Introduction

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are induced by stressful

environments such as high temperature or pathological conditions

(1). HSPs are generally

characterized as molecular chaperones that prevent protein

aggregation and restore protein homeostasis (1). Based on their molecular weight, HSPs

are now divided into seven categories as follows: HSPA family

(HSP70), HSPH family (HSP110), HSPC family (HSP90), HSPD/E family

(HSP60/HSP10), HSPB family (small HSPs), DNAJ (HSP40) and

chaperonin containing tailless complex polypeptide 1 or tailless

complex polypeptide 1 ring complex (1). Among these groups, HSP70 is expressed

in unstressed cells and acts as an ATP-dependent molecular

chaperone (2). HSP70 has been

reported to serve an important role in promoting protein

homeostasis and folding, and survival of cells under stressful

conditions (3). Regarding the

functions of HSP70 in bone metabolism, HSP70 increases both

alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization of human

mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) (4). HSP70 also increases the expression of

osteogenic markers such as runt-related transcription factor 2

(Runx2) and Osterix in hMSCs, which promotes osteoblastic

differentiation (4). In bone

cells, we previously reported that HSP70 was highly expressed in

mouse calvaria-derived MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells (5). As for the functions of HSP70, we

showed that TGF-β VEGF release was downregulated by HSP70 in

MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells (6).

However, the functions of HSP70 in bone metabolism, especially in

osteoblasts, have not yet been fully elucidated.

Bone is a dynamic organ, in which osteoclasts

reabsorb calcified bone and osteoblasts subsequently form new bone.

These processes, termed bone remodeling, are tightly regulated to

maintain proper bone mass under physiological conditions. Imbalance

of bone formation and resorption leads to metabolic bone disorders,

including osteoporosis (7).

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a multifunctional cytokine that is released

from numerous types of cells and serves important roles in

biological processes, such as immunity, hematopoiesis and bone

metabolism (8). During bone

metabolism, IL-6 activates signal transduction pathways in

osteoblasts via the gp130 receptor and induces the expression of

receptor-activator of nuclear factor-κB-ligand (RANKL) (9). RANKL attaches to RANK expressed on

osteoclast precursors and induces differentiation into mature

osteoclasts (9). Therefore, IL-6

has been generally considered as a bone resorptive cytokine. By

contrast, it has been reported that IL-6 is essential in the

process of fracture healing (10,11).

Therefore, IL-6 is known as an osteotropic factor that may modulate

bone formation under bone turnover-accelerating conditions

(12). Basic fibroblast growth

factor (bFGF or FGF-2) is the most abundant FGF and is known as an

angiogenic factor (13). During

bone metabolism, bFGF serves crucial roles in bone regeneration and

fracture repair (12). bFGF

increases vascularization during the early stages of fracture

healing and promotes the proliferation and differentiation of bone

marrow stromal cells (14). We

previously reported that bFGF stimulated IL-6 release through p38

MAPK in mouse MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells (15,16).

However, the roles of HSP70 in the bFGF-stimulated IL-6 release in

osteoblasts are still unknown. The present study evaluated whether

HSP70 serves a role in the bFGF-stimulated release of IL-6 and the

mechanism involved in this, using osteoblastic cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

bFGF was purchased from Roche Diagnostics GmbH.

HSP70 inhibitors, VER-155008 and YM-08, were purchased from

MilliporeSigma. SB203580 (cat. no. 559389) were purchased from

Calbiochem; Merck KGaA. Phosphorylated (p)-p38 MAPK (cat. no.

4511S) and p38 MAPK (cat. no. 9212S) antibodies were purchased from

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. HSP70 antibodies (cat. np.

ADI-SPA-812) were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. GAPDH

antibodies (cat. no. sc-25778) were purchased from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc. Peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibodies

(cat. no. 5220-0336; SeraCare Life Sciences, Inc.) and

peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibodies (cat. no. #7076; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) were used as secondary antibodies. An

ECL western blot detection system (cat. no. RPN2106) was purchased

from Cytiva. Mouse (cat. no. M6000B) and human (cat. no. D6050)

IL-6 ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems, Inc.

Cell culture

Cloned MC3T3-El osteoblast-like cells established

from neonatal mouse calvaria (17)

were donated by Dr M Kumegawa (Department of Dentistry, Graduate

School of Dentistry, Meikai University, Sakado, Japan), and

maintained in α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM; MilliporeSigma)

containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific

Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2−95%

air, as previously described (18). For western blot analyses, the

MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells were seeded into 90-mm diameter dish

plates (2×105 cells/dish) in α-MEM supplemented with 10%

FBS. For ELISA and RT-PCR analysis, the cells were seeded into

35-mm diameter dish plates (5×104 cells/dish) in α-MEM

supplemented with 10% FBS. The culture medium was changed for α-MEM

supplemented with 0.3% FBS after 5 days. These cells were used for

the experiments after 48 h.

Normal human osteoblasts, which were originally

derived from human samples from patients who provided informed

consent, were purchased from Cambrex Bio Science Rockland, Ltd.

(cat. no. CC-2538; passage 2) and used in the present study. The

cultured normal human osteoblasts were cultured under the same

conditions as those used for mouse MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells.

These normal human osteoblasts were seeded into 35-mm diameter dish

plates (5×104 cells/dish) in α-MEM supplemented with 10%

FBS. The medium was changed to α-MEM supplemented with 0.3% FBS

after 17 days. These cells were used for ELISA experiments after a

further 48 h (19).

Measurement of IL-6

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells and normal human

osteoblasts were pre-treated with 1, 10 and 30 µM VER-155008 in 1

ml α-MEM supplemented with 0.3% FBS at 37°C for 60 min. These cells

were subsequently treated with 30 ng/ml bFGF or vehicle and

incubated for 48 h without washing away the VER-155008.

Pre-incubation with 10 µM SB203580 was performed for 60 min prior

to the VER-155008 stimulation. The conditioned medium was collected

at the end of the incubation, and the IL-6 concentration in the

medium was assessed using mouse and human IL-6 ELISA kits (16,19).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR analysis

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells were pre-treated with

30 µM VER-155008 for 60 min, and then stimulated with 30 ng/ml bFGF

in α-MEM supplemented with 0.3% FBS for 3 h. Total RNA was isolated

using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fischer Scientific, Inc.)

and reverse transcribed into cDNA at 37°C for 60 min using an

Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase kit (Qiagen, Inc.). RT-qPCR was

performed using a Light Cycler system with Fast Start DNA Master

SYBR Green I according to the manufacturer's standard protocol

(Roche Diagnostics). Samples were subjected to the following PCR

thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min,

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 sec, annealing

at 60°C for 5 sec and elongation at 72°C for 7 sec. IL-6 and GAPDH

primers were purchased from Takara Bio, Inc., with sequences as

follows: IL-6 forward (F), 5′-CCACTTCACAAGTCGGAGGCTTA-3′ and

reverse (R), 5′-GCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATAC-3′; and GAPDH F,

5′-AACGACCCCTTCATTGAC-3′ and R, 5′-TCCACGACATACTCAGCAC-3′. All

measurements were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(20).

Western blotting

MC3T3-E1 cells were pre-incubated with 30 µM of

VER-155008 or 10 and 20 µM YM-08, and then stimulated using 30

ng/ml bFGF in α-MEM containing 0.3% FBS for 10 min. For western

blot analysis, MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells were rinsed twice

with phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed and sonicated in 800 µl

lysis buffer containing 62.5 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM dithiothreitol, 2%

SDS and 10% glycerol. Proteins were separated on a 10% gel using

SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (21). Although the mass of protein per

lane was not quantified, the same number of cells (2×105

cells/dish) was seeded in each dish. The days of treatment,

conditions, and lysis buffer dose were also the same for each dish.

Lysates (10 µl) were applied per lane of all SDS-PAGE gels. The

membrane was subsequently incubated at 4°C overnight with primary

antibodies against p38 MAPK, p-p38 MAPK, HSP70 and GAPDH (1:1,000)

followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary antibodies

(1:1,000) at room temperature for 1 h. Following the detection of

specific antibodies, the same membranes were stripped with WB

stripping solution (cat. no. 46430, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.)

for 15 min at room temperature and reprobed. An ECL western

blotting kit was used for the detection as previously described

(22).

Densitometric analysis

Densitometric analysis of the western blots was

performed using a scanner and ImageJ analysis software (version

1.48; National Institutes of Health). The phosphorylated protein

levels were calculated as follows: The background subtracted signal

intensity of each phosphorylation signal was normalized to the

respective intensity of total protein and plotted as the fold

increase compared with that in the control cells without

stimulation.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using Mini StatMate (version

2.01; ATMS Co., Ltd.). ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's significant

difference test was used for multiple comparisons. All measurements

were performed in triplicate from dependent cell preparations and

analyzed. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

VER-155008 increases the

bFGF-stimulated IL-6 release in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells and

normal human osteoblasts

We previously reported that HSP70 was highly

expressed in unstimulated MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells (5,23).

In the present study, the roles of HSP70 in bFGF-stimulated IL-6

release using VER-155008, a HSP70 inhibitor (24), were analyzed in MC3T3-E1

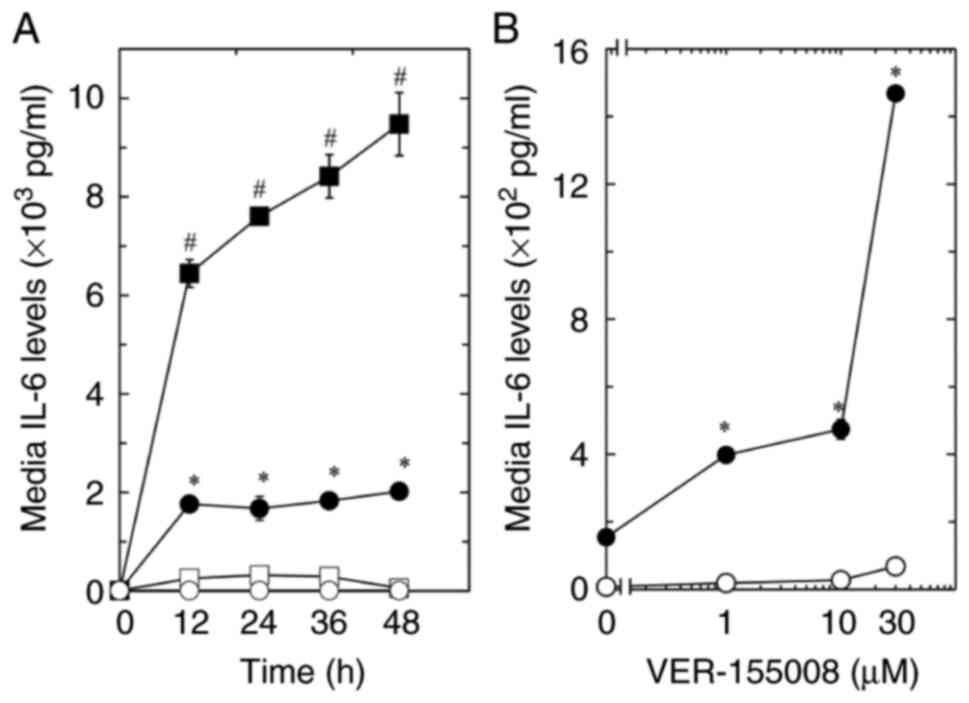

osteoblast-like cells. As a result, the bFGF-stimulated release of

IL-6 was significantly increased by VER-155008 at each time point

compared with the respective control (Fig. 1A). By contrast, the IL-6 release

was not affected by treatment with VER-155008 alone. Furthermore,

the effects of VER-155008 on the bFGF-induced release of IL-6

tended to be dose-dependent in the range between 1 and 30 µM

(Fig. 1B).

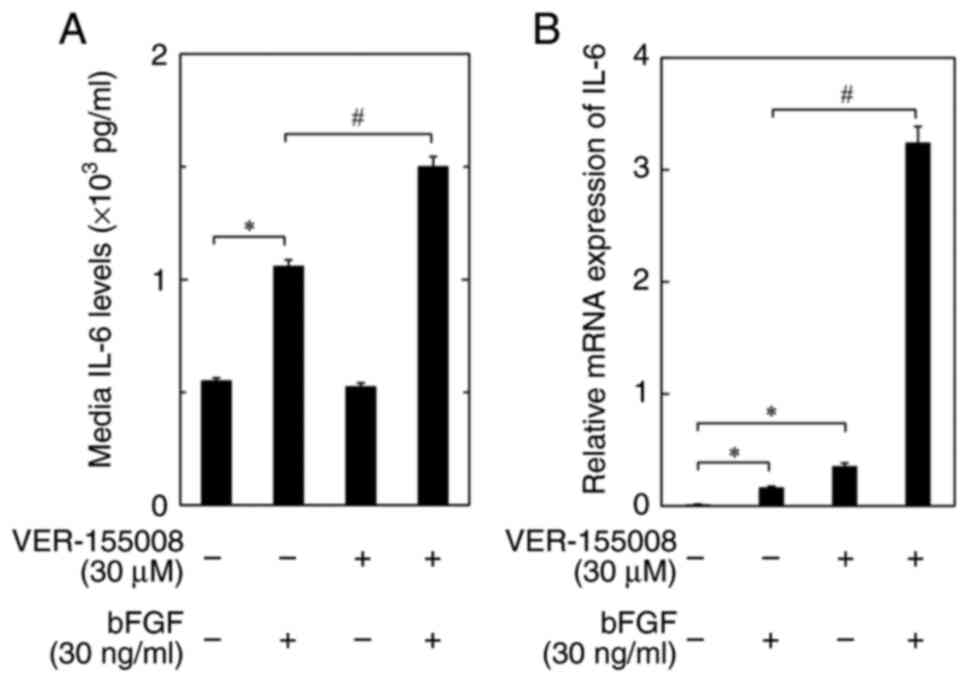

Normal human osteoblasts were used to analyze the

role of HSP70 inhibitors in different osteoblast types. As a

result, it was confirmed that IL-6 release was significantly

increased by bFGF in normal human osteoblasts compared with the

control. Moreover, bFGF-stimulated release of IL-6 was

significantly enhanced by VER-155008 compared with the bFGF only

group. VER-155008 alone did not significantly affect the release of

IL-6 in normal human osteoblasts (Fig.

2A).

VER-155008 enhances the bFGF-induced

expression levels of IL-6 mRNA in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like

cells

To evaluate whether the enhancing effect of the

HSP70 inhibitor on the bFGF-stimulated release of IL-6 in MC3T3-E1

osteoblastic cells was mediated through transcriptional events, the

effect of VER-155008 on the bFGF-induced expression of IL-6 mRNA

was assessed. It was demonstrated that VER-155008 significantly

increased the mRNA expression levels of IL-6 compared with the bFGF

only group (Fig. 2B).

VER-155008 and YM-08 stimulate

bFGF-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in MC3T3-E1

osteoblast-like cells

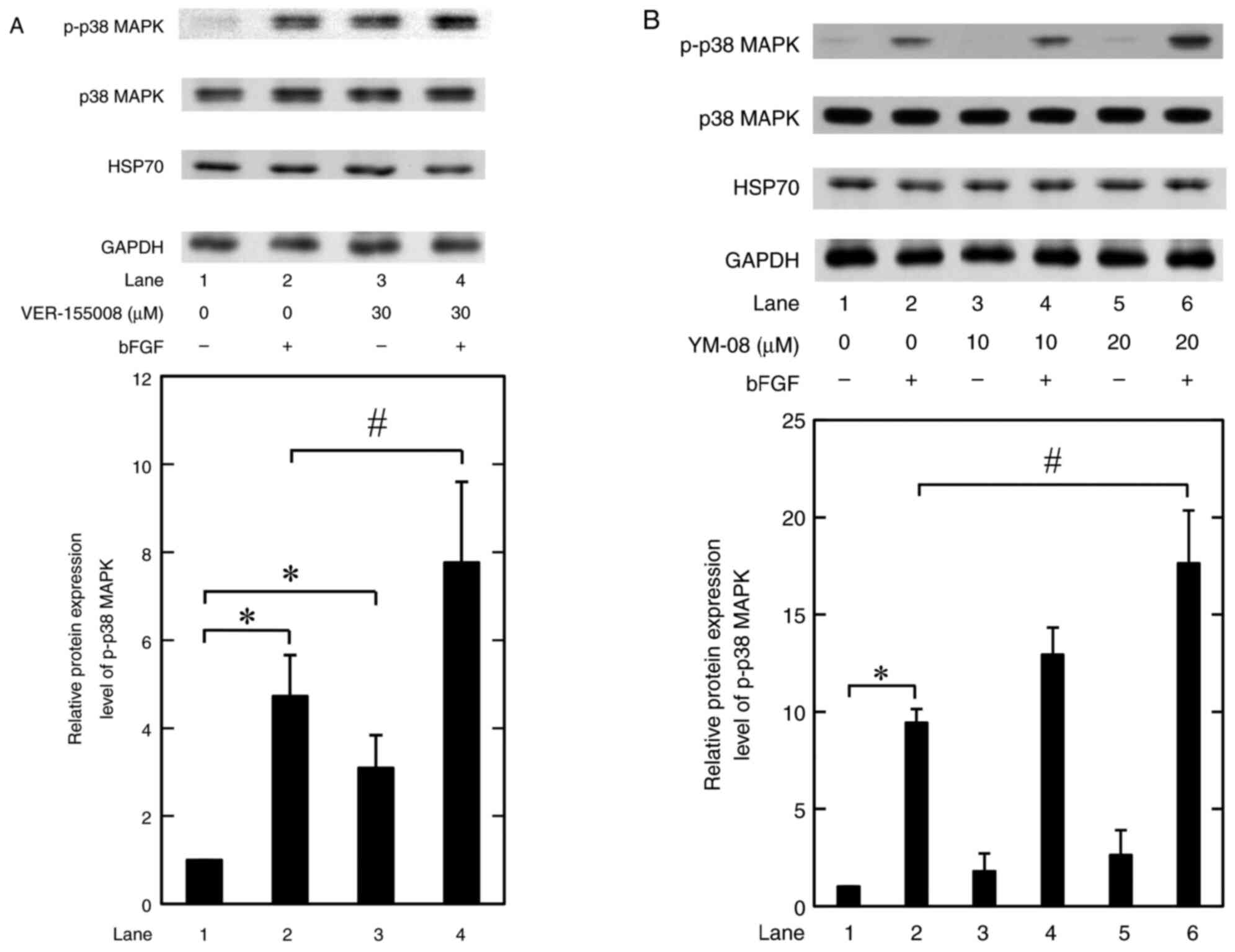

We have previously reported that P38 MAPK activation

is related to the bFGF-stimulated release of IL-6 in MC3T3-E1

osteoblastic cells (16).

Therefore, the effects of HSP70 inhibitors on the bFGF-induced

phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was assessed in MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic

cells. VER-155008 at 30 mM significantly increased the

phosphorylation levels of p38 MAPK induced by bFGF compared with

the bFGF only group. Furthermore, 30 mM VER-155008 alone

significantly increased the levels of p38 MAPK phosphorylation

compared with the untreated control (Fig. 3A). YM-08, another type of HSP70

inhibitor (25), significantly

increased the bFGF-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, compared

with the bFGF only group, at 20 mM; however it had no significant

effect on the phosphorylation when used alone (Fig. 3B).

Neither VER-155008 nor YM-08 affect

the expression of HSP70 with or without bFGF stimulation in

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells

We previously reported that HSP70 was highly

expressed in unstimulated MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells (5,23).

Whether VER-155008 and YM-08 with or without bFGF could affect the

HSP70 expression in these cells was assessed in the present study.

VER-155008 and YM-08 did not significantly affect the expression of

HSP70 with or without bFGF stimulation (Fig. 3).

SB203580 inhibits the amplification of

bFGF-elicited IL-6 release by VER-155008 in MC3T3-E1

osteoblast-like cells

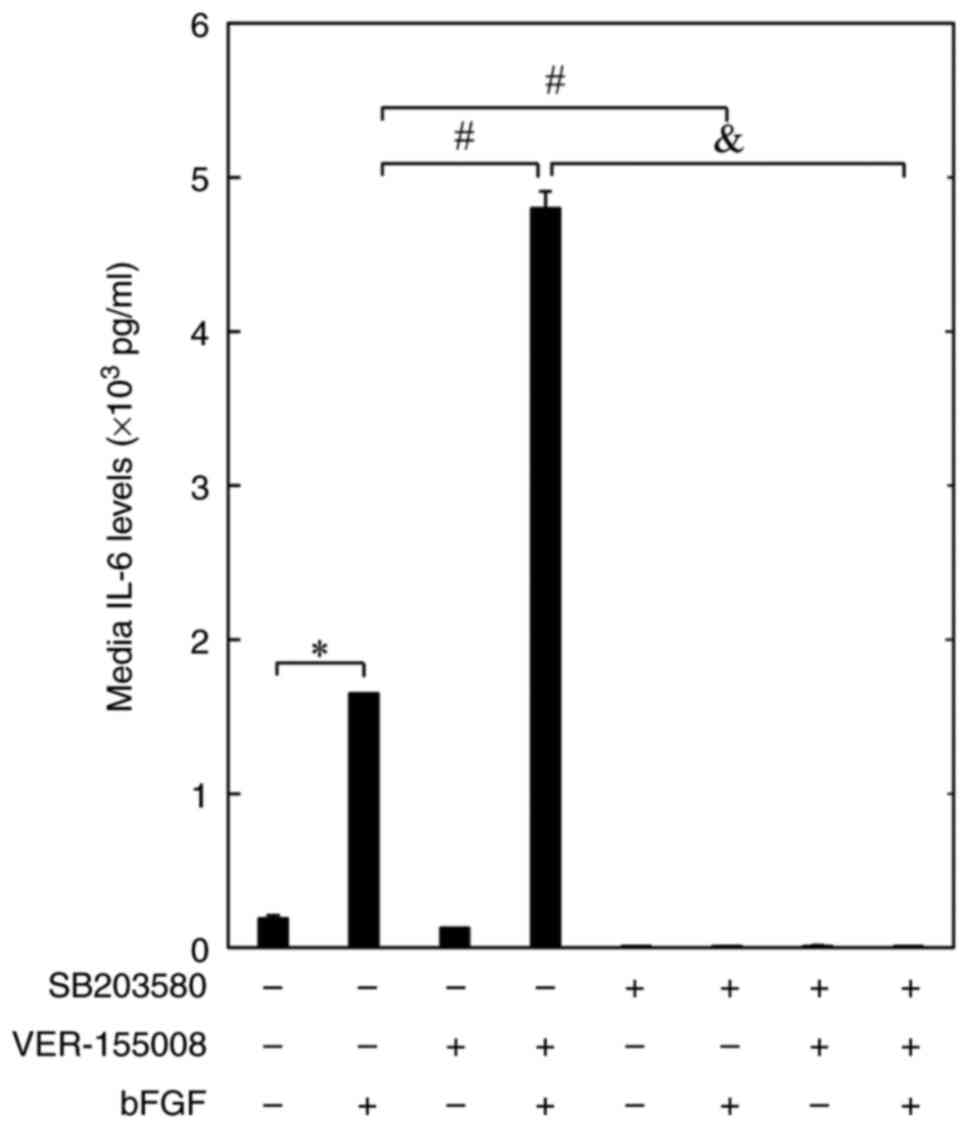

Finally, the effect of SB203580, a specific

inhibitor of p38 MAPK (26), on

the amplification of the bFGF-elicited release of IL-6 by

VER-155008 was assessed in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells. The

results of the present study confirmed those of a previous report

showing that SB203580 significantly inhibited the bFGF-elicited

release of IL-6 (16). SB203580

almost completely inhibited the amplifying effects of VER-155008 on

the bFGF-stimulated release of IL-6 in MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the HSP70

inhibitor, VER-155008, significantly increased the bFGF-induced

release of IL-6 in mouse MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells and normal

human osteoblasts. Furthermore, VER-155008 significantly increased

the mRNA expression levels of IL-6 induced by bFGF in MC3T3-E1

osteoblastic cells, which suggested that the enhancing effects of

VER-155008 on the bFGF-induced release of IL-6 may be mediated

through a transcriptional event. Our previous study demonstrated

that HSP70 inhibitors, VER-155008 and YM-08, significantly

increased TGF-β-stimulated VEGF release and the TGF-β-induced mRNA

expression levels of VEGF in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells

(6). These results indicated that

HSP70 inhibitors were involved in VEGF synthesis, as well as IL-6

synthesis, in MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells.

Regarding the intracellular signaling exerted by

bFGF in osteoblasts, our previous study demonstrated that bFGF

elicits the synthesis of IL-6 via the activation of p38 MAPK in

MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells (16).

In the present study, both VER-155008 and YM-08 significantly

increased the bFGF-elicited phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, which

suggested that HSP70 inhibition upregulated bFGF-elicited

activation of p38 MAPK in these cells. The inhibitors did not

significantly affect the protein expression levels of HSP70, either

with or without bFGF in these cells. Therefore, it is likely that

the upregulation by HSP70 inhibitors of the activation of p38 MAPK

causes the enhancement of IL-6 synthesis induced by bFGF in

MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells. Treatment with VER-155008 alone, at 30

µM, caused a significant increase in the phosphorylation of p38

MAPK, which might be due to non-specific effects other than HSP70

inhibition. MAP kinase kinase kinases (MAP3Ks), including apoptosis

signal-regulating kinase-1 (ASK-1) and MEK kinase (MEKK) are

activated in response to numerous inflammatory cytokines. MAP3Ks

activate MAP kinase kinases such as MKK3/6, and MKK3/6 subsequently

activates p38 MAPK (27). HSP70 is

known as a molecular chaperone that interacts with client proteins

and modulates intracellular signal transduction. The inhibition of

HSP70 chaperone function can cause inactivation and degradation of

HSP70-dependent client proteins. The present study demonstrated

that the HSP70 inhibitor VER-155008 (30 µM) significantly enhanced

the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK. Although this remains to be

confirmed as a genuine effect of the inhibitor, this result

indicated that the activation of p38 MAPK could be elicited by

HSP70 silencing. Therefore, HSP70 might downregulate p38 MAPK

signaling through the chaperone effect on the upstream kinase(s)

such as ASK-1, MEKK and MKK3/6 in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like

cells.

HSP70 is highly expressed in osteoblasts (5,23).

HSP70 serves a central role in protein homeostasis by folding

proteins into the correct form as a molecular chaperone and also

prevents unfolded protein aggregation by binding to client proteins

(28). In bone cells, it has been

previously reported that HSP70 increases alkaline phosphatase

activity and promotes hMSC mineralization, and that it also

significantly upregulates the expression of Runx2 and Osterix under

osteogenic induction conditions (29). Furthermore, overexpression of HSP

family A member 1A, which encodes the cognate HSP70, stimulates

osteoblastic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells via the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (30). Our previous study demonstrated that

HSP70 inhibitors suppress the migration of MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like

cells induced by insulin-like growth factor-I or epidermal growth

factor (31,32). However, the precise mechanism by

which HSP70, by itself or together with client proteins, influences

bone metabolism has not yet been fully elucidated, and the exact

functions of HSP70 in osteoblasts have not been fully reported. Our

previous study reported that TGF-β-stimulated VEGF synthesis is

upregulated by HSP70 inhibitors through activation of p38 MAPK in

MC3T3-E1 cells (6). Therefore, the

action of HSP70 against p38 MAPK in bFGF-stimulated MC3T3-E1

osteoblastic cells in this study seemed to be similar to the effect

of HSP70 on p38 MAPK in TGF-β-stimulated same cells in our previous

study. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that SB203580 almost

completely inhibited the enhancement by VER-155008 of the

bFGF-stimulated release of IL-6. Our previous study reported that

SB203580 inhibited the enhancement, by VER-155008 and YM-08, of

TGF-β-stimulated VEGF release (6).

These results strongly indicated the involvement of p38 MAPK in the

increased release of IL-6 and VEGF. Taking these findings into

account, it is likely that HSP70 negatively regulates

bFGF-stimulated synthesis of IL-6 as well as the TGF-β-stimulated

synthesis of VEGF in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells, and that the

effects of HSP70 are exerted by the inhibition of p38 MAPK

activation. Furthermore, our recent study reported that HSP70

inhibitors upregulated prostaglandin E1

(PGE1)-stimulated synthesis of IL-6 through p38 MAPK in

MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells (33).

Although their receptors are quite different, the inhibition of

HSP70 can cause upregulation of p38 MAPK in osteoblasts stimulated

by both bFGF and PGE1, which results in an increase in

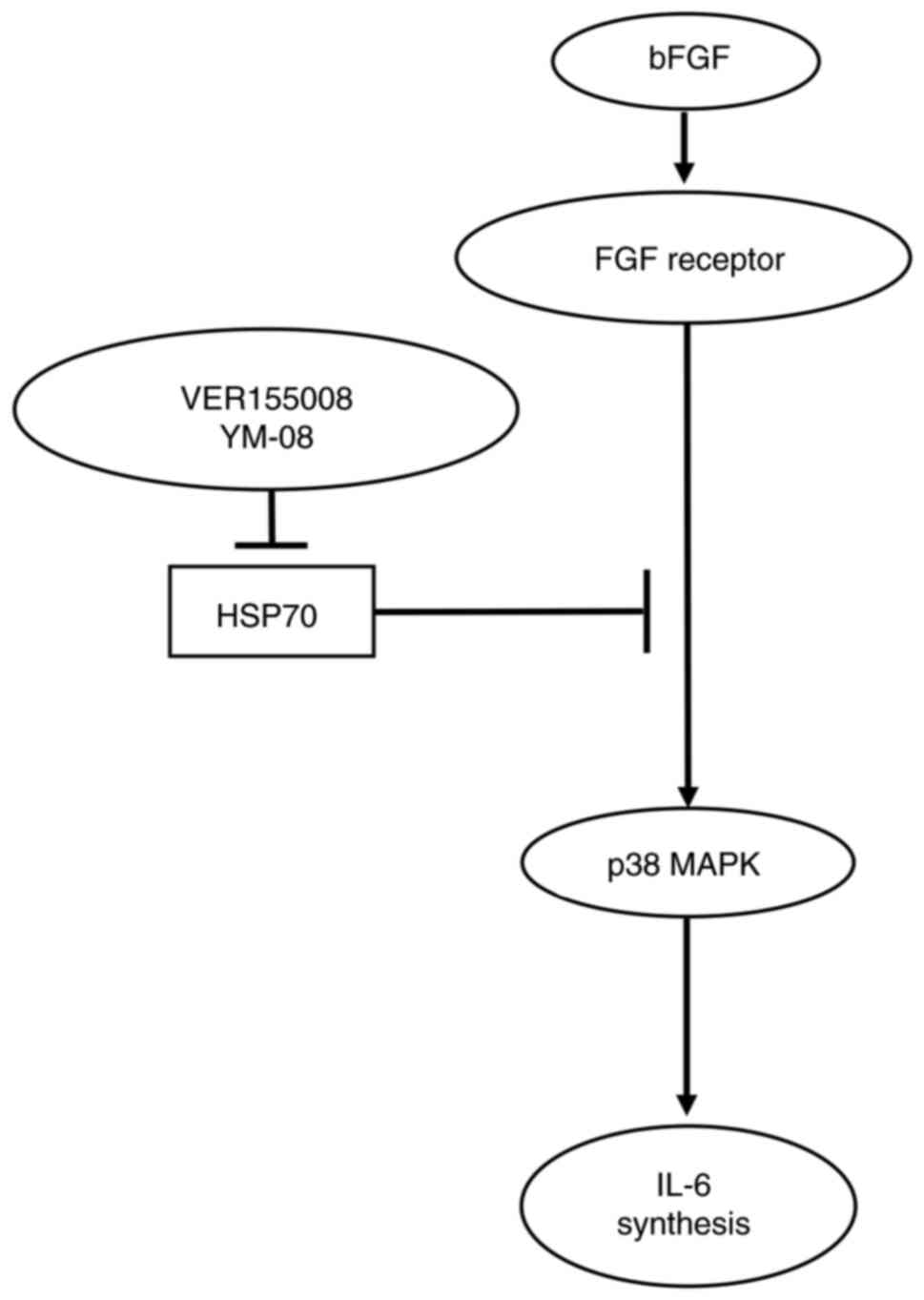

IL-6 synthesis. The potential mechanisms underlying regulation of

bFGF-stimulated IL-6 release by HSP70 in osteoblasts is presented

in Fig. 5. As HSP70 is an

essential factor for cell survival, the knockdown of HSP70 by small

interfering (si)RNA for >24 h is toxic to MC3T3-E1 cells, which

has been indicated in our previous paper (6), but the results have not been fully

published. The reason why only HSP70 siRNA, but not the HSP70

inhibitors, was toxic to cells was not reported. However, it can be

hypothesized that the siRNA might suppress HSP70 function more

completely than the inhibitors, which were demonstrated in the

present study to not affect the expression of HSP70.

In bone metabolism, the multifunctional cytokine

IL-6 is recognized as an osteotropic factor, which promotes bone

formation under conditions of increased bone turnover, including

during fracture healing (10,11).

bFGF is known to be highly expressed during fracture healing as an

angiogenic factor, which serves a crucial role in bone regeneration

(13). However, HSP70 is

constitutively expressed in non-stressed cells, including

osteoblasts (2). Therefore, HSP70

may play an important role in bone metabolism by regulating the

effects of bFGF and IL-6. The amplifying effects of the HSP70

inhibitors on the bFGF-induced release of IL-6 in osteoblast-like

cells demonstrated in the present study indicated that the

suppression of HSP70 might be a novel method to promote bone

regeneration under conditions such as fracture healing.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

suggested that HSP70 inhibitor amplified the bFGF-induced release

of IL-6 in osteoblasts and that the inhibitory effect of HSP70 was

exerted by inhibition of the activation of p38 MAPK.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Yumiko Kurokawa

(Department of Pharmacology, Gifu University Graduate School of

Medicine, Gifu, Japan) for providing technical assistance. The

authors would also thank Dr Masayoshi Kumegawa (Department of

Dentistry, Graduate School of Dentistry, Meikai University, Sakado,

Japan) for donating cloned MC3T3-El osteoblast-like cells.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific

Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science

and Technology of Japan (grant nos. 19K09370 and 19K18471) and the

Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from the National Center

for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Japan (grant nos. 20-12 and

21-1).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

GK and HT performed data analysis and

interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. GK and HT confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. TH and RMN collated and analyzed

the data. OK and HT conceived and designed the study, and wrote the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hendrick JP and Hartl FU: Molecular

chaperone functions of heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Biochem.

62:349–384. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hartl FU, Bracher A and Hayer-Hartl M:

Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature.

475:324–332. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Murphy ME: The HSP70 family and cancer.

Carcinogenesis. 34:1181–1188. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li C, Sunderic K, Nicoll SB and Wang S:

Downregulation of heat shock protein 70 impairs osteogenic and

chondrogenic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci

Rep. 8:5532018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang X, Tokuda H, Hatakeyama D, Hirade K,

Niwa M, Ito H, Kato K and Kozawa O: Mechanism of simvastatin on

induction of heat shock protein in osteoblasts. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 415:6–13. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sakai G, Tokuda H, Fujita K, Kainuma S,

Kawabata T, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Kozawa O and Otsuka T: Heat

shock protein 70 negatively regulates TGF-β-stimulated VEGF

synthesis via p38 MAP kinase in osteoblasts. Cell Physiol Biochem.

44:1133–1145. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kular J, Tickner J, Chim SM and Xu J: An

overview of the regulation of bone remodelling at the cellular

level. Clin Biochem. 45:863–873. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kishimoto T, Akira S, Narazaki M and Taga

T: Interleukin-6 family of cytokines and gp130. Blood.

86:1243–1254. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sims NA: Cell-specific paracrine actions

of IL-6 family cytokines from bone, marrow and muscle that control

bone formation and resorption. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 79:14–23.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Prystaz K, Kaiser K, Kovtun A,

Haffner-Luntzer M, Fischer V, Rapp AE, Liedert A, Strauss G,

Waetzig GH, Rose-John S and Ignatius A: Distinct effects of IL-6

classic and trans-signaling in bone fracture healing. Am J Pathol.

188:474–490. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Franchimont N, Wertz S and Malaise M:

Interleukin-6: An osteotropic factor influencing bone formation?

Bone. 37:601–606. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Roodman GD: Perspectives: Interleukin-6:

An osteotropic factor? J Bone Miner Res. 7:475–478. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Charoenlarp P, Rajendran AK and Iseki S:

Role of fibroblast growth factors in bone regeneration. Inflamm

Regen. 37:102017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Luong LN, Ramaswamy J and Kohn DH: Effects

of osteogenic growth factors on bone marrow stromal cell

differentiation in a mineral-based delivery system. Biomaterials.

33:283–294. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kozawa O, Suzuki A and Uematsu T: Basic

fibroblast growth factor induces interleukin-6 synthesis in

osteoblasts: Autoregulation by protein kinase C. Cell Signal.

9:463–468. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kozawa O, Tokuda H, Matsuno H and Uematsu

T: Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in basic

fibroblast growth factor-induced interleukin-6 synthesis in

osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 74:479–485. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sudo H, Kodama HA, Amagai Y, Yamamoto S

and Kasai S: In vitro differentiation and calcification in a new

clonal osteogenic cell line derived from newborn mouse calvaria. J

Cell Biol. 96:191–198. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kozawa O, Suzuki A, Tokuda H and Uematsu

T: Prostaglandin F2alpha stimulates interleukin-6 synthesis via

activation of PKC in osteoblast-like cells. Am J Physiol. 272((2 Pt

1)): E208–E211. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kondo A, Otsuka T, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R,

Kuroyanagi G, Mizutani J, Wada I, Kozawa O and Tokuda H: Inhibition

of SAPK/JNK leads to enhanced IL-1-induced IL-6 synthesis in

osteoblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 535:227–233. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Laemmli UK: Cleavage of structural

proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4.

Nature. 227:680–685. 1970. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kato K, Ito H, Hasegawa K, Inaguma Y,

Kozawa O and Asano T: Modulation of the stress-induced synthesis of

hsp27 and alpha B-crystallin by cyclic AMP in C6 rat glioma cells.

J Neurochem. 66:946–950. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kozawa O, Niwa M, Hatakeyama D, Tokuda H,

Oiso Y, Matsuno H, Kato K and Uematsu T: Specific induction of heat

shock protein 27 by glucocorticoid in osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem.

86:357–364. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Schlecht R, Scholz SR, Dahmen H, Wegener

A, Sirrenberg C, Musil D, Bomke J, Eggenweiler HM, Mayer MP and

Bukau B: Functional analysis of Hsp70 inhibitors. PLoS One.

8:e784432013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Miyata Y, Li X, Lee HF, Jinwal UK,

Srinivasan SR, Seguin SP, Young ZT, Brodsky JL, Dickey CA, Sun D

and Gestwicki JE: Synthesis and initial evaluation of YM-08, a

blood-brain barrier permeable derivative of the heat shock protein

70 (Hsp70) inhibitor MKT-077, which reduces tau levels. ACS Chem

Neurosci. 4:930–939. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, Meier R, Cohen

P, Gallagher TF, Young PR and Lee JC: SB203580 is a specific

inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular

stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 364:229–233. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Thouverey C and Caverzasio J: Focus on the

p38 MAPK signaling pathway in bone development and maintenance.

Bonekey Rep. 4:7112015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mayer MP and Bukau B: Hsp70 chaperones:

Cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci.

62:670–684. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen E, Xue D, Zhang W, Lin F and Pan Z:

Extracellular heat shock protein 70 promotes osteogenesis of human

mesenchymal stem cells through activation of the ERK signaling

pathway. FEBS Lett. 589((24 Pt B)): 4088–4096. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang W, Xue D, Yin H, Wang S, Li C, Chen

E, Hu D, Tao Y, Yu J, Zheng Q, et al: Overexpression of HSPA1A

enhances the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Sci Rep. 6:276222016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kawabata T, Tokuda H, Sakai G, Fujita K,

Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Kuroyanagi G, Otsuka T and Kozawa O: HSP70

inhibitor suppresses IGF-I-stimulated migration of osteoblasts

through p44/p42 MAP kinase. Biomedicines. 6:1092018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kawabata T, Otsuka T, Fujita K, Sakai G,

Kim W, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Kuroyanagi G, Kozawa O and Tokuda H:

HSP70 inhibitors reduce the osteoblast migration by epidermal

growth factor. Curr Mol Med. 18:486–495. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kuroyanagi G, Tachi J, Fujita K, Kawabata

T, Sakai G, Nakashima D, Kim W, Tanabe K, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R,

Otsuka T, et al: HSP70 inhibitors upregulate prostaglandin

E1-induced synthesis of interleukin-6 in osteoblasts. PLoS One.

17:e02791342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|