Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) poses a global health

burden with the highest incidence rates in Southeast Asia, South

China and North Africa. Based on the 2020 global cancer statistics,

there were ~133,000 new cases of NPC worldwide, accounting for 0.7%

of all newly diagnosed cancer cases, with 80,000 deaths,

representing 0.8% of global cancer deaths (1). Both incidence and mortality rates

have increased compared with 2018 statistics (129,079 new cases and

72,987 deaths), suggesting a potential upward trend (2). In 2022, China is estimated to have

~64,165 new cases of NPC and 36,315 deaths (3), despite advancements in diagnostic and

therapeutic technologies, NPC incidence and mortality rates have

not substantially declined. Common clinical manifestations of NPC

include nasal congestion, epistaxis, otalgia or ear fullness,

hearing loss, diplopia and headaches. Currently, a combination of

chemotherapy and radiotherapy is a key strategy for treating

advanced-stage NPC. Due to improvements in diagnostic imaging,

early detection through large-scale screening, and the emergence of

Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT), the survival rate of

locally advanced NPC has increased (4,5).

However, even after treatment, ~5-15% of patients with advanced NPC

experience local recurrence, and clinical manifestations of distant

metastasis are observed in 15-30% of patients (4). Distant metastasis is the most common

post-treatment failure pattern (6). For locally advanced NPC, clinical

trials have demonstrated that adjuvant chemotherapy after

radiotherapy significantly improves the failure-free survival rate

in patients with advanced NPC. It is not only manageable in terms

of safety but also does not affect the quality of life (7).

Previous studies have explored the impact of

clinical, histological and biochemical factors on patients with

NPC. Among them, disease staging and plasma Epstein-Barr virus

(EBV) DNA concentration have been considered routine prognostic

factors in clinical practice (8,9).

Baseline serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels are also

associated with prognosis in patients with NPC undergoing radical

IMRT treatment (10). However,

even among patients with identical disease stages and pretreatment

EBV DNA levels, NPC exhibits significant biological heterogeneity,

making prognosis prediction challenging. Exploring new prognostic

factors to guide clinical decisions and provide favorable and

accurate treatment for NPC patients is urgently needed.

Serum uric acid (SUA) is the final product of purine

metabolism, possessing dual functions of antioxidation and

pro-oxidation (11). As a systemic

antioxidant, it plays a crucial role in protecting cells from

damage induced by free radicals. Previous studies on elevated SUA

indicate a risk of poor survival in patients with advanced HCC

(12). Furthermore, research has

demonstrated a positive correlation between uric acid levels and

the incidence of kidney cancer, especially in female subjects

(13). Meanwhile, the latest

studies suggest the practicality of UA as a clinical target for

breast cancer prevention. The public and clinical significance of

reducing SUA may help reduce the incidence of breast cancer in

overweight postmenopausal women (14). Most previous studies have focused

on pre-treatment SUA, observing its predictive role in diseases,

with little exploration of post-chemotherapy SUA. The predictive

value of SUA levels after the end of the treatment cycle in

patients with advanced NPC has not been determined. The present

study aimed to confirm whether post-chemotherapy SUA levels have

prognostic significance for patients with advanced NPC, potentially

informing optimal treatment selection.

Materials and methods

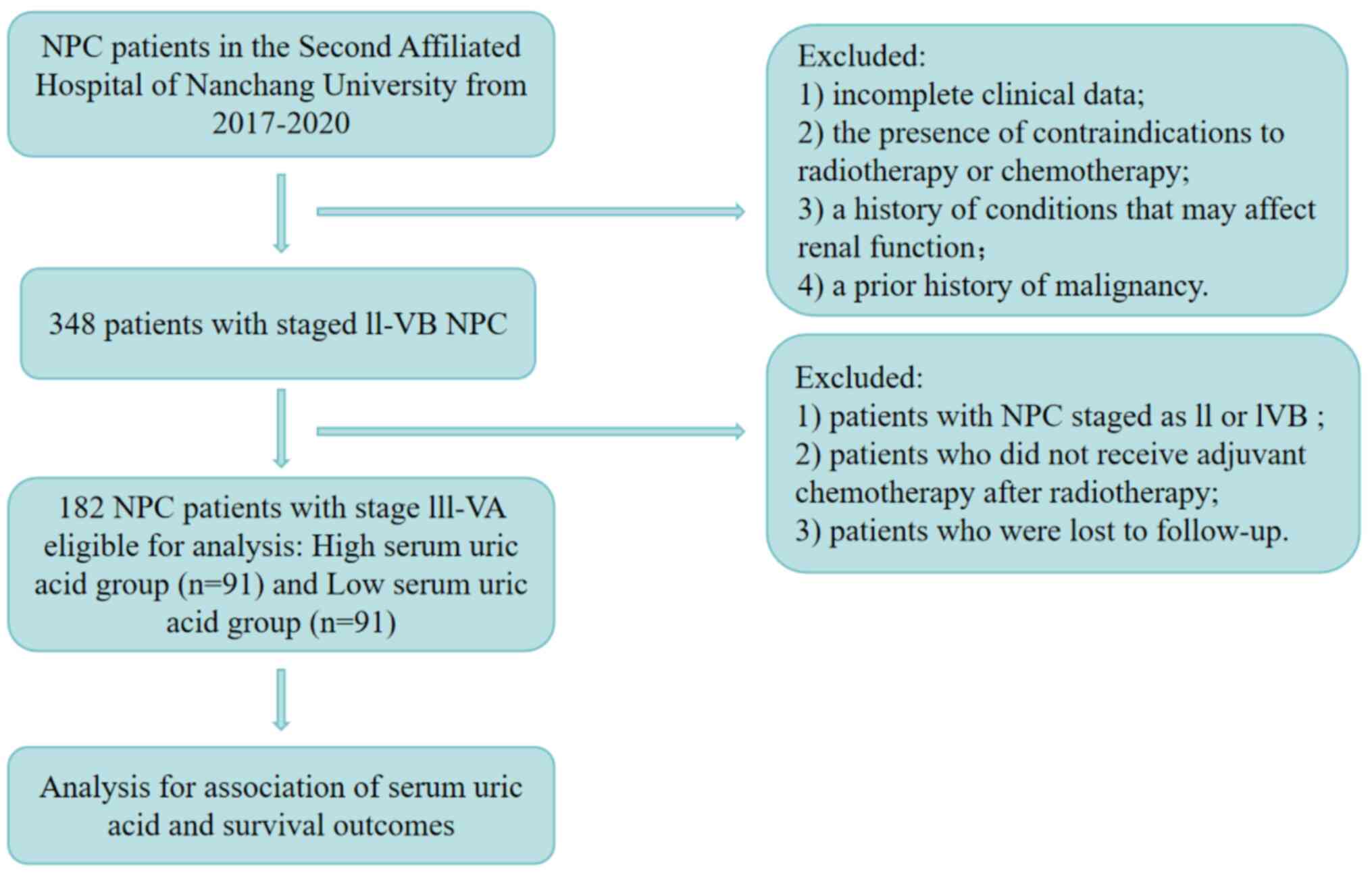

The present study included 182 patients with locally

advanced NPC who were admitted in January 2020, confirmed by

pathological diagnosis and without distant metastasis at

presentation. The cohort consisted of 119 male (65.4%) and 63

female (34.6%) patients. The median age was 50 years (range: 18-78

years). Inclusion criteria (all required): i) Patients initially

diagnosed with NPC by the Department of Pathology of The Second

Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China); ii)

exclusion of hyperuricemia or gout before treatment; iii) patients

staged from III to IVb according to the 7th edition of AJCC staging

criteria in 2010; iv) patients who have not undergone antitumor

treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy in other

hospitals; and v) availability of complete clinical data. Exclusion

criteria (any of the following): i) Patients with incomplete

clinical data; ii) patients with contraindications to radiotherapy

and chemotherapy; iii) patients with a history of diabetes,

hypertension, rheumatic autoimmune diseases, or other conditions

that may affect kidney function; iv) patients with a history of

hyperuricemia, gout, renal insufficiency, or other conditions

affecting SUA levels; v) patients with a history of malignant

tumors; vi) patients concurrently suffering from malignant tumors

in other organs; and vii) patients who did not complete

intensity-modulated radiation therapy within the specified time.

Pretreatment evaluation included blood biochemistry, fiberoptic

nasopharyngoscopy, nasopharyngeal and neck magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI), chest computed tomography (CT), abdominal

ultrasonography and whole-body bone scan. All SUA measurements were

performed in the same central laboratory of the Second Affiliated

Hospital of Nanchang University following standardized clinical

procedures. The flowchart for patient selection is shown in

Fig. 1.

Treatment methods

The present study was approved (approval no.

IIT-O-2023-169; Nanchang, China) by the Ethics Committee of the

Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. All 182 patients

received comprehensive treatment.

Regarding chemotherapy, all patients were treated

under a comprehensive model for advanced NPC. This model combines

induction chemotherapy with adjuvant chemotherapy based on radical

IMRT. Regardless of concurrent or sequential chemotherapy, all

patients completed the full course of induction chemotherapy and

adjuvant chemotherapy. The chemotherapy regimen included drugs such

as gemcitabine, docetaxel, or paclitaxel in combination with

platinum-based agents. The platinum-based chemotherapy drugs used

were cisplatin, carboplatin, or nedaplatin. Of the included

patients with NPC, 100 (54.9%) received concurrent chemotherapy.

Monotherapy (single-agent gemcitabine or single-agent

platinum-based synchronous chemotherapy) and combination

chemotherapy with two drugs were used as synchronous chemotherapy

regimens. The two-drug chemotherapy was based on platinum

agents.

Radiotherapy was planned according to the 2010 NPC

Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy Target Area and Dose Design

Expert Consensus, and the 2017 NPC Clinical Target Volume

International Guidelines, and other relevant literature.

Radiotherapy planning followed the 2010 NPC Intensity-Modulated

Radiation Therapy Target Area and Dose Design Expert Consensus and

the 2017 NPC Clinical Target Volume International Guidelines. The

prescribed doses for each planned target area are as follows: the

primary tumor (GTVnx) is 70-74 Gy, positive lymph nodes (GTVnd) is

66-70 Gy, high-risk clinical target volume (CTV1) is 60-66 Gy,

ow-risk clinical target volume (CTV2) is 56-60 Gy, and bilateral

neck lymph drainage area (CTVLn) is 50-54 Gy. Patients included in

the study were treated with conventional radiotherapy, once a day,

5 times a week. According to the standards of the Radiation Therapy

Oncology Group 0255 trial, the irradiation doses to organs at risk

were kept within the specified tolerable dose range (6). Patients with MRI-detected residual

lesions after intensified radiotherapy received an additional 2-3

fractions of 4-6 Gy to improve local control. For well-responding

small primary lesions, a slight reduction in the total dose can be

considered (for example, 66-68 Gy). Overall, out of 182 patients,

82 received only IMRT, and 100 patients received concurrent

chemotherapy on the basis of IMRT. Treatment modifications were

made for patients with age-related limitations or organ dysfunction

that might indicate intolerance to standard chemotherapy

regimens.

Follow-up and statistical

analysis

Follow-up commenced from the date of NPC treatment

and continued until patient death or the last follow-up. Survival

endpoints include overall survival (OS), progression-free survival

(PFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) and locoregional

relapse-free survival (LRFS). OS was defined as the time from the

initiation of treatment to death from any cause or the last

follow-up if no death occurred; PFS was defined as the time from

the initiation of treatment to disease progression, death from any

cause, or the last follow-up, whichever occurred first. DMFS was

defined as the time from the initiation of treatment to the

occurrence of distant metastasis or the last follow-up if no

distant metastasis occurred. LRFS was defined as the time from the

initiation of treatment to the first local primary lesion or neck

lymph node treatment failure (including recurrence) or the last

follow-up if no treatment failure occurred. Patients were assessed

every 3 months for the first 3 years, and then every 6 months

thereafter until death. The last follow-up time was July 15, 2023,

with a median follow-up time of 50 months (range 30.0-71.0

months).

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

26.0 software (IBM Corp.). Survival analysis employed the

Kaplan-Meier method, with log-rank tests for comparing two groups.

Continuous variables were compared using independent samples

t-tests, while categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square

tests. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox

proportional hazards model, with independent significance tested by

backward elimination of non-significant explanatory variables. All

trials include host factors (including age and sex) and clinical

factors (including T classification, N classification and the

presence of synchronous radio-chemotherapy) as covariates. The

statistical significance criterion was set at P<0.05, with

P-values using two-sided tests. A repeated measures analysis of

variance was employed to compare pretreatment SUA, post-induction

chemotherapy SUA, post-radiotherapy SUA and post-adjuvant

chemotherapy SUA for all patients.

Results

Patient characteristics and

prognosis

Baseline characteristics of 182 patients with NPC

were analyzed to evaluate correlations between SUA levels and

clinical features. Patients were stratified into high (SUA >350

µmol/l) and low (SUA ≤350 µmol/l) groups based on the median

post-adjuvant chemotherapy SUA level (350.48 µmol/l) of the entire

cohort. This median value was close to the upper limit of the

normal reference range for SUA in numerous clinical laboratories,

thus providing both a statistical and clinically relevant cutoff

point for analysis. Demographically, the mean ages of the two

groups were 51.77 years and 49.11 years, respectively, showing a

slight but statistically significant difference (P=0.026). In terms

of sex distribution, a higher proportion of men were observed in

the higher SUA group (69.2 vs. 61.5%, P=0.027), while women were

slightly more prevalent in the lower SUA group. WHO Type III was

the predominant histopathological subtype in both groups (70.4 and

76.9%), with no statistically significant difference (P=0.313).

There was also no statistically significant difference in the

distribution of EBV-DNA status between the two groups (P=0.182).

Smoking history and family history did not show statistically

significant differences between the groups (P=0.553). Regarding TNM

staging, the proportions of T3-T4 and N2-N3 stages were slightly

higher in the high SUA group; only N staging approached statistical

significance (P=0.097), while T staging showed no statistically

significant difference (P=0.344). Treatment modalities

(radiotherapy alone vs. chemoradiotherapy) were similarly

distributed between the two groups (P=0.766). These baseline data

(Table I) provide important

context for further analysis of the impact of SUA levels on

treatment response and prognosis in patients with NPC.

| Table IDemographical characteristics and

clinical data of the patients. |

Table I

Demographical characteristics and

clinical data of the patients.

| Characteristics | SUA after treatment

of IC ≤350 µmol/l (%) | SUA after treatment

of IC >350 µmol/l (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Total | 91 (50.0%) | 91 (50.0%) | |

| Age (years, mean ±

SD) | 51.77±8.95 | 49.11±11.87 | 0.026 |

| Sex | | | 0.027 |

|

Male | 56 (61.5%) | 63 (69.2%) | |

|

Female | 35 (38.5%) | 28 (30.8%) | |

| Pathological

type | | | 0.313 |

|

WhO II | 27 (29.6%) | 21 (23.1%) | |

|

Who III | 64 (70.4%) | 70 (76.9%) | |

| EBV-DNA status | | | 0.182 |

|

EBV-DNA

negative | 52 (57.1%) | 43 (47.3%) | |

|

EBV-DNA

positive | 39 (42.9%) | 48 (52.7%) | |

| Smoking

history | | | 0.553 |

|

No | 47 (51.6%) | 38 (41.8%) | |

|

Yes | 44 (48.4%) | 53 (58.2%) | |

| Family history of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma | | | 0.553 |

|

No | 84 (92.3%) | 86 (94.5%) | |

|

Yes | 7 (7.7%) | 5 (5.5%) | |

| T stage | | | 0.344 |

|

T1-T2 | 33 (36.3%) | 27 (29.7%) | |

|

T3-T4 | 58 (63.7%) | 64 (70.3%) | |

| N stage | | | 0.097 |

|

N0-N1 | 30 (33.3%) | 20 (22.0%) | |

|

N2-N3 | 61 (67.0%) | 71 (78.0%) | |

| Chemotherapy | | | 0.766 |

|

Radiotherapy

alone | 40 (44.0%) | 42 (46.2%) | |

|

Chemoradiotherapy | 51 (56.0%) | 49 (53.8%) | |

Correlation of post-treatment uric

acid levels with prognosis

At the end of follow-up, 6 cases (3.2%) had local or

regional recurrence, and 15 cases (8.2%) had distant metastasis,

including 5 cases of lung metastasis, 2 cases of bone metastasis, 3

cases of liver metastasis, 1 case of lymph node metastasis, 3 cases

of multiple-site metastasis, and 1 case of metastasis to other

sites (cardia). In total, 22 patients (12.2%) succumbed, including

20 due to tumor progression, 1 due to cerebral infarction, and 1

due to other causes.

After completing the entire treatment cycle, the

median SUA level for the entire cohort was 350.48 µmol/l.

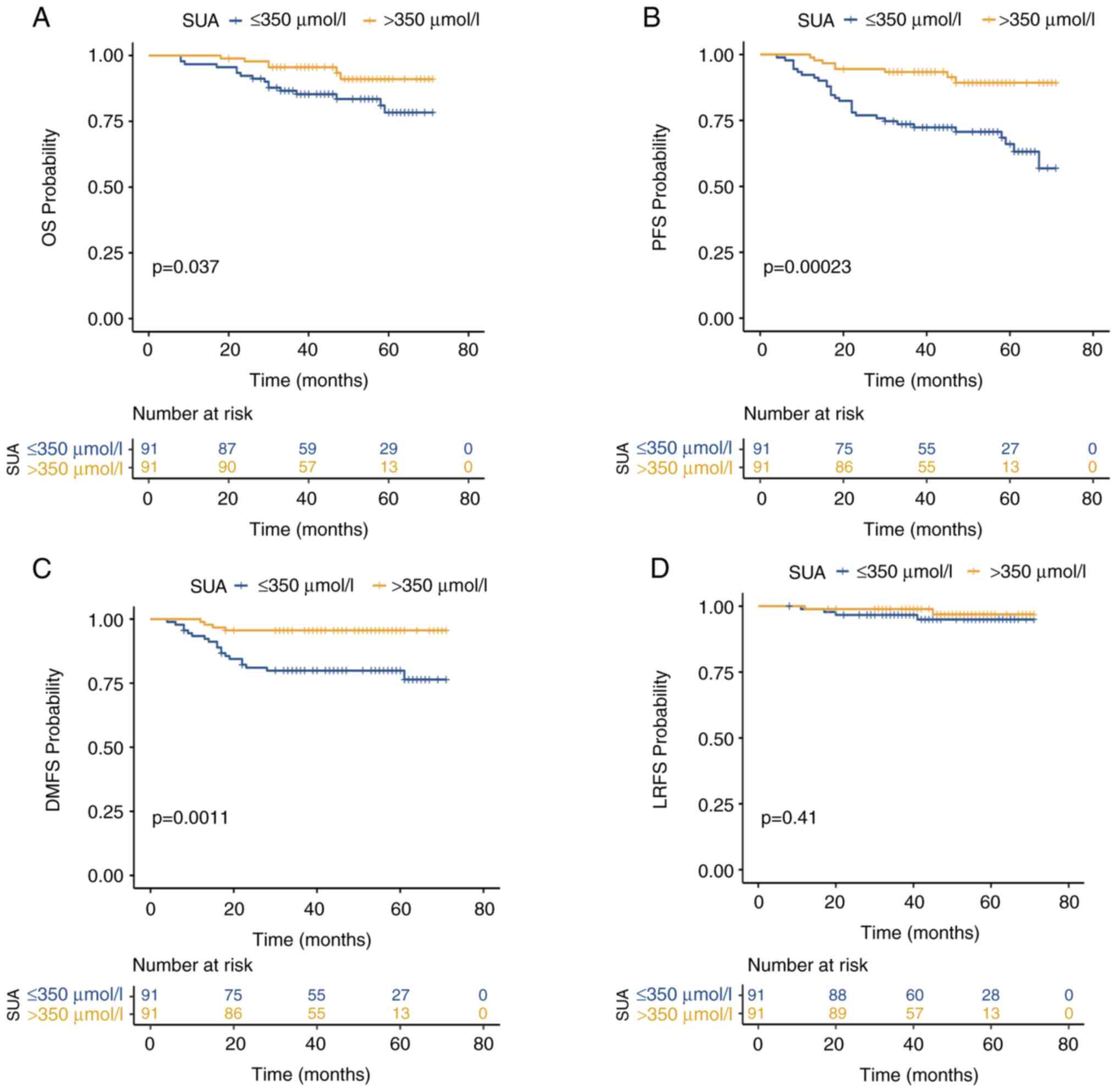

Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significantly superior 3-year OS,

PFS and DMFS in the high SUA group compared with the low SUA group:

3-year OS, 95.6% [95% confidence interval (CI):8 5.54-90.30%] vs.

85.3% (95% CI: 79.14-88.57%; P=0.037) (Fig. 2A); 3-year PFS, 93.4% (95% CI:

88.44-95.48%) vs. 72.4% (95% CI: 64.44-78.48%; P<0.001)

(Fig. 2B). In the 3-year DMFS

analysis, the survival rate was 95.6% (95% CI: 86.14-98.90%c)

compared with 79.9% (95% CI: 71.72-86.10%; P=0.0011) (Fig. 2C). However, there was no

statistically significant difference in the 3-year LRFS between the

two groups: 98.9% (95% CI: 94.12-99.44%) vs. 94.9% (95% CI:

88.39-97.91%; P=0.41) (Fig. 2D).

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for these four subgroups are

shown. Post-treatment SUA levels showed statistically significant

associations with OS, PFS and DMFS (P=0.037, P<0.001 and

P<0.001, respectively). Patients with higher uric acid levels

have improved survival rates. However, these increases do not

indicate a significant correlation between uric acid levels and

LRFS rates (P=0.41).

Prognostic factors for survival

outcomes in NPC: Univariate and multivariate analysis

The present retrospective study aimed to evaluate

the prognostic factors influencing survival outcomes in patients

with NPC by assessing the association between various clinical

variables and patient outcomes, particularly OS, PFS, DMFS and

LRFS. The univariate analysis indicated that age (P=0.007) and

EBV-DNA status (P=0.012) were significantly associated with OS. In

the multivariate analysis, age [hazard ratio (HR): 1.059, 95% CI:

1.012-1.108; P=0.013] and EBV-DNA status (HR: 4.043; 95% CI:

1.576-10.44; P=0.004) remained independent prognostic factors of

OS. An increase in age was associated with a higher HR for

decreased OS, and EBV-DNA positivity was linked to a worse

prognosis. The univariate analysis showed that age (P=0.22), sex

(P=0.04), EBV-DNA status (P=0.003) and N stage (P=0.013) were

associated with PFS. In the multivariate analysis, sex (HR: 2.530;

95% CI: 1.098-5.826; P=0.029), EBV-DNA status (HR: 3.631, 95% CI:

1.816-7.258; P<0.001) and N stage (HR: 5.004, 95% CI:

1.516-15.52; P=0.008) were confirmed as independent predictors of

PFS. Male sex, EBV-DNA positivity and advanced N stage were all

associated with a higher risk of disease progression. The

univariate analysis identified sex (P=0.039), EBV-DNA status

(P=0.024) and N stage (P=0.169) as factors associated with DMFS. In

the multivariate analysis, sex (HR: 5.023; 95% CI: 1.475-17.10;

P=0.01) and EBV-DNA status (HR 3.851; 95% CI: 1.562-9.490; P=0.003)

emerged as independent predictors of DMFS. Male sex and EBV-DNA

positivity were associated with a higher risk of distant

metastasis. The univariate analysis revealed that pathological type

(P=0.054) and T stage (P=0.033) were associated with LRFS. However,

in the multivariate analysis, only SUA level (HR: 0.149; 95% CI:

0.050-0.442; P=0.001) was confirmed as an independent predictor of

DMFS. Lower SUA levels were associated with a higher risk of LRFS.

SUA level was found to be a significant prognostic factor for OS

(multivariate HR: 0.265; 95% CI: 0.101-0.690; P=0.007), PFS

(multivariate HR: 0.168; 95% CI: 0.076-0.372; P<0.001) and DMFS

(multivariate HR: 0.149; 95% CI: 0.050-0.442; P=0.001). Higher SUA

levels were consistently associated with better outcomes across

these endpoints (Table II).

| Table IIUnivariate and multivariate analysis

of prognostic factors for patients with nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. |

Table II

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of prognostic factors for patients with nasopharyngeal

carcinoma.

| | Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| Endpoint | Variable | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) |

|---|

| OS | Age | 0.007 | 1.072

(1.019-1.028) | 0.013 | 1.059

(1.012-1.108) |

| | Sex | 0.284 | 1.726

(0.636-4.686) | | |

| | Pathological

type | 0.651 | 1.230

(0.501-3.020) | | |

| | EBV-DNA status | 0.012 | 3.255

(1.297-8.170) | 0.004 | 4.043

(1.576-10.44) |

| | Smoking

history | 0.869 | 1.078

(0.467-2.489) | | |

| | Family history of

NPC | 0.185 | 0.438

(0.129-0.483) | | |

| | T stage | 0.346 | 1.552

(0.622-3.872) | | |

| | N stage | 0.034 | 9.038

(1.185-68.96) | | |

| | Chemotherapy | 0.377 | 1.477

(0.622-3.511) | | |

| | SUA level | 0.028 | 0.344

(0.133-0.890) | 0.007 | 0.265

(0.101-0.690) |

| PFS | Age | 0.220 | 1.022

(0.987-1.058) | | |

| | Sex | 0.040 | 2.361

(1.038-5.368) | 0.029 | 2.530

(1.098-5.826) |

| | Pathological

type | 0.068 | 1.866

(0.973-3.577) | | |

| | EBV-DNA status | 0.003 | 2.806

(1.411-5.580) | 0.000 | 3.631

(1.816-7.258) |

| | Smoking

history | 0.587 | 1.194

(0.629-2.264) | | |

| | Family history of

NPC | 0.264 | 1.807

(0.640-5.105) | | |

| | T stage | 0.776 | 1.102

(0.563-2.160) | | |

| | N stage | 0.013 | 3.865

(1.323-11.29) | 0.008 | 5.004

(1.516-15.52) |

| | Chemotherapy | 0.350 | 1.368

(0.709-2.640) | | |

| | SUA level | 0.000 | 0.238

(0.108-0.526) | 0.0001 | 0.168

(0.076-0.372) |

| DMFS | Age | 0.635 | 0.990

(0.950-1.032) | | |

| | Sex | 0.039 | 3.602

(1.069-12.13) | 0.010 | 5.023

(1.475-17.10) |

| | Pathological

type | 0.153 | 1.841

(0.797-4.253) | | |

| | EBV-DNA status | 0.024 | 2.809

(1.144-6.897) | 0.003 | 3.851

(1.562-9.490) |

| | Smoking

history | 0.606 | 1.242

(0.545-2.833) | | |

| | Family history of

NPC | 0.716 | 1.451

(0.195-10.77) | | |

| | T stage | 0.831 | 0.910

(0.381-2.173) | | |

| | N stage | 0.169 | 2.225

(0.712-6.953) | | |

| | Chemotherapy | 0.377 | 1.481

(0.619-3.541) | | |

| | SUA level | 0.002 | 0.180

(0.060-0.539) | 0.001 | 0.149

(0.050-0.442) |

| LRFS | Age | 0.237 | 1.061

(0.962-1.170) | | |

| | Sex | 0.426 | 0.522

(0.105-2.589) | | |

| | Pathological

type | 0.054 | 5.315

(0.972-29.06) | | |

| | EBV-DNA status | 0.731 | 1.328

(0.264-6.686) | | |

| | Smoking

history | 0.136 | 5.115

(0.597-43.78) | | |

| | Family history of

NPC | 0.662 | 2.251

(0.575-8.527) | | |

| | T stage | 0.033 | 0.073

(0.007-0.815) | | |

| | N stage | 0.579 | 0.498

(0.043-5.821) | | |

| | Chemotherapy | 0.439 | 1.969

(0.354-10.96) | | |

| | SUA level | 0.745 | 0.748

(0.130-4.292) | | |

Repeated measures analysis of SUA

levels at different time points in patients with NPC

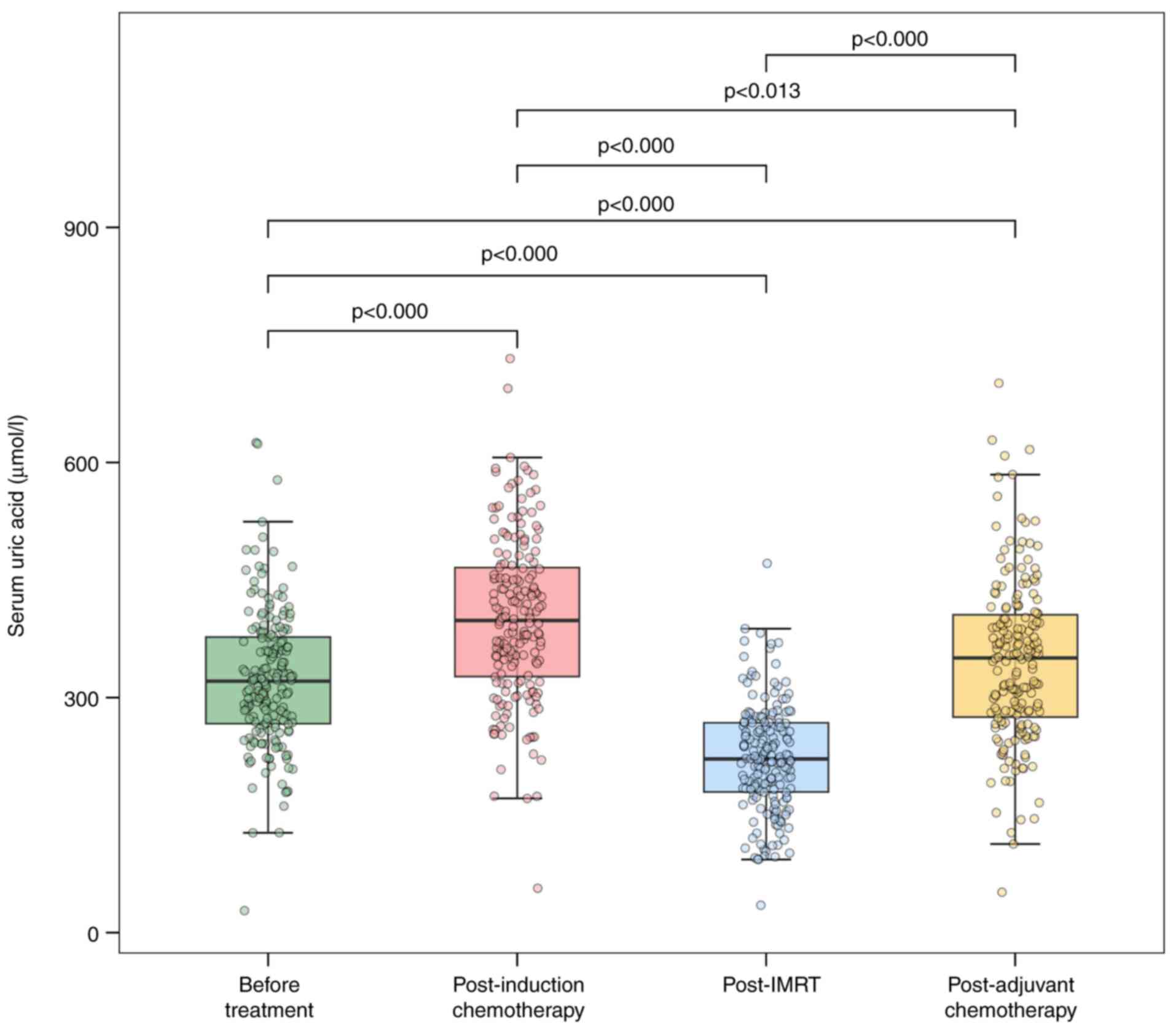

A total of 182 patients with NPC who completed

induction chemotherapy, radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy were

included in this study. SUA levels were measured at four time

points: Pretreatment [mean=323.69 µmol/l, standard deviation

(SD)=87.56 µmol/l), post-induction chemotherapy (mean=400.40

µmol/l; SD=104.45 µmol/l), post-radiotherapy (mean=222.84 µmol/l;

SD=68.47 µmol/l) and post-adjuvant chemotherapy (mean=346.24

µmol/l; SD=104.05 µmol/l). The Greenhouse-Geisser correction for

sphericity was applied, with an estimated ε=0.894, indicating a

significant difference in SUA levels across the four measurement

points [F (2.68, 485.25)=282.76; P<0.001, partial η²=0.61)].

Post-hoc multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni

adjustment revealed significantly lower SUA levels

post-radiotherapy compared with pretreatment [t(543)=-19.10;

P<0.001; Cohen s d=-1.47], post-induction chemotherapy

[t(543)=-29.15; P<0.001; Cohen s d=-2.59] and post-adjuvant

chemotherapy [t(543)=-18.50; P<0.001; Cohen s d=-1.80].

Repeated-measures ANOVA confirmed that SUA levels were lowest

post-radiotherapy compared with all other time points (Fig. 3).

Discussion

SUA, the end product of purine metabolism excreted

by the kidneys and intestines, is a potent antioxidant that

scavenges singlet oxygen and free radicals (15). Its role in tumor biology is complex

and not fully understood, with elevated levels potentially

inhibiting or promoting tumorigenesis. Numerous clinical studies

have investigated the association between SUA and the prognosis of

various cancers, reporting correlations with tumor incidence,

mortality and metastatic potential. Theoretically, elevated SUA

levels may prevent tumor occurrence by enhancing antioxidant

effects. However, extensive research results suggest that elevated

SUA levels are associated with increased tumor incidence, mortality

rates (12-14,16-22)

and promotion of tumor metastasis (23). Previously, an increasing body of

research has confirmed that elevated SUA levels can have a

protective effect, contributing to improved patient survival rates

(24-27).

Therefore, it was investigated whether SUA levels correlate with

OS, PFS, DMFS and LRFS in patients with NPC following induction

chemotherapy, IMRT and adjuvant chemotherapy.

In the present study, based on the median uric acid

level in the plasma after adjuvant chemotherapy being 350.45

µmol/l, 182 patients with NPC who completed the full treatment

course were divided into two groups, the high SUA group (SUA

>350 µmol/l) and the low SUA group (SUA ≤350 µmol/l). The

results showed that post-adjuvant chemotherapy SUA levels could

serve as prognostic biomarkers for OS, PFS and DMFS. The OS, PFS

and DMFS were significantly higher in the high SUA group than in

the low SUA group (P=0.037, P<0.001 and P=0.001, respectively).

However, the LRFS difference showed no statistical significance

(P=0.424). Multifactorial analysis has revealed that the SUA level

after adjuvant chemotherapy is an independent prognostic factor for

patients with NPC. The high SUA group has an improved prognosis

than the low SUA group, which is consistent with the conclusions of

the aforementioned study. Consistent with the present findings,

previous research reported increased SUA levels in patients with

metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) who responded favorably to

bevacizumab chemotherapy (28).

This is similar to the results of the present study, suggesting

that chemotherapy drugs may be effective in preventing the

formation of new microvascular beds in existing tumor tissues. This

relative difference between tumor tissues and supplying vascular

tissues leads to local ischemia and the subsequent hyperuricemia.

Thus, hyperuricemia appears to serve as an alternative biomarker

for the efficacy of bevacizumab in treating patients with

metastatic CRC.

In the present longitudinal observational study, SUA

levels were repeatedly measured at four time points (pretreatment,

post-induction chemotherapy, post-radiotherapy and post-adjuvant

chemotherapy) in these patients with NPC. Through in-depth

analysis, a significant decrease was observed in SUA levels

following radiotherapy. Patients were measured for uric acid

pretreatment (Mean, 323.69; SD, 87.56), after induction

chemotherapy (Mean, 400.40; SD, 104.45), after radiotherapy (Mean,

222.84; SD, 68.47), and after adjuvant chemotherapy (M, 346.24; SD,

104.05). According to repeated measures analysis of variance, uric

acid after radiotherapy was significantly lower than uric acid

pretreatment [t(543)=-19.10; P<0.001; d=-1.47], uric acid after

induction chemotherapy [t(543)=-29.15; P<0.001; d=-2.59] and

uric acid after adjuvant chemotherapy [t(543)=-18.5; P<0.001;

d=-1.80]. While the present study was not designed to elucidate the

precise mechanisms behind this decrease, several potential

contributing factors could be hypothesize based on clinical

observations. The observed decline may be attributed to a

combination of factors, including the systemic side effects of IMRT

(for example, damage to taste buds and salivary glands), which

often lead to decreased appetite and swallowing difficulties,

potentially resulting in reduced nutritional intake and lower

purine consumption. Furthermore, the catabolic state associated

with advanced cancer and gastrointestinal side effects from

platinum-based chemotherapy may exacerbate nutritional

deterioration. However, it is crucial to note that these

explanations remain speculative, and the present study lacks direct

biochemical or clinical data to confirm these specific mechanisms.

This represents an important direction for future research.

The observed correlation between elevated

post-adjuvant chemotherapy SUA and improved survival outcomes

warrants mechanistic discussion: SUA exhibits potent antioxidant

activity and is regarded as a major antioxidant in humans, which is

considered to scavenge free radicals and contribute to the total

antioxidant capacity of plasma. Studies have indicated that uric

acid, by providing antioxidant defense, plays a protective role in

red blood cells and nerve cells (29,30).

In the context of antitumor therapy, Ames et al (31) initially hypothesized that uric

acid, through its role as a scavenger of singlet oxygen and

hydroxyl radicals (products of singlet oxygen conversion), provides

a major defense against human cancer and inhibits lipid

peroxidation in red blood cells. Another study supporting the

antioxidant ability of uric acid is related to the link between

extensive oxidative stress parameters and colon cancer survival.

Their conclusion is that only higher levels of uric acid in plasma

are associated with longer survival in patients with colon cancer.

It was considered that uric acid acts as a major antioxidant by

clearing free radicals and stabilizing ascorbic acid in human serum

(32). This suggests that high SUA

concentration may have a protective effect on patients with NPC

after adjuvant chemotherapy, and elevated uric acid levels may be a

result of tumor lysis syndrome. Furthermore, by scavenging reactive

oxygen species (ROS) generated during radiotherapy and

chemotherapy, SUA might help in preserving immune cell function,

particularly that of T lymphocytes, thereby indirectly sustaining

an effective anti-tumor immune response. It is crucial to note that

these potential mechanisms-tumor lysis, immune activation and ROS

scavenging-are not mutually exclusive and may operate concurrently.

Future studies integrating serial immune monitoring and metabolic

profiling are essential to validate these hypotheses and decipher

the precise role of SUA in the context of NPC treatment.

As a head and neck malignancy, NPC is primarily

treated with IMRT due to its unique biological characteristics

(4). However, IMRT inevitably

induces side effects, as the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx and

adjacent esophagus are often exposed to substantial radiation

doses. Early side effects include decreased appetite, taste

disturbance and salivary gland dysfunction, and swallowing

difficulties, often leading to impaired nutritional intake

(33). It is advisable to adopt a

low purine diet. Moreover, malignant tumors themselves are a

wasting disease. As the tumor progresses, the patient s

physical function declines, nutritional status deteriorates, and

the body s consumption exceeds intake. Combined with the

gastrointestinal reactions caused by the platinum-based

chemotherapy drug cisplatin, the nutritional status of patients

rapidly deteriorates after radiotherapy (34). This may be a major reason for the

post-radiotherapy SUA levels being lower than those of

pretreatment.

However, the present study has several limitations.

First, this is a single-center, retrospective study, which may

limit the generalizability of the present findings to other patient

populations and clinical settings. Second, despite the

authors efforts to control for confounding variables via

strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, selection bias and

unmeasured confounders inherent in retrospective designs may still

exist. Factors such as detailed nutritional status, precise renal

function metrics (for example, estimated glomerular filtration

rate) and the use of medications affecting uric acid levels (for

example, diuretics and allopurinol) were not systematically

accounted for and could influence the results. Third, the median

follow-up duration is only 50 months, therefore extending the

follow-up period to evaluate the long-term prognosis of patients

with intermediate to locally advanced NPC is essential. Therefore,

these findings need confirmation through larger-scale prospective

studies, However, the cutoff value of 350 µmol/l for SUA, while

based on the median of the current cohort and aligned with common

clinical reference standards, was determined post-hoc. Future

studies are needed to validate this threshold prospectively or to

explore more granular risk stratification using SUA as a continuous

variable. Furthermore, as all participants were recruited from a

single center in Southern China, an endemic region for NPC, the

generalizability of the present findings to other populations with

different genetic backgrounds and NPC incidence rates requires

careful consideration. Ethnic and genetic variations, such as

differences in purine metabolism enzymes or the strong association

between NPC and EBV in endemic populations, might influence both

baseline SUA levels and the host-tumor interaction.

In this context, the current comparative analysis

demonstrated that the prognostic value of post-adjuvant

chemotherapy SUA is independent of and complementary to established

markers such as EBV-DNA and baseline LDH. This suggests that SUA

may reflect distinct pathophysiological processes, such as systemic

oxidative stress or metabolic alterations during treatment, which

are not fully captured by EBV-DNA or LDH. Therefore, incorporating

SUA into existing prognostic models could enhance risk

stratification and personalized management for patients with NPC.

The findings of the present study have a guiding role in the

personalized treatment and health management of patients with

cancer. The role of hyperuricemia as an independent risk factor for

the occurrence and progression of cancer remains controversial and

may vary by sex. Elevated SUA levels may be a valuable long-term

surrogate marker rather than an independent risk factor. However,

it is worth noting that although our research reveals the impact of

radiotherapy and chemotherapy on uric acid levels, which may be

used to assess the prognosis of patients with NPC after adjuvant

chemotherapy, the specific mechanism of uric acid on the efficacy

of radiotherapy and chemotherapy needs further study and

large-sample validation. Further biochemical experiments and

molecular biology studies will help elucidate the molecular

mechanisms behind these biochemical changes, providing a

theoretical basis for the development of new drugs and treatment

strategies. Incorporating detailed nutritional assessments, purine

metabolic profiling and renal function monitoring are warranted to

validate these hypotheses. In addition, as biomarker research

advances, exploring more correlations between biochemical

indicators and treatment outcomes is anticipated to achieve more

personalized and precise treatment approaches.

In conclusion, the present study identified

post-adjuvant chemotherapy SUA level as an independent prognostic

factor for OS, PFS and DMFS in patients with locally advanced NPC.

Future studies should perform mechanism-based preclinical

investigations to enable targeted regulation of SUA levels without

promoting tumor development and/or metastasis. This can predict the

risk of disease recurrence in NPC patients and guide the

development of effective treatment plans.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported in part, by the Jiangxi

natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 20202BAB206057), the

Applied Research Cultivation Program of Jiangxi (grant no.

20212BAG70047), the Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research

Foundation (grant no. Y-XD202001/zb-0002) and the Second Affiliated

Hospital of Nanchang University Funding Program (grant no.

2022efyB05).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

XH, QL and YD conceived and designed the study. ZH,

XC, JD, SL and RH were responsible for the acquisition of data. JLH

and ML performed the data analysis. LT, JW, SD and JZ interpreted

the results. LZ drafted the manuscript. All authors critically

revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. LZ is the guarantor

of this work and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data

and the accuracy of the analysis. XH, ML and LZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

(approval no. IIT-O-2023-169; Nanchang, China). The research was

carried out according to the guidelines of Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual

participants included in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S,

Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N and Chen W: Cancer Statistics in China

and United States, 2022: Profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin

Med J (Engl). 135:584–590. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun

Y and Ma J: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 394:64–80.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tang LL, Chen WQ, Xue WQ, He YQ, Zheng RS,

Zeng YX and Jia WH: Global trends in incidence and mortality of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 374:22–30. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ribassin-Majed L, Marguet S, Lee AWM, Ng

WT, Ma J, Chan ATC, Huang PY, Zhu G, Chua DTT, Chen Y, et al: What

is the best treatment of locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma?

An individual patient data network Meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol.

35:498–505. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chen YP, Liu X, Zhou Q, Yang KY, Jin F,

Zhu XD, Shi M, Hu GQ, Hu WH, Sun Y, et al: Metronomic capecitabine

as adjuvant therapy in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: A multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised,

controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 398:303–313. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lin JC, Wang WY, Chen KY, Wei YH, Liang

WM, Jan JS and Jiang RS: Quantification of plasma Epstein-Barr

virus DNA in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 350:2461–2470. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Leung SF, Zee B, Ma BB, Hui EP, Mo F, Lai

M, Chan KC, Chan LY, Kwan WH, Lo YM and Chan AT: Plasma

Epstein-Barr viral deoxyribonucleic acid quantitation complements

tumor-node-metastasis staging prognostication in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 24:5414–5418. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhou GQ, Tang LL, Mao YP, Chen L, Li WF,

Sun Y, Liu LZ, Li L, Lin AH and Ma J: Baseline serum lactate

dehydrogenase levels for patients treated with Intensity-modulated

radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A predictor of poor

prognosis and subsequent liver metastasis. Int J Radiat.

82:e359–e365. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mi S, Gong L and Sui Z: Friend or Foe? An

unrecognized role of uric acid in cancer development and the

potential anticancer effects of uric Acid-Lowering drugs. J Cancer.

11:5236–5244. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wu L, Yang W, Zhang Y, Du X, Jin N, Chen

W, Li H, Zhang S and Xie B: Elevated serum uric acid is associated

with poor survival in advanced HCC patients and febuxostat improves

prognosis in HCC Rats. Front Pharmacol. 12(778890)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Dai XY, He QS, Jing Z and Yuan JQ: Serum

uric acid levels and risk of kidney cancer incidence and mortality:

A prospective cohort study. Cancer Med. 9:5655–5661.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Feng Y, Fu M, Guan X, Wang C, Yuan F, Bai

Y, Meng H, Li G, Wei W, Li H, et al: Uric acid mediated the

association between BMI and postmenopausal breast cancer incidence:

A bidirectional mendelian randomization analysis and prospective

cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

12(742411)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Becker BF: Towards the physiological

function of uric acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 14:615–631.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Mi N, Huang J, Huang C, Lin Y, He Q, Wang

H, Yang M, Lu Y, Lawer AL, Yue P, et al: High serum uric acid may

associate with the increased risk of colorectal cancer in females:

A prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 150:263–272.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yiu A, Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Holmberg

L, Malmström H, Lambe M, Hammar N, Walldius G, Jungner I,

Wulaningsih W, et al: Circulating uric acid levels and subsequent

development of cancer in 493,281 individuals: Findings from the

AMORIS Study. Oncotarget. 8:42332–42342. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Taghizadeh N, Vonk JM and Boezen HM: Serum

uric acid levels and cancer mortality risk among males in a large

general Population-based cohort study. Cancer Causes Control.

25:1075–1080. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Deng Z, Gu Y, Hou X, Zhang L, Bao Y, Hu C

and Jia W: Association between uric acid, cancer incidence and

mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: Shanghai diabetes

registry study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 32:325–332. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Juraschek SP, Tunstall-Pedoe H and

Woodward M: Serum uric acid and the risk of mortality during 23

years follow-up in the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort Study.

Atherosclerosis. 233:623–629. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kobylecki CJ, Afzal S and Nordestgaard BG:

Plasma urate, cancer incidence, and All-cause mortality: A

mendelian randomization study. Clin Chem. 63:1151–1160.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kuo CF, Luo SF, See LC, Chou IJ, Fang YF

and Yu KH: Increased risk of cancer among gout patients: A

nationwide population study. J Bone Spine. 79:375–378.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Du XJ, Chen L, Li WF, Tang LL, Mao YP, Guo

R, Sun Y, Lin AH and Ma J: Use of pretreatment serum uric acid

level to predict metastasis in locally advanced nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. Head Neck. 39:492–497. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Hsueh CY, Shao M, Cao W, Li S and Zhou L:

Pretreatment serum uric acid as an efficient predictor of prognosis

in men with laryngeal squamous cell cancer: A retrospective cohort

study. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019(1821969)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Fini MA, Elias A, Johnson RJ and Wright

RM: Contribution of uric acid to cancer risk, recurrence, and

mortality. Clin Transl Med. 1(16)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Toyokuni S: Oxidative stress as an iceberg

in carcinogenesis and cancer biology. Arch Biochem Biophys.

595:46–49. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kim AW, Batus M, Myint R, Fidler MJ, Basu

S, Bonomi P, Faber LP, Wightman SC, Warren WH, McIntire M, et al:

Prognostic value of xanthine oxidoreductase expression in patients

with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 71:186–190.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Selcukbiricik F, Kanbay M, Solak Y, Bilici

A, Kanıtez M, Balık E and Mandel NM: Serum uric acid as a surrogate

marker of favorable response to bevacizumab treatment in patients

with metastatic colon cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 18:1082–1087.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Song Y, Tang L, Han J, Gao Y, Tang B, Shao

M, Yuan W, Ge W, Huang X, Yao T, et al: Uric acid provides

protective role in red blood cells by antioxidant defense: A

hypothetical analysis. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2019(3435174)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Black CN, Bot M, Scheffer PG, Snieder H

and Penninx B: Uric acid in major depressive and anxiety disorders.

J Affect Disord. 225:684–690. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E and

Hochstein P: Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans

against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: A hypothesis.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 78:6858–6862. 1981.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Dziaman T, Banaszkiewicz Z, Roszkowski K,

Gackowski D, Wisniewska E, Rozalski R, Foksinski M, Siomek A,

Speina E, Winczura A, et al: 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and uric acid

as efficient predictors of survival in colon cancer patients. Int J

Cancer. 134:376–383. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Brook I: Early side effects of radiation

treatment for head and neck cancer. Cancer Radiother. 25:507–513.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Dasari S and Tchounwou PB: Cisplatin in

cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol.

740:364–378. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|