Introduction

Osteoblasts and osteoclasts are the major cells of

bone that function in bone formation and bone resorption,

respectively. Osteocytes are embedded in the mineralized bone

matrix and responsible for the regeneration of adult bone cells

(1). Osteocytes continue to

increase with age and bone size. Because of the limited access to

the osteocytes in the bone matrix, knowledge of its functions

remained unclear. Due to their particular morphology, they have

multiple functions and communication features (2). Kato et al developed MLO-Y4

cells, which are remarkably close to primary osteocytes (3) and this cell line, which has high

expression of osteocalcin, connexin 43 but low alkaline

phosphatase, was obtained from a transgenic mouse. Ca2+

and phosphate metabolism is regulated by the osteocyte

lacuno-canalicular, which contains multiple proteins such as

Phosphate regulating neutral endopeptidase on chromosome X (PHEX),

Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE), sclerostin, and

Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) that can affect systemic mineral

homeostasis (4). Osteocytes also

play a role in the regulation of calcium and phosphate metabolism

which contains multiple proteins such as phosphate regulating

neutral endopeptidase on chromosome X (PHEX), matrix extracellular

phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE), sclerostin, and dentin matrix protein 1

(DMP1) that can affect systemic mineral homeostasis.

These proteins are secreted by osteocytes and have

an essential role in bone modeling and remodeling (5). DMP1 is highly expressed in

osteocytes and has a function in bone mineralization. MEPE is a

bone mineralization regulator that modifies mineralization within

the osteocyte microenvironment in response to mechanical loading.

Additionally, MEPE and DMP1 belong to the same SIBLING family

(6). Another osteocyte specific

protein is PHEX which is related to biomineralization and phosphate

homeostasis and sclerostin inhibits osteoblastic bone formation and

is expressed and released in osteocytes and other terminally

differentiated cell types embedded inside mineralized matrices

(7).

Previous studies have shown that these proteins also

have a function in the extracellular matrix as a transcription

factor (8,9). Ling et al showed that bone

mineralization was decreased in DMP1 null mice (10). MEPE protein expression was shown

in human bone osteocytes and bone marrow by Rowe et al

(11). Over-expression of MEPE

protein in bone causes a mineralization defect in a murine mice

model (12). Lu et al

reported that MEPE protein was produced by both osteoblasts and

osteocytes during skeletogenesis as early two days of the

post-natal period (13). It is

therefore clear that PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 are secreted by

osteocytes. Ca2+ is an important intracellular secondary

messenger and it is stored in the skeletal system in a form that is

linked to carbonated apatite crystals. Ca2+, on the

other hand, is found in soluble form in the extracellular domain

(14). In osteoblast cells,

increased extracellular Ca2+ has been shown to trigger

intracellular Ca2+ signaling (15). In osteoprogenitor cells, increased

Ca2+ concentration has also been shown to boost

proliferation, differentiation, protein matrix production, and

mineralized nodule formation in a dose-dependent manner (16). Ca2+ and phosphate in

the cell culture medium are often analyzed and imaged, especially

to quantify mineral deposition rates (17). The measurement of Ca/P ratios used

for the identification of the mineralization in the medium can be

compared to the ratio in tissue. Similarly, just demonstrating that

the culture's Ca2+ or phosphate concentration increases

over time is insufficient because numerous anionic matrix molecules

can bind Ca2+, and the culture's development typically

entails changes in matrix protein phosphorylation (18). The cells must produce a collagen

matrix on which the mineral will deposit, and that matrix must

contain proteins and peptides that support mineralization (19). The addition of serum used in cell

culture (which increases Ca2+ concentration) provides

both mineralization inhibitors and beneficial growth factors

(20,21).

There are limited number of studies investigating

the Ca2+ induced expression levels of bone

mineralization proteins in osteocytes. Our study was designed to

test the hypothesis, if such biological changes occur as a result

of changes in Ca2+ concentration, there would be changes

in the expression levels of PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 which play an

important role in bone formation while osteocytes induced by

different Ca2+ concentrations. On the other hand, we

have shown the apoptosis by evaluating caspase-3 levels and

oxidative stress-related enzymes CAT, SOD, GSH, NOX and TAS/TOS

levels of MLO-Y4 cell in the presence of different concentrations

of Ca2+.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

MLO-Y4 cells were purchased from the Kerafast

Company. Cells were grown to confluence in type I rat tail

collagen-coated cell culture dishes at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2 air in 5% fetal bovine

serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., 16000044)

supplemented α-MEM medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

12571063), 5% calf serum (HyClone, SH30401) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

15140122).

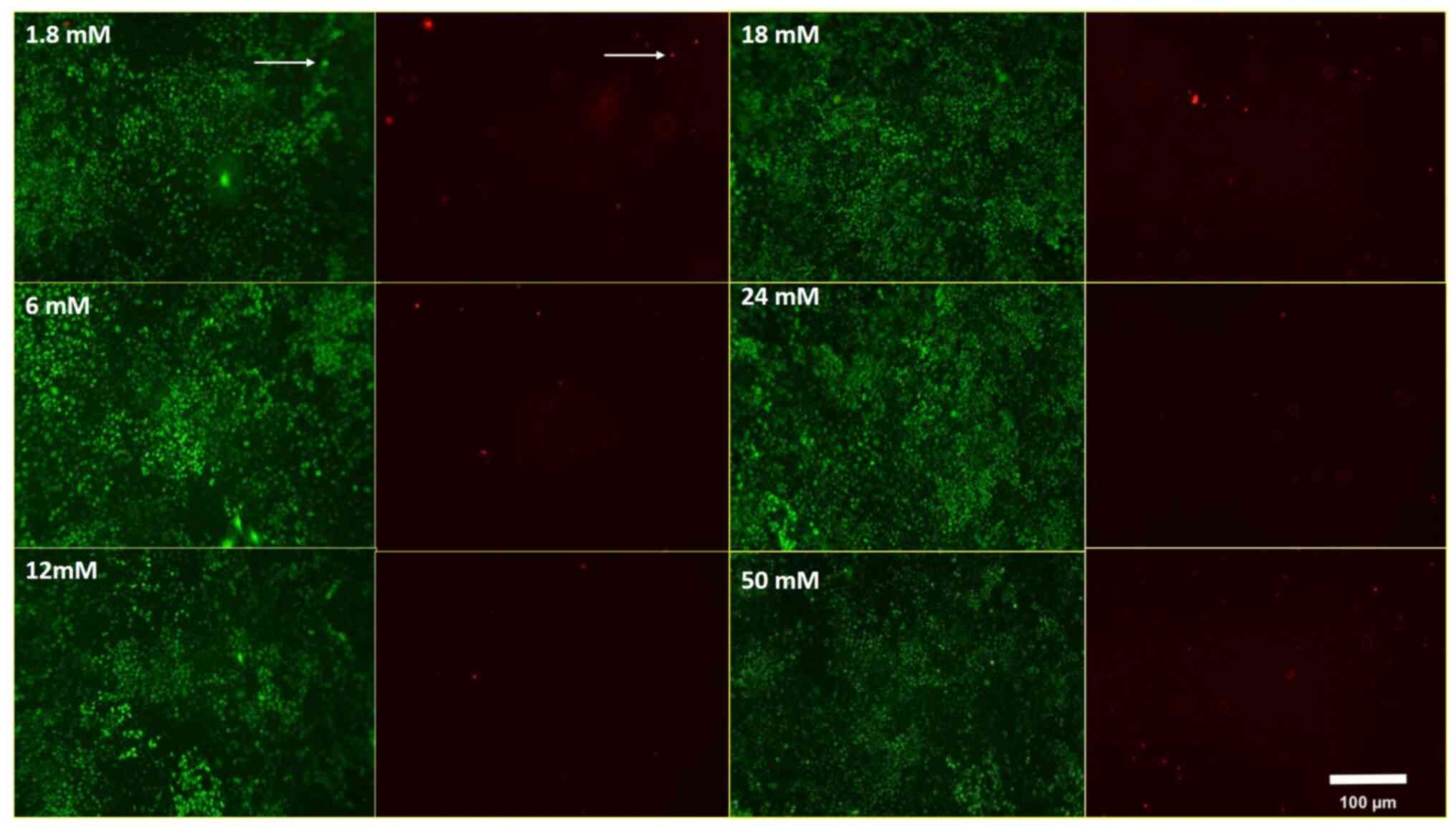

Live/dead cells assay

The cell viability of MLO-Y4 cell lines was tested

using a live/dead assay (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, CBA415) at

various Ca2+ (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, 10043-52-4)

concentrations (1.8, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 50 mM). After MLO-Y4

osteocytes were seeded 5×103 cells/cm2 in 48

collagen-coated well plates and incubated for 72 h. The cells were

treated with Ca2+ at 1.8, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 50 mM

concentrations for 15, 60 min and 24 h. After the treatment of

MLO-Y4 cells with different Ca2+ concentrations for 15

min, 60 min and 24 h, all media were removed and live/dead assay

was performed at the end of the time period. The pictures were

captured from the same region of interest for each group. At the

same time, the percentages of live and dead cells were

calculated.

CAT, SOD, GSH and NOX

measurements

To detect cellular oxidative stress, the activity of

SOD (YLA0115RA), CAT (YLA0123RA), GSH (YLA0121RA) and NOX

(YLA1501RA) enzymes were analyzed by using colorimetric diagnostic

kits (Shanghai YL Biotech, China). MLO-Y4 cells (1×106

cells) were seeded in collagen-coated 6 well plates and incubated

for 72 h. After the incubation period, the cells were treated with

the different concentrations of Ca2+ (1.8, 6, 12, 18, 24

and 50 mM) containing media for 15 and 60 min. High concentrations

of calcium led to elevated cell death in 24 h and it was difficult

to measure the oxidant-antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT, GSH, NOX

levels in dead cells. So we determined the enzyme levels in 15 and

60th min. At the end of each time point, cells were washed by PBS

three times and lysed with the ultrasonic waves to collect. Samples

were centrifugated at 2×103 g for 5 min, the

supernatants were collected and added to ELISA plate wells with

HRP-conjugate reagent and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. After the

incubation, the ELISA plate well was washed five times with the

wash buffer. Then, chromogen solution was added to each well and

avoided the light for 15 min at 37°C. After that, stop solution was

added to each well. OD value of each well was measured at 450 nm

and the activities were calculated according to the standard

curve.

Determination of the total

antioxidant, oxidant status and oxidative stress index

To determine antioxidant status and oxidant status

according to the different concentrations of Ca2+ in

MLO-Y4 cells, Rel Assay Diagnostic Total Antioxidant Status (TAS)

and Total Oxidant Status (TOS) kits (Rel Assay Diagnostic) were

utilized. Erel's method was used for the calculations (22). Oxidative Stress Index (OSI) was

measured as: OSI=[(TOS, µmol H2O2

equivalent/l)/(TAS, mmol Trolox equivalent/l) ×10].

Immunoblotting for PHEX, MEPE, DMP1

and GAPDH

Cell lysates were prepared in ice-cold RIPA buffer

(Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) after MLO-Y4 cell lines were

treated with six different Ca2+ concentrations for 24 h.

Cell lysates were spun to remove cellular debris by centrifuge at

12×103 g for 10 min at +4°C. Equal amounts of proteins

were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% polyacrylamide gels. The gels

were transferred on PVDF membrane by using a wet transfer system

overnight and were labeled to perform immunoblot analysis with PHEX

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., bs-12313R), MEPE (bioss,

bs-8689R), DMP1 (biorbyt, orb255063), GAPDH (Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) and Horseradish peroxidase-labeled antirabbit

secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Proteins

were visualized by using Image Studio Lite Ver 4.0 in LI-COR.

Protein-content determination was measured by the method described

by Bradford.

Caspase-3 analysis

The activity of the caspase-3 was measured using a

colorimetric assay (Elabscience). Centrifugation at

1×103 g for 10 min was used to collect cells that had

been exposed to six different concentrations of Ca2+ for

15 and 60 min. Lysis buffer was used to lyse the pelleted cells.

Then, the cell lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min and were

centrifuged at 14×103 g for 1 min. Following the

centrifugation, supernatants were transferred to new tubes. For

measuring caspase-3 enzyme activity, 100 µl of the samples were

added to the wells, after the incubation period 100 µl Biotinylated

Detection Antibody working solution, 100 µl HRP conjugate working

solution, 90 µl Substrate Reagent and 50 µl Stop Solution applied

to each well respectively and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in

CO2 incubator. Absorbances of the samples were read

under 450 nm via the ELISA reader (Biotek).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of

three independent determinations. The non-parametric approach was

preferred and the Kruskal Wallis analysis of variance was used for

comparison between groups. When a significant difference was

detected as a result of the Kruskal Wallis test, the post hoc

Dunn's test was used. In the Kruskal Wallis analysis of variance

results, P<0.05 was accepted as significant. All analyses were

performed with SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software (IBM

Corp.) package program.

Results

The effects of Ca2+

concentration cell viability in MLO-Y4 cells

Since Ca2+ has a critical role in bone

mineralization, we have designed to investigate the effect of

Ca2+ concentration on cell viability in an experiment

that consists of six different Ca2+ concentrations and

three-time points. After MLO-Y4 cells were treated with 1.8, 6, 12,

18, 24 and 50 mM Ca2+ for 15 min, cell viability was

determined by live/death assay. After Ca2+ treatment at

the 15th min, there were much more live MLO-Y4 cells than dead

MLO-Y4 cells in all Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 1). Based on the above results, we

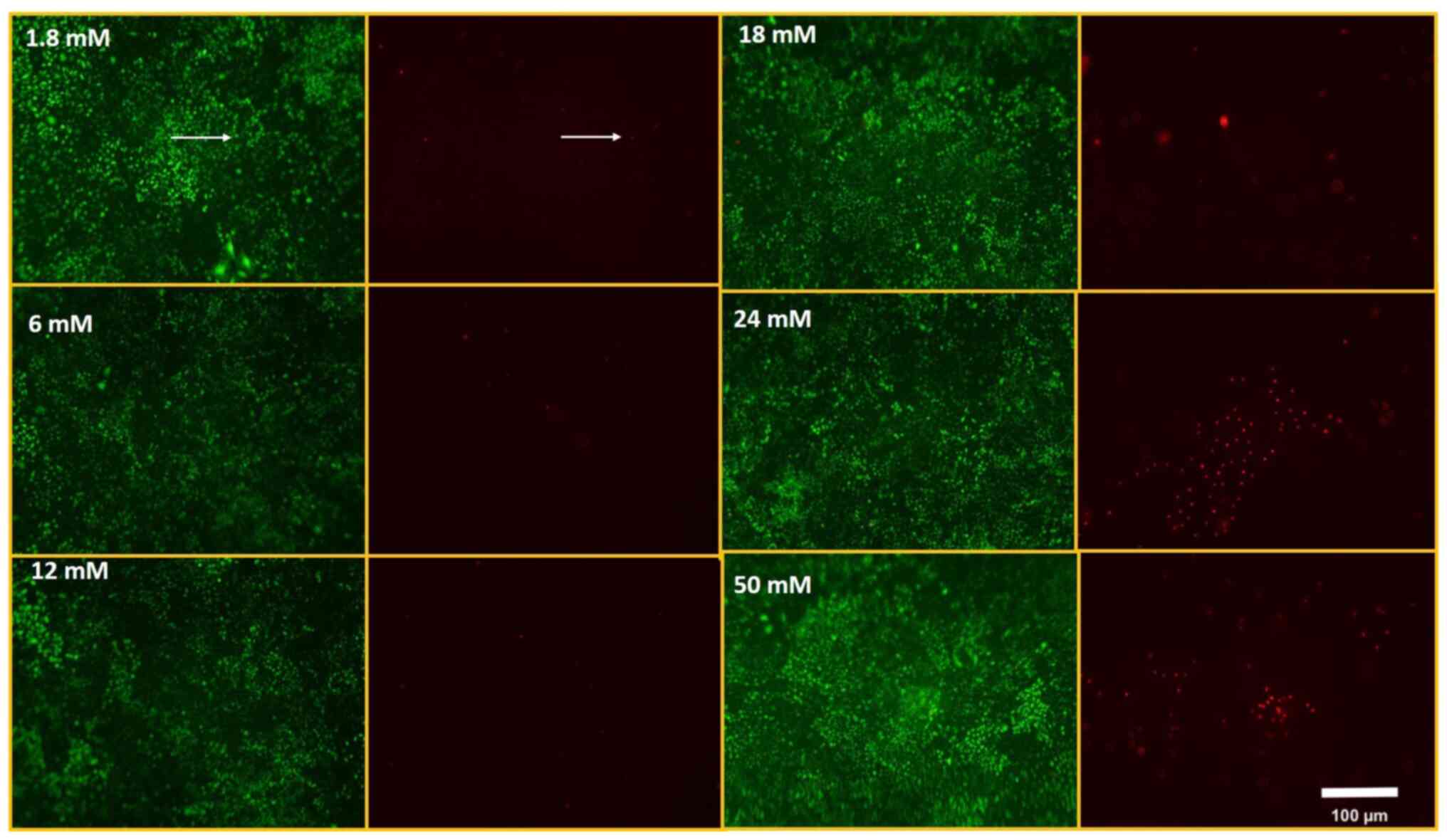

questioned whether there was a correlation between the incubation

period of Ca2+ and cell viability. Therefore; we set up

two experiments as 60 min and 24 h at the same Ca2+

concentrations. Dead cells were increased at 24 and 50 mM

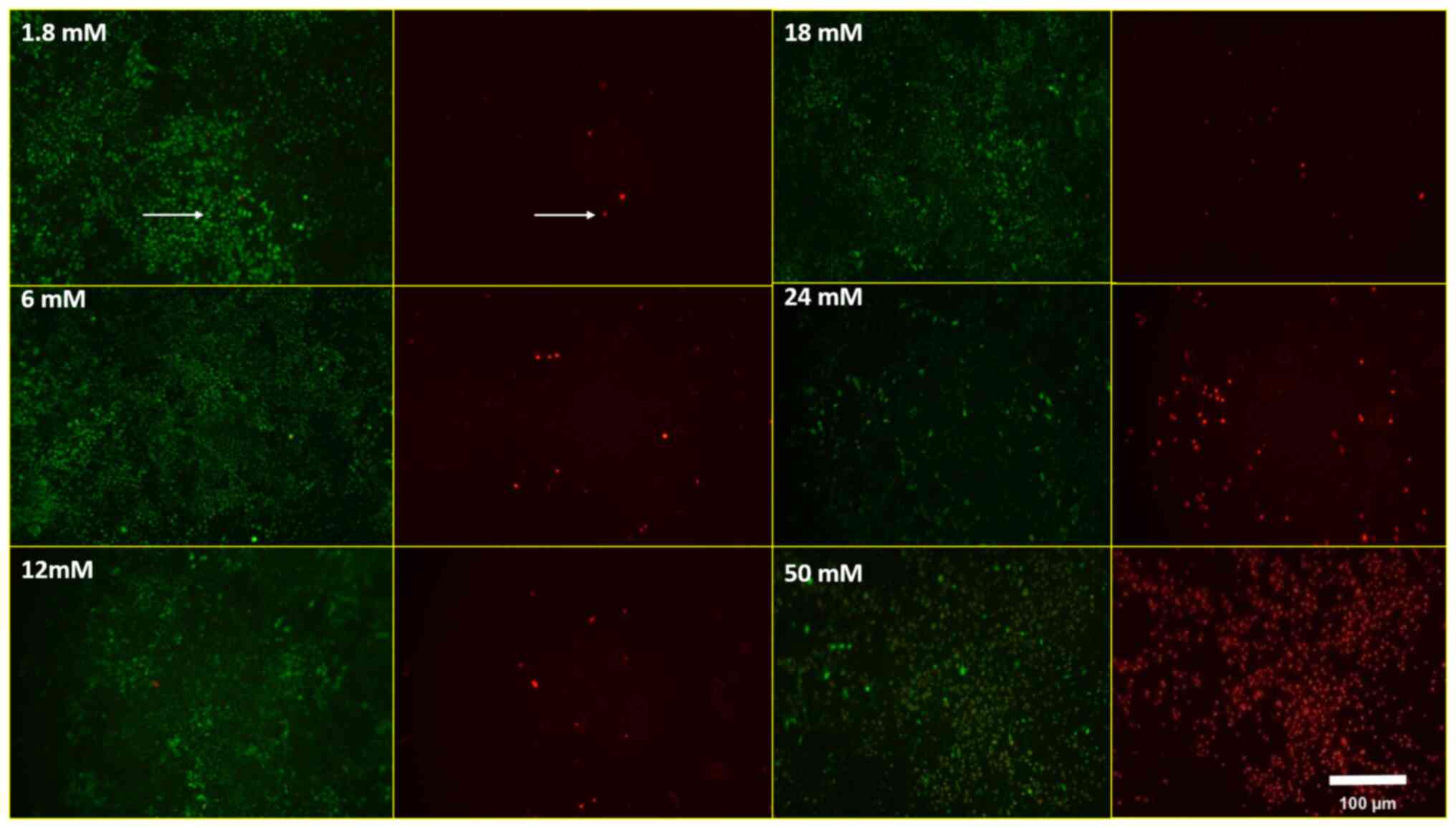

Ca2+ concentrations in 60 min (Fig. 2). In 24 h of Ca2+

treatment, there were much more dead cells than live MLO-Y4 cells

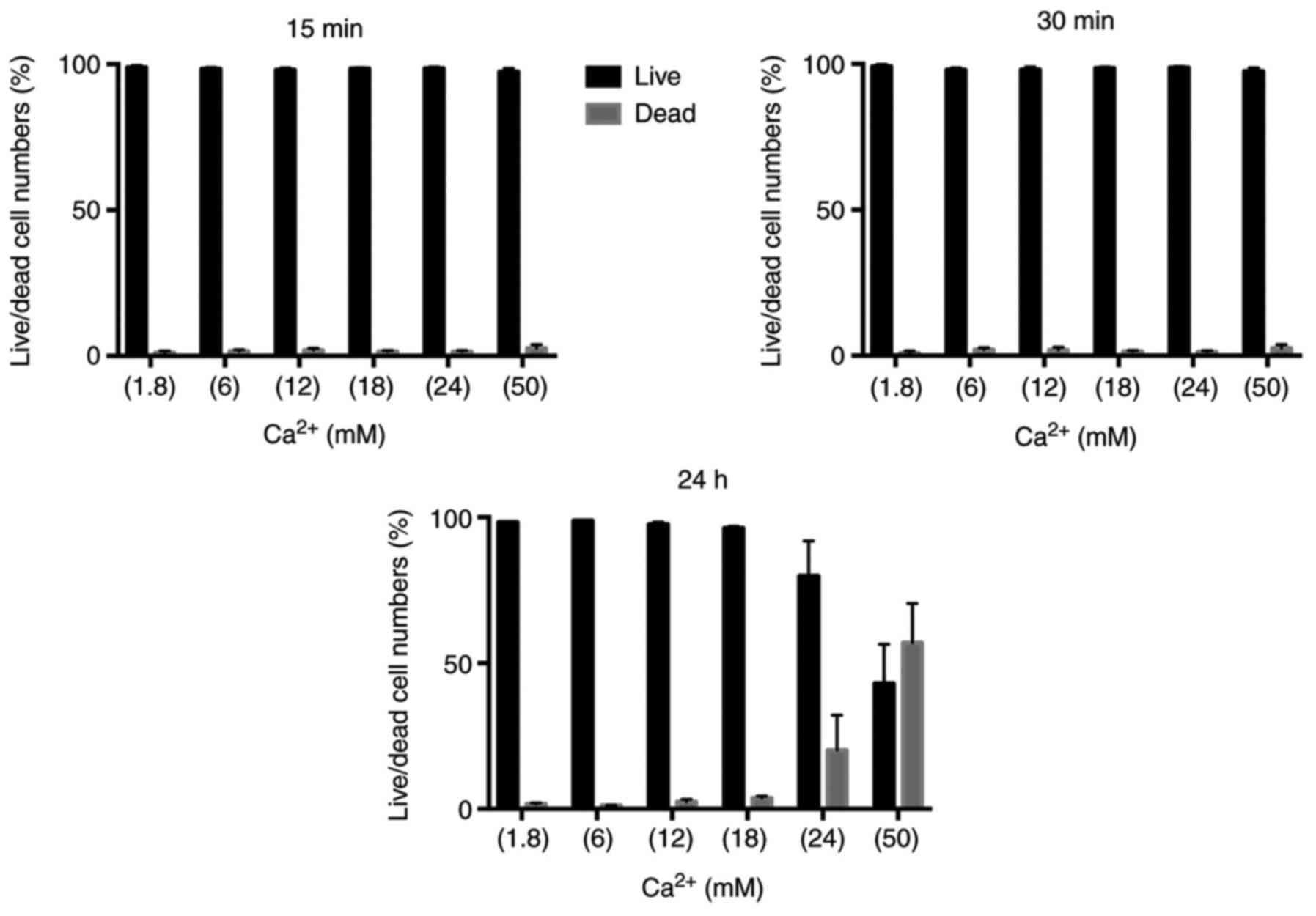

on 50 mM Ca2+ treatment (Fig. 3). The percentage of live/dead

cells were shown in Fig. 4.

The Ca2+ increases CAT,

SOD, GSH and NOX levels in MLO-Y4 cell lines

Ca2+ has important role between the free

radical and enzymatic antioxidant capacity in bone metabolism.

Therefore, we aimed to show how Ca2+ stimulation

regulates the CAT, SOD, GSH and NOX levels. After MLO-Y4 cells were

treated with Ca2+ (1.8, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 50 mM) for 15

and 60 min, CAT, SOD, GSH and NOX levels were determined by ELISA

assay.

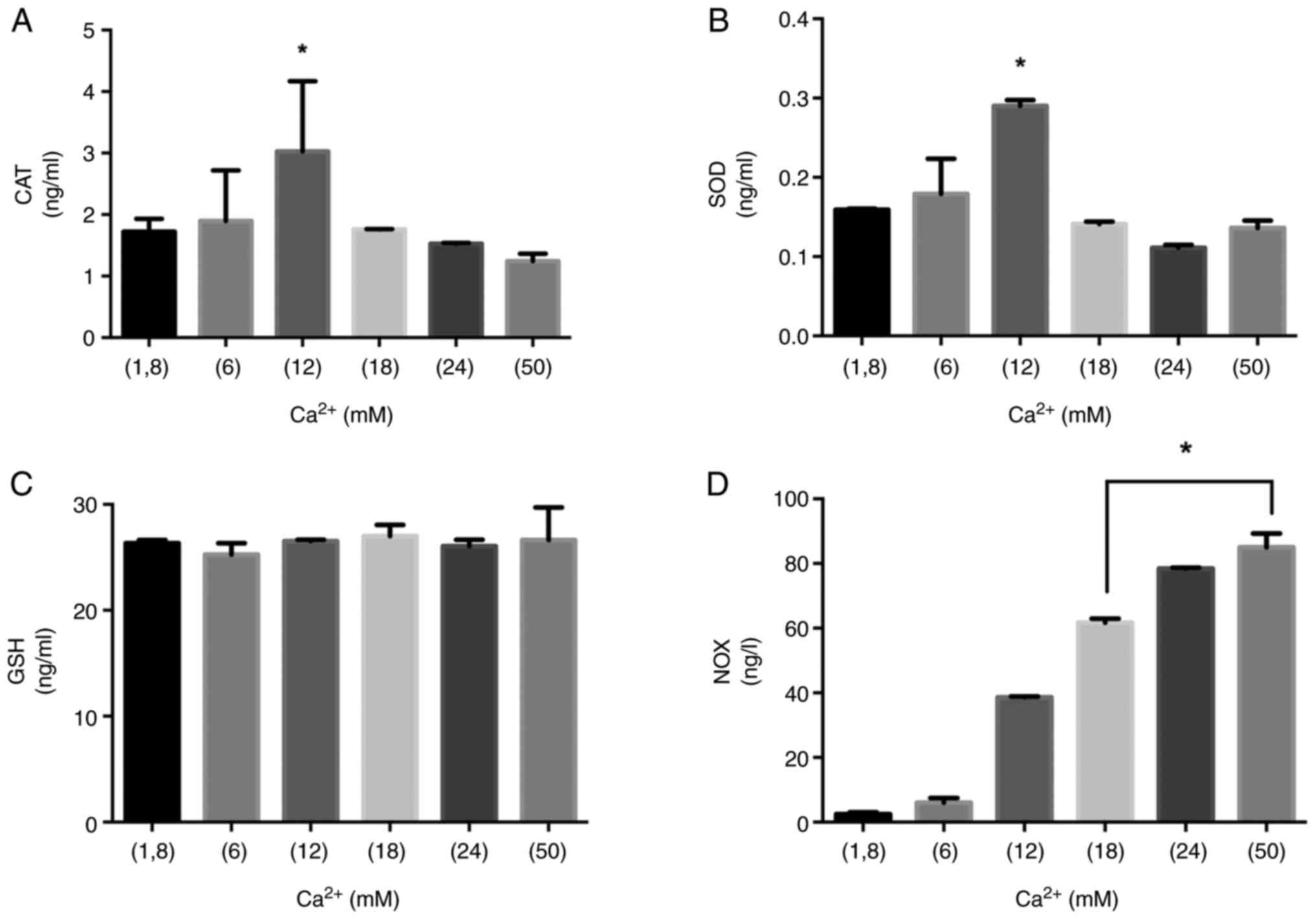

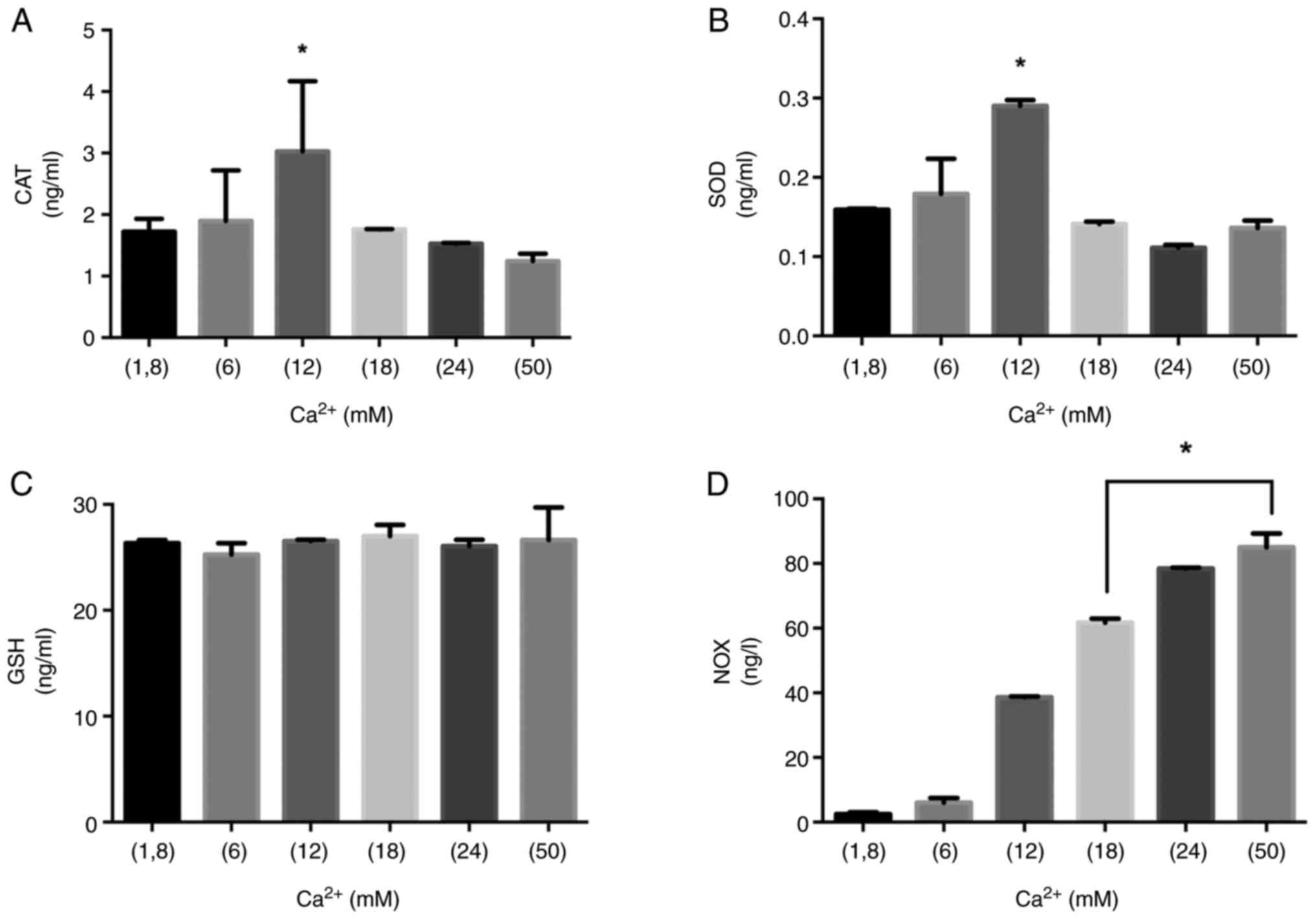

SOD and CAT increased and reached the maximum levels

in 12 mM Ca2+ in 15 min (Fig. 5A and B). GSH levels in different

Ca2+ inductions did not differ significantly (Fig. 5C). In 15 min, the higher

Ca2+ levels steadily raised NOX levels (Fig. 5D). 18, 24 and 50 mM

Ca2+ concentrations led to the depletion of antioxidant

enzymes such as CAT and SOD. The significantly increased NOX

activity was observed in 18, 24 and 50 mM Ca2+

concentrations (P<0.05) (Fig.

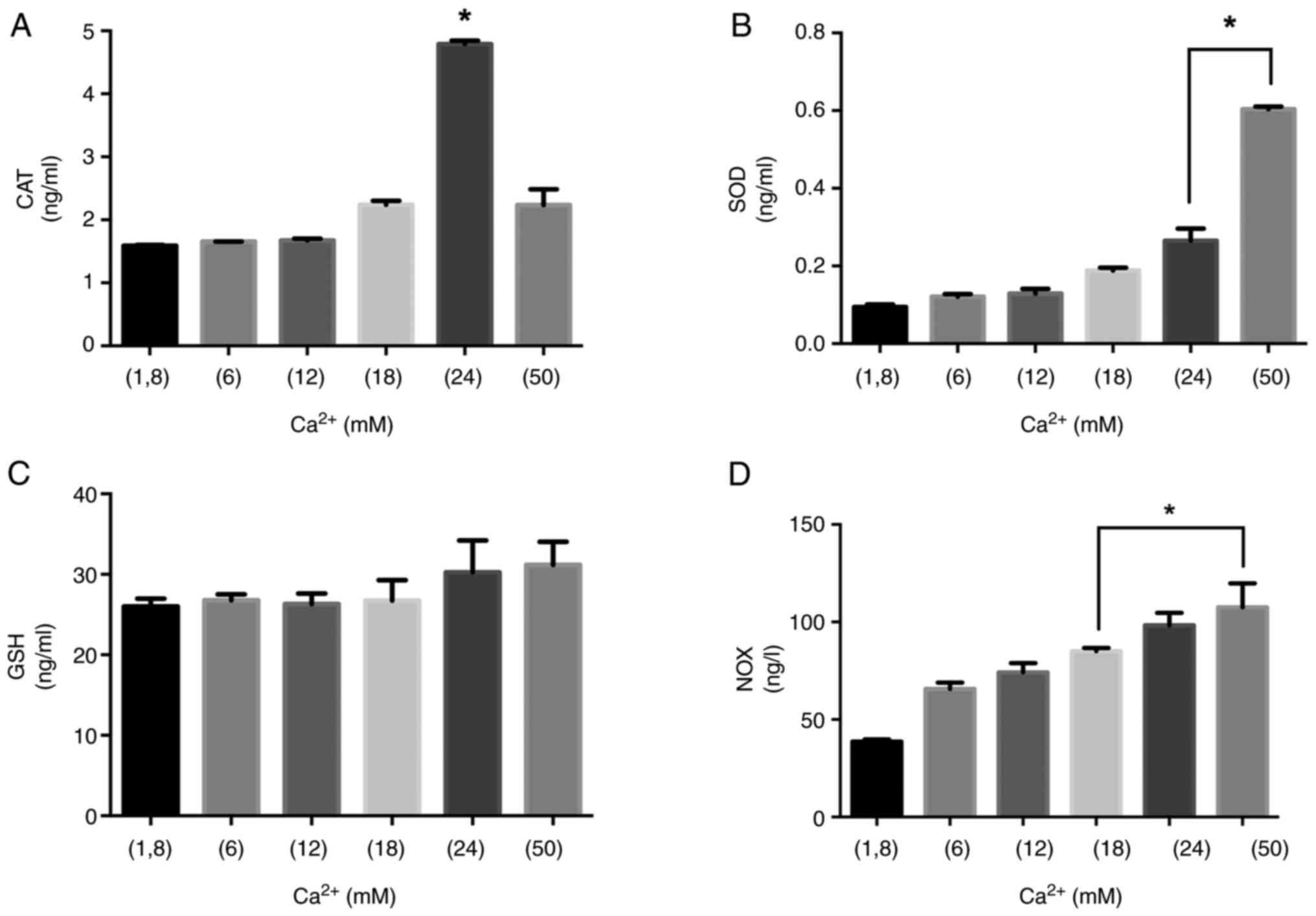

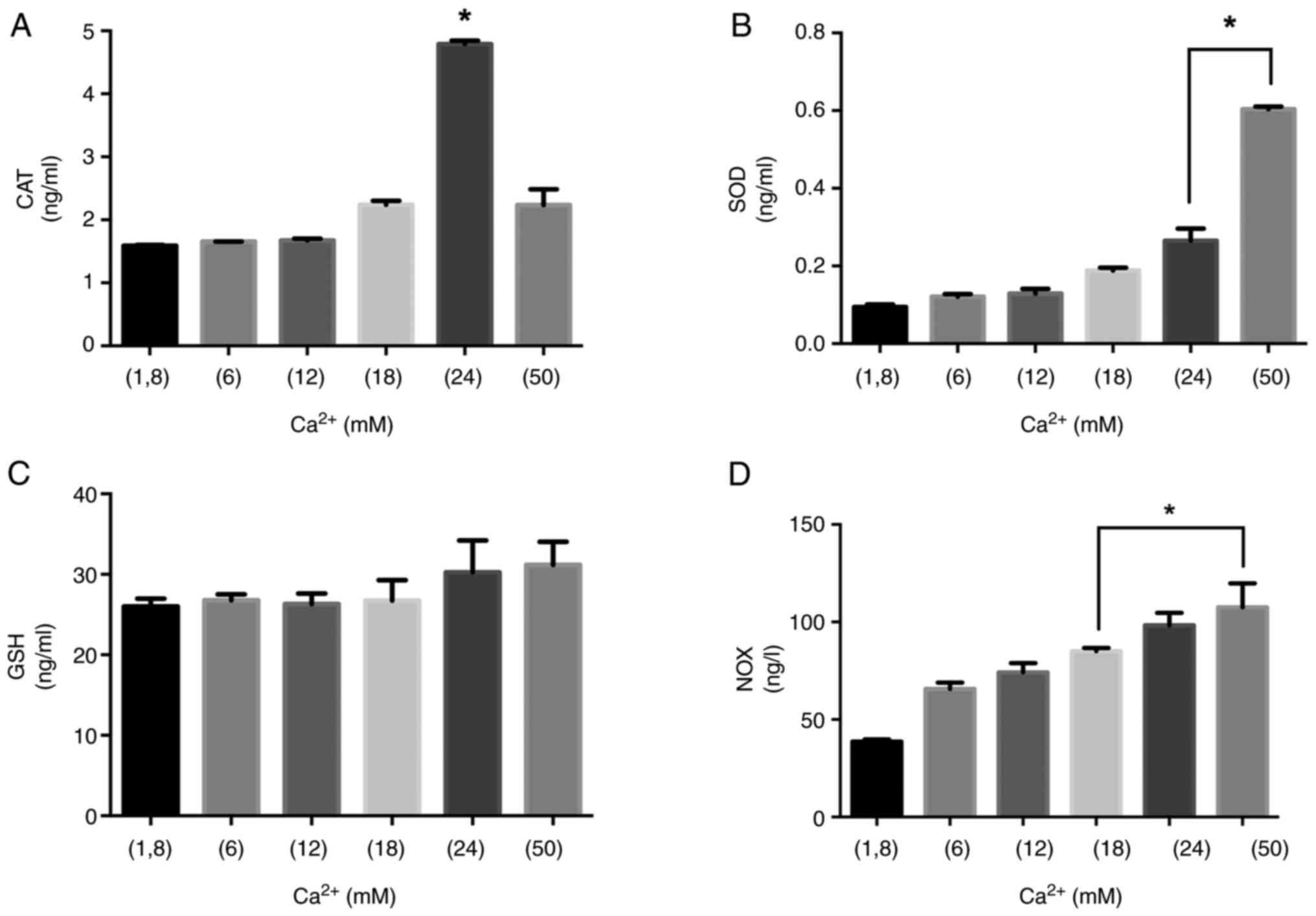

5D). 24 mM Ca2+ concentration led to a significant

increase in CAT levels within 60 min of treatment (Fig. 6A). SOD activity gradually

increased by the elevated concentrations of Ca2+ in 60

min. The statistically significant difference in SOD was observed

in 24 and 50 mM Ca2+ concentrations compared to that of

1.8 mM Ca2+ treatment in 60 min (Fig. 6B). There was no significant change

in GSH activity in different Ca2+ points (Fig. 6C). NOX activity was at the highest

level in 24 and 50 mM compared to that of 1.8 mM Ca2+

concentrations in 15 and 60 min (Fig.

6D). Our results clearly show that 12 mM Ca2+

concentration augments CAT and SOD levels, but from the beginning

of 12 mM Ca2+ application NOX enzyme levels

significantly increased in dose dependent on manner in 15 and 60

min. 24 mM Ca2+ concentration significantly increased

SOD and CAT levels in 60 min. GSH levels of MLO-Y4 cells were

stable by the induction of different Ca2+ concentrations

and different time points. NOX activity gradually increased

concentration and time.

| Figure 5.CAT, SOD, GSH and NOX levels at 15

min. The role of the Ca2+ on oxidant/antioxidant balance

in MLO-Y4 at the incubation of 15 min. (A) CAT, (B) SOD, (C) GSH

and (D) NOX levels were measured in MLO-Y4 cells treated with

Ca2+ (1.8, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 50 mM) for 15 min.

*P<0.05 vs. 1.8 mM Ca2+ group. CAT, catalase; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; NOX, NADPH oxidase. |

| Figure 6.CAT, SOD, GSH and NOX levels at 60

min. The role of the Ca2+ on oxidant/antioxidant balance

in MLO-Y4 at the incubation of 60 min. (A) CAT, (B) SOD, (C) GSH

and (D) NOX levels were measured in MLO-Y4 cells treated with

Ca2+ (1.8, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 50 mM) for 60 min.

*P<0.05 vs. 1.8 mM Ca2+ group. CAT, catalase; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; NOX, NADPH oxidase. |

Ca2+ induces bone

mineralization by triggering crosstalk between ROS dependent

activation and PHEX, MEPE, DMP1

Previous studies have shown that ROS and/or

antioxidant systems are related to the pathogenesis of bone loss.

In our study; TAS and TOS levels were measured at the end of the 24

h of different concentrations of Ca2+ application, and

OSI was calculated (Table I).

While the amount of Ca2+ increased, total oxidant status

and OSI were significantly increased at 12, 18, 24 and 50 mM

Ca2+ (P<0.05 compared to 1.8 mM Ca2+).

| Table I.TAS, TOS and OSI were measured in

MLO-Y4 cells after 24 h of Ca2+ application. |

Table I.

TAS, TOS and OSI were measured in

MLO-Y4 cells after 24 h of Ca2+ application.

| Experimental

group | TAS (mmol/l) | TOS (µmol/l) | OSI (arbitrary

unit) |

|---|

| 1.8 mM Ca | 0.366 |

4.580 |

1.250 |

| 6 mM Ca | 0.180 |

4.580 |

2.544a |

| 12 mM Ca | 0.252 | 17.328a |

6.877a |

| 18 mM Ca | 0.383 | 18.244a |

4.758a |

| 24 mM Ca |

0.149a | 21.374a | 14.376a |

| 50 mM Ca | 0.390 | 27.786a | 7.130a |

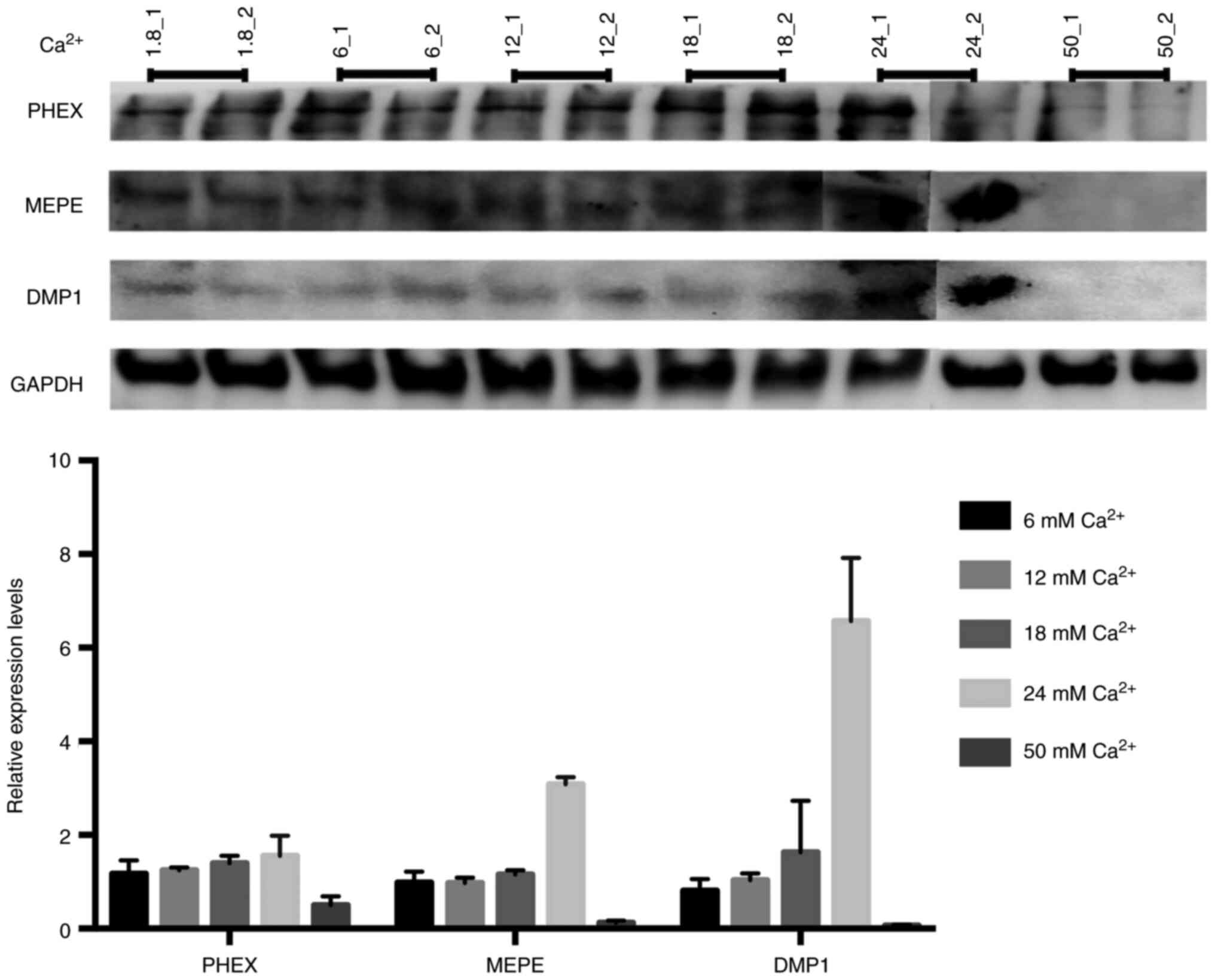

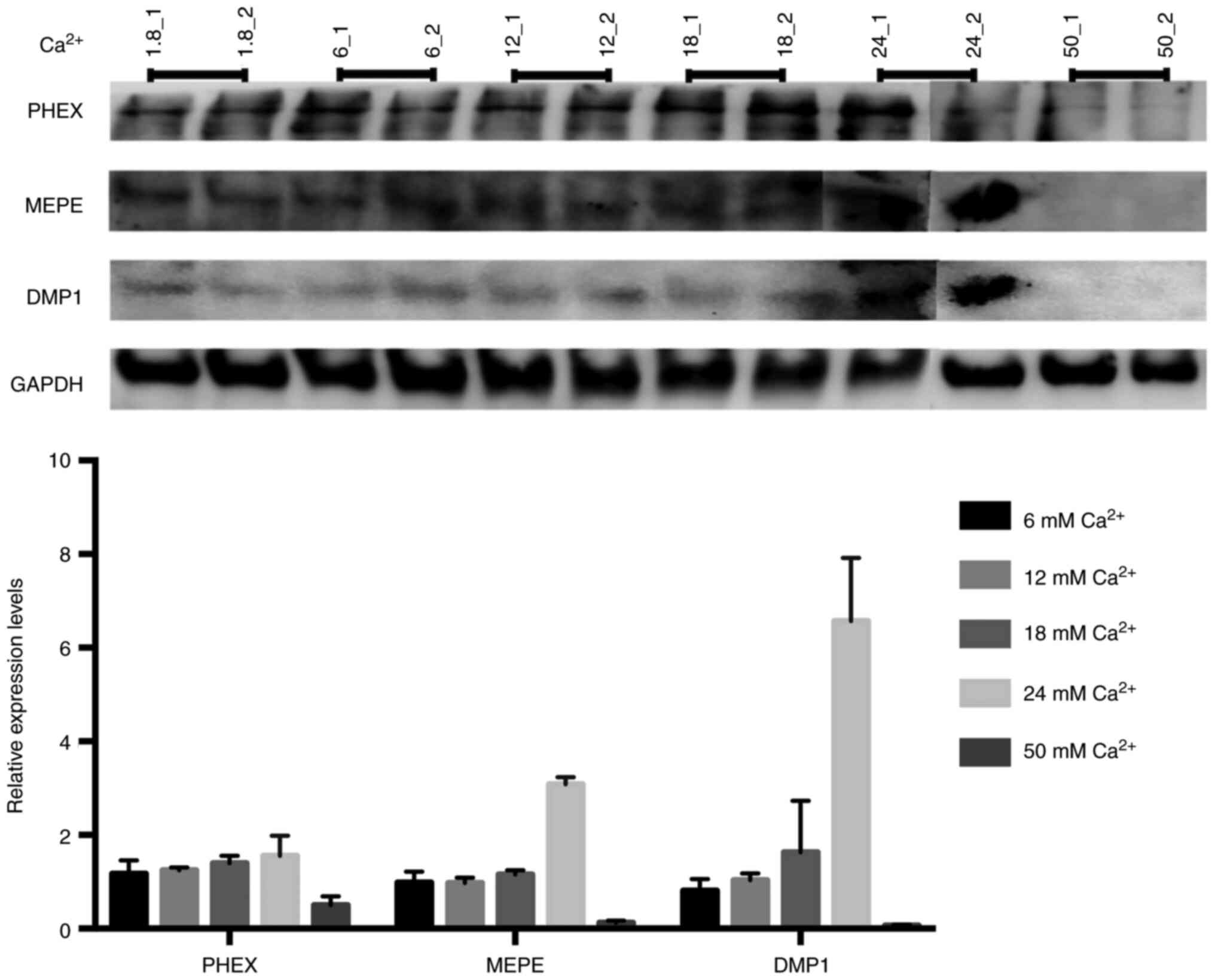

Ca2+ upregulates crosstalk

between PHEX, MEPE, DMP1 expression and bone mineralization

PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 play an important role in bone

remodeling. Therefore, to assess the expression levels of PHEX,

MEPE and DMP1 in MLO-Y4 cells, we performed Western Blot analysis.

Immunoblot analysis revealed that Ca2+ upregulates

expressions of PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 in a dose dependent manner. The

highest expression levels of PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 were seen at 24 mM

Ca2+ treatment. We also observed a depletion/feedback in

the expression of PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 at 50 mM Ca2+

concentration. The expression of PHEX, a pro-mineralization gene,

was notably increased at the 24 mM Ca2+ but was

suppressed at 50 mM Ca2+; the highest tested

concentration of Ca2+. Increased exposure to

Ca2+ appeared to alter the interaction of other

osteoblast mineralization-associated genes. Our data show that

optimum Ca2+ concentration induces bone mineralization

while high Ca2+ concentration cause depletion of PHEX,

MEPE and DMP1 expression (Fig.

7).

| Figure 7.PHEX, DMP1 and MEPE expression

levels. The Ca2+ promotes the PHEX, DMP1/MEPE axis.

Western blotting analysis of PHEX, MEPE, DMP1 and GAPDH levels in

MLO-Y4 cells treated with different concentrations of

Ca2+. Each Ca2+ concentration was analyzed

densitometrically according to its GAPDH (n=2), (_1 is sample one,

_2 is sample two of each Ca2+ concentration). Two

sibling gels were prepared, run and transferred in the same

electrophoresis equipment. 24_2, 50_1 and 50_2 samples were loaded

to the sibling gel. PHEX, phosphate-regulating neutral

endopeptidase on chromosome X; DMP1, dentin matrix protein 1; MEPE,

matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein. |

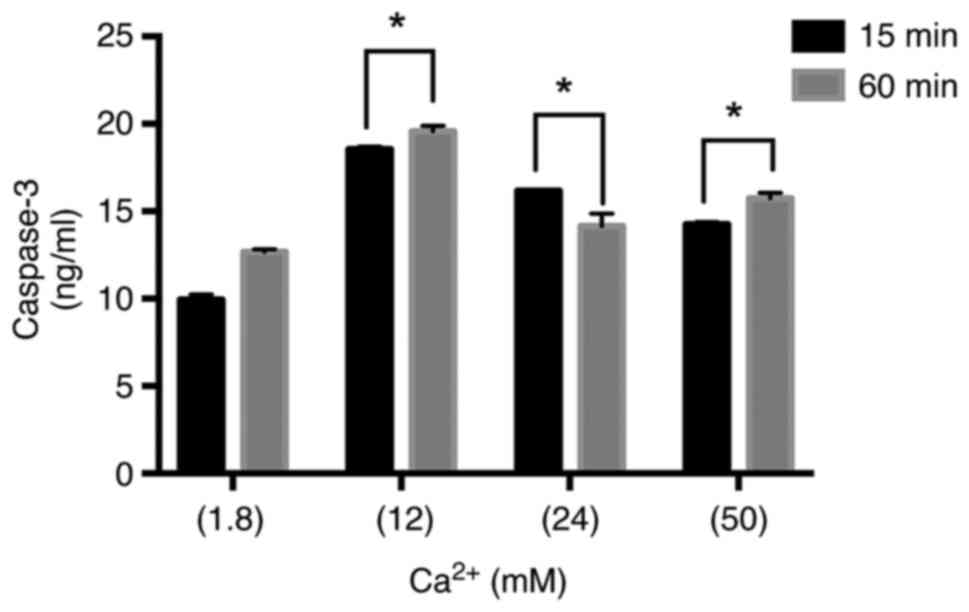

Caspase-3 analysis

Caspase-3 levels were studied in MLYO-4 cells grown

in complete media supplemented with different concentrations of

Ca2+ for 15 and 60 min. Caspase-3 levels were

significantly elevated by the 12, 24 and 50 mM Ca2+ when

compared to 1.8 mM Ca2+ treated control cells in both

timelines. The rate of rising was most visible in 12 mM compared to

other groups in 15 and 60 min. Incubation of MLO-Y4 cells with 1.8,

12, 24 and 50 mM of Ca2+ for 60 min led to increased

caspase-3 levels compared to the 15 min treatment for each

(Fig. 8). The data obtained from

our results show all (12, 24 and 50 mM) Ca2+

concentrations stimulated the caspase-3 activity which is the key

factor for the initiation of the apoptotic pathway.

Discussion

Calcium plays an important role in many basic

biological processes like the muscle system, neural system, enzyme

activity, hormone metabolism, and membrane permeability. Moreover,

Ca2+ is an important structural component of the

skeleton. Additionally, control of Ca2+ ion in the

extracellular fluid is vital for many metabolic activities and some

endocrine control systems have developed to maintain constant

Ca2+ concentration (23). Additionally, the breakdown of

mesoporous bioactive glass scaffold releases active substances like

calcium that have the potential to increase gene expression and

cause osteoblast development and they also suggested that

electrical stimulation could encourage cellular differentiation by

controlling calcium ionic pathways and increasing calcium ion

inflow into cells (24,25). Total calcium levels in healthy

persons are normally kept within the range of 2.2-2.6 mM, while

ionized calcium levels are usually maintained between 1.1-1.3 mM.

However, soluble Ca2+ levels in the bone interstitial

fluid may be higher, since previous studies demonstrated that the

levels of Ca2+ ranged from 8 to 40 mM at the nearest

area of the resorbing osteoclasts (26,27). Ca2+concentrations can

range from 8 to 40 mM in the microenvironment of the resorbing

osteoclast. Osteocytes can also release considerable quantities of

Ca2+, as seen during lactation, implying that they are

exposed to high extracellular Ca2+ concentrations

(27). Elevated serum free

calcium concentrations may have an impact on the maximal calcium

concentration in the interstitial fluid of the bone that is closely

next to osteoclasts. According to Sugimoto et al, bone

remodeling depends on the presence of mononuclear cells and a high

calcium concentration at the resorptive site (28).

Our results indicate that Ca2+

concentration significantly inhibits cell viability in a dose and

time-dependent manner (Fig. 1,

Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Changes in Ca2+

concentration have been shown to promote the function and

cooperation of the osteocytes and osteoblasts (29). It has also been shown that many

biological activities such as muscle contraction and nerve

conduction are regulated as a result of these changes in

Ca2+ concentration, which occurs outside the cell,

especially in the presence of mechanical stress. Osteocytes are

derived from the mature osteoblasts that have a more differentiated

morphology during the bone formation process and are embedded in

the matrix (30). The osteocytes

contact with adjacent cells and communicate via dendritic processes

in the canaliculi in the mineralized matrix of the bone.

Furthermore, osteocytes can communicate with other cells by

secreting factors into the bone marrow space or straight into the

bloodstream (31,32). Cellular oxidative damage is a

basic general mechanism of cell damage and is mainly caused by

reactive oxygen species (ROS). While ROS is overproduced, it can

cause oxidative stress which is characterized as an imbalance

between ROS formation and antioxidant defense systems (33) and NADPH oxidases (NOX) produce ROS

in a controlled to specifically regulate signal transduction

(34). Oxidative stress can

affect age-related diseases, including osteoporosis and

significantly affect osteocytes. Increasing concentrations of

cytoplasmic Ca2+ causes Ca2+ influx into

mitochondria and Ca2+ disrupts metabolism of the cell.

Additionally, Ca2+ in the cytoplasm can regulate

phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of proteins (35). The lack of an impact of Ca channel

inhibitors on expression levels of PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 proteins,

SOD, CAT, GSH, NOX and Caspase-3 levels and total antioxidant and

oxidant status is a limitation of our work. A further in

vivo examination is necessary to determine the effect of high

serum calcium concentrations on bone remodeling, which is another

limitation of our work.

Cellular oxidative stress disrupts bone remodeling

and leads to an imbalance between osteoclast and osteoblast

activity. Previous studies have shown that ROS and/or antioxidant

systems are related to the pathogenesis of bone loss (36). Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone

disease characterized by low bone mineral density and a loss in

bone mass, making the bone fragile and prone to fracture (37). According to a recent review

article by Domazetovic et al, few data have shown how the

molecular mechanism changes with apoptosis and oxidative status

(38) but, recently, more studies

have been aiming to explain the details.

In the present study, antioxidant-oxidant (CAT, SOD,

GSH and NOX) enzyme levels were measured after 15 and 60 min of

Ca2+ administration in MLO-Y4 cells (Figs. 5 and 6). Additionally, ROS induces the

apoptosis of osteoblasts and supports osteoclastogenesis (39). Advanced oxidation products had

been shown to inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of rat

osteoblastic cells and rat mesenchymal stem cells (40) but osteocytes have been reported as

a major source of the cytokine receptor activator of nuclear factor

kappa-B ligand (RANKL), its functions as a key factor for

osteoclast differentiation and activation (41). Yu et al reported that the

treatment with advanced oxidation protein products significantly

triggered apoptosis of MLO-Y4 cells and induced the phosphorylation

of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein

kinases. Their findings cumulatively suggest that the advanced

oxidation protein products induced activation of JNK/p38 MAPK is

reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent (42). Superoxide is formed when oxygen

acquires an additional electron and oxygen is generally converted

by the superoxide dismutase (SOD) which is the first enzymatic

structure of the antioxidant defense system (43). Kobayashi et al revealed

that mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 (Sod2) depletion

in osteocytes improved the production of cellular superoxide and

Sod2 loss decreased the number of live osteocytes inside the

lucano-canalicular networks (44). To estimate oxidative and

antioxidative status in cells, TOS and TAS are generally used.

While Ca2+ concentration was increased, TOS and the OSI

values also increased in our findings (Table I). Glutathione (GSH) is a

tripeptide in living organisms and it acts as an antioxidant either

directly by interacting with ROS (45). There was no significant difference

between GSH levels of different Ca2+ concentrations. CAT

is the one of the most important antioxidant enzymes which break

down two H2O2 molecules into one molecule of

oxygen and two molecules of water (46). Increased concentrations of

Ca2+ in 15 min treatments led to elevated CAT activity.

Previous studies suggested that concentrations of Ca2+

in the range of 10–15 mM demonstrated a moderate negative effect on

cell survival in calvarial cells of the newborn mouse (26). Consistent with these findings, our

study demonstrates that 12, 24 and 50 mM Ca2+

concentrations result in elevated caspase-3 levels osteocytes are

sensitive to the extracellular concentration of Ca2+, up

to around 12 mM in 15 and 60 min of induction (Fig. 7). PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 are

essential proteins released from osteocytes and play a significant

role in bone mineralization. Topically administered Ca2+

to osteocytes in varying amounts could have a variety of effects.

The goal of our study was to reveal the changes in bone

mineralization-related protein levels in different Ca2+

concentrations and at different time points. Our results showed

that PHEX, MEPE, and DMP1 expression levels correlated to the

increased concentrations of Ca2+ (6, 12, 18 mM). The

highest increase in PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 expressions was observed at

a Ca2+ concentration of 24 mM (Fig. 7). However, the expression levels

of the proteins decreased at 50 mM Ca2+ concentration

because of the enhanced dead cell ratio.

Some important clinical problems arise in deficiency

or inactivation of PHEX and MEPE and it is important to understand

the metabolism of these proteins. The inactivation of PHEX or/and

DMP1 has been shown to result in an increased fibroblast growth

factor 23 (FGF23) (47), and they

play a key role in the progression of hypophosphatemic conditions

such as tumor-induced osteomalacia and X-linked hypophosphatemic

rickets/osteomalacia. PHEX deficiency results in the overproduction

of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) in osteocytes (48), which leads to hypophosphatemia and

impaired vitamin D metabolism (47). Miyagawa et al noted that

DMP1 expression in osteocytic cells was increased after the 24 h

treatment with 10 mM phosphate (47). Both PHEX and DMP1 are also

important proteins on phosphate homeostasis. Because another role

of osteocytes is to regulate phosphate (Pi) homeostasis through the

release of several molecules such as PHEX, MEPE, DMP1 and FGF23

(49). DMP1 and PHEX inhibit the

expression of FGF23, whereas MEPE increases it, although the

mechanisms are still unknown (50,51). Both DMP1 and PHEX are excessively

expressed in osteocytes and might regulate the maturation of the

osteocyte cells via FGF23 regulation of phosphate homeostasis

(8). Magne et al cultured

M2H4 cells and supplemented the media with 3 mM Pi from day 8 to 20

(20). They have shown that M2H4

cells had more mineralized the dentin extracellular matrix than

control conditions (1 mM Pi) and medium supplemented 3 mM Pi

accumulate Ca2+ in cell layers (20). In our study, both expressions of

PHEX and MEPE increased at 24 mM Ca2+ induced.

Increased levels of both PHEX and MEPE in the

treatment of 24 mM Ca2+ are important for osteocytes

metabolism and they might be used in bone treatment in the future.

PHEX, MEPE, and DMP1 have also been demonstrated to be controlled

during loading and unloading settings in previous investigations

(52–54). These proteins involved in bone

construction are expected to be upregulated in response to anabolic

loading, and they are responsible for absorption (55). Gluhak-Heinrich et al

(52) revealed that alveolar

osteocytes showed high basal levels of MEPE that decreased during

the first day of loading compared to that of DMP1. Kulkarni et

al (56) have shown that

mechanical loading upregulated gene expression of MEPE but not PHEX

in MLO-Y4 cells during 1 and 6 h pulsating fluid flow. RANKL plays

an important role during the loading/unloading mechanism because

unloading increases RANKL which is an essential promoter for

osteocytes (57). Osteocytes has

dendritic process, which is associated with mechanical stimulation,

and this process is regulated by E11 which is the earliest

osteocytes protein increased by mechanical loading by osteocytes

(58). Moreover, E11, MEPE and

DMP1 have higher levels of expression in basal bone than in

alveolar bone (59). During the

skeleton is exposed to loading, an increase in these proteins

secreted from osteocytes can be expected, which is very important

in the mineralization of bone tissue. A new strategy for bone

treatment can be designed by giving the appropriate Ca2+

concentration to increase the release of these proteins from

osteocytes.

In a summary, our results suggest that high

Ca2+ concentrations can perturb osteocyte cell

hemostasis which leads to tissue damage and apoptosis of the bone

and result in metabolic bone diseases such as osteoporosis. 24 mM

Ca2+ concentration can trigger bone mineralization

markers such as PHEX, MEPE and DMP1 can be a convenient dosage for

the treatment of bone damage.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Pamukkale University (grant nos.

2019BSP006 and 2019BSP002).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

BOD and OA designed all experimental procedures of

the study, and BOD conducted cell culture and the live/dead cells

assay. ACD and ERK conducted CAT, SOD, GSH and NOX measurements,

determination of TAS and TOS, immunoblotting for PHEX, MEPE, DMP1

and GAPDH, and caspase-3 analysis. ACD and ERK confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. JC calculated the percentage of

live and dead cells. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Palumbo C and Ferretti M: The osteocyte:

From ‘Prisoner’ to ‘Orchestrator’. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol.

6:282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Florencio-Silva R, da Silva Sasso GR,

Sasso-Cerri E, Simões J and Cerri PS: Biology of bone tissue:

Structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. Biomed

Res Int. 2015:4217462015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kato Y, Windle JJ, Koop BA, Mundy GR and

Bonewald LF: Establishment of an osteocyte-like cell line, MLO-Y4.

J Bone Miner Res. 12:2014–2023. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Robling AG and LF, . Bonewald the

osteocyte: New insights. Annu Rev Physiol. 82:485–506. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kao RS, Abbott MJ, Louie A, O'Carroll D,

Lu W and Nissenson R: Constitutive protein kinase A activity in

osteocytes and late osteoblasts produces an anabolic effect on

bone. Bone. 55:277–287. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fisher LW and Fedarko NS: Six genes

expressed in bones and teeth encode the current members of the

SIBLING family of proteins. Connect Tissue Res. 44 (Suppl

1):S33–S40. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Guo D, Keightley A, Guthrie J, Veno PA,

Harris SE and Bonewald LF: Identification of osteocyte-selective

proteins. Proteomics. 10:3688–3698. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lu Y, Yuan B, Qin C, Cao Z, Xie Y, Dallas

SL, McKee MD, Drezner MK, Bonewald LF and Feng JQ: The biological

function of DMP-1 in osteocyte maturation is mediated by its 57-kDa

C-terminal fragment. J Bone Miner Res. 26:331–340. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Siyam A, Wang S, Qin C, Mues G, Stevens R,

D'Souza RN and Lu Y: Nuclear localization of DMP1 proteins suggests

a role in intracellular signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

424:641–646. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ling Y, Rios HF, Myers ER, Lu Y, Feng JQ

and Boskey AL: DMP1 depletion decreases bone mineralization in

vivo: An FTIR imaging analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 20:2169–2177.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rowe PS, de Zoysa PA, Dong R, Wang HR,

White KE, Econs MJ and Oudet CL: MEPE, a new gene expressed in bone

marrow and tumors causing osteomalacia. Genomics. 67:54–68. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

David V, Martin A, Hedge AM and Rowe PSN:

Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE) is a new bone renal

hormone and vascularization modulator. Endocrinology.

150:4012–4023. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lu C, Huang S, Miclau T, Helms JA and

Colnot C: Mepe is expressed during skeletal development and

regeneration. Histochem Cell Biol. 121:493–499. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jung H, Mbimba T, Unal M and Akkus O:

Repetitive short-span application of extracellular calcium is

osteopromotive to osteoprogenitor cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med.

12:e1349–e1359. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jung H, Best M and Akkus O: Microdamage

induced calcium efflux from bone matrix activates intracellular

calcium signaling in osteoblasts via L-type and T-type

voltage-gated calcium channels. Bone. 76:88–96. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yamauchi M, Yamaguchi T, Kaji H, Sugimoto

T and Chihara K: Involvement of calcium-sensing receptor in

osteoblastic differentiation of mouse MC3T3-E1 cells. Am J Physiol

Endocrinol Metab. 288:E608–E616. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Boskey AL and Roy R: Cell culture systems

for studies of bone and tooth mineralization. Chem Rev.

108:4716–4733. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bonewald LF, Harris SE, Rosser J, Dallas

MR, Dallas SL, Camacho NP, Boyan B and Boskey A: Von Kossa staining

alone is not sufficient to confirm that mineralization in vitro

represents bone formation. Calcif Tissue Int. 72:537–547. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhou H, Wu T, Dong X, Wang Q and Shen J:

Adsorption mechanism of BMP-7 on hydroxyapatite (001) surfaces.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 361:91–96. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Magne D, Bluteau G, Lopez-Cazaux S, Weiss

P, Pilet P, Ritchie HH, Daculsi G and Guicheux J: Development of an

odontoblast in vitro model to study dentin mineralization. Connect

Tissue Res. 45:101–108. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Price PA, June HH, Hamlin NJ and

Williamson MK: Evidence for a serum factor that initiates the

re-calcification of demineralized bone. J Biol Chem.

279:19169–19180. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Erel O: A new automated colorimetric

method for measuring total oxidant status. Clin Biochem.

38:1103–1111. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sheweita SA and Khoshhal KI: Calcium

metabolism and oxidative stress in bone fractures: Role of

antioxidants. Curr Drug Metab. 8:519–525. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Shuai C, Liu G, Yang Y, Qi F, Peng S, Yang

W, He C, Wang G and Qian G: A strawberry-like Ag-decorated barium

titanate enhances piezoelectric and antibacterial activities of

polymer scaffold. Nano Energy. 74:1048252000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shuaia C, Xu Y, Feng P, Wang G, Xiong S

and Peng S: Antibacterial polymer scaffold based on mesoporous

bioactive glass loaded with in situ grown silver. Chemical

Engineering J. 374:304–345. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Maeno S, Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Morioka H,

Yatabe T, Funayama A, Toyama Y, Taguchi T and Tanaka J: The effect

of calcium ion concentration on osteoblast viability, proliferation

and differentiation in monolayer and 3D culture. Biomaterials.

26:4847–4855. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Welldon KJ, Findlay DM, Evdokiou A, Ormsby

RT and Atkins GJ: Calcium induces pro-anabolic effects on human

primary osteoblasts associated with acquisition of mature osteocyte

markers. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 376:85–92. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sugimoto T, Kanatani M, Kano J, Kaji H,

Tsukamoto T, Yamaguchi T, Fukase M and Chihara K: Effects of high

calcium concentration on the functions and interactions of

osteoblastic cells and monocytes and on the formation of

osteoclast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res. 8:1445–1452. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Dvorak MM, Siddiqua A, Ward DT, Carter DH,

Dallas SL, Nemeth EF and Riccardi D: Physiological changes in

extracellular calcium concentration directly control osteoblast

function in the absence of calciotropic hormones. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 101:5140–5145. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mullen CA, Haugh MG, Schaffler MB, Majeska

RG and McNamara LM: Osteocyte differentiation is regulated by

extracellular matrix stiffness and intercellular separation. J Mech

Behav Biomed Mater. 28:183–194. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fulzele K, Lai F, Dedic C, Saini V, Uda Y,

Shi C, Tuck P, Aronson JL, Liu X, Spatz JM, et al:

Osteocyte-Secreted Wnt Signaling Inhibitor Sclerostin Contributes

to Beige Adipogenesis in Peripheral Fat Depots. J Bone Miner Res.

32:373–384. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Uda Y, Azab E, Sun N, Shi C and Pajevic

PD: Osteocyte mechanobiology. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 15:318–325.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sarban S, Kocyigit A, Yazar M and Isikan

UE: Plasma total antioxidant capacity, lipid peroxidation, and

erythrocyte antioxidant enzyme activities in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Clin Biochem. 38:981–986.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Schroder K: NADPH oxidases in bone

homeostasis and osteoporosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 132:67–72. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ermak G and Davies KJ: Calcium and

oxidative stress: From cell signaling to cell death. Mol Immunol.

38:713–721. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ostman B, Michaëlsson K, Helmersson J,

Byberg L, Gedeborg R, Melhus H and Basu S: Oxidative stress and

bone mineral density in elderly men: Antioxidant activity of

alpha-tocopherol. Free Radic Biol Med. 47:668–673. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Banfi G, Iorio EL and Corsi MM: Oxidative

stress, free radicals and bone remodeling. Clin Chem Lab Med.

46:1550–1555. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Domazetovic V, Marcucci G, Iantomasi T,

Brandi ML and Vincenzini MT: Oxidative stress in bone remodeling:

Role of antioxidants. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 14:209–216.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Jilka RL, Noble B and Weinstein RS:

Osteocyte apoptosis. Bone. 54:264–271. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhong ZM, Bai L and Chen JT: Advanced

oxidation protein products inhibit proliferation and

differentiation of rat osteoblast-like cells via NF-kappaB pathway.

Cell Physiol Biochem. 24:105–114. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, Kurata

K, Oh-Hora M, Feng JQ, Bonewald LF, Kodama T, Wutz A, Wagner EF, et

al: Evidence for osteocyte regulation of bone homeostasis through

RANKL expression. Nat Med. 17:1231–1234. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yu C, Huang D, Wang K, Lin B, Liu Y, Liu

S, Wu W and Zhang H: Advanced oxidation protein products induce

apoptosis, and upregulate sclerostin and RANKL expression, in

osteocytic MLO-Y4 cells via JNK/p38 MAPK activation. Mol Med Rep.

15:543–550. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wang Y, Branicky R, Noë A and Hekimi S:

Superoxide dismutases: Dual roles in controlling ROS damage and

regulating ROS signaling. J Cell Biol. 217:1915–1928. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Kobayashi K, Nojiri H, Saita Y, Morikawa

D, Ozawa Y, Watanabe K, Koike M, Asou Y, Shirasawa T, Yokote K, et

al: Mitochondrial superoxide in osteocytes perturbs canalicular

networks in the setting of age-related osteoporosis. Sci Rep.

5:91482015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lushchak VI: Glutathione homeostasis and

functions: Potential targets for medical interventions. J Amino

Acids. 2012:7368372012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Nandi A, Yan LY, Jana CK and Das N: Role

of catalase in oxidative stress- and age-associated degenerative

diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:96130902019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Miyagawa K, Yamazaki M, Kawai M, Nishino

J, Koshimizu T, Ohata Y, Tachikawa K, Mikuni-Takagaki Y, Kogo M,

Ozono K and Michigami T: Dysregulated gene expression in the

primary osteoblasts and osteocytes isolated from hypophosphatemic

Hyp mice. PLoS One. 9:e938402014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang X, Wang S, Li C, Gao T, Liu Y,

Rangiani A, Sun Y, Hao J, George A, Lu Y, et al: Inactivation of a

novel FGF23 regulator, FAM20C, leads to hypophosphatemic rickets in

mice. PLoS Genet. 8:e10027082012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bellido T: Osteocyte-driven bone

remodeling. Calcif Tissue Int. 94:25–34. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Martin A, Liu S, David V, Li H, Karydis A,

Feng JQ and Quarles LD: Bone proteins PHEX and DMP1 regulate

fibroblastic growth factor Fgf23 expression in osteocytes through a

common pathway involving FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling. FASEB J.

25:2551–2562. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lavi-Moshayoff V, Wasserman G, Meir T,

Silver J and Naveh-Many T: PTH increases FGF23 gene expression and

mediates the high-FGF23 levels of experimental kidney failure: A

bone parathyroid feedback loop. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

299:F882–F889. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gluhak-Heinrich J, Pavlin D, Yang W,

MacDougall M and Harris SE: MEPE expression in osteocytes during

orthodontic tooth movement. Arch Oral Biol. 52:684–690. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yang W, Lu Y, Kalajzic I, Guo D, Harris

MA, Gluhak-Heinrich J, Kotha S, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ, Rowe DW, et

al: Dentin matrix protein 1 gene cis-regulation: use in osteocytes

to characterize local responses to mechanical loading in vitro and

in vivo. J Biol Chem. 280:20680–20690. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Gluhak-Heinrich J, Ye L, Bonewald LF, Feng

JQ, MacDougall M, Harris SE and Pavlin D: Mechanical loading

stimulates dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) expression in osteocytes

in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 18:807–817. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Bonewald LF: The role of the osteocyte in

bone and nonbone disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 46:1–18.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kulkarni RN, Bakker AD, Everts V and

Klein-Nulend J: Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis by mechanically

loaded osteocytes: involvement of MEPE. Calcif Tissue Int.

87:461–468. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Xiong J, Onal M, Jilka RL, Weinstein RS,

Manolagas SC and O'Brien CA: Matrix-embedded cells control

osteoclast formation. Nat Med. 17:1235–1241. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang K, Barragan-Adjemian C, Ye L, Kotha

S, Dallas M, Lu Y, Zhao S, Harris M, Harris SE, Feng JQ and

Bonewald LF: E11/gp38 selective expression in osteocytes:

Regulation by mechanical strain and role in dendrite elongation.

Mol Cell Biol. 26:4539–4552. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zakhary I, Alotibi F, Lewis J, ElSalanty

M, Wenger K, Sharawy M and Messer RLW: Inherent physical

characteristics and gene expression differences between alveolar

and basal bones. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol.

122:35–42. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|