Introduction

During pregnancy and the peripartum period, there

are changes in the coagulation system, which may lead to a

physiological hypercoagulable state (1). Hemodynamic factors and venous stasis

are certain factors that increase the risk of suffering an ischemic

stroke in pregnant women (2). These

changes predispose the pregnant patient to higher rates of

prothrombotic events, such as deep vein thrombosis, superficial

vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism or ischemic stroke

(3). Although pregnancy generally

increases the risk of developing thrombosis, the highest risk is

during peripartum period, which is ≤12 weeks following delivery

(4). Statistically, the majority of

stroke cases occur following delivery (50%) and in the peripartum

period (40%), with the lowest probability (10%) in the antepartum

period (5).

Imaging in pregnant patients is a diagnostic dilemma

due to radiation exposure (6).

Certain factors that influence the potentially harmful effects of

radiation from CT scans for pregnant patients are as follows:

Gestational age, the total dose of radiation that the patient is

exposed to, fetal exposure to radiation, and the need for the

administration of contrast agents. Whilst fetal exposure to

radiation from head CT scans is extremely low, the radiation dose

is markedly higher during head CT scans with intravenous contrast

due to multiple additional scans (7). Therefore, magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) is the recommended imaging method, using

non-contrast-enhanced time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography

(6).

Previous studies recommend that thrombolysis should

be considered when the expected benefits of treating

life-threatening or debilitating stroke outweigh the risk of

uterine bleeding (8,9). However, at present, to the best of our

knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that have

evaluated pregnant patients with thromboembolism. A recent review

highlighted that the risk associated with thrombolytic agents in

pregnant patients appears reasonable when balanced with the risk

associated with a disease that places the life of the patient in

danger (1). In addition, it has been

reported that the complications rate of thrombolysis in pregnant

patients is not higher than that of non-pregnant patients (1,3). In a

previous review article, of the 30 pregnant patients suffering a

thrombolysed stroke included in the review, the main complications

described were the following: Major bleeding (n=1), maternal

mortality due to arterial dissection (n=1), and spontaneous

abortions (n=3) (1). However,

pregnancy is still considered a relative contraindication for

thrombolysis (1).

Certain case studies have suggested that mechanical

thrombectomy can be performed safely during pregnancy, particularly

for pregnant patients who present with severe stroke [demonstrated

by high National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores]

(6,9). The patients in these cases experienced

excellent recovery and there was no impact on the infants (6). Moreover, it is widely accepted that

mechanical thrombectomy in pregnant patients is technically

feasible with acceptable rates of recanalization and maternal

outcomes and fetal outcomes (8).

Mechanical thrombectomy using the Penumbra system appears to be a

safe and effective treatment option for acute ischemic stroke

during pregnancy when thrombolysis is unsuitable (10). Therefore, mechanical thrombectomy

should be considered for pregnant patients as would be indicated in

non-pregnant patients (8).

Case report

A 29-year-old female patient, who was 38 weeks

pregnant, presented at the Emergency Room of University Emergency

Hospital of Bucharest, Romania, on a Sunday, in June 19, 2023. This

was the patient s first pregnancy, with no previous

spontaneous abortions. A cesarean section was scheduled for the

following day as the patient had two placentas. The patient was a

smoker (10 pack years), with no history of gestational diabetes,

preeclampsia, eclampsia or hypertension.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for sudden

onset symptomatology characterized by a motor deficit and numbness

of the right upper limb associated with pronunciation disorder. The

neurological clinical examination upon admission revealed the

following: Mild-moderate dysarthria (slurred speech, but

understandable); minor paralysis (flat nasolabial fold, smile

asymmetry); right brachial mono paresis 3/5 on the Medical Research

Council (MRC) scale; mild-moderate sensory loss on the right upper

arm; and ataxia in right upper arm. The patient had an a NIHSS

score of 7 points, and the score was disabling, in that the patient

was a 29-year-old with motor deficits in the dominant hand and who

was due to have a newborn the following day. Moreover, the patient

presented in the revascularization window at ~30 min from

symptomatology onset, as a thrombolysis code.

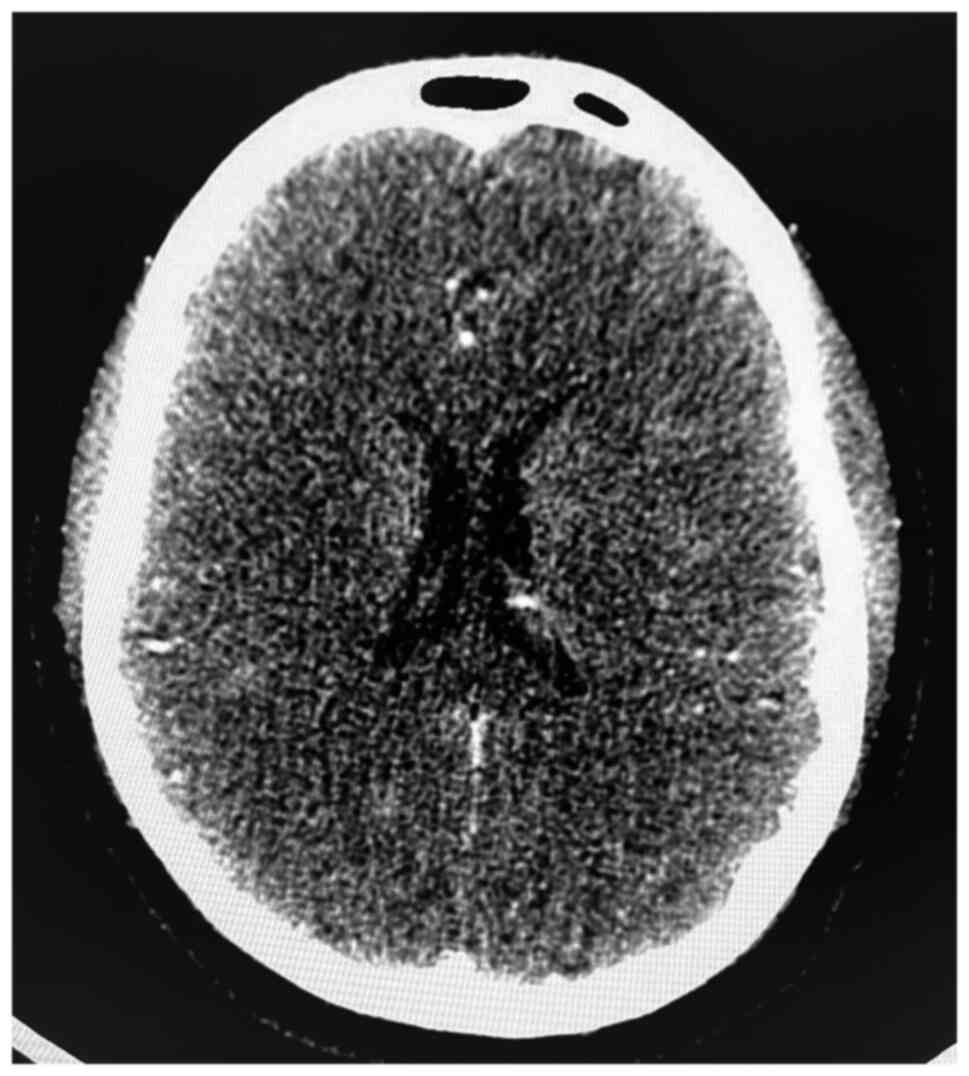

In terms of the diagnostic approach, in numerous

developing countries, including Romania, a routine cerebral MRI is

not commonly performed in emergency settings due to a combination

of factors, such as limited healthcare resources and infrastructure

challenges. Furthermore, Romania is still struggling to meet the

European standards of quality in healthcare (11). The patient in the present case report

was admitted during the night on a weekend; therefore, MRI was not

available. As a result, the first radiological investigation was a

native brain CT scan (intravascular contrast being avoided in

pregnancy), which did not reveal any cranial lesions. The native

cerebral CT scan in presented in Fig.

1. The clear native cerebral CT scan excluded other pathologies

that would explain a sudden neurological deficit (such as a

cerebral tumor) or that could contraindicate revascularization

therapy (such as hemorrhagic stroke). Given the pregnancy, medical

revascularization therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)

was excluded. Moreover, as a CT scan with contrast or a CT

angiography of the cerebral arteries were contraindicated in

pregnancy, and as the patient was at 38 weeks of gestation with a

viable fetus ready for delivery, a multidisciplinary team

comprising a neurologist and an obstetrician recommended an

emergency cesarean section. Although the procedure was planned for

the following day, the urgency of the case and the consent of the

family supported proceeding without delay. Following the delivery,

the neurological deficits persisted, with a NIHSS score of 7

points. Furthermore, even though the patient was still in the

thrombolysis window of 4.5 h following delivery, the major surgery

contraindicated revascularization with tPA due to the massive

hemorrhagic risk. However, the patient was still eligible for

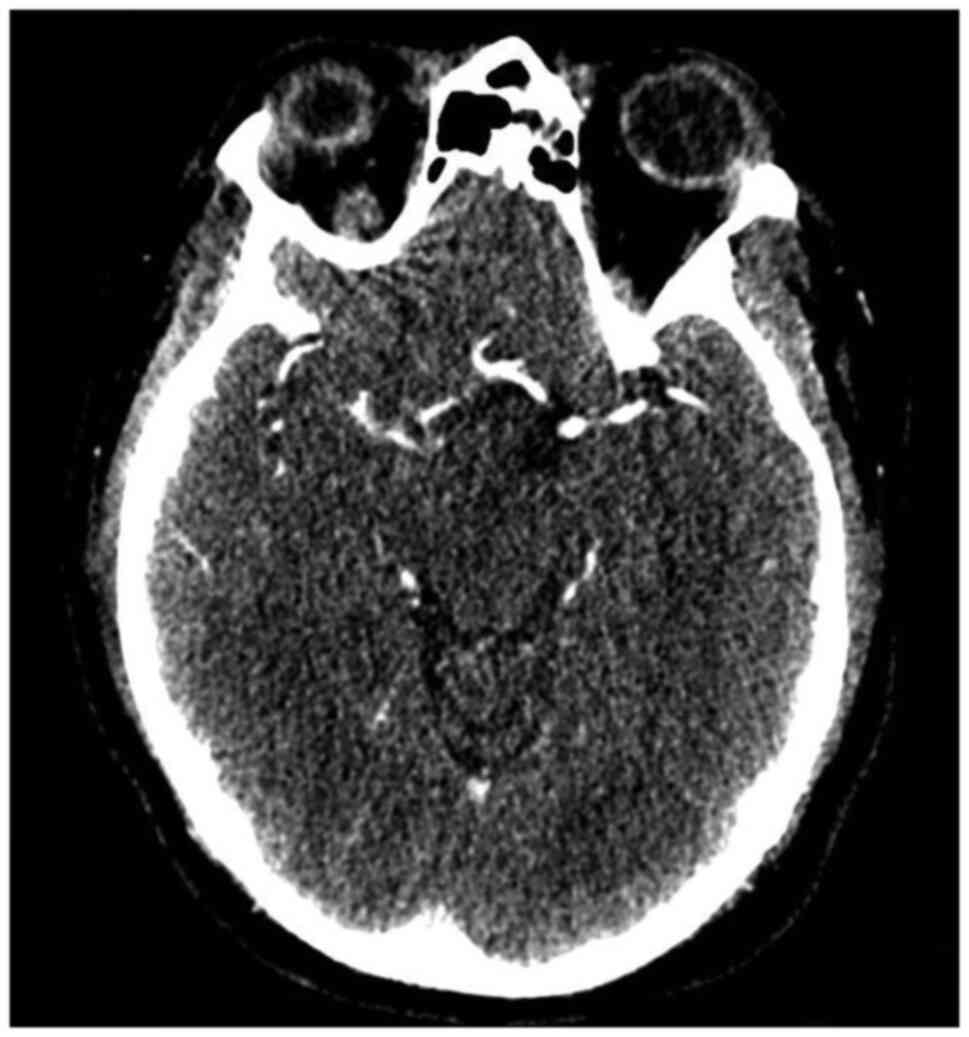

mechanical revascularization. Therefore, the patient underwent CT

angiography of the cerebral arteries, which did not detect large

vessel occlusion, and finally, mechanical thrombectomy was excluded

and drug treatment for secondary prevention with aspirin was

decided. The CT angiography of the cerebral arteries in presented

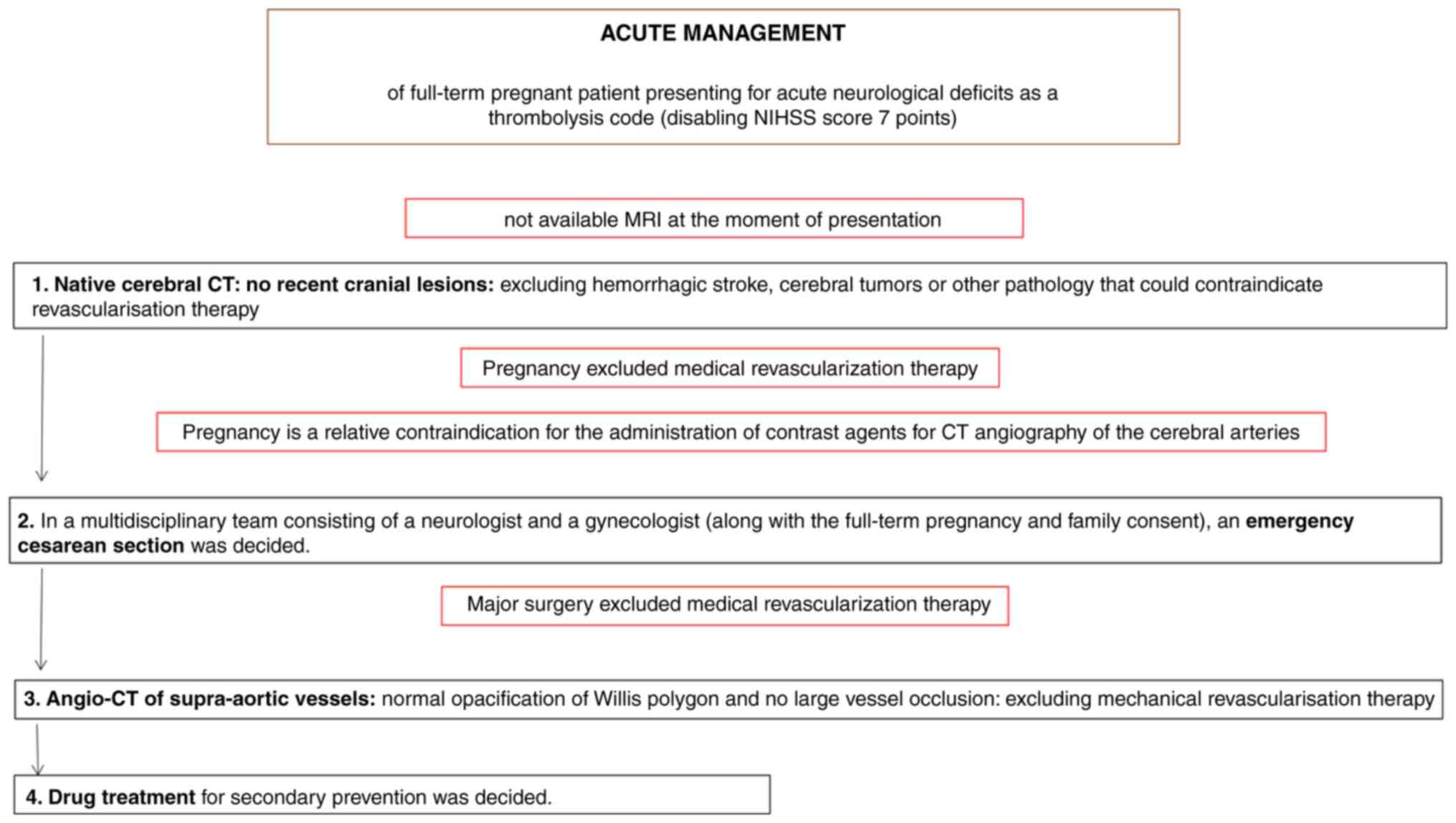

in Fig. 2. The acute management of

the patient is presented in Fig.

3.

The neonatal outcomes were favorable, with a

birthweight of 2.840 g, an Apgar score of 9, with favorable

neonatal adaptation and an increasing weight-growth curve. The

mother demonstrated an excellent post-operative recovery: On

post-operative day 1, the patient was mobilized, able to sit up and

ambulate without assistance. The motor deficit was limited to the

right upper limb (3/5 MRC). The patient reported no notable

abdominal pain and vital signs remained stable throughout. Wound

healing proceeded without complications, and the overall functional

status of the patient improved, allowing the performance of routine

maternal duties. By the end of the hospitalization period (from

June 19 until June 30, 2023), the patient was able to feed the

newborn with a bottle, even with a motor deficit in the right hand,

demonstrating marked adaptability and resilience.

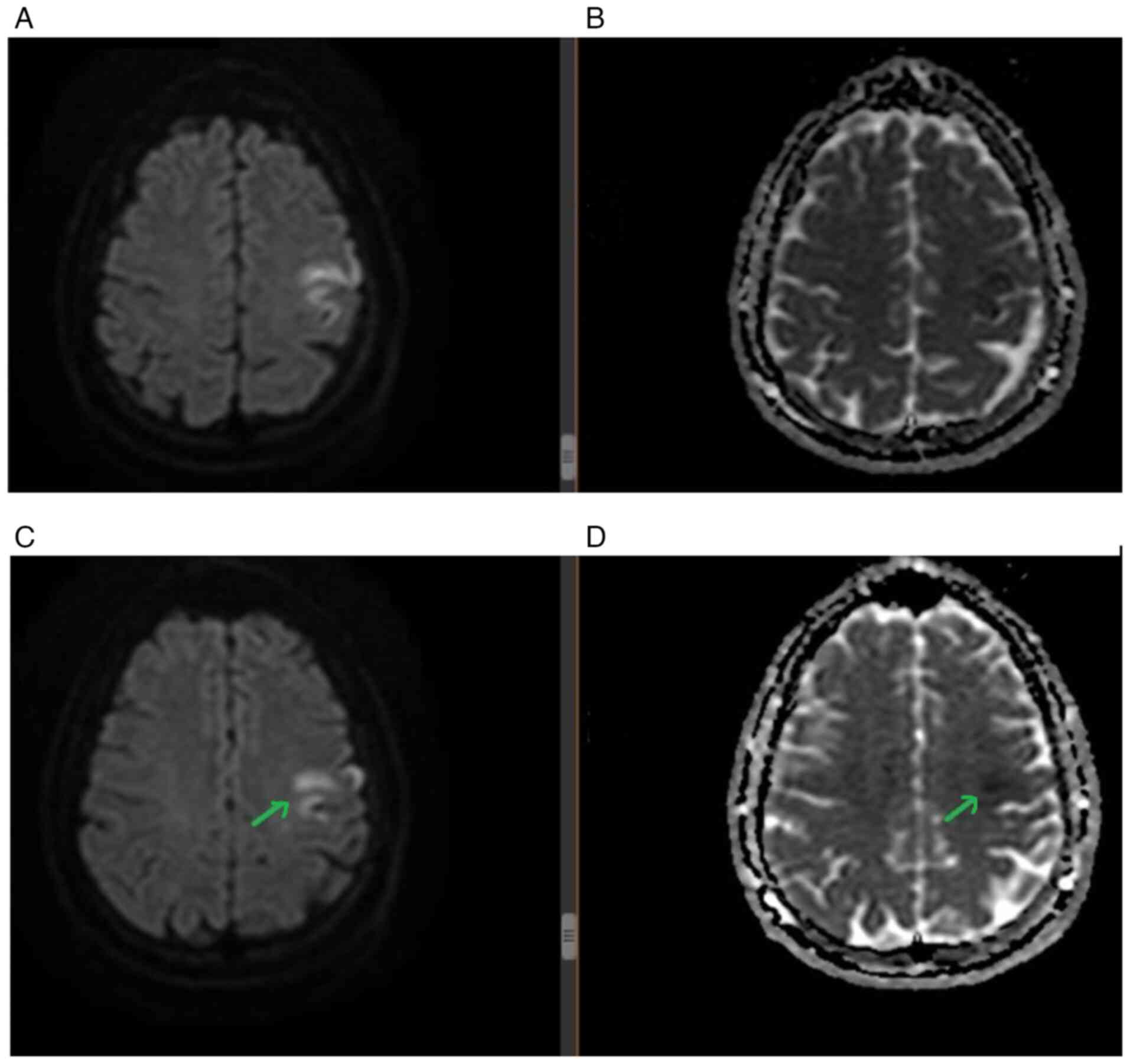

During admission, several paraclinical

investigations were performed. A brain MRI revealed a hyperintense

lesion in diffusion sequence with low apparent diffusion

coefficient correspondence at the frontal level of the left side,

affecting middle gyrus and precentral gyrus (Fig. 4). A Doppler ultrasound of

cervico-cerebral vessels did not detect atheroma plaques. A 24-h

electrocardiogram did not reveal atrial fibrillation episodes;

however, an outpatient extended cardiac rhythm monitoring was

recommended for 3-7 days. Microemboli detection revealed the

passage of 8-10 microemboli, suggestive of an interatrial

communication. A subsequent transesophageal ultrasound revealed a

small patent foramen ovale (PFO), and an 8-point Risk of

Paradoxical Embolism (RoPE) score of PFO was determined (no history

of hypertension, no history of diabetes, stroke or cortical

infarct, and an age of 29 years). This indicated an 84% chance that

the cause of the stroke of the patient was due to PFO. However, the

small anatomical proportions of the PFO did not indicate the need

for interventional closure (12).

Due to the PFO, a compression ultrasound of the lower limbs was

performed, and no deep vein thrombosis was identified. Furthermore,

vitamin B12 deficiency and mild anemia were detected.

However, laboratory tests for the usual hereditary

thrombophilic risk factors for arterial embolism, such as factor V

Leiden (G1691A), prothrombin G20210A, antithrombin deficiency,

protein C and S deficiencies and antiphosolipid syndrome, were

negative. The genotyping of the Factor V Leiden mutation was

performed using a quantitative PCR assay (LightCycler®

Factor V Leiden Mutation Detection kit; cat. no. BM05, Roche

Diagnostics) on the LightCycler® 2.0 instrument,

following the manufacturer s instructions. The prothrombin

G20210A variant was analyzed by quantitative PCR using the

LightCycler® Prothrombin G20210A Mutation Detection kit

(cat. no. BM06, Roche Diagnostics). Antithrombin functional

activity was measured using a chromogenic assay (STA®

Antithrombin; cat. no. HE34, Diagnostica Stago, Inc.), performed on

the STA-R Evolution analyzer. Protein C activity was assessed using

a chromogenic method (Protein C Chromogenic assay; cat. no. HE35,

Siemens Healthineers). Free Protein S antigen was quantified by

immunoturbidimetry (Liatest® Free Protein S; cat. no.

HE36, Diagnostica Stago, Inc.). Testing for lupus anticoagulant

followed the current International Society on Thrombosis and

Haemostasis (ISTH) guidelines and included both screening and

confirmatory assays: dRVVT screen and confirm reagents (LA1/LA2

dRVVT; cat. no. HE32, Werfen/Instrumentation Laboratory) and

aPTT-based lupus-sensitive assay (SynthASil®; cat. no.

HE32, Werfen). IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies were measured

using ELISA kits (QUANTA Lite® ACA IgG/IgM; cat. nos.

IM328, Inova Diagnostics, Inc.). IgG and IgM anti-β2GPI antibodies

were determined using ELISA (QUANTA Lite® β2-GPI

IgG/IgM; cat. no. IM225, Inova Diagnostics, Inc.).

Building upon laboratory investigations suggesting a

potential thrombophilic status, genetic testing revealed a

homozygous mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

(MTHFR) gene and heterozygous mutation in the plasminogen activator

inhibitor-1 gene. The genotyping of MTHFR C677T and A1298C

polymorphisms was performed using

LightCycler®-compatible quantitative PCR assays with

hybridization probes (LightMix® kit MTHFR C677T/A1298C;

cat. no. BM33, TIB MOLBIOL Syntheselabor GmbH). Reactions were run

on the LightCycler® 2.0 instrument following the

manufacturer s protocol. The PAI-1 promoter 4G/5G polymorphism

was detected using a LightCycler®-based quantitative PCR

assay (LightMix® kit PAI-1 4G/5G; cat. no. BM35, TIB

MOLBIOL Syntheselabor GmbH), with allele discrimination performed

by melting-curve analysis on the LightCycler® 2.0

system. The results of thrombophilia screening and genetic

thrombofilia testing are presented in Table I.

| Table IThrombophilia status results. |

Table I

Thrombophilia status results.

| Laboratory test | Result | Reference

interval |

|---|

| Thrombophilia

screening | | |

|

Factor V

Leiden with activated protein C | 91.1 | 38-144/sec |

|

Factor V

Leiden without activated protein C | 32.2 | 24-184/sec |

|

Activated

protein C ratio | 2.83 | ≥2.3 |

|

Antithrombin

deficiency | 142 | 83-128% |

|

Protein C

deficiency | 135 | 70-140% |

|

Protein S

deficiency | 60.4 | 54.7-123.7% |

|

Lupus

anticoagulant screen | 38.5 | 29-39.76 |

|

Lupus

anticoagulant confirm | 28.9 | 27.6-36 |

|

Homocisteinemia | 7.65 | 4.3-11.1/µmol/l |

| Genetic thrombophilia

testing | | |

|

MTHFR gene:

A1298C mutation | Homozygous

genotype | Negative |

|

MTHFR gene:

C677T mutation | Negative | Negative |

|

PAI-1 gene

(polimorfism 675 4G/5G) | Heterozygote

genotype | Negative |

|

Factor V

Leiden mutation | Negative | Negative |

|

Factor II

(prothrombin) mutation | Negative | Negative |

Due to the existing PFO with a high RoPE score and

positive thrombophilic status, anticoagulation medication was

decided for stroke secondary prevention, during hospitalization and

in the first month after delivery with low molecular weight

heparin, enoxaparin (80 mg, corresponding to 0.8 ml twice daily for

a patient with a weight of 80-kg). Following this period, the

patient received bridging therapy with both enoxaparin and

acenocoumarol for 5 days. After these 5 days, oral anticoagulation

with acenoumarol was dose-adjusted to maintain an international

normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0-3.0. Finally, following adjustments,

the patient remained on a dose of 2 mg of acenocoumarol daily.

Discussion

The first particularity of the present case report

is derived from the therapeutic management: The series of medical

interventions when admitting the 38-week pregnant patient with

acute ischemic stroke in the revascularization window. A native

brain CT was initially performed to rule out another cause of acute

neurological deficit, and after excluding cerebral tumors or

hemorrhagic stroke, an emergency cesarean section was performed

under general anesthesia. Subsequently, a CT angiography of the

cerebral arteries was performed. Finally, a mechanical

revascularization procedure would have followed if a large vessel

occlusion was identified.

The first factor that should highlight potential

thrombolysis in pregnant patients is stroke severity: NIHSS score,

stroke position, consciousness, motor and sensitive deficits,

language disorder and speech disorder (1). The second factor that should be taken

into account is the risk of bleeding, considering previous

pathologies of the patient, such as the bleeding history,

hypertension and other known coagulopathies (1). Personal factors should also be taken

into account, such as age, medical history and body weight

(1). Lastly, from an obstetrical

point of view, the decision to thrombolyze a pregnant patient

should consider gestational age and obstetrical conditions

(1). Other previous personal

pathologies may increase the risk of stroke in pregnancy, such as:

Hematologic diseases (sickle cell anemia, thrombocytopenia and

thrombophilia), cardiac disease (hypertension and heart disease),

diabetes and migraine-type headaches (6). Other risk factors include smoking and

alcohol consumption (5,13).

The second particularity of the present case

originates from the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke in a

full-term pregnant patient, and the evaluation the possible

etiologies of cryptogenic stroke. Therefore, the present case

report emphasizes the importance of evaluating thrombophilic status

and PFO in patients with ischemic stroke at a young age. The most

probable etiology of the stroke was the procoagulant status of the

patient based on the pregnancy itself, the peripartum period of the

patient and the positive genetic thrombophilic status. Notably, the

patient had no personal history pointing towards this diagnosis,

such as history of spontaneous abortions, superficial or deep

venous thrombosis, or pulmonary thromboembolism.

It has been suggested that PFO is an independent

risk factor for ischemic stroke, particularly in young patients

with cryptogenic stroke; however, the causality between PFO and

ischemic stroke is not yet confirmed (14,15).

Moreover, when patient suffering a stroke is diagnosed with PFO,

this is not an indication that PFO was the cause of the stroke;

therefore, secondary prevention for these patients is still

debatable (14). However, in the

event that a patient suffering a stroke is discovered with both PFO

and prothrombotic coagulopathies, oral anticoagulants should be

considered for secondary prevention, rather than platelet

inhibitors (14). Other studies have

suggested that warfarin is superior to platelet inhibitors as a

secondary prevention for PFO-related stroke cases (16,17).

Moreover, the placement of infarct localization of a

PFO-related stroke is due to the physiopathological mechanism of a

PFO: As they are an interatrial shunt, they will allow smaller

emboli to pass through the PFO (left-right) and then reach multiple

scattered places within the brain on both hemispheres (18). Thus, in terms of imaging

characteristics, PFO-related stroke is usually revealed as a single

cortical ischemic lesion or multiple small scattered ischemic

lesions (18).

For PFO-related strokes, thrombogenic conditions are

usually present, as they lead to a predisposition of venous

thrombus formation and further lead to a paradoxical embolism

(18). Pezzini et al

(14) reported that the G20210A

variant of the prothrombin gene and the G1691A mutation of factor V

gene had a higher rate of prevalence in patients with stroke and

PFO, suggesting a possible pathophysiological role of these minor

thrombophilias. By contrast, their study also reported that the

homozygous deficient TT MTHFR genotype was not a genetic minor

thrombophilia found in patients with PFO-related stroke (14). Furthermore, a recent study reported

that usual risk factors for stroke (such as smoking, dyslipidemia

or diabetes) are not associated with risk for PFO-related stroke

(19). Moreover, that study

highlighted that thrombophilias or intracardiac shunt size are not

associated with stroke occurrence in patients with PFO (19).

Lastly, the third particularity of the present case

comes from the medication treatment. From a neurological

perspective, secondary prevention following cryptogenic stroke is

generally achieved with aspirin or a direct oral anticoagulant. A

total of two large randomized trials, NAVIGATE ESUS and RE-SPECT

ESUS, evaluated the efficiency of rivaroxaban and dabigatran,

respectively, compared with aspirin; however, the results

demonstrated no definitive superiority of direct oral

anticoagulants over aspirin, and the evidence remains under

evaluation (19-21).

However, for the patient in the present case report, with both PFO

and positive thrombophilic status, anticoagulation was decided as

secondary prevention: Considering the postpartum status of the

patient, low molecular weight heparin was administered for the

first month following delivery, and acenocoumarole was then

administered for the ensuing 3 months.

Furthermore, from a psychological perspective,

following ischemic stroke, young adults are more predisposed to

fatigue, depression and anxiety (23,24).

Other feelings may include anger, denial, frustration, negative

body image and impaired self-esteem (24). Additionally, certain common practical

problems that young stroke survivors experience are family

conflicts, loss of home, loss of employment and loss of spouse

(25), with psychological

adjustments including reduced quality of life (associated with

dependence, being single and unemployment), financial stress,

conflicts with spouses, children, childcare difficulties, sexual

problems, separation, reduced social and leisure activities,

disruption of self and identity and reduced life satisfaction

(24). It has been suggested that

depot injectable medication may increase quality of life in

patients with psychotic symptoms (26). Furthermore, pregnancy and the

peripartum period is considered a critical period for marriage, and

pregnant women are at risk for developing marital burnout (27). Burnout syndrome is characterized by

psychiatric, psychosomatic, somatic and social symptoms; whilst

chronic fatigue, continuous exhaustion and mental stressors may

arise during pregnancy and peripartum; therefore, this is a period

where women are predisposed to burnout syndrome (28). Medical treatment for psychiatric

symptoms in pregnant patients or patients during the peripartum

period should be carefully considered and given only if the

benefits exceed the risks for the infant.

In conclusion, the particularity of the case

described herein originates from the series of medical

interventions in a full-term pregnant patient who presented with

acute ischemic stroke in the revascularization window: Clinical

examination, native head CT scan, emergency cesarean section, CT

angiography of the cerebral arteries, and, eventually, mechanical

thrombectomy, were performed. The present case report also

emphasizes the importance of evaluating inherited genetic

thrombophilia and PFO in young patients suffering a stroke, and

highlights the need for psychological and psychiatric evaluation

for possible reactive depression, anxiety and burnout in young

patients suffering a stroke, particularly in the peripartum

period.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

All authors (AIV, ADT, CN and ST) were involved in

the conceptualization of the study, as well as in the writing of

the initial draft of the manuscript, and in the writing, revising

and editing of the manuscript. AIV and CN were involved in the

curation of the patient s data. AIV and ADT were involved in

the analysis of the patient s data. AIV was involved in the

analysis of the patient s data. AIV, ADT, CN and ST were

involved in the description of the medical procedure performed for

the patient in the present case report, the series of interventions

and the series of etiological investigations performed. CN and ST

were the physicians that handled the case. AIV participated in the

therapeutic management of the patient as a resident and ADT was

involved in the writing of the manuscript as a medical student. CN

was the primary neurologist who was on the case and obtained the

consent, the medical images and was responsible for the main

medical decisions. CN and ST supervised the study and were involved

in data validation and in the critical review of the manuscript.

AIV and CN confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Complete written informed consent was obtained from

the patient for her participation in the present case report.

Patient consent for publication

Complete written informed consent was obtained from

the patient for the publication of the present case report and the

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Sousa Gomes M, Guimarães M and Montenegro

N: Thrombolysis in pregnancy: A literature review. J Matern Fetal

Neonatal Med. 32:2418–2428. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Dicpinigaitis AJ, Sursal T, Morse CA,

Briskin C, Dakay K, Kurian C, Kaur G, Sahni R, Bowers C, Gandhi CD,

et al: Endovascular thrombectomy for treatment of acute ischemic

stroke during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. Stroke.

52:3796–3804. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Leonhardt G, Gaul C, Nietsch HH, Buerke M

and Schleussner E: Thrombolytic therapy in pregnancy. J Thromb

Thrombolysis. 21:271–276. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

del Zoppo GJ, Levy DE, Wasiewski WW,

Pancioli AM, Demchuk AM, Trammel J, Demaerschalk BM, Kaste M,

Albers GW and Ringelstein EB: Hyperfibrinogenemia and functional

outcome from acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 40:1687–1691.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

James AH, Bushnell CD, Jamison MG and

Myers ER: Incidence and risk factors for stroke in pregnancy and

the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol. 106:509–516. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bhogal P, Aguilar M, AlMatter M, Karck U,

Bäzner H and Henkes H: Mechanical thrombectomy in pregnancy: Report

of 2 cases and review of the literature. Interv Neurol. 6:49–56.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Hoang JK, Wang C, Frush DP, Enterline DS,

Samei E, Toncheva G, Lowry C and Yoshizumi TT: Estimation of

radiation exposure for brain perfusion CT: Standard protocol

compared with deviations in protocol. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

201:W730–W734. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Al-Mufti F, Schirmer CM, Starke RM,

Chaudhary N, De Leacy R, Tjoumakaris SI, Haranhalli N, Abecassis

IJ, Amuluru K, Bulsara KR, et al: Thrombectomy in special

populations: Report of the society of neuroInterventional surgery

standards and guidelines committee. J Neurointerv Surg.

14:1033–1041. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Demchuk AM: Yes, intravenous thrombolysis

should be administered in pregnancy when other clinical and imaging

factors are favorable. Stroke. 44:864–865. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Aaron S, Shyamkumar NK, Alexander S, Babu

PS, Prabhakar AT, Moses V, Murthy TV and Alexander M: Mechanical

thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke in pregnancy using the

penumbra system. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 19:261–263.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Tereanu C, Minca D, Costea R, Janta D,

Grego S, Ravera L, Pezzano D and Viganò P: ExpIR-RO: A

collaborative International project for experimenting voluntary

incident reporting in the public healthcare sector in Romania. Iran

J Public Health. 40:22–31. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Egred M, Andron M, Albouaini K, Alahmar A,

Grainger R and Morrison WL: Percutaneous closure of patent foramen

ovale and atrial septal defect: Procedure outcome and medium-term

follow-up. J Interv Cardiol. 20:395–401. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Furtunescu F, Minca DG, Vasile A and

Domnariu C: Alcohol consumption impact on premature mortality in

Romania. Rom J Leg Med. 17:296–302. 2009.

|

|

14

|

Pezzini A, Del Zotto E, Magoni M, Costa A,

Archetti S, Grassi M, Akkawi NM, Albertini A, Assanelli D, Vignolo

LA and Padovani A: Inherited thrombophilic disorders in young

adults with ischemic stroke and patent foramen ovale. Stroke.

34:28–33. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Safouris A, Kargiotis O, Psychogios K,

Kalyvas P, Ikonomidis I, Drakopoulou M, Toutouzas K and Tsivgoulis

G: A narrative and critical review of randomized-controlled

clinical trials on patent foramen ovale closure for reducing the

risk of stroke recurrence. Front Neurol. 11(434)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Orgera MA, O Malley PG and Taylor AJ:

Secondary prevention of cerebral ischemia in patent foramen ovale:

Systematic review and meta-analysis. South Med J. 94:699–703.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kheiri B, Simpson TF, Osman M, Golwala H,

Radaideh Q, Dalouk K, Stecker EC, Zahr F, Nazer B and Rahmouni H:

Meta-analysis of secondary prevention of cryptogenic stroke.

Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 21:1285–1290. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kim BJ, Sohn H, Sun BJ, Song JK, Kang DW,

Kim JS and Kwon SU: Imaging characteristics of ischemic strokes

related to patent foramen ovale. Stroke. 44:3350–3356.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Badea RŞ, Ribigan AC, Grecu N, Terecoasǎ

E, Antochi FA, Bâldea Mihǎilǎ S, Tiu C and Popescu BO: Differences

in clinical and biological factors between patients with

PFO-related stroke and patients with PFO and no cerebral vascular

events. Front Neurol. 14(1104674)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Diener HC, Sacco RL, Easton JD, Granger

CB, Bar M, Bernstein RA, Brainin M, Brueckmann M, Cronin L, Donnan

G, et al: Antithrombotic treatment of embolic stroke of

undetermined source: RE-SPECT ESUS elderly and renally impaired

subgroups. Stroke. 51:1758–1765. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Diener HC, Sacco RL, Easton JD, Granger

CB, Bernstein RA, Uchiyama S, Kreuzer J, Cronin L, Cotton D, Grauer

C, et al: Dabigatran for prevention of stroke after embolic stroke

of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 380:1906–1917.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Diener HC, Easton JD, Granger CB, Cronin

L, Duffy C, Cotton D, Brueckmann M and Sacco RL: RE-SPECT ESUS

Investigators. Design of Randomized, double-blind, evaluation in

secondary stroke prevention comparing the efficacy and safety of

the oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate vs.

acetylsalicylic acid in patients with embolic stroke of

undetermined source (RE-SPECT ESUS). Int J Stroke. 10:1309–1312.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

de Bruijn MA, Synhaeve NE, van Rijsbergen

MW, de Leeuw FE, Mark RE, Jansen BP and de*Kort PL: Quality of life

after young ischemic stroke of mild severity is mainly influenced

by psychological factors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 24:2183–2188.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Morris R: The Psychology of Stroke in

Young Adults: The roles of service provision and return to work.

Stroke Res Treat. 2011(534812)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Teasell RW, McRae MP and Finestone HM:

Social issues in the rehabilitation of younger stroke patients.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 81:205–209. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Trifu S and Trifu AD: Receptor profiles of

atypical antipsychotic molecules. Chem Mater Sci. 82:113–128.

2020.

|

|

27

|

Moravejjifar M, Hassannia R, Esmaeili H,

Tehrani H and Vahedian*Shahroodi M: Predictors of marital burnout

in pregnant women based on social cognitive theory components. J

Midwifery Reprod Health. 9:2834–2843. 2021.

|

|

28

|

Trifu S: Neuroendocrine insights into

burnout syndrome. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 15:404–405.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|