Introduction

A report by the World Health Organization (WHO), as

well as previous studies by the have revealed that at least 2.2

billion individuals globally, primarily due to population growth,

suffer from vision impairment or blindness, with a great proportion

of these individuals being women. Notably, a number of these

impairments are age-related, necessitating focused attention on

women of reproductive age (1-3). In

Europe alone, ~2.4% of women within this demographic are

significantly visually impaired, underscoring an urgent need for

specialized healthcare services tailored to their unique needs

(4).

Historically, societal perceptions have marginalized

the sexual and reproductive desires of individuals with

disabilities, often labeling these aspirations as non-existent or

perilous. Yet, the inherent right to parenthood persists

universally, advocating that all individuals, irrespective of

disabilities, deserve to experience this fundamental aspect of

human development (3,5). Despite considerable research being made

into the general lack of awareness among healthcare professionals

(HCPs) about the specific needs of this population group, studies

focusing directly on women who are visually impaired remain

limited. This knowledge gap perpetuates social stigma and results

in suboptimal health counseling for these women, impacting their

overall quality of life (5-9).

Despite the introduction of legal protections for

individuals with disabilities in the 20th century, practical

barriers still obstruct their access to healthcare services

(10,11). Transportation to medical facilities

and inappropriate behavior from healthcare providers are common

daily challenges. Studies have indicated that women with visual

impairments are more likely to face complications during pregnancy

and have adverse birth outcomes (5,12-15).

However, customizing childbirth preparation classes to meet their

individual needs can significantly mitigate these risks. Providing

psychosocial support and personalized sessions are essential steps

toward fulfilling this goal (6,16).

It is evident that the existing perinatal care

systems are ill-equipped to adequately support women who are

visually impaired (6,8,14).

Public health objectives emphasize improving health outcomes across

all populations, highlighting the necessity of accessible

information and inclusive services to diminish health disparities

and enhance life quality for these women (8,17).

Despite their legal right to motherhood, visually impaired women

often face undue prejudice, viewed as incapable of experiencing

normal childbirth or fulfilling maternal roles effectively

(3,16).

The Royal College of Midwives emphasizes the

importance of supporting mothers with disabilities by adhering to

established guidelines [https://www.rcm.org.uk/media/4521/rcm_position-statement_multiple-disadvantaged_draft_final.pdf].

Midwives must not only be aware of their responsibilities, but must

also be equipped to provide adaptable, innovative and empathetic

care, tailored to the unique challenges faced by these women,

thereby ensuring positive experiences throughout pregnancy,

childbirth and motherhood (18).

In recent years, numerous studies have highlighted

the critical need for maternal care that inclusively supports all

women, particularly those from vulnerable groups (16-18).

As such, it is paramount that Greece intensifies its efforts to

scrutinize and enhance the level of care provided to its

marginalized populations through detailed assessments such as

questionnaires, interviews and case studies. Currently there are a

handful of studies exploring perinatal care and birth experiences

in women with visual impairment (6,16).

Notably, while a number of these impairments are due to conditions,

such as unmet refractive error or cataract, which are generally

reversible, the present study focuses on the subset of visual

impairments that are not easily corrected and persist into or arise

during reproductive age. These include conditions, such as

glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa and congenital vision disorders. To

the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first study

from Greece to investigate these aspects in women with visual

impairment. The present study aimed to highlight the importance of

developing guidelines that improve healthcare quality, the of

proficiency healthcare providers and the availability of adequate

facilities, as derived from the antenatal population with any

degree of visual impairment experiences during pregnancy,

childbirth and puerperium.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

The present descriptive retrospective study was

conducted between January and June, 2021, focusing on women in

Greece with visual impairments who gave birth after 2005. The

cohort consisted of 22 women who were either totally or partially

blind, mostly from Athens. Participants ranged in age from 29 to 44

years, with a median age of 32 years.

Inclusion criteria

The present study used the following inclusion

criteria for the recruitment of patients: i) Age: Women had to have

an age ≥18; ii) pregnancy period: Women who were pregnant between

the years 2005 and 2021 were included; iii) visual impairment:

Women with documented visual impairment, as defined by best

corrected visual acuity (BCVA), electroretinogram (ERG) or impaired

visual fields were included; iv) medical documentation:

Participants had to provide medical documentation confirming their

visual impairment diagnosis from a certified ophthalmologist; v)

support from Greek organizations: Women who had been supported by a

Greek organization for individuals with visual impairment (e.g.,

National Federation for the Blind) for a minimum of 6 months were

included; vi) residency: Women had to be residing in Greece at the

time of their pregnancy; and vii) consent: Women had to be willing

and able to provide informed consent to participate in the

study.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria used herein were the

following: i) A lack of medical documentation: Women who could not

provide medical documentation confirming their visual impairment

were not included; ii) women with inadequate levels of visual

impairment were excluded; iii) insufficient duration of support:

Women who had not been supported by a Greek organization for

individuals with visual impairment for at least 6 months were

excluded; iv) non-residency: Women who do not reside in Greece or

who were not residing in Greece during their pregnancy.vi)

inability to provide consent: Women who were unable or unwilling to

provide informed consent to participate in the study were not

included.

Recruitment of participants

The study participants were recruited from several

organizations dedicated to supporting individuals with visual

impairments, including the National Federation for the Blind in

Athens (https://www.eoty.gr/the-main-goals-and-activities-of-the-national-federation-of-the-blind-e-o-t),

the Panhellenic Association of the Blind-Regional Association of

the Blind in Western Greece (https://www.pst.gr), the Training & Rehabilitation

Center for the Blind in Thessaloniki (https://keat.gr/?lang=en), ‘Magnites Tifloi’ in Volos

(https://www.maty.gr), the Panhellenic Association

of Parents & Guardians of People with Serious Vision Problems

‘HERA’ (https://amimoni.gr/en/amimoni-2), and the Pancretan

Association of Parents & Friends of Blind and Visually Impaired

Children (https://vivliopoleiopataki.gr/persons/view/detail/persons/54779-pagkritios-sillogos-goneon-ke-filon-pedion-tiflon-i-me-miomeni-orasi).

These organizations played a crucial role in facilitating access to

this uniquely situated group of women, ensuring a representative

sample of the visually impaired population undergoing maternity

experiences in Greece.

Research questionnaire

The research tool was a comprehensive questionnaire

consisting of 53 questions divided into five distinct sections, as

outlined in Data S1 (16-19).

The sections included following: i) Demographical and clinical

characteristics: This section contained 10 questions aimed at

gathering basic and health-related information; ii) pregnancy

period: Comprising 22 questions, this section delved into the

details of the pregnancy experiences of women; iii) childbirth:

This segment included eight questions focused on the labor and

delivery experiences; iv) puerperium period: This section also

included eight questions, addressing the postpartum experiences; v)

health professional and care evaluation: The final five questions

assessed the perceptions and interactions of the participants with

healthcare providers, as well as the quality of obstetric and

gynecological care received.

Participants typically completed the questionnaire

within a period of 20 to 25 min. The collection of data was based

on self-administered electronic questionnaires filled out by the

participants, reflecting their direct experiences. In order to

ensure the comprehensive coverage of the topic, the questionnaire

design drew on previous studies and relevant scientific literature

(14-18).

The survey was administered electronically using

Google Forms, which is compatible with various accessibility tools

commonly used by visually impaired individuals. To ensure that the

questionnaire was fully accessible, it was designed to support

screen readers and text-to-speech software, allowing for the

auditory reading of the questions. Additionally, the questionnaire

was optimized for high contrast and large text settings to cater to

individuals with partial vision.

Participants were informed beforehand about the

available accessibility features and instructions on how to utilize

them effectively were provided. This approach ensured that all

participants, regardless of their level of visual impairment, could

navigate the questionnaire independently and securely.

The survey interface was tested with multiple types

of visual impairment adaptive technologies prior to deployment,

acknowledging the diverse needs of the group of participants. This

pre-testing phase involved participants from the target demographic

who utilized screen readers, braille output devices and

magnification software to provide feedback on the accessibility of

the survey. Adjustments were made based on their inputs to ensure

that the survey was comprehensible and user-friendly for

individuals with varying degrees of visual impairment.

In order to ensure the accuracy and reliability of

the self-administered data collection process, several measures

were implemented, as follows: i) Initial instructions: Participants

received detailed instructions on how to complete the survey using

Google Forms, which included information on using screen readers,

text-to-speech software, and magnification tools. ii) Accessibility

features: The Google Forms questionnaire was designed to be fully

accessible to individuals with visual impairments. This included

compatibility with screen readers, high contrast settings, large

text options and voice input capabilities. iii) Family caregiver

involvement: While the primary goal was for participants to

complete the survey independently, it was acknowledged that some

participants may require assistance. In such cases, family

caregivers were permitted to assist the participants. However, this

assistance was strictly limited to navigating the technology and

reading the questions aloud. Caregivers were instructed not to

influence or input responses to ensure that the data accurately

reflected the experiences and opinions of the participants. iv)

Verification of self-administration: In order to further ensure the

integrity of the data, a section was included in the survey where

participants indicated whether they completed the survey

independently or with assistance. For those who received

assistance, details on the nature of the assistance provided were

requested. v) Pilot testing: Prior to full deployment, the survey

underwent pilot testing with a subset of visually impaired

individuals. This testing aimed to identify any potential

challenges in self-administration and allowed for any necessary

adjustments to be made based on feedback. Participants in the pilot

test confirmed that the accessibility features were adequate for

independent completion. vi) Ethical oversight: The present study

was closely monitored by the Ethics Committee of the University of

West Attica (Athens, Greece), ensuring adherence to the highest

ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all

participants, emphasizing the importance of honest and independent

responses.

Throughout the survey design and implementation,

ethical considerations were paramount throughout the design and

implementation of the survey. Informed consent was obtained from

all participants after providing a detailed explanation of the

purpose and methodology of the study, which included measures to

maintain privacy and data security. The present study received

approval from the Committee of the Midwifery Department of the

University of West Attica and was closely monitored during its

execution by a three-member committee. The protocol number of the

Research Ethics Boards of the University of West Attica was

20/27-09-2019, ensuring adherence to the highest standards of

research ethics and participant confidentiality.

Data analysis and presentation

As the present study was a descriptive study and not

an analytical study, no inferential statistics were used.

Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers (frequency

in percentages).

Results

Demographic and clinical

characteristics

All the demographic and clinical characteristics of

the study participants are presented in Table I. The present study enrolled 22 women

residing in Greece, aged between 29 and >35 years, who consented

to participate in the research. Among these patients, 86.4% (n=19)

were >35 years of age, 9.1% (n=2) were aged 30 to 34 years, and

4.5% (n=1) were between 25 and 29 years of age. The marital status

of the participants varied: 68.2% (n=15) were married, 13.6% (n=3)

were single, 9.1% (n=2) were divorced, 4.5% (n=1) were widowed, and

another 4.5% (n=1) were estranged. Half of the participants (50%,

n=11) had one child. The educational level of the participants was

high, with 54.5% (n=12) having received higher education, and 40.9%

(n=9) were employed, either in the public or private sector or were

self-employed. As regards the annual family income distribution of

the participants, 68.2% (n=15) earned between €7,000 and €20,000,

and 31.8% (n=7) earned above €20,000. Of the 22 participants, 16

(72.7%) resided in urban areas, specifically in Athens, while 6

(27.3%) were from rural areas across Greece. Among the

participants, 15 women (68.2%) received their perinatal care

through public healthcare services, while 7 women (31.8%) utilized

private healthcare services (Table

I).

| Table IClinical and demographic

characteristics of the study population. |

Table I

Clinical and demographic

characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristic | No. of

participants | Percentage |

|---|

| Age range (25-29

years) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Age range (30-34

years) | 2 | 9.1 |

| Age range (>35

years) | 19 | 86.4 |

| Marital status

(married) | 15 | 68.2 |

| Marital status

(single) | 3 | 13.6 |

| Marital status

(divorced) | 2 | 9.1 |

| Marital status

(widowed) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Marital status

(estranged) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Number of children

(one) | 11 | 50.0 |

| Educational level

(higher education) | 12 | 54.5 |

| Employment status

(employed) | 9 | 40.9 |

| Annual family income

(€7,000-€20,000) | 15 | 68.2 |

| Annual family income

(above €20,000) | 7 | 31.8 |

| Residence

(urban-Athens) | 16 | 72.7 |

| Residence

(rural) | 6 | 27.3 |

| Perinatal care type

(public sector) | 15 | 68.2 |

| Perinatal care type

(private sector) | 7 | 31.8 |

| Type of visual

impairment (total blindness) | 14 | 63.6 |

| Type of visual

impairment (partial blindness) | 8 | 36.4 |

| Onset of blindness

(congenital) | 10 | 45.5 |

| Onset of blindness

(later in life) | 12 | 54.5 |

| Retinal

detachment | 4 | 19 |

| Stargardt

disease | 4 | 19 |

| Incorrect handling of

incubator-prematurity | 4 | 19 |

| Glaucoma | 3 | 14 |

| Congenital

cataract | 2 | 9.5 |

| Leber syndrome | 2 | 9.5 |

| Aniridia | 1 | 5 |

| Other | 1 | 5 |

| Husband's

disability (yes) | 13 | 59.1 |

| Husband's

disability (no) | 9 | 40.9 |

| Planned pregnancy

(yes) | 16 | 72.7 |

| Planned pregnancy

(no) | 6 | 27.3 |

| Assisted

reproduction (IVF) | 2 | 9.1 |

| Pregnancy outcome

(miscarriage/abortion) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Pregnancy outcome

(childbirth) | 21 | 95.5 |

| Smoking status

(prior to pregnancy-smoker) | 6 | 27.3 |

| Smoking status

(prior to pregnancy-non-smoker) | 16 | 72.7 |

| Smoking status

(during pregnancy-reduced smoking) | 3 | 13.6 |

| Smoking Status

(during pregnancy-non-smoker) | 19 | 86.4 |

| Alcohol consumption

(before pregnancy-occasional use) | 14 | 63.6 |

| Alcohol consumption

(before pregnancy-no use) | 8 | 36.4 |

| Alcohol consumption

(during pregnancy-occasional use) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Alcohol consumption

(during pregnancy-no use) | 21 | 95.5 |

| Drug use

(none) | 22 | 100.0 |

| Weight change

during pregnancy (5-12 kg gain) | 20 | 90.9 |

| Weight change

during pregnancy (weight loss) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Weight change

during pregnancy (significant gain) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Familial support

(well-supported by husband) | 15 | 68.2 |

| Positive

interactions with midwives (yes) | 18 | 81.8 |

| Prenatal care

explanations (detailed) | 16 | 72.7 |

| Restrictions in

equipment interaction (yes) | 17 | 77.3 |

| Pregnancy

complications (yes) | 3 | 13.6 |

| Pregnancy

complications (no) | 19 | 86.4 |

| Childbirth

preparation classes (positive to neutral) | - | - |

| Gestational age at

birth (>37 weeks) | 16 | 72.7 |

| Mode of delivery

(cesarean section) | 13 | 59.1 |

| Infant birth weight

(<2,500 g) | 6 | 27.3 |

| Infant birth weight

(≥2,500 g) | 16 | 72.7 |

| Emotional

experience (no loneliness/anxiety) | 15 | 68.2 |

| Emotional

experience (loneliness/anxiety) | 7 | 31.8 |

| Smoking status

(puerperium-continued smoking) | 1 | 4.5 |

| Smoking status

(puerperium-abstained) | 21 | 95.5 |

| Alcohol consumption

(puerperium-no use) | 22 | 100.0 |

| Drug use

(puerperium-none) | 22 | 100.0 |

| Familiarization

with maternity room (inadequate) | 13 | 59.1 |

| Recognizing infant

needs (challenges) | 15 | 68.2 |

| Midwives describing

infant expressions (no) | 18 | 81.8 |

| House visits by

midwives (yes) | 5 | 22.7 |

| House visits by

midwives (no) | 17 | 77.3 |

| Desire for more

frequent visits (yes) | 10 | 45.5 |

| Duration of

breastfeeding (1 to 24 months) | 16 | 72.7 |

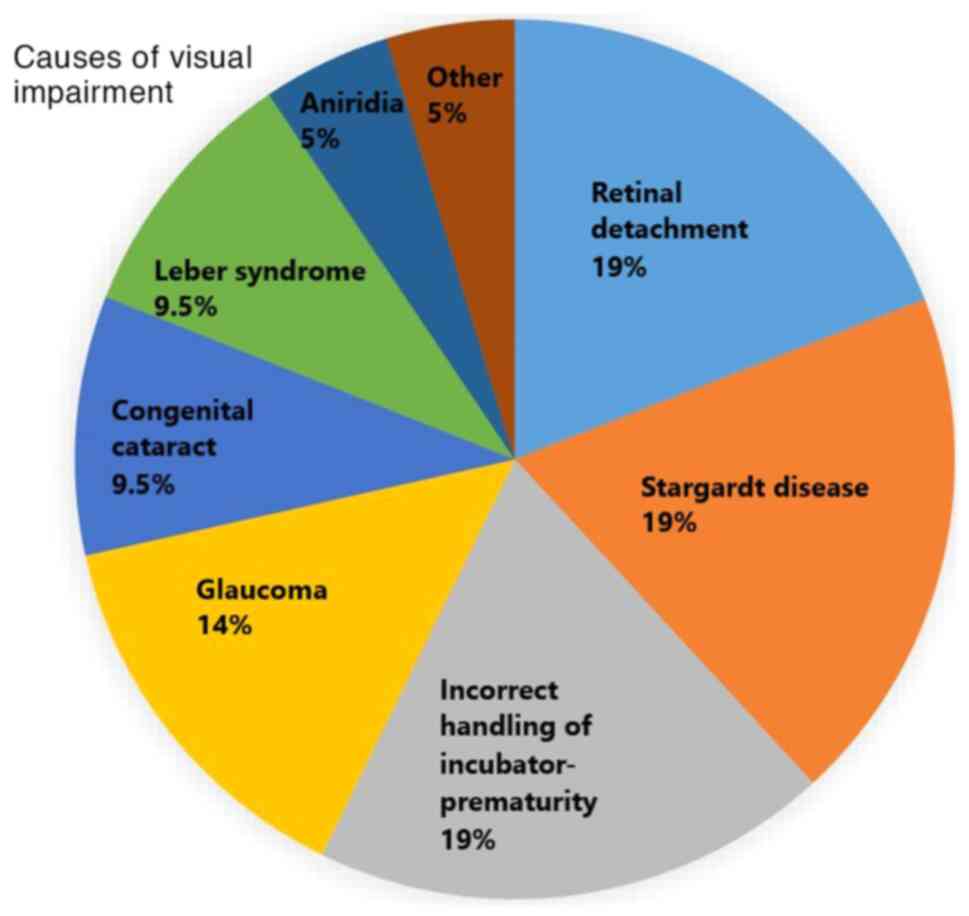

All participants had vision impairments, either

total or partial blindness. Of these, 63.6% (n=14) were totally

blind, and 36.4% (n=8) were partially blind. As regards the onset

of blindness, 45.5% (n=10) were congenitally blind, while 54.5%

(n=12) acquired blindness later in life due to various causes

detailed in Fig. 1. Additionally,

59.1% (n=13) reported that their husbands had a disability,

including blindness (Table I).

Pregnancy and clinical outcomes

The present study cohort consisted of women who had

conceived after 2005, with all initial examinations occurring

during the first trimester. Among these women, 72.7% (n=16) had

planned their pregnancies, and 9.1% (n=2) had utilized assisted

reproduction technologies, such as in vitro fertilization

(IVF). Not all pregnancies resulted in childbirth, with one

instance (4.5%) of miscarriage or abortion reported (Table I).

Prior to pregnancy, 6 (27.3%) of the participants

were smokers, with a reduction during pregnancy where 3

participants continued smoking at reduced rates. Alcohol

consumption was minimal, with 63.6% of participants reporting

occasional use prior to pregnancy and only 1 participant (4.5%)

consuming a glass every 3 months during pregnancy. None of the

participants reported using drugs (Table

I).

The participants experienced various changes in

weight during pregnancy, with 90.9% (n=20) reporting a weight gain

of 5 to 12 kg. However, there were also instances of weight loss

and substantial weight gain.

The survey also highlighted the familial and medical

support received during pregnancy. The majority, 68.2% (n=15) of

the participants, felt well-supported by their husbands, and 81.8%

(n=18) reported positive interactions with midwives who supported

their pregnancy announcements. Concerning prenatal care, 72.7%

(n=16) appreciated the detailed explanations provided by midwives

during routine examinations, although 77.3% (n=17) noted

restrictions in physically interacting with the medical equipment

used during these examinations (Table

I).

While a substantial portion of the participants did

not experience any pregnancy-related complications, 13.6% (n=3) of

the women reported conditions, such as gestational diabetes

mellitus and hypertension.

Childbirth experience

The majority of the women (72.7%, n=16) gave birth

after 37 completed weeks, with a high rate of cesarean section of

59.1% (n=13). In the present study, it was found that 27.3% of the

participants (6 out of 22) reported giving birth to infants with a

low birth weight (<2,500 g). The majority felt respected and

involved in childbirth decisions, and a large proportion (68.2%,

n=15) did not experience loneliness or anxiety at the time of birth

(Table I).

Puerperium period

During the puerperium period, only 1 participant

reported continuing to smoke, albeit minimally at one cigarette

following each breastfeeding session. The remainder of the cohort

abstained from smoking, alcohol consumption and drug use during

this period.

A large portion of participants, 59.1% (n=13),

expressed concerns that midwives did not adequately familiarize

them with the layout of the maternity room. This lack of

orientation contributed to difficulties in navigating the space

effectively. Furthermore, 68.2% (n=15) encountered challenges in

recognizing and responding to the needs of their infants, a

situation exacerbated by 81.8% (n=18) of midwives not describing

the facial expressions of their infants, which would have

facilitated the enhanced maternal understanding and bonding

(Table I).

House visits by midwives post-birth were reported by

22.7% (n=5) of the women. In addition, 45.5% (n=10) of the

participants expressed the desire for more frequent visits to

support activities such as breastfeeding, including these with no

visits. The participants expressed a need for midwives during the

puerperium period, with comments, such as ‘as many times as

necessary’, ‘until I establish breastfeeding’, and specific

requests for guidance on basic caregiving tasks, such as diaper

changes. Additionally, 72.7% (n=16) of the women breastfed their

infants from 1 month up to 24 months, indicating a commitment to

prolonged breastfeeding. From the 3 patients who suffered from

glaucoma, none used teratogenic eyedrops and all breastfed their

infants. Table I summarizes all the

clinical and demographic characteristics of the study

population.

Attitude towards healthcare

professionals and midwifery and gynecological care units

Opinions on the level of care provided by health

professionals varied among the participants: Of the participants,

45.5% (n=10) felt they received the same level of care as women

without visual impairments, while 54.5% (n=12) viewed the care as

humanitarian. However, perceptions about the awareness of

healthcare providers towards the needs of visually impaired women

were mixed, with 50% (n=11) believing that midwives and

gynecologists were sufficiently willing to provide appropriate

care.

Notwithstanding these perceptions, 90.9% (n=20) of

participants identified a substantial gap in the knowledge and

specialization of medical staff regarding perinatal care for

visually impaired women, advocating for enhanced training and

professional development. A unanimous majority of the participants

felt that comprehensive training and lifelong learning for

healthcare providers are essential. They suggested that HCPs should

attend specialized seminars to better understand and cater to the

needs of visually impaired patients.

Participant satisfaction with the attitude of HCPs

varied, with 40.9% (n=9) expressing moderate levels of satisfaction

and 31.8% (n=7) expressing high levels of satisfaction. These

participants appreciated when healthcare providers made efforts to

overcome their lack of knowledge about dealing with disabilities.

Conversely, a few women were dissatisfied with the care received,

highlighting instances of poor communication and neglect that

potentially endangered their health. Notably, no participant rated

the midwifery and gynecological care they received as ‘excellent’,

underscoring a critical area for improvement in the healthcare

system. The attitude towards healthcare professionals and midwifery

and gynecological care units is summarized in Table II.

| Table IIAttitude towards healthcare

professionals and midwifery and gynecological care units. |

Table II

Attitude towards healthcare

professionals and midwifery and gynecological care units.

| Category | No. of

participants | Percentage |

|---|

| Perception of care

quality | | |

| Same level of care

as women without impairments | 10 | 45.5 |

| Care viewed as

humanitarian | 12 | 54.5 |

| Awareness of

healthcare providers | | |

| Sufficient

willingness to provide appropriate care | 11 | 50 |

| Perceived knowledge

gap in healthcare professionals | | |

| Identified

substantial knowledge gap | 20 | 90.9 |

| Advocacy for

enhanced training | | |

| Support for

comprehensive training and lifelong learning | 22 | 100 |

| Participant

satisfaction with attitude of healthcare professionals | | |

|

High

satisfaction | 9 | 40.9 |

|

Moderate

satisfaction | 7 | 31.8 |

| Rating of care

quality | | |

|

Excellent

care | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

first to explore the experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and the

puerperium among women with visual impairments in Greece. The

results presented herein underscore the critical need for equitable

access to midwifery and gynecological services for all women.

Demographically, the majority of the study

participants were over >30 years of age, with 86.4% (n=19) being

>35 years and 9.1% (n=2) between 30 and 34 years of age. These

figures align with maternal age trends previously reported in

various countries, including Israel (14), USA (8,15), Iran

(16,19) and Poland (6). In the present study, the majority of

the participants were married (68.2%), held university degrees

(68.2%), and had annual incomes either up to or above €20,000. By

contrast, previous studies have indicated that women with chronic

disabilities, such as blindness are more likely to be divorced or

have only a high school education and are less likely to be

employed or have high incomes (11,12,15,16).

A notable aspect of the present study is the

etiology of visual impairment, with reported causes including

glaucoma, cataract, Stargardt disease, Leber's congenital

amaurosis, retinal detachment, retinoblastoma and aniridia. These

are in line with the findings of previous research demonstrating

that cataract, glaucoma, trachoma and onchocerciasis are the main

reasons for blindness in individuals (20). This information was derived from

specific medical tests documented in the medical records of the

participants.

In the present study, during pregnancy, 81.8% (n=18)

of the participants reported supportive attitudes from HCPs. This

is in contrast to other studies where women with disabilities faced

discouragement from pregnancy due to perceptions of asexuality

(6,8,10,15).

Among the participants in the present study, the majority of

pregnancies were planned (72.7%), with a minority utilizing

fertility treatments, such as IVF. The present study also noted a

lower incidence of smoking and no alcohol or drug use during

pregnancy among participants, a finding consistent with prior

research (5). Routine prenatal

examinations commenced in the first trimester for all participants,

diverging from previous findings (13). Additionally, 31.8% (n=7) of the

participants attended childbirth preparation classes, but some

expressed dissatisfaction with their adaptation to specific needs,

a sentiment that other studies have echoed (7).

As for childbirth specifics, 27.3% (n=6) of the

participants in the present study reported preterm deliveries, and

59.1% (n=13) underwent cesarean sections, with the majority of

newborns weighing >2,500 kg, a finding which was consistent with

previous studies (5,10,13,14). In

the present study, the finding of a high percentage of

low-birth-weight infants aligns with several other studies focusing

on pregnant women with visual impairments and disabilities. For

instance, the study by Ofir et al (14) reported that women with visual

impairments had a higher incidence of low-birth weight infants

compared to the general population. Similarly, the study by Mitra

et al (13) indicated that

women with disabilities, including visual impairments, are at an

increased risk of adverse birth outcomes, including low birth

weight. During the puerperium, challenges included recognizing

infant needs, with some women relying on non-visual cues due to

inadequate support from midwives (19). This period also highlighted unmet

needs for specific accommodations in hospital settings, such as

information on room layouts and proximity to essential

facilities.

Herein, the finding that 68.2% of the blind pregnant

women did not report feelings of loneliness or anxiety at the time

of birth is noteworthy and is in contrast to common perceptions

about the emotional vulnerability of visually impaired individuals

during major life events, such as childbirth (21). Previous research has emphasized the

importance of robust support systems in mitigating feelings of

loneliness and anxiety during childbirth. The presence of

supportive HCPs and family members significantly influences the

emotional well-being of birthing women, reducing feelings of

loneliness and anxiety (22). This

suggests that if visually impaired women receive effective support

from healthcare providers and have family or other support networks

present, their experience of childbirth could be less

anxiety-provoking. In addition, according to another study, women

who are better prepared for childbirth through prenatal education

and childbirth preparation classes report lower levels of anxiety

and a more positive childbirth experience (23). If the women in the present study

participated in tailored childbirth education that addressed their

specific needs as visually impaired individuals, this could have

contributed to their emotional resilience during birth.

In the present study, half (50%) of the participants

perceived that HCPs provided comparable levels of care to visually

impaired and sighted women, though there remains room for

improvement in provider knowledge and sensitivity. This issue calls

for targeted interventions, such as enhanced training for HCPs,

more accessible hospital design, and improved patient-provider

communications, in order to improve perinatal care for women with

visual impairments. There is a critical need for specialized

training and adapted healthcare practices (24).

The clinical implications of the present study on

the experiences of visually impaired women during pregnancy,

childbirth, and the puerperium in Greece are substantial, providing

several actionable insights for HCPs and policymakers There is a

clear need for the additional training for doctors, nurses,

midwives and other healthcare providers on the specific needs of

visually impaired patients. Training should focus not only on the

physical aspects of care, but also on improving communication

methods, understanding accessibility issues and using appropriate

assistive technologies. The study emphasizes the need to develop

and provide specialized resources specifically tailored to the

needs of visually impaired women. This could include informational

materials in accessible formats (e.g., Braille, audio), specialized

equipment for prenatal care, and modifications to existing

healthcare facilities to enhance accessibility. The findings

suggest a need for policy interventions that ensure equitable

access to healthcare services for visually impaired women. Policies

could focus on improving transportation to healthcare facilities,

enhancing the physical layout of healthcare settings, and ensuring

that all health communication is accessible. Clinicians should

consider developing individualized care plans that consider the

unique challenges faced by visually impaired women. These plans

could include more frequent prenatal visits, tailored childbirth

preparation classes, and specialized postpartum support. There is

an imperative to integrate inclusivity into everyday clinical

practice. This includes training staff to be aware of and sensitive

to the stigmas and biases that visually impaired women may face, as

well as directly addressing these issues in clinical settings. The

unique stresses and potential isolation faced by visually impaired

mothers suggest a need for enhanced mental health support during

and after pregnancy. HCPs should be vigilant in monitoring the

mental health of their patients and providing appropriate referrals

and support services. Encouraging the development and involvement

of support networks, including peer-led groups for visually

impaired parents, can provide valuable emotional and practical

support, enhancing the overall pregnancy and postpartum

experience.

Despite its small scale, the diverse sample study

sample herein suggests that the experiences of visually impaired

women giving birth post-2005 in Greece share both similarities and

distinct differences from global data, providing insight that may

be informative for future healthcare policies and practices.

The study has some potential limitations however,

which should be mentioned. These are as follows: i) Small sample

size: The present study only included 22 participants, which limits

the generalizability of the findings. A larger sample size would

provide more robust data and allow for more definitive conclusions.

ii) Geographic limitation: The present study was mainly confined to

Athens, Greece. The inclusion of participants from other regions

would offer a more comprehensive understanding of the perinatal

care experiences of visually impaired women across the country.

iii) Retrospective nature: The retrospective design relies on the

recall of past events by participants, which may introduce recall

bias. Prospective studies could provide more accurate and timely

data. iv) Lack of a control group: The absence of a comparison

group of non-visually impaired women makes it difficult to isolate

the specific challenges faced by visually impaired women from

broader trends in maternal healthcare. v) Self-reported data: The

reliance on self-reported data can introduce bias, as participants

may underreport or overreport certain behaviors or experiences due

to social desirability or personal interpretation of the questions.

vi) Technological accessibility: While the electronic questionnaire

was designed to be accessible, it may still exclude individuals who

are less comfortable with technology or lack access to the

necessary devices and software. vii) Cultural and systemic factors:

The findings of the present study were influenced by the specific

cultural and healthcare system context of Greece, which may limit

their applicability to other countries with different healthcare

systems and cultural norms regarding disability. Another limitation

is that the researchers do not have available representative

examination tests proving the visual impairment of the

participants.

In conclusion, the present study provides valuable

insight into the reproductive healthcare experiences of visually

impaired women in Greece, highlighting substantial barriers and

societal challenges. The findings emphasize the need for tailored

healthcare services that address the unique needs of this

population and ensure equitable access to care. Despite a proactive

approach by these women to planning pregnancies and seeking

prenatal care, stigmatization and inadequate healthcare service

adaptations remain pervasive. This underscores the urgent need for

healthcare providers to undergo comprehensive training to better

understand and address the needs of visually impaired women. In

essence, the present study calls for systemic reforms in maternal

healthcare practices to remove both physical and attitudinal

barriers, ensuring a respectful, competent, and inclusive

healthcare environment for all women, regardless of visual

impairment.

Supplementary Material

QUESTIONNAIRE

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

CM and AD conceptualized the study. CM and AD made a

substantial contribution to data interpretation and analysis, and

wrote and prepared the draft of the manuscript. CM and AD analyzed

the data and provided critical revisions. CM and AD confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors contributed to

manuscript revision, and have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study received approval from the

committee of the Midwifery Department of the University of West

Attica (Athens, Greece) and was closely monitored during its

execution by a three-member committee. The protocol number of the

Research Ethics Boards of the University of West Attica was

20/27-09-2019, ensuring adherence to the highest standards of

research ethics and participant confidentiality. All participants

provided written consent to participate in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, the AI tool

Chat GPT was used to improve the readability and language of the

manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised and edited the

content produced by the AI tool as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

World Health Organization. World Report on

Vision. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516570,

Geneva, 2019.

|

|

2

|

Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T,

Cicinelli MV, Das A, Jonas JB, Keeffe J, Kempen JH, Leasher J,

Limburg H, et al: Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of

the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision

impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob

Health. 5:e888–e897. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Conley-Jung C and Olkin R: Mothers with

visual impairments who are raising young children. J Vis Impair

Blind. 95:14–29. 2001.

|

|

4

|

Leveziel N, Marillet S, Braithwaite T,

Peto T, Ingrand P, Pardhan S, Bron AM, Jonas JB, Resnikoff S,

Little JA and Bourne RRA: Self-reported visual difficulties in

Europe and related factors: A European population-based

cross-sectional survey. Acta Ophthalmol. 99:559–568.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Morton C, Le JT, Shahbandar L, Hammond C,

Murphy EA and Kirschner KL: Pregnancy outcomes of women with

physical disabilities: A matched cohort study. PM&R. 5:90–98.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mazurkiewicz B, Stefaniak M and

Dmoch-Gajzlerska E: Perinatal care needs and expectations of women

with low vision or total blindness in Warsaw, Poland. Disabil

Health J. 11:618–623. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Carty EM, Conine TA and Hall L:

Comprehensive health promotion for the pregnant woman who is

disabled. The role of the midwife. J Nurse Midwifery. 35:133–1342.

1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Smeltzer SC, Mitra M, Iezzoni LI,

Long-Bellil L and Smith LD: Perinatal experiences of women with

physical disabilities and their recommendations for clinicians. J

Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 45:781–789. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Beverley CA, Bath PA and Barber R: Health

and social care information for visually-impaired people. InAslib

Proceedings. 63:256–274. 2011.

|

|

10

|

Signore C, Spong CY, Krotoski D, Shinowara

NL and Blackwell SC: Pregnancy in women with physical disabilities.

Obstet Gynecol. 117:935–947. 2011.

|

|

11

|

Iezzoni LI, Yu J, Wint AJ, Smeltzer SC and

Ecker JL: Prevalence of current pregnancy among US women with and

without chronic physical disabilities. Med Care. 51:555–562.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Krahn GL, Walker DK and Correa-De-Araujo

R: Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity

population. Am J Public Health. 105 (Suppl 2):S198–S206.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Mitra M, Clements KM, Zhang J, Iezzoni LI,

Smeltzer SC and Long-Bellil LM: Maternal characteristics, pregnancy

complications, and adverse birth outcomes among women with

disabilities. Med Care. 53:1027–1032. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ofir D, Kessous R, Belfer N, Lifshitz T

and Sheiner E: The influence of visual impairment on pregnancy

outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 291:519–523. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Horner-Johnson W, Darney BG,

Kulkarni-Rajasekhara S, Quigley B and Caughey AB: Pregnancy among

US women: Differences by presence, type, and complexity of

disability. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 214:529.e1–529.e9. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Aval ZO, Rabieepoor S, Avval JO and Yas A:

The effect of education on blind women's empowerment in

reproductive health: A Quasi-experimental survey. Maedica (Bucur).

14:121–125. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Beverley CA, Bath PA and Booth A: Health

information needs of visually impaired people: A systematic review

of the literature. Health Soc Care Community. 12:1–24.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Walsh-Gallagher D, Mc Conkey R, Sinclair M

and Clarke R: Normalising birth for women with a disability: The

challenges facing practitioners. Midwifery. 29:294–299.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Moghadam ZB, Ghiyasvandian S,

Shahbazzadegan S and Shamshiri M: Parenting Experiences of Mothers

who Are Blind in Iran: A Hermeneutic Phenomenological Study. J Vis

Impair Blind. 111:113–122. 2017.

|

|

20

|

Resnikoff S and Keys TU: Future trends in

global blindness. Indian J Ophthalmol. 60:387–395. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Demmin DL and Silverstein SM: Visual

impairment and mental health: Unmet needs and treatment options.

Clin Ophthalmol. 14:4229–4251. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Battulga B, Benjamin MR, Chen H and

Bat-Enkh E: The impact of social support and pregnancy on

subjective well-being: A systematic review. Front Psychol.

12(710858)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Karabulut Ö, Coşkuner Potur D, Doğan Merih

Y, Cebeci Mutlu S and Demirci N: Does antenatal education reduce

fear of childbirth? Int Nurs Rev. 63:60–67. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Diamanti A, Sarantaki A, Gourounti K and

Lykeridou A: perinatal care in women with vision disorders: A

systematic review. Maedica (Bucur). 16:261–267. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|