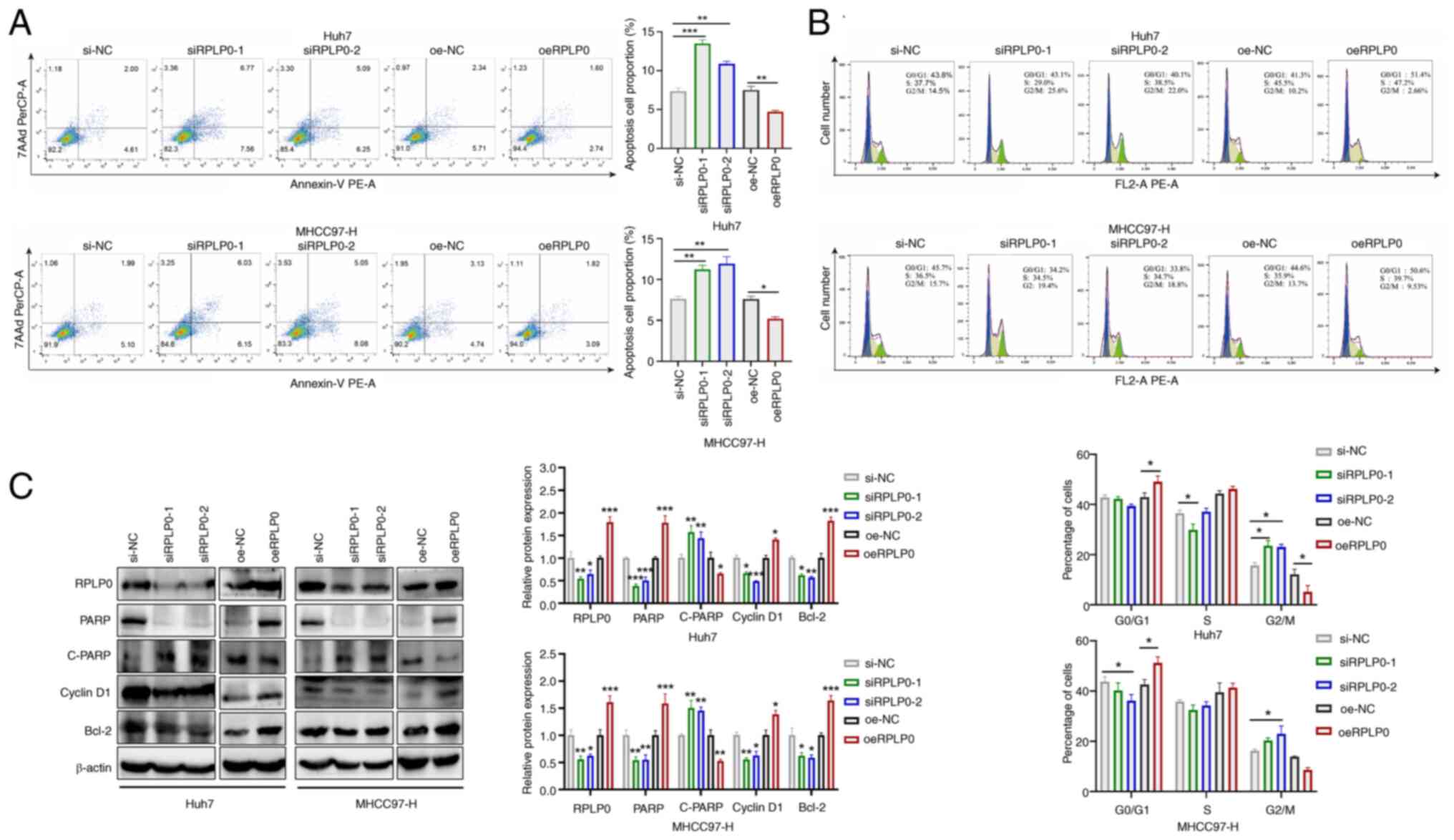

RPLP0 knockdown induces autophagy in

HCC

Autophagy is an intracellular regulatory mechanism

that preserves cellular homeostasis by eliminating superfluous or

dysfunctional cellular components and recycling metabolic

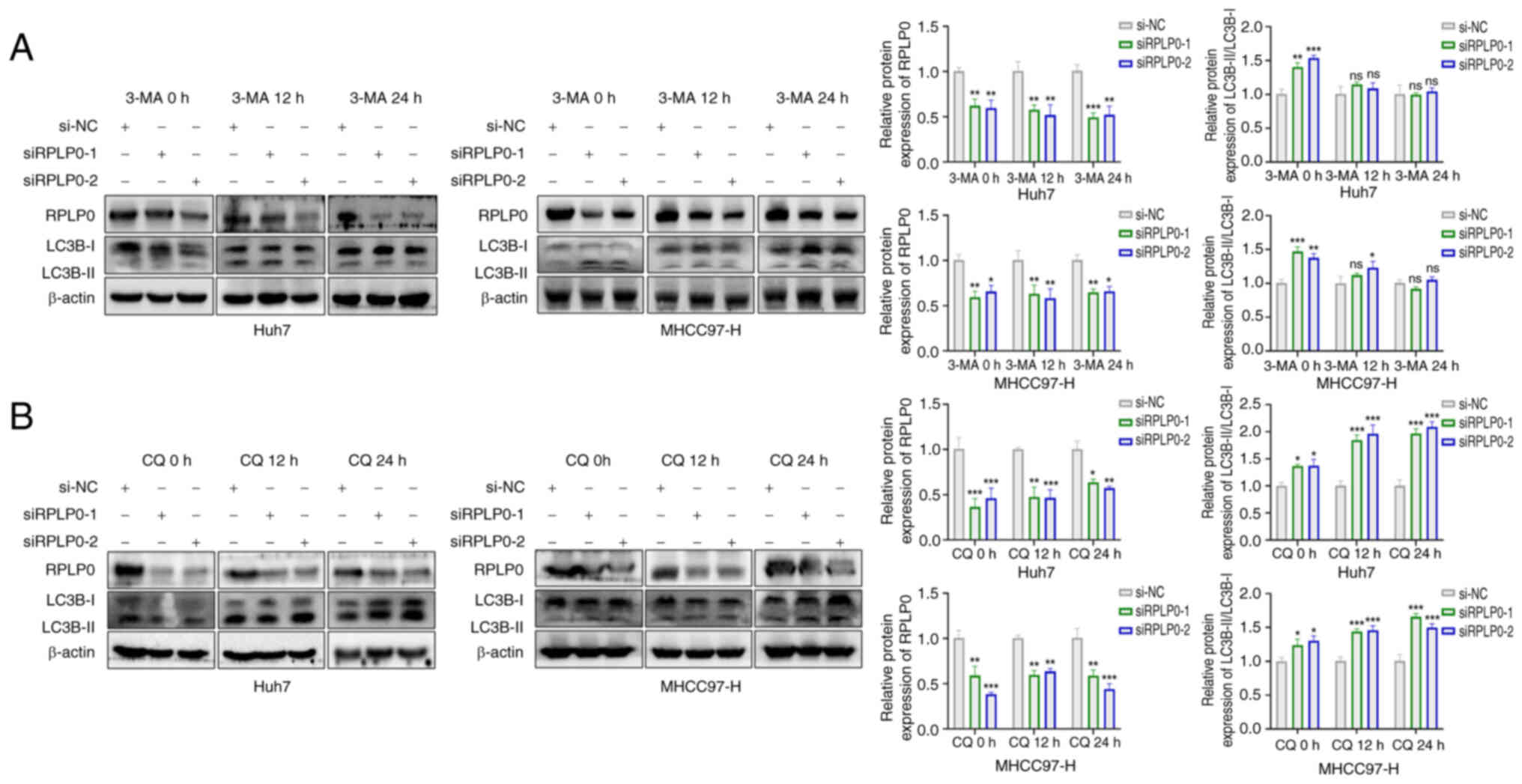

substrates (19,20). To assess the effect of RPLP0

expression on autophagy levels in HCC, GSEA was conducted,

revealing a statistically significant correlation between decreased

RPLP0 expression and the augmentation of autophagic processes

(Fig. 4A). Importantly, further

validation through western blot analysis demonstrated that the

suppression of RPLP0 resulted in a substantial elevation in the

LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio and a concurrent decrease in P62 levels

(Fig. 4B). Subsequently, the

presence of autophagosome vacuoles was evaluated employing MDC

staining and transmission electron microscopy. The analysis

unveiled that the downregulation of RPLP0 led to an increased

accumulation of autophagosome vacuoles in HCC cells (Fig. 4C and D). Autophagy was inhibited

by treating Huh7 and MHCC97-H cells that had been knocked down with

3-methyladenine (3-MA) (21). The

outcomes signaled that 3-MA reversed the elevation in the

LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio induced by RPLP0 downregulation, indicating

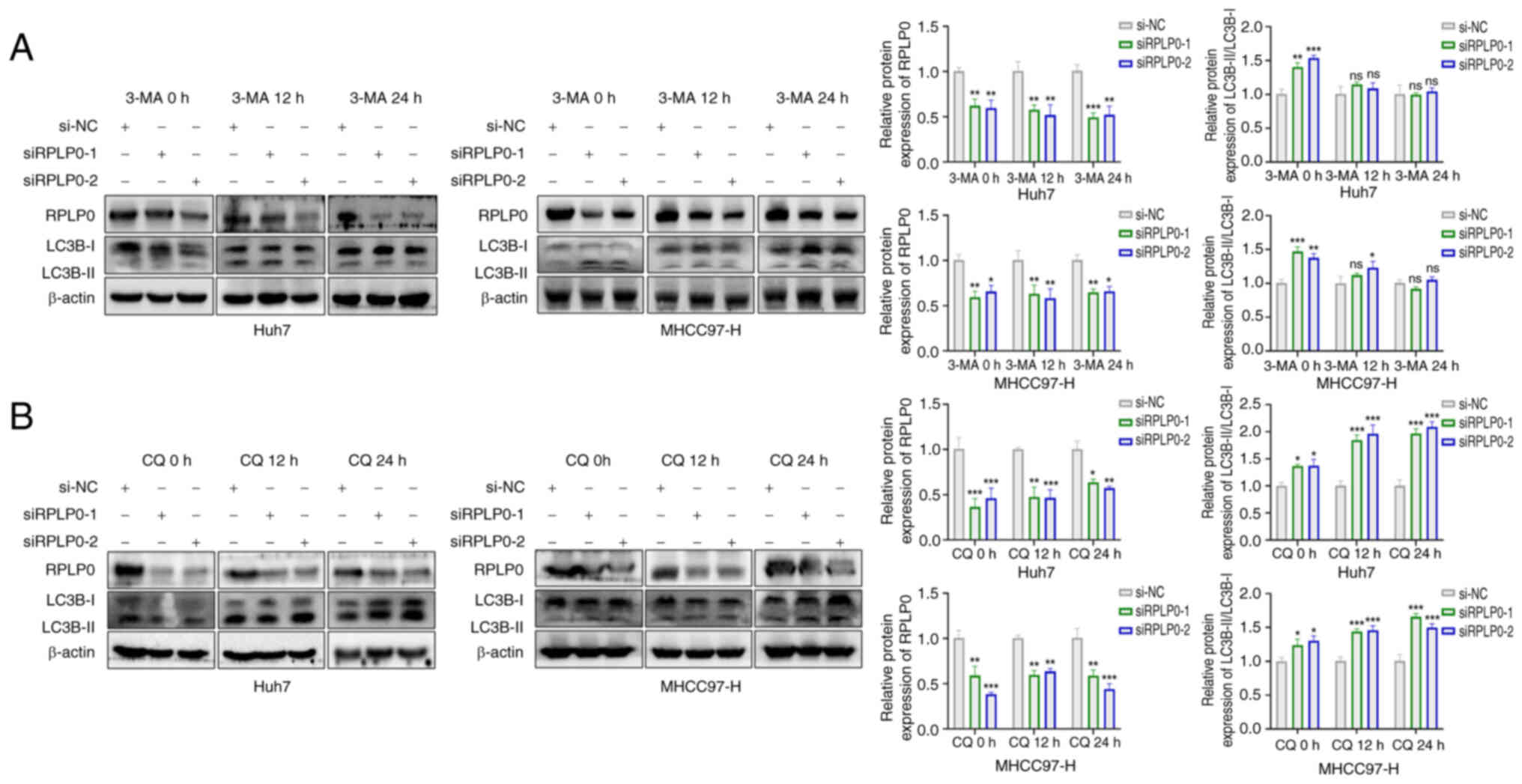

that RPLP0 knockdown indeed triggered autophagy (Fig. 5A). Given that the accumulation of

autophagosomes may signify either enhanced autophagic flux or

impaired autophagic processes (22), the effect of RPLP0 knockdown on

autophagic flux was investigated by the administration of

chloroquine (CQ), a known inhibitor of autophagy-lysosome fusion

(23). Treatment with CQ resulted

in an increase in the LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio at both 12 and 24 h,

suggesting that RPLP0 knockdown promoted autophagic flux (Fig. 5B). These findings unequivocally

demonstrate that the downregulation of RPLP0 induces autophagy in

HCC cells.

| Figure 5RPLP0 knockdown stimulates autophagic

flux in HCC cells, as shown by 3-MA and CQ. (A) Western blotting

analyzed LC3B expression in HCC cells pretreated with transfection

and subsequently exposed to 5 mM 3-MA for 0, 12 and 24 h. (B) HCC

cells were treated with 20 μM CQ for 0, 12 and 24 h,

respectively, followed by RPLP0 knockdown, and western blotting

evaluated LC3B levels. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. RPLP0, ribosomal

protein lateral stalk subunit P0; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma;

3-MA, 3-methyladenine; CQ, chloroquine. |

Suppression of RPLP0 expression impedes

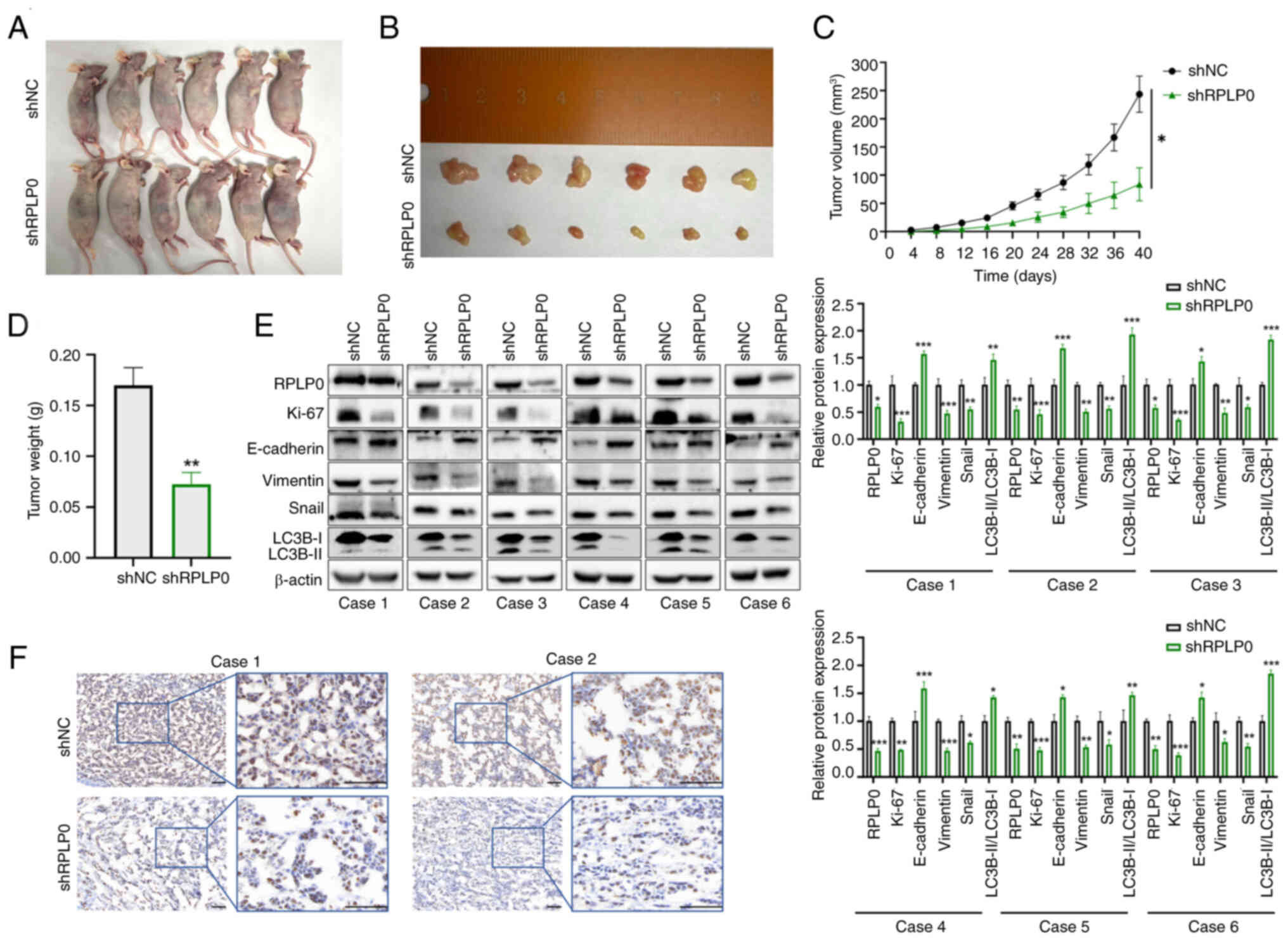

the progression of xenograft tumors

To explore the influence of RPLP0 knockdown on the

progression of subcutaneous xenograft tumors, MHCC97-H cells were

genetically modified using lentiviral vectors encoding either a

non-targeting control short hairpin RNA (shNC) or an RPLP0-targeted

short hairpin RNA (shRPLP0). Throughout the experimental period,

the tumor volumes were meticulously monitored and documented at

regular 4-day intervals. After 40 days, mouse xenograft models were

successfully established, xenograft tumors were successfully

isolated and tumor weights were statistically analyzed. The shRPLP0

group exhibited notably reduced tumor volumes and weights in

comparison to the shNC group (Fig.

6A-D). Western blotting of excised tumors indicated that the

shRPLP0 group demonstrated increased expression in E-cadherin and

the LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio relative to the shNC group. Meanwhile, the

expression levels of Ki-67, Vimentin and Snail were markedly

decreased in the shRPLP0 group (Fig.

6E). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis of the xenograft

tumors demonstrated lower Ki-67 expression levels in the shRPLP0

group (Fig. 6F).

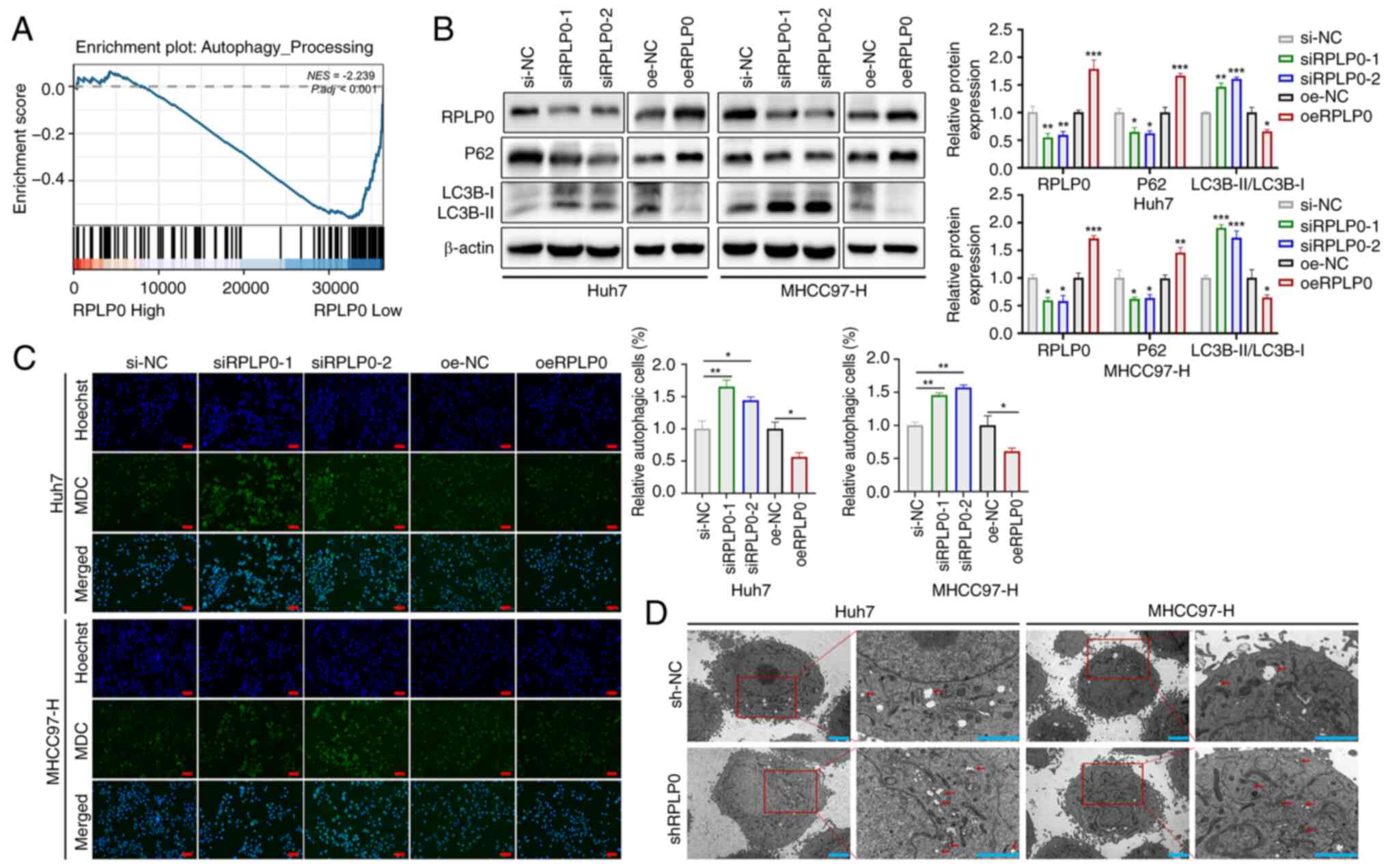

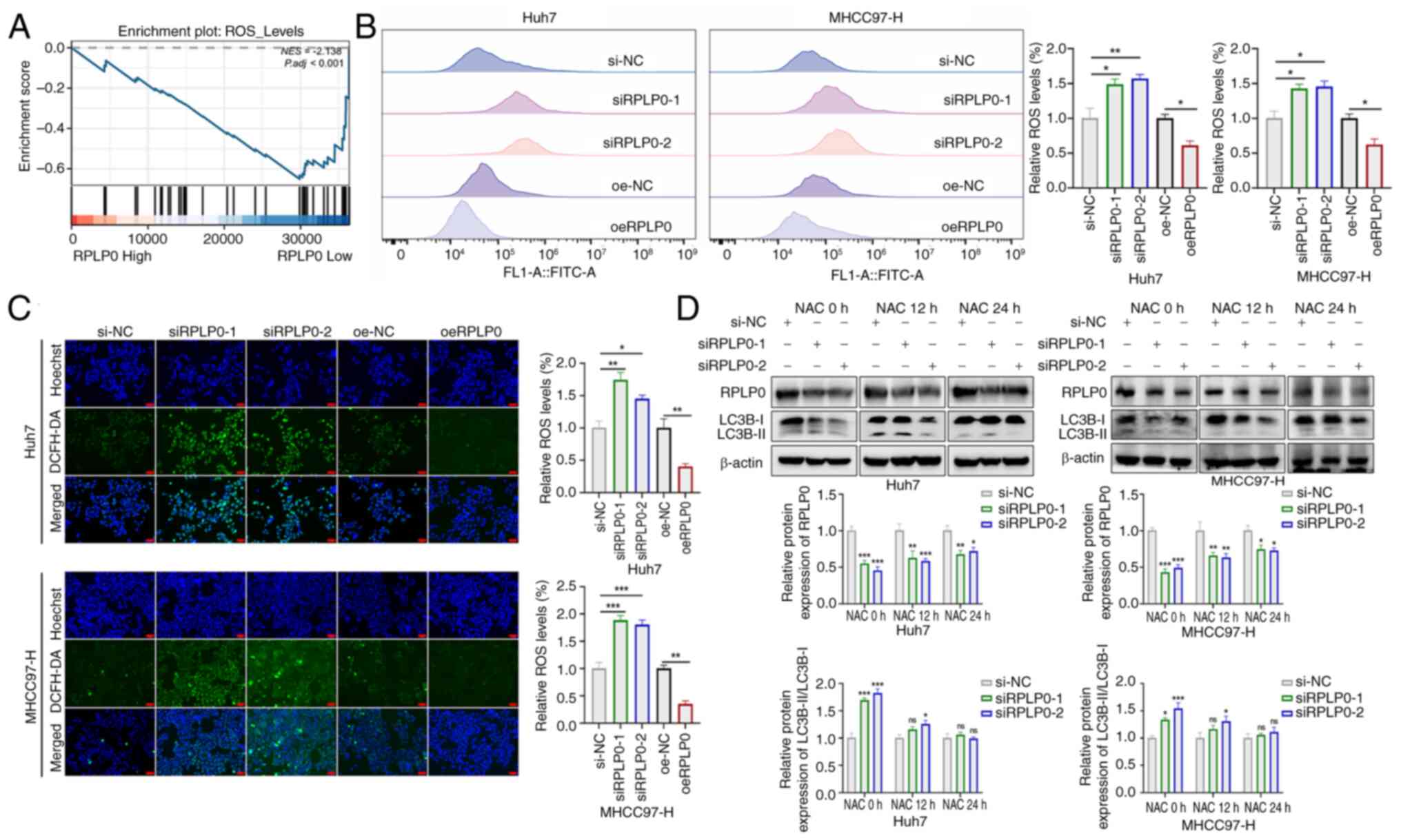

Suppression of RPLP0 inactivates the

JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway via ROS accumulation

Deficiency of the human ribosomal P complex in

breast cancer has been shown to result in significant dysregulation

of the TXN protein that neutralizes the effects of oxidative damage

(9,24). As previously documented, RPLP0

knockdown promoted autophagy (Fig.

4A-D), which is closely related to intracellular oxidative

stress (25,26). To explore the effect of RPLP0

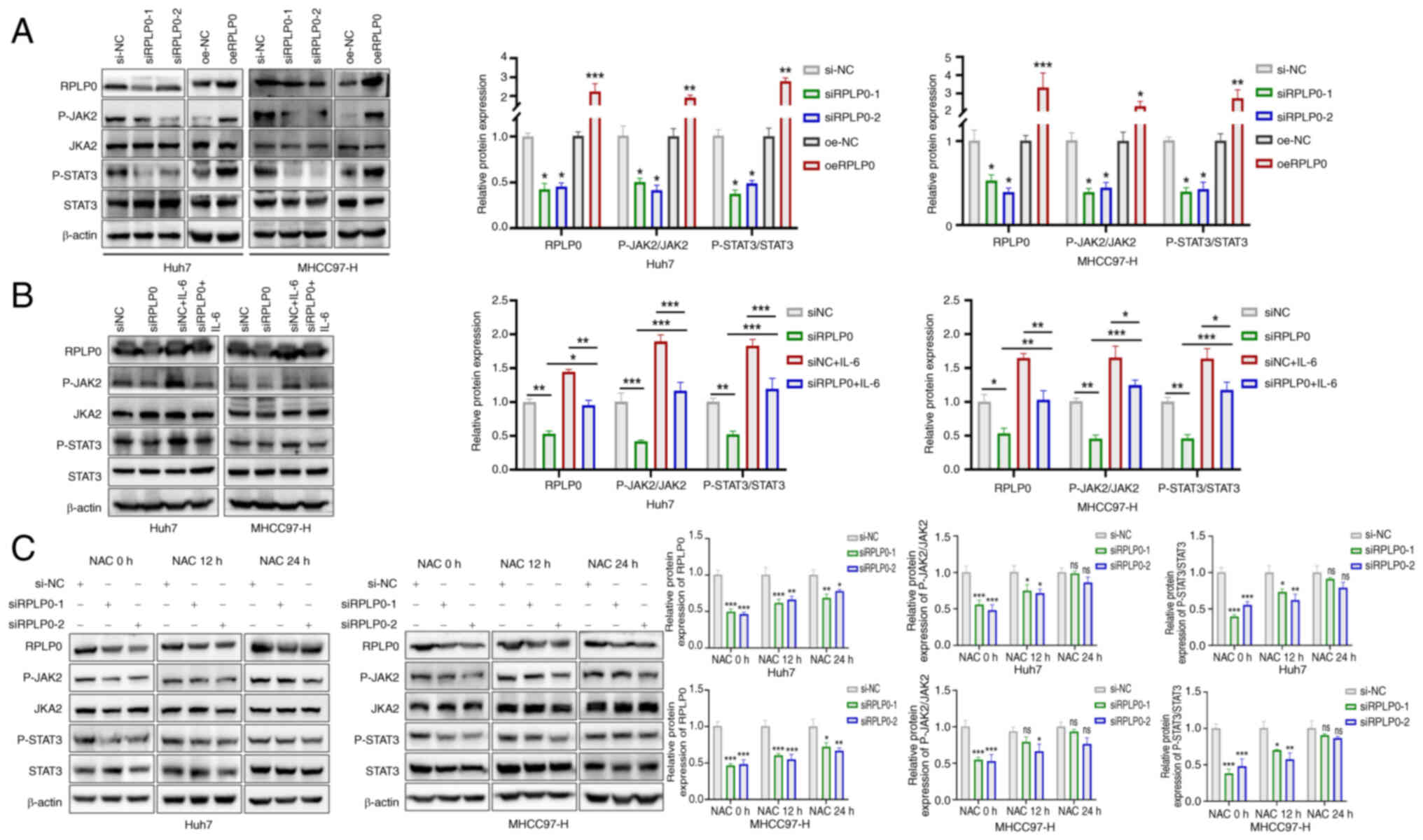

knockdown on ROS production, GSEA was performed. The findings

revealed significant enrichment of ROS accumulation in the

low-RPLP0 expression group (Fig.

7A). DCFH-DA staining can directly reflect ROS levels (27). Accordingly, DCFH-DA staining was

performed on transfected Huh7 and MHCC97-H cells and subsequent

flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy showed that RPLP0

knockdown markedly stimulated ROS production (Fig. 7B and C). To investigate the

relationship between ROS and autophagy, ROS levels were decreased

using N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) (28). As depicted in Fig. 7D, a marked reduction in the

LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio was observed following 12 and 24 h of NAC

treatment, suggesting that the progression of autophagy was

contingent upon ROS production. Moreover, the results showed that

RPLP0 knockdown inhibited JAK2/STAT3 pathway activation (Fig. 8A). IL-6 is well-documented as an

activator of the JAK/STAT3 pathway (29-31). Following a 48-h transfection

pretreatment in Huh7 and MHCC97-H cell lines, the administration of

40 ng/ml IL-6 for 24 h reverted alterations in RPLP0,

phosphorylated (p-) JAK2/JAK2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 expression,

implying that the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway is at least

partially dependent on RPLP0 (Fig.

8B). To further investigate the effects of RPLP0 knockdown on

ROS-mediated alterations in the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, NAC was

administered. The findings revealed that the levels of RPLP0,

p-JAK2/JAK2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 exhibited time-dependent increases at

12 and 24 h post-treatment, suggesting that RPLP0 knockdown induces

ROS accumulation, which mediates the inactivation of the JAK2/STAT3

pathway (Fig. 8C). Notably, the

mRNA levels of RPLP0 time-dependently increased following NAC

treatment (Fig. S1). In summary,

RPLP0 knockdown suppressed the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway by

promoting ROS accumulation, consequently delaying the progression

of HCC.

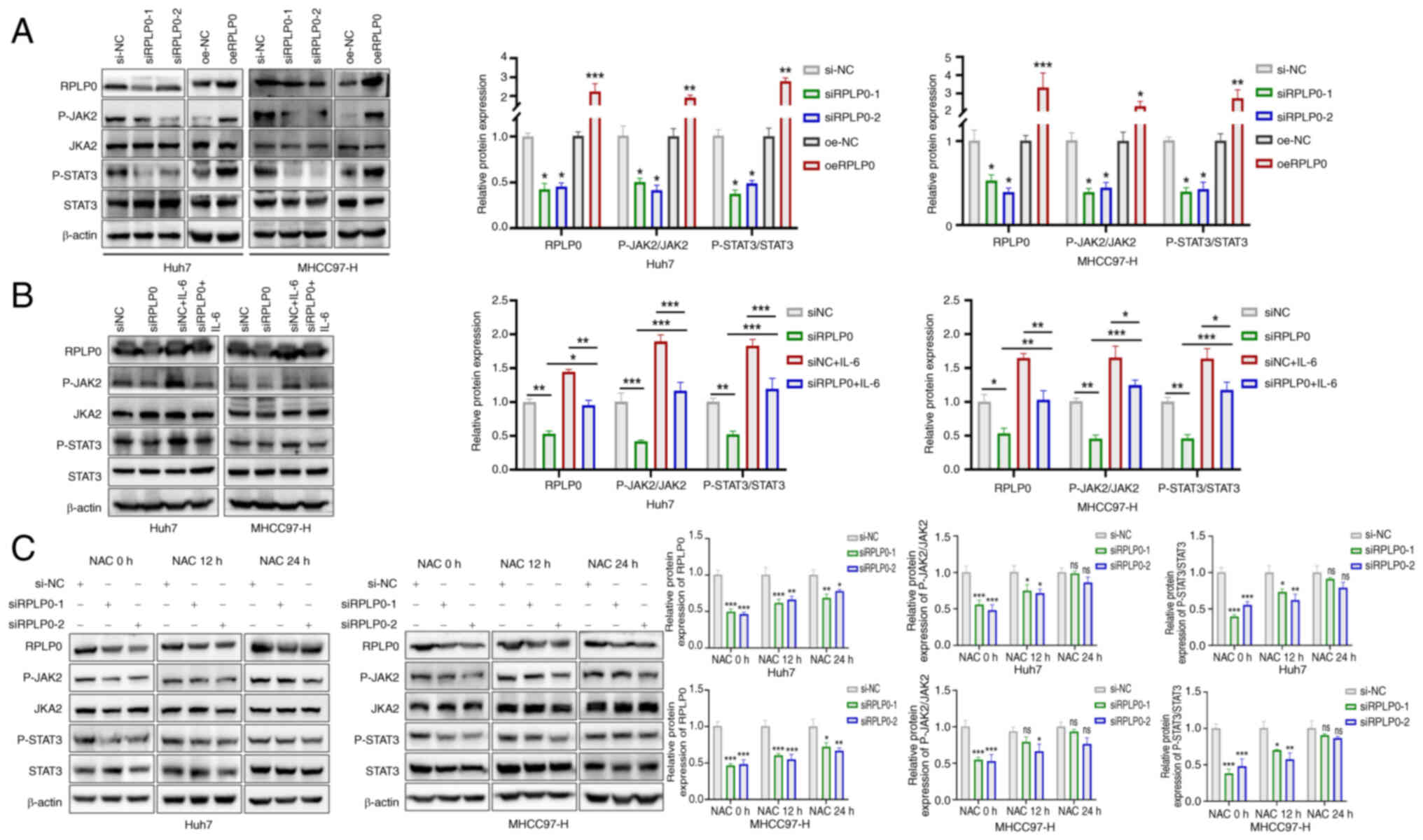

| Figure 8Suppressing RPLP0 deactivates the

JAK2/STAT3 pathway by accumulating ROS. (A) Alterations in RPLP0,

p-JAK2/JAK2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 expression were assessed in HCC cells

following transfection. (B) After 48 h of transfection, Huh7 and

MHCC97-H cells were exposed to 40 ng/ml IL-6 for an additional 24

h, followed by western blot analysis of RPLP0, p-JAK2/JAK2 and

p-STAT3/STAT3 expression. (C) HCC cells underwent a 48-h

transfection pretreatment and were then treated with 5 mM NAC for

0, 12 and 24 h, followed by western blot analysis of RPLP0,

p-JAK2/JAK2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 expression. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. RPLP0, ribosomal

protein lateral stalk subunit P0; ROS, reactive oxygen species; p-,

phosphorylated; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NAC,

N-acetyl-L-cysteine. |

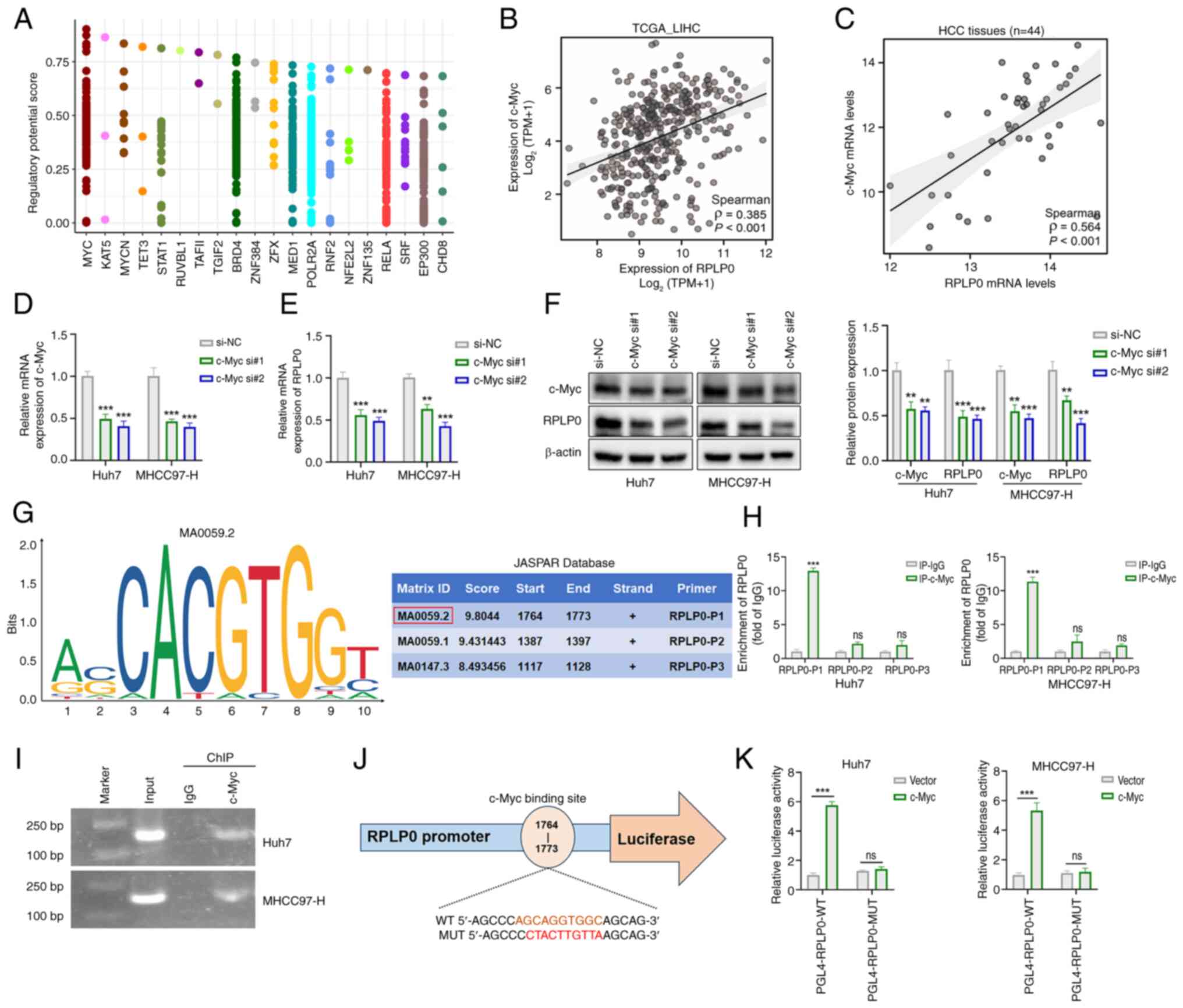

c-Myc activates RPLP0 transcription

To identify upstream regulators that activate RPLP0

transcription, predictions were made using the Cistrome Data

Browser. As depicted in Fig. 9A,

c-Myc had the highest relative score as a potential transcription

factor for RPLP0. Correlation analyses of TCGA data and 44 HCC

tissue samples demonstrated a statistically significant positive

association between c-Myc and RPLP0 expression levels (Fig. 9B and C). Furthermore, c-Myc

knockdown in HCC cells yielded a marked reduction in the mRNA and

protein levels of both c-Myc and RPLP0 (Fig. 9D-F). The DNA binding motifs for

c-Myc were retrieved from the JASPAR database and the corresponding

primers (RPLP0-P1/P2/P3) were designed by selecting different

binding sites with high relative scores (Fig. 9G). The direct interaction of c-Myc

with the RPLP0 promoter region was validated through ChIP-qPCR and

agarose gel electrophoresis of ChIP products (Fig. 9H and I). Moreover, luciferase

reporter vectors for RPLP0-WT and RPLP0-MUT were constructed,

incorporating specific c-Myc binding sites within the RPLP0

promoter sequence (Fig. 9J). The

dual luciferase reporter assay results indicated that c-Myc

enhanced the transcriptional activity of RPLP0-WT, whereas the

luciferase activity of RPLP0-MUT remained unaffected by c-Myc

(Fig. 9K). In summary, RPLP0

functioned as a direct target of c-Myc-mediated transcription.

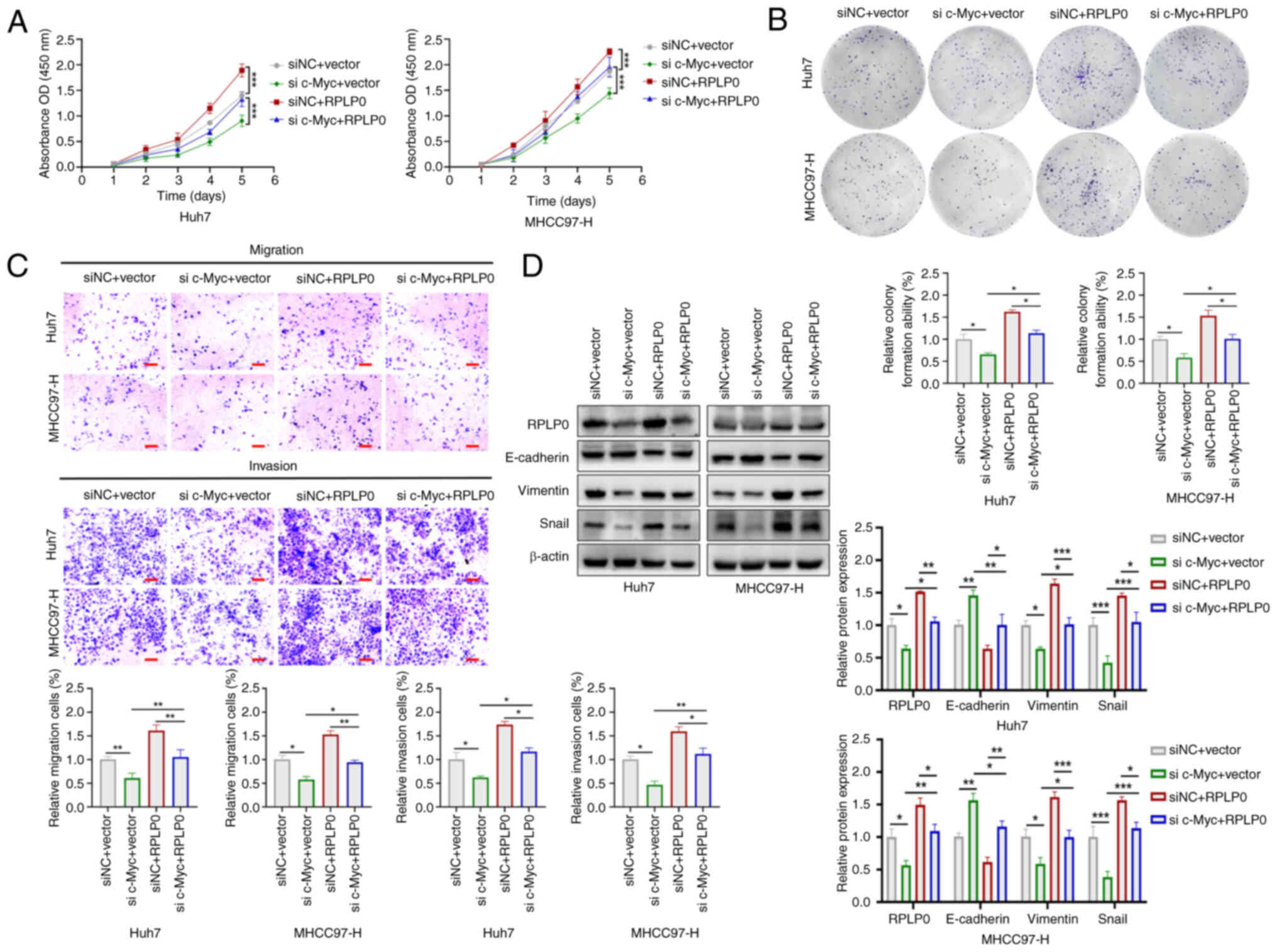

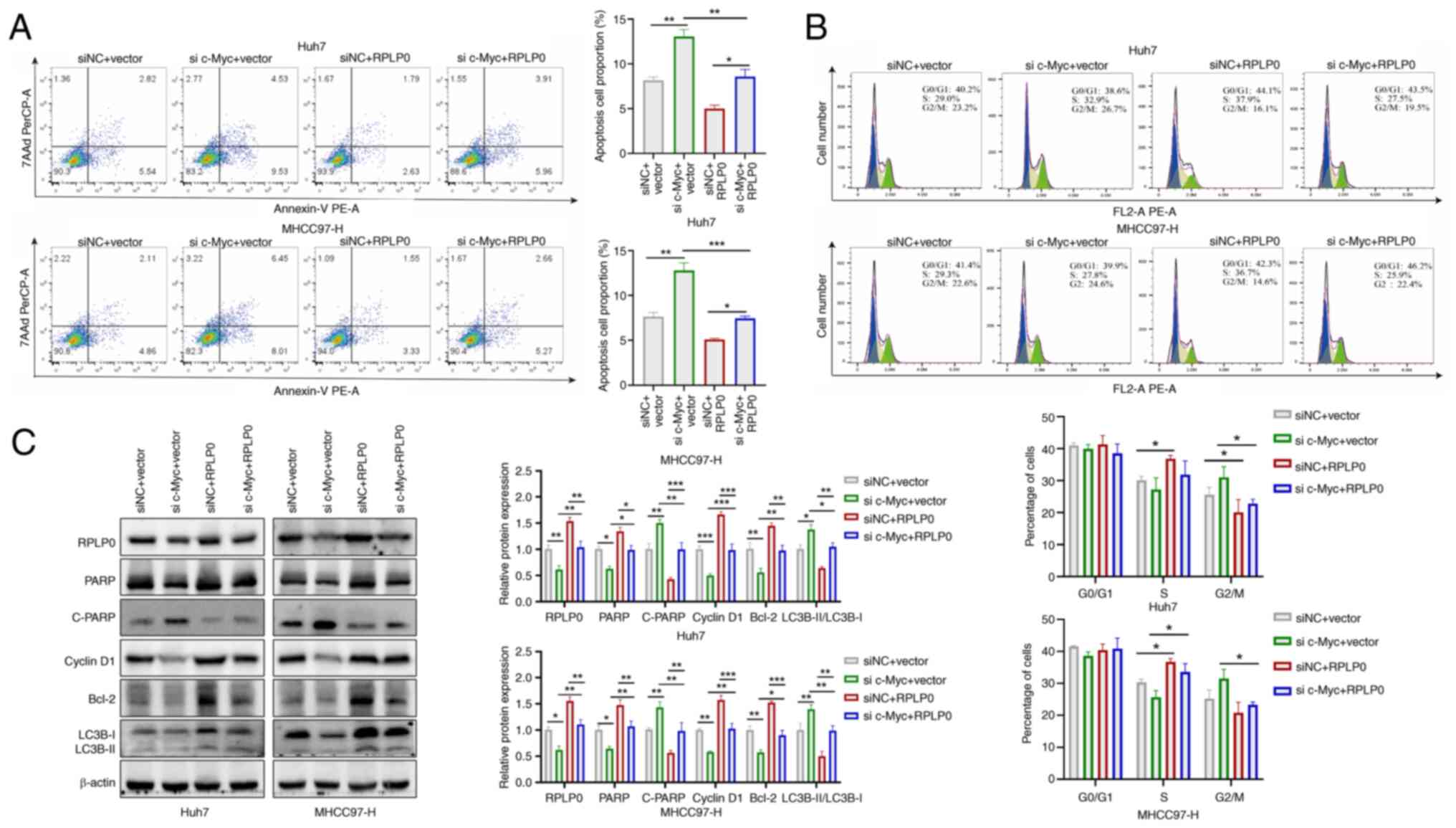

RPLP0 facilitates the malignant

progression of HCC through reliance on c-Myc regulation

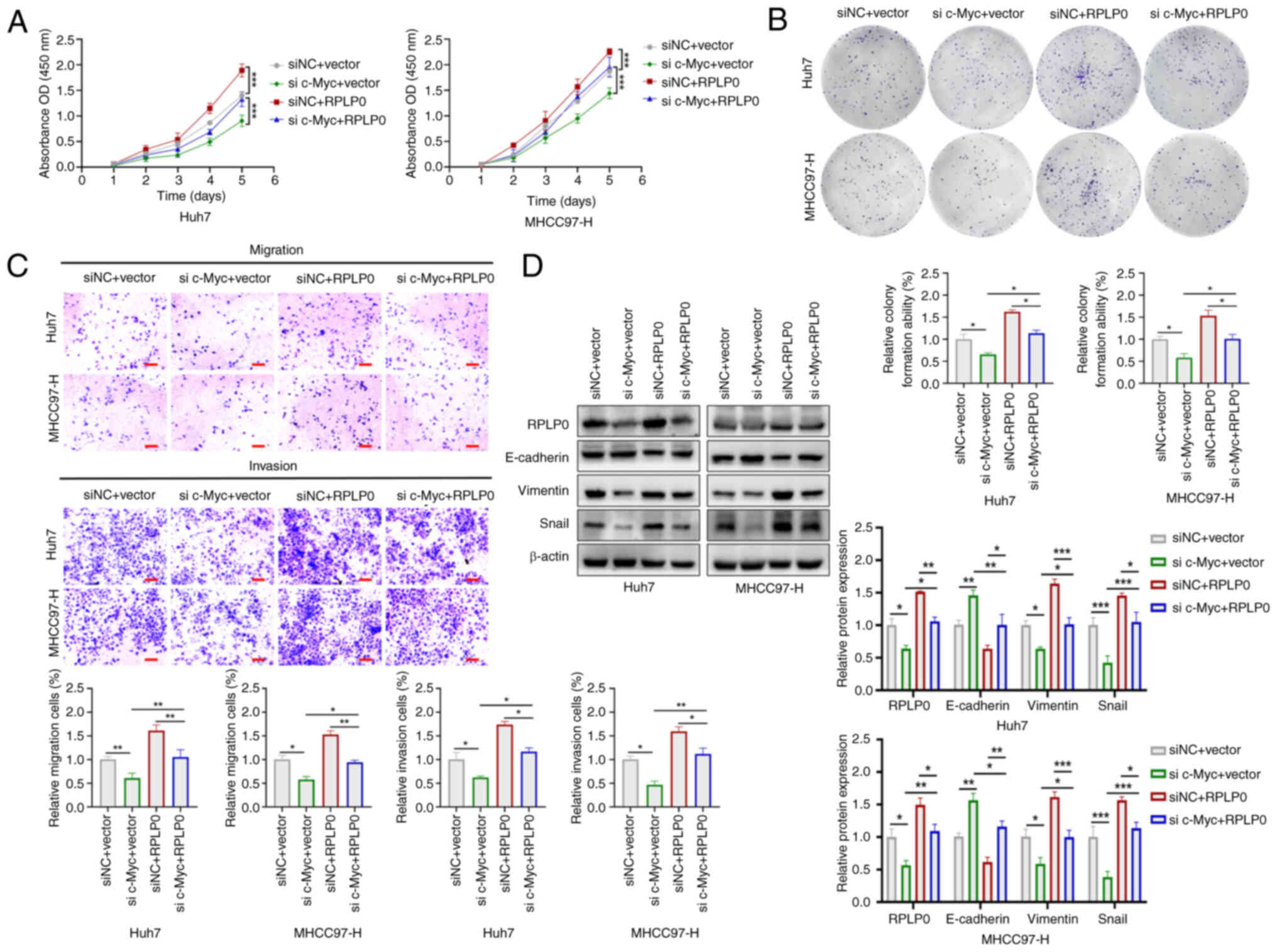

To investigate whether the involvement of RPLP0 in

advancing HCC development is contingent upon c-Myc regulation, Huh7

and MHCC97-H cell lines were used in co-transfection experiments.

Downregulation of c-Myc reversed the increases in HCC cell

proliferation, invasion and migration induced by RPLP0

overexpression (Fig. 10A-C).

Furthermore, RPLP0 overexpression restored the levels of Vimentin

and Snail while concomitantly downregulating E-cadherin expression

(Fig. 10D). Flow cytometry

analysis revealed that c-Myc knockdown effectively mitigated the

suppression of apoptosis and the G2/M cell cycle arrest

induced by RPLP0 overexpression (Fig. 11A and B). In addition, western

blot analysis revealed that downregulation of c-Myc partially

counteracted the influence of RPLP0 overexpression on the protein

levels of PARP, C-PARP, Cyclin D1 and Bcl-2, as well as the

LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio (Fig. 11C).

The present observations provide supporting evidence for the

involvement of RPLP0 in facilitating HCC progression, with

modulation of c-Myc serving as a key mechanism in this process.

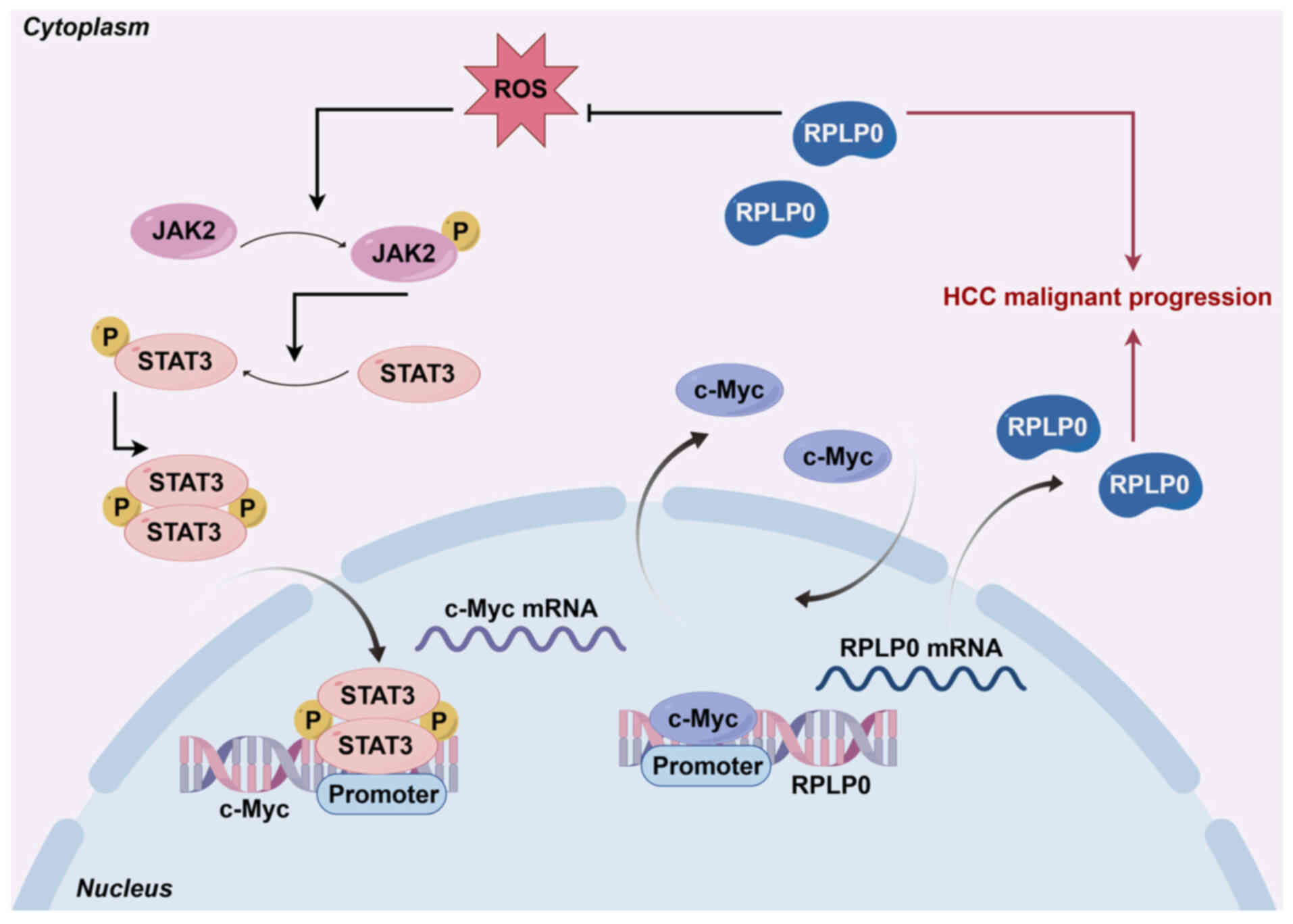

Collectively, these results indicate that RPLP0, regulated by

c-Myc, activates the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway by reducing ROS

levels, thereby facilitating the malignant progression of HCC

(Fig. 12).

| Figure 10RPLP0 facilitates the proliferation

and metastasis of HCC cells through the regulation of c-Myc. (A)

CCK-8, (B) colony formation and (C) Transwell assays were used to

assess cell proliferation, migration and invasion (scale bar, 150

μm). (D) EMT-related protein levels, such as E-cadherin,

Vimentin and Snail, were examined in co-transfected HCC cells.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. RPLP0, ribosomal protein lateral stalk

subunit P0; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; EMT,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. |

Discussion

Oncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene

inactivation are critical determinants in the malignant progression

of HCC (32,33). The aberrant activation of

pro-carcinogenic genes can drive the abnormal proliferation and

malignant transformation of hepatocytes (34,35). Consequently, a pressing

requirement exists to discover potential biological markers for

diagnostic and prognostic evaluation. The present study

comprehensively analyzed bioinformatics databases, diverse HCC cell

lines and tissue samples and concluded that elevated RPLP0 levels

in HCC are closely linked to unfavorable patient prognosis. These

findings indicated that RPLP0 may function as a tumorigenic factor

in HCC progression. A series of functional experiments on HCC cells

showed that downregulating RPLP0 expression substantially hindered

cellular proliferation, invasion and migration capabilities and

induced G2/M cell cycle arrest, along with the

triggering of apoptotic and autophagic processes. The results of

analogous xenograft tumor experiments indicated that the knockdown

of RPLP0 effectively suppressed tumor growth.

Cellular autophagy can be induced by a range of

factors, such as organelle damage, nutritional deficiencies and

oxidative stress (36). ROS

functions as highly reactive oxygenates and their excessive

production leads to cell cycle arrest and mitochondria-dependent

apoptosis (37). The present

investigation revealed that the reduction of RPLP0 expression

facilitated the accumulation of ROS, supported by the results of

both GSEA analysis and DCFH-DA staining. In addition, the results

indicated that RPLP0 knockdown inhibited JAK2/STAT3 pathway

activation. Subsequently, in-depth investigations revealed that the

supplementation of NAC, following the knockdown of RPLP0,

time-dependently increased RPLP0, p-JAK2/JAK2 and p-STAT3/STAT3

levels, suggesting that RPLP0 silencing mediates JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway inactivation by increasing ROS levels. Prior

investigations have identified a significant association between

elevated ROS concentrations and the suppression of the JAK2/STAT3

pathway, accompanied by increased autophagic activity (38-42). In the present study, RPLP0

knockdown resulted in increased ROS levels, which in turn repressed

JAK2/STAT3 pathway activation and stimulated autophagic processes,

consequently impeding the malignant progression of HCC.

Notably, both mRNA and protein levels of RPLP0

exhibited a time-dependent upregulation following the

administration of NAC at 12 and 24 h, suggesting that RPLP0 may be

regulated by transcription factors. Furthermore, the present study

demonstrated that NAC effectively counteracted the downregulation

in p-JAK2/JAK2 and p-STAT3/STAT3 expression induced by RPLP0

knockdown. Previous investigations have established that p-STAT3

possesses the ability to translocate into the nucleus, modulating

the transcription of various target genes, such as c-Myc, BCL-2,

Vimentin and MMP2/9, among others (43-45). It is worthwhile emphasizing that

the Cistrome Data Browser database was used to predict potential

transcription factors for RPLP0 and the results demonstrated that

c-Myc exhibited the highest relative score. An in-depth analysis of

data sourced from TCGA database, coupled with an examination of HCC

tissue samples, revealed a significant positive correlation between

the expression levels of RPLP0 and c-Myc. As a prevalent oncogene,

c-Myc facilitates the onset and progression of various tumors by

enhancing cellular growth and proliferation, modulating the

transcription of downstream target genes, inducing genomic

instability and reprogramming cellular metabolism (46-48). Subsequently, CHIP and dual

luciferase reporter assays revealed that c-Myc interacts with the

promoter sequence of RPLP0 to promote its transcription.

The present study demonstrated that RPLP0 knockdown

elevated intracellular ROS levels, thereby inducing autophagy.

However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which RPLP0 regulates

ROS generation remain unclear. Elucidating the upstream signals and

downstream effectors of RPLP0-mediated oxidative stress is a key

objective of our ongoing research.

In summary, the present study offered a new

perspective on the function of RPLP0 as a pro-oncogenic factor in

the progression of HCC. The results indicated that RPLP0 forms a

feedback loop with c-Myc via the ROS-mediated JAK2/STAT3 pathway.

Concurrently, c-Myc reciprocally activates RPLP0, thereby

perpetuating the circuit and contributing to the progression of

HCC. The findings of the present study provided innovative

perspectives on potential therapeutic approaches for the management

of HCC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

YQM and LBY conceived and designed the study. GRM,

HXH, and XBH performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data,

and wrote the manuscript. XPX and XDP supervised the entire

project. YQM and XDP confirm the authenticity of all raw data. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

approval no. (2024)CDYFYYLK (07-004) and all patients provided

informed consent. The animal experiments were also approved by the

animal ethics committee (approval no. CDYFY-IACUC-202407QR259).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude

to Professor Fanglin Zheng, Institute of Respiratory Diseases, The

First Affiliated Hospital, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang

University, for his invaluable advice.

Funding

The present study was supported by Jiangxi Kang-shen

Biotechnology Company (grant no. 1210702001), Wu Jieping Medical

Foundation (grant no. 320.6750.2024-13-32) and the Innovative and

Entrepreneurial Youth Talents Project of Jiangxi (grant no.

JXSQ2018106040).

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang X, Zhang L and Dong B: Molecular

mechanisms in MASLD/MASH-related HCC. Hepatology. 8:1303–1324.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Foerster F, Gairing SJ, Müller L and Galle

PR: NAFLD-driven HCC: Safety and efficacy of current and emerging

treatment options. J Hepatol. 76:446–457. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Toh MR, Wong EYT, Wong SH, Ng AWT, Loo LH,

Chow PK and Ngeow J: Global epidemiology and genetics of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 164:766–782. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Childs A, Aidoo-Micah G, Maini MK and

Meyer T: Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep.

6:1011302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Medavaram S and Zhang Y: Emerging

therapies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Hematol Oncol.

7:172018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Rimassa L, Pressiani T and Merle P:

Systemic treatment options in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver

Cancer. 8:427–446. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Artero-Castro A, Castellvi J, García A,

Hernández J, Ramón Y, Cajal S and Lleonart ME: Expression of the

ribosomal proteins Rplp0, Rplp1, and Rplp2 in gynecologic tumors.

Hum Pathol. 42:194–203. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Artero-Castro A, Perez-Alea M, Feliciano

A, Leal JA, Genestar M, Castellvi J, Peg V, Ramón Y, Cajal S and

Lleonart ME: Disruption of the ribosomal P complex leads to

stress-induced autophagy. Autophagy. 11:1499–1519. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Teller A, Jechorek D, Hartig R, Adolf D,

Reißig K, Roessner A and Franke S: Dysregulation of apoptotic

signaling pathways by interaction of RPLP0 and cathepsin X/Z in

gastric cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 211:62–70. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang CH, Wang LK, Wu CC, Chen ML, Lee MC,

Lin YY and Tsai FM: The ribosomal protein RPLP0 mediates

PLAAT4-induced cell cycle arrest and cell apoptosis. Cell Biochem

Biophys. 77:253–260. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang YL, Zhao WW, Bai SM, Ma Y, Yin XK,

Feng LL, Zeng GD, Wang F, Feng WX, Zheng J, et al: DNA

damage-induced paraspeckle formation enhances DNA repair and tumor

radioresistance by recruiting ribosomal protein P0. Cell Death Dis.

13:7092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Miller DR and Thorburn A: Autophagy and

organelle homeostasis in cancer. Dev Cell. 56:906–918. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Meng Y, Huang X, Zhang G, Fu S, Li Y, Song

J, Zhu Y, Xu X and Peng X: MicroRNA-450b-5p modulated RPLP0

promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via activating

JAK/STAT3 pathway. Transl Oncol. 50:1021502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zheng P, Xu D, Cai Y, Zhu L, Xiao Q, Peng

W and Chen B: A multi-omic analysis reveals that Gamabufotalin

exerts anti-hepatocellular carcinoma effects by regulating amino

acid metabolism through targeting STAMBPL1. Phytomedicine.

135:1560942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Qian J, Wang Q, Xiao L, Xiong W, Xian M,

Su P, Yang M, Zhang C, Li Y, Zhong L, et al: Development of

therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against DKK1 peptide-HLA-A2

complex to treat human cancers. J Immunother Cancer.

12:e0081452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mizushima N and Levine B: Autophagy in

human diseases. N Engl J Med. 383:1564–1576. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yan LS, Zhang SF, Luo G, Cheng BC, Zhang

C, Wang YW, Qiu XY, Zhou XH, Wang QG, Song XL, et al: Schisandrin B

mitigates hepatic steatosis and promotes fatty acid oxidation by

inducing autophagy through AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. Metabolism.

131:1552002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhao YG, Codogno P and Zhang H: Machinery,

regulation and pathophysiological implications of autophagosome

maturation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:733–750. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Miao CC, Hwang W, Chu LY, Yang LH, Ha CT,

Chen PY, Kuo MH, Lin SC, Yang YY, Chuang SE, et al: LC3A-mediated

autophagy regulates lung cancer cell plasticity. Autophagy.

18:921–934. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Bradford HF, McDonnell TCR, Stewart A,

Skelton A, Ng J, Baig Z, Fraternali F, Dunn-Walters D, Isenberg DA,

Khan AR, et al: Thioredoxin is a metabolic rheostat controlling

regulatory B cells. Nat Immunol. 25:873–885. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ornatowski W, Lu Q, Yegambaram M, Garcia

AE, Zemskov EA, Maltepe E, Fineman JR, Wang T and Black SM: Complex

interplay between autophagy and oxidative stress in the development

of pulmonary disease. Redox Biol. 36:1016792020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Russell RC and Guan KL: The multifaceted

role of autophagy in cancer. EMBO J. 41:e1100312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yang R, Gao W, Wang Z, Jian H, Peng L, Yu

X, Xue P, Peng W, Li K and Zeng P: Polyphyllin I induced

ferroptosis to suppress the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma

through activation of the mitochondrial dysfunction via

Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 axis. Phytomedicine. 122:1551352024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tsai HY, Bronner MP, March JK, Valentine

JF, Shroyer NF, Lai LA, Brentnall TA, Pan S and Chen R: Metabolic

targeting of NRF2 potentiates the efficacy of the TRAP1 inhibitor

G-TPP through reduction of ROS detoxification in colorectal cancer.

Cancer Lett. 549:2159152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Johnson DE, O'Keefe RA and Grandis JR:

Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 15:234–248. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lai SY and Johnson FM: Defining the role

of the JAK-STAT pathway in head and neck and thoracic malignancies:

Implications for future therapeutic approaches. Drug Resist Updat.

13:67–78. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R and

Jove R: Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected

biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. 14:736–746. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen L, Zhang C, Xue R, Liu M, Bai J, Bao

J, Wang Y, Jiang N, Li Z, Wang W, et al: Deep whole-genome analysis

of 494 hepatocellular carcinomas. Nature. 627:586–593. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ng CKY, Dazert E, Boldanova T,

Coto-Llerena M, Nuciforo S, Ercan C, Suslov A, Meier MA, Bock T,

Schmidt A, et al: Integrative proteogenomic characterization of

hepatocellular carcinoma across etiologies and stages. Nat Commu.

13:24362022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Calderaro J, Ziol M, Paradis V and

Zucman-Rossi J: Molecular and histological correlations in liver

cancer. J Hepatol. 71:616–630. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Villanueva A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 380:1450–1462. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li X, He S and Ma B: Autophagy and

autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Fan J, Ren D, Wang J, Liu X, Zhang H, Wu M

and Yang G: Bruceine D induces lung cancer cell apoptosis and

autophagy via the ROS/MAPK signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo.

Cell Death Dis. 11:1262020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cao Y, Wang J, Tian H and Fu GH:

Mitochondrial ROS accumulation inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 pathway is a

critical modulator of CYT997-induced autophagy and apoptosis in

gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:1192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kim J, Park A, Hwang J, Zhao X, Kwak J,

Kim HW, Ku M, Yang J, Kim TI, Jeong KS, et al: KS10076, a chelator

for redox-active metal ions, induces ROS-mediated STAT3 degradation

in autophagic cell death and eliminates ALDH1+ stem cells. Cell

Rep. 40:1110772022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Liang JR and Yang H: Ginkgolic acid (GA)

suppresses gastric cancer growth by inducing apoptosis and

suppressing STAT3/JAK2 signaling regulated by ROS. Biomed

Pharmacother. 125:1095852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhao Z, Wang Y, Gong Y, Wang X, Zhang L,

Zhao H, Li J, Zhu J, Huang X, Zhao C, et al: Celastrol elicits

antitumor effects by inhibiting the STAT3 pathway through ROS

accumulation in non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med.

20:5252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhou H, Li J, He Y, Xia X, Liu J and Xiong

H: SLC25A17 inhibits autophagy to promote triple-negative breast

cancer tumorigenesis by ROS-mediated JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway.

Cancer Cell Int. 24:852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Garg M, Shanmugam MK, Bhardwaj V, Goel A,

Gupta R, Sharma A, Baligar P, Kumar AP, Goh BC, Wang L and Sethi G:

The pleiotropic role of transcription factor STAT3 in oncogenesis

and its targeting through natural products for cancer prevention

and therapy. Med Res Rev. December 1–2020.Epub ahead of print.

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hu Y, Dong Z and Liu K: Unraveling the

complexity of STAT3 in cancer: Molecular understanding and drug

discovery. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zou S, Tong Q, Liu B, Huang W, Tian Y and

Fu X: Targeting STAT3 in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer.

19:1452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Dhanasekaran R, Deutzmann A,

Mahauad-Fernandez WD, Hansen AS, Gouw AM and Felsher DW: The MYC

oncogene-the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune

evasion. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:23–36. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Duffy MJ, O'Grady S, Tang M and Crown J:

MYC as a target for cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev.

94:1021542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lourenco C, Resetca D, Redel C, Lin P,

MacDonald AS, Ciaccio R, Kenney TMG, Wei Y, Andrews DW, Sunnerhagen

M, et al: MYC protein interactors in gene transcription and cancer.

Nat Rev Cancer. 21:579–591. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|