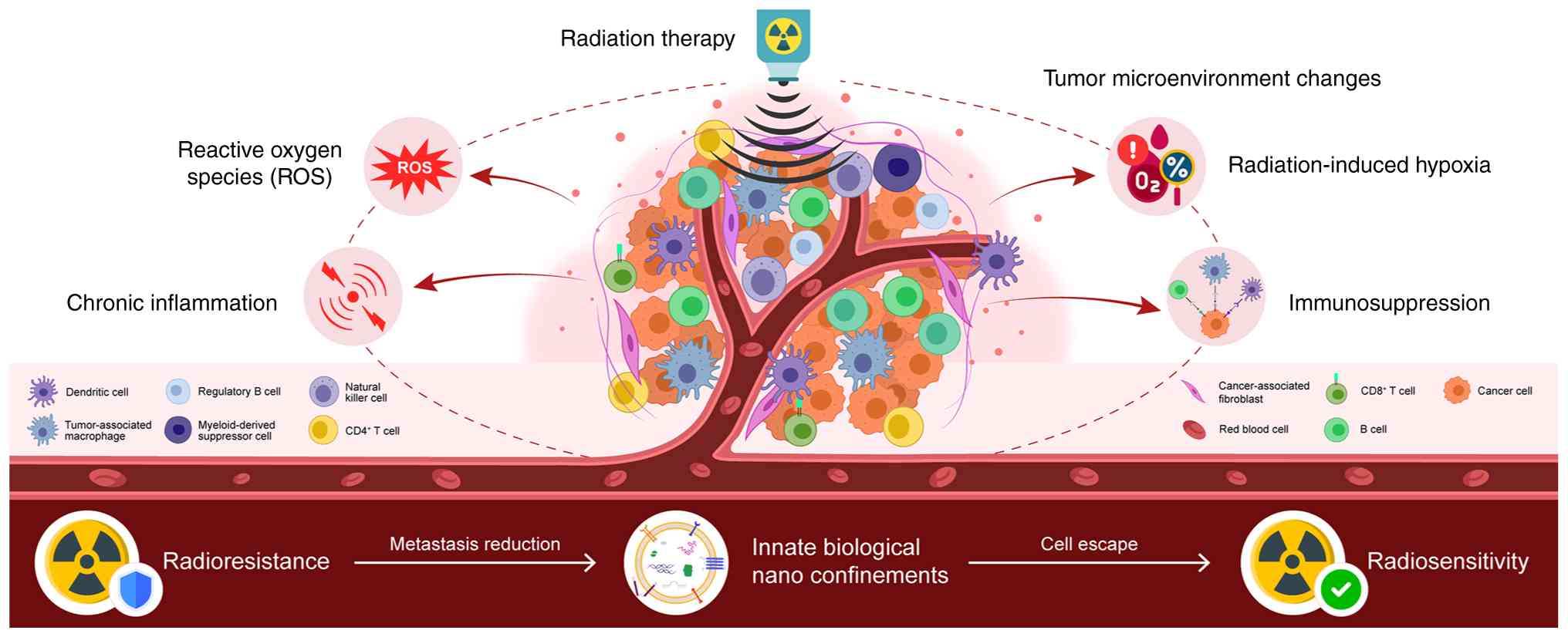

Radiation therapy is a common cancer treatment;

however, radioresistance may result in treatment failure (1). Cancer cells can alter their metabolic

status following radiation therapy to reduce the cytotoxic effects,

thereby diminishing the treatment efficacy (2). The tumor microenvironment (TME) is

defined as the cellular and non-cellular components surrounding

tumor cells. This includes immune cells and stromal material. As

recently reported, altered tumor metabolism influences the TME, and

alterations in the metabolite composition of the TME can support

tumor growth (3,4). Therefore, targeting tumor metabolism in

combination with radiotherapy may enhance the efficacy of cancer

treatment (5). The present review

discusses the metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells following

radiation exposure and summarizes the findings involving the TME to

illustrate the metabolic characteristics of radiotherapy.

Furthermore, the present review introduces novel findings on innate

nanobiological confinements that may influence the TME via novel

mechanisms regulating energy metabolism and signaling pathways

(Fig. 1).

For the present review, ‘Boolean Operators’ such as

AND, OR and NOT were used to search for relevant research

articles/reviews published over the past two decades from the

PubMed database and Clinical Trials website (https://ClinicalTrials.gov) for cancer

microenvironment alterations induced by radiation. Thereafter, only

the articles/reviews containing both ‘cancer microenvironment

alterations’ and ‘radiation/radiotherapy’ were filtered into the

investigational pool.

Radiotherapy is a widely used cancer treatment, with

almost half of cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. It is

usually administered over a period of days or weeks in a targeted,

sub-dose manner, primarily eliminating cancer cells due to DNA

injury through the over expressed reactive oxygen species (ROS)

(6). Radiotherapy can serve as an

adjuvant therapeutic model following radical cancer surgery, or it

can serve as a neoadjuvant therapy for advanced-stage cancer. Its

combination with chemotherapy can enhance the anticancer effect

(7). A number of experimental and

clinical studies have explored its combination with immunotherapy

(8-10);

in addition, investigations are continuing on this matter (Clinical

trial no. NCT02223923). Despite considerable positive progress over

the past decades, radiation resistance remains a key challenge in

the treatment of cancer. The key to overcoming this issue may lie

in targeting the TME, specifically the variety of non-malignant

cells surrounding cancer cells. Radiation therapy alters the TME,

potentially triggering interactions among its components that

contribute to radiotherapy resistance. Therefore, a more in-depth

exploration of TME interaction mechanisms may be critical, as it

may identify mechanisms which can be used to enhance the

therapeutic efficacy of radiotherapy.

Radiation-induced vascular damage, hypoxia and

chronic inflammation in the TME may promote cancer cell survival

and radioresistance (11). Due to

endothelial damage, vascular damage and hypoxia also occur,

possibly owing to the reduced oxygen consumption in irradiated

cells and the survival of certain blood vessels that maintain the

oxygen and nutrients to supply to the tumor continuously (12,13). The

immune clearance of cancer cells following radiotherapy is crucial

for tumor control (14), as the

antitumor immune response can be activated by radiation-induced DNA

damage and in turn, this increases antigen release from cancer

cells (15). However, the

co-existence of hypoxia and high levels of ROS can create a chronic

inflammatory state, in which CD8+ T-cells,

CD4+ T-cells, natural killer and dendritic cells are

suppressed, resulting in the low efficacy of tumor elimination

(16). As an additional

tumor-promoting condition, the higher numbers of regulatory T-cells

(Tregs) and bone marrow-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) ultimately

lead to an immunosuppressive environment.

Cell metabolism is critical for the TME, and

metabolic dysregulation can support cancer cell growth and

therapeutic resistance, both hallmark features of cancer (17). Metabolites and cytokines secreted by

cancer cells can reprogram the metabolism of other TME components,

thereby altering its composition and promoting tumor growth

(18). This metabolic reprogramming

forms a symbiotic association, enabling the exchange of metabolites

to meet the needs of different cell types for metabolic within the

TME. These interactions provide a potential avenue for targeted

cancer treatment without disrupting normal cellular functions.

Therefore, studying metabolic changes in the TME in response to

radiation is essential for developing novel therapeutic

strategies.

Cellular ROS can lead to DNA damage and the

destruction of cellular structures, including cell membranes and

blood vessels, resulting in transient hypoxia and nutrient

deprivation in cancer cells, while simultaneously increasing

antitumor immune cell activity in the TME (19,20).

Cancer cells reprogram their metabolic state to counteract

radiation-induced damage (21). The

metabolic changes that promote cancer survival under radiotherapy

may involve four main features: First, radiation can enhance the

express efficiency of glycolysis pathway (GLP) and the pentose

phosphate pathway (PPP), which are highly associated with

glycolytic adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis, nucleotide

biosynthesis, membrane phospholipid synthesis, and nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) regeneration to support

antioxidant responses (22). Second,

elevated ROS can activate novel lethal pathways, for example,

neoplastic iron death (23).

Furthermore, damaged DNA and cell membranes require metabolic

support to facilitate repair processes (24). Finally, cancer-TME metabolic

interactions can lead to the insufficient supply of nutrients to

the tumor by disrupting local blood vessels (25). The nutrients provided by the

surrounding matrix thus become a crucial driving force for cancer

cell metabolism (18).

In the long-term, the efficacy of radiotherapy is

affected by the biological characteristics of the tumor, such as

inherent radioresistance, pathological hypoxia and the consequent

complexity of the TME. Consequently, the more active biological

pathways in cancer cells have been considered potential therapeutic

targets. Antibodies and small-molecule inhibitors targeting

glycolysis and the PPP have further been demonstrated in

preclinical studies with promising results (26-28).

The comprehensive treatment regimen of cetuximab and

radiotherapy has been approved by the FDA (29), whereas therapies such as small

molecular drugs (erlotinib/lapatinib) are still in the stages of

clinical trials (30,31). Cetuximab and panitumumab are

classical anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibodies,

which were widely used in the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Through an autocrine and paracrine manner, EGFR is activated by

members from the EGF family. By combining with these EGFs, EGFR

dimers and downstream signaling pathways (KRAS-BRAF-MEK-ERK, PI3K,

AKT and STAT) are activated efficiently. As regards the EGFR, its

tyrosine phosphorylation level has been demonstrated to be

upregulated in growth-restricted squamous cells (32) and breast cancer cells (33). Furthermore, EGFR signaling enhances

the expression of hexokinase II (HKII), while inhibiting the

expression of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2(34). Radiation can further activate the

hypoxia-inducing factor 1α subunit, resulting in the increased

transcription of several hypoxia-related genes, such as glucose

transporter 1 (GLUT1) and lactate dehydrogenase A (35). This upregulation increases glycolysis

throughput in glioblastoma (GBM), potentially providing a survival

advantage following radiotherapy. Several preclinical trials have

explored the combination of radiotherapy with 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG)

to counteract this metabolic adaptation (36-38).

The PPP mainly provides NADPH for reducing glutathione (GSH) and

nucleotides for DNA synthesis (39).

This pathway is rapidly upregulated to response to DNA damage,

which is caused by oxidative stress and radiation exposure. The

GLUT1 receptor also regulates the hexokinase-1 (HKI) and pyruvate

kinase (PK) expression level under the stimulation of EGF. HKII has

been observed to be overexpressed in various types of cancer cells

(40). In the cytoplasm, the

voltage-dependent anion channel protein on the mitochondrial

membrane has been observed to be specifically bind with HKII to

resist glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) concentration-dependent feedback

inhibition, owing to the high maintenance of G-6-P concentrations

in cancer cells following radiation (41). As a biosynthetic substrate, G-6-P

links glycolysis to the PPP, providing a rationale for the use of

PPP inhibitors in combination with radiotherapy (22). The nicotinamide analog,

6-aminonicotinamide (6-AN), has been shown to inhibit G6PD activity

and enhance sensitivity to radiation (42). The combination of radiotherapy with

2-DG and 6-AN considerably improves the efficacy of radiotherapy.

Genes involved in the regulation of glycolysis are contributors to

cancer cell survival. Radiation exposure can activate HIF1, and

increase glycolysis and the level of antioxidants (5). The upregulation of EGF signaling

induced by radiation may lead to the accumulation of glycolytic

intermediates in cancer cells (43).

During glycolysis, G-6-P can be shunted into the PPP, where the

ribonucleotides produced are essential for post-radiation DNA

repair (44).

High energy generated by ionizing radiation drives

the formation of ROS through the chemical and physical interaction

between ions and cellular components, which mainly includes

bioactive hydrogen peroxide (H2O2),

superoxide anion (O2-) and hydroxyl radical

(OH-). Persistent high levels of ROS lead to oxidative

stress, which may influence the structural and functional state of

DNA, cell or intra-cell membranes, proteins, and so on, ultimately

triggering cell death. Although increase levels of ROS may promote

cancer growth and progress, excessively high levels of ROS can have

anticancer effects (6).

An adaptive change in redox metabolism can be

induced by radiation-induced oxidative stress in cancer cells

(45,46), and the potential association between

radiation and consequently enhanced antioxidant metabolism has been

confirmed in previous studies (47,48). The

NRF2-mediated antioxidant responses activated by ionizing radiation

has been well demonstrated in breast cancer cells (49). Additionally, the analysis of the

blood of patients with cancer receiving radiation therapy has

revealed reduced levels of the antioxidant, GSH (50), whereas genome-wide metabolic models

from The Cancer Genome Atlas have indicated the antioxidant NADPH

with an increased synthesis rate in radioresistant cancer cells

(51).

Radiotherapy, by its ion beams, directly attacks and

injures the structures of cellular macromolecular and organelles,

which in turn stimulates cancer cells to activate its adaptive

repair pathways through macromolecular response, many of which

depend on cellular metabolism (5,52,53). The

primary anticancer mechanism of radiotherapy is that radiation can

induce different types of lethal damage on DNA. However, the high

genomic instability of cancer cells reduces radiation-induced DNA

damage before it reaches toxic levels (44). Therefore, an effective DNA damage

response is partially determined by the innate radioresistance of

cancer cells; further studies are required to focus on how to

effectively increase the radiosensitivity of cancer cells when

facing different types of radiation by targeting DNA repair

pathways (54-56).

DNA repair relies on the rich nucleotide pool supported by the

active metabolism. These pools afford the essential demands for

chromatin modifications and protein activation (57-59).

For single- and double-strand DNA breaks, purine and

pyrimidine nucleotide pools are necessary and essential. In fact,

experimental studies have demonstrated that an increased nucleotide

synthesis rate and more active pathways related to these processes

are closely associated with the radioresistance of cancer cells

(60,61). Notably, nucleotide metabolism

presents context-dependent characteristics in different types of

cancer following radiotherapy. The inhibition of GMP resynthesis

with mycophenolate mofetil has also been shown to radiosensitize

GBMs (62). Glutamine is a precursor

for de novo nucleotide synthesis; a previous in vitro

and in vivo study demonstrated delayed DNA repair and

enhanced radiosensitivity in cancer models followign the knockdown

of glutamine synthesis (63). Other

pathways involved in nucleotide synthesis in cancer cells include

the PPP ribo5-phosphate (R5P) and serine-glycine metabolism during

the post-radiation. The involvement of these pathways in promoting

radioresistance through DNA repair warrants further investigation

(64). Histone methylation and

acetylation patterns can regulate DNA repair conditionally

(65), although the mechanisms

involved remain unclear (66). ATP

is associated with protein phosphorylation and the activation of

proteins involved in DNA repair (67). Notably, in hepatoma cells,

combination therapy with metformin and radiation has been shown to

reduce ATP levels in cancer cells and decreases DNA repair

capacity, thereby enhancing radiosensitivity (68).

Fatty acids constitute the cornerstone of cell

membranes. They are the base of repair on damage induced by

radiation. Cells meet their metabolic lipid requirements through

de novo biosynthesis and uptake from the microenvironment

(69). Fatty acid synthase (FASN), a

key enzyme among de novo palmitate synthase, is associated

with cancer radioresistance (70).

FASN overexpression is associated with the cancer cell

radioresistance, whereas the inhibition of FASN enhances the

anticancer effects of radiation (71); however, the precise mechanisms

involved remain to be elucidated. FASN may increase intracellular

palmitate levels and regulate the expression of PARP1 through the

NF-κB pathway (72), thereby

supporting radiation resistance through NF-κB-mediated signaling

(73).

The dysregulation of cholesterol synthesis is also

linked to cellular radioresistance. Cholesterol plays a crucial

role in organizing the cell membrane and forming the vascular

system, both of them benefit cancer cells following radiation

exposure (74). Zoledronic acid, an

inhibitor of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, sensitizes

radiation-resistant pancreatic cancer lines. Conversely, the

inhibition of cholesterol synthesis is reportedly associated with

the increased survival of patients with lung cancer undergoing

radiotherapy (75). These converse

results emphasize the functional and environmental specific changes

in lipid metabolism that mediate radiation resistance. Apart from

the inherent metabolic heterogeneity of cancer cells, the role of

lipid metabolism may be determined by the availability of different

lipids in the TME following radiotherapy.

The complexity of the metabolism of TME components

can influence cell-cell interactions, and can even alter the

outcomes of diseases. Therefore, understanding the metabolic status

of the TME following radiotherapy is essential.

Metabolites provided by the extracellular matrix can

promote cancer recovery following radiotherapy (76). In the TME, metabolic productions of

larger amounts of non-malignant cells can also promote cancer cell

growth in environments that lack nutrients (77). Glutamine from cancer-associated

fibroblasts (CAFs) and serine from neurons in the TME can enhance

cancer metabolism by supplying ribose-1-phosphate, thereby

improving the DNA repair capacity after radiation exposure

(78). The TME can also provide

lipids to cancer cells, supporting their survival following

radiotherapy (79). CAFs have been

demonstrated to promote pancreatic and colorectal cancers

progression via lipid and branched-chain ketoacid supply (80). Cancer cells can also induce adipocyte

fat breakdown, resulting in releasing the fatty acids into the TME.

The hypoxic state following radiation therapy reduces lipid

synthesis pathways, increasing cancer cell dependence on exogenous

lipid uptake (81). Hypoxia induces

the expression of HIF, which can facilitate the cancer cells

enriching fatty acids, thereby protecting them from

radiation-induced ROS (82). Hypoxia

also promotes cancer cells to adsorb unsaturated fatty acids by

activating serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), whereas

the inhibition of SGK1 can enhance the effects of radiotherapy

(83). Radiation exposure increases

intercellular ROS levels in cancers, and substantial ROS levels in

the TME are associated with precancerous lesions (45). Through the stabilization of HIF-1α by

ROS and the promotion of angiogenesis, the survival of cancer cells

is enhanced under radiotherapy. ROS can also promote the activation

of CAFs (84,85).

During the post-radiation time, changes in metabolic

factors may reprogram the immune activity in the TME, such as the

increased production of ROS which can inhibit immune cells

(5,52). ROS can affect the phenotype of

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), promoting a change into a

protumor state; ROS can also lead to the recruitment of more Tregs

and MDSCs at tumor sites, suppress T-cell activity, and reduce the

number of natural killer cells in the TME (86). With elevated levels of lipids in the

TME, immune cell function may be altered. For example, excess free

fatty acids can lead to lipid accumulation in natural killer cells,

thereby reducing their immune capacity. In addition, metabolic

interactions between effector T-cells, cancer cells and Tregs can

increase lipid accumulation, inducing cellular senescence (69). Effector T-cells and, tumor-promoting

Tregs/TAMs have very different energy demands, namely aerobic

glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation, respectively. Systemic

radiation can lead to lipid accumulation and dysfunction in

dendritic cells, thereby inducing a dysfunction in the immune

response, which is linked to carcinogenesis (87). As previously mentioned, the

extracellular matrix may secrete lipids, and obesity may contribute

to elevated lipid levels in the TME (79,80).

Increased glycolytic activity following radiation leads to lactate

accumulation and TME acidification. High lactate levels inhibit

effector T-cell function, promote macrophage differentiation into

the immunosuppressed M2 phenotype, and alter monocyte secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, even though radiation can

promote immune cell with higher capacity, metabolic reorganization

in cancer cells may contribute to an immunosuppressive

environment.

Tumors are commonly considered as dependent

pseudo-organs. In these pseudo-organs, there is a complex

interaction between cancer cells and various non-tumor cells,

forming a complex network. In this network, cancer cells strive to

maintain their malignant proliferation by altering their metabolic

properties continuously (88). As is

commonly known, cancer cells exhibit an upregulated glycolysis and

downregulated oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). However, in a

previous study, OXPHOS was reported to be upregulated, even

occurring concurrently with a high level of glycolysis (89).

Cancer cells have a high heterogeneity as regards

the metabolic phenotype. In cancer cells, some substances, such as

glucose, lactate, pyruvate and hydroxybutyrate have a higher

metabolic rate than in normal cells, contributing to the complex

tumor metabolic ecology. This metabolic heterogeneity and

complexity help cancer cells to maintain a dominant position in

energy acquisition, whether they utilize ATP, maintain redox

balance, or establish metabolic coupling with any other cells

(90). Regardless, acquiring energy

and essential substances for anabolism determine the fate of any

type of cells. Within the same biological system, different cell

types compete for energy demands through specific mechanisms. Only

those cells that prioritize energy utilization can develop

preferentially. The following paragraph discusses innate biological

nano-confinements (iBNCs). iBNCs are a proposed concept referring

to any naturally occurring structural and functional nanodomains

within biological systems.

Nano-confinement refers to the restriction of

materials within nanoscale regions. When certain materials, such as

some bioactive molecules (such as protein, DNA and RNA) are

confined at the nanoscale, they may exhibit a unique behavior

distinct from that observed at the macroscale (91). Furthermore, the nano-confinement

approach provides a basis for the development of novel cancer

therapeutic strategies related to energy and substance utilization

(92,93). It is considered that biological

nano-confinements widely exist within biological systems, referred

to as iBNCs, which play critical roles in tumorigenesis,

progression and metastasis via novel mechansisms (94). For instance, CAR-T therapy has

exhibited promising outcomes in hematological malignancies.

However, in the majority of solid tumors, such as liver, gastric

and lung cancer, its effects are limited (95). The higher fluidity of hematological

malignancies does not provide a stable environment of the formation

and maintenance of iBNCs; therefore, these malignancies often

develop resistance to therapeutic interventions, such as

chemotherapies and radiotherapies. However, as solid tumors have a

relatively stable physical environment, iBNCs can easily be formed.

They have the additional capacity to resist drugs/radiation, and

ultimately survive from intervention strategies (94).

Cancer cells can alter and reprogram their metabolic

profile in response to the cellular damage induced by radiation.

The TME plays a crucial role by supplying precursor substances that

support cancer metabolism alterations, presenting potential targets

for therapeutic intervention. A key consideration is that iBNCs may

help to elucidate the prioritization of energy and substance

utilization by cancer cells in solid tumors in hypoxic and

nutrition-deprived environments. This may provide further insight

into the reason why CAR-T therapies are more effective for

hematological cancers than solid tumors, and could explain the

synergetic enhancement observed when CAR-T therapy is used in

combination with chemotherapy. Further studies are required to

focus on validating the therapeutic potential of targeting

radiation-induced metabolic reprogramming through preclinical and

clinical research, with an emphasis on tumor-type-specific

metabolic responses.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

All authors (HL, XZ, ZH and JY) were involved the

collection and interpretation of data from the literature, and in

the writing and preparation of the draft of the manuscript. JY

conceived and designed the study, and provided the critical

revision of the article content. All authors have read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Otsuki Y, Yamasaki J, Suina K, Okazaki S,

Koike N, Saya H and Nagano O: Vasodilator oxyfedrine inhibits

aldehyde metabolism and thereby sensitizes cancer cells to

xCT-targeted therapy. Cancer Sci. 111:127–136. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Dandachi D and Morón F: Effects of HIV on

the tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1263:45–54.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lin J, Liu Y, Liu P, Qi W, Liu J, He X,

Liu Q, Liu Z, Yin J, Lin J, et al: SNHG17 alters anaerobic

glycolysis by resetting phosphorylation modification of PGK1 to

foster pro-tumor macrophage formation in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42(339)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Mittal A, Nenwani M, Sarangi I, Achreja A,

Lawrence TS and Nagrath D: Radiotherapy-induced metabolic hallmarks

in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cancer. 8:855–869.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Jia C, Wang Q, Yao X and Yang J: The role

of DNA damage induced by low/high dose ionizing radiation in cell

carcinogenesis. Explor Res Hypothesis Med. 6:177–184. 2021.

|

|

7

|

Tang B, Zhu J, Shi Y, Wang Y, Zhang X,

Chen B, Fang S, Yang Y, Zheng L, Qiu R, et al: Tumor cell-intrinsic

MELK enhanced CCL2-dependent immunosuppression to exacerbate

hepatocarcinogenesis and confer resistance of HCC to radiotherapy.

Mol Cancer. 23(137)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lin X, Liu Z, Dong X, Wang K, Sun Y, Zhang

H, Wang F, Chen Y, Ling J, Guo Y, et al: Radiotherapy enhances the

anti-tumor effect of CAR-NK cells for hepatocellular carcinoma. J

Transl Med. 22(929)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Dillon MT, Boylan Z, Smith D, Guevara J,

Mohammed K, Peckitt C, Saunders M, Banerji U, Clack G, Smith SA, et

al: PATRIOT: A phase I study to assess the tolerability, safety and

biological effects of a specific ataxia telangiectasia and

Rad3-related (ATR) inhibitor (AZD6738) as a single agent and in

combination with palliative radiation therapy in patients with

solid tumours. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 12:16–20. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dillon MT, Guevara J, Mohammed K, Patin

EC, Smith SA, Dean E, Jones GN, Willis SE, Petrone M, Silva C, et

al: Durable responses to ATR inhibition with ceralasertib in tumors

with genomic defects and high inflammation. J Clin Invest.

134(e175369)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kameni LE, Januszyk M, Berry CE, Downer MA

Jr, Parker JB, Morgan AG, Valencia C, Griffin M, Li DJ, Liang NE,

et al: A review of radiation-induced vascular injury and clinical

impact. Ann Plast Surg. 92:181–185. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Choi SH, Hong ZY, Nam JK, Lee HJ, Jang J,

Yoo RJ, Lee YJ, Lee CY, Kim KH, Park S, et al: A hypoxia-induced

vascular endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in development of

radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Cancer Res.

21:3716–3726. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wijerathne H, Langston JC, Yang Q, Sun S,

Miyamoto C, Kilpatrick LE and Kiani MF: Mechanisms of

radiation-induced endothelium damage: Emerging models and

technologies. Radiother Oncol. 158:21–32. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Guilbaud E, Naulin F, Meziani L, Deutsch E

and Galluzzi L: Impact of radiation therapy on the immunological

tumor microenvironment. Cell Chem Biol. 32:678–693. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lee AK, Pan D, Bao X, Hu M, Li F and Li

CY: Endogenous retrovirus activation as a key mechanism of

anti-tumor immune response in radiotherapy. Radiat Res.

193:305–317. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chen Z, Han F, Du Y, Shi H and Zhou W:

Hypoxic microenvironment in cancer: Molecular mechanisms and

therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

8(70)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jiang W, Jin WL and Xu AM: Cholesterol

metabolism in tumor microenvironment: Cancer hallmarks and

therapeutic opportunities. Int J Biol Sci. 20:2044–2071.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Li YJ, Zhang C, Martincuks A, Herrmann A

and Yu H: STAT proteins in cancer: Orchestration of metabolism. Nat

Rev Cancer. 23:115–134. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Renaudin X: Reactive oxygen species and

DNA damage response in cancer. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 364:139–161.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

An X, Yu W, Liu J, Tang D, Yang L and Chen

X: Oxidative cell death in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic

opportunities. Cell Death Dis. 15(556)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Punnasseril JMJ, Auwal A, Gopalan V, Lam

AK and Islam F: Metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells and

therapeutics targeting cancer metabolism. Cancer Med.

14(e71244)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Shimoni-Sebag A, Abramovich I, Agranovich

B, Massri R, Stossel C, Atias D, Raites-Gurevich M, Yizhak K, Golan

T, Gottlieb E and Lawrence YR: A metabolic switch to the

pentose-phosphate pathway induces radiation resistance in

pancreatic cancer. Radiother Oncol. 202(110606)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zhang H, Ma J, Hou C, Luo X, Zhu S, Peng

Y, Peng C, Li P, Meng H, Xia Y, et al: A ROS-mediated

oxidation-O-GlcNAcylation cascade governs ferroptosis. Nat Cell

Biol. 27:1288–1300. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Chen H, Zhang C, Fu Y, Li L, Qiao X, Zhang

S, Luo H, Chen S, Liu X and Zhong Q: Repair of damaged lysosomes by

TECPR1-mediated membrane tubulation during energy crisis. Cell Res.

36:51–71. 2026.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Cognet G and Muir A: Identifying metabolic

limitations in the tumor microenvironment. Sci Adv.

10(eadq7305)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cutshaw G, Joshi N, Wen X, Quam E,

Bogatcheva G, Hassan N, Uthaman S, Waite J, Sarkar S, Singh B and

Bardhan R: Metabolic response to small molecule therapy in

colorectal cancer tracked with Raman spectroscopy and metabolomics.

Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 63(e202410919)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sørensen DM, Büll C, Madsen TD,

Lira-Navarrete E, Clausen TM, Clark AE, Garretson AF, Karlsson R,

Pijnenborg JFA, Yin X, et al: Identification of global inhibitors

of cellular glycosylation. Nat Commun. 14(948)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Li S, McCraw AJ, Gardner RA, Spencer DIR,

Karagiannis SN and Wagner GK: Glycoengineering of therapeutic

antibodies with small molecule inhibitors. Antibodies (Basel).

10(44)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Yamamoto VN, Thylur DS, Bauschard M,

Schmale I and Sinha UK: Overcoming radioresistance in head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 63:44–51. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Stone HB, Bernhard EJ, Coleman CN, Deye J,

Capala J, Mitchell JB and Brown JM: Preclinical data on efficacy of

10 drug-radiation combinations: Evaluations, concerns, and

recommendations. Transl Oncol. 9:46–56. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Lubet RA, Kumar A, Fox JT, You M, Mohammed

A, Juliana MM and Grubbs CJ: Efficacy of EGFR inhibitors and NSAIDs

against basal bladder cancers in a rat model: Daily vs weekly

dosing, combining EGFR inhibitors with naproxen, and effects on RNA

expression. Bladder Cancer. 7:335–345. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Beizaei K, Gleißner L, Hoffer K, Bußmann

L, Vu AT, Steinmeister L, Laban S, Möckelmann N, Münscher A,

Petersen C, et al: Receptor tyrosine kinase MET as potential target

of multi-kinase inhibitor and radiosensitizer sorafenib in HNSCC.

Head Neck. 41:208–215. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yan Y, Hein AL, Greer PM, Wang Z, Kolb RH,

Batra SK and Cowan KH: A novel function of HER2/Neu in the

activation of G2/M checkpoint in response to γ-irradiation.

Oncogene. 34:2215–2226. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Liu Z, Ning F, Cai Y, Sheng H, Zheng R,

Yin X, Lu Z, Su L, Chen X, Zeng C, et al: The EGFR-P38 MAPK axis

up-regulates PD-L1 through miR-675-5p and down-regulates HLA-ABC

via hexokinase-2 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 41:62–78. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhang Y, Wang J and Li Z: Association of

HIF1-α gene polymorphisms with advanced non-small cell lung cancer

prognosis in patients receiving radiation therapy. Aging (Albany

NY). 13:6849–6865. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Shah SS, Rodriguez GA, Musick A, Walters

WM, de Cordoba N, Barbarite E, Marlow MM, Marples B, Prince JS,

Komotar RJ, et al: Targeting glioblastoma stem cells with

2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) potentiates radiation-induced unfolded

protein response (UPR). Cancers (Basel). 11(159)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Nile DL, Rae C, Walker DJ, Waddington JC,

Vincent I, Burgess K, Gaze MN, Mairs RJ and Chalmers AJ: Inhibition

of glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration promotes

radiosensitisation of neuroblastoma and glioma cells. Cancer Metab.

9(24)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Singh D, Banerji AK, Dwarakanath BS,

Tripathi RP, Gupta JP, Mathew TL, Ravindranath T and Jain V:

Optimizing cancer radiotherapy with 2-deoxy-d-glucose dose

escalation studies in patients with glioblastoma multiforme.

Strahlenther Onkol. 181:507–514. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

TeSlaa T, Ralser M, Fan J and Rabinowitz

JD: The pentose phosphate pathway in health and disease. Nat Metab.

5:1275–1289. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yadav D, Yadav A, Bhattacharya S, Dagar A,

Kumar V and Rani R: GLUT and HK: Two primary and essential key

players in tumor glycolysis. Semin Cancer Biol. 100:17–27.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Xie Y, Liu X, Xie D, Zhang W, Zhao H, Guan

H and Zhou PK: Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 mediates

mitochondrial fission and glucose metabolic reprogramming in

response to ionizing radiation. Sci Total Environ.

946(174246)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Li M, Dong Y, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Dai Y and

Zhang B: Engineering hypoxia-responsive 6-aminonicotinamide

prodrugs for on-demand NADPH depletion and redox manipulation. J

Mater Chem B. 12:8067–8075. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yang L, Lu P, Yang X, Li K, Chen X, Zhou Y

and Qu S: Downregulation of annexin A3 promotes ionizing

radiation-induced EGFR activation and nuclear translocation and

confers radioresistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Exp Cell Res.

418(113292)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Huang R and Zhou PK: DNA damage repair:

Historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical

translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 6(254)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Farhood B, Ashrafizadeh M, Khodamoradi E,

Hoseini-Ghahfarokhi M, Afrashi S, Musa AE and Najafi M: Targeting

of cellular redox metabolism for mitigation of radiation injury.

Life Sci. 250(117570)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zheng Z, Su J, Bao X, Wang H, Bian C, Zhao

Q and Jiang X: Mechanisms and applications of radiation-induced

oxidative stress in regulating cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol.

14(1247268)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Alonso-González C, González A,

Martínez-Campa C, Menéndez-Menéndez J, Gómez-Arozamena J,

García-Vidal A and Cos S: Melatonin enhancement of the

radiosensitivity of human breast cancer cells is associated with

the modulation of proteins involved in estrogen biosynthesis.

Cancer Lett. 370:145–152. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Giallourou NS, Rowland IR, Rothwell SD,

Packham G, Commane DM and Swann JR: Metabolic targets of watercress

and PEITC in MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells explain differential

sensitisation responses to ionising radiation. Eur J Nutr.

58:2377–2391. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Qin S, He X, Lin H, Schulte BA, Zhao M,

Tew KD and Wang GY: Nrf2 inhibition sensitizes breast cancer stem

cells to ionizing radiation via suppressing DNA repair. Free Radic

Biol Med. 169:238–247. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Derindağ G, Akgül HM, Kızıltunç A, Özkan

Hİ, Kızıltunç Özmen H and Akgül N: Evaluation of saliva

glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, and malondialdehyde levels in

head-neck radiotherapy patients. Turk J Med Sci. 51:644–649.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Lewis JE, Forshaw TE, Boothman DA, Furdui

CM and Kemp ML: Personalized genome-scale metabolic models identify

targets of redox metabolism in radiation-resistant tumors. Cell

Syst. 12:68–81.e11. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Guo S, Yao Y, Tang Y, Xin Z, Wu D, Ni C,

Huang J, Wei Q and Zhang T: Radiation-induced tumor immune

microenvironments and potential targets for combination therapy.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8(205)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Read GH, Bailleul J, Vlashi E and

Kesarwala AH: Metabolic response to radiation therapy in cancer.

Mol Carcinog. 61:200–224. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Wang M, Chen S and Ao D: Targeting DNA

repair pathway in cancer: Mechanisms and clinical application.

MedComm (2020). 2:654–691. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wu Y, Song Y, Wang R and Wang T: Molecular

mechanisms of tumor resistance to radiotherapy. Mol Cancer.

22(96)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lin J, Song T, Li C and Mao W: GSK-3β in

DNA repair, apoptosis, and resistance of chemotherapy, radiotherapy

of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res.

1867(118659)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Sobanski T, Rose M, Suraweera A, O'Byrne

K, Richard DJ and Bolderson E: Cell metabolism and DNA repair

pathways: implications for cancer therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9(633305)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Zheng Y, Li H, Bo X and Chen H: Ionizing

radiation damage and repair from 3D-genomic perspective. Trends

Genet. 39:1–4. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Bamodu OA, Chang HL, Ong JR, Lee WH, Yeh

CT and Tsai JT: Elevated PDK1 expression drives PI3K/AKT/MTOR

signaling promotes radiation-resistant and dedifferentiated

phenotype of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cells. 9(746)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Morillo-Huesca M, G López-Cepero I,

Conesa-Bakkali R, Tomé M, Watts C, Huertas P, Moreno-Bueno G, Durán

RV and Martínez-Fábregas J: Radiotherapy resistance driven by

asparagine endopeptidase through ATR pathway modulation in breast

cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 44(74)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Meng W, Palmer JD, Siedow M, Haque SJ and

Chakravarti A: Overcoming radiation resistance in gliomas by

targeting metabolism and DNA repair pathways. Int J Mol Sci.

23(2246)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Benjanuwattra J, Chaiyawat P, Pruksakorn D

and Koonrungsesomboon N: Therapeutic potential and molecular

mechanisms of mycophenolic acid as an anticancer agent. Eur J

Pharmacol. 887(173580)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Fu S, Li Z, Xiao L, Hu W, Zhang L, Xie B,

Zhou Q, He J, Qiu Y, Wen M, et al: Glutamine synthetase promotes

radiation resistance via facilitating nucleotide metabolism and

subsequent DNA damage repair. Cell Rep. 28:1136–1143.e4.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Madsen HB, Peeters MJ, Straten PT and

Desler C: Nucleotide metabolism in the regulation of tumor

microenvironment and immune cell function. Curr Opin Biotechnol.

84(103008)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

López-Hernández L, Toolan-Kerr P,

Bannister AJ and Millán-Zambrano G: Dynamic histone modification

patterns coordinating DNA processes. Mol Cell. 85:225–237.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Charidemou E and Kirmizis A: A two-way

relationship between histone acetylation and metabolism. Trends

Biochem Sci. 49:1046–1062. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Kitabatake K, Kaji T and Tsukimoto M: ATP

and ADP enhance DNA damage repair in γ-irradiated BEAS-2B human

bronchial epithelial cells through activation of P2X7 and P2Y12

receptors. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 407(115240)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Koritzinsky M: Metformin: A novel

biological modifier of tumor response to radiation therapy. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 93:454–464. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Scott JS, Nassar ZD, Swinnen JV and Butler

LM: Monounsaturated fatty acids: Key regulators of cell viability

and intracellular signaling in cancer. Mol Cancer Res.

20:1354–1364. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Chen J, Zhang F, Ren X, Wang Y, Huang W,

Zhang J and Cui Y: Targeting fatty acid synthase sensitizes human

nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to radiation via downregulating

frizzled class receptor 10. Cancer Biol Med. 17:740–752.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Zhan N, Li B, Xu X, Xu J and Hu S:

Inhibition of FASN expression enhances radiosensitivity in human

non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 15:4578–4584.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Wu X, Dong Z, Wang CJ, Barlow LJ, Fako V,

Serrano MA, Zou Y, Liu JY and Zhang JT: FASN regulates cellular

response to genotoxic treatments by increasing PARP-1 expression

and DNA repair activity via NF-κB and SP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

113:E6965–E6973. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Chuang HY, Lee YP, Lin WC, Lin YH and

Hwang JJ: Fatty acid inhibition sensitizes androgen-dependent and

-independent prostate cancer to radiotherapy via FASN/NF-κB

pathway. Sci Rep. 9(13284)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Werner E, Alter A, Deng Q, Dammer EB, Wang

Y, Yu DS, Duong DM, Seyfried NT and Doetsch PW: Ionizing radiation

induction of cholesterol biosynthesis in lung tissue. Sci Rep.

9(12546)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

You Y, Wang Q, Li H, Ma Y, Deng Y, Ye Z

and Bai F: Zoledronic acid exhibits radio-sensitizing activity in

human pancreatic cancer cells via inactivation of STAT3/NF-κB

signaling. Onco Targets Ther. 12:4323–4330. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Peng J, Yin X, Yun W, Meng X and Huang Z:

Radiotherapy-induced tumor physical microenvironment remodeling to

overcome immunotherapy resistance. Cancer Lett.

559(216108)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Vitale I, Manic G, Coussens LM, Kroemer G

and Galluzzi L: Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor

microenvironment. Cell Metab. 30:36–50. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Nan D, Yao W, Huang L, Liu R, Chen X, Xia

W, Sheng H, Zhang H, Liang X and Lu Y: Glutamine and cancer:

Metabolism, immune microenvironment, and therapeutic targets. Cell

Commun Signal. 23(45)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

An D, Zhai D, Wan C and Yang K: The role

of lipid metabolism in cancer radioresistance. Clin Transl Oncol.

25:2332–2349. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Cao Z, Quazi S, Arora S, Osellame LD,

Burvenich IJ, Janes PW and Scott AM: Cancer-associated fibroblasts

as therapeutic targets for cancer: Advances, challenges, and future

prospects. J Biomed Sci. 32(7)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Mukherjee A, Bezwada D, Greco F,

Zandbergen M, Shen T, Chiang CY, Tasdemir M, Fahrmann J, Grapov D,

La Frano MR, et al: Adipocytes reprogram cancer cell metabolism by

diverting glucose towards glycerol-3-phosphate thereby promoting

metastasis. Nat Metab. 5:1563–1577. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Lee PWT, Suwa T, Kobayashi M, Yang H,

Koseki LR, Takeuchi S, Chow CCT, Yasuhara T and Harada H: Hypoxia-

and Postirradiation reoxygenation-induced HMHA1/ARHGAP45 expression

contributes to cancer cell invasion in a HIF-dependent manner. Br J

Cancer. 131:37–48. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Matschke J, Wiebeck E, Hurst S, Rudner J

and Jendrossek V: Role of SGK1 for fatty acid uptake, cell survival

and radioresistance of NCI-H460 lung cancer cells exposed to acute

or chronic cycling severe hypoxia. Radiat Oncol.

11(75)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Bai M, Xu P, Cheng R, Li N, Cao S, Guo Q,

Wang X, Li C, Bai N, Jiang B, et al: ROS-ATM-CHK2 axis stabilizes

HIF-1α and promotes tumor angiogenesis in hypoxic microenvironment.

Oncogene. 44:1609–1619. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Basheeruddin M and Qausain S:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) and cancer: Mechanisms of

tumor hypoxia and therapeutic targeting. Cureus.

16(e70700)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Shah R, Ibis B, Kashyap M and Boussiotis

VA: The role of ROS in tumor infiltrating immune cells and cancer

immunotherapy. Metabolism. 151(155747)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Gao F, Liu C, Guo J, Sun W, Xian L, Bai D,

Liu H, Cheng Y, Li B, Cui J, et al: Radiation-driven lipid

accumulation and dendritic cell dysfunction in cancer. Sci Rep.

5(9613)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Lyssiotis CA and Kimmelman AC: Metabolic

interactions in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol.

27:863–875. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Ashton TM, McKenna WG, Kunz-Schughart LA

and Higgins GS: Oxidative phosphorylation as an emerging target in

cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 24:2482–2490. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagés M,

Pestell RG, Sotgia F and Lisanti MP: Cancer metabolism: A

therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:11–31.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Ko J, Berger R, Lee H, Yoon H, Cho J and

Char K: Electronic effects of nano-confinement in functional

organic and inorganic materials for optoelectronics. Chem Soc Rev.

50:3585–3628. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Liu G, Müller AJ and Wang D: Confined

crystallization of polymers within nanopores. Acc Chem Res.

54:3028–3038. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Napolitano S, Glynos E and Tito NB: Glass

transition of polymers in bulk, confined geometries, and near

interfaces. Rep Prog Phys. 80(036602)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Lu S, Zhao ZQ, Wang Q, Lv ZW and Yang JS:

Biological nano confinement: A promising target for inhibiting

cancer cell progress and metastasis. Oncologie. 24:591–597.

2022.

|

|

95

|

Kuttiappan A, Chenchula S, Vardhan KV,

Padmavathi R, Varshini TS, Amerneni LS, Amerneni KC and Chavan MR:

CAR T-cell therapy in hematologic and solid malignancies:

Mechanisms, clinical applications, and future directions. Med

Oncol. 42(376)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|