1. Introduction

Cancer, characterized by the uncontrolled

proliferation and spread of abnormal cells, remains one of the

world's most pervasive and deadly diseases. While advancements in

therapy have improved outcomes for certain patients, several

patients exhibit recurrent or refractory disease, primarily due to

drug resistance. This phenomenon, where cancer cells evolve to

evade the effects of chemotherapy, targeted therapy or

immunotherapy, remains a major barrier to long-term treatment

success.

Among the several types of cancer, brain tumors are

particularly lethal. Annually, over 300,000 new cases of brain

cancer are diagnosed globally, leading to >250,000 deaths. In

the United States alone, an estimated 25,400 new brain tumor cases

and ~19,000 deaths were predicted in 2024(1). Brain tumors are also the leading

cause of cancer-related deaths in children and adolescents under

the age of 19(2). The 5-year

relative survival rate for brain and other nervous system cancers

in the U.S. stands at ~34%, highlighting the urgent need for

improved detection and more effective therapies (1).

Despite the ongoing development of therapeutics,

brain cancer remains among the most difficult malignancies to

treat. This is largely due to the aggressive biology of the disease

and the unique challenges posed by the brain's protective

environment. The blood-brain barrier (BBB), while essential for

maintaining neural homeostasis, limits the penetration of most

chemotherapeutic and biologic agents, posing a major hurdle for

effective drug delivery.

Treatment strategies for brain tumors include

chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Temozolomide

(TMZ), an oral alkylating agent, remains the cornerstone of

chemotherapeutic regimens, supplemented by agents such as

carmustine, lomustine, vincristine, procarbazine and etoposide.

Targeted agents like vorasidenib [isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1/2

inhibitor] and bevacizumab [BEV, a vascular endothelial growth

factor (VEGF) inhibitor] have shown utility in specific subtypes.

Immunotherapeutics, including anti-PD-1 antibodies pembrolizumab

and nivolumab, are under active investigation in clinical trials,

particularly for GBM.

GBM, the most common and aggressive malignant brain

tumor, accounts for ~50% of all primary malignant brain tumors. It

exhibits a particularly poor prognosis due to its rapid progression

and formidable resistance to existing therapies. The 5-year

survival rate for GBM remains at a dismal 7% (3,4),

reflecting the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies.

The aim of the present review is to provide a

comprehensive and integrative analysis of the molecular and

cellular mechanisms driving therapeutic resistance in GBM, with a

focus on emerging and underappreciated pathways such as exosomal

non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), metabolic reprogramming and dysregulated

signaling networks [such as the Wnt/β-catenin, Hippo, PI3K/Akt and

MAPK]. Importantly, beyond being merely a descriptive overview, the

therapeutic implications of these mechanisms, including how they

might be exploited for combination regimens, drug delivery

innovations and precision medicine approaches, are also discussed.

By bridging mechanistic insights with actionable strategies, the

present review seeks to support the development of more effective,

resistance-overcoming treatments for GBM, ultimately improving

clinical outcomes in this intractable disease.

2. BBB

BBB is a dynamic interface that regulates molecular

transport between systemic circulation and brain parenchyma. While

essential for neuroprotection, its structural and functional

complexity poses significant challenges for treating brain tumors.

The structural organization of the BBB plays a crucial role in its

function as a selective and protective interface between the

systemic circulation and the brain. Its key structural components

contribute to its function through the following ways:

Endothelial cells and tight junctions (TJs).

Brain microvascular endothelial cells form the primary barrier with

TJs composed of claudins, occludins and zonula occludens proteins.

These TJs create a high trans-endothelial electrical resistance

(>1,800 Ω·cm²), restricting paracellular passage of polar

molecules and toxins (5).

Bicellular (claudin-5) and tricellular (angulin-1) junctions

further regulate permeability.

Supporting cellular components. Pericytes

stabilize endothelial junctions via platelet-derived growth factor

receptor (PDGFR)-β signaling, and their loss leads to barrier

leakage, especially in gliomas (6). Astrocytes cover >99% of the

endothelial surface, and along with pericytes, maintain BBB

integrity. Microglia modulate the BBB but can also disrupt it by

secreting inflammatory cytokines.

Basement membrane. The 50-100 nm

extracellular matrix, rich in collagen IV and laminins, provides

structural support and regulates leukocyte trafficking, ensuring

vascular stability and selective permeability. These structural

elements collectively restrict solute exchange, regulate selective

transport and maintain homeostasis, which are essential for

neuroprotection. However, these same features significantly

contribute to drug resistance in GBM through several mechanisms

(7).

Heterogeneous BBB disruption. In brain

tumors, the BBB has leaky regions but retains an intact BBB in

non-enhancing tumor areas, creating sanctuaries for cancer cells

(8). In high-grade glioma (HGG)

tumors, surgical and imaging data show that tumor cells extend

beyond contrast-enhancing MRI regions, with PET tracers confirming

metabolic activity in these areas, indicating BBB integrity. Drug

penetration studies reveal poor delivery of several therapies to

non-enhancing tumor regions due to active efflux transporters.

Additionally, imaging-pathology mismatches highlight that

abnormalities on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion

recovery (FLAIR) MRI sequences, which are sensitive to edema and

infiltrative tumor regions, represent infiltrative tumors without

sufficient BBB disruption for effective drug delivery. Clinically,

most GBM recurrences originate near contrast-enhancing regions, but

infiltrative cells in non-enhancing areas contribute to

progression. Therefore, there is a need for therapies that can

effectively target tumor cells beyond contrast-enhancing regions,

addressing both enhancing and non-enhancing compartments for

improved treatment outcomes.

Efflux transporters. Overexpression of

ATP-dependent efflux transporters, such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp)

and breast-cancer-resistance protein (BCRP), in tumor endothelial

cells reduces intracellular drug concentrations. For example,

HER2+ breast cancer brain metastases exhibit upregulated

expression of BCRP, limiting trastuzumab efficacy (9).

Signaling pathways. The Wnt and sonic

hedgehog (Shh) pathways contribute to BBB integrity and, when

dysregulated in GBM, also affect drug penetration (10). Wnt signaling promotes BBB integrity

by maintaining the expression of key vascular stability proteins

and suppressing factors that increase permeability. β-catenin

activation, a key component of Wnt signaling, helps regulate

claudin-5 and Glut1, which are essential for BBB function.

Experimental knockout of β-catenin, as well as LRP5 and LRP6, leads

to increased expression of PLVAP, a protein associated with

vascular fenestrations, resulting in abnormal BBB leakiness.

Furthermore, paracrine Wnt inhibitors such as WIF1 and DKK1,

secreted in Wnt medulloblastomas, disrupt BBB integrity, but their

experimental inhibition restores normal vascular function. These

findings highlight that active Wnt signaling is crucial for

maintaining a tightly regulated and selective BBB by preventing the

formation of fenestrations and excessive permeability.

The Shh pathway plays a critical role in maintaining

BBB integrity through both structural and immunological mechanisms

(11). Astrocytes secrete Shh,

which binds to Patched-1 and Smoothened receptors on endothelial

cells. This binding enhances the expression of tight and adherens

junction proteins, strengthening the BBB and reducing permeability.

Additionally, Shh suppresses proinflammatory responses by

inhibiting chemokine secretion, preventing leukocyte adhesion and

modulating T cell activity. Disruption of Shh signaling can lead to

BBB breakdown and heightened inflammation. Therefore, Shh is

essential for both the development and therapeutic maintenance of

BBB function.

Several strategies to enhance drug delivery by

overcoming the BBB have been proposed and some have been evaluated

in clinical trials with various degrees of success (12). Direct drug administration via

intra-tumoral, intranasal or intrathecal routes allows localized

delivery (such as carmustine and trastuzumab) but faces challenges,

including neurotoxicity and inconsistent efficacy (13,14).

Chemical modifications, such as increasing lipophilicity or

encapsulating drugs in nanoparticles (for example, liposomal

doxorubicin), improve BBB penetration and targeted delivery

(15). Inhibition of P-gp and BCRP

efflux transporters enhanced brain penetration of doxorubicin and

vemurafenib in vitro and in vivo (16,17).

Physical disruption techniques, including focused

ultrasound, laser-induced thermal therapy and osmotic disruption

(mannitol), temporarily open the BBB to facilitate drug entry

(18). Ongoing clinical trials are

evaluating ultrasound-mediated BBB disruption systems, such as

Exablate and SonoCloud-9, which use focused or implantable

ultrasound with microbubbles to transiently and noninvasively open

the BBB, enhancing the delivery of carboplatin to GBM tumor sites

(NCT04417088; NCT03744026).

Tumor-tropic neural stem cells engineered to deliver

anticancer agents show promise in clinical trials (19). Ongoing studies are evaluating

BBB-penetrating analogs of approved drugs, such as Berubicin (a

doxorubicin analog) (NCT04762069) and Buparlisib (a PI3K inhibitor)

(NCT01349660), for their potential to improve outcomes in recurrent

or refractory GBM.

While these strategies demonstrate potential in

preclinical and early clinical studies, challenges like side

effects, invasiveness and variable efficacy hinder widespread

adoption, with future research focusing on refining combination

therapies and BBB modulation techniques.

3. Resistance to chemotherapy

Since 2005, the Stupp protocol has been the standard

of treatment for GBM. It consists of radiation combined with TMZ

following surgery (20). While

this protocol has improved 2-year survival rates from 10.4 to 26.5%

compared with radiation alone, >90% of patients with GBM still

develop resistance and experience relapse (21). Uncovering the molecular drivers of

chemotherapy resistance in GBM is therefore critical for advancing

more effective therapeutic strategies. The following sections

outline key resistance mechanisms and their clinical

implications.

Upregulation of

O6-methylguanine (O6MeG)-DNA

methyltransferase. TMZ functions by inducing O6MeG

adducts that cause DNA breaks, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis,

leading to cell death (22,23).

TMZ resistance in treatment-naïve patients with GBM is mediated

predominantly by the DNA repair enzyme

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), which

removes the methyl adducts formed by TMZ, thereby preventing DNA

damage and rescuing cancer cells from death (24). In GBM, the MGMT promoter is often

methylated, silencing its expression and rendering tumors more

sensitive to TMZ. However, TMZ treatment can apply selective

pressure, potentially leading to demethylation of the MGMT

promoter, increased MGMT expression and subsequent repair of

TMZ-induced lesions, resulting in acquired resistance (25). MGMT promoter methylation status

remains one of the most robust and clinically relevant predictive

biomarkers of the response to TMZ. Several clinical trials have

explored the prognostic and therapeutic relevance of MGMT

methylation status in both newly diagnosed and recurrent GBM. The

CENTRIC (NCT00689221) and Alliance A071102 (NCT02152982) trials

investigated the addition of cilengitide and veliparib,

respectively, to standard chemoradiotherapy in MGMT-methylated GBM.

Both trials failed to demonstrate survival benefits, highlighting

the challenges of improving outcomes beyond TMZ in this subgroup

(26,27).

Conversely, trials targeting MGMT-unmethylated GBM

have focused on TMZ-sparing strategies. A Phase II trial of VAL-083

with radiotherapy showed early promise by bypassing MGMT-mediated

resistance (NCT03050736). Similarly, a study comparing etoposide

and cisplatin to TMZ (NCT05694416) aims to identify more effective

chemotherapeutic options. Immunotherapy combinations, such as

nivolumab and ipilimumab with radiation (NCT04396860), are also

under evaluation in this difficult-to-treat population.

The GENOM 009 study (NCT01102595) reaffirmed the

prognostic value of tissue-based MGMT methylation but found limited

utility in serum-based assays (28). These trials collectively underscore

the critical role of MGMT status in GBM therapy and the ongoing

pursuit of personalized treatment approaches, particularly for

patients with unmethylated tumors.

Defective DNA mismatch repair (MMR). TMZ

causes O6MeG mismatches with thymine, which are normally

recognized by the MMR system. Functional MMR triggers apoptosis in

response to such damage. Deficiencies in the MMR system, including

mutations in genes such as MSH6, MLH1 and PMS2, impair DNA repair,

contributing to resistance (29-31).

MMR-deficient GBMs may appear responsive initially but often recur

with hypermutation phenotypes and TMZ resistance (32). Hypermutation phenotype

MMR-deficient GBMs with a high tumor mutational burden (TMB) are

excellent candidates for immunotherapy (33). Immunotherapy has shown remarkable

success in MMR-deficient tumors across various cancer types,

including colorectal cancer, leading to FDA approval of the PD-1

checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab for any microsatellite

instability-high/MMR-deficient solid tumors, a landmark

tumor-agnostic approval. However, early trials, including

KEYNOTE-028 (NCT02054806) and a Phase II window-of-opportunity

study (NCT02337686), found pembrolizumab to be safe but with

limited clinical benefit in recurrent GBM, showing modest 6-month

progression-free survival (PFS) rates (~40-44%) and a median OS of

14-20 months. Additionally, pembrolizumab was studied in a

multi-cancer, Phase II trial (NCT02886585) focused on patients with

brain metastases, including those with GBM. In this setting, the

intracranial benefit rate was 42.1%, and certain patients with GBM

exhibit survival exceeding two years (34). These findings suggest that a subset

of patients with GBM may derive durable benefits from PD-1

blockade, although predictive biomarkers remain undefined, and

support further studies to identify biomarkers and mechanisms of

resistance.

Glioma stem-like cells (GSCs). GSCs are a

quiescent subpopulation within the tumor that exhibits stem-like

properties, including self-renewal and the ability to repopulate

the tumor after treatment. Nestin, a marker of neural stem cells,

is also expressed in GSCs and can serve as a biomarker to identify

this resistant population. In preclinical models,

Nestin+ GSCs were shown to persist after TMZ therapy and

regenerate proliferative tumor cells (35). Remarkably, selective ablation of

these Nestin+ cells using genetic approaches

significantly impaired tumor growth. These findings underscore the

therapeutic potential of targeting GSCs to improve GBM treatment

outcomes.

Survivin is emerging as a functionally relevant and

potential marker of GSCs, particularly in the context of

therapeutic targeting. Survivin (BIRC5) is highly expressed

in GSCs compared with non-stem GBM cells. Its inhibition

selectively reduces the viability and self-renewal capacity of GSCs

(36). Furthermore, downregulation

of Survivin sensitizes these cells to chemotherapeutic agents,

highlighting its critical role in GSC maintenance and therapy

resistance.

Building on these preclinical findings, clinical

strategies targeting Survivin have begun to show promise. The

SurVaxM vaccine trial, a Phase II clinical study, evaluated a

vaccine for the Survivin protein in combination with TMZ and

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in patients with

newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Initial results have been

encouraging, with 96% of participants progression-free at 6 months

and 93% alive at 12 months, demonstrating substantial improvement

over historical benchmarks (37).

Efflux transporters and TMZ resistance in

GBM. Efflux transporters play a pivotal role in mediating

resistance to TMZ in GBM by actively reducing intracellular drug

concentrations, thereby diminishing its therapeutic efficacy. Munoz

et al (38) demonstrated

that TMZ is a substrate for P-gp. In GBM cells with upregulated

MDR1 mRNA levels (which encodes P-gp), there is increased efflux of

TMZ, lowering its intracellular concentration and reducing its

cytotoxicity. P-gp inhibitors restored TMZ sensitivity, confirming

its role in resistance. Another study found that hypomethylation of

the ABCB1 and ABCG2 promoters led to overexpression of these

transporters, facilitating drug efflux and decreasing TMZ efficacy

in GBM cells. Epigenetic regulation was a key driver of this

phenotype (39). Elevated levels

of ABCA1, a protein traditionally associated with lipid transport,

are linked to poor clinical outcomes. Silencing ABCA1 expression

increases the sensitivity of glioma cells to TMZ, indicating its

involvement in drug efflux and resistance mechanisms (40). Mechanistically, ABCA1 contributes

to TMZ resistance by altering the TME, specifically by promoting M2

macrophage infiltration, a phenotype associated with immune

suppression and tumor progression. The p53/E2F7 axis was shown to

transcriptionally upregulate ABCA8 and ABCB4, both contributing to

reduced intracellular accumulation of TMZ and enhanced resistance

in GBM (41). Silencing E2F7

resensitized cells to TMZ.

Additional support for TMZ being a substrate of

efflux transporters such as P-gp and BCRP comes from studies

showing that genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of

these proteins, using agents like elacridar (GF120918),

significantly enhanced brain penetration by 1.5-fold, and antitumor

efficacy of TMZ in mice with orthotopic or intracranial GBM tumors.

Similarly, Reversan, another efflux transporter inhibitor, also

markedly enhanced TMZ activity in patient-derived primary and

recurrent GBM models (42). These

observations suggest that inhibiting efflux transporters to enhance

intracellular TMZ levels may re-sensitize GBM cells to TMZ.

However, despite promising preclinical data, this approach has not

yet translated to clinical success, likely due to the complexity of

resistance mechanisms and safety concerns at effective doses.

Nonetheless, it remains an active area of research with potential

for identifying a clinically viable efflux transporter

inhibitor.

Hypoxia. Hypoxia, a defining feature of

aggressive gliomas such as GBM, arises when rapidly growing tumors

outpace their blood supply (43).

This oxygen-deficient microenvironment stabilizes hypoxia-inducible

transcription factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α, which orchestrate a broad

transcriptional program that enhances tumor cell survival,

therapeutic resistance and disease progression. Key downstream

targets of these factors include MGMT, which contributes to TMZ

resistance by reducing intracellular TMZ levels (44).

HIF-2α promotes the expression of GSC signature

genes, supporting the maintenance and expansion of this inherently

TMZ-resistant subpopulation (45).

Moreover, hypoxia induces SHOX2 expression, a gene associated with

TMZ resistance, particularly in MGMT-unmethylated gliomas and

TMZ-resistant cell lines (46).

Hypoxia also modulates the apoptotic machinery to

support resistance. For example, HIF-1α upregulates miR-26a under

hypoxic conditions, which in turn suppresses pro-apoptotic proteins

Bad and Bax, thereby inhibiting mitochondrial apoptosis and

contributing to TMZ resistance (47).

Collectively, these interconnected hypoxia-driven

mechanisms underscore the pivotal role of hypoxia in driving

therapeutic resistance in GBM. In response, several clinical trials

have been launched to explore therapeutic strategies that either

inhibit or leverage hypoxia in GBM. These approaches include

hypoxia-activated prodrugs, oxygen therapeutics and inhibitors

targeting HIF proteins, to enhance tumor sensitivity to

conventional treatments or disrupt hypoxia-mediated survival

pathways.

One notable trial, NCT01403610, evaluated

evofosfamide (TH-302), a hypoxia-activated prodrug, in combination

with BEV in patients with recurrent GBM who had failed prior BEV

treatment (48). PFS at 4 months

was 31%, which was a statistically significant improvement over the

historical rate of 3%, although the clinical significance of this

may be limited. Another trial, NCT03216499, investigated PT2385, a

selective HIF-2α inhibitor, in patients with first recurrent GBM

(49). While no radiographic

responses were observed, patients with higher systemic drug

exposure showed improved PFS, suggesting potential pharmacodynamic

relevance.

Addressing tumor oxygenation directly, NCT02189109

explored NVX-108, an oxygen therapeutic designed to improve tumor

oxygen levels and enhance the effects of radiotherapy and

chemotherapy in newly diagnosed GBM (50). Preliminary results demonstrated

effective tumor reoxygenation without affecting normal brain

tissue, with indications of improved survival outcomes. These

findings support further exploration of oxygenation strategies in

GBM therapy.

Several early-phase trials focused on inhibiting

HIF-1α, a central regulator of hypoxic adaptation. These

include EZN-2208 (NCT01251926), EZN-2698 (NCT01120288), PX-478

(NCT00522652), OKN-007 (NCT01672463) and Icaritin (NCT02496949).

These agents employ a range of mechanisms, from downregulating

HIF-1α mRNA to promoting its degradation, and were primarily

studied for safety and pharmacodynamic effects, with limited

efficacy data reported (51).

In conclusion, while targeting hypoxia in GBM

presents a compelling therapeutic avenue, clinical trials to date

have yielded mixed results, with most agents demonstrating safety

but limited efficacy in monotherapy settings. However, these

studies highlight the potential for hypoxia-directed therapies to

complement existing treatments. Ongoing research focusing on

patient stratification, drug combinations, and biomarkers of

hypoxic response will be key to unlocking the full therapeutic

potential of these strategies in GBM.

Dysregulated intracellular signaling

pathways. While DNA repair mechanisms, such as MGMT

upregulation and defective MMR, are well-established contributors

to TMZ resistance, dysregulated intracellular signaling pathways,

especially the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, play an equally critical

role in mediating resistance in GBM.

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR

signaling pathway plays a central role in GBM resistance to TMZ. It

is frequently dysregulated in GBM, in up to 88% of tumors,

primarily due to upstream receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)

alterations such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

amplification, activating mutations of PI3CA (p110) or PIK3R1

(P85), or loss of PTEN expression (52).

One mechanism through which PI3K/Akt/mTOR confers

TMZ resistance is metabolic reprogramming, known as the Warburg

effect. Akt upregulates PDK1, which inhibits pyruvate

dehydrogenase, suppressing oxidative phosphorylation and promoting

glycolysis (53). This metabolic

shift supports tumor cell survival under hypoxic conditions and

contributes to resistance. Dichloroacetate, a PDK1 inhibitor, can

reverse this effect, particularly in EGFRvIII-positive GBMs,

restoring TMZ sensitivity (54).

Another key resistance mechanism involves the

response to hypoxia and the promotion of angiogenesis. Akt

stabilizes HIF-1α, which enhances the transcription of VEGF and

other hypoxia-response genes, driving angiogenesis and increasing

tumor survival in hypoxic microenvironments (55). HIF-1 also induces the expression of

CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4, promoting tumor cell proliferation

and invasiveness (56).

Additionally, NF-κB is activated via Akt-mediated

degradation of its inhibitor, IkB. This activation leads to

increased transcription of pro-survival genes and has been strongly

linked to both poor prognosis and TMZ resistance (57).

The PI3K/Akt pathway further promotes resistance by

inhibiting apoptosis. It modulates the upregulation of

anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and Mcl-1, which inhibit

apoptotic processes and contribute to chemoresistance. For example,

studies have shown that the inhibition of PI3K and Bcl-2 can

sensitize glioblastoma cells to apoptosis by downregulating Mcl-1

and phospho-BAD, highlighting the role of these proteins in therapy

resistance (58). Moreover, the

PI3K/Akt pathway influences the overexpression of other

anti-apoptotic factors such as MDM2, a negative regulator of the

tumor suppressor p53, thereby further inhibiting apoptotic pathways

(59,60). Akt also increases the expression of

survivin, an inhibitor of apoptosis, which blocks TMZ-induced cell

death. Inhibition of survivin has been shown to increase TMZ

sensitivity in GBM cells (61).

Furthermore, the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR

pathway in general, and mTOR in particular, positively regulates

autophagy in response to TMZ-induced DNA damage, leading to tumor

cell survival under therapeutic stress (62). Moreover, the CaMKKβ/AMPKα/mTOR

signaling axis has been linked to the upregulation of TRPC5, a

protein that triggers autophagy and contributes to TMZ resistance.

Targeting mTOR-mediated TRPC5 expression is thus emerging as

another potential strategy to sensitize GBM cells to TMZ and

overcome therapeutic resistance (63).

In summary, the PI3K/Akt pathway orchestrates

multiple survival strategies in GBM, altering metabolism,

suppressing apoptosis, enhancing angiogenesis and modulating

transcription factors, all of which collectively foster resistance

to TMZ. In recent years, multiple clinical trials have evaluated

pharmacological inhibitors targeting this pathway as a strategy to

overcome TMZ resistance, with mixed results.

One of the more advanced clinical efforts involved

GDC-0084 (Paxalisib), a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor evaluated in a

Phase IIa trial (NCT03522298) in patients with newly diagnosed GBM

with unmethylated MGMT promoter status, an indicator of poor TMZ

response. Administered post-chemoradiation, GDC-0084 showed

manageable toxicity and modest clinical activity, though its

definitive efficacy remains to be confirmed in larger, controlled

studies (64).

Combination approaches have also been tested. A

Phase I study of temsirolimus (a mTOR inhibitor) with perifosine

(an AKT inhibitor) in recurrent malignant gliomas reported

acceptable safety but limited efficacy (NCT01051557), with disease

stabilization rather than regression being the most common outcome.

Similarly, the dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor voxtalisib (XL765) was

combined with TMZ (± radiotherapy) in early-phase studies

(NCT00704080) (65). Although

biologically active, these agents were generally associated with

tolerable side effects but only modest improvements in

progression-free survival.

Other compounds, such as NVP-BEZ235, sapanisertib

(TAK-228) and CC-115 have shown encouraging preclinical efficacy,

particularly in inducing apoptosis and sensitizing GBM cells to TMZ

(66). However, their clinical

development in GBM has been limited by toxicity, lack of clear

efficacy signals, or logistical challenges in crossing the BBB

(NCT02133183).

In summary, while targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway remains a rational and biologically validated strategy to

circumvent TMZ resistance in GBM, clinical translation has thus far

yielded limited success. Future approaches may require improved

patient stratification, rational drug combinations and more

effective brain-penetrant inhibitors to fully exploit this pathway

therapeutically.

MAPK pathway. The MAPK signaling pathway

plays a central role in mediating resistance to TMZ in GBM,

operating through multiple mechanisms. Among these, the JNK isoform

MAPK8 is upregulated in TMZ-resistant GBM cells (67). This activation suppresses

apoptosis, thereby allowing tumor cells to evade drug-induced

death. Inhibition of MAPK8 restores TMZ sensitivity and increases

apoptotic activity, positioning it as a promising therapeutic

target to overcome resistance.

The ERK arm of the MAPK pathway is activated by

TMZ-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS). Upon activation, it

induces autophagy, which serves as a cytoprotective mechanism that

helps glioma cells survive the cytotoxic effects of TMZ (68). However, this pathway can be

disrupted by resveratrol, which inhibits ROS production and ERK

activation, leading to decreased autophagy and increased

apoptosis.

Another critical arm of the MAPK cascade is the p38

MAPK pathway, which enhances TMZ resistance through the

upregulation of Nrf2, a key regulator of antioxidant responses

(69). By promoting detoxification

and neutralization of ROS, Nrf2 enables glioma cells to survive the

oxidative stress induced by TMZ. Targeting the p38-Nrf2 axis offers

a potential approach to weaken this protective mechanism and

resensitize tumors to treatment.

Beyond its individual components, the MAPK pathway

functions as a convergent hub, integrating upstream signals from

RTKs [(such as EGFR and mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET)] to

drive proliferation, suppress apoptosis and stabilize resistant

phenotypes. This convergence underscores the resilience of MAPK

signaling in maintaining cell survival under therapeutic pressure.

Furthermore, MAPK is tightly interconnected with other resistance

networks, including DNA repair pathways, autophagy and metabolic

reprogramming, and supports the persistence of GSCs, a

subpopulation that is crucially involved in failure of therapy and

in recurrence.

In addition to these intrinsic mechanisms, adaptive

resistance to TMZ also involves the MAPK pathway, particularly

through feedback activation of ERK and p38(70). p38 MAPK activation is associated

with a mesenchymal-like phenotypic shift in GBM cells,

characterized by enhanced migratory capacity, immune evasion and

resistance to apoptosis. This mesenchymal transition is a hallmark

of aggressive, therapy-resistant tumors. By promoting both stress

adaptation and phenotypic plasticity, the p38 MAPK pathway emerges

as a key enabler of TMZ resistance and tumor progression,

suggesting that targeting this pathway could help counteract

adaptive resistance mechanisms in GBM.

Taken together, these findings illustrate that the

MAPK pathway contributes at multiple levels, including apoptosis

evasion, redox balance, stem cell maintenance and adaptive

plasticity, making it a compelling target for combinatorial

strategies aimed at overcoming TMZ resistance in glioma and

GBM.

Several clinical trials have explored MAPK pathway

inhibitors as a strategy to overcome GBM resistance to TMZ, with

varying degrees of success. One of the early efforts was a Phase II

trial of TLN-4601 (NCT00730262), a Ras-MAPK pathway inhibitor,

tested as monotherapy in recurrent GBM. Unfortunately, the trial

reported no PFS at 6 months and a median overall survival (OS) of

just 130 days, indicating limited efficacy.

Sorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor targeting RAF,

was evaluated in multiple trials. In NCT00597493, sorafenib was

combined with TMZ in patients with recurrent GBM, yielding a median

PFS of 6.4 weeks and an OS of 41.5 weeks (71). Another trial, NCT00544817, tested

sorafenib with the standard Stupp protocol in an adjuvant setting,

showing a PFS of 6 months and an OS of 12 months (72). These studies suggested only modest

benefits.

More recent studies have focused on targeting

specific mutations in the MAPK pathway. The combination of

dabrafenib and trametinib, BRAF and MAPK inhibitors respectively,

is under investigation in NCT03919071, a Phase II study involving

patients with BRAF V600E-mutated HGGs, including GBM. Similarly,

NCT03973918 is assessing the efficacy of binimetinib and

encorafenib, another MEK and BRAF inhibitor pair, in BRAF

V600-mutated gliomas. Both trials are ongoing and aim to exploit

genetic vulnerabilities in the MAPK pathway.

LY2228820, a p38 MAPK inhibitor, was studied in

NCT02364206, a Phase II trial combined with the Stupp protocol. The

trial has been completed, but the results remain unpublished. This

agent represents an alternative mechanism of MAPK inhibition,

targeting stress-related kinases involved in TMZ resistance.

Finally, pazopanib, a broad-spectrum multikinase

inhibitor, is being tested in combination with TMZ in the ongoing

Pazoglio trial (NCT02331498). This Phase I/II study is currently

enrolling and aims to determine whether pazopanib can enhance the

effectiveness of standard TMZ therapy in patients with newly

diagnosed GBM.

Collectively, these studies highlight both the

challenges and evolving strategies in targeting the MAPK pathway to

combat TMZ resistance in GBM, with an increasing emphasis on

genetically defined patient subgroups.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Dysregulated Wnt

signaling, particularly through the canonical (β-catenin-dependent)

pathway, plays a central role in GBM resistance to TMZ and other

chemotherapies (73).

One of the key mechanisms involves the promotion of

GSC characteristics and maintenance of stemness (74). Wnt ligands such as Wnt3a are highly

expressed in GBM and drive this stem-like phenotype, which is

closely linked to therapeutic resistance. Activation of the

canonical pathway is marked by nuclear accumulation of β-catenin,

often facilitated by proteins like FoxO3a, and this nuclear

translocation is associated with increased resistance to TMZ

(75).

Wnt/β-catenin signaling also promotes

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), enhancing tumor cell

motility, invasiveness and plasticity, all of which contribute to

chemoresistance (76). Endothelial

cells within the TME can transdifferentiate into mesenchymal-like

cells via a c-Met-mediated axis that activates β-catenin, leading

to the expression of multidrug resistance-associated proteins and

further promoting TMZ resistance. This microenvironment-driven cell

plasticity adds another layer of complexity to therapy resistance

in GBM.

Another important mechanism is the positive

regulation of MGMT by Wnt signaling. (77). The pharmacological inhibition of

Wnt signaling using agents such as salinomycin, celecoxib and

Wnt-C59 has been shown to reduce MGMT expression and restore TMZ

sensitivity in resistant GBM cells. Furthermore, TMZ itself can

activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling through a

PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β-dependent cascade that operates independently of

the ATM/Chk2 DNA damage response pathway, suggesting that Wnt

pathway activation is a downstream effect of TMZ exposure,

potentially fueling resistance (78).

In addition, FERMT3 (also known as kindlin-3), an

integrin-activating adaptor protein, has been implicated in GBM

chemoresistance through its role in promoting integrin-mediated

activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (79). Knockdown of FERMT3 results in

decreased β1-integrin activity, reducing Wnt pathway activation and

sensitizing GBM cells to TMZ.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) also play a critical role

in modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling and influencing

chemoresistance in GBM. For example, downregulation of miR-126-3p

and miR-129-5p in TMZ-resistant GBM cells leads to constitutive Wnt

activity and enhanced tumor proliferation and resistance, while

their overexpression inhibits Wnt signaling and restores

chemosensitivity (80,81). By contrast, miR-21 is upregulated

in resistant GBM, promoting Wnt pathway activation and tumor

survival (82).

A regulatory circuit involving miR-125b/miR-20b

sustains Wnt activity in proneural GSCs by suppressing its negative

regulators, further contributing to tumor growth (83). Additionally, IGF-1 has been shown

to upregulate miR-513a-5p via PI3K signaling, which suppresses

NEDD4L, an inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, thereby enhancing

GBM progression and TMZ resistance (84). These findings underscore the

complex, multilayered regulation of Wnt signaling by ncRNAs and

highlight additional potential therapeutic targets for overcoming

chemoresistance in GBM.

Collectively, these findings highlight the

multifaceted role of aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling in sustaining

GSCs, promoting EMT and invasive behavior, modulating MGMT and

other drug metabolism genes, and enabling microenvironmental

plasticity, all of which converge to promote TMZ resistance in GBM.

Targeting this pathway, therefore, offers a promising strategy to

overcome therapeutic resistance.

Currently, there are no clinical trials specifically

investigating the inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in

patients with GBM. However, several Wnt pathway inhibitors,

originally developed and tested for other types of cancer, have

shown promise in preclinical models of GBM. These include LGK974

(WNT974), which has been shown to significantly reduce GBM cell

proliferation and stemness markers in vitro (85); XAV939, a tankyrase inhibitor that

enhances GBM cell radiosensitivity by promoting β-catenin

degradation (86); SEN461, which reduces glioma cell

viability and tumor volume in xenografts (87) and E7386, which is in Phase Ib/II

trials for other solid tumors and appears to eliminate

drug-resistant cancer stem cells in preclinical GBM models

(88).

Despite these encouraging results, translating Wnt

pathway inhibition into effective GBM therapies poses significant

challenges. BBB limits the ability of several systemic drugs,

including Wnt inhibitors, to reach therapeutic concentrations in

the brain. Additionally, the toxicity of Wnt pathway inhibition,

due to its essential role in tissue homeostasis, can lead to

undesirable side effects such as bone fragility. Another important

consideration is the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in adult

neurogenesis, raising concerns that pathway inhibition might impact

cognitive function or neuronal repair.

In conclusion, while no clinical trials have yet

targeted the Wnt/β-catenin pathway specifically in GBM, the pathway

remains an attractive target based on compelling preclinical

evidence. Continued efforts to develop brain-penetrant inhibitors

with favorable safety profiles are essential. Addressing the

challenges of BBB permeability and limiting systemic toxicity is

critical for the eventual success of Wnt-targeted therapies in the

treatment of GBM.

Hippo pathway. Dysregulation of the Hippo

pathway leads to overexpression of its key effectors, YAP and TAZ.

These proteins activate downstream target genes that promote cell

survival, proliferation, glioma growth and malignancy. Elevated

levels of TAZ and YAP are associated with poor outcomes in gliomas

(89). TAZ (both protein and mRNA)

is highly expressed in GBM and correlates with reduced survival.

Similarly, high YAP expression is observed across glioma grades and

predicts shorter survival (90).

Importantly, TAZ knockdown impairs tumor formation in mouse models,

underscoring its functional role in glioma pathogenesis.

The Hippo pathway also contributes to multidrug

resistance in GBM through dysregulated YAP/TAZ activity.

Overexpression of TAZ reduces TMZ cytotoxicity by upregulating the

anti-apoptotic protein MCL-1, thereby making glioma cells resistant

to apoptosis (91). In addition,

the YAP-TAZ-TEAD complex promotes TMZ resistance by inducing Hippo

target genes such as CTGF and Cyr61 through TGF-β1-mediated

Smad/ERK signaling (92). CD109,

another regulatory protein, further contributes to chemoresistance

by activating IL-6/STAT3 signaling and enhancing GSC stemness.

CD109 also stimulates the Hippo pathway; its loss leads to reduced

nuclear YAP, decreased STAT3 activity, diminished GSC stemness and

impaired tumorigenicity, highlighting its role in both chemo- and

radio-resistance (93). Finally,

the Hippo pathway interacts with other signaling networks such as

mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin and Notch, further reinforcing therapy

resistance in GBM (92).

As of April 2025, there are no clinical trials

specifically investigating Hippo pathway inhibitors for overcoming

GBM resistance to TMZ. However, considering the role of the Hippo

pathway in glioma tumor progression, chemoresistance and

immunosuppression in GBM, the targeting of the YAP/TAZ

transcriptional axis could be a potential therapeutic strategy.

Previous research has led to the identification of

small-molecule inhibitors aimed at disrupting YAP/TAZ-TEAD

interactions. Verteporfin, initially used in photodynamic therapy,

has demonstrated the ability to inhibit YAP/TAZ-TEAD binding,

induce apoptosis and suppress oncogenic gene expression in

EGFR-amplified/mutant GBM models (94). Clinical data from a Phase 0 trial

showed effective intra-tumoral delivery of liposomal Verteporfin

and reduced YAP/TAZ nuclear localization (NCT04590664) (95).

Other inhibitors under development and primarily

tested in other cancer models include GNE-7883, an allosteric

pan-TEAD inhibitor and ETS-003, a potent compound that blocks

YAP/TAZ-TEAD binding and downstream gene expression (96,97).

IAG933, currently in Phase I clinical trials, shows broad

inhibition across TEAD paralogs and is being assessed for antitumor

activity in solid tumors, including GBM (NCT04857372) (98).

Collectively, these agents represent a new class of

potential therapies designed to overcome YAP/TAZ-mediated

resistance mechanisms and enhance the effectiveness of standard

treatments such as TMZ. Ongoing research and clinical validation

will determine their translational potential in glioma therapy.

Exosomal ncRNAs and TMZ resistance in

glioblastoma. Exosomal ncRNAs [ncRNAs, including miRNAs, long

non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs)], are

increasingly being recognized as central mediators of

chemoresistance in GBM (99).

Encapsulated within exosomes and secreted into the TME, these

ncRNAs enable intercellular communication and orchestrate a range

of molecular processes that influence tumor progression, therapy

resistance and recurrence.

miRNAs as regulators of resistance and

sensitivity. miRNAs are small regulatory RNAs that control gene

expression post-transcriptionally and play crucial roles in

apoptosis, drug efflux, DNA repair and oncogenic signaling

pathways. Dysregulation of miRNAs in GBM contributes substantially

to TMZ resistance.

miR-21, one of the most prominent oncomiRs in GBM,

is upregulated in response to TMZ. It promotes resistance by

targeting tumor suppressors such as PTEN, PDCD4 and

RECK, thereby enhancing cell survival and impairing

apoptosis (100).

miR-328 is frequently downregulated in TMZ-resistant

cells and it targets ABCG2, a drug efflux transporter. Its

suppression leads to increased efflux of TMZ, reducing

intracellular drug accumulation and therapeutic efficacy (99).

miR-29c modulates TMZ sensitivity by targeting DNA

methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B, indirectly downregulating

MGMT, a DNA repair enzyme that confers TMZ resistance. In

GBM, miR-29c is often downregulated, contributing to elevated MGMT

levels and reduced TMZ efficacy (101).

Interestingly, certain miRNAs enhance

chemosensitivity to agents beyond TMZ. Members of the

miR-302-3p/372-3p/373-3p/520-3p family increase susceptibility to

tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sunitinib and axitinib by

downregulating the PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling pathways (102).

lncRNAs as multifaceted mediators of

resistance. lncRNAs contribute to drug resistance through a

range of mechanisms, including transcriptional regulation,

chromatin remodeling, miRNA sponging and modulation of signaling

cascades. H19, SBF2-AS1, MALAT1 and ADAMTS9-AS2 are overexpressed

in GBM and associated with TMZ resistance. These lncRNAs promote

EMT, enhance DNA repair and inhibit apoptotic signaling (99).

Specifically, H19 activates Wnt/β-catenin

signaling to maintain stemness and promote EMT (103) and SBF2-AS1 sponges miR-151a-3p,

leading to upregulation of XRCC4, a DNA repair factor (104). MALAT1 promotes TMZ

resistance in glioma through multiple mechanisms. Li et al

(105) demonstrated that

transfection of MALAT1 upregulates EMT and multidrug resistance

genes, such as ZEB1 and MDR1, respectively, both in vitro

and in vivo, collectively reducing glioma cell sensitivity

to TMZ. In addition, other studies have shown that MALAT1 promotes

chemoresistance and cell proliferation by suppressing miR-203,

which targets thymidylate synthase, and by sponging miR-101,

thereby blocking its inhibition of autophagy in glioma cells

(106). ADAMTS9-AS2 promotes TMZ

resistance by upregulating the FUS/MDM2 ubiquitination axis,

specifically by enhancing FUS expression, which increases

MDM2-mediated ubiquitination processes and leads to decreased

apoptosis and increased survival of GBM cells under TMZ treatment

(107).

By contrast, tumor-suppressive lncRNAs, such as

CASC2, can augment the sensitivity of malignant cells to TMZ by

enhancing its ability to suppress cell proliferation through the

regulation of miR-181a, which, in turn, upregulates PTEN expression

and downregulates phosphorylated AKT levels (108).

circRNAs as stable sponges shaping

resistance. circRNAs are covalently closed RNA loops with high

stability that function predominantly by sponging miRNAs or

modulating protein interactions. They are emerging as key

regulators of drug resistance in GBM.

circNFIX is overexpressed in glioma and promotes

tumor growth and resistance to TMZ by sponging miR-34a-5p, which

normally suppresses NOTCH1, thereby activating the Notch signaling

pathway. Downregulation of circNFIX or overexpression of miR-34a-5p

reduced glioma cell proliferation, migration and survival both

in vitro and in vivo, highlighting the role of

circ-NFIX in glioma progression (109). Additionally, exosomal circ-NFIX

can transfer TMZ resistance from resistant glioma cells to

sensitive glioma cells by promoting migration and invasion while

inhibiting apoptosis, and suppression of circ-NFIX restores TMZ

sensitivity by upregulating miR-132(110).

circHIPK3 is upregulated in TMZ-resistant glioma and

promotes tumor progression, metastasis and drug resistance by

acting as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) for miRNAs. For

example, circHIPK3 sponges miR-421 to upregulate the oncogene ZIC5,

whose expression drives glioma cell proliferation, migration and

drug resistance; circHIPK3 knockdown reduces ZIC5 levels, inhibits

tumor growth and enhances TMZ sensitivity (111). In a parallel pathway, circHIPK3

sponges miR-524-5p to increase KIF2A expression, thereby activating

the oncogenic PI3K/AKT pathway and contributing to proliferation,

metastasis and resistance to TMZ (112).

circ_0043949 is overexpressed in TMZ-resistant GBM

cells and exosomes, where it contributes to chemoresistance by

functioning as a ceRNA. It sponges multiple miRNAs, including

miR-876-3p, miR-7161-3p and miR-6783-3p, thereby upregulating

targets like integrin α1 (ITGA1) and suppressing miR-140-mediated

inhibition of EMT (113). These

actions collectively enhance the proliferation, invasion and

survival of GBM cells, and exosomal circ_0043949 can transfer

resistance traits to other cells, as shown in xenograft models.

Among the additional circRNAs upregulated in

recurrent GBM tissues and TMZ-resistant cell lines are circASAP1

and circ_0000936. circASAP1 confers resistance by sponging

miR-502-5p, which leads to NRAS upregulation and activation of the

NRAS/MEK1/ERK1/2 signaling pathway (114). Of note, its depletion restores

TMZ sensitivity in resistant xenograft models. Likewise,

circ_0000936 promotes resistance by suppressing miR-1294, and its

downregulation sensitizes glioma cells to TMZ (115). These findings underscore both

circRNAs as potential therapeutic targets for overcoming TMZ

resistance in GBM.

Exosomal ncRNAs play pivotal roles in mediating

chemoresistance in GBM by regulating apoptosis, drug efflux, DNA

repair and key signaling pathways. Their dual function as

biomarkers and active effectors makes them compelling targets for

therapeutic intervention. Strategies aimed at inhibiting oncogenic

ncRNAs or restoring tumor-suppressive ones, either directly or by

blocking their exosomal transfer, offer promising avenues to

overcome TMZ resistance and improve patient outcomes.

Currently, no clinical trials specifically target

exosomal ncRNAs to counteract TMZ resistance in GBM. However,

preclinical studies, including those aforementioned, have

identified several exosomal ncRNAs involved in resistance

mechanisms, highlighting potential targets for future therapies.

One notable study employed CRISPR-Cas9 screening to identify

resistance-associated genes in the mesenchymal subtype of GBM. It

then used an exosome-based system to co-deliver siRNAs targeting

genes such as RASGRP1 and VPS28, the small-molecule

inhibitor EPIC-0412 and TMZ (116). This combination significantly

reduced tumor burden in vivo, though further validation is

needed for clinical translation. Future clinical efforts should

focus on developing exosome-based delivery systems for targeted

therapy, using circulating exosomal ncRNAs as biomarkers to predict

TMZ resistance, and combining exosomal ncRNA-targeted strategies

with standard treatments to overcome resistance

3. Resistance to radiotherapy

Radiotherapy for GBM has seen significant

technological advancements, evolving from 2D whole-brain

radiotherapy to 3D conformal radiotherapy, intensity-modulated

radiation therapy and volumetric arc therapy (117,118). These modern techniques offer

improved targeting and reduced damage to healthy tissues.

Stereotactic and hypofractionated approaches have also been

introduced, offering more precise delivery and shorter treatment

durations, respectively (119).

Despite these improvements, clinical outcomes remain poor due to

intrinsic and acquired resistance to radiation in patients with

GBM, especially in recurrent cases. Overall, technological progress

in radiotherapy has not translated into substantial survival

benefits for patients with GBM.

The Stupp protocol, which consists of maximal safe

surgical resection followed by concurrent radiation therapy and TMZ

chemotherapy, and subsequently adjuvant TMZ, represents a

multimodal treatment approach. This complexity makes it challenging

to isolate the specific contribution of radiation resistance in

clinical settings. Nonetheless, radiotherapy resistance in GBM is

broadly attributed to three key factors: Hypoxic niches,

dysregulated DNA damage response (DDR) and GSCs, each of which has

been extensively discussed in earlier sections.

A recent study using patient-derived xenograft (PDX)

models of GBM have further substantiated these resistance

mechanisms. A notable finding is the existence of

radiation-tolerant persister (RTP) cells, a subpopulation that

survives radiotherapy through enhanced DNA repair capabilities and

sustained GSC-like properties (120). These RTP cells exhibit elevated

activity in both homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous

end joining pathways, rendering them highly resilient to

radiation-induced DNA breaks. Mechanistically, constitutive

activation of NF-κB signaling in RTP cells leads to increased

expression of the transcription factor YY1, which suppresses

miR-103a. This suppression, in turn, upregulates FGF2 and XRCC3,

promoting DNA repair and maintenance of stemness. Of note,

restoring miR-103a levels using transferrin-functionalized

nanoparticles has been shown to significantly enhance

radiosensitivity in PDX models, offering a promising therapeutic

strategy to overcome radio-resistance and prevent recurrence.

Fang et al (121) have demonstrated that

DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) plays a critical role in

maintaining GSC properties by stabilizing the transcription factor

SOX2, a key regulator of stemness and therapeutic resistance in

GBM. Specifically, DNA-PK phosphorylates SOX2 at serine 251,

preventing its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, thereby

sustaining its function. Pharmacological inhibition of DNA-PK using

NU7441 destabilizes SOX2, promotes GSC differentiation, enhances

radiosensitivity and leads to tumor regression and improved

survival in glioblastoma-bearing mice. These findings position

DNA-PK as a compelling therapeutic target for overcoming

radio-resistance in GBM.

In parallel, other studies have shown that repeated

radiation exposure induces metabolic and transcriptional

adaptations, including mitochondrial biogenesis and enhanced

oxidative stress tolerance. Quiescent CD133+ GSCs may be

reactivated following radiation, upregulating key self-renewal

genes such as BMI1 and SOX2, which contribute to tumor repopulation

(122). Additionally, radiation

promotes IGF1 secretion, which induces N-cadherin-mediated

cell-cell adhesion, enhancing GSC survival by suppressing

differentiation and protecting against apoptosis via Clusterin

secretion. A previous study showed that this IGF1-N-cadherin axis

drives the development of a radioresistant GSC phenotype marked by

reduced proliferation, increased stemness and membrane-localized

β-catenin accumulation, which suppresses Wnt signaling and

differentiation (123).

Crucially, this adaptive resistance can be reversed by

CRISPR-mediated knockout of N-cadherin or pharmacologic IGF1R

inhibition with picropodophyllin, underscoring its therapeutic

relevance.

A particularly comprehensive investigation created

radiation-selected (RTS) PDX models by serially irradiating

treatment-naïve GBMs (124).

These RTS models closely mimic clinical recurrence and revealed

significant alterations in gene expression and kinase activity.

Interestingly, specific lncRNAs were identified as regulators of

DNA repair and other resistance-associated pathways. Kinomic

profiling of RTS tumors uncovered elevated activity of several

kinases, including JAK, fibroblast growth factor receptor and

Ephrin kinases. Fortunately, small-molecule inhibitors targeting

these kinases were able to re-sensitize RTS tumors to radiation in

preclinical settings (124).

Collectively, these findings illustrate that GBM

resistance to radiation is a multifactorial and adaptive process,

involving intricate crosstalk between DNA repair, stemness,

metabolism, signaling and tumor microenvironmental cues. Targeting

these mechanisms, especially those unique to resistant

subpopulations, may offer novel therapeutic opportunities to

enhance the efficacy of radiation therapy in GBM.

In this context, radiosensitizers have emerged as a

promising strategy to improve the effectiveness of radiotherapy

without increasing radiation doses, thus reducing collateral damage

to healthy tissues. Radiosensitizers function by interfering with

cellular mechanisms that normally protect tumor cells from

radiation-induced damage. These mechanisms include inhibition of

DNA repair enzymes [such as poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP), ATM

and ATR] (125), disruption of

redox homeostasis via thiol depletion or pro-oxidant activity,

suppression of stemness pathways and mimicking the electrophilic

activity of oxygen to overcome hypoxia-associated resistance.

Several chemotherapeutic agents and targeted inhibitors have

demonstrated radio-sensitizing effects in preclinical GBM models

and early clinical studies including: i) Gemcitabine, which

disrupts DNA replication by incorporating into the DNA strand

(126); Talazoparib and veliparib

(PARP inhibitors) that impair single-strand break repair (127); iii) Gefitinib (an EGFR inhibitor)

that enhances radiation-induced cytotoxicity (128); iv) histone deacetylase inhibitors

(quisinostat, valproate and vorinostat) to affect chromatin

remodeling and DNA repair (129,130); v) Chloroquine (an autophagy

inhibitor), to enhance radiation-induced apoptosis (131); vi) Adavosertib (a WEE1 inhibitor)

that disrupts cell cycle checkpoints (125); and vii) Papaverine (a

mitochondrial complex I inhibitor) to improve tumor oxygenation and

radiosensitivity in hypoxic tumors (132).

Despite promising preclinical data, translation to

clinical success has been limited. Several radiosensitizers have

progressed to Phase I/II clinical trials, including ascorbate,

sulfasalazine, trans-sodium crocetinate, NVX-108 and others;

however, most have failed to show significant improvements in

progression-free or OS in patients with GBM (133).

Among radiosensitizer classes, oxygen mimetics and

metabolic modulators hold special promise for alleviating tumor

hypoxia, a known driver of radio-resistance. Compounds containing

nitro groups, hydrogen peroxide and mitochondrial inhibitors, such

as papaverine have shown potential in preclinical models but face

challenges in effective tumor delivery due to poor vascularization

(132).

Thus, while radiosensitizers remain a viable

therapeutic adjunct, there is an urgent need to identify biomarkers

predicting radiosensitizer response, improve drug delivery to

hypoxic tumor regions, develop combinatorial strategies targeting

both DNA repair and tumor metabolism, and validate novel agents in

robust GBM models, including PDX and radiation-selected

systems.

By addressing these challenges, radiosensitizers may

fulfill their therapeutic potential as key enhancers of

radiotherapy outcomes in glioblastoma.

4. Resistance to targeted therapy

Glioblastomas are classified based on genetic

features rather than just histology. GBMs are categorized into

three subgroups based on differential gene expression: Proneural,

classical and mesenchymal, each of which is driven by distinct

molecular alterations (134).

There has been increasing interest in developing targeted drugs to

address genomic abnormalities specific to subtypes, such as EGFR

amplification in the classical subtype, NF-κB hyperactivation in

the mesenchymal subtype and PDGFR mutation in the proneural

subtype.

Glioma cell lines and primary GBM tissues exhibit

upregulated expression of PDGF and PDGFRs, particularly in the

proneural subtype, characterized by a high rate (35%) of focal

PDGFRA amplification. PDGFRβ expression is specific to GBM

endothelial cells, being absent in normal brain vessels,

highlighting its potential for GBM-specific targeted therapy

(135).

Several anti-PDGFR agents, including olaratumab (an

anti-PDGFRα antibody with significant tumor growth inhibition

activity in xenograft models, but minimal clinical efficacy),

CP-673,451 (a small molecule targeting PDGFRα and PDGFRβ to induce

terminal differentiation of GBM cells) (136), crenolanib (CP-868,596, exhibiting

brain penetration and in vivo PDGFR phosphorylation

inhibition) (137), and

avapritinib and ripretinib (targeting PDGFRα mutations, with

avapritinib showing improved CNS penetrance) (138), have demonstrated promise in

preclinical GBM models, but their clinical efficacy remains

uncertain, with varying degrees of success and limitations observed

in patient trials.

BEV, a monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF isoforms,

has been extensively studied in regard to GBM. After promising

results from Phase II trials, the FDA approved BEV in 2009 for

recurrent GBM. In the BRAIN trial, BEV achieved a 6-month PFS rate

of 42% as a single agent and 50% when combined with irinotecan,

though OS was similar between groups. Despite exceeding benchmarks,

trials for BEV in combination therapies for primary GBM have shown

disappointing results, partly due to pseudo-responses that mimic

tumor shrinkage on imaging without true clinical benefit (139,140).

EGFR amplification is prevalent in 57% of primary

GBM cases, predominantly in the classical subtype and may involve

extracellular mutations, constitutively active EGFRvIII or

extrachromosomal DNA, which exacerbates intra-tumoral heterogeneity

and complicates drug targeting (141,142).

Although anti-EGFR therapies (such as dacomitinib,

gefitinib and osimertinib) have been explored, their clinical

efficacy is limited by tumor heterogeneity, resistance mechanisms

and poor BBB penetrance (143).

Resistance arises from compensatory signaling activation (such as

PI3K and MET), and mutations like C797S and G724S that hinder drug

binding (144). Emerging

approaches, such as antibody-drug conjugates (for example,

ABT-414), show promise but face challenges, including loss of EGFR

amplification in resistant clones and inefficient BBB penetration

(145).

Combination therapies targeting both EGFR and

downstream effectors (for example, DDR1 and KRAS-driven MAPK

activation) have demonstrated synergistic effects in overcoming

resistance. However, improved specificity of EGFR inhibitors for

GBM-associated mutations and combinatorial strategies are crucial

for advancing GBM treatment.

Efforts to inhibit the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway using

drugs such as GDC-0068 and GDC-0084 have shown potential, but

resistance often arises (146-148).

Studies focusing on the BRAF V600E mutation in a small fraction of

gliomas have demonstrated that second- and third-generation BRAF

inhibitors, combined with MEK inhibitors, may provide some benefit.

However, the limited presence of BRAF mutations in gliomas reduces

the overall impact of these findings.

In addition to the aforementioned small kinase

inhibitors, other inhibitors targeting MET, FGFR, vascular

endothelial growth factor receptor, MEK and PKCβ have been

evaluated in clinical trials for GBM (21,149). However, these agents demonstrated

limited efficacy, likely due to the acquisition of resistance.

Resistance mechanisms to kinase inhibitors in GBM

can be broadly categorized into four groups: Mutations,

coactivation of multiple RTKs, adaptation and alternative routes

(bypass).

Mutations. Patients with GBM often possess

mutations in the extracellular domain of kinases, unlike other

types of cancer. EGFR mutations in GBM primarily occur in the

extracellular domain, and this difference in mutation location may

contribute to primary resistance (150).

Coactivation of multiple RTKs. GBMs often

have multiple activated RTKs within a tumor, such as EGFR, ERBB3,

PDGFR and MET (151), granting

them resistance to single-agent inhibition.

Adaptation. Tumors can adapt to treatments

over time. As discussed previously, GBM cells can suppress EGFRvIII

protein expression in response to erlotinib treatment (152).

Alternative routes (bypass). Tumors can

activate alternative signaling pathways to bypass the inhibited

kinase. Examples include NF-κB pathway activation in response to

combined EGFR and MET inhibition (153) and IGF-1R activation mediates

resistance to EGFR inhibitors through activation of PI3K and AKT

signaling (154).

IDH mutations are highly prevalent in >80% of

WHO grade II/III gliomas, frequently occur in secondary

glioblastomas (73% of cases), and are rare in primary glioblastomas

(3.7%) (155). IDH-mutant GBM

cells show synthetic lethality with PARP inhibitors due to impaired

HR repair pathways. Several PARP inhibitors are under clinical

investigation for GBM treatment.

Olaparib can cross the BBB but did not meet

response-based thresholds in patients with IDH-mutant glioma

(156). Niraparib was shown to

exhibit improved tumor exposure and sustainability than olaparib,

with ongoing studies evaluating its combination with radiotherapy.

By contrast, IDH1/2-wildtype gliomas show limited tumor-suppressing

effects with PARP inhibitors due to functional BRCA1/2 recruitment

to the HR repair pathway.

IDH inhibitors such as ivosidenib and vorasidenib

have been developed to block the production of the oncometabolite

D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D-2-HG). D-2-HG drives gliomagenesis via

epigenetic alterations, including hypermethylation that silences

tumor suppressor genes and maintains stemness. While these

IDH1/IDH2 inhibitors show promise in early clinical trials

(157), resistance mechanisms

remain an active area of investigation.

In conclusion, targeted therapies have shown

success in other types of cancer, but not in GBM. New studies and

clinical trials should address and solve this problem using

preclinical models, improving BBB penetration and assessing

combination therapies.

6. Resistance to immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown success in

other types of cancer but have failed to show efficacy in GBM.

Nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) plus radiotherapy

failed to improve OS compared with the standard treatment of

radiotherapy plus TMZ (158).

Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab, though it induced T

cell-cell and cDC1 activation, failed to counteract the

immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in recurrent

GBM (159). Both intrinsic and

acquired resistance mechanisms contribute to the absence of

efficacy of immunotherapy in GBM, as described below.

Immunosuppressive TME. GBM creates an

environment that supports immune evasion through TAMs, GSCs and

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (160,161). These suppress cytotoxic T cells

and promote immune evasion by upregulating immunosuppressive

proteins like CHI3L1(162).

Furthermore, the loss of S1P1 receptor on T-cell surface promotes

T-cell dysfunction due to the sequestering of T-cells within the

bone marrow (163).

Tumor heterogeneity. Tumor heterogeneity,

discussed in the previous sections, contributes to immunotherapy

resistance in GBM at both the molecular and cellular levels,

allowing a range of subclonal populations with distinct genetic

mutations and developmental states to coexist and evolve within the

same tumor (43,164). This diversity enables

therapy-resistant clones to survive treatment, adapt and repopulate

the tumor, often with new genetic alterations, ultimately driving

tumor recurrence and rendering monotherapies and some combination

therapies ineffective.

To improve outcomes, immune-based therapies should

be combined with approaches targeting the immunosuppressive

mechanisms of glioblastoma. For example, co-targeting chemokine

receptors such as CXCR4, often overexpressed in GBMs, alongside

immune-checkpoint inhibitors has shown potential in preclinical

studies (165). Rational

combinations of therapies addressing tumor-immune compositional

changes and leveraging immune-stimulatory mechanisms may maximize

therapeutic success.

7. Conclusion and future directions

Despite decades of research, GBM remains among the

most refractory of cancers. The current treatment paradigm is

consistently undermined by a constellation of resistance

mechanisms, ranging from poor drug penetration across the BBB and

intra-tumoral heterogeneity to robust compensatory signaling and

immune evasion.

Key mechanisms of drug resistance in GBM include

limited drug penetration due to the BBB and its variable

permeability, as well as active drug efflux by ATP-binding cassette

transporters. The extensive heterogeneity of GBM, including

molecular, genetic, cellular and spatial heterogeneity, gives rise

to therapy-resistant subpopulations, notably GSCs. The TME,

characterized by hypoxic niches and immunosuppressive myeloid

cells, further facilitates resistance to both targeted and immune

therapies. In addition, resistance is driven by intrinsic factors

such as DNA repair activity (for example, MGMT expression or MMR

defects), mutations in critical signaling pathways (such as p53, Rb

or RTK/Ras/PI3K) and metabolic rewiring. GBM cells also exhibit

antioxidant upregulation and dysregulated alternative splicing, all

of which contribute to a formidable capacity to evade therapy

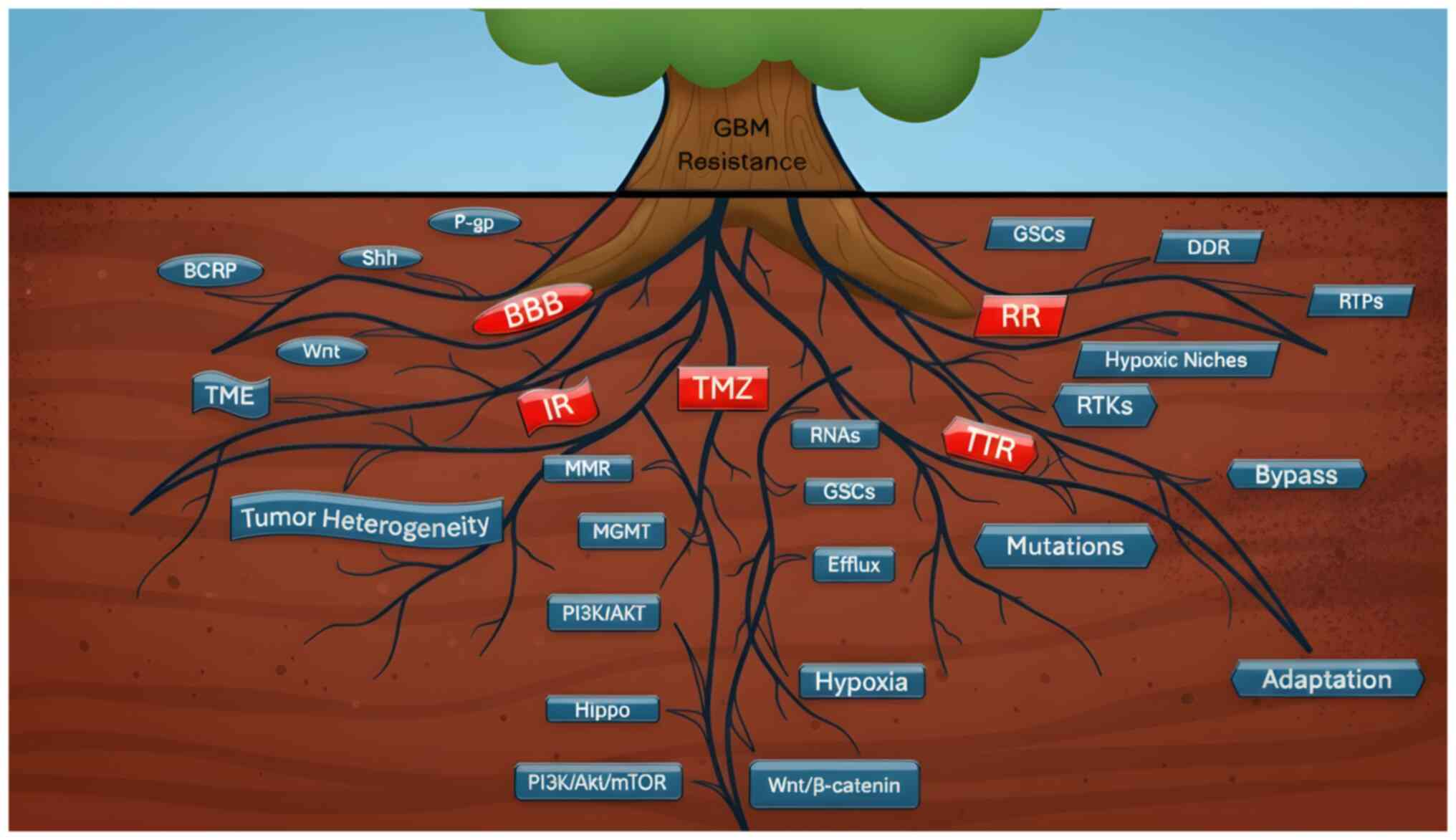

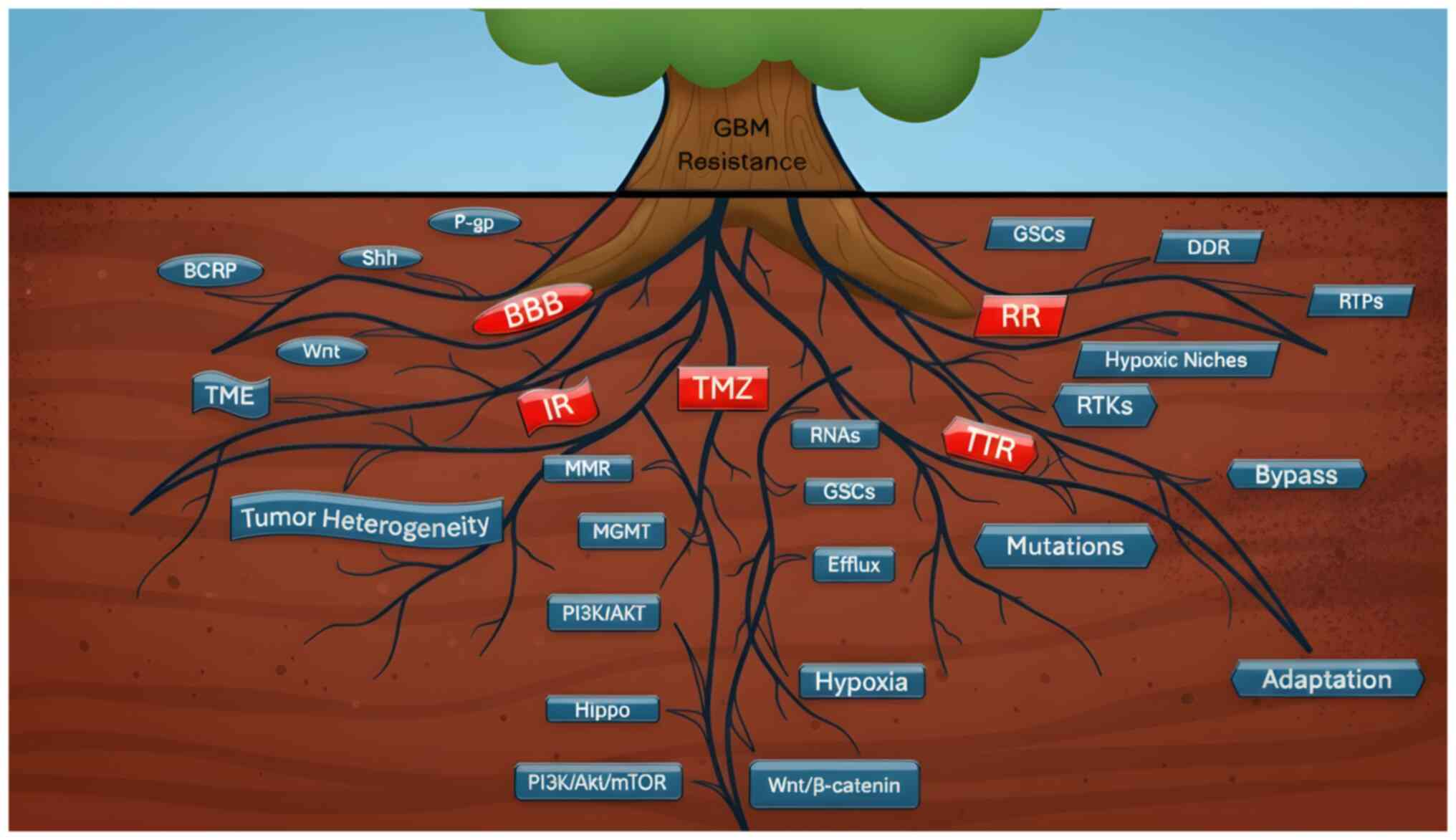

(Fig. 1).

| Figure 1Root causes of therapeutic resistance

in GBM. Schematic representation of the interconnected mechanisms

that sustain GBM resistance, depicted as a tree where the visible

trunk represents clinical resistance and the hidden root system

illustrates its molecular and cellular drivers. Major resistance

categories are highlighted in red as BBB, IR, TMZ resistance, RR

and TTR. BBB serves as a physical barrier co-opted by the tumor to

reduce drug penetration. Overexpression of efflux transporters such

as P-gp and BCRP in tumor endothelial cells decreases intracellular

drug concentrations, while dysregulation of Wnt and Shh pathways

further limits permeability. IR is reinforced by the highly

immunosuppressive TME, which includes TAMs, GSCs and MDSCs that

suppress cytotoxic T-cell activity. Molecular heterogeneity further

sustains therapy-resistant clones. TMZ resistance is driven by MGMT

upregulation, DNA MMR defects and activation of PI3K/Akt, Hippo and

Wnt/β-catenin pathways. Additional contributors include efflux

transporters, GSCs, a hypoxic TME and exosomal RNAs. TTR reflects

the failure of precision approaches despite subtype-specific

alterations (EGFR in classical, PDGFR in proneural, NF-κB in

mesenchymal GBM). Resistance mechanisms include kinase domain

mutations, RTK coactivation (EGFR, ERBB3, PDGFR, MEK), adaptive

suppression of EGFRvIII and bypass signaling via NF-κB or

IGF1R-PI3K/AKT activation. RR arises from hypoxia, enhanced DDR and

GSC-mediated repair capacity. RTP cells survive through homologous

recombination and non-homologous end joining. Together, these

mechanisms form a deeply interconnected ‘root system’ that allows

GBM to withstand chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy and

immunotherapy. This conceptual framework emphasizes that resistance

arises not from a single pathway but from a dynamic, adaptive

network, underscoring the need for rational combination regimens,

precision therapies, and innovative delivery strategies to overcome

therapeutic failure in GBM. GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; BBB,

blood-brain barrier; IR, immunotherapy resistance; TMZ,

temozolomide; RR, radiotherapy resistance; TTR, targeted therapy

resistance; TME, tumor microenvironment; TAM, tumor-associated

macrophage; GSC, glioma stem-like cell; MDSC, myeloid-derived

suppressor cell; MGMT, O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase; EGFR, epidermal growth factor; MMR, mismatch

repair; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor; RTL, receptor

tyrosine kinase; DDR, DNA damage response; RTP, radiation-tolerant

persister; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; BCRP, breast-cancer-resistance

protein; Shh, sonic hedgehog; MEK, mitogen-activated protein

kinase. |

The present review emphasizes that overcoming such

multifaceted resistance requires more than additive or sequential

strategies; it demands mechanistically informed, rational

combinations that account for the adaptive plasticity of GBM. For

example, combining PI3K/mTOR inhibitors with agents targeting

downstream anti-apoptotic proteins (such as Bcl-2 or Mcl-1) may

disrupt resistance circuits more effectively than monotherapy.

Similarly, dual inhibition of the MAPK and autophagy could thwart

adaptive survival mechanisms.

Rather than relying on generic combination

therapies, future strategies should emphasize biologically

justified, context-specific approaches tailored to the molecular

and cellular landscape of each patient's tumor. Progress will also

depend on bridging the translational gap between preclinical models

and clinical endpoints, particularly in evaluating therapies

targeting rare subpopulations or modulating the TME.

In summary, advancing GBM therapy demands a

paradigm shift, from reactive management of resistance to

proactive, mechanistically anchored intervention, with a relentless

focus on therapeutic precision and clinical feasibility.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YKD drafted and wrote the manuscript. RP provided

critical review, edits, intellectual inputs, and overall guidance.

Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

National Cancer Institute: Cancer Stat

Facts: Brain and Other Nervous System Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/brain.html.

|

|

2

|

National Center for Health Statistics: