Introduction

Malakoplakia is a rare inflammatory disease

characterized by granuloma formation that commonly affects the

genitourinary system (1). However,

the disease can affect various anatomical locations; the bladder,

renal parenchyma, prostate and ureter, are respectively, the most

commonly affected areas (2). Other

documented locations are the gastrointestinal tract, skin,

epididymis, adrenal gland, bone and lungs, as well as multiple

organs in rare conditions (3,4).

Macroscopically, it often appears as soft, yellow-colored plaques

or nodules. Although it usually appears as a single lesion, it can

sometimes manifest as multiple lesions or may even be absent on a

visual inspection (1). Malakoplakia

can affect both sexes and is most common in individuals aged >40

years (2). The most common symptoms

include hematuria, recurrent urinary tract infections and urinary

flow obstruction (3). Although

malakoplakia is an inflammatory condition, it can mimic a tumor,

particularly when it appears as a mass-like lesion (5). The disease typically occurs in

immunocompromised individuals, such as those with diabetes

mellitus, kidney transplants, those with a prolonged use of

systemic corticosteroids, or a history of Escherichia coli

infection (2). However, to the best

of our knowledge, no case of malakoplakia induced by Morganella

morganii and mimicking a bladder tumor has been reported to

date in the literature.

Therefore, the present study describes the case of a

patient with bladder malakoplakia caused by Morganella

morganii mimicking a bladder tumor. In line with the CaReL

guidelines, a brief literature review was also included, and

references were examined to ensure correct citations (6,7). A

search was performed on Google Scholar using the key word

‘allintitle: Bladder Malakoplakia’ for publications dated between

2010 and 2025, yielding 37 results. From these, the 10 most recent

cases were randomly selected for a brief review.

Case report

Patient information

A 78-year-old male patient presented to Smart Health

Tower (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq) on December, 2024 with complaints of

dysuria, associated with urinary frequency, urgency and

incontinence, without hematuria. His past medical history included

cerebrovascular accidents and hypertension. He had undergone a

transurethral resection of the prostate in 2014 and had a femoral

fracture resulting from a road traffic accident in 1990. His

current medications included clopidogrel, rosuvastatin and

amlodipine.

Clinical findings

Upon a general examination, the patient appeared

alert and oriented with no acute distress. He relied on a

wheelchair for mobility assistance. His vital signs were within

normal limits. The abdominal examination revealed a soft,

non-tender abdomen with no palpable masses or suprapubic fullness.

External genitalia appeared normal with no signs of erythema,

discharge, or lesions.

Diagnostic approach

A urinalysis revealed a marked number of pus cells

per high-power field. An abdominal ultrasound demonstrated a

thickened bladder wall, indicative of cystitis. A urine culture

revealed the growth of Morganella morganii. At 20 days

thereafter, the patient returned with similar symptoms despite

antibiotic use [cefditoren pivoxil, 200 mg (1x2) for 3 weeks]. A

repeated urinalysis revealed similar findings. A subsequent

flexible cystoscopy revealed a tight urethra and multiple diffuse

sessile masses throughout the bladder (Fig. 1).

Therapeutic intervention

A transurethral resection of the masses was

performed and sent for histopathological analysis. Grossly, several

rubbery, gray-tan tissue fragments measuring 2.5 cm in total were

noted. A histopathological examination, was then performed on

5-µm-thick paraffin-embedded sections. The sections were fixed in

10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 24 h and then

stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Bio Optica Co.) for 1-2 min at

room temperature. The sections were then examined under a light

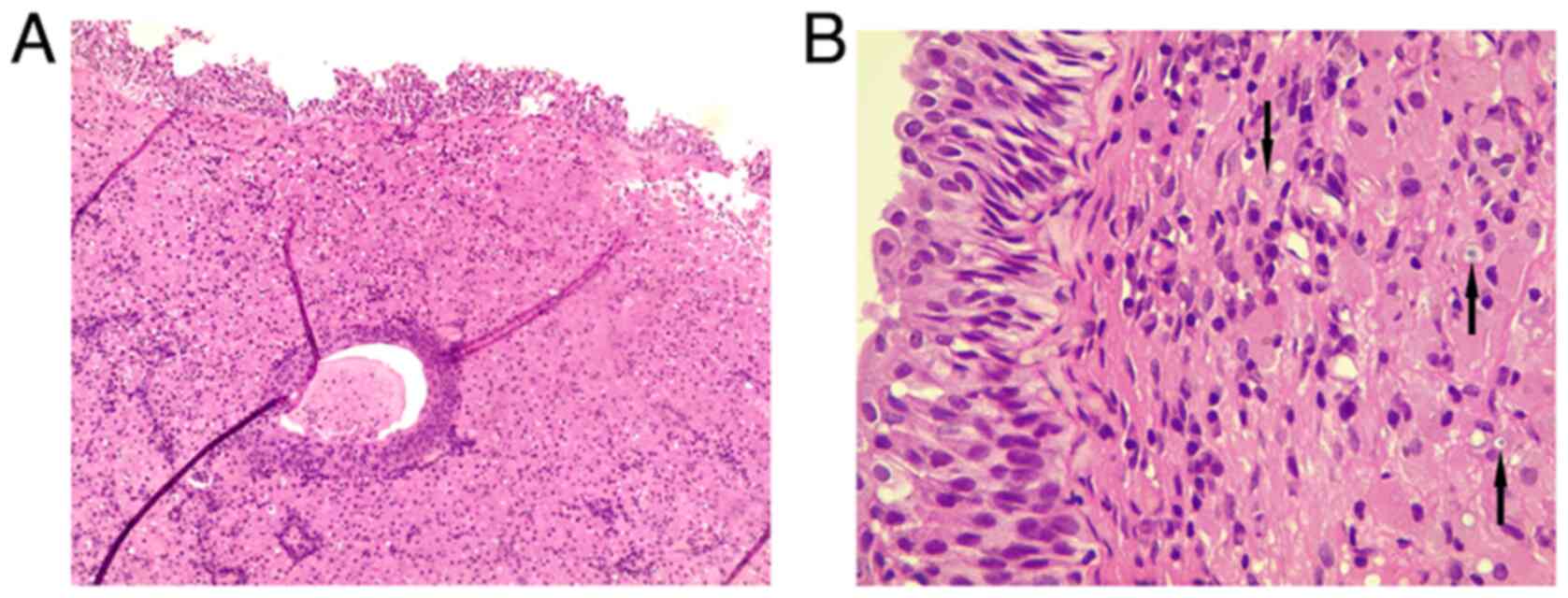

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). Histological analysis

revealed a reactive, flattened urothelial lining with mild

hyperplasia, featuring focal Brunn nests and cystitis glandularis.

There was a marked mucosal infiltrate composed of sheets of round

to polygonal histiocyte cells with abundant eosinophilic granular

cytoplasm, resembling von Hansemann cells (Fig. 2). These cells had round nuclei with

variable nucleoli and displayed rounded, concentric basophilic

intracytoplasmic inclusions, Michaelis-Gutmann-like bodies. The

tissue also contained a mixture of acute and chronic inflammation.

The muscularis propria was present and unaffected by the

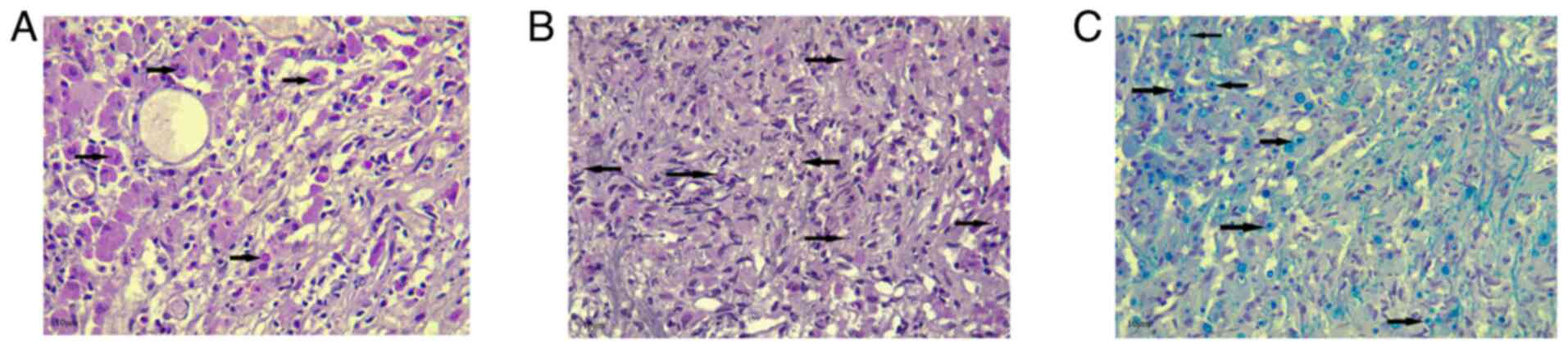

histiocytic infiltrate. Prussian blue, Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)

and PAS with diastase (D-PAS) staining was performed on

1.5-µm-thick paraffin-embedded sections. The sections were fixed in

10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 24 h.

Prussian blue, PAS and D-PAS staining (MilliporeSigma) were then

applied at room temperature for a duration of 20 min. The sections

were then examined under a light microscope (Leica Microsystems

GmbH). Prussian blue, PAS and D-PAS staining all yielded positive

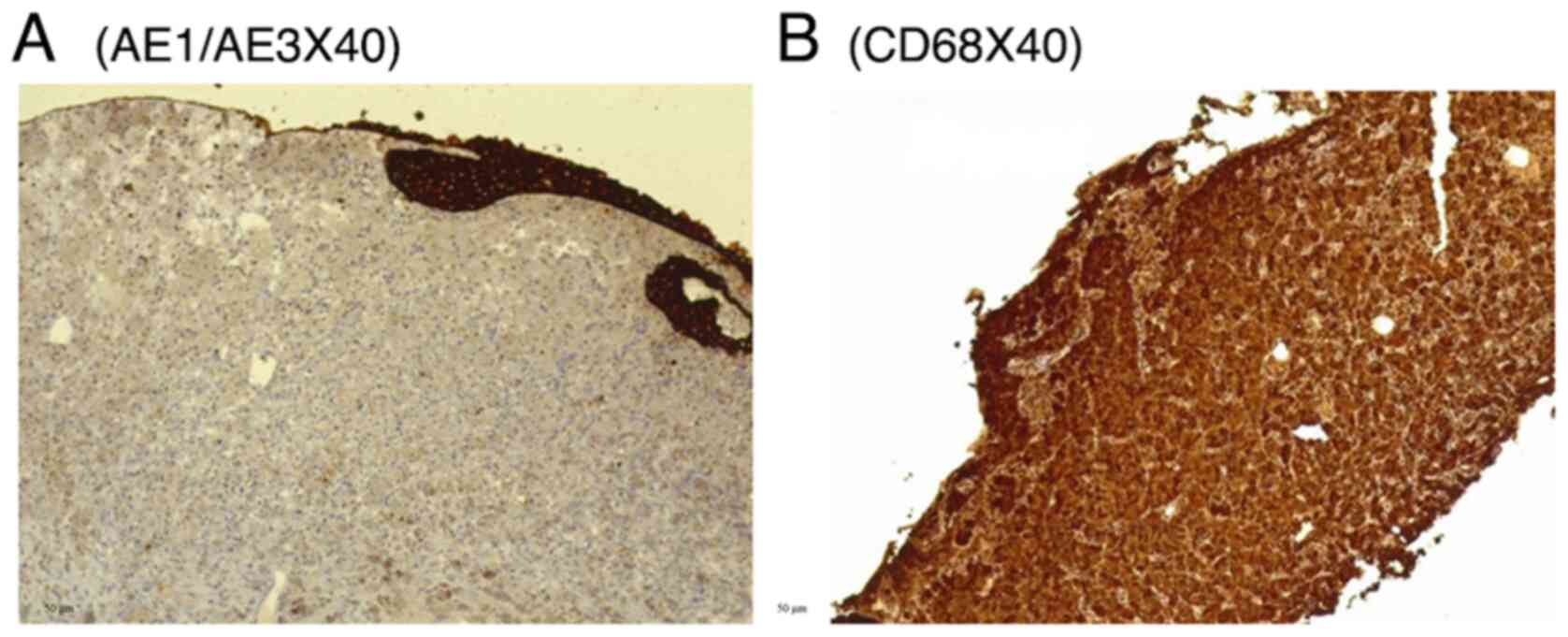

results, highlighting the cytoplasmic inclusion (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was then

performed for mucosal infiltrating cells. Serial 5-µm-thick

sections cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded bladder mass

tissue were mounted on coated slides, deparaffinized in xylene and

rehydrated through graded ethanol to distilled water. Antigen

retrieval was performed by heat-mediated epitope retrieval in 10 mM

citrate buffer (Ph 6.0) at 95-100˚C for 20 min, followed by cooling

for 20 min at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase activity was

quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 10 min at room

temperature. Sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in

PBS for 10 min at room temperature and rinsed with PBS (3x5 min).

Non-specific binding was blocked with 5% normal goat serum (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in PBS for 20 min at room temperature.

Primary antibodies [AE1/AE3 (1:100, clone AE1/AE3, cat. no. M3515),

S100 (1:200, polyclonal rabbit, cat. no. Z0311) and CD68 (1:100,

clone KP1, cat. no. M0814) (all from Dako; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.)] were applied and incubated with the sections for 30-60 min

at room temperature (alternatively overnight at 4˚C if required for

optimization). Following washes with distilled water, the sections

were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200, cat.

no. P0447) for AE1/AE3 and CD68, and HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, cat. no. P0448) for S100 (both from Dako;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.), for 30 min at room temperature. HRP

activity was visualized using DAB chromogen according to

manufacturer's instructions (monitoring 3-10 min), followed by a

water rinse. The sections were counterstained with Gill's

hematoxylin II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for ~30-60 sec,

rinsed, blued in running tap water, dehydrated, cleared and

coverslipped. Images were captured on a Leica light microscope

(Leica Microsystems GmbH); scale bars (50 µm) were added following

objective calibration. IHC revealed negativity for AE1/AE3 and S100

(data not shown), and strong positivity for CD68 (Fig. 4). Negativity for AE1/AE3 argued

against an epithelial cell origin, while negativity for S100 argued

against a granular cell tumor. Positivity for CD68 supported the

presence of histiocytic-type cells. The patient was administered

oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (800/160 mg) twice daily for 5

days. Following the urine culture results, treatment was switched

to intravenous meropenem (1 g) twice daily for 4 days. No

side-effects from the treatment were observed.

Follow-up and outcome

Following antibiotic therapy, the symptoms of the

patient partially improved at 1-month follow-up. The patient was

subsequently lost to follow-up.

Discussion

When involving the genitourinary system,

malakoplakia is more commonly observed in women (8). However, malakoplakia outside the

urinary tract is more common among males and is uncommon in

children (3). The precise cause of

malakoplakia is not yet fully understood. It is hypothesized that

malakoplakia results from impaired phagocytosis, linked to reduced

levels of intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate. A low

cyclic guanosine monophosphate to cyclic adenosine monophosphate

ratio disrupts the redox balance of the cell, compromising its

ability to kill bacteria effectively. This leads to a granulomatous

response, where bacterial remnants accumulate. These partially

digested bacteria calcify and cluster inside macrophages, forming

the characteristic Michaelis-Gutmann bodies (5). While a direct cause-and-effect

connection between coliform bacteria and malakoplakia has not yet

been firmly established, it has been reported that ~90% of patients

with malakoplakia also have coliform infections (8).

Morganella morganii, a bacterium from the

Enterobacteriaceae family, is a rod-shaped, Gram-negative,

facultatively anaerobic bacillus that includes two subspecies:

Morganii and sibonii. Formerly known as Proteus

morganii, it is typically part of the normal human gut

microbiota. However, in certain cases, particularly in hospital

settings, following surgery, or in individuals with weakened immune

systems and young children, it can lead to severe and potentially

life-threatening systemic infections, and naturally exhibits

resistance to several antibiotic classes (9). Herein, following a detailed literature

review, no cases of malakoplakia caused by Morganella

morganii were identified. In addition, Polisini et al

(2) reviewed the literature on

bladder malakoplakia and, across 35 articles reporting 36 cases,

did not identify any case of bladder malakoplakia associated with

Morganella morganii. Hence, the case presented herein may be

the first reported case of its kind.

Polisini et al (2) reported that approximately half of the

cases had recurrent urinary tract infections, particularly caused

by Escherichia coli, and that ~20% had immune system

disorders. Antibiotic therapy was administered in ~70% of cases,

and surgery was performed in 67% of cases. Among the surgical

procedures, approximately three-quarters involved transurethral

resection of the bladder. The recurrence rate was lower in patients

managed with both antibiotics and surgery than in those treated

with antibiotics alone (2).

Malakoplakia can also occur in unusual sites, such as the brain and

skeleton, which may indicate atypical Escherichia coli

strains or immune system abnormalities (3). A total of 10 cases of bladder

malakoplakia were reviewed herein (1,3,4,8,10-15).

All cases involved older individuals or adults, apart from 1

patient who was <2 years of ag. Michaelis-Gutmann bodies were

identified in all histopathological examinations, with 2 cases also

reporting von Hansemann cells. Among the cases that performed urine

cultures, only 2 cases were negative, while the others were

infected with Escherichia coli; 1 case also had a positive

blood culture for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Surgical

intervention was performed in 6 cases, while 4 cases were managed

conservatively, one of which experienced recurrent bladder

malakoplakia after 6 months (Table

I).

| Table IReview of 10 cases of malakoplakia in

the urinary bladder identified in the literature. |

Table I

Review of 10 cases of malakoplakia in

the urinary bladder identified in the literature.

| First author, year of

publication | Sex | Age (years) | Chief

complaint/symptoms | Imaging tests | Histopathological and

immunohistochemical examination | Culture tests | Other

examinations | Treatment | Follow-up | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ye, 2025 | F | N/A | Recurrent urinary

frequency for >1 year | CT: Intravesical mass

and upper ureteral calculi Cystoscopy: A mass at bladder neck and

urethral opening | HPE:

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies | N/A | N/A | Transurethral bladder

tumor resection | Not mentioned. | (11) |

| Tinguria, 2024 | F | 86 | Nausea, diarrhea,

foul-smelling urine, dysuria, hematuria, and low blood

pressure | CT: Atrophy of the

left kidney, & diffuse bladder wall thickening. | HPE: Foamy

epithelioid histiocytes, PAS-positive eosinophilic, calcified

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. IHC: +ve vimentin and CD-68, -ve

AE1/AE3. | Urine: +ve E.

coli, and P. aeruginosa, blood: +ve P.

aeruginosa. | CR: 252 µmol/l,

troponin: 2,695 ng/l, WBC count: 15.4x109/l, cystoscopy:

Plaque-like whitened lesions |

Piperacillin/tazobactam, | Recurrent bladder

malakoplakia after 6 months. | (3) |

| Jdiaa, 2023 | F | 70 | Fatigue, weakness,

decreased oral intake | CT: Bilateral

ureteral fullness suspicious for urothelial malignancy, bilateral

hydronephrosis | HPE and IHC: Sheets

of epithelioid histiocytes (CD68 positive), numerous neutrophils,

numerous CD38-positive plasma cells and occasional

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies | Blood and urine: +ve

E. coli | CR: 5.0 mg/dl

Hemoglobin: 6.9 g/dl WBC: 13.9x109/l | Transurethral bladder

tumor resection, ceftriaxone | Recovery with return

of kidney function to baseline | (12) |

| Gao, 2021 | M | 48 | Frequent and urgent

urination, right lumbago swelling and pain, as well as lower

abdominal discomfort | CT: A mass on the

right lateral bladder wall invading the right ureteral orifice | HPE: large numbers of

eosinophils and foam cells containing Michaelis-Gutmann bodies | Urine: +ve E.

coli | ESR: 98 mm/h CR: 123

µmol/l | Transurethral bladder

mass resection, tazobactam | No recurrence after 4

years | (13) |

| Pham, 2022 | F | 81 | Frequent and urgent

urination, Urge incontinence | CT: Severe bilateral

hydrou-reteronephrosis and bladder wall thickening | HPE:

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies | N/A | CR: 221 µmol/l | Cephalexin,

methenamine hippurate, supplemental vitamin C, ntravesical

gentamicin wash | Not mentioned | (14) |

| Parkin, 2020 | F | 82 | History of T1D,

rigors, lethargy, back pain, irritative voiding and urgency | CT: Nilateral

hydroureterone-phrosis and marked thickening of the bladder

base | HPE:

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies & von Hansemann cells. No evidence of

dysplasia or malignancy was seen. | Urine: recurrent

pan-sensitive E. coli. | WBC count:

5.4×10^9/l, hemoglobin: 96 g/l & CR: 234 µmol/l. | Surgical removal of

the bladder mass, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | No recurrence at 2

months. | (10) |

| Rabani, 2019 | F | 1.7 | voiding dysfunction,

pyuria & repeated UTI. | CT: right lateral

bladder wall mass. | HPE:

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. | Urine: +ve E.

coli. | Normal blood profile,

renal, and liver function tests. Cystoscopy: bladder mass. |

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | No recurrence after 9

years. | (8) |

| Sirithanaphol,

2018 | F | 66 | Gross hematuria,

dysuria | Cystoscopy:

white-yellowish plaque in bladder | HPE: sheets of large

macrophages with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, mixed

inflammatory infiltrate, and Michaelis-Gutmann bodies | Urine: -ve | Urinalysis: Pyuria

and hematuria | Ciprofloxacin,

prednisolone, methotrexate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Recovery of

symptoms | (15) |

| Lee, 2015 | F | 74 | Chills,

unremarkable physical examination. | CT: urinary bladder

postero-lateral wall mass. | HPE: papillary

urothelial carcinoma, & macrophages with Michaelis-Gutmann

bodies. IHC: +ve CD163 & CD68 & -ve Cam 5.2. | Urine: -ve. | WBC count:

12.9x10^3/µl, CRP: 77.4 mg/l, PCT: 64.28 µg/l CR: 101 µmol/l,

Urinalysis: hemopyuria. | IV ceftriaxone for

possible sepsis, transu-rethral resection | No recurrence at

12-month follow-up. | (1) |

| Ristić-Petrović,

2013 | F | 53 | General weakness,

low-grade fever and urinary hesitancy. | Not mentioned | HPE: von Hansemann

cells, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, infiltrated by dense collections

of lymphocytes. IHC: -ve cytokeratin, and Ki-67, +ve CD68 | Persistent E.

coli infections for 2 years. | Urine analysis:

Albuminuria, macrohematuria, pyuria and bacteriuria. Cystoscopy:

Thickened mucosa of the bladder similar to a neoplastic mass. | Surgical removal of

yellowish polypoidal lesions of the bladder | Not mentioned | (4) |

There may be instances in which malakoplakia occurs

without clinical or laboratory evidence of infection, but rather in

association with underlying neoplastic conditions. Darvishian et

al (16) reported the case of a

74-year-old female patient with papillary urothelial carcinoma of

the urinary bladder, with malakoplakia identified incidentally in a

bladder biopsy. Urinalysis revealed only a marked presence of

numerous red blood cells, with no evidence of pyuria or

bacteriuria. The urine culture did not reveal bacterial growth. A

tumor on the lateral wall of the urinary bladder was noted in

cystoscopy following initial examinations, and a biopsy was

subsequently done. Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry

were performed, exhibiting CD68 positivity. She underwent

conservative treatment without additional invasive intervention

(16).

There is currently no universally accepted standard

for the diagnosis and treatment of malakoplakia (5). Since the majority of studies on bladder

malakoplakia are case reports, with a notable absence of

comprehensive reviews (2),

diagnosing malakoplakia clinically can be challenging due to its

non-specific features. However, its appearance may mimic carcinoma,

which often leads to invasive or minimally invasive treatment, as

in the present case report, since malakoplakia generally requires

conservative treatment (17).

Its histological morphology changes over three

stages. In the first stage, a few cells with lymphocyte and plasma

cell infiltration represent glucolipid aggregation in

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. The second stage is marked by increased

histiocytes and von Hansemann cells, along with the formation of

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, which is the most distinctive feature. In

the third stage, histiocytes and von Hansemann cells decrease, and

fibrosis and collagen hyperplasia occur. Stains such as PAS,

Prussian blue, Alcian Blue and von Kossa effectively highlight

Michaelis-Gutmann bodies (18).

Increased levels of immunoreactive α1-antitrypsin are observed in

macrophages in malakoplakia, potentially aiding in the differential

diagnosis. Malakoplakia also presents with non-specific imaging

findings, and the affected areas may develop tumor-like nodules

(5). Still, imaging techniques, such

as computed tomography, ultrasonography and intravenous pyelogram

can help detect associated hydroureteronephrosis and identify upper

urinary tract filling defects, which are suggestive of its presence

(2). Immunohistochemistry also aids

in diagnosing malakoplakia by exhibiting negativity for AE1/AE3 and

S100, and positivity for CD68(3).

Immunohistochemistry staining in the present case report revealed

negativity for AE1/AE3 and S100, and positivity for CD68, similar

to has been previously reported (3).

The treatment of malakoplakia depends on the

severity of the condition and the underlying health conditions of

the patient. In the majority of cases, patients with bilateral or

multifocal involvement recover following antibiotic therapy. A

cholinergic agonist such as bethanechol chloride may be used

alongside antibiotics to help correct lysosomal dysfunction

(17). There are no established

guidelines regarding selection or duration of antibiotic therapy to

prevent malakoplakia recurrence. However, the use of antibiotics

that are effective against Gram-negative bacteria and those that

accumulate within macrophages has been recommended, as they may

help compensate for impaired phagocytic function. These antibiotics

include rifampicin, ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim. Due to the

potential adverse effects associated with quinolones, trimethoprim

is often the preferred option (7).

Vitamin C supplementation is recommended to help reduce the

inflammatory response. In patients with malakoplakia-related

complications, the regular monitoring of renal function and ongoing

cystoscopic surveillance are essential (10). Surgical removal has also been

recommended as an alternative treatment option for large lesions,

especially when complete elimination through medical therapy alone

may not be possible (8). Unifocal

disease may require surgical excision, and transurethral resection

may be needed for large lesions blocking the ureter. Based on the

risk-benefit ratio, the termination of immunosuppressive drugs is

often necessary (3). The patient in

the present case report was managed using a combination of

transurethral resection of the mass-like lesions and antibiotic

therapy. The patient demonstrated a favorable initial response with

a partial improvement of symptoms; however, the case was lost to

follow-up, preventing the further assessment of disease

progression. Consequently, the major limitation of the present case

report is the short follow-up period, which restricts the ability

to accurately evaluate the long-term outcome of the patient. In

addition, there is a lack of a representative image for S100

reactivity. The present study presents only a single-center case;

thus, further research is warranted to elucidate the potential role

and underlying mechanisms of Morganella morganii infection

in the pathogenesis of malakoplakia and to provide deeper insights

into this association.

In conclusion, bladder malakoplakia can also develop

due to infection with Morganella morganii and mimic a tumor;

thus, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of

bladder inflammation or masses.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RB and IA were major contributors to the conception

of the study, as well as to the literature search for related

studies. TOS, PWB and FHK were involved in the design of the study,

literature review and in the writing of the manuscript. FMF, BOM

and MNH were involved in the literature review, the design of the

study, the critical revision of the manuscript, and in the

processing of the table. AHA was the radiologist who performed the

assessment of the case. HAY was the pathologist who performed the

diagnosis of the case. FHK and RB confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for participation in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present case report and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lee SL, Teo JK, Lim SK, Salkade HP and

Mancer K: Coexistence of malakoplakia and papillary urothelial

carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Surg Pathol. 23:575–578.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Polisini G, Delle Fave RF, Capretti C,

Marronaro A, Costa AM, Quaresima L, Mazzaferro D and Galosi AB:

Malakoplakia of the urinary bladder: A review of the literature.

Arch Ital Urol Androl. 94:350–354. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Tinguria M: Recurrent bladder

malakoplakia: A rare bladder lesion mimicking malignancy. Bladder

(San Franc). 11(e21200018)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ristić-Petrović A, Stojnev S,

Janković-Veličković L and Marjanović G: Malakoplakia mimics urinary

bladder cancer: A case report. Vojnosanit Pregl. 70:606–608.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Boualaoui I, El Aboudi A, Mikou MA, El

Abidi H, Ouskri S, Mesbahi S, Ibrahimi A, Hashem ES and Yassine N:

Malignant masquerade: A case report of urachal malakoplakia

disguised as urachal tumor. Urol Case Rep.

60(103012)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA, Kakamad FH, Ahmed

JO, Baba HO, Hassan MN, Bapir R, Bapir HM, Bapir DA, Bapir SH, et

al: Predatory publishing lists: A review on the ongoing battle

against fraudulent actions. Barw Med J. 2:26–30. 2024.

|

|

7

|

Prasad S, Nassar M, Azzam AY,

García-Muro-San José F, Jamee M, Sliman RK, Evola G, Mustafa AM,

Abdullah HQ, Abdalla B, et al: CaReL guidelines: A consensus-based

guideline on case reports and literature review (CaReL). Barw Med

J: 2, 2024 doi: 10.58742/bmj.v2i2.89.

|

|

8

|

Rabani SM and Rabani SH: Bladder

malakoplakia simulating neoplasm in a young girl: Report of a case

and review of literature. Urol J. 16:614–615. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zaric RZ, Jankovic S, Zaric M,

Milosavljevic M, Stojadinovic M and Pejcic A: Antimicrobial

treatment of Morganella morganii invasive infections:

Systematic review. Indian J Med Microbiol. 39:404–412.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Parkin CJ, Acland G, Sulaiman B, Johnsun

ML and Latif E: Malakoplakia, a malignant mimic. Bladder (San

Franc). 7(e44)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ye H, Yu L and Chen Y: Ureteral calculus

complicated by bladder malakoplakia: A case report. Medicine

(Baltimore). 104(e42926)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jdiaa SS, Degheili JA, Matar CF, Mocadie

MF, Khaled CS and El Zakhem AM: Acute kidney injury secondary to

obstructive bladder malakoplakia: A case report. African J Urol.

29(40)2023.

|

|

13

|

Gao P, Hu Z and Du D: Malakoplakia of the

bladder near the ureteral orifice: A case report. J Int Med Res.

49(03000605211050799)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Pham CT, Edwards M, Chung AS and Chalasani

V: Malakoplakia causing poor bladder compliance and bilateral

hydroureteronephrosis. Société Int d'Urologie J. 3:281–282.

2022.

|

|

15

|

Sirithanaphol W, Sangkhamanon S,

Netwijitpan S and Foocharoen C: Bladder malakoplakia in systemic

sclerosis patient: A case report and review literature. J Endourol

Case Rep. 4:91–93. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Darvishian F, Teichberg S, Meyersfield S

and Urmacher CD: Concurrent malakoplakia and papillary urothelial

carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 31:147–150.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Purnell SD, Davis B, Burch-Smith R and

Coleman P: Renal malakoplakia mimicking a malignant renal

carcinoma: A patient case with literature review. Case Reports.

2015(bcr2014208652)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhang XY, Li J, Chen SL, Li Y, Wang H and

He JH: Malakoplakia with aberrant ALK expression by

immunohistochemistry: A case report. Diagn Pathol.

18(97)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|