Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of

the most aggressive malignancies, characterized by late-stage

diagnosis, limited therapeutic options and poor prognosis. Despite

advancements in oncology, the 5-year survival rate remains dismal

at ~13% (1). While substantial

research has focused on genetic and environmental risk factors,

molecular changes and novel treatment options for PDAC, the

influence of biological sex on disease incidence, progression and

treatment response remains insufficiently understood.

Sex- and gender-specific factors are increasingly

recognized as important determinants of disease susceptibility,

progression, and treatment outcomes. Sex refers to biological

attributes, while gender encompasses socially constructed roles and

behaviors (2). Both biological

and sociocultural components of sex and gender can profoundly

influence healthcare delivery from prevention and screening to

diagnosis and therapy, highlighting the need for more

individualized sex- and gender-specific approaches (3,4).

Despite recent efforts, women remain underrepresented in clinical

studies, often due to inclusion biases related to fertility

concerns and hormonal variability (5). In oncology, these disparities remain

insufficiently addressed, hindering progress toward truly

personalized and effective treatment strategies (6). How sex-specific factors shape

disease biology and outcomes is particularly evident in colorectal

cancer. Although it affects both sexes, women over the age of 65

have higher mortality rates and a lower 5-year survival rate

compared with age-matched men (7). This survival disadvantage may, at

least in part, be related to the higher likelihood of women

developing right-sided colon cancer, which is often associated with

more aggressive tumor phenotypes, and to their greater

susceptibility to treatment-related toxicity (7,8).

These findings underscore the clinical relevance of sex-based

differences in cancer biology and outcomes and highlight

opportunities to develop strategies that optimize treatment based

on sex-specific factors.

By contrast, sex-specific differences in PDAC remain

poorly studied, resulting in limited evidence for sex-based

variations in pathophysiology and a lack of precision medicine

approaches tailored to both men and women. The present review

summarizes current evidence on the epidemiological, biological and

clinical aspects of sex differences in PDAC. By identifying key

disparities, the present review aims to highlight the need for

sex-specific strategies in prevention, diagnosis and treatment,

which could advance personalized and effective care, while offering

approaches to improve the integration of these variables into basic

and clinical research.

Epidemiology

PDAC displays a slightly higher incidence in men

than in women, with 269,709 vs. 241,283 respective new cases

reported in 2022, ranking it as the 15th and 16th most common

cancer in men and women, respectively (9). Globally, PDAC incidence rates are

rising, with a disproportionately steeper increase observed in

women. Between 1975 and 2016, incidence rates increased annually by

1.1% in women compared with 0.38% in men, highlighting a growing

burden of PDAC among women (10).

The highest incidence rates are reported in highly developed

regions, likely due to lifestyle and environmental factors, with

Western Europe currently exhibiting the highest lifetime risk of

PDAC (11).

Notably, the incidence and mortality of PDAC peak at

different ages between sexes: In men, the highest number of cases

and deaths occurs between ages 65-69 years, whereas in women, it

peaks between ages 75-79 years (12). Of particular concern is the rising

incidence of PDAC among women <40 years, who now show higher

rates compared with age-matched men (13,14). A study by Cavazzani et al

(13) reported the greatest

increase in PDAC incidence among women aged 18-26 years, with an

average annual percentage change (AAPC) of 9.37% [95% confidence

interval (CI), 7.36-11.41%; P<0.0001], compared with an AAPC of

4.43% in men of the same age group. Survival rates remain poor for

both sexes, with a 5-year survival of ~13% (1). While the age-standardized mortality

rate is higher in men overall, this varies by age group. The most

pronounced sex difference in relative survival is observed in

patients <44 years, with survival rates of 24.37% in women vs.

18.03% in men. However, this difference diminishes with age, and

survival rates become comparable in individuals >65 years (4.68%

in women vs. 4.44% in men) (15).

PDAC represents a growing global public health

challenge. The disproportionately steeper rise in incidence among

women, particularly at younger ages, highlights the urgent need for

sex-specific strategies in prevention, early detection, and

treatment.

Risk factors

Multiple risk factors for PDAC have been well

established, including tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption,

obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic pancreatitis, and genetic

predisposition (14). However,

sex-based differences are often overlooked. This section provides

an overview of sex-specific variations in non-genetic PDAC risk

factors.

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking is a well-documented risk factor

for PDAC, with a reported OR of 1.77 (95% CI, 1.38-2.26) for

current smokers compared with never smokers, and a dose- and

duration-dependent increase in risk (16). However, evidence regarding sex

differences in smoking-related PDAC risk remains conflicting. A

large meta-analysis found no significant difference in

smoking-related PDAC risk between men and women (16). By contrast, a multiethnic cohort

study involving 192,035 participants reported a notably higher risk

in women who began smoking before age 20 years, with a 71%

increased PDAC risk [hazard ratio (HR), 1.71; 95% CI, 1.14-2.57],

compared with a 49% increase in men (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.03-2.15)

(17). These findings are

supported by data from the International Pancreatic Cancer

Case-Control Consortium, which reported a particularly elevated

risk among female smokers <65 years of age (18). Although smoking cessation

significantly reduces PDAC risk, the benefit appears to be less

pronounced in women. A pooled analysis from Japan found that female

former smokers remained at elevated risk, whereas the risk

normalized in men after quitting (19,20).

These findings suggest that smoking may pose a

particularly strong and persistent risk for younger women, even

when cessation occurs later in life. Thus, although smoking is a

well-established PDAC risk factor, sex- and age-related

differences, are not yet firmly supported and warrant further

high-quality prospective research. Key studies reporting

sex-specific differences in smoking-related PDAC risk are

summarized in Table I.

| Table IComparative summary of studies on

smoking and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma risk by sex. |

Table I

Comparative summary of studies on

smoking and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma risk by sex.

| First author,

year | Number of

patients | Study design | Results | P-value | Evidence

levela | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Gram et al,

2023 | 1,936 | Prospective cohort

study, followed participants aged 45-75 years for a mean of 19.2

years | Current

smoker:

♀ HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.24 1.79)

♂ HR, 1.48 (95% CI, 1.22-1.79)

Early smoking:

♀ HR, 1.71 (95% CI, 1.14-2.57)

♂ HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.03-2.15) | N/A for interaction

by sex N/A for interaction by sex | B | (17) |

| Bosetti et

al, 2012 | 6,507 cases/12, 890

controls | Pooled case-control

(PanC4 Consortium) | Current smoker (15

to <25 cigarettes/day):

♀ OR, 2.60 (95% CI, 1.74-3.90)

♂ OR, 1.92 (95% CI, 1.55-2.38)

High consumption (≥25 cigarettes/day):

♀ OR, 3.84 (95% CI, 2.73-5.42)

♂ OR, 2.92 (95% CI, 2.01-4.23) | 0.195

0.286 | B | (18) |

| Koyanagi et

al, 2019 | 354,154 | Pooled analysis of

10 prospective population-based cohort studies in Japan | Current smoker

(compared with never smokers):

♀ HR, 1.81 (95% CI, 1.43-2.30)

♂ HR, 1.59 (95% CI, 1.32-1.91)

Former smoker (compared with never smokers):

♀ HR, 1.77 (95% CI, 1.19-2.62)

♂ HR, 1.10 (95% CI, 0.89-1.36)

Risk per 10 pack-years (compared with never smokers):

♀ HR, 1.06 (95% CI, 0.92-1.22)

♂ HR, 1.06 (95% CI, 1.03-1.10) | N/A for interaction

by sex

N/A for interaction by sex N/A for interaction by sex | A | (19) |

Body mass index (BMI) and obesity

Obesity is recognized as a modifiable risk factor

for PDAC, with growing evidence suggesting that women may be

particularly vulnerable to obesity-related risk (20). A study reported that women with a

BMI ≥40 had more than double the risk of PDAC [relative risk (RR),

2.76; 95% CI, 1.74-4.36] (21). A

pooled analysis from the PanScan Consortium further emphasized that

central adiposity, measured by the waist-to-hip ratio, is more

strongly associated with PDAC risk in women than in men (22). This finding suggests that fat

distribution may play a more critical role in PDAC risk among

women. An additional study indicated that components of metabolic

syndrome, defined as abdominal obesity, diabetes, hypertension and

dyslipidemia, increase PDAC risk more significantly in women

(23). Conversely, obesity during

early adulthood appears to be more closely associated with PDAC

mortality in men, highlighting the potential influence of both

timing and age of weight gain (24).

Table II provides

an overview of sex-specific effects of overweight and obesity on

PDAC risk. In summary, multiple large, prospective cohort and

pooled analyses support that obesity, particularly central or

severe obesity, confers a greater PDAC risk in women than in men,

although age and timing of weight gain may modify this

relationship. Further research should clarify the underlying

sex-specific metabolic and hormonal factors driving this

vulnerability.

| Table IIComparative summary of studies on

obesity and PDAC risk by sex. |

Table II

Comparative summary of studies on

obesity and PDAC risk by sex.

| First author,

year | Number of

patients | Study design | Results | P-value | Evidence

levela | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Genkinger et

al, 2015 | 1,096,492 | Pooled analysis of

20 prospective cohort studies from the NCI BMI and Mortality Cohort

Consortium | Waist circumference

(per 10 cm):

♀ HR, 1.09 (95% CI, 1.03-1.15)

♂ HR, 1.08 (95% CI, 1.02-1.15)

Waist-to-hip ratio:

♀ HR, 1.10 (95% CI, 1.01-1.21)

♂ HR, 1.12 (95% CI, 1.02-1.23)

BMI in early adulthood (per 5 kg/m2):

♀ HR, 1.11 (95% CI, 1.03-1.21)

♂ HR, 1.25 (95% CI, 1.15-1.35) | 0.86

0.80

0.04 | A | (24) |

| Arslan et

al, 2010 | 2,170 PDAC

cases/2,209 matched controls | Pooled nested

case-control study (Pancreatic Cancer Cohort

Consortium-PanScan) | PDAC risk and body

composition BMI:

♀ OR, 1.34 (95% CI, 1.05-1.70)

♂ OR, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.04-1.69)

Waist-to-hip-ratio:

♀ OR, 1.87 (95% CI, 1.31-2.69)

♂ N/A, not significant | N/A for interaction

by sex

N/A for interaction by sex | A | (22) |

| Calle et al,

2003 | 900,053 | Prospective cohort

study (Cancer Prevention Study II), Follow-up 16 years | PDAC mortality by

BMI BMI, 25.0-29.9 kg/m2:

♀ RR, 1.11 (95% CI, 1.00-1.24)

♂ RR, 1.13 (95% CI, 1.03-1.25)

BMI, 30.0-34.9 kg/m2:

♀ RR, 1.28 (95% CI, 1.07-1.52)

♂ RR, 1.41 (95% CI, 1.19-1.66)

BMI, ≥40.0 kg/m2:

♀ RR, 2.76 (95% CI, 1.74-4.36)

♂ RR, 1.49 (95% CI, 0.99-2.22) | N/A for interaction

by sex

N/A for interaction by sex

N/A for interaction by sex | A | (21) |

| Johansen et

al, 2010 | 577,315/86 2 PDAC

cases | Pooled prospective

cohort study from the Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Project

(Me-Can) | PDAC risk and

metabolic syndrome [sex-specific results (z-score-based

HRs)]

BMI:

♀ 0.92, (95% CI, 0.79-1.07)

♂ 0.90, (95% CI, 0.80-1.02)

Mid-blood pressure:

♀ 1.34, (95% CI, 1.08-1.66)

♂ 1.15, (95% CI, 0.97-1.35)

Glucose:

♀ 1.98, (95% CI, 1.41-2.76)

♂ 1.37, (95% CI, 1.01-1.85)

Cholesterol:

♀ 1.16, (95% CI, 0.96-1.41)

♂ 0.81, (95% CI, 0.69-0.95) | 0.45

0.06

0.02

0.08 | A | (23) |

| Jiao et al,

2010 | 952,494/2, 639 PDAC

cases | Pooled analysis of

7 prospective cohorts (US, Finland and China). Mean follow-up of

6.9 years | PDAC risk and

BMI

BMI (per 5 kg/m2 increment):

♀ RR, 1.12 (95% CI, 1.05-1.19)

♂ RR, 1.06 (95% CI, 0.99-1.13)

BMI, 30.0-34.9 kg/m2:

♀ RR, 1.34 (95% CI, 1.11-1.64)

♂ RR, 1.11 (95% CI, 0.95-1.30) | N/A for interaction

by sex

N/A for interaction by sex | A | (20) |

Diabetes mellitus

The association between diabetes mellitus and PDAC

appears to be largely independent of sex. While a study has

reported a higher prevalence of PDAC among male diabetic patients

(25), others found no

statistically significant difference in overall PDAC risk between

men and women (25-28). Although sex alone may not

significantly modify PDAC risk in diabetic patients, lifestyle

factors and comorbidity patterns, which often differ by sex, may

still influence overall risk and should be considered in prevention

strategies (26-28).

Alcohol

Heavy alcohol consumption (defined as ≥9 drinks per

day) is associated with an increased risk of PDAC, particularly in

men (29). Several large studies

and pooled analyses have shown that the association between heavy

alcohol intake and PDAC is more pronounced in men than in women

(29-31). However, this apparent sex

difference may partly reflect a statistical limitation: Female

heavy drinkers are often underrepresented in study cohorts,

limiting the ability to accurately assess risk in women (31). Nonetheless, a pooled analysis of

14 prospective cohort studies (n=2,187 PDAC cases) found a

statistically significant association between alcohol intake ≥30

g/day and PDAC in women (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.07-1.85) (30). At even higher intake levels, the

risk was more substantial in men. Notably, the study could not

assess the impact of very high alcohol intake in women due to the

small number of female participants consuming ≥45 g/day (30). In regions with higher

socioeconomic status, a growing trend of alcohol consumption has

been observed among young women (32). If this trend continues, alcohol

may become an important contributor to an increased PDAC incidence

among women in the coming years.

Chronic pancreatitis (CP)

CP significantly increases the risk of PDAC, with a

reported 16- to 22-fold elevation, particularly within the first 2

years following a CP diagnosis (33,34). CP is more commonly diagnosed in

men, who also tend to develop the disease at a younger age compared

with women (33). This male

predominance is largely attributed to higher rates of alcohol

consumption and smoking (33,35). However, to date and to the best of

our knowledge, no significant sex-based differences have been

observed in the magnitude of PDAC risk among patients with CP

(33-35).

Hormonal factors

There is growing evidence suggesting that female sex

hormones may exert a protective effect against the development of

PDAC. However, studies examining hormone-related exposures have

yielded conflicting results (Table

III). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 21

observational studies involving 7,700 PDAC cases adds important

context: Ever-use of oral contraceptives (OCs) was associated with

a modest but statistically significant reduction in PDAC risk (RR,

0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.98) (36).

This inverse association was particularly evident in high-quality

studies and European cohorts, while no clear effect emerged in

studies from Asia or America (36). Notably, no dose-response

relationship was observed, as PDAC risk did not vary by duration of

OC use (36). Despite notable

heterogeneity, the meta-analysis supports a potential protective

role of exogenous estrogen.

| Table IIIComparative summary of studies on

female hormonal determinants and PDAC risk. |

Table III

Comparative summary of studies on

female hormonal determinants and PDAC risk.

| First author/s,

year | Number of

patients | Study design | Results | P-value | Evidence

levela | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ilic et al,

2021 | 21 studies (10

case-control + 11 cohort), 7,700 PDAC cases | Systematic review

and meta-analysis (Europe, America and Asia) | Ever use of OCs:

RR, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.73-0.98) No dose-response relationship for

duration: <1 year: RR, 1.08 (95% CI, 0.91-1.29) <5 years: RR,

1.07 (95% CI, 0.95-1.19) 5-10 years: RR, 1.08 (95% CI,

0.93-1.26) | 0.03

>0.05 for all | A | (36) |

| Andersson et

al, 2018 | 17,035/110 PDAC

cases | Prospective

population-based cohort study (Sweden) | Age at menarche

(continuous): HR, 1.17 (95% CI, 1.04-1.32) Ever use of any HRT: HR,

0.48 (95% CI, 0.23-1.00) Estrogen-only HRT: HR, 0.22 (95% CI,

0.05-0.90) Ever use of OC: HR, 0.68 (95% CI, 0.44-1.06) Parity,

breastfeeding and menopause timing: HR, ~1.00 | 0.008

0.049

0.035

0.091

>0.05 for all | B | (37) |

| Lee et al,

2013 | 118,164/323 PDAC

cases | Prospective cohort

study (USA) | Estrogen-only HRT,

current use: HR, 0.59 (95% CI, 0.42-0.84) Estrogen HRT ≥20 years:

HR, 0.55 (95% CI, 0.33-0.91) OC use ≥10 years: HR, 1.72 (95% CI,

1.19-2.49) High dose OC use ≥10 years: HR, 2.08 (95% CI, 1.05-4.12)

Age at menarche, parity, menopause and breastfeeding HR, ~1.00 | 0.003

0.036

0.014

0.024

>0.05 for all | A | (38) |

| Prizment et

al, 2006 | 37,459/228 PDAC

cases | Prospective

population-based cohort study (USA) | Age at menopause

≥55 vs. <45 years: HR, 0.35 (95% CI, 0.18-0.68) Age at menopause

(continuous, 5-year increase): HR, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.72-0.91) Ever

use of any HRT: HR, 1.07 (95% CI, 0.82-1.40) Ever use of OC: HR,

0.90 (95% CI, 0.62-1.30) Parity, menarche and age at first birth

HR, ~1.00 | 0.005

0.001

0.606

0.566

>0.05 for all | B | (39) |

| Duell and Holly,

2005 | 241 PDAC cases/818

controls | Population-based

case-control study (USA) | Age at menopause

≥55 vs. <45 years: OR, 1.9 (95% CI, 1.2-2.8) Estrogen-only HRT:

HR, 0.84 (95% CI, 0.62-1.1) Ever use of OC: HR, 0.95 (95% CI,

0.65-1.4) | 0.003

>0.05

>0.05 | B | (40) |

| Stevens et

al, 2009 | 995,1957/1,182 PDAC

cases | Prospective cohort

study (UK) | Parity (ever vs.

never): RR, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.79-0.98) Age at menarche, age at birth,

age at menopause, breastfeeding and number of children | 0.01

>0.05 for all | A | (41) |

In this context, findings from individual studies

illustrate the variability across hormone-related exposures.

Several studies investigating exogenous hormone therapy (HRT)

reported reduced PDAC risk: A Swedish cohort study of 17,035 women

linked high estrogen levels and HRT use to lower PDAC risk

(37), and another large cohort

likewise found a protective association with estrogen therapy

(38). However, these results

were not replicated in an American cohort of 37,459 women, in which

HRT showed no association with PDAC risk (39).

Studies assessing endogenous estrogen exposure show

similar inconsistency. In the American cohort, later menopause was

related to a lower PDAC risk and a significant inverse relationship

was observed between age at menopause and risk, suggesting a

protective effect of longer endogenous estrogen exposure (39). However, a separate case-control

study reported the opposite: An increased PDAC risk was associated

with later menopause (40). To

date and to the best of our knowledge, no consistent association

has been observed between PDAC risk and other reproductive factors

such as parity (number of children) or breastfeeding (37-39,41). In conclusion, current data suggest

that higher lifetime estrogen exposure may reduce PDAC risk, though

results are inconsistent and often lose significance after

adjustment, indicating potential residual confounding or

differences in population characteristics, hormone formulations or

follow-up duration. Overall, evidence is moderately strong but

lacks consistency and mechanistic clarity. While estrogen may have

a protective role, current data are insufficient to confirm

causality, warranting further research integrating hormonal and

genetic markers.

Pharmacokinetics and toxicity of

chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutic drugs are commonly prescribed at

standardized doses based on body weight or body surface area,

although therapeutic efficacy is more closely related to

circulating drug concentrations than to the administered dose

(6). As a result, interindividual

variations in drug metabolism can lead to suboptimal outcomes,

including reduced efficacy or increased toxicity (6). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

differ between the sexes, yet this is often overlooked in clinical

dosing strategies. Factors such as higher body fat percentage in

women (42), greater renal

function in men (6), and

differences in muscle mass, total body water, cardiac output, and

liver perfusion (4) all influence

drug distribution and metabolism. A recent systematic review

identified significant sex-specific pharmacokinetic differences for

several drugs, including 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and paclitaxel, both

of which are integral components of standard PDAC treatment

regimens (4,43). 5-FU, a key drug in the FOLFIRINOX

regimen (leucovorin, 5-FU, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) (43), is cleared >20% more rapidly in

men than in women. Consequently, equivalent dosing may lead to

increased toxicity in women and a potential risk of underdosing in

men (44). Notably, this sex

difference in clearance remains significant even after adjusting

for age and dose (45). The

difference may be partially explained by sex-specific variation in

the activity of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, the primary enzyme

responsible for metabolizing 5-FU (45). In addition, genetic variants of

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, an enzyme that influences 5-FU

cytotoxicity, have demonstrated sex-dependent effects, suggesting

that female patients may require lower 5-FU doses to avoid toxicity

(42). In line with these

findings, a study on colorectal cancer has shown that women

experience a significantly higher rate of side effects from

5-FU-based therapies, both in the adjuvant and metastatic settings

(4). In the treatment of

colorectal cancer, increased toxicity has been reported not only in

combination regimens but also with 5-FU monotherapy (4).

Sex-related pharmacokinetic differences for

oxaliplatin are inconsistent. While a study has reported a 40%

lower clearance in women (46),

another found no significant sex-based differences (47). Data on irinotecan are similarly

mixed. Certain studies suggest that women may have lower clearance,

reduced volume of distribution and decreased bioavailability,

potentially influencing both efficacy and toxicity (48,49). However, another investigation

attributed this variability primarily to liver function, with

minimal differences attributable to sex (50). Although 5-FU, irinotecan, and

oxaliplatin are administered in combination in PDAC treatment, the

interactions and cumulative pharmacokinetic effects of these drugs

remain poorly understood. Although pharmacokinetic findings imply

differing toxicity risks, few studies have systematically evaluated

chemotherapy-related adverse events in PDAC by sex. Existing data

are often limited by small sample sizes or single-center designs.

Some report higher toxicity rates in women, such as constipation,

hand-foot syndrome and epigastric pain (51), and an increased incidence of

febrile neutropenia and agranulocytosis during FOLFIRINOX treatment

(52). Others, including a

prospective Korean study, found no significant overall differences

but noted more frequent dose reductions among female patients

(53), suggesting lower tolerance

or heightened susceptibility to toxicity.

Gemcitabine, either as a monotherapy or in

combination with nab-paclitaxel, is another well-established PDAC

treatment regimen for PDAC. To date and to the best of our

knowledge, no clinical evidence supports a sex-specific difference

in gemcitabine pharmacokinetics (54,55). While sex has been shown to

influence the clearance and toxicity of solvent-based paclitaxel

(56,57), this effect is not observed with

nab-paclitaxel, which displays no sex-related differences in

elimination (58), suggesting a

distinct pharmacological mechanism.

In summary, pharmacokinetic studies of 5-FU,

irinotecan and oxaliplatin suggest that standardized dosing does

not adequately account for sex-specific variability, with men at

risk of potential underdosing and women at higher risk of toxicity.

Major PDAC trials rarely stratify adverse events by sex,

underscoring the need for comprehensive, sex-disaggregated toxicity

analyses. Addressing this through novel therapy concepts is

essential to optimize therapeutic efficacy, minimize adverse events

and advance sex-sensitive treatment strategies in pancreatic

cancer.

Prognosis and therapy response

Few studies, albeit with large populations, have

explored sex differences in treatment allocation and prognostic

outcomes in PDAC. Notably, the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group

conducted two large retrospective studies analyzing sex-based

differences in tumor characteristics, treatment decisions, and

survival outcomes in both stage I-III and metastatic PDAC cohorts,

each including >6,000 patients (59,60). In both cohorts, female patients

were older, had worse performance status but fewer comorbidities

and were less likely to receive systemic chemotherapy compared with

male patients. The primary reason for this disparity was a higher

preference among women for best supportive care across all disease

stages. No sex-based difference was observed in the likelihood of

undergoing surgical resection in resectable PDAC, except among

women aged ≥80 years, who were less frequently offered surgery

(59,60). By contrast, two additional studies

reported a lower likelihood of curative treatment planning for

female patients. The first was a preliminary analysis of 100

patients from the Chemotherapy, Host Response and Molecular

dynamics in Periampullary cancer (CHAMP) study, which includes both

pancreatic and periampullary adenocarcinomas. The second was a

nationwide Swedish cohort study of 5,677 patients with

periampullary tumors, which similarly reported that fewer women

were planned for curative treatment (61,62). However, in the Swedish cohort,

this difference disappeared after adjustment for age and tumor

location, unlike in the CHAMP study. This discrepancy may be

explained by the inclusion of other periampullary tumors, such as

duodenal adenocarcinomas, which have different surgical and

prognostic profiles and may influence treatment decisions. The

largest study to date, conducted by the American College of

Surgeons and including 22,993 patients, identified male sex as a

risk factor for major morbidity following pancreaticoduodenectomy

(63). These findings highlight

that sex disparities in treatment outcomes are not unequivocal and

must be interpreted with caution. Most available studies are

retrospective and heterogeneous in design, with varying inclusion

criteria, treatment eras and adjustment for confounders, which

limits the strength of causal inference. Observed associations

between sex and prognosis in PDAC likely reflect the interplay of

multiple factors, including age, performance status, comorbidities,

socioeconomic status, access to specialized care and patient

preferences, rather than biological sex alone. Few studies have

stratified analyses or applied sensitivity models to disentangle

these sociocultural and clinical variables from intrinsic

biological differences. Nevertheless, several studies have

identified female sex as an independent prognostic factor for

improved overall survival (OS) in PDAC (59,60,64). Large cohort studies have reported

a statistically significant increase, or at least a trend toward,

increased OS in women, even after adjusting for confounders.

However, in the end, only two studies have directly examined sex

differences in response to FOLFIRINOX. A small cohort study by

Hohla et al (65), which

included 49 patients with unresectable PDAC, found a significantly

higher disease control rate in female patients treated with

FOLFIRINOX compared with males. Similarly, the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11

randomized trial observed a trend toward longer median OS in female

patients with metastatic disease receiving FOLFIRINOX, although

this did not reach statistical significance (64). These findings again raise

important questions about whether differences in chemotherapy

toxicity and metabolism contribute to improved survival outcomes in

women, underscoring the need for prospective studies with

sex-stratified analyses and standardized reporting to improve the

assessment of the biological vs. sociocultural determinants of

treatment response in PDAC (3).

Immune response and the tumor

microenvironment (TME)

Sex-based biological differences, particularly

within the immune system, are well recognized across multiple

diseases, including cancer (66-68). Generally, women exhibit stronger

innate and adaptive immune responses, which has been linked to a

higher prevalence of autoimmune disorders in women (66,67). The immune differences in men and

women are regulated by both gonadal hormones, primarily estrogen

and androgens and genetic mechanisms (66,69). Notably, stronger interferon

signaling in women may result from two key mechanisms: i)

Estrogen-mediated immune activation; and ii) X chromosome-linked

differences. Estrogen enhances interferon production through

Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) activation (70,71), and since TLR7 is encoded on the X

chromosome, its expression and downstream immune responses are

amplified in women (72). In

addition, T and B cells in women demonstrate enhanced signaling and

antibody responses to infections and vaccinations (67,73), which may contribute to more

effective tumor immune surveillance. Estrogen further shapes the

TME by modulating T cell activation and immune checkpoint

expression (67,68,74). Across several cancer entities, the

TMEs in women tend to display stronger immune activation than those

of men (68,75).

In PDAC, the TME is a key contributor to immune

evasion and poor prognosis; it is typically characterized by scarce

cytotoxic T cell infiltration, abundant regulatory T cells and a

dense, fibrotic stroma, which are features that also limit the

response to immunotherapy (76,77). As a result, checkpoint inhibitors

have shown limited efficacy in PDAC due to the inherently

immunosuppressive nature of the tumor (78). Nevertheless, emerging evidence

indicates that sex differences do influence immune pathways and the

TME in PDAC. For example, He et al (79) identified a typically

immunosuppressive subpopulation of formyl peptide receptor 2 (+) M2

macrophages that is specifically enriched in PDAC lesions from

female patients. These tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), induced

by estrogen, were associated with T cell exhaustion, reduced immune

cell infiltration and poorer survival in women, suggesting a

sex-specific immunosuppressive mechanism. In contrast to these

findings, a recent study reported that female patients with PDAC

exhibit higher levels of stromal biomarkers and increased tumor

stiffness, both of which were associated with longer survival

(80). The researchers further

showed that estrogen signaling shapes the TME by driving

cancer-associated fibroblasts toward a more tumor-suppressive

phenotype (80). However, these

estrogen-related effects were mediated not by systemic hormones but

by locally produced estrogens within the tumor tissue and therefore

do not fully explain the survival differences observed between

women and men (80). In another

study investigating patients with treatment-naive PDAC, women

exhibited elevated circulating levels of C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand (CXCL)9, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-13, supporting the notion

of enhanced systemic immune activation in women (81).

Sex differences may also impact immune responses to

chemotherapy. In a recent study by van Eijck et al (82), female sex was an independent

prognostic factor for 5-year OS in patients with localized PDAC

treated with neoadjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy followed by

surgery (43% OS in females vs. 22% in males). Notably, after

neoadjuvant therapy, the TME in female patients showed fewer

immunosuppressive M2 macrophages (CD163+MRC1) and a

distinct transcriptomic profile with higher expression of

CXCL10 and CXCL11 and lower levels of CCL2 and

IL-34, suggesting an enhanced antitumor immune response

(82). Although data on sex

differences in immune responses in PDAC remain limited and

potentially confounded by complex interactions among hormones,

drugs and genetics, current evidence suggests that women may

exhibit a more immunosuppressive TME characterized by a higher

abundance of estrogen-influenced immunosuppressive macrophages,

contrary to the expected higher immune activation in women.

Notably, gemcitabine appears to induce greater macrophage

plasticity in women, indicating a potential pathway for immune

activation. Together, these observations highlight that sex and sex

hormones uniquely shape immune activity in the TME and modulate

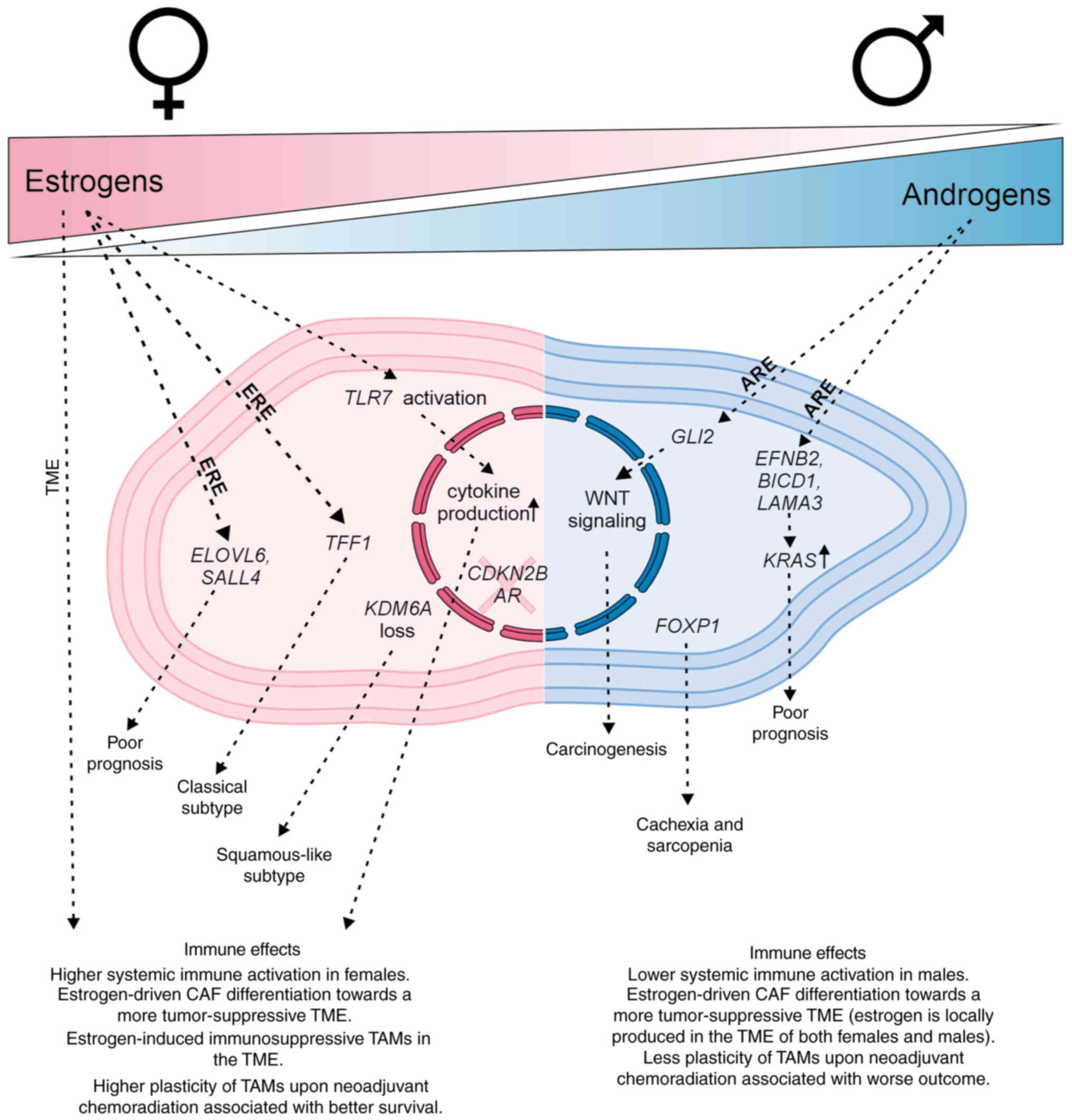

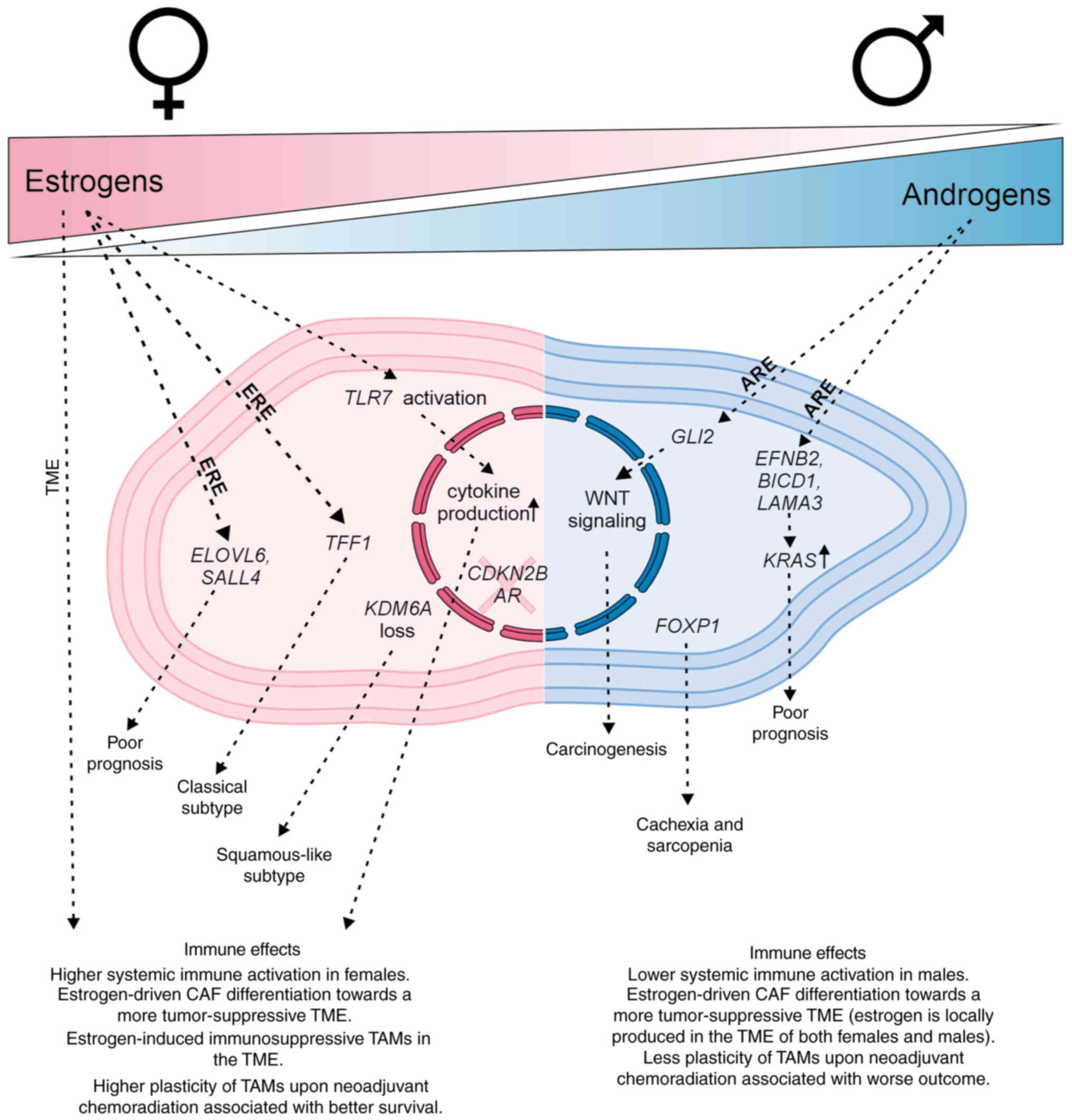

responses to chemotherapy. Fig. 1

summarizes sex-related hormonal and genetic differences in PDAC,

highlighting the distinct roles of estrogens and androgens in

shaping tumor biology, immune responses and the TME in women and

men. Although immune-targeted therapies have shown limited success

in PDAC, emerging approaches such as neoantigen vaccination show

promise and may enhance immune-based treatment strategies (83). Accounting for sex-specific immune

regulation will therefore be critical as immunotherapies for PDAC

continue to advance.

| Figure 1Overview of sex-related hormonal and

genetic differences for PDAC. Estrogens significantly shape immune

functions, including innate immune responsiveness through TLRs and

the regulation of cytokine production. In PDAC, estrogens influence

transcriptional subtypes and further modulate the TME by promoting

the differentiation of CAFs toward a more tumor-suppressive

phenotype. Conversely, estrogens can also affect TAMs, driving them

toward a more immunosuppressive state. Notably, TAMs in women show

greater plasticity following neoadjuvant chemoradiation with

gemcitabine, which is associated with improved survival. By

contrast, androgens are linked to carcinogenesis and cachexia.

Notably, the effects of estrogens are not restricted to women; men

can also produce estrogen locally within the tumor tissue,

similarly promoting CAF differentiation toward a more

tumor-suppressive TME. PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; TME,

tissue microenvironment; ERE, estrogen response element; ARE,

androgen response element; AR, androgen receptor; TAM,

tumor-associated macrophage; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblasts;

TLR, Toll-like receptor; CDKN2B, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor

2B; TFF1, trefoil factor 1; KDM6A, lysine demethylase 6A; GLI2,

zinc finger protein 2; EFNB2, ephrin B2; BICD1, bicaudal D cargo

adaptor 1; LAMA3, laminin α3; ELOVL6,

elongation-of-very-long-chain-fatty acids 6; SALL4, Sal-like

protein 4. |

Tumor microbiota

Research on tumor microbiota has provided compelling

insights into its role in modulating the TME (84) and shaping systemic immune

responses, thereby influencing various diseases (85). In PDAC, the intratumoral

microbiota significantly impacts prognosis and therapeutic

efficacy, most notably by altering the TME (86), influencing tumor phenotype

(87), and degrading

chemotherapeutic agents such as gemcitabine (88,89). However, the influence of sex on

the tumor microbiota remains unclear. To date, few studies have

assessed bacterial species distribution by sex in patients with

PDAC and none have reported significant differences (86,90). This is further supported by

comparable rates of bacterial colonization in tumor tissue across

sexes (91), as well as a similar

prevalence of intratumoral gram-negative bacteria in male and

female patients (89). Although

it should be noted that none of the studies chose the investigation

of sex-specific differences as their primary endpoint.

Nonetheless, sex-specific differences in the oral

and gut microbiota have been reported in patients with PDAC

compared with healthy controls (92). These differences are also evident

in murine models, where a recent study identified increased

abundance of Ligilactobacillus and Acetatifactor in

female mice with PDAC (93).

While intriguing, the implications of these findings for immune

modulation or tumor progression remain unclear. Further

illustrating the role of microbiota in therapy, antibiotic

administration has been shown to enhance gemcitabine efficacy in

advanced PDAC (94), although

this effect was not associated with patient sex. While current

evidence does not show consistent sex-based differences in the

tumor microbiota of PDAC, emerging findings in gut and oral

microbiomes, as well as in preclinical models, underscore the need

for further investigation. Understanding how sex may modulate the

microbiome-immune-tumor axis could open new avenues for

personalized therapeutic strategies.

Biomarkers and genetics

Serum Biomarkers

The most commonly used biomarker for PDAC is

carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), although its specificity and

sensitivity remain limited (95).

Few studies have examined sex-specific differences and results are

inconsistent. A study reported more men (77.3%) with elevated

CA19-9 serum levels than women (66.7%) (96), although the clinical significance

of this difference remains unclear. However, several novel

biomarkers that are not used in clinical practice have shown

sex-based differences in expression patterns. For example, tissue

inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) has been shown to be

associated with liver metastases and poorer survival specifically

in male patients, a finding supported by mouse models showing

earlier metastasis with higher TIMP1 levels in males (97). In addition, thymidine kinase (TK)

levels have been reported to be higher in men: In one study, 21 men

vs. 9 women had TK levels above the median, while low TK levels

showed no sex difference (98).

Moreover, the serum marker adiponectin has been shown to be

associated with shorter survival in female patients only (99). These findings indicate that

certain biomarkers may have sex-specific prognostic value, although

none are currently used in clinical routine, to the best of our

knowledge. While some sex-related differences have been reported,

most data remain exploratory and lack consistent validation. The

continued absence of reliable biomarkers in PDAC remains a major

challenge for early detection and personalized therapy,

underscoring the need for large, well-designed studies that

systematically incorporate sex as a biological variable.

Genetic alterations

The four major driver mutations in PDAC affecting

KRAS, CDKN2A, TP53 and SMAD4 occur at similar

frequencies in both male and female patients (100,101). However, other tumor-related

genes show sex-specific mutation patterns; for example, alterations

in CDKN2B and the androgen receptor (AR) gene are

more frequently observed in female patients (100). Additionally, AR and estrogen

receptor binding sites in promoter regions contribute to distinct

sex-specific gene expression patterns in PDAC (102). A study found that among all

upregulated genes in male PDAC samples, 24 contained androgen

response elements (AREs), including EFNB2, BICD1 and

LAMA3, which strongly correlate with KRAS expression,

as well as GLI2, a key transcription factor involved in

carcinogenesis. These ARE-regulated genes in men are enriched in

tumor-related pathways, such as axon guidance and extracellular

matrix components, and are associated with poorer survival. By

contrast, among all genes upregulated in female PDAC samples

compared with normal tissue, only 3 genes, ELOVL6,

SALL4 and TFF1, are upregulated by estrogen response

elements. Overall, this suggests that AR-driven transcription plays

a more dominant and functionally relevant role in male PDAC biology

(102), while these sex-specific

molecular effects do not appear to be linked to differential

activity in the estrogen or pregnenolone pathways (103). Furthermore, no sex-specific

differences were described for single nucleotide polymorphisms

(SNPs) of DNA repair genes (104), although other SNPs had

sex-specific effects. For instance, the leptin receptor SNP

rs11585329 is associated with improved survival in men (99), while the APC I1307K variant

correlates with improved outcomes in women (74). While these findings expand our

understanding of sex-specific genomic features in PDAC, most

evidence is derived from retrospective or database-driven analyses

with limited functional validation. Linking these alterations to

biological function and therapeutic vulnerability will be crucial

to translate genomic sex differences into clinical relevance.

Transcriptional and epigenetic

regulation

Notably, the expression of certain transcription

factors contributes to sex-specific differences in tumor biology.

For example, the transcription factor Kaiso has been linked to

increased tumor invasiveness and poorer prognosis in male patients

(105). Additionally, the

transcription factors FoxP1 and activin have been associated with

the development of cachexia and sarcopenia, which appear to affect

male patients with PDAC more severely (106,107). However, findings on sex-specific

molecular tumor subtypes based on transcription profiles remain

inconsistent. Some studies suggest a higher prevalence of the more

aggressive quasi-mesenchymal or basal-like subtypes in men with

resected PDAC, potentially explaining poorer outcomes (108,109). By contrast, other studies report

no significant sex-based differences in gene expression signatures

used to predict treatment response to gemcitabine and FOLFIRINOX

(110,111). In the realm of epigenetics,

evidence indicates that loss of the histone demethylase, lysine

demethylase 6A (KDM6A), induces a squamous-like, metastatic PDAC

subtype specifically in female patients (112). In mouse models, male

Kdm6a-knockouts retained cancer protection through UTY, a

Y-chromosome-encoded homolog of Kdm6a, suggesting a sex-specific

regulation of chromatin remodeling (112). Hence, current evidence on

transcriptional and epigenetic regulation indicate a potential

impact of sex-differences, although data are scarce. Moreover,

variable study designs and limited validation contribute to

conflicting results. More specific approaches focusing on

sex-differences will be essential to clarify whether currently

described data represent true biological mechanisms or

context-dependent findings.

Histopathology and tissue biomarkers

Thus far and to the best of our knowledge, there is

no evidence that histopathological features, such as gland

formation, stromal density or entosis differ significantly between

male and female patients with PDAC (113-115). Similarly, the expression of

multiple diagnostic tissue biomarkers for PDAC, including CK7,

mucin-1 and SMAD4, does not show any sex-related variation in

histopathological examinations (Table IV). Due to retrospective

analyses, these results must be interpreted with caution. Up to

now, to the best of our knowledge, no clinically validated

sex-specific biomarkers for PDAC exist. Future studies

incorporating sex as a biological variable, particularly through

multi-omics approaches, are essential to uncover novel,

personalized biomarkers in PDAC.

| Table IVCurrent evidence on biomarkers in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Sex-specific differences. |

Table IV

Current evidence on biomarkers in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Sex-specific differences.

| First author,

year | Marker | Number of

patients | Clinical

situation | Detection

method | Results | Evidence

levela | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Song et al,

2022 | CK7 | 55 | Resected | IHC | No significant sex

difference | B | (116) |

| Xiong et al,

2022 | CK8 | 176 | Resected | mRNA

expression | No significant sex

difference | B | (117) |

| Qian et al,

2022 | MUC1 | 420 | Resected | IHC | No significant sex

difference | B | (118) |

| Ermiah et

al, 2022 | CEA | 123 | Resected and

advanced |

Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay | No significant sex

difference | B | (119) |

| Ermiah et

al, 2022 | CA19-9 | 123 | Resected and

advanced |

Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay | No significant sex

difference | B | (119) |

| Qian et al,

2022 | MUC5AC | 407 | Resected | IHC | No significant sex

difference | B | (118) |

| Sumiyoshi et

al, 2024 | CA19-9/DUPAN2 | 521 | Resected | Serum level | No significant sex

difference | B | (120) |

| Liang et al,

2017 | CA 125/ MUC16 | 160 | Resected | mRNA

expression | No significant sex

difference | B | (121) |

| Liang et al,

2017 | CA125/ MUC16 | 110 | Resected | IHC | No significant sex

difference | B | (121) |

| Xiao et al,

2014 | CDX2 | 61 | Resected | IHC | No significant sex

difference | B | (122) |

| Amal et al,

2024 | SMAD4 | 60 | Resected and

advanced | IHC | No significant sex

difference | B | (123) |

| Amal et al,

2024 | S100P | 60 | Resected and

advanced | IHC | No significant sex

difference | B | (123) |

Discussion and future perspectives

PDAC exhibits clear sex-based differences across

multiple dimensions, including incidence, risk factors, tumor

biology, immune response and treatment outcomes. While men have

historically shown higher incidence and mortality rates, the burden

of disease is rising disproportionately in women, particularly in

younger women, underscoring the importance of sex-specific

research. Rising pancreatic cancer rates in young women likely

result from a combination of sex-based biological vulnerability and

gender-related behavioral patterns. Biologically, women appear more

susceptible to the carcinogenic effects of obesity, central fat

distribution and early-life smoking. Socially and behaviorally,

earlier smoking initiation, rising obesity rates and increasing

risky alcohol consumption intensify exposure to these factors.

These combined dynamics highlight the need for targeted, sex- and

gender-specific risk-prevention strategies.

Biological sex influences not only disease

susceptibility but also chemotherapy pharmacokinetics, toxicity

profiles, immune responses, and potentially tumor progression

pathways. Women often experience greater treatment-related

toxicity, while men may face subtherapeutic dosing, indicating that

standardized treatment regimens may inadequately account for

sex-based variability. In this context, existing therapeutic

drug-monitoring approaches for agents such as 5-FU and irinotecan

represent an important but underused opportunity; when applied

consistently, these tools could facilitate more precise dose

optimization for both sexes and help mitigate sex-related

differences in exposure and toxicity. In addition, gender and

sociocultural factors influence how cancer treatment is received

and tolerated, yet they remain largely unaddressed in research and

clinical practice. Despite accumulating evidence, most large

clinical trials and translational studies still fail to stratify or

analyze outcomes by sex, leaving a critical gap in our ability to

personalize therapy.

To advance toward precision medicine in PDAC, sex

must be systematically incorporated as a biological variable at

every stage of research and clinical development. For instance,

future PDAC trials should include sex as a predefined

stratification factor or covariate in randomization and outcome

analyses, ensuring adequate statistical power for sex-specific

endpoints. Adaptive trial designs could prospectively test

sex-based differences in efficacy or toxicity. Pharmacokinetic and

pharmacogenomic studies should explicitly evaluate sex differences

in drug metabolism, immune response, tolerance and

exposure-response associations to guide individualized dosing

strategies. Furthermore, translational studies should report

biomarker performance and prognostic value separately for men and

women, to identify sex-specific predictive signatures of response

or resistance. Finally, in preclinical models, the development of

sex-balanced patient-derived organoids and murine models should be

considered for dissecting sex-dependent mechanisms and therapeutic

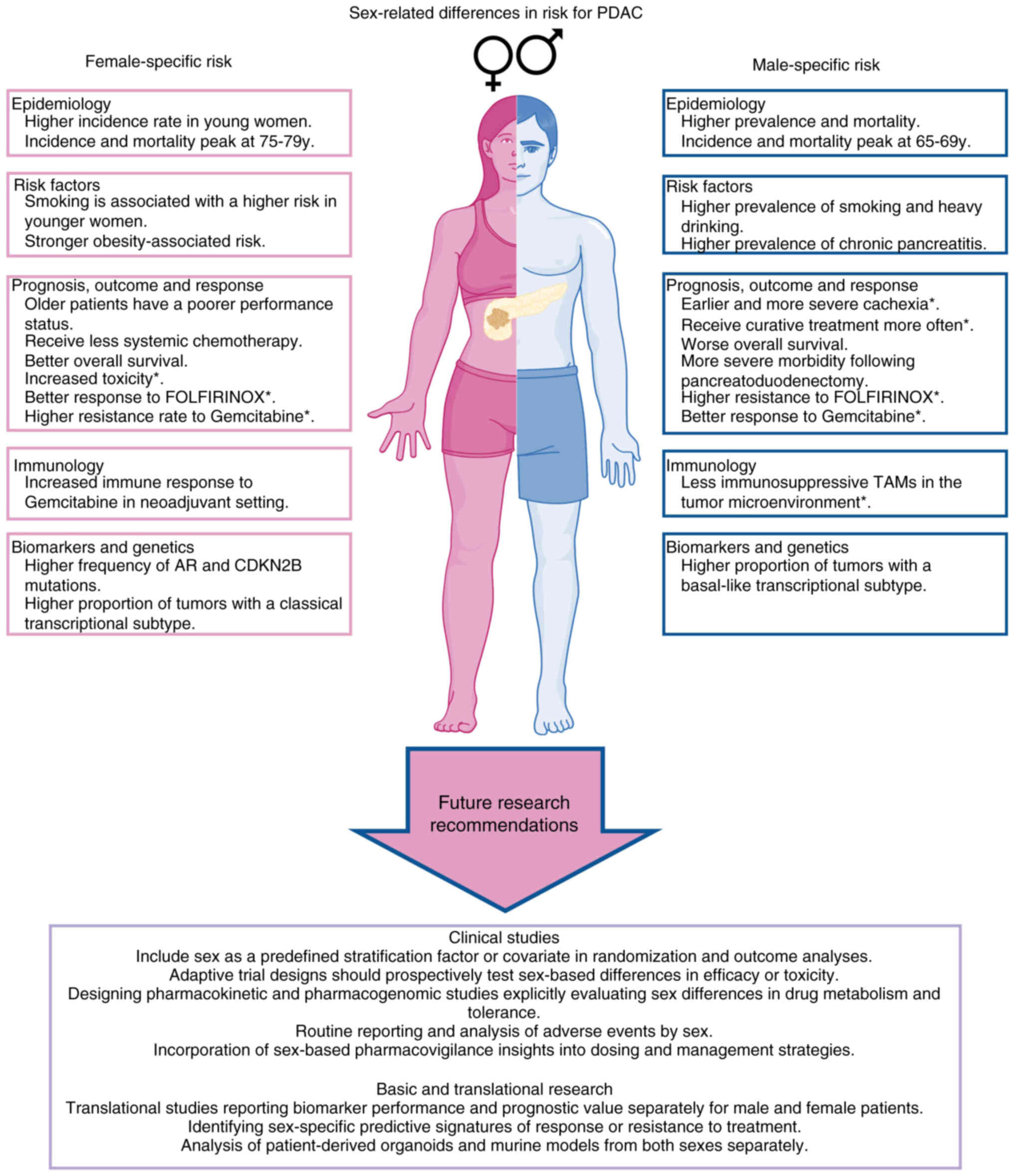

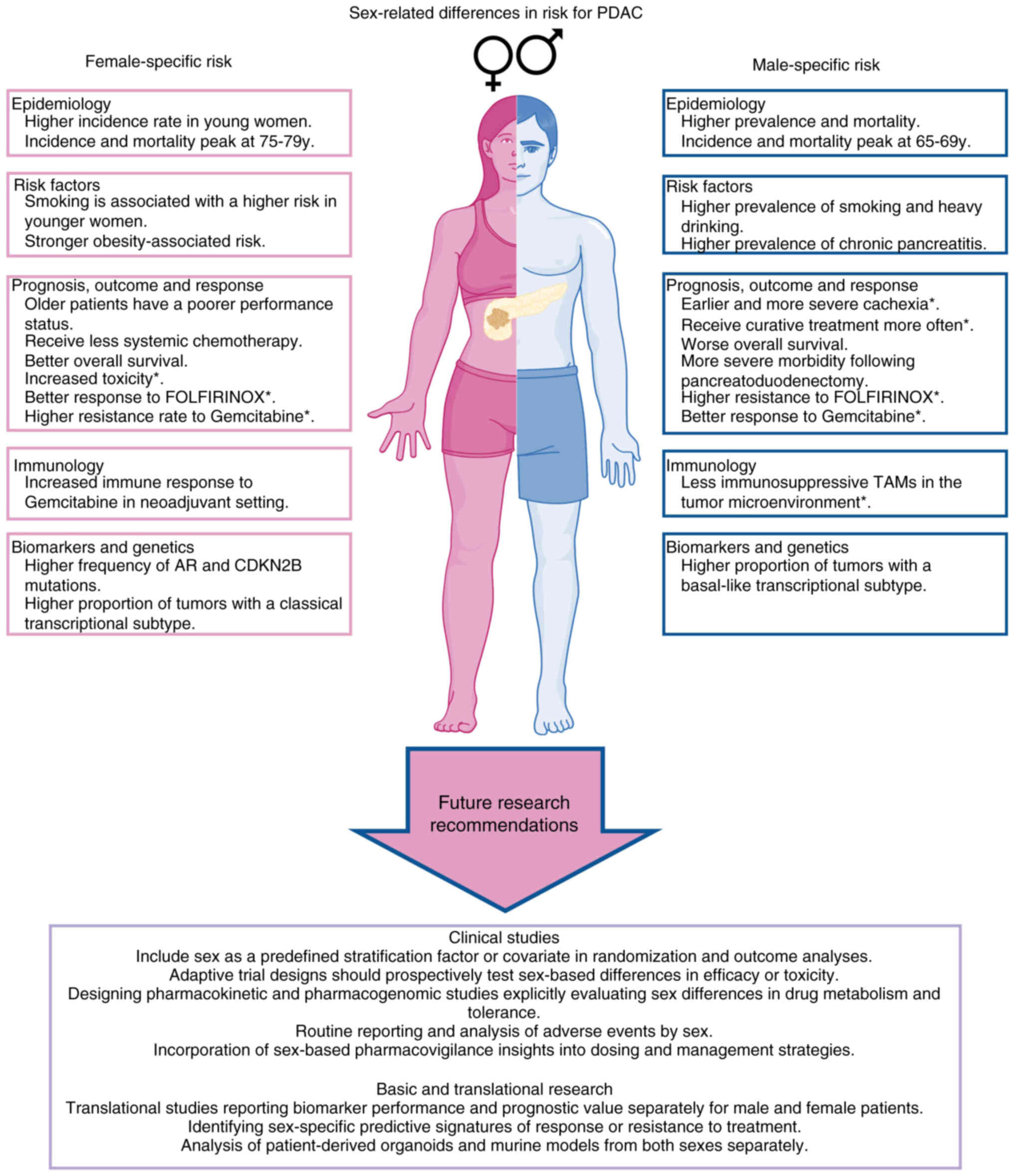

vulnerabilities (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2Structured overview of sex-related

differences in PDAC. The left panel summarizes aspects associated

with female patients, including epidemiological patterns, relevant

risk factors, prognostic considerations, immune-related features

and molecular characteristics. The right panel presents the

corresponding male-associated domains, following the same thematic

categories for direct comparison. The lower section synthesizes

overarching implications for future research, highlighting the need

to integrate sex as a biological variable in study design and

translational investigations. *trends have been shown,

but further studies are needed. PDAC, pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; AR, androgen

receptor; CDKN2B, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B. |

It should be acknowledged that current evidence is

largely derived from retrospective analyses with heterogeneous

metho dologies and limited adjustment for confounders.

Nevertheless, the present review highlights that sex-stratified

data remain underreported in PDAC trials, and that preclinical

systems rarely account for hormonal or chromosomal sex effects.

Addressing these limitations will require coordinated efforts to

standardize sex reporting, design prospective studies with balanced

enrollment and integrate multi-omic datasets to unravel biological

from sociocultural determinants of outcome. In conclusion,

addressing sex disparities in PDAC is not merely a scientific

objective but a prerequisite for equitable precision oncology.

Incorporating sex-based insights into risk assessment, biomarker

discovery and therapeutic design will be essential to optimize

treatment efficacy and minimize toxicity, ultimately moving toward

more personalized and effective care for all patients with

PDAC.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, drafting

and critical revision of this review. SR, EOG, LAM, DKZ and MG

performed the primary literature search and SR and EOG drafted the

initial version of the manuscript. IR, JML and DÖ served as mentors

and provided guidance, supervision and critical feedback throughout

the preparation of the manuscript. SR and MG designed and prepared

the tables and figures. DKZ, MG and LAM revised and finalized

individual sections of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and

edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

ORCIDs: Sophie Rauschenberg, 0009-0004-3408-1862;

Elisabeth Orgler-Gasche, 0000-0003-1904-2553; Didem Karakas Zeybek,

0000-0002-3781-6834; Ivonne Regel, 0000-0002-0206-4441; J.-Matthias

Löhr, 0000-0002-7647-198X; Daniel Öhlund, 0000-0002-5847-2778;

Michael Günther, 0009-0001-5091-5060; Lina Aguilera Munoz,

0000-0002-6317-8725.

Acknowledgments

This review was conducted as part of the

Pancreas2000 program, the postgraduate educational program of the

European Pancreas Club (EPC).

Funding

Not applicable.

References

|

1

|

American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts

& Figures 2025. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2025

|

|

2

|

Kaufman MR, Eschliman EL and Karver TS:

Differentiating sex and gender in health research to achieve gender

equity. Bull World Health Organ. 101:666–671. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes

PJ, Brinton RD, Carrero JJ, DeMeo DL, De Vries GJ, Epperson CN,

Govindan R, Klein SL, et al: Sex and gender: Modifiers of health,

disease, and medicine. Lancet. 396:565–582. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Delahousse J, Wagner AD, Borchmann S,

Adjei AA, Haanen J, Burgers F, Letsch A, Quaas A, Oertelt-Prigione

S, Özdemir BC, et al: Sex differences in the pharmacokinetics of

anticancer drugs: A systematic review. ESMO Open. 9:1040022024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sosinsky AZ, Rich-Edwards JW, Wiley A,

Wright K, Spagnolo PA and Joffe H: Enrollment of female

participants in United States drug and device phase 1-3 clinical

trials between 2016 and 2019. Contemp Clin Trials. 115:1067182022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wagner AD, Oertelt-Prigione S, Adjei A,

Buclin T, Cristina V, Csajka C, Coukos G, Dafni U, Dotto GP,

Ducreux M, et al: Gender medicine and oncology: Report and

consensus of an ESMO workshop. Ann Oncol. 30:1914–1924. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kim SE, Paik HY, Yoon H, Lee JE, Kim N and

Sung MK: Sex- and gender-specific disparities in colorectal cancer

risk. World J Gastroenterol. 21:5167–5175. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Abdel-Rahman O: Impact of sex on

chemotherapy toxicity and efficacy among patients with metastatic

colorectal cancer: Pooled analysis of 5 randomized trials. Clin

Colorectal Cancer. 18:110–115 e2. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ferlay JEM, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet

M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I and Bray F: Global

Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. International Agency for Research

on Cancer; Lyon: Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today2024.

|

|

10

|

Khalaf N, El-Serag HB, Abrams HR and

Thrift AP: Burden of pancreatic cancer: From epidemiology to

practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 19:876–884. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang S, Zheng R, Li J, Zeng H, Li L, Chen

R, Sun K, Han B, Bray F, Wei W and He J: Global, regional, and

national lifetime risks of developing and dying from

gastrointestinal cancers in 185 countries: A population-based

systematic analysis of GLOBOCAN. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

9:229–237. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

GBD 2017 Pancreatic Cancer Collaborators:

The global, regional, and national burden of pancreatic cancer and

its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories,

1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of disease

study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 4:934–947. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cavazzani A, Angelini C, Gregori D and

Cardone L: Cancer incidence (2000-2020) among individuals under 35:

An emerging sex disparity in oncology. BMC Med. 22:3632024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Huang J, Lok V, Ngai CH, Zhang L, Yuan J,

Lao XQ, Ng K, Chong C, Zheng ZJ and Wong MCS: Worldwide Burden of,

risk factors for, and trends in pancreatic cancer.

Gastroenterology. 160:744–754. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

ECIS-European Cancer Information System.

2025, Available from: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/explorer.php.

|

|

16

|

Lynch SM, Vrieling A, Lubin JH, Kraft P,

Mendelsohn JB, Hartge P, Canzian F, Steplowski E, Arslan AA, Gross

M, et al: Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: A pooled

analysis from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium. Am J

Epidemiol. 170:403–413. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gram IT, Park SY, Wilkens LR, Le Marchand

L and Setiawan VW: Smoking and pancreatic cancer: A sex-specific

analysis in the Multiethnic Cohort study. Cancer Causes Control.

34:89–100. 2023.

|

|

18

|

Bosetti C, Lucenteforte E, Silverman DT,

Petersen G, Bracci PM, Ji BT, Negri E, Li D, Risch HA, Olson SH, et

al: Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: An analysis from the

International pancreatic cancer case-control consortium (Panc4).

Ann Oncol. 23:1880–1888. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

19

|

Koyanagi YN, Ito H, Matsuo K, Sugawara Y,

Hidaka A, Sawada N, Wada K, Nagata C, Tamakoshi A, Lin Y, et al:

Smoking and pancreatic cancer incidence: A pooled analysis of 10

population-based cohort studies in Japan. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev. 28:1370–1378. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jiao L, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge

P, Pfeiffer RM, Park Y, Freedman DM, Gail MH, Alavanja MC, Albanes

D, Beane Freeman LE, et al: Body mass index, effect modifiers, and

risk of pancreatic cancer: A pooled study of seven prospective

cohorts. Cancer Causes Control. 21:1305–1314. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K

and Thun MJ: Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a

prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med.

348:1625–1638. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Arslan AA, Helzlsouer KJ, Kooperberg C,

Shu XO, Steplowski E, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Fuchs CS, Gross MD,

Jacobs EJ, Lacroix AZ, et al: Anthropometric measures, body mass

index, and pancreatic cancer: A pooled analysis from the pancreatic

cancer cohort consortium (PanScan). Arch Intern Med. 170:791–802.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Johansen D, Stocks T, Jonsson H, Lindkvist

B, Bjorge T, Concin H, Almquist M, Häggström C, Engeland A, Ulmer

H, et al: Metabolic factors and the risk of pancreatic cancer: A

prospective analysis of almost 580,000 men and women in the

Metabolic Syndrome and cancer project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers

Prev. 19:2307–2317. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Genkinger JM, Kitahara CM, Bernstein L,

Berrington de Gonzalez A, Brotzman M, Elena JW, Giles GG, Hartge P,

Singh PN, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, et al: Central adiposity, obesity

during early adulthood, and pancreatic cancer mortality in a pooled

analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol. 26:2257–2266. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mao Y, Tao M, Jia X, Xu H, Chen K, Tang H

and Li D: Effect of diabetes mellitus on survival in patients with

pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep.

5:171022015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mellenthin C, Balaban VD, Dugic A and

Cullati S: Risk factors for pancreatic cancer in patients with

new-onset diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers

(Basel). 14:46842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Song S, Wang B, Zhang X, Hao L, Hu X, Li Z

and Sun S: Long-term diabetes mellitus is associated with an

increased risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS One.

10:e01343212015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington

de Gonzalez A, Barzi F and Woodward M: Type-II diabetes and

pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer.

92:2076–2083. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lucenteforte E, La Vecchia C, Silverman D,

Petersen GM, Bracci PM, Ji BT, Bosetti C, Li D, Gallinger S, Miller

AB, et al: Alcohol consumption and pancreatic cancer: A pooled

analysis in the International pancreatic cancer case-control

consortium (PanC4). Ann Oncol. 23:374–382. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Genkinger JM, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE,

Bergkvist L, Bernstein L, van den Brandt PA, English DR,

Freudenheim JL, Fuchs CS, Giles GG, et al: Alcohol intake and

pancreatic cancer risk: A pooled analysis of fourteen cohort

studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 18:765–776. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jiao L, Silverman DT, Schairer C, Thiebaut

AC, Hollenbeck AR, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A and

Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ: Alcohol use and risk of pancreatic cancer:

The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 169:1043–1051.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Arab JP, Dunn W, Im G and Singal AK:

Changing landscape of alcohol-associated liver disease in younger

individuals, women, and ethnic minorities. Liver Int. 44:1537–1547.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Santos R, Coleman HG, Cairnduff V and

Kunzmann AT: Clinical prediction models for pancreatic cancer in

general and at-risk populations: A systematic review. Am J

Gastroenterol. 118:26–40. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Gandhi S, de la Fuente J, Murad MH and

Majumder S: Chronic pancreatitis is a risk factor for pancreatic

cancer, and incidence increases with duration of disease: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol.

13:e004632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kirkegard J, Mortensen FV and

Cronin-Fenton D: Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer risk: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol.

112:1366–1372. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ilic M, Milicic B and Ilic I: Association

between oral contraceptive use and pancreatic cancer risk: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol.

27:2643–2656. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Andersson G, Borgquist S and Jirstrom K:

Hormonal factors and pancreatic cancer risk in women: The Malmo

diet and cancer study. Int J Cancer. 143:52–62. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lee E, Horn-Ross PL, Rull RP, Neuhausen

SL, Anton-Culver H, Ursin G, Henderson KD and Bernstein L:

Reproductive factors, exogenous hormones, and pancreatic cancer

risk in the CTS. Am J Epidemiol. 178:1403–1413. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Prizment AE, Anderson KE, Hong CP and

Folsom AR: Pancreatic cancer incidence in relation to female

reproductive factors: Iowa women's health study. JOP. 8:16–27.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Duell EJ and Holly EA: Reproductive and

menstrual risk factors for pancreatic cancer: A population-based

study of San Francisco Bay Area women. Am J Epidemiol. 161:741–747.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Stevens RJ, Roddam AW, Green J, Pirie K,

Bull D, Reeves GK and Beral V; Million Women Study Collaborators:

Reproductive history and pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality

in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers

Prev. 18:1457–1460. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ioannou C, Ragia G, Balgkouranidou I,

Xenidis N, Amarantidis K, Koukaki T, Biziota E, Kakolyris S and

Manolopoulos VG: MTHFR c.665C>T guided fluoropyrimidine therapy

in cancer: Gender-dependent effect on dose requirements. Drug Metab

Pers Ther. 37:323–327. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, Lamarca

A, Seufferlein T, O'Reilly EM, Hackert T, Golan T, Prager G,

Haustermans K, et al: Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice

Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

34:987–1002. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Mueller F, Buchel B, Koberle D, Schurch S,

Pfister B, Krahenbuhl S, Froehlich TK, Largiader CR and Joerger M:

Gender-specific elimination of continuous-infusional 5-fluorouracil

in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: Results from a

prospective population pharmacokinetic study. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 71:361–370. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Milano G, Etienne MC, Cassuto-Viguier E,

Thyss A, Santini J, Frenay M, Renee N, Schneider M and Demard F:

Influence of sex and age on fluorouracil clearance. J Clin Oncol.

10:1171–1175. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bastian G, Barrail A and Urien S:

Population pharmacokinetics of oxaliplatin in patients with

metastatic cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 14:817–824. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Nikanjam M, Stewart CF, Takimoto CH,

Synold TW, Beaty O, Fouladi M and Capparelli EV: Population

pharmacokinetic analysis of oxaliplatin in adults and children

identifies important covariates for dosing. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 75:495–503. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Klein CE, Gupta E, Reid JM, Atherton PJ,

Sloan JA, Pitot HC, Ratain MJ and Kastrissios H: Population

pharmacokinetic model for irinotecan and two of its metabolites,

SN-38 and SN-38 glucuronide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 72:638–647. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Berg AK, Buckner JC, Galanis E, Jaeckle

KA, Ames MM and Reid JM: Quantification of the impact of

enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs on irinotecan pharmacokinetics

and SN-38 exposure. J Clin Pharmacol. 55:1303–1312. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chabot GG, Abigerges D, Catimel G, Culine

S, de Forni M, Extra JM, Mahjoubi M, Hérait P, Armand JP, Bugat R,

et al: Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of

irinotecan (CPT-11) and active metabolite SN-38 during phase I

trials. Ann Oncol. 6:141–151. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

De Francia S, Mancardi D, Berchialla P,

Armando T, Storto S, Allegra S, Soave G, Racca S, Chiara F,

Carnovale J, et al: Gender-specific side effects of chemotherapy in

pancreatic cancer patients. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 100:371–377.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kim J, Ji E, Jung K, Jung IH, Park J, Lee

JC, Kim JW, Hwang JH and Kim J: Gender differences in patients with

metastatic pancreatic cancer who received FOLFIRINOX. J Pers Med.

11:832021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Keum J, Lee HS, Kang H, Jo JH, Chung MJ,

Park JY, Park SW, Song SY and Bang S: Single-center risk factor

analysis for FOLFIRINOX associated febrile neutropenia in patients

with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 85:651–659.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Sugiyama E, Kaniwa N, Kim SR, Hasegawa R,

Saito Y, Ueno H, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Morizane C, Kondo S, et al:

Population pharmacokinetics of gemcitabine and its metabolite in

Japanese cancer patients: Impact of genetic polymorphisms. Clin

Pharmacokinet. 49:549–558. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Jiang X, Galettis P, Links M, Mitchell PL

and McLachlan AJ: Population pharmacokinetics of gemcitabine and

its metabolite in patients with cancer: Effect of oxaliplatin and

infusion rate. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 65:326–333. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lim HS, Bae KS, Jung JA, Noh YH, Hwang AK,

Jo YW, Hong YS, Kim K, Lee JL, Park SJ, et al: Predicting the

efficacy of an oral paclitaxel formulation (DHP107) through

modeling and simulation. Clin Ther. 37:402–417. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Joerger M, Kraff S, Huitema AD, Feiss G,

Moritz B, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH and Jaehde U: Evaluation of a

pharmacology-driven dosing algorithm of 3-weekly paclitaxel using

therapeutic drug monitoring: A pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic

simulation study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 51:607–617. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chen N, Li Y, Ye Y, Palmisano M, Chopra R

and Zhou S: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nab-paclitaxel

in patients with solid tumors: Disposition kinetics and

pharmacology distinct from solvent-based paclitaxel. J Clin

Pharmacol. 54:1097–1107. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Pijnappel EN, Schuurman M, Wagner AD, de

Vos-Geelen J, van der Geest LGM, de Groot JB, Koerkamp BG, de Hingh

IHJT, Homs MYV, Creemers GJ, et al: Sex, gender and age differences

in treatment allocation and survival of patients with metastatic

pancreatic cancer: A nationwide study. Front Oncol. 12:8397792022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Gehrels AM, Wagner AD, Besselink MG,

Verhoeven RHA, van Eijck CHJ, van Laarhoven HWM, Wilmink JW and van

der Geest LG; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group: Gender differences in

tumor characteristics, treatment allocation and survival in stage

I-III pancreatic cancer: A nationwide study. Eur J Cancer.

206:1141172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Olsson Hau S, Williamsson C, Andersson B,

Eberhard J and Jirstrom K: Sex and gender differences in treatment

intention, quality of life and performance status in the first 100

patients with periampullary cancer enrolled in the CHAMP study. BMC

Cancer. 23:3342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Williamsson C, Rystedt J and Andersson B:

An analysis of gender differences in treatment and outcome of

periampullary tumours in Sweden-A national cohort study. HPB

(Oxford). 23:847–853. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Pastrana Del Valle J, Mahvi DA,

Fairweather M, Wang J, Clancy TE, Ashley SW, Urman RD, Whang EE and

Gold JS: Associations of gender, race, and ethnicity with

disparities in short-term adverse outcomes after pancreatic

resection for cancer. J Surg Oncol. 125:646–657. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Lambert A, Jarlier M, Gourgou Bourgade S

and Conroy T: Response to FOLFIRINOX by gender in patients with

metastatic pancreatic cancer: Results from the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11

randomized trial. PLoS One. 12:e01832882017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Hohla F, Hopfinger G, Romeder F,

Rinnerthaler G, Bezan A, Stattner S, Hauser-Kronberger C, Ulmer H

and Greil R: Female gender may predict response to FOLFIRINOX in

patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: A single institution

retrospective review. Int J Oncol. 44:319–326. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Dunn SE, Perry WA and Klein SL: Mechanisms

and consequences of sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 20:37–55. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Klein SL and Flanagan KL: Sex differences

in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 16:626–638. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Ye Y, Jing Y, Li L, Mills GB, Diao L, Liu

H and Han L: Sex-associated molecular differences for cancer

immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 11:17792020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Weinstein Y, Ran S and Segal S:

Sex-associated differences in the regulation of immune responses

controlled by the MHC of the mouse. J Immunol. 132:656–661. 1984.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Griesbeck M, Ziegler S, Laffont S, Smith

N, Chauveau L, Tomezsko P, Sharei A, Kourjian G, Porichis F, Hart