1. Introduction

Radiation esophagitis (RE) is a prevalent complication of radiotherapy for patients with thoracic tumors, leading to a variety of symptoms, such as dysphagia and pain, which significantly impact their quality of life (1). Additionally, RE can impede the efficacy of radiotherapy, reducing local control of the tumor and patient survival rates (1). The prevalence of RE has increased in recent years, driven by both the rising number of patients with thoracic tumors and advancements in radiotherapy techniques (2-4). Although these advanced techniques reduce severe RE (≥ Grade 3), they increase overall RE prevalence via dose escalation (≥40 Gy), combined regimens, such as immunotherapy-radiotherapy and unavoidable esophageal irradiation due to anatomical overlap between the esophagus and tumor targets (5). In thoracic tumor radiotherapy, the incidence of RE ranges 30-80%, with the highest incidence observed following radiotherapy for esophageal cancer (50-80%) (6,7). By contrast, the incidence after lung cancer radiotherapy is 20-50% (5,8). This phenomenon is associated with various factors, including the radiation dose (where the incidence increases significantly at ≥40 Gy), radiation field (where the risk increases when the length of the esophagus included in the radiation field is >5 cm) and the patient's underlying conditions (such as diabetes and gastroesophageal reflux disease) (8,9).

The employment of precise radiotherapy techniques has led to a decline in the incidence of severe RE (≥ grade 3), from 20 to 10% over the 2004-2013 study period; recent advances in proton beam therapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy have further reduced this rate to 6-8% (2015-2023) in contemporary practice (8,10). However, symptoms caused by RE remain a significant reason for the interruption of radiotherapy in clinical practice (3). The primary objective of research on RE is to achieve a balance between repair and fibrosis. As demonstrated by previous studies, the TGF-β1/p38 p38MAPK pathway has been identified as a pivotal regulatory node for this disease (11,12). Nevertheless, the precise roles of immune cells at varying stages of RE remain to be elucidated, a subject that forms the core of the present review (12,13). Although pharmacological treatments, nutritional support and endoscopic intervention are among the currently available therapeutic strategies, their effectiveness in alleviating symptoms and promoting tissue repair remains limited, where they are associated with adverse effects and complications (3). Consequently, there is a necessity to explore the pathophysiological mechanisms of RE in-depth to identify novel effective therapeutic targets and strategies.

Immune cells serve a dual role in tissue repair. They can promote an inflammatory response through cytokine and chemokine secretion to remove pathogens and necrotic cells from damaged tissues. By contrast, excessive inflammation may exacerbate tissue damage and impede repair (9,10). The TGF-β1/p38MAPK/fibronectin (FN) signaling axis exerts influence on tissue repair and fibrosis by modulating cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling (12-15). A comprehensive review of the literature, has been undertaken to explore the involvement of immune cells (macrophages, T cells and dendritic cells) and their interactions with the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis during RE ulcer repair in the present review. The aim of the present review is to identify novel targets and strategies for the treatment of RE.

2. Pathophysiological mechanisms of RE

The process of radiation-induced damage to the esophageal mucosa is characterized by its dynamism and progressive nature. Over time, the inflammatory response transitions from an acute phase to a proliferative phase, which may progress to a chronic fibrotic stage owing to a reparative imbalance (9). The pathological characteristics, clinical symptoms and molecular mechanisms vary significantly across these stages, which can be categorized into three phases. During the first phase, which is the acute phase, is characterized by the period of time during and following radiotherapy, extending for ~2 weeks after the conclusion of treatment. The principal manifestations include dysphagia pain (80% patients), dysphagia (60%) and a burning sensation in the region behind the sternum patients after alimentary intake. An endoscopic examination will typically reveal esophageal mucosal congestion and edema (grade 1) or patchy erosion (grade 2) (8,9). The second stage is known as the subacute stage, which typically occurs 2-4 weeks post-treatment. During this stage, the severity of symptoms escalates, marked by the emergence of persistent ulcers (Grade 3), with a subset of patients potentially encountering hematemesis as a consequence of mucosal vascular damage (with an incidence rate of 5-8%) (9). The third stage is the chronic stage, occurring >4 weeks after radiotherapy. This stage is characterized by esophageal fibrosis and stricture, presenting as progressive dysphagia (incidence rate, 10-15%), with severe cases requiring enteral nutrition support (8,9).

Molecular and cytological basis of radiation damage

Ionizing radiation has been demonstrated to induce direct DNA damage in esophageal epithelial cells, manifesting as double-strand breaks and base damage, thereby activating DNA damage repair mechanisms (16,17). Concurrently, radiation-induced damage has been shown to disrupt the normal progression of the cell cycle and activate cell cycle checkpoints (18,19). Furthermore, the damage induced by ionizing radiation has been shown to trigger changes in intercellular signaling. TGF-β1 is a pivotal factor in the initiation and termination of cell repair that serves a regulatory role in mucosal tissue repair in conjunction with FN. Activation of the p38MAPK signaling pathway promotes FN production, thereby facilitating rapid repair of the esophageal epithelial mucosa (20).

Epithelial damage and fibrotic processes

Epithelial cell damage in the esophagus is an early pathological change of RE, which can lead to the destruction of the epithelial barrier function. This frequently manifests as mucosal congestion, edema, epithelial cell degeneration and necrosis, which in turn triggers an aseptic inflammatory reaction (21). Miao et al (22) previously assessed the intervention effect of morin (3,5,7,2',4'-pentahydroxyflavone; a natural flavonol, predominantly isolated from plants, such as Morus alba and guava leaves;) on the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ/glutaminolysis/DEPTOR signaling pathway under inflammatory conditions. Using a bleomycin-induced mouse lung fibrosis model (in vivo) and a TGF-β1/hypoxia-stimulated NIH-3T3 fibroblast model (in vitro), it was demonstrated that morin reversed the following three key pathological alterations: i) Suppression of PPAR-γ (bleomycin/TGF-β1 reduced PPAR-γ protein and mRNA expression levels by ~65 and ~58%, respectively and decreased nuclear translocation from 72 to 29%); ii) hyperactivation of glutaminolysis (evidenced by a ~2.3X increase in the activity of the rate-limiting enzyme glutaminase-1); and iii) downregulation of DEPTOR with concomitant mTORC1 activation (DEPTOR protein decreased by ~62%, leading to a ~2.4-fold increase in mTOR phosphorylation). These conclusions were supported by detecting the expression of the myofibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (22). α-SMA expression was found to be upregulated specifically in lung fibroblasts (and their differentiated myofibroblasts) in bleomycin-induced mouse lungs (in vivo) and in TGF-β1/hypoxia-stimulated NIH-3T3 fibroblasts (a mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line, in vitro) under an inflammatory environment, whereas morin could inhibit the transformation of resident lung fibroblasts (which normally reside in the lung interstitium, the connective tissue between alveolar walls) to myofibroblasts (22). This suggests that factors, such as inflammation, may influence the relevant signaling pathways in lung fibrosis, which details organ-nonspecific cell cycle regulatory mechanisms [including ataxia telangiectasia and rad3-related (ATR)/checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1)/Wee1 pathways and cyclin-CDK complexes] that control fibroblast survival and activation (23). These mechanisms directly apply to esophageal biology. In RE, esophageal fibroblasts use similar inflammation-modulated cell cycle checkpoints (such as G2-phase activation through ATR/Chk1) and activity-dependent cell cycle progression to proliferate and contribute to esophageal fibrosis, mirroring the fibroblast regulation described in the lung models (23). These factors may activate the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation process by regulating relevant signaling pathways. This transformation is a conserved driver of organ fibrosis, including in the esophagus and aligns with established cell cycle regulatory mechanisms. In esophageal pathologies, such as RE (a precursor to fibrosis), local fibroblasts are stimulated by pro-fibrotic cues (including TGF-β1) to activate the ATR/Chk1/Wee1 signaling axis. This pathway induces G2 checkpoint arrest, which promotes fibroblast survival by facilitating DNA damage repair and subsequently enables their differentiation into myofibroblasts. This regulatory pattern, which mirrors cell cycle-dependent activation processes characterized in general fibrotic disease pathogenesis, directly associates the observed esophageal fibroblast behavior with the well-documented mechanisms of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation (23). Furthermore, as the inflammatory response to RE continues, the activation and transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts may be triggered, resulting in the secretion of substantial amounts of ECM (such as collagen and FN), leading to tissue fibrosis and scar formation (12). The resulting fibrosis imposes limitations on the dilatation function of the esophagus and can also give rise to fibrosis-related symptoms, including esophageal stricture, dysphagia and chronic ulceration, which can have a severely deleterious effect on patients' swallowing function (24). Furthermore, overactivation of the p38MAPK signaling pathway can aggravate the fibrosis (22). Table I systematically associates pathological stages of RE with immune signaling across three phases. During the acute inflammatory phase (1-2 weeks post-radiotherapy), esophageal epithelial necrosis and mucosal edema trigger aseptic inflammation, concomitant with M1 macrophage polarization (characterized by TNF-α and IL-1β secretion) and mild TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis activation, to initiate repair. In the proliferative repair phase (2-4 weeks), epithelial regeneration and granulation tissue formation occur alongside M2 macrophage polarization (marked by IL-10 and TGF-β1 secretion) and regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion. These processes are driven by sustained TGF-β1/p38MAPK activation, which promotes FN synthesis. By the fibrosis phase (>4 weeks), fibroblast transdifferentiation into myofibroblasts results in excessive ECM deposition. Concurrently, macrophages secrete TGF-β1 whilst dendritic cell function is suppressed. Both of the aforementioned phenomena are associated with hyperactivation of the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis, ultimately exacerbating tissue fibrosis (8,9,12,22,25,26).

|

Table I

Association between radiation esophagitis pathological staging and immune signaling.

|

Table I

Association between radiation esophagitis pathological staging and immune signaling.

| Pathological staging |

Time window |

Main pathological features |

Immune cell changes |

Status of TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis |

| Acute inflammatory phase |

Early stage after radiotherapy (1-2 weeks) |

Degeneration and necrosis of esophageal epithelial cells; mucosal congestion and edema, triggering aseptic inflammatory responses (12) |

Macrophages may be predominantly polarized to the M1 phenotype, potentially secreting proinflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and IL-1β; Th1 cells may be dominant among T cell subsets (11,26,32) |

Mild activation of TGF-β1; p38MAPK pathway initiated, promoting early-stage FN synthesis to accelerate mucosal repair (13,24) |

| Repair and proliferation phase |

Mid-stage after radiotherapy (2-4 weeks) |

Proliferation and migration of epithelial cells; formation of granulation tissue; gradual attenuation of inflammatory responses (12,22) |

Macrophages polarize toward the M2 phenotype, secreting anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β1; differentiation and expansion of regulatory T cells occur (a conventional mechanism based on immune homeostasis regulation, where this process is associated with the immune regulation mediated by TGF-β1 secreted by macrophages) (26,33) |

Sustained activation of TGF-β1; p38MAPK pathway mediates massive FN synthesis, promoting epithelial regeneration and matrix remodeling (24,34) |

| Fibrosis phase |

Late stage after radiotherapy (>4 weeks) |

Fibroblasts are activated and transdifferentiated into myofibroblasts, secreting large amounts of extracellular matrix components (such as collagen and FN), leading to tissue fibrosis and scar formation (9,22) |

Macrophages continuously secrete TGF-β1, participating in pathological processes by promoting fibrosis; the massive deposition of FN and collagen by dendritic cells is inhibited, due to the general inhibitory effect of TGF-β1 on dendritic cells, resulting in weakened immune activation (25) |

Excessive activation of TGF-β1; p38MAPK pathway remains hyperactivated; massive deposition of FN and collagen occurs, further exacerbating tissue fibrosis (10,13) |

To counteract excessive inflammation from M1 macrophage polarization in the acute inflammatory phase, administration of low-dose PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone has been reported to promote early transition to the M2 phenotype, accelerating inflammation resolution (27). In the repair and proliferation phase, modulating T-cell subset balance can enhance tissue repair. Low-dose IL-2 can expand the Tregs population by 15-20%, whilst carefully controlled TGF-β1 activity can avoid pro-fibrotic transformation (28,29). This control is achieved by RE-stage-specific strategies: i) p38MAPK inhibition (using the specific inhibitor SB203580) to reduce excessive FN synthesis; ii) timed administration of the TGF-β1 neutralizing antibody fresolimumab following the initial repair phase; and iii) low-dose TGF-β1 supplementation tailored to RE progression. In addition, targeting hyperactivated TGF-β1/p38MAPK signaling using the monoclonal antibody fresolimumab can block TGF-β1-receptor binding to inhibit fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation and reduce collagen deposition (30).

3. Molecular mechanisms of the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis

Multiple functions of TGF-β1

TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine with several biological functions, including the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, migration and immune response (31). Excessive ECM deposition is the main feature of fibrosis (12). In previous studies of experimental liver fibrosis, inhibition of FN deposition has been shown to reduce collagen accumulation and attenuate fibrosis (13,32). Similarly, in RE, TGF-β1 has been found to promote the synthesis and deposition of FN and collagen by activating the p38MAPK signaling pathway (12,26). This observation is supported by studies using the Sprague-Dawley rat RE model, which is established through targeted thoracic radiotherapy (40 Gy single dose) to mimic clinical radiation-induced esophageal injury. Notably, this may induce the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and in turn fibrosis of the tissue. In addition, TGF-β1 may inhibit the inflammatory response and promote tissue repair by regulating immune cell function. Specifically, it drives the M1-to-M2 phenotypic transition of macrophages. This process is mediated by activating the p38MAPK pathway, which induces secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β1. It also induces the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into regulatory T cells (Tregs). This differentiation relies on Smad/forkhead box (Fox)p3 signaling to suppress T helper 1 cell (Th1 cell)-mediated excessive inflammation. These regulatory effects of TGF-β1 are consistent with observations in Sprague-Dawley rat RE models and clinical studies (11,12,29).

p38MAPK signaling pathway

The p38MAPK signaling pathway has been found to be present in a wide range of eukaryotes (33) and has been identified as pivotal in various biological processes, including cellular stress response, inflammation regulation, cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (25,27,34). Zhang et al (12) previously demonstrated that the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling pathway may be implicated in esophageal mucosal repair. To confirm this, a Sprague-Dawley rat RE model was established by 40 Gy single-dose upper esophageal irradiation. H&E staining was used to track temporal changes in esophageal mucosal pathology, whereas reverse transcription-quantitative PCR/Western blotting were used to detect expression dynamics of key pathway molecules (TGF-β1, p38MAPK and FN). TGF-β1 and p38MAPK were observed to be upregulated early (week 1 post-irradiation) during acute mucosal damage, whilst FN expression recovered later (weeks 3-4) alongside epithelial regeneration. These findings suggest that the p38MAPK signaling pathway is closely associated with the development of RE and mucosal repair.

FN

FN is a macromolecular glycoprotein that is a constituent of the ECM and has been reported to be involved in various biological processes, including cell adhesion, migration and differentiation (29). Its role in ulcer healing has been extensively reported, with previous studies demonstrating its ability to promote mucosal repair, contribute to ECM remodeling and regulate cell signaling in the specific context of RE ulcer repair (28). Furthermore, FN can regulate cell physiology through interactions with the TGF-β1 and p38MAPK signaling pathways, thereby contributing to RE ulcer repair (26).

FN is a key downstream molecule of the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis. Its expression and function are regulated upstream by TGF-β1 activation and the p38MAPK pathway (12). Upon activation, TGF-β1 promotes FN synthesis through the p38MAPK pathway. In turn, FN exerts feedback regulation on the signaling axis primarily through ECM remodeling-mediated mechanotransduction and latent TGF-β1 sequestration (12). Separately, the sequential process of TGF-β1 activation (initiation), p38MAPK phosphorylation (transduction) and FN deposition (execution) constitutes the core pathway driving RE progression (12). The synergistic action of this signaling axis constitutes the core molecular basis for mucosal regeneration, inflammation resolution and fibrosis progression during RE ulcer repair (12). It also lays the groundwork for the subsequent exploration of how immune cells regulate RE repair, which is achieved through their interactions with TGF-β1, p38MAPK and FN (35).

FN functions as a pivotal downstream effector in the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis. Critically, FN establishes a self-reinforcing feedback loop through the following two mechanistically distinct yet interconnected pathways: i) Mechanotransduction-mediated amplification, where FN deposition increases ECM stiffness, activating integrin β1-dependent focal adhesion kinase/Src signaling (this cascade upregulates TGF-β receptor II expression and enhances cellular sensitivity to TGF-β1, thereby amplifying p38MAPK phosphorylation and driving further FN synthesis, forming a positive feedback circuit) (2,13,26); and ii) biochemical reservoir function, where the ED-A domain of FN binds latent TGF-β-binding protein-1, anchoring latent TGF-β1 within the ECM, which establishes a localized high-concentration reservoir to facilitate sustained TGF-β1 activation and perpetuate pathway signaling (3,13,36). Collectively, this dual feedback mechanism, operating through the ‘signal initiation (TGF-β1 release)/pathway transduction (p38MAPK phosphorylation)/effector execution (FN deposition)’ cascade, constitutes the molecular basis for the transition from physiological repair to pathological fibrosis in chronic RE (Fig. 1) (4).

|

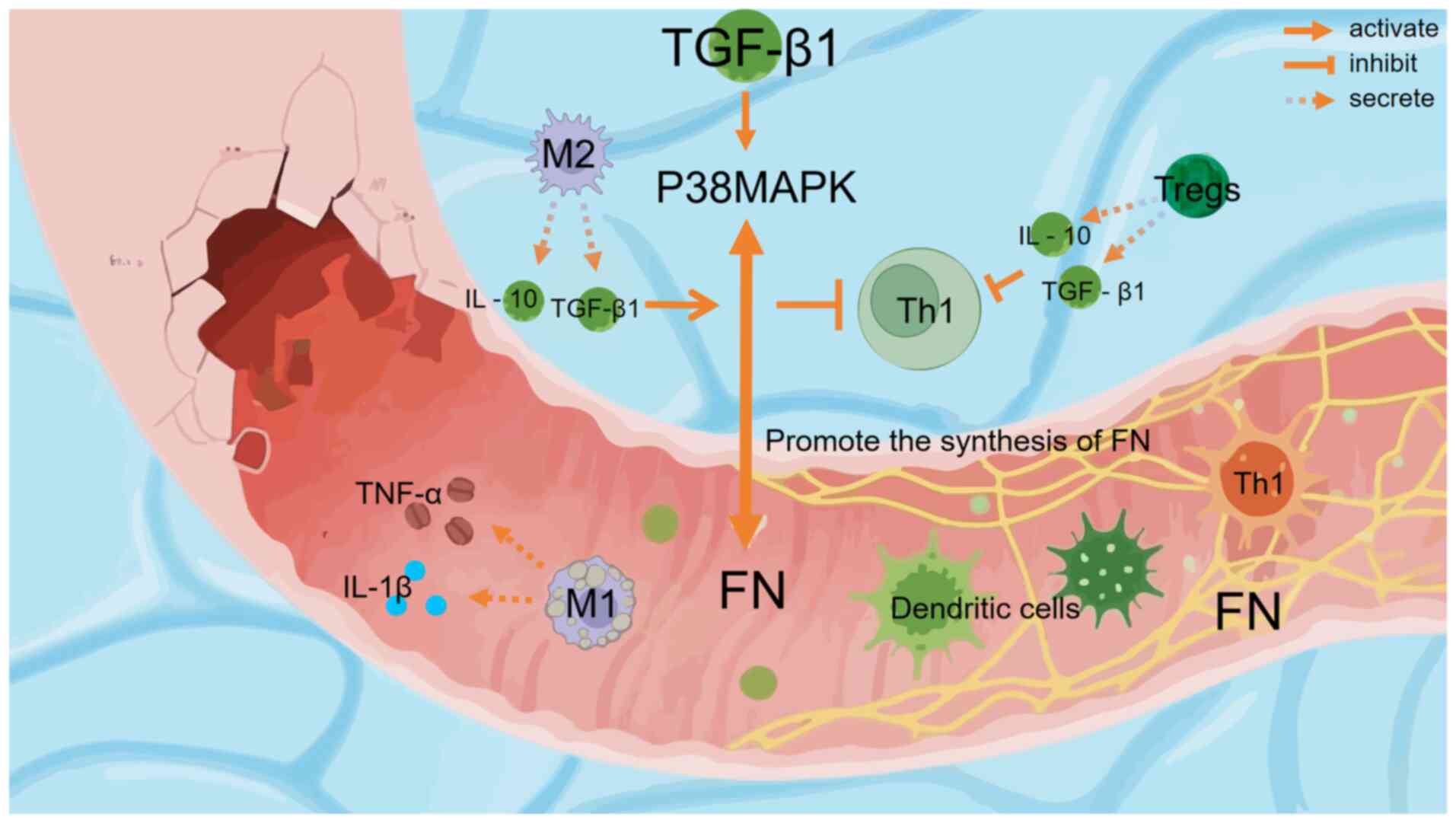

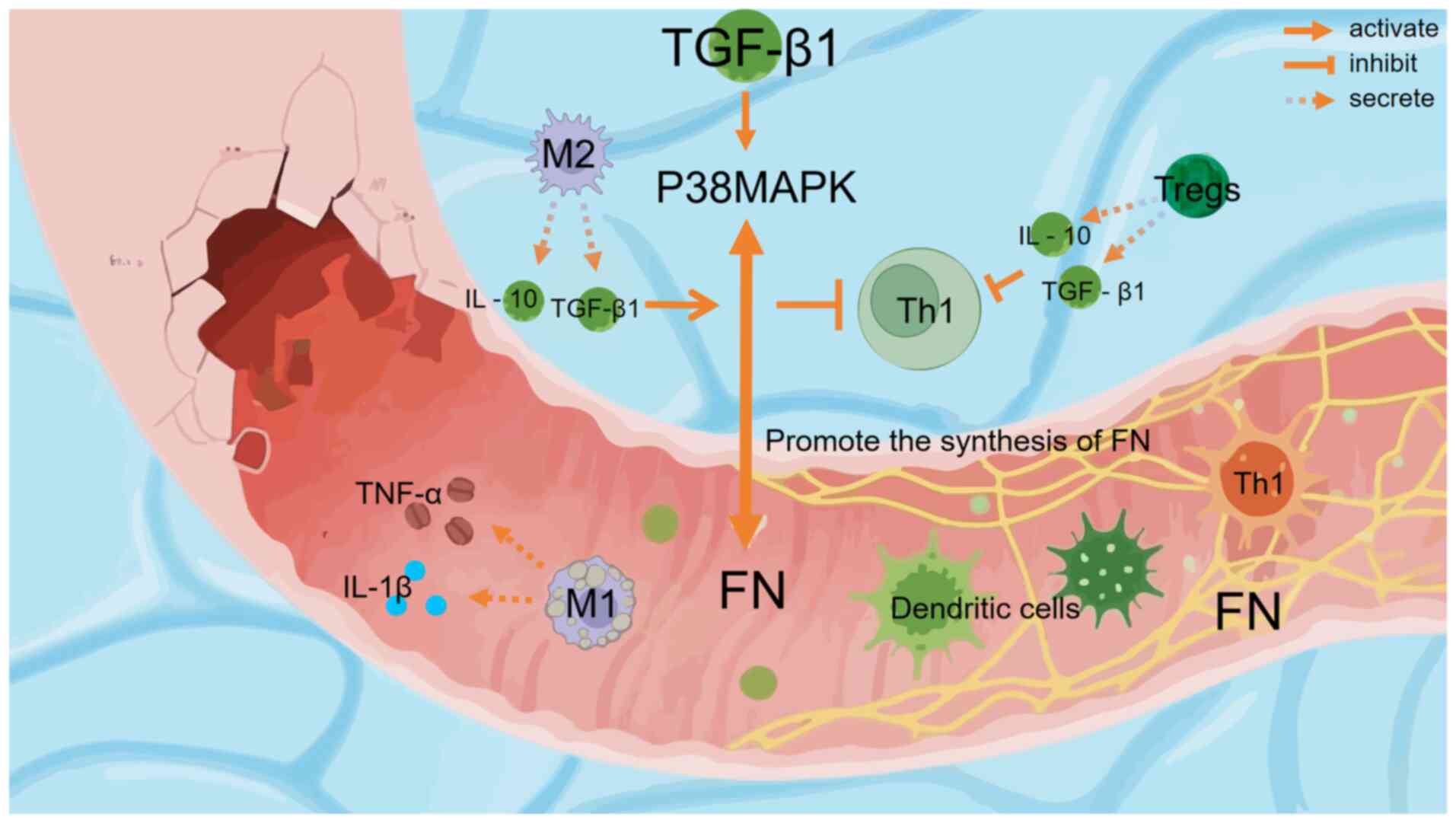

Figure 1

Visualization of immune regulation and tissue repair mechanisms of radiation esophagitis through the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis. Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism of immune cell involvement and the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis in radioactive esophagitis ulcer repair. M1 macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) at the ulcer sites. M2 macrophages, activated to secrete IL-10 and TGF-β1, can activate the p38MAPK pathway through TGF-β1. Notably, these M2-derived cytokines (IL-10 and TGF-β1) inhibit Th1 cells rather than activating them. Tregs also secrete IL-10 and TGF-β1 to inhibit Th1 cells. The TGF-β1/p38MAPK pathway promotes FN synthesis. Dendritic cells (with a spiky, green appearance) and other components (TNF-α, IL-1β and the damaged tissue area) in the esophageal tissue microenvironment participate in this repair-related immune regulation and tissue remodeling process. FN, fibronectin; Tregs, Regulatory T cells; Th1, T helper 1 cells.

|

4. Role of immune cells in RE repair and its association with the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis

Macrophages

Macrophages are pivotal in tissue repair, exhibiting both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions through polarization state transition (30). During the early phase of tissue injury and inflammation, macrophages secrete proinflammatory factors (such as TNF-α and IL-1β) through M1 polarization to promote inflammation. As the repair process advances, macrophages then convert to the M2 subtype, which predominantly secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-10 and TGF-β1) to inhibit inflammation and promote tissue repair (37). This process (macrophage M1-to-M2 polarization) has been widely observed in other inflammatory diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis, diabetic pulmonary injury and burn wound inflammation (22,26). In these conditions, macrophage phenotypic switching similarly mediates inflammation resolution and tissue repair, which is consistent with the aforementioned mechanisms. However, the specific mechanism in RE in this specific context require further investigation.

In RE, M2-type polarization of macrophages may be closely associated with the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis. TGF-β1 is a key factor in macrophage polarization and can regulate the inflammatory response of macrophages through the activation of the p38MAPK signaling pathway (13). In addition, TGF-β1 promotes macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype by upregulating the expression of key surface receptors, including CD206 (mannose receptor), CD163 (haptoglobin-hemoglobin scavenger receptor), TGF-β receptor II and IL-10 receptor. Concurrently, TGF-β1 activates critical signaling pathways, such as Smad2/3, PI3K/Akt and STAT6, which collectively drive the M2 polarization program (36). Upregulation of FN may synergize with TGF-β1 to promote the restoration of the esophageal mucosal tissue architecture (12,26). During the ulcer repair process in RE, TGF-β1 activates the p38MAPK pathway, promoting FN synthesis. As shown in Fig. 1, M2 macrophages (characterized by IL-10 and TGF-β1 secretion) are activated through this axis, whilst simultaneously inhibiting Th1 cells through IL-10 and TGF-β1, thereby creating an anti-inflammatory microenvironment conducive to tissue repair.

T Cells

The differentiation and functional regulation of T cell subpopulations in the immune response can result in important effects on tissue repair. Radiation damage activates CD4+ helper T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells through antigen-presenting cells, which participate in the immune response and repair processes (25). CD4+ T cells regulate the activity of other immune cells by secreting cytokines during immune responses, whereas CD8+T cells directly remove radiation-damaged cells through cytotoxic effects (38,39).

In RE, IFN-γ secreted by Th1 cells can promote inflammatory responses and cellular immunity, whereas IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 secreted by T helper 2 cells (Th2 cells) tend to suppress inflammatory responses and promote humoral immunity (1,40). It has been shown that TGF-β1 can induce T cells to differentiate into Tregs, thereby inhibiting Th1 cell activity and attenuating inflammatory responses (41,42). Furthermore, ovarian cancer cells can drive the differentiation of CD8+ T cells into Tregs with suppressive functionality, a process mediated through activation of the p38MAPK signaling pathway within CD8+ T cells (34,43). This mechanism is distinct from TGF-β-induced CD4+ Treg generation (34). This indicates that activation of the p38MAPK signaling pathway can affect T cell differentiation and function, which can influence the course of the immune response (44-46). The integration of immune regulation and tissue repair is a fundamental aspect of RE therapy, where by regulating the function and subpopulation balance of T cells, it can promote tissue repair and attenuate fibrosis (47).

Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells that are pivotal in initiating T-cell immune responses (48). In RE, dendritic cells capture and process antigens from damaged tissues and present them to T cells to activate an immune response (49,50). TGF-β1 has been shown to inhibit the maturation and activation of dendritic cells, reduce the expression of co-stimulatory molecules on their surface, such as CD80 (B7-1), CD86 (B7-2), CD40 and ICOS ligand, thereby inhibit T cell activation (51). Therefore, the TGF-β1 signaling axis can regulate dendritic cell function, affecting their antigen-presenting capacity and immune activation properties (45). Furthermore, TGF-β1 has been shown to activate specific T cell subpopulations, including regulatory Tregs and Th2 cells, through dendritic cells, with the p38MAPK signaling pathway potentially contributing to dendritic cell maturation, migration and antigen presentation (52). The interaction of dendritic cells with TGF-β1/p38MAPK may contribute to the repair of esophagitis and the establishment of immune tolerance by regulating immune homeostasis. Nevertheless, controversy persists regarding the specific role of dendritic cells in RE repair and their relationship with the signaling axis (35,53).

5. Integrative mechanisms of signaling axis and immune cell interaction regulation

The repair process in RE can be characterized by the regeneration of tissue cells and the fine regulation of the immune system (11). The TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis significantly influences the inflammatory response and tissue repair by regulating immune cell function. Macrophages participate in the repair process through polarization state transition. Specifically, TGF-β1 activates the p38MAPK signaling pathway, promoting the polarization of macrophages toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, which inhibits excessive inflammation and facilitates tissue repair (54-57). Balanced differentiation of T cell subsets can contribute to repair. TGF-β1 not only induces Treg differentiation to suppress inflammation, but can also regulate T cell function through the p38MAPK pathway. This regulation specifically involves inhibiting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IFN-γ) from Th1 cells, promoting the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-4, IL-10) by Th2 cells and modulating T cell proliferation and differentiation, which collectively maintain immune homeostasis and promote tissue repair (41). As key antigen-presenting cells, dendritic cells can initiate T cell immune responses. However, their maturation and activation are inhibited by TGF-β1, resulting in the reduced expression of surface co-stimulatory molecules and indirect suppression of T cell activation (55). Additionally, the p38MAPK signaling pathway may be involved in the maturation, migration and antigen presentation of dendritic cells (58-60). Together, these form a complex network of interactive regulation between the signaling axis and immune cells, supporting the dynamic balance of RE repair. Table II associates the RE clinical stages (RTOG criteria) with pathological features, clinical manifestations and immune/TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis dynamics. Grade 1 RE (acute inflammatory phase, 1-2 weeks) manifests as mild dysphagia with mucosal congestion, dominated by M1 macrophage-mediated inflammation through TNF-α/IL-1β secretion. Concurrent early activation of the TGF-β1/p38MAPK axis initiates FN synthesis (8,9,12,26). Grade 2 RE (proliferative repair phase, 2-4 weeks) presents with analgesia-requiring dysphagia and scattered ulcers. M2 macrophage polarization and Treg expansion occur alongside sustained TGF-β1/p38MAPK activation, driving substantial FN production (8,9,26,61). Grades 3-4 RE (fibrotic phase, 4-8/>8 weeks) exhibit confluent ulcers, luminal stenosis or perforation. Progressive FN deposition and axis hyperactivation, mechanistically linked to fibroblast transdifferentiation and ECM remodeling, are supported by experimental evidence (12,13,31,36).

|

Table II

Pathological features, immune regulation and signaling mechanisms across different clinical stages of radiation esophagitis.

|

Table II

Pathological features, immune regulation and signaling mechanisms across different clinical stages of radiation esophagitis.

| Clinical staging (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group criteria) |

Corresponding pathological staging |

Clinical features |

Relationship among immune cells, signaling axis and regulation |

| Grade 1 |

Acute inflammatory phase (1-2 weeks) |

Mild dysphagia-related pain; endoscopic findings of mucosal congestion (9,10) |

M1 macrophages dominate the inflammatory response, secreting proinflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and IL-1β; TGF-β1 initiates early activation and the p38MAPK pathway is activated to induce early synthesis of FN (12,26) |

| Grade 2 |

Repair and proliferation phase (2-4 weeks) |

Dysphagia pain requiring analgesia; endoscopic findings of scattered ulcers (8,9) |

M2 macrophages polarize, secreting anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-10 and TGF-β1, to promote repair; the proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) increases to suppress excessive immune responses; sustained activation of TGF-β1 promotes massive FN synthesis through the p38MAPK pathway (12,26,60) |

| Grade 3 |

Early fibrosis phase (4-8 weeks) |

Dysphagia requiring nutritional support; endoscopic findings of confluent ulcers (8,9) |

Macrophages continuously secrete TGF-β1; the p38MAPK pathway is overactivated (with increased phosphorylation levels), leading to enhanced FN deposition and driving the fibrosis process (12,13,31) |

| Grade 4 |

Fibrosis phase (>8 weeks) |

Esophageal stricture/perforation; endoscopic findings of luminal stenosis (8,9) |

The proportion of myofibroblasts increases; the TGF-β1/p38MAPK signaling axis is hyperactivated, promoting massive deposition of collagen and FN, ultimately leading to esophageal luminal stenosis (13,36) |

The prognosis of RE associates with disease severity. Patients with grade 1-2 RE typically achieve remission within 4 weeks post-radiotherapy without long-term sequelae. By contrast, 30% patients with grade 3-4 RE develop permanent esophageal strictures, accompanied by a 2X higher incidence of 5-year malnutrition and a 15% increased tumor recurrence risk compared with those in non-RE cohorts (8,9). Emerging cell-based therapies, including regulatory T-cell transplantation and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived immune cells, represent innovative treatment strategies. Future clinical trials must evaluate the safety, efficacy and feasibility of these approaches to establish evidence-based clinical management protocols for RE.

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

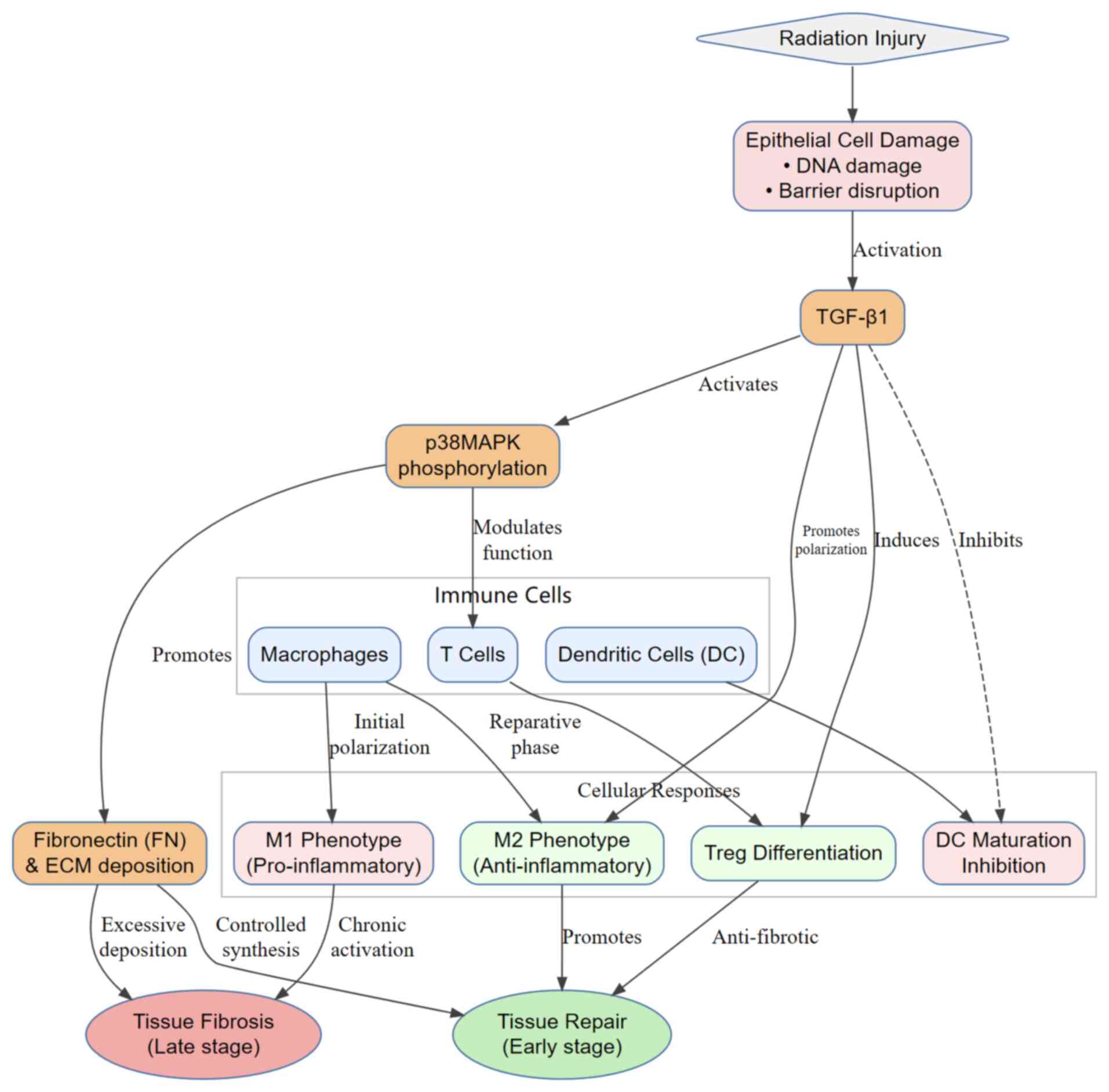

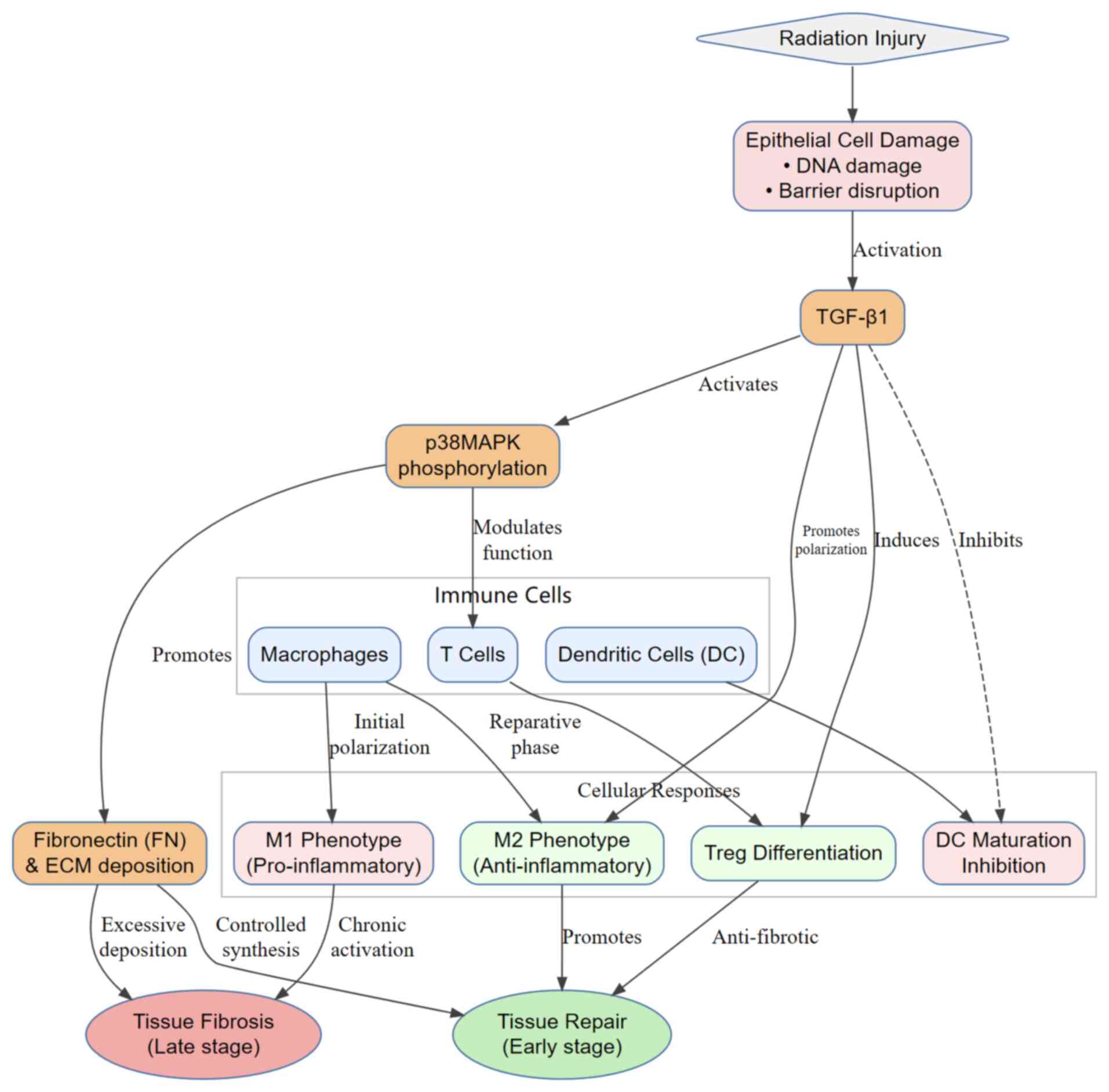

Radiation injury initiates epithelial cell damage, triggering TGF-β1 activation, which drives p38MAPK phosphorylation and modulates immune cell functions. Fig. 2 outlines the regulatory cascade, where TGF-β1 promotes M2 macrophage polarization and Treg differentiation during the early repair phase, whereas excessive FN deposition mediated by p38MAPK leads to tissue fibrosis during the late phase.

|

Figure 2

TGF-β1/p38MAPK signaling axis mediates immune cell regulation and tissue fibrosis progression after radiation injury. Radiation-induced esophageal epithelial damage (including DNA damage and barrier disruption) activates TGF-β1. TGF-β1 coordinately regulates immune cell responses through direct regulation (promoting M2 polarization of macrophages, inducing Treg differentiation and inhibiting dendritic cell maturation) and p38MAPK-mediated signaling modulation. Ultimately, the dynamic functions of immune cells (promoting repair in the early stage and fibrosis in the late stage) drive the pathological transition of radiation esophagitis from tissue repair to fibrotic progression. Treg, regulatory T cells.

|

In the present review, the regulatory role of the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis in RE ulcer repair and its interaction mechanisms with immune cells (macrophages, T cells and dendritic cells) were discussed. The TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis serves a multifaceted role in RE development. During the early phase of RE ulcer repair, this signaling axis is activated, with TGF-β1 contributing to esophageal epithelial mucosal repair by activating the p38MAPK pathway. This promotes FN and collagen synthesis and their deposition in the esophageal epithelium (12). However, persistent hyperactivation of this axis has been shown to promote the transformation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, which in turn can trigger excessive deposition of the ECM. This can then lead to tissue fibrosis, resulting in esophageal stenosis and dysphagia (9). These effects can seriously interfere with the normal life of the patients and decrease the efficacy of radiotherapy. Immune cells, such as macrophages, T cells and dendritic cells, are closely associated with this signaling axis in RE repair. Macrophages can perform different functions through polarization state transitions, with the early M1-type polarization initiating an inflammatory response to clear foreign bodies, whereas later polarization to the M2-type under regulation of the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis inhibits inflammation and promotes tissue repair (54,62,63). The differentiation of T-cell subpopulations and their functional regulation can also affect the immune response and tissue repair. TGF-β1 has been shown to induce regulatory T-cell differentiation, inhibit inflammation and regulate the function of specific T-cell subsets (Tregs and Th1 cells) through the p38MAPK/FN signaling pathway (43,64,65). This regulation includes enhancing Treg suppressive function, such as upregulating Foxp3 and secreting IL-10, whilst suppressing Th1 pro-inflammatory function, such as reducing IFN-γ and TNF-α production. Dendritic cells, as antigen-presenting cells, can activate the immune response, but TGF-β1 has been shown to inhibit their maturation and activation, thereby affecting the immune response and its interrelationship with the signaling axis. However, this remains a subject of ongoing debate, where it may be potentially significant for regulating immune homeostasis and promoting esophagitis repair. During the early repair stage of RE (1-2 weeks after radiotherapy), the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone can promote the polarization of macrophages to the M2 phenotype, accelerating the resolution of inflammation (66). During the fibrotic stage (>4 weeks), the TGF-β1 monoclonal antibody fresolimumab (1 mg/kg, Q2W) has been shown to reduce collagen deposition by 35% in a phase II trial of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which may be translatable to RE treatment (67).

As shown in Table III, specific experimental data from targeted drugs provide insights for RE treatment. Fresolimumab reduced collagen deposition by 35% in a phase II trial of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (12,30). Emerging iPSC-derived cell therapies represent innovative alternatives, necessitating rigorous trials to establish evidence-based protocols.

|

Table III

Clinically translational drugs targeting the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis.

|

Table III

Clinically translational drugs targeting the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis.

| Target |

Drug/therapy |

Mechanism |

Evidence in related diseases |

| TGF-β1 |

Fresolimumab (GC1008) |

Neutralizes all subtypes of TGF-β1, blocks its binding to receptors and inhibits both the TGF-β/Smad and non-canonical p38MAPK pathways (30) |

Systemic sclerosis: Phase II trial showed a reduction in dermal myofibroblast infiltration and a 35% decrease in collagen deposition; IPF: Reduced fibrosis markers (30) |

| TGF-β1/p38MAPK |

FTY-720 (Fingolimod) |

Inhibits TGF-β1 expression and p38MAPK phosphorylation, blocks the NF-κB pathway and reduces the deposition of collagen 1A1 and FN (72) |

For bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis: Masson staining shows reduced collagen and decreased IL-1β/TNF-α in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (72) |

| FN |

DP (12-deoxyphorbol 13-palmitate) |

Directly targets apolipoprotein L2, blocks its binding to SERCA2, inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress and the protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase hairy and Enhancer of Split-1 axis, whilst reducing the deposition of FN and other extracellular matrix induced by TGF-β1(73) |

For IPF (73) |

| p38MAPK |

SB203580 |

In SD rat RE model: SB203580 inhibits p38MAPK phosphorylation, reduces excessive FN synthesis and decreases the degree of esophageal mucosal fibrosis (12) |

In SD rat radiation esophagitis model, intervention verification showed SB203580 reduces excessive FN deposition and fibrosis in esophageal mucosa, by inhibiting p38MAPK phosphorylation, providing evidence for the efficacy of drugs targeting the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis in preventing and treating RE-related fibrosis at the disease model level (12) |

Given the pivotal role of the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis in RE fibrosis, mechanistic rationale supports targeting this pathway. SB203580 (p38MAPK-specific inhibitor) can theoretically suppress excessive FN synthesis during repair phase and reduces ECM deposition in fibrosis phase, consistent with observed attenuation of esophageal mucosal fibrosis in Sprague-Dawley rat RE models (12).

Given the complexity, spatiotemporal dynamics and cellular heterogeneity of the pathological process of RE, current understanding of the mechanisms by which the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling axis precisely regulates immune cells at different repair stages remains limited. The differences in the regulation of immune cell polarization states and functions by this signaling axis during the different repair periods, in addition to the interactions among immune cells and other cell types, require further investigation. In the future, multi-omics and single-cell sequencing technologies should be utilized to comprehensively analyze changes in genes, proteins and metabolites during the occurrence and development of RE to accurately decipher the functional differences and dynamic evolution of immune cell subsets, whilst providing theoretical support for achieving precise immune regulation in patients with RE. In terms of clinical translation, based on a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of RE and the functions of immune cells, specific modulators targeting this signaling axis can be developed to reduce inflammatory responses, inhibit fibrosis and promote tissue repair by regulating the activity of the signaling pathways. In addition, immunomodulatory therapies also show broad application prospects. By regulating macrophage polarization, T cell subset balance and dendritic cell functions, the immune repair effect can be further enhanced and the clinical symptoms of RE can be alleviated. Single-cell sequencing application may reveal that the CD206+CD163+macrophage subset, a specialized M2-polarized macrophage population co-expressing canonical markers CD206 and CD163 and a key source of TGF-β1 in the fibrotic phase, specifically express high levels of TGF-β1 during the fibrotic phase (12,68). Based on this, antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) targeting CD206 on the surface of this subset may be designed. These ADCs can block the pro-fibrotic function of this subset by precisely delivering anti-fibrotic drugs (such as p38MAPK inhibitors), whilst avoiding interfering with the repair function of macrophages at other stages (63,68). This strategy can specifically inhibit the fibrotic process without interfering with early inflammation elimination and tissue regeneration.

Previous clinical studies have shown that modified Danzhen Oil can reduce the levels of inflammatory factors, such as TGF-β1, in patients with acute RE, thereby alleviating inflammatory responses (69-71). In the future, network pharmacology will need to be used to analyze the potential active components, actionable targets and mechanisms of modified Danzhen Oil. Subsequently, in cell experiments (with groups including the normal group, radiation group, modified Danzhen Oil group and radiation + modified Danzhen Oil group, where p38MAPK expression is regulated in each group), cell viability and migration ability will need to be detected, where the expression of molecules, such as p38MAPK (including phosphorylated sites), FN and TGF-β1, will be analyzed. Additionally, the interaction between p38MAPK and FN, in addition to between p38MAPK and TGF-β1, will be verified to determine whether modified Danzhen Oil can reduce FN expression by inhibiting p38MAPK phosphorylation, clarifying its multi-target regulatory mechanism and providing a basis for clinical application. (Figs. 1 and 2).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present review was supported by the Shaanxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology General Project ‘Basic and Clinical Translational Research on Promoting Radioactive Esophagitis Ulcer Repair Based on TGF-β1/P38MAPK/FN Signaling Axis by Modified Egg Zhen Oil’ (grant nos. 2024SF-YBXM-459 and 2024.01-2025.12) and Basic Research Programme in Natural Sciences-General Projects-General Projects-Exploring the Theory of ‘Treating Atrophy by Targeting the Yangming Meridian’ Under the ‘Spleen-Intestine-Muscle’ Model: A Study on the New Mechanism of Liu Junzi Decoction in Improving Cachexia-Associated Sarcopenia in Gastric Cancer Through Regulating the Intestinal Microbiome (grant no. SZY-KJCYC-2025-LC-003).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

KW was involved in conceptualization (review framework on TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN-immune crosstalk), methodology (systematic literature retrieval/analysis), investigation (mechanisms of macrophage polarization, T-cell differentiation and dendritic cell function) and writing-original draft (full manuscript including pathophysiology, signaling, immune roles). JZhang was involved in validation [molecular mechanisms: Systematic organization and cross-check of preclinical evidence for the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN axis and CD206+CD163+ macrophage phenotype across cited cell and animal studies, alignment of mechanistic claims with clinical observations such as the association between CD206/TGF-β1 levels and fibrotic-phase tissues, and contextualization of discrepancies in cited studies (such as p38MAPK effects on Treg differentiation) by re-examining reference methodologies], formal analysis (clinical translation), Resources (integration of animal/clinical evidence), Writing-review & editing (pathological correlations in Tables I-II). XZ was involved in data curation (T-cell/dendritic cell literature), visualization (mechanistic schematics in Figs. 1 and 2), Writing-review and editing (clarification of signaling mechanisms). JZheng was involved in research direction and structural design, writing-review and editing (future perspectives on multi-omics/single-cell sequencing). All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Wen YP, Lou YN, Luo JY and Jia LQ: Research progress of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of radiation esophagitis. Zhongguo Jizhen Yixue. 30:1487–1490. 2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

2

|

Wu Q, Li Q, Zhang R, Cui Y, Zou J, Zhang J, Ma C, Han D and Peng Y: Research progress of radiation esophagitis: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 104(e42273)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wang K, Zhao J, Duan J, Feng C, Li Y, Li L and Yuan S: Radiomic and dosimetric parameter-based nomogram predicts radiation esophagitis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing combined immunotherapy and radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 14(1490348)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ha JJ, Hong SE, Lee JY, Ha IH and Lee YJ: Prevention and treatment of radiation-induced esophagitis with oral herbal medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 24(15347354251349168)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Yazbeck VY, Villaruz L, Haley M and Socinski MA: Management of normal tissue toxicity associated with chemoradiation (primary skin, esophagus, and lung). Cancer J. 19:231–237. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Li JC, Liu D, Chen MQ, Wang JZ, Chen JQ, Qian FY, Chen C, Zhang HP and Pan JJ: Different radiation treatment in esophageal carcinoma: A clinical comparative study. J Buon. 17:512–516. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang X, Han W, Zhang W, Wang X, Ge X, Lin Y, Zhou H, Hu M, Wang W, Liu K, et al: Effectiveness of S-1-based chemoradiotherapy in patients 70 years and older with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 6(e2312625)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Soni PD, Boonstra PS, Schipper MJ, Bazzi L, Dess RT, Matuszak MM, Kong FM, Hayman JA, Ten Haken RK, Lawrence TS, et al: Lower incidence of esophagitis in the elderly undergoing definitive radiation therapy for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 12:539–546. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang B, Qu MJ and Liu SX: Research progress of radiation esophagitis. Chin J Radiat Oncol. 23:552–554. 2014.(In Chinese).

|

|

10

|

Yang C, Wang J and Yuan S: Chinese clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of radiation-induced esophagitis. Precis Radiat Oncol. 7:225–236. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhang FP, Zhao XY, Wang XW, Gao JS, Liu LK and Bai JY: Exploring the pathogenesis of radiation esophagitis from the perspective of mucosal repair. Oncol Prog. 16:1578–1581. 2018.(In Chinese).

|

|

12

|

Zhang FP, Zhao XY, Hao SL, Fan GL, Li XL, Wang AR and Liu L: Study on the pathogenesis of radiation esophagitis based on the TGF-β1/p38MAPK/FN signaling pathway. Cancer Res Prev Treat. 47:823–827. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

13

|

Altrock E, Sens C, Wuerfel C, Vasel M, Kawelke N, Dooley S, Sottile J and Nakchbandi IA: Inhibition of fibronectin deposition improves experimental liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 62:625–633. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Austin PJ, Karrasch JF and O'Brien JA: A dual role of microbiota type 17 immunity in tissue repair and pain. Immunol Cell Biol. 101:281–284. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Raghavan JV and Jhunjhunwala S: Role of innate immune cells in chronic diabetic wounds. J Indian Inst Sci. 103:249–271. 2023.

|

|

16

|

Luo DX, Huang Y and Liu CJ: Mechanism study of Yougui Decoction combined with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells transfected by tgf-β1 in repairing rat cartilage tissue. Sichuan Zhong Yi Xue. 40:49–53. 2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

17

|

Liu J, Liu Y, Peng L, Li J, Wu K, Xia L, Wu J, Wang S, Wang X, Liu Q, et al: TWEAK/Fn14 signals mediate burn wound repair. J Invest Dermatol. 139:224–234. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wei Q, Liu D, Chu G, Yu Q, Liu Z, Li J, Meng Q, Wang W, Han F and Li B: TGF-β1-supplemented decellularized annulus fibrosus matrix hydrogels promote annulus fibrosus repair. Bioact Mater. 19:581–593. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liu B, Zhao ZY, Li JM, Zhou Y and Zhang JX: Effects of edaravone on apoptosis of cells around hematoma and expression of P38MAPK protein in rats with intracerebral hemorrhage. Chin Pharm. 21:1173–1175. 2010.(In Chinese).

|

|

20

|

Carswell L, Sridharan DM, Chien LC, Hirose W, Giroux V, Nakagawa H and Pluth JM: Modeling radiation-induced epithelial cell injury in murine three-dimensional esophageal organoid. Biomolecules. 14(519)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Jia C, Wang Q, Yao X and Yang J: The role of DNA damage induced by low/high dose ionizing radiation in cell carcinogenesis. Explor Res Hypothesis Med. 6:177–184. 2021.

|

|

22

|

Miao Y, Geng Y, Yang L, Zheng Y, Dai Y and Wei Z: Morin inhibits the transformation of fibroblasts towards myofibroblasts through regulating ‘PPAR-γ-glutaminolysis-DEPTOR’ pathway in pulmonary fibrosis. J Nutr Biochem. 101(108923)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Syljuåsen RG: Cell Cycle Effects in Radiation Oncology. In: Radiation Oncology. Wenz F (ed). Springer, Cham, 2019.

|

|

24

|

Chang SH, Qin GY, Li ZW, Wang YP, Chen LH, Tan CF and Li ZY: Research progress of low-dose hyper-radiosensitivity and induced radioresistance. J Nucl Agric Sci. 2:196–199+187. 2008.(In Chinese).

|

|

25

|

Preet Kaur A, Alice A, Crittenden MR and Gough MJ: The role of dendritic cells in radiation-induced immune responses. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 378:61–104. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

He WF and Yan LF: The Regulatory role and related mechanisms of macrophages in wound healing. Zhonghua Shao Shang Yu Chuang Mian Xiu Fu Za Zhi. 39:106–113. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Lan T, Chen J, Zhang J, Huo F, Han X, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Huang Y, Liao L, Xie L, et al: Xenoextracellular matrix-rosiglitazone complex-mediated immune evasion promotes xenogenic bioengineered root regeneration by altering M1/M2 macrophage polarization. Biomaterials. 276(121066)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Raffin C, Vo LT and Bluestone JA: Treg cell-based therapies: Challenges and perspectives. Nat Rev Immunol. 20:158–172. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

von Spee-Mayer C, Siegert E, Abdirama D, Rose A, Klaus A, Alexander T, Enghard P, Sawitzki B, Hiepe F, Radbruch A, et al: Low-dose interleukin-2 selectively corrects regulatory T cell defects in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 75:1407–1415. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Siani A: Pharmacological treatment of fibrosis: A systematic review of clinical trials. SN Compr Clin Med. 2:531–550. 2020.

|

|

31

|

Zhou L: The mechanism of the PKC-TGF-β1-p38MAPK signaling pathway and FN expression in pulmonary injury of diabetic rats (unpublished thesis). Hebei Medical University, 2010 (In Chinese).

|

|

32

|

Wu XD, Zhang QQ, Li LN and Liu JS: Research progress on traditional Chinese medicine combined with radiotherapy in the treatment of esophageal cancer and its mechanism. Chin J Clin Oncol. 45:859–862. 2018.(In Chinese).

|

|

33

|

Ma J, Gong Q, Pan X, Guo P, He L and You Y: Depletion of Fractalkine ameliorates renal injury and Treg cell apoptosis via the p38MAPK pathway in lupus-prone mice. Exp Cell Res. 405(112704)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Guo JR and Chen YZ: Progress in research on fibronectin in tumors and anti-infection. J Fujian Med Univ. 6:670–672. 2006.(In Chinese).

|

|

35

|

Kitamura H, Tanigawa T, Kuzumoto T, Nadatani Y, Otani K, Fukunaga S, Hosomi S, Tanaka F, Kamata N, Nagami Y, et al: Interferon-α exerts proinflammatory properties in experimental radiation-induced esophagitis: possible involvement of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Life Sci. 289(120215)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tian XH, Wang Q, Shang LZ, Han YZ, Pan XL and Guo YH: Effect of Chaihu Shugan Powder on TGF-β1/p38MAPK signaling pathway in rats with liver fibrosis and its correlation study. J Basic Chin Med. 22:62–65. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

37

|

Peng R, Huang Y, Huang P, Liu L, Cheng L and Peng X: The paradoxical role of transforming growth factor-β in controlling oral squamous cell carcinoma development. Cancer Biomark. 40:241–250. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zhang XL, Cheng YM and Zhu SL: P38 MAPK and pain sensitization. Zhonghua Zhongyiyao Xuekan. 29:3184–3187. 2014.(In Chinese).

|

|

39

|

Yang H, Cao C, Wu C, Yuan C, Gu Q, Shi Q and Zou J: TGF-βl suppresses inflammation in cell therapy for intervertebral disc degeneration. Sci Rep. 5(13254)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Dang CX, Zhu YJ, Bao YT, Yao LH and Gong YC: Research progress on the effect of p38-MAPK signaling pathway on skeletal muscle regeneration. J Jiangxi Sci Technol Normal Univ. 6:109–113. 2023.(In Chinese).

|

|

41

|

Chen JG and Zhu MF: Role of p38/JNK MAPK signaling pathway in Th cell differentiation. Zhonghua Zhongyiyao Xuekan. 27:2377–2378. 2009.(In Chinese).

|

|

42

|

Zhang Y, Wang L, Sun X and Li F: SERPINB4 promotes keratinocyte inflammation via p38MAPK signaling pathway. J Immunol Res. 2023(3397940)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wu M, Chen X, Lou J, Zhang S, Zhang X, Huang L, Sun R, Huang P, Wang F and Pan S: TGF-β1 contributes to CD8+ Treg induction through p38 MAPK signaling in ovarian cancer microenvironment. Oncotarget. 7:44534–44544. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Liu F: Study on the role and mechanism of MSCs paracrine TGF-β1 inducing macrophage polarization in sepsis (unpublished thesis). Southeast University, 2020 (In Chinese).

|

|

45

|

Huang TH: Study on the effect and mechanism of exosomes derived from bovine mammary epithelial cells on proliferation, apoptosis, and migration of bovine macrophages under TGF-β1 (unpublished thesis). Jilin University, 2019 (In Chinese).

|

|

46

|

Peng M: Research progress on macrophage polarization regulating inflammatory response. Adv Clin Med. 12:6796–6803. 2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

47

|

Yu H, Cui S, Mei Y, Li Q, Wu L, Duan S, Cai G, Zhu H, Fu B, Zhang L, et al: Mesangial cells exhibit features of antigen-presenting cells and activate CD4+ T cell responses. J Immunol Res. 2019(2121849)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Wang B, Hu J, Zhang J and Zhao L: Radiation therapy regulates TCF-1 to maintain CD8+T cell stemness and promotes anti-tumor immunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 107(108646)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Park IK, Shultz LD, Letterio JJ and Gorham JD: TGF-beta1 inhibits T-bet induction by IFN-gamma in murine CD4+ T cells through the protein tyrosine phosphatase Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1. J Immunol. 175:5666–5674. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Musiol S, Alessandrini F, Jakwerth CA, Chaker AM, Schneider E, Guerth F, Schnautz B, Grosch J, Ghiordanescu I, Ullmann JT, et al: TGF-β1 drives inflammatory T but not Treg cell compartment upon allergen exposure. Front Immunol. 12(763243)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Wu M, Lou JF, Huang PJ, Huang L, Sun RH, Pan SY and Wang F: Ovarian cancer cells promote the generation of CD8+ regulatory T cells through the P38 MAPK pathway. Basic Clin Med. 36:167–172. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

52

|

Sun Y, Xu W, Li D, Zhou H, Qu F, Cao S, Tang J, Zhou Y, He Z, Li H, et al: p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are involved in intestinal immune response to bacterial muramyl dipeptide challenge in Ctenopharyngodon idella. Mol Immunol. 118:79–90. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Yao J, Zhang J, Wang J, Lai Q, Yuan W, Liu Z, Cheng S, Feng Y, Jiang Z, Shi Y, et al: Transcriptome profiling unveils a critical role of IL-17 signaling-mediated inflammation in radiation-induced esophageal injury in rats. Dose Response. 20(15593258221104609)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Gong D, Shi W, Yi SJ, Chen H, Groffen J and Heisterkamp N: TGFβ signaling plays a critical role in promoting alternative macrophage activation. BMC Immunol. 13(31)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Jang YS, Kim JH, Seo GY and Kim PH: TGF-β1 stimulates mouse macrophages to express APRIL through Smad and p38MAPK/CREB pathways. Mol Cells. 32:251–255. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Zhang YE: Non-Smad pathways in TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 19:128–139. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Li B, Tan TB, Wang L, Zhao XY and Tan GJ: p38MAPK/SGK1 signaling regulates macrophage polarization in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Aging (Albany NY). 11:898–907. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Zhou Y, Wu J, Liu C, Guo X, Zhu X, Yao Y, Jiao Y, He P, Han J and Wu L: p38α has an important role in antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 15:246–259. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Jung ID, Lee JS, Kim YJ, Jeong YI, Lee CM, Lee MG, Ahn SC and Park YM: Sphingosine kinase inhibitor suppresses dendritic cell migration by regulating chemokine receptor expression and impairing p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Immunology. 121:533–544. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Iijima N, Yanagawa Y and Onoé K: Role of early- or late-phase activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase induced by tumour necrosis factor-alpha or 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene during maturation of murine dendritic cells. Immunology. 110:322–328. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Chen KW, Tong YL and Yao YM: Research progress on the role of regulatory T cells in tissue damage repair and their regulatory mechanisms. Chin J Burns. 35(828)2019.(In Chinese).

|

|

62

|

Zhang X, Fan L, Wu J, Xu H, Leung WY, Fu K, Wu J, Liu K, Man K, Yang X, et al: Macrophage p38α promotes nutritional steatohepatitis through M1 polarization. J Hepatol. 71:163–174. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Perdiguero E, Sousa-Victor P, Ruiz-Bonilla V, Jardí M, Caelles C, Serrano AL and Muñoz-Cánoves P: p38/MKP-1-regulated AKT coordinates macrophage transitions and resolution of inflammation during tissue repair. J Cell Biol. 195:307–322. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Fei C, Chen Y, Tan R, Yang X, Wu G, Li C, Shi J, Le S, Yang W, Xu J, et al: Single-cell multi-omics analysis identifies SPP1 (+) macrophages as key drivers of ferroptosis-mediated fibrosis in ligamentum flavum hypertrophy. Biomark Res. 13(33)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Huber S, Schrader J, Fritz G, Presser K, Schmitt S, Waisman A, Lüth S, Blessing M, Herkel J and Schramm C: P38 MAP kinase signaling is required for the conversion of CD4+CD25-T cells into iTreg. PLoS One. 3(e3302)2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

de Vries E, Sánchez E, Janssen D, Matthews D and van der Heide E: Predicting friction at the bone - Implant interface in cementless total knee arthroplasty. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 128(105103)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

de Bruijn I, Cheng X, de Jager V, Expósito RG, Watrous J, Patel N, Postma J, Dorrestein PC, Kobayashi D and Raaijmakers JM: Comparative genomics and metabolic profiling of the genus Lysobacter. BMC Genomics. 16(991)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Guan F, Wang R, Yi Z, Luo P, Liu W, Xie Y, Liu Z, Xia Z, Zhang H and Cheng Q: Tissue macrophages: Origin, heterogenity, biological functions, diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10(93)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Xiao N, Zhao Y, He W, Yao Y, Wu N, Xu M, Du H and Tu Y: Egg yolk oils exert anti-inflammatory effect via regulating Nrf2/NF-κB pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 274(114070)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Zhou XY, Wang LP, Li S, Gao HL, Zheng J and Liu SX: Clinical effect of modified Danzhen Oil in the treatment of acute radiation esophagitis. Clin Res Pract. 9:129–132. 2024.(In Chinese).

|

|

71

|

Guo J and Shi HJ: Clinical observation on the treatment of radiation esophagitis with Danzhen Oil in 60 patients. J Mod Oncol. 24:2085–2087. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

72

|

Lu S, Liu T, Zhu DD, Yu SJ, Lu LQ and Ding JJ: Research progress on liver fibrosis-related signaling pathways and corresponding anti-liver fibrosis drugs. J Clin Hepatol. 38:1161–1167. 2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

73

|

Gan L, Jiang Q, Huang D, Wu X, Zhu X, Wang L, Xie W, Huang J, Fan R, Jing Y, et al: A natural small-molecule alleviates liver fibrosis by targeting apolipoprotein L2. Nat Chem Biol. 21:80–90. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|