Introduction

Oral cancer is a significant public health issue,

with approximately 300,000 new cases reported annually worldwide

(1). Approximately 90% of oral

cancer pathologies are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Oral

squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) shows high incidence and mortality

rates, particularly in developing countries. Although the

development of treatment strategies has been remarkable, the 5-year

survival rate often remains below 50% (2). Despite the good local control of

OSCC, distant metastases often result in poor outcomes. In the

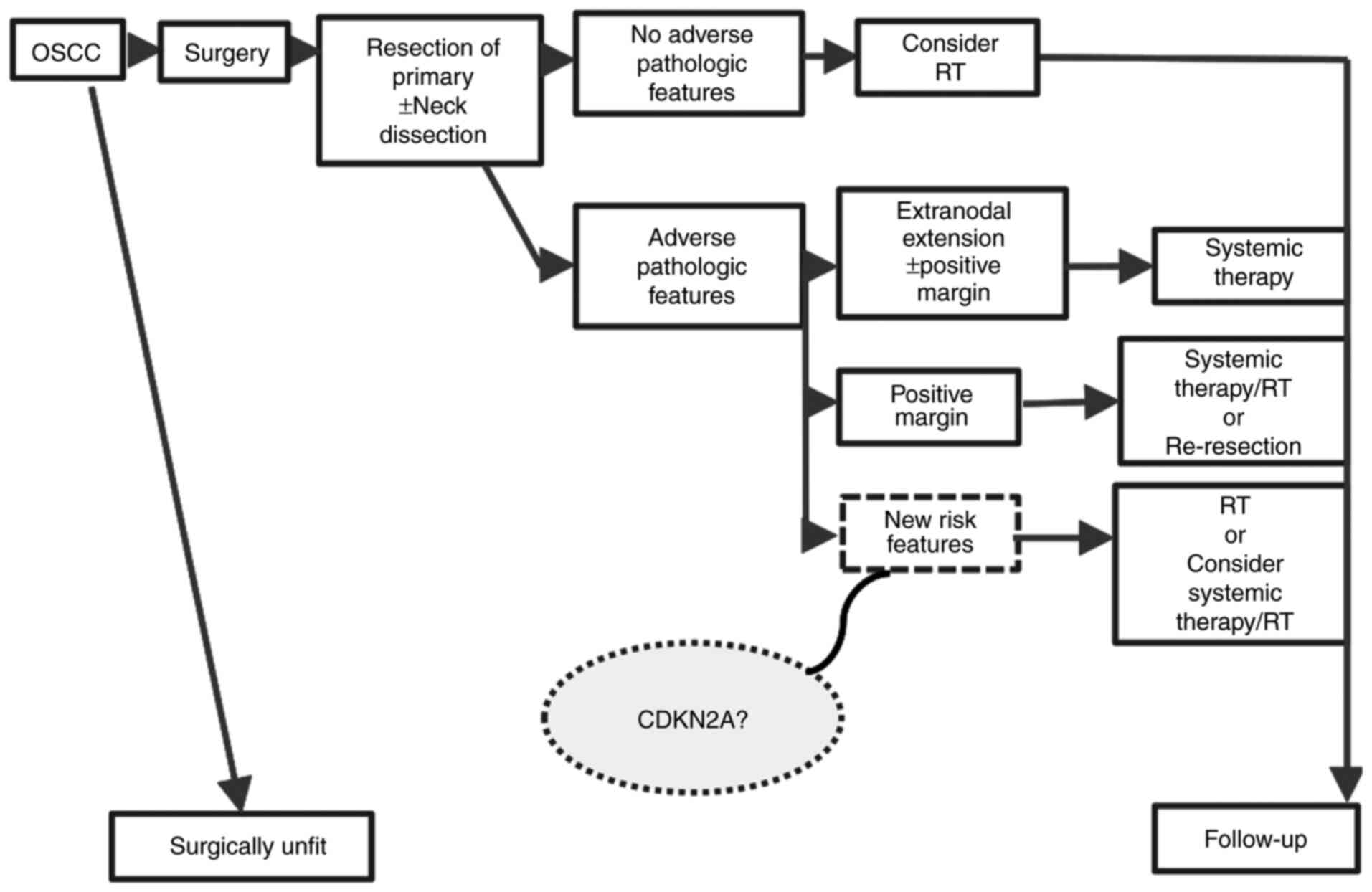

existing standard treatment regimen for OSCC, surgery is the first

choice, and chemoradiotherapy is strongly recommended as

postoperative adjuvant therapy in patients with a high risk of

postoperative recurrence. High-risk factors for recurrence include

T size, resection margin positivity, extranodal extension, and

multiple lymph node metastases. However, only a few factors can be

used to evaluate future metastasis.

Liquid biopsy has attracted attention for its

usefulness in various types of cancers, including colorectal and

breast cancers. Its utility in OSCC is anticipated. In a previous

study, associations were reported between the number of circulating

tumour cells (CTC) clusters and prognosis, as well as between the

size and quantity of cfDNA and prognosis (3). In this study, next-generation

sequencing (NGS) analysis of cfDNA was performed in two patients

with inferior prognoses due to distant metastases. They were

compared with mutation data from a clinical cancer panel test and

two commonly mutated genes were detected, TP53 and

CDKN2A, in both cases. CDKN2A and TP53 are

frequently mutated genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(HNSCC) (4) and OSCC (5). CDKN2A, or p16, is an essential

tumour suppressor gene that regulates cell growth by preventing the

progression from the G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle

(6). TP53 is a suppressor

gene referred to as ‘the guardian of the gene’. TP53 responds to

various cellular stresses to control the expression of target

genes, which subsequently trigger cell cycle arrest, apoptosis,

senescence, or DNA repair. The IHC for CDKN2A and TP53 in patients

with pathologically positive lymph node metastases were performed,

thereby offering a new prognostic feature for metastasis.

Materials and methods

cfDNA isolation and NGS

As reported previously (3), peripheral blood (PB) was obtained

from patients 1 and 2 prior to surgery; patient 1 (48 years old,

male, Tongue cancer, Stage IVA) and patient 2 (23 years old, male,

Tongue cancer, Stage IVA) were recruited in March and January 2023,

respectively, and the blood samples were collected at Hiroshima

University Hospital. cfDNA was extracted using the MagMAX cfDNA

isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)

following the manufacturer's protocol. NGS was carried out by

Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea) using the Axen Cancer Panel 2

(Table SI). First, shared mutated

genes were identified between cfDNA mutation data and tissue

mutation data from a clinical cancer panel test within the same

patient. Next, the commonalities between patients 1 and 2 were

determined. The clinical relevance of the variants was identified

using the ClinVar or OncoKB database (7).

Patients and specimens

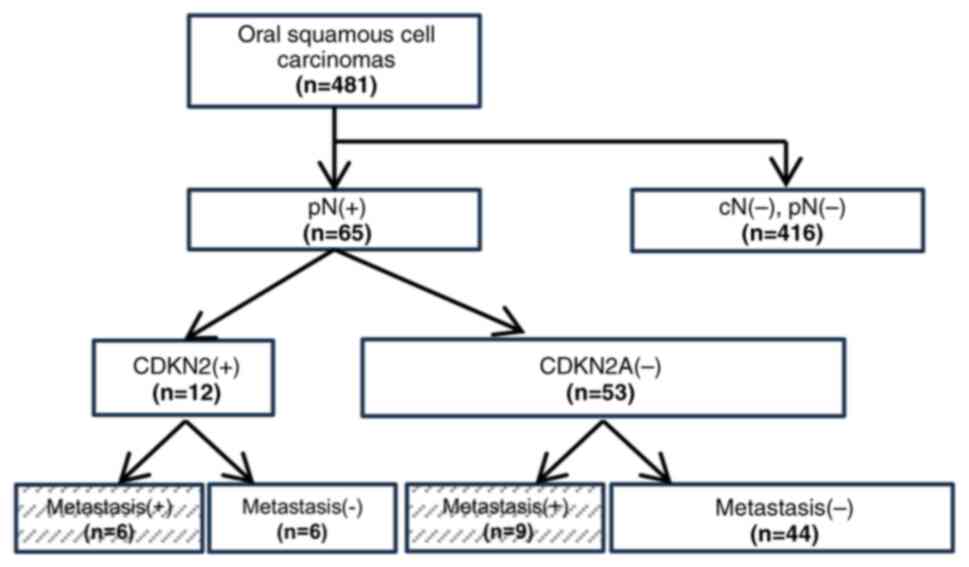

Overall, 537 patients with oral cancer visited the

Department of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery at Hiroshima University

Hospital between January 2014 and December 2023. Of them, 481

patients underwent radical surgery. Among the 481 patients, 65 with

pathologically positive lymphoid metastases (pN(+)) were selected

(Fig. 1) (Table SII). The medical records and

tissue samples of the patients included in this study were accessed

specifically for this research starting in May 2023. Inclusion

criteria included (1) absence of

distant metastases at diagnosis, (2) receipt of surgical treatment, and

(3) complete follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria included (1)

distant metastases at diagnosis, (2) non-surgical treatment, and (3) incomplete follow-up data. All medical

records, including disease characteristics, diagnostic methods, and

treatments, were retrospectively reviewed. All patients were

diagnosed according to the TNM classification of oral cancer

(8). The clinical endpoints of

this study were based on the FDA's ‘Clinical Trial Endpoints for

the Approval of Cancer Drugs and Biologics’ guidelines, which

include a 5-year evaluation period. The primary endpoint was

overall survival (OS). OS was defined as the time from the date of

the initial diagnosis to death from any cause.

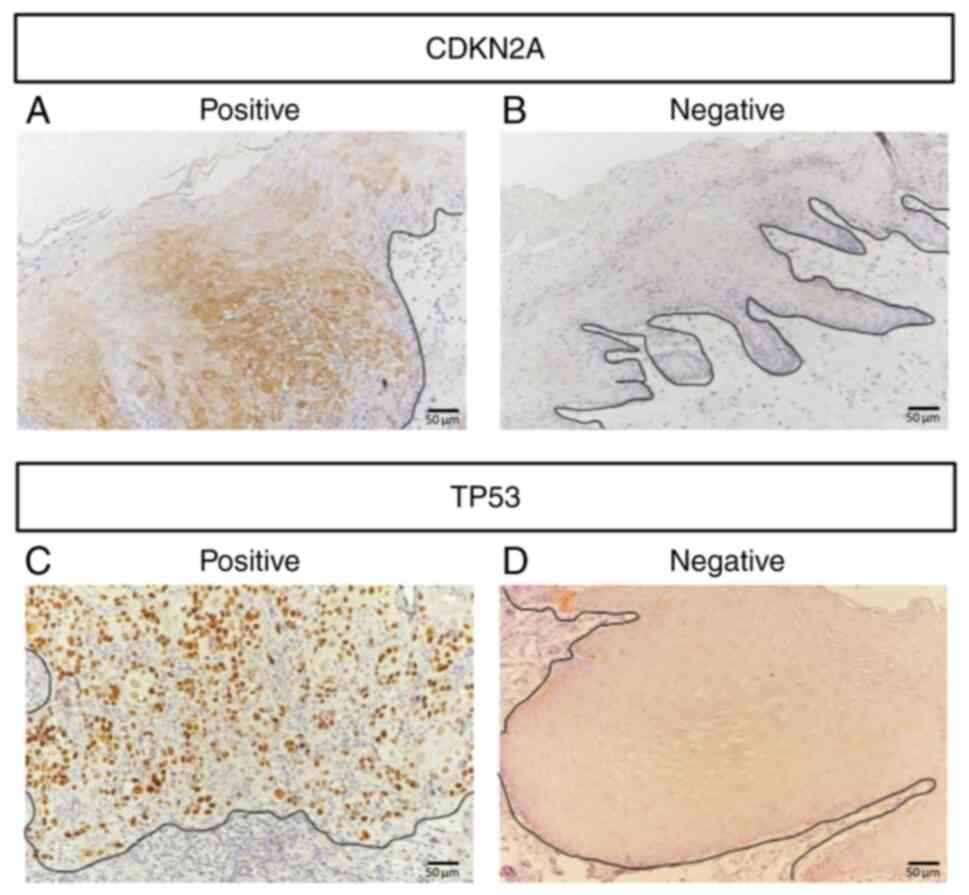

IHC for CDKN2A

IHC for CDKN2A was performed as previously described

(9). Briefly, 4-µm formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded tissue sections on amino silane-coated glass

slides (MATSUNAMI, Osaka, Japan) were deparaffinised in xylene

(FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) and

rehydrated using an alcohol gradient (FUJIFILM Wako). Antigen

retrieval was performed using 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0)

in an autoclave (HV-5; HIRAYAMA, Saitama, Japan). Sections were

incubated overnight at 4˚C with a 1:100 dilution of mouse

monoclonal anti-CDKN2SA/p16INK4A antibody (sc-56330, Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, TX, USA) or a 1:100 dilution of mouse monoclonal

anti-p53 antibody (DO-1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Detection was

performed using EnVision+ System-HRP anti-mouse (Dako, Agilent

Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) for 30 min, followed by

visualisation with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Dako) and

counterstaining with haematoxylin (FUJIFILM Wako). The slides were

dehydrated, mounted, and covered with coverslips (NEO cover glass;

MATSUNAMI). Images were captured using a Nikon DS-Ri2 camera (Nikon

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope

(Nikon Corporation).

Classification of IHC positivity

Immunohistochemical staining was evaluated based on

the intensity and percentage of positively stained cells. Cases

were considered ‘positive’ when the CDKN2A-positive region was

expressed more than 70%, and the TP53-positive region was expressed

more than 60%, according to previously reported thresholds

(10-12).

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Hiroshima University (approval numbers: epidemiology 2016-9191 and

epidemiology 2023-0025).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP

Pro (version 16.2.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The

association between OS and factors and the IHC results of

CDKN2A/TP53 expression and OS were examined using Kaplan-Meier

survival curves and the log-rank test. To further assess the

prognostic significance of CDKN2A positivity, a multivariate Cox

proportional hazards regression analysis was performed.

Results

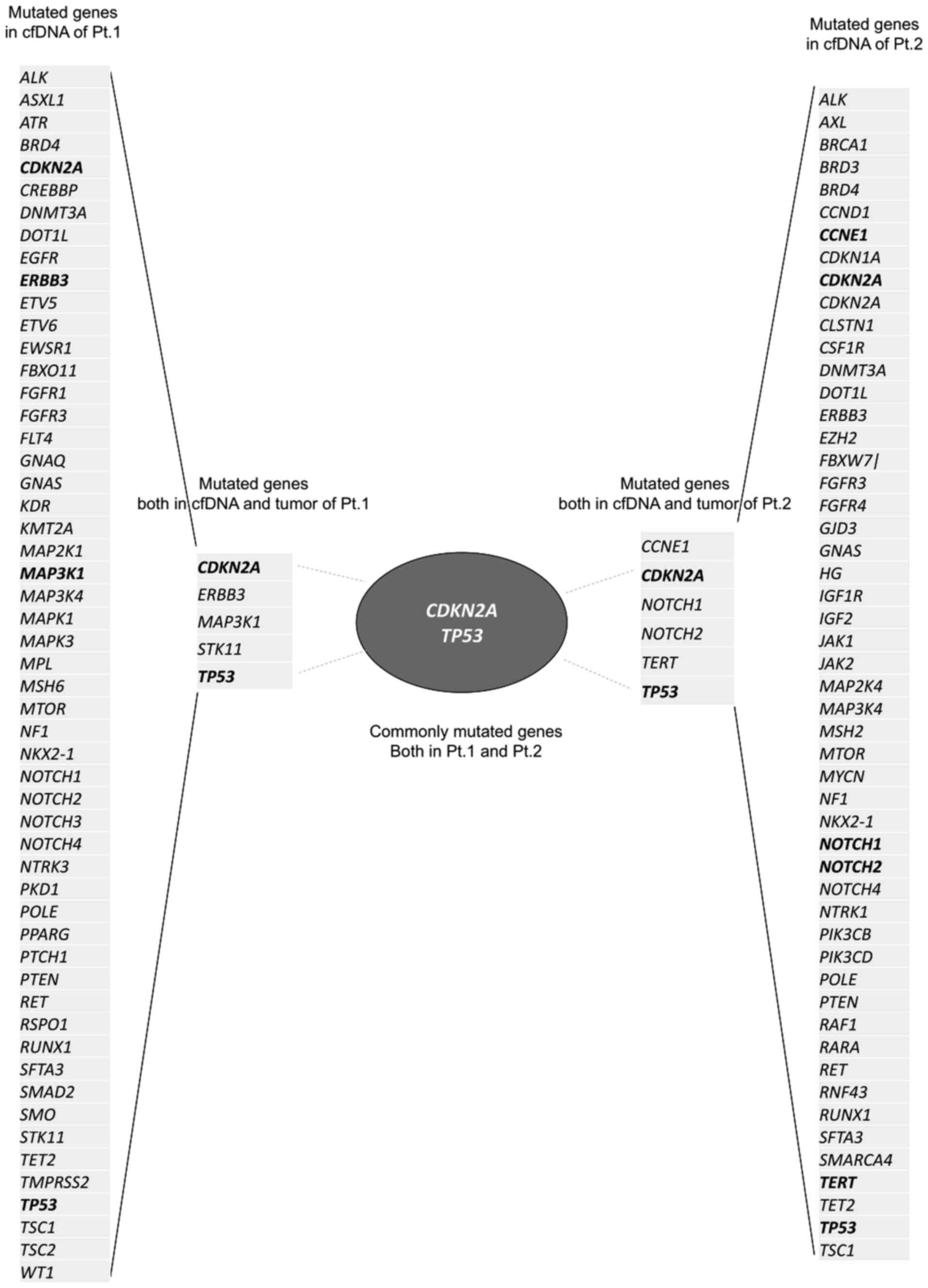

Result of NGS

cfDNA NGS was performed for patients 1 and 2 as

preliminary exploratory observations. Forty-one and 40 genetic

mutations were detected in cfDNAs of patients 1 and 2,

respectively. Some common tumour tissue mutations were previously

detected in each patient. CDKN2A, ERBB3,

MAP3K1, STK11, and TP53 were common mutations

identified in patient 1. In patient 2, CCNE1, CDKN2A,

NOTCH1, NOTCH2, TERT, and TP53 were

common between tissues and cfDNA. Among these, two genes,

CDKN2A and TP53, were shared between patients 1 and 2

(Fig. 2). Specifically,

TP53_c.524G>A_p.R175H/CDKN2A_ c.340C>T_p. P114 and

TP53_c.569delC_p.P190fs*57, _c.733G>A

_p.G245S/CDKN2A_c.247C>A_p. H83N were shared both in tumour

tissue and cfDNA, respectively, in patients 1 and 2 (Table I). Although the positions of the

mutated base differed between patients 1 and 2, they were all

pathological mutations. Therefore, the relationship between IHC

staining for CDKN2A and TP53 and OSCC prognosis was

investigated.

| Table ITP53 and CDKN2A mutations in cfDNA and

tumour. |

Table I

TP53 and CDKN2A mutations in cfDNA and

tumour.

| Patient no. | Origin | Gene | Protein change | Annotation | AF (%) |

|---|

| 1 | Tumour | TP53 | R175H | Pathogenic | 62.8 |

| | | CDKN2A | P114S | Pathogenic/VUS | 58.1 |

| | cfDNA | TP53 | R175H | Pathogenic | 1.6 |

| | | | G245D | Pathogenic | 0.3 |

| | | CDKN2A | P114S | Pathogenic/VUS | 1.8 |

| 2 | Tumour | TP53 | P190fs*57 | Pathogenic | 28.5 |

| | | | G245S | Pathogenic | 12.3 |

| | | CDKN2A | H83N | Likely

Pathogenic | 56 |

| | cfDNA | TP53 | P190fs*57 | Pathogenic | 14.3 |

| | | | G245S | Pathogenic | 6.7 |

| | | CDKN2A | H83N | Likely

pathogenic | 24.3 |

| | | | G89C | VUS | 23.2 |

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the 65 patients with SCC

included in this study are summarised in Table II. Of the 65 patients, 43 (66.2%)

were males and 22 (33.8%) were females; the average age was 68

years. The primary tumour sites included the tongue (32.3%),

mandibular gingiva (27.7%), the floor of the mouth (16.9%), buccal

mucosa (10.8%), maxillary gingiva (10.8%), and others (1.5%).

Tumour size distribution showed that 17 patients (26.2%) had

Tis/T1/T2 tumours, and 48 patients (73.8%) had T3/T4 tumours.

| Table IIPatient characteristics. |

Table II

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Number | % |

|---|

| Age (median),

years | 68 (21-89) | - |

| Sex | | - |

|

Male | 43 | 66.2 |

|

Female | 22 | 33.8 |

| Site | | |

|

Tongue | 21 | 32.3 |

|

Mandibular

gingiva | 18 | 27.7 |

|

Floor of

mouth | 11 | 16.9 |

|

Buccal

mucosa | 7 | 10.8 |

|

Maxillary

gingiva | 7 | 10.8 |

|

Other | 1 | 1.5 |

| Tumour size | | |

|

Tis/T1-2 | 17 | 26.2 |

|

T3-4 | 48 | 73.8 |

| Metastasis | | |

|

No | 49 | 75.4 |

|

Yes | 16 | 24.6 |

CDKN2A-positive group shows metastasis

in 50% of OSCC cases

IHC images were assessed, as shown in Fig. 3. CDKN2A expression was positive in

12 patients (18.5%) and negative in 53 (81.5%). Of the

CDKN2A-positive and CDKN2A-negative patients, six (6/12, 50%) and

nine (9/53, 16.9%) showed metastasis (Fig. 1). In the Fisher's exact test for

distant metastasis, the IHC CDKN2A-positive group showed a

significantly higher metastasis rate (Table III).

| Table IIIFisher's exact test for distant

metastasis and other factors. |

Table III

Fisher's exact test for distant

metastasis and other factors.

| Characteristic | No metastasis, n

(%) | Metastasis, n

(%) | Total, n (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex | | | | |

|

Male | 32 (49.2) | 10 (15.4) | 42 (62.6) | 1.0 |

|

Female | 18 (27.7) | 5 (7.7) | 23 (35.4) | |

| Age | | | | |

|

≤65 | 23 (35.4) | 3 (4.6) | 26 (40.0) | 0.06 |

|

>65 | 27 (41.5) | 12 (18.5) | 39 (60.0) | |

| Tumor size | | | | |

|

Tis/T1-T2 | 15 (23.1) | 2 (3.1) | 17 (26.2) | 0.2 |

|

T3-T4 | 35 (53.9) | 13 (20.0) | 48 (73.9) | |

| IHC (TP53) | | | | |

|

Negative | 29 (44.6) | 7 (10.8) | 36 (55.4) | 0.46 |

|

Positive | 21 (32.3) | 8 (12.3) | 29 (44.6) | |

| IHC (CDKN2A) | | | | |

|

Negative | 44 (67.7) | 9 (13.9) | 53 (81.5) | 0.046 |

|

Positive | 6 (9.2) | 6 (9.2) | 12 (18.5) | |

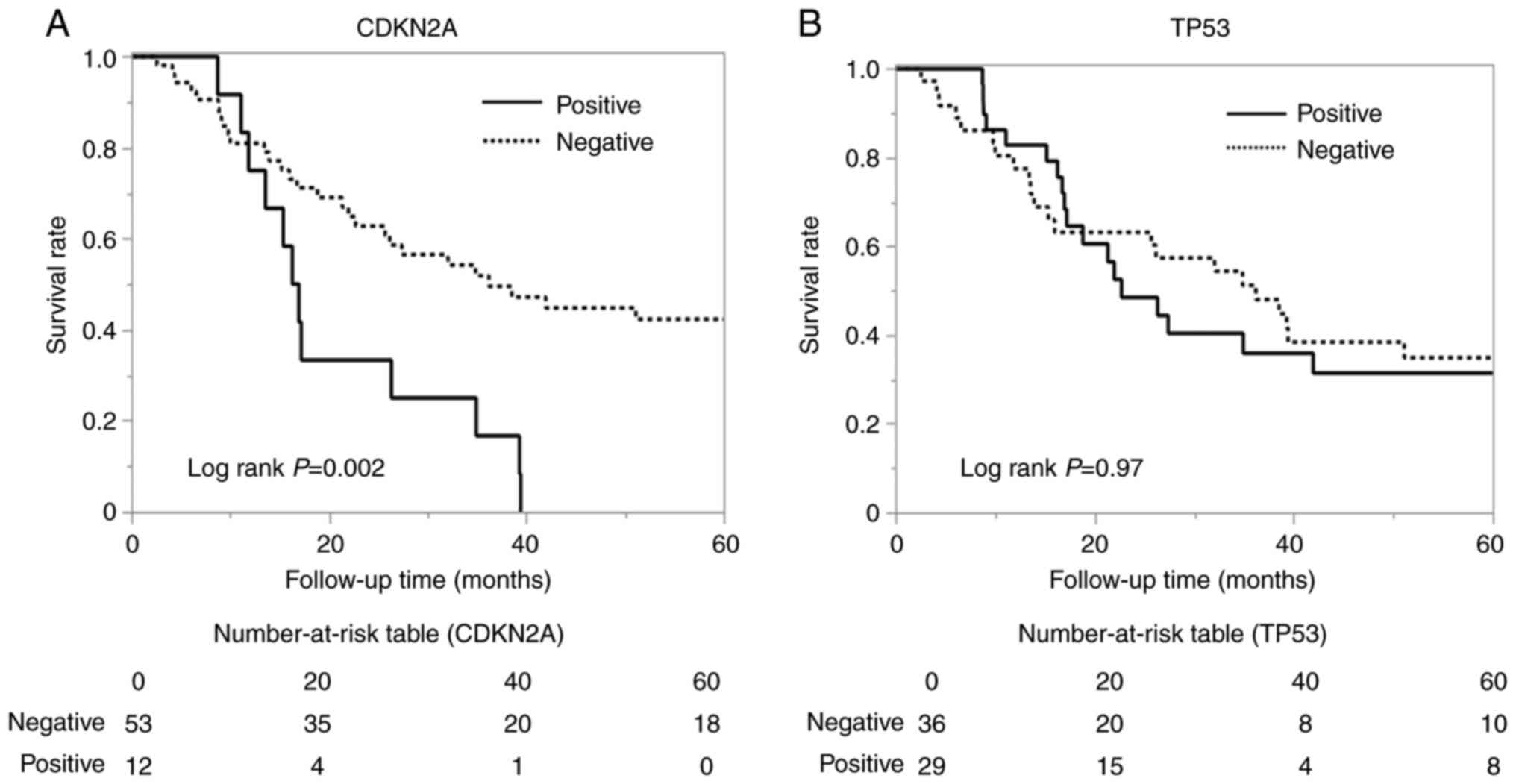

CDKN2A-positive group shows shorter OS

in OSCC

Five-year survival rates were examined based on the

positive and negative immunohistochemical results for CDKN2A and

TP53. The CDKN2A-positive group showed a significantly decreased

survival rate (hazard ratio=3.63, 95% CI: 1.36-9.68, P=0.01)

(Fig. 4A), but there were no

significant differences for TP53 (Fig.

4B). Furthermore, the results of the multivariate cox

proportional hazards model indicated that CDKN2A positivity

remained a significant independent predictor of poor prognosis

after adjusting IHC results, age, smoking history, alcohol dose,

and tumour size (hazard ratio=1.75, 95% CI: 017-1.60,

P-value=0.0179) (Table IV).

| Table IVMultivariable cox proportional

hazards model for overall survival. |

Table IV

Multivariable cox proportional

hazards model for overall survival.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| P16 positivity ≥70%

(yes vs. no) | 1.75 | 0.17-1.60 | 0.0179 |

| TP53 positivity

≥60% (yes vs. no) | 0.01 | -0.64-0.64 | 0.9787 |

| Age >60 years

(yes vs. no) | 0.95 | -0.12-1.16 | 0.1126 |

| Smoking history

(never vs. ever) | 0.27 | -0.56-1.22 | 0.5321 |

| Alcohol dose (never

vs. ever) | 0.05 | -0.95-1.01 | 0.8980 |

| T stage (T1-2 vs.

T3-4) | 0.13 | -0.72-0.55 | 0.7415 |

Discussion

This study was designed based on the commonalities

of tumour tissue and cfDNA sequencing data to identify new

prognostic features of metastasis. Most of the mutations detected

in cfDNA sequencing are not pathogenic mutations. However, a few

pathogenic mutated genes, TP53 and CDKN2A, were

common in both tumour tissues and cfDNA. TP53_p.R175H/_p.G245S

mutation, previously reported pathogenic variant, is located in the

DNA binding domain, resulting in loss of function. TP53_p.R175H is

found in acute myeloid leukaemia (13). TP53_p.G245S has been frequently

found in hepatocellular carcinoma (14). TP53_p.P190fs*57 is a truncated

mutation, resulting in the loss of function. Those truncated

mutations show a relatively strong association with poor prognosis

in HNSCC (15). CDKN2A_p.

P114S/_p. H83N mutation is located in the ankyrin repeats of the

p16/INK4A protein, resulting in loss of function. CDKN2A_p. P114S,

previously reported pathogenic variant, was identified as a

germline variant in families affected by melanoma (16). Though TP53_c.569delC_p.P190fs*57

and CDKN2A_c.247C>A_p. H83N are not reported mutations, they are

predicted as pathogenic mutation in silico analysis using mutation

taster (https://www.mutationtaster.org/index.html).

cfDNA was previously assessed at two points, pre-

and post-operation, and reported that the group with distant

metastases showed significantly higher amounts of cfDNA than those

without distant metastases both preoperatively and postoperatively

(3). In reference 3, we showed

that though only three genes (TP53, HRAS, and MLH1) were classified

as pathogenic in 13 patients, two patients, who commonly possessed

TP53_c.215C>G_p.Pro72Arg, showed short-term distant metastasis.

Despite the limited overlap in mutations among patients, these

findings underscore the clinical relevance of cfDNA mutation

profiling (3). If the same genetic

mutations in cfDNA can be detected both preoperatively and

postoperatively or the comparison of those genetic mutations can be

performed, it would further support the clinical relevance of such

findings.

Specifically, the relationship between CDKN2A/TP53

IHC expression and prognosis was investigated in 65 patients with

pN(+) OSCC. pN(+) was selected to evaluate the high-risk group for

metastasis because, as commonly reported, the pN(+) group had a

higher distant metastasis rate of 22% (15/65), than those of the

pN(-) group, 5% (2/40) (Table

SII). The following were key findings: in 65 patients with

pN(+) OSCC, CDKN2A expression was positive in 18.5% (12/65) of the

patients and negative in 81.5% (53/65), whereas no such difference

was found for TP53. The CDKN2A-positive group resulted in

metastasis in 50% of cases (6/12). This result contradicts our

expectations. Regarding the oropharynx, Fakhry et al

(17) assessed whether HPV

infection was present or absent and concluded that the HPV-positive

group (CDKN2A-positive group) in the oropharynx had a better

prognosis, showing better radiosensitivity. This present case may

have been different because it consisted of 86.2% (56/65) cases of

surgical alone and 13.8% (9/65) surgical plus adjuvant radiation

therapy with or without chemotherapy. Hong et al (18) reported that, in oropharyngeal

cancer, while surgery alone cases were deemed insufficient in

number for their multivariable analysis, HPV status predicts better

outcomes treated with surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy as well as

with definitive radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. In

Fakhry et al (17) and Hong

et al (18), the assessment

was not based on IHC-CHKN2A negativity or positivity but also

considered the presence of HPV16 DNA using in situ hybridisation or

PCR. Ni et al (19)

reported that CDKN2A overexpression decoupled from HPV infection

was not a prognostic marker for patients with OSCC.

CDKN2A is widely recognised as a tumour

suppressor gene that controls cell proliferation by preventing the

progression from the G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle

(20). In normal cells with

proliferative potential, the expression of CDKN2A is very low, and

CDKN2A has little function. However, when normal cells reach the

mitotic lifespan or undergo oncogenic stress, CDKN2A gene

expression is markedly elevated, and cellular senescence occurs

(21). Beyond phenomena related to

invasion and metastasis, Shi et al (22), reported that in the colorectal

cancer cell line, HT-29, CDKN2A could induce the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, showing that knock downed CDKN2A

expression was followed by enhanced E-cadherin expression and

suppression of N-cadherin and vimentin expression. Cheng et

al (23), reported that CDKN2A

mediates cuproptosis, a type of cell death characterised by

excessive copper-lipid reactions in the tricarboxylic acid cycle,

resistance through regulating glycolysis and copper homeostasis,

accompanied by a malignant phenotype and pro-tumour niche, also

using colorectal cancer cell line. They concluded that radiation

and chemotherapy are expected to potentially serve as therapeutic

approaches for cuproptosis-resistant colorectal cancer with high

CDKN2A expression (23). Given the

limited literature investigating these phenomena in OSCC, future

studies should aim to 1) elucidate the molecular pathways by which

CDKN2A influences cell motility, epithelial-mesenchymal transition,

and invasion using in vitro OSCC models 2) evaluate

metastatic potential in vivo between CDKN2A-over expressing

and CDKN2A-deficient OSCC xenografts 3) use single-cell

transcriptomics or proteomics analyses to gain deeper insight into

how CDKN2A expression modulates cellular behavior at the invasive

front of OSCC lesions.

Despite these promising findings, the limitations of

this study warrant further consideration. First, the retrospective

nature of this study might have induced selection bias, as only

patients who underwent surgery and had available pathology reports

were included. Second is the lack of HPV status assessment. Since

CDKN2A (p16) overexpression is often considered a surrogate marker

for HPV-related oncogenesis, especially in head and neck cancers,

the inability to account for HPV infection status may confound the

interpretation of CDKN2A expression in this cohort. Although the

prognostic significance of CDKN2A expression has been well

established in oropharyngeal cancers, particularly in HPV-positive

cases, less attention has been given to CDKN2A's role in OSCC. Most

studies focus on the strong association between p16 expression and

HPV status in oropharyngeal cancer, where p16 overexpression is

often considered a surrogate marker for HPV infection. However,

OSCC, which is primarily HPV-negative, presents a different

biological context. Future studies should incorporate HPV testing

to better clarify this relationship. This study addresses this gap

by investigating the independent role of CDKN2A expression in OSCC,

irrespective of HPV infection. Evidence that CDKN2A dysregulation

in OSCC may be associated with tumour progression, metastasis, and

poorer prognosis was provided, independent of HPV status. This

finding is particularly important as it expands the understanding

of CDKN2A as a prognostic marker in head and neck cancers beyond

HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers. Results suggest that CDKN2A

could serve as a valuable biomarker in OSCC, offering insights into

its potential role in cancer progression and therapeutic targeting.

Third is the sample size. Because the sample size is very small,

two samples for NGS and twelve samples for IHC CDKN2A-positive

patients, these results should be seen as preliminary and

interpreted with caution. Although further studies involving a

larger patient cohort are necessary to confirm these preliminary

observations, these findings suggest a potential prognostic role

for CDKN2A expression. Assessing CDKN2A expression could help

stratify patients based on their risks and tailor treatment

strategies accordingly. For example, the CDKN2A-positive group,

which we assumed to be a high-metastasis group, could be managed

with more aggressive treatment regimens or closer follow-up.

Further research will contribute to the development of personalised

cancer therapies and improve OSCC prognosis (Fig. 5).

This study addresses this gap by investigating the

independent role of CDKN2A expression in OSCC, irrespective of HPV

infection. We provide evidence that CDKN2A dysregulation in OSCC

may be associated with tumour progression, metastasis, and poorer

prognosis, independent of HPV status. This finding is particularly

important as it expands the understanding of CDKN2A as a prognostic

marker in head and neck cancers beyond HPV-positive oropharyngeal

cancers. The results suggest that CDKN2A could serve as a valuable

biomarker in OSCC, offering insights into its potential role in

cancer progression and therapeutic targeting. In conclusion, this

study demonstrates that the CDKN2A-positive group had a high

metastasis rate, resulting in a poorer prognosis. CDKN2A expression

is a potential prognostic marker for OSCC.

Supplementary Material

Genes included in Cancer Axen Panel

2.

Patient characteristics.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor T. Hinoi, Dr H. Niitsu

and Dr H. Nakahara (Department of Clinical and Molecular Genetics,

Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan) for kindly

allowing us to share the clinical cancer panel test and advising us

for the ethical application.

Funding

Funding: This research was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid

for Scientific Research (B) (grant no. 22H03292), Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (C) (grant no. 22K10146), and Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (C) (grant no. 22K10148) from the Japanese

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The following three

mutations, NM_000546.6(TP53):c.524G>A (p.Arg175His),

NM_000546.6(TP53):c.733G>A (p.Gly245Ser) and

NM_000077.5(CDKN2A):c.340C>T (p.Pro114Ser), are reported

mutations and their URLs are as follows, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000013173.22/,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/12365/,

and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV001915587/,

respectively. The NGS data have been deposited with links to

Biosample accession number SAMD01605716 (patient 1) and

SAMD01611905 (patient 2) in the DDBJ Biosample database, https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/search/entry/biosample/SAMD01605716

and https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/search/entry/biosample/SAMD01611905.

Authors' contributions

SoY and AH designed the experiments. NE, AH, AT, MH,

FO, NI, SaY, RT, TS, KK and SoY performed the experiments. NE, AH

and SoY confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data, and wrote

and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Research Ethics Board of Hiroshima University

approved this study. The studies were conducted in accordance with

the local legislation and institutional requirements. Patients 1

and 2 provided written informed consent to participate in the

study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hiroshima

University (approval no. epidemiology 2016-9191). For IHC, written

informed consent was not obtained from patients for publication

because this was a retrospective study. This retrospective

observational study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of

Hiroshima University (approval no. epidemiology 2023-0025).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M,

Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I and Bray F:

Global cancer observatory: Lip, oral cavity. International Agency

for Research on Cancer, Lyon, 2024. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/en/fact-sheets-cancers.

|

|

2

|

Bosetti C, Carioli G, Santucci C,

Bertuccio P, Gallus S, Garavello W, Negri E and La Vecchia C:

Global trends in oral and pharyngeal cancer incidence and

mortality. Int J Cancer. 147:1040–1049. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Eboshida N, Hamada A, Higaki M, Obayashi

F, Ito N, Yamasaki S, Tani R, Shintani T, Koizumi K and Yanamoto S:

Potential role of circulating tumor cells and cell-free DNA as

biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinoma: A prospective

single-center study. PLoS One. 19(e0309178)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Morris LGT, Chandramohan R, West L, Zehir

A, Chakravarty D, Pfister DG, Wong RJ, Lee NY, Sherman EJ, Baxi SS,

et al: The molecular landscape of recurrent and metastatic head and

neck cancers: Insights from a precision oncology sequencing

platform. JAMA Oncol. 3:244–255. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Saito Y, Kage H, Kobayashi K, Yoshida M,

Fukuoka O, Yamamura K, Mukai T, Oda K and Yamasoba T: TERT promoter

mutation positive oral cavity carcinomas, a clinically and

genetically distinct subgroup of head and neck squamous cell

carcinomas. Head Neck. 45:3107–3118. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Rayess H, Wang MB and Srivatsan ES:

Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int J Cancer.

130:1715–1725. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown GR,

Chao C, Chitipiralla S, Gu B, Hart J, Hoffman D, Jang W, et al:

ClinVar: Improving access to variant interpretations and supporting

evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (D1):D1062–D1067. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O'Sullivan B,

Brandwein MS, Ridge JA, Migliacci JC, Loomis AM and Shah JP: Head

and Neck cancers-major changes in the American joint committee on

cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:122–137. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Nguyen TQ, Hamada A, Yamada K, Higaki M,

Shintani T, Yoshioka Y, Toratani S and Okamoto T: Enhanced KRT13

gene expression bestows radiation resistance in squamous cell

carcinoma cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 57:300–314.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Shelton J, Purgina BM, Cipriani NA, Dupont

WD, Plummer D and Lewis JS Jr: p16 immunohistochemistry in

oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A comparison of antibody

clones using patient outcomes and high-risk human papillomavirus

RNA status. Mod Pathol. 30:1194–1203. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ribeiro EA and Maleki Z: p16

immunostaining in cytology specimens: Its application, expression,

interpretation, and challenges. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 10:414–422.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Yamaji T,

Loda M and Fuchs CS: Loss of nuclear p27 (CDKN1B/KIP1) in

colorectal cancer is correlated with microsatellite instability and

CIMP. Mod Pathol. 20:15–22. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Loizou E, Banito A, Livshits G, Ho YJ,

Koche RP, Sánchez-Rivera FJ, Mayle A, Chen CC, Kinalis S, Bagger

FO, et al: A gain-of-function p53-mutant oncogene promotes cell

fate plasticity and myeloid leukemia through the pluripotency

factor FOXH1. Cancer Discov. 9:962–979. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Yu X, Mao SQ, Shan YY, Huang Y, Wu SD and

Lu CD: Predictive value of the TP53. p.G245S mutation frequency for

the short-term recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma as detected

by pyrophosphate sequencing. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 26:476–484.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lindenbergh-van der Plas M, Brakenhoff RH,

Kuik DJ, Buijze M, Bloemena E, Snijders PJ, Leemans CR and

Braakhuis BJ: Prognostic significance of truncating TP53 mutations

in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res.

17:3733–3741. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kannengiesser C, Brookes S, del Arroyo AG,

Pham D, Bombled J, Barrois M, Mauffret O, Avril MF, Chompret A,

Lenoir GM, et al: Functional, structural, and genetic evaluation of

20 CDKN2A germ line mutations identified in melanoma-prone families

or patients. Hum Mutat. 30:564–574. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge

JA, Pinto H, Forastiere A and Gillison ML: Improved survival of

patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous

cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst.

100:261–269. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hong AM, Dobbins TA, Lee CS, Jones D,

Harnett GB, Armstrong BK, Clark JR, Milross CG, Kim J, O'Brien CJ

and Rose BR: Human papillomavirus predicts outcome in oropharyngeal

cancer in patients treated primarily with surgery or radiation

therapy. Br J Cancer. 103:1510–1517. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ni Y, Zhang X, Wan Y, Dun Tang K, Xiao Y,

Jing Y, Song Y, Huang X, Punyadeera C and Hu Q: Relationship

between p16 expression and prognosis in different anatomic subsites

of OSCC. Cancer Biomark. 26:375–383. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Liggett WH Jr and Sidransky D: Role of the

p16 tumor suppressor gene in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 16:1197–1206.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hara E, Smith R, Parry D, Tahara H, Stone

S and Peters G: Regulation of p16CDKN2 expression and its

implications for cell immortalization and senescence. Mol Cell

Biol. 16:859–867. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Shi WK, Li YH, Bai XS and Lin GL: The cell

cycle-associated protein CDKN2A may promotes colorectal cancer cell

metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Front

Oncol. 12(834235)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Cheng X, Yang F, Li Y, Cao Y, Zhang M, Ji

J, Bai Y, Li Q, Yu Q and Gao D: The crosstalk role of CDKN2A

between tumor progression and cuproptosis resistance in colorectal

cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 16:10512–10538. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Joint Committee for the Revision of the

Japanese Oral Cancer Treatment Guidelines: The Clinical Practice

Guidelines for Oral Cancer. Kanehara & Co., Ltd., Tokyo,

pp19-62, 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0901502724004466.

|