Introduction

Healthy individuals are equipped with defense

mechanisms against bacterial overgrowth and the small intestine is

relatively sterile (1). When one of

those mechanisms is impaired, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

(SIBO) may occur. SIBO is usually caused by abnormal intestinal

structure, intestinal dysfunction and impaired intestinal mucosal

function (2). SIBO is a serious

condition associated with a number of diseases, which may severely

affect further treatment of the patients and compromise their

quality of life.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common

gastrointestinal malignant tumors. With the improvement of living

standards and changes in dietary habits, the incidence and

mortality of CRC have been continuously increasing in recent years

(3). Moreover, with the advances in

endoscopy and medical technology, the resection rate of CRC

patients has increased. Postoperative CRC patients are commonly

affected by symptoms such as unformed stools, constipation,

bloating and abdominalgia. However, remission may be achieved with

anti-SIBO treatments, such as bifid triple viable capsule and

compound lactobacillus acidophilus, which are administered to

regulate the intestinal flora based on the original treatment.

CRC and SIBO may exhibit overlapping symptoms.

Moreover, the postoperative changes in the anatomical structure of

the intestinal tract provides SIBO with breeding grounds in

postoperative CRC patients. Therefore, it is reasonable to

hypothesize that SIBO is likely to occur in such patients. On the

basis of this hypothesis, we investigated whether treatment for

SIBO may improve the digestive symptoms of postoperative CRC

patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

A total of 43 postoperative CRC patients, aged 38–83

years (26 men and 17 women), who were hospitalized at the

departments of Gastroenterology, General Surgery, Hepatobiliary

Surgery and Oncology of Qingdao Municipal Hospital between January,

2012 and January, 2014, were selected. The patients were diagnosed

with CRC through imaging examinations such as gastroscopy,

colonoscopy and barium meal for the entire digestive system, and

other accessory examinations, such as measurement of tumor markers.

The diagnoses were confirmed with histopathological examinations

following surgical removal of the tumors. All the patients signed

written informed consent forms for the examinations. Furthermore,

30 healthy individuals (16 men and 14 women), aged 24–62 years,

were recruited from the outpatient clinic and schools for the

control group.

All the investigated subjects were required to meet

the following criteria: i) No other conditions, such as diabetes,

thyroid diseases, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, irritable bowel

syndrome (IBS), or any other disease that may lead to poor

gastrointestinal motility, and no lactose intolerance; ii) no use

of antibiotics, antacids or probiotics over the last month; iii) no

history of treatment with hormones, antidepressants and opioids; no

long-term history of heavy smoking; iv) no colonoscopy or enema

within the last 4 weeks; v) no history of renal insufficiency or

infection.

All the procedures were performed under consensus

agreements and in accordance with the Ethics Review Committee of

Qingdao Municipal Hospital.

Glucose hydrogen breath test

(GHBT)

All the investigated subjects underwent GHBT (model:

HHBT-01; Shenzhen CNNC Headway Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). i)

Sedative hypnotics, smoking, and the consumption of cooked

wheat-containing foods, vegetables, fruits, bean products, dairy

products and other foods rich in cellulose, were not allowed one

day before the test; ii) rice was allowed as staple food, with meat

and eggs as non-staple foods on the day before the test, avoiding

overeating; iii) consumption of solid or liquid foods was not

allowed after 8:00 pm, to ensure a comparatively low value of

fasting breath hydrogen (FBH) on the morning of the test (12-h

fasting); iv) smoking was prohibited one day before and throughout

the test. Eating and drinking were also not allowed during the

test, as were strenuous exercise and sleeping. All the investigated

subjects were advised to brush their teeth carefully before the

test and were kept in a sitting position.

Experimental methods

Using the disposable gas mouth blowpipe, the

investigated subject exhaled slowly for as long as possible, with

the flow rate being controlled at 250 ml/min. When the first

exhalation was completed, the patients continued exhaling after

taking a breath, until the figures on the liquid-crystal display

screen stopped rising, which required ~70 sec. First, FBH was

measured. Subsequently, 50–80 g glucose plus 200–250 ml warm boiled

water was used as the substrate (the patients gargled after having

the substrate in order to minimize the effect of oral bacteria on

the test). The expiratory hydrogen concentration was measured every

20 min after taking the substrate for 2 h in total.

SIBO diagnostic criteria

SIBO was considered to be positive if the expiratory

hydrogen concentration had increased by >12 ppm after taking the

glucose substrate, and negative otherwise.

Treatment

Patients diagnosed as SIBO-positive were

continuously treated with oral rifaximin (1,200 mg/day) for 10

days. GHBT was performed again at the end of the treatment, to

investigate and analyze the changes in expiratory hydrogen

concentration and gastrointestinal symptoms score (GISS).

GISS

The visual analogue scale (VAS) was applied to all

patients to evaluate the symptoms of diarrhea, constipation,

bloating, abdominalgia, poor appetite and fever. The total score of

each item was defined as the overall GISS. The symptom scores were

compared separately between SIBO-positive and SIBO-negative

patients, SIBO-positive patients before and after treatment, and

SIBO eradicated and not eradicated groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was conducted

using SPSS v19.0 software (Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative data were

evaluated using the χ2 test and P<0.05 was considered

to indicate statistically significant differences. Two-sample

t-tests for a difference in mean and the Mann-Whitney U test of

rank sum test were performed to check the normality and homogeneity

of variance. P<0.05 was considered to to indicate statistically

significant differences.

Results

Prevalence of SIBO in postoperative

CRC patients

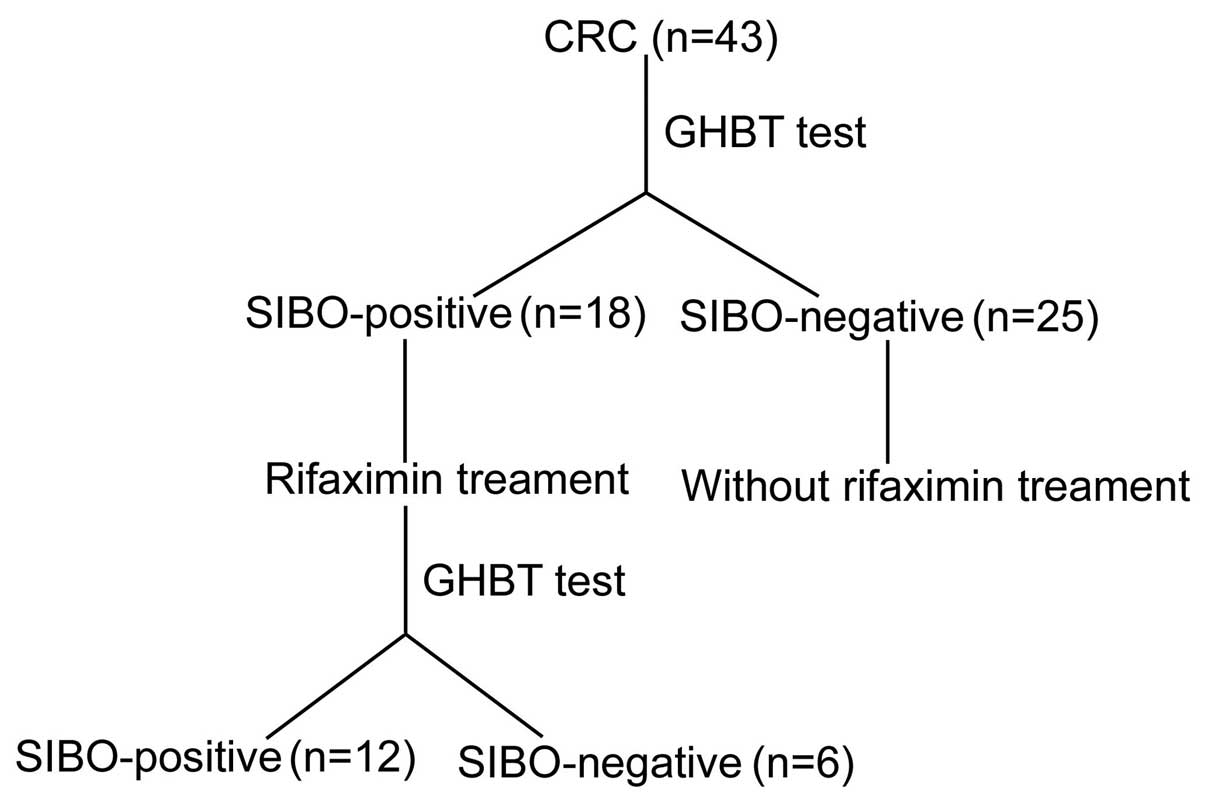

Among the 43 postoperative patients with CRC, 18

were diagnosed as SIBO-positive. However, among the 30 healthy

individuals in the control group, only 2 were found to be

SIBO-positive (41.86 vs. 6.67%; P<0.05). Comparing the CRC group

with the control group, the age difference of the investigated

subjects was statistically significant (P<0.05), while gender

was not (P>0.05) (Table I;

Fig. 1).

| Table I.Characteristics of study subjects and

prevalence of SIBO. |

Table I.

Characteristics of study subjects and

prevalence of SIBO.

|

| Groups |

| Prevalence |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristics | CRC (n=43) | Control (n=30) | P-value | SIBO-positive

(n=18) | SIBO-negative

(n=25) | P-value |

|---|

| SIBO prevalence,

% | 41.89 | 6.67 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Age, years ± SD | 63.67±11.09 | 41.30±13.84 | 0.000 | 68.72±10.15 | 60.04±10.45 | 0.010 |

| Male/female | 26/17 | 16/15 | 0.544 | 11/7 | 15/10 | 0.941 |

Digestive tract symptoms of SIBO

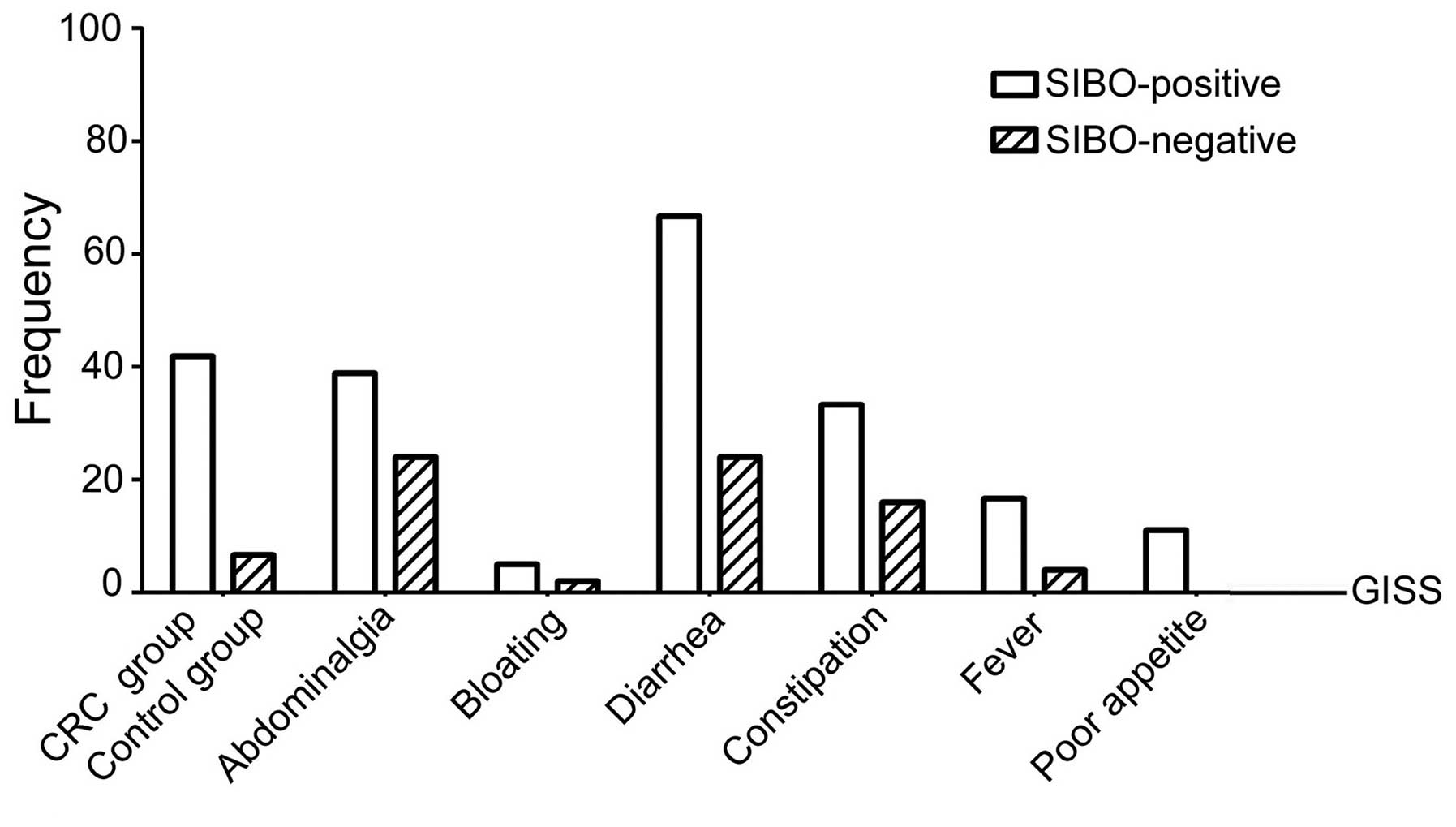

As regards the incidence of abdominalgia (34.88%),

bloating (32.56%), diarrhea (41.86%), constipation (23.26%), fever

(9.30%) and poor appetite (4.65%) among the 43 patients, the

incidence of diarrhea was the highest, followed by abdominalgia and

bloating (P<0.05) (Table II).

| Table II.Prevalence of gastrointestinal

symptoms. |

Table II.

Prevalence of gastrointestinal

symptoms.

|

|

| Prevalence, %

(n) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gastrointestinal

symptoms | Overall prevalence

(%) | SIBO-positive

(n=18) | SIBO-negative

(n=25) | P-value |

|---|

| Abdominalgia | 34.88 | 38.89 (7) | 32.00 (8) | 0.640 |

| Bloating | 32.56 | 50.00 (9) | 20.00 (5) | 0.038 |

| Diarrhea | 41.86 | 66.67 (12) | 24.00 (6) | 0.005 |

| Constipation | 23.26 | 33.33 (6) | 16.00 (4) | 0.336 |

| Fever | 9.30 | 16.67 (3) | 4.00 (1) | 0.380 |

| Poor appetite | 4.65 | 11.11 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.092 |

Among the 18 SIBO-positive patients, the difference

among symptoms was statistically significant (P<0.05). The

incidence of diarrhea was the highest, and it was significantly

higher compared with that among SIBO-negative patients (66.67 vs.

24.0%, respectively; P<0.05). Among the 25 SIBO-negative

patients, the difference among symptoms was statistically

significant (P<0.05) and the incidence of abdominalgia was the

highest, although the difference was not statistically significant

(32.0 vs. 38.89%; P>0.05). The differences among all the other

symptoms were not statistically significant (P>0.05) (Table II; Fig.

2).

VAS was applied to all the patients to calculate

GISS. The value of SIBO-positive patients was significantly higher

compared with that of SIBO-negative patients (8 vs. 4,

respectively; P<0.05). Among 6 gastrointestinal symptoms, every

score in the SIBO-positive patients was higher compared with that

in SIBO-negative patients, but only the difference in diarrhea was

statistically significant (7 vs. 5, respectively; P<0.05)

(Table III).

| Table III.GISS of SIBO-positive and

SIBO-negative groups prior to treatment. |

Table III.

GISS of SIBO-positive and

SIBO-negative groups prior to treatment.

|

| Median severity score

(range) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gastrointestinal

symptoms | SIBO-positive

(n=18) | SIBO-negative

(n=25) | P-value |

|---|

| Global GISS | 8 (6–14.25) | 4 (1–7) | 0.002 |

| Abdominalgia | 5 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 0.604 |

| Bloating | 6 (3–7.5) | 4 (2.5–5.5) | 0.249 |

| Diarrhea | 7 (4–8) | 5 (3–6.25) | 0.036 |

| Constipation | 5.5 (2.75–6.5) | 6.5 (4.5–7) | 0.386 |

| Fever | 6 (4–6) | 4 (4–4) | 0.317 |

| Poor appetite | 5.5 (3.75–4.5) | 0 (0–0) | 0.102 |

Effect of rifaximin on SIBO

SIBO-positive patients were continuously treated

with rifaximin (1,200 mg/day) for 10 days. GHBT was performed at

the end of the treatment course and GISS was calculated. Following

rifaximin treatment, the overall GISS was lower compared with that

prior to treatment (8 vs. 4, respectively; P<0.05). Only the

difference in diarrhea was statistically significant compared with

the values prior to treatment (7 vs. 3, respectively; P<0.05),

while no statistically significant differences were observed

regarding the rest of the symptoms (Table IV).

| Table IV.GISS of the SIBO-positive group before

and after treatment. |

Table IV.

GISS of the SIBO-positive group before

and after treatment.

|

| Median severity score

(range) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gastrointestinal

symptoms | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | P-value |

|---|

| Global GISS | 8 (6–14.25) | 4 (3–9.50) | 0.037 |

| Abdominalgia | 5 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 0.561 |

| Bloating | 6 (3–7.50) | 3 (1.50–5.50) | 0.120 |

| Diarrhea | 7 (4–8) | 3 (2–4) | 0.008 |

| Constipation | 5.5 (2.75–6.50) | 4 (2.50–5.80) | 0.450 |

| Fever | 6 (4–6) | 3 (3–3) | 0.102 |

| Poor appetite | 5.5 (3.75–4.50) | 6 (3–6) | 0.655 |

In addition, 6 of the 18 SIBO-positive patients

became SIBO-negative, with a negative conversion ratio of 33.33%.

No symptoms were experienced by the 2 SIBO-positive patients in the

control group; thus, no treatment was administered (Table V).

| Table V.Comparison between SIBO

turned-negative group and SIBO non-turned-negative group. |

Table V.

Comparison between SIBO

turned-negative group and SIBO non-turned-negative group.

| Global GISS | Pre-treatment | P-value | Post-treatment | P-value |

|---|

| Turned-negative

group | 8 (6–10.80) | 0.742 | 3 (1–4) | 0.023 |

| Non-turned-negative

group | 7.5 (6–26.3) |

| 7.5 (3.3–20.8) |

|

Discussion

In recent years, several studies demonstrated that

SIBO was correlated with several digestive system diseases or

symptoms, such as IBS, cirrhosis and acute severe pancreatitis.

Postoperative CRC patients also exhibited several digestive

problems (4,5). In this study, GHBT was performed in 43

postoperative patients with CRC and 30 healthy individuals. A total

of 41.86% postoperative CRC patients were found to have an abnormal

expiratory hydrogen concentration, while 6.67% of the control group

were found to be SIBO-positive. The overall symptoms of the CRC

patients with SIBO, particularly diarrhea, were improved following

rifaximin treatment, whereas 33.33% of the SIBO-positive patients

became SIBO-negative. Therefore, SIBO detection and treatment were

necessary for postoperative CRC patients.

It has been demonstrated that SIBO, as well as

bacteremia, sepsis and intestinal endotoxemia induced by SIBO, are

serious conditions associated with a number of diseases, which may

affect further treatment of the patients and severely compromise

their quality of life. The overgrown bacteria compete with the host

for dietary vitamin B12, interfere with the metabolism of bile

salts and affect the absorption of amino acids, thereby leading to

B12 hypovitaminosis, diarrhea and hypoalbuminemia (6). Furthermore, the overgrown small

intestinal bacteria may greatly increase the number of the bacteria

that adhere to the intestinal wall, subsequently producing a large

number of metabolites and toxins that may damage the structure of

the intestinal mucosa (7,8). Therefore, SIBO adversely affects the

intestinal tract through various factors, thereby aggravating

gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

It was found that the clinical symptoms of the

patients with SIBO were more severe compared with those of patients

without SIBO. In addition, among all SIBO-positive patients, the

incidence of diarrhea was the highest, followed by abdominalgia and

bloating. However, among SIBO-negative patients, the incidence of

abdominalgia was the highest, while that of diarrhea and bloating

was not as high. This difference in diarrhea scores was

statistically significant (P<0.05). The points mentioned above

indicate that patients with severe gastrointestinal symptoms are

more likely to have SIBO, particularly when diarrhea is the main

symptom. SIBO may aggravate the patients' gastrointestinal

symptoms, and treating SIBO improves such symptoms.

The symptoms of IBS may be significantly alleviated

through the application of probiotics or antibiotics to eradicate

SIBO. Previously reported data even demonstrated that the

gastrointestinal symptoms of some patients with IBS were completely

relieved following eradication of SIBO (9–12).

Rifaximin is a semi-synthetic antibiotic designed based on

rifamycin. It is a type of broad-spectrum oral bactericidal that

cannot be absorbed through the intestinal wall. Thus, there are no

known interactions with other drugs and its adverse reactions are

mild (13,14). Recently, an increasing number of

researchers verified the therapeutic effect of rifaximin on

intestinal diseases. A dose of 550 mg rifaximin three times a day

for 14 days has been used to treat patients with IBS, as reported

by Pimentel et al (15); they

found that 40.8% of the symptoms improved, compared with 31.2% of

IBS patients treated with placebo (P<0.05). In another study,

IBS patients treated with rifaximin for 14 days were followed up

and it was found that their symptoms of bloating, diarrhea and

abdominalgia were significantly improved within 3 months (16). The study of Biancone et al

(17) demonstrated that short-course

treatment with rifaximin for patients with Crohn's disease combined

with SIBO was effective. All those studies indicate that rifaximin

is effective against SIBO.

In our study, it was found that, after treatment

with rifaximin for 10 days, the GISS of 18 SIBO-positive patients

decreased (P<0.05), and 33.33% of those were no longer

SIBO-positive. The overall symptoms, particularly diarrhea, were

significantly alleviated following treatment for SIBO, proving that

treatment for SIBO is an effective measure for alleviating the

gastrointestinal symptoms of postoperative patients with CRC.

Therefore, the identification and timely treatment of SIBO are

crucial.

Although treatment with rifaximin for SIBO may

relieve some of the symptoms, it did not relieve all the

gastrointestinal symptoms, and the turned-negative rate was rather

low. Therefore, more effective agents for the eradication of SIBO

are urgently required.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported in part by a grant

from the Qingdao Science and Technology Bureau (grant no.

13-1-3-14-NSH to Ms. Lin Xu).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

FBH

|

fasting breath hydrogen

|

|

GHBT

|

glucose hydrogen breath test

|

|

GISS

|

gastrointestinal symptoms score

|

|

IBS

|

irritable bowel syndrome

|

|

SIBO

|

small intestinal bacterial

overgrowth

|

|

VAS

|

visual analogue scale

|

References

|

1

|

Bustillo I, Larson H and Saif MW: Small

intestine bacterial overgrowth: An underdiagnosed cause of diarrhea

in patients with pancreatic cancer. JOP. 10:576–578.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bures J, Cyrany J, Kohoutova D, Förstl M,

Rejchrt S, Kvetina J, Vorisek V and Kopacova M: Small intestinal

bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 16:2978–2990.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Durko L and Malecka-Panas E: Lifestyle

modifications and colorectal cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep.

10:45–54. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Madrid AM, Hurtado C, Gatica S, Chacón I,

Toyos A and Defilippi C: Endogenous ethanol production in patients

with liver cirrhosis, motor alteration and bacterial overgrowth.

Rev Med Chil. 130:1329–1334. 2002.(In Spanish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fisher D, Rajon D, Breitz H, Goris M,

Bolch W and Knox S: Dosimetry model for radioactivity localized to

intestinal mucosa. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 19:293–307. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fan X and Sellin JH: Review article: Small

intestinal bacterial overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption and gluten

intolerance as possible causes of chronic watery diarrhoea. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 29:1069–1077. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Husebye E, Hellström PM, Sundler F, Chen J

and Midtvedt T: Influence of microbial species on small intestinal

myoelectric activity and transit in germ-free rats. Am J Physiol

Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 280:G368–G380. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Passos MC, Serra J, Azpiroz F,

Tremolaterra F and Malagelada JR: Impaired reflex control of

intestinal gas transit in patients with abdominal bloating. Gut.

54:344–348. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Basseri RJ, Weitsman S, Barlow GM and

Pimentel M: Antibiotics for the treatment of irritable bowel

syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 7:455–493. 2011.

|

|

10

|

Jolley J: High-dose rifaximin treatment

alleviates global symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Exp

Gastroenterol. 4:43–48. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Marie I, Ducrotté P, Denis P, Menard JF

and Levesque H: Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic

sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 48:1314–1319. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tan AH, Mahadeva S, Thalha AM, Gibson PR,

Kiew CK, Yeat CM, Ng SW, Ang SP, Chow SK, Tan CT, et al: Small

intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson's disease.

Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 20:535–540. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Saadi M and McCallum RW: Rifaximin in

irritable bowel syndrome: Rationale, evidence and clinical use.

Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 4:71–75. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Karanje RV, Bhavsar YV, Jahagirdar KH and

Bhise KS: Formulation and development of extended-release micro

particulate drug delivery system of solubilized rifaximin. AAPS

PharmSciTech. 14:639–648. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pimentel M, Morales W, Chua K, Barlow G,

Weitsman S, Kim G, Amichai MM, Pokkunuri V, Rook E, Mathur R and

Marsh Z: Effects of rifaximin treatment and retreatment in

nonconstipated IBS subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 56:2067–2072. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Meyrat P, Safroneeva E and Schoepfer AM:

Rifaximin treatment for the irritable bowel syndrome with a

positive lactulose hydrogen breath test improves symptoms for at

least 3 months. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 36:1084–1093. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Biancone L, Vernia P, Agostini D, Ferrieri

A and Pallone F: Effect of rifaximin on intestinal bacterial

overgrowth in Crohn's disease as assessed by the

H2-glucose breath test. Curr Med Res Opin. 16:14–20.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|