Introduction

Angiomatous nasal polyps (ANPs) are an uncommon

subtype of inflammatory sinonasal polyp, accounting ~4-5% of all

nasal polyps (1). They are

characterized by significant vascular proliferation and

angiectasis, rendering them susceptible to vascular compromise,

which may lead to venous stasis, thrombosis and infarction

(2,3).

The clinical and radiological characteristics of

ANPs frequently resemble those of other sinonasal masses, such as

juvenile angiofibroma, inverted papilloma, vascular tumors such as

hemangioma, and malignant lesions. This resemblance complicates

diagnosis, highlighting the need for a comprehensive evaluation for

accurate differentiation (3-5).

Studies have highlighted specific imaging features on computed

tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans that

help distinguish ANPs from other sinonasal tumors, including

juvenile angiofibroma, inverted papilloma and malignancies

(4-6).

Recognition of these features is crucial to avoid unnecessary,

extensive surgical interventions and to guide appropriate clinical

management.

This study aimed to describe the clinical and

radiological features of six pathologically confirmed cases of

ANP.

Patients and methods

Patient recruitment

This retrospective study was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Chonnam National University Hwasun

Hospital (Hwasun, Korea; approval no. CNUHH-2023-127). It included

six patients diagnosed with ANP at Hwasun National University

Hospital (Hwasun, Korea) between December 2010 and May 2022. This

study included six patients with pathologically confirmed ANP.

Clinical and radiological features were reviewed and all patients

underwent endoscopic sinus surgery for tumor removal.

Imaging

CT was performed in all cases using standard

paranasal sinus protocols, while four patients also underwent

preoperative MRI. CT was conducted using a 64-slice

multidetector-row CT scanner (GE Healthcare). The scanning

parameters were as follows: Section thickness, 3 mm; beam pitch,

0.8; gantry rotation time, 0.5 sec; table speed, 30.7 2 mm per

rotation; reconstruction interval, 3 mm; tube voltage, 120 kV; and

tube current, 120-36 mA. The MRI was conducted on a 3.0T Siemens

MAGENTOM Skyra scanner (Siemens Healthineers), including

T1-weighted, T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced T1 sequences with 3

mm slice thickness. Sinus opacification was evaluated using the

Lund-Mackay scoring system (range: 0-24) (7). The Lund-Mackay scoring system, a

validated method for assessing sinus opacification, assigns a score

of 0 (no opacification), 1 (partial) or 2 (complete) to each of six

sinus regions on both sides, including the maxillary, anterior and

posterior ethmoid, frontal and sphenoid sinuses, and the

osteomeatal complex. The total score ranges from 0 to 24.

Information on the patient's symptoms, symptom duration, medical

history and imaging examinations before surgery was collected, as

well as data regarding follow-up observation and recurrence after

surgery. Clinical and imaging data were independently reviewed by

two rhinologic surgeons with 22 and 38 years' experience in

otorhinolaryngology and 1 radiologist with 22 years' experience in

head and neck radiology. Histologically, ANPs are characterized by

edematous and fibrotic stroma containing numerous dilated,

thin-walled blood vessels, often accompanied by areas of

infarction, hemorrhage, and thrombus formation (2,3). No

statistical analyses were performed due to the small sample size

and the descriptive nature of the study.

Follow-up

Postoperative follow-up was conducted one and two

weeks after the operation, followed by visits at three months, six

months and annually. Endoscopic examinations were performed at each

visit to monitor for recurrence.

Statistical analysis

Data management was performed using R version 4.2.3

(R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Values are expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical data of six patients were reviewed,

including sex, age, symptom duration, medical and surgical history,

lesion location and size, follow-up duration and recurrence.

Details are presented in Tables I

and II.

| Table ISummary of the six patients with

angiomatous nasal polyps. |

Table I

Summary of the six patients with

angiomatous nasal polyps.

| Variable | Value |

|---|

| Sex

(male/female) | 3:3 |

| Age, years | 42±28.4 (12-77) |

| Laterality

(left/right) | 4:2 |

| Symptom duration,

months | 10.8±4.5 (1-24) |

| Common symptoms | |

|

Nasal

obstruction | 6(100) |

|

Rhinorrhea | 5 (83.3) |

|

Epistaxis | 3(50) |

|

Hyposmia | 2 (33.3) |

|

Cheek

swelling | 1 (16.7) |

|

Epiphora | 1 (16.7) |

| Comorbidities | |

|

Hypertension | 1 (16.7) |

|

Smoking | 2 (33.3) |

|

Prior sinus

surgery | 2 (33.3) |

|

History of

trauma | 0 (0) |

| Endoscopic sinus

surgery approach | 6(100) |

| Tumor size, cm | 3.57±0.8

(2.7-5.0) |

| Follow-up duration,

months | 63.5±17.4

(15-132) |

| Recurrence | 0 (0) |

| Origin site | |

|

Maxillary

sinus | 4 |

|

Middle

turbinate | 1 |

|

Superior

turbinate | 1 |

| Lund-Mackay

score | 11.5±2.5 (5-20) |

| Table IIClinical characteristics of six

patients with angiomatous nasal polyps. |

Table II

Clinical characteristics of six

patients with angiomatous nasal polyps.

| Patient no. | Sex | Age, years | Side | Duration of symptoms,

months | Symptoms Nasal

obstruction | Epistaxis | Rhinorrhea | Hyposmia | Visual

disturbance | Cheek swelling | Epiphora | History | Trauma or

surgery | CT | MRI | Mass size, cm | FU duration,

months | Recurrence |

|---|

| 1 | F | 22 | Left | 24 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | None | None | Y | Y | 3.6 | 52 | N |

| 2 | M | 68 | Left | 1 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | None | Sinus surgery 30 yrs

ago | Y | Y | 2.7 | 132 | N |

| 3 | M | 17 | Left | 12 | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | None | Sinus surgery 1 yr

ago | Y | Y | 3.3 | 48 | N |

| 4 | M | 56 | Right | 3 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | HTN | None | Y | N | 2.7 | 96 | N |

| 5 | F | 12 | Left | 1 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | None | None | Y | N | 4.1 | 15 | N |

| 6 | F | 77 | Right | 24 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | None | None | Y | Y | 5.0 | 38 | N |

The cohort consisted of three men (50%) and three

women (50%) aged 12-77 years (mean: 42±28.4 years). All patients

had unilateral lesions, with four on the left (66.7%) and two on

the right (33.3%), and no contralateral sinonasal involvement.

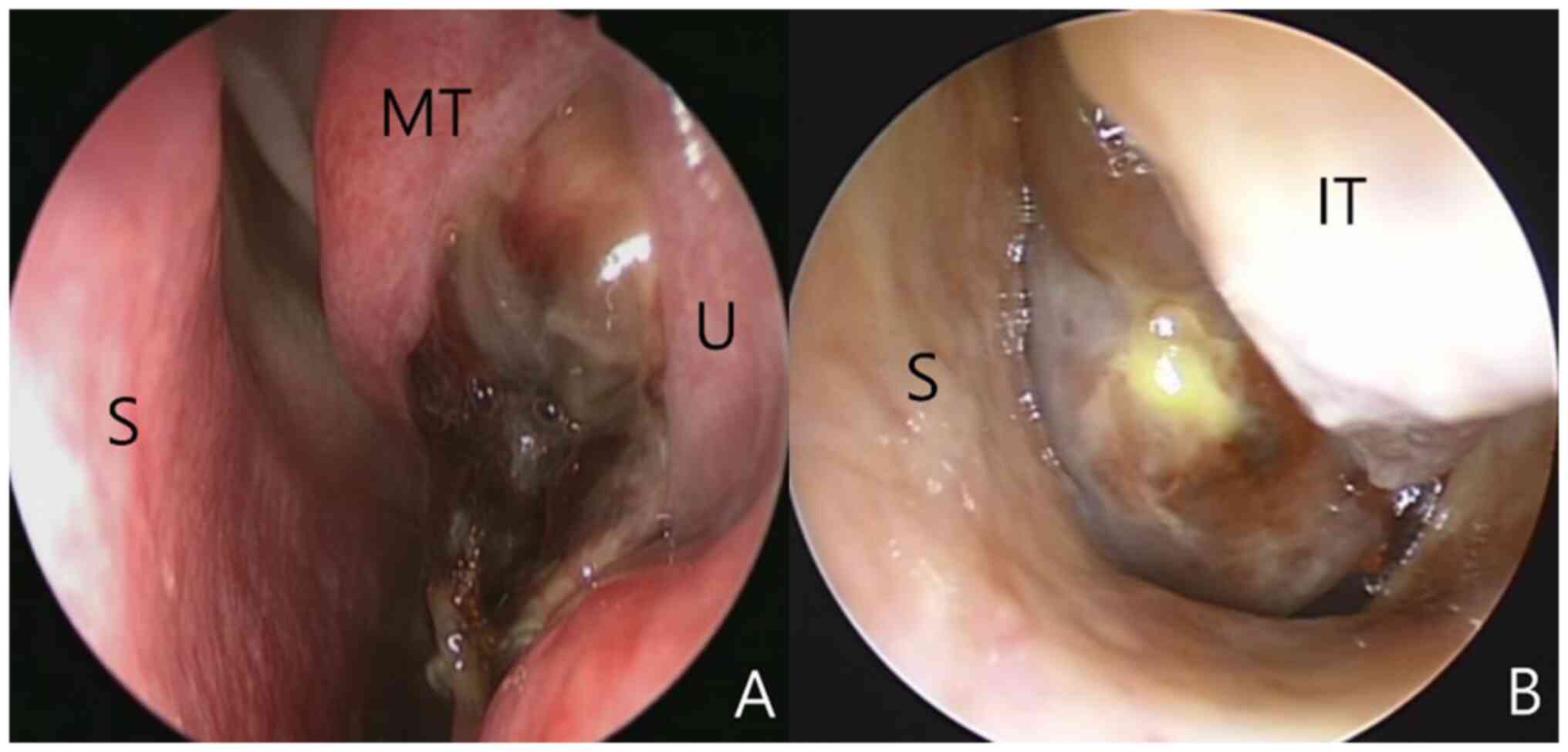

Endoscopic examination revealed polypoid masses with necrotic

changes in the nasal cavity (Fig.

1). Nasal obstruction was the most common symptom, present in

all cases. Rhinorrhea occurred in five patients (83.3%), followed

by epistaxis (n=3, 50%), hyposmia (n=2, 33.3%), and cheek swelling

and epiphora (each n=1, 16.7%). None of the patients experienced

any visual disturbances. The symptoms lasted 1 to 24 months (mean:

10.8±4.5 months). One patient had hypertension (16.7%) and two were

smokers (33.3%). Furthermore, two patients had prior endoscopic

sinus surgery (33.3%), though none had a history of trauma. All

patients underwent endoscopic sinus surgery for polyp removal.

Tumor sizes ranged from 2.7 to 5.0 cm (mean: 3.57±0.8 cm).

Postoperative follow-up included routine endoscopic examinations to

evaluate recurrence. The mean follow-up duration was 63.5±17.4

months (range: 15-132 months), with no recurrences observed.

CT findings

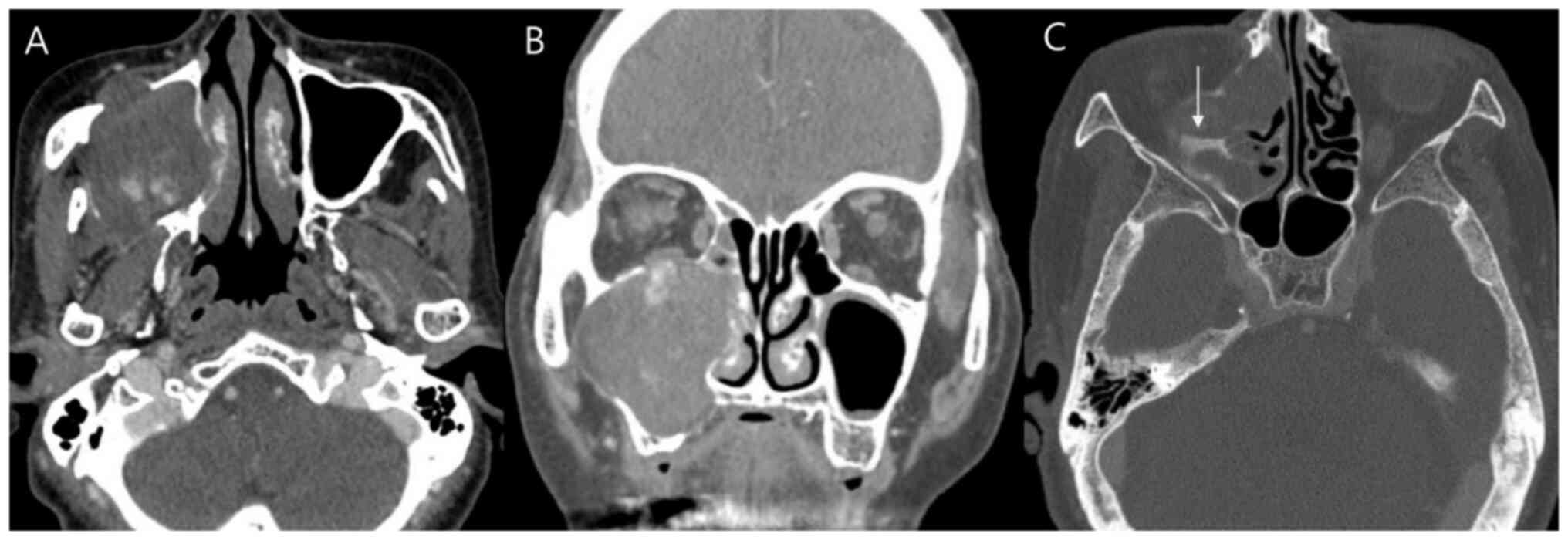

Preoperative contrast-enhanced CT scans were

performed for all six patients. The imaging characteristics are

summarized in Tables I and

III. The maxillary sinus was the

most common site of origin (n=4, 66.7%; representative case

presented in Fig. 2), followed by

the middle turbinate and superior turbinate (each n=1, 16.7%). The

mean Lund-Mackay score was 11.5±2.5 (range: 5-20). All cases

featured involvement of the nasal cavity, osteomeatal complex,

posterior choana and ipsilateral ethmoid sinus. The maxillary sinus

was affected in four cases (66.7%), while the sphenoid sinus was

involved in one case (16.7%); no frontal sinus involvement was

observed. One lesion extended into the nasopharynx (16.7%), two

involved the orbital floor and one reached the infratemporal fossa

(16.7%).

| Table IIICT findings in six cases of

angiomatous nasal polyp. |

Table III

CT findings in six cases of

angiomatous nasal polyp.

| Patient no. | Origin | LM score | Maxillary sinus | Ethmoid sinus | Sphenoid sinus | Frontal sinus | OMC | Nasal cavity | Posterior choana | Nph | Orbit floor | Infratemporal

fossa | Bone change | Homogeneity | Contrast

enhancement |

|---|

| 1 | Maxillary

sinus | 18 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Expansile

remodeling | Heterogeneous | Y |

| 2 | Middle

turbinate | 5 | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | None | Heterogeneous | Y |

| 3 | Maxillary

sinus | 5 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Expansile

remodeling, Hyperostosis | Heterogeneous | Y |

| 4 | Superior

turbinate | 20 | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Expansile

remodeling | Heterogeneous | N |

| 5 | Maxillary

sinus | 10 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Expansile

remodeling, Bony destruction | Heterogeneous | Y |

| 6 | Maxillary

sinus | 11 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Expansile

remodeling, Bony destruction, Hyperostosis | Heterogeneous | Y |

All lesions exhibited heterogeneous density on CT.

Contrast enhancement was seen in five cases (83.3%), while one

lesion showed no enhancement (16.7%). Bony changes were observed in

five patients (83.3%), including expansile remodeling (n=5, 83.3%),

hyperostosis (n=2, 33.3%) and bony destruction (n=2, 33.3%). Only

one patient showed no bony alteration.

MRI findings

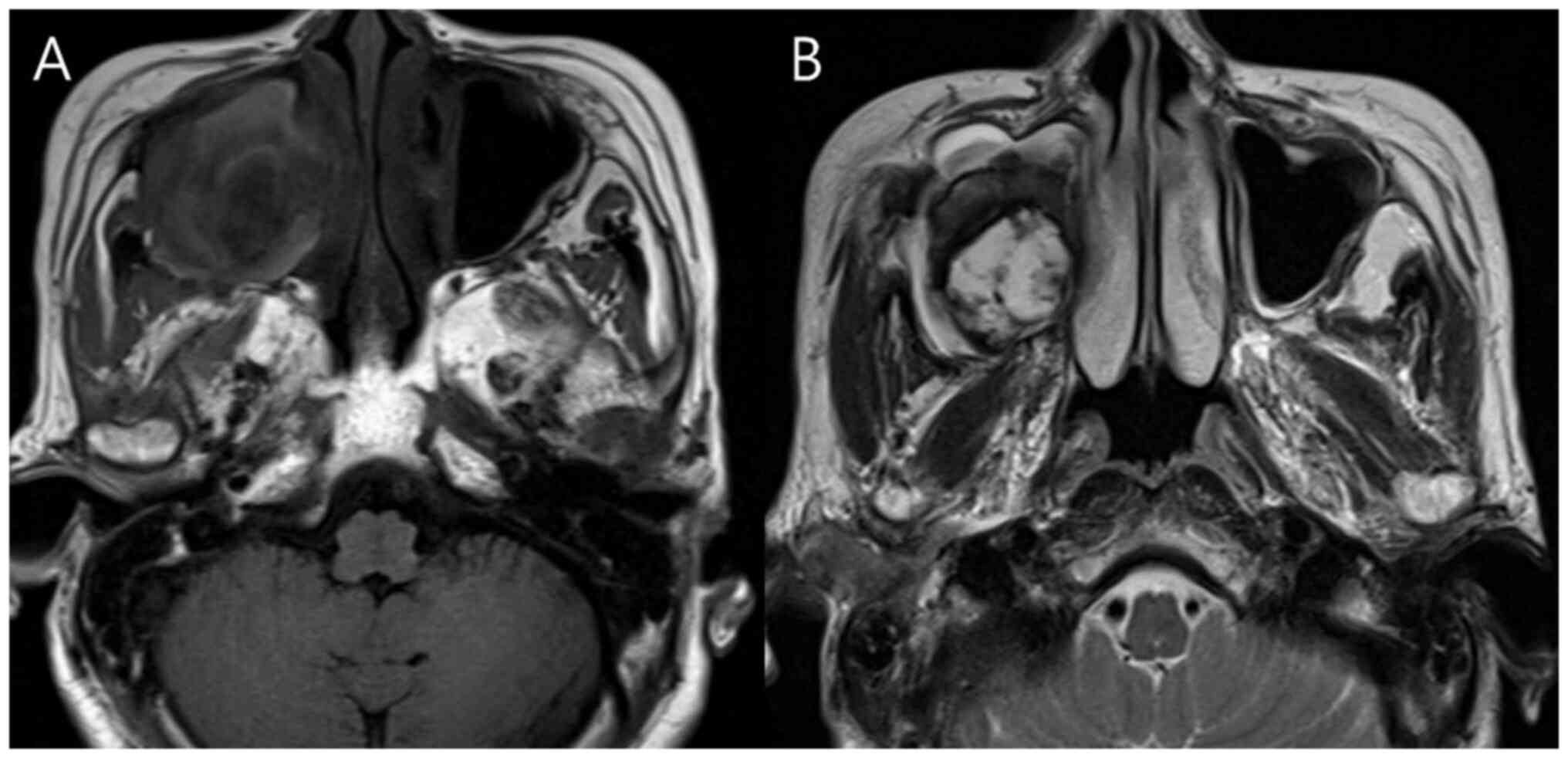

A total of four of the six patients (66.6%)

underwent additional MRI to evaluate suspected sinonasal malignancy

(representative case presented in Fig.

3). All four cases exhibited mild hyperintense signals on

T1-weighted images and heterogeneous hyperintense signals on

T2-weighted images. A peripheral hypointense rim on T2-weighted

images was noted in three patients (75%). Detailed MRI imaging

findings are described in Tables I

and IV.

| Table IVMagnetic resonance imaging findings

in four cases of angiomatous nasal polyps. |

Table IV

Magnetic resonance imaging findings

in four cases of angiomatous nasal polyps.

| Patient no. | T1-weighted

image | T2-weighted

image | Peripheral

hypointense rim in T2-weighted image | Enhancement |

|---|

| 1 | Mild

hyperintense | Heterogeneous

hyperintense | Yes | Heterogeneous |

| 2 | Mild

hyperintense | Heterogeneous

hyperintense | No | Heterogeneous |

| 3 | Mild

hyperintense | Heterogeneous

hyperintense | Yes | Heterogeneous |

| 6 | Mild

hyperintense | Heterogeneous

hyperintense | Yes | Heterogeneous |

Discussion

In the present study, only six patients with ANP

were encountered during the enrolment period. ANPs occurred equally

in men and women, with a mean patient age of 42±28.4 years. The

most common symptoms were nasal obstruction (n=6), rhinorrhea

(n=5), epistaxis (n=3), hyposmia (n=2), cheek swelling (n=1) and

epiphora (n=1). All patients reported symptomatic relief

postoperatively. However, improvement was evaluated clinically

during follow-up without using a standardized symptom-scoring tool,

which represents a limitation of this study. Polyp sizes ranged

from 2.7 to 5.0 cm, with a mean diameter of 3.57±0.8 cm. The

maxillary sinus was the most frequent site of origin, accounting

for 66.7% of cases, consistent with previous reports (3,4).

The precise pathogenesis of ANPs remains elusive,

but two prevailing theories have been proposed. One hypothesis

suggests that pedicle compression by adjacent nasal structures,

particularly when the polyp arises from the maxillary sinus or

nasal cavity, leads to stasis, ischemia and necrosis. Batsakis and

Sneige (2) proposed that sinonasal

polyps are susceptible to vascular compromise at key anatomical

sites, such as the polyp pedicle, sinus ostium, posterior end of

the inferior turbinate, posterior choana and nasopharynx. An

alternative theory attributes ANP formation to hematoma

development, which may result from operation, trauma, bleeding

disorders or other causes of hemorrhage. In this scenario, sinus

hypoventilation promotes blood pooling and stagnation, eventually

leading to organized hematoma and reactive tissue changes (2,5-9).

In all six cases in the present cohort, the polyps

were located in anatomically vulnerable regions. Four originated

near the maxillary sinus ostium, while the remaining two arose from

the superior and middle turbinates, where adjacent structures could

compress the pedicle. Furthermore, all polyps extended into the

posterior choana, contributing to the likelihood of vascular

compromise. This is the first reported case series of ANPs from our

institution, and two cases demonstrated atypical imaging features,

including the absence of a peripheral hypointense rim and subtle

bone remodeling. These findings support the first hypothesis,

suggesting the development of an inflammatory polyp as the initial

event, followed by compression-induced ischemia and necrosis.

Hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM) and

aspirin use may contribute to the pathophysiology of ANPs (10-12).

Elevated blood glucose and blood pressure can compromise blood

vessel integrity, increasing the risk of thrombosis and infarction.

While aspirin and other anticoagulants inhibit prostaglandin

synthesis, dilate blood vessels and prevent clot formation, they

may predispose to hemorrhage. In this study, only one patient had

HTN and none had DM or were on aspirin therapy. Therefore, no

significant association was observed between ANPs and HTN, DM or

aspirin use.

ANPs typically appear on CT as sinus-expanding

masses with heterogeneous density. Chronic inflammatory obstruction

may lead to bony changes such as destruction or hyperostosis

(5,6). However, these features are

non-specific to ANPs and can be seen in malignant and benign

sinonasal tumors, such as inverted papillomas, hemangiomas and

juvenile angiofibromas (13). In

the present study, CT revealed bony alterations in 83.3% of cases:

Expansile remodeling in five patients (83.3%), bony destruction in

two (33.3%) and hyperostosis in two (33.3%).

MRI has proven useful in distinguishing ANPs from

other lesions. Typically, ANPs show mild hyperintensity on

T1-weighted images and heterogeneous hyperintensity with a

peripheral hypointense rim on T2-weighted sequences. This rim is

often attributed to hemosiderin deposition from prior hemorrhage,

supporting the diagnostic value of MRI (5,13,14).

In the present study, all four cases with MRI data exhibited mild

hypointensity on T1-weighted images and marked heterogeneous

hyperintensity on T2-weighted images. A peripheral hypointense rim

was observed in three patients (75%), consistent with the typical

MRI findings for ANPs. The current findings are consistent with

previous reports (4,5), which described heterogeneous T2

signal intensity and peripheral hypointense rims as typical

findings. Unlike common nasal polyps, which are often bilateral and

exhibit minimal vascularity, ANPs tend to be unilateral, larger in

size and display prominent vascular features on imaging.

Furthermore, while inverted papillomas exhibit a cerebriform

pattern on MRI and sinonasal malignancies show aggressive bone

destruction, ANPs characteristically display benign remodeling with

the noted T2 hypointense rim (13). This study is limited by its small

sample size, retrospective design, incomplete MRI data for all

patients and absence of a control group, which may restrict broader

applicability.

Complete surgical excision remains the treatment of

choice for ANPs. All six patients underwent endoscopic sinus

surgery, with a mean follow-up of 63.5±17.4 months (range: 15-132

months). No recurrences were observed.

Recognizing the imaging and clinical features of

ANPs can help avoid misdiagnosis with more aggressive sinonasal

tumors, reduce unnecessary extensive surgical procedures and allow

for more targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, preoperative diagnosis of ANPs

remains challenging due to their clinical and radiological

resemblance of other sinonasal tumors. The CT characteristics, such

as expansile remodeling, bony destruction and hyperostosis, may

support the diagnosis but are not specific to ANPs. Conversely, MRI

offers more distinctive signal patterns, providing greater

diagnostic specificity. Incorporating MRI into the diagnostic

workflow may enhance the accuracy of differentiating ANPs from

other sinonasal lesions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DHL and SY conducted and designed the research, and

checked and confirmed the authenticity of the raw data. DHL, SY and

SCL performed the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the

manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation, table

design and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the

final version.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board (IRB) of Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (Hwasun,

Korea; approval no. CNUHH-2023-127). Patient consent for

publication was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature

of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Yfantis HG, Drachenberg CB, Gray W and

Papadimitriou JC: Angiectatic nasal polyps that clinically simulate

a malignant process: Report of 2 cases and review of the

literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 124:406–410. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Batsakis JG and Sneige N: Choanal and

angiomatous polyps of the sinonasal tract. Ann Otol Rhinol

Laryngol. 101:623–625. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sheahan P, Crotty PL, Hamilton S, Colreavy

M and McShane D: Infarcted angiomatous nasal polyps. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 262:225–230. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang YZ, Yang BT, Wang ZC, Song L and Xian

JF: MR evaluation of sinonasal angiomatous polyp. AJNR Am J

Neuroradiol. 33:767–772. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zou J, Man F, Deng K, Zheng Y, Hao D and

Xu W: CT and MR imaging findings of sinonasal angiomatous polyps.

Eur J Radiol. 83:545–551. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Unlu HH, Mutlu C, Ayhan S and Tarhan S:

Organized hematoma of the maxillary sinus mimicking tumor. Auris

Nasus Larynx. 28:253–255. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Hopkins C, Browne JP, Slack R, Lund VJ,

Topham J, Reeves BC, Copley LP, Brown P and van der Meulen JH:

Complications of surgery for nasal polyposis and chronic

rhinosinusitis: The results of a national audit in England and

Wales. Laryngoscope. 116:1494–1499. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lee HK, Smoker WR, Lee BJ, Kim SJ and Cho

KJ: Organized hematoma of the maxillary sinus: CT findings. AJR Am

J Roentgenol. 188:W370–W373. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yoon TM, Kim JH and Cho YB: Three cases of

organized hematoma of the maxillary sinus. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 263:823–826. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Tam YY, Wu CC, Lee TJ, Lin YY, Chen TD and

Huang CC: The clinicopathological features of sinonasal angiomatous

polyps. Int J Gen Med. 9:207–212. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Suryawanshi M, Saindani S, Bhatta S,

Suryawanshi R, Sawarkar S and Bhola G: Angiomatous nasal polyp: The

great emulator-a case report. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

74 (Suppl 3):S4730–S4733. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Dai LB, Zhou SH, Ruan LX and Zheng ZJ:

Correlation of computed tomography with pathological features in

angiomatous nasal polyps. PLoS One. 7(e53306)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kim EY, Kim HJ, Chung SK, Dhong HJ, Kim

HY, Yim YJ, Kim ST, Jeon P and Ko YH: Sinonasal organized hematoma:

CT and MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 29:1204–1208.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

De Vuysere S, Hermans R and Marchal G:

Sinochoanal polyp and its variant, the angiomatous polyp: MRI

findings. Eur Radiol. 11:55–58. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|