Introduction

Subphrenic abscesses are collections of infected

fluid located beneath the diaphragm, typically in the space between

the diaphragm and the upper abdominal organs. These abscesses are

anatomically bordered inferiorly by the transverse colon, mesocolon

and greater omentum (1). Although

they are relatively uncommon, subphrenic abscesses are clinically

significant and often arise as complications of intra-abdominal

infections following surgery, trauma or immunosuppression (2). When typical risk factors are absent,

the diagnosis and management of subphrenic abscesses can be more

complex.

The causative pathogens differ by the type of

surgery, with Staphylococcus aureus infection being common

following gastric procedures and Bacteroides fragilis and

Clostridium species infections being more common following

colon surgery or appendicitis (2).

However, Proteus mirabilis (P. mirabilis), a

Gram-negative bacterium typically associated with urinary tract

infections, is a rare cause of subphrenic abscesses and is

particularly uncommon among immunocompetent patients.

The management of subphrenic abscesses requires a

tailored approach, particularly when atypical or drug-resistant

pathogens are involved. The present study describes a rare case of

an immunocompetent patient with subphrenic abscess caused by P.

mirabilis, without the usual risk factors (3). The prolonged 2-year course and

multidrug-resistant nature of the infection made both diagnosis and

treatment particularly challenging.

The case presented herein underscores the importance

of comprehensive diagnostic imaging and culture-directed antibiotic

therapy in the management of such infections. It further highlights

the critical role of timely intervention, including percutaneous

drainage and the judicious use of antibiotics, to achieve favorable

clinical outcomes in cases involving rare and resistant

pathogens.

Case report

A 77-year-old male patient presented for an

outpatient evaluation by an internist at New Hospitals (Tbilisi,

Georgia), with a 2-year history of recurrent febrile episodes, with

temperatures ranging from 37 to 39˚C, partially alleviated by

acetaminophen and ibuprofen. The fever was accompanied by

generalized weakness, nausea and vertigo. At 1 month prior to the

presentation, the patient developed a nocturnal spasmodic cough

producing white sputum.

His medical history was notable for an episode of

community-acquired pneumonia 2 years prior, complicated by

pleuritis and a right-sided pleural effusion. The pleural fluid was

exudative, with an adenosine deaminase level of 56 U/l. No specific

infectious agent was identified as a cause of pneumonia.

Tuberculosis was ruled out with interferon gamma release assay. The

condition was managed with moxifloxacin and prednisone.

The patient was also treated for a lower urinary

tract infection 2 months prior. At 13 years prior to this, he had

undergone surgical repair for an abdominal aortic rupture, and 5

years prior, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy had been performed.

At the time of the presentation, the vital signs of

the patient were as follows: A temperature of 37.7˚C, heart rate of

65 beats per minute, blood pressure of 130/70 mmHg, respiratory

rate of 22 breaths per minute and an oxygen saturation of 95% in

room air. A physical examination yielded no significant

findings.

Laboratory investigations demonstrated the

following: A red blood cell count of 3.92x106/µl,

hemoglobin level of 10.4 g/dl, mean corpuscular volume of 78.6 fl,

a platelet count of 354x103/µl, white blood cell count

of 22.09x103/µl, neutrophil count of

18.83x103/µl and a lymphocyte count of

1.39x103/µl. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH

of 7.41, partial pressure of carbon dioxide level of 41 mmHg, a

sodium level of 135 mmol/l, a potassium level of 4.3 mmol/l, a

calcium level of 1.14 mmol/l, a glucose level of 111 mg/dl, a

lactate level of 1.7 mmol/l and a bicarbonate level of 26

mmol/l.

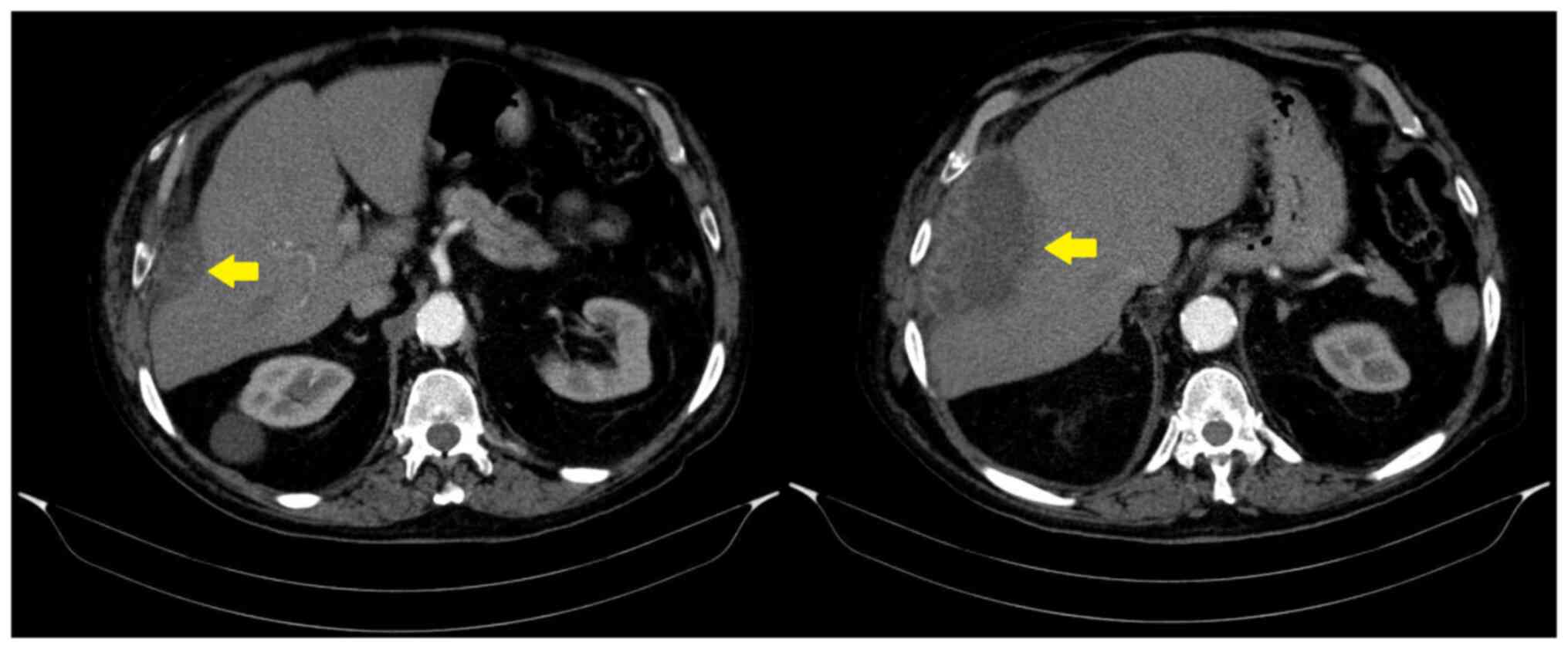

Given the persistent fever of unknown origin, a

chest computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which revealed a

subphrenic abscess (Fig. 1). To aid

in diagnosis and intervention, an 18 G puncture needle was

initially used to aspirate the abscess and collect a specimen for

analysis. Subsequently, a 12CH pigtail catheter was inserted to

enable continuous drainage and facilitate abscess lavage with

saline four times daily, following local hospital protocols.

The aspirate analysis revealed pinkish-yellow,

turbid, exudative fluid with a high lactate dehydrogenase level of

678 U/l (normal range, 140-280 U/l), an elevated leukocyte count

(normal value, <500 cells/µl) and a predominance of lymphocytes

at 82% (normal value, <50%), while polymorphonuclear cells

accounted for 18% (normal value >50%).

A specimen biopsy was obtained for microscopy and

immunohistochemistry due to concerns about possible malignancy.

These analyses were performed at the Pathology Laboratory of New

Hospitals, and as per routine local practice, only the final report

was provided without image documentation. Microscopy revealed

fibrous and hyalinized stroma with the infiltration of white blood

cells. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated CD3-, CD20- and

PAX5-positive lymphocytes; CD38-positive plasma cells;

CD68-positive macrophages; and CD15-positive granulocytes. CD30, a

lymphoma marker, was negative, thereby excluding an underlying

malignant etiology.

Bacteriological analysis of the aspirated fluid

identified P. mirabilis revealed resistance to gentamicin,

imipenem, cefotaxime, cefazolin, trimethoprim

(TMP)/sulfamethoxazole (SMX), amoxicillin/clavulanate and

tigecycline based on phenotypic testing, while it revealed

sensitivity to fluoroquinolones, tobramycin, amikacin, meropenem,

ceftazidime, cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam. Genotypic

resistance testing [e.g., for extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)

or carbapenemase genes] was not performed. Immunohistochemical

analysis revealed inflammation without any evidence of

malignancy.

During hospitalization, the patient was commenced on

empirical treatment with IV meropenem, administered at 2 g every 8

h for 2 weeks. Following the antibiotic sensitivity report, which

revealed susceptibility to fluoroquinolones, the treatment was

adjusted to IV moxifloxacin, at 400 mg once daily, for the

following 6 weeks. This de-escalation was guided by antimicrobial

stewardship principles to reduce unnecessary carbapenem use, once

effective narrower-spectrum therapy was identified. Moxifloxacin

was selected due to its confirmed activity against the isolated

P. mirabilis strain and its excellent intra-abdominal tissue

penetration, which is essential for treating deep-seated

infections, such as subphrenic abscesses (4). Maintaining IV administration ensured

consistent therapeutic levels in this elderly patient during

prolonged treatment.

The patient was closely monitored through regular

follow-up visits over a 6-month period. He remained afebrile and

symptom-free throughout this period, with no recurrence of

abdominal pain, respiratory symptoms, or signs of systemic

infection. Serial laboratory investigations, including analyses of

complete blood count and C-reactive protein levels, yielded results

which were within the normal limits. A follow-up abdominal

ultrasound performed at 3 and 6 months post-discharge revealed the

complete resolution of the abscess, with no residual fluid

collection or new abnormalities. As per local clinical practice,

ultrasound images were not archived or provided to the referring

physician. The patient did not require further antibiotic therapy

and returned to his usual daily activities without restrictions. No

late complications or relapses were reported.

Discussion

A subphrenic abscess, also referred to as a

subdiaphragmatic or infra-diaphragmatic abscess, is characterized

by a localized collection of pus in the subphrenic space. Although

rare, its exact incidence remains unclear. The condition is

typically unilateral, most often occurring on the right side in

~50% of cases, with 40% on the left side and 25% presenting

bilaterally (1-3,5).

In rare instances, both intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal

involvement may be observed, as was the case of the patient

described herein, who presented with a right-sided subphrenic

abscess exhibiting both forms of involvement (5).

Subphrenic abscesses most commonly arise from the

introduction of bacteria into the subphrenic space. Secondary

subphrenic abscesses are most frequently associated with gastric

and biliary surgeries, accounting for 52% of cases. Appendicitis is

responsible for 8%, while colonic surgery and trauma contribute to

19 and 8%, respectively (6).

Localized inflammation in the space between the liver, intestines,

and lungs can also serve as a cause of subphrenic abscess (2). The diagnosis is often delayed or missed

when the abscess is not related to surgery. The majority cases

appear within weeks of abdominal surgery, though some may present

as late as 5 months post-operatively (7). Although the patient in the present

study had a history of intra-abdominal surgeries, including

abdominal aortic aneurysm repair 13 years prior and laparoscopic

cholecystectomy 5 years prior, the timing of these procedures did

not coincide with the onset of symptoms, making them unlikely

contributors to the subphrenic abscess. The source of the P.

mirabilis infection remains uncertain. However, it is plausible

that a prior episode of pneumonia, complicated by a right-sided

pleural effusion ~2 years prior, played a role. Despite the absence

of pathogen isolation from the pleural fluid at that time, the

anatomical proximity between the pleural cavity and subphrenic

space suggests the possibility of transdiaphragmatic spread.

Additionally, while P. mirabilis is not typically associated

with subphrenic abscesses, it has been documented as a causative

agent in various deep-seated infections in susceptible individuals,

which may support its role as a potential source in this case

(8-14).

While transdiaphragmatic extension from the prior

pleural effusion remains the most plausible explanation, other

potential routes of infection were also considered. These include

hematogenous spread, gastrointestinal translocation, or

reactivation from previous abdominal surgery. However, the patient

had no evidence of bacteremia, gastrointestinal symptoms, or recent

surgical intervention to support these mechanisms. Therefore, the

precise route of P. mirabilis entry remains speculative.

Although a causal link remains unclear, this assumption should be

viewed in light of diagnostic limitations during the earlier

pneumonia episode. In Georgia, routine microbiological testing,

such as bronchoalveolar lavage or pleural fluid culture, is not

commonly performed for community-acquired pneumonia unless the case

is severe or atypical. As a result, no causative organism was

identified at that time. The pleural effusion was unilateral and

exudative, making alternative causes such as cardiac origin less

likely. These limitations reduce diagnostic certainty and are

common in resource-limited settings, where comprehensive microbial

workup is not always feasible. Nevertheless, the timing, anatomical

proximity, and clinical context make a transdiaphragmatic

infectious process a reasonable consideration.

Previous studies indicate that subphrenic abscesses

are often polymicrobial, with aerobic bacteria, such as

Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp.,

Enterobacter and Staphylococcus aureus being the

predominant isolates. The most common anaerobes include

Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides fragilis,

Clostridium spp. and Prevotella. Following biliary

surgery, Enterococcus group D infection predominates, while

infections with Fusobacterium and Prevotella species

are common following gastric or duodenal surgery (15). Notably, the case stands out due to

the isolation of P. mirabilis from the abscess aspirate, a

rare finding in subphrenic abscesses.

P. mirabilis belongs to the Proteus

genus, which includes five named species (P. mirabilis,

Proteus penneri, Proteus vulgaris,

Proteusmyxofaciens and Proteus hauseri) and several

unnamed (Proteus 4,5,6) genomospecies (16). Although P. mirabilis is a

common Gram-negative pathogen in clinical settings, it is not

typically associated with severe infections and is more frequently

found in colonizing wounds (17).

However, in immunocompromised individuals, it may cause systemic

infections, including urinary tract infections, biliary infections,

wound infections and peritonitis (17). While P. vulgaris is commonly

identified as a causative agent of visceral intra-abdominal

abscesses, P. mirabilis has been reported as a pathogen in

abscesses of the intracranial region, lungs, kidneys and liver,

breast, iliopsoas muscle (8-14).

However, there is a paucity of detailed reports on P.

mirabilis in subphrenic abscesses, with the majority of reports

focusing on its prevalence rather than its precise role or

characteristics, which renders the present case report particularly

significant (6,8,10,11,13,17,18).

Moreover, the patient described herein immunocompetent and had no

history of nephrolithiasis, which is commonly associated with P.

mirabilis, raising questions about how the pathogen contributed

to the abscess.

The present case report is notable when compared to

other documented instances of P. mirabilis causing abscesses

in atypical locations. For example, P. mirabilis was

previously reported in a 17-year-old patient with an intracranial

abscess, causing rare neurological symptoms, such as seizures and

altered sensorium in an immunocompetent patient (9). Similarly, P. mirabilis was

previously identified in a breast abscess in a 56-year-old female

patient, which is unusual, as breast abscesses are typically caused

by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus spp

(8). Additionally, P.

mirabilis has been found in iliopsoas muscle abscesses, a site

usually affected by Escherichia coli or Staphylococcus

aureus, further highlighting the atypical role of this pathogen

in deep-seated infections (11). In

neonatal cases, P. mirabilis has even been implicated in

brain abscesses, an uncommon occurrence given that such infections

are typically caused by Streptococcus and

Staphylococcus species (10).

By contrast, subphrenic abscesses are often

polymicrobial, and the isolation of P. mirabilis as the sole

pathogen, as in the case in the present study, is highly unusual,

particularly in an immunocompetent patient without the typical

predisposing factors, such as recent surgery, urinary tract

infection, or nephrolithiasis (15).

Therefore, the present case report adds valuable insight into the

understanding of P. mirabilis and its unusual involvement in

abscesses outside its typical pathogenetic scope, particularly in

the absence of common predisposing conditions. The case described

herein also underscores the need to consider this pathogen in the

differential diagnosis of deep-seated infections, even in patients

with no notable past medical history.

Typically, P. mirabilis is intrinsically

resistant to nitrofurantoin and tetracycline, while remaining

susceptible to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones and

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, in this instance, the

isolated strain exhibited multidrug resistance, including

resistance to gentamicin, imipenem, cefotaxime, cefazolin, TMP/SMX,

amoxicillin/clavulanate and tigecycline. This posed a significant

challenge in selecting an effective antibiotic regimen, as

multidrug-resistant P. mirabilis infections complicate the

management of deep-seated infections such as subphrenic abscesses

(16,17). The resistance of P. mirabilis

to β-lactams, aminoglycosides and quinolones has been increasingly

reported in clinical isolates, raising concerns about the

effectiveness of these agents in treating infections caused by an

ESBL-producing strain (18). As a

result, carbapenems, such as meropenem, have become the drug of

choice for empirical therapy, particularly when resistant strains

are suspected (19). In the case in

the present study, meropenem was initiated as an empiric therapy

for the subphrenic abscess, and the isolate was found to be

sensitive to it, allowing for effective initial management and

resolution of the infection. This highlights the continued

relevance of carbapenems as a critical therapeutic option, despite

the growing resistance patterns seen in P. mirabilis (20). However, the increasing frequency of

resistance to key antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones,

aminoglycosides and β-lactams, underscores the need for alternative

therapeutic approaches, particularly in patients with infections

caused by multidrug-resistant strains.

The clinical presentation of a subphrenic abscess

can vary depending on its anatomical location. Symptoms often

include fever, pain in the upper abdomen or shoulder, costal margin

tenderness, abdominal tenderness and dyspnea (2). Additionally, it may present with cough,

hiccups, or unexplained pulmonary manifestations such as pneumonia,

pleural effusion, or basal atelectasis (2), as observed in the patient in the

present study. Fever of unknown origin is also a common symptom

(2).

If not treated promptly, patients may develop

systemic inflammatory response syndrome, characterized by

tachycardia, hypotension and oliguria, which can ultimately

progress to multiorgan failure and mortality (2). Notably, the patient in the present

study appeared to have had this condition for ~2 years without

developing such severe complications, renderings this case

particularly unusual. This prolonged clinical course raises the

question of why the abscess remained undiagnosed for such a long

period of time. During this period, the patient experienced

intermittent febrile episodes; however, no cross-sectional imaging

was performed, as he declined CT scans due to personal reluctance.

This hindered early diagnostic evaluation and contributed to a

delayed identification of the evolving deep-seated pathology. The

subphrenic abscess was only detected after clinical deterioration

prompted urgent imaging.

Laboratory findings typically include leukocytosis

with neutrophilia and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

(2). Blood gas analysis may

initially reveal respiratory alkalosis due to hyperventilation,

which can progress to metabolic acidosis if left untreated

(2). Blood cultures showing

polymicrobial growth are highly suggestive of subphrenic abscess

(2).

Imaging plays a pivotal role in diagnosing

subphrenic abscesses and guiding management decisions. Chest X-rays

may reveal diaphragmatic elevation, pleural effusion, or lung

abnormalities (2,21). In the case described herein, a chest

X-ray performed 7 months prior incidentally revealed a small

right-sided pleural effusion. The development of pleural effusion

in association with a subphrenic abscess is considered to result

from diaphragmatic inflammation, increasing capillary permeability

and leading to the accumulation of pleural fluid.

Abdominal ultrasound is commonly used for initial

detection, particularly for right-sided abscesses, due to its high

sensitivity for fluid collections and real-time imaging

capabilities. It aids in the assessment of abscess size and

location, and is particularly useful for guiding percutaneous

drainage. However, the limitations of an ultrasound include reduced

efficacy for left-sided abscesses due to bowel gas interference,

and its operator-dependence, meaning the quality of results can

vary. Additionally, ultrasound may not be able to visualize deep or

complex abscesses (22,23). When ultrasound is inconclusive or for

left-sided abscesses, contrast-enhanced CT is considered the gold

standard. CT provides detailed cross-sectional images that allow

for precise localization of the abscess, assessment of surrounding

structures, and planning of drainage procedures. It is particularly

beneficial for left-sided abscesses, where ultrasound is less

effective. However, CT does involve radiation exposure and may not

be as readily accessible in all clinical settings (24,25). In

cases of deep or challenging abscesses, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

can be used to access difficult-to-reach areas, offering real-time

imaging and minimizing the risk of intervening structures during

drainage. While EUS provides a valuable alternative, it is

invasive, requires specialized skills, and is not universally

available (26,27).

The management of a subphrenic abscess typically

involves antibiotic therapy and drainage. Empiric therapy with

broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated immediately to cover

both aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Once culture results are

available, the antibiotics should be adjusted accordingly. In

immunocompromised patients, antifungal coverage may also be

necessary, particularly for Candida species (2). For drainage, percutaneous CT-guided

drainage is considered the gold standard due to its high success

rate, minimal invasiveness, and lower complication rates compared

to surgical drainage. It allows for real-time visualization and

avoids the need for general anesthesia, which is particularly

beneficial for elderly patients with multiple comorbidities.

CT-guided drainage is effective in controlling sepsis and can be

used both for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes (28,29).

If percutaneous drainage is unsuccessful or if the

abscess is loculated, surgical drainage may be required.

Laparoscopic drainage is less invasive than open surgery and allows

for direct visualization and drainage of the abscess. However, if

laparoscopic methods fail, open surgery may be necessary, although

this approach carries more risks, such as injury to surrounding

organs. In severe cases, particularly in trauma or abdominal

compartment syndrome, open abdomen therapy may be employed as a

damage control strategy. Timely drainage and appropriate antibiotic

therapy are crucial for preventing sepsis, and intensive care may

be required for patients who develop multiorgan failure (30).

In conclusion, the present case report underscores

the uncommon presentation of a subphrenic abscess caused by P.

mirabilis in an immunocompetent patient without typical risk

factors or a clear timeline linking the infection to prior surgical

interventions. The prolonged 2-year symptom duration, the absence

of severe complications, and the multidrug-resistant nature of the

isolated strain posed significant diagnostic and therapeutic

challenges. This highlights the critical role of comprehensive

diagnostic imaging and culture-guided therapy in managing complex

and atypical abscesses. Early, decisive interventions, such as

percutaneous drainage combined with the strategic use of advanced

antibiotics such as meropenem, proved instrumental in achieving a

successful outcome. The case described herein emphasizes the need

for heightened clinical awareness, meticulous treatment planning

and adaptability in addressing rare, resistant infections

effectively.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LC and EC contributed to reviewing the patient's

medical chart, processing images and drafting the manuscript. LC

specifically focused on the case description, while EC led the

discussion section. NK, an internal medicine physician, was

responsible for the patient's management, including examination,

diagnosis, postoperative care, and follow-up. NK also provided all

the necessary data for manuscript preparation and participated in

the revision of the final manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript. LC, EC and NK confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was not required for this

single-patient case report in accordance with local institutional

policies. However, all ethical principles outlined in the

Declaration of Helsinki were followed. Particular care was taken to

protect the patient's privacy, and all potentially identifying

details have been omitted. Informed consent was obtained from the

patient described herein. The present case report has removed all

identifying information to protect patient privacy.

Patient consent for publication

Informed consent for the publication of the present

case report was obtained from the patient. The present case report

has removed all identifying information to protect patient

privacy.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Carter R and Brewer LA III: Subphrenic

Abscess: A Thoracoabdominal Clinical Complex: The Changing Picture

with Antibiotics. Am J Surg. 108:165–174. 1964.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ravi GK and Puckett Y: Subphrenic Abscess.

In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL,

2024.

|

|

3

|

Jamil RT, Foris LA and Snowden J: Proteus

mirabilis Infections. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing,

Treasure Island, FL, 2024.

|

|

4

|

Rink AD, Stass H, Delesen H, Kubitza D and

Vestweber KH: Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of

moxifloxacin in intervention therapy for intra-abdominal abscess.

Clin Drug Investig. 28:71–79. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

DeCrosse JJ, Poulin TL, Fox PS and Condon

RE: Subphrenic abscess. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 138:841–846.

1974.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang SM and Wilson SE: Subphrenic Abscess:

The new epidemiology. Arch Surg. 112:934–936. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Karki A, Riley L, Mehta HJ and Ataya A:

Abdominal etiologies of pleural effusion. Dis Mon. 65:95–103.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Parnasa E, Cohen A, Avital B, Parnasa YS

and Oster Y: An unusual case of breast abscess caused by Proteus

mirabilis and Prevotella buccalis. J Clin Images Med Case Rep.

2(1406)2021.

|

|

9

|

Muddassir R, Khalil A, Singh R, Taj S and

Khalid Z: Intracranial abscess and proteus mirabilis: A case report

and literature review. Cureus. 12(e12326)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chung MH, Kim G, Han A and Lee J: Case

report of neonatal proteus mirabilis meningitis and brain abscess

with negative initial image finding: Consideration of serial

imaging studies. Neonatal Med. 24:187–191. 2017.

|

|

11

|

Moskaļenko KJ, Aveniņa S, Jeršovs K,

Malzubris M and Golubovska I: Iliopsoas muscle abscess and Proteus

mirabilis caused sepsis: a case report. Int J Sci Rep. 9:1–4.

2023.

|

|

12

|

Umar BM: Intraabdominal Abscesses. In:

Abscess-Types, Causes and Treatment. IntechOpen, London, 2024.

Accessed on January 3, 2025.

|

|

13

|

Kakuchi Y: Multiple renal abscesses due to

Proteus mirabilis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 25:322–323. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Vakil N, Hayne G, Sharma A, Hardy DJ and

Slutsky A: Liver abscess in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol.

89:1090–1095. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Frazier EH: Microbiology of subphrenic

abscesses: a 14-year experience. Am Surg. 65:1049–1053.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

O'Hara CM, Brenner FW and Miller JM:

Classification, identification, and clinical significance of

proteus, providencia, and morganella. Clin Microbiol Rev.

13:534–546. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wu JJ, Chen HM, Ko WC, Wu HM, Tsai SH and

Yan JJ: Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Proteus

mirabilis in a Taiwanese university hospital, 1999 to 2005:

Identification of a novel CTX-M enzyme (CTX-M-66). Diagn Microbiol

Infect Dis. 60:169–175. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Valentin T, Feierl G, Masoud-Landgraf L,

Kohek P, Luxner J and Zarfel G: Proteus mirabilis harboring

carbapenemase NDM-5 and ESBL VEB-6 detected in Austria. Diagn

Microbiol Infect Dis. 91:284–286. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bedenić B, Pospišil M, Nad M and Pavlović

DB: Evolution of β-Lactam Antibiotic Resistance in Proteus Species:

From Extended-Spectrum and Plasmid-Mediated AmpC β-Lactamases to

Carbapenemases. Microorganisms. 13(508)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Alqurashi E, Elbanna K, Ahmad I and

Abulreesh HH: Antibiotic Resistance in Proteus mirabilis:

Mechanism, Status, and Public Health Significance. J Pure Appl

Microbiol. 1–12. 2022.

|

|

21

|

Saha A, Chakraborty R, Sain B, Basak S and

Saha S: A Case of Bilateral Subphrenic Abscess Mimicking Bilateral

Postoperative Pleural Effusion. Bengal Phys J. 9:68–72. 2023.

|

|

22

|

Shavrina NV, Ermolov AS, Yartsev PA,

Kirsanov II, Khamidova LT, Oleynik MG and Tarasov SA: [Ultrasound

in the diagnosis and treatment of abdominal abscesses]. Khirurgiia

(Mosk). (11):29–36. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Russian).

|

|

23

|

Cho KH, Jung KH, Hwang MS, Chang JC, Kwun

KB and Min HS: Ultrasonographic Features of Intra-abdominal

Abscess. J Yeungnam Med Sci. 2(87)1985.

|

|

24

|

Stevens C, Scott D, Ramesh P, Ragland A,

Johnson C, Strobel J, Malone K, D'Agostino H, Ahuja C and De Alba

L: The evolution of percutaneous abdominal abscess drainage: A

review. Medicine (Baltimore). 104(e41799)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Fry DE: Noninvasive imaging tests in the

diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal abscesses in the

postoperative patient. Surg Clin North Am. 74:693–709.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu S, Tian Z, Jiang Y, Mao T, Ding X and

Jing X: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage to abdominal abscess:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minimal Access Surg.

18:489–496. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

De Filippo M, Puglisi S, D'Amuri F,

Gentili F, Paladini I, Carrafiello G, Maestroni U, Del Rio P,

Ziglioli F and Pagnini F: CT-guided percutaneous drainage of

abdominopelvic collections: A pictorial essay. Radiol Med.

126:1561–1570. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Betsch A, Wiskirchen J, Trübenbach J,

Manncke KH, Belka C, Claussen CD and Duda SH: CT-guided

percutaneous drainage of intra-abdominal abscesses: APACHE III

score stratification of 1-year results. Acute Physiology, Age,

Chronic Health Evaluation. Eur Radiol. 12:2883–2889.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Hemming A, Davis NL and Robins RE:

Surgical versus percutaneous drainage of intra-abdominal abscesses.

Am J Surg. 161:593–595. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Mazuski JE, Tessier JM, May AK, Sawyer RG,

Nadler EP, Rosengart MR, Chang PK, O'Neill PJ, Mollen KP, Huston

JM, et al: The surgical infection society revised guidelines on the

management of intra-abdominal infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt).

18:1–76. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|