Introduction

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) is a rare form of cold

autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Also referred to as primary CAD, this

chronic condition is characterized by complement-mediated hemolysis

and non-progressive, clinically non-malignant B cell proliferation.

CAD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients

presenting with unexplained anemia, with or without associated

cold-related symptoms, such as acrocyanosis, livedo reticularis,

Raynaud's phenomenon and fingertip ulceration. Notably, nearly all

cold agglutinins test positive for the C3d direct antiglobulin test

(1).

Cold autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) can be

classified into primary CAD and secondary cold agglutinin syndrome

(CAS), with the latter often triggered by underlying conditions,

such as infections (e.g., mycoplasma pneumoniae, Epstein-Barr virus

or influenza A), malignancies (e.g., diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,

Hodgkin lymphoma or metastatic melanoma) and autoimmune diseases

(e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus). In the differential diagnosis

of cold AIHA, other causes of hemolysis should also be considered,

including warm AIHA, hereditary hemolytic anemias (e.g., hereditary

spherocytosis or G6PD deficiency), paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria

and drug-induced hemolysis. Cold-induced hemolysis can also occur

in cases of hypothermia or mechanical damage to red blood cells

(RBCs), although these do not typically result in cold

agglutination. The diagnosis of cold AIHA involves clinical

evaluation, testing for cold agglutinins, direct antiglobulin tests

and the careful exclusion of other potential causes of hemolysis,

such as infections, malignancies, or hereditary conditions

(2).

For the majority of patients without severe

symptoms, a strategy of watchful waiting is appropriate.

Conventional treatment options, such as corticosteroids,

azathioprine, or cyclophosphamide which are typically effective in

warm antibody-mediated AIHA, are ineffective for CAD. Moreover, a

splenectomy is not beneficial in CAD, as hemolysis predominantly

occurs in the liver. Rituximab monotherapy is considered the

first-line treatment for CAD. Other treatment options include the

use of bendamustine, combinations of rituximab and bendamustine,

ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, venetoclax, eculizumab and sutimlimab

(3,4). Currently, to the best of our knowledge,

there is no specific treatment option available for secondary CAS

other than addressing the underlying disease.

The present study describes the case of a male

patient who sought a second opinion at the authors' clinic due to

newly detected anemia.

Case report

A 53-year-old male patient presented to the

Department of Hematology, Dokuz Eylul University Hospital, Izmir,

Turkey, seeking a second opinion regarding anemia newly detected

during routine check-ups. The patient, who reported no symptoms,

had a medical history of diabetes, hypertension and inactive

chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection for the past 10 years. He

was being treated with metformin, losartan and amlodipine. His

family history did not reveal any significant findings. The patient

had been a smoker for >20 years and consumed alcohol

socially.

A physical examination revealed no abnormalities.

Prior to his visit to the Department of Hematology, Dokuz Eylul

University Hospital, two separate complete blood count (CBC)

analyses were conducted at two different hospitals the previous

week, yielding conflicting results: One report indicated normal

findings, while the other indicated macrocytic anemia.

A CBC, hemolytic parameters (including lactate

dehydrogenase, bilirubin, haptoglobin and reticulocyte count), and

a peripheral blood smear were performed. Routine blood tests,

including liver and kidney function tests, yielded results which

were within normal range. The initial CBC results indicated an

elevated mean corpuscular volume and mean corpuscular hemoglobin

concentration, alongside a decreased RBC count and hematocrit,

while hemoglobin levels remained within the normal range (Table I). The peripheral blood smear

revealed agglutination of the RBCs. Other tests, including

hemolytic parameters, yielded results which were within normal

limits.

| Table IComplete blood count of unheated and

heated blood samples. |

Table I

Complete blood count of unheated and

heated blood samples.

| Test/parameter | Unheated sample | Heated sample | Reference range | Units |

|---|

| WBC | 6.6 | 6.2 | 4-10.3 | 10³/µl |

| Neutrophils | 5.7 | 4.6 | 2.1-6.1 | 10³/µl |

| Lymphocytes | 0.4 | 1 | 1.3-3.5 | 10³/µl |

| Monocytes | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3-0.9 | 10³/µl |

| Eosinophils | 0 | 0.1 | 0-0.5 | 10³/µl |

| Basophils | 0 | 0 | 0-0.2 | 10³/µl |

| RBC | 1.72 | 4.73 | 4-5.7 |

106/µl |

| Hemoglobin | 14.2 | 14.5 | 12-16 | g/dl |

| Hematocrit | 19.1 | 41.9 | 36-46 | % |

| MCV | 110.8 | 88.6 | 80.7-95.5 | fl |

| MCH | 82.7 | 30.7 | 27.2-33.5 | pg |

| MCHC | 74.6 | 34.7 | 32.7-35.6 | g/dl |

| RDW | 14.5 | 13.6 | 11.8-14.3 | % |

| Platelets | 192 | 289 | 156-373 | 10³/µl |

| MPV | 9.9 | 8.4 | 6.9-10.8 | fl |

| Plateletcrit | 0.189 | 0.249 | 0.20-0.36 | % |

Further analyses revealed negative cryoglobulin and

mycoplasma antibody test results, normal blood

immunoelectrophoresis, a positive direct Coombs test (C3d), and a

positive cold agglutinin titer of 1:256 at 4˚C, leading to a

definitive diagnosis of cold AIHA. A second CBC and peripheral

blood smear conducted with warmed blood samples yielded normal CBC

results (Table I) and the

disappearance of RBC agglutination.

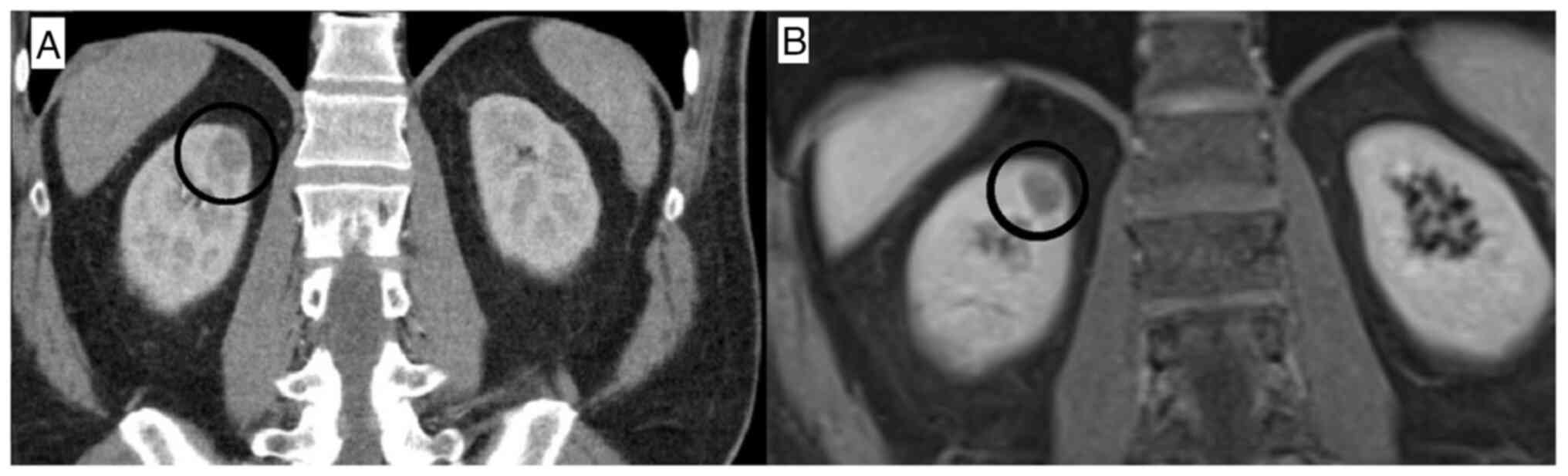

A whole-body computed tomography (CT) scan revealed

a mass 2 cm in size in the right kidney (Fig. 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging of the

mass suggested renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, the patient

underwent partial nephrectomy, and a pathological examination

confirmed the diagnosis of RCC. No other abnormalities were noted

on cross-sectional imaging. Notably, no secondary cause of cold

AIHA was identified. A bone marrow biopsy was performed, revealing

no malignancy or evidence of cold agglutinin-associated

lymphoproliferative bone marrow disease.

The patient was routinely monitored, and the CBC

remained consistent with the initial findings. The persistent

agglutination of RBCs was noted in the peripheral blood smear, with

no notable hemolysis observed during follow-up.

At 2 years following his initial visit, the patient

presented to the hematology department with complaints of a growing

mass in the groin. He did not report any symptoms of B-cell

lymphoma, such as unexplained weight loss, night sweats, or fever.

The initial examination revealed hepatosplenomegaly and a bilateral

enlargement of the inguinal lymph nodes. A CBC indicated

lymphopenia and marked anemia. Similar to the first presentation,

the agglutination of erythrocytes was observed in the peripheral

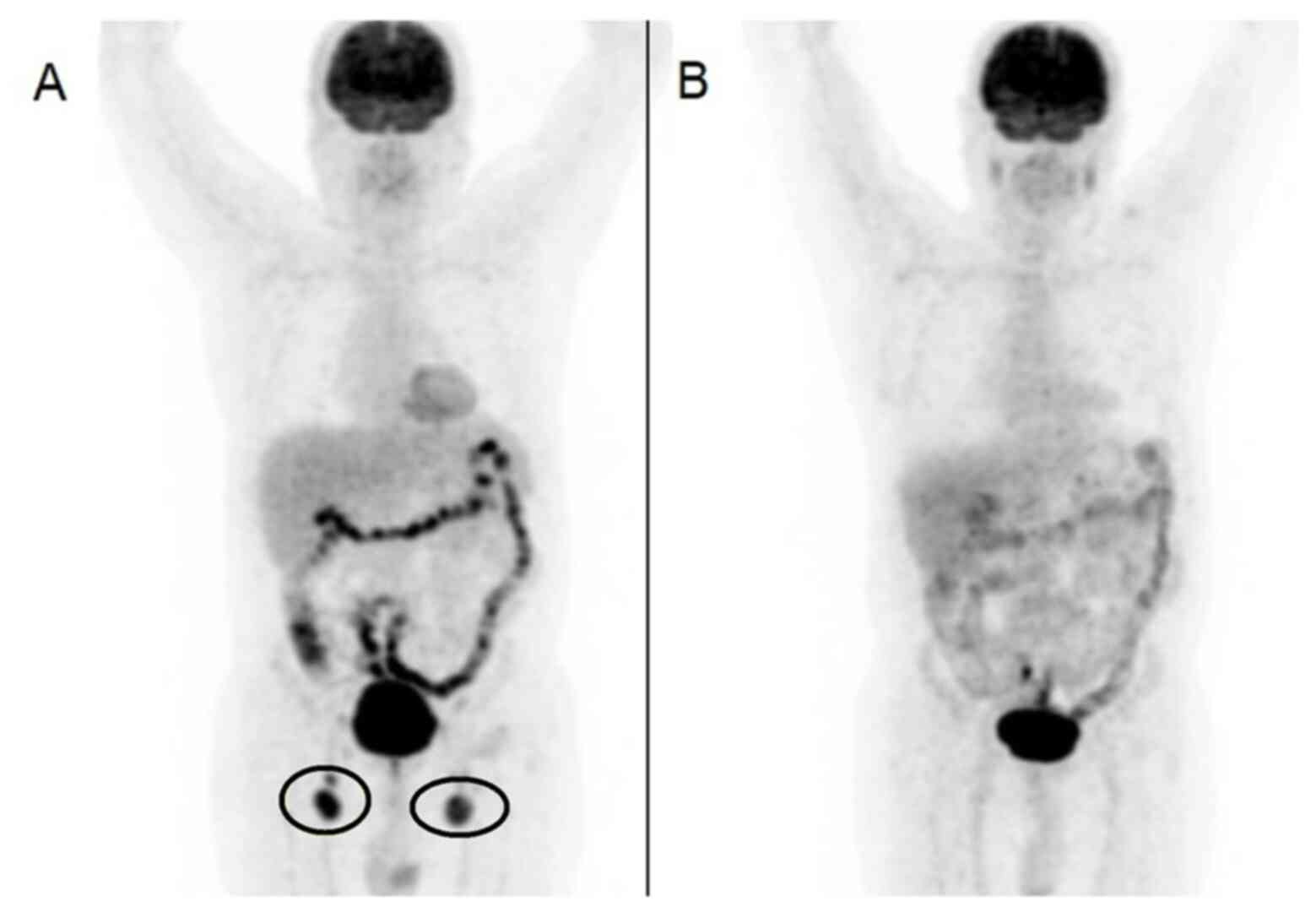

blood smear. A fludeoxyglucose-18 (FDG) positron emission

tomography (PET)CT scan was requested, and the results were

consistent with lymphoma (Fig. 2A).

A biopsy was performed on the right inguinal lymph node, and

histological examination revealed low-grade B-cell lymphoma. A

repeat bone marrow biopsy was conducted, and histological analysis

reported hypercellular bone marrow without evidence of clonal

disease, lymphoma infiltration, or cold agglutinin-associated

lymphoproliferative bone marrow disease.

Routine laboratory examinations prior to initiating

chemotherapy did not detect any abnormal findings, including

aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, kidney

function tests and liver function tests. Moreover, it is standard

procedure in Turkey to screen for HBV infection prior to

chemotherapy: HBsAg was positive as was expected, and HBV-DNA was

positive, although at an undetectable level. Therefore, tenofovir

alafenamide was initiated as HBV reactivation prophylaxis. No HBV

reactivation was detected before or after chemotherapy.

The patient was subsequently initiated on R-CHOP

therapy (cycle repeats every 21 days), consisting of rituximab (375

mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), cyclophosphamide (750

mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), doxorubicin (50

mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), vincristine (1.4

mg/m2 intravenously on day 1) and prednisone (40

mg/m2 perorally on every day of first week in every

cycle). A second FDG PET/CT was ordered, and the patient exhibited

a complete response after two cycles of R-CHOP treatment (Fig. 2B). It was decided to complete a total

of four cycles of R-CHOP. Following this regimen, the patient began

rituximab maintenance therapy (375 mg/m2 intravenously

every 6 months). Peripheral blood smears were performed after the

second and fourth cycles of chemotherapy, as well as at the 6-month

mark following the completion of chemotherapy. Post-treatment, the

CBC and peripheral blood smear returned to normal limits, and the

erythrocyte agglutinations previously observed in the peripheral

blood smear conducted with unheated blood were no longer

present.

Discussion

In the case described in the present study, there

was no true anemia or associated symptoms at the initial

presentation; however, anemia is the most prevalent finding in cold

AIHA, occurring in 51% of patients at diagnosis (5). The first indication of CAS was the

discrepancy observed between two CBCs performed prior to the

admission of the patients to hospital. Subsequent re-examinations

using heated blood samples revealed the disappearance of

erythrocyte agglutination in the peripheral blood smear, alongside

a return to normal CBC values, which were crucial for the diagnosis

of CAS in this instance. The findings on the CBC were

contradictory, as the degree of RBC agglutination is dependent on

the environmental temperature and the duration of exposure. Various

factors, including the time from obtaining the blood sample to

receiving the laboratory results, could affect the impact of

environmental temperature on the degree of agglutination.

Terán Brage et al (6) presented an intriguing case of CAS in a

patient with renal carcinoma; a male in his 60s was diagnosed with

paraneoplastic CAS, while being evaluated for microcytic anemia

with evident hemolysis. In the case described herein, RCC was

incidentally identified during the investigation of secondary

causes, and while the tumor was excised, the findings of CAS

persisted, suggesting no clear association between RCC and CAS in

this instance. Notably, the patient in the present study exhibited

no signs of anemia or hemolysis, and the initial CBC erroneously

indicated macrocytic anemia due to erythrocyte agglutination.

Furthermore, cold AIHA may also manifest in renal findings;

Taberner et al (7) reported a

case of renal hemosiderosis associated with CAD.

Additionally, there are case reports linking CAS to

lymphoma (8,9). In the present case report, CAS was

identified during the evaluation of conflicting CBC results; the

patient remained asymptomatic, with no true anemia or clear

hemolytic signs. While other case reports have diagnosed lymphoma

during the investigation of CAS, the patient in the present study

was diagnosed with lymphoma 2 years after CAS was detected

(8-10).

CAS may serve as an early indicator of lymphoma, as

supported by previous case reports in the literature (10,11).

Following R-CHOP treatment, both the peripheral smear and CBC

returned to normal limits, leading the authors to conclude that the

cold-type AIHA of the patient was attributable to lymphoma. It can

thus be hypothesized that CAS was the earliest manifestation of the

lymphoma in the patient described herein.

It may be suspected that chronic HBV infection was a

risk factor for the patient developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

There is an established link between chronic HBV infection and NHL.

Furthermore, the risk is higher in Asian populations, such as in

Turkey (12).

In conclusion, it is imperative to investigate the

underlying causes in patients newly diagnosed with CAD. Cold AIHA

may serve as an early indicator of lymphoma that can manifest years

prior, necessitating routine monitoring for these patients. In the

case that hemoglobin levels are stable in the CBC, and significant

fluctuations are observed in the erythrocyte count, hematocrit,

mean corpuscular volume and mean corpuscular hemoglobin

concentration, particularly if they do not match the clinical

presentation of the patient, then CAD should be considered.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

HD was a major contributor to the writing of the

manuscript, and both authors (HD and GHÖ) commented on subsequent

versions. Both authors (HD and GHÖ) contributed to data collection,

treatment and patient follow-up. HD and GHÖ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors (HD and GHÖ) have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study followed international and

national regulations and was in agreement with the Declaration of

Helsinki, and ethical principles. Dokuz Eylul University Hospital

does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or

case series. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient

for his anonymized information to be published in this article.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for his anonymized information and any related images to be

published in this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests

References

|

1

|

Gabbard AP and Booth GS: Cold agglutinin

disease. Clin Hematol Int. 2:95–100. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Berentsen S: Cold agglutinin disease.

Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016:226–231.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jäger U, Barcellini W, Broome CM, Gertz

MA, Hill A, Hill QA, Jilma B, Kuter DJ, Michel M, Montillo M, et

al: Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in

adults: Recommendations from the First International Consensus

Meeting. Blood Rev. 41(100648)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Röth A, Barcellini W, D'Sa S, Miyakawa Y,

Broome CM, Michel M, Kuter DJ, Jilma B, Tvedt THA, Fruebis J, et

al: Sutimlimab in cold agglutinin disease. N Engl J Med.

384:1323–1334. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Pham HP, Wilson A, Adeyemi A, Miles G,

Kuang K, Carita P and Joly F: An observational analysis of disease

burden in patients with cold agglutinin disease: Results from a

large US electronic health record database. J Manag Care Spec

Pharm. 28:1419–1428. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Terán Brage E, Fonseca Santos M, Lozano

Mejorada R, García Domínguez R, Olivares Hernández A, Amores Martín

A, Vidal Tocino R and Fonseca Sánchez E: Autoimmune haemolytic

anaemia due to cold antibodies in a renal cancer patient. Case Rep

Oncol. 15:507–514. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Taberner K, House AA, Haig A and Hsia CC:

A case of renal iron overload associated with cold agglutinin

disease successfully managed by rituximab. Clin Hematol Int.

5:62–66. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Portich JP, Blos B, Sekine L and Franz

JPM: Cold agglutinin syndrome secondary to splenic marginal zone

lymphoma: A case report. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 45:403–405.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lin H, Feng D, Tao S, Wu J, Shen Y and

Wang W: A patient with the highly suspected B cell lymphoma

accompanied by the erythrocytes cold agglutination: Case report.

Medicine (Baltimore). 102(e34076)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Goyal K, Sharma R and Garg S: Intestinal

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma preceding cold agglutinin disease. J

Appl Hematol. 11:137–140. 2020.

|

|

11

|

Ranjan V, Dhingra G, Gupta N, Khillan K

and Rana R: Cold agglutinin autoimmune haemolytic anaemia as an

initial presentation of diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A case

study. Curr Med Res Pract. 12:183–187. 2022.

|

|

12

|

Gentile G, Arcaini L, Antonelli G and

Martelli M: Editorial: HBV and lymphoma. Front Oncol.

13(1236816)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|