Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in

Nigeria. The incidence of breast cancer increases with age, with

the majority of women diagnosed >40 years of age (1). Globally, ~25% of women with breast

cancer are pre-menopausal and peri-menopausal, while the remaining

are post-menopausal. A great burden of pre-menopausal women with

breast cancer are found in low-income and middle-income countries

with 55.2% of total breast cancer cases in countries with a low

human development index occurring in pre-menopausal women (2). In Nigeria, the proportion of breast

cancer among pre-menopausal women is close to 60% (3). This group therefore has a higher

proportion of breast cancer cases among individuals of African

ancestry, more than the proportion among Caucasians, where young

women of reproductive age account for the minority of women that

are diagnosed with breast cancer. There is therefore a racial

difference in terms of the incidence of young women with breast

cancer. It has been reported that prior to the age of 35 years, the

percentage of African Americans with breast cancer is more than

twice that of the Caucasians (4).

Although the incidence of breast cancer has

progressively increased recently, there has also been a

simultaneous improvement in the survival rates. This is partly due

to early detection and adjuvant chemotherapy (5). Despite improved survival rates however,

there are certain issues associated with survivorship, such as

fertility concerns, late side-effects of treatment, as well as

psychosocial issues. Pre-menopausal women are those with a regular

menstrual period. Pre-menopausal women pass through different

levels of monthly cyclic changes, which are characterized by

varying hormonal levels that signal each phase of the menstrual

cycle.

Hormonal levels in pre-menopausal women for estrogen

and progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), anti-Müllerian hormone

(AMH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) fluctuate during the

menstrual cycle, following the pattern presented in Table I (6).

| Table IHormonal changes throughout the

menstrual cycle. |

Table I

Hormonal changes throughout the

menstrual cycle.

| Phase of menstrual

cycle | Estrogen (pg/ml) | Progesterone

(ng/ml) | LH (iu/l) | FSH (iu/l) | AMH (ng/ml) |

|---|

| Phase I (menstrual

phase- days 1-5) | 160.00±66.24 | 0.60±0.40 | 7±6.00 | 1.00-9.00 | 0.29-12.70 |

| Phase II (follicular

phase- days 10-13) | 778.00±255.43 | 0.64±0.31 | 20.00±8.00 | 6.00-26.00 | 2.41

(0.15-14.50) |

| Phase Ill (luteal

phase-days 20-23) | 395.00±134.57 | 14.00±5.44 | 7.00±4.00 | 1.00-9.00 | 2.07 (0.08-8.58) |

The peri-menopausal state is regarded as the time

during which a women has irregular menstruation cycles;

menstruation can cease for ≥3 months and then resumes. A woman is

said to be menopausal after having attained the complete cessation

of menstrual periods for at least 12 months (7,8).

Young women with breast cancer are considered to be

high-risk subjects as they are likely to have estrogen

receptor-negative/high-grade tumors; therefore, chemotherapy is

commonly part of their treatment modalities. The majority of

chemotherapeutic regimens for breast cancer have deleterious

effects on the ovaries, thereby affecting fertility. These women

may also attain a state of premature amenorrhea, which can be

temporary or permanent. Women who resume regular menstrual cycles

following the completion of chemotherapy may be less fertile

compared with those who have not received any chemotherapy. They

may also attain menopause earlier than expected (premature

menopause) (9-11).

The rate of amenorrhea varies from 21 to 71% in young women and

49-100% in those >40 years of age treated with chemotherapy

(12).

Fertility concerns are major considerations in women

of childbearing age who are placed on chemotherapy, particularly

among those who still desire to have children. On this account,

concerns for fertility may render treatment decision-making more

complex for young women with breast cancer (13), particularly as young women with

breast cancer experience greater psychosocial distress and anxiety

about infertility compared with their older counterparts.

Primary ovarian insufficiency and premature

menopause are regarded as potential compromises on reproductive

potential. Sometimes a woman may menstruate, but may still suffer

from partial ovarian injury, which may result in subfertility

(14). Due to the increasing

incidence of breast cancer among pre-menopausal women, some

patients are concerned about how they will successfully conceive

following the completion of treatment, which includes the

administration of chemotherapy. Clinicians, reproductive medicine

specialists and gynecologists should be conversant with these

concerns of the patients.

Research has demonstrated that the concentrations of

female sex hormones, such as AMH, inhibin-B, inhibin-A, FSH, LH and

estradiol (E2) exhibit various changes following the

administration of chemotherapy (15-18).

To date, reports on the effects of chemotherapy on female sex

hormones (which are a reflection of ovarian function) among

indigenous populations of African origin are limited, hence the

need for the present study. The aim of the present study was to

determine the effects of chemotherapy on ovarian function/reserve

among the study population which included a high proportion of

pre-menopausal women, most of whom desired child birth following

chemotherapy. The levels of three hormones, namely FSH,

E2 and AMH were measured. AMH is relative stable,

without it being influenced by the menstrual cycle; hence

researchers have selected AMH as a reliable biomarker to assess

ovarian reserve during and after chemotherapy (19) (Table

I).

Patients and methods

The present study was a prospective study conducted

at the Department of Radiation and Clinical Oncology of the Lagos

University Teaching Hospital, Idi-araba, Lagos, Nigeria, between

October, 2020 to November, 2023. Young women within the

reproductive age group (18-42 years) and with a histologically

confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer were counseled appropriately

on the study and their written consent for participation in the

study was obtained. Participants were counselled on fertility

preservation and asked for their preferences.

Blood samples were collected from eligible

pre-menopausal women after obtaining consent, that were newly

diagnosed with breast cancer and who were planning to receive

chemotherapy as part of their oncological treatment. The samples

were collected prior to treatment with chemotherapy (3-5 days from

the last menstrual period), and then at 3 and 6 months following

the completion of chemotherapy. Patients were also followed-up for

12 months to observe menstrual flow patterns. The patients used a

menstrual diary to track their date and duration of flow. However,

the flow quantity was not measured. The number of sanitary pads

used during each menstrual period was recorded and used to estimate

the quantity of menstrual flow, while the duration of flow was also

recorded. All the patients recruited for the study were on a 3-week

chemotherapeutic regimen. First-line chemotherapy was administered

every 3 weeks amounting to four courses within the first 12 weeks.

This consisted of an anthracycline (doxorubicin 60 m2 or

epirubicin 75 mg/m2) + cyclophosphamide at 600

mg/m2 with or without a 5-fluorouracil regimen at 600

mg/m2 (AC/CAF) or docetaxel at 75 m/m2 +

doxorubicin at 60 mg/m2 + cyclophosphamide at 600

mg/m2 (TAC) regimen. In the second 12 weeks,

participants received four courses administered every 3 weeks of

either a taxane (docetaxel at 75 mg/m2 or paclitaxel at

175 mg/m2) + capecitabine at 2,000 mg twice daily or a

platinum compound (cisplatin at 50 mg/m2 or carboplatin

5 AUC) + a taxane regimen (PT) as a second regimen based on

institutional guidelines. The blood samples obtained from the

participants were stored and analyzed at the Human Reproductive and

Endocrinology Research Laboratory, Department Obstetrics and

Gynecology, College of Medicine, University of Lagos/Lagos

University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Idi-Araba, Lagos, Nigeria.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from institutional

Ethics Committee at Lagos University Teaching Hospital Health

Research Ethics Committee with the assigned no.

ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/2736. Written and signed informed consent was

obtained from the participants prior to enrolment in the study.

The participants included in the study were females,

aged 18-42 years, who had histologically confirmed breast cancer at

stages 1-3, who were chemotherapy naïve and with an ECOG

performance status of 0-1. The exclusion criteria were pregnant

patients, those who had been previously treated with chemotherapy,

those who had undergone a hysterectomy, as well as those with an

irregular menstrual cycle, as well as post-menopausal women or with

last menses >3 months prior.

Sample collection and laboratory

analyses

The specimens were blood samples collected by

venipuncture into lithium heparin bottles. Of note, ~5 ml blood

samples were obtained from each participant with minimal pain at

the site of venipuncture. The blood samples collected were

centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C to obtain plasma; these

samples were stored in a freezer at -80˚C and later analyzed.

In total, three different sets of blood samples were

collected for the study: Prior to the commencement of chemotherapy,

at 3 months following the completion of chemotherapy and at 6

months following chemotherapy. The chemotherapy was administered at

3 weekly intervals. The plasma samples were stored at -80˚C and

analyzed in the laboratory for AMH, E2 and FSH. A direct

immunoenzymatic colorimetric method was used for the quantitative

determination of AMH, E2 and FSH concentrations in

plasma using ELISA kits (cat. nos. SEK-0003, SEK-0008 and SEK-0010,

Rapid Labs) as previously described (15).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 23

software (IBM Corp.). The descriptive characteristics of the study

participants were summarized using tables and charts. Numerical

data, including the levels of hormonal parameters among the study

participants are expressed as the mean (SD) at pre-chemotherapy, at

3 months post-chemotherapy and at 6 months post-chemotherapy. The

effects of the various chemotherapy combinations on hormone levels

were analyzed using paired t-tests at two specific intervals:

Pre-chemotherapy vs. 3 months post-chemotherapy, and 3 vs. 6 months

post-chemotherapy. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was used to compare the hormone levels (AMH, E2 and FSH)

measured in the same study participants at three different time

intervals [pre-chemotherapy (baseline), at 3 months

post-chemotherapy and at 6 months post-chemotherapy]. Where

significant differences were observed, pairwise comparisons between

time points were conducted using Bonferroni post hoc tests to

control for multiple comparisons. A Fisher's exact test was

conducted to assess the association between age group and

menstruation patterns at 6 months following chemotherapy. A value

of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

A total of 96 pre-menopausal women diagnosed with

breast cancer were recruited for the present study. However, 14

dropped out of the study and were exempted from the analysis. The

reasons for dropping out included seeking alternative treatments,

such as spiritual and herbal healing, pregnancy, financial

constraints and a change of residence. Parameters from 82

participants were analyzed. The mean age of all the participants in

the study was 36.6 years (range, 32-41 years). The majority (71%)

had at least 1 child, while 29% were nullipara. Of note, ~51% of

the patients still desired to have more children. The age of the

participants ranged from 32-41 years, with a mean age at diagnosis

of breast cancer of 35.5 years (Table

II). As regards the preference for fertility preservation, 63

(77%) were willing to use methods to preserve fertility, while 19

(23%) declined. Preferred fertility methods were as follows: The

use of drugs 38 (46%); ovum banking 13 (16%) and adoption 25 (31%),

while 6 (7%) patients did not choose any specific method of

fertility preservation. Unfortunately, none of those who preferred

fertility preservation could afford goserelin, which is the least

costly form of fertility preservation currently available in

Nigeria.

| Table IIBiodata of the study participants. |

Table II

Biodata of the study participants.

| Variable (n=82) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|

| Age at presentation

(years) | | |

|

≤30 | 10 | 12.2 |

|

31-40 | 56 | 68.3 |

|

41-50 | 16 | 19.5 |

| Mean age,

36.6±4.6 | | |

| Occupation | | |

|

Skilled

professional | 9 | 11.0 |

|

Minimally

skilleda | 58 | 70.7 |

|

Not in

active employmentb | 15 | 18.3 |

| Education

level | | |

|

None | 6 | 7.3 |

|

Primary | 2 | 2.4 |

|

Secondary | 41 | 50.0 |

|

Tertiary | 33 | 40.2 |

| Marital status | | |

|

Married | 55 | 67.1 |

|

Not

marriedc | 27 | 32.9 |

|

Partner's

occupation (n=55) | | |

|

Skilled

professional | 3 | 5.5 |

|

Minimally

skilleda | 50 | 90.9 |

|

Not in

active employmentb | 2 | 3.6 |

| Parity | | |

|

0 | 24 | 29.3 |

|

1 | 10 | 12.2 |

|

2 | 18 | 22.0 |

|

3 | 13 | 15.9 |

|

≥4 | 17 | 20.6 |

| Desire for more

children | | |

|

Yes | 42 | 51.2 |

|

No | 40 | 48.8 |

Most of the participants had AJCC anatomic stage III

disease. Other clinical parameters of participants are presented in

Table III. The first line of

chemotherapy administered within the first 12 weeks consisted of

anthracycline + cyclophosphamide/5-fluorouracil regimen (AC/CAF)

(81 participants), or the taxane + anthracycline + cyclophosphamide

(TAC) regimen (only 1 participant). In the second 12 weeks, 61

participants continued with AC/CAF, no participant continued with

the TAC regimen, while 13 participants had their chemotherapy

changed to taxane + xeloda, and 8 patients received the platinum +

taxane regimen (PT) based on response and toxicity evaluations

following institutional guidelines (Table IV). The plasma levels of the

hormones of interest, namely AMH, E2 and FSH exhibited

variations during the study period, as demonstrated in Table V.

| Table IIIClinical history of the study

participants. |

Table III

Clinical history of the study

participants.

| Variable

(n=82) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|

| Disease stage | | |

|

I | 4 | 4.9 |

|

II | 7 | 8.5 |

|

III | 71 | 86.6 |

| ECOG score at

presentation | | |

|

0 | 47 | 57.3 |

|

1 | 35 | 42.7 |

| Nutritional status

(BMI) (kg/m2) | | |

|

Normal | 43 | 52.4 |

|

Overweight

and obese | 39 | 47.6 |

| Primary site of

disease | | |

|

Left | 46 | 58.5 |

|

Right | 36 | 41.5 |

| Presence of

comorbidities | | |

|

Yes | 12 | 13.4 |

|

No | 70 | 86.6 |

| Type of

comorbidities (n=12) | | |

|

Hypertension | 4 | 33.3 |

|

Peptic ulcer

disease | 4 | 33.3 |

|

HIV/AIDS | 4 | 33.3 |

| History of breast

surgery | | |

|

Yes | 29 | 35.4 |

|

No | 53 | 64.6 |

| Surgery type

(n=29) | | |

|

Lumpectomy | 9 | 31.0 |

|

Mastectomy | 20 | 69.0 |

| Table IVChemotherapeutic regimens among the

study participants. |

Table IV

Chemotherapeutic regimens among the

study participants.

| Regimen (n=82) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|

| Phase I | | |

|

Anthracycline

+ cyclophosphamide regimen (AC/CAF) | 81 | 98.8 |

|

Taxane +

anthracycline + cyclophosphamide (TAC) | 1 | 1.2 |

| Phase II | | |

|

Anthracycline

+ Cyclophosphamide regimen (AC/CAF) | 61 | 74.4 |

|

Taxane +

xeloda (TX) | 13 | 15.8 |

|

Platinum +

taxane (PT) | 8 | 9.8 |

| Table VLevels of hormonal parameters among

the study participants. |

Table V

Levels of hormonal parameters among

the study participants.

| Variable

(n=82) |

Pre-chemotherapy | Post-chemotherapy

(3 months) | Post-chemotherapy

(6 months) |

|---|

| AMH (ng/ml) | | | |

|

<1 | 46 (56.1) | 69 (84.1) | 80 (97.6) |

|

1-2 | 16 (19.5) | 6 (7.1) | 2 (2.4) |

|

>2 | 20 (24.4) | 7 (8.5) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Mean

(SD) | 1.66 (0.84) | 0.71 (0.60) | 0.14 (0.16) |

| E2 (IU/ml) | | | |

|

<50 | 57 (69.5) | 61 (74.4) | 62 (75.6) |

|

50-100 | 20 (24.4) | 18 (22.0) | 19 (23.2) |

|

>100 | 5 (6.1) | 5 (6.1) | 1 (1.2) |

|

Mean

(SD) | 57.56 (5.32) | 43.15 (4.66) | 33.82 (3.37) |

| FSH (pg/ml) | | | |

|

<50 | 61 (74.4) | 55 (67.1) | 43 (52.4) |

|

50-100 | 11 (13.4) | 14 (17.1) | 21 (25.6) |

|

>100 | 10 (12.2) | 13 (15.9) | 18 (22.0) |

|

Mean

(SD) | 14.16 (2.39) | 33.70 (4.18) | 47.13 (5.29) |

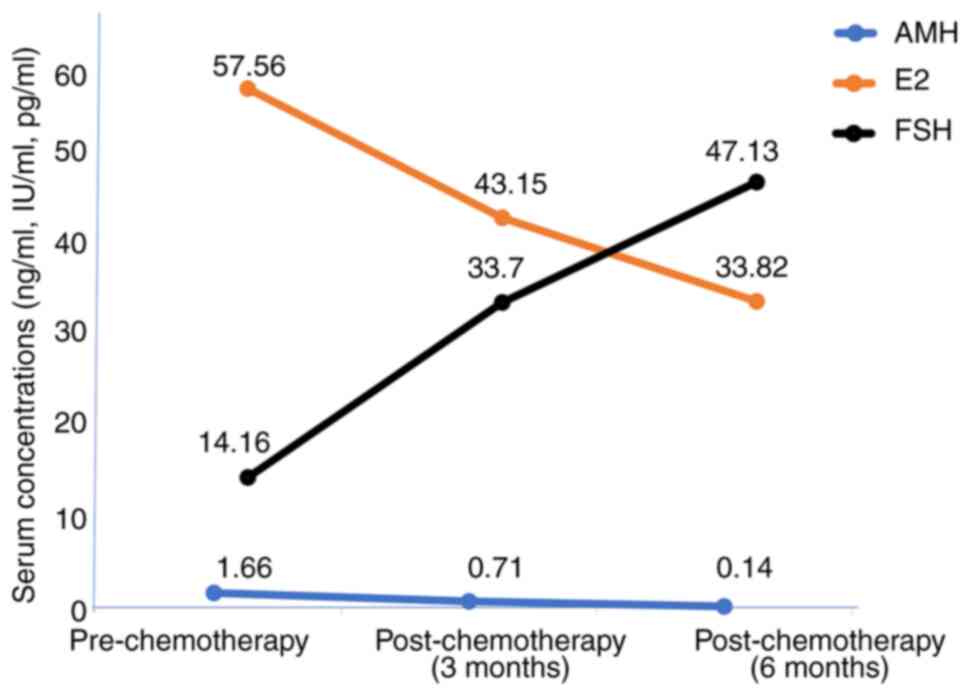

The trend of the levels of the hormones during the

study period is presented in Fig. 1.

To assess changes across the three timepoints pre-chemotherapy

(baseline), at 3 months post-chemotherapy and at 6 months

post-chemotherapy, a repeated measures ANOVA was performed. The

analysis demonstrated a significant time effect for AMH (F=2.56,

P<0.001), E2 (F=0.997, P=0.003) and FSH (F=3.227,

P<0.001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni

adjustment revealed a significant decline in AMH levels between

baseline and 3 months with a mean difference of 0.938 ng/ml

(P<0.001) and between baseline and 6 months with a mean

difference of 1.511 ng/ml (P=0.004), as well as between 3 and

6-months post-chemotherapy with a mean difference of 0.573 ng/ml

(P=0.025). By contrast, the E2 levels demonstrated a

significant decrease from baseline to 3 months with a mean

difference of 0.222 IU/ml (P 0.013) and from baseline to 6 months

with a mean difference of 0.300 IU/ml (P=0.004), and with a further

reduction observed between 3 and 6 months, although not

statistically significant [mean difference of 0.121 IU/ml (P=0.177]

). FSH levels on the other hand, exhibited a significant increase

from baseline to 3 months with a mean difference of -19.522 pg/ml

(P<0.001), and from baseline to 6 months with mean difference of

-34.202 pg/ml (P=0.004); however, no further significant increase

was evident between 3- and 6-months post-chemotherapy with mean

difference of -14.680 pg/ml (P=0.076).

The effects of the two chemotherapy combinations on

hormone levels were analyzed using ANOVA and paired t-tests. The

analysis on the AC/CAF chemotherapeutic regimen using repeated

measures ANOVA (pre-chemotherapy vs. 3 months post-chemotherapy,

and 3 vs. 6 months post-chemotherapy) yielded the following

results: AMH (F=1.688, P=0.064), E2 (F=2.111, P=0.073)

and FSH (F=1.711, P=0.172). With the chemotherapeutic regimens of

taxane + xeloda and platinum compounds + taxane, a paired t-test

analysis at two specific intervals of 3 months post-chemotherapy

vs. 6 months-post chemotherapy yielded P-values >0.05 (Table VI, Table VII and Table VIII). The mean values were

recorded, as well as the mean differences in percentages as

presented on the tables. Across all three hormones, there were no

significant differences in hormonal changes attributable to the

chemotherapy combinations (all P-values >0.05). These data

indicated that the type of chemotherapeutic regimen did not

significantly influence ovarian hormone response over time.

| Table VIEffect of chemotherapy on AMH levels

among the study participants. |

Table VI

Effect of chemotherapy on AMH levels

among the study participants.

| | 1st to 3rd month

(mean values) | 3rd to 6th month

(mean values) |

|---|

| Drugs | No. of

patients |

Pre-chemotherapy | Post-chemotherapy

(3 months) | Mean difference

(%) | No. of

patients | Post-chemotherapy

(3 months) | Post-chemotherapy

(6 months) | Mean difference

(%) |

|---|

| AC/CAF | 81 | 1.67 (ng/ml) | 0.72 (ng/ml) | 0.95 (56.9) | 61 | 0.72 ng/ml | 0.16 ng/ml | 0.56 (77.8) |

| | | | | (F=1.688,

P=0.064) |

| TAC | 1 | 0.82 (ng/ml) | 0.11 (ng/ml) | 0.71 (86.6) | | | | |

| | | P=0.132 | | |

| Taxane +

xeloda | | | | | 13 | 0.31 (ng/ml) | 0.10 (ng/ml) | 0.21 (67.7) |

| | | | | P=0.224 |

| PT | | | | | 8 | 0.52 (ng/ml) | 0.09 (ng/ml) | 0.43 (82.7) |

| | | | | P=0.816 |

| Table VIIEffect of chemotherapy on

E2 levels among the study participants. |

Table VII

Effect of chemotherapy on

E2 levels among the study participants.

| | 1st to 3rd month

(mean values) | 3rd to 6th month

(mean values) |

|---|

| Drugs | No. of

patients |

Pre-chemotherapy | Post-chemotherapy

(3 months) | Mean difference

(%) | No. of

patients | Post-chemotherapy

(3 months) | Post-chemotherapy

(6 months) | Mean difference

(%) |

|---|

| AC/CAF | 81 | 53.08 (IU/ml) | 38.70 (IU/ml) | 14.38 (27.1) | 61 | 38.70 (IU/ml) | 36.15 (IU/ml) | 2.55 (6.58) |

| | | | | (F=2.111,

P=0.073) |

| TAC | 1 | 57.56 (IU/ml) | 43.15 (IU/ml) | 14.41 (25.0) | | 43.15 (IU/ml) | 33.82 (IU/ml) | 9.35 (21.7) |

| | | P=0.418 | | P=0.079 |

| Taxane +

xeloda | | | | | 13 | 28.81 (IU/ml) | 25.09 (IU/ml) | 3.72 (12.9) |

| | | | | P=0.827 |

| PT | | | | | 8 | 32.90 (IU/ml) | 21.09 (IU/ml) | 11.81 (35.9) |

| | | | | P=0.308 |

| Table VIIIEffect of chemotherapy on FSH levels

among the study participants. |

Table VIII

Effect of chemotherapy on FSH levels

among the study participants.

| | 1st to 3rd month

(mean values) | 3rd to 6th month

(mean values) |

|---|

| Drugs | No. of

patients |

Pre-chemotherapy | Post-chemotherapy

(3 months) | Mean difference

(%) | No. of

patients | Post-chemotherapy

(3 months) | Post-chemotherapy

(6 months) | Mean difference

(%) |

|---|

| AC/CAF | 81 | 14.22 (pg/ml) | 34.03 (pg/ml) | 19.81 (139.3) | 61 | 34.03 (pg/ml) | 42.77 (pg/ml) | 8.74 (25.68) |

| | | | | (F=1.711,

P=0.172) |

| TAC | 1 | 8.87 (pg/ml) | 7.25 (pg/ml) | -1.62 (-18.3) | | | | |

| | | P=0.938 | | |

| Taxane +

xeloda | | | | | 13 | 41.46 (pg/ml) | 49.51 (pg/ml) | 8.05 (19.4) |

| | | | | P=0.177 |

| PT | | | | | 8 | 46.12 (pg/ml) | 83.21 (pg/ml) | 37.09 (80.4) |

| | | | | P=0.853 |

The effects of chemotherapy on the menstrual cycle

of the participants differed slightly according to age. A Fisher's

exact test was conducted to assess the association between age

group and menstruation patterns at 6 months following chemotherapy.

The association was not statistically significant (P=0.146)

(Table IX). Some participants

experienced changes in their menstrual patterns at 6 months

following chemotherapy. At the 12-month follow-up, the menstrual

pattern was as follows: Regular, 38 (46%); irregular, 19 (23%);

while 25 (31%) exhibited the complete cessation of

menstruation.

| Table IXAssociation between age and

menstruation patterns (at 6 months following chemotherapy). |

Table IX

Association between age and

menstruation patterns (at 6 months following chemotherapy).

| | Menstruation

pattern |

|---|

| | Regular (%) | Irregular (%) | Absent (%) | Total | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | | | | | 0.146 |

|

≤30 | 6(7) | 4(5) | 0 (0.0) | 10 | |

|

31-40 | 37(45) | 11(14) | 8(10) | 56 | |

|

41-50 | 6(7) | 6(7) | 4(5) | 16 | |

Discussion

The diagnosis of breast cancer is increasing and is

likely to occur prior to the completion of creating a family in

numerous females. The use of chemotherapy is an integral part of

the treatment of breast cancer among most pre-menopausal women.

However, its administration is not without significant reproductive

side-effects in those who are still within their reproductive age

group. Understanding the impact of chemotherapy on future fertility

is of utmost importance. The present study demonstrated that

chemotherapy significantly affected key hormones that regulate the

reproductive cycle of pre-menopausal women being treated with

chemotherapy for breast cancer. In the present study, three

hormones (AMH, E2 and FSH) were evaluated for the

effects of chemotherapy on the plasma concentrations of these

hormones. The mean values of both AMH and E2

progressively decreased within the 6 months of their evaluation,

while the mean value of FSH increased (Table V). These derangements suggest that

the fertility of these pre-menopausal women had been negatively

affected. These findings are in agreement with those of previous

studies reporting a significant decrease in E2 and AMH

levels following chemotherapy for breast cancer (17,20). On

the other hand, the plasma level of FSH increased following

chemotherapy. This is consistent with the findings of previous

reports demonstrating reduced ovarian function (21,22).

These findings thus support the need for ovarian protection during

chemotherapy. There are studies demonstrating that the

administration of hormonal therapy (aromatase inhibitor/tamoxifen),

particularly in hormone receptor-positive women, or

gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist e.g., goserelin,

administered during chemotherapy exerts some degree of protection

on the ovaries (23,24).

The present study also indicated changes in the

monthly menstrual pattern of some of the participants at 6 months

following treatment. Although the quantity of monthly menstrual

flow was not measured, the quantity of flow was estimated with fair

accuracy, particularly by younger patients, since individuals are

already conversant with their menstrual flow pattern (25). In addition, using the records of the

number of sanitary pads used during each menstrual period and the

duration of flow as recorded by the participants, the authors deem

that the quantity of monthly flow was fairly estimated. Almost 15%

of the participants became amenorrhoeic following chemotherapy,

while 26% developed irregular menstrual patterns (Table IX). This is less than the previously

reported proportion of 21 to 71% in young women treated with

chemotherapy, although these data are from other populations

(26). The data may also reflect the

higher number of young patients in the present study. It is also

worthwhile to note that those who were ≤30 years of age did not

experience the absence of menstruation even though the number was

low. A previous study in Nigeria indicated that ~33% of the

participants experienced the cessation of the menstrual cycle

(27). In that study, participants

with various malignancies with different chemotherapeutic regimens

were included, whereas the present study only included patients

with breast cancer patients with a fairly uniform chemotherapeutic

regimens. However, this result is indicative of the higher ovarian

reserve in younger patients than older ones following

chemotherapy.

In the present study, the effects of the different

chemotherapeutic regimens on the expression of the FSH,

E2 and AMH hormone levels during the study period were

also assessed, with no significant differences observed (Table VI, Table VII and Table VIII). The chemotherapeutic

regimens used were standard combination regimens used for breast

cancer administered every 3 weeks sequentially. All patients

received either of the two combinations (anthracyclines +

cyclophosphamide) first and then shifted to the second combination

(taxanes and platinum compounds) or vice versa. At the end, they

were exposed to similar chemotherapeutic agents based on their body

surface areas. Thus, the authors deem that the results reflected

the cumulative effects of chemotherapy. The analyses did not reveal

significant effects of the three regimens on the hormonal levels.

This demonstrates that in the present study, the effects of

chemotherapy on ovarian function were not dependent on the breast

cancer chemotherapeutic regimen administered. This is similar to

the previous study by Goldfarb et al (28) who reported no difference in the

decline of AMH levels among pre-menopausal women receiving

cyclophosphamide methotrexate and the 5 fluorouracil (CMF)

combination; adriamycin, cyclophosphamide and taxane (AC-T)

combination, and then taxane and herceptin (TH) for breast cancer.

In addition, Goldfarb et al (28) also observed that age was an important

predictor of AMH levels as the older age of the participants was

associated with lower AMH values. The present study also yielded

similar findings.

Almost one third of the participants had

hormone-positive breast cancer and were treated with tamoxifen.

This may affect the hormonal levels; however, a previous study

reported no significant difference in the levels of E2

post-chemotherapy and post-hormonal therapy as the patients in each

group had decreased E2 levels following treatment

(17).

A notable number of the participants (77%) preferred

fertility preservation; however, they could not afford goserelin,

which is the only form of fertility preservation currently

available in Nigeria. Some patients had comorbidities, namely

hypertension, diabetes and HIV infection, and all were well

controlled. A previous study demonstrated that HIV infection does

not have significant effect on estrogen levels in pre-menopausal

HIV-positive women with an unsuppressed CD4 count (29). The observed changes may mainly be due

to the chemotherapy received by the participants. It was also

observed that at 6 months post-chemotherapy, none of the hormonal

levels indicated recovery from the effects of chemotherapy,

indicating that the effects last far beyond 6 months

post-treatment. This was supported by the observation that at 12

months, those with regular menses were reduced from 49 (58%) to 38

(46%), while 25 (31%) of the participants experienced cessation of

menstrual flow compared with 12 (16%) at 6 months. A longer period

of follow-up is required to identify the time and pattern of

recovery for those whose ovarian function recovered from the

effects of chemotherapy. From the findings of the present study, it

is highly recommended that fertility preservation services, such as

the use of oocyte/embryo cryopreservation, ovarian suppression and

GnRH agonists with counselling be provided to patients scheduled to

undergo cancer chemotherapy if they still desire to have children

folowing treatment.

Limitations of the study

The lack of data comparing study completers and

non-completers is a limitation to the present study. This could not

allow the assessment of the characteristics of those who completed

the study against those who did not. Nevertheless, the results

obtained still provide useful information about the population

under study. However, multivariate analysis adjusting for potential

confounders (e.g., age, parity and baseline AMH) was not performed

on the study data. A simple analysis was used, since this was

within a specific age group of <42 years, and we looked for

characteristics of 30 years and >30 years based on previous

reports on the literature (30,31).

Furthermore, since individual hormonal levels were measured at

baseline and then serially, each patient stood as a self-control.

Additionally, hormone level variability exists across menstrual

phases, and this may have confounded the E2 and FSH

results. The patients were on 3 weekly chemotherapy treatments,

with some participants residing at a distance from the hospital.

Measuring the hormone levels based on the menstrual cycle phase

would have necessitated more visits to the clinic, which would have

been too stressful for the patients with breast cancer receiving

chemotherapy. The exact volume of menstrual flow per cycle could

not be measured for the purpose of determining reduction in

menstrual flow following chemotherapy. However, using the number of

sanitary pads used during each menstrual cycle and recording the

duration in a diary was deemed to have provided a fair estimate of

the quantity of menstrual blood loss by an individual during the

study.

The present study was conducted in southwest

Nigeria, which represents a fraction of the Nigerian population.

The results cannot therefore be generalized to the entire

population of Nigeria. Nevertheless, the results provide useful

information that can be used to guide the design of larger studies

that can give information about the Nigerian population.

In conclusion, 82 Nigerian participants with a

pre-menopausal onset of breast cancer treated with chemotherapy

were analyzed in the present study. The findings revealed that

chemotherapy led to a significant reduction in ovarian function, as

reflected by the negative changes in the plasma concentrations of

E2, FSH and AMH. The effects were more pronounced in

participants >30 years of age, as some developed an irregular or

cessation of menstrual flow. The different chemotherapeutic

regimens for breast cancer did not significantly affect ovarian

function. The hormonal levels did not exhibit a recovery at 6

months post-chemotherapy, while the induced reduction in menstrual

patterns persisted for 12 months following chemotherapy. These

findings suggest that the effects of chemotherapy last >6

months. Clinicians should thus be aware of the deleterious effects

of chemotherapy on ovarian function and counsel such patients who

desire childbearing appropriately on fertility issues to ensure

good survivorship.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Ms.

Oluwawemimo Akinlabi of the Department of Radiation Oncology,

College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria for her

assistance with data analysis.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

OP and MH conceptualized the study and provided

resources and funding for the project. AA, OAl and GO took part in

the investigations and data acquisition. UO and OAd contributed to

the study methodology and formal analysis. AN was involved in the

conception and design of the study, and also supervised the study

and was involved in the drafting of the manuscript. OP and AN

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors edited

the manuscript, and read and approved the submission and final

version of the manuscript. All authors have access to the study

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Lagos

University Teaching Hospital Health Research Ethics Committee

(LUTHHREC) with the approval no. ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/2736. Written

and signed informed consent to participate in the study was

obtained from all participants prior to enrolment into the

study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Azubuike SO, Muirhead C, Hayes L and

McNally R: Rising global burden of breast cancer: The case of

sub-Saharan Africa (with emphasis on Nigeria) and implications for

regional development: A review. World J Surg Oncol.

16(63)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, Sung H,

McCormack V and Fidler-Benaoudia MM: Global burden and trends in

premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: A population-based

study. Lancet Glob Health. 8:e1027–e1037. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ali-Gombe M, Mustaph MI, Folasire A,

Ntekim A and Campbell OB: Pattern of survival of breast cancer

patients in a tertiary hospital in south west Nigeria.

Ecancermedicalscience. 15(1192)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hung MC, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH and White A:

Racial/ethnicity disparities in invasive breast cancer among

younger and older women: An analysis using multiple measures of

population health. Cancer Epidemiol. 45:112–118. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

El Saghir NS, Khalil LE, El Dick J, Atwani

RW, Safi N, Charafeddine M, Al-Masri A, El Saghir BN, Chaccour M,

Tfayli A, et al: Improved survival of young patients with breast

cancer 40 years and younger at diagnosis. JCO Glob Oncol.

9(e2200354)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Reed BG and Carr BR: The normal menstrual

cycle and the control of ovulation. In: Feingold KR, ASF AB (eds)

et al. Endotext. 2nd edition. South Dartmouth (MA):

MDText.com, Inc.; 2018.

|

|

7

|

Delamater L and Santoro N: Management of

the perimenopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 61:419–432. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Davis SR, Pinkerton J, Santoro N and

Simoncini T: Menopause-Biology, consequences, supportive care, and

therapeutic options. Cell. 186:4038–4058. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Partridge AH, Gelber S, Peppercorn J,

Sampson E, Knudsen K, Laufer M, Rosenberg R, Przypyszny M, Rein A

and Winer EP: Web-based survey of fertility issues in young women

with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 22:4174–4183. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hong YH, Park C, Paik H, Lee KH, Lee JR,

Han W, Park S, Chung S and Kim HJ: Fertility preservation in young

women with breast cancer: A review. J Breast Cancer.

26(221)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mannion S, Higgins A, Larson N, Stewart

EA, Khan Z, Shenoy C, Nichols HB, Su HI, Partridge AH, Loprinzi CL,

et al: Prevalence and impact of fertility concerns in young women

with breast cancer. Sci Rep. 14(4418)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Turnbull AK, Patel S, Martinez-Perez C,

Rigg A and Oikonomidou O: Risk of chemotherapy-related amenorrhoea

(CRA) in premenopausal women undergoing chemotherapy for early

stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 186:237–245.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sun M, Liu C, Zhang P, Song Y, Bian Y, Ke

S, Lu Y and Lu Q: Perspectives and needs for fertility preservation

decision-making in childbearing-age patients with breast cancer: A

qualitative study. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 11(100548)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, Oktay

KH, McCulloch CE, Ai WZ, Chien AJ, Melisko ME, Cedars MI and Rosen

MP: Acute ovarian failure underestimates age-specific reproductive

impairment for young women undergoing chemotherapy for cancer.

Cancer. 118:1933–1939. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lambert-Messerlian G, Plante B, Eklund EE,

Raker C and Moore RG: Levels of antimüllerian hormone in serum

during the normal menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 105:208–213.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Furlanetto J, Marmé F, Seiler S, Thode C,

Untch M, Schmatloch S, Schneeweiss A, Bassy M, Fasching PA, Strik

D, et al: Chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure in young women with

early breast cancer: Prospective analysis of four randomised

neoadjuvant/adjuvant breast cancer trials. Eur J Cancer.

152:193–203. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Soewoto W and Agustriani N: Estradiol

levels and chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: A prospective

clinical study. World J Oncol. 14:60–66. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bala J, Seth S, Dhankhar R and Ghalaut VS:

Chemotherapy: Impact on Anti-Müllerian Hormone Levels in Breast

Carcinoma. J Clin Diagn Res. 10:BC19–BC21. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kevenaar ME, Meerasahib MF, Kramer P, van

de Lang-Born BMN, de Jong FH, Groome NP, Themmen AP and Visser JA:

Serum anti-mullerian hormone levels reflect the size of the

primordial follicle pool in mice. Endocrinology. 147:3228–3234.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zong X, Yu Y, Chen W, Zong W, Yang H and

Chen X: Ovarian reserve in premenopausal women with breast cancer.

Breast. 64:143–150. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Malisic E, Susnjar S, Milovanovic J,

Todorovic-Rakovic N and Kesic V: Assessment of ovarian function

after chemotherapy in women with early and locally advanced breast

cancer from Serbia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 297:495–503.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yu B, Lobo R, Crew K, Ferin M, Douglas N,

Nakhuda G and Hershman D: Predictive markers of

chemotherapy-induced menopause in premenopausal women under the age

of 40 with breast cancer. Cancer Res. 69 (2_Suppl)(S1118)2009.

|

|

23

|

Moore HCF, Unger JM, Phillips KA, Boyle F,

Hitre E, Porter D, Francis PA, Goldstein LJ, Gomez HL, Vallejos CS,

et al: Goserelin for ovarian protection during breast-cancer

adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 372:923–932. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wong M, O'Neill S, Walsh G and Smith IE:

Goserelin with chemotherapy to preserve ovarian function in

pre-menopausal women with early breast cancer: Menstruation and

pregnancy outcomes. Ann Oncol. 24:133–138. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Cerminaro RM, Gardner HM, Shultz SJ,

Dollar JM, Wideman L and Duffy DM: The accuracy of early

reproductive history and physical activity participation recall

across multiple age ranges. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 32:715–722.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Pourali L, Taghizadeh Kermani A,

Ghavamnasiri MR, Khoshroo F, Hosseini S, Asadi M and Anvari K:

Incidence of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea after adjuvant

chemotherapy with taxane and anthracyclines in young patients with

breast cancer. Iran J Cancer Prev. 6:147–150. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Obadipe J, Samuel T, Akinlalu A, Ajisafe

A, Olajide E and Albdulmumin L: Chemotherapy-induced ovarian

toxicity in female cancer patients from selected nigerian tertiary

health care. Niger J Exp Clin Biosci. 9(89)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Goldfarb SB, Bedoschi G, Turan V, Crown A,

Abdo N, Dickler MN and Oktay K: Impact of breast cancer

chemotherapy on ovarian damage and recovery. J Clin Oncol. 38

(15_suppl)(e24059)2020.

|

|

29

|

Coburn SB, Dionne-Odom J, Alcaide ML,

Moran CA, Rahangdale L, Golub ET, Massad LS, Seidman D, Michel KG,

Minkoff H, et al: The association between HIV status, estradiol,

and sex hormone binding globulin among premenopausal women in the

women's interagency HIV study. J Womens Health (Larchmt).

31:183–193. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Mauri D, Gazouli I, Zarkavelis G, Papadaki

A, Mavroeidis L, Gkoura S, Ntellas P, Amylidi AL, Tsali L and

Kampletsas E: Chemotherapy associated ovarian failure. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 11(572388)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ben-Aharon I, Granot T, Meizner I, Rizel

S, Yerushalmi R, Sulkes A and Stemmer SM: Chemotherapy-induced

ovarian failure in young breast cancer patients: The role of

vascular toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 32(15_suppl)(S9595)2014.

|