Introduction

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) pose a

significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide (1). According to epidemiological data, ARIs

account for 20-40% of outpatient visits and 12-35% of hospital

admissions in general healthcare settings (2). Pulmonary infections remain a leading

cause of infant and childhood mortality, contributing to ~15% of

all deaths among children <5 years of age globally (3,4). A

previous cohort study estimated the incidence of ARIs at 1.8

episodes per infant per year, with upper respiratory infections

comprising 95% of the cases (5).

The primary causes of ARIs in infants and young

children include a variety of viral and bacterial pathogens.

Viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza,

rhinovirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza and human metapneumovirus are

the most frequent causes of upper and lower respiratory tract

infections in early life. Bacterial pathogens, including

Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and

Staphylococcus aureus, are also implicated, particularly in

more severe or secondary infections. The ability of the host to

mount an effective immune response to these pathogens is essential

in preventing complications. Consequently, any factor that

compromises immune function during critical developmental windows,

such as prenatal exposure to environmental immunotoxins, could

potentially elevate the risk or severity of ARIs (6,7).

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

constitute a group of synthetic chemicals extensively utilized in

industrial and commercial applications since the mid-20th century.

These compounds serve as surfactants and repellents in various

products, including coatings for paper and packaging, textiles,

leather, firefighting foams, photographic materials, cleaning

products and pesticides (8-10).

Due to their widespread use, PFAS have led to extensive

environmental contamination on a global scale (10).

Human exposure to PFAS occurs through multiple

pathways, including the ingestion of contaminated water and food.

The highest concentrations have been detected in fish and

shellfish, followed by red meat, animal fats, processed snacks

(11,12) and beverages (13). Additionally, the inhalation and

ingestion of dust represent key exposure routes (14). The bioaccumulation of PFAS in the

bloodstream is directly proportional to the duration and level of

exposure (15).

The persistence of PFAS in the environment,

attributed to their chemical and thermal stability and high surface

activity, along with their prolonged biological half-life, raises

significant concerns regarding their potential impact on human

health (8,15,16).

Given their extensive use and resistance to degradation, PFAS have

achieved global geographic distribution, with notable variations in

exposure levels among different regions (15).

Furthermore, PFAS can cross the placental barrier

and be transferred into breast milk, representing primary exposure

sources for neonates (15). The

fetal and early postnatal periods are critical windows for immune

system development, increasing susceptibility to adverse effects

from environmental exposures (15).

Notably, prolonged breastfeeding has been associated with higher

PFAS concentrations in infants, underscoring the need to elucidate

the role of breastfeeding in the etiology of pediatric infectious

diseases (15).

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has

recently established tolerable intake levels for a subset of PFAS

based on their association with reduced antibody responses in

children and adults, aiming to mitigate potential health risks

(https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/pfas-food-efsa-assesses-risks-and-sets-tolerable-intake).

Despite increasing evidence of the toxicological effects of PFAS,

data on their impact on infant and childhood respiratory health

remain limited. Further research is essential to address this gap,

particularly concerning the association between alternative PFAS

compounds and respiratory infections in children, as research

focuses on conventional PFAS (17).

Recent evidence has highlighted that PFAS exposure,

particularly during critical periods such as gestation, may disrupt

normal immune development (18).

Several PFAS compounds have been shown to alter cytokine

production, reduce antibody responses to vaccines, and impair

immune cell function (18). Given

that respiratory infections are largely managed through innate and

adaptive immune responses, it is plausible that PFAS-induced

immunotoxicity during fetal development could predispose children

to developing more frequent or severe respiratory infections.

Despite this biologically plausible link, only a limited number of

studies have systematically investigated the association between

prenatal PFAS exposure and respiratory health outcomes in early

life (9-12).

The health implications of prenatal PFAS exposure

are of growing concern, particularly given accumulating evidence

linking PFAS to immunosuppression and altered vaccine responses in

children. However, the respiratory consequences of in utero

PFAS exposure remain inadequately characterized, despite

respiratory infections being a leading cause of global childhood

morbidity and mortality. The present systematic review addresses a

critical gap by systematically evaluating whether prenatal PFAS

exposure may increase susceptibility to respiratory infections

during infancy and early childhood, a period marked by immune

vulnerability. By clarifying these associations, the present study

aimed to inform public health strategies and regulatory policies

targeting maternal exposure to persistent environmental toxins.

Data and methods

The present study was conducted according to the

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

(PRISMA) guidelines (19). The

present systematic review has been registered in the International

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with ID no.

CRD420251001057.

Search strategy

A total of two independent reviewers conducted the

literature search and screened the titles and abstracts for

eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or

consultation with a third reviewer. A comprehensive literature

search was conducted across three major electronic databases:

PubMed/Medline, Scopus and the Cochrane Library. The search

strategy was designed to identify relevant studies examining

prenatal exposure to PFAS and their impact of the development of

respiratory infections in children. The search algorithm

incorporated a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH

terms) and free-text keywords related to PFAS, including

‘perfluoroalkyl’ ‘polyfluoroalkyl’ ‘perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)’

‘perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)’ ‘perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA)’

‘perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS)’ and ‘perfluorobutane sulfonate

(PFBS)’.

To ensure the identification of studies specifically

addressing prenatal exposure, the search strategy incorporated

terms such as ‘pregnancy’, ‘prenatal’, ‘gestational’, ‘maternal

exposure’ and ‘maternal blood levels’. Boolean operators (AND, OR)

were used to refine the search, and additional filters were applied

where applicable. To enhance the comprehensiveness of the

systematic review, reference lists of included studies were

manually screened for additional relevant articles.

In addition to the primary database search, grey

literature was considered to reduce potential publication bias,

i.e., the tendency for studies with statistically significant or

positive findings to be more likely published in indexed,

peer-reviewed journals. Sources of grey literature included

institutional repositories, governmental or non-governmental

organization-funded cohort reports, conference proceedings, and

preprint servers (e.g., medRxiv).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they focused on pregnant

women and women of reproductive age, assessed prenatal exposure to

PFAS, and compared outcomes between exposed and non-exposed

populations. The primary outcome of interest was the association

between prenatal PFAS exposure and infant or childhood respiratory

infections. Only primary research studies published in English were

considered. The timeframe for inclusion was restricted to studies

published between January 1, 2015, and February 1, 2025, and any

studies conducted outside this period were excluded.

The population, intervention,

comparator, outcomes and study design (PICOS) framework

The PICOS framework for the present systematic

review on prenatal exposure to PFAS and childhood respiratory

infections can be outlined as follows: i) Population (P): Pregnant

women and their offspring (infants and children); ii)

intervention/exposure (I): Prenatal exposure to PFAS, including

PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFHxS, perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA), etc.; iii)

comparison (C): Not applicable (no explicit comparison group in the

included studies); iv) outcome (O): Incidence of respiratory

infections in infancy and childhood, including pneumonia, RSV

infections, bronchitis, and other respiratory tract infections; and

v) study design (S): Observational studies (cohort, case-control,

and cross-sectional studies).

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest in the present

systematic review was the incidence of ARIs in infants and children

associated with prenatal exposure to PFAS. ARIs included upper and

lower respiratory tract infections, such as pneumonia, bronchitis,

RSV infection, the common cold and streptococcal throat infections,

as reported in the included studies.

Secondary outcomes included: i) The severity of

respiratory infections, where available (e.g., number of infection

episodes, presence of fever, co-occurrence of symptoms such as

cough or nasal discharge); ii) lung function parameters [e.g.,

forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in one second

(FEV1)]; c) Immune-related biomarkers, including

alterations in immune cell subpopulations and cytokine profiles;

and iv) hospitalization rates or clinical care utilization related

to respiratory infections, when reported.

PRISMA process

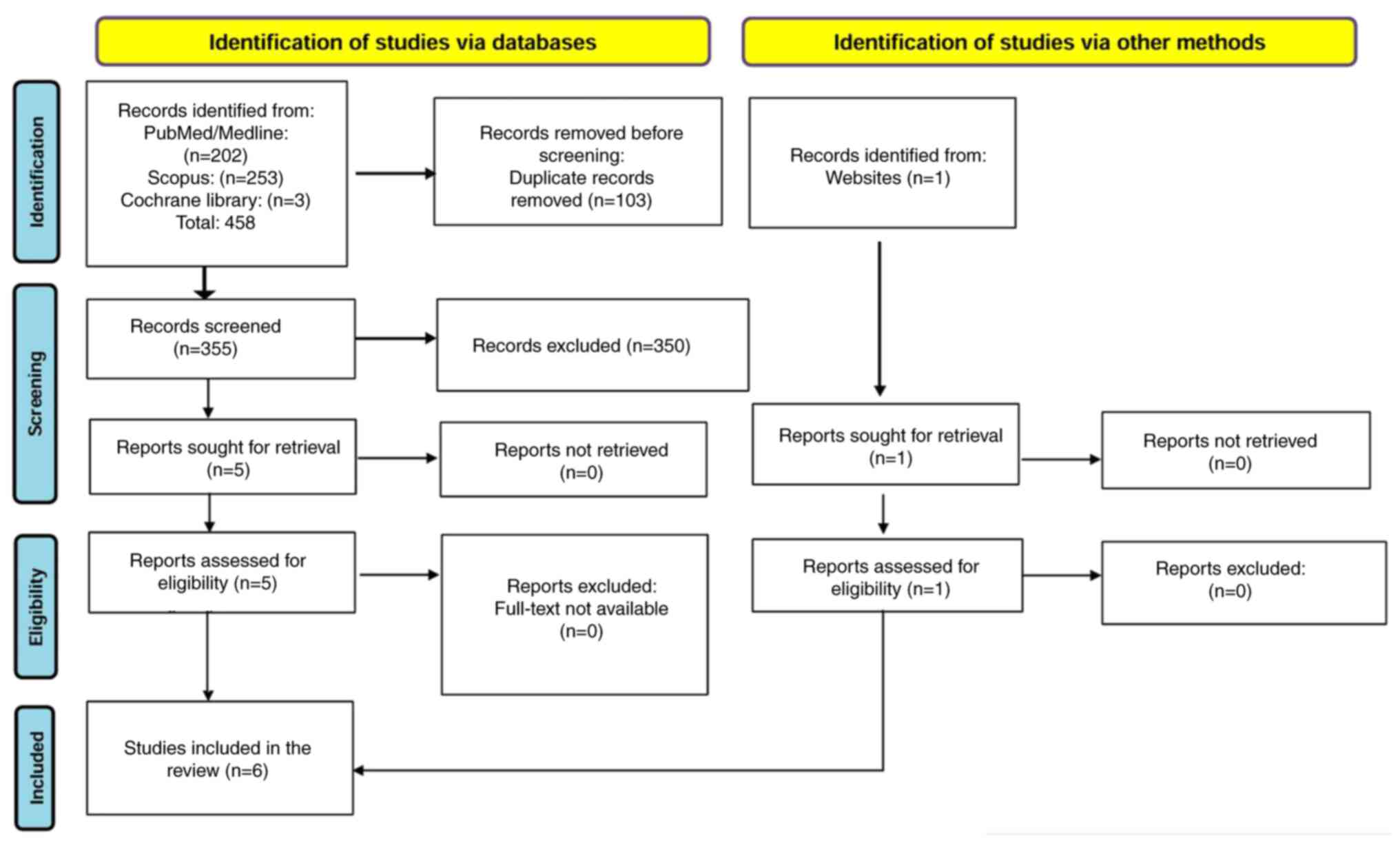

The initial search in the PubMed, Scopus and

Cochrane Library databases yielded 458 records. Of these, 202

records were identified in PubMed/Medline, 253 in Scopus and three

in the Cochrane Library. After removing 103 duplicate records, 355

unique records remained for further evaluation.

Each retrieved record underwent a detailed screening

process to identify the most relevant studies. The first stage

involved a review of titles and abstracts, eliminating studies that

did not align with the research question, specifically those

unrelated to the association between prenatal PFAS exposure and

infant or childhood respiratory infections. Following this initial

screening, 350 studies were excluded, leaving five studies eligible

for full-text review.

All five studies were retrieved in full text and

assessed for eligibility. Upon detailed examination, all five met

the inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis. One

additional relevant study, not retrieved from PubMed, Scopus, or

the Cochrane Library, was identified through a manual search of

reference lists and an institutional database. Although this record

was not originally indexed in a peer-reviewed journal, it met tge

inclusion criteria as a primary observational study with a defined

methodology and sufficient data transparency. A final dataset of

six studies were included in the present systematic review. The

entire selection process is visually represented in Fig. 1, depicting the identification,

screening, eligibility and final inclusion of studies.

Quality assessment

The selected studies underwent a quality assessment

based on the Caldwell framework, ensuring methodological rigor

(20). The results of quality

assessment are displayed in Data S1. The risk of bias and study

quality were assessed independently by two reviewers. Any

discrepancies in the quality assessment were discussed and resolved

through consensus.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two

reviewers using a standardized extraction form. Differences in data

interpretation were addressed through discussion or resolved by a

third reviewer if necessary. From the selected studies, several key

variables were extracted for systematic analysis. These included

the first author, year of publication, study design, sample size

and data collection methods. The core findings of each study were

examined, focusing particularly on their relevance to prenatal PFAS

exposure and respiratory infections in infants and children.

Additional factors, such as follow-up assessments, study

limitations, and the country in which the research was conducted

were also documented.

The findings of the selected studies were

synthesized to provide a comprehensive understanding of the

potential public health implications associated with early-life

exposure to PFAS.

Results

Study selection

A total of six scientific studies were analyzed to

investigate the association between PFAS and the occurrence of

respiratory infections in infants and children (9-11,14,15,21).

Among these studies, one study focused on infant infections, while

the remaining five studies examined childhood infections.

Study and patient characteristics

The six included studies were conducted in China,

Denmark, Japan, Norway and Spain. All were prospective cohort

studies focusing on mother-child pairs, with prenatal PFAS exposure

assessed primarily through maternal blood samples collected during

pregnancy. The majority of the studies employed questionnaires to

gather outcome data, often supplemented by medical or birth

records. Sample sizes varied considerably across studies. The

smallest analytical cohort included just >230 mother-infant

pairs, while the largest involved >1,500 such pairs. Some

studies were nested within national birth cohorts, with original

recruitment populations >6,000 pregnancies. Follow-up periods

ranged from infancy to mid-childhood, extending up to 10 years in

certain cases. Across the studies, measured outcomes included

respiratory infections such as pneumonia, bronchitis, RSV, and

throat infections, as well as fever episodes, lung function

parameters, and general immune-related symptoms.

Sociodemographic characteristics, such as maternal

age, education level and parity were often reported to influence

PFAS levels, and several studies highlighted breastfeeding duration

as a key determinant of ongoing postnatal exposure. However,

differences in exposure assessment methods, follow-up duration and

outcome definitions contributed to heterogeneity among studies.

Each study was systematically reviewed, and key findings were

extracted and organized in chronological order (Table I).

| Table ICharacteristics of the included

studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of the included

studies.

| Included studies |

|---|

| Title | Association between

prenatal exposure to perfluorinated compounds and symptoms of

infections at age 1-4 years among 359 children in the Odense Child

Cohort (10) | Prenatal exposure to

perfluoroalkyl acids and prevalence of infectious diseases up to 4

years of age (21) | Prenatal exposure to

perfluoralkyl substances (PFASs) associated with respiratory tract

infections but not allergy- and asthma-related health outcomes in

childhood (11) | Maternal levels of

perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) during pregnancy and childhood

allergy and asthma-related outcomes and infections in the Norwegian

Mother and Child (MoBa) cohort (14) | Prenatal exposure

to perfluoroalkyl substances, immune-related outcomes, and lung

function in children from a Spanish birth cohort study (9) | Association between

maternal serum concentration of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)

at delivery and acute infectious diseases in infancy (15) |

| Year of

publication | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2019 | 2022 |

| Country | Denmark | Japan | Norway | Norway | Spain | China |

| Study type | Prospective cohort

study | Prospective cohort

study | Prospective cohort

study | Cohort Study | Cohort study | Prospective

study |

| Participants | 6,707 pregnant

women; 1,540 families | 35,000 pregnant

women | 3754 healthy

newborns with a birth weight of at least 2,000 g | 2,000 mother-child

pairs | 2,150 pregnant

women | 773 pregnant women,

>18 years old with singleton pregnancy |

| Focus group | 649 samples, 359

mother-child pairs | 1,558 mother-child

pairs | 641 infants | 792

participants | 1,214 mother-child

pairs | 235 mother-infant

pairs |

| Measurement and

data collection methods | Blood sample,

questionnaires | Questionnaires,

birth medical records, and maternal blood samples | Questionnaires | Questionnaires,

maternal blood samples, and medical records | Questionnaires from

interviews and maternal blood samples in the first trimester | Questionnaires,

logistic and Poisson regression models |

| Measured

outcome | Investigation of

the association between prenatal exposure to PFAS and symptoms of

infections at ages 1-4 years | Examination of the

relationship between prenatal exposure to PFAA and the prevalence

of infectious diseases up to 4 years of age | Determination of

whether prenatal exposure to PFAS is associated with asthma,

allergic diseases, or respiratory infections in childhood | Examination of the

relationship between PFAS measured during pregnancy and childhood

asthma, allergies, and common infectious diseases up to age 7 | Association between

prenatal exposure to PFAS and immune health, respiratory system,

and lung function up to age 7 | Investigation of

associations between prenatal exposure to PFAS and acute infectious

diseases in early childhood |

| Key findings | Positive

association between prenatal exposure to PFOS and PFOA and the

prevalence of fever, which may be a sensitive indicator of

infection. | Prenatal exposure

to PFAA may have immunotoxic effects on the immune system of

offspring. | Prenatal exposure

to PFAS was not associated with atopic or pulmonary conditions up

to age 10, but some PFAS were linked to an increased number of

respiratory infections in the first 10 years of life, suggesting

immunosuppressive effects of PFAS. | i)

Immunosuppressive effects of PFAS on respiratory infections such as

bronchitis/pneumonia and throat infections, as well as

diarrhea/gastric flu. ii) Prenatal exposure to PFAS was inversely

associated with non-communicable urinary tract infections. iii)

Possible role of sex in PFAS-health outcome associations. | i) Different PFAS

may affect the developing immune and respiratory system

differently. ii) Prenatal exposure to PFNA and PFOS may be linked

to a reduced risk of respiratory and immune-related outcomes, while

exposure to PFOA may be linked to reduced lung function in young

children. | PFAS exposure was

associated with an increased risk of diarrhea in the first year of

life, with a higher effect among breastfed infants. |

| Follow-up | Questionnaires at 3

months, 18 months, and 3 years. Repeated text message every 2 weeks

(26 times) over 1 year. | Three questionnaire

completions (first trimester of pregnancy, 4 months postpartum, and

4 years postpartum). | At birth and every

6 months until age 2. | Data collected at

22 and 30 weeks of gestation and when the child was 0.5, 1.5, 3 and

7 years of age. | - | - |

| Study

limitations | i) No information

on PFAS exposure during childhood. ii) No data on fever treatment

or vaccinations during the study period, potentially influencing

fever duration. iii) Unmeasured confounding iv) Possibility of

random findings. | i) Evaluation of

infectious diseases based on maternal reports, not confirmed by

medical records. ii) No studies on the validity of doctor-diagnosed

infections. iii) No assessment of co-exposure to other

environmental chemicals affecting the immune system. iv) Potential

selection bias v) Postnatal PFAA levels and immune system

biomarkers not examined. | i) Recall bias from

questionnaires and interviews. ii) Lack of data on significant

confounding factors. | i) Loss to

follow-up. ii) Outcome dependence on questionnaires. iii) The

number of infection episodes may be difficult for parents to recall

and assess. iv) Uncertain counting of infection episodes. v)

Significant loss to follow-up at age 7. | i) Use of maternal

sample early in pregnancy as an indicator of fetal exposure. ii)

Lack of information on PFAS exposure after birth. iii)

Self-reported questionnaires for outcome assessment bias and

misclassification. iv) The effect estimates of PFAS on lung

function were small. | i) Measurement of

maternal serum PFAS concentrations at delivery used as an indicator

of prenatal exposure. ii) The validity of childhood infection

studies is questioned due to misclassification of infectious

disease causes. iii) Significant loss to follow-up or selection

bias. iv) WQS regression cannot simultaneously determine

associations in different directions for composite index elements.

v) Potential influence of uncontrolled confounding factors. |

PFAS exposure levels in maternal

samples

An analysis of the selected studies confirmed the

presence of PFAS in all maternal blood samples, with PFOS and PFOA

being the most commonly detected compounds, followed by PFNA, PFDA,

PFUA, PFHxS, perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoA), PFBS,

perfluorooctanesulfonamide (PFOSA), perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA)

and perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA) (15,21).

Differences in PFAS levels were not observed in cases of

infertility or pre-eclampsia (14).

However, maternal parity, age and education level appeared to

influence PFAS concentrations. Higher levels of PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS

and PFNA were detected in nulliparous women compared to multiparous

women (10). Additionally, PFAS

concentrations, particularly PFOS and PFOA, were lower in older

women and those with higher education levels (10). A higher pre-pregnancy body mass index

was associated with lower PFDA concentrations, a pattern that was

also observed for other PFAS (10).

Another notable finding was the significant impact of breastfeeding

duration on postnatal PFAS exposure, indicating that lactation may

play a crucial role in ongoing exposure (14).

Association between prenatal PFAS

exposure and infant respiratory infections

In infants during the first year of life, no

associations were identified between prenatal PFAS exposure and the

occurrence of common colds, bronchitis or pneumonia (15). An inverse association between PFBS

and these infections was initially suggested; however, further

analysis did not support this finding (15). Additionally, no sex-based differences

were observed in the association between PFAS exposure and acute

infectious diseases in infancy (15). However, it was noted that a number of

infants exhibited symptoms of infection within their first year,

suggesting the need for additional research on potential

contributing factors (10).

Beyond infancy, prenatal exposure to PFAS,

particularly PFOS and PFHxS, was significantly associated with an

increased risk of respiratory infections in early childhood. By the

age of 4 years, pneumonia and RSV were among the most frequently

reported infections, with similar prevalence in both sexes

(P>0.05) (21). Notably, children

in the highest quartile of PFOS exposure had a 61% increased risk

of developing at least one infectious disease compared to those in

the lowest quartile [odds, ratio (OR), 1.61; 95% confidence

interval (CI), 1.18-2.21; P-value for trend=0.008). Furthermore,

PFHxS exposure was positively associated with infectious diseases

specifically among females, with the highest exposure quartile

showing a 55% increased risk (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 0.976-2.45; P-value

for trend=0.045), whereas PFOS exposure was associated with

infection risk in both sexes (21).

By the age of 2 years, PFUnDA was positively

associated with the number of common cold episodes (11). By 3 years of age, PFOS and PFOA

concentrations were inversely associated with the number of common

colds, particularly among female children [risk ratio (RR) for

PFOS, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.97; P<0.001; RR for PFOA, 0.96; 95%

CI, 0.94-0.99; P=0.012] (14).

However, bronchitis and pneumonia were significantly more frequent

in children with higher prenatal exposure to PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS and

PFHpS, with the effect of PFOA (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.12-1.43) and

PFHxS (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.06-1.24) being stronger in girls

(14). Streptococcal throat

infections were positively associated with PFNA exposure (RR, 1.29;

95% CI, 1.11-1.50), while PFOA exhibited a stronger association in

boys and PFUnDA in girls. Other throat infections were linked to

PFHxS exposure in girls (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.18) (14). Furthermore, children attending

kindergarten at age three were more likely to develop pseudocroup,

which exhibited a positive association with PFUnDA (inverse RR,

0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.95) in those attending childcare, highlighting

a potential interaction between environmental exposures and social

behaviors (14).

Associations between PFAS exposure and

fever in young children

Among children aged 1 to 4 years in the Odense Child

Cohort, prenatal PFAS exposure was significantly associated with

increased infection-related symptoms, independent of confounders

such as smoking, breastfeeding duration, and sex (10). Specifically, children in the highest

tertile of prenatal PFOS exposure experienced a 65% higher rate of

fever days compared to those in the lowest tertile [incidence rate

ratio (IRR), 1.65; 95% CI, 1.24-2.18; P<0.001], and the odds of

having fever above the median level more than doubled (OR, 2.35;

95% CI, 1.34-4.11). A similar though slightly weaker association

was observed for PFOA, with an increased odds ratio of 1.97 (95%

CI, 1.07-3.62) for fever days above the median (10). Additionally, the co-occurrence of

fever with cough or nasal discharge increased with higher PFOS and

PFOA exposure. Notably, children in the medium PFOA exposure

tertile had a 38% higher incidence of episodes with both fever and

nasal discharge compared to the low-exposure group (IRR, 1.38; 95%

CI, 1.03-1.86) (10). PFHxS also

contributed modestly to these combined symptom patterns. Overall,

these findings suggest that fever, as a sensitive and frequent

symptom of infection (reported on average during 1.6% of days per

child annually), may serve as a robust marker of increased

infection susceptibility due to prenatal PFAS exposure (10).

Association between PFAS exposure and

respiratory health in children aged 4 to 7 years

In children aged 4 to 7 years, prenatal exposure to

PFAS remained a key determinant of respiratory health outcomes.

Higher concentrations of several PFAS were associated with a

reduced risk of lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) and

wheezing, with the exception of PFHxS, which was associated with an

increased risk of LRTIs across all age groups (RR, 1.14; 95% CI,

1.00-1.29) (9). Higher levels of

PFNA were linked to a lower probability of LRTIs at age 4 (OR,

0.85; 95% CI, 0.71-1.01) and wheezing at age 7 (OR, 0.69; 95% CI,

0.54-0.88). A protective association with asthma was also observed

for PFNA (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.96), while PFOS exposure was

inversely associated with eczema (RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98)

(9).

However, stratified analysis by breastfeeding

duration revealed an important effect modification: In children who

were breastfed for <4 months, higher prenatal PFNA exposure was

associated with an increased risk of asthma (RR, 2.73; 95% CI,

1.13-6.57). Furthermore, higher prenatal concentrations of PFOA

were associated with lower lung function at age 4, as indicated by

decreased z-scores in FVC (β, -0.17, 95% CI, -0.34 to -0.01) and

FEV1 (β, -0.13; 95% CI. -0.29 to 0.03) These

associations were not significant at age 7. No sex-based

differences were observed in any of the respiratory outcomes

assessed (9).

Discussion

Summary of key findings

The present systematic review synthesized evidence

regarding the association between prenatal exposure to PFAS and the

incidence of respiratory infections in infants and children. The

findings highlight a complex interplay between PFAS exposure and

respiratory health. They also revealed both positive and negative

associations across different compounds and age groups.

The present systematic review of six studies

confirmed the presence of PFAS in maternal blood samples, with PFOS

and PFOA being the most detected compounds. Of note, four out of

the six studies included in the present systematic review

identified significant associations between prenatal PFAS exposure

and an increased risk of respiratory infections in early childhood,

with some evidence suggesting stronger associations in female

children. These associations were particularly evident in female

children. However, the findings were not entirely consistent across

all age groups and PFAS compounds, suggesting that additional

factors may modulate the observed associations.

Interpretation by age

group/outcome

In infants <1 year of age, no significant

associations were detected between prenatal PFAS exposure and

common respiratory infections such as colds, bronchitis, or

pneumonia. However, by the age of 2 to 4 years, increased PFHxS and

PFOS exposure was linked to higher susceptibility to respiratory

infections, including pneumonia and RSV infections. These findings

are consistent with experimental and epidemiological evidence

outside the scope of the present systematic review, which indicate

that PFAS may interfere with immune function and increase

susceptibility to infections (22,23).

Notably, some PFAS compounds, including PFNA and

PFDA, were found to be associated with a reduced risk of lower

respiratory tract infections and wheezing, particularly in children

aged 4 to 7 years. The observed inverse associations between PFNA

and PFDA and certain respiratory outcomes, such as the reduced

incidence of wheezing and lower respiratory tract infections,

warrant cautious interpretation. These findings are

counterintuitive given the known immunotoxic potential of PFAS and

may reflect compound-specific immunomodulatory properties,

differences in toxicokinetics, or residual confounding. For

instance, PFNA and PFDA are longer-chain PFAS with different

biological behaviors compared to PFOS and PFOA, potentially leading

to differing impacts on immune cell differentiation or cytokine

regulation. Additionally, these ‘protective’ associations may be

influenced by factors, such as breastfeeding duration,

socioeconomic status, or reverse causation, where healthier

children are inadvertently more exposed due to differences in

maternal behavior or environmental context. Given the small number

of studies and inconsistent findings, further mechanistic and

epidemiological studies are warranted to clarify whether these

associations represent true protective effects or are the result of

bias or uncontrolled confounding.

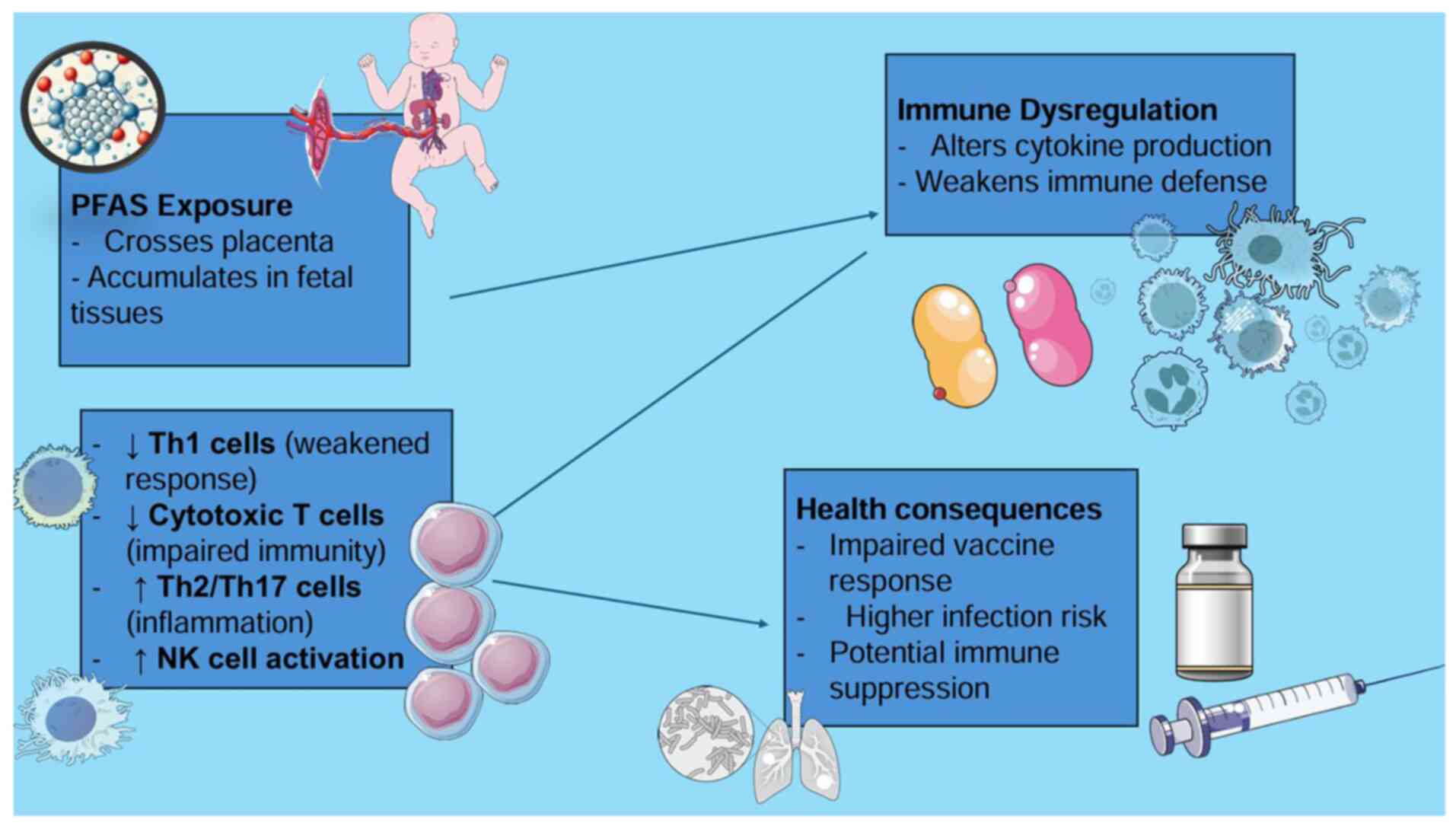

Biological mechanisms

The biological mechanisms underlying the association

between prenatal PFAS exposure and childhood respiratory infections

remain incompletely understood. However, several hypotheses have

been proposed. PFAS are known to interfere with immune function.

They do so by altering cytokine production, reducing

vaccine-induced antibody responses and impairing T-cell

differentiation (22). These

immunotoxic effects may increase vulnerability to infectious

diseases during early childhood, a critical period for immune

system development (23).

PFAS are considered to interfere with immune system

development through several pathways. They may alter cytokine

production, reduce antibody responses to vaccines and disrupt the

balance of immune cell types. For example, prenatal exposure to

PFOS, PFOA, PFNA and PFHxS has been shown to be associated with

increases in certain immune cells called natural killer (NK) cells

and a shift toward immune responses typically involved in allergies

and inflammation (Th2 and Th17 pathways). At the same time, there

appears to be a reduction in immune responses that fight viral and

bacterial infections (Th1 responses). Some evidence also suggests

that PFAS may weaken immune surveillance by lowering the number of

cytotoxic T-cells involved in long-term protection and increasing

markers of immune overactivation. These changes could help explain

why higher PFAS exposure is linked to reduced vaccine effectiveness

and greater vulnerability to infections in early childhood

(22).

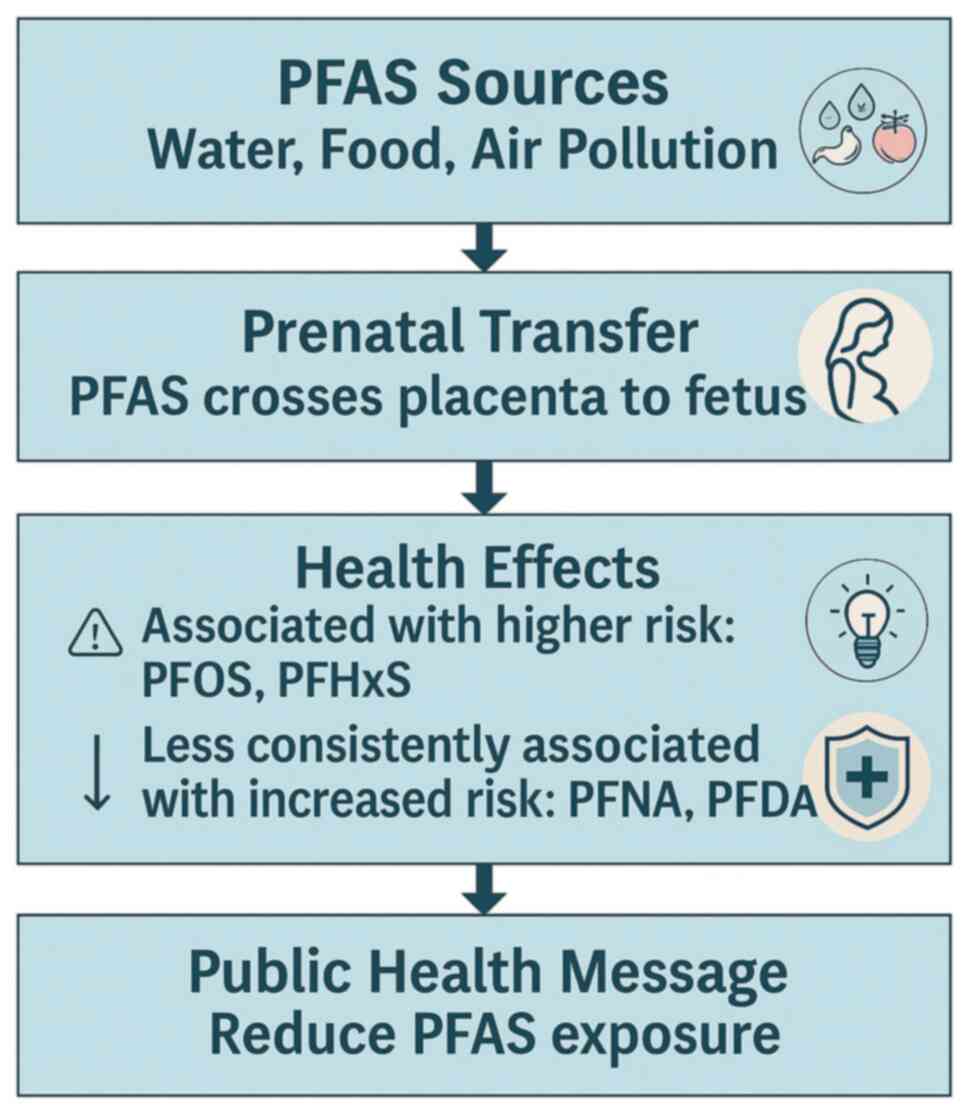

Additionally, PFAS can cross the placental barrier

and accumulate in fetal tissues. This may disrupt normal immune

maturation. Their long biological half-life leads to ongoing

postnatal exposure, especially through breastfeeding. A previous

study highlighted the role of breastfeeding duration in modulating

PFAS-related immune effects, with prolonged breastfeeding

associated with higher PFAS concentrations in infants (15). This raises critical public health

questions regarding the risks and benefits of breastfeeding in

PFAS-contaminated environments. The proposed pathway linking

prenatal PFAS exposure to childhood respiratory infections,

highlighting key mechanisms, such as placental transfer, immune

system modulation and the increased risk of infections is

illustrated in Fig. 2. Furthermore,

provides a visual representation of how prenatal PFAS exposure

alters immune cell function, including shifts in Th1/Th2/Th17

balance and NK cell activity, contributing to increased infection

risk in early life is provided in Fig.

3.

Public health relevance

Given the widespread environmental contamination by

PFAS, our findings have significant public health implications.

Current regulations primarily focus on conventional PFAS compounds

such as PFOA and PFOS, while emerging PFAS alternatives remain

largely unregulated (24). Further

research is required to assess the impact of these newer compounds

on respiratory health outcomes. Moreover, public health

interventions could consider strategies to reduce PFAS exposure

during pregnancy and early childhood, especially in high-risk

areas. Strategies such as regulating PFAS production and use,

enhancing water filtration systems, and promoting dietary awareness

may help mitigate potential health risks, although further evidence

is needed to guide such measures (25).

Limitations

While the present systematic review provides

valuable insight into the association between prenatal PFAS

exposure and respiratory infections, several limitations should be

acknowledged. First, the included studies exhibit heterogeneity in

study design, exposure assessment methods, and outcome definitions,

which may contribute to inconsistency in findings. Second, the

observational nature of the studies limits causal inferences, as

residual confounding by socioeconomic status, environmental

factors, and genetic predisposition cannot be ruled out. Third,

potential publication bias may be present, given the limited number

of eligible studies and the tendency for positive findings to be

preferentially published in peer-reviewed journals. Although grey

literature was included to mitigate this bias, the small sample

size remains a constraint. Fourth, there was considerable

variability in PFAS measurement approaches, including differences

in the biological matrices used (e.g., maternal serum, cord blood),

timing of sample collection, and analytical techniques, which may

affect comparability of exposure estimates. Finally, ARIs were not

uniformly defined across studies, and outcome assessment relied on

varying clinical criteria or parental reports, which may introduce

misclassification and reduce comparability.

Critical appraisal of included

studies

In evaluating the methodological quality of the six

included studies using the Caldwell framework, several strengths

and limitations were identified. All studies employed appropriate

prospective cohort designs, and most recruited large and

demographically diverse populations, enhancing generalizability.

However, notable methodological weaknesses were observed. All

studies relied heavily on self-reported outcomes, often obtained

through parental questionnaires, introducing potential recall and

misclassification bias. None of the studies explicitly described

comparator groups, and only a few controlled for co-exposures or

provided detailed adjustment for confounding factors such as

environmental variables, socioeconomic status, or vaccination

history.

The exposure assessment was generally based on

maternal blood samples, but variation existed in the timing of

sample collection, biomarkers used, and the analytical methods

applied, affecting consistency across studies. Ethical approval and

participant consent procedures were often assumed but not clearly

stated. Only a few studies (9,14,21)

combined self-reported outcomes with medical record validation,

reducing the reliability of reported infections in most cases.

Furthermore, substantial loss to follow-up was reported in at least

two studies, potentially introducing attrition bias.

Recommendations for future

research

Future research should aim to address these

limitations by conducting large-scale prospective cohort studies

with standardized exposure and outcome assessments. Additionally,

mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the specific pathways

through which PFAS influence immune function and respiratory

health. Research should also explore potential sex-specific

differences in PFAS susceptibility, as some studies suggest

differential effects in males and females.

In conclusion, the present systematic review

summarized current evidence on the association between prenatal

exposure to PFAS and respiratory infections in infants and

children. While several studies report associations between higher

prenatal PFAS exposure, particularly to PFHxS and PFOS, and

increased risk of respiratory infections in early childhood,

findings are not entirely consistent across compounds or age

groups. PFAS compounds, such as PFHxS and PFOS have been associated

with an increased risk of respiratory infections, while others such

as PFNA and PFDA may exert different immunomodulatory effects,

which in some cases appear to correlate with reduced incidence of

certain infections. These findings underscore the complex and

potentially compound-specific nature of PFAS-related immune

effects. However, the evidence remains limited by heterogeneity in

study design, exposure assessment, and outcome definitions. Most

studies are observational in nature, precluding causal inferences,

and residual confounding cannot be excluded. Despite these

limitations, the potential for PFAS to disrupt immune development

during critical periods raises important concerns. Future research

should prioritize longitudinal cohort studies with standardized

exposure and outcome measures, as well as mechanistic

investigations to clarify immunological pathways. From a public

health perspective, reducing prenatal PFAS exposure through

regulatory policies and environmental interventions may help

mitigate potential risks, particularly among vulnerable populations

such as pregnant women and young children.

Supplementary Material

Caldwell Framework Quality Assessment

for Included Studies (for the reference citations, please see the

reference list in the main manuscript).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ML and AS conceptualized the study. ML, DM, AS, GK,

VJ, KG, VEG, CRA and DAS made a substantial contribution to data

interpretation and analysis and wrote and prepared the draft of the

manuscript. ML and GK analyzed the data and provided critical

revisions. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. ML and AS

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The other authors declare that they have no

competing interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Georgakopoulou VE: Insights from

respiratory virus co-infections. World J Virol.

13(98600)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Jain N, Lodha R and Kabra SK: Upper

respiratory tract infections. Indian J Pediatr. 68:1135–1138.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Everard ML: Paediatric respiratory

infections. Eur Respir Rev. 25:36–40. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

World Health Organization (WHO): The

Global Health Observatory. Children aged <5 years with ARI

symptoms taken to a health facility (%). Indicator metadata

registry: IMR details 70. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/70.

Accessed Feb 17, 2025.

|

|

5

|

Kumar P, Medigeshi GR, Mishra VS, Islam M,

Randev S, Mukherjee A, Chaudhry R, Kapil A, Ram Jat K, Lodha R and

Kabra SK: Etiology of acute respiratory infections in infants: A

prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 36:25–30.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Thompson MG, Hunt DR, Arbaji AK, Simaku A,

Tallo VL, Biggs HM, Kulb C, Gordon A, Khader IA, Bino S, et al:

Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in infants study (IRIS)

of hospitalized and non-ill infants aged <1 year in four

countries: Study design and methods. BMC Infect Dis.

17(222)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kubale J, Kujawski S, Chen I, Wu Z, Khader

IA, Hasibra I, Whitaker B, Gresh L, Simaku A, Simões EAF, et al:

Etiology of acute lower respiratory illness hospitalizations among

infants in 4 countries. Open Forum Infect Dis.

10(ofad580)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zeng XW, Bloom MS, Dharmage SC, Lodge CJ,

Chen D, Li S, Guo Y, Roponen M, Jalava P, Hirvonen MR, et al:

Prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances is associated with

lower hand, foot and mouth disease virus antibody response in

infancy: findings from the Guangzhou Birth Cohort Study. Sci Total

Environ. 663:60–67. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Manzano-Salgado CB, Granum B,

Lopez-Espinosa MJ, Ballester F, Iñiguez C, Gascón M, Martínez D,

Guxens M, Basterretxea M, Zabaleta C, et al: Prenatal exposure to

perfluoroalkyl substances, immune-related outcomes, and lung

function in children from a Spanish birth cohort study. Int J Hyg

Environ Health. 222:945–954. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dalsager L, Christensen N, Husby S, Kyhl

H, Nielsen F, Høst A, Grandjean P and Jensen TK: Association

between prenatal exposure to perfluorinated compounds and symptoms

of infections at age 1-4 years among 359 children in the odense

child cohort. Environ Int. 96:58–64. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Impinen A, Nygaard UC, Lødrup Carlsen KC,

Mowinckel P, Carlsen KH, Haug LS and Granum B: Prenatal exposure to

perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) associated with respiratory tract

infections but not allergy- and asthma-related health outcomes in

childhood. Environ Res. 160:518–523. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Huang H, Yu K, Zeng X, Chen Q, Liu Q, Zhao

Y, Zhang J, Zhang X and Huang L: Association between prenatal

exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and respiratory tract

infections in preschool children. Environ Res.

191(110156)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Van Leeuw V, Malysheva SV, Fosseprez G,

Murphy A, El Amraoui Aarab C, Andjelkovic M, Waegeneers N, Van

Hoeck E and Joly L: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in food and

beverages: Determination by LC-HRMS and occurrence in products from

the Belgian market. Chemosphere. 366(143543)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Impinen A, Longnecker MP, Nygaard UC,

London SJ, Ferguson KK, Haug LS and Granum B: Maternal levels of

perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) during pregnancy and childhood

allergy and asthma-related outcomes and infections in the norwegian

mother and child (MoBa) cohort. Environ Int. 124:462–472.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang Z, Shi R, Ding G, Yao Q, Pan C, Gao Y

and Tian Y: Association between maternal serum concentration of

perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) at delivery and acute infectious

diseases in infancy. Chemosphere. 289(133235)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Aeraki MM, Metallinou D, Diamanti A,

Georgakopoulou VE and Sarantaki A: Exposure to poly- and

perfluoroalkyl substances during pregnancy and asthma in childhood:

A systematic review. Cureus. 16(e73568)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Huang H, Li X, Deng Y, San S, Qiu D, Guo

X, Xu L and Li Y, Zhang H and Li Y: The association between

prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and

respiratory tract infections in preschool children: A Wuhan cohort

study. Toxics. 11(897)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bline AP, DeWitt JC, Kwiatkowski CF, Pelch

KE, Reade A and Varshavsky JR: Public health risks of PFAS-related

immunotoxicity are real. Curr Environ Health Rep. 11:118–127.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Caldwell K, Henshaw L and Taylor G:

Developing a framework for critiquing health research: An early

evaluation. Nurse Educ Today. 31:e1–e7. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Goudarzi H, Miyashita C, Okada E, Kashino

I, Chen CJ, Ito S, Araki A, Kobayashi S, Matsuura H and Kishi R:

Prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl acids and prevalence of

infectious diseases up to 4 years of age. Environ Int. 104:132–138.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tursi AR, Lindeman B, Kristoffersen AB,

Hjertholm H, Bronder E, Andreassen M, Husøy T, Dirven H, Andorf S

and Nygaard UC: Immune cell profiles associated with human exposure

to perfluorinated compounds (PFAS) suggest changes in natural

killer, T helper, and T cytotoxic cell subpopulations. Environ Res.

256(119221)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Fenton SE, Ducatman A, Boobis A, DeWitt

JC, Lau C, Ng C, Smith JS and Roberts SM: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl

substance toxicity and human health review: Current state of

knowledge and strategies for informing future research. Environ

Toxicol Chem. 40:606–630. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

European Environment Agency: An assessment

on PFAS in textiles in Europe's circular economy. WSP E&IS

GmbH, Brussels, 2024. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/pfas-in-textiles-in-europes-circular-economy/an-assessment-on-pfas-in-textiles-in-europes-circular-economy/@@download/file.

|

|

25

|

Alazaiza MYD, Alzghoul TM, Ramu MB, Abu

Amr SS and Abushammala MFM: PFAS contamination and mitigation: A

comprehensive analysis of research trends and global contributions.

Case Stud Chem Environ Eng. 11(101127)2025.

|