Introduction

Achieving profound pulpal anaesthesia during

endodontic treatment, particularly in mandibular molars with

symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (SIP), remains a persistent

clinical challenge. Inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB), although

routinely employed, demonstrates a high failure rate in such cases,

with reported success rates ranging from 19 to 56% owing to the

heightened inflammatory state of the pulp (1,2).

Achieving effective anaesthesia in cases of SIP in

the mandibular molars, particularly with an IANB, is challenging

due to a combination of physiological and anatomical factors.

Severe inflammation in SIP releases mediators, such as

prostaglandins and bradykinin, which sensitize pulpal nociceptors,

lowering the pain threshold and causing hyperalgesia. This makes

the nerves hyper-responsive, reducing the efficacy of local

anaesthetics (3). Additionally, the

acidic environment in inflamed tissues lowers the pH level,

hindering the dissociation of anaesthetics, such as lidocaine, into

their active form, thus impairing nerve membrane penetration and

sodium channel blockade. Inflamed nerves may also express more

sodium channels, which further resisting anaesthesia (4). Anatomically, mandibular molars pose

challenges owing to potential accessory innervation from nerves,

such as the mylohyoid, lingual or long buccal nerves, which may not

be fully blocked by a standard IANB (3). Collectively, these factors make

profound anaesthesia difficult to achieve in patients with SIP.

Several strategies have been explored to improve

anaesthetic outcomes, including supplemental techniques

(intraosseous, intraligamentary and buccal infiltrations) and the

use of different anaesthetic agents or volumes (5). While a considerable success rate has

been documented for intraosseous injections, this technique not

only requires specialized apparatus, but also incurs significant

expenses and has the potential to inflict damage on root

structures, induce systemic complications, provoke pain and result

in post-injection discomfort (6).

Intrapulpal injections are associated with significant pain and

require pulp exposure (5).

Cryotherapy, a non-pharmacological modality

involving the application of cold, is a promising adjunctive

strategy. It induces local vasoconstriction, reduces oedema,

reduces nerve conduction velocity and elevates the pain threshold

through nociceptor desensitization (7). However, the potential risks associated

with cryotherapy, such as transient tissue sensitivity or

discomfort from cold application, should be considered, although

these are typically minimal with controlled application (7). Previous studies have demonstrated that

intraoral cryotherapy can improve the success rate of IANB, and

reduce intraoperative and post-operative pain during endodontic

procedures (7-10).

For instance, Gopakumar et al (11) evaluated the anaesthetic efficacy of

Endo-Ice spray and intrapulpal ice sticks as adjuncts to IANB in

patients with SIP, finding that both methods significantly reduced

pain and improved anaesthesia success, with ice packs exhibiting

superior outcomes. Moreover, mechanistic investigations have

demonstrated that cooling can suppress capsaicin-sensitive pain

receptors and modulate inflammatory pathways, offering a plausible

biological rationale for its analgesic effects in inflamed pulp

tissues (7,8).

Although previous studies have separately

investigated buccal ice packs or intrapulpal ice application as

adjuncts to IANB (9,10), the combined use of surface and

intrapulpal cryotherapy to maximize analgesic efficacy in patients

with SIP has not yet been explored in a single randomized

controlled trial (RCT), at least to the best of our knowledge. The

present study aimed to address this gap by evaluating the efficacy

of cryotherapy as a supplemental aid to IANB in patients with SIP

undergoing endodontic treatment, with the primary outcome being the

anaesthesia success rate (defined as no or mild pain during

treatment), and the secondary outcome being pain scores during

access opening and cleaning/shaping. By providing a non-invasive,

chairside approach to enhance anaesthesia and reduce pain,

cryotherapy holds significant clinical relevance for improving

patient comfort and procedural outcomes in endodontic practice,

particularly for challenging SIP cases. The null hypothesis was

that cryotherapy would not enhance IANB efficacy compared with

conventional IANB alone.

Patients and methods

Trial design

The present study was a single-centre,

parallel-group RCT with a 1:1 allocation conducted at the

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, J N Kapoor

D.A.V. Dental College and Hospital, adhering to the Consolidated

Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines 2025(12). The trial employed a 1:1 allocation

ratio, comparing two interventions: Group I (IANB with 2%

lignocaine alone) and group II (IANB with 2% lignocaine

supplemented with cryotherapy). The study period spanned from

April, 2023 to January, 2025. Ethical approval for the present

study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of J N Kapoor D.A.V.

Dental College and Hospital, Yamunanagar, India (F/EC/21/0018). The

study was conducted in strict accordance with the principles

outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with all

relevant guidelines and regulations governing human research

ethics. Each patient provided written informed consent prior to

participation. The trial was registered in the Clinical Trials

Registry of India CTRI/2023/03/050746 (https://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/pmaindet2.php?EncHid=ODEzMzU=&Enc=&userName=)

(Clinicaltrials.gov). Prior to the

commencement of patient recruitment, informed consent was obtained

from the patients following a detailed explanation of the

objectives of the study, as well as the procedures, risks and

benefits. No modifications were made following trial

registration.

Selection of participants

Eligibility criteria included patients aged 18-40

years with fully erupted mandibular first molars that exhibited

complete root development. The diagnosis of SIP was established

based on both clinical and diagnostic findings, consistent with the

American Association of Endodontists (AAE) guidelines (13). Clinically, patients presented with a

history of sharp, spontaneous pain, lingering thermal sensitivity

lasting >30 sec following cold stimulus, and referred pain.

Diagnostic confirmation was obtained using cold testing

(Endo-Frost, Coltene), in which a prolonged and exaggerated

response indicated pulpal inflammation. Additionally, all included

teeth exhibited positive responses to electric pulp testing (EPT),

confirming pulpal vitality. Pre-operative pain intensity was

required to exceed 54 mm on the Heft-Parker visual analogue scale

(VAS, 170 mm scale), indicating moderate to severe pain (13). This threshold was selected based on

the Heft-Parker VAS classification, where scores >54 mm

correspond to moderate to severe pain, ensuring the inclusion of

patients with clinically significant pain levels that challenge

anaesthetic efficacy in SIP cases. This cut-off aligns with that of

previous studies (14,15) and facilitates the meaningful

evaluation of the effects of cryotherapy on pain management in

highly symptomatic patients.

Dental anxiety was also assessed pre-operatively

using Corah's Dental Anxiety Scale-Revised (DAS-R), which yields a

total score ranging from 4 to 20(16). The scores were categorized as

follows: ≤8, mild anxiety; 9-12, moderate anxiety; 13-14, high

anxiety; and 15-20, severe anxiety or dental phobia. Only patients

with DAS-R scores >9 were included to ensure a uniform level of

moderate-to-high dental anxiety, as anxiety is known to lower pain

thresholds and can affect the success of local anaesthesia.

Including this criterion helped standardize the psychological

factors affecting the anaesthetic response across participants.

The exclusion criteria included patients with

systemic health conditions, a history of analgesic intake within 12

h prior to the procedure, non-vital teeth (negative to EPT),

radiographic evidence of periapical pathology, such as widened

periodontal ligament space or periapical radiolucency, patients

with psychological or behavioural issues, a history of previous

endodontic treatment and a history of chronic pain. A total of 133

patients were screened; 60 patients who met all the inclusion

criteria were enrolled after obtaining written informed

consent.

Interventions and comparator

Participants were randomly assigned to two groups

(n=30 teeth each) as follows: i) Group I (the control): In this

group, patients received IANB with 3.6 ml 2% lignocaine

hydrochloride (Xylocaine®) and epinephrine (1:100,000)

using a standardized technique (17). The injection site was located

three-quarters of the distance along an imaginary line extending

from the midpoint of the coronoid notch to the deepest part of the

pterygomandibular raphe. A 27-gauge needle (31 mm) was used, and

the syringe barrel was positioned at the contralateral premolar or

molar region. After approximately two-thirds of the needle length

was advanced, and bone contact was achieved, negative aspiration

was confirmed. The entire volume was slowly deposited at a rate of

1 ml/min. During needle withdrawal, a few drops were deposited to

anaesthetize the lingual soft tissues and facilitate rubber dam

clamp placement.

ii) Group II (experimental group): This group

received the same IANB technique with a volume of 3.6 ml of 2%

lignocaine and epinephrine (1:100,000) as group I. In addition,

cryotherapy was administered post-anaesthesia using Endo-Frost

spray (Coltene) on the occlusal, buccal and lingual surfaces for 2

sec each, followed by the intrapulpal application of sterile ice

sticks (6 mm in diameter and 3 cm in length) for 4 min after access

cavity preparation and pulp chamber deroofing. Sterile ice sticks

were prepared and stored in a digital freezer (Gellvann). The

temperature of the ice sticks was monitored using a digital freezer

thermometer to ensure consistency, maintaining a range between -4

and 0˚C to prevent thermal injury. Following access cavity

preparation and pulpal exposure, the ice sticks were gently placed

inside the pulp chamber using sterile tweezers and maintained in

contact for 4 min. Care was taken to monitor any signs of patient

discomfort or tissue sensitivity during application.

Root canal treatment, including access cavity

preparation, cleaning, shaping and irrigation, was standardized for

both the groups. Access cavities were prepared using a high-speed

airotor handpiece with Endo Access burs (Dentsply Sirona) under

water cooling. Working length was determined using an electronic

apex locator (Root ZX II, J. Morita) and confirmed

radiographically. Cleaning and shaping were performed using

ProTaper Gold rotary instruments (Dentsply Sirona) using a

crown-down technique. Irrigation was performed with 3% sodium

hypochlorite (Prime Dental Products Pvt. Ltd.) using side-vented

irrigation needles (NaviTip, Ultradent Products Inc.), followed by

a final rinse with 17% EDTA (MD-Cleanser, Meta Biomed) and

distilled water.

At 20 min following IANB administration, the

effectiveness of local anaesthesia was verified using both

subjective and objective criteria. Subjective signs included

numbness of the lower lip and tongue, confirming anaesthesia of the

inferior alveolar and lingual nerves. Objective testing involved

EPT (D640 Digitest II Pulp Vitality Tester, Parkell) at two

intervals (2 min apart) and a cold stimulus test using a cotton

pellet moistened with Green Endo-Ice spray (Coltene/Whaledent Inc.)

applied for 5 sec. Only teeth that exhibited no response to either

the EPT or the cold test were included. Patients who exhibited a

positive response to either test were excluded from the study and

received supplemental intrapulpal or intraligamentary injections.

During treatment, pain was recorded using the Heft-Parker VAS,

categorized as 0 mm (no pain), <54 mm (mild pain), 54-114 mm

(moderate pain) and >114 mm (severe pain). Successful

anaesthesia was defined as no or mild pain (VAS ≤ 54 mm) during

access and cleaning/shaping. Moderate to severe pain was considered

a failure, and such cases were managed with supplemental

anaesthesia.

Outcomes

A total of 4 patients in the control group and

patient in the experimental group withdrew during follow-up due to

failure to anaesthesia. Thus, 26 patients in the control and 29

patients in the experimental group completed all study visits

(T1-T3) and were included in the final analysis. The primary

outcome was the success rate of anaesthesia, defined as the

percentage of patients reporting no to mild pain (≤54 mm on the

Heft-Parker VAS) during access opening and cleaning/shaping. The

secondary outcome was the pain score recorded on the Heft-Parker

VAS during these procedures.

Data management and harms

The data were stored in a secure password-protected

database with anonymized participant IDs. Only the principal

investigator and statistician accessed the final data set. For the

present study, one interim analysis was conducted at 50% enrolment

to assess the safety and preliminary efficacy, as planned in the

protocol. The Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), J N Kapoor D.A.V.

Dental College and Hospital, reviewed the primary endpoint (adverse

event rate) using a Haybittle-Peto boundary (P<0.001) to control

for type I errors. No significant harm was observed (P>0.001 for

severe adverse events), and the futility criteria (conditional

power <20%) were not met, allowing the study to continue to

completion as planned.

Sample size estimation

The sample size was determined using G*Power

software (version 3.1.9.2, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf,

Germany) with an alpha error of 5% and statistical power of 80%.

Based on an effect size of 0.70 from a previous study (14), and a projected attrition rate of 10%

in each group, 60 patients (30 per group) were deemed sufficient to

detect a clinically significant difference in anaesthesia success

rates.

Randomization

The personnel who enrolled participants and those

who assigned them to the interventions did not have access to the

random allocation sequence. Patients were randomly divided into the

experimental or control group using a computer-generated sequence

(random.org) with a block randomization method (block

size of four) to ensure balanced allocation. The principal

investigator was blinded to the randomization process to prevent

bias, and allocation concealment was maintained using sequentially

numbered opaque sealed envelopes that were opened only on the day

of the procedure.

Blinding

The blinding of the operator and participants was

not feasible due to the nature of cryotherapy intervention.

However, the outcome assessor responsible for recording the

Heft-Parker VAS scores was blinded to the group allocation to

reduce bias.

Statistical analysis

An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed

to account for dropouts; however, primary results are reported for

per-protocol completers. Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel

spreadsheet and analysed using Stata Statistical Software Release

18 (StataCorp, LP). The normality of the data distribution was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, with confirmation via Q-Q

plots. The data were found to be normally distributed. Data were

summarized using descriptive statistics: quantitative variables

(e.g., Heft-Parker VAS scores) and are reported as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD), and qualitative variables (e.g., success

rates) are presented as numbers and percentages. The intergroup

comparisons of pain score were performed using an independent

t-test and intragroup comparisons of the mean pain score were

performed using repeated measures ANOVA with the Bonferroni post

hoc test. The chi-square test was used to compare anaesthesia

success rates between the groups, with a significance level of

0.05. All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle and

included all randomized participants in the final analysis.

Results

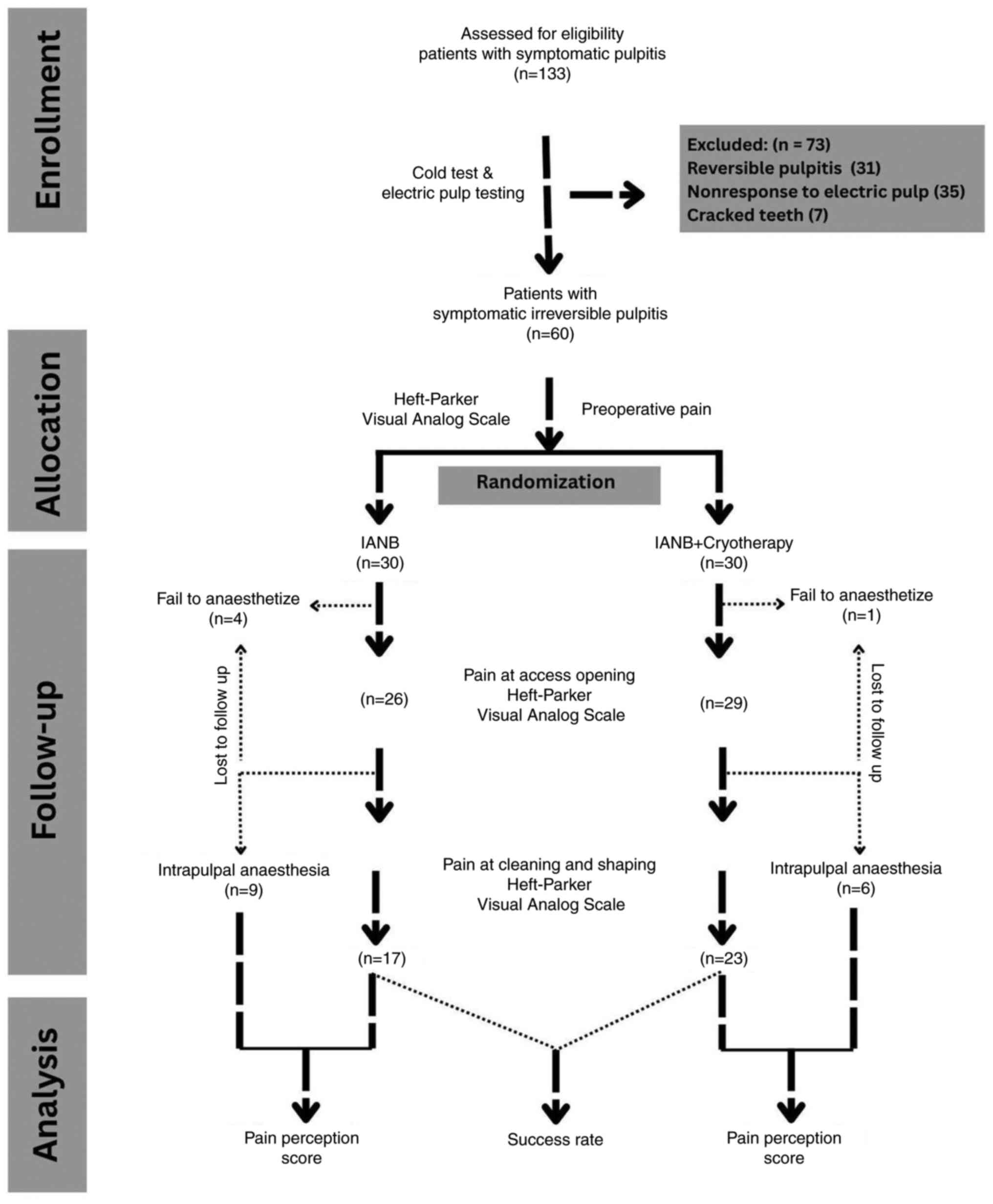

The CONSORT flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1. The study results demonstrated the

baseline comparability (Table I) of

group I and group II, with the mean ages of the patients being

32.8±6.20 and 32.6±6.31 years, respectively (P=0.9), and a

non-significant sex distribution, with each group consisting of 15

males (25%) and 15 females (25%).

| Table IDescriptive analysis of the study

groups. |

Table I

Descriptive analysis of the study

groups.

| Parameters | Group I | Group II | Statistical

value | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years), mean ±

SD | 32.8±6.20 | 32.6±6.31 | 0.123 | NSa |

| Male, n (%) | 15 (25%) | 15 (25%) | 0 | NSb |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (25%) | 15 (25%) | | |

The pre-operative pain scores were similar between

the groups (99.17±15.57 vs. 95.33±18.56, P=0.39) (Table II). This demonstrated that both

groups were comparable at baseline. Group II exhibited

significantly lower pain during access opening compared with group

I (20.60±29.90 vs. 41.43±43.10, P=0.03), although not during

cleaning and shaping (17.73±24.06 vs. 26.95±36.72, P=0.27)

(Table II). Intragroup analysis via

repeated measures ANOVA confirmed a significant pain reduction over

time in both groups (Table III).

Post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni test revealed significant

pain reductions from preoperative to access opening and

cleaning/shaping in both groups (P=0.0003), with greater reductions

in group II (Table IV), but no

notable difference between cleaning/shaping and later stages. The

overall anaesthesia success rate was higher in group II (79.3%,

23/29) than in group I (65.3%, 17/26) (P=0.247), indicating that

cryotherapy enhanced IANB efficacy in patients with SIP; however,

this difference between the groups was not significant (Table V).

| Table IIIntergroup comparison of Heft-Parker

VAS pain scores at different time intervals using an independent

t-test. |

Table II

Intergroup comparison of Heft-Parker

VAS pain scores at different time intervals using an independent

t-test.

| Pain | Group | No. of patients | Mean ± SD | Stats | P-value |

|---|

| Pre-operative

(T0) | Group I | 30 | 99.17±15.57 | 0.86 | 0.39 |

| | Group II | 30 | 95.33±18.56 | | |

| Access opening

(T1) | Group I | 26 | 41.43±43.10 | 2.10 | 0.04a |

| | Group II | 29 | 20.60±29.90 | | |

| Cleaning and

shaping (T2) | Group I | 26 | 26.95±36.72 | 1.11 | 0.27 |

| | Group II | 29 | 17.73±24.06 | | |

| Table IIIIntragroup comparison of Heft-Parker

VAS pain scores at different time intervals (T0, T1 and T2) using

repeated measures ANOVA. |

Table III

Intragroup comparison of Heft-Parker

VAS pain scores at different time intervals (T0, T1 and T2) using

repeated measures ANOVA.

| Groups | Pre-operative

(T0) | Access opening

(T1) | Cleaning and

shaping (T2) | Statistical

value | P-value |

|---|

| Group I | 99.17±15.57 | 41.43±43.10 | 26.95±36.72 | 38.07 | 0.001a |

| Group II | 95.33±18.56 | 20.60±29.90 | 17.73±24.06 | 95.8 | 0.001a |

| Table IVPost-hoc analysis with the Bonferroni

test for pairwise comparison of Heft-Parker VAS pain scores at

three different time intervals (T0, T1 and T2) in both the

groups. |

Table IV

Post-hoc analysis with the Bonferroni

test for pairwise comparison of Heft-Parker VAS pain scores at

three different time intervals (T0, T1 and T2) in both the

groups.

| | Group I | Group II |

|---|

| Pairwise group

comparison | Mean

difference | 95% CI | P-value | Mean

difference | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| T0 vs. T1 | 57.74 | -78.61 to

-36.86 | 0.0003a | 74.73 | -89.88 to

-59.57 | 0.0003a |

| T0 vs. T2 | 72.22 | -93.09 to

-51.34 | 0.0003a | 77.60 | -92.75 to

-62.44 | 0.0003a |

| T1 vs. T2 | 14.48 | -35.35 to 6.39 | 0.6864 | 2.87 | -18.023 to

12.28 | 0.9989 |

| Table VOverall success rate of anaesthesia

in both the groups. |

Table V

Overall success rate of anaesthesia

in both the groups.

| Parameters | Group I (n=26) | Group II

(n=29) | Chi-squared

test | P-value |

|---|

| Successful

anaesthesia | 17 (65.3%) | 23 (79.3%) | 1.34 | 0.247a |

| Unsuccessful

anaesthesia requiring supplemental intrapulpal/intraligamentary

injections | 09 (34.7%) | 06 (20.7%) | | |

Discussion

Effective pain management remains the cornerstone of

successful endodontic therapy, with the ability to achieve profound

anaesthesia, often serving as a critical measure of clinical

competence. IANB is the gold standard for anesthetizing mandibular

teeth during endodontic procedures. However, achieving adequate

anaesthesia in teeth with SIP presents a significant challenge

owing to the acute inflammatory state of the pulp. Inflammation in

SIP leads to an increased expression of tetrodotoxin-resistant

sodium channels on nociceptors, which are less responsive to local

anaesthetics, reducing the success rate of IANB by up to eight-fold

(18). This physiological barrier,

combined with other factors, such as patient anxiety, inaccurate

injection techniques and anatomical variations, has prompted the

exploration of supplementary methods to enhance the efficacy of

IANB (5). Despite these efforts, no

technique has achieved complete pulpal analgesia, underscoring the

need for innovative approaches to improve pain control during

endodontic treatments.

The present study utilized a volume of 3.6 ml of 2%

lidocaine for IANB, based on the findings presented in the study by

Aggarwal et al (19), who

reported a higher success rate with this dosage compared to 1.8 ml

in patients with SIP and reported similar success rates with 2%

lidocaine, 4% articaine and 0.5% bupivacaine. This choice of

anaesthetic volume aligns with the aim of the study of optimizing

the efficacy of IANB as a baseline for comparison with cryotherapy.

Cryotherapy was administered to the experimental group (group II)

using a combination of refrigerant spray (Endo-Frost, Coltene) and

intrapulpal ice sticks. Cryotherapy has been explored in

endodontics in various forms, including cold saline irrigation and

intraoral ice packs, with evidence suggesting that it can mitigate

postoperative pain and enhance anaesthetic outcomes (9,20). For

instance, it has been demonstrated that cold saline irrigation

significantly reduces postoperative pain in teeth with vital pulps,

likely by reducing inflammation and pulpal nerve activity (21).

In the present study, group II (cryotherapy)

demonstrated significantly lower mean pain scores than group I

(control) during access opening (P<0.001), indicating that

cryotherapy effectively enhanced the efficacy of IANB at this stage

of treatment. However, during cleaning and shaping, while group II

exhibited a lower mean pain score, the difference was not

statistically significant (P>0.05). This non-significant

difference may be attributed to the transient nature of the

analgesic effects of cryotherapy, as the cooling-induced nociceptor

desensitization and reduced pulpal blood flow likely diminish over

time (7). The intrapulpal ice

application, administered for 4 min immediately following access

cavity preparation, may have exerted its maximum effect during the

initial stages of treatment, with the cryoanesthetic effect waning

by the time cleaning and shaping commenced, typically 10-15 min

later in the procedure. This temporal limitation is consistent with

prior studies, such as Vera et al (22), which noted that the effects of

cryotherapy are most pronounced within a short window

post-application due to tissue rewarming and restoration of normal

neural conduction. Additionally, the mechanical stimulation and

irrigation during cleaning and shaping may further activate

sensitized nociceptors in inflamed pulp tissue, potentially

counteracting the residual cryotherapy effect (21). These factors likely explain the lack

of a significant difference at this later stage, suggesting that

supplemental cryotherapy applications or alternative adjunctive

techniques may be necessary to maintain analgesia throughout the

entire endodontic procedure.

The present study experienced a higher dropout rate

in the control group (4 patients) compared with the experimental

group (1 patient), primarily due to anaesthesia failure, raising

the possibility of skewed outcomes. However, the use of an ITT

analysis, alongside the primary per-protocol analysis of completers

(26 control and 29 experimental patients), helped mitigate

potential bias by including all randomized participants in the

final analysis.

Cryotherapy induces vasoconstriction and diminishes

cellular metabolism by restricting biochemical processes, which

reduces the extent of tissue injury, consequently reducing the

oxygen requirements of cells and curtailing the production of free

radicals within tissues. The vasoconstrictive response yields

anti-edematous effects, whereas analgesia is attained following a

decrease in temperature due to the inhibition of nerve endings

resulting from the application of cold stimuli (7). The magnitude of the vasoconstriction

reaches its peak at a temperature of 15˚C, and research has

indicated that a reduction in body temperature diminishes

peripheral nerve conduction; notably, at ~7˚C, there is a total

deactivation of myelinated A delta fibres, whereas the

non-myelinated C-fibres become inactive at ~3˚C (23).

Overall, in the present study, group II achieved a

higher success rate of anaesthesia than group I, with a

statistically significant difference. These findings are consistent

with those of Topçuoğlu et al (24), who reported that preoperative

intraoral ice pack application for 5 min significantly improved

IANB success rates in patients with SIP. Similarly, Gopakumar et

al (11) evaluated the effect of

intraoral cryotherapy using ice sticks and refrigerant spray, and

found that both methods significantly reduced pain and improved

IANB outcomes in SIP cases, with ice packs showing superior

results, as observed in the present study.

The application of Endo-Frost refrigerant spray

(-50˚C), composed of propane, butane and isobutane, in combination

with intrapulpal ice sticks for 4 min, likely contributed to the

observed pain reduction in group II. Vera et al (22) suggested that the optimal duration of

cryotherapy varies by tissue type, with 4-5 min being sufficient to

achieve therapeutic effects without causing damage in areas with

minimal muscle and fat, as in intraoral applications. The 4-min

duration for intrapulpal ice application used in the present study

was selected based on this evidence, as it balances the need for

effective nociceptor desensitization and reduced pulpal blood flow

with the prevention of thermal injury to pulpal or surrounding

tissues. This duration is further supported by practical

considerations, as preliminary testing indicated that 4 min allowed

consistent cooling of the pulp chamber without patient discomfort

or procedural delays, aligning with findings from Gopakumar et

al (11), who used a similar

duration for intrapulpal ice application. By contrast, Koteeswaran

et al (25) found no

significant difference between IANB alone and IANB with cryotherapy

using Endo-Ice spray (-26.2˚C) and intrapulpal ice. This

discrepancy may be attributed to the lower temperature of

Endo-Frost (-50˚C) used in the present study, which likely produced

a more pronounced cryoanesthetic effect compared to Endo-Ice,

facilitating deeper tissue cooling and greater pain reduction.

The physiological mechanisms of cryotherapy provide

the rationale for its effectiveness. Cold application extracts heat

from the tissue, causing vasoconstriction and reducing local

inflammation, thereby mitigating oedema and inflammation (7). Goodis et al (26) reported that tooth cooling decreased

pulpal blood flow, which can eliminate pain perception in some

cases. Additionally, cryotherapy reduces the adherence of

leukocytes to capillary endothelial walls and decreases endothelial

dysfunction (7). According to Van't

Hoff's law, a 10˚C decrease in tissue temperature reduces local

enzyme activity and cellular metabolism by 2-3-fold, minimizing

tissue damage (7). Furthermore,

cryotherapy disrupts nerve conduction by causing myelin sheath

deterioration and axonal degeneration, raising the nociceptive

threshold, and slowing pain signal transmission (19). Cold also inactivates oral vanilloid

receptors, which are upregulated during inflammation and are

sensitive to capsaicin, further reducing pain perception (27). These mechanisms likely explain why

patients often use cold (e.g., ice or cold water) to alleviate

acute pulpal pain, a clinical observation supported by prior

literature (28,29). Collectively, these factors likely

contributed to the significant pain reduction observed in group II

compared with group I during endodontic treatment.

Demographic variables (pre-operative pain, age and

sex) were comparable between the two groups, indicating that these

factors did not influence the study outcomes. Consequently, the

null hypothesis that there would be no difference in IANB efficacy

between group I and group II was rejected. The superior performance

of the cryotherapy group underscores its potential as a

non-invasive, chairside technique to enhance IANB efficacy in SIP

cases.

Previous studies evaluating cryotherapy as an

adjunct to IANB in patients with SIP have provided valuable

insight, but are not without potential biases (9,11,15). A

number of studies, including those examining buccal ice packs or

intrapulpal ice application, often faced challenges with blinding

due to the sensory nature of cold application, which may introduce

placebo effects or patient reporting bias, particularly when

subjective pain scales like the Heft-Parker VAS were used (11,30).

Additionally, small sample sizes in some trials may have limited

statistical power, potentially overestimating or underestimating

the efficacy of cryotherapy. Variability in patient selection

criteria, such as inconsistent preoperative pain thresholds or

inclusion of patients with differing levels of dental anxiety,

could further confound results, as these factors influence pain

perception and anaesthesia outcomes (15,31).

These methodological limitations highlight the need for more robust

study designs, such as larger sample sizes and the use of sham

cryotherapy or objective pain assessment methods, to minimize bias

and enhance the reliability of findings in future research.

The findings of the present study suggest several

clinical implications for integrating cryotherapy into the

management of SIP in endodontic practice. First, cryotherapy, using

a combination of cold spray and intrapulpal ice application, can

serve as an effective adjunct to inferior alveolar nerve block

anaesthesia, particularly for patients with severe pre-operative

pain. This approach enhances patient comfort during initial

treatment stages, potentially improving procedural efficiency and

patient cooperation in challenging cases. Second, in settings where

immediate root canal therapy is not available, such as emergency

departments or rural clinics, cryotherapy could provide temporary

pain relief by reducing pulpal inflammation and nerve sensitivity,

acting as a bridge to definitive treatment while referrals are

arranged. Third, by decreasing inflammation and nerve

responsiveness, cryotherapy may help reduce post-operative pain,

potentially lowering the need for analgesics and supporting a

smoother recovery. Incorporating cryotherapy into standard

protocols for managing symptomatic irreversible pulpitis offers a

non-invasive, cost-effective strategy to improve anaesthesia

outcomes and patient experience. However, further research is

required to establish standardized protocols, including optimal

timing and frequency of cryotherapy application, to ensure

consistent benefits across diverse clinical settings.

Despite these promising results, the present study

has several limitations. The small sample size (n=60) may limit the

generalizability of the findings, necessitating larger trials to

confirm the efficacy of cryotherapy. Additionally, the lack of

blinding for both operators and patients due to the nature of

cryotherapy application introduces a potential for bias, which

could have influenced pain reporting. Future studies could mitigate

this limitation by implementing sham cryotherapy, such as using a

non-cooled spray or room-temperature sticks, to blind participants

and operators while maintaining the procedural appearance of

cryotherapy application. Additionally, employing objective pain

assessment methods, such as pulpal nerve stimulation or

physiological monitoring (such as heart rate variability), could

further reduce bias in pain reporting. Variations in operator skill

during cryotherapy application or differences in pulp chamber

anatomy across patients may have also influenced the consistency of

the effects of cryotherapy, as these factors could affect the

precision of ice stick placement or the extent of cooling achieved.

These strategies would enhance the robustness of future trials

evaluating the efficacy of cryotherapy in endodontic pain

management.

In conclusion, cryotherapy, as a supplementary

technique, significantly enhances the efficacy of IANB in patients

with SIP, particularly during access opening, offering a simple and

non-invasive method to reduce pain and improve patient comfort. The

higher anaesthesia success rate compared to conventional IANB alone

underscores its potential as a valuable adjunct in endodontic

practice. However, larger, well-controlled studies are required to

validate these findings and address the limitations of the present

study, ensuring the consistent integration of cryotherapy into

standard protocols for managing SIP.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The present randomized

controlled trial is registered as.

Author's contributions

SK and PB conceptualized the study, designed the

methodology and drafted the initial manuscript. SK and RKB

contributed to data collection, performed the clinical intervention

and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. RKB

and VG conducted the statistical analysis, interpreted the data,

and contributed to manuscript drafting. SG and SDG participated in

the study design, patient recruitment and data interpretation,

ensuring clinical relevance. SG and SDG managed data acquisition,

including patient assessments and CPAP compliance monitoring. SK

and SDG confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. and confirm

the authenticity of data, and finalized the manuscript for

submission. All authors reviewed, and have read and approved the

final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

work, ensuring its accuracy and integrity.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval for the present study was from the

Ethics Committee of J N Kapoor D.A.V. Dental College and Hospital,

Yamunanagar, India (F/EC/21/0018). The study was conducted in

strict accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration

of Helsinki and in compliance with all relevant guidelines and

regulations governing human research ethics. Each patient provided

written informed consent prior to participation.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Falatah AM, Almalki RS, Al-Qahtani AS,

Aljumaah BO, Almihdar WK and Almutairi AS: Comprehensive strategies

in endodontic pain management: an integrative narrative review.

Cureus. 15(e50371)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Thangavelu K, Kannan R and Kumar NS:

Inferior alveolar nerve block: Alternative technique. Anesth Essays

Res. 6:53–57. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Fowler S, Drum M, Reader A and Beck M:

Anesthetic success of an inferior alveolar nerve block and

supplemental articaine buccal infiltration for molars and premolars

in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis. J Endod.

42:390–392. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ueno T, Tsuchiya H, Mizogami M and

Takakura K: Local anesthetic failure associated with inflammation:

verification of the acidosis mechanism and the hypothetic

participation of inflammatory peroxynitrite. J Inflamm Res.

1:41–48. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Meechan JG: Supplementary routes to local

anaesthesia. Int Endod J. 35:885–896. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM and Meechan JG: A

prospective randomized trial of different supplementary local

anesthetic techniques after failure of inferior alveolar nerve

block in patients with irreversible pulpitis in mandibular teeth. J

Endod. 38:421–425. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Fayyad DM, Abdelsalam N and Hashem N:

Cryotherapy: A new paradigm of treatment in endodontics. J Endod.

46:936–942. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Algafly AA and George KP: The effect of

cryotherapy on nerve conduction velocity, pain threshold and pain

tolerance. Br J Sports Med. 41:365–369. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Elheeny AAH, Sermani DI, Saliab EA and

Turky M: Cryotherapy and pain intensity during endodontic treatment

of mandibular first permanent molars with symptomatic irreversible

pulpitis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig.

27:4585–4593. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ahmad MZ: Effects of intracanal

cryotherapy on postoperative pain in necrotic teeth with

symptomatic apical periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical

trial. Front Dent Med. 6(1543383)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gopakumar R, Jayachandran M, Varada S,

Jayaraj J, Ezhuthachan Veettil J and Nair NS: Anesthetic efficacy

of Endo-Ice and intrapulpal ice sticks after inferior alveolar

nerve block in symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A randomized

controlled study. Cureus. 15(e42135)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hopewell S, Chan AW, Collins GS,

Hróbjartsson A, Moher D and Schulz KF: CONSORT 2025 statement:

Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. Lancet: April

14, 2025 (Epub ahead of print). doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(25)00672-5.

|

|

13

|

Glickman GN: AAE consensus conference on

diagnostic terminology: Background and perspectives. J Endod.

35:1619–1620. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Heft MW and Parker SR: An experimental

basis for revising the graphic rating scale for pain. Pain.

19:153–161. 1984.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Gupta R and Prakash P: Cryotherapy as an

adjunct to inferior alveolar nerve block in symptomatic

irreversible pulpitis: A randomised controlled clinical trial. IP

Indian J Conserv Endod. 7:16–23. 2022.

|

|

16

|

Ronis DL, Hansen CH and Antonakos CL:

Equivalence of the original and revised dental anxiety scales. J

Dent Hyg. 69:270–272. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Malamed SF: Handbook of Local Anesthesia.

6th edition. Elsevier, St. Louis, pp225-252, 2014.

|

|

18

|

Kistner K, Zimmermann K, Ehnert C, Reeh PW

and Leffler A: The tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ channel Na(v)1.8

reduces the potency of local anesthetics in blocking C-fiber

nociceptors. Pflugers Arch. 459:751–763. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Aggarwal V, Singla M and Miglani S:

Comparative evaluation of anesthetic efficacy of 2% lidocaine, 4%

articaine, and 0.5% bupivacaine on inferior alveolar nerve block in

patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A prospective,

randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Oral Facial Pain

Headache. 31:124–128. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Keskin C, Özdemir Ö, Uzun İ and Güler B:

Effect of intracanal cryotherapy on pain after single-visit root

canal treatment. Aust Endod J. 43:83–88. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Almohaimede A and Al-Madi E: Is intracanal

cryotherapy effective in reducing postoperative endodontic pain? An

updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical

trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(11750)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Vera J, Castro-Nuñez MA, Troncoso-Cibrian

MF, Carrillo-Varguez AG, Méndez Sánchez ER and Rangel-Padilla JA:

Effect of cryotherapy duration on experimentally induced connective

tissue inflammation in vivo. Restor Dent Endod.

48(e29)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Belitsky RB, Odam SJ and Hubley-Kozey C:

Evaluation of the effectiveness of wet ice, dry ice, and cryogenic

packs in reducing skin temperature. Phys Ther. 67:1080–1084.

1987.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Topçuoğlu HS, Arslan H, Topçuoğlu G and

Demirbuga S: The effect of cryotherapy application on the success

rate of inferior alveolar nerve block in patients with symptomatic

irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 45:965–969. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Koteeswaran V, Ballal S, Natanasabapathy V

and Kowsky D: Efficacy of Endo-Ice followed by intrapulpal ice

application as an adjunct to inferior alveolar nerve block in

patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis-a randomized

controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 23:3501–3507. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Goodis HE, Winthrop V and White JM: Pulpal

responses to cooling tooth temperatures. J Endod. 26:263–267.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Laureano Filho JR, de Oliveira e Silva ED,

Batista CI and Gouveia FM: The influence of cryotherapy on

reduction of swelling, pain and trismus after third-molar

extraction: A preliminary study. J Am Dent Assoc. 136:774–778; quiz

807. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Babes A, Amuzescu B, Krause U, Scholz A,

Flonta ML and Reid G: Cooling inhibits capsaicin-induced currents

in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. Neurosci Lett.

317:131–134. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bleakley CM and Hopkins JT: Is it possible

to achieve optimal levels of tissue cooling in cryotherapy? Phys

Ther Rev. 15:344–350. 2010.

|

|

30

|

Bazaid DS and Kenawi LMM: The effect of

intracanal cryotherapy in reducing postoperative pain in patients

with irreversible pulpitis: A randomized control trial. Int J

Health Sci Res. 8:83–88. 2018.

|

|

31

|

Karunakar P, Solomon RV, Kumar BS and

Reddy SS: Evaluating the pain at site, onset of action, duration

and anesthetic efficacy of conventional, buffered lidocaine, and

precooled lidocaine with intraoral cryotherapy application in

patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A clinical study.

Conserv Dent Endod. 27:1228–1233. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|