1. Introduction

Invasive candidiasis (IC) is a life-threatening

fungal infection that is caused mainly by Candida albicans

and other non-albicans Candida (NAC) species, including

Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, Candida

tropicalis and Candida krusei. It manifests as

candidemia or disseminated infection involving multiple organs,

such as the liver, spleen, heart and central nervous system.

Diagnosis is complicated due to non-specific symptoms such as

fever, hypotension and multi-organ dysfunction. Blood cultures are

the gold standard for diagnosis, but have limited sensitivity. The

usual treatment involves the use of echinocandins or fluconazole,

while the surgical removal of infected medical devices is also

pivotal for patient management purposes (1,2).

IC is associated with a very high mortality in

intensive care units (ICUs) of 30-50%, which necessitates rapid

identification and treatment with appropriate antifungals. The

emergence of antifungal resistance among NAC species has

complicated management. Thus, infection control strategies,

antifungal stewardship programs, catheter care and the timely

removal of infected central venous lines are required to reduce the

incidence of IC in ICUs. Among the common fungal infections

acquired in ICUs worldwide, Candida species rank 4th among

bloodstream pathogens encountered by hospitalized patients, with

many being NAC species resistant to fluconazole and other

antifungals. The global incidence of IC exhibits a wide variation,

with higher rates in regions with limited healthcare resources and

high antibiotic use. Another significant contributor to mortality

is the delay in diagnosis and inappropriate antifungal therapy in

patients in ICUs whose underlying conditions are already severe

(1-4).

While the recent comprehensive review by Soriano

et al (1) addressed current

clinical challenges and unmet needs in invasive candidiasis across

adult populations, the present review focuses specifically on

critically ill patients in ICUs. The present review highlights

ICU-specific risk factors, diagnostic limitations, therapeutic

complexities due to organ dysfunction and invasive devices, and

unique management strategies. By adopting this focused perspective,

the present review complements prior research and provides

intensivists with practical, ICU-centered insights into the

management of invasive candidiasis (3).

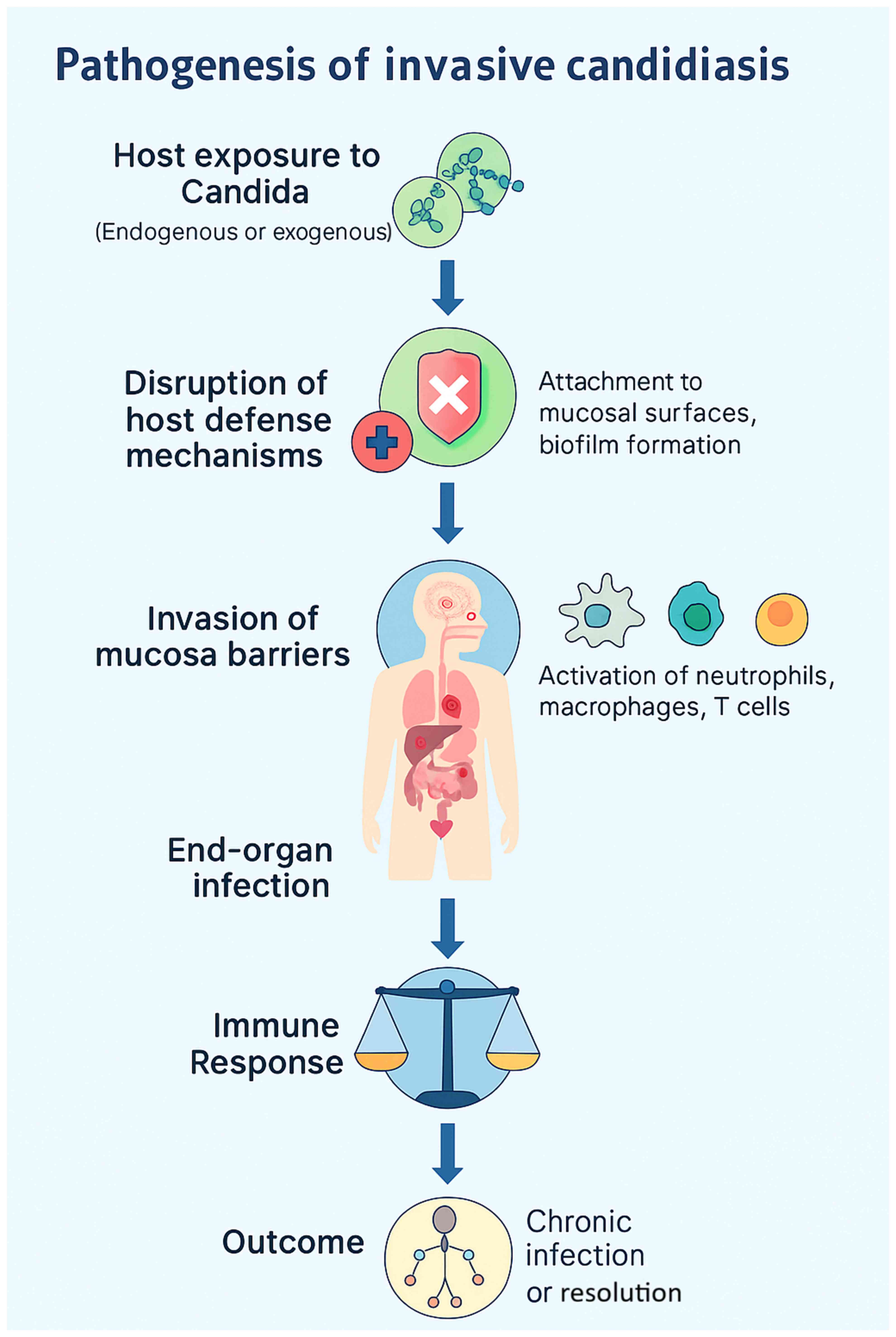

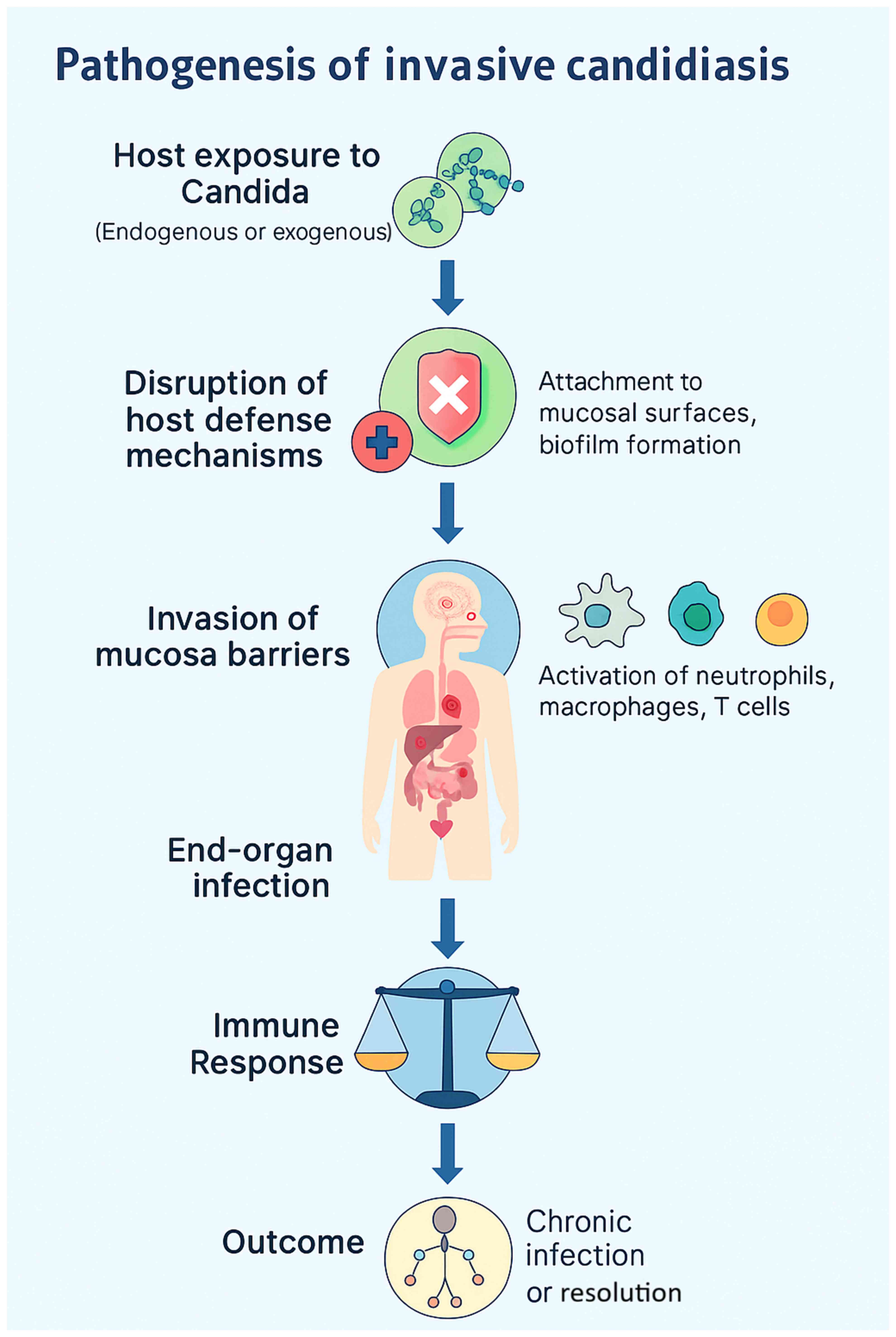

2. Pathogenesis of invasive candidiasis

IC, characterized by the ability to induce

widespread systematic and immune evasion, is a disorder

precipitated by the interaction of colonization, epithelial

invasion, bloodstream dissemination and immune escape (5). Candida species are part of the

normal commensal flora of the skin, gastrointestinal tract and

other mucosal surfaces; these sites function as endogenous

reservoirs rather than sources of external acquisition. Under

normal conditions, host immunity and bacterial microbiota maintain

a balanced state that prevents fungal overgrowth. However, factors

such as immunodepression, broad-spectrum antibiotic use, critical

illness and the insertion of indwelling medical devices disrupt

this equilibrium, enabling Candida to shift from commensal

to pathogen (4-6).

The invasive process begins with opportunistic overgrowth in

response to host defense alterations (as illustrated in Fig. 1), followed by adhesion to epithelial

cells or medical devices through surface adhesins (5,6). A

critical virulence step is the yeast-to-hyphal transition, which

allows penetration of mucosal barriers. Hyphal forms secrete

hydrolytic enzymes, including secreted aspartyl proteases and

phospholipases, leading to tissue damage and deeper invasion

(5). Once the mucosal barrier is

compromised, Candida can translocate into the bloodstream,

resulting in candidemia. Hematogenous dissemination permits

colonization of distant organs such as the liver, spleen, kidneys

and brain (4,5). Biofilm formation, particularly on

central venous catheters, contributes to persistent infection by

enhancing resistance to antifungal therapy and impairing immune

clearance (4,6). Candida employs several immune

evasion strategies, including antigenic variation, secretion of

immunomodulatory molecules and resistance to oxidative stress

(5,6). Host factors, such as neutropenia,

corticosteroid therapy and impaired T-cell responses significantly

increase the risk of systemic dissemination, culminating in sepsis,

multiorgan failure and high mortality in critically ill patients

(4-7).

| Figure 1Pathogenesis of invasive candidiasis.

Schematic flowchart illustrating the sequence from the initial

colonization of mucosal surfaces and skin, through the disruption

of host defenses (e.g., broad-spectrum antibiotics,

immunosuppression, total parenteral nutrition), adhesion and

biofilm formation on indwelling devices (central venous catheters),

yeast-to-hyphae morphogenesis with the secretion of hydrolytic

enzymes (secreted aspartyl proteases and phospholipases), mucosal

invasion and translocation into the bloodstream (candidemia),

hematogenous dissemination to distant organs (liver, spleen,

kidneys and brain), immune evasion mechanisms (antigenic variation,

oxidative stress resistance, modulation of host response), and the

resulting clinical outcomes including sepsis, multi-organ failure,

and high mortality rates in intensive care units. |

Risk factors

IC in patients in ICUs is strongly associated with

multiple predisposing factors, including the prolonged use of

broad-spectrum antibiotics, central venous catheterization,

mechanical ventilation, parenteral nutrition, renal replacement

therapy, corticosteroid therapy and underlying immunosuppression.

Recent systematic reviews confirm that these risk factors

significantly increase susceptibility to candidemia and invasive

fungal disease in critically ill patients (6-8). A

summary of the key ICU-specific risk factors for IC is presented in

Table I.

| Table IRisk factors: Key ICU-specific risk

factors for invasive candidiasis, including device-related,

pharmacological and host-related contributors. |

Table I

Risk factors: Key ICU-specific risk

factors for invasive candidiasis, including device-related,

pharmacological and host-related contributors.

| Risk factor | Description |

|---|

| Immunocompromised

state | Conditions

including HIV/AIDS, cancer, and other disorders involving

immunosuppressive therapies (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy)

reduce the ability of the body to oppose infections. |

| Diabetes

mellitus | High blood sugar

and insulin resistance may enhance Candida growth,

particularly in patients with uncontrolled glucose levels. |

| Antibiotic use | Broad-spectrum

antibiotics disrupt the normal microbiota, promoting Candida

overgrowth. |

| Indwelling medical

devices | Catheters,

prosthetics, and central venous lines provide surfaces for

Candida adherence, increasing the risk of infection. |

| Recent surgery or

trauma | Surgical

interventions or mucosal injuries may create entry points for

Candida invasion into deeper tissues. |

| Prolonged periods

of hospitalization | Longer

hospitalization periods increase exposure to hospital-acquired

infections and invasive devices. |

| Corticosteroid

therapy | Long-term steroid

use alters immune function, favoring Candida growth. |

| Pregnancy | Hormonal changes

during pregnancy alter vaginal pH, predisposing women to vaginal

candidiasis. |

| High estrogen

levels | Estrogen (e.g.,

oral contraceptives) may displace normal vaginal flora,

facilitating Candida overgrowth. |

| Obesity | Excess body weight,

particularly abdominal fat, creates moist environments favorable

for fungal growth. |

| Poor oral

hygiene | Inadequate oral

care predisposes to oral Candida overgrowth (oral thrush). |

| Malnutrition/poor

diet | Micronutrient

deficiencies impair immune function, increasing susceptibility to

infection. |

| Age | Infants, elderly

persons, and immunocompromised patients are more susceptible. |

|

Chemotherapy/radiation | Cancer therapies

weaken immune defenses, predisposing to infection. |

| Intravenous drug

use (IVDU) | Contaminated

needles or unsterile practices may introduce Candida into

the bloodstream, causing systemic infection. |

Symptoms

The clinical presentation of IC in patients in the

ICU is usually non-specific, often mimicking bacterial sepsis.

Common features include persistent fever despite broad-spectrum

antibiotics, hypotension, signs of septic shock, multi-organ

dysfunction, and occasionally, the focal involvement of organs such

as the liver, spleen, or kidneys (4-9).

These manifestations are summarized in Table II for clarity.

| Table IISymptoms: Common clinical features of

invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients, highlighting

non-specific symptoms that often mimic bacterial sepsis. |

Table II

Symptoms: Common clinical features of

invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients, highlighting

non-specific symptoms that often mimic bacterial sepsis.

| Symptom

type/site | Symptoms |

|---|

| Systemic

symptoms | Persistent fever,

chills, hypotension, tachycardia, fatigue, sepsis-like symptoms

(severe cases). |

| Bloodstream

Infection (candidemia) | Persistent fever,

positive blood cultures for Candida, sepsis (fever, chills,

low blood pressure). |

| Endocarditis

(heart) | Fever, heart

murmurs, embolic phenomena (e.g., stroke, skin lesions). |

| Ophthalmic

(endophthalmitis) | Vision changes, eye

pain, redness. |

| Renal

(kidneys) | Fever, flank pain,

dysuria, hematuria. |

| Hepatosplenic

candidiasis | Abdominal pain,

jaundice, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver). |

| Peritonitis

(abdomen) | Abdominal

tenderness, distension, fever. |

| Pulmonary

(lungs) | Respiratory

distress if lungs are involved. |

| Gastrointestinal

symptoms | Nausea, vomiting

(if digestive tract is affected). |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis remains challenging due to the

non-specific clinical features and the limited sensitivity of blood

cultures. Culture-based methods remain the gold standard but

require up to 72 h for results. Non-culture-based assays, including

(1→3)-β-D-glucan (BDG), mannan antigen/anti-mannan antibody and

PCR-based tests, provide a more rapid detection, while advanced

platforms, such as the T2Candida panel allow for rapid species

identification directly from blood samples (9-11).

The strengths and limitations of available diagnostic modalities

are summarized in Table III.

| Table IIIDiagnostic modalities for invasive

candidiasis: Performance characteristics, turnaround time and

limitations in intensive care unit settings. |

Table III

Diagnostic modalities for invasive

candidiasis: Performance characteristics, turnaround time and

limitations in intensive care unit settings.

| Diagnostic

method | Description |

|---|

| Clinical

Evaluation | Detailed history

and physical examination, particularly in immunocompromised

patients (cancer, diabetes, transplant). |

| Blood cultures | Gold standard for

candidemia; samples collected before antifungal initiation. |

| Urine culture | Used in suspected

renal involvement (candiduria). |

| Tissue biopsy and

culture | Obtained from

affected organs (liver, kidney, heart) for definitive

diagnosis. |

| PCR testing | Detects

Candida DNA in blood or body fluids. |

| Serological

tests | Mannan/anti-mannan

antibodies and β-D-glucan test (fungal cell wall component). |

| Imaging

analyses | Computed tomography

scan or chest X-ray for pulmonary or abdominal involvement. |

| Endoscopy | Used for

gastrointestinal candidiasis to visualize mucosal lesions. |

| Microscopic

examination | Direct microscopy

of tissue/fluid (e.g., abscess or peritoneal fluid) for

yeasts/pseudohyphe. |

| Antigen

detection | Detection of

Candida antigens in serum or body fluids, adjunctive

diagnostic tool. |

3. Management of invasive candidiasis

The management of IC in the ICU is built upon three

essential principles: The timely initiation of empiric antifungal

therapy, targeted treatment tailored to pathogen identification and

susceptibility results, and effective source control. These

pillars, supported by careful monitoring and supportive care,

remain the cornerstone for improving the survival of critically ill

patients. The early initiation of empiric therapy is crucial, as

delays are consistently associated with increased morbidity and

mortality rates. Echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin and

anidulafungin) are generally recommended as first-line agents in

this setting, owing to their broad antifungal spectrum, fungicidal

activity against the majority of Candida species and

favorable safety profile. In hemodynamically stable patients

without prior azole exposure and with a high likelihood of

Candida albicans infection, fluconazole may be considered as

an alternative. Amphotericin B, while highly effective, is

generally reserved for patients with resistant species infection or

intolerance to other agents, given its nephrotoxicity and

infusion-related side-effects (12-14).

Once the infecting species and susceptibility

profile are available, de-escalation to targeted therapy is

essential. Candida albicans is usually susceptible to

fluconazole, which remains an effective step-down option, whereas

non-albicans species such as Candida glabrata and Candida

krusei often necessitate continued echinocandin or amphotericin

B therapy due to resistance patterns. This highlights the

importance of routine susceptibility testing, which allows

clinicians to optimize therapy and reduce the risk of treatment

failure or resistance emergence (12-15).

The recommended duration of antifungal therapy is

typically at least 14 days following the documented clearance of

Candida from the bloodstream and the resolution of clinical

signs and symptoms. However, deeper foci of infection, such as

endocarditis, osteomyelitis, or intra-abdominal abscesses may

require extended courses of therapy lasting several weeks. The

removal of central venous catheters or other indwelling devices

implicated as the source of infection is critical, as antifungal

therapy alone is often insufficient in the presence of

biofilm-associated colonization. Similarly, surgical drainage or

debridement may be required for abscesses or localized invasive

disease (12,15-17).

Supportive care plays an equally critical role in

management. This includes hemodynamic stabilization, glycemic

control (particularly in diabetic patients receiving

corticosteroids), nutritional optimization and organ support

measures, as needed. Regular monitoring with repeat blood cultures,

imaging analyses to evaluate persistent infection, and the

laboratory surveillance of renal and hepatic function is essential

to assess the treatment response and mitigate drug-related

toxicities (14-17).

In summary, the optimal management of invasive

candidiasis in the ICU requires an integrated approach that

combines the rapid initiation of empiric antifungal therapy,

adjustment based on pathogen-directed susceptibility, effective

source control and comprehensive supportive care. Despite these

well-established principles, clinicians continue to face

substantial barriers that compromise timely diagnosis, appropriate

therapy and patient outcomes.

4. Challenges in the management of invasive

candidiasis in the ICU

The management of IC in critically ill patients

remains particularly challenging due to the interplay between host

factors, diagnostic limitations, therapeutic complexity and

healthcare system constraints. Patients in ICUs frequently present

with multiple organ dysfunction (renal, hepatic, or

cardiovascular), that not only complicates the course of illness,

but also alters antifungal pharmacokinetics, necessitating dose

adjustments and vigilant monitoring for toxicity. Immunocompromised

states, whether due to hematologic malignancies, organ

transplantation, corticosteroid therapy, or HIV infection, further

diminish host defenses and predispose patients to persistent or

recurrent infections. Delayed diagnosis continues to be one of the

most crucial obstacles. Clinical manifestations are non-specific

fever, hypotension, or an unexplained clinical deterioration and

are easily confounded with bacterial sepsis or other ICU-related

infections. While blood culture remains the gold standard for

candidemia, it is a lengthy process, requiring 48-72 h for results.

This diagnostic delay, compounded by the limited availability of

advanced molecular or antigen-based tests in numerous ICUs, often

postpones the initiation of effective antifungal therapy, thereby

worsening outcomes (17,18).

Antifungal resistance represents another growing

concern, particularly among NAC species, such as Candida

glabrata and Candida krusei, which exhibit a reduced

susceptibility to azoles. Although echinocandins have emerged as

effective alternatives, resistance, albeit uncommon, has been

reported. The absence of oral echinocandin formulations also

complicates step-down therapy and prolongs outpatient management.

Drug-drug interactions and polypharmacy further complicate the care

of patients in ICUs, as antifungal agents may potentiate toxicities

or alter the efficacy of other commonly administered drugs,

including immunosuppressants, vasopressors and nephrotoxic

antimicrobials (19-22).

The presence of invasive medical devices, including

central venous catheters, endotracheal tubes and urinary catheters,

also amplifies the risk of biofilm-associated infections that are

poorly responsive to antifungal therapy alone. While device removal

is critical for achieving a cure, this may be difficult or

impossible in critically ill patients who depend on these

interventions for survival. Such challenges, compounded by the lack

of ICU-specific clinical guidelines for antifungal dosing, the

duration of therapy and source control strategies, often leave

clinicians to rely on individualized decision-making rather than

standardized evidence-based protocols (22-24).

Beyond clinical complexities, IC imposes a

significant economic burden, primarily due to prolonged periods of

hospitalization in the ICU, repeated interventions and the high

cost of antifungal agents (17,18,20).

Prolonged periods of hospitalization, device-related procedures and

the need for intensive supportive care substantially increase

direct and indirect healthcare expenditures. Furthermore, the

healthcare-associated nature of IC underscores the importance, but

also the difficulty, of prevention in ICUs, where factors such as

overcrowding, frequent use of invasive devices, and extended

hospitalization create an environment conducive to nosocomial

transmission (17,18,21).

The psychological and emotional toll on patients is

another underrecognized dimension. Extended critical illness,

invasive procedures, uncertain prognoses and the high risk of

complications contribute to anxiety, depression and psychological

distress in patients and their families, further compounding the

burden of IC in ICU settings (20).

Collectively, these clinical, economic and

psychosocial challenges highlight the urgent need for earlier

diagnosis, individualized therapy, improved infection prevention,

and ICU-specific clinical guidance to improve outcomes in this

vulnerable population (17,18,21).

Notably, the growing recognition of these

limitations has catalyzed significant innovations across

diagnostics, therapeutics and preventive strategies. Novel

diagnostic tools include rapid non-culture-based assays such as

(1→3)-β-D-glucan, mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibody tests,

PCR-based platforms, and the T2Candida panel. These modalities

significantly reduce the time to detection compared with blood

cultures, enabling earlier initiation of targeted therapy (19-24).

The T2Candida panel, in particular, can detect Candida DNA

directly from whole blood within 3-5 h with high sensitivity and

specificity, representing a major advance in early diagnosis

(23,24).

On the therapeutic front, newer antifungal agents

and treatment strategies are reshaping management. Echinocandins

remain first-line agents; however, the recent development of new

triazoles, such as isavuconazole and investigational agents such as

rezafungin and ibrexafungerp provides expanded options, including

improved pharmacokinetics and oral formulations for step-down

therapy (25-29).

Combination antifungal therapy is being explored to overcome

resistance among non-albicans Candida species (28,29).

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) for agents, such as voriconazole

and posaconazole further enables individualized dosing in

critically ill patients with altered pharmacokinetics (30-32).

In parallel, infection prevention and stewardship

programs have become central components of management. These

include strict catheter care protocols, antifungal prophylaxis in

selected high-risk populations, and antifungal stewardship

initiatives that promote judicious drug use and de-escalation based

on local epidemiology and biomarker data (30,31,33-41).

Collectively, these innovations in diagnostics, therapeutics and

prevention represent a paradigm shift toward more rapid, tailored

and multidisciplinary approaches to IC in the ICU (17-24,28-31).

5. Advances in the management of invasive

candidiasis in the ICU

In recent years, notable advances have been made to

address the challenges encountered in the management of IC,

spanning from earlier diagnostic approaches to novel therapeutic

strategies and multidisciplinary care models. Early recognition

remains the cornerstone of improved outcomes, and several

non-culture diagnostic tools have markedly shortened the diagnostic

window compared with conventional blood cultures. Blood cultures,

although considered the reference standard, have limited

sensitivity (~50%) and require 24-72 h to yield positive results,

with performance declining in deep-seated infections without

candidemia (17,18). By contrast, non-culture assays enable

earlier the initiation of antifungal therapy, often before overt

clinical manifestations, thereby reducing diagnostic delays and

potentially improving survival.

Among these, BDG testing demonstrates a pooled

sensitivity of ~70-80% and a specificity of ~80-85%, with results

available within hours; however, its specificity is reduced in the

ICU due to false positives associated with hemodialysis,

intravenous immunoglobulins, albumin and certain antibiotics,

rendering it most useful as a rule-out test (19,20).

Mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibody assays, when used in

combination, provide improved sensitivity (~83%) and specificity

(~86%), often yielding positive results several days before blood

cultures, though their availability remains variable (21). PCR-based assays yield higher pooled

sensitivity (~95%) and specificity (~92%) and provide rapid

turnaround, but lack standardization and are constrained by costs

and accessibility (22). Recently,

the T2Candida panel, which uses magnetic resonance to directly

detect Candida DNA from blood within 3-5 h, has demonstrated

a sensitivity of ~89-100% and a specificity of ~96-99% for the most

common species; however, it is limited by high costs, instrument

availability and a restricted species panel (24). The practical utility of these assays

lies in combining them with culture-based methods to accelerate

rule-in or rule-out decisions, while ensuring species

identification and susceptibility testing for definitive

management.

Therapeutically, echinocandins have become the

standard of care for empiric treatment due to their potent activity

and favorable safety profile. The development of newer triazoles,

such as isavuconazole, provides additional options, including oral

formulations for step-down therapy. Combination regimens and novel

antifungal agents under investigation are being explored to counter

emerging resistance and broaden the therapeutic armamentarium

(28,29). In parallel, pharmacokinetic and

pharmacodynamic optimization has gained importance in critically

ill patients, whose altered physiology often disrupts drug

distribution and clearance. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM),

particularly for agents, such as voriconazole, enables

individualized dosing and enhances treatment precision, while

minimizing toxicity (37-41).

Addressing biofilm-associated infections has also

emerged as a key focus area. Biofilm formation on indwelling

medical devices contributes to persistent infection and therapeutic

failure; current research is investigating antifungal agents with

biofilm-disruptive properties and innovative device technologies to

reduce colonization and infection risk (4,6,8,12,13,28,29).

Complementary to pharmacologic advances, infection

prevention and control measures play a pivotal role. These include

antifungal stewardship programs, stricter catheter care protocols,

and bundled prevention strategies, all of which have been shown to

reduce ICU-acquired Candida infections (17,18,30,31).

Stewardship initiatives emphasize judicious antifungal use, early

de-escalation based on clinical and microbiological data, and the

integration of local epidemiology and biomarkers into therapeutic

decision-making, thereby reducing antifungal resistance and

improving patient outcomes (8,28,30,31).

Emerging therapies extend beyond antifungal drugs themselves.

Immunomodulatory approaches, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating

factor and experimental vaccines against Candida species are

under investigation to augment host defenses, particularly in

immunocompromised patients in the ICU (30,31).

Furthermore, the adoption of multidisciplinary teams, including

infectious disease specialists, intensivists, pharmacists and

microbiologists has improved diagnostic accuracy, treatment

optimization and stewardship.

Recent developments in predictive scoring systems,

such as the Candida Score and APACHE II-based models, now allow

clinicians to stratify patients and prioritize early therapy for

those at greatest risk. Simultaneously, artificial intelligence and

machine learning are being applied for predictive modeling, early

detection and risk assessment of invasive candidiasis, providing a

personalized and data-driven approach to ICU care (32,33).

Finally, host factors and comorbidities have become

integral to management. Optimizing glycemic control, managing renal

dysfunction, and minimizing unnecessary immunosuppression are

essential strategies to reduce susceptibility and enhance response

to therapy. Prophylactic antifungal use in select high-risk ICU

populations, such as patients undergoing abdominal surgery, those

with hematologic malignancies, or those undergoing transplantation

remains an area of active investigation, although concerns

regarding resistance, costs and toxicity necessitate cautious

application. Collectively, these advances signal a paradigm shift

toward earlier, more individualized and multidisciplinary care,

integrating diagnostics, therapeutics, infection prevention and

host optimization to improve the outcomes of patients with ICU

(34-36).

6. Diagnostic modalities in the ICU

Blood culture remains the gold standard for the

diagnosis of candidemia; however, its performance in critically ill

patients is suboptimal. Sensitivity is estimated at only ~50%, and

the time to positivity can range from 24-72 h, which delays

targeted therapy and limits its value in deep-seated candidiasis

without bloodstream involvement (17,18).

Despite these drawbacks, cultures provide species identification

and susceptibility testing, which remain indispensable for

tailoring antifungal therapy.

To overcome the limitations of culture, several

non-culture-based assays have been introduced. The BDG assay is

among the most widely used biomarkers, with a pooled sensitivity of

~70-80% and specificity of ~80-85%, and a turnaround time of hours,

once samples are processed. In the ICU, however, false positives

are common due to exposure to hemodialysis membranes, intravenous

immunoglobulin, albumin infusions and certain broad-spectrum

antibiotics. As such, BDG is particularly valuable as a rule-out

test in patients with low-to-intermediate pre-test probability

rather than as a confirmatory tool (19,20).

Mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibody assays

provide another non-culture diagnostic approach, with diagnostic

yield improving significantly when both are combined. Multiple

studies have reported a sensitivity of ~83-89% and a specificity of

86-90%, with serological positivity often preceding blood culture

results by several days (21,42,43).

However, test performance varies across Candida species, and

availability remains inconsistent across ICU settings (21). Molecular methods, particularly

PCR-based assays, have demonstrated a high pooled sensitivity

(~95%) and specificity (~92%) for IC, with results available within

24 h. These assays allow for the much earlier initiation of

antifungal therapy, although the lack of assay standardization,

variable performance across platforms and higher costs limit

widespread adoption (22).

A notable advancement in this field is the T2Candida

panel, which detects Candida DNA directly from whole blood using

magnetic resonance technology. The assay provides results within

3-5 h and covers the five most common Candida species, with

a reported sensitivity of ~89-100% and specificity of ~96-99%.

Despite these advantages, its clinical utility is tempered by high

costs, limited species coverage and restricted availability in

numerous ICUs (23). Taken together,

culture- and non-culture-based diagnostics are best viewed as

complementary rather than competitive. While blood cultures remain

essential for definitive identification and susceptibility testing,

non-culture assays, such as BDG, mannan antigen and anti-mannan

antibody assays, PCR and T2Candida can greatly accelerate

diagnosis, facilitate the earlier initiation or de-escalation of

antifungal therapy, and improve the outcomes of critically ill

patients. The optimal diagnostic approach in the ICU likely

involves a multimodal strategy, integrating rapid biomarkers with

traditional cultures and guided by clinical risk stratification to

balance speed, accuracy and cost-effectiveness.

7. Dosing and therapeutic drug monitoring in

the ICU

TDM has become an increasingly valuable tool in

optimizing antifungal therapy in critically ill patients, in whom

altered pharmacokinetics can result in either subtherapeutic

exposure or toxicity (23,40). Although not all antifungals require

TDM, it is particularly indicated for agents with narrow

therapeutic windows, a high interpatient variability, or

concentration-dependent toxicities (26,29).

Voriconazole is the most well-established candidate, as trough

concentrations are closely associated with both efficacy and

toxicity. Subtherapeutic levels (<1-2 µg/ml) are associated with

treatment failure, while supratherapeutic levels (>5-6 µg/ml)

increase the risk of hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity and visual

disturbances; the generally recommended target trough range is 2-5

µg/ml (37,40,41).

Posaconazole, particularly the oral suspension, demonstrates

variable absorption in critically ill patients; TDM is therefore

recommended, with prophylaxis targets of >0.7 µg/ml and

treatment targets of >1.0-1.25 µg/ml (37,38,40).

Itraconazole is another azole for which TDM is advised, with

suggested trough levels >1 µg/ml to ensure efficacy (23,26). For

5-flucytosine, TDM is essential due to its narrow therapeutic

index, and the risk of bone marrow suppression and hepatotoxicity

at higher exposures. Target peak plasma concentrations are

typically 30-80 µg/ml, with the avoidance of sustained levels

>100 µg/ml (39,40). By candida.

In the ICU, where factors such as renal replacement

therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and drug-drug

interactions can alter antifungal disposition (23,40), TDM

provides a practical means of tailoring therapy to achieve optimal

exposure while minimizing toxicity. Its incorporation into routine

practice for selected agents represents a critical advance in

improving antifungal stewardship and clinical outcomes in

critically ill patients with IC (8,28,40).

8. Prevention and infection control

strategies

Prevention and control strategies for IC are

particularly important for reducing incidence and improving patient

outcomes in ICU settings. The routine screening and monitoring of

at-risk patients, including those with central venous catheters,

those on mechanical ventilation, or those treated with

broad-spectrum antibiotics in recent days, may aid in identifying

potential infections at an early stage. Accordingly, antifungal

prophylaxis is frequently considered in patients who are considered

high-risk, particularly when undergoing invasive surgery or whether

they are in an immunocompromised state. Although antifungals for

prophylaxis may be beneficial, the careful selection of patients

needs to be undertaken so as not to expose any others unnecessarily

and risk furthering resistance development. Strict infection

control measures, apart from pharmacological interventions, need to

be maintained. The standard precautions, such as hand washing, the

sterilization of medical products, and the use of standard sterile

techniques during invasive procedures, greatly limit the

transmission of Candida species. The timely removal of

central venous catheters when not medically necessary is another

preventive strategy to reduce the risk of catheter-related

bloodstream infection. Personalized antifungal stewardship programs

in hospitals will limit antifungal use to situations in which it is

truly required, while at the same time preventing the development

of resistance and aiding in the implementation of proper empirical

therapy on the basis of local resistance patterns. With these

surveillance, prophylactical and infection prevention strategies,

the incidence of developing IC in the ICU can be greatly reduced

(37-40).

9. Conclusion and future perspectives

Future aspects and research gaps in the management

of IC in ICU settings concern improving early diagnosis, optimizing

treatment strategies and resolving antifungal resistance; one of

the major areas of future studies could be the development of

rapid, non-culture-based, advanced molecular and serological assays

for the earlier detection of Candida infections, leading to

timelier and more targeted treatment. Furthermore, personalized

antifungal therapy could then be further improved, using genetic

and pharmacokinetic profiling, as patients in the ICU may also have

altered drug metabolism and clearance patterns. Research into novel

classes of antifungal agents and into combination therapies could

also pave the way, particularly in light of increasing resistance

to azoles and echinocandins. Furthermore, the identification of

biomarkers to predict resistance and outcomes in patients would

enable more directed treatment strategies. Research on prevention

strategies in high-risk ICU populations, particularly antifungal

prophylaxis, de-escalation protocols and the management of

indwelling devices, appears to be warranted. Furthermore,

understanding host-pathogen interactions and the role of the

microbiome in the development of IC may provide useful insights for

prevention and treatment. Research into these issues would

ultimately help to reduce the high morbidity and mortality rates

associated with IC and benefit the management of patients in ICUs

(36-37,40-42)

(https://dig.pharmacy.uic.edu/faqs/2024-2/nov-2024-faqs/what-information-is-available-to-guide-the-practice-of-therapeutic-drug-monitoring-for-itraconazole-posaconazole-voriconazole-and-isavuconazonium-sulfate/).

In conclusion, the management of IC in patients in

the ICU remains a complex challenge characterized by delayed

diagnoses, difficulties in risk stratification, antifungal

resistance and the requirement for pharmacokinetic adjustments. The

persistently high mortality rates among patients in ICUs, despite

advances in antifungal therapy and diagnostics, reflects the

non-specific nature of clinical presentation and the critical

baseline status of these patients. However, with the advent of

rapid diagnostic techniques, novel antifungal agents and improved

infection prevention strategies, there are promising avenues toward

improving patient outcomes. Optimal results will be achieved

through antifungal stewardship programs and multidisciplinary

collaboration. Notably, unlike prior reviews that have addressed IC

in broader adult populations (1-5,15,16),

the present review provides an ICU-specific synthesis that

integrates advances in diagnostics, antifungal pharmacology,

therapeutic drug monitoring, infection control and predictive risk

models. By tailoring insights to the critical care environment, the

present review aimed to bridge the gap between general antifungal

guidance and the practical realities faced in ICUs. Moving forward,

research on personalized treatment protocols, novel antifungal

therapies and prevention strategies will be of utmost importance to

overcoming current challenges and improving the survival and

quality of life of patients in ICUs.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author's contributions

All authors (WGE, AMA and AHAA) contributed to the

conception and design of the study, supervised the work, and

provided resources including access to institutional libraries,

clinical guidelines, and scientific databases (PubMed, Scopus, and

Embase), as well as reference management tools. They participated

in literature collection, screening, and processing, data analysis

and interpretation, and drafting and critical revision of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Soriano A, Honore PM, Puerta-Alcalde P,

Garcia-Vidal C, Pagotto A, Gonçalves-Bradley DC and Verweij PE:

Invasive candidiasis: Current clinical challenges and unmet needs

in adult populations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 78:1569–1585.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kullberg BJ and Arendrup MC: Invasive

candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 373:1445–1456. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Paramythiotou E, Frantzeskaki F, Flevari

A, Armaganidis A and Dimopoulos G: Invasive fungal infections in

the ICU: How to approach, how to treat. Molecules. 19:1085–1119.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gonzalez-Lara MF and Ostrosky-Zeichner L:

Invasive Candidiasis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 41:3–12.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Van de Veerdonk FL, Kullberg BJ and Netea

MG: Pathogenesis of invasive candidiasis. Curr Opin Crit Care.

16:453–459. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Thomas-Rüddel DO, Schlattmann P, Pletz M,

Kurzai O and Bloos F: Risk factors for invasive candida infection

in critically Ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Chest. 161:345–355. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Barantsevich N and Barantsevich E:

Diagnosis and treatment of invasive candidiasis. Antibiotics

(Basel). 11(718)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Oliva A, De Rosa FG, Mikulska M, Pea F,

Sanguinetti M, Tascini C and Venditti M: Invasive Candida

infection: Epidemiology, clinical and therapeutic aspects of an

evolving disease and the role of rezafungin. Expert Rev Anti Infect

Ther. 21:957–975. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Clancy CJ and Nguyen MH: Diagnosing

invasive candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 56:e01909–17.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ellepola AN and Morrison CJ: Laboratory

diagnosis of invasive candidiasis. J Microbiol. 43:65–84.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ylipalosaari P, Ala-Kokko TI, Koskenkari

J, Laurila JJ, Ämmälä S and Syrjälä H: Use and outcome of empiric

echinocandins in critically ill patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand.

65:944–951. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ben-Ami R: Treatment of invasive

candidiasis: A narrative review. J Fungi (Basel).

4(97)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

De Oliveira Santos GC, Vasconcelos CC,

Lopes AJO, de Sousa Cartágenes MDS, Filho AKDB, do Nascimento FRF,

Ramos RM, Pires ERRB, de Andrade MS, Rocha FMG and de Andrade

Monteiro C: Candida infections and therapeutic strategies:

Mechanisms of action for traditional and alternative agents. Front

Microbiol. 9(1351)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, Craven DE,

Flynn P, O'Grady NP, Raad II, Rijnders BJ, Sherertz RJ and Warren

DK: Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management

of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the

Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 49:1–45.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Peçanha-Pietrobom PM and Colombo AL: Mind

the gaps: Challenges in the clinical management of invasive

candidiasis in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis.

33:441–448. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Mehta Y: Challenges in the diagnosis and

treatment of invasive candidiasis in India. Int J Crit Care Emerg

Med. 10(165)2024.

|

|

17

|

Logan C, Martin-Loeches I and Bicanic T:

Invasive candidiasis in critical care: Challenges and future

directions. Intensive Care Med. 46:2001–2014. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hankovszky P, Társy D, Öveges N and Molnár

Z: Invasive candida infections in the ICU: Diagnosis and therapy. J

Crit Care Med (Targu Mures). 1:129–139. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Aldardeer NF, Albar H, Al-Attas M, Eldali

A, Qutub M, Hassanien A and Alraddadi B: Antifungal resistance in

patients with Candidaemia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect

Dis. 20(55)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mei-Sheng Riley M: Invasive fungal

infections among immunocompromised patients in critical care

settings: Infection prevention risk mitigation. Crit Care Nurs Clin

North Am. 33:395–405. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Delaloye J and Calandra T: Invasive

candidiasis as a cause of sepsis in the critically ill patient.

Virulence. 5:161–169. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Almirante B, Rodríguez D, Park BJ,

Cuenca-Estrella M, Planes AM, Almela M, Mensa J, Sanchez F, Ayats

J, Gimenez M, et al: Epidemiology and predictors of mortality in

cases of Candida bloodstream infection: Results from

population-based surveillance, barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003.

J Clin Microbiol. 43:1829–1835. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bellmann R and Smuszkiewicz P:

Pharmacokinetics of antifungal drugs: Practical implications for

optimized treatment of patients. Infection. 45:737–779.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Pfaller MA: Application of

Culture-independent rapid diagnostic tests in the management of

invasive candidiasis and cryptococcosis. J Fungi (Basel).

1:217–251. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bassetti M, Mikulska M and Viscoli C:

Bench-to-bedside review: Therapeutic management of invasive

candidiasis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care.

14(244)2010.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lepak AJ and Andes DR: Antifungal

pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect

Med. 5(a019653)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ademe M: Immunomodulation for the

treatment of fungal infections: Opportunities and challenges. Front

Cell Infect Microbiol. 10(469)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Alhamad H, Abu-Farha R, Albahar F, Jaber

D, Abu Assab M, Edaily SM and Donyai P: The impact of antifungal

stewardship on clinical and performance measures: A global

systematic review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 9(8)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy

CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Schuster MG, Vazquez

JA, Walsh TJ, et al: Clinical practice guideline for the management

of candidiasis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases society of

America. Clin Infect Dis. 62:e1–e50. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kumar NR, Balraj TA, Kempegowda SN and

Prashant A: Multidrug-resistant sepsis: A critical healthcare

challenge. Antibiotics (Basel). 13(46)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hurley JC: Trends in ICU mortality and

underlying risk over three decades among mechanically ventilated

patients. A group level analysis of cohorts from infection

prevention studies. Ann Intensive Care. 13(62)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Mayer LM, Strich JR, Kadri SS, Lionakis

MS, Evans NG, Prevots DR and Ricotta EE: Machine learning in

infectious disease for risk factor identification and hypothesis

generation: Proof of concept using invasive candidiasis. Open Forum

Infect. 9(ofac401)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Noppè E, Eloff JRP, Keane S and

Martin-Loeches I: A Narrative review of invasive candidiasis in the

intensive care unit. Ther Adv Pulm Crit Care Med.

19(29768675241304684)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Baltogianni M, Giapros V and Dermitzaki N:

Recent challenges in diagnosis and treatment of invasive

candidiasis in neonates. Children (Basel). 11(1207)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Pham D, Sivalingam V, Tang HM, Montgomery

JM, Chen S and Halliday CL: Molecular diagnostics for invasive

fungal diseases: Current and future approaches. J Fungi (Basel).

10(447)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Pappas PG, Lionakis MS, Arendrup MC,

Ostrosky-Zeichner L and Kullberg BJ: Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev

Dis Primers. 4(18026)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Yi WM, Schoeppler KE, Jaeger J, Mueller

SW, MacLaren R, Fish DN and Kiser TH: Voriconazole and posaconazole

therapeutic drug monitoring: A retrospective study. Ann Clin

Microbiol Antimicrob. 16(60)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

König C, Göpfert M, Kluge S and Wichmann

D: Posaconazole exposure in critically ill ICU patients: A need for

action. Infection. 51:1767–1772. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Sigera LSM and Denning DW: Flucytosine and

its clinical usage. Ther Adv Infect Dis.

10(20499361231161387)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Baracaldo-Santamaría D, Cala-Garcia JD,

Medina-Rincón GJ, Rojas-Rodriguez LC and Calderon-Ospina CA:

Therapeutic drug monitoring of antifungal agents in critically Ill

patients: Is there a need for dose optimisation? Antibiotics

(Basel). 11(645)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Jiang L and Lin Z: Voriconazole: A review

of adjustment programs guided by therapeutic drug monitoring. Front

Pharmacol. 15(1439586)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Sendid B, Poirot JL, Tabouret M, Bonnin A,

Caillot D, Camus D and Poulain D: Combined detection of mannanaemia

and antimannan antibodies as a strategy for the diagnosis of

systemic infection caused by pathogenic Candida species. J Med

Microbiol. 51:433–442. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Prella M, Bille J, Pugnale M, Duvoisin B,

Cavassini M, Calandra T and Marchetti O: Early diagnosis of

invasive candidiasis with mannan antigenemia and antimannan

antibodies. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 51:95–101. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|