Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents a pressing global

health burden. Contemporary CRC management adopts a multimodal

approach integrating surgical resection, chemotherapy,

radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and complementary modalities such as

traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (1). Surgical intervention remains the

cornerstone for localized disease, while systemic therapy is

predominantly based on chemotherapy regimens incorporating

fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Radiotherapy plays a

crucial role in the management of rectal cancer, particularly in

the neoadjuvant setting where it reduces local recurrence (3). Recent advances in immunotherapy,

especially for mismatch repair-deficient tumors, have shown

encouraging clinical outcomes (4).

Additionally, TCM and novel nanomedicine approaches are being

increasingly explored as complementary approaches to enhance

treatment efficacy and reduce side effects (5,6).

Despite these diverse treatment options, CRC remains one of the

most common malignancies globally and ranks as the third leading

cause of cancer-related mortality (7). In the United States alone, ~153,020

new CRC cases were projected in 2023, with 52,550 deaths, including

19,550 cases and 3,750 deaths among individuals under 50 years of

age (8). Although regular

screening, surveillance and high-quality treatment can prevent a

substantial proportion of CRC morbidity and mortality (9), recurrence and metastasis remain

frequent. Among patients with metastatic CRC, ~70-75% survive

beyond 1 year, 30-35% remain alive at 3 years, while the 5-year

survival rate falls below 20% (10). Therefore, there is an urgent need

to identify reliable biomarkers that can enable early and accurate

prognostic assessment.

In a variety of solid tumors, both the density and

polarization status of TAMs are strongly associated with patient

prognostic outcomes. In CRC, high infiltration of M1-polarized TAMs

is associated with a favorable prognosis across various disease

stages (11), whereas elevated

levels of M2 TAMs often portend a poorer prognosis, a phenomenon

observed in multiple cancer types, including thyroid, lung, stomach

and breast cancers (12). While

macrophage enrichment is usually linked to adverse tumor outcomes,

this correlation appears to be reversed in CRC (13). Nevertheless, the role of TAMs

within the CRC tumor microenvironment (TME) remains complex, and

some studies have shown that TAMs are associated with poor

prognosis in patients with CRC (14). Several investigations have found

that CD68+ TAMs are predominantly distributed in the CRC

tumor stroma, especially at the invasive front, and that

CD68+ TAMs infiltration at these sites correlates with

improved prognosis in patients with CRC (15). However, TAMs of distinct subtypes

and spatial distributions exert different prognostic significance

in CRC: For instance, infiltration of CD68+ TAMs and

M2-type TAMs is linked to unfavorable outcomes (16). Collectively, TAMs play diverse

roles in the prognosis of CRC, and their number, subtype, and

spatial distribution within the TME, as well as their impact on

patient outcomes, are complex. These findings emphasize the

importance of in-depth studies of TAM properties and the search for

specific TAM markers to inform therapeutic strategies and improve

prognostic assessment.

In recent years, cancer stem cells (CSCs) have been

extensively studied as key drivers underlying core hallmarks of

tumor progression, including distant metastasis, recurrence and

drug resistance (17). CSCs

exhibit long-term self-renewal capacity and metastatic potential

across a variety of malignancies, including CRC (18). In CRC,

CD133+/CD44+ CSCs populations have been shown

to correlate negatively with both disease-free survival (DFS) and

overall survival (OS) (19).

Combined detection of CD133/CD44 expression enhances the

identification of colorectal CSCs (20). The TME engages in complex crosstalk

with CSCs, which are often characterized by immune suppression and

low immunogenicity in CRCs (21).

Furthermore, Luo et al (22) reported that CSCs can recruit TAMs

into the TME and accelerate their polarization into tumor-promoting

phenotypes, whereas TAMs in turn maintain CSC stemness and

construct niches unfavorable to the survival of patients with CSC.

Although the prognostic values of TAMs or CSC markers have been

investigated individually, studies analyzing their combined effects

and synergistic interactions on patient prognosis are scarce. Most

previous studies have examined TAMs or CSC markers in isolation,

failing to capture the prognostic power embedded within their

interplay. Therefore, it was hypothesized that a combined biomarker

panel reflecting this TAM-CSC synergy may provide superior

prognostic stratification compared with individual markers

alone.

In the present study, the expression of key TAM

markers (CD86 for M1-like and CD163 for M2-like phenotypes) and CSC

markers (CD44 and CD133) was simultaneously investigated in a

cohort of patients with CRC. The primary objective of the present

study was to evaluate the prognostic impact of their combined

expression and to determine whether this synergistic biomarker

panel could serve as an independent predictor of survival,

potentially offering a more refined tool for risk assessment in

CRC.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

A total of 71 patients with CRC who underwent

surgical resection from April 2018 to April 2020 at Luoyang Central

Hospital Affiliated with Zhengzhou University (Luoyang, China) were

included in the present study. In addition, 20 adjacent normal

tissue samples were collected as controls. Inclusion criteria were

as follows: i) age ≥18 years; ii) availability of complete clinical

and pathological data; and iii) follow-up duration >6 months.

Exclusion criteria included: i) receipt of neoadjuvant therapy

prior to surgery; ii) presence of other synchronous malignancies;

and iii) incomplete medical records or loss to follow-up.

Clinicopathological parameters, including age, sex, tumor

differentiation, depth of invasion and TNM stage, were obtained

from pathology reports and electronic surgical records. All cases

were histologically confirmed as primary colorectal adenocarcinoma.

Patients were followed up until April 10, 2024. Tissue samples from

these patients were subsequently subjected to immunohistochemical

(IHC) analysis. The study was approved (approval no.

LWLL-2018-03-07-01) by the Institutional Review Board and Human

Ethics Committee of Luoyang Central Hospital Affiliated with

Zhengzhou University. Written informed consent was obtained from

all participants or their legal guardians prior to inclusion in the

study.

IHC

For IHC reactions, tissue specimens were fixed in

10% buffered formalin for 24-48 h, embedded in paraffin, and

sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm. Sections were dewaxed in xylene

and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol. Endogenous

peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating sections in 3%

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 10 min, followed

by microwave heating for 3 min to reduce nonspecific binding

activity. Nonspecific binding sites were further blocked with 5%

bovine serum albumin (Boster Biological Technology) at 37˚C or 30

min. Slides were then incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary

antibodies against CD86 (1:200; cat. no. 26903-1-AP), CD163 (1:200;

cat no. 16646-1-AP), CD44 (1:200; cat no. 15675-1-AP), or CD133

(1:200; cat no. 18470-1-AP; all from Proteintech Group, Inc.).

While CD86 is expressed on various antigen-presenting cells,

including dendritic cells, its expression on TAMs has been well

documented in CRC and serves as a valuable marker for assessing

antitumor immune responses within the TME (23). The current analysis specifically

focused on CD86+ cells within the tumor stroma and their

correlation with clinical outcomes. The next day, slides were

washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and then treated

with a biotin-labeled secondary antibody (cat. no. BA1003; Boster

Biological Technology) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by

treatment with streptavidin-biotin complex. Slides were then washed

and stained with 3,3 -diaminobenzidine (cat. no. AR1022;

Bausch Biotechnology, Inc.), counterstained with hematoxylin,

dehydrated, and sealed with neutral resin. Immunostaining for CD86,

CD163, CD44 and CD133 was quantified after digital scanning under

consistent lighting conditions. IHC staining for all markers was

quantified using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics,

Inc.). The staining intensity was graded on a 0-3 scale by two

independent pathologists, and a final immunoreactivity score (range

0-300) was calculated for each sample by multiplying the intensity

score by the percentage of positive cells (0-100%).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

21.0 (IBM Corp.). Optimal cut-off values for CD86, CD163, CD44 and

CD133 IHC scores were determined using Receiver Operating

Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, with OS as the endpoint.

Cut-off points were selected based on the maximum Youden Index

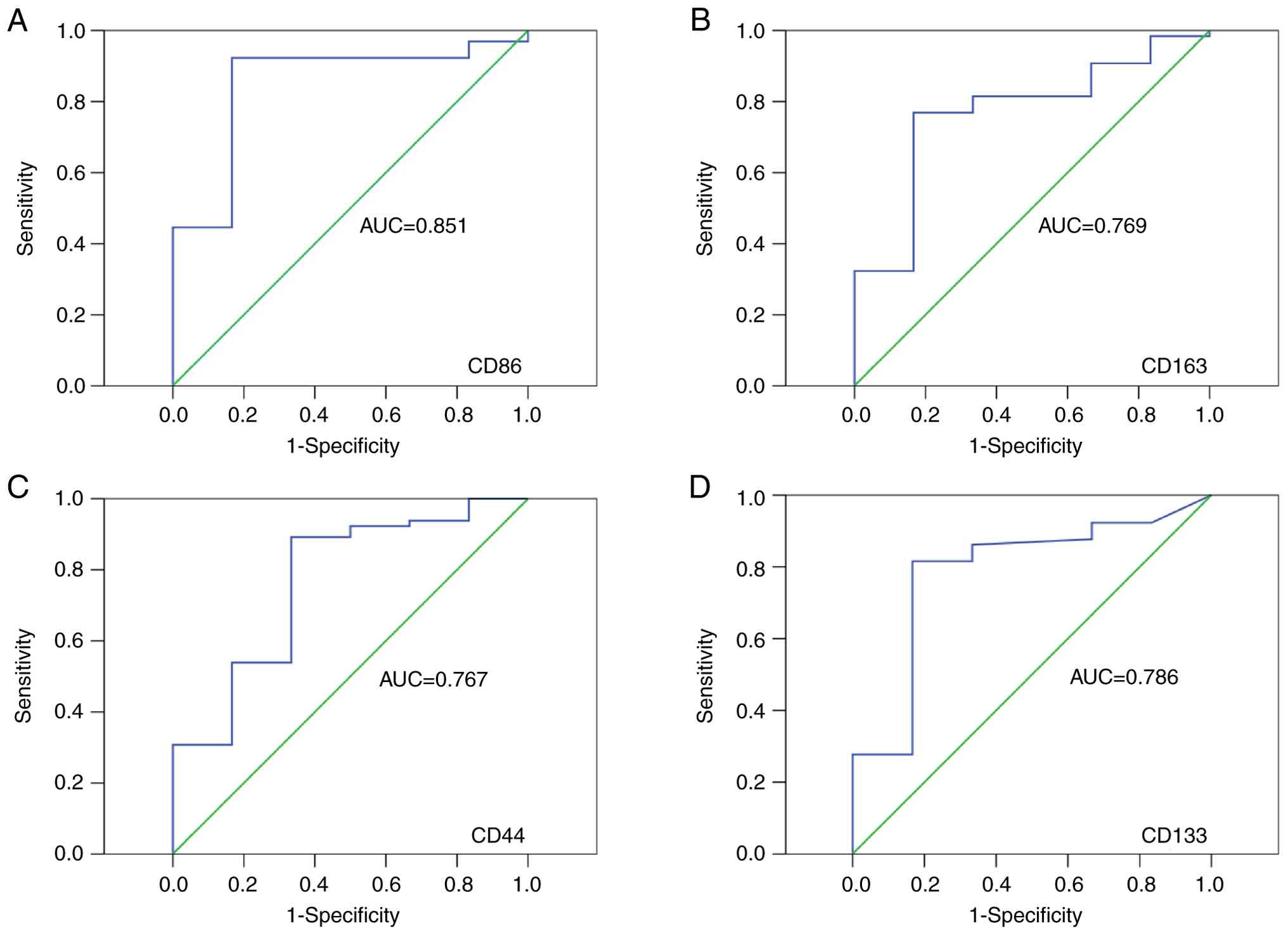

(sensitivity + specificity-1). The area under the curve (AUC)

values were as follows: CD86: 0.851, CD163: 0.769, CD44: 0.767,

CD133: 0.786. Correlations between CD86, CD163, CD44, CD133 and

clinicopathological parameters were analyzed using Pearson s

chi-square test. Survival differences and prognostic factors were

determined using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test.

Correlations among CD86, CD163, CD44 and CD133 were assessed using

Pearson s correlation coefficient with corresponding P-values.

Variable selection for the multivariate Cox regression model was

performed using a stepwise forward method. The Variance Inflation

Factor (VIF) was employed to assess multicollinearity among all

included variables, with all VIF values below 2, indicating no

significant multicollinearity concerns. OS was analyzed using Cox

proportional hazards regression models restricted to variables with

P<0.05 in the univariate analysis. Survival curves for the

relevant factors were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. In all

statistical analyses, P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics and expression

of TAM and CSC biomarkers in human CRC

A total of 71 patients with CRC were included in the

survival analysis cohort, with detailed clinicopathologic

characteristics of patients with CRC after resection listed in

Tables I and II. CD86 was selected as a representative

marker of M1-like TAMs, and CD163 as a representative marker of

M2-like phenotype. Combined detection of multiple markers can

improve the accuracy of CSC identification. In CRC, the use of a

marker panel, including CD133, CD44, CD166, ALDH1 and CD16, has

been shown to reliably identify CSCs (24). To evaluate potential differences in

the expression levels of CD86, CD163, CD44 and CD133 in CRC

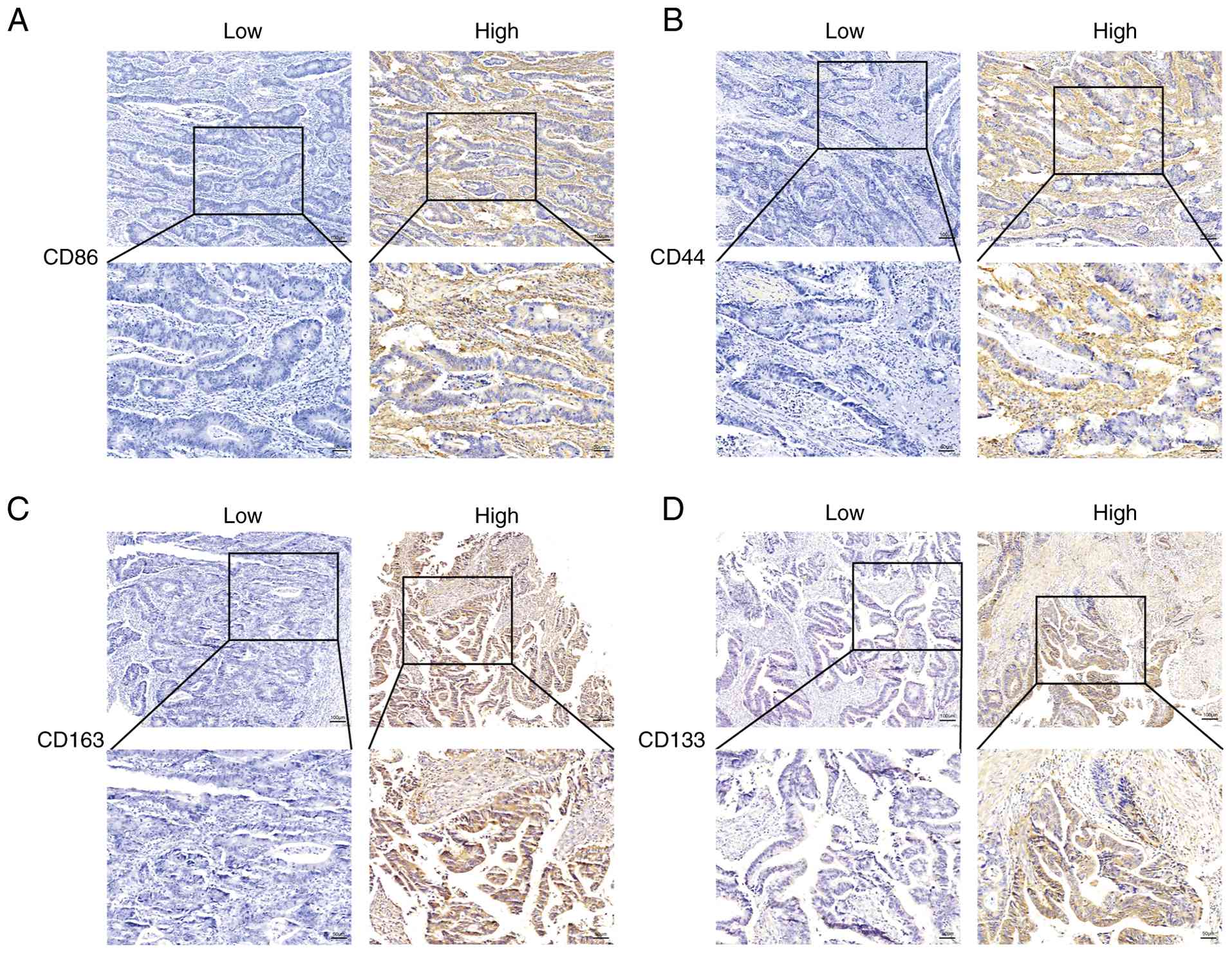

tissues, IHC staining was performed (Fig. 1). Using ROC analysis, optimal

cut-off values for distinguishing high and low levels of these

markers were determined in a cohort of 71 CRC samples (Fig. 2). The established thresholds were

as follows: for CD86, high expression was defined as an IHC score

>93.38, and low expression as <93.38; for CD163, high

expression corresponded to an IHC score >16.13, and low

expression to <16.13; for CD44, high expression was classified

as >5.37, and low as <5.37; and for CD133, high expression

was defined as >1.45, with low expression below this value.

Based on these cut-off values, 61 patients (85.9%) were categorized

as CD86-low and 10 (14.1%) as CD86-high. Among the cohort, 20

patients (28.2%) were designated as CD163-low and 51 (71.8%) as

CD163-high. Likewise, 11 patients (15.5%) were categorized as

CD44-low and 60 (84.5%) as CD44-high. 17 patients (23.9%) were

classified as CD133-low and 54 (76.1%) as CD133-high.

| Table IUnivariate and multivariate Cox

proportional hazards analysis of disease-free survival for patients

with colorectal cancer. |

Table I

Univariate and multivariate Cox

proportional hazards analysis of disease-free survival for patients

with colorectal cancer.

| Variables | Univariate analysis

HR (95% CI) | P-value | Multivariate

analysis HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | | | | |

|

≤60 | 1.000 | 0.688 | | |

|

>60 | 0.902

(0.546-1.492) | | | |

| Sex | | | | |

|

Male | 1.000 | 0.580 | | |

|

Female | 0.869

(0.528-1.430) | | | |

| Tumor location | | | | |

|

Colon | 1.000 | 0.071 | | |

|

Rectal | 1.578

(0.957-2.603) | | | |

| Tumor size, cm | | | | |

|

<3 | 1.000 | 0.003 | | |

|

≥3 | 0.386

(0.198-0.752) | | | |

|

Differentiation | | | | |

|

Well/moderate | 1.000 | 0.077 | | |

|

Poor/undifferentiated | 0.596

(0.334-1.065) | | | |

| T stage | | | | |

|

T1-T2 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.006 |

|

T3-T4 | 0.320

(0.182-0.564) | | 0.444

(0.250-0.789) | |

| TNM stage | | | | |

|

I | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

II | 0.114

(0.038-0.338) | | | |

|

III | 0.295

(0.101-0.866) | | | |

|

IV | 0.425

(0.156-1.153) | | | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | |

|

No | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

Yes | 0.413

(0.250-0.685) | | | |

| Distant

metastasis | | | | |

|

No | 1.000 | 0.016 | | |

|

Yes | 0.296

(0.103-0.857) | | | |

| Preoperative CEA

level (ng/ml) | | | | |

|

≤5 | 1.000 | 0.036 | | |

|

>5 | 0.599

(0.365-0.982) | | | |

| Preoperative CA19-9

level (U/ml) | | | | |

|

<37 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

|

≥37 | 0.370

(0.0.9-0.654) | | 0.314

(0.168-0.588) | |

| CD86 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

High | 4.553

(1.784-11.616) | | | |

| CD163 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

|

High | 0.210

(0.110-0.402) | | 0.259

(0.128-0.522) | |

| CD44 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

High | 0.228

(0.102-0.512) | | | |

| CD133 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

|

High | 0.149

(0.070-0.319) | | 0.203

(0.091-0.457) | |

| Table IIUnivariate and multivariate Cox

proportional hazards analysis of overall survival for patients with

colorectal cancer. |

Table II

Univariate and multivariate Cox

proportional hazards analysis of overall survival for patients with

colorectal cancer.

| Variables | Univariate analysis

HR (95% CI) | P-value | Multivariate

analysis HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | | | | |

|

≤60 | 1.000 | 0.797 | | |

|

>60 | 0.936

(0.566-1.549) | | | |

| Sex | | | | |

|

Male | 1.000 | 0.525 | | |

|

Female | 0.851

(0.518-1.398) | | | |

| Tumor location | | | | |

|

Colon | 1.000 | 0.076 | | |

|

Rectal | 0.637

(0.386-1.052) | | | |

| Tumor size, cm | | | | |

|

<3 | 1.000 | 0.002 | | |

|

≥3 | 0.362

(0.184-0.710) | | | |

|

Differentiation | | | | |

|

Well/moderate | 1.000 | 0.057 | | |

|

Poor/undifferentiated | 0.573

(0.320-1.024) | | | |

| T stage | | | | |

|

T1-T2 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.003 |

|

T3-T4 | 0.305

(0.173-0.541) | | 0.420

(0.236-0.748) | |

| TNM stage | | | | |

|

I | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

II | 0.115

(0.039-0.341) | | | |

|

III | 0.327

(0.112-0.954) | | | |

|

IV | 0.444

(0.164-1.203) | | | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | |

|

No | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

Yes | 0.407

(0.244-0.677) | | | |

| Distant

metastasis | | | | |

|

No | 1.000 | 0.023 | | |

|

Yes | 0.316

(0.110-0.911) | | | |

| Preoperative CEA

level (ng/ml) | | | | |

|

≤5 | 1.000 | 0.043 | | |

|

>5 | 0.609

(0.370-1.001) | | | |

| Preoperative CA19-9

level (U/ml) | | | | |

|

<37 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

|

≥37 | 0.379

(0.215-0.670) | | 0.333

(0.179-0.618) | |

| CD86 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

High | 4.437

(1.751-11.242) | | | |

| CD163 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

|

High | 0.212

(0.111-0.404) | | 0.274

(0.136-0.549) | |

| CD44 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | | |

|

High | 0.208

(0.092-0.471) | | | |

| CD133 protein

expression | | | | |

|

Low | 1.000 | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

|

High | 0.126

(0.054-0.290) | | 0.177

(0.074-0.426) | |

TAM and CSC biomarkers in relation to

clinicopathological characteristics in CRC

The expression of TAM-associated biomarkers CD86 and

CD163, as well as the CSC-associated biomarkers CD44 and CD133,

showed significant associations with a variety of clinicopathologic

characteristics in CRC (Table

III). Elevated CD86 expression was significantly correlated

with smaller tumor size (P=0.025) and a lower incidence of distant

metastasis (P=0.034). By contrast, patients with high CD163

expression had significantly larger tumors (P=0.027), more advanced

T stage (P=0.006), higher TNM stage (P=0.015), and increased lymph

node metastases (P=0.033). In addition, high CD44 expression was

associated with deeper tumor invasion (T stage, P=0.032), more

advanced TNM stage (P=0.044), and a higher frequency of lymph node

metastasis (P=0.009). Similarly, high CD133 expression was

significantly associated with larger tumor volume (P=0.035),

advanced T-stage (P=0.004), later TNM stage (P=0.009), increased

lymph node metastasis (P=0.041) and higher preoperative

carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA; P=0.009) and CA19-9 levels

(P=0.045).

| Table IIIExpression of CD86, CD163, CD44 and

CD133 protein and clinicopathological parameters in colorectal

cancer tissues. |

Table III

Expression of CD86, CD163, CD44 and

CD133 protein and clinicopathological parameters in colorectal

cancer tissues.

| Variables | CD86 High | Low | P-value | CD163 High | Low | P-value | CD44 High | Low | P-value | CD133 High | Low | P-value |

|---|

| Age | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

≤60 | 5 | 23 | 0.461 | 22 | 6 | 0.308 | 23 | 5 | 0.657 | 19 | 9 | 0.191 |

|

>60 | 5 | 38 | | 29 | 14 | | 37 | 6 | | 35 | 8 | |

| Sex | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

Male | 5 | 34 | 0.735 | 28 | 11 | 0.994 | 33 | 6 | 0.978 | 28 | 11 | 0.353 |

|

Female | 5 | 27 | | 23 | 9 | | 27 | 5 | | 26 | 6 | |

| Tumor location | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

Colon | 5 | 23 | 0.461 | 23 | 5 | 0.119 | 25 | 3 | 0.369 | 23 | 5 | 0.332 |

|

Rectal | 5 | 38 | | 28 | 15 | | 35 | 8 | | 31 | 12 | |

| Tumor size, cm | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

<3 | 5 | 11 | 0.025 | 8 | 8 | 0.027 | 12 | 4 | 0.232 | 9 | 7 | 0.035 |

|

≥3 | 5 | 50 | | 43 | 12 | | 48 | 7 | | 45 | 10 | |

|

Differentiation | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

Well/moderate | 10 | 45 | 0.066 | 37 | 18 | 0.113 | 47 | 8 | 0.682 | 41 | 14 | 0.580 |

|

Poor | 0 | 16 | | 14 | 2 | | 13 | 3 | | 13 | 3 | |

| T stage | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

T1-T2 | 5 | 20 | 0.291 | 13 | 12 | 0.006 | 18 | 7 | 0.032 | 14 | 11 | 0.004 |

|

T3-t4 | 5 | 41 | | 38 | 8 | | 42 | 4 | | 40 | 6 | |

| TNM stage | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

I | 5 | 18 | 0.128 | 11 | 12 | 0.015 | 16 | 7 | 0.044 | 12 | 11 | 0.009 |

|

II | 1 | 14 | | 12 | 3 | | 12 | 3 | | 12 | 3 | |

|

III | 2 | 26 | | 23 | 5 | | 27 | 1 | | 25 | 3 | |

|

IV | 2 | 3 | | 5 | 0 | | 5 | 0 | | 5 | 0 | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

No | 6 | 33 | 0.728 | 24 | 15 | 0.033 | 29 | 10 | 0.009 | 26 | 13 | 0.041 |

|

Yes | 4 | 28 | | 27 | 5 | | 31 | 1 | | 28 | 4 | |

| Distant

metastasis | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

No | 8 | 59 | 0.034 | 47 | 20 | 0.197 | 56 | 11 | 0.378 | 50 | 17 | 0.248 |

|

Yes | 2 | 2 | | 4 | 0 | | 4 | 0 | | 4 | 0 | |

| Preoperative CEA

level (ng/ml) | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

≤5 | 7 | 32 | 0.301 | 25 | 14 | 0.110 | 30 | 9 | 0.051 | 25 | 14 | 0.009 |

|

>5 | 3 | 29 | | 26 | 6 | | 30 | 2 | | 29 | 3 | |

| Preoperative CA19-9

level (U/ml) | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

<37 | 8 | 46 | 0.753 | 37 | 17 | 0.269 | 45 | 9 | 0.626 | 38 | 16 | 0.045 |

|

≥37 | 2 | 15 | | 14 | 3 | | 15 | 2 | | 16 | 1 | |

Correlations between TAM and CSC

biomarker expression

Correlations between TAM- and CSC-associated

proteins are presented in Table

IV. CD86, a TAM biomarker, was negatively correlated with the

CSC biomarkers CD44 (P=0.008, r=-0.286) and CD133 (P=0.016,

r=-0.342). By contrast, CD163, a TAMs biomarker, exhibited a

positive correlation with the CSC biomarkers CD44 (P<0.001,

r=0.549) and CD133 (P<0.001, r=0.529).

| Table IVThe relationship between the

expression of CD86, CD163, CD44 and CD133 protein. |

Table IV

The relationship between the

expression of CD86, CD163, CD44 and CD133 protein.

| | CD86 | CD163 |

|---|

| Characteristic | Low | High | P-value | r | Low | High | P-value | r |

|---|

| CD44 | | | | | | | | |

|

Low | 6 | 5 | 0.001 | -0.286 | 9 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.511 |

|

High | 55 | 5 | | | 11 | 49 | | |

| CD133 | | | | | | | | |

|

Low | 11 | 6 | 0.004 | -0.342 | 12 | 5 | 0.000 | 0.529 |

|

High | 50 | 4 | | | 8 | 46 | | |

Follow-up evaluation and prognostic

impact of TAM and CSC biomarker expression in CRC

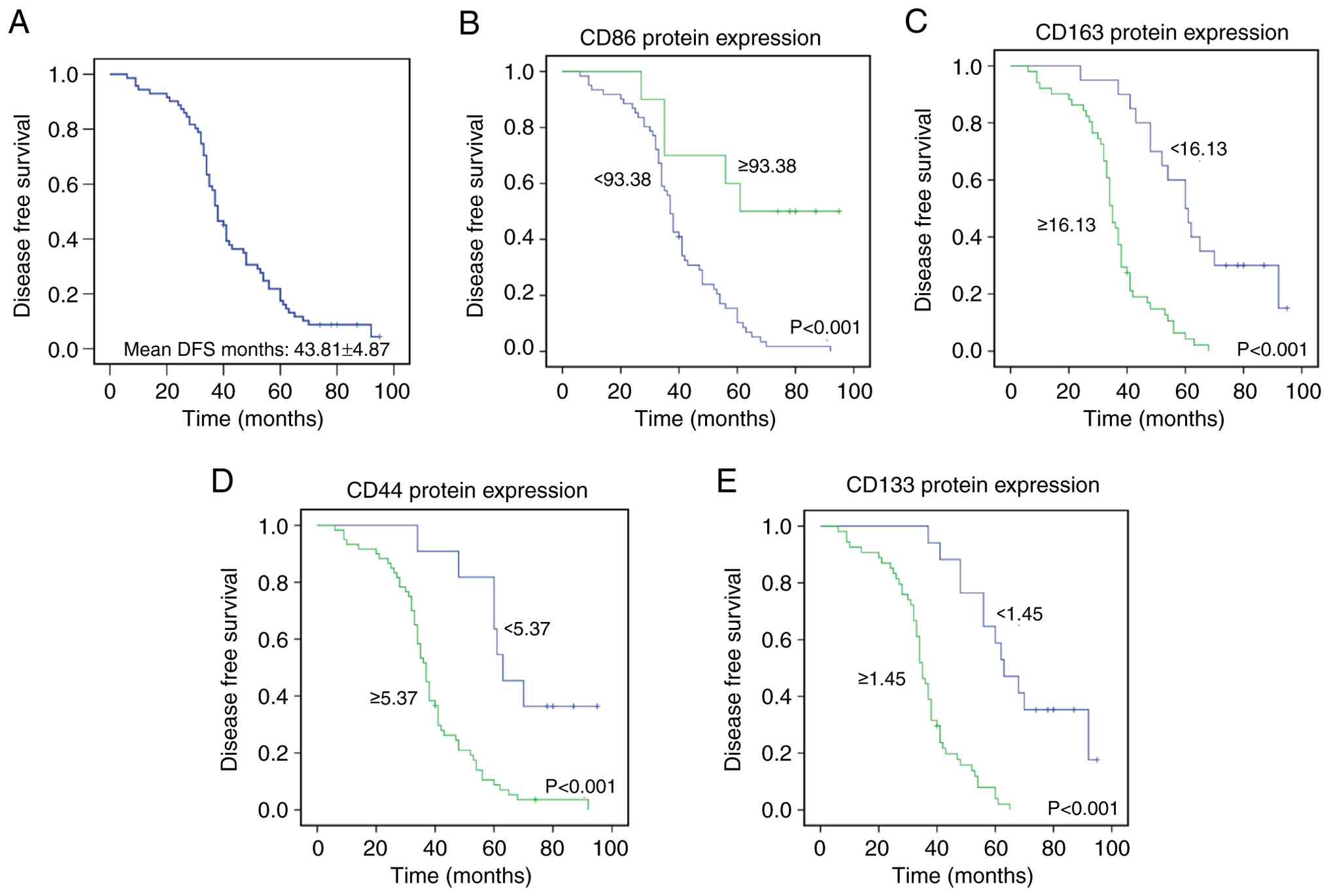

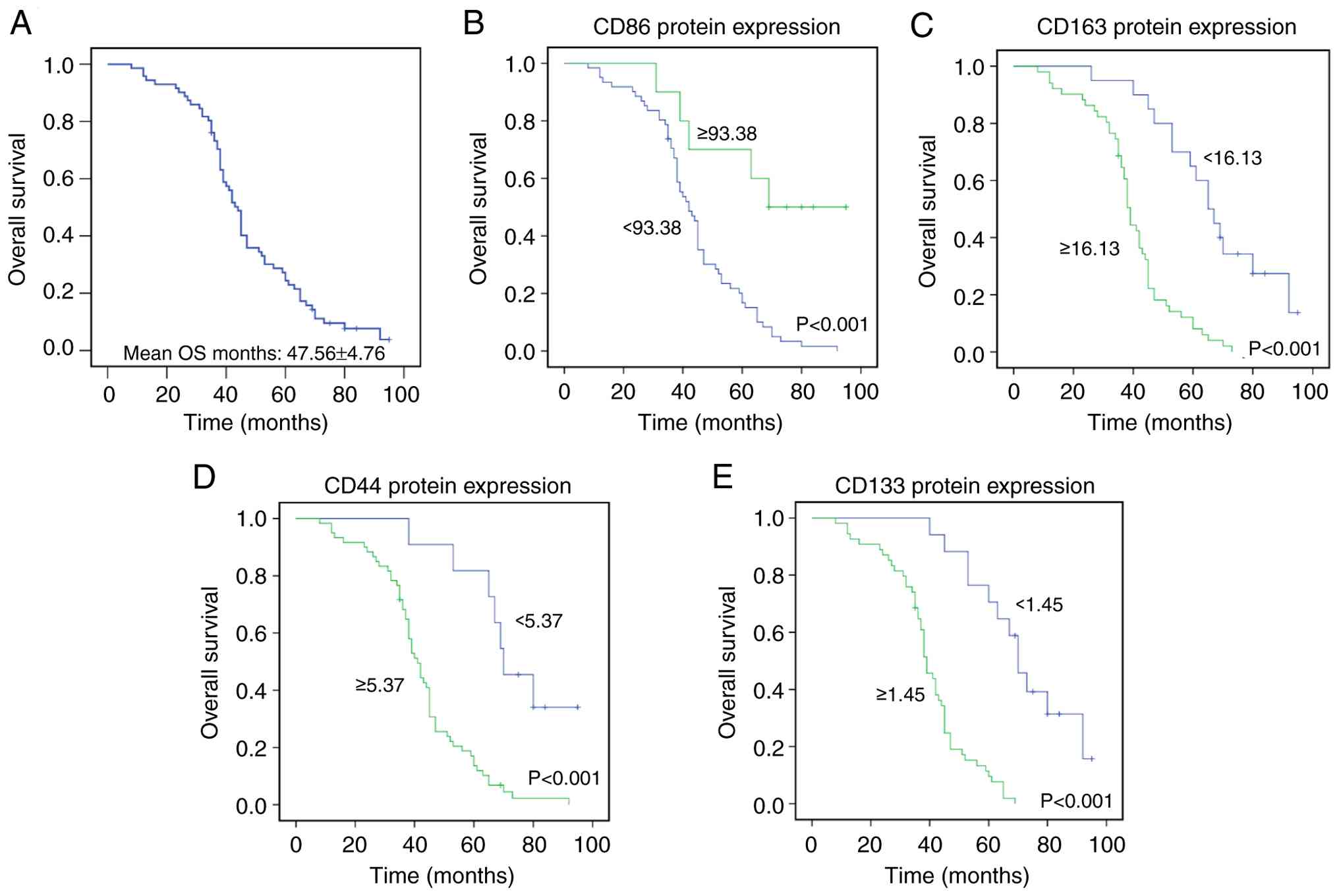

The mean and median DFS of the 71 patients were

43.81±4.87 and 38.00±3.14 months, respectively (Fig. 3A). Mean and median OS were

47.56±4.76 and 44.00±2.97 months, respectively (Fig. 4A). To investigate the prognostic

impact of TAM- and CSC-associated markers, DFS and OS were compared

among patients stratified by the expression levels of CD86, CD163,

CD44 and CD133. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated that

high CD86 expression was significantly associated with prolonged

DFS and OS (P<0.001) (Figs. 3B

and 4B), whereas patients with

high CD163 expression had shorter DFS and OS (P<0.001) (Figs. 3C and 4C). Similarly, elevated CD44 expression

was significantly linked to decreased DFS and OS (P<0.001)

(Figs. 3D and 4D), and high CD133 expression was

significantly associated with shorter DFS and OS (P<0.001)

(Figs. 3E and 4E).

CD163 and CD133 expression, T Stage

and preoperative CA19-9 level as independent prognostic factors for

DFS and OS

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses of DFS and OS were

performed according to tumor size, T stage, TNM stage, lymph node

status, M stage, preoperative CEA and CA19-9 levels, as well as the

expression of CD86, CD163, CD44 and CD133 (Figs. S1 and S2). The results showed that DFS was

significantly associated with tumor size (P=0.003), T stage

(P<0.001), TNM stage (P<0.001), lymph node metastasis

(P<0.001), distant metastasis (P=0.016), preoperative CEA level

(P=0.036), preoperative CA19-9 level (P<0.001), and the

expression of CD86 (P<0.001), CD163 (P<0.001), CD44

(P<0.001) and CD133 (P<0.001). Multivariate Cox regression

analysis identified that CD163 expression (P<0.001), CD133

expression (P<0.001), T stage (P=0.006), and preoperative CA19-9

level (P<0.001) were independent prognostic factors

significantly associated with DFS (Table I). Similarly, OS was significantly

associated with tumor size (P=0.002), T stage (P<0.001), TNM

stage (P<0.001), lymph node metastasis (P<0.001), distant

metastasis (P=0.023), preoperative CEA level (P=0.043),

preoperative CA19-9 level (P<0.001), CD86 expression

(P<0.001), CD163 expression (P<0.001), CD44 expression

(P<0.001) and CD133 expression (P<0.001). For these factors

included in the multivariate Cox analysis, CD163 expression

(P<0.001), CD133 expression (P<0.001), T stage (P=0.003) and

preoperative CA19-9 level (P<0.001) were identified as

independent prognostic factors for OS (Table II).

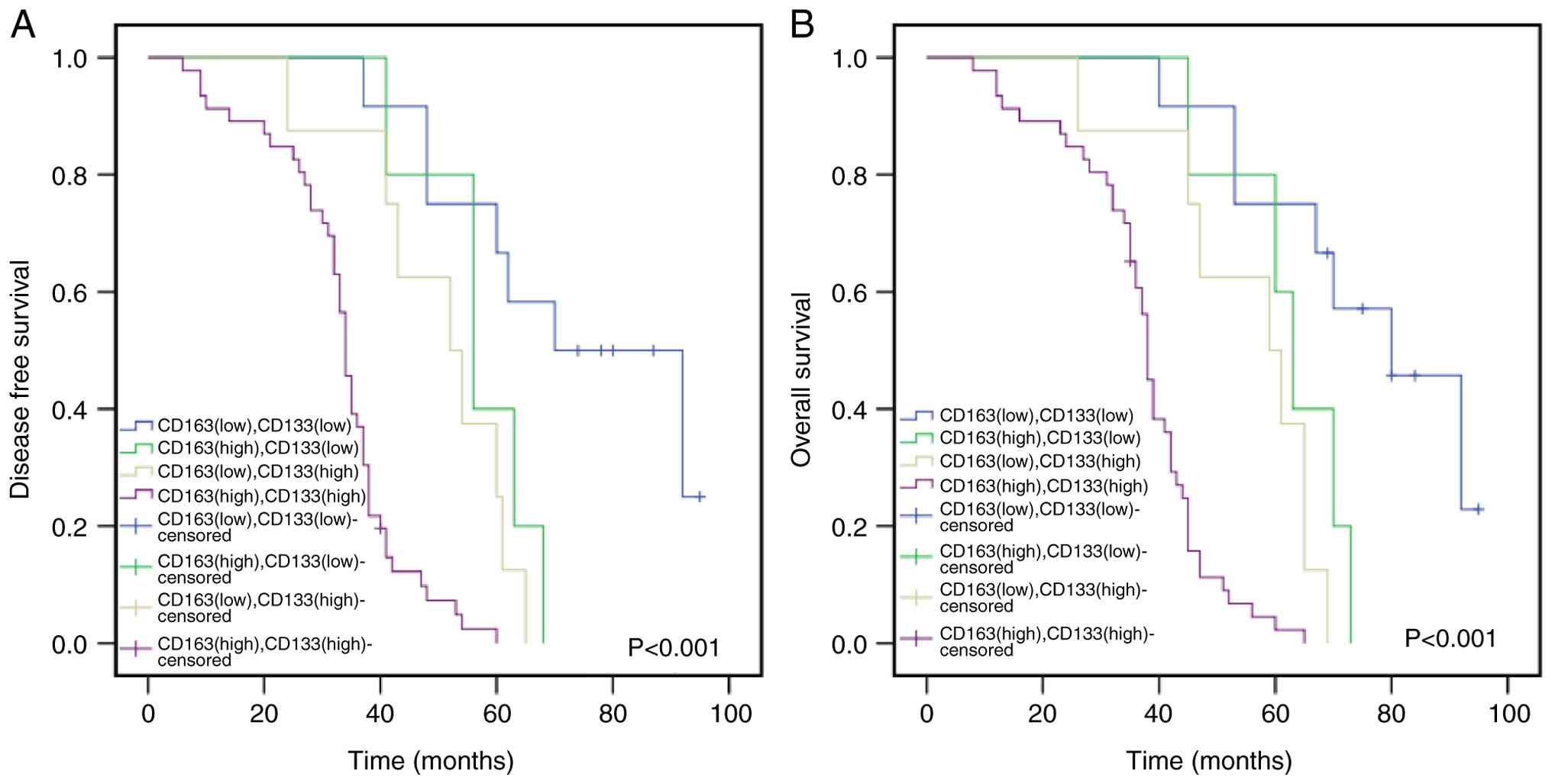

Combined expression of CD163 and CD133

as a prognostic indicator in CRC

Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified

CD163 and CD133 expression as independent prognostic factors for

DFS and OS (Tables I and II). The combined impact of CD163 and

CD133 expression on patient prognosis was therefore evaluated

(Fig. 5). Patients with concurrent

high expression of both markers exhibited significantly shorter DFS

and OS (P<0.001; Fig. 5),

indicating that this combination serves as a robust predictor of

unfavorable prognosis in CRC.

Discussion

CRC ranks as the third most commonly diagnosed

gastrointestinal malignancy worldwide (25). Current treatments for CRC include

surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunomodulatory

approaches (26). Despite these

interventions, nearly 40% of patients develop disease recurrence or

distant metastasis, solidifying CRC s status as the third

leading cause of cancer-related mortality (27). TNM staging, while a major

prognostic factor, has limitations in accurately predicting CRC

patient prognosis (26).

Therefore, it was aimed to identify biomarkers with a stronger

prognostic correlation with CRC. Given that the combined detection

of multiple markers can improve the specificity of CSC and TAM

identification, the joint expression of CSC and TAM biomarkers was

evaluated to determine a panel with improved prognostic

correlation, thereby providing a potential basis for more precise

clinical diagnosis and therapeutic decision-making.

CSCs regulate the TME by recruiting immune cells via

paracrine signaling. For instance, glioma stem cells promote tumor

progression by secreting periostin, recruiting TAMs, and

constructing the TME (28). In

addition, CSCs secrete cytokines, such as TGF-β, IL-10, IL-4 and

IL-13 into the TME, which exert an inhibitory effect on multiple

immune cells (29) and thereby

promote tumor progression. Reciprocally, TAMs regulate CSC stemness

and maintain self-renewal capacity through secretion of cytokines,

chemokines, and participation in complex signaling networks. Key

pathways mediating this bidirectional crosstalk include the

IL-6/STAT3 axis, wherein TAM-derived IL-6 activates STAT3 signaling

in CSCs to promote self-renewal and stemness maintenance (30). Additionally, TGF-β signaling plays

a pivotal role in mediating the bidirectional communication between

TAMs and CSCs. TAM-secreted TGF-β not only enhances CSC stemness

but also induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition, further

contributing to tumor progression and metastasis (31). Other important pathways, such as

NF-κB, can be activated by TAM-derived IL-1 and TNF-α, creating an

inflammatory niche that further supports CSC persistence (32).

The biological significance of these

cytokine-mediated interactions lies in their ability to establish a

sustainable niche that maintains CSC populations, drives tumor

heterogeneity, and confers therapeutic resistance. For instance, in

hepatocellular carcinoma, TAMs can induce STAT3 activation via

IL-6, stimulating further cytokine release and forming a positive

feedback loop that amplifies CSC self-renewal (33). Similarly, in breast cancer, TAMs

have been reported to enhance the stemness characteristics of CSCs

through Ephrin-EphA4 interactions, which in turn stimulate CSCs to

produce inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6 and

IL-8(34).

In summary, a bidirectional communication exists

between CSCs and TAMs. To investigate this relationship, the

protein expression of TAM and CSC biomarkers in CRC tumor tissues

was detected by IHC. It was found that high expression of CD163,

CD44 and CD133 was associated with poor prognosis, while high CD86

expression was correlated with favorable prognosis. Indeed, the

prognostic role of CD86+ TAMs in CRC is complex and

context-dependent. Certain studies suggested that CD86 is

associated with improved survival, and patients with high CD86 gene

expression have higher OS rates than those with low CD86

expression. This indicates that low expression of this marker is

linked to tumor progression and aggressiveness (35), which is in line with the present

findings. While certain studies report CD86 as a general M1 marker

associated with antitumor effects, the present data suggest its

prognostic significance may be context-dependent (36,37).

Discrepancies with previous studies could stem from heterogeneity

in TMEs, differences in antibody clones, or variations in cohort

demographics. By contrast, CD163+ TAMs are known to

drive tumor progression by suppressing antitumor immunity,

enhancing angiogenesis, and promoting metastasis. The association

between CD163+ M2-like TAMs and poor prognosis has been

more consistently reported across various cancer types, including

CRC (38,39). Therefore, Certain studies suggested

that combined analysis of CD86+ TAMs and

CD163+ TAMs appears to be more suitable for determining

relapse and mortality rates (40,41).

In addition, the correlations between TAM and CSC markers,

clinicopathologic parameters and patient prognosis were

investigated. CD86 expression was markedly correlated with tumor

size and distant metastasis, whereas CD163 expression was

significantly correlated with tumor size and T-stage. Additionally,

CD44 and CD133 expression were strongly linked to TNM staging and

lymph node metastasis, respectively. Moreover, both CD163 and CD133

were identified as independent prognostic factors in CRC. The

present analysis revealed significant prognostic value for both

CD86 (M1-like) and CD133, as well as a negative correlation between

them. While the combination of CD86 and CD133 is of interest, the

present study was strategically designed to investigate the

synergistic pro-tumorigenic interaction between TAMs and CSCs. In

this context, the concurrent high expression of CD163 (M2-like

TAMs) and CD133 represents a functionally coherent and biologically

synergistic unit that collectively fosters an immunosuppressive and

pro-stemness TME, leading to the most aggressive disease phenotype.

This is substantiated by the present multivariate Cox regression

analysis, which identified both CD163 and CD133 as the most robust

and independent prognostic factors (P<0.001 for both DFS and

OS). Therefore, prioritizing the

CD163+/CD133+ profile was a deliberate

strategy to most directly test our core hypothesis and to establish

a clinically actionable biomarker for identifying the highest-risk

patient subgroup.

The present analysis revealed significant prognostic

value for both CD86 and CD133, as well as a negative correlation

between them. While the combination of CD86 and CD133 is of

interest, the present study was strategically designed to

investigate the synergistic pro-tumorigenic interaction between

TAMs and CSCs. In this context, the concurrent high expression of

CD163 and CD133 represents a functionally coherent and biologically

synergistic unit that collectively fosters an immunosuppressive and

pro-stemness TME, leading to the most aggressive disease phenotype.

This is substantiated by our multivariate Cox regression analysis,

which identified both CD163 and CD133 as the most robust and

independent prognostic factors (P<0.001 for both DFS and OS).

Therefore, prioritizing the CD163+/CD133+

profile was a deliberate strategy to most directly test our core

hypothesis and to establish a clinically actionable biomarker for

identifying the highest-risk patient subgroup.

Current studies of TAMs and CSCs in CRC remain

relatively limited, typically focusing either on the prognostic

significance of different TAM subtypes or on the relationship

between CSC expression and CRC occurrence and progression (42,43).

By contrast, the present study combines the assessment of TAM and

CSC biomarkers, specifically CD163 and CD133, providing a more

robust prognostic tool than evaluating either marker alone in CRC.

This integrative approach distinguishes the current study from

prior works that primarily focused on single-marker systems. By

assessing TAMs in conjunction with CSCs, the roles of different

subtypes of TAMs and CSCs in CRC were more comprehensively and

accurately explored. Both univariate and multivariate analyses

identified CD163+ TAMs and CD133+ CSCs as

independent prognostic factors for DFS and OS. The prognostic

significance of their combined expression was therefore further

examined, finding that concurrent high levels of CD163 and CD133

were strongly associated with shorter DFS and OS, indicating poor

prognosis. These results suggested that the TAM-CSC functional

unit, rather than either component in isolation, represents a key

determinant of tumor aggressiveness in CRC.

In conclusion, the novel contribution of our

research lies in establishing and validating a combined CD163/CD133

biomarker profile that captures the synergistic interaction between

pro-tumorigenic TAMs and stem-like cancer cells. While TNM staging

provides an anatomical framework, the

CD163+/CD133+ profile directly reflects the

pro-tumorigenic and treatment-resistant potential of the TME. This

dual-marker panel identifies a high-risk patient subgroup with

significantly shorter DFS and OS, thereby significantly improving

the accuracy of prognostic predictions in patients with CRC. These

findings carry important clinical implications for developing more

effective prognostic assessment tools and personalized treatment

strategies. Future research should focus on validating these

biomarkers in larger, multicenter cohorts and exploring targeted

therapies that disrupt the TAM-CSC interaction axis to improve

patient outcomes. Furthermore, this approach holds promise for

predicting responses to both conventional chemotherapy and emerging

immunotherapies, potentially guiding more effective, personalized

treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing

DFS for clinicopathologic factors in CRC. (A) Tumor size. (B)

T-stage. (C) TNM stage. (D) Lymph nodes status. (E) M-stage. (F)

Preoperative CEA level. (G) Preoperative CA19-9 level. P-values

were derived by log-rank test. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing

the influence of clinicopathological factors on colorectal cancer.

(A) T stage. (B) Tumor size. (C) TNM stage. (D) Lymph node status.

(E) M-stage. (F) Preoperative CEA level. (G) Preoperative CA19-9

level. P-values were obtained by log-rank test. CEA,

carcinoembryonic antigen.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81803780), the Natural

Science Foundation of Jiangsu (grant no. BK20180928) and the

Science and Technology Tackling Project of Henan (grant no.

232102310131).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

YK supervised the study and wrote the original

draft. YunW proposed the research concept and designed the research

plan. BH managed the planning and execution of the research

activities. YuqW collected and interpretated data. RY developed

methodology and validated data. HT and FG conducted investigation

and data validation, and prepared figures and tables. YK and YunW

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors wrote,

reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board and Human Ethics Committee of Luoyang Central Hospital

Affiliated with Zhengzhou University (approval no.

LWLL-2018-03-07-01; Luoyang, China). All participants or their

legal guardians signed an informed consent form.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wang F, Chen G, Zhang Z, Yuan Y, Wang Y,

Gao YH, Sheng W, Wang Z, Li X, Yuan X, et al: The Chinese society

of clinical oncology (CSCO): Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis

and treatment of colorectal cancer, 2024 update. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 45:332–379. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hao VDT, Tri PM, My DT, Anh LT, Trung LV,

Bac NH and Vuong NL: FOLFOXIRI for first-line treatment of

unresectable colorectal cancer with liver metastases in a

resource-limited setting. J Gastrointest Cancer.

56(12)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sebag-Montefiore D, Stephens RJ, Steele R,

Monson J, Grieve R, Khanna S, Quirke P, Couture J, de Metz C, Myint

AS, et al: Preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative

chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer (MRC CR07 and

NCIC-CTG C016): A multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet.

373:811–820. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Xiao BY, Zhang X, Cao TY, Li DD, Jiang W,

Kong LH, Tang JH, Han K, Zhang CZ, Mei WJ, et al: Neoadjuvant

immunotherapy leads to major response and low recurrence in

localized mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr

Cancer Netw. 21:60–66. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Guo KC, Wang ZZ and Su XQ: Chinese

medicine in colorectal cancer treatment: From potential targets and

mechanisms to clinical application. Chin J Integr Med: Sep 27, 2024

(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

6

|

Jiang Y, Wang C, Zu C, Rong X, Yu Q and

Jiang J: Synergistic potential of nanomedicine in prostate cancer

immunotherapy: Breakthroughs and prospects. Int J Nanomedicine.

19:9459–9486. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA

and Jemal A: Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin.

73:233–254. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Winawer SJ and Zauber AG: The advanced

adenoma as the primary target of screening. Gastrointest Endosc

Clin N Am. 12:1–9. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Biller LH and Schrag D: Diagnosis and

treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A review. JAMA.

325:669–685. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, Rutegård J,

Öberg Å, Oldenborg PA and Palmqvist R: The distribution of

macrophages with a M1 or M2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and

the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS One.

7(e47045)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Khan SU, Khan MU, Din MA, Khan IM, Khan

MI, Bungau S and Hassan SSU: Reprogramming tumor-associated

macrophages as a unique approach to target tumor immunotherapy.

Front Immunol. 14(1166487)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bruni D, Angell HK and Galon J: The immune

contexture and Immunoscore in cancer prognosis and therapeutic

efficacy. Nat Rev Cancer. 20:662–680. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wang H, Tian T and Zhang J:

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in colorectal cancer (CRC):

From mechanism to therapy and prognosis. Int J Mol Sci.

22(8470)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Li J, Li L, Li Y, Long Y, Zhao Q, Ouyang

Y, Bao W and Gong K: Tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and

prognosis in colorectal cancer: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 35:1203–1210. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wei C, Yang C, Wang S, Shi D, Zhang C, Lin

X, Liu Q, Dou R and Xiong B: Crosstalk between cancer cells and

tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal

circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol

Cancer. 18(64)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Massague J and Ganesh K:

Metastasis-initiating cells and ecosystems. Cancer Discov.

11:971–994. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Gao W, Chen L, Ma Z, Du Z, Zhao Z, Hu Z

and Li Q: Isolation and phenotypic characterization of colorectal

cancer stem cells with organ-specific metastatic potential.

Gastroenterology. 145:636–646. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Fekir K, Dubois-Pot-Schneider H, Désert R,

Daniel Y, Glaise D, Rauch C, Morel F, Fromenty B, Musso O, Cabillic

F and Corlu A: Retrodifferentiation of human tumor hepatocytes to

stem cells leads to metabolic reprogramming and chemoresistance.

Cancer Res. 79:1869–1883. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Nagata T, Sakakura C, Komiyama S,

Miyashita A, Nishio M, Murayama Y, Komatsu S, Shiozaki A, Kuriu Y,

Ikoma H, et al: Expression of cancer stem cell markers CD133 and

CD44 in locoregional recurrence of rectal cancer. Anticancer Res.

31:495–500. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Miranda A, Hamilton PT, Zhang AW, Pattnaik

S, Becht E, Mezheyeuski A, Bruun J, Micke P, de Reynies A and

Nelson BH: Cancer stemness, intratumoral heterogeneity, and immune

response across cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:9020–9029.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Luo S, Yang G, Ye P, Cao N, Chi X, Yang WH

and Yan X: Macrophages are a double-edged sword: Molecular

crosstalk between tumor-associated macrophages and cancer stem

cells. Biomolecules. 12(850)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Sato T, Takagi K, Higuchi M, Abe H,

Kojimahara M, Sagawa M, Tanaki M, Miki Y, Suzuki T and Hojo H:

Immunolocalization of CD80 and CD86 in non-small cell lung

carcinoma: CD80 as a potent prognostic factor. Acta Histochem

Cytochem. 55:25–35. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Murar M and Vaidya A: Cancer stem cell

markers: Premises and prospects. Biomark Med. 9:1331–1342.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Schreuders EH, Ruco A, Rabeneck L, Schoen

RE, Sung JJ, Young GP and Kuipers EJ: Colorectal cancer screening:

A global overview of existing programmes. Gut. 64:1637–1649.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Basak D, Uddin MN and Hancock J: The role

of oxidative stress and its counteractive utility in colorectal

cancer (CRC). Cancers (Basel). 12(3336)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

DeDecker L, Coppedge B, Avelar-Barragan J,

Karnes W and Whiteson K: Microbiome distinctions between the CRC

carcinogenic pathways. Gut Microbes. 13(1854641)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhou W, Ke SQ, Huang Z, Flavahan W, Fang

X, Paul J, Wu L, Sloan AE, McLendon RE, Li X, et al: Periostin

secreted by glioblastoma stem cells recruits M2 tumour-associated

macrophages and promotes malignant growth. Nat Cell Biol.

17:170–182. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Clara JA, Monge C, Yang Y and Takebe N:

Targeting signalling pathways and the immune microenvironment of

cancer stem cells-a clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

17:204–232. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Xu J, Lin H, Wu G, Zhu M and Li M: .:

IL-6/STAT3 is a promising therapeutic target for hepatocellular

carcinoma. Front Oncol. 11(760971)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Fasano M, Pirozzi M, Miceli CC, Cocule M,

Caraglia M, Boccellino M, Vitale P, De Falco V, Farese S, Zotta A,

et al: TGF-β modulated pathways in colorectal cancer: New potential

therapeutic opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 25(7400)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Cornice J, Verzella D, Arboretto P,

Vecchiotti D, Capece D, Zazzeroni F and Franzoso G: NF-κB:

Governing macrophages in cancer. Genes (Basel).

15(197)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, Vatan L,

Sadovskaya A, Ludema G, Simeone DM, Zou W and Welling TH:

Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via

STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem

cells. Gastroenterology. 147:1393–1404. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lu H, Clauser KR, Tam WL, Fröse J, Ye X,

Eaton EN, Reinhardt F, Donnenberg VS, Bhargava R, Carr SA and

Weinberg RA: A breast cancer stem cell niche supported by

juxtacrine signalling from monocytes and macrophages. Nat Cell

Biol. 16:1105–1117. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Aytekin EC, Unal B, Bassorgun CI and Ozkan

O: Clinicopathologic evaluation of CD80, CD86, and PD-L1

expressions with immunohistochemical methods in malignant melanoma

patients. Turk Patoloji Derg. 40:16–26. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kinouchi M, Miura K, Mizoi T, Ishida K,

Fujibuchi W, Ando T, Yazaki N, Saito K, Shiiba K and Sasaki I:

Infiltration of CD14-positive macrophages at the invasive front

indicates a favorable prognosis in colorectal cancer patients with

lymph node metastasis. Hepatogastroenterology. 58:352–358.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Beider K, Bitner H, Leiba M, Gutwein O,

Koren-Michowitz M, Ostrovsky O, Abraham M, Wald H, Galun E, Peled A

and Nagler A: Multiple myeloma cells recruit tumor-supportive

macrophages through the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and promote their

polarization toward the M2 phenotype. Oncotarget. 5:11283–11296.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Jääskeläinen MM, Tumelius R, Hämäläinen K,

Rilla K, Oikari S, Rönkä A, Selander T, Mannermaa A, Tiainen S and

Auvinen P: High numbers of CD163+tumor-associated macrophages

predict poor prognosis in HER2+breast cancer. Cancers (Basel).

16(634)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Molina OE, LaRue H, Simonyan D, Hovington

H, Têtu B, Fradet V, Lacombe L, Toren P, Bergeron A and Fradet Y:

High infiltration of CD209+ dendritic cells and CD163+ macrophages

in the peritumor area of prostate cancer is predictive of late

adverse outcomes. Front Immunol. 14(1205266)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Xu G, Jiang L, Ye C, Qin G, Luo Z, Mo Y

and Chen J: The ratio of CD86+/CD163+macrophages predicts

postoperative recurrence in stage II-III colorectal cancer. Front

Immunol. 12(724429)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Liu J, Deng Y, Liu Z, Li X, Zhang M, Yu X,

Liu T, Chen K and Li Z: Identification of genes associated with

prognosis and immunotherapy prediction in triple-negative breast

cancer via M1/M2 macrophage ratio. Medicina (Kaunas).

59(1285)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Fattahi F, Zanjani LS, Vafaei S, Shams ZH,

Kiani J, Naseri M, Gheytanchi E and Madjd Z: Expressions of TWIST1

and CD105 markers in colorectal cancer patients and their

association with metastatic potential and prognosis. Diagn Pathol.

16(26)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Inagaki K, Kunisho S, Takigawa H, Yuge R,

Oka S, Tanaka S, Shimamoto F, Chayama K and Kitadai Y: Role of

tumor-associated macrophages at the invasive front in human

colorectal cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 112:2692–2704.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|