Introduction

Maintaining of skeletal muscle functional

homeostasis is an important factor in the quality of life,

including posture, movement and breathing, in addition to

regulating glucose and protein metabolism and heat production

(1,2). In addition, skeletal muscle loss can

lead to adverse health outcomes including disability, weakness,

fatigue, insulin resistance and mortality (3–5).

Therefore, preventing muscle loss and strengthening the muscles

have important implications for athletes and individuals who want

to maintain a healthy body. Various factors, including acute or

chronic disease, biochemical changes due to aging, poor nutrition,

or lack of activity can lead to muscle loss, which is difficult to

control because it is multifactorial and genetically influenced

(3,6). However, decreased protein synthesis,

protein degradation, mitochondrial and satellite cell dysfunction,

and increased inflammation are associated with muscle loss

(7). Previously, research on the

development of various functional foods and medicines for the

strengthening muscle function and maintaining the balance between

protein synthesis and degradation in muscles is being actively

conducted. In addition, herbs and medicinal plants, whose various

beneficial functions have been proven in ethnopharmacological

studies, have been safely used for a long time. Therefore, they

have been the focus of development as natural medicines to prevent

and treat muscle loss (8–10).

Saururus chinensis (Lour.) Baill. (SC) is a

perennial herbaceous plant of the Saururaceae family, mainly

distributed in wet and humid regions of East Asia and rarely found

in lowland wetlands on Jeju Island, South Korea. In South Korea, SC

is an Endangered Species designated by the Korea Forest Service and

a Class 2 endangered wild animal or plant species by the Ministry

of Environment (11,12). It has been widely used as

traditional Chinese medicine for a wide range of disorders

including edema, pneumonia, hypertension, leprosy, jaundice,

gonorrhea, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory diseases (13–16).

SC contains essential oil such as quercetin, quercitrin,

isoquercitrin, rutin and tannin as main components, and contains

various lignans (17,18), which have several pharmacological

activities including anti-asthmatic (19), anti-oxidant (20), anti-inflammatory (21–23),

anti-atopic (24), anticancer

(25) and hepatoprotective

(26) properties. In addition,

according to a previous study, sauchinone isolated from the roots

of SC protects oxidative stress-induced C2C12 myoblast damage by

regulating heat shock protein-70 level (27). However, the effects of SC extract

(SCE) on muscle mass, function and metabolic mechanisms have not

yet been elucidated.

Therefore, to evaluate how SCE may be beneficial to

muscle function, the present study investigated the regulation of

muscle differentiation, mitochondrial biogenic factor, energy

metabolism and protein synthesis in C2C12 mouse skeletal muscle

cells via activation of the PGC-1α, AMP-activated protein kinase

(AMPK) and the AKT/mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway post-SCE

treatment.

Materials and methods

Chemical, reagents and antibodies

SCE (cat. no. KPM046-069) was purchased from the

Korea Plant Extract Bank of the Korea Research Institute of

Bioscience and Biotechnology (Cheongju, Korea). The maximum

concentration of DMSO in the cell culture medium was 0.1% (v/v).

TRIzol® reagent was purchased from Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal

bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin were obtained from

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Specific antibodies against

myosin heavy chain (MyHC; 1:500; cat. no. sc-376157), myogenic

differentiation 1 (MyoD; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-377460), myogenin and

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 α

(PGC-1α; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-518038) were obtained from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc. Antibodies against non-phospho (active)

β-catenin (1:1,000; cat. no. 8814), β-catenin (1:1,000; cat. no.

9582), phospho-AMPK (1:1,000; cat. no. 2535), AMPK (1:1,000; cat.

no. 2532), phospho-AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. 9271), AKT (1:1,000; cat.

no. 9272), phospho-mTOR (1:1,000; cat. no. 2971), mTOR (1:1,000;

cat. no. 2983), phospho-ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1(p70S6K1)

(1:1,000; cat. no. 9234), p70S6K1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 2708) and

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:1,000; cat. no.

2118) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Specific

antibody against phospho-histone deacetylase 5 (HDAC5; 1:1,000;

cat. no. ab47283) was obtained from Abcam. Secondary antibodies,

including horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (1:3,000;

cat. no. ADI-SAB-100-J) and anti-rabbit IgG (1:3,000; cat. no.

ADI-SAB-300-J), were obtained from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.

Cell culture

Murine C2C12 skeletal muscle cell line (cat. no.

CRL-1772) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection.

Cells were cultured in growth medium (GM; DMEM containing 10% FBS,

100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) in a humidified

incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 until they reached 70%

confluence. To induce differentiation, nearly confluent C2C12 cells

were incubated in DMEM containing 2% heat-inactivated horse serum

(differentiation medium; DM) for varying lengths of time as

previously described (27).

Induction of myogenic differentiation

and observation of morphologic changes

C2C12 myoblasts were seeded in 6-well plates at a

density of 5×104 cells/well. For the myogenic

differentiation, GM was replaced with DM when the cells reached 80%

confluence. Then, the cells were treated with or without SCE at

final concentrations of 0,1,5, or 10 ng/ml for 5 days. Fresh SCE

was added to the DM every 2 days. The morphology of myotubes was

observed using a phase-contrast microscope (Nikon TS2; Nikon

Instruments Inc.). Images were captured at ×50 magnification.

Measurement of cell viability

To determine cytotoxicity, C2C12 myoblasts were

seeded in 96-well plates (1×103 cells/well) and

incubated in the culture medium until they reached 70–80%

confluence as previously described (28). The medium was then changed to a DM,

and the cells were treated with or without SCE (0,1,5, or 10

ng/ml). Following incubation for 5 days, after adding XTT solution

(50 µl) to each well and incubating for 4 h at 37°C, cell viability

was determined by absorbance at 450 nm using a multi-detection

microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC).

Immunofluorescence staining and

determination of the diameter

C2C12 myoblasts cultured in 48-well plates

(3×104 cells/well) were fixed using 3.7%

paraformaldehyde [in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)],

permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and blocked in 5%

bovine serum albumin (BSA; MiliporeSigma) for 3 h at room

temperature as previously described (27). After the cells were blocked in 5%

BSA, they were incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C for 24 h.

Mouse anti-MyHC antibody was used at a 1:200 dilution. MyHC was

detected by incubating the cells with anti-mouse secondary antibody

Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated (1:200; cat. no. A32723; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 4°C for 24 h, and then

4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI; 1 mg/ml) was used to label the

nuclei. Cells were observed using fluorescence Leica DM IRE2

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH) and Nikon Eclipse 50I

microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc.) and images of myotubes were

captured using IM50 software (Leica Microsystems GmbH) and

Nis-Elements D 4.00 software (Nikon Instruments Inc.),

respectively, for size comparison. For myotube diameter, the

average measurement on each slide was calculated from ~25 myotubes;

three fields were randomly selected, and all MyHC-positive

multinucleated cells containing at least three nuclei in each field

were quantified. The data were then converted to a percentage

increase compared with the control (DM).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from C2C12 cells using

TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions and cDNA was

synthesized, followed by qPCR using SYBR® Green Premix

(Bioneer Corp.) with specific primers as previously described

(29). qPCR primers were designed

using Primer3 software (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical

Research). The amplification conditions were 95°C for 5 min,

followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C

for 1 min. Using GAPDH as an internal control, the relative

gene expression was determined using the quantification cycle

(Cq) value (30). The

primer sequences were as follows: GAPDH forward,

5′-TCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGTGGGAGTTGCTGTTGAAGT-3′; MyHC forward,

5′-GCCCAGTGGAGGACAAAATA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTACGTGCTCCTCAGCAT-3′;

MyoD forward, 5′-CGCTCCAACTGCTCTGATG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TAGTAGGCGGTGTCGTAGCC-3′; Myogenin forward,

5′-CTACAGGCCTTGCTCAGCTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGATTGTGGGCGTCTGTAGG-3′;

Myogenic Factor 5 (Myf5) forward, 5′-AGGAAAAGAAGCCCTGAAGC-3′ and

reverse, 5′-GCAAAAAGAACAGGCAGAGG-3′; PGC-1α forward,

5′-CACCAAACCCACAGAAAACAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGGTCAGAGGAAGAGATAAAGTTG-3′; and nuclear respiratory factor

(NRF)-1 forward, 5′-AGGGCGGTGAAATGACCATC-3′ and reverse,

5′CGGCAGCTTCACTGTTGAGG-3′.

Western blotting

C2C12 myoblasts were washed in a culture dish with

cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in cold lysis buffer

containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100,

1 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1% deoxycholate and

protease inhibitors as previously described (29). Samples were incubated in ice for 30

min with lysis buffer and cell debris were separated by

centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein

concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay

Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.). Total protein extracts (20–30 µg)

were then separated using 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF

membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), blocked with 5% non-fat

milk in TBST buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 and 0.1%

Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with specific

primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then washed

thrice and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room

temperature. The membranes were further washed three times and

visualized using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate

(MilliporeSigma). GAPDH was used as a loading control. The density

of western blotting bands was quantified using ImageJ software

(version 2; National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

All experimental tests were performed at least three

times (n=3 per group) and all quantitative data are presented as

the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data were analyzed using

one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test using

SPSS 14.0 (IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

SCE promotes myoblast

differentiation

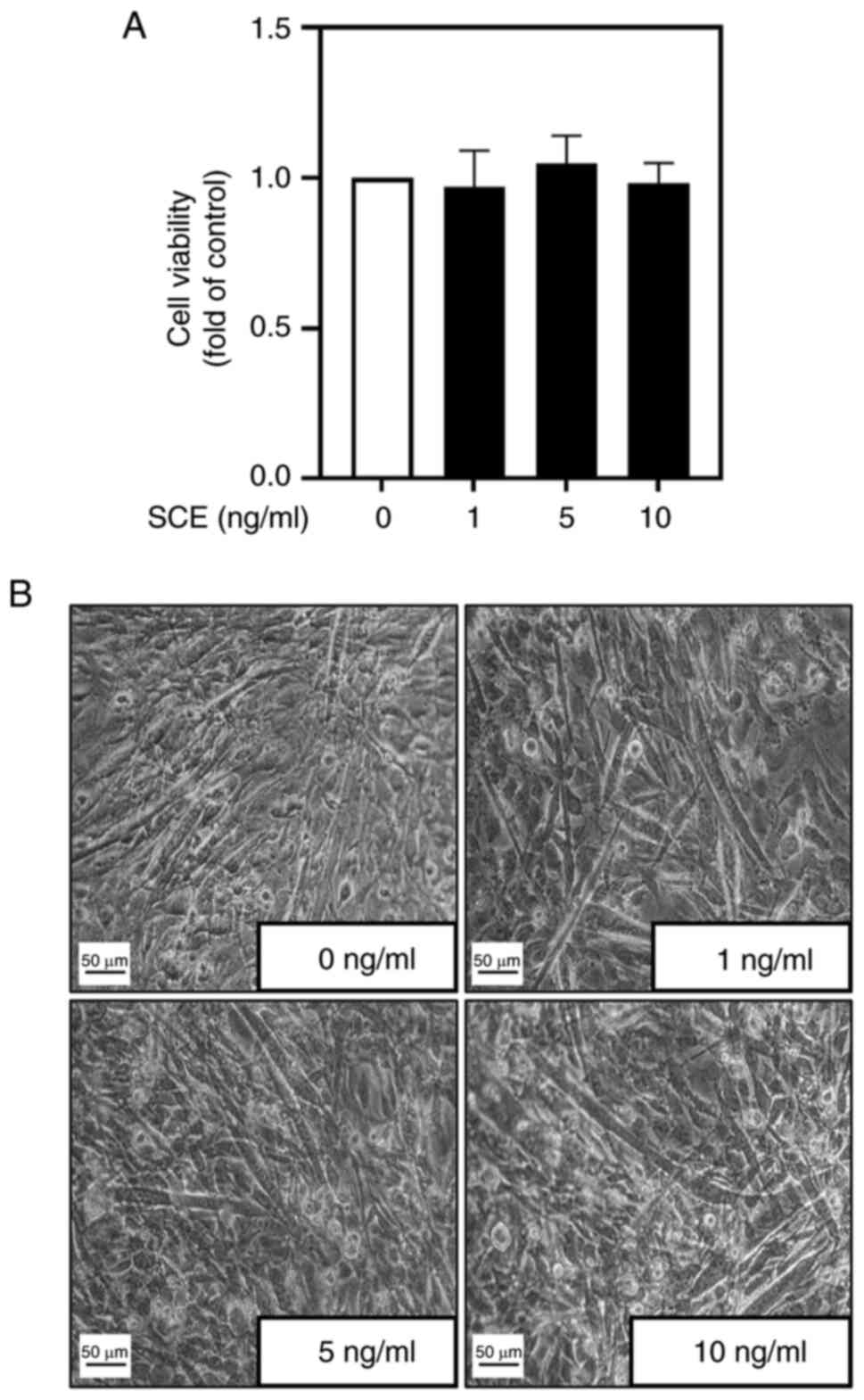

Before investigating the effects of SCE on myoblast

differentiation, its cytotoxicity during myoblast differentiation

was examined. No significant difference was observed in myoblast

viability with the addition of up to 10 ng/ml SCE (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, the morphological

changes in C2C12 cells according to SCE concentration during their

differentiation were examined. During differentiation for 5 days,

treatment with SCE led to the formation of larger and more

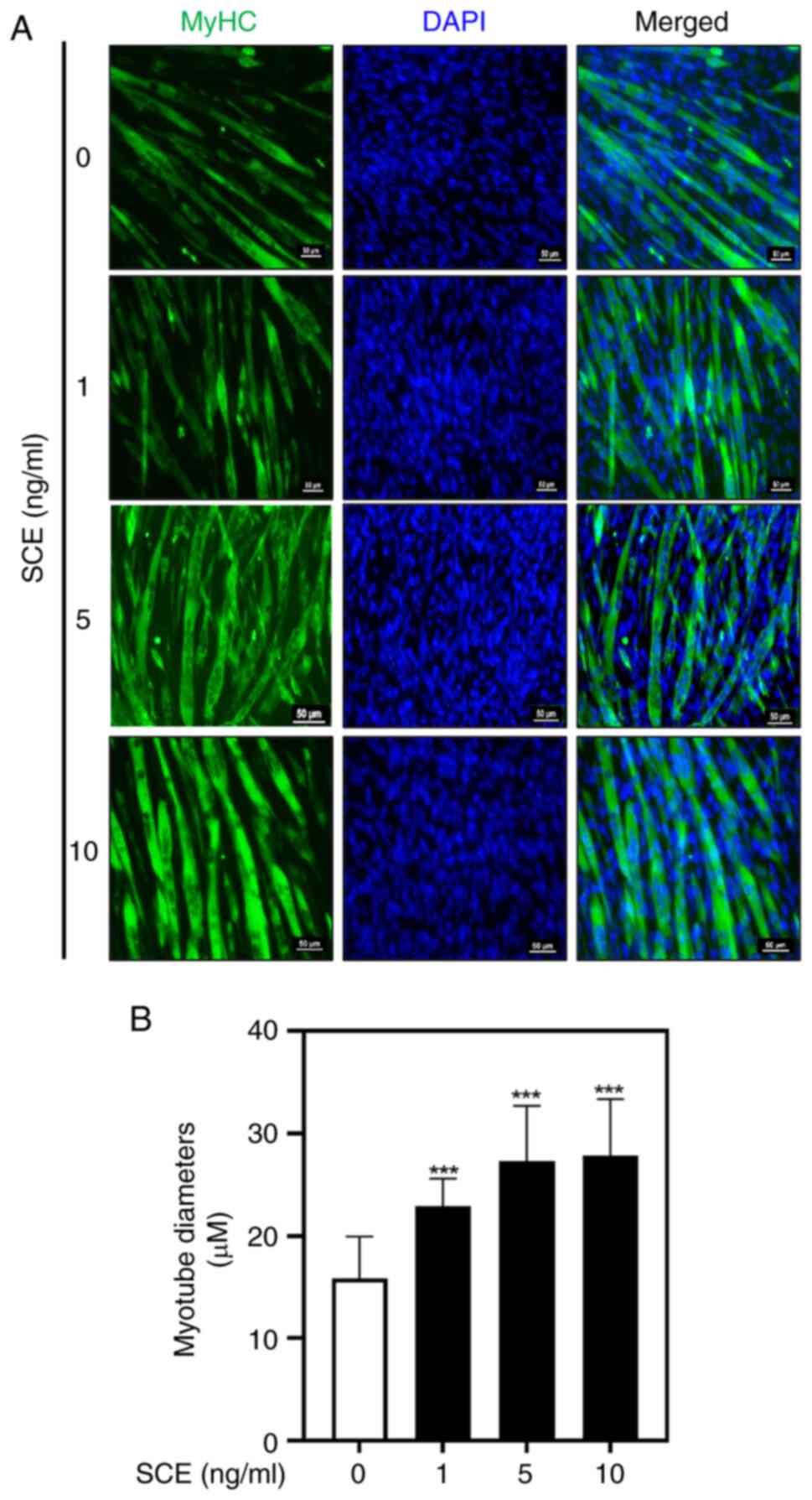

elongated myotubes compared with untreated cells (Fig. 1B). MyHC immunofluorescence staining

was performed to confirm the effect of SCE on myotube formation. As

demonstrated in Fig. 2A, SCE

treatment promoted C2C12 differentiation, as evaluated by the

visualization of MyHC-positive myotubes. DAPI staining was

performed to assess cell density and to determine myotube

formation, as observed in myotubes containing three or more nuclei

(Fig. 2A). On the 5th day of

differentiation, the myotube diameter was significantly increased

in the 1, 5 and 10 ng/ml SCE treatment groups compared with that in

the control group (Fig. 2B).

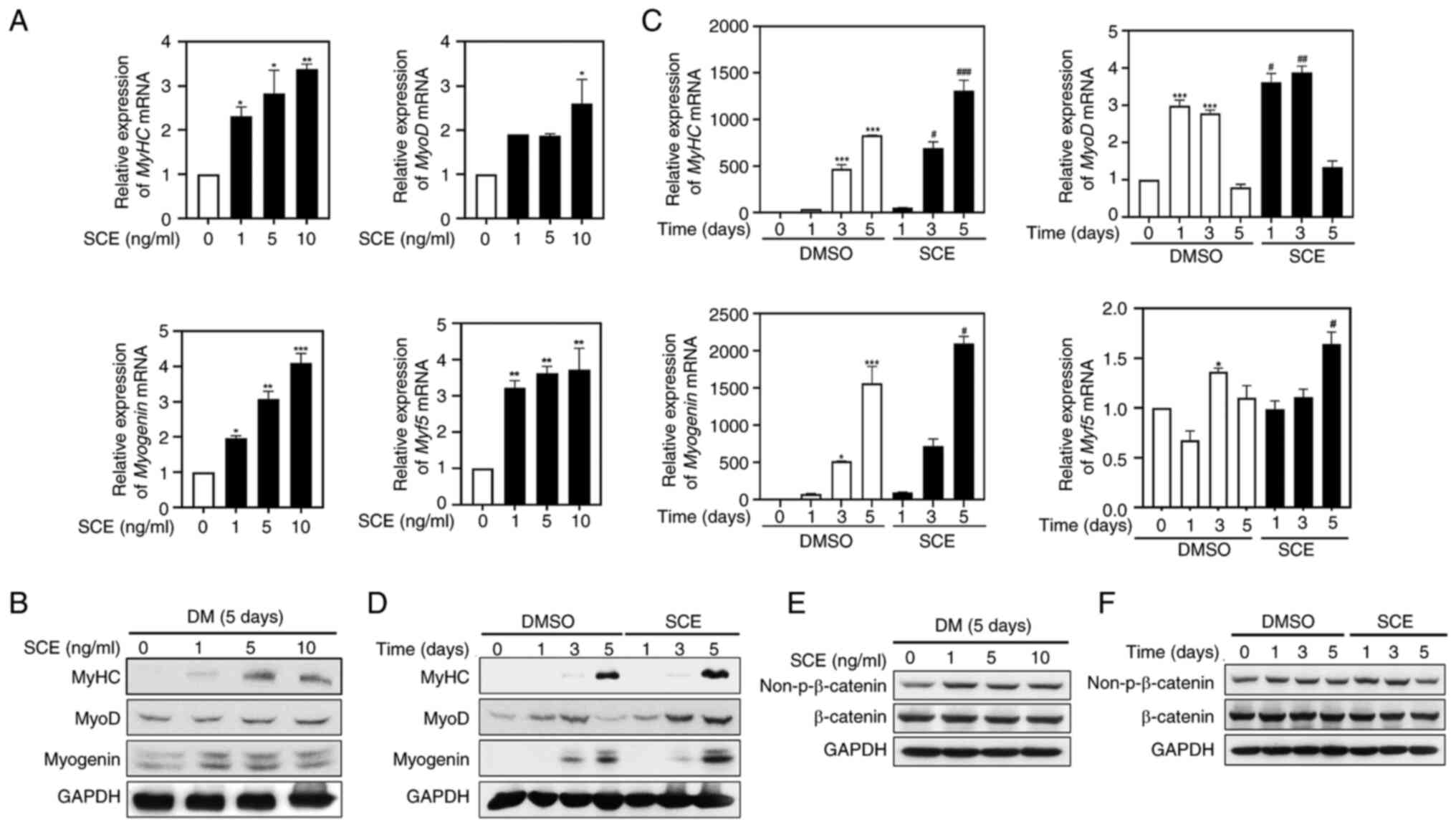

SCE increases the expression of

muscle-specific factors related to myogenesis

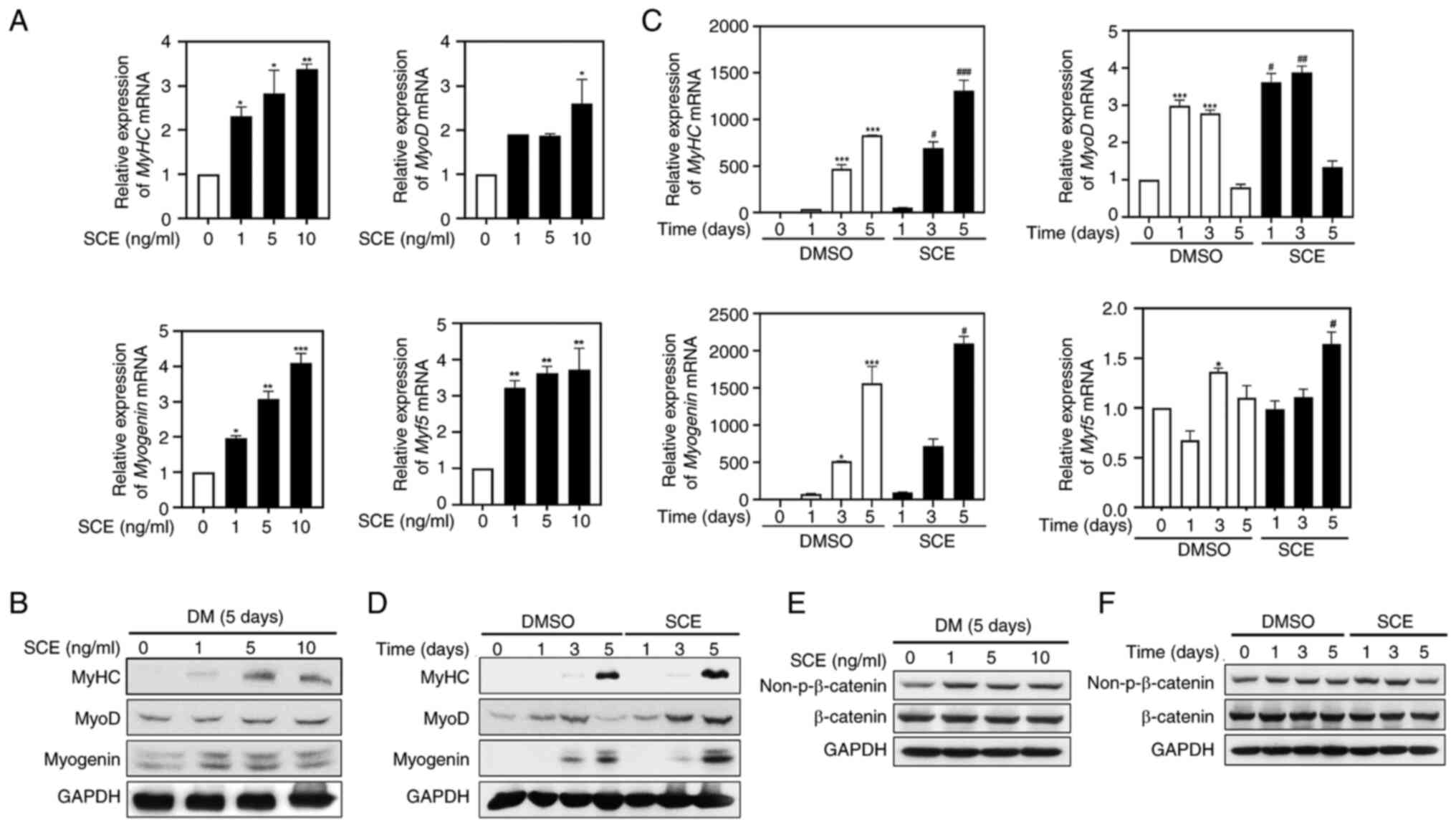

It was investigated whether SCE affects the

expression of muscle-specific genes involved in myogenic

differentiation. As revealed in Fig.

3A, RT-qPCR results revealed that SCE gradually increased the

mRNA expression of MyHC, MyoD, myogenin and Myf5 in a

dose-dependent manner. Protein expression of MyHC, MyoD and

myogenin was also significantly increased compared with that in the

control group, even after treatment with SCE 1 ng/ml for 5 days, as

expected (Fig. 3B). To confirm

changes in the expression of myogenesis factors during the myoblast

differentiation period, C2C12 myoblasts were treated with 10 ng/ml

SCE for 5 days. Myf5 mRNA level and the mRNA and protein levels of

MyHC and myogenin peaked on day 5 compared with those in the

control (Fig. 3C and D). Notably,

MyoD mRNA levels in SCE-treated cells were significantly higher

than those in control cells on days 1 and 3 (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, MyoD protein levels

were significantly upregulated in SCE-treated cells from day 3 to 5

compared with the control (Fig.

3D). Therefore, activation of MyoD is essential for the early

stages of myogenic determination. Next, the activity of β-catenin,

a major protein that regulates myoblast proliferation and myotube

formation, was confirmed according to dose and time via western

blotting (Fig. 3E and F). The

activity of β-catenin was significantly increased at 1, 5 and 10

ng/ml (Fig. 3E) and was activated

compared with the control group on days 1 and 3 after treatment

with 10 ng/ml SCE (Fig. 3F).

| Figure 3.SCE increases the expression of

muscle-specific factors related to myogenesis. C2C12 myoblasts were

induced to differentiate in DMEM containing 2% horse serum, treated

for 5 days with different concentrations of SCE (1, 5 and 10

ng/ml), and analyzed by (A) RT-qPCR (n=3 per group) and (B) western

blotting (n=3 per group). The expression of MyHC, MyoD, myogenin

and Myf5 over the time course of myogenesis was detected through

(C) RT-qPCR (n=3 per group) and (D) western blotting (n=3 per

group) in cells treated with SCE. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. the control group; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. the

SCE-treated group at the corresponding indicated times.

Non-β-catenin and β-catenin were detected by western blotting

depending on (E) the concentration or (F) the time of SCE. SCE,

Saururus chinensis (Lour.) Baill. extract; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; MyHC, myosin heavy chain; MyoD,

myogenic differentiation 1; Myf5, Myogenic Factor 5. |

SCE upregulates the expression of

mitochondria biogenesis factors

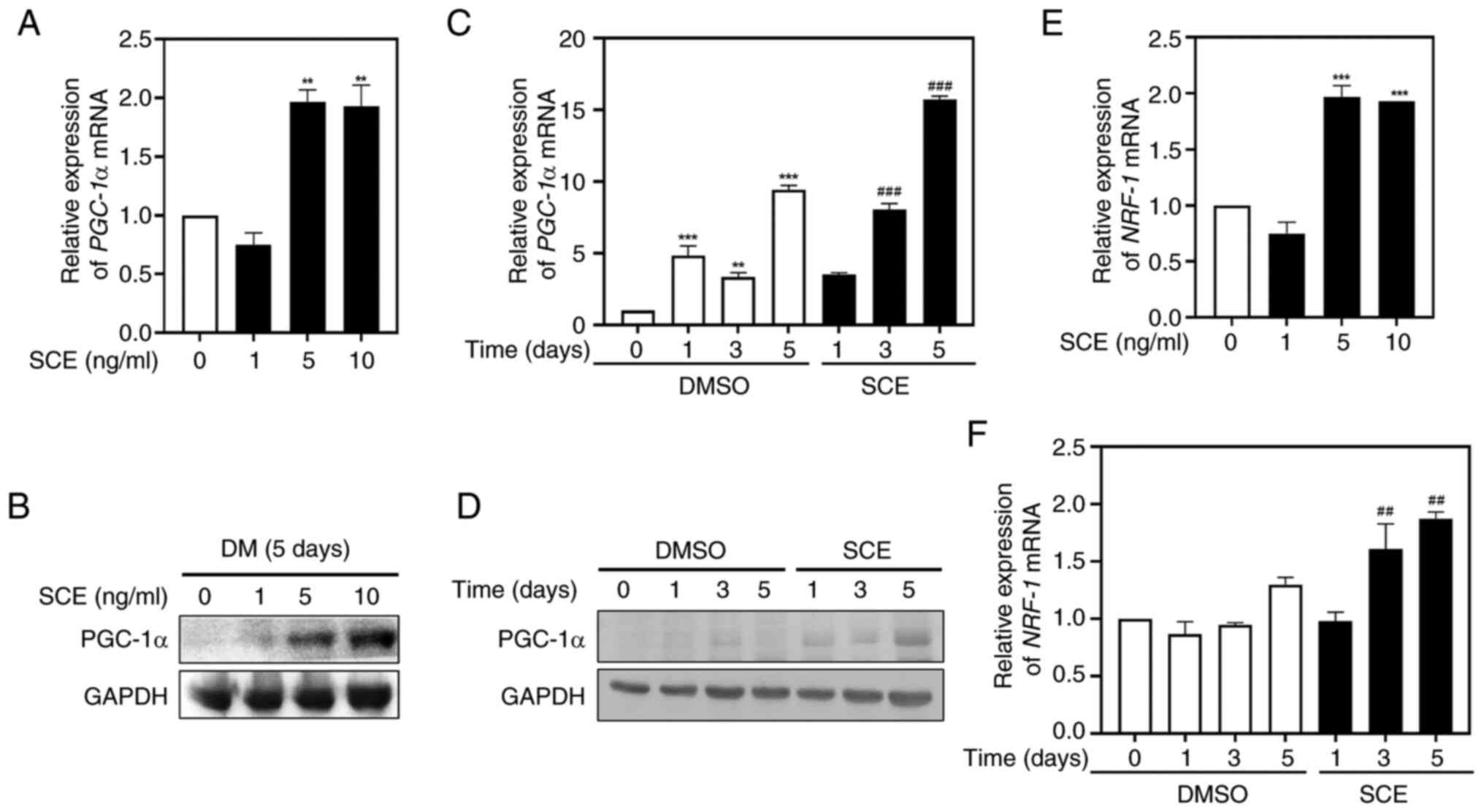

To demonstrate the effects of SCE on mitochondrial

biogenesis during myogenic differentiation, the expression of the

mitochondrial biogenesis transcription factors PGC-1α and NRF-1 at

the mRNA and protein levels were measured using quantitative

RT-qPCR and western blotting. Treatment of myotubes with 5 or 10

ng/ml SCE for 5 days increased the expression of PGC-1α mRNA

(Fig. 4A) and protein (Fig. 4B) compared with the control. In

addition, treatment with SCE 10 ng/ml significantly increased

PGC-1α in a time-dependent manner during myoblast differentiation

(Fig. 4C). As for the protein

levels, the expression of PGC-1α significantly increased in a

time-dependent manner (Fig. 4D),

suggesting the involvement of PGC-1α in myogenic differentiation.

Similar to PGC-1α, the expression of NRF-1 mRNA was also

significantly increased when cells were treated with 5 or 10 ng/ml

SCE for 5 days (Fig. 4E), and

upregulated at 3 or 5 days when cells were treated with 10 ng/ml

SCE during myogenesis (Fig.

4F).

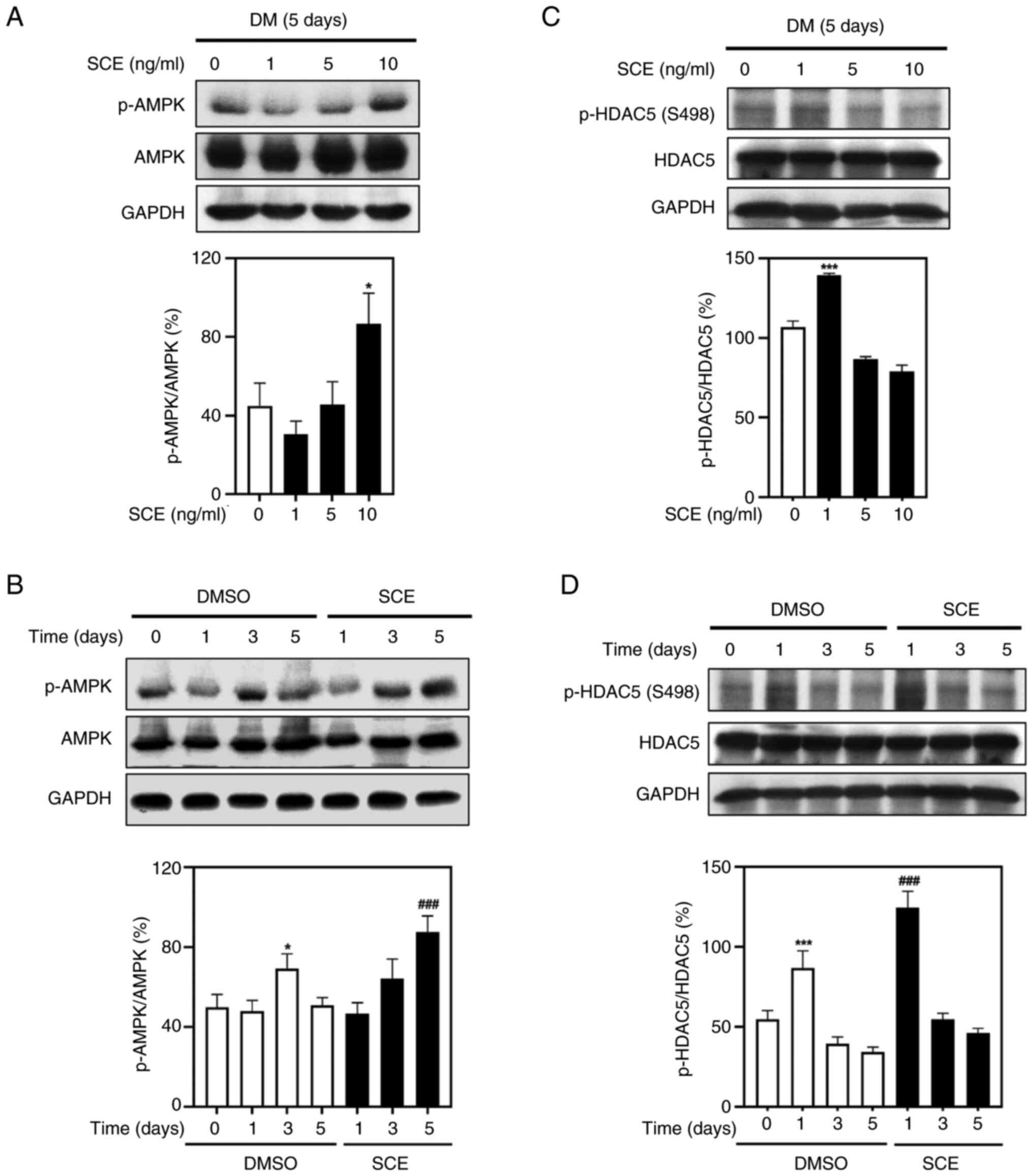

SCE enhances the AMPK-HDAC5 pathways

in myotubes

Next, the effects of SCE on the AMPK-HDAC5 signaling

pathway that activates energy metabolism in myotubes were tested.

Treatment with 1, 5 and 10 ng/ml SCE resulted in increased

phosphorylation of AMPK in the myotubes (Fig. 5A). Treatment with 10 ng/ml SCE

significantly increased the phosphorylation of AMPK compared with

that in the control (Fig. 5B).

Moreover, the phosphorylation of HDAC5 was increased at 1 ng/ml

(Fig. 5C) and was significantly

activated compared with the control group on day 1 (Fig. 5D). These results indicated that SCE

increases energy metabolism associated with mitochondrial

biogenesis in myotubes by activating the AMPK-HDAC5 signaling

pathway.

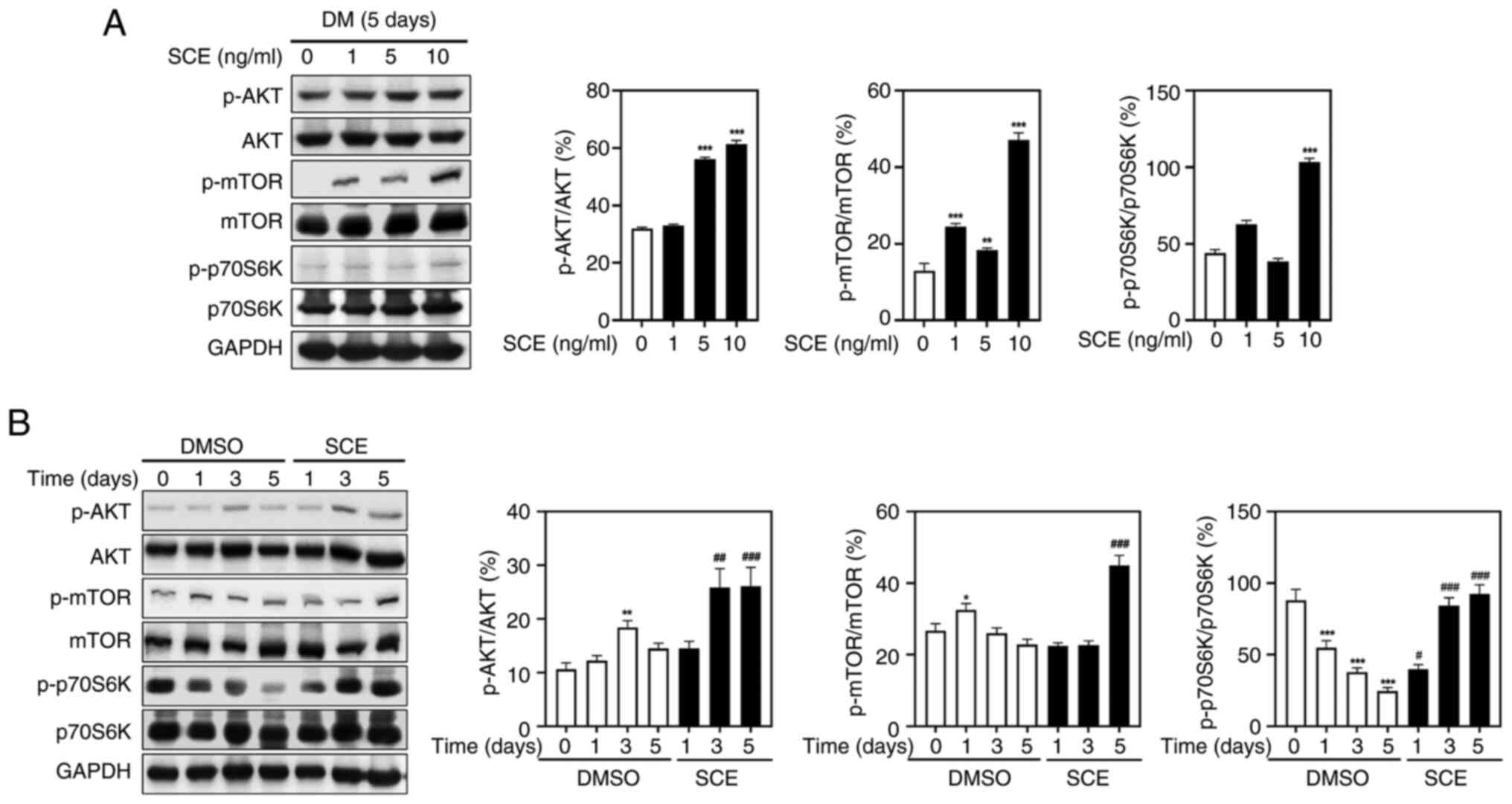

SCE activates muscle protein

synthesis-related biomarkers

To further prove the mechanism by which SCE promotes

formation of C2C12 myotubes, muscle protein turnover-related

biomarkers were evaluated. Western blotting was performed to

confirm whether SCE enhanced the AKT/mTOR pathway, an essential

regulator of protein synthesis and degradation. As demonstrated in

Fig. 6A, the phosphorylation of

AKT, mTOR and p70S6K was increased in a dose-dependent manner

following treatment with SCE. In addition, SCE significantly

increased AKT and mTOR phosphorylation during myogenesis.

Specifically, on day 5 of treatment, SCE increased the

phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR and subsequently activated p70S6K1,

a key downstream target of the AKT/mTOR signaling cascade (Fig. 6B). These data revealed that SCE

enhances differentiation of C2C12 cells by regulating the AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway, which is important for protein synthesis.

Discussion

Herbal medicines used as dietary supplements have

numerous useful effects and have long been known to improve health,

stamina and abnormalities in the elderly (31). SCE is widely used for medicinal

purposes owing to various physiological activities including

anti-oxidant, anticancer, anti-aging and anti-inflammatory

(13–26). In traditional medicine, SCE is used

for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases,

hypertension and angina because it clears the blood and the walls

of blood vessels, along with toxin discharge and diuretic action

(16,32). In addition, SCE protects against

oxidative stress-induced myoblast damage by downregulating ceramide

(27). However, the effects and

mechanisms of action of SCE on skeletal muscle cell differentiation

and function have not yet been investigated. In the present study,

for the first time SCE was investigated for its potential ability

to improve myotube muscle function. SCE promoted the

differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes by increasing MyHC,

MyoD, myogenin, Myf5 and β-catenin levels. These effects are due to

an increase in mitochondrial biogenesis by upregulating the

mitochondrial transcription factors PGC-1α and NRF-1 through

activation of the AMPK and AKT/mTOR signaling pathways and

promotion of protein synthesis.

In order to inhibit muscle wasting, it is necessary

to either stimulate muscle-building pathways or inhibit the

signaling pathways responsible for muscle wasting in the regulation

of muscle metabolism. Satellite cells, such as C2C12 myoblasts,

differentiate into multinucleated fibers and myotubes through

myoblast fusion (33). Muscle

tissue contains satellite cells, which are skeletal muscle-derived

stem cells, and myogenic differentiation begins when satellite

cells are activated (33). During

differentiation, satellite cells and myoblasts are orchestrated by

various myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), including MyoD, Myf5

and myogenin, and structural muscle proteins, including MyHC

(33,34). Mature myotubes express structural

muscle proteins such as MyHC, which are motor proteins and specific

maturation marker proteins of thick muscle filaments (33,34).

Furthermore, β-catenin acts as a molecular switch that regulates

the transition from cell proliferation to myogenic differentiation

(35). In the present study, SCE

treatment significantly increased the mRNA and/or protein levels of

MyHC, MyoD, myogenin, Myf5 and β-catenin in C2C12 myotubes

(Fig. 3), suggesting that SCE

promotes myoblast differentiation. However, further experiments on

MRFs and the regulation of their signaling are needed to improve

elucidation of the impact of SCE on myogenesis and metabolism.

PGC-1α is a key transcriptional regulator of several

genes involved in various physiological responses related to energy

homeostasis, thermoregulation, lactate and fatty acid metabolism,

muscle growth and mitochondrial biogenesis (36). In skeletal muscle, PGC-1α increases

energy expenditure by increasing the rates of respiration and

mitochondrial biogenesis and interacts with NRF-1, a transcription

factor regulating the expression of several mitochondrial genes

(36,37). AMPK acts as an energy switch, which

is a key energy sensor controlling metabolic homeostasis at

cellular and systemic levels, regulating processes such as cell

growth, lipid-glucose metabolism and autophagy (38,39).

Specifically, in skeletal muscles, mitochondrial biogenesis

provides cells with ATP, which ultimately promotes AMPK activation

(38,39). AMPK inhibition downregulates

myogenin transcription and myogenesis, mainly through

phosphorylation of HDAC5 mediated by AMPKα1, meaning that AMPK is a

key molecular target to promote myogenesis and muscle regeneration

(40). In the present study, SCE

treatment of C2C12 myotubes increased the activation of PGC-1α,

NRF-1, AMPK and HDAC5 in a time- and concentration-dependent manner

(Figs. 4 and 5), indicating that the promotion of

myogenic differentiation by SCE is related to the enhancement of

mitochondrial biogenesis. However, changes in mitochondrial

biogenesis, caused by SCE treatment need to be further confirmed to

improve understanding of the role of the drug in muscle energy

metabolism.

AMPK is involved not only in mitochondrial

biogenesis but also in the synthesis and wasting metabolism of

skeletal muscle through the regulation of several downstream

targets, such as the PI3K/AKT pathway. AMPK plays an important role

in regulating skeletal muscle development and growth and regulating

muscle mass and regeneration by influencing anabolic and catabolic

cellular processes (41). AKT

plays an important role as a promyogenic kinase, and AKT signaling

is contributed to heterodimerization of MyoD/E-proteins and

alteration in chromatin remodeling at muscle-specific loci

(42,43). AKT/mTOR/p70S6K pathway is important

for the differentiation of myoblasts and hypertrophy of myotubes

(44). mTOR is a kinase downstream

of AKT, which phosphorylates 4E-BP1 and p70S6K thereby inducing

initiation of protein synthesis (45). In addition, AKT pathways prevent

muscle atrophy by inhibiting atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases and

FoxO transcriptional factors (45). In myostatin knockout mice, an

increase in AKT/mTOR/p70S6K signaling was observed (46). SCE induced the phosphorylation of

AKT, mTOR and p70 S6K in a concentration- and time-dependent manner

(Fig. 6). These results indicated

that SCE enhanced myogenic differentiation through the AKT/mTOR

protein synthesis signaling pathway.

In conclusion, the present study is the first, to

the best of the authors' knowledge, to reveal that SCE regulates

muscle differentiation, mitochondrial biogenesis and protein

synthesis. SCE significantly increased the expression of MyoD,

myogenin and MyHC in myotubes, as well as the expression of PGC-1α

and NRF-1, through the activation of AMPK and AKT/mTOR signaling

pathways. These results suggested that SCE improves muscle function

by enhancing myoblast differentiation and energy metabolism.

However, further in vitro/in vivo studies on the mechanism

of action of SCE in pathological conditions such as aging, energy

and nutritional imbalance and muscle loss are needed to clearly

understand the mechanisms by which SCE regulates muscle

differentiation, mitochondrial biogenesis and protein synthesis. A

limitation of the present study was that more specific experimental

evidence is needed to support the role of the AMPK-HDAC5 and

AKT/mTOR/p70S6K pathways, such as the use of inhibitors or

activators of these pathways. In addition, it will be necessary to

confirm the effectiveness of SCE in suppressing muscle loss and

enhancing muscle strength through additional in vivo

experiments.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Wonkwang University in

2022 (grant no. 2022-10).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JYK and MSL designed the study and revised the

manuscript. SYE, CHC, YHC and GDP performed the experiments. SYE,

CHC and CHL analyzed the data. SYE and CHC drafted figures. JYK and

MSL wrote the manuscript. JYK and MSL confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All methods were performed in accordance with

relevant international and national guidelines and regulations.

Because the present study was an in vitro experiment that

did not involve animals or humans, no animal or human ethics

approval was required. SC is stored at the ‘National Institute of

Biological Resources’ (Institution identification number: 50520),

and the specimen was collected from farms on Jeju Island, not from

its native habitat, grown for medicinal purposes. SC Methanolic

(99%) whole-plant extract (KPM046-069) was obtained from the Korea

Plant Extract Bank, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and

Biotechnology (Cheongju) for research purposes. Experimental

studies were conducted according to the Natural Products Central

Bank (NPCB)'s ‘Standard operating procedure (2023 revised edition)’

(https://www.kobis.re.kr/npcb/uss/notice/library.do).

The NPCB does not collect or damage internationally endangered

species designated and announced by the Minister of Environment in

accordance with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered

Species of Wild Plants (CITES) (http://www.cites.org) and the international Union for

Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) standards (https://s3.amazonaws.com/iucnredlist-newcms/staging/public/attachments/3154/reg_guidelines_en.pdf),

and complies with permit procedures for protected species.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hargreaves M and Spriet LL: Skeletal

muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Nat Metab. 2:817–828.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Thyfault JP and Bergouignan A: Exercise

and metabolic health: Beyond skeletal muscle. Diabetologia.

63:1464–1474. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Newman AB, Kupelian V, Visser M, Simonsick

EM, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Rubin SM and Harris

TB: Strength, but not muscle mass, is associated with mortality in

the health, aging and body composition study cohort. J Gerontol A

Biol Sci Med Sci. 61:72–77. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, Giovannini

S, Tosato M, Capoluongo E, Bernabei R and Onder G: Sarcopenia as a

risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: Results from the

ilSIRENTE study. Clin Nutr. 31:652–658. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Peng P, Hyder O, Firoozmand A, Kneuertz P,

Schulick RD, Huang D, Makary M, Hirose K, Edil B, Choti MA, et al:

Impact of sarcopenia on outcomes following resection of pancreatic

adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 16:1478–1486. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S,

Morley JE, Newman AB, Abellan van Kan G, Andrieu S, Bauer J,

Breuille D, et al: Sarcopenia: An undiagnosed condition in older

adults. Current consensus definition: Prevalence, etiology, and

consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med

Dir Assoc. 12:249–256. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mankhong S, Kim S, Moon S, Kwak HB, Park

DH and Kang JH: Experimental models of sarcopenia: Bridging

molecular mechanism and therapeutic strategy. Cell. 9:13852020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ma J, Meng X, Kang SY, Zhang J, Jung HW

and Park YK: Regulatory effects of the fruit extract of Lycium

chinense and its active compound, betaine, on muscle

differentiation and mitochondrial biogenesis in C2C12 cells. Biomed

Pharmacother. 118:1092972019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shin EJ, Jo S, Choi S, Cho CW, Lim WC,

Hong HD, Lim TG, Jang YJ, Jang M, Byun S and Rhee Y: Red ginseng

improves exercise endurance by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis

and myoblast differentiation. Molecules. 25:8652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kim YH, Jung JI, Jeon YE, Kim SM, Oh TK,

Lee J, Moon JM, Kim TY and Kim EJ: Gynostemma pentaphyllum extract

and Gypenoside L enhance skeletal muscle differentiation and

mitochondrial metabolism by activating the PGC-1α pathway in C2C12

myotubes. Nutr Res Pract. 16:14–32. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

National Institute of Biological

Resources, . Korean Red List of Threatened Species. 2nd edition.

National Institute of Biological Resources 2014; 2nd edition. Suh

MH, Lee BY, Kim ST, Park CH, Oh HK, Kim HY, Lee JH and Lee SY:

National Institute of Biological Resources; Incheon: 2014

|

|

12

|

Chang CS, Lee JS, Park TY and Kim H:

Reconsideration of rare and endangered plant species in Korea based

on the IUCN red list categories. Korean J Pl Taxon. 31:107–142.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ryu SY, Oh KS, Kim YS and Lee BH:

Antihypertensive, vasorelaxant and inotropic effects of an

ethanolic extract of the roots of Saururus chinensis. J

Ethnopharmacol. 118:284–289. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yoo HJ, Kang HJ, Jung HJ, Kim K, Lim CJ

and Park EH: Anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and

anti-nociceptive activities of Saururus chinensis extract. J

Ethnopharmacol. 120:282–286. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nho JH, Lee HJ, Jung HK, Jang JH, Lee KH,

Kim AH, Sung TK and Cho HW: Effect of Saururus chinensis

leaves extract on type II collagen-induced arthritis mouse model.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 19:22019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cheng Y, Yin Z, Jiang F, Xu J, Chen H and

Gu Q: Two new lignans from the aerial parts of Saururus

chinensis with cytotoxicity toward nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Fitoterapia. 141:1043442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sung SH, Lee EJ, Cho JH, Kim HS and Kim

YC: Sauchinone, a lignan from Saururus chinensis, attenuates

CCl4-induced toxicity in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Biol

Pharm Bull. 23:666–668. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hwang BY, Lee JH, Nam JB, Hong YS and Lee

JJ: Lignans from Saururus chinensis inhibiting the

transcription factor NF-kappaB. Phytochemistry. 64:765–771. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Quan Z, Lee YJ, Yang JH, Lu Y, Li Y, Lee

YK, Jin M, Kim JY, Choi JH, Son JK and Chang HW: Ethanol extracts

of Saururus chinensis suppress ovalbumin-sensitization

airway inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 132:143–149. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Alaklabi A, Arif IA, Ahamed A, Surendra

Kumar R and Idhayadhulla A: Evaluation of antioxidant and

anticancer activities of chemical constituents of the Saururus

chinensis root extracts. Saudi J Biol Sci. 25:1387–1392. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang J, Rho Y, Kim MY and Cho JY: TAK1 in

the AP-1 pathway is a critical target of Saururus chinensis

(Lour.) Baill in its anti-inflammatory action. J Ethnopharmacol.

279:1144002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yoo SR, Ha H, Shin HK and Seo CS:

Anti-inflamatory activity of neolignan compound isolated from the

roots of Saururus chinensis. Plants (Basel). 9:9322020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jung YW, Lee BM, Ha MT, Tran MH, Kim JA,

Lee S, Lee JH, Woo MH and Min BS: Lignans from Saururus

chinensis exhibit anti-inflammatory activity by influencing the

Nrf2/HO-1 activation pathway. Arch Pharm Res. 42:332–343. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Choi MS, Kim EC, Lee HS, Kim SK, Choi HM,

Park JH, Han JB, An HJ, Um JY, Kim HM, et al: Inhibitory effects of

Saururus chinensis (LOUR.) BAILL on the development of

atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice. Biol Pharm

Bull. 31:51–56. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jeong HJ, Koo BS, Kang TH, Shin HM, Jung S

and Jeon S: Inhibitory effects of Saururus chinensis and its

components on stomach cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 22:256–261.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang L, Cheng D, Wang H, Di L, Zhou X, Xu

T, Yang X and Liu Y: The hepatoprotective and antifibrotic effects

of Saururus chinensis against carbon tetrachloride induced

hepatic fibrosis in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 126:487–491. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Jung MH, Song MC, Bae K, Kim HS, Kim SH,

Sung SH, Ye SK, Lee KH, Yun YP and Kim TJ: Sauchinone attenuates

oxidative stress-induced skeletal muscle myoblast damage through

the down-regulation of ceramide. Biol Pharm Bull. 34:575–579. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu H, Lee SM and Joung H: 2-D08 treatment

regulates C2C12 myoblast proliferation and differentiation via the

Erk1/2 and proteasome signaling pathways. J Muscle Res Cell Motil.

42:193–202. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kim JY, Cheon YH, Ahn SJ, Kwak SC, Chung

CH, Lee CH and Lee MS: Harpagoside attenuates local bone Erosion

and systemic osteoporosis in collagen-induced arthritis in mice.

BMC Complement Med Ther. 22:2142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Patel HP,

Shavlakadze T, Cooper C and Grounds MD: New horizons in the

pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of sarcopenia. Age Ageing.

42:145–150. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Oh KS, Choi YH, Ryu SY, Oh BK, Seo HW, Yon

GH, Kim YS and Lee BH: Cardiovascular effects of lignans isolated

from Saururus chinensis. Planta Med. 74:233–238. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Dumont NA, Bentzinger CF, Sincennes MC and

Rudnicki MA: Satellite cells and skeletal muscle regeneration.

Compr Physiol. 5:1027–1059. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Langley B, Thomas M, Bishop A, Sharma M,

Gilmour S and Kambadur R: Myostatin inhibits myoblast

differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. J Biol Chem.

277:49831–49840. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tanaka S, Terada K and Nohno T: Canonical

Wnt signaling is involved in switching from cell proliferation to

myogenic differentiation of mouse myoblast cells. J Mol Signal.

6:122011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kang C and Li Ji L: Role of PGC-1α

signaling in skeletal muscle health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

1271:110–117. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Taherzadeh-FardE SC, Akkad DA, Wieczorek

S, Haghikia A, Chan A, Epplen JT and Arning L: PGC-1alpha

downstream transcription factors NRF-1 and TFAM are genetic

modifiers of Huntington disease. Mol Neurodegener. 6:322011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hardie DG, Ross FA and Hawley SA: AMPK: A

nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 13:251–262. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gasparrini M, Giampieri F, Alvarez Suarez

J, Mazzoni L, Y Forbes Hernandez T, Quiles JL, Bullon P and Battino

M: AMPK as a new attractive therapeutic target for disease

prevention: The role of dietary compounds AMPK and disease

prevention. Curr Drug Targets. 17:865–889. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fu X, Zhao JX, Liang J, Zhu MJ, Foretz M,

Viollet B and Du M: AMP-activated protein kinase mediates myogenin

expression and myogenesis via histone deacetylase 5. Am J Physiol

Cell Physiol. 305:C887–C895. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tao R, Gong J, Luo X, Zang M, Guo W, Wen R

and Luo Z: AMPK exerts dual regulatory effects on the PI3K pathway.

J Mol Signal. 5:12010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Simone C, Forcales SV, Hill DA, Imbalzano

AN, Latella L and Puri PL: p38 pathway targets SWI-SNF

chromatin-remodeling complex to muscle-specific loci. Nat Genet.

36:738–743. 2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bae GU, Lee JR, Kim BG, Han JW, Leem YE,

Lee HJ, Ho SM, Hahn MJ and Kang JS: Cdo interacts with APPL1 and

activates Akt in myoblast differentiation. Mol Biol Cell.

21:2399–2411. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Glass DJ: Signalling pathways that mediate

skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Nat Cell Biol. 5:87–90.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonalez M, Kline WO,

Stover GL, Bauerlein R, Zlotchenko E, Scrimgeour A, Lawrence JC,

Glass DJ and Yancopoulos GD: Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial

regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle

atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 3:1014–1019. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lipina C, Kendall H, McPherron AC, Taylor

PM and Hundal HS: Mechanisms involved in the enhancement of

mammalian target of rapamycin signalling and hypertrophy in

skeletal muscle of myostatin-deficient mice. FEBS Lett.

584:2403–2408. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|