Introduction

Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is a neoplastic growth

that originates in the urinary tract lining and extends from the

renal pelvis to the urethra. It encompasses a range of histological

subtypes and anatomical locations, including upper tract UC (UTUC)

and primary urethral cancer (1).

UTUC accounts for 5-10% of UC cases, whereas primary urethral

cancer is even rarer (2). In the

United States, it is estimated that there were 87,840 new cases of

bladder cancer and 17,840 deaths in 2024, making it the fifth most

common cancer in men and the fourteenth in women. The incidence

rates of bladder cancer in the US are ~82.3 per 100,000 in men and

21.3 per 100,000 in women (3). In

Europe, bladder cancer ranks as the tenth most common cancer, with

~226,000 new cases and 69,000 deaths annually. The incidence rates

vary across European countries, with higher rates observed in

southern and eastern Europe (3).

In Asia, the incidence of UC is lower than that in Western

countries, but it still poses a significant health burden,

especially in rapidly industrializing regions. For instance, in

China, the incidence of bladder cancer is ~13.5 per 100,000, with

higher rates in urban areas (3).

However, bladder cancer remains a notable health issue in some

regions, with incidence rates influenced by factors such as

schistosomiasis infection. Globally, the aggressive nature and high

recurrence rate of UC make it a challenging disease to manage

globally.

Advanced UC, particularly in metastatic or

cisplatin-ineligible patients, is associated with poor prognosis

(4). The 5-year survival rate for

patients with advanced UC is ~10%, highlighting an urgent need for

more effective treatment strategies (5). Traditional treatment methods, such

as platinum-based chemotherapy, have limitations related to

achieving durable responses. For patients with advanced UC being

treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, the median OS is

typically less than 15 months (6). While the use of immune checkpoint

inhibitors (ICIs) has shown promise, their efficacy varies, and

numerous patients eventually develop resistance (7). A meta-analysis of 11 trials

including 1,630 previously treated patients with UC revealed that

the pooled objective response rate (ORR) for single targeted agents

was 10.7% (95% CI: 10.7-19.6%), the disease control rate was 33.2%

(95% CI: 25-41.4%), and the 1-year OS was 31% (95% CI: 23.6-39.4%)

(8). These findings underscore

the critical need for novel approaches to improve patient outcomes

in this patient population.

Over the past decade, the treatment landscape for UC

has evolved significantly with the advent of targeted therapies.

Erdafitinib, a fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor,

and enfortumab vedotin (EV), an antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)

targeting Nectin-4, have demonstrated significant efficacy for the

treatment of UC. Erdafitinib achieved a 40% ORR in a phase II trial

for patients with FGFR2/3-altered UC (9). EV showed a robust ORR of 43% in a

phase I trial, even in patients whose cancer had previously

progressed on ICIs (10). These

advancements mark a significant shift from traditional chemotherapy

and underscore the importance of molecularly guided therapies in

improving the prognosis of patients with UC. Ongoing research

continues to explore the optimal sequencing of these therapies and

the development of next-generation agents to further improve

treatment outcomes.

Unlike prior reviews that have separately summarized

FGFR inhibitors or ADCs, the present article integrates real-world

evidence, biomarker analytics, and resistance biology into a single

comparative framework. Recent literature gaps include insufficient

head-to-head evaluation of FGFR inhibitors vs. ADCs sequences,

limited dissection of convergent resistance pathways (for example,

PI3K/AKT re-activation and TGF-β-mediated immune exclusion), and

absence of a unified roadmap guiding biomarker-driven combination

therapy. By synthesizing 2023-2025 trial data with spatial

transcriptomic and urinary circulating-tumor-DNA studies, the

present review offers a dynamic, systems-level perspective that

links genomic alteration, tumor microenvironment (TME) phenotype,

and clinical outcomes; such integration has not been previously

accomplished in UC-focused commentaries. Consequently, the

manuscript provides clinicians and translational researchers with

an evidence-based hierarchy for selecting FGFR or ADCs-based

regimens, forecasts emerging resistance mechanisms, and proposes

biomarker-adaptive trial designs to accelerate precision medicine

implementation.

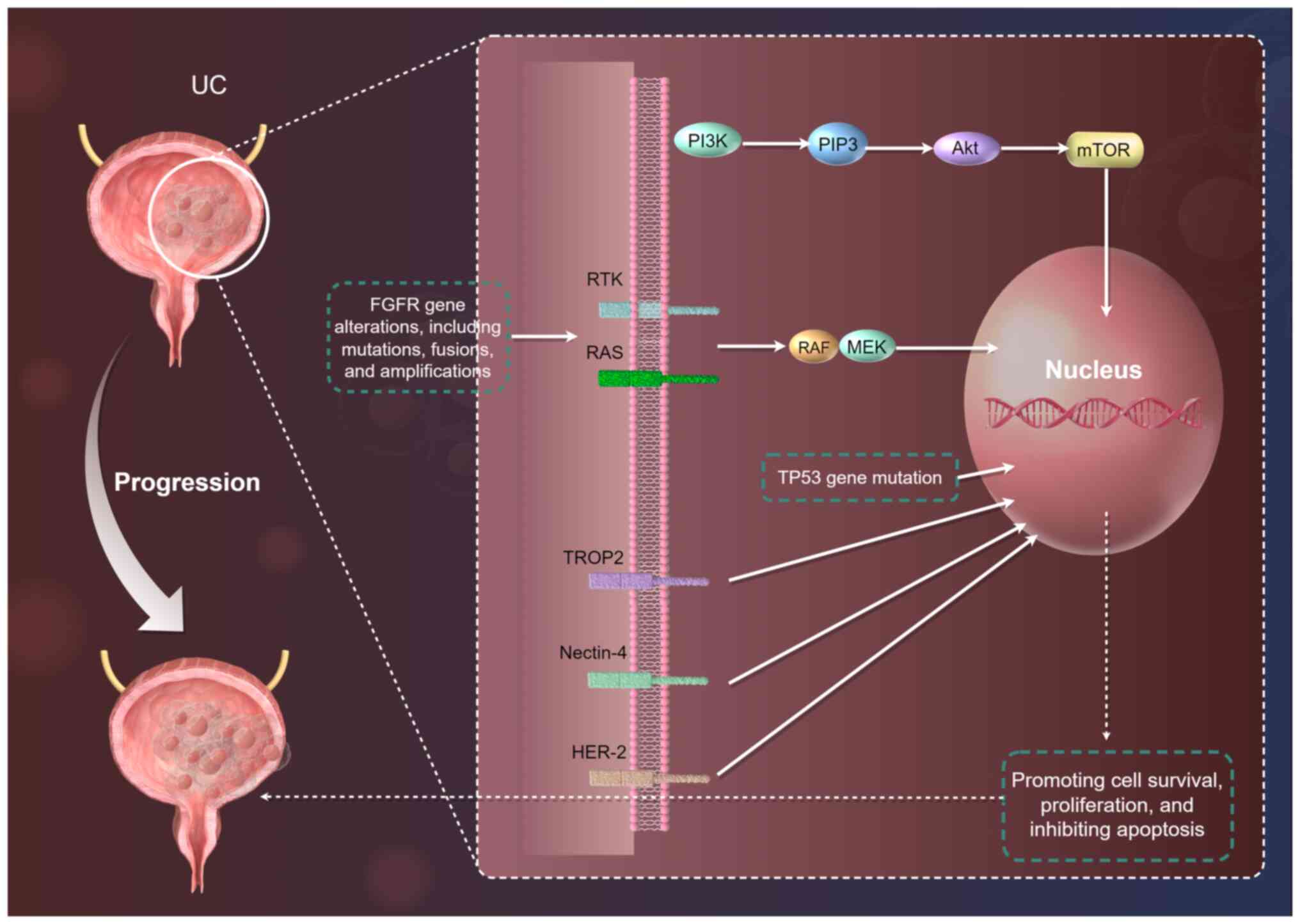

Molecular biology of UC

In recent years, with advancements in genomics and

molecular biology technologies, the molecular landscape of UC has

been gradually unveiled. Various molecular alterations and

signaling pathways interact synergistically, driving tumor

development and progression (11). A deeper understanding of the

molecular biology of UC provides a strong foundation for the

development of targeted therapies. By identifying key molecular

targets and pathways (Fig. 1),

researchers can develop more effective therapeutic strategies to

improve treatment outcomes and survival rates for patients with UC

(12).

Key molecular pathways

UC development and progression involve complex

molecular mechanisms. Among them, the Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

(PI3K)/Protein Kinase B(AKT)/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)

pathway plays a significant role (13). This pathway is frequently

activated due to mutations in genes such as PIK3CA, PTEN deletion,

or AKT1 mutation (14). PI3K

catalyzes the production of PIP3, which activates AKT. Activated

AKT, in turn, phosphorylates mTOR, promoting cell survival,

proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis (14). Studies have shown that PIK3CA

mutations are present in ~24-40% of UC cases (15). PTEN deletion occurs in ~17-30% of

cases (16). Activation of this

pathway contributes to UC progression and chemoresistance. For

example, in a particular study, PTEN-deficient mice were more prone

to developing UC and displayed more aggressive tumor

characteristics, such as increased proliferation rates and higher

metastatic potential (17).

The Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK)/Rat Sarcoma

(RAS)/V-Raf Murine Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog

(RAF)/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase (MEK)/Extracellular

Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) pathway is another critical signaling

pathway (18). Abnormal

activation of this pathway can be caused by mutations in FGFR, RAS,

or BRAF genes. FGFR gene alterations, including mutations, fusions

and amplifications, can lead to ligand-independent receptor

activation, subsequently activating downstream signaling pathways

(19). RAS mutations are found in

~15-30% of UC cases, and BRAF mutations occur in ~5-10% of cases

(20). Activation of this pathway

promotes cell proliferation, differentiation and angiogenesis. For

example, a study by Zhou et al (21) demonstrated that mutations in this

pathway are associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in

patient with UC.

The Tumor Protein 53 (TP53) gene mutation pathway is

also crucial in UC. TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene, and its

encoded protein plays a pivotal role in cell cycle regulation, DNA

repair and apoptosis (22). TP53

mutations are detected in ~40-50% of UC cases. Mutations in this

gene lead to loss of its normal function, enabling cells with DNA

damage to continue proliferating, thereby promoting tumor

development and progression (22). Ecke et al (23) revealed that TP53 mutations are

associated with higher tumor grade and stage in UC and are linked

to poor patient prognosis.

FGFR alterations

FGFR gene alterations are prevalent in UC. FGFR

family includes FGFR1-4. Among them, FGFR3 alterations are the most

common in UC, occurring in ~10-30% of cases (24). FGFR3 gene mutations primarily

involve point mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain, such as

R248C, S249C and Y373C mutations, which lead to receptor

constitutive activation (25).

FGFR3 gene fusions, such as FGFR3-TACC3 fusions, can also result in

abnormal receptor activation. FGFR gene amplifications can increase

receptor expression levels, thereby enhancing downstream signaling

pathway activation (26). These

alterations contribute to tumor cell proliferation and progression.

For example, Liu et al (26) showed that FGFR3 mutations are

associated with tumor recurrence and progression in

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. FGFR3 alterations are more

common in non-muscle-invasive UC, with a detection rate of ~15-20%,

while in muscle-invasive UC, the detection rate is ~5-10%. FGFR2

alterations are relatively rare in UC but are also involved in

tumor progression.

Other molecular targets

In addition to the aforementioned molecular pathways

and FGFR alterations, other molecular targets also play important

roles in UC. TROP2 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that is highly

expressed in UC and other solid tumors. Its overexpression is

associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis (27). Sacituzumab govitecan, a

TROP2-targeted ADCs, has demonstrated significant efficacy in the

treatment of metastatic UC (28).

Nectin-4 is another molecule highly expressed in UC. EV, an ADCs

targeting Nectin-4, has shown remarkable therapeutic effects in

locally advanced or metastatic UC (29). HER-2 is overexpressed in a subset

of patients with UC. Trastuzumab deruxtecan, a HER-2-targeted ADCs,

has shown promising efficacy in HER-2-overexpressing UC (30). The expression levels of these

molecular targets are closely related to tumor biology and patient

prognosis.

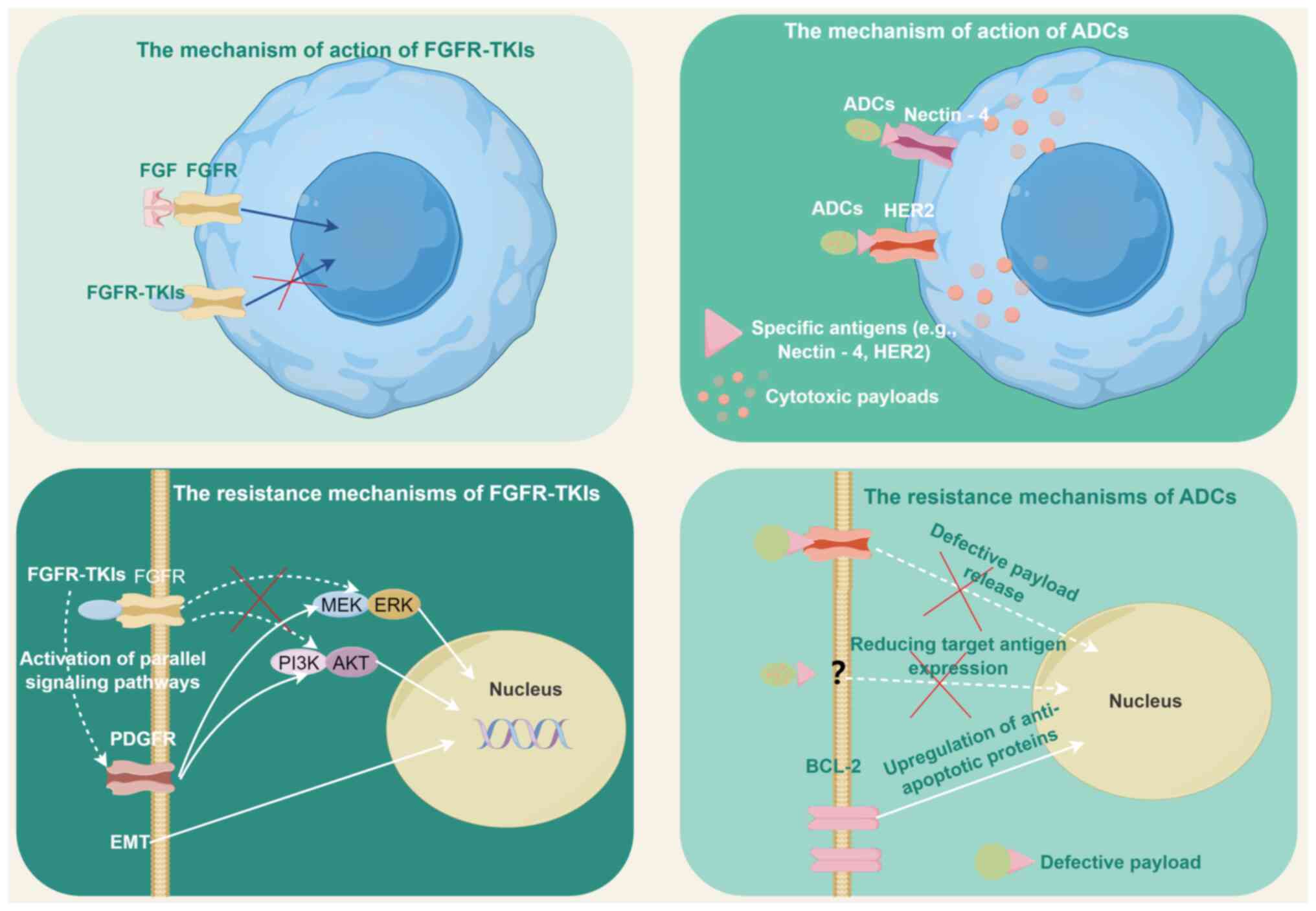

FGFR pathway-directed therapies: Foundations

and clinical implementation

The increasing understanding of FGFR pathway

dysregulation in UC has driven the development of targeted

therapies. The molecular basis of FGFR abnormalities in UC are

addressed in the present section, the clinical data of FGFR

inhibitors such as erdafitinib and infigratinib are reviewed, and

resistance mechanisms are discussed, aiming to guide optimal use of

FGFR-targeted strategies in clinical practice (Fig. 2).

Molecular basis of FGFR dysregulation in

UC

Dysregulation of the FGFR signaling pathway through

amplifications, mutations and gene fusions has been implicated in

UC (31). FGFR signaling plays

crucial roles in tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, migration

and survival (32) (Table I). FGFR pathway dysregulation is a

hallmark of UC, primarily driven by genetic alterations in FGFR3

and, less frequently, FGFR2. These aberrations include activating

mutations, gene fusions and amplifications, which constitutively

activate downstream signaling cascades such as RAS/MAPK and

PI3K/AKT, promoting tumor proliferation and survival (33,34).

| Table IRelated research on FGFR

dysregulation in urothelial carcinoma. |

Table I

Related research on FGFR

dysregulation in urothelial carcinoma.

| First author/s,

year | Aberration

types | Study types | Mechanism of

action | Relationship with

prognosis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ross et al,

2016; Necchi et al, 2019 | FGFR3

mutations/fusions | Genomic

profiling | Activating

mutations (for example, S249C, R248C) and fusions (for example,

*FGFR3-TACC3*) constitutively activate RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT

pathways. | Higher frequency in

advanced UC; associated with resistance to platinum chemotherapy

(ORR: 28% vs. 45% in wild-type). | (33,36) |

| Kim et al,

2018; Khalid et al, 2020 | FGFR3

mutations | Clinical cohort

analysis | Co-occurrence with

TP53 mutations enhances oncogenicity; promotes

ligand-independent kinase activation. | Correlates with

aggressive MIUC phenotypes; shorter OS in metastatic UC

(HR=1.42). | (34,40) |

| Gamallat et

al, 2023 | FGFR3

mutations | Subtype-specific

analysis | Enriched in large

nested variant UC (36%); drives subtype-specific signaling

dysregulation. | Subtype-specific

heterogeneity linked to differential therapeutic responses. | (35) |

| Necchi et

al, 2019 | FGFR3 mRNA

overexpression | Comparative DNA/RNA

analysis | Discordance between

DNA mutations and mRNA levels due to alternative splicing or

epigenetic regulation. | mRNA overexpression

correlates with DNA alterations in 65% of cases; prognostic value

context-dependent. | (36) |

| Song et al,

2023 | FGFR2

amplifications | Genomic and

microenvironmental | Activates

TGF-β-mediated immunosuppression; reduces CD8+ T-cell

infiltration. | Associated with

resistance to ICIs and aggressive phenotypes in advanced UC. | (41) |

| Okato et al,

2024 | FGFR3-mutant

TME |

Preclinical/translational study | M2 macrophage

polarization and immunosuppressive microenvironment; FGFR

inhibition enhances anti-PD-1 efficacy. | Improved survival

in murine models; synergy with immunotherapy in clinical

trials. | (42) |

| Mahmoud et

al, 2024 | FGFR3

overexpression | Immunohistochemical

analysis | Protein

overexpression detected in non-metastatic UC; lacks consistent

survival correlation. | Limited prognostic

significance in early-stage UC; potential biomarker for

FGFR-targeted therapies. | (43) |

| Shohdy et

al, 2019 | Co-alterations

(*CDKN2A/B*) | Mechanistic and

combination study | *CDKN2A/B*

deletions enhance dependency on CDK4/6; co-targeting FGFR and

CDK4/6 delays resistance. | Rationale for

combination therapies in FGFR3-altered UC. | (39) |

| Li et al,

2023 |

FGFR3-mediated resistance | Functional in

vitro study | P4HA2 stabilizes

HIF-1α, bypassing FGFR inhibition; metabolic adaptation drives

resistance. | Identifies novel

resistance mechanisms; informs strategies to overcome erdafitinib

resistance. | (38) |

Comprehensive genomic profiling of 295 advanced UC

cases revealed FGFR3 alterations in 15% of tumors, predominantly

point mutations (for example, S249C, R248C and Y375C) and fusions

(for example, FGFR3-TACC3) (33).

In muscle-invasive UC, FGFR3 mutations occur in 20% of cases, often

co-occurring with TP53 mutations, suggesting a synergistic

oncogenic role (34). Notably,

large nested variant UC exhibits a higher prevalence of FGFR3

mutations (36%), underscoring subtype-specific molecular

heterogeneity (35). At the mRNA

level, FGFR3 overexpression correlates with DNA-level mutations in

65% of advanced UC cases, though discordances exist due to

alternative splicing or epigenetic regulation (36).

FGFR3 mutations induce ligand-independent

dimerization and constitutive kinase activation. Huang et al

(37) demonstrated that FGFR3

silencing in UC cell lines suppressed RAS/MAPK pathway activity,

impairing invasion and proliferation. However, FGFR-driven tumors

often develop resistance via parallel pathways. For instance,

P4HA2-mediated HIF-1α stabilization was shown to bypass FGFR

inhibition in FGFR3-mutant UC, highlighting metabolic adaptation as

a resistance mechanism (38).

Additionally, co-alterations in CDKN2A/B (frequently deleted in

FGFR3-altered UC) may enhance dependency on CDK4/6, providing a

rationale for combination therapies (39).

While FGFR3 mutations were initially associated with

non-muscle-invasive UC and favorable prognosis, metastatic

FGFR3-altered UC correlates with poorer responses to platinum

chemotherapy (ORR: 28 vs. 45% in wild-type) (36). A meta-analysis of 1,574 patients

with UC confirmed that FGFR3 mutations independently predict

shorter OS in advanced stages (HR=1.42, 95% CI: 1.11-1.82)

(40). Conversely, FGFR2

amplifications, observed in 5-8% of UC, are linked to aggressive

phenotypes and resistance to ICIs due to TGF-β-mediated

immunosuppression (41,42).

Recent studies highlight the immunosuppressive

microenvironment in FGFR3-mutant UC, characterized by M2 macrophage

infiltration and reduced CD8+ T-cell activity.

Preclinical models demonstrated that FGFR inhibition synergizes

with anti-PD-1 therapy by reversing immunosuppression, offering a

compelling strategy for clinical translation (42). However, the prognostic value of

FGFR alterations remains context-dependent; for example, FGFR3

overexpression in non-metastatic UC lacks significant survival

correlation (43). Therefore,

FGFR dysregulation in UC is mechanistically diverse, influenced by

alteration type, coexisting genomic events, and TME factors.

Standardized detection methods and functional validation are

critical to optimize patient stratification for FGFR-targeted

therapies.

Application of FGFR-targeted strategies

in the treatment of UC

FGFR-targeted therapies have emerged as a

transformative approach in managing advanced UC, particularly for

patients with FGFR3 alterations. This section critically evaluates

the clinical efficacy, limitations and evolving strategies of FGFR

inhibitors, supported by pivotal trials and real-world evidence

(Table II).

| Table IIApplication of FGFR-targeted

strategies in the treatment of urothelial carcinoma. |

Table II

Application of FGFR-targeted

strategies in the treatment of urothelial carcinoma.

| First author/s,

year | Intervention

strategies | Targets | Study types | Setting | Sample size

(N) | Therapeutic

effect | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Loriot et

al, 2019 | Erdafitinib

monotherapy | Pan-FGFR

(FGFR1-4) | Phase II BLC2001

trial | Post-platinum,

FGFR2/3-altered UC | N=99 | ORR: 40%; median

PFS: 5.5 months; median OS: 13.8 months in platinum-refractory

UC. | (44) |

| Loriot et

al, 2023 | Erdafitinib vs.

chemotherapy | Pan-FGFR

(FGFR1-4) | Phase III THOR

trial | FGFR3-altered,

post-ICI metastatic UC | N=266 | Improved median OS

(12.1 vs. 7.8 months; HR=0.64); ORR: 45.6% vs. 22.4%. | (47) |

| Siefker-Radtke

et al, 2024 | Erdafitinib vs.

pembrolizumab | Pan-FGFR

(FGFR1-4) | Phase III THOR

Cohort 2 | FGFR-altered,

PD-L1-high metastatic UC | N=352 | No OS benefit (10.9

vs. 11.1 months; HR=1.18) in PD-L1-high tumors. | (48) |

| Lyou et al,

2022 | Infigratinib

monotherapy | FGFR1-3 | Phase II trial | Post-platinum,

FGFR3-altered metastatic UC | N=67 | ORR: 25.4%; median

OS: 10.3 months in platinum-refractory UC. | (50) |

| Pal et al,

2022 | Infigratinib

adjuvant therapy | FGFR1-3 PROOF-302

trial | Phase III | FGFR3-mutant

muscle-invasive UC | N=630 | Preliminary data:

35% reduction in recurrence rates in FGFR3-mutant MIUC. | (51) |

| Sternberg et

al, 2023 | Rogaratinib

monotherapy | FGFR1-4 | Phase II/III FORT-1

trial | FGFR1/3 mRNA-high

metastatic UC | N=126 | ORR: 20.7% vs.

19.3% (chemotherapy); median OS: 8.3 vs. 9.8 months (HR=1.02). | (52) |

| Necchi et

al, 2024 | Pemigatinib

monotherapy | FGFR1-3 | Phase II FIGHT-201

trial | FGFR-altered,

post-platinum metastatic UC | N=40 | ORR: 12%; no

survival benefit in UC. | (53) |

| Siefker-Radtke and

Loriot, 2022 | Erdafitinib +

pembrolizumab | Pan-FGFR +

PD-1 | Phase II trial | FGFR-altered,

ICI-naïve metastatic UC | N=58 | ORR: 47%; median

OS: 12.2 months; increased grade ≥3 AEs (e.g., rash,

diarrhea). | (55) |

| Necchi et

al, 2024 | Derazantinib +

atezolizumab | FGFR/CSF1R +

PD-L1 | Phase I/II

trial | FGFR-altered,

post-ICI metastatic UC | N=45 | ORR: 33%; CSF1R

inhibition counteracts macrophage-mediated resistance. | (56) |

Erdafitinib, a pan-FGFR inhibitor, is the first

FDA-approved FGFR inhibitors for metastatic UC harboring

susceptible FGFR2/3 alterations. The phase II BLC2001 trial (N=99)

demonstrated an ORR of 40%, median progression-free survival (PFS)

of 5.5 months, and median OS of 13.8 months in platinum-refractory

patients (44). However, the

single-arm design and absence of a control group limit the

interpretability of these outcomes, particularly in the context of

post-immunotherapy efficacy. Furthermore, the enrichment for

FGFR3-altered tumors, without stratification by mutation subtype,

may overestimate the true treatment effect, as FGFR3-TACC3 fusions

have been associated with more favorable responses than point

mutations (45).

Hyperphosphatemia, a class-effect toxicity due to FGFR1 inhibition,

occurred in 77% of patients but correlated with antitumor efficacy

(P=0.02) (46). Long-term

follow-up confirmed sustained responses, with a 24-month OS rate of

27% (9). The phase III THOR trial

validated erdafitinib's superiority over chemotherapy in

FGFR3-altered metastatic UC (Cohort 1: N=266), showing improved

median OS (12.1 vs. 7.8 months; HR=0.64) and ORR (45.6% vs. 22.4%)

(47). However, in Cohort 2

comparing erdafitinib to pembrolizumab in programmed death-Ligand

1(PD-L1)-high tumors, no OS benefit was observed (10.9 vs. 11.1

months; HR=1.18), underscoring the need for biomarker-driven

selection (48). Real-world

studies corroborated these findings, with Guercio et al

(49) reporting an ORR of 38% and

median OS of 11.2 months in 112 patients.

Infigratinib, an FGFR1-3 inhibitor, showed modest

activity in a phase II trial (N=67) with an ORR of 25.4% and median

OS of 10.3 months in platinum-refractory UC (50). Hyperphosphatemia again emerged as

a common adverse event (AE), observed in 73% of patients (46). The phase III PROOF-302 trial is

evaluating adjuvant infigratinib in FGFR3-mutant

muscle-invasive UC, with preliminary data suggesting a 35%

reduction in recurrence rates (51). Besides, Rogaratinib, an FGFR1-4

inhibitor, failed to outperform chemotherapy in the phase II/III

FORT-1 trial (N=126) despite selecting patients with high FGFR1/3

mRNA expression. ORR was comparable (20.7 vs. 19.3%), and median OS

was shorter (8.3 vs. 9.8 months; HR=1.02), highlighting challenges

in biomarker validation (52).

Furthermore, Pemigatinib, approved in cholangiocarcinoma, showed

limited efficacy in UC (ORR: 12%) in the FIGHT-201 trial (N=40),

with no survival benefit (53).

Its combination with pembrolizumab was explored in

cisplatin-ineligible patients but discontinued due to strategic

reasons (54).

Combining FGFR inhibitors with ICIs aims to overcome

immunosuppressive microenvironments. Erdafitinib plus pembrolizumab

achieved an ORR of 47% and median OS of 12.2 months in a phase II

trial (N=58), though grade ≥3 AEs (for example, rash and diarrhea)

increased significantly (47).

Preclinical models suggest FGFR inhibition reverses M2 macrophage

polarization and enhance CD8+ T-cell infiltration,

supporting this strategy (55).

Derazantinib, a dual FGFR/CSF1R inhibitor, combined with

atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1), showed promise in a phase I/II trial

(N=45) with an ORR of 33%. CSF1R targeting may counteract

tumor-associated macrophage-mediated resistance, offering a novel

therapeutic angle (56).

Resistance to FGFR-tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (TKIs)

Resistance to FGFR-TKIs remains a critical challenge

in UC, driven by diverse molecular mechanisms. Preclinical and

clinical studies have identified several pathways contributing to

acquired or intrinsic resistance, including compensatory signaling

activation, genomic evolution, and TME adaptations. Datta et

al (57) demonstrated that

Akt activation mediates resistance to BGJ398 (infigratinib) in

FGFR3-mutant UC models, highlighting compensatory PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway activation as a key escape mechanism. This finding aligns

with Pettitt et al (58),

who observed in vitro resistance to FGFR inhibitors via

multiple pathways, including MAPK reactivation and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), underscoring the

heterogeneity of resistance mechanisms. Conversely, Kim et

al (59) reported that

FGFR1-overexpressing UC cells develop resistance to BGJ398 through

sustained MAPK/ERK signaling, which could be reversed by MEK

inhibitors, suggesting combinatorial strategies to delay

resistance.

Clinical studies further reveal the impact of FGFR

alterations on therapeutic outcomes. Rezazadeh Kalebasty et

al (60) observed that

patients with UC with FGFR mutations exhibited reduced clinical

benefit from anti-PD-(L)1 therapies post-FGFR inhibition,

suggesting cross-resistance linked to immunosuppressive TME

reprogramming. By contrast, Bellmunt et al (61) found that everolimus/pazopanib

combination therapy improved outcomes in genomically selected

patients with UC, including those with FGFR pathway alterations,

though efficacy was limited by mTOR pathway feedback activation.

Divergent resistance patterns are also influenced by tumor

histology. Brunelli et al (62) identified reduced TROP-2 and

NECTIN-4 expression in sarcomatoid UC variants, correlating with

poor ADCs responses and potential cross-resistance to FGFR-targeted

therapies. Additionally, Audisio et al (63) emphasized the role of clonal

evolution under FGFR inhibition, where subpopulations with

secondary FGFR2/3 mutations or parallel oncogenic drivers (for

example, EGFR) emerge, necessitating longitudinal genomic

profiling.

These studies collectively highlight the

multifactorial nature of FGFR-TKI resistance. While compensatory

signaling (for example, PI3K/AKT and MAPK) and genomic evolution

are predominant mechanisms, TME interactions and histological

subtypes further modulate therapeutic vulnerability. Future

research should prioritize combinatorial approaches (for example,

FGFR inhibitors + MEKi/mTORi) and biomarker-driven adaptive

therapies to circumvent resistance.

ADCs

ADCs have emerged as a transformative therapeutic

class in UC, leveraging tumor-specific antigens to deliver

cytotoxic payloads with precision. ADCs have redefined UC

treatment, with Nectin-4 and HER2 as validated targets (Fig. 2). Relevant studies have optimized

the selection of biomarkers, clarified the pathways of action, and

integrated ADCs into multimodal regimens (Table III). Real-world evidence and

innovative imaging modalities (for example, Nectin-4 PET) will

further personalize ADCs therapy.

| Table IIIApplication of antibody-drug

conjugates strategies in the treatment of UC. |

Table III

Application of antibody-drug

conjugates strategies in the treatment of UC.

| First author/s,

year | Intervention

strategies | Targets | Study types | Setting | Sample size

(N) | Therapeutic

effect | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Li et al,

2024 | EV monotherapy | Nectin-4 | Phase II trial

(China) | Post-platinum

metastatic UC (Asian cohort) | N=60 | ORR 50%, median PFS

5.8 months in previously treated metastatic UC | (66) |

| Rizzo et al,

2025 | EV post-ICI

failure | Nectin-4 | Retrospective study

(ARON-2) | Post-ICI metastatic

UC | N=237 | Median OS 12.1

months vs. chemotherapy 8.3 months (HR=0.62) | (67) |

| Uchimoto et

al, 2025 | BMI impact on EV

efficacy | Nectin-4 | Cohort study

(Japan) | Post-ICI metastatic

UC (ULTRA-Japan) | N=166 | BMI ≥25: ORR 42.9%

vs. 23.1%, OS 14.2 vs. 9.1 months | (68) |

| Mishra et

al, 2024 | Nectin-4 PET-guided

dosing | Nectin-4 | Translational

imaging study | Metastatic UC with

heterogeneous Nectin-4 expression | N=12 | Tracer uptake

correlates with EV response (r=0.72, P=0.008) | (69) |

| Jindal et

al, 2023 | TP53/MDM2 biomarker

analysis | Nectin-4 | Biomarker

analysis | Post-ICI metastatic

UC | N=45 | TP53 wild-type: PFS

6.4 vs. 3.1 months (P=0.03) | (70) |

| Hovelroud et

al, 2024 | EV-associated

diabetic ketoacidosis | Nectin-4 | Case report | Post-ICI metastatic

UC | N=1 | Severe insulin

resistance in a nondiabetic patient | (71) |

| Desimpel et

al, 2024 | EV-associated lung

toxicity | Nectin-4 | Retrospective

analysis | Post-ICI metastatic

UC | N=1,892 | Interstitial lung

disease incidence 0.5% | (72) |

| Pipitone et

al, 2025 | EV extravasation

management | Nectin-4 | Case report &

literature review | Metastatic UC

receiving EV | N=1 (case) | Protocol for tissue

necrosis prevention | (73) |

| Zhu et al,

2025 | EV + pembrolizumab

cost-effectiveness | Nectin-4 | Cost-effectiveness

model | First-line

metastatic UC | Model-based | Incremental

cost-effectiveness ratio>$150,000/QALY; requires price

reduction | (74) |

| Sheng et al,

2024 | Disitamab vedotin

monotherapy | HER2 | Phase II trial | HER2-positive

metastatic UC | N=107 | HER2-positive

metastatic UC: ORR 51.2%, median OS 14.2 months | (77) |

| Chen et al,

2023 | Disitamab vedotin

monotherapy | HER2 | Phase II trial | HER2-positive

locally advanced or metastatic UC | N=76 | HER2-positive

metastatic UC: ORR 51.2%, median OS 14.2 months | (78) |

| Yan et al,

2025 | Disitamab vedotin

in HER2-low populations | HER2 | Phase II trial | HER2-negative

metastatic UC | N=82 | HER2-negative

metastatic UC: ORR 28.6%, median OS 11.8 months | (79) |

| Wang et al,

2025 | Disitamab vedotin

in HER2-null populations | HER2 | Real-world

study | HER2-low/null

metastatic UC | N=154 | ORR 18.2%, median

PFS 4.1 months | (80) |

| Yao et al,

2025 | Disitamab vedotin +

tislelizumab combination | HER2 + PD-1 | Phase II trial | HER2-expressing,

ICI-naïve metastatic UC | N=36 | ORR 58.3%, median

PFS 8.5 months | (82) |

| Ge et al,

2025 | RC48 + PD-1

inhibitors | HER2 + PD-1 | Real-world

study | HER2-expressing

metastatic UC | N=112 | ORR 54.5%, median

OS 16.1 months | (83) |

| Yang et al,

2025 | HER2 prognostic

value (shorter OS) | HER2 | Retrospective

cohort | Muscle-invasive

UC | N=412 | HER2+ associated

with HR=1.58 (P=0.02) in multivariable analysis | (84) |

| Chen et al,

2025 | HER2 in

bladder-preservation therapy | HER2 | Clinical

cohort | HER2+

muscle-invasive UC treated with bladder-sparing therapy | N=127 | No OS difference in

HER2+ MIBC patients | (85) |

| Chou et al,

2022 | TROP-2 in luminal

subtypes | TROP-2 | Molecular subtyping

analysis | Luminal papillary

UC cohort | N=120 | Enriched in luminal

papillary UC | (86) |

| Bahlinger et

al, 2024 | FGFR3/Nectin-4

co-alterations | FGFR3 | Translational

study | Advanced UC with

Nectin-4-high expression | N=200 | FGFR3 mutations in

25% of Nectin-4-high tumors | (87) |

Nectin-4-targeted ADCs

Nectin-4, a cell adhesion molecule overexpressed in

60-90% of UCs, has become a pivotal therapeutic target. EV, an ADCs

comprising a Nectin-4-directed antibody conjugated to monomethyl

auristatin E, received FDA approval based on the EV-301 trial

(64). The recent phase III

EV-302 trial (NCT04223856) established enfortumab vedotin plus

pembrolizumab as a new first-line standard for metastatic UC,

demonstrating superior OS and PFS compared with platinum-based

chemotherapy (median OS: 31.5 vs. 16.1 months; HR=0.47; median PFS:

12.5 vs. 6.3 months; HR=0.45) (65). Recent studies corroborate its

efficacy in diverse clinical settings (66-68). The phase II trial in Chinese

patients with previously treated metastatic UC demonstrated an ORR

of 50% and median PFS of 5.8 months, validating EV's activity in

Asian populations (66). Notably,

the aforementioned study lacked central imaging review and

biomarker stratification beyond Nectin-4 expression, raising

concerns about response assessment heterogeneity. Additionally, the

absence of post-progression treatment details introduces potential

immortal time bias, particularly in a single arm setting without

comparator arm. Real-world data from the ARON-2 retrospective study

(n=237) further revealed that EV achieved a median OS of 12.1

months post-ICI failure, outperforming chemotherapy (8.3 months;

HR=0.62, P<0.001) (67).

Notably, efficacy of EV was influenced by body mass index (BMI):

patients with BMI ≥25 had superior tumor response rates (ORR 42.9%

vs. 23.1%, P=0.04) and longer OS (14.2 vs. 9.1 months, P=0.02),

suggesting metabolic factors may modulate ADCs activity (68).

Biomarker-driven strategies are under exploration.

Mishra et al (69)

developed a Nectin-4 PET tracer to non-invasively quantify target

expression, revealing heterogeneous intratumoral distribution.

Higher tracer uptake correlated with EV response (r=0.72, P=0.008),

supporting personalized dosing. Additionally, TP53/MDM2 alterations

were associated with reduced EV benefit in a biomarker analysis

(n=45): TP53 wild-type tumors had longer PFS (6.4 vs. 3.1 months,

P=0.03) (70).

EV's toxicity profile remains consistent across

studies, with peripheral neuropathy (40-50%), rash (30%) and

hyperglycemia (5-10%) as key AEs (66,67). A pharmacovigilance study (n=1,892)

identified rare but severe AEs, including diabetic ketoacidosis

(0.3%) and interstitial lung disease (0.5%) (71,72). Extravasation management protocols

have been proposed following case reports of tissue necrosis

(73). In addition,

cost-effectiveness analyses weigh EV's benefits against its

economic burden. Zhu et al (74) modeled EV + pembrolizumab as

first-line therapy for metastatic UC, showing incremental

cost-effectiveness ratios exceeding $150,000/QALY, necessitating

price reductions for broader adoption.

HER2-directed ADCs

HER2 expression in UC is heterogeneous, with 5-15%

classified as HER2-positive (IHC 3+ or 2+/FISH+) and 30-40% as

HER2-low (IHC 1+ or 2+ with negative in situ hybridization),

consistent with the ASCO-CAP guidelines (75), which are commonly extrapolated to

UC in the absence of disease-specific criteria. Disitamab vedotin

(DV; RC48), an anti-HER2 ADCs, has shown promise across HER2

expression levels (76). In the

combined analysis of the phase II trials (n=107), DV monotherapy

achieved an ORR of 51.2% and median OS of 14.2 months in

HER2-positive metastatic UC, with grade ≥3 AEs (for example,

neutropenia: 20%) deemed manageable (77). Real-world studies reinforce these

findings: Chen et al (78)

reported an ORR of 48.6% and median PFS of 6.9 months in 76

HER2-positive patients treated with DV ± ICIs.

Intriguingly, DV exhibits activity even in

HER2-low/null cohorts. Yan et al (79) conducted a phase II trial (n=82) in

HER2-negative metastatic UC, demonstrating an ORR of 28.6% and

median OS of 11.8 months, suggesting off-target effects or HER2

detection limitations. Similarly, Wang et al (80) observed ORRs of 24.1% (HER2-low)

and 18.2% (HER2-null) in a real-world study (n=154), though

responses were less durable (median PFS: 4.1 vs. 5.3 months). These

findings challenge traditional HER2 thresholds and advocate for

refined scoring systems.

The combination of DV with ICIs has demonstrated

synergistic efficacy, representing a significant advancement. In

the phase Ib/II RC48-C014 trial (NCT04264936), DV plus the PD-1

inhibitor toripalimab achieved a confirmed ORR of 71.8% and a

median PFS of 9.2 months in patients with HER2-expressing (IHC

1+/2+/3+) locally advanced or metastatic UC (81). Notably, efficacy was consistent

across HER2-low (IHC 1+ or 2+/FISH-) and HER2-positive

(IHC 3+ or 2+/FISH+) subgroups,

challenging traditional HER2 positivity thresholds and suggesting

broader applicability.

DV-ICI combinations synergize efficacy. Yao et

al (82) reported an ORR of

58.3% and median PFS of 8.5 months in 36 ICI-naïve patients with

metastatic UC receiving DV + tislelizumab, with immune-related AEs

in 22%. Ge et al (83)

corroborated these results in a larger cohort (n=112; ORR: 54.5%,

median OS: 16.1 months), highlighting enhanced antitumor immunity.

While HER2 overexpression correlates with aggressive features (for

example, higher grade, nodal metastases), its prognostic value

remains contested. Yang et al (84) analyzed 412 UC specimens, finding

HER2 positivity (12.6%) associated with shorter OS (HR=1.58,

P=0.02) in multivariable analysis. Conversely, Chen et al

(85) reported no OS difference

in HER2-positive muscle-invasive UC treated with

bladder-preservation therapy, underscoring context-dependent

roles.

Emerging targets

TROP-2, expressed in 70% of UCs, is under

investigation with sacituzumab govitecan. Preclinical data reveal

TROP-2 overexpression in sarcomatoid UC (80%) vs. conventional UC

(40%), suggesting histology-specific targeting (62). Chou et al (86) identified TROP-2 enrichment in

luminal papillary subtypes, potentially guiding patient selection.

FGFR3-directed ADCs (for example, erdafitinib combinations) and

tissue factor-targeting agents (for example, tisotumab vedotin) are

in early trials. Bahlinger et al (87) observed FGFR3 mutations in 25% of

Nectin-4-high tumors, advocating dual-target approaches.

Translational insights: Biomarker-driven

patient selection

The advent of targeted therapies in UC has

underscored the critical role of biomarker-driven patient selection

to maximize therapeutic efficacy and minimize toxicity (88). This section evaluates the

translational insights from key clinical trials, focusing on FGFR

inhibitors and ADCs, and discusses the challenges and opportunities

in biomarker validation, heterogeneity, and clinical

implementation.

FGFR alterations: From discovery to

clinical validation

FGFR alterations, particularly FGFR3 mutations and

fusions, have emerged as pivotal oncogenic drivers in UC. These

genetic aberrations, identified in 20-40% of metastatic UC and

35-40% of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)

tumors, lead to constitutive activation of downstream signaling

pathways such as RAS-MAPK and PI3K-AKT, promoting tumor

proliferation, survival and angiogenesis (41). Preclinical studies highlighted

FGFR3's role in bladder carcinogenesis, spurring the development of

selective FGFR inhibitors. Erdafitinib, a first-in-class

pan-FGFR-TKI, demonstrated early promise in the phase 2 BLC2001

trial, achieving an ORR of 40% in FGFR-altered metastatic UC, which

laid the groundwork for subsequent phase 3 validation (47). The discovery of FGFR3's oncogenic

role and its high prevalence in UC established a strong rationale

for biomarker-driven therapeutic strategies, positioning FGFR

status as a critical predictive biomarker for patient

stratification.

The THOR trial (NCT03390504) marked a milestone in

the clinical validation of FGFR-targeted therapy. In this phase 3

study, erdafitinib significantly outperformed chemotherapy in

patients with FGFR3-altered metastatic UC, demonstrating a median

OS of 12.1 months vs. 7.8 months (HR=0.64) and a doubling of PFS

(5.6 vs. 2.7 months) (47).

Nevertheless, the trial's open-label design may introduce

assessment bias, particularly in subjective endpoints such as PFS.

Moreover, the exclusion of patients with prior immunotherapy limits

the generalizability of these findings to contemporary real-world

cohorts, where ICI exposure is now standard of care. These

transformative outcomes, coupled with durable responses and

manageable toxicity, led to erdafitinib's regulatory approvals in

China, USA and other regions, cementing FGFR3 alteration as a

validated biomarker for patient selection. However, challenges

persist, including tumor heterogeneity, the emergence of resistance

mutations (for example, FGFR3 gatekeeper mutations), and the need

for standardized biomarker testing protocols (89). Ongoing research focuses on

optimizing FGFR inhibitor sequencing, exploring combination

therapies with ICIs, and validating liquid biopsy-based FGFR

detection to address spatial and temporal heterogeneity in advanced

UC (42). These efforts aim to

refine precision medicine approaches and extend the benefits of

FGFR-targeted therapy to broader patient subsets.

HER2 as an emerging target: Expanding the

ADCs landscape

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)

overexpression or amplification is observed in 10-20% of UC and has

emerged as a promising target for ADCs (90). Disitamab vedotin (DV), an

HER2-targeted ADCs, combined with the PD-1 inhibitor toripalimab,

demonstrated unprecedented efficacy in the RC48-C016 trial

(NCT04879329), achieving significant OS (11.5 vs. 9.5 months) and

PFS (4.2 vs. 2.9 months) benefits over chemotherapy in

HER2-expressing metastatic UC, including cisplatin-ineligible

patients (81). Notably, efficacy

was consistent across HER2-low and HER2-high subgroups, challenging

the traditional HER2 positivity thresholds and suggesting broader

applicability.

By contrast, EV, a NECTIN-4-directed ADCs, has shown

remarkable activity in unselected UC populations (ORR: 67.7%; CR:

29% in EV-302) (91). While EV

does not require biomarker preselection, retrospective analyses

suggest that NECTIN-4 expression levels correlate with response

durability, raising questions about the need for quantitative

biomarker thresholds (92). This

contrasts with HER2-targeted ADCs, where even low expression may

suffice for clinical benefit, as observed in DV trials. Such

differences underscore the need for target-specific biomarker

frameworks.

Navigating tumor heterogeneity and

resistance in biomarker-driven therapies

UC exhibits significant intratumoral heterogeneity,

with FGFR and HER2 status varying between primary and metastatic

lesions (93). For example, FGFR3

mutations are more common in primary NMIBC, while metastatic sites

often acquire additional genomic alterations (for example, TP53 and

RB1) (94). Longitudinal studies

reveal that FGFR alterations may be lost after BCG therapy or

chemotherapy, necessitating repeat biopsies for dynamic biomarker

assessment (95). Liquid biopsy

approaches [for example, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)] are under

investigation but require validation for real-time monitoring

(96).

Co-mutations (for example, TP53 with FGFR3) may

modulate response to targeted therapies. In the THOR trial,

patients with FGFR3-TACC3 fusions had superior outcomes compared

with those with FGFR3 mutations, suggesting fusion-specific

sensitivity (45). Similarly,

HER2 amplification often coexists with PI3K/AKT pathway activation,

which may confer resistance to DV unless combined with PI3K

inhibitors (97). These findings

highlight the importance of comprehensive genomic profiling to

identify co-targetable pathways.

Biomarker-driven selection has revolutionized UC

treatment, yet challenges in standardization, heterogeneity, and

resistance persist. FGFR and HER2 inhibitors exemplify the success

of precision medicine, while ADCs such as EV demonstrate the

potential of target-agnostic approaches. Future research must

prioritize biomarker validation, combinatorial strategies and

real-world evidence to bridge the gap between trial populations and

clinical practice. Recent evidence indicates that urine tumor DNA

(utDNA) assays achieve 91.4% sensitivity and 95.1% specificity for

detecting UC-associated FGFR3 or TERT mutations, outperforming

cytology and enabling longitudinal genotyping without repeated

cystoscopy (98). This high

diagnostic accuracy underscores the utility of utDNA in capturing

tumor-derived genetic material shed into the urine, thereby

providing a more comprehensive representation of intratumoral and

inter-lesional heterogeneity compared with single-site tissue

biopsies. In the prospective TAR-210 trial, real-time utDNA

screening for FGFR3 alterations increased trial-enrollment

efficiency by 36% and permitted early identification of emergent

FGFR3 gate-keeper mutations (99). By circumventing the spatial

limitations of tissue biopsies, utDNA offers a non-invasive means

to dynamically monitor clonal evolution and adapt therapeutic

strategies in response to molecular changes. Analogously, plasma

ctDNA panels that cover FGFR2/3, PIK3CA, TP53 and ERBB2 can be

performed every 4-6 weeks; rising variant-allele frequencies

precede radiological progression by a median of 4.2 months in

patients receiving erdafitinib or enfortumab vedotin, providing a

lead-time window for therapy adaptation (100). Thus, liquid biopsy platforms

already allow dynamic patient selection and early resistance

surveillance and are being integrated into adaptive trial designs

such as the ULTRA-switch study (100).

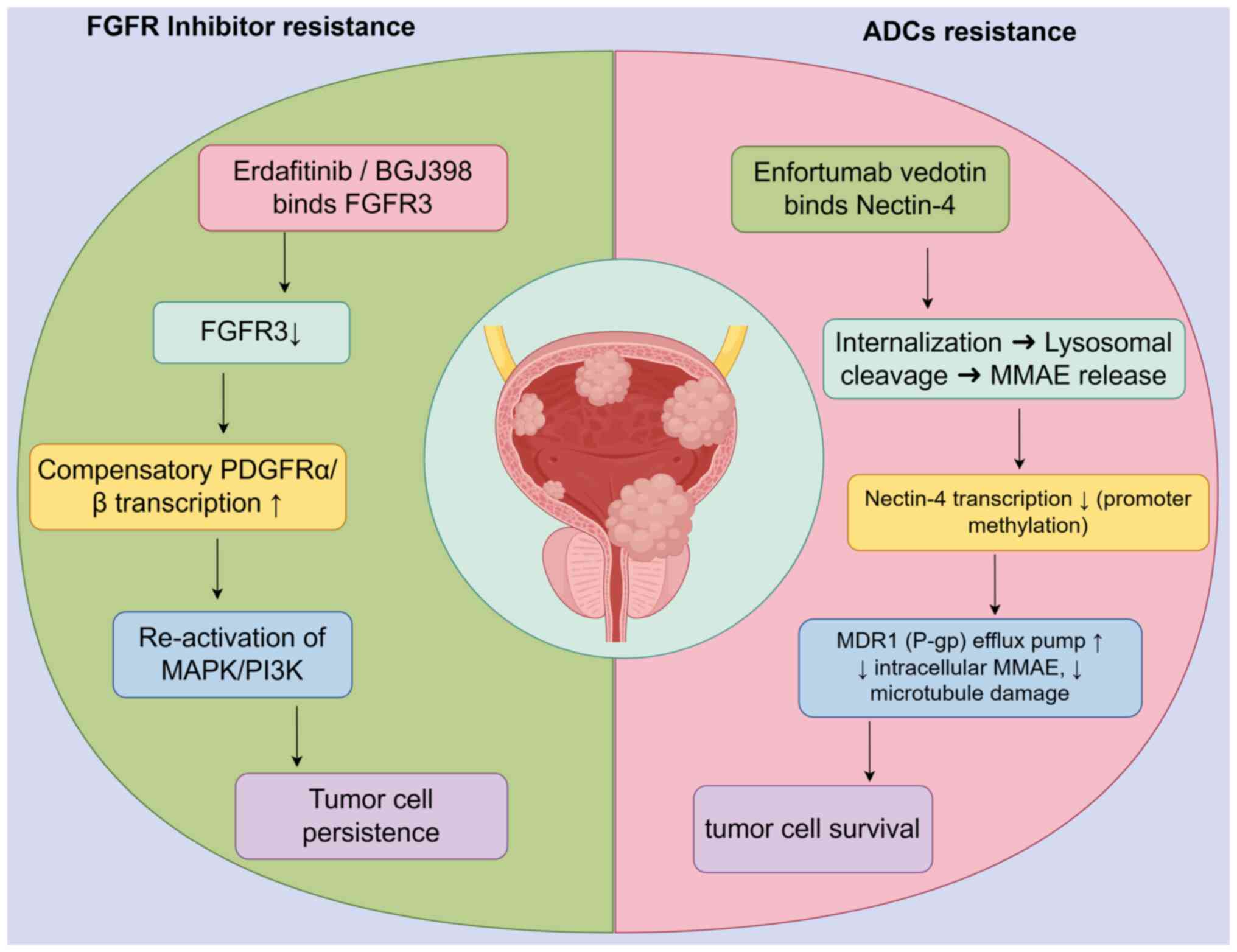

Resistance mechanisms and overcoming

therapeutic limitations

Resistance to FGFR inhibitors and ADCs in UC is

multifactorial, driven by convergent pathways such as kinase

switching, persistent downstream signaling and TME interactions

(101,102) (Fig. 3). However, emerging strategies,

including biomarker-guided combinations, next-generation ADCs and

epigenetic modulation, hold promise for overcoming these barriers.

Future studies must prioritize longitudinal biomarker validation

and innovative trial designs to translate preclinical insights into

clinical success.

Convergent resistance pathways between

FGFR-TKIs and ADCs

Resistance to FGFR inhibitors (for example,

erdafitinib) and ADCs (for example, EV) often involves compensatory

activation of parallel signaling pathways (103,104). For instance, FGFR inhibition in

metastatic UC induces upregulation of platelet-derived growth

factor receptor (PDGFR), enabling tumor cells to bypass FGFR

dependency via PDGF ligand stimulation (105). Preclinical studies in breast

cancer models demonstrated that FGFR inhibitor pemigatinib triggers

PDGFRα/β overexpression, reactivating MAPK/ERK signaling and

promoting minimal residual disease (MRD) survival (106). Similarly, resistance to

HER2-targeted ADCs (for example, disitamab vedotin) may involve MET

or HER2 amplification, as observed in non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC) EGFR-TKI resistance models (107). These findings highlight a shared

mechanism of 'kinase switching' across targeted therapies.

Both FGFR inhibitors and ADCs face resistance due to

sustained activation of downstream effectors. In FGFR3-altered UC,

MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways remain active despite FGFR

inhibition, driven by co-mutations (for example, TP53 and RB1) or

epigenetic adaptations (108,109). For ADCs, resistance may arise

from defective payload release or upregulation of anti-apoptotic

proteins (for example, BCL-2) (110). For example, EV-resistant UC cell

lines exhibit increased expression of multidrug resistance

transporters, reducing monomethyl auristatin E cytotoxicity

(104).

Tumor cells evade targeted therapies through EMT or

lineage plasticity (111). FGFR

inhibition in UC promotes EMT via STAT3 activation, enhancing

metastatic potential (103).

ADCs targeting NECTIN-4 or HER2 may similarly encounter resistance

due to loss of target expression during phenotypic shifts (112,113). Additionally, stromal

interactions in the TME play a pivotal role. Lung fibroblasts

secrete PDGF-AA to support MRD survival in FGFR inhibitor-treated

models, while cancer-associated fibroblasts shield tumor cells from

ADCs penetration by secreting extracellular matrix components

(114).

Novel strategies to circumvent

resistance

Dual inhibition of FGFR and compensatory pathways

(for example, PDGFR or PI3K) has shown promise (115,116). In preclinical UC models,

combining erdafitinib with the DNA methyltransferase 1 inhibitor

GSK3484862 delayed relapse by suppressing PDGFR upregulation and

epigenetic plasticity (90). For

ADCs, co-targeting HER2 and MET (for example, trastuzumab +

savolitinib) is under investigation in NSCLC, with potential

applicability to UC (90).

Bispecific ADCs (for example, targeting HER2 and

TROP2) or payload modifications (for example, TOP1 inhibitors) may

overcome resistance by broadening target engagement or enhancing

cytotoxicity (117). Erdafitinib

intravesical delivery systems (TAR-210) improve local efficacy

while reducing systemic toxicity, achieving 82% recurrence-free

survival in FGFR3-altered NMIBC (99). Similarly, FGFR3-specific degraders

(for example, PROTACs) are emerging to address kinase domain

mutations (118).

FGFR inhibitors may synergize with ICIs by

modulating the TME (119).

Erdafitinib increases T-cell infiltration and reduces

myeloid-derived suppressor cells in UC models, suggesting enhanced

immunogenicity (119). Clinical

trials evaluating erdafitinib + pembrolizumab (NCT05316155) are

underway, with preliminary data showing durable responses in

PD-L1-low populations. Furthermore, histone deacetylase (HDAC)

inhibitors reverse resistance-associated epigenetic silencing

(120). For example, low-dose

decitabine restored FGFR3 expression in erdafitinib-resistant UC

cells, re-sensitizing them to therapy. Metabolic reprogramming (for

example, valine restriction) combined with HDAC6 inhibitors has

shown efficacy in enhancing DNA damage in preclinical models,

offering a novel combinatorial approach (120).

In addition, longitudinal assessment of resistance

mutations via utDNA enables real-time adaptation of therapy

(100). The UI Seek assay, which

detects FGFR3/TERT mutations and methylation markers in urine,

demonstrated 91.37% sensitivity and 95.09% specificity for UC

diagnosis, outperforming traditional cytology (98). In the TAR-210 trial, utDNA-based

FGFR3 screening improved patient enrollment by 36%, highlighting

its utility in guiding adaptive therapies (121). Longitudinal ctDNA monitoring is

being integrated into adaptive trial designs. The ULTRA-ctDNA

sub-study (NCT05538680) will trigger crossover to alternative

targeted agents or combination regimens as soon as emergent FGFR3

secondary mutations or PI3K/AKT pathway alterations are detected,

aiming to prevent clinical relapse rather than merely documenting

it post hoc.

Clinical translation of resistance data is now

beginning to shape sequencing algorithms. In the multicenter

real-world APOLLO study (n=184), patients who progressed on

erdafitinib were systematically re-biopsied; 62% of cases acquired

PIK3CA or PTEN loss-of-function alterations that were absent at

baseline. Subsequent treatment with everolimus plus paclitaxel in

these molecularly selected patients yielded a 34% ORR and 8.1-month

median PFS, whereas non-selected historical controls achieved only

12% and 4.0 months, respectively (49). Similarly, longitudinal ctDNA

surveillance during EV therapy revealed that emergent NECTIN-4 loss

or TUBB3 mutations predicted resistance within 4-6 weeks; early

addition of taxane-based chemotherapy at the time of molecular

progression doubled median time-to-next-treatment compared with

waiting for radiological progression (7.3 vs. 3.5 months, HR 0.48,

P=0.02) (67).

Consequently, an adaptive 'biomarker-triggered'

sequence is being evaluated prospectively in the ULTRA-switch trial

(NCT05538680): Upon detection of FGFR3 gatekeeper or PI3K/AKT

pathway mutations, patients crossover from erdafitinib to a PI3Kβ

inhibitor plus paclitaxel, while NECTIN-4 loss triggers

EV-to-taxane switch. Early safety run-in data (n=42) show a 71%

clinical benefit rate without additive toxicity, supporting the

feasibility of real-time molecular triage.

Challenges and future directions

Resistance to targeted therapies poses a significant

challenge in the treatment of UC. With respect to FGFR inhibitors,

the mechanisms of resistance include secondary gene mutations and

compensatory signaling pathway activation (122). For example, studies have found

that FGFR gene mutations can lead to reduced inhibitor binding

affinity of the inhibitors to the target, thereby causing

resistance. Additionally, the activation of other signaling

pathways, such as the EGFR pathway, can compensate for the

inhibition of the FGFR pathway, promoting tumor cell survival and

proliferation (122,123). Similar resistance mechanisms

have been observed in the use of ADCs. Secondary gene mutations can

alter the structure of the target antigen, reducing the binding

ability of the ADCs (124).

Moreover, the upregulation of drug efflux pump expression can

decrease the intracellular concentration of the cytotoxic drugs,

leading to resistance (124).

To overcome these resistance mechanisms, several

strategies are being explored. Combination therapies represent a

promising approach. For instance, combining FGFR inhibitors with

immunotherapy or chemotherapy may enhance therapeutic efficacy

(125). Preclinical studies have

shown that the combination of FGFR inhibitors and anti-PD-1

antibodies can synergistically inhibit tumor growth by alleviating

immunosuppression in the TME (125,126). The development of

next-generation drugs is also crucial. Researchers are working on

designing FGFR inhibitors with higher selectivity and affinity to

overcome resistance caused by secondary mutations. Furthermore, the

use of ctDNA analysis may help in identifying resistance mechanisms

and guiding treatment adjustments in a timely manner (127).

Managing the AEs associated with targeted therapies

is essential for improving patient quality of life and treatment

adherence. FGFR inhibitors are commonly associated with ocular

toxicity and hyperphosphatemia. Ocular toxicity can manifest as

macular edema, serous retinopathy and blurred vision. Regular

ophthalmologic examinations are recommended for early detection and

management of these side effects early (128). Hyperphosphatemia can usually be

managed through dietary adjustments and the use of phosphate

binders. ADCs, on the other hand, can cause peripheral neuropathy

and myelosuppression. Peripheral neuropathy may require dose

adjustments or the use of neuroprotective agents. Myelosuppression

necessitates regular monitoring of blood cell counts and

appropriate supportive care. It is crucial to establish

standardized management protocols for these AEs to ensure the safe

and effective use of targeted therapies in clinical practice

(129).

Determining the optimal sequence of targeted

therapies, immunotherapy and chemotherapy in UC treatment

strategies remains an area of active research. Factors influencing

treatment sequence decisions include tumor molecular tumor

characteristics, patient performance status and prior treatment

history (130). For example,

patients with FGFR alterations may benefit from the use of FGFR

inhibitors as first-line therapy. However, the optimal timing for

introducing immunotherapy or chemotherapy in combination with

targeted therapies remains unclear. Further studies are needed to

investigate the interactions between different treatment modalities

and their impact on patient outcomes. Clinical trials evaluating

various treatment sequences are ongoing, and their results will

provide valuable insights into the best approaches for optimizing

treatment strategies for UC.

Combining targeted therapies with immunotherapy or

other treatments offers exciting prospects for UC therapy.

Preclinical and early clinical studies have demonstrated that such

combinations can increase antitumor activity. For instance,

combining FGFR inhibitors with ICIs may improve immune cell

infiltration and function in the TME (130). However, combination therapies

also present challenges, such as increased toxicity and trial

design complexity. Careful consideration of the potential side

effects and the development of effective toxicity management

strategies are necessary to ensure the safety of combination

therapies. Additionally, the design of clinical trials must account

for the interactions between different drugs and their

pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics. Despite these

challenges, the potential benefits of combination therapies make

them a promising direction for future research in UC treatment.

As our understanding of the molecular biology of UC

continues to deepen, new therapeutic targets and drugs are

emerging. In addition to the currently established targets such as

FGFR and TROP2, other molecules such as MET, AXL and Wnt/β-catenin

are gaining attention. MET amplification and mutations have been

identified in a subset of patients with UC and are associated with

poor prognosis. Inhibitors targeting MET are being developed and

have shown initial promise in preclinical studies. AXL

overexpression is linked to tumor progression and resistance to

therapy. Drugs targeting AXL may provide new treatment options for

patients with UC. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a role in tumor

cell proliferation and survival. Modulating this pathway may offer

another avenue for therapeutic intervention. These novel targets

and drugs, along with advancements in genomics and molecular

biology technologies, are expected to further expand the

therapeutic landscape for UC and to improve treatment outcomes for

patients.

Conclusion

Significant advancements in biomarker-driven

approaches and targeted therapies for UC have been made, offering

new treatment options and hope for patients. However, challenges

such as biomarker heterogeneity, resistance mechanisms, and the

need for optimized treatment strategies remain. Future research

should focus on improving biomarker validation, developing novel

combination therapies, and designing innovative clinical trials to

enhance the efficacy and precision of targeted treatments in

UC.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JD and YX made significant contributions to the

conception of the manuscript, wrote the first version of the

manuscript and prepared figures. TZ, HS and WL reviewed the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Baiyin City Science and

Technology Plan Project (Preclinical study of c-MET targeted

therapy in bladder cancer; grant no. 2023-2-14Y).

References

|

1

|

Biasatti A, Bignante G, Ditonno F, Veccia

A, Bertolo R, Antonelli A, Lee R, Eun DD, Margulis V, Abdollah F,

et al: New insights into upper tract urothelial carcinoma: Lessons

learned from the ROBUUST collaborative study. Cancers (Basel).

17:16682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Nally E, Young M, Chauhan V, Wells C,

Szabados B, Powles T and Jackson-Spence F: Upper tract urothelial

carcinoma (UTUC): Prevalence, impact and management challenge.

Cancer Manag Res. 16:467–475. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jubber I, Ong S, Bukavina L, Black PC,

Compérat E, Kamat AM, Kiemeney L, Lawrentschuk N, Lerner SP, Meeks

JJ, et al: Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in 2023: A Systematic

Review of Risk Factors. Eur Urol. 84:176–190. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Moussa MJ, Campbell MT and Alhalabi O:

Revisiting treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer: Where do

cisplatin and platinum ineligibility criteria stand? Biomedicines.

12:5192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rivera C, Jabbal IS, Yaghi M, Landau KS,

Muruve N, Saravia D, George TL, Nahleh ZA and Arteta-Bulos R:

Five-year survival comparison of different treatment modalities for

muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and

adenocarcinoma of the bladder: An analysis of the National cancer

database. J Clin Oncol. 40(6_suppl): S5752022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Gupta S, Andreev-Drakhlin A, Fajardo O,

Fassò M, Garcia JA, Wee C and Schröder C: Platinum ineligibility

and survival outcomes in patients with advanced urothelial

carcinoma receiving first-line treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst.

116:547–554. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mao L, Yang M, Fan X, Li W, Huang X, He W,

Lin T and Huang J: PD-1/L1 inhibitors can improve but not replace

chemotherapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review

and network meta-analysis. Cancer Innov. 2:191–202. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li XK and Wang WL: The role novel targeted

agents in the treatment of previously treated patients with

advanced urothelial carcinoma (UC): A meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 22:5165–5171. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Siefker-Radtke AO, Necchi A, Park SH,

García-Donas J, Huddart RA, Burgess EF, Fleming MT, Rezazadeh

Kalebasty A, Mellado B, Varlamov S, et al: Efficacy and safety of

erdafitinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic

urothelial carcinoma: Long-term follow-up of a phase 2 study.

Lancet Oncol. 23:248–258. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yu EY, Petrylak DP, O'Donnell PH, Lee JL,

van der Heijden MS, Loriot Y, Stein MN, Necchi A, Kojima T,

Harrison MR, et al: Enfortumab vedotin after PD-1 or PD-L1

inhibitors in cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced

urothelial carcinoma (EV-201): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2

trial. Lancet Oncol. 22:872–882. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Seront E and Machiels JP: Molecular

biology and targeted therapies for urothelial carcinoma. Cancer

Treat Rev. 41:341–53. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Glaser AP, Fantini D, Shilatifard A,

Schaeffer EM and Meeks JJ: The evolving genomic landscape of

urothelial carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 14:215–229. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ching CB and Hansel DE: Expanding

therapeutic targets in bladder cancer: The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway.

Lab Invest. 90:1406–1414. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

He F, Zhang F, Liao Y, Tang MS and Wu XR:

Structural or functional defects of PTEN in urothelial cells

lacking P53 drive basal/squamous-subtype muscle-invasive bladder

cancer. Cancer Lett. 550:2159242022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Patel VG, McBride RB, Lorduy AC,

Castillo-Martin M, Cha EK, Berger MF, Wang L, Oh WK, Zhu J,

Cordon-Cardo C, et al: Prognostic significance of PIK3CA mutation

in patients with muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (UC). J Clin

Oncol. 34(15_suppl): e160022016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wang DS, Rieger-Christ K, Latini JM,

Moinzadeh A, Stoffel J, Pezza JA, Saini K, Libertino JA and

Summerhayes IC: Molecular analysis of PTEN and MXI1 in primary

bladder carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 88:620–625. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tsuruta H, Kishimoto H, Sasaki T, Horie Y,

Natsui M, Shibata Y, Hamada K, Yajima N, Kawahara K, Sasaki M, et

al: Hyperplasia and carcinomas in Pten-deficient mice and reduced

PTEN protein in human bladder cancer patients. Cancer Res.

66:8389–8396. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Imperial R, Toor OM, Hussain A,

Subramanian J and Masood A: Comprehensive pancancer genomic

analysis reveals (RTK)-RAS-RAF-MEK as a key dysregulated pathway in

cancer: Its clinical implications. Semin Cancer Biol. 54:14–28.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Degirmenci U, Wang M and Hu J: Targeting

aberrant RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling for cancer therapy. Cells.

9:1982020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kim YS, Lee SC, Hwang IG, Lee SJ and Park

SH: Relationship between RAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and location of primary

tumor in urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Res. 79(13_Suppl): S12622019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhou H, Huang HY, Shapiro E, Lepor H,

Huang WC, Mohammadi M, Mohr I, Tang MS, Huang C and Wu XR:

Urothelial tumor initiation requires deregulation of multiple

signaling pathways: implications in target-based therapies.

Carcinogenesis. 33:770–780. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wu G, Wang F, Li K, Li S, Zhao C, Fan C

and Wang J: Significance of TP53 mutation in bladder cancer disease

progression and drug selection. PeerJ. 7:e82612019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ecke TH, Sachs MD, Lenk SV, Loening SA and

Schlechte HH: TP53 gene mutations as an independent marker for

urinary bladder cancer progression. Int J Mol Med. 21:655–661.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Khalid S, Basulaiman BM, Emack J, Booth

CM, Hernandez-Barajas D, Duran I, Smoragiewicz M, Amir E and

Vera-Badillo F: FGFR3 mutation as a prognostic indicator in

patients with urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 37(7_suppl): S4112019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Che X, Liu H, Qin J and Cao S: Landscape

of FGFR2/3 alterations in genitourinary cancer. J Clin Oncol.

41(16_suppl): e150472023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu X, Zhang W, Geng D, He J, Zhao Y and

Yu L: Clinical significance of fibroblast growth factor receptor-3

mutations in bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Genet Mol Res. 13:1109–1120. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zeng P, Chen MB, Zhou LN, Tang M, Liu CY

and Lu PH: Impact of TROP2 expression on prognosis in solid tumors:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 6:336582016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tagawa ST, Balar AV, Petrylak DP,

Kalebasty AR, Loriot Y, Fléchon A, Jain RK, Agarwal N, Bupathi M,

Barthelemy P, et al: TROPHY-U-01: A phase II open-label study of

sacituzumab govitecan in patients with metastatic urothelial

carcinoma progressing after platinum-based chemotherapy and

checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 39:2474–2485. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rosenberg JE, Powles T, Sonpavde GP,

Loriot Y, Duran I, Lee JL, Matsubara N, Vulsteke C, Castellano D,

Mamtani R, et al: EV-301 long-term outcomes: 24-month findings from

the phase III trial of enfortumab vedotin versus chemotherapy in

patients with previously treated advanced urothelial carcinoma. Ann

Oncol. 34:1047–1054. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tagawa ST, Balar AV, Petrylak DP,

Rezazadeh A, Loriot Y, Flechon A, Jain RK, Agarwal N, Bupathi M,

Barthelemy P, et al: Updated outcomes in TROPHY-U-01 cohort 1, a

phase 2 study of sacituzumab govitecan (SG) in patients (pts) with

metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC) that progressed after platinum

(PT)-based chemotherapy and a checkpoint inhibitor (CPI). J Clin

Oncol. 41(6_suppl): S5262023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hall TG, Yu Y, Eathiraj S, Wang Y, Savage

RE, Lapierre JM, Schwartz B and Abbadessa G: Preclinical activity

of ARQ 087, a novel inhibitor targeting FGFR dysregulation. PLoS

One. 11:e01625942016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Dienstmann R, Rodon J, Prat A,

Perez-Garcia J, Adamo B, Felip E, Cortes J, Iafrate AJ, Nuciforo P

and Tabernero J: Genomic aberrations in the FGFR pathway:

Opportunities for targeted therapies in solid tumors. Ann Oncol.

25:552–563. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ross JS, Wang K, Khaira D, Ali SM, Fisher

HA, Mian B, Nazeer T, Elvin JA, Palma N, Yelensky R, et al:

Comprehensive genomic profiling of 295 cases of clinically advanced

urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder reveals a high

frequency of clinically relevant genomic alterations. Cancer.

122:702–711. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kim YS, Kim K, Kwon GY, Lee SJ and Park

SH: Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) aberrations in

muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. BMC Urol. 18:682018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gamallat Y, Afsharpad M, El Hallani S,

Maher CA, Alimohamed N, Hyndman E and Bismar TA: Large, nested

variant of urothelial carcinoma is enriched with activating

mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 among other

targetable mutations. Cancers (Basel). 15:31672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Necchi A, Lo Vullo S, Raggi D, Gloghini A,

Giannatempo P, Colecchia M and Mariani L: Prognostic effect of FGFR

mutations or gene fusions in patients with metastatic urothelial

carcinoma receiving first-line platinum-based chemotherapy: Results

from a large, single-institution cohort. Eur Urol Focus. 5:853–856.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Huang GK, Huang CC, Kang CH, Cheng YT,

Tsai PC, Kao YH and Chung YH: Genetic Interference of FGFR3 impedes

invasion of upper tract urothelial carcinoma cells by alleviating

RAS/MAPK signal activity. Int J Mol Sci. 24:17762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li X, Li Y, Liu B, Chen L, Lyu F, Zhang P,

He Q, Cheng L, Liu C, Song Y and Xing Y: P4HA2-mediated HIF-1α

stabilization promotes erdafitinib-resistance in FGFR3-alteration

bladder cancer. FASEB J. 37:e228402023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Shohdy KS, Vlachostergios PJ, Abdel-Malek

RR and Faltas BM: Rationale for co-targeting CDK4/6 and FGFR

pathways in urothelial carcinoma. Expert Opin Ther Targets.

23:83–86. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Khalid S, Basulaiman BM, Emack J, Booth

CM, Duran I, Robinson AG, Berman D, Smoragiewicz M, Amir E and

Vera-Badillo FE: Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutation as a

prognostic indicator in patients with urothelial carcinoma: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol Open Sci. 21:61–68.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Song Y, Peng Y, Qin C, Wang Y, Yang W, Du

Y and Xu T: Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutation attenuates

response to immune checkpoint blockade in metastatic urothelial

carcinoma by driving immunosuppressive microenvironment. J

Immunother Cancer. 11:e0066432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Okato A, Utsumi T, Ranieri M, Zheng X,

Zhou M, Pereira LD, Chen T, Kita Y, Wu D, Hyun H, et al: FGFR

inhibition augments anti-PD-1 efficacy in murine FGFR3-mutant

bladder cancer by abrogating immunosuppression. J Clin Invest.

134:e1692412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mahmoud SF, Holah NS, Alhanafy AM and

Serag El-Edien MM: Do fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) 2

and 3 proteins play a role in prognosis of invasive urothelial

bladder carcinoma? Iran J Pathol. 19:81–88. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, Garcia-Donas

J, Huddart R, Burgess E, Fleming M, Rezazadeh A, Mellado B,

Varlamov S, et al: Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic

urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 381:338–348. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Parker Kerrigan BC, Ledbetter D, Kronowitz

M, Phillips L, Gumin J, Hossain A, Yang J, Mendt M, Singh S,

Cogdell D, et al: RNAi technology targeting the FGFR3-TACC3 fusion

break-point: An opportunity for precision medicine. Neurooncol Adv.

2:vdaa1322020.

|

|

46

|

Lyou Y, Grivas P, Rosenberg JE,

Hoffman-Censits J, Quinn DI, P Petrylak D, Galsky M, Vaishampayan

U, De Giorgi U, Gupta S, et al: Hyperphosphatemia secondary to the

selective fibroblast growth factor receptor 1-3 inhibitor

infigratinib (BGJ398) is associated with antitumor efficacy in

fibroblast growth factor receptor 3-altered advanced/metastatic

urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol. 78:916–924. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Loriot Y, Matsubara N, Park SH, Huddart

RA, Burgess EF, Houede N, Banek S, Guadalupi V, Ku JH, Valderrama

BP, et al: Erdafitinib or chemotherapy in advanced or metastatic

urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 389:1961–1971. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Siefker-Radtke AO, Matsubara N, Park SH,

Huddart RA, Burgess EF, Özgüroğlu M, Valderrama BP, Laguerre B,

Basso U, Triantos S, et al: Erdafitinib versus pembrolizumab in

pretreated patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer

with select FGFR alterations: cohort 2 of the randomized phase III

THOR trial. Ann Oncol. 35:107–117. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Guercio BJ, Sarfaty M, Teo MY, Ratna N,

Duzgol C, Funt SA, Lee CH, Aggen DH, Regazzi AM, Chen Z, et al:

Clinical and genomic landscape of FGFR3-altered urothelial

carcinoma and treatment outcomes with erdafitinib: A real-world