Introduction

Comprehensive cancer genome profiling (CGP) tests

were approved by the public health insurance (PHI) system in Japan

in June 2019, to identify genotype-matched therapies (GMTs) for

patients with advanced solid tumors who fail to respond to standard

therapies or for whom there are no appropriate standard therapies

(1). Cancer genetic medicine is

becoming part of routine clinical practice for patients with

metastatic prostate cancer. The PROfound trial was conducted in

patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

(mCRPC) who had deleterious alterations in prespecified genes

related to homologous recombination repair (2). Olaparib was listed in Japanese PHI on

December 2020 for patients with mCRPC with BRCA1 or

BRCA2 deleterious alterations, confirmed by

BRACAnalysis® or CGP tests using

FoundationOne® CDx (F1CDx) or FoundationOne®

Liquid CDx (F1LCDx) CGP. The results of the PROpel and TALAPRO-2

trials were also approved by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical

Devices Agency in Japan for patients with mCRPC with BRCA

deleterious alterations (3,4).

The advent of cancer genetic medicine is an

opportunity to recognize the importance of GMT for advanced

prostate cancer and to validate the existence of hereditary cancers

in patients with prostate cancer. When managing patients with

metastatic prostate cancer, physicians must have the ability to

interpret the results of CGP tests and identify appropriate GMTs

for those patients. In addition, the need for genetic counseling

(GC) has increasingly been recognized as the opportunity for CGP

tests has increased in daily clinical practice.

In the present study, we investigated the status and

issues regarding genetic medicine using publicly reimbursed CGP

tests in patients with metastatic prostate cancer who failed to

respond to standard therapies or for whom there were no appropriate

standard therapies. We also investigated the status of GC and

confirmatory germline testing for the secondary findings of cancer

susceptibility genes identified by tumor-only sequencing.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

This single-institution retrospective study

evaluated the records of patients with metastatic prostate cancer

who underwent CGP tests at Kitasato University Hospital (Kanagawa,

Japan) between August 2019 and November 2024. Patients with

metastatic prostate cancer who showed resistance to docetaxel or

second-generation androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs),

including abiraterone, apalutamide, enzalutamide, and darolutamide,

were subjected to CGP testing. Patients with androgen-indifferent

prostate cancer, such as neuroendocrine prostate cancer, also

underwent CGP testing. A total of 86 male patients were included,

with a median age of 73.5 years (range, 46-85). High-volume disease

was defined according to the CHAARTED criteria to evaluate the

metastatic status (5).

Pathological slides for patients who underwent

biopsy or radical prostatectomy at a facility other than our

institution were reviewed by our institutional pathologists.

Gleason scores were obtained from surgical specimens for patients

who underwent radical prostatectomy, or from biopsy specimens at

initial diagnosis for patients who did not undergo radical

prostatectomy. All patients had histologically confirmed prostate

cancer.

The Kitasato University Medical Ethics Organization

approved this study (B21-110). All methods were carried out in

accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed

consent was obtained in the form of an opt-out option on the

website and posters.

CGP tests and actionable genomic

alterations

F1CDx and F1LCDx were used for CGP tests in this

study. F1CDx is a tissue-based hybrid capture next-generation

sequencing (NGS) assay, and F1LCDx is a liquid biopsy-based NGS

assay. Both tests analyze 324 cancer-related genes and selected

intronic regions of 36 genes, designed to detect base

substitutions, insertions/deletions, copy number alterations, gene

rearrangements, microsatellite instability (MSI), and tumor

mutation burden (TMB). Sequencing covers the entire coding regions

of the included genes and selected intronic regions relevant for

fusion detection (1). CGP testing

was carried out using F1LCDx if the quality or quantity of an

archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sample was

inadequate for DNA analysis. CGP testing was only covered by

Japanese PHI once in a person's lifetime at the time of this study,

and individuals could thus not undergo both F1CDx and F1LCDx tests

under PHI.

The evidence level was categorized as A to F based

on the clinical practice guidelines for CGP tests in cancer

diagnosis and treatment (Edition 2.0) issued by the Joint Consensus

of Japanese Society of Medical Oncology, Japan Society of Clinical

Oncology, and Japanese Cancer Association. When GMT was identified

by CGP tests, actionable genomic alterations were defined as

alterations at or above evidence level D (1,6,7).

GC

If the patient wanted to know the results of the

possible germline gene alterations detected by the CGP test, the

physician in charge of genomic medicine disclosed if the patient

had secondary findings of cancer susceptibility genes identified by

tumor-only sequencing. The patients were advised to receive GC from

the physician in charge of genomic medicine. If a patient was

willing to receive GC, our hospital provided a system in which the

patient called the Genetics Division and made an appointment. After

receiving GC from clinical geneticists and certified genetic

counselors, the patient then decided if they wanted to undergo

confirmatory germline tests.

Statistical analyses

Three different grouping strategies were employed in

this study based on the analytical objectives. First, to evaluate

clinical characteristics and the utility of testing modalities,

patients were grouped according to the type of CGP test received:

F1CDx and F1LCDx. Second, for the analyses of progression-free

survival (PFS) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) 50% decline,

patients were stratified based on the type of post-CGP treatment:

GMT/PHI group and subsequent systemic therapy (SST) group. Third,

for the overall survival (OS) analysis, patients who received SST

or transitioned to best supportive care (BSC) were categorized as

the non-GMT group, and their outcomes were compared with those of

the GMT/PHI group. SST was defined as any prostate cancer treatment

administered after CGP testing that was not genomically matched

therapy. CRPC, PSA progression, and radiographic progression were

defined according to the Prostate Cancer Working Group 3.

Radiographic progression was evaluated according to Response

Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1) on computed

tomography scan or the 2 + 2 rule on bone scintigraphy (8,9).

Clinical progression was defined as cancer pain requiring

administration of opioids, the need to initiate subsequent therapy,

radiation therapy, surgical intervention for complications due to

tumor progression, or deterioration in Eastern Cooperative Oncology

Group (ECOG) performance to ≥ grade 3. A castrate testosterone

level was defined as ≤50 ng/dl.

PFS was defined as the time from initiation of GMT

or SST to first occurrence of any progression or death from any

cause, whichever occurred first. The events required to estimate

PFS were PSA progression, radiographic progression, clinical

progression, or any cause of death. Declines in serum PSA levels

≥50% were compared by χ2 test. OS was calculated from

the date of genetic testing to last follow-up. One patient was

confirmed as positive by BRACAnalysis® and started

olaparib before CGP testing, and was considered as receiving GMT in

PHI. PFS and OS were calculated from the start date of olaparib

administration and BRACAnalysis® testing, respectively,

and the best PSA response to olaparib was assessed in this

patient.

PFS and OS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method

and compared using the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Multivariate

Cox proportional hazards regression models were performed to

evaluate the factors influencing PFS. Differences were considered

statistically significant at P<0.05. All reported P-values are

two-sided. All analyses were performed using Stata version 15

(Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) and GraphPad Prism version

8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Patient profiles

Table I summarizes

the clinical characteristics of the 86 patients in the present

study. To assess the patient characteristics and the impact of each

testing modality on clinical utility, the patients were divided

into two groups based on the type of CGP test: F1CDx (n=63) and

F1LCDx (n=23). The median age of the overall population was 73.5

years, with 73 years for patients who underwent F1CDx and 74 years

for those who underwent F1LCDx. The median time to CRPC for the

overall population was 16 months, with 14.1 months for F1CDx and

24.4 months for F1LCDx. The detection of deleterious BRCA

alteration for the overall population was 16.2% (14/86), with 22.2%

(14/63) for F1CDx and 0% (0/23) for F1LCDx.

| Table IPatient characteristics. |

Table I

Patient characteristics.

| Variable | F1CDx (n=63) | F1LCDx (n=23) | Total (n=86) |

|---|

| Median age (range),

years | 73 (46-85) | 74 (57-84) | 73.5 (46-85) |

| Median PSA at

initial diagnosis (range), ng/ml | 95.5

(1.13-9,747) | 21.0

(6.86-8,537) | 55.0

(1.13-9,747) |

| Metachronous

(TxNxM0) | 21 (33.3) | 14 (60.9) | 35 (40.6) |

|

Radical

prostatectomy | 10 (15.9) | 5 (21.7) | 15 (17.4) |

|

Prostate

radiotherapy | 9 (14.3) | 8 (34.8) | 17 (19.8) |

| Synchronous

(TxNxM1) | 42 (66.7) | 9 (39.1) | 51 (59.4) |

|

High volume

(CHAARTED criteria) | 31 (49.2) | 8 (34.7) | 39 (45.3) |

| Gleason score | | | |

|

7 | 5 (7.9) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (8.1) |

|

8 | 16 (25.4) | 8 (34.8) | 24 (27.9) |

|

9 or 10 | 42 (66.7) | 12 (52.2) | 54 (62.8) |

|

Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.2) |

| Median time from

initiation of ADT to CGP tests (range), months | 32.8

(0.5-238.5) | 73.3

(24.7-151.4) | 40.6

(0.5-238.5) |

| Median time to CRPC

(range), months | 14.1

(1.9-98.6) | 24.4

(1.4-88.2) | 16.0

(1.4-98.6) |

| Deleterious

BRCA alteration | 14 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 14 (16.2) |

|

BRCA1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

|

BRCA2 | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| MSI-high and

TMB-high | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.5) |

| BRAF

V600 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.2) |

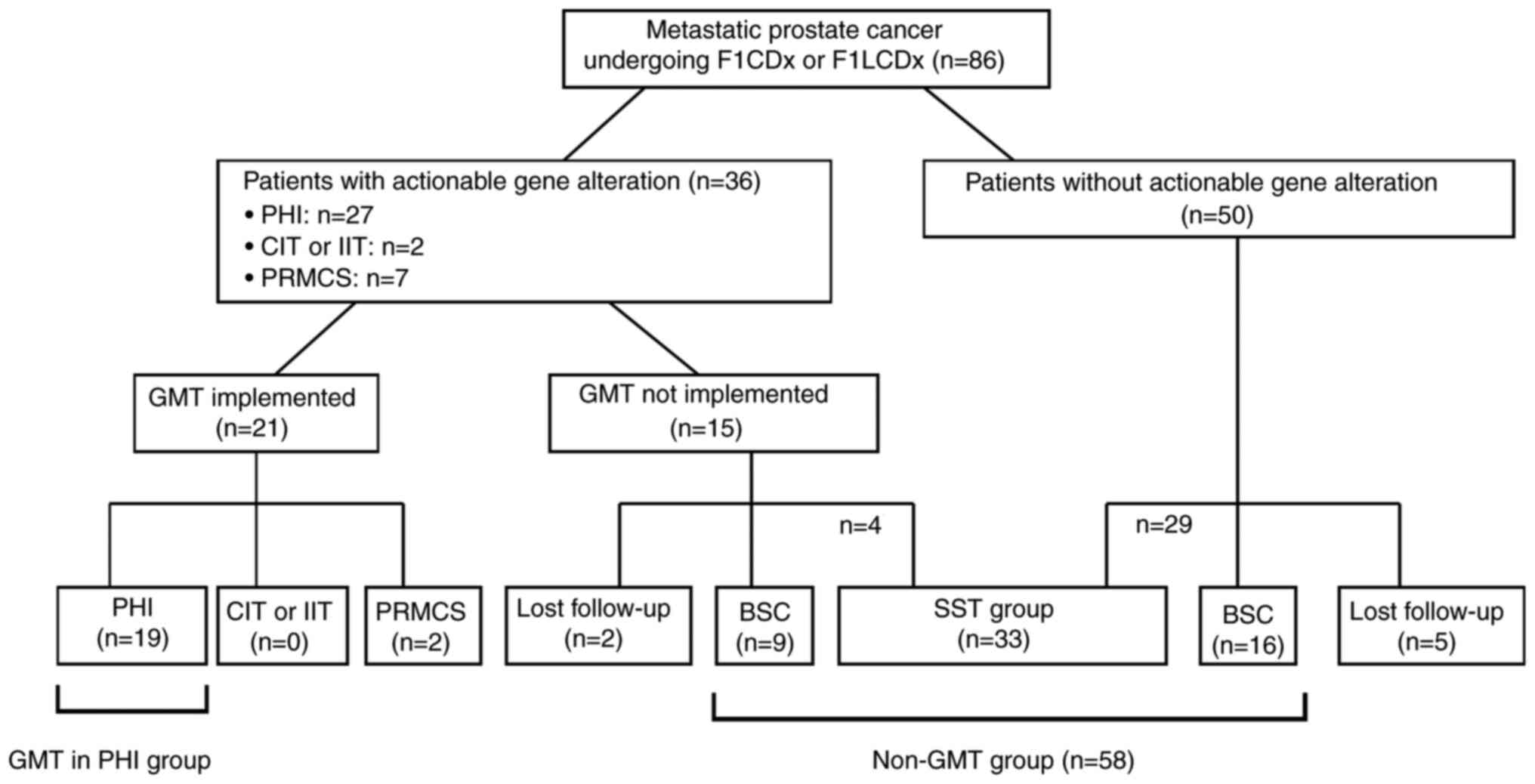

The patient profiles after CGP testing are shown in

Fig. 1. Based on expert panel

discussion, GMT was recommended in 36 patients (41.8%), including

27 in PHI, two in phase I or II clinical trials, and seven in

patient-requested medical care system phase II (PRMCS). GMT was

actually implemented in 21 patients (24.4%), including 19 (22.1%)

in PHI, none in clinical trials, and two (2.3%) in PRMCS. Of the 36

patients for whom GMT was recommended, 15 (17.4%) did not receive

the GMT due to deterioration of their general condition including

prostate cancer death (n=9), ineligibility for clinical trial

participation (n=1), the long distance to the clinical trial sites

(n=1), unwilling to undergo the GMT (n=2), transfer to other

institutions with loss to follow-up (n=2). Additionally, four

patients received SST other than the recommended GMT.

Among the 50 (58.2%) patients in whom no actionable

gene alteration was found, 29 received some kind of SST for

prostate cancer. Sixteen patients (18.6%) switched to BSC due to

the absence of aggressive prostate cancer treatment. Five patients

(5.8%) lost to follow-up due to transfer to other institutions.

A total of 33 patients (38.4%) received some form of

SST for prostate cancer other than GMT. Twenty-five patients

(29.1%) switched to BSC due to the absence of aggressive prostate

cancer treatment. Seven patients (8.1%) lost to follow-up.

Oncological outcomes

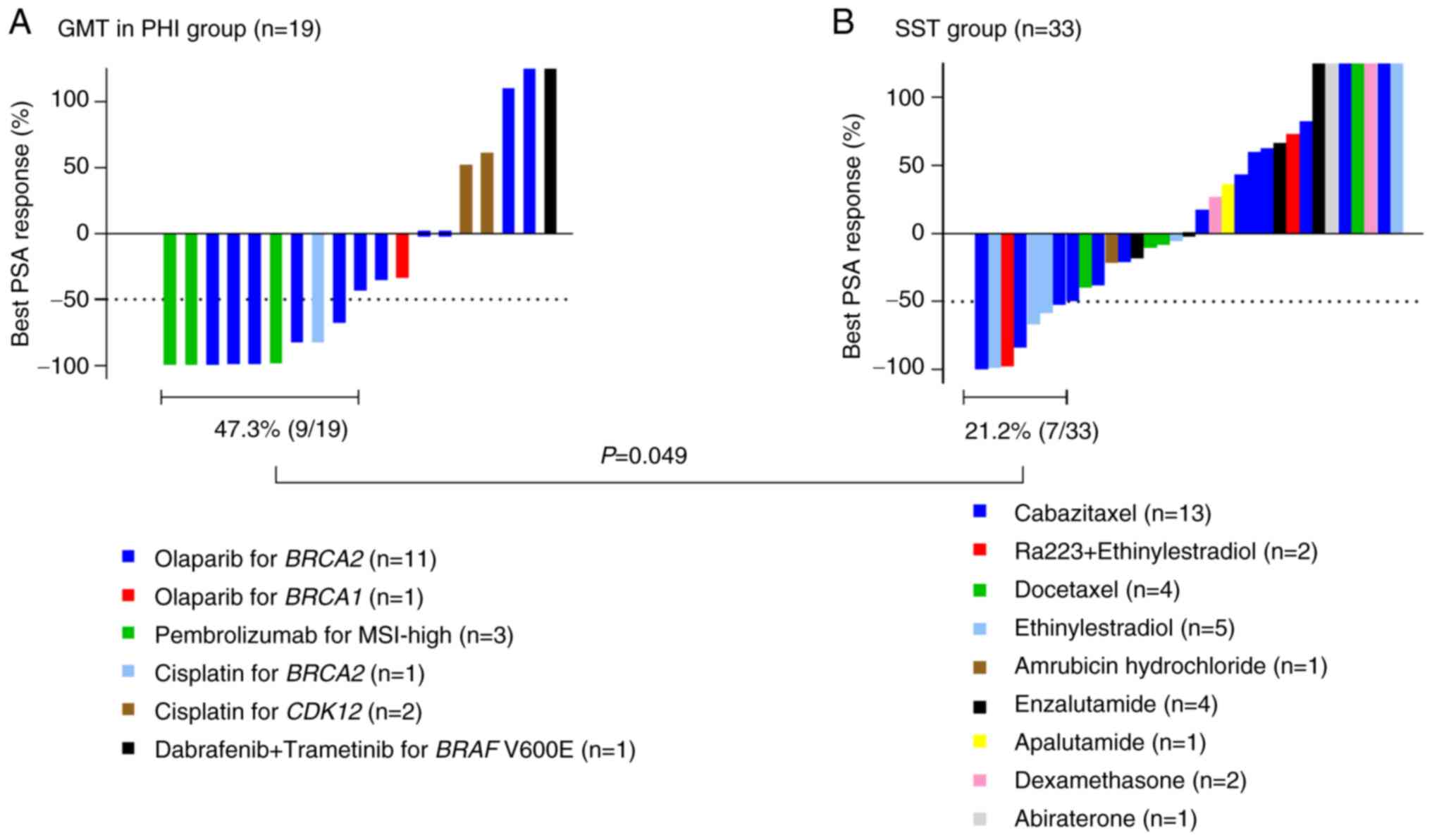

The PSA response in the GMT/PHI group and the SST

group based on the results of CGP testing is shown in Fig. 2. Because individual data for GMT in

PRMCS could not be disclosed, only data for GMT in PHI are

presented in Fig. 2A. The

treatments details for the 19 patients in the GMT/PHI group are

also shown in Fig. 2A, the

detailed oncological outcomes for the GMT/PHI group are shown in

Table SI, and details of the

treatments in the 33 patients in the SST group are shown in

Fig. 2B. Declines in serum PSA

levels ≥50% occurred more frequently in the GMT/PHI group (47.3%,

9/19) than in the SST group (21.2%, 7/33) (P=0.049). PFS in the

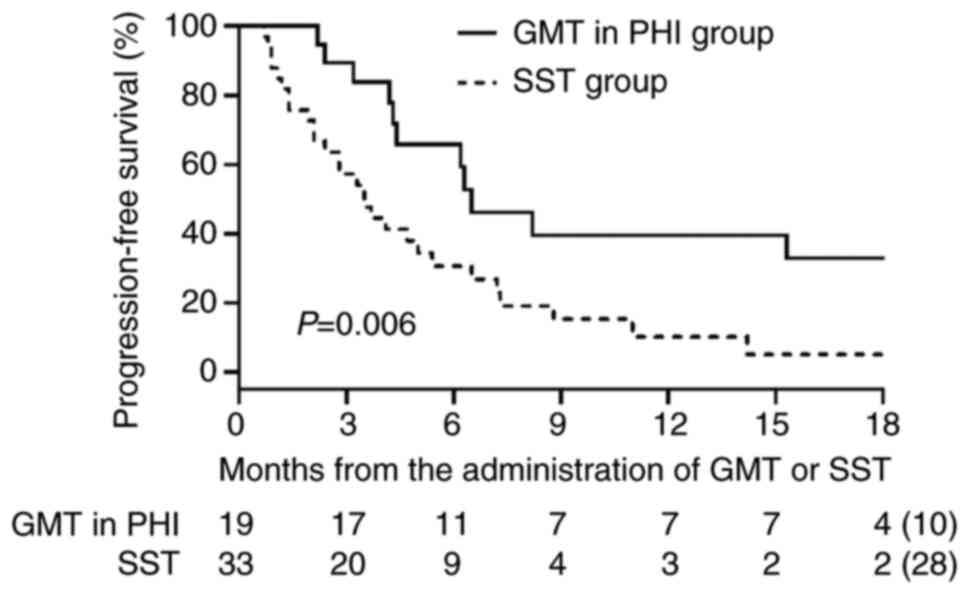

GMT/PHI and SST groups is shown in Fig. 3. PFS was significantly longer in

the GMT/PHI group than in the SST group (median: 6.5 vs. 3.5

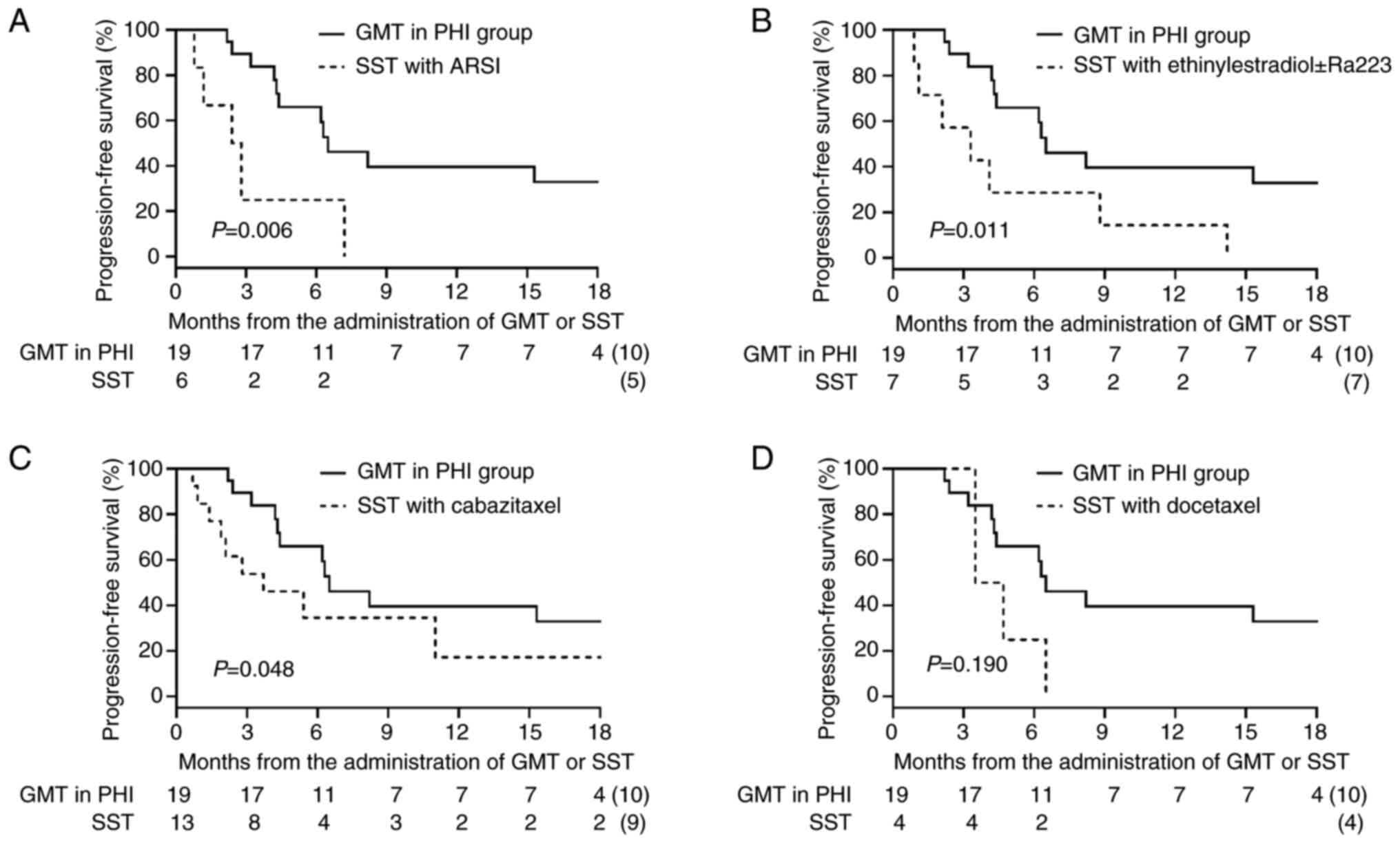

months; P=0.006). We conducted a subgroup analysis for PFS in which

each treatment regimen within the SST group was individually

compared with the GMT/PHI group (Fig.

4). The median PFS in the GMT/PHI group was significantly

longer than that in the SST subgroup treated with ARSI rechallenge

(6.5 vs. 2.6 months; P=0.006), ethinylestradiol ± Ra223 (6.5 vs.

3.3 months; P=0.011), and cabazitaxel (6.5 vs. 3.7 months;

P=0.048). In contrast, there was no statistically significant

difference in PFS between the GMT/PHI group and the SST subgroup

treated with docetaxel (6.5 vs. 4.1 months; P=0.190). After

multivariate adjustment, receiving GMT/PHI was the only factor that

showed a statistically significant association with longer PFS

(hazard ratio 0.44, 95% confidence interval 0.20-0.93) (Table II).

| Table IIMultivariate analyses using a Cox

proportional hazards model for progression-free survival. |

Table II

Multivariate analyses using a Cox

proportional hazards model for progression-free survival.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Baseline PSA at

initiation of GMT or SST, continuous | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.64 |

| CHAARTED criteria,

high volume vs. low volume | 0.97 | 0.50-1.89 | 0.94 |

| Time to CRPC,

continuous | 1.00 | 0.98-1.02 | 0.85 |

| GMT/PHI group vs.

SST group | 0.44 | 0.20-0.93 | 0.03 |

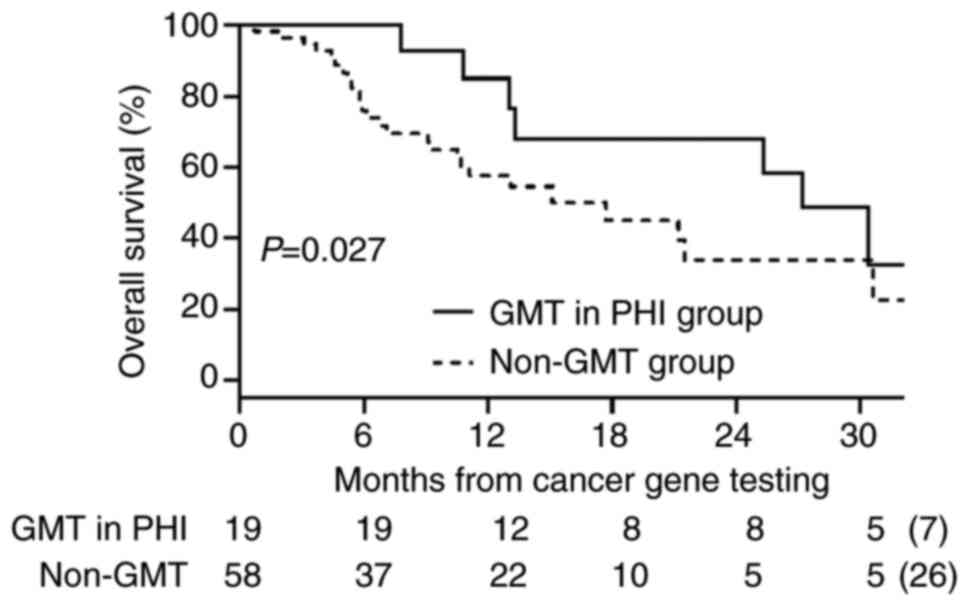

We defined the 25 patients who switched to BSC and

the 33 patients who received SST as the non-GMT group (n=58). OS

was significantly longer in the GMT/PHI group than in the non-GMT

group (median: 27.2 vs. 17.7 months; P=0.027) (Fig. 5).

Gene abnormalities known to be involved in cancer,

including alterations that may be targets of investigational

therapies, were summarized in Table

SII as potential actionable gene alterations identified by

F1CDx and F1LCDx (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29923460).

GC and confirmatory germline

testing

Table III shows

the implementation status of GC and confirmatory germline testing.

Of the 14 patients suspected of carrying deleterious germline

alterations, seven (50%) received GC, six of the seven patients

received confirmatory germline tests and two were diagnosed with

hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Two patients underwent

confirmatory genetic testing for Lynch syndrome, but the results

were negative. The main motivation for receiving GC was the

benefits for their family, but one patient visited the genetic

division simply because his doctor told him to receive GC; however,

this patient did not undergo confirmatory germline testing. Seven

patients (50%) did not visit the genetic division because of poor

health condition (n=1), death (n=1), not feeling the need (n=1),

family opposition to GC (n=1), no relation to prostate cancer

(n=1), and unknown reasons (n=2).

| Table IIIGenetic counseling and confirmatory

germline testing for cancer susceptibility genes. |

Table III

Genetic counseling and confirmatory

germline testing for cancer susceptibility genes.

| Alteration | Age, years | VAF, % | GC | Reasons for

receiving or not receiving GC | Germline

testing | Germline

alteration | Family history of

cancer |

|---|

| BRCA2

(A902fs*2) | Mid 40s | 64.4 | Received | Told by doctor to

receive GC | Untested | Unknown | Breast, mother;

stomach, father; uterus, grandmother |

| BRCA2

(V1447fs*1) | Early 70s | 83.6 | Received | For his family | Tested | Yes | None |

| BRCA2 (HD

exon 9-27) | Early 70s | - | Received | For his family | Tested | No | Prostate, father

and uncle; stomach, grandmother |

| BRCA2

(E2877*) | Early 50s | 76.9 | Received | For his family | Tested | Yes | Brain, aunt |

| BRCA2

M2393fs*19 | Early 80s | 36.6 | Received | For his family | Tested | No | Lung, father |

| MSI-high | Early 70s | - | Received | For his family | Tested | No | None |

| MSI-high | Mid 70s | - | Received | For his family | Tested | No | Tongue, sister |

| BRCA1 (HD,

exon 5-8) | Mid 50s | - | Not received | Poor health

condition | Untested | Unknown | None |

| BRCA2

E790fs*20 | Early 80s | 34.5 | Not received | Death | Untested | Unknown | None |

| BRCA2

(I729fs*21) | Late 70s | 25.7 | Not received | Not feeling the

need | Untested | Unknown | Uterus,

grandmother |

| BRCA2

(c.316+1G>T) | Mid 80s | 31.9 | Not received | Family

opposition | Untested | Unknown | Colon, father;

breast, aunt |

| WT1

c.1001+1G>T | Early 70s | 49.8 | Not received | No relation to

prostate cancer | Untested | Unknown | Biliary tract,

sister; stomach, sister; breast, sister; colon, cousin |

| ATM

c.5918+1G>T | Mid 70s | 71.4 | Not received | Unknown | Untested | Unknown | Pancreas, father;

stomach, uncle |

| PMS2

(E836fs*15) | Late 60s | 85.7 | Not received | Unknown | Untested | Unknown | None |

| MSH2

(Q170*) | | 66.3 | | | | | |

Discussion

The current study included patients with metastatic

prostate cancer who underwent F1CDx or F1LCDx testing after

progression to an ARSI or docetaxel, or patients for whom there was

no appropriate standard therapy due to androgen-indifferent

prostate cancer. Outcomes in terms of PFS and declines in serum PSA

levels ≥50% were significantly better in the GMT/PHI group compared

with the SST group. While approximately one in five of these

patients received GMT as a result of CGP testing, many patients who

underwent CGP tests were unable to receive GMT, highlighting the

need to address this issue in the future.

GMT was implemented in 21 patients (24.4%),

including 19 (22.1%) in PHI and two (2.3%) in PRMCS, but a total of

33 patients (38.4%) received some form of SST other than GMT,

because no actionable gene alterations were detected, or if gene

alterations were detected, the patients were unable to access GMT.

The timing of CGP testing is sometimes delayed in Japan since the

CGP testing is limited to patients with mCRPC who developed

resistance to docetaxel or ARSIs. As a result, patients experienced

disease progression at the time of disclosure of CGP results and

were no longer able to receive the recommended GMT. In addition,

accessibility to GMT through clinical trials is also one of the

issues that should be addressed. Some patients were unable to

receive treatment because of a lack of accurate information

regarding the eligibility criteria for clinical trials and the long

distance to the clinical trial sites. Sharing clinical trial

information among the hospitals and expanding clinical trial sites

across Japan are necessary (1).

CGP testing can detect gene alterations and genomic

signatures, including MSI, TMB, genome-wide loss of heterozygosity,

and homologous recombination deficiency. Although several

prospective randomized phase II trials have investigated the

efficacy of CGP testing for solid tumors, the clinical benefit of

GMT using CGP testing remains debatable (10-12).

The SHIVA trial was conducted for patients with any kind of

metastatic solid tumor refractory to standard of care. The use of

GMT outside their indications does not improve PFS compared with

treatment at physician's choice (10). The CUPISCO trial compared the

efficacy of GMT vs. standard platinum-based chemotherapy in

patients with an unfavorable cancer subset of unknown primary.

Subgroup analysis showed that patients with an actionable molecular

profile treated with GMT had longer PFS than those with an

actionable molecular profile treated with standard platinum-based

chemotherapy (hazard ratio 0.76, 95% confidence interval

0.42-0.99), with the greatest differences in patients treated with

atezolizumab for TMB-high or MSI-high, vemurafenib plus cobimetinib

for BRAF V600 or K601E alterations, or pemigatinib for

FGFR1, FGFR2, or FGFR3 alterations (12). These results support the

effectiveness of CGP testing for patients for whom there is no

appropriate standard treatment.

A previous study reported that BRCA

deleterious alterations were detected by tumor genetic testing in

approximately 10% of patients with mCRPC (2-4,13),

which was lower than the 16.2% in the current study. Mateo et

al (14) reported that

BRCA2 deleterious alterations were significantly more common

in patients who developed mCRPC in a short period, and patients

with BRCA2 deleterious alterations had the lower time to

androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) progression compared to those

without BRCA2 deleterious alterations. Thus, this difference

may be due to the relatively short time to CRPC observed in our

patients undergoing CGP tests. In the present study, olaparib was

administered to patients with mCRPC who were resistant to at least

one kind of ARSI, with a similar treatment population to the

PROfound study (2). Three of 12

patients receiving olaparib responded without progression for

>24 months, confirming the existence of deep and durable

responders among patients with BRCA deleterious alterations,

after resistance to ARSI. Several potential biological mechanisms

have been reported to underly long-term responses to poly ADP

ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. BRCA structural

variants, such as rearrangements and homozygous deletions, are

inherently resistant to reversion mutations and thus contribute to

durable responses to PARP inhibitors (15). Buonaiuto et al (16) reported that the efficacy of PARP

inhibitor is independent by BRCA domain defects or mutation

types. These findings are partly consistent with our results.

However, they are not sufficient to fully explain the mechanisms

underlying long-term responses to PARP inhibitors. The underlying

biological mechanisms need to be further explored.

The detection rate of MSI-high in prostate cancer is

approximately 3%, and a PSA response ≥50% with immune checkpoint

inhibitor (ICI) therapy has been reported to be 44-65% (17-19).

Three patients with both MSI-high and TMB-high genomic signatures

received pembrolizumab, all of whom showed a PSA response ≥50%,

while two achieved undetectable PSA levels in the present study.

Notably, in the two patients who achieved undetectable PSA levels,

the dominant lesions were confined to the lymph nodes and the

primary tumor. In contrast, one patient who died of prostate cancer

had extensive bone metastases. The efficacy of ICIs may differ

depending on the site of metastasis. In non-small cell lung cancer,

lymph node and primary lung lesions tend to show higher response

rates and better disease control with ICIs, whereas bone metastases

are consistently associated with poor responses and worse survival

outcomes (20,21). This likely reflects differences in

the tumor microenvironment (22).

In line with these findings, the differential response patterns

observed in our study may reflect the underlying immune contexture

of metastatic sites.

No patients in our study were identified as TMB-high

and microsatellite stable (MSS), in contrast to a previous study

that reported TMB-high with MSS in 0.7% of patients with prostate

cancer. Although the scientific rationale for ICIs is similar

between MSI-high and TMB-high with MSS, patients with prostate

cancer with TMB-high plus MSS did not demonstrate the same

durability to ICI treatment compared with MSI-high patients

(17).

BRAF gain-of-function alteration, RET

fusion, and NTRK fusion are rare alterations detected by CGP

testing in patients with prostate cancer. The use of molecular

targeted therapies, such as tumor-agnostic treatments, is approved

for these genetic alterations under PHI in Japan (23-26).

In the present study, we administered combination therapy with

dabrafenib and trametinib in a patient with a BRAF V600E

alteration. In this case, chest-to-pelvis computed tomography scans

revealed no primary tumors other than prostate cancer, while an

additional colonoscopy examination found no colorectal cancer and a

dermatological evaluation found no evidence of malignant melanoma.

In addition, F1LCDx identified the AR T878A alteration as a

covariate, with a variant allele frequency of 3.5%. We observed a

partial response in liver metastases on radiographic imaging. To

the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of the

efficacy of this combination therapy in a patient with BRAF

Class I alterations, which occur at the V600 codon and exhibit

extremely strong kinase activity by stimulating monomeric

activation of BRAF in prostate cancer (27). There have been no case reports of

successful treatment of prostate cancer with RET fusion and

NTRK fusion to date.

CGP tests increase the opportunities for GC by

identifying a proportion of patients with potential hereditary

cancers caused by cancer susceptibility genes (28). The introduction of the CGP test for

cancer treatment has changed physicians' awareness of hereditary

cancers; CGP tests can not only find eligible patients for GMT, but

can also reveal a predisposition to hereditary cancers. GC and

confirmatory germline testing play a crucial role in connecting the

early detection and early treatment of hereditary cancers in

relatives (29-32).

For metastatic prostate cancer, 11.8% of cases are reported to be

hereditary cancers associated with single DNA-repair gene mutations

(33); however, the current study

only identified two cases of hereditary cancers through GC. The

implementation status of GC after tumor-only sequencing at our

institution was insufficient to identify germline carriers of

cancer susceptibility genes (1,34).

When patients struggle with cancer treatment, it is sometimes

difficult for them to address secondary findings related to

hereditary cancers, because the GC is not related to their cancer

treatment. It may be difficult for patients to receive GC if they

need to return to the hospital to receive it, given that most

patients undergoing CGP tests are already spending a lot of time on

their cancer treatment. Considering the backgrounds of these

patients, our system in which patients were required to make their

own appointments for GC may have resulted in them missing

opportunities to receive GC. To improve the implementation of GC,

Kikuchi et al (1) reported

that a system in which GC was provided on the same day as the

disclosure of CGP results led to an increase in the number of

patients receiving GC. At our institution, there is a shortage of

certified genetic counselors and clinical geneticists who can

address the secondary findings generated by CGP testing. Increasing

the availability of these professionals would help ensure that GC

can be provided on the same day as the disclosure of CGP results.

In addition, there remains a lack of awareness among patients and

their families regarding hereditary cancers. This highlights the

need for broader educational efforts to improve understanding of

genetic risk.

Our study had several potential limitations,

including its retrospective nature. First, this was a

single-institution study, and the results thus lack adequate power

to make generalizations. Treatment strategies vary among

physicians, and these differences may have influenced our results.

Second, olaparib was not used in combination with an ARSI. The

results of the PROpel and TALAPRO-2 trials were recently approved

by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency in Japan

(3,4). Combined therapy with a PARP inhibitor

and an ARSI showed clinically meaningful improvement as a

first-line therapy in patients with mCRPC with BRCA

deleterious alterations who showed resistance to ADT alone or ADT

plus traditional hormonal therapy. The present study did not

reflect these new prospects for PARP inhibitors for mCRPC. Third, a

multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed to

adjust for baseline characteristics in the analysis for PFS.

However, we could not fully eliminate all potential confounders

such as age, ECOG performance status, treatment lines, and tumor

burden. These confounders are likely to influence the

interpretation of our results. Future studies with better control

of these variables are warranted to validate our findings. Fourth,

the small number of patients and short follow-up period may have

been insufficient to address the efficacy of genetic medicine and

further studies with longer follow-up and data from multiple

institutions involving more patients are needed. Although this

study included a small number of cases and the experience was

limited, GMT based on the results of CGP tests has had an impact on

our daily clinical practice.

In conclusion, CGP testing offers new hope for

patients with metastatic prostate cancer for whom there is

currently no appropriate subsequent therapy. However, most patients

do not receive GMT in our daily practice. The implementation of GC

for cancer susceptibility genes is thus insufficient and requires

improvement. Further developments in CGP testing are needed to

improve the clinical outcomes, including the development of novel

GMTs and the optimization of timings for CGP testing.

Supplementary Material

Oncological outcomes for GMT in PHI

group (n=19).

Summary of potential actionable gene

alterations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Susan Furness from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this

manuscript.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HT and DK designed the methodology. HT, AW, TY, and

JS analyzed the data. KIT, SS, SH, TS, KT, NA, RK and KM collected

the data. DK and HT wrote the original draft. FT and KM interpreted

the data and supervised. HT and DK confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Kitasato University Medical Ethics Organization

approved this study (approval no. B21-110). The present study was

in line with the Declaration of Helsinki (1995; as revised in

Edinburgh in 2000).

Patients consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained in the form of an

opt-out option.

Competing interests

Dr Tsumura received personal fees from AstraZeneca

during the study period and personal fees from Bayer, Janssen,

Astellas, and Nippon Shinyaku outside the submitted work. Dr Satoh

received personal fees from AstraZeneca during the study period and

personal fees from Janssen, Bayer, Astellas, and Nippon Shinyaku

outside the submitted work.

References

|

1

|

Kikuchi J, Ohhara Y, Takada K, Tanabe H,

Hatanaka K, Amano T, Hatanaka KC, Hatanaka Y, Mitamura T, Kato M,

et al: Clinical significance of comprehensive genomic profiling

tests covered by public insurance in patients with advanced solid

cancers in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 51:753–761.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F,

Shore N, Sandhu S, Chi KN, Sartor O, Agarwal N, Olmos D, et al:

Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N

Engl J Med. 382:2091–2102. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Saad F, Clarke NW, Oya M, Shore N,

Procopio G, Guedes JD, Arslan C, Mehra N, Parnis F, Brown E, et al:

Olaparib plus abiraterone versus placebo plus abiraterone in

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (PROpel): Final

prespecified overall survival results of a randomised,

double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 24:1094–1108.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Agarwal N, Azad AA, Carles J, Fay AP,

Matsubara N, Heinrich D, Szczylik C, Giorgi UD, Joung JY, Fong PCC,

et al: Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with first-line

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TALAPRO-2): A

randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 402:291–303.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, Liu G,

Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, Wong YN, Hahn N, Kohli M, Cooney MM, et

al: Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic Hormone-Sensitive prostate

cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:737–746. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Clinical practice guidance for

next-generation sequencing in cancer diagnosis and treatment

(edition 2.1). Available from: http://www.jca.gr.jp/researcher/topics/2020/files/20200518.pdf

Accessed June 27, 2023.

|

|

7

|

Koguchi D, Tsumura H, Tabata K, Shimura S,

Satoh T, Ikeda M, Watanabe A, Yoshida T, Sasaki J, Matsumoto K and

Iwamura M: Real-world data on the comprehensive genetic profiling

test for Japanese patients with metastatic Castration-resistant

prostate cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 53:569–576. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Clinical Practice Guidance for Prostate

Cancer. Available from: https://jua.members-web.com/topics1/uploads/attach/topic.

Accessed December 1, 2023.

|

|

9

|

Scher HI, Morris MJ, Stadler WM, Higano C,

Basch E, Fizazi K, Antonarakis ES, Beer TM, Carducci MA, Chi KN, et

al: Trial design and objectives for Castration-resistant prostate

cancer: Updated recommendations from the prostate cancer clinical

trials working group 3. J Clin Oncol. 34:1402–1418. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Le Tourneau C, Delord JP, Goncalves A,

Gavoille C, Dubot C, Isambert N, Campone M, Trédan O, Massiani MA,

Mauborgne C, et al: Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour

molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer

(SHIVA): A multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised,

controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16:1324–1334.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Belin L, Kamal M, Mauborgne C, Plancher C,

Mulot F, Delord JP, Gonçalves A, Gavoille C, Dubot C, Isambert N,

et al: Randomized phase II trial comparing molecularly targeted

therapy based on tumor molecular profiling versus conventional

therapy in patients with refractory cancer: Cross-over analysis

from the SHIVA trial. Ann Oncol. 28:590–596. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Krämer A, Bochtler T, Pauli C, Shiu KK,

Cook N, Janoski de Menezes J, Pazo-Cid RA, Losa F, Robbrecht DGJ,

Tomášek J, et al: Molecularly guided therapy versus chemotherapy

after disease control in unfavourable cancer of unknown primary

(CUPISCO): An open-label, randomised, phase 2 study. Lancet.

404:527–539. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sandhu S, Moore CM, Chiong E, Beltran H,

Bristow RG and Williams SG: Prostate cancer. Lancet. 398:1075–1090.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mateo J, Seed G, Bertan C, Rescigno P,

Dolling D, Figueiredo I, Miranda S, Nava Rodrigues D, Gurel B,

Clarke M, et al: Genomics of lethal prostate cancer at diagnosis

and castration resistance. J Clin Invest. 30:1743–1751.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Swisher EM, Kristeleit RS, Oza AM, Tinker

AV, Ray-Coquard I, Oaknin A, Coleman RL, Burris HA, Aghajanian C,

O'Malley DM, et al: Characterization of patients with long-term

responses to rucaparib treatment in recurrent ovarian cancer.

Gynecol Oncol. 163:490–497. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Buonaiuto R, Neola G, Caltavituro A,

Longobardi A, Mangiacotti FP, Cefaliello A, Lamia MR, Pepe F,

Ventriglia J, Malapelle U, et al: Efficacy of PARP inhibitors in

advanced high-grade serous ovarian cancer according to BRCA domain

mutations and mutation type. Front Oncol.

14(1412807)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lenis AT, Ravichandran V, Brown S, Alam

SM, Katims A, Truong H, Reisz PA, Vasselman S, Nweji B, Autio KA,

et al: Microsatellite instability, tumor mutational burden, and

response to immune checkpoint blockade in patients with prostate

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 30:3894–3903. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Abida W, Armenia J, Gopalan A, Brennan R,

Walsh M, Barron D, Danila D, Rathkopf D, Morris M, Slovin S, et al:

Prospective genomic profiling of prostate cancer across disease

states reveals germline and somatic alterations that may affect

clinical decision making. JCO Precis Oncol.

2017(PO.17.00029)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Barata P, Agarwal N, Nussenzveig R,

Gerendash B, Jaeger E, Hatton W, Ledet E, Lewis B, Layton J,

Babiker H, et al: Clinical activity of pembrolizumab in metastatic

prostate cancer with microsatellite instability high (MSI-H)

detected by circulating tumor DNA. J Immunother Cancer.

8(e001065)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Landi L, D'Inca F, Gelibter A, Chiari R,

Grossi F, Delmonte A, Passaro A, Signorelli D, Gelsomino F, Galetta

D, et al: Bone metastases and immunotherapy in patients with

advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer.

7(316)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yang K, Li J, Bai C, Sun Z and Zhao L:

Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in Non-small-cell lung

cancer patients with different metastatic sites: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 10(1098)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zhu YJ, Chang XS, Zhou R, Chen YD, Ma HC,

Xiao ZZ, Qu X, Liu YH, Liu LR, Li Y, et al: Bone metastasis

attenuates efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors and displays

‘cold’ immune characteristics in Non-small cell lung cancer. Lung

Cancer. 166:189–196. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hong DS, DuBois SG, Kummar S, Farago AF,

Albert CM, Rohrberg KS, van Tilburg CM, Nagasubramanian R, Berlin

JD, Federman N, et al: Larotrectinib in patients with TRK

fusion-positive solid tumours: A pooled analysis of three phase 1/2

clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 21:531–540. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, Siena S,

Shaw AT, Farago AF, Blakely CM, Seto T, Cho BC, Tosi D, et al:

Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK

fusion-positive solid tumours: Integrated analysis of three phase

1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 21:271–282. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shimoi T, Sunami K, Tahara M, Nishiwaki S,

Tanaka S, Baba E, Kanai M, Kinoshita I, Shirota H, Hayashi H, et

al: Dabrafenib and trametinib administration in patients with BRAF

V600E/R or non-V600 BRAF mutated advanced solid tumours (BELIEVE,

NCCH1901): A multicentre, open-label, and single-arm phase II

trial. EClinicalMedicine. 69(102447)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Subbiah V, Wolf J, Konda B, Kang H, Spira

A, Weiss J, Takeda M, Ohe Y, Khan S, Ohashi K, et al:

Tumour-agnostic efficacy and safety of selpercatinib in patients

with RET fusion-positive solid tumours other than lung or thyroid

tumours (LIBRETTO-001): A phase 1/2, open-label, basket trial.

Lancet Oncol. 23:1261–1273. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Owsley J, Stein MK, Porter J, In GK, Salem

M, O'Day S, Elliott A, Poorman K, Gibney G and VanderWalde A:

Prevalence of class I-III BRAF mutations among 114,662 cancer

patients in a large genomic database. Exp Biol Med (Maywood).

246:31–39. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ueki A, Yoshida R, Kosaka T and

Matsubayashi H: Clinical risk management of breast, ovarian,

pancreatic, and prostatic cancers for BRCA1/2 variant carriers in

Japan. J Hum Genet. 68:517–526. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Page EC, Bancroft EK, Brook MN, Assel M,

Al Battat MH, Thomas S, Taylor N, Chamberlain A, Pope J, Ni

Raghallaigh H, et al: Interim results from the IMPACT study:

Evidence for prostate-specific antigen screening in BRCA2 mutation

carriers. Eur Urol. 76:831–842. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Marchetti C, De Felice F, Palaia I,

Perniola G, Musella A, Musio D, Muzii L, Tombolini V and Panici PB:

Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: A meta-analysis on impact on

ovarian cancer risk and all cause mortality in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2

mutation carriers. BMC Womens Health. 14(150)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Usui Y, Taniyama Y, Endo M, Koyanagi YN,

Kasugai Y, Oze I, Ito H, Imoto I, Tanaka T, Tajika M, et al:

Helicobacter pylori, Homologous-recombination genes, and gastric

cancer. N Engl J Med. 388:1181–1190. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lubinski J, Kotsopoulos J, Moller P, Pal

T, Eisen A, Peck L, Karlan BY, Aeilts A, Eng C, Bordeleau L, et al:

MRI surveillance and breast cancer mortality in women with BRCA1

and BRCA2 sequence variations. JAMA Oncol. 10:493–499.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, De Sarkar

N, Abida W, Beltran H, Garofalo A, Gulati R, Carreira S, Eeles R,

et al: Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic

prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 375:443–453. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kawamura M, Shirota H, Niihori T, Komine

K, Takahashi M, Takahashi S, Miyauchi E, Niizuma H, Kikuchi A, Tada

H, et al: Management of patients with presumed germline pathogenic

variant from tumor-only genomic sequencing: A retrospective

analysis at a single facility. J Hum Genet. 68:399–408.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|