Introduction

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reports

that inhalants continue to be one of the most commonly abused

substances in the USA (1). They are

used through methods such as sniffing, huffing, or bagging and

often involve easily accessible products such as compressed air

duster cans containing hydrofluorocarbons, including

tetrafluoroethane and difluoroethane. These chemicals induce rapid

psychoactive effects via gamma-aminobutyric acid enhancement and

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor receptor suppression; however, their

overall toxic effects are not yet fully defined (2). Compressed air duster cans are widely

available inhalants composed of liquefied hydrofluorocarbon

propellants, most commonly difluoroethane. These products are

intended for cleaning electronic equipment, but can produce

significant toxicity when misused. Safety data for these agents

warn that concentrated inhalation may lead to respiratory

irritation, altered mental status, cardiac conduction

abnormalities, arrhythmias, impaired circulation, loss of

consciousness and even sudden death. High-level exposure has also

been shown to be associated with renal dysfunction and other

systemic complications (3,4). Although the majority of reported cases

involve individuals aged between 18 and 50 years, the 2019 National

Youth Risk Behavior Survey noted that ~6.5% of younger students had

engaged in the use of inhalants, highlighting early-age

vulnerability (5).

The present study describe the case of a young male

patient with severe multi-organ toxicity (cardiac, renal and

skeletal) following chronic compressed air duster use, who

exhibited significant improvement with supportive care and was

ultimately discharged. The present case report underscores the need

for clinicians to recognize the varied presentations of duster

abuse to ensure timely diagnosis and appropriate acute

management.

Case report

A 29-year-old Caucasian male with a history of

chronic alcohol use disorder, daily tetrahydrocannabinol use,

asthma, hypertension and psychiatric comorbidities presented to the

Emergency Department of Wellstar Spalding Regional Hospital

(Griffin, USA) May 12, 2025 following a syncopal episode. He

described several days of progressive weakness, dizziness and joint

pain requiring cane-assisted ambulation. On the day of admission,

he collapsed while descending stairs. This event was witnessed, and

there was no evidence of seizure activity or post-ictal confusion.

He admitted to the extensive daily use of compressed air duster

cans for several months, experiencing euphoria and increasing

nausea with each use. On the day of presentation, he had used 8

cans of dust inhalant, instead of 4 as per his routine use.

Upon arrival, he was hypotensive and symptomatic. An

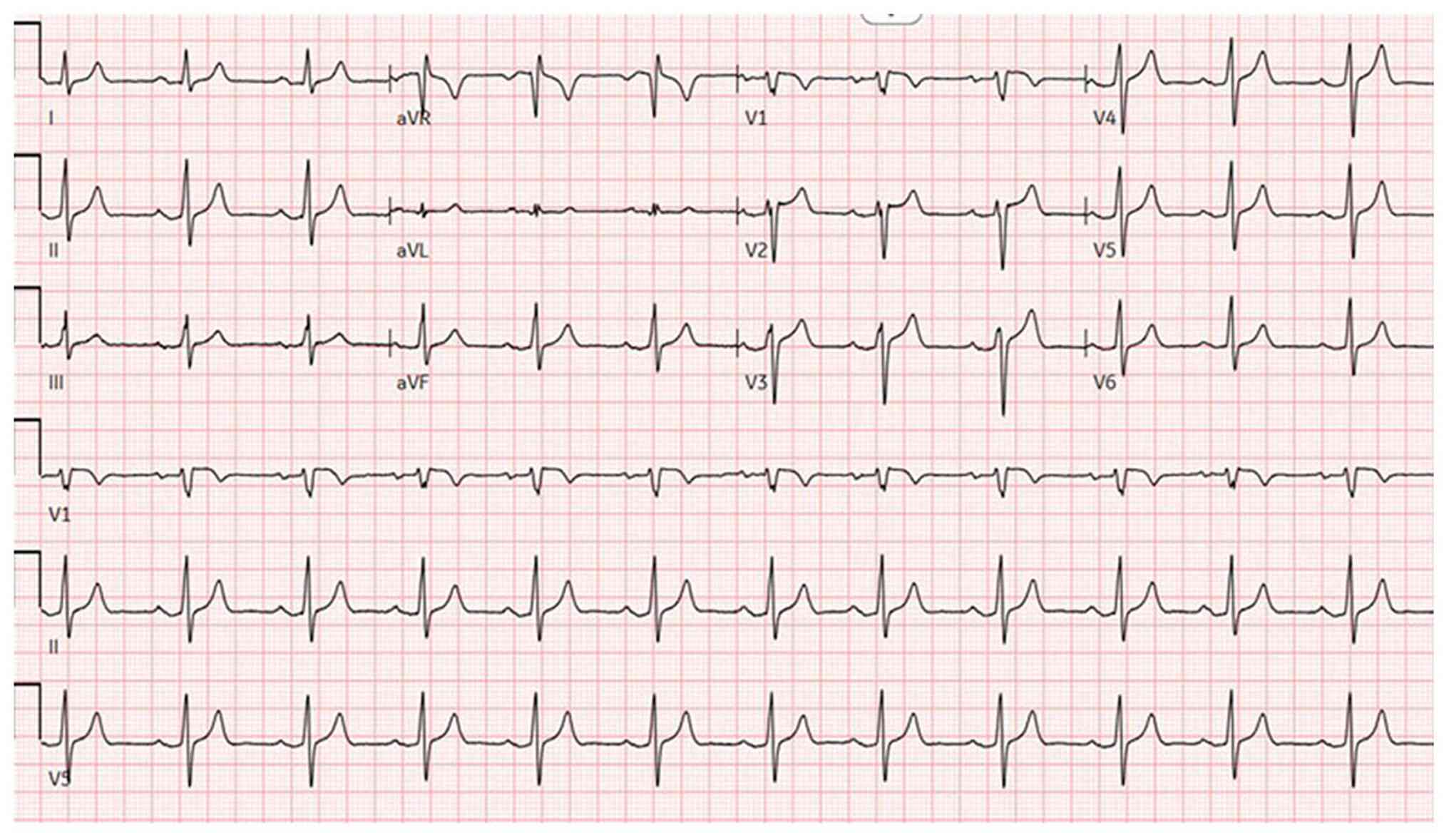

electrocardiogram (Fig. 1)

demonstrated sinus rhythm with peaked T waves. Laboratory results

revealed hyperkalemia, elevated levels of troponins (in thousands;

ng/l), acute kidney injury and high anion gap metabolic acidosis.

Urine drug screening yielded negative results, while salicylate and

acetaminophen levels were normal. Other laboratory results are

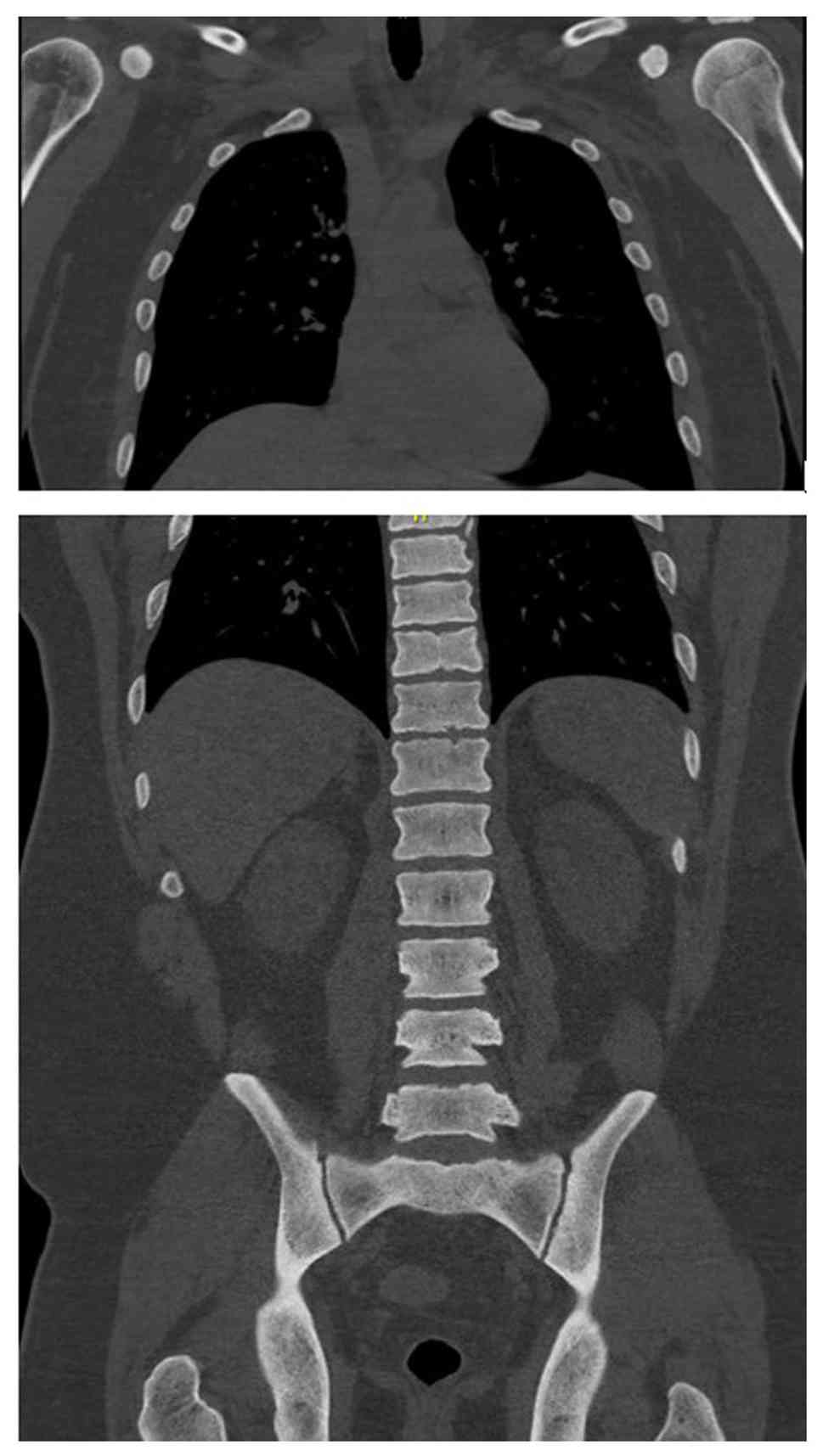

listed in Table I. Imaging analyses,

including a computed tomography scan of the cervical spine

(Fig. 2), and chest, abdomen and

pelvis (Fig. 3), revealed diffuse

bony sclerosis.

| Table ILaboratory values of the patient upon

admission. |

Table I

Laboratory values of the patient upon

admission.

| Laboratory test | Patient value | SI unit | Reference range |

|---|

| Sodium (Na) | 129.0 | mmol/l | 135-145 mmol/l |

| Chloride (Cl) | 102.0 | mmol/l | 98-106 mmol/l |

| Potassium (K) | 7.3 | mmol/l | 3.5-5.1 mmol/l |

| Bicarbonate

(HCO3) | 14.0 | mmol/l | 22-28 mmol/l |

| Phosphorus

(PO4) | 1.1 | mg/dl | 2.5-4.5 mg/dl |

| Calcium | 10.1 | mg/dl | 8.4-10.2 mg/dl |

| BUN | 45.0 | mg/dl | 7-20 mg/dl |

| Creatinine | 2.49 | mg/dl | 0.6-1.3 mg/dl |

| Anion gap | 20.0 | mmol/l | 8-16 mmol/l |

| Creatine kinase

(CK) | 361.0 | U/l | 38-174 U/l |

| Troponin | 1062.0 | ng/l | <14 ng/l |

| Pro-BNP | 416.0 | pg/ml | <125 pg/ml |

| Alkaline phosphatase

(ALP | 292.0 | U/l | 44-147 U/l |

| ALP bone

fraction | 96.0 | U/l | 28-66 U/l |

| ALP intestinal

fraction | 0.0 | U/l | 1-24 U/l |

| ALP liver

fraction | 14.0 | U/l | 25-69 U/l |

| Haptoglobin | 770.0 | mg/dl | 30-200 mg/dl |

| Lactic acid | 1.0 | mmol/l | 0.5-2.2 mmol/l |

| Vitamin D | 39.0 | ng/ml | 30-100 ng/ml |

| Hemoglobin | 12 | g/dl | 13.5-17.5 g/dl |

| Ferritin | 1255.0 | ng/ml | 20-500 ng/ml |

| Iron | 66.0 | µg/dl | 60-170 µg/dl |

| MCV | 95.0 | fl | 80-100 fl |

| Folate | 7.3 | ng/ml | 3.1-17.5 ng/ml |

| Vitamin B12 | 655.0 | pg/ml | 200-900 pg/ml |

| Platelets | 550.0 |

x103/µl |

150-400x03/µl |

| ESR | 90.0 | mm/h | 0-20 mm/h |

| INR | 1.38 | | 0.8-1.2 |

| TSH | 1.01 | µIU/ml | 0.4-4.0 µIU/ml |

| Cardio CRP | 8.4 | mg/l | <3.0 mg/l |

| Complement C3 | 200.0 | mg/dl | 90-180 |

| Complement C4 | 37.0 | mg/dl | 10-40 |

| PSA | 0.2 | ng/ml | 0-4.0 |

| PTH | 25 | pg/ml | 10-65 |

| ANA | Negative | | Negative |

| ANCA | Negative | | Negative |

| Hepatitis panel | Negative | | Negative |

| HIV | Negative | | Negative |

| UPCR | 1,269 High | | 22-128 mg/g |

| UA microscopy | 1+ blood, 2+

protein | | None |

| SPEP/UPEP with

immunofixation | No paraprotein

detected | | No paraprotein

detected |

| Serum free light

chains | Not detected | | Not detected |

| Urine drug

screen | Not detected | | Not detected |

| Serum

salicylate/acetaminophen | Not detected | | Not detected |

He was managed with intravenous fluids, a heparin

drip 10 units/kg/h for 24 h; aspirin at 325 mg, one dose;

atorvastatin at 80 mg for 2 days; a hyperkalemia protocol including

10 ml of 10% calcium gluconate, 1 dose and 10 mg nebulized

albuterol, one dose; and sodium bicarbonate infusion at 100 ml/h

for 1 day. Cardiology attributed the troponin elevation to

non-thrombotic myocardial injury (type 2 MI) rather than acute

plaque rupture, given the clinical context and normal ventricular

function on an echocardiogram. Therefore, the heparin drip was

discontinued after 24 h. The patient was monitored on telemetry and

had no arrhythmias.

Nephrology and Hematology-Oncology were consulted to

investigate potential underlying etiologies for his acute kidney

injury and diffuse skeletal sclerosis. A comprehensive differential

diagnosis was considered and methodically ruled out. Multiple

myeloma was excluded with negative serum and urine

protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and immunofixation analyses.

Renal osteodystrophy was deemed unlikely due to preserved renal

function on follow-up and lack of secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Glomerulonephritis and vasculitis were excluded via negative

serologic and urinary studies. No evidence of paraneoplastic

syndrome or infiltrative bone marrow disorder was found, and

vitamin D deficiency and prostate-specific antigen levels were

within normal range. Imaging and laboratory trends supported a

toxic-metabolic etiology, most likely secondary to chronic inhalant

exposure. The patient improved with supportive therapy, with

laboratory values returning to levels within normal limits; he was

discharged after 3 days with referrals to nephrology,

hematology-oncology and addiction medicine.

Discussion

1,1-Difluoroethane, a hydrofluorocarbon propellant

found in a number of compressed-gas cleaning products, is

frequently misused for its rapid onset of central nervous system

depression and transient euphoria. Owing to its high lipid

solubility, the compound readily crosses the blood-brain barrier,

producing effects that last only a few minutes. Its easy

availability, low cost and short-lived intoxication render

difluoroethane-containing compressed air duster cans particularly

attractive for recurrent recreational use (6). The patient described herein reported

inhaling approximately four cans daily for several months and

doubled this amount to eight cans on the day of presentation,

highlighting both tolerance and escalating exposure patterns

typical of chronic inhalant misuse.

Reported neurologic manifestations of difluoroethane

and other inhalant exposure range from mild to severe and may

include drowsiness, headaches, gait instability, dizziness, visual

disturbances, generalized weakness, profound fatigue, lethargy,

altered consciousness, seizures and even coma. Hypoxia resulting

from oxygen displacement within the alveoli or aspiration-related

lung injury can further exacerbate central nervous system

depression. Chronic users may also experience lasting effects, such

as cognitive deficits, cerebellar dysfunction and peripheral

neuropathy (7). In the case

described herein, the inhalant use of the patient culminated in a

syncopal episode, consistent with the acute neurologic and systemic

instability described in the literature (4).

Marked cardiovascular complications from hydrocarbon

inhalation include myocardial dysfunction and life-threatening

arrhythmias. Halogenated hydrocarbons, in particular, have been

shown to be associated with fatal ventricular dysrhythmias and the

phenomenon of ‘sudden sniffing death’, an unpredictable event

reported even in first-time users. This is deemed to result from

increased myocardial sensitivity to catecholamines, compounded by

inhalant-induced hypoxia, which promotes delayed

after-depolarizations and malignant ventricular arrhythmias

(8-12).

In the patient in the present study, inhalant use was accompanied

by severe hyperkalemia with corresponding electrocardiogram

changes, syncope and markedly elevated troponin levels in the

thousands, although echocardiography demonstrated preserved

systolic function without structural abnormalities.

Cao et al (3)

reported the case of a 35-year-old chronic duster user who

developed ischemic-appearing electrocardiogram changes and elevated

troponin, ultimately found to have non-obstructive coronaries on

catheterization, consistent with inhalant-related cardiac injury.

Similarly, the patient in the present study exhibited

electrocardiogram abnormalities most notably peaked T waves along

with syncope and significant troponin elevation. Similarly, in the

patient described herein, the increase in troponin levels was

ultimately deemed type 2 MI (supply-demand mismatch) or toxic

myocardial injury, rather than a classic type 1 infarction. As the

clinical suspicion for true coronary disease was low and

echocardiography was normal, cardiac catheterization was deferred.

The Fourth Universal Definition of myocardial infarction (13) emphasizes that troponin elevation

without evidence of acute atherothrombosis should be classified as

myocardial injury or type 2 MI (due to this, his heparin was

terminated and angiography was deferred). Hydrocarbon toxicity can

also cause myocarditis; cardiac MRI in such cases presents as

inflammation; however, in the patient in the present study, the

echo was normal and he had no focal wall motion abnormalities. In

summary, the clinical picture favors a toxic myocardium from

inhalants (type 2 MI) over an acute plaque rupture infarct

(13). Long et al (14) previously described one of the

earliest reported cases of acute renal failure associated with

duster inhalation. Similar to that report, the patient described

herein also presented with acute kidney injury, which improved

significantly with intravenous fluid resuscitation. Although

dehydration likely contributed to his renal dysfunction, a direct

nephrotoxic effect of difluoroethane cannot be fully excluded.

Inhalant-related skeletal fluorosis can produce

diffuse osteosclerosis, trabecular coarsening, cortical thickening

and soft-tissue ossifications, with imaging serving as the most

sensitive diagnostic tool. As fluoride accumulates in bone with a

long half-life, radiographic changes may persist for years even

after exposure stops (15). In the

patient in the present study, extensive osteosclerosis was evident

despite his young age, consistent with chronic hydrofluorocarbon

exposure, although a DEXA scan was not obtained. However, in the

present study, serum or urine fluoride levels were not measured to

confirm fluorosis; thus, this is a limitation of the present study.

Without fluoride quantification, a definitive diagnosis of skeletal

fluorosis cannot be made. Instead, toxic-metabolic bone disease

from inhalant exposure was considered more likely. The differential

diagnosis for diffuse osteosclerosis is limited, but includes

osteoblastic metastases (e.g., prostate and breast), sclerotic

myeloma, myelofibrosis, mastocytosis, Paget's disease and rare

granulomatous disorders, such as sarcoidosis. In the case described

herein, malignancy and myeloma were investigated and excluded, and

there was no evidence of systemic diseases (such as sarcoidosis)

that may cause similar bone changes.

In conclusion, the present study describes the case

of a 29-year-old male patient who developed syncope after inhaling

multiple compressed air duster cans, presenting with acute cardiac

injury, renal dysfunction and diffuse skeletal sclerosis. His

findings parallel prior reports of multisystem toxicity from

hydrofluorocarbon inhalation (3,5,6,14,15).

Although the current evaluation was limited by the absence of

cardiac catheterization and DEXA imaging, the clinical picture

strongly supports inhalant-induced organ injury. Clinicians should

consider duster abuse in young patients with unexplained syncope,

electrocardiogram abnormalities, or multiorgan dysfunction. Ongoing

research is required in order to better define the pathophysiology

and long-term effects of these increasingly common exposures.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PA identified and managed the case, collected

clinical data, performed the literature review, and drafted the

manuscript. SI and MA assisted with the literature review, were

involved in the conception of the study, and assisted in preparing

the figures/table. NN assisted with the literature review and was

involved in the design of the study. SM and MS critically revised

the manuscript for important intellectual content and were also

involved in the design of the study. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript. PA and MS confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent for participation was

obtained from the patient.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present case report and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

NIDA. Inhalants. National Institute on

Drug Abuse website. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/inhalants.

Accessed January 10, 2026.

|

|

2

|

Levari E, Stefani M, Ferrucci R, Negri A

and Corazza O: The dangerous use of inhalants among teens: A case

report. Emerg Trends Drugs Addict Health. 1(100006)2021.

|

|

3

|

Cao SA, Ray M and Klebanov N: Air duster

inhalant abuse causing non-ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Cureus. 12(e8402)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Romero J, Abboud R, Elkattawy S, Romero A,

Elkattawy O, Samak AAA and Shamoon R: Troponemia secondary to air

duster inhalant abuse. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med.

9(003556)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. High School Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United

States 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/index.html. Accessed October

8, 2026.

|

|

6

|

Mohideen H, Dahiya DS, Parsons D, Hussain

H and Ahmed RS: Skeletal fluorosis: A case of inhalant abuse

leading to a diagnosis of colon cancer. J Investig Med High Impact

Case Rep: Mar 28, 2022 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

7

|

Hoody L, Cronin M and Balasanova AA: A

case of multisystem organ failure in a patient with inhalant use

disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord.

25(22cr03349)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tormoehlen LM, Tekulve KJ and Nañagas KA:

Hydrocarbon toxicity: A review. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 52:479–489.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Adgey AA, Johnston PW and McMechan S:

Sudden cardiac death and substance abuse. Resuscitation.

29:219–221. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Shepherd RT: Mechanism of sudden death

associated with volatile substance abuse. Hum Toxicol. 8:287–291.

1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Nelson LS: Toxicologic myocardial

sensitization. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 40:867–879. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Mullin LS, Azar A, Reinhardt CF, Smith PE

Jr and Fabryka EF: Halogenated hydrocarbon-induced cardiac

arrhythmias associated with release of endogenous epinephrine. Am

Ind Hyg Assoc J. 33:389–396. 1972.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman

BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA and White HD: ESC Scientific Document Group.

Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur

Heart J. 40:237–269. 2019.

|

|

14

|

Long D, Zhu D and Arnouk S: A case of

Ultra Duster intoxication causing acute renal failure. Chest.

144(290A)2013.

|

|

15

|

Suwak P, Van Dyke JC, Robin KJ, Leonovicz

OG and Cable MG: Rare case of diffuse skeletal fluorosis due to

inhalant abuse of difluoroethane. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res

Rev: Oct 12, 2021 (Epub ahead of print).

|