Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease

in the world, with a prevalence of ~10% of the population (1). The characteristic structural changes

include synovial inflammation, a loss of articular cartilage,

subchondral bone changes, meniscal injuries, and tendon and

ligament degeneration (2). OA is

the leading cause of joint pain, loss of function and disability in

older adults, with the knee being the most commonly affected joint

(3). The pathogenesis of OA has

not yet been clarified, but previous studies have suggested that

inflammation, pyroptosis and apoptosis serve important roles in the

progression of OA (3,4).

The NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)

inflammasome has become the most widely studied inflammasome in

recent years, and it can be activated by various pathogenic events,

such as reactive oxygen species generation, mitochondrial

dysfunction and numerous types of pathogens, such as bacteria and

viruses (5). The NLRP3

inflammasome has an important role in inflammatory bowel disease,

cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease and

lung disease (5–7). Previous studies have shown that the

NLRP3 inflammasome is widely involved in the development of OA

(8,9). Therefore, targeting the NLRP3

inflammasome may be considered an important strategy for the

treatment of OA. For example, in chondrocytes, icariin antagonizes

NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated activation of caspase-1 signaling,

thereby attenuating inflammation during osteoporosis (10). In addition, the use of n-3

polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA)-enriched diets has been shown to

protect mice from obesity-associated post-traumatic OA, and an

in-depth study revealed that this phenomenon is related to the

inhibition of NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling by PUFAs (11).

Tributyltin (TBT) was once widely used as an

antifouling paint for ships; however, it was subsequently found to

cause serious harm to marine organisms, especially mollusks, and it

was thus banned globally in 2003 (12). Owing to its long-term residue, even

after a long period of time, TBT still exists in seawater and

sediments; it can therefore accumulate in marine organisms and is

still present after cooking, thus suggesting that the consumption

of seafood may be a potential TBT hazard (13,14).

TBT chloride (TBTC) is the main form of TBT present in water.

Studies have shown that TBTC is an endocrine disruptor in mammals

and can affect the reproductive function of animals (12,15).

However, the understanding of the effects of TBTC on the articular

cartilage remains limited. The present study explored the effects

and molecular mechanisms of TBTC on chondrocytes in vitro

and in vivo to reveal the potential effects of TBTC on joint

damage.

Materials and methods

Rat chondrocyte culture

Rat primary chondrocytes (cat. no. CP-R087) were

obtained from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. The

cells were suspended in rat chondrocyte complete medium (cat. no.

CM-R087; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and 100 U/ml penicillin-100 µg/ml streptomycin

(penicillin-streptomycin liquid; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), and were incubated at 37°C in 5%

CO2. The cells were divided into control,

low-concentration (25 nM) TBTC (MilliporeSigma),

medium-concentration (50 nM) TBTC and high-concentration (100 nM)

TBTC groups at 37°C for 24 h. The experiments were repeated three

times for each group.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

The cells were resuspended and seeded in 96-well

plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well. When the cells

reached 50–60% confluence, the medium was discarded, and TBTC was

added at final concentrations of 0, 25, 50 and 100 nM for 24 h at

37°C. The cells were then incubated with CCK-8 reagent (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at 37°C and

the absorbance values were determined at 450 nm.

Western blotting

The cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (high; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and the lysate was

centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, after which the

supernatant was collected. The protein concentration was quantified

using a BCA protein assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), and proteins (20 µg) were separated by

SDS-PAGE on 10% gels. The proteins were then transferred to PVDF

membranes, which were incubated with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at

37°C. Subsequently, primary antibodies against β-actin (1:1,000;

cat. no. 4970; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), NLRP3 (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab263899; Abcam), interleukin (IL)-1β (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab315084; Abcam), IL-18 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab223293; Abcam), matrix

metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 (1:500; cat. no. 70R-50066; AmyJet

Scientific, Inc.), MMP-13 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab219620; Abcam),

caspase-1 (1:1,000; cat. nos. ab286125 for rat or ab138483 for

mouse; Abcam), PYD and CARD domain containing (ASC; 1:1,000; cat.

no. ab307560; Abcam) and gasdermin D (GSDMD; 1:1,000; cat. no.

ab219800; Abcam) were incubated with the PVDF membranes overnight

at 4°C. The membranes were then incubated with an HRP-labeled goat

anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (1:3,000; cat. no. A0208

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1 h.

After washing the membranes three times with TBS-Tween (0.1%), the

protein bands were detected using an ECL western blotting substrate

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The

intensities of the protein bands were analyzed using ImageJ 1.8.0

software (National Institutes of Health), and the relative protein

expression levels were calculated using β-actin as a reference.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage

rate assay

Rat primary chondrocytes (1×106

cells/well in a 6-well plate) were divided into control,

low-concentration (25 nM) TBTC, medium-concentration (50 nM) TBTC

and high-concentration (100 nM) TBTC groups and were treated at

37°C for 24 h. Cytotoxicity was evaluated by determining the LDH

leakage rate in cell supernatants using a cytotoxicity LDH assay

kit (MedChemExpress) according to the manufacturer's

instructions.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Rat primary chondrocytes (1×106

cells/well in a 6-well plate) were divided into control,

low-concentration (25 nM) TBTC, medium-concentration (50 nM) TBTC

and high-concentration (100 nM) TBTC groups and were treated at

37°C for 24 h. The chondrocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at room

temperature for 20 min and then blocked with 5% donkey serum at

room temperature for 2 h (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, the cells were incubated with a primary

antibody against NLRP3 (1:50; cat. no. ab263899; Abcam) or GSDMD

(1:50; cat. no. ab219800; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. After being

washed three times with PBS, the slides were incubated with Alexa

Fluor 350-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:200; cat. no.

A0408; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room temperature for

1 h, followed by incubation with antifade mounting medium

containing DAPI (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Images were

observed under a fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×20;

Olympus Corporation).

Cell cycle assay

Rat primary chondrocytes (1×106

cells/well in a 6-well plate) were divided into control,

low-concentration (25 nM) TBTC, medium-concentration (50 nM) TBTC

and high-concentration (100 nM) TBTC groups and were treated at

37°C for 24 h. The cell cycle assay was performed using the DNA

Content Quantitation Assay (Cell Cycle) (cat. no. CA1510; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Briefly, cells were

collected and fixed with 70% precooled ethanol (500 µl) at 4°C

overnight. The cells were then centrifuged at 800 × g at 4°C for 15

min, 100 µl RNase A solution was added to the cell precipitate and

the resuspended cells were incubated in a water bath at 37°C for 30

min. Subsequently, 400 µl PI staining solution was added to the

cell suspension, which was incubated at 4°C for 30 min in the dark.

Finally, the cells were analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II flow

cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data analysis was performed using

FlowJo 10 software (FlowJo, LLC).

EdU staining

Rat primary chondrocytes (1×106

cells/well in a 6-well plate) were divided into control,

low-concentration (25 nM) TBTC, medium-concentration (50 nM) TBTC

and high-concentration (100 nM) TBTC groups and were treated at

37°C for 24 h. EdU staining was performed using an EdU cell

proliferation assay kit (Shanghai Recordbio Biological Technology).

Rat primary chondrocytes (1×106 cells/well in a 6-well

plate) were incubated with 50 µM EdU (20 µl total volume) for 2 h

at 37°C. After three washes with PBS, the cells were incubated with

4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and then with

0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the

samples were blocked with antifade mounting medium containing DAPI

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and were observed under a

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). Cell proliferation

rate was calculated as follows: Cell proliferation rate

(%)=EdU-positive cells/DAPI-positive cells ×100.

Animal grouping and an OA mouse

model

The present study used rat primary chondrocytes

in vitro and a mouse model in vivo. The present study

aimed to verify that TBTC damaged articular chondrocytes in

different species and, compared with rat models, mouse models are

easier to generate and are less costly. C57BL/6J male mice [n=20;

Shulaibao (Wuhan) Biotechnology Co., Ltd.] were acclimated for 1

week at 22–24°C and 45% humidity. All mice were given free access

to food and water under a 12-h light/dark cycle. All mice were

randomly divided into the following four groups: Control, OA, TBTC

and TBTC + OA groups (n=5 mice/group). The mouse OA model was

induced by injection of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA; cat. no.

I2512; MilliporeSigma) as previously described (16). Specifically, MIA was dissolved in a

0.9% NaCl solution to a final concentration of 60 mg/ml, and 50 µl

MIA solution was injected into the right knee joint cavity of the

mice in the OA groups. The control mice were injected with 50 µl

0.9% NaCl solution. After 2 weeks of modeling, the OA model mice

were further divided into two groups: In the TBTC group, the mice

were injected with 50 µl 0.9% NaCl solution and were also

administered TBTC daily at a dose of 10 µg/kg for 2 weeks, and in

the other groups, the mice were administered an equal volume of

saline for a total of 2 weeks. All of the mice were euthanized at

the termination of the experiment, ensuring minimal suffering. No

mice died naturally during the study. All mice were monitored twice

daily for signs of discomfort, illness or distress by trained

personnel. To minimize suffering and distress, isoflurane was

utilized at an induction concentration of 5% and a maintenance

concentration of 2% prior to cervical dislocation. Humane endpoints

were established based on the guidelines from the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Yangzhou University, and included

>20% weight loss or gain, inability to eat or drink, persistent

lack of mobility, signs of severe and chronic pain, and any

conditions notably interfering with daily activities. When the mice

were fully unresponsive to nociceptive stimuli indicating that they

were fully anesthetized, cervical dislocation was used for

euthanasia. Death was verified by the absence of respiration,

heartbeat and reflexes. The knee joint tissues were subsequently

collected.

Safranin O-Fast Green staining

Cartilage sections (1.0×1.0×0.5 cm) were cut from

the mouse subchondral bone and fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 3 days at 4°C.

Subsequently, the sections were decalcified in a 30% formic acid

solution for 14 days at room temperature, dehydrated in an

increasing ethanol gradient, embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-µm

sections. The sections were stained using the modified Safranin-O

and Fast Green stain kit (for bone) (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Finally, the sections were blocked with neutral gum (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Normal cartilage was

red in color, and the background was green, and staining was

observed under a light microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining

Cartilage samples were cut into 5-µm sections as

aforementioned and were incubated using a H&E stain kit

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the sections were

incubated with hematoxylin at room temperature for 10 min, rinsed

in tap water, and then stained with eosin at room temperature for

30 sec. After rinsing in tap water, and following dehydration,

clearing and sealing, the sections were observed under a light

microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Toluidine blue staining

Cartilage samples were cut into 5-µm sections as

aforementioned and were deparaffinized and stained with a 1%

toluidine blue O solution (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20 min at 55°C, according to the

manufacturer's instructions. After being rinsed with distilled

water, the sections were dehydrated with 95% ethanol, cleared with

xylene and blocked with resin. Subsequently, the tissues were

observed under a light microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Rat primary chondrocytes (1×106

cells/well in a 6-well plate) were divided into control,

low-concentration (25 nM) TBTC, medium-concentration (50 nM) TBTC

and high-concentration (100 nM) TBTC groups and were treated at

37°C for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted from chondrocytes using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and was reverse transcribed into cDNA using

PrimeScript™ RT master mix (cat. no. RR036A; Takara Bio,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed

on an ABI StepOnePlus real-time fluorescence qPCR instrument

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using the SYBR® Select

master mix (Beijing Think-Far Technology Co., Ltd.). The

thermocycling conditions were as follows: Denaturation at 95°C for

30 sec, followed by 35 cycles of annealing at 60°C for 1 min and

extension at 95°C for 5 sec. The sequences of the primers used were

as follows: NLRP3, forward 5′-ATAGCGTCATACGGGGGAAG-3′, reverse

5′-CACCCACGGGCAAGATGAAA-3′; GAPDH, forward

5′-TGAGGAGTCCCCATCCCAAC-3′ and reverse

5′-ATGGTATTCGAGAGAAGGGAGG-3′. Relative gene expression was

calculated using the 2−∆∆Cq method (17) with GAPDH as an internal

control.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection

The siRNA targeting NLRP3 (sense

5′-AAUUUAAAUACAUUUCACCCA-3′; antisense 5′-TGGGTGAAATGTATTTAAATT-3′)

and the negative control (NC) siRNA (sense

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUUU-3′; antisense 5′-AAACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA-3′)

were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. Briefly, primary

rat chondrocytes (1×106 cells/well in a 6-well plate)

were transfected with si-NLRP3 or NC at a final concentration of 20

nM using Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 24 h, according to the manufacturer's

instructions before TBTC treatment. Subsequently, the cells were

collected immediately for subsequent experiments.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 18.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc.) was used

for data analysis and all experiments were repeated at least three

times. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Differences among more than two groups were examined by one-way

ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

TBTC inhibits rat chondrocyte

proliferation

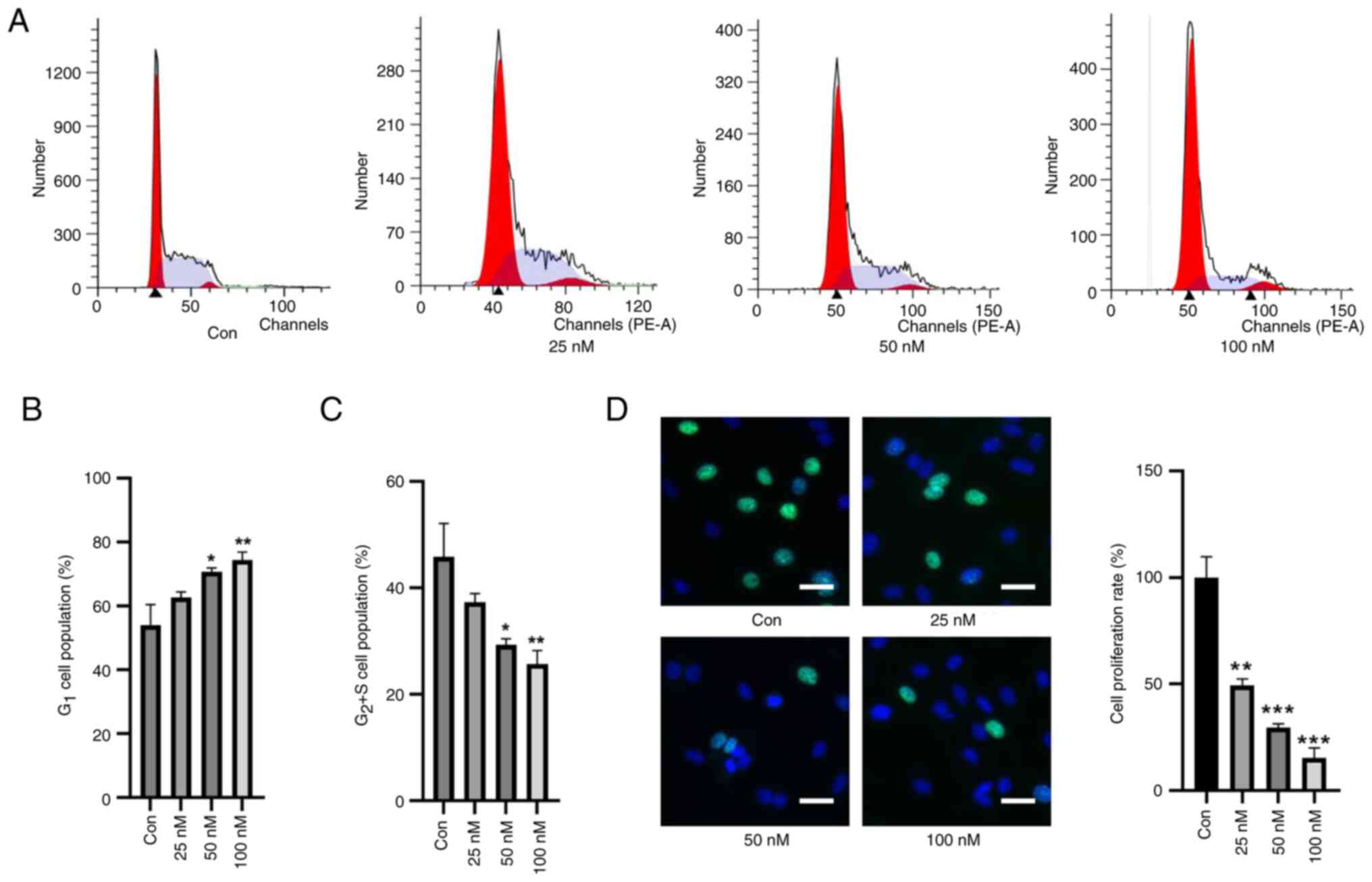

First, the effects of TBTC on the cell cycle of rat

chondrocytes were explored. Compared with in the control group,

TBTC increased the number of cells in G1 phase in a

concentration-dependent manner and decreased the number of cells in

the G2 and S phases (Fig.

1A-C). EdU staining also showed that the proliferation of rat

chondrocytes was significantly inhibited in response to an

increasing concentration of TBTC (Fig.

1D). These results preliminarily suggested that TBTC was

detrimental to the proliferation of rat chondrocytes.

TBTC induces rat chondrocyte

injury

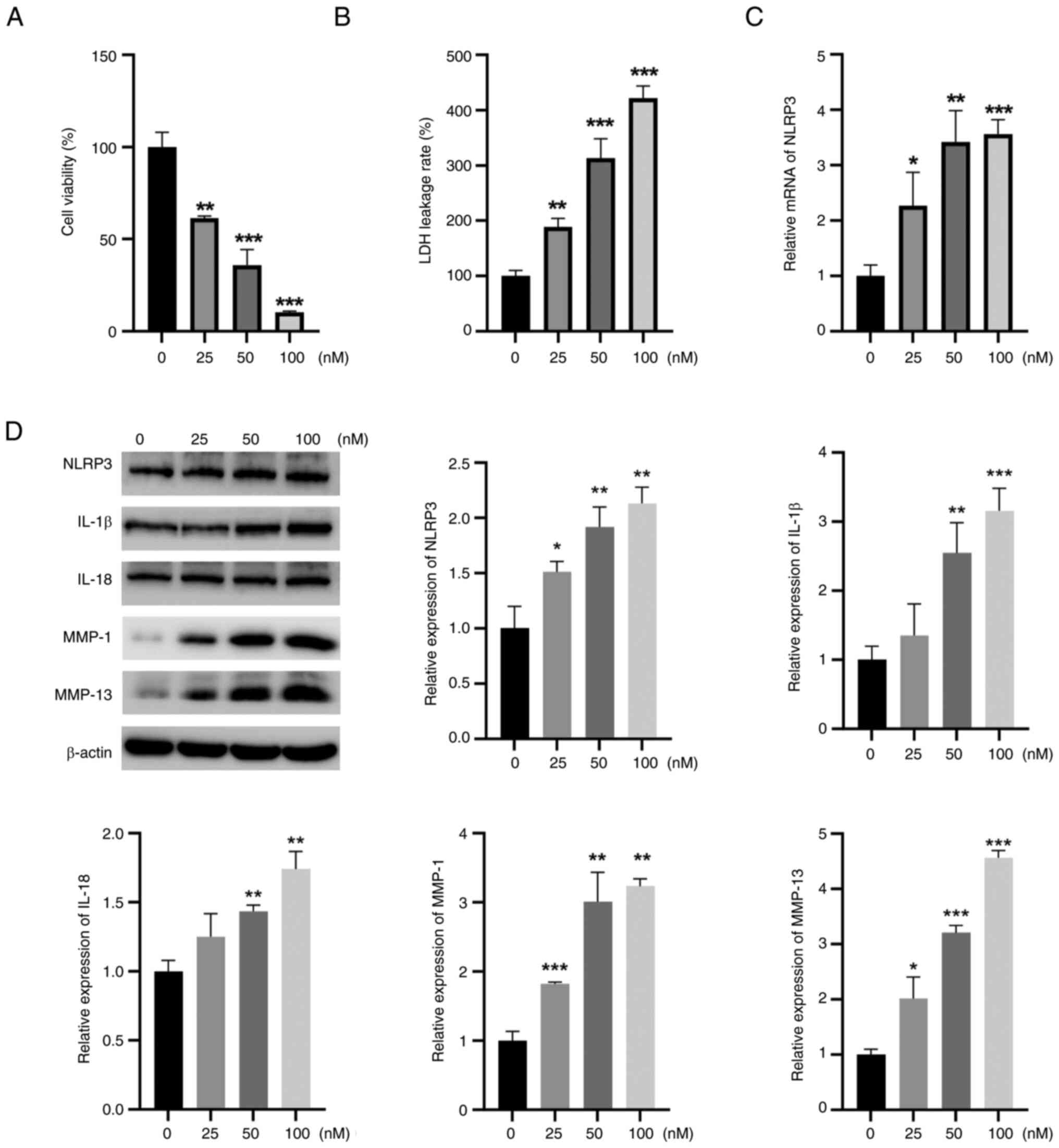

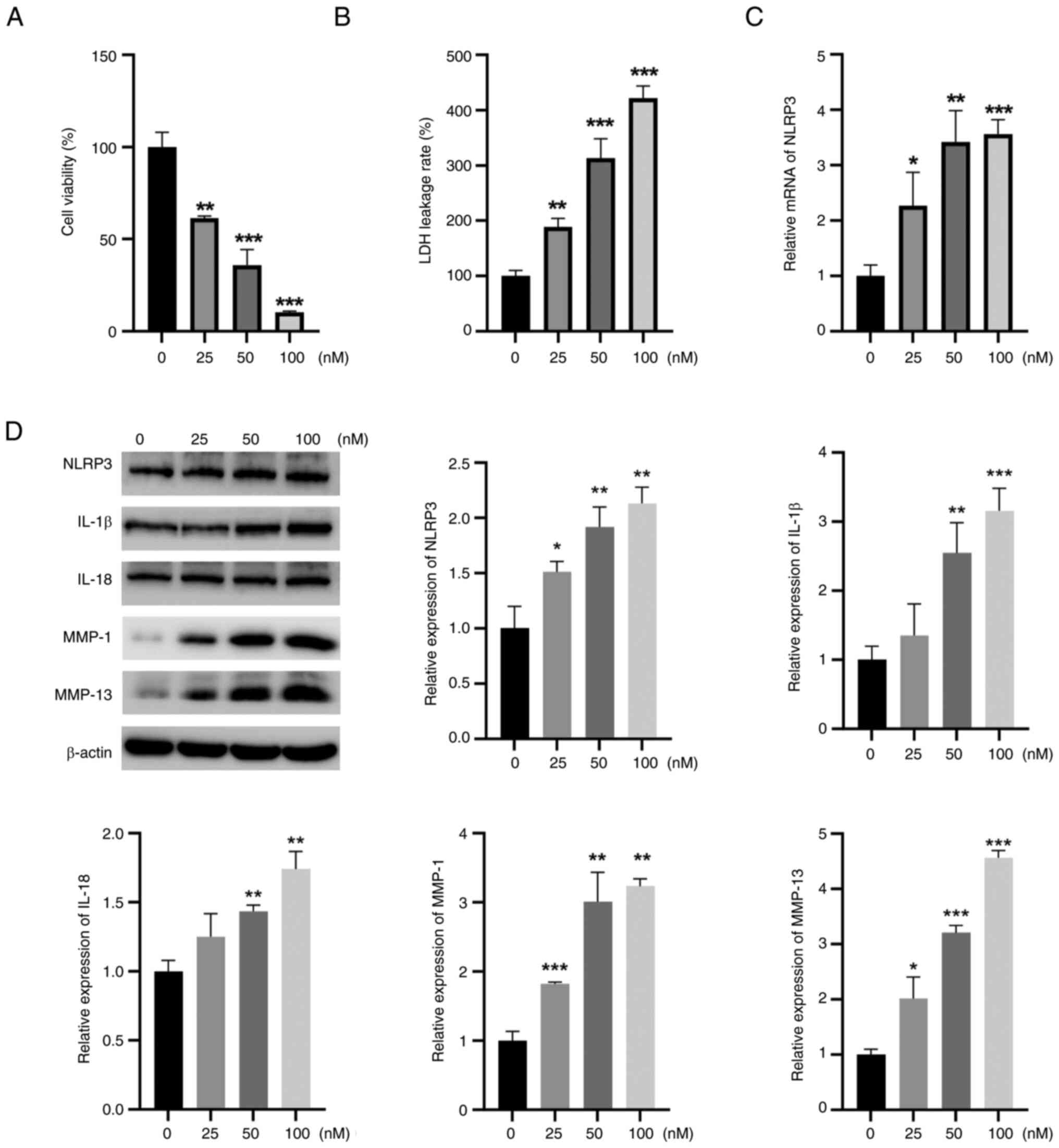

The CCK-8 assay results showed that TBTC reduced rat

chondrocyte viability in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). LDH leakage is the main

indicator of pyroptosis, and LDH leakage was significantly greater

in the TBTC groups than that in the control group (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the mRNA expression

levels of NLRP3 in rat chondrocytes in the TBTC group were

significantly greater than those in the control group (Fig. 2C). After incubation with TBTC, the

protein expression levels of NRLP3, IL-1β, IL-18, MMP-1 and MMP-13

in rat chondrocytes were significantly greater than those in the

control group (Fig. 2D). These

results suggested that TBTC serves a critical role in the

destruction of chondrocytes by activating the NLRP3

inflammasome.

| Figure 2.TBTC induces chondrocyte damage in

rats. (A) Cell Counting Kit-8 results showed that TBTC reduced rat

chondrocyte viability in a concentration-dependent manner. (B) TBTC

significantly increased LDH leakage from rat chondrocytes. (C)

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR results revealed that TBTC

elevated NLRP3 mRNA expression levels. (D) Western blot analysis

results revealed that TBTC upregulated the protein expression

levels of NLRP3, IL-1β, IL-18, MMP-1 and MMP-13 in rat

chondrocytes. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. Con. Con,

control; IL, interleukin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MMP, matrix

metalloproteinase; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3;

TBTC, tributyltin chloride. |

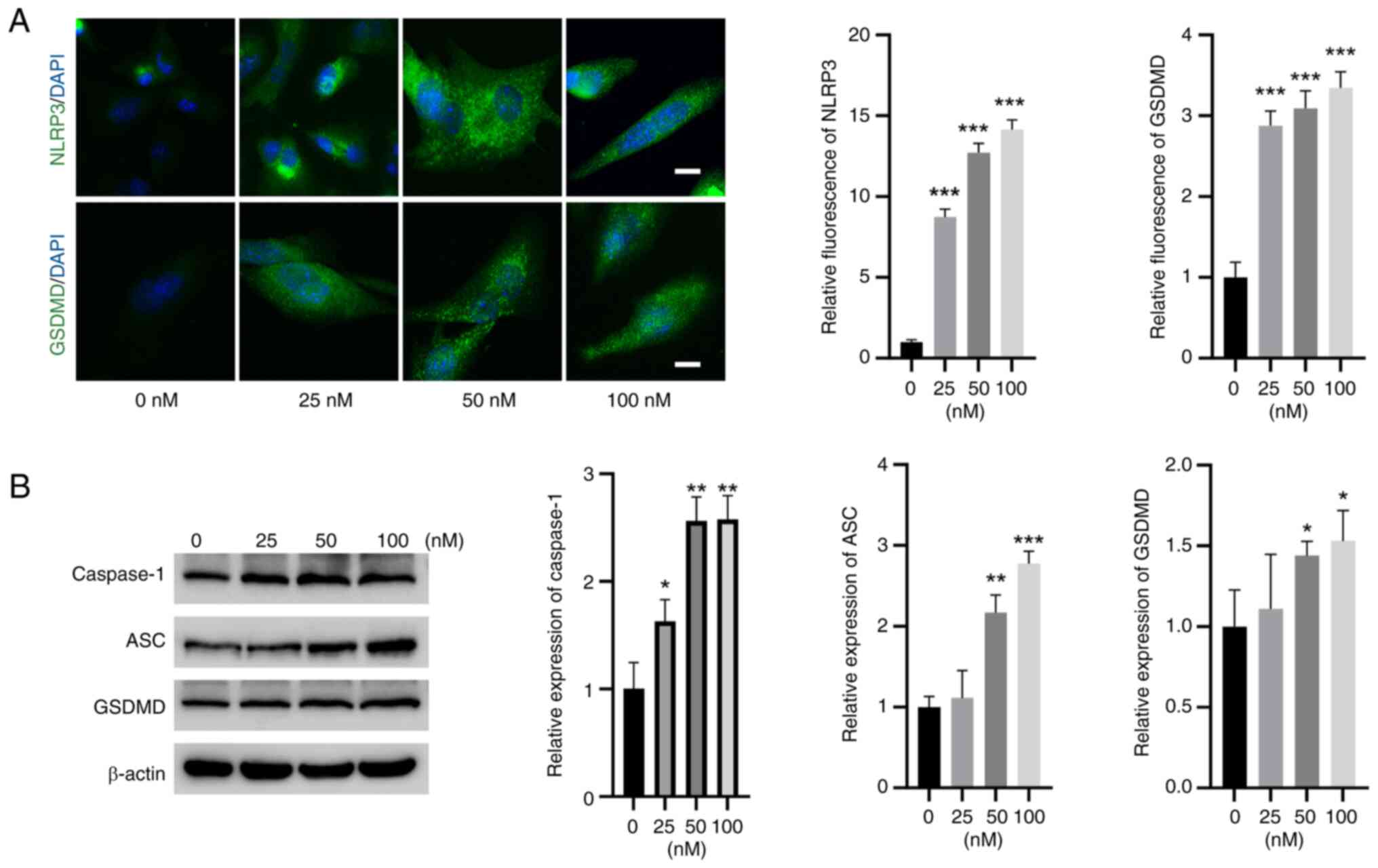

TBTC activates NLRP3 and caspase-1

signaling in rat chondrocytes

IF experiments revealed that the expression of NLRP3

and GSDMD was significantly greater in rat chondrocytes in the TBTC

groups than that in the control group (Fig. 3A). Moreover, western blot analysis

revealed that the expression levels of caspase-1, ASC and GSDMD

were significantly elevated in the TBTC groups compared with those

in the control group (Fig. 3B),

indicating the induction of pyroptosis by TBTC in rat

chondrocytes.

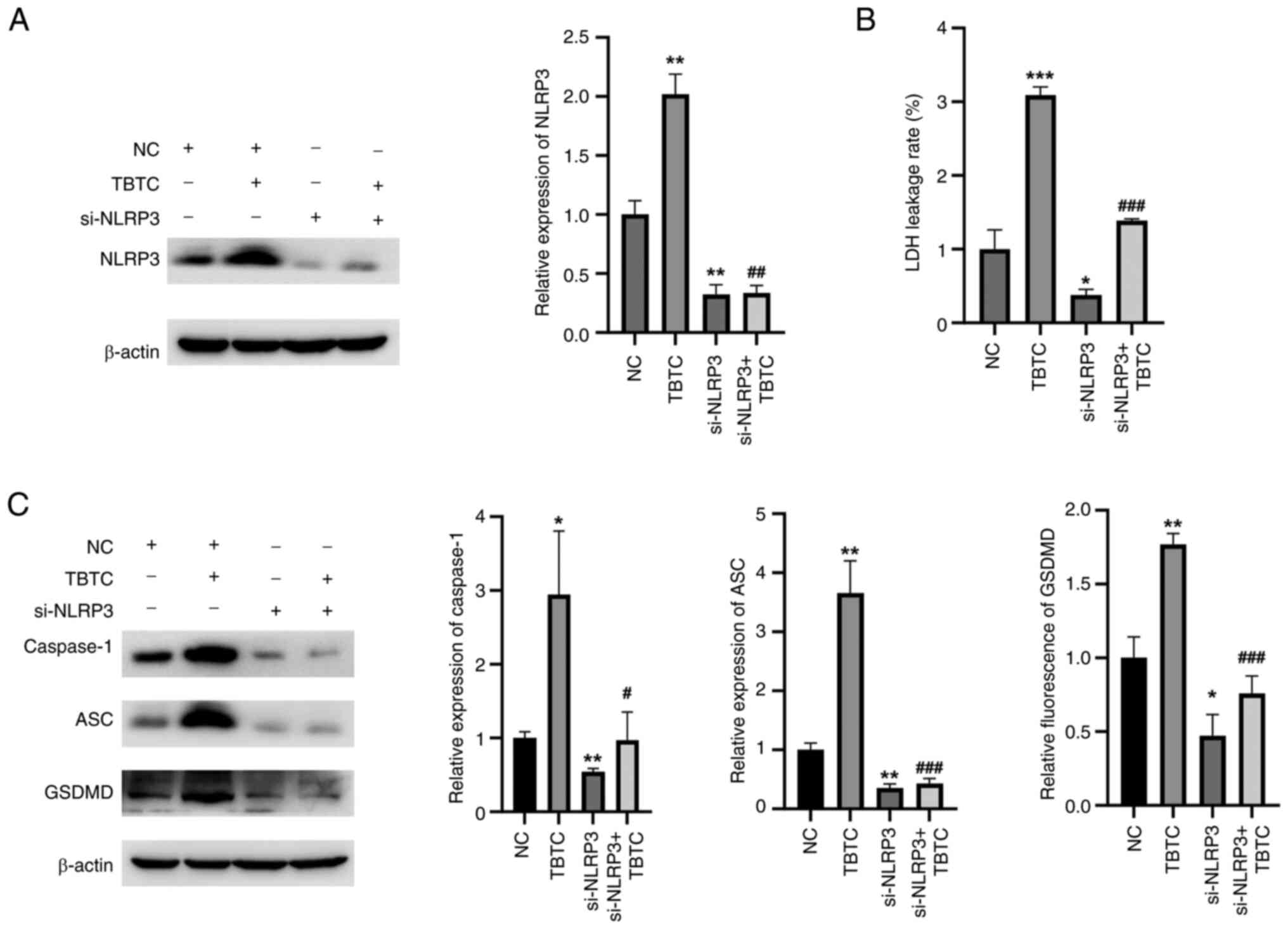

TBTC induces rat chondrocyte

pyroptosis through the activation of NLRP3 signaling

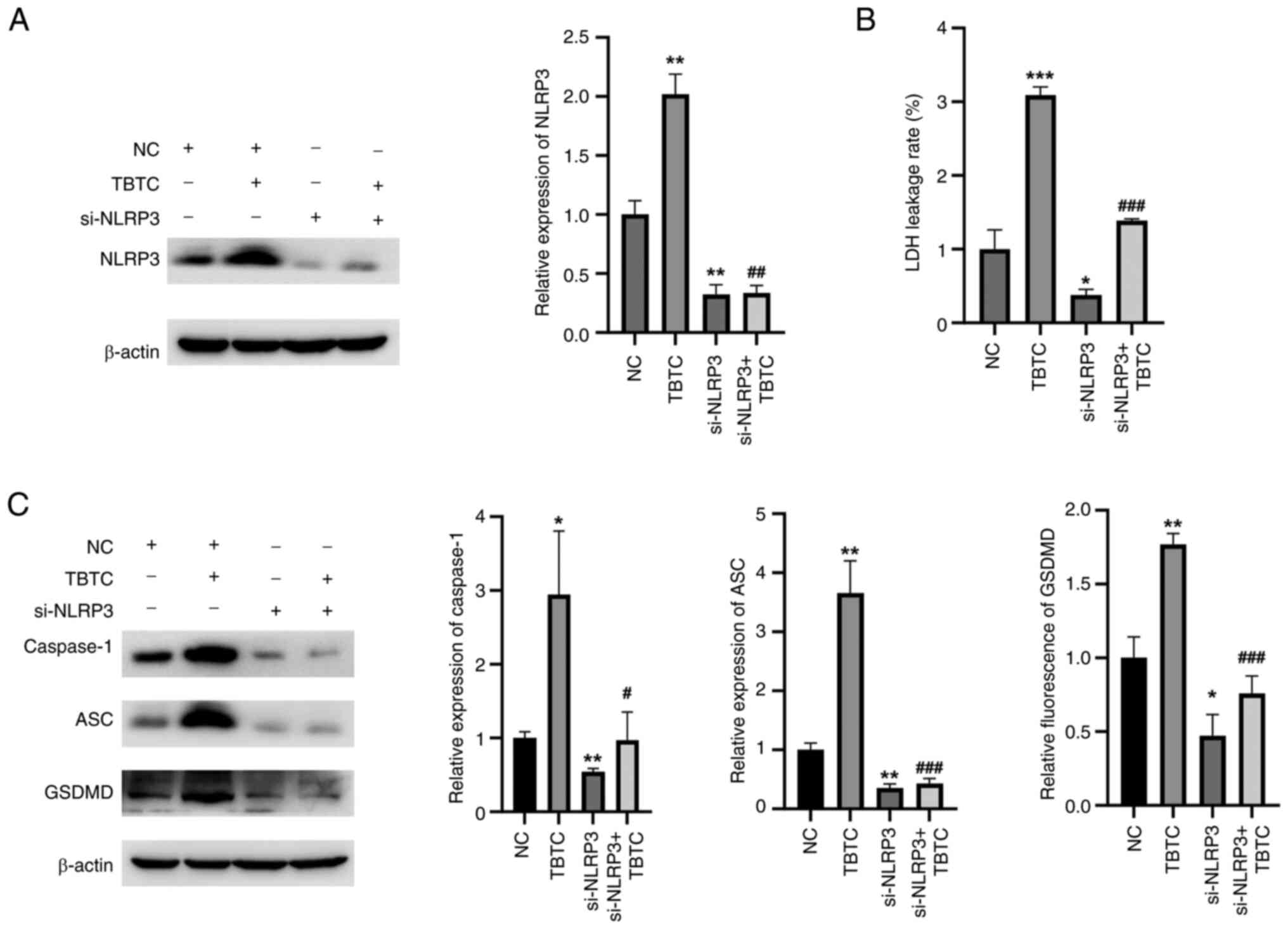

To further verify whether TBTC induces rat

chondrocyte pyroptosis via NLRP3, cells were transfected with a

siRNA specifically targeting NLRP3. The siRNA targeting NLRP3

effectively inhibited NLRP3 expression compared with NC group

(Fig. 4A). Compared with that in

the TBTC group, the LDH leakage rate was significantly decreased in

the si-NLRP3 + TBTC group (Fig.

4B). Moreover, the expression levels of pyroptosis-related

proteins, including caspase-1, ASC and GSDMD, were significantly

reduced in the si-NLRP3 + TBTC group than those in the TBTC group

(Fig. 4C). These results suggested

that TBTC induced rat chondrocyte pyroptosis by activating NLRP3

signaling.

| Figure 4.TBTC induces rat chondrocyte

pyroptosis by activating NLRP3 signaling. (A) Western blot analysis

revealed that si-NLRP3 could effectively inhibit the protein

expression levels of NLRP3 in rat chondrocytes compared with that

of the negative control. (B) Knockdown of NLRP3 inhibited the

TBTC-induced increase in LDH leakage. (C) Compared with TBTC

treatment, silencing NLRP3 reduced the expression levels of

pyroptosis-related proteins. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

vs. NC; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 vs. TBTC. ASC, PYD and CARD domain

containing; Con. Con, control; GSDMD, gasdermin D; LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase; NC, negative control; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3; si, small interfering; TBTC, tributyltin

chloride. |

TBTC enhances cartilage damage in the

joints of mice from the OA group

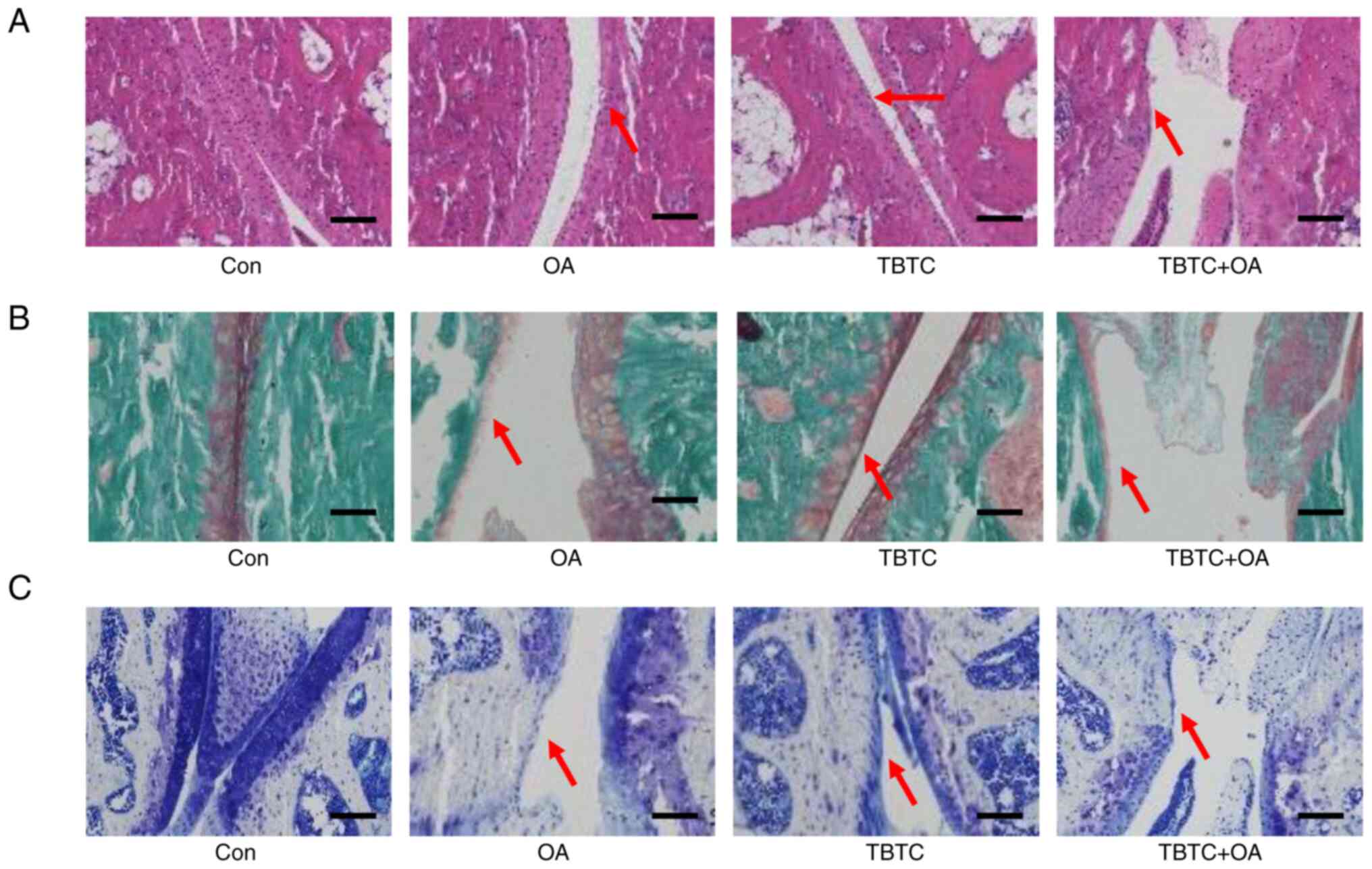

H&E staining showed that in the cartilage of the

control group, the cell nuclei were dark blue, the cytoplasm and

cartilage matrix were pink, and the coloring was homogeneous; the

surface of the cartilage was smooth and flat, and was arranged

parallel to the surface of the joint (Fig. 5A). In the OA group, the surface of

the cartilage was rough, the integrity of the cartilage was

disrupted, and the surface cartilage exhibited fibrotic

degeneration and defects. In the TBTC-treated group, the cartilage

surface also showed some defects. Moreover, the integrity of the

cartilage was markedly disrupted, and the cartilage defects were

more pronounced in the TBTC + OA group (Fig. 5A). The results of Safranin O-Fast

Green staining showed that the cartilage matrix was intact in the

control group, as evidenced by proteoglycans stained in red, and by

fibers, the subchondral bone cortex and trabeculae stained in green

(Fig. 5B). In the OA and TBTC

groups, the cartilage matrix exhibited some degree of disruption,

as evidenced by reduced proteoglycan coloration. In the TBTC + OA

group, the reduction in proteoglycan coloring was further

exacerbated (Fig. 5B). Toluidine

blue staining also revealed greater articular cartilage

degeneration in the mice from the OA and TBTC groups than in those

from the control group (Fig. 5C).

This cartilage degeneration was more pronounced in the mice from

the TBTC + OA group (Fig. 5C).

These results suggested that TBTC enhanced articular cartilage

degeneration in a mouse model of OA.

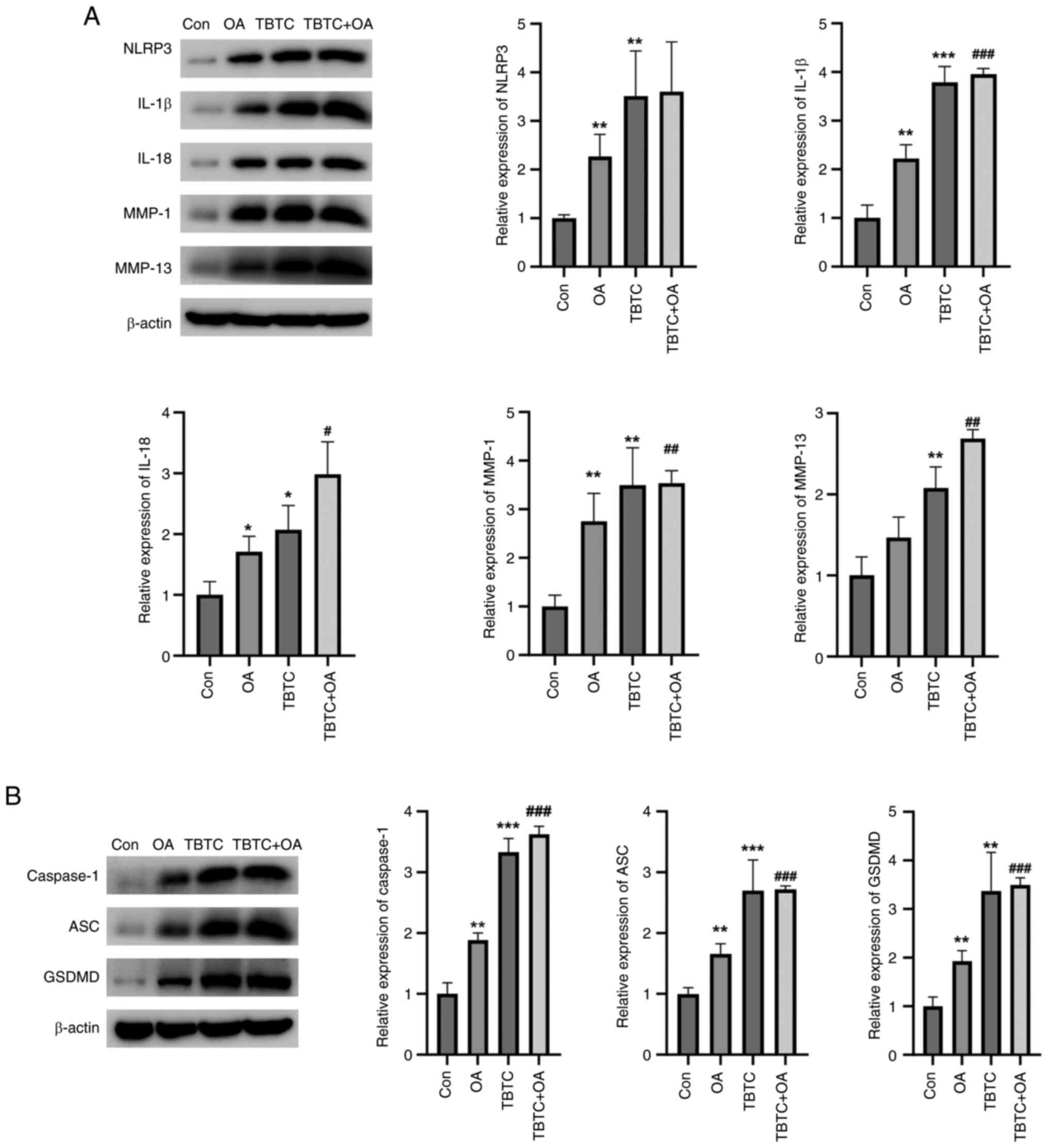

TBTC enhances the NLRP3-mediated

inflammatory response and pyroptosis in OA mouse bone joints

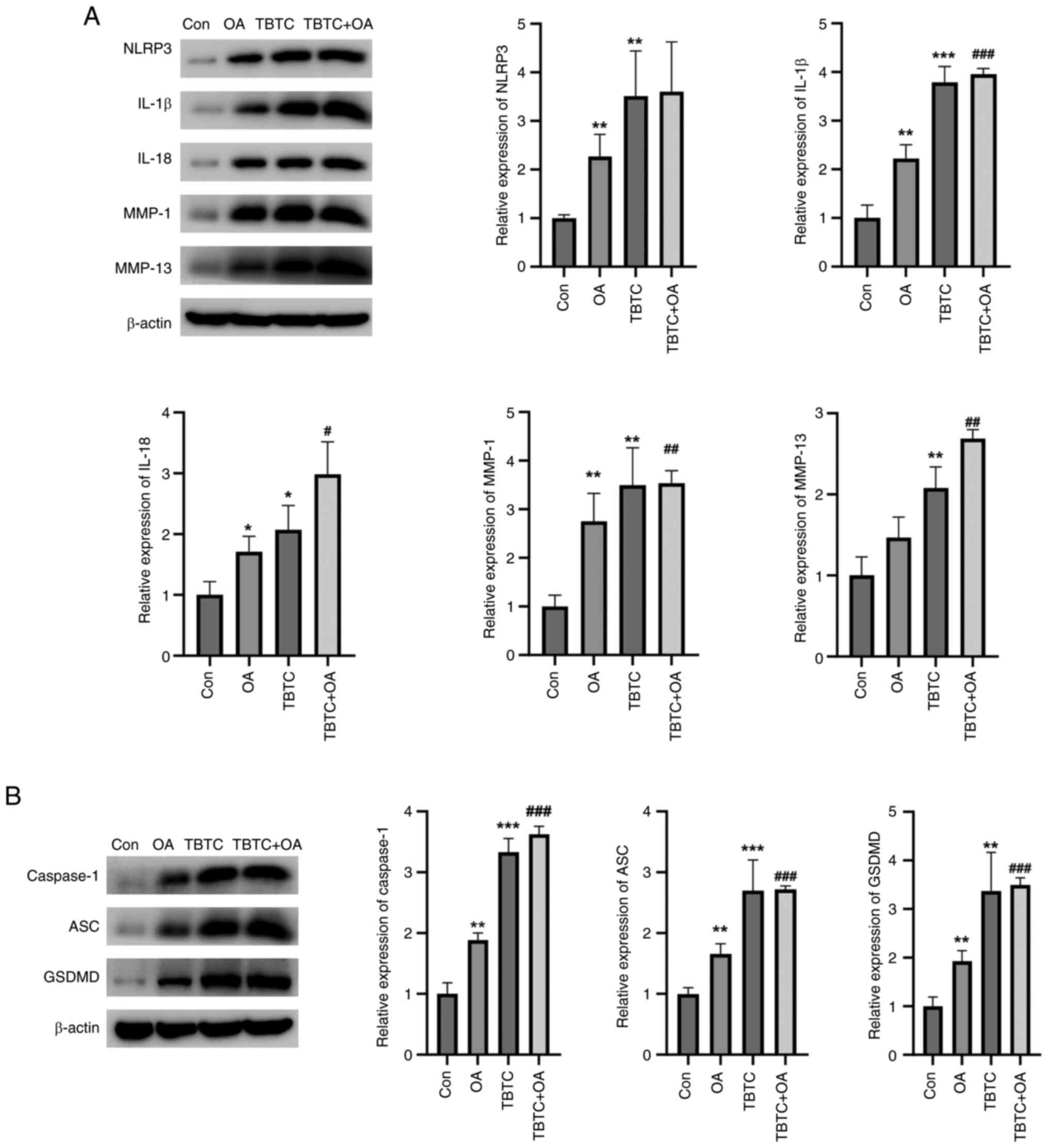

The present study then examined the effects of TBTC

on cartilage tissue damage in mice. The results revealed that the

protein expression levels of NLRP3, IL-1β, IL-18, MMP-1 and MMP-13

were significantly greater in the OA and TBTC groups than those in

the control group (Fig. 6A).

Similarly, the proteins were also upregulated in the TBTC + OA

group (Fig. 6A). The expression

levels of pyroptosis-related proteins were also detected. Notably,

the expression levels of the pyroptosis-related proteins caspase-1,

ASC and GSDMD were significantly greater in the OA and TBTC groups

than those in the control group (Fig.

6B). These proteins were also increased in the TBTC + OA group

(Fig. 6B). These results confirmed

that TBTC could increase the NLRP3-mediated inflammatory response

and pyroptosis, thereby promoting osteoarticular injury in

mice.

| Figure 6.TBTC enhances the NLRP3-mediated

inflammatory response and cellular pyroptosis in mouse OA. (A) TBTC

increased the protein expression levels of NLRP3, IL-1β, IL-18,

MMP-1 and MMP-13. (B) TBTC increased the expression levels of the

pyroptosis-related proteins caspase-1, ASC and GSDMD in mouse

osteoarticular tissues. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs.

Con; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 vs. OA. Con. ASC, PYD and CARD domain

containing; Con, control; GSDMD, gasdermin D; IL, interleukin; MMP,

matrix metalloproteinase; OA, osteoarthritis; TBTC, tributyltin

chloride. |

Discussion

TBT is a synthetic metal compound and an important

industrial raw material that is widely used as a stabilizer for

plastic products, a pesticide, a fungicide, and an anticorrosive

and antifouling coating for ships and boats (18). In the past 20 years, TBT has

entered the environment, particularly the marine environment, in

large quantities, resulting in widespread pollution of the oceans

(18). TBT pollution has attracted

the attention of a number of countries worldwide, and some

countries have begun to take measures to limit the use of TBT.

Studies have shown that TBT not only has endocrine-disrupting

effects on organisms and causes reproductive toxicity, but also

affects the nervous and immune systems (15,19,20).

A previous study revealed that TBTC reduces the bone mineral

density in the rat femoral epiphysis by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin

signaling, which in turn disrupts the homeostasis between

osteogenesis and adipogenesis (21). However, the effects of TBTC on

chondrocytes are still poorly understood.

To the best of our knowledge, for the first time,

the present study revealed that TBTC decreased the survival of rat

chondrocytes in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, TBTC

increased the leakage rate of LDH, an important indicator of

pyroptosis. Cellular pyroptosis is a type of lytic and

inflammatory-dependent programmed cell death that leads to the

cytolysis and release of inflammatory mediators (IL-1β and IL-18),

which then cause tissue damage (4,6,22).

Chung et al (23) reported

that 0.01–0.5 µM TBT induced senescence of human articular

chondrocytes in vitro. Their results showed that 10 nM TBT

reduced human chondrocyte viability and promoted elevated

expression of inflammatory factors, but with no statistically

significant difference. By contrast, 100 nM TBT significantly

induced human chondrocyte senescence and inflammatory responses.

Notably, pyroptosis is very similar to apoptosis, but some aspects

are markedly different from apoptosis because this death phenomenon

is dependent on pro-inflammatory caspase-1. Based on the

relationship between pyroptosis and inflammation, a low

concentration (25 nM) of TBTC was selected to ensure that it

induced an inflammatory response, as well as a high concentration

(100 nM) of TBTC, and an intermediate concentration (50 nM) of

TBTC. The results revealed that the protein expression levels of

IL-1β, IL-18, MMP-1 and MMP-13 were significantly increased in rat

chondrocytes after TBTC treatment, indicating that TBTC may induce

the release of inflammatory mediators in rat chondrocytes by

activating the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Inflammation caused by activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome is the basis of numerous diseases, such as breast

cancer and acute liver injury (6,24,25).

Once activated, NLRP3 interacts with the adaptor ASC, which

subsequently causes the activation of caspase-1 (6). GSDMD, a member of the GSDM family, is

cleaved by caspase-1 and releases the N-terminal structural domain,

which oligomerizes at the plasma membrane and forms a pore for the

release of substrates, such as IL-1β and IL-18 (22,26).

Caspase-1-mediated cellular death serves a role in the regulation

of various diseases, such as cancer, cardiac hypertrophy and

neurological disorders (27–29).

In addition, caspase-1 deficiency reduces arthropathic changes in

chronic arthritis (30). In the

present study, in rat chondrocytes, TBTC was able to increase the

expression levels of caspase-1, GSDMD and ASC. To further validate

that TBTC activates the upregulation of inflammatory factors in

chondrocytes and triggers pyroptosis through activation of the

NLRP3 inflammasome, chondrocytes were transfected with a siRNA

specifically targeting NLRP3. The results showed that silencing

NLRP3 effectively reversed TBTC-mediated increases in the

expression of caspase-1, GSDMD and ASC. Therefore, it was

hypothesized that TBTC enhanced the expression of the inflammatory

factors IL-1β and IL-18 through upregulation of the NLRP3/caspase-1

pyroptosis pathway, causing further expansion of the inflammatory

response.

OA is a progressive joint disease, and drugs

currently used in the clinic, such as acetaminophen and

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can alleviate pain but cannot

cure the disease (9). The NLRP3

inflammasome has been shown to be associated with the pathogenesis

of various arthritic diseases by stimulating inflammatory mediators

and degradative enzymes (9,31).

It has previously been reported that the NLRP3 inflammasome serves

an important role in inflammation and apoptosis of fibroblast-like

synoviocytes, suggesting that the NLRP3 inflammasome is involved in

the progression of OA (32,33).

Since TBTC can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated

inflammatory response and cellular pyroptosis in chondrocytes, the

present study aimed to assess whether TBTC can aggravate the

progression of OA. To evaluate this, a mouse model of OA was

constructed and the mice were treated with TBTC. Chung et al

(23) reported that 5 and 25

µg/kg/day TBTC induced mouse articular cartilage aging in

vivo. This previous study revealed that 25 µg/kg/day TBTC

significantly induced aging of joints in mice; however, at 5

µg/kg/day, there was no significant senescence of articular

cartilage in mice, but the inflammatory response showed an

increased trend. The reason why a high dose of TBTC was not used in

the present study is that 25 µg/kg/day TBT induced chondrocyte

senescence, which itself causes senescence-associated secretory

phenotype. Unlike the aforementioned study, the present study did

not consider whether TBTC induced chondrocyte senescence, but

instead the present study explored the effects of TBTC on mouse OA.

Therefore a dose slightly higher than 5 µg/kg/day was used to

ensure that it enhanced the inflammatory response without inducing

senescence, thus providing insight into whether TBTC worsened OA.

H&E staining revealed more severe cartilage destruction in the

OA + TBTC group than in the OA group, which was accompanied by

subchondral bone sclerosis, suggesting that TBTC aggravated

cartilage degeneration in the osteoarthritic joints in the OA

group. The results of Safranin O-Fast Green and toluidine blue

staining showed that the loss of proteoglycan staining was more

obvious in the OA + TBTC group than in the control group. These

results suggested that TBTC may reduce the amounts of collagen and

proteoglycans in articular cartilage tissue, which leads to

cartilage destruction and aggravates the progression of OA.

Consistent with the results of the in vitro study, TBTC

treatment further exacerbated the expression levels of

NLRP3-mediated inflammatory factors, as well as cellular

pyroptosis-related proteins in the joint tissues of mice from the

OA group, further confirming that the activation of NLRP3 by TBTC

exacerbated the inflammatory response and cartilage tissue damage

in the mice from the OA group.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, the

present study revealed, for the first time, that TBTC exacerbated

the progression of OA in vivo by activating the NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated inflammatory response and cellular pyroptosis

in chondrocytes. Therefore, TBTC may cause damage to the articular

cartilage, and it is thus necessary to strictly control the use of

TBT.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Science

Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. JZ-2021-087).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SX and RM designed the study, performed the

experiments, analyzed the data and provided final approval of the

version to be published. SX and RM confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. Both authors read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Animal Ethics

Committee at Yangzhou University (approval no. YZ-ja986B; Yancheng,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Abramoff B and Caldera FE: Osteoarthritis:

Pathology, diagnosis, and treatment options. Med Clin North Am.

104:293–311. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Colletti A and Cicero AFG: Nutraceutical

approach to chronic osteoarthritis: From molecular research to

clinical evidence. Int J Mol Sci. 22:129202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hawker GA and King LK: The burden of

osteoarthritis in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 38:181–192. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang J, Hu S, Bian Y, Yao J, Wang D, Liu

X, Guo Z, Zhang S and Peng L: Targeting cell death: Pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis in osteoarthritis. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 9:7899482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sharma BR and Kanneganti TD: NLRP3

inflammasome in cancer and metabolic diseases. Nat Immunol.

22:550–559. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Huang Y, Xu W and Zhou R: NLRP3

inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell Mol Immunol.

18:2114–2127. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Fu J and Wu H: Structural mechanisms of

NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation. Annu Rev Immunol.

41:301–316. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen Z, Zhong H, Wei J, Lin S, Zong Z,

Gong F, Huang X, Sun J, Li P, Lin H, et al: Inhibition of Nrf2/HO-1

signaling leads to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome

in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 21:3002019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Li X, Mei W, Huang Z, Zhang L, Zhang L, Xu

B, Shi X, Xiao Y, Ma Z, Liao T, et al: Casticin suppresses

monoiodoacetic acid-induced knee osteoarthritis through inhibiting

HIF-1α/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. Int Immunopharmacol.

86:1067452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zu Y, Mu Y, Li Q, Zhang ST and Yan HJ:

Icariin alleviates osteoarthritis by inhibiting NLRP3-mediated

pyroptosis. J Orthop Surg Res. 14:3072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jin X, Dong X, Sun Y, Liu Z, Liu L and Gu

H: Dietary fatty acid regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome via the

TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway affects chondrocyte pyroptosis. Oxid

Med Cell Longev. 2022:37113712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Daigneault BW and de Agostini Losano JD:

Tributyltin chloride exposure to post-ejaculatory sperm reduces

motility, mitochondrial function and subsequent embryo development.

Reprod Fertil Dev. 34:833–843. 2022. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen P, Song Y, Tang L, Zhong W, Zhang J,

Cao M, Chen J, Cheng G, Li H, Fan T, et al: Tributyltin chloride

(TBTCL) induces cell injury via dysregulation of endoplasmic

reticulum stress and autophagy in Leydig cells. J Hazard Mater.

448:1307852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhao C, Zhang Y, Suo A, Mu J and Ding D:

Toxicity of tributyltin chloride on haarder (Liza haematocheila)

after its acute exposure: Bioaccumulation, antioxidant defense,

histological, and transcriptional analyses. Fish Shellfish Immunol.

130:501–511. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Horie Y, Yamagishi T, Shintaku Y, Iguchi T

and Tatarazako N: Effects of tributyltin on early life-stage,

reproduction, and gonadal sex differentiation in Japanese medaka

(Oryzias latipes). Chemosphere. 203:418–425. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Pitcher T, Sousa-Valente J and Malcangio

M: The monoiodoacetate model of osteoarthritis pain in the mouse. J

Vis Exp. 537462016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Barbosa KL, Dettogni RS, da Costa CS,

Gastal EL, Raetzman LT, Flaws JA and Graceli JB: Tributyltin and

the female hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal disruption. Toxicol Sci.

186:179–189. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

de Araújo JFP, Podratz PL, Merlo E,

Sarmento IV, da Costa CS, Niño OMS, Faria RA, Freitas Lima LC and

Graceli JB: Organotin exposure and vertebrate reproduction: A

review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9:642018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ximenes CF, Rodrigues SML, Podratz PL,

Merlo E, de Araújo JFP, Rodrigues LCM, Coitinho JB, Vassallo DV,

Graceli JB and Stefanon I: Tributyltin chloride disrupts aortic

vascular reactivity and increases reactive oxygen species

production in female rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int.

24:24509–24520. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yao W, Wei X, Guo H, Cheng D, Li H, Sun L,

Wang S, Guo D, Yang Y and Si J: Tributyltin reduces bone mineral

density by reprograming bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in rat.

Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 73:1032712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

An S, Hu H, Li Y and Hu Y: Pyroptosis

plays a role in osteoarthritis. Aging Dis. 11:1146–1157. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chung YP, Weng TI, Chan DC, Yang RS and

Liu SH: Low-dose tributyltin triggers human chondrocyte senescence

and mouse articular cartilage aging. Arch Toxicol. 97:547–559.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Faria SS, Costantini S, de Lima VCC, de

Andrade VP, Rialland M, Cedric R, Budillon A and Magalhães KG:

NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated cytokine production and pyroptosis cell

death in breast cancer. J Biomed Sci. 28:262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yu C, Chen P, Miao L and Di G: The role of

the NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death in acute liver

injury. Int J Mol Sci. 24:30672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang L, Xing R, Huang Z, Zhang N, Zhang

L, Li X and Wang P: Inhibition of synovial macrophage pyroptosis

alleviates synovitis and fibrosis in knee osteoarthritis. Mediators

Inflamm. 2019:21659182019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li S, Sun Y, Song M, Song Y, Fang Y, Zhang

Q, Li X, Song N, Ding J, Lu M and Hu G:

NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis exerts a crucial role in

astrocyte pathological injury in mouse model of depression. JCI

Insight. 6:e1468522021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yan H, Luo B, Wu X, Guan F, Yu X, Zhao L,

Ke X, Wu J and Yuan J: Cisplatin induces pyroptosis via activation

of MEG3/NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway in triple-negative breast

cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 17:2606–2621. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang F, Liang Q, Ma Y, Sun M, Li T, Lin L,

Sun Z and Duan J: Silica nanoparticles induce pyroptosis and

cardiac hypertrophy via ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway. Free Radic

Biol Med. 182:171–181. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu J, Jia S, Yang Y, Piao L, Wang Z, Jin

Z and Bai L: Exercise induced meteorin-like protects chondrocytes

against inflammation and pyroptosis in osteoarthritis by inhibiting

PI3K/Akt/NF-κB and NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling. Biomed

Pharmacother. 158:1141182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang Y, Yan H, Jiang Y, Chen T, Ma Z, Li

F, Lin M, Xu Y, Zhang X, Zhang J and He H: Long non-coding RNA

IGF2-AS represses breast cancer tumorigenesis by epigenetically

regulating IGF2. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 246:371–379. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sakalyte R, Denkovskij J, Bernotiene E,

Stropuviene S, Mikulenaite SO, Kvederas G, Porvaneckas N, Tutkus V,

Venalis A and Butrimiene I: The expression of inflammasomes NLRP1

and NLRP3, toll-like receptors, and vitamin D receptor in synovial

fibroblasts from patients with different types of knee arthritis.

Front Immunol. 12:7675122022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhao LR, Xing RL, Wang PM, Zhang NS, Yin

SJ, Li XC and Zhang L: NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes mediate

LPS/ATP-induced pyroptosis in knee osteoarthritis. Mol Med Rep.

17:5463–5469. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|