Introduction

Varices are dilated, edematous superficial veins

located in the subcutaneous tissue, commonly occurring in pregnant

women, and are typically found in the lower extremities. Pregnancy

is considered a significant contributing factor to the increased

incidence of varicose veins (1,2). In

addition to the lower extremities, varicose veins can also appear

in the hemorrhoidal plexus, vulva, vagina and, less commonly, in

the cervix during pregnancy. The incidence of vulvar varicose veins

in pregnant women exhibited an increase, affecting up to 8% of all

pregnancies (3). The management of

severe vulvovaginal varices presents a challenge in everyday

obstetric practice, often requiring the collaboration of

radiologists, vascular surgeons and obstetrician-gynecologists

(4).

Cervical varices are a rare clinical finding during

pregnancy. To date, only 21 cases have been documented in the

international English-language literature (5). Cervical varices are dilated vascular

structures that can protrude through the dilated endocervical canal

to varying degrees. Their superficial position close to the

epithelium and their dilation, renders them anatomical weak points,

susceptible to rupture, thus potential causes of severe,

life-threatening bleeding during the antenatal period (5). Their pathogenetic mechanisms are not

yet fully understood; however, their incidence appears to be

associated with low placental implantation, an advanced maternal

age, twin pregnancies and exposure to diethylstilbestrol (5,6). Based

on data from the literature, cervical varices may be superficial or

originating from the endocervix, a feature that significantly

affects appearance during a physical examination and imaging

(7). Superficial, os-type varices

are more easily visualized during a speculum examination, as is the

detection of the precise site of bleeding in the case of rupture

(5,7). Internal, endocervix varices are usually

more difficult to detect via speculum examination, and are better

visualized via vaginal ultrasound and Doppler mode (5,7). However

they may also be visible via a speculum examination in the case of

multiple, highly enlarged varices that protrude from the external

os (such as in the case in the present study). Hemorrhagic

endocervical varices are rarely observed in the first trimester of

pregnancy. Cervical varices usually occur in the second or third

trimester of pregnancy and may be associated with fetal loss

following the termination of the pregnancy with a non-viable fetus

(as in the case in the present study) or with pre-term delivery

(6).

The present study describes a rare case of fetal

loss at 21 weeks of gestation due to severe bleeding from ruptured

cervical varices. The authors wish to emphasize the role of

transvaginal ultrasonography and transvaginal Doppler

ultrasonography in the early diagnosis of this condition, aiming to

reduce maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Additionally, the importance of differentiating bleeding caused by

cervical varices from vaginal bleeding associated with peripheral

placental abruption, particularly in cases complicated by placenta

previa is highlighted.

Case report

The present case report concerns a 26-year-old

primigravida who presented early in the morning to the Emergency

Department of the General Hospital of Trikala, Trikala, Greece, at

21 weeks of gestation, reporting an episode of major vaginal

bleeding at ~1 h prior. The pregnant woman described the bleeding

as heavy, with large blood clots. Her hemodynamic status was

stable, with a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg and a heart rate of 84

beats per minute, indicating tolerable blood loss severity and

allowing for the performance of all necessary investigations. The

vaginal hemorrhage was not accompanied by pain. The patient had

been followed-up at a private obstetric center, where a low-lying

placenta (placenta previa) was identified via ultrasound during the

first trimester. Nuchal translucency was measured at 1.2 mm, and no

fetal anatomical abnormalities were detected. A previous minor

vaginal hemorrhage (first episode) was reported ~1 month earlier.

According to the patient, the bleeding, attributed by her

obstetrician to peripheral abruption of the placenta previa,

resolved within 1 week following bed rest and oral progesterone

administration. An investigation of her medical history did not

reveal any notable findings, and no evidence of exposure to

diethylstilbestrol was found. This was a singleton pregnancy,

resulting from spontaneous conception.

Upon a gynecological vaginal examination, a large

amount of vaginal bleeding was observed, which obscured a clear

view of the cervix during the examination. An obstetric ultrasound

revealed a normal fetal heart rate, with the amount of amniotic

fluid within normal limits. The placenta was located in an anterior

low position, with no obvious signs of abruption on the ultrasound.

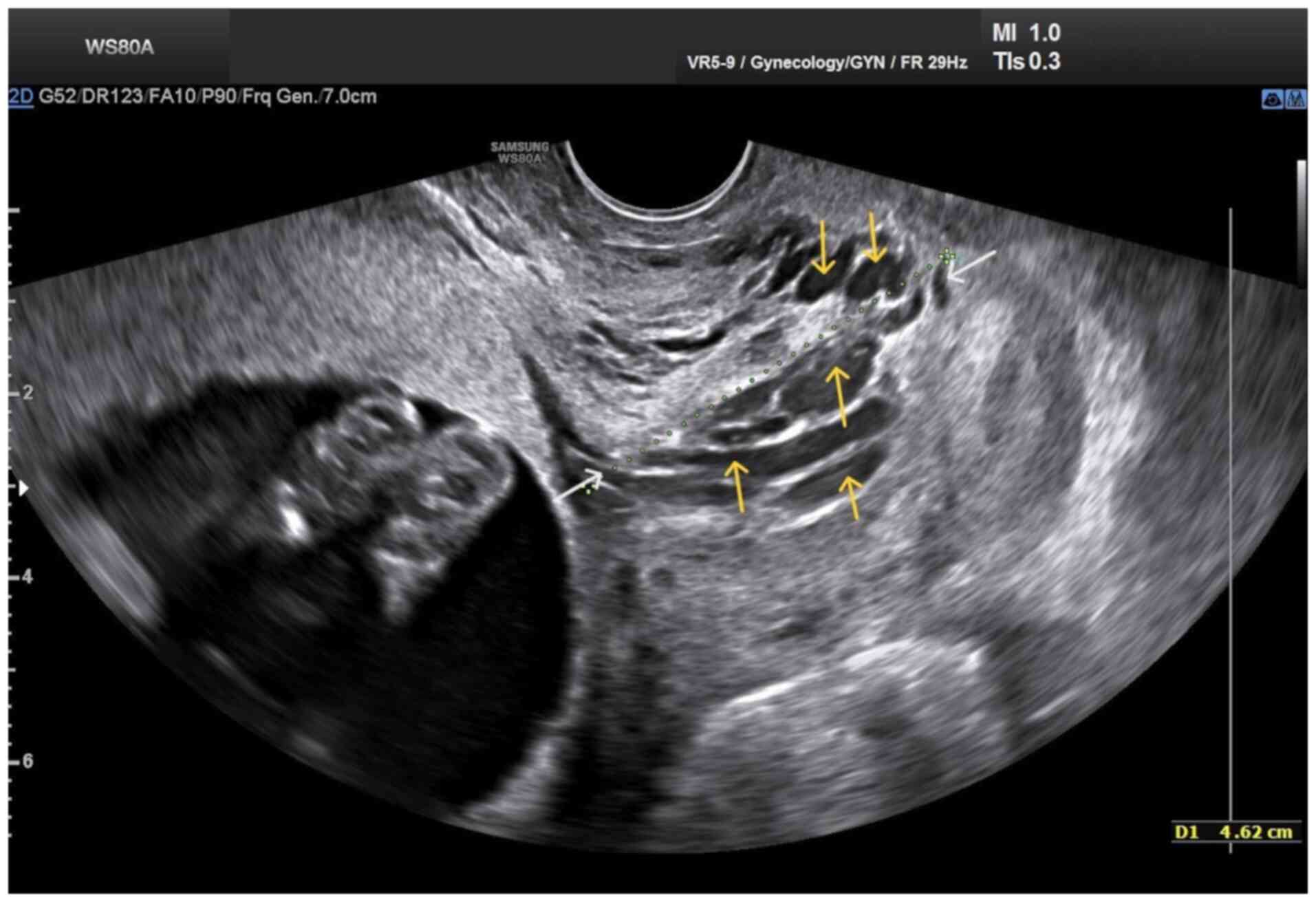

The transvaginal ultrasound revealed a normal cervical length of 46

mm. However, the imaging revealed dilated, elongated structures

protruding through the dilated endocervical canal, which were

characteristic (Fig. 1). A

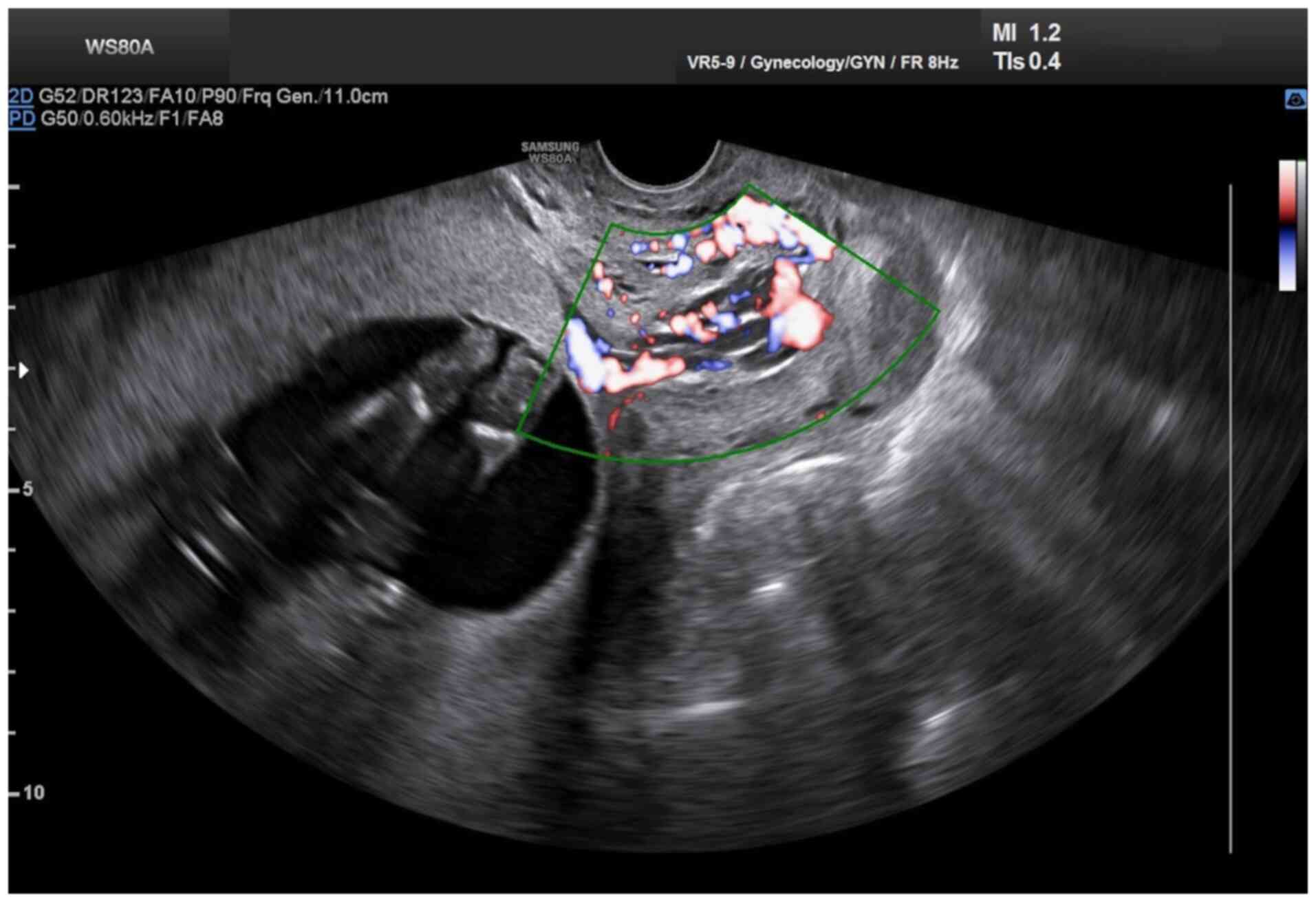

transvaginal Doppler ultrasound of the endocervix demonstrated

dilated, elongated longitudinal structures with increased

vascularization, involving the majority of the cervix. These

findings were consistent with dilated vascular structures (Fig. 2). Due to the ongoing vaginal bleeding

following the admission of the patient to the clinic, a more

thorough vaginal examination was performed under general anesthesia

in the operating room. The operating theatre was adequately

prepared for the possibility of pregnancy termination via

laparotomy in the event of a major hemorrhage. A careful inspection

of the cervix revealed enlarged varicose-like vessels projecting

through the cervical canal up to the external cervical os, which

were actively bleeding (Fig. 3).

During an attempt to palpate the vascular structures in the cervix,

profuse vaginal bleeding was triggered. To manage the bleeding

temporarily, several hemostatic forceps were applied (Fig. 4).

With the patient in the gynecological laparoscopy

position, an emergency cesarean section was performed. The

umbilical vessels were clipped and the fetus was delivered and

subsequently handed to the neonatologist for assessment, who

unfortunately confirmed its demise shortly thereafter. The placenta

was removed, without any evidence of placenta accreta spectrum

disorder or vascular malformations in the lower uterine segment

near the internal cervical os being observed. However, severe

intraoperative bleeding necessitated the decision to perform a

utero-cervico-vaginal tamponade with gauze packing, along with the

transfusion of 3 units of packed red blood cells and 1 unit of

fresh frozen plasma. Prior to the tamponade, the previously placed

hemostatic forceps were removed. Immediately post-operatively, the

dilated vessels in the endocervix were no longer visible, and no

active bleeding was observed during inspection. For post-operative

hemodynamic stabilization (Table I),

an additional transfusion of 3 units of packed red blood cells was

required. The utero-cervico-vaginal gauze tamponade was removed on

the first post-operative day. Antibiotic treatment was initiated,

with cefuroxime (Mefoxil) administered at a dose of 2 g every 8 h

for 4 days, combined with metronidazole (Flagyl) at 500 mg every 8

h for 2 days. The patient was discharged from the clinic on the 5th

post-operative day. At 20 days thereafter, both the clinical

cervical examination findings (Fig.

5) and transvaginal Doppler ultrasound findings (Fig. 6) were normal. Since then, all

subsequent follow-up assessments have been performed at the private

obstetric center the patient attended before her presentation to

our hospital. At the time of writing the patient is healthy,

without bleeding and has not yet made another attempt at conception

and pregnancy.

| Table IPre-operative and post-operative

laboratory tests of the patient during her hospitalization at the

clinic. |

Table I

Pre-operative and post-operative

laboratory tests of the patient during her hospitalization at the

clinic.

| Laboratory tests | Pre-operatively | At 6 h after

surgery | 1st post-operative

day | 2nd post-operative

day | 4th post-operative

day | Normal laboratory

values |

|---|

| Ht | 26.6%a,b | 20.8%c | 18.2%d | 25.4% | 25.4% | 37.7-49.7% |

| Hb | 9.7 g/dl | 7.6 g/dl | 6.7 g/dl | 9.2 g/dl | 8.6 g/dl | 11.8-17.8 g/dl |

| WBC |

9.1x103/ml |

16.1x103/ml |

14.4x103/ml |

13.89x103/ml |

7.51x103/ml |

4-10.8x103/ml |

| NEUT | 83.2% | 87.3% | 86.8% | 78.7% | 62.1% | 40-75% |

| PLT |

205x103/ml |

121x103/ml |

107x103/ml |

135x103/ml |

186x103/ml |

150-350x103/ml |

| CRP | 0.06 mg/dl | 0.3 mg/dl | 5.55 mg/dl | 14.55 mg/dl | 2.17 mg/dl | <0.5 mg/dl |

| APTT | 29.8 sec | 27.8 sec | 35.3 sec | 31 sec | 31 sec | 24.0-35.0 sec |

| INR | 0.89 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 0.8-1.2 |

| FIB | 286 mg/dl | 232 mg/dl | 237 mg/dl | 422 mg/dl | 385 mg/dl | 200-400 mg/dl |

| Glu | 76 mg/dl | 133 mg/dl | 69 mg/dl | 81 mg/dl | 90 mg/dl | 75-115 mg/dl |

| U | 30 mg/dl | 29 mg/dl | 22 mg/dl | 25 mg/dl | 24 mg/dl | 10-50 mg/dl |

| Cr | 0.6 mg/dl | 0.6 mg/dl | 0.46 mg/dl | 0.51 mg/dl | 0.49 mg/dl | 0.40-1.10 mg/dl |

| K+ | 4.17 mmol/l | 4.1 mmol/l | 3.24 mmol/l | 3.51 mmol/l | 3.49 mmol/l | 3.5-5.1 mmol/l |

| Na+ | 135 mmol/l | 133 mmol/l | 140.5 mmol/l | 139 mmol/l | 141.7 mmol/l | 136-145 mmol/l |

| B | 0.5 mg/dl | 0.92 mg/dl | 0.48 mg/dl | | | 0.3-1.2 mg/dl |

| SGOT | 28 IU/l | 27 IU/l | 17 IU/l | | | 5-33 IU/l |

| SGPT | 13 IU/l | 14 IU/l | 11 IU/l | | | 10-37 IU/l |

Discussion

The pathogenesis of cervical varices in pregnant

women has not been fully elucidated. Placenta previa is thought to

be the main risk factor. Placenta previa, along with the increased

cervical blood flow that characterizes such cases, appears to be

significantly associated with the development of venous distension

and varices in the area (7). In

addition, prenatal maternal exposure to diethylstilbestrol, which

can cause vascular malformations in the pelvic organs, has been

implicated in the development of cervical varicose veins. Moreover,

the interaction between the uterus and placenta in women exposed to

diethylstilbestrol is well known (8). Furthermore, in vitro

fertilization, the multiple pregnancies frequently resulting from

it, and a maternal age >35 years, which often characterizes

these pregnant women, are additional risk factors for cervical

varices (9). In rare cases, the

development of cervical varices in pregnancy may occur in the

absence of these risk factors (10).

The patient in the present study was 26 years of age and carried a

singleton pregnancy following spontaneous conception. No evidence

suggesting exposure to diethylstilbestrol at the time of the case

was found. In the patient described herein, the only predisposing

risk factor for the development of cervical varices was a low-lying

placenta.

The prenatal diagnosis of cervical varices is based

on a clinical examination, transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic

resonance imaging. The recognition of the clinical features of

cervical varices during pregnancy is of utmost importance for the

accurate diagnosis of this rare clinical entity before major

bleeding occurs due to rupture (11). Bleeding is the predominant symptom

and usually indicates rupture of the cervical varices (12). It is crucial to avoid confusion with

vaginal hemorrhage due to peripheral abruption of a placenta

previa, which often accompanies cervical varices (5). Additionally, the differentiation

between bleeding caused by the rupture of cervical varices and that

caused by vasa previa is of great diagnostic value. Vasa previa

originate from the placenta, whereas cervical varices are of

maternal origin and are not necessarily related to the placenta

(12). A gynecological clinical

examination with careful cervical inspection is thought to be of

considerable help in the diagnosis of cervical varices. However,

unlike transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging, it

is unable to accurately assess the origin, nature, and extent of

cervical varices (12).

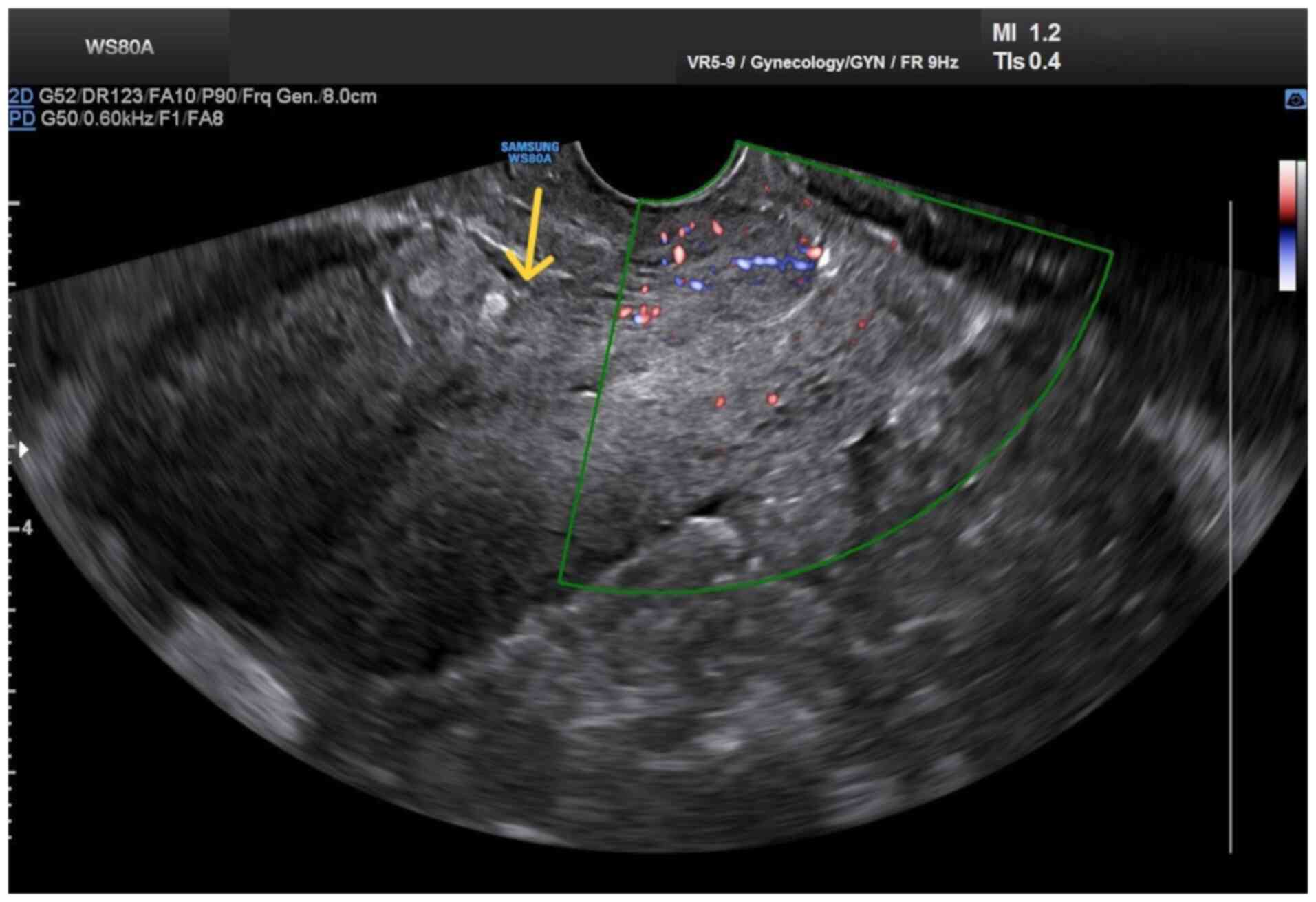

Transvaginal ultrasound easily detects the presence

of a placenta previa, which often accompanies cervical varices in

pregnant women. At the same time, it can identify a hypoechoic

structure in the endocervix, which, when examined by Doppler

transvaginal ultrasound, suggests a vascular origin (13). Magnetic resonance imaging, although

not readily available for every pregnant woman with bleeding, is

considered very valuable for accurately visualizing the vessel

distribution in relation to adjacent organs and for excluding other

unforeseen pelvic pathological conditions prior to a planned

cesarean section (12). In the

patient in the present study, the presence of placenta previa and

the onset of a small vaginal hemorrhage in the late first trimester

initially raised the suspicion of possible peripheral placental

abruption. The diagnosis of cervical varices was established by

transvaginal Doppler ultrasonography and a detailed vaginal

examination under anesthesia after the incident of severe vaginal

bleeding in the second trimester. Upon a cervical examination, a

mass of dilated longitudinal vessels with a variceal configuration

was found, originating from the endocervix and protruding up to the

external cervical os, extending mainly toward the posterior

cervical margin (Fig. 3).

Scientific evidence supporting the optimal

management of bleeding caused by cervical varices in pregnancy is

still lacking. The limitation of physical activity, bed rest,

avoidance of sexual intercourse and blood transfusions in cases

where bleeding is accompanied by symptoms of anemia, such as

weakness, orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, or dyspnea are common

conservative therapeutic interventions (12). Additionally, the application of a

cervical pessary is another conservative option to control bleeding

associated with cervical varices during pregnancy. It is believed

that the pressure exerted by the pessary on the cervical tissues

may reduce the width of the varices, thus decreasing the bleeding

caused by their rupture (14).

Furthermore, cervical cerclage can be successfully applied to treat

cervical varicose veins in pregnant women and can lead to a

successful full-term pregnancy, even when applied in cases of

active bleeding from the rupture of cervical varices, as performed

by Poliektov and Kahn (5). The case

described herein differs in the fact that there was no time to

perform conservative measures, since massive bleeding was triggered

only by the attempt to examine the cervix. It is very likely that

any operative maneuvers in the area, such as cervical cerclage,

would also trigger massive bleeding. In cases where a decision is

made to terminate the pregnancy in the first or second trimester,

prophylactic embolization of the uterine artery is considered to

markedly reduce the risk of bleeding from cervical varices, such as

the case described by Lesko et al (15). In the patient in the present study,

the decision to terminate the pregnancy was an emergency medical

option due to massive vaginal bleeding caused by palpation of the

cervical varices. The severe vaginal bleeding in the case in the

present study left no room for consideration of conservative

methods for managing cervical varices, which may have allowed for

the continuation of the pregnancy and its termination by planned

cesarean section or vaginal delivery. The management course used

herein is similar to the one followed in the study by Kumazawa

et al (16), who managed

their case by mechanical pressure of the bleeding varices via

vaginal packing. In their case, mechanical pressure was effective

in stopping the bleeding and prolonging pregnancy for a few more

days, with emergency caesarean section being ultimately performed

(16), similar to the case described

herein. However, the case in the present study differs, as it

demonstrates a more clinically challenging scenario, whereby the

bleeding from varicose veins could not be controlled via mechanical

pressure, leading to the performance of emergency caesarean section

earlier during gestation and allowing no margins to attempt other

conservative treatment options to control the bleeding.

A planned cesarean section is still the preferred

mode of delivery for pregnant women with cervical varices. A

planned cesarean section avoids the rupture of cervical varices and

the triggering of massive vaginal bleeding that can occur during

vaginal delivery (17). A planned

vaginal delivery may be appropriate in isolated cases of cervical

varices, in which the varices may resolve simultaneously with the

separation of a coexisting placenta previa (6,18).

Emergency cesarean section, either associated with or without

emergency hysterectomy, is indicated in cases of massive,

uncontrolled bleeding and is associated with significantly

increased rates of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality

(19).

The prognosis is favorable in asymptomatic pregnant

women without bleeding from ruptured cervical varices. Following

the delivery of the fetus, cervical varices resolve spontaneously,

and the risk of recurrence is considered to be low (12). In cases where the rupture of cervical

varices occurs, the bleeding is severe and life-threatening for

both the pregnant woman and the newborn (20). In the patient described herein, the

profuse vaginal bleeding caused by rupture of the cervical varices

resulted in the loss of the fetus after the pregnancy was

terminated by performing a cesarean section. In both the immediate

and late post-operative periods, the findings from clinical

examination and transvaginal Doppler ultrasonography were

normal.

The primary strength of the present case report is

its rarity in the clinical setting, thus its addition to the

literature provides further insight into a lesser known clinical

entity and its management. However, there are limitations that need

to be acknowledged. Namely, the availability of only a single case

somewhat limits the generalizability and applicability of our

findings and conclusions in different clinical settings. Finally,

the absence of long-term follow-up, particularly up to a second

pregnancy and the exploration of recurrence is an additional

limitation that should be acknowledged. The individualization of

diagnostic and treatment approach based on the circumstances of

each patient and the available resources and expertise at hand is

key in achieving the most favorable outcomes.

In conclusion, cervical varices are an extremely

rare clinical entity. The rupture of cervical varices, leading to

massive vaginal bleeding in the second trimester of pregnancy,

often necessitates the termination of the pregnancy via cesarean

section. Cervical varices, particularly when associated with

placenta previa, should be considered in the differential diagnosis

of painless vaginal bleeding in pregnant women. The careful and

skilled use of transvaginal Doppler ultrasonography is deemed to be

invaluable for the early and accurate diagnosis of cervical

varices. Early detection can prevent unnecessary diagnostic

procedures, such as the digital palpation of the cervix, which may

otherwise result in variceal rupture, severe hemorrhage and fetal

loss.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in the current study are available

from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

AT and ET participated in the conception and design

of the study and international literature search. IRA and AL were

involved in the conception and design of the study, in the

provision of study materials (such as blood tests, culture test and

imaging) or patient data, in data collection and aggregation and

data analysis and interpretation. IT was involved in the conception

and design of the study, in administrative support, in patient

care, in data collection, in manuscript writing and analysis and

had overall supervision of the manuscript. All authors participated

in the writing of the manuscript, contributed to the revision of

the manuscript, and have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. All authors (AT, ET, IRA, AL and IT) confirm the

authenticity of all raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted according to the

guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent

was obtained from the patient.

Patient consent for publication

The patient in the present study provided signed

consent for the publication of her medical case anonymously and any

related images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Raetz J, Wilson M and Collins K: Varicose

veins: Diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 99:682–688.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ismail L, Normahani P, Standfield NJ and

Jaffer U: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk for

development of varicose veins in women with a history of pregnancy.

J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 4:518–524.e1. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gavrilov SG: Vulvar varicosities:

Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Int J Womens Health.

9:463–475. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Giannella L, Montanari M, Delli Carpini G,

Di Giuseppe J and Ciavattini A: Huge vulvar varicosities in

pregnancy: Case report and systematic review. J Int Med Res.

50(3000605221097764)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Poliektov N and Kahn BF: Bleeding cervical

varices in pregnancy: A case report and review of the literature. J

Neonatal Perinatal Med. 15:195–202. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wax JR, Cartin A, Litton C, Conroy K and

Pinette MG: Cervical varices: An unusual source of first-trimester

hemorrhage. J Clin Ultrasound. 46:218–221. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tanaka M, Matsuzaki S, Kumasawa K, Suzuki

Y, Endo M and Kimura T: Cervical varix complicated by placenta

previa: A case report and literature review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res.

42:883–889. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Thorp JM Jr, Fowler WC, Donehoo R, Sawicki

C and Bowes WA Jr: Antepartum and intrapartum events in women

exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Obstet Gynecol. 76:828–832.

1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yoshimura K, Hirsch E, Kitano R and

Kashimura M: Cervical varix accompanied by placenta previa in twin

pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 30:323–325. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Youssef J, Afolayan V, Mack M and Sze A:

Cervical varicosities, an uncommon cause of third-trimester

bleeding in pregnancy: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health.

38(e00507)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kurihara Y, Tachibana D, Teramae M,

Matsumoto M, Terada H, Sumi T, Koyama M and Ishiko O: Pregnancy

complicated by cervical varix and low-lying placenta: A case

report. Jpn Clin Med. 4:21–24. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Peng MY, Ker CR, Lee YS, Ho MC and Chan

TF: Cervical varices unrelated to placenta previa as an unusual

cause of antepartum hemorrhage: A case report and literature

review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 57:755–759. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kusanovic JP, Soto E, Espinoza J, Stites

S, Gonçalves LF, Santolaya J, Nien JK, Erez O, Sorokin Y and Romero

R: Cervical varix as a cause of vaginal bleeding during pregnancy:

Prenatal diagnosis by color Doppler ultrasonography. J Ultrasound

Med. 25:545–549. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

González-Bosquet E, Grau L,

Ferrero-Martínez S, Hernandez-Saborit A, Rebollo M, Gomez-Chiari M,

Martínez Crespo JM and Gómez-Roig MD: Pessary for management of

cervical varices complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol.

138:482–486. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lesko J, Carusi D, Shipp TD and Dutton C:

Uterine artery embolization of cervical varices before

second-trimester abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 123 (2 Suppl

2):S458–S462. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kumazawa Y, Shimizu D, Hosoya N, Hirano H,

Ishiyama K and Tanaka T: Cervical varix with placenta previa

totalis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 33:536–538. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sammour RN, Gonen R, Ohel G and Leibovitz

Z: Cervical varices complicated by thrombosis in pregnancy.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 37:614–616. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wong CK, Hung CMW, Ng VKS, Yung WK, Leung

WC and Lau WL: Four cases of cervical varices without placenta

praevia: Presentation, diagnosis, managements, and literature

review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 48:1997–2004. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Saedi N, Ghaemi M, Moghadam M, Haddadi M,

Hashemi Z and Hantoushzadeh S: Emergency postpartum hysterectomy as

a consequence of cervical varix during pregnancy; a case report and

literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 108(108425)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Park JE, Kim MJ, Kim MK and Kim HM:

Cervical varix with thrombosis diagnosed in the first trimester of

pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 62:65–68. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|