Introduction

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a thrombotic

microangiopathy (TMA) characterized by the triad of

microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and acute

kidney injury (1). HUS is classified

into two main types: i) Typical HUS, most commonly caused by Shiga

toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections; and ii)

atypical HUS (aHUS), which is primarily related to the

dysregulation of the complement system due to genetic mutations.

Typical HUS mainly affects children, whereas aHUS is more frequent

among adults, particularly women during pregnancy or postpartum.

Distinguishing between these forms is essential for an accurate

diagnosis and management (2,3). First documented by Gasser et al

(4) in 1955, HUS primarily affects

the renal vasculature, resulting in arteriolar fibrinoid necrosis

(5). Its global incidence is ~2 to 3

cases per 100,000 individuals annually (6). While typical HUS affects children of

both sexes equally, aHUS is more frequently diagnosed in adult

women, potentially linked to pregnancy-related triggers (7). As aforementioned, the syndrome is

categorized into two forms: Typical HUS, commonly associated with

infections such as Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli

(STEC), and aHUS, often driven by genetic mutations affecting the

complement system (8). Both variants

arise from the dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway,

leading to the formation of the membrane attack complex (C5b-9)

(9). This process damages

endothelial cells and promotes a procoagulant state, inducing

platelet deposition and resulting in microthrombi within the renal

microvasculature that determines disease severity (10).

Clinically, HUS presents with fatigue, pallor due to

anemia and lethargy, progressing to renal manifestations, including

hematuria, proteinuria, and, in severe cases, anuria (11). Extrarenal complications, such as

cardiac and neurological involvement, occur in up to 20% of

patients (12,13). Diagnosis is established through

laboratory findings, such as elevated levels of lactate

dehydrogenase, schistocytes, thrombocytopenia and renal impairment,

supported by imaging to assess kidney involvement (14). A histological evaluation may be

required to differentiate HUS from other TMAs, such as thrombotic

thrombocytopenic purpura (15,16).

Treatment is tailored to disease severity and recurrence risk

(17), encompassing supportive care

(e.g., hydration and transfusions), immunosuppressive therapy

(18), and, in refractory cases,

renal replacement therapy or kidney transplantation. Genetic

testing is recommended, as ~50% of aHUS cases are associated with

mutations in complement-regulating genes, notably complement factor

H (CFH) (19-21).

Additional risk factors include certain medications, autoimmune

disorders and chronic illnesses (22,23).

Pregnancy is a recognized risk factor for aHUS,

likely due to the decreased production of complement regulatory

proteins and altered maternal immunity (24). However, diagnosis in the postpartum

period is challenging, as its features overlap with obstetric

conditions such as preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver

enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, often delaying

appropriate management (25,26). Given the rarity of aHUS and its

potential for severe morbidity and mortality, the present study

describes the case of a 29-year-old female patient who developed

aHUS 4 days following a cesarean delivery.

Case report

Initial presentation

A 29-year-old female patient (G2P1C1) presented to

the Emergency Department at the Gynecology and Obstetrics Hospital

No. 15 of the Mexican Social Security Institute (Chihuahua, Mexico)

on the 4th day postpartum following a cesarean section, reporting

purulent discharge from the vaginal and surgical sites, along with

urinary symptoms. The patient described a 4-day history of fever

(38.9˚C), asthenia, fatigue, dyspnea and pallor. Her medical

history was notable for a cesarean section at 39 weeks of

gestation, complicated by an estimated 3-liter obstetric

hemorrhage.

Upon admission, laboratory tests revealed severe

normocytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin level, 4.6 g/dl) and

acute kidney injury (creatinine, 10.6 mg/dl; urea, 286 mg/dl; blood

urea nitrogen, 133.47 mg/dl); urinalysis revealed leukocyturia

(20-22 leukocytes per field) with granular casts. The patient

received empirical intravenous antibiotics and 3 units of packed

red blood cells before being transferred to a secondary care

facility the Regional General Hospital No. 1 of the Mexican Social

Security Institute, Morelos, Mexico for further management.

Diagnostic workup

The nephrology service evaluation identified anuria

(urine output 0.08 ml/kg/h), metabolic acidosis, azotemia and

hyperkalemia, necessitating transfer to the intensive care unit

(ICU) for intermittent hemodialysis. Initially, acute tubular

necrosis secondary to ischemic injury from obstetric hemorrhage was

suspected. A wound culture was obtained and dual antibiotic therapy

was initiated. The general surgery team drained 20 ml of purulent

fluid from the surgical site, resulting in transient clinical

improvement.

After 3 days, the patient developed lower

respiratory symptoms requiring supplemental oxygen. A chest

computed tomography scan revealed bilateral hilar reticular

opacities. Given these findings, and considering it was peak

influenza season, empirical treatment with oseltamivir (75 mg,

administered orally twice daily) was initiated following the

institutional protocol (27).

However, subsequent testing ruled out influenza infection.

Treatment course

The patient subsequently exhibited signs of fluid

overload and acute pulmonary edema, which was refractory to

non-invasive ventilation, leading to 4 days of mechanical

ventilation.

Due to persistent severe anemia, thrombocytopenia

and laboratory evidence of hemolysis (schistocytes on blood smear,

elevated lactate dehydrogenase without hyperbilirubinemia), a

peripheral blood smear was performed, revealing >10 schistocytes

per high-power field. She received fresh frozen plasma and

intravenous corticosteroids. Thrombotic microangiopathy was

investigated; however, complement levels were normal and

autoantibody tests yielded negative results: ANCA, 0.8 ng/m;

anti-dsDNA, 9.3 IU/ml; C3, 107 mg/dl; C4, 24.8 mg/dl; ADAMTS13

activity, 70%; and anticardiolipin, 1.2; these findings ruled out

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

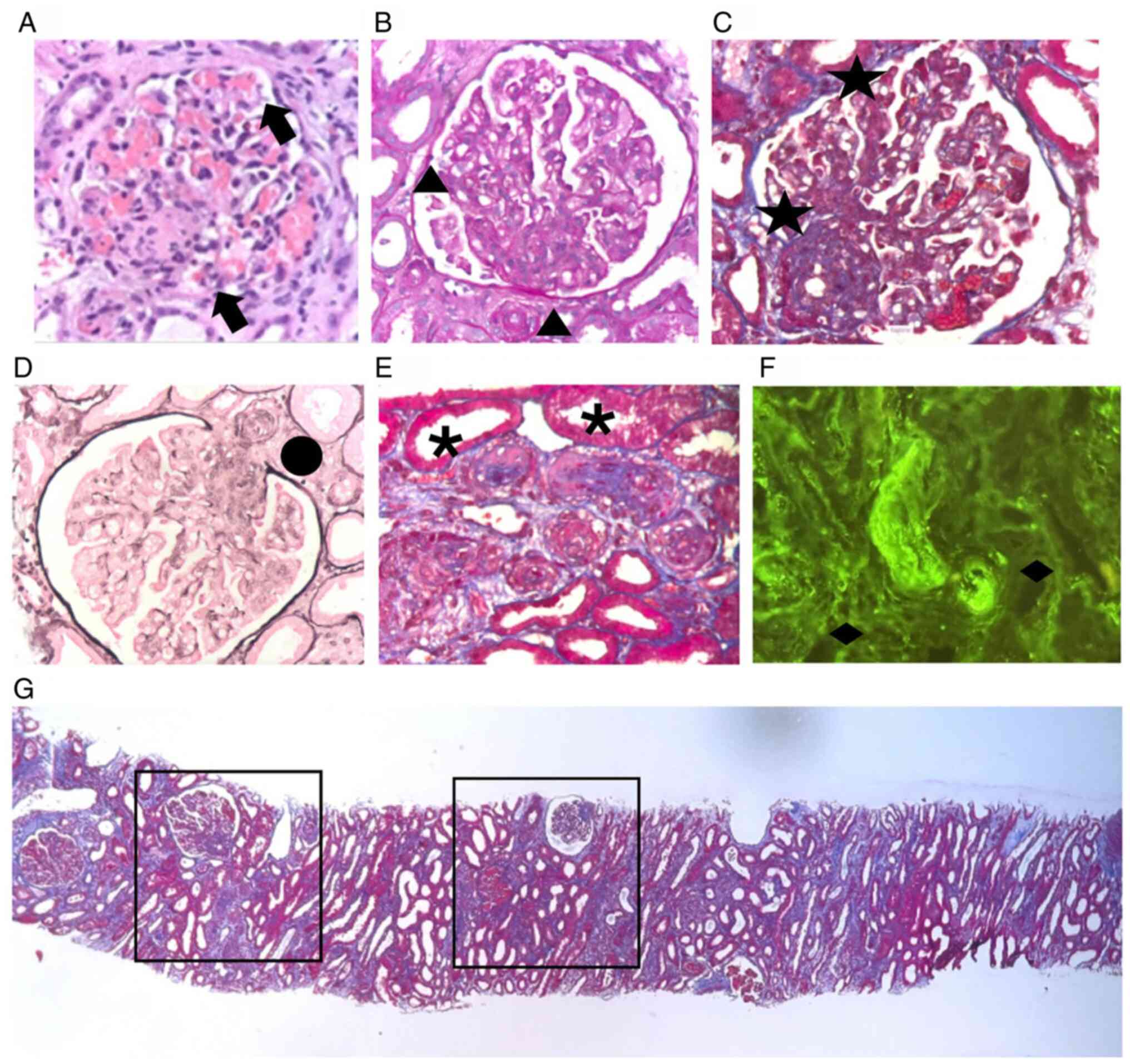

Given the ongoing hemolytic anemia, renal impairment

and the absence of positive autoantibodies, a percutaneous kidney

biopsy was performed. Renal tissue samples were fixed in 10%

neutral buffered formalin for 24 h at room temperature, embedded in

paraffin, and cut into 4-µm-thick sections. Hematoxylin and eosin

(H&E), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), Masson's trichrome and Jones

silver staining were performed following standard histopathological

protocols using reagents supplied by Sigma-Aldrich®

(Merck KGaA). The sections were stained at room temperature

according to the manufacturer's recommendations (H&E,

hematoxylin 10 min, eosin 3 min; PAS, periodic acid 5 min, Schiff's

reagent 15 min; Masson's trichrome: Sequential staining was

performed with Weigert's iron hematoxylin, Biebrich scarlet-acid

fuchsin, phosphotungstic/phosphomolybdic acid and aniline blue;

Jones silver: Methenamine silver impregnation with periodic acid

oxidation). Microscopic examination and image acquisition were

performed using a Nikon Eclipse E200 microscope® (Nikon

Corporation). A histopathological analysis demonstrated thrombotic

microangiopathy in both acute and chronic phases, with glomerular

and interlobular artery thrombosis, membranoproliferative

glomerulonephritis, diffuse endothelialitis without immune complex

deposition and severe arteriolonephrosclerosis with onion-skin

elastosis. Later, the sections were incubated overnight at 4˚C with

the following primary antibodies: IgA (1:100; cat. no. A0262), IgG

(1:200; cat. no. A0423), IgM (1:100; cat. no. A0425), C1q (1:100;

cat. no. A0136), C3c (1:200; cat. no. A0062), fibrinogen (1:100;

cat. no. A0080), kappa light chain (1:200; cat. no. A0191), lambda

light chain (1:200; cat. no. A0193) and albumin (1:200; cat. no.

A0001) (all from Dako, Agilent Technologies, Inc.). After washing,

the slides were incubated with horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies [goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat.

no. P0448) or goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. P0447) (both from Dako,

Agilent Technologies, Inc.), depending on the primary antibody] for

1 h at room temperature. Visualization was achieved using

3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate solution (cat. no. K3468;

Dako, Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Immunohistochemical staining for

immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG and IgM), complement components (C1q and

C3c), fibrinogen, kappa, lambda and albumin was uniformly negative,

confirming the diagnosis of HUS (Fig.

1).

Clinical outcomes

Several days later, the patient developed

exsanguinating hemoptysis. Bronchoscopy revealed diffuse alveolar

hemorrhage without specific lesions, leading to a diagnosis of

diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. However, no biopsy was performed, as

no specific lesions were visualized. The patient required

reintubation on hospital day 15 and was successfully extubated

after 10 days. However, she developed ventilator-associated

pneumonia, necessitating broad-spectrum antibiotics, which delayed

the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. The rapid postpartum

onset of anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury in the

patient described herein closely mirrors the presentation described

in previously reported cases of pregnancy-associated aHUS, in which

early complement blockade has often been linked to improved

hematologic recovery, although renal outcomes remain variable. A

distinctive feature in the present case was the presence of

multiple severe complications, including diffuse alveolar

hemorrhage and ventilator-associated pneumonia, which are less

frequently described in the literature and may have contributed to

delays in targeted treatment. Following improvement and resolution

of the infection, she was discharged with ongoing intermittent

hemodialysis and remains under nephrology follow-up for renal

replacement therapy. Renal transplantation from a first-degree

relative (sister) was performed following renal replacement

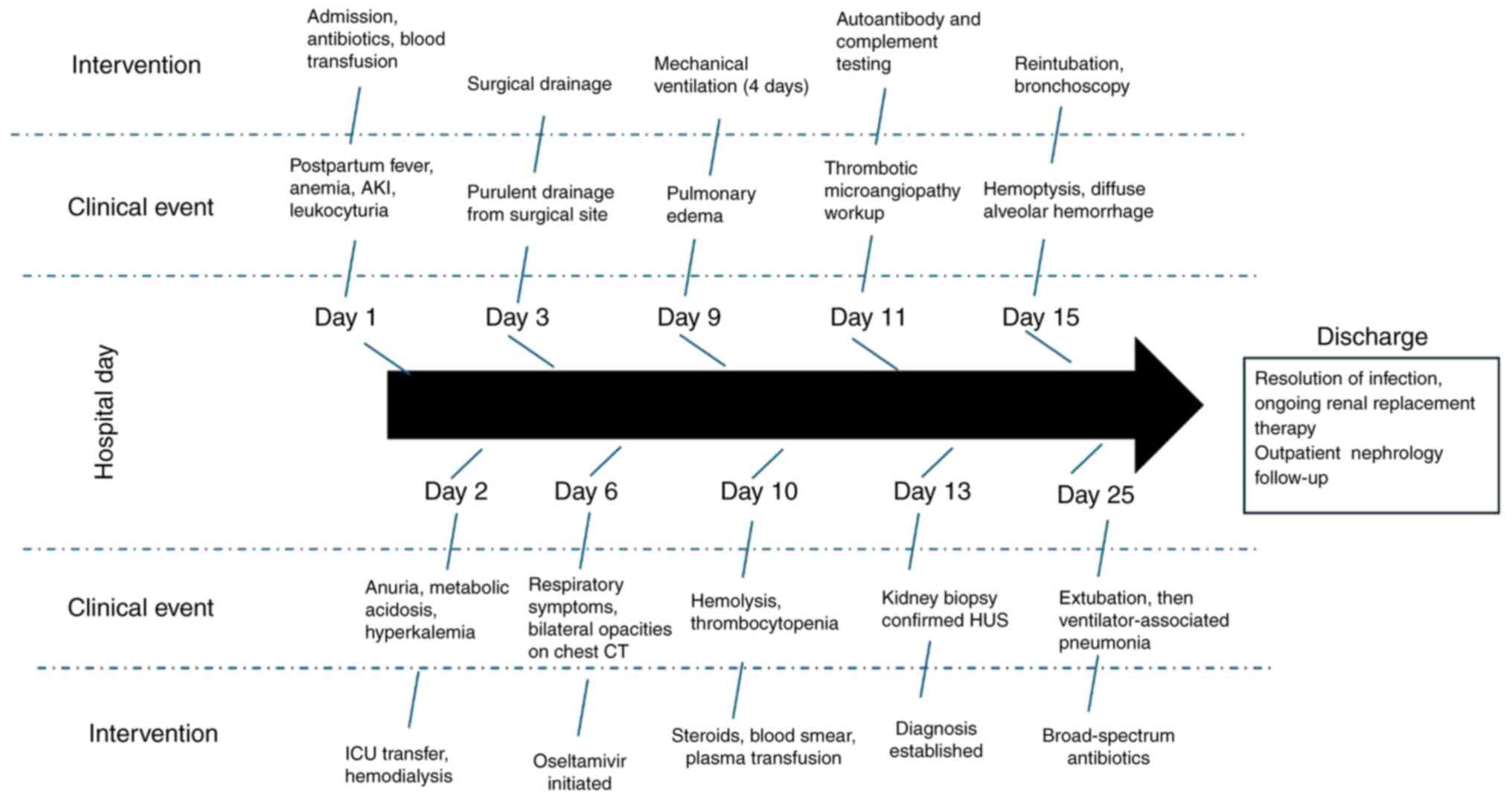

therapy, with preserved graft function on follow-up. A concise

summary of key laboratory parameters at major clinical milestones

is presented in Table I. The

chronological sequence of clinical events and interventions is

depicted in Fig. 2.

| Table IKey laboratory values and clinical

milestones following kidney transplantation. |

Table I

Key laboratory values and clinical

milestones following kidney transplantation.

| Hospital

day/follow-up day | Clinical

event/intervention | Hemoglobin

(g/dl) | Hematocrit (%) | Platelets

(x10³/µl) | Creatinine

(mg/dl) | LDH (U/l) | BUN (mg/dl) | Notes |

|---|

| Pre-Tx | Pre-transplant

laboratory tests | 12.0 | 37 | 241 | 16.2 | - | 46 | Stable baseline |

| Day 0 | Living donor kidney

transplant | - | - | - | - | - | - | Warm ischemia 5

min; cold ischemia 48 min |

| POD 2 | Routine laboratory

tests | 8.4 | 26 | 69 | 1.0 | 212 | 10 | Albumin 2.2 g/d;;

tacrolimus 2.6 ng/ml |

| POD 4 | Routine

follow-up | 8.6 | 25 | 94 | 0.9 | 191 | 9 | Tacrolimus 3.4

ng/m; |

| POD 12 | Outpatient

control | 10.7 | 34 | 401 | 1.0 | - | - | Improving

counts |

| 2nd visit | Stable | 12.0 | 36 | 333 | 1.0 | - | 13 | - |

| 3rd visit | Ultrasound: mild

collection | 12.7 | 38 | 276 | 1.0 | - | 14 | Upper pole

collection 19 cc |

| Latest visit | Staples and double

J removal | - | - | - | 1.0 | - | - | Asymptomatic |

Discussion

The present case report details a young female

patient who, on the 4th day postpartum following a cesarean

section, experienced an acute onset of hemolytic anemia,

thrombocytopenia, significant hemorrhage and acute kidney injury,

culminating in a diagnosis of pregnancy-associated HUS. HUS, a rare

TMA. It has an estimated global incidence of 2 to 3 cases per

100,000 individuals annually, and it predominantly affects children

and young adults, with incidence peaks at ages 21 and 25 uears for

males and females, respectively (28).

TMAs are categorized by their underlying mechanisms:

Primary TMAs, such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and

typical HUS (HUS-Tx), stem from intrinsic genetic defects, whereas

secondary TMAs, including aHUS, are precipitated by infections,

autoimmune conditions, or other triggers such as aHUS or

microangiopathic HUS (29). Although

rare, HUS can manifest during pregnancy or the immediate postpartum

period, particularly in genetically susceptible young women

(30). Typically emerging within the

first few days postpartum, it affects ~1 in 25,000 pregnancies.

Despite its rarity, HUS carries severe implications, with up to 70%

of affected women requiring long-term renal replacement therapy,

underscoring the need for prompt recognition to improve prognosis

(31).

The identification of HUS is challenging, as its

differential diagnosis includes all forms of TMAs, (both those

directly and indirectly mediated by the complement system), as well

as common pathologies that present with similar clinical

manifestations (5). The patient in

the case described herein presented a clinical picture consistent

with various hemolytic disorders associated with pregnancy and the

puerperium. Additionally, the history of significant bleeding

during the obstetric event is particularly noteworthy, as previous

reports have suggested that blood loss >1,500 ml in women

without a prior pathological history may indicate a diagnosis of

HUS (32).

Acute anemia is a frequent finding in postpartum HUS

and presents a broad differential etiology, often delaying initial

diagnostic suspicion (33). Renal

manifestations, including azotemia and electrolyte imbalances,

aligned with prior descriptions, yet necessitated the exclusion of

more common entities such as preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome and

hypovolemic acute kidney injury through systematic evaluation

(34).

This protocol included, for example, the

identification of abundant schistocytes on the blood smear, which

suggests microangiopathy, and an elevated level of lactate

dehydrogenase, indicative of prolonged cellular lysis (35). These findings, together with other

laboratory results, clinical signs of cellular ischemia, refractory

anemia and worsening symptoms, strongly supported the suspicion of

microangiopathy.

For this reason, the analyses of antibodies and

complement fractions were performed (36). To determine the triggering cause, the

use of the ADAMTS13 test via fluorometric assay was also warranted

(37). After evaluating the results,

the diagnosis of the patient was ultimately determined.

Additionally, it was found that complement levels were within

normal ranges (C3, 107 mg/dl; C4, 24.8 mg/dl) and ADAMTS13 activity

was 70%, effectively ruling out thrombotic thrombocytopenic

purpura. aHUS has a strong genetic basis, with mutations commonly

identified in complement regulatory genes, such as CFH, CFI, MCP,

C3 and deletions in CFHR1/3. Genetic testing is critical for

confirming diagnosis, assessing prognosis and guiding family

counseling. However, genetic analysis was not performed in the

present study due to limited availability at the Gynecology and

Obstetrics Hospital No. 15 of the Mexican Social Security

Institute. Expanding access to such testing in the future is vital

for optimizing patient management and understanding disease

pathogenesis. Given the overlapping clinical features,

distinguishing aHUS from other pregnancy-associated thrombotic

microangiopathies is crucial. HELLP syndrome typically presents

with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets before or

shortly after delivery, often associated with hypertension and

proteinuria, both of which were absent in the patient described

herein. Although severe preeclampsia is characterized by

hypertension and signs of organ dysfunction, the patient in the

present study had no hypertensive episodes or proteinuria

throughout her pregnancy or postpartum course. TTP is usually

marked by severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (<10%), neurological

symptoms and minor renal involvement; by contrast, the ADAMTS13

activity of the patient in the present study was within normal

limits (70%) and acute kidney injury was a prominent feature.

The constellation of findings, postpartum anemia,

thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury, normal ADAMTS13 activity and

confirmation of thrombotic microangiopathy on kidney biopsy,

strongly supports the diagnosis of pregnancy-associated aHUS,

effectively distinguishing it from other differential

diagnoses.

However, multiple complications arose at that time,

extending her treatment and duration of hospitalization and

necessitating subsequent outpatient follow-up while she continued

renal replacement therapy. Eculizumab was considered as a

therapeutic option; however, it was not administered due to the

presence of active infectious complications, including sepsis and

ventilator-associated pneumonia, which contraindicated its use in

this setting. Current treatment options for aHUS include plasma

exchange or infusion, immunosuppressive therapies, such as

corticosteroids and complement inhibitors such as eculizumab

(38). Eculizumab has exhibited

notable efficacy by inhibiting terminal complement activation,

reducing disease progression, and improving survival rates

(39). However, its use may be

contraindicated in patients with active infections, as was the case

here, and it is also limited by availability and cost. Plasma

exchange remains a mainstay therapy when eculizumab is unavailable

or unsuitable, although critical illness may restrict its

feasibility (40,41). Additionally, there were institutional

and resource limitations regarding its availability. As regards

plasma therapy, the patient received fresh frozen plasma infusions

and intravenous corticosteroids, which led to temporary

stabilization. Plasmapheresis (plasma exchange) was considered but

ultimately not initiated, primarily due to the patient's critical

hemodynamic status and the decision of the multidisciplinary team

prioritizing infection control and respiratory management.

The present case report highlights the rapid

clinical progression of a rare condition and emphasizes the

importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion in women

presenting with similar characteristics to facilitate prompt

treatment. This case shares a number of clinical and laboratory

features with previously reported cases of pregnancy-associated

aHUS, including rapid postpartum onset of anemia, thrombocytopenia

and acute kidney injury (30). To

further address the similarities and differences between the

present case and those previously reported, a comparative summary

is presented in Table II. This

table contrasts key aspects of presentation, laboratory findings,

complications, treatment strategies, and outcomes between our

patient and selected cases from the literature (42-45).

As demonstrated, the present case shares core features with other

pregnancy-associated aHUS presentations, such as rapid postpartum

onset of anemia, thrombocytopenia and acute kidney injury, but is

distinguished by the presence of severe complications such as

diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and ventilator-associated pneumonia,

which are rarely documented. These additional complications likely

delayed the initiation of targeted therapy, particularly complement

blockade, and may have contributed to the persistence of

dialysis-dependent renal failure, in contrast to some published

cases where earlier intervention was associated with improved

hematologic recovery and, in certain instances, partial renal

recovery.

| Table IIComparative features of the present

case and selected previously reported cases of pregnancy-associated

atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. |

Table II

Comparative features of the present

case and selected previously reported cases of pregnancy-associated

atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome.

| | Author(s) (Refs.),

year of publication |

|---|

| Feature | Present case | Saad et al

(30), 2016 | Frimat et al

(42), 2024 | Fakhouri (44), 2016 | Fakhouri et

al (45), 2021 |

|---|

| Onset | 4 Days

postpartum | Immediate

postpartum | Late pregnancy or

postpartum | Postpartum | Postpartum |

| Main clinical

features | Severe anemia,

thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage,

ventilator-associated pneumonia | Severe anemia,

thrombocytopenia, AKI | TMA signs with

anemia, thrombocytopenia, AKI | Anemia,

thrombocytopenia, AKI | Anemia,

thrombocytopenia, AKI |

| Laboratory

findings | Hb 4.6 g/dl,

schistocytes >10/HPF, creatinine 10.6 mg/dl, normal complement

levels | Similar hematologic

profile, elevated LDH, normal C3/C4 | Variable complement

abnormalities | Complement

abnormalities in subset | Complement

abnormalities in subset |

| Histopathology | TMA in acute and

chronic phases, MPGN pattern, severe arteriolonephrosclerosis | Not always

performed; when done, TMA lesions | Not always

performed; when done, TMA lesions | TMA lesions | TMA lesions |

| Complications | Diffuse alveolar

hemorrhage, ventilator-associated pneumonia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Treatment | Broad-spectrum

antibiotics, plasma, corticosteroids; delayed immunosuppression; no

Eculizumab due to complications and timing | Plasma exchange,

supportive care; some cases Eculizumab | Variable:

supportive care, plasma exchange, complement blockade | Eculizumab early in

course | Eculizumab, some

discontinuation |

| Outcome | Discharged on

dialysis, ongoing renal replacement therapy | Variable renal

recovery; some dialysis dependence | Variable renal

recovery | Hematologic

remission; variable renal recovery | Hematologic

remission; variable renal recovery |

Variability in treatment decisions reflects

differing clinical scenarios and resource availability,

highlighting the importance of individualized, multidisciplinary

care (43). In this regard, it is

worth noting that the use of eculizumab and other C5 inhibitors, (a

humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits terminal complement

activity) has been shown to promote symptom resolution and improve

survival, although their impact on renal function is more complex

to analyze (44,45). In the case described herein, the

complexity of the complications and associated pathologies made it

difficult to determine their precise impact; however, a prompter

diagnosis may have reduced the morbidity of the patient. Although

the present case report highlights key aspects of aHUS management,

its findings are limited to a single patient experience and may not

be generalizable. Larger case series and systematic studies are

required to establish definitive clinical guidelines. Other

limitations of the present case report include the absence of

genetic testing results and limited long-term follow-up data beyond

initial discharge. Future studies are thus required to focus on

improving access to genetic diagnostics and on long-term outcomes

in pregnancy-associated aHUS. Heightened awareness and timely

diagnosis remain crucial to improve patient prognosis and guide

therapy. Finally, an important limitation of the present report is

the absence of peripheral blood smear images, kidney biopsy

histopathology annotations and laboratory trend graphs due to

institutional constraints, which would have further supported the

diagnosis.

In conclusion, TMAs such as HUS, although rare,

confer high morbidity and mortality, often precipitated by

pregnancy or puerperal sepsis. The present case report describes a

case of postpartum HUS confirmed by renal biopsy following a

comprehensive workup including negative antibody and complement

tests and ADAMTS13 analysis, which excluded alternative diagnoses.

Initial management with plasmapheresis and intravenous steroids

yielded favorable outcomes despite in-hospital complications. Given

the diagnostic complexity, ruling out differential diagnoses and

securing histopathological confirmation remain essential for

effective management.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KPQB, HARL, LFMB, AVU, RAAM and JASO participated

equally in the preparation of this manuscript, both in the medical

care process of the patient and during data collection, literature

search, information synthesis, and writing of this manuscript. KPQB

and HARL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent for

participation

The present study was performed in accordance with

the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, 1964.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for inclusion in the

study. Ethics approval was waived by the local committee as no

personal data were used.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present case report and any

related images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Afshar-Kharghan V: Atypical hemolytic

uremic syndrome. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Prog. 2016:217–225.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Salvadori M and Bertoni E: Update on

hemolytic uremic syndrome: Diagnostic and therapeutic

recommendations. World J Nephrol. 2:56–76. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jokiranta TS: HUS and atypical HUS. Blood.

129:2847–2856. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gasser C, Gautier E, Steck A, Siebenmann

RE and Oechslin R: Hemolytic-uremic syndrome: Bilateral necrosis of

the renal cortex in acute acquired hemolytic anemia. Schweiz Med

Wochenschr. 85:905–909. 1955.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lee H, Kang E, Kang HG, Kim YH, Kim JS,

Kim HJ, Moon KC, Ban TH, Oh SW, Jo SK, et al: Consensus regarding

diagnosis and management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Korean J Intern Med. 35:25–40. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Aldharman SS, Almutairi SM, Alharbi AA,

Alyousef MA, Alzankrany KH, Althagafi MK, Alshalahi EE, Al-Jabr KH,

Alghamdi A and Jamil SF: The Prevalence and incidence of hemolytic

uremic syndrome: A systematic review. Cureus.

15(e39347)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Roumenina LT, Loirat C, Dragon-Durey MA,

Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Sautes-Fridman C and Fremeaux-Bacchi V:

Alternative complement pathway assessment in patients with atypical

HUS. J Immunol Methods. 365:8–26. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Rondeau E, Ardissino G, Caby-Tosi MP,

Al-Dakkak I, Fakhouri F, Miller B and Scully M: Global aHUS

Registry. Pregnancy in women with atypical hemolytic uremic

syndrome. Nephron. 146:1–10. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ávila A, Cao M, Espinosa M, Manrique J and

Morales E: Recommendations for the individualised management of

atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in adults. Front Med (Lausanne).

10(1264310)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yan K, Desai K, Gullapalli L, Druyts E and

Balijepalli C: Epidemiology of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome:

A systematic literature review. Clin Epidemiol. 12:295–305.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Yerigeri K, Kadatane S, Mongan K, Boyer O,

Burke LLG, Sethi SK, Licht C and Raina R: Atypical Hemolytic-uremic

syndrome: Genetic basis, clinical manifestations, and a

multidisciplinary approach to management. J Multidiscip Healthc.

16:2233–2249. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhang K, Lu Y, Harley KT and Tran MH:

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: A brief review. Hematol Rep.

9(7053)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bayer G, von Tokarski F, Thoreau B,

Bauvois A, Barbet C, Cloarec S, Mérieau E, Lachot S, Garot D,

Bernard L, et al: Etiology and outcomes of thrombotic

microangiopathies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 14:557–566.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sheerin NS and Glover E: Haemolytic uremic

syndrome: Diagnosis and management. F1000Res 8: F1000 Faculty

Rev-1690, 2019.

|

|

15

|

Scully M and Goodship T: How I treat

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and atypical haemolytic uraemic

syndrome. Br J Haematol. 164:759–766. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Domínguez-Vargas A, Ariño F, Silva D,

González-Tórres HJ, Aroca-Martinez G, Egea E and Musso CG:

Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: A case

report with MCP gene mutation and successful eculizumab treatment.

AJP Rep. 14:e96–e100. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Tseng MH, Lin SH, Tsai JD, Wu MS, Tsai IJ,

Chen YC, Chang MC, Chou WC, Chiou YH and Huang CC: Atypical

hemolytic uremic syndrome: Consensus of diagnosis and treatment in

Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 122:366–375. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ardissino G, F, Possenti I, Testa S,

Consonni D, Paglialonga F, Salardi S, Borsa-Ghiringhelli N, Salice

P, Tedeschi S, et al: Early volume expansion and outcomes of

hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatrics: Dec 7, 2016 (Epub ahead of

print). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2153.

|

|

19

|

Leon J, LeStang MB, Sberro-Soussan R,

Servais A, Anglicheau D, Frémeaux-Bacchi V and Zuber J:

Complement-driven hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Hematol. 98

(Suppl 4):S44–S56. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Valoti E, Alberti M, Iatropoulos P, Piras

R, Mele C, Breno M, Cremaschi A, Bresin E, Donadelli R, Alizzi S,

et al: Rare functional variants in complement genes and Anti-FH

Autoantibodies-associated aHUS. Front Immunol.

10(853)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Piras R, Valoti E, Alberti M, Bresin E,

Mele C, Breno M, Liguori L, Donadelli R, Rigoldi M, Benigni A, et

al: CFH and CFHR structural variants in atypical Hemolytic Uremic

Syndrome: Prevalence, genomic characterization and impact on

outcome. Front Immunol. 13(1011580)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Valério P, Barreto JP, Ferreira H, Chuva

T, Paiva A and Costa JM: Thrombotic microangiopathy in oncology-a

review. Transl Oncol. 14(101081)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Schwotzer N, Frémeaux-Bacchi V and

Fakhouri F: Hemolytic uremic syndrome: A question of terminology.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 18:831–833. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wildes DM, Harvey S, Costigan CS, Sweeney

C, Twomey É, Awan A and Gorman KM: Eculizumab in STEC-HUS: A

paradigm shift in the management of pediatric patients with

neurological involvement. Pediatr Nephrol. 39:315–324.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Stefanovic V: The Extended use of

eculizumab in pregnancy and complement activation(-)associated

diseases affecting maternal, fetal and neonatal kidneys-the future

is now? J Clin Med. 8(407)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Timmermans SAMEG, Abdul-Hamid MA,

Potjewijd J, Theunissen ROMFIH, Damoiseaux JGMC, Reutelingsperger

CP and van Paassen P: Limburg Renal Registry. C5b9 formation on

endothelial cells reflects complement defects among patients with

renal thrombotic microangiopathy and severe hypertension. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 29:2234–2243. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Secretaría de Salud México: Frequently

asked questions: Seasonal influenza [Internet]. Mexico City:

Government of Mexico. In Spanish. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/preguntas-frecuentes-influenzaestacional.

|

|

28

|

Kottke-Marchant K: Diagnostic approach to

microangiopathic hemolytic disorders. Int J Lab Hematol. 39 (Suppl

1):S69–S75. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Avila Bernabeu AI, Cavero Escribano T and

Cao Vilarino M: Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: New challenges

in the complement blockage era. Nephron. 144:537–549.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Saad AF, Roman J, Wyble A and Pacheco LD:

Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. AJP Rep.

6:e125–e128. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Konopásek P and Zieg J: Eculizumab use in

patients with pneumococcal-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome and

kidney outcomes. Pediatr Nephrol. 38:4209–4215. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Miyazaki Y, Fukuda M, Hirayu N, Nabeta M

and Takasu O: Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic

syndrome successfully treated with ravulizumab: A case report.

Cureus. 16(e54207)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Mirza M, Sadiq N and Aye C:

Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and

Life-long kidney failure. Cureus. 14(e25655)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Che M, Moran SM, Smith RJ, Ren KYM, Smith

GN, Shamseddin MK, Avila-Casado C and Garland JS: A case-based

narrative review of pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic

syndrome/complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy. Kidney

Int. 105:960–970. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Java A: Atypical hemolytic uremic

syndrome: Diagnosis, management, and discontinuation of therapy.

Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2024:200–205.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Gaire S, Shrestha M, Bhattarai CD,

Dhungana S, Gyawali S and Bajgain A: Hemolytic uremic syndrome: A

case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 61:472–474. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Raina R, Krishnappa V, Blaha T, Kann T,

Hein W, Burke L and Bagga A: Atypical Hemolytic-uremic syndrome: An

update on pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Ther Apher

Dial. 23:4–21. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kaplan BS, Ruebner RL, Spinale JM and

Copelovitch L: Current treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic

syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 3:34–45. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Cofiell R, Kukreja A, Bedard K, Yan Y,

Mickle AP, Ogawa M, Bedrosian CL and Faas SJ: Eculizumab reduces

complement activation, inflammation, endothelial damage,

thrombosis, and renal injury markers in aHUS. Blood. 125:3253–3262.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yang L, Liu F, Li X, He L, Gu Y, Sun M and

Liu Z and Liu Z: Plasma exchange combined with eculizumab in the

management of atypical hemolytic uremic in pediatric patients: A

case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 104(e42090)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Loirat C, Garnier A, Sellier-Leclerc AL

and Kwon T: Plasmatherapy in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Semin Thromb Hemost. 36:673–81. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Frimat M, Gnemmi V, Stichelbout M, Provôt

F and Fakhouri F: Pregnancy as a susceptible state for thrombotic

microangiopathies. Front Med (Lausanne). 11(1343060)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

De Meyer F, Chambaere K, Van de Velde S,

Van Assche K, Beernaert K and Sterckx S: Factors influencing

obstetricians' acceptance of termination of pregnancy beyond the

first trimester: A qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics.

26(32)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Fakhouri F: Pregnancy-related thrombotic

microangiopathies: Clues from complement biology. Transfus Apher

Sci. 54:199–202. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Fakhouri F, Fila M, Hummel A, Ribes D,

Sellier-Leclerc AL, Ville S, Pouteil-Noble C, Coindre JP, Le

Quintrec M, Rondeau E, et al: Eculizumab discontinuation in

children and adults with atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome: A

prospective multicenter study. Blood. 137:2438–2449.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|