Introduction

Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs),

currently used for the treatment of asthma and allergic rhinitis,

demonstrate anticancer effects in in vitro and in

vivo models (1,2). Overexpression of 5-lipoxygenase, a

leukotriene synthesis enzyme, and leukotriene receptors are found

in numerous types of cancer, including breast cancer (BC) (3). A large population study in Taiwanese

patients with asthma using LTRAs identified a decreased risk of

breast, lung, colorectal and liver cancer compared with non-LTRA

users (4). In this study, a hazard

ratio of LTRA users was 0.31 and the increase of cumulative dose

progressively decreased cancer risk. Two subsequent large

retrospective cohort studies also reported a lower risk of cancers

in asthmatic patients taking LTRAs. Korean patients showed

significant lower risk of cancers after taking high dose of LTRAs

(adjusted HR=0.56) or 3 years or more of LTRA use (adjusted HR=0.68

after 3 years and 0.33 after 5 years) (5). In Japanese patients, the high

accumulative dose of LTRAs was associated with a decrease in risk

of cancer (adjusted HR=0.57) (6).

Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (CysLT1R), a receptor of

leukotriene D4, is highly expressed in breast tumor tissues

compared with in normal breast tissues, and its expression is

greater in higher grade tumors (3). MDA-MB-231, a triple-negative BC

(TNBC) cell line, expresses CysLT1R but not CysLT2R (3). Our previous study reported the

apoptotic and antiproliferative effects of two LTRAs, montelukast

and zafirlukast, on MDA-MB-231 cells (7). In addition, LTRAs have been reported

to induce the apoptosis of glioblastoma and lung cancer cells by

reducing ERK1/2 phosphorylation and Bcl-2 levels (8,9).

Zafirlukast has also been shown to induce

G0/G1 cell cycle arrest by upregulating p53

and p21 expression in both glioblastoma A172 and U-87 MG cells, and

p27 expression in U-87 MG cells (10). Similarly, only zafirlukast can

induce G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231

cells (7). However, the mechanisms

underlying the cytotoxic and antiproliferative effects of LTRAs on

MDA-MB-231 cells remain unknown. The present study aimed to compare

the effects of montelukast and zafirlukast on the molecular

mechanisms regulating proliferation and death in MDA-MB-231

cells.

Materials and methods

Cell line and culture

MDA-MB-231 cells (cat. no. HTB-26) were obtained

from American Type Culture Collection and cultured in DMEM (cat.

no. 12800-017) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (cat.

no. 15140) and 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. 10270) (all Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Chemicals

Montelukast (cat. no. SML0101) and zafirlukast (cat.

no. Z4152) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA), and were

dissolved in DMSO (cat. no. D4540; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA).

GSK2606414 (cat. no. HY-18072) was purchased from MedChemExpress.

The final concentration of DMSO was 0.04% (v/v) in culture media,

as previously described (7).

Cell treatment

Cells were treated with DMSO, montelukast at 20 µM,

or zafirlukast at 20 µM at 37°C for 3 h in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR analysis, 6, 12 or 48 h in western

blotting, and 6 or 12 h in flow cytometric analysis and apoptosis

assay. GSK2606414 was treated 1 h prior to the addition of

montelukast or zafirlukast.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection

Cells were transfected with 50 nM ON-TARGETplus

siRNA Human DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 (DDIT3, also known as

C/EBP homologous protein or CHOP) SMARTpool (cat. no.

L-004819-00-0005) or ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting Control Pool (cat.

no. D-001810-10-05; both GE Healthcare Dharmacon, Inc.; Table I). All four siRNAs were mixed in

the same reaction. DharmaFECT 4 Transfection Reagent (cat. no.

T-2004-02; GE Healthcare Dharmacon, Inc.) was used according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Cells were transfected at 37°C for 48

h for gene expression studies and for 96 h before determining

protein expression. Cells were immediately treat with DMSO,

montelukast at 20 µM, or zafirlukast at 20 µM for 12 h.

| Table I.siRNA target sequences. |

Table I.

siRNA target sequences.

| siRNA | Target sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| ON-TARGET plus

Non-targeting Pool (control) |

UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA |

|

|

UGGUUUACAUGUUGUGUGA |

|

|

UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCUGA |

|

|

UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCCUA |

| ON-TARGET plus

Human DDIT3 |

GGUAUGAGGACCUGCAAGA |

|

|

CACCAAGCAUGAACAAUUG |

|

|

GGAAACAGAGUGGUCAUUC |

|

|

CAGCUGAGUCAUUGCCUUU |

Western blotting

Proteins were harvested from cells and detected as

previously described (10).

Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford Protein Assay

(cat. no. 5000006; Bio-Rad) and 25 µg protein were loaded into each

lane. Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry

milk (cat. no. 1706404; Bio-Rad) in 0.5% TBS-T at 4°C overnight and

probed with primary antibodies against phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2

(rabbit; 1:4,000; cat. no. 4370), ERK1/2 (rabbit; 1:2,000; cat. no.

4695), Bcl-2 (rabbit; 1:600; cat. no. 4223), PARP-1 (rabbit;

1:2,000; cat. no. 9542), LC3-A/B (rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no. 12741),

activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6; rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no.

65880), CHOP (mouse; 1:1,000; cat. no. 2895), p21 (rabbit; 1:1,000;

cat. no. 2947), p27 (rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no. 3686), CDK4 (rabbit;

1:1,000; cat. no. 12790), cyclin D1 (rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no.

2978) (all Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and cyclin E (mouse;

1:1,000; cat. no. 05-363; Merck KGaA) for 2 h at room temperature.

β-actin (rabbit; 1:10,000; cat. no. 4970) and β-tubulin (mouse;

1:5,000; cat. no. 86298) (both Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.)

were incubated for 45 min at room temperature. After that,

membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse conjugated

with horseradish peroxidase enzymes for 1 h at room temperature

(goat; 1:4,000; cat. no. 111-035-003 or 115-035-003; Jackson

ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Bands were visualized using Clarity

Western ECL substrate (cat. no. 1705061; Bio-Rad) and quantified

using ImageJ software (version 1.54; National Institutes of Health

and the Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation).

β-actin or β-tubulin was used as loading controls depending on the

molecular weight of proteins of interest. The band intensity was

normalized to the expression of the loading control.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were detached with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (cat.

no. 25300054; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C

for 2 min and centrifuged at 320 × g for 10 min at room

temperature. The levels of monomeric JC-1, caspase 3/7 activity,

autophagic LC3, p-ATM and p-histone H2AX (H2AX) were measured using

Guava Mitochondrial Depolarization Kit, Guava® Caspase

3/7 FAM Kit (cat. no. 4500-0540; Merck Millipore; Merck KGaA),

FlowCellect Histone H2AX Phosphorylation Assay Kit (cat. no.

FCCS100182; Merck Millipore; Merck KGaA), phycoerythrin-conjugated

anti-p-ATM (Ser1981) (cat. no. FCMAB110P; Merck Millipore; Merck

KGaA) and FlowCellect™ Autophagy LC3 Antibody-based Assay Kit (cat.

no. FCCH100171; Merck Millipore; Merck KGaA), respectively. All

tests were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. The

percentage of dead cells was determined by 7-aminoactinomycin D

(7-AAD) staining when assessing mitochondrial depolarization. Cells

were assessed using the Guava® easyCyte 5HT benchtop

flow cytometer with InCyte 3.1 (both Cytek Biosciences). A minimum

of 2,000 events was analyzed for each sample.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

Total RNA from cells was extracted using the Total

RNA Mini kit (cat. no. RB300; Geneaid Biotech Ltd.) according to

the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA synthesis and qPCR were performed

using superscript III reverse transcriptase (cat. no. 18080-044;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and SensiFAST SYBR

Lo-ROX (cat. no. BIO-94005; Bioline; Meridian Bioscience) on an

Applied Biosystems Real-time PCR 7500 system (Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as previously described (11). All primers are listed in Table II. The thermocycling conditions

were as follows: Initial denaturation at 50°C for 2 min and 95°C

for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 58°C for 1

min, with a melting curve stage of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 1

min. The Cq value of each target gene was normalized to the

expression of GAPDH. Relative fold-change was calculated against

untreated cells based on the 2−ΔΔCq method (12).

| Table II.Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR primers. |

Table II.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR primers.

| Gene | Forward primer,

5′-3′ | Reverse primer,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| GAPDH |

AGCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGAC |

CGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCG |

| Ki-67 |

CTTTGGGTGCGACTTGACG |

GTCGACCCCGCTCCTTTT |

| PCNA |

GGCCGAAGATAACGCGGATAC |

GGCATATACGTGCAAATTCACCA |

| ATF4 |

CTTCCTGAGCAGCGAGGTG |

TCTCCAACATCCAATCTGTCC |

| ATF6 |

TCGGTCAGTGGACTCTTATT |

CCAGTGACAGGCTTATCTTC |

| CHOP |

AAGGCACTGAGCGTATCATGT |

TGAAGATACACTTCCTTCTTGAACA |

| GADD34 |

GAGGAGGCTGAAGACAGTGG |

AATTGACTTCCCTGCCCTCT |

| PERK |

GTCCGGAACCAGACGATGAG |

GGCTGGATGACACCAAGGAA |

| XBP-1s |

TCTGCTGAGTCCGCAGCAG |

GAAAAGGGAGGCTGGTAAGGAAC |

| CAT |

CCATTATAAGACTGACCAGGGC |

AGTCCAGGAGGGGTACTTTCC |

| GST |

GGATCTGCTGGAACTGCTTATCAT |

TGTCCGTGACCCCTTAAAATCTT |

| GR |

AACATCCCAACTGTGGTCTTCAGC |

TTGGTAACTGCGTGATACATCGGG |

| GPx1 |

TTCCCGTGCAACCAGTTTG |

TTCACCTCGCACTTCTCGAA |

| SOD |

CTGAAGGCCTGCATGGATTC |

CCAAGTCTCCAACATGCCTCTC |

Apoptosis assay

Floating cells and cells detached with 0.05%

trypsin-EDTA were collected and centrifuged at 320 × g for 10 min

at room temperature. Pellets were washed twice in Annexin V binding

buffer, and were then with Annexin V-FITC (cat. no. 556419) and

7-AAD (cat. no. 51-68981E) (both BD Biosciences). The percentage of

Annexin V positive cells representing early and late apoptotic

cells was determined using a BD Accuri C6 Plus with BD Accuri C6

Plus Software version 1.0.1 (both BD Biosciences). A minimum of

5,000 events/sample were collected.

Dichlorofluorescein (DCFH) assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well clear bottom black

plates and incubated with 20 µM DCFH diacetate (cat. no. D6883;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in phenol red-free MEM (cat. no.

12800-017; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in the dark before being

treated with DMSO, montelukast at 20 µM, or zafirlukast at 20 µM

for 3 h. The DCF fluorescence intensity was detected using a

Varioskan™ Flash spectral scanning Multimode Reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) with 490/535 nm excitation/emission wavelengths.

The DCF fluorescence intensity of each treatment was normalized to

fluorescence intensity of untreated cells.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n≥3). Data

were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc

test using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (Dotmatics). The level of

significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

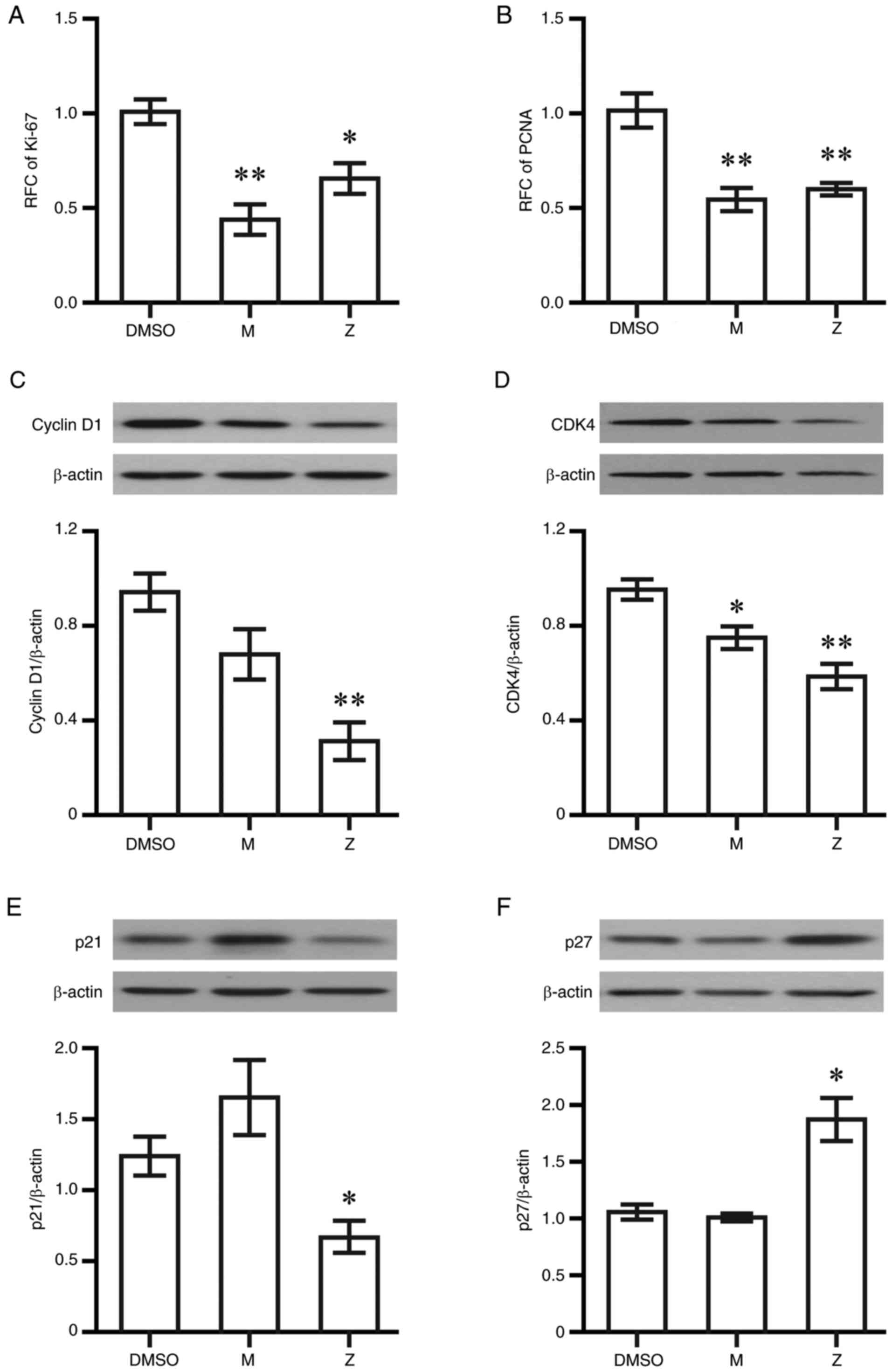

Zafirlukast induces p27 expression and

decreases cyclin D1 expression

Although both montelukast and zafirlukast at 20 µM

have been reported to inhibit MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation, only

20 µM zafirlukast can induce G0/G1 cell cycle

arrest at 48 h post-exposure, according to a previous study

(7). Therefore, the effects of

both drugs on the expression of two proliferating markers, Ki-67

and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), were assessed.

Montelukast and zafirlukast at 20 µM decreased Ki-67 and PCNA at 6

h post-exposure (Fig. 1A and B).

Cells were treated with 20 µM drugs for 48 h and the expression

levels of proteins regulating cell cycle progression were

determined using western blotting. Cyclin D1 and CDK4 levels were

decreased in cells that were treated with zafirlukast (Fig. 1C and D), while both drugs had no

effect on cyclin E levels (Fig.

S1). Zafirlukast significantly decreased p21 expression,

whereas the increase of p21 by montelukast was not significant

(Fig. 1E). Increased p27

expression was found only in cells treated with zafirlukast

(Fig. 1F).

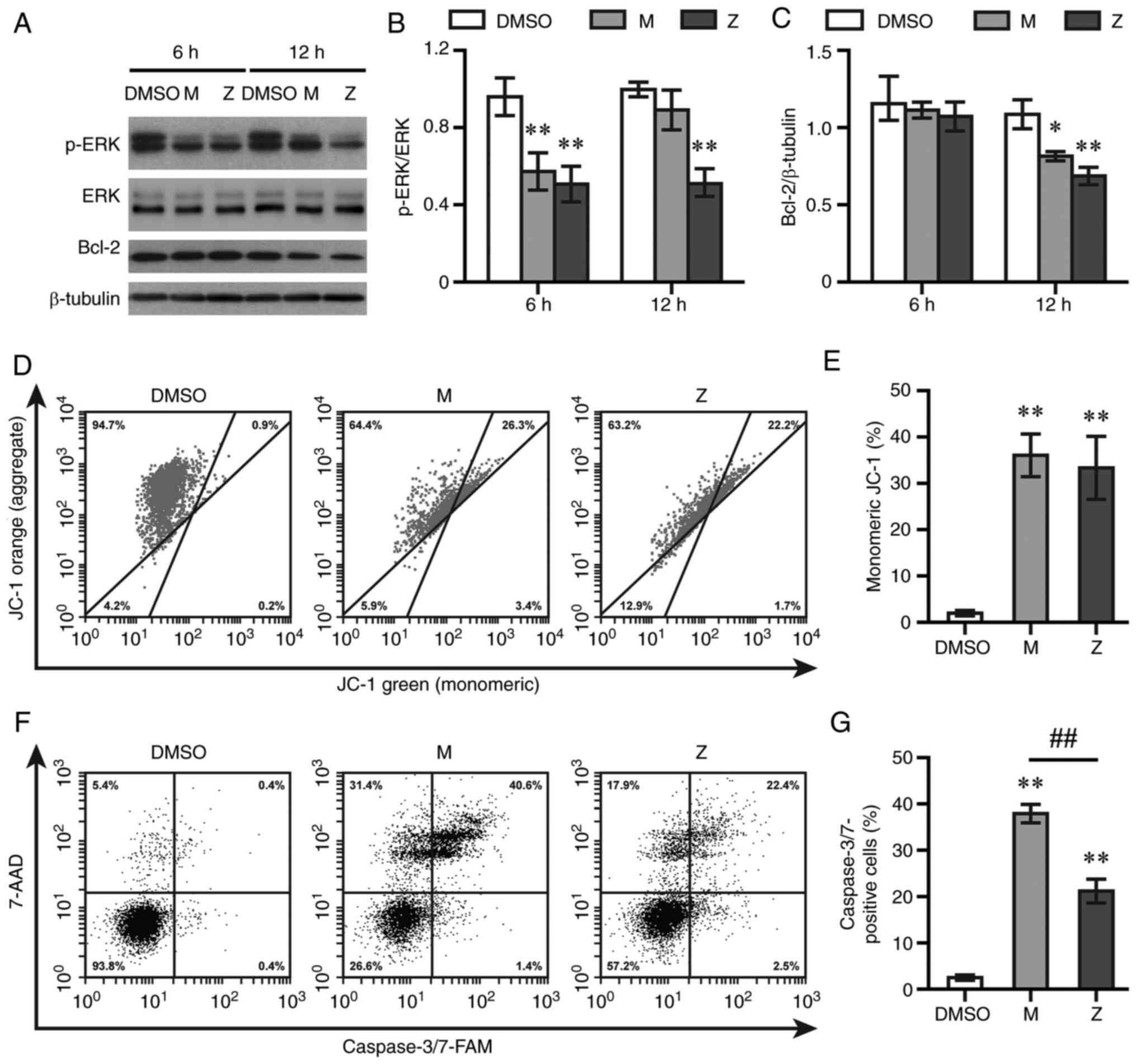

LTRAs activate the intrinsic apoptosis

pathway in MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells

Montelukast at ≥10 µM and zafirlukast at 20 µM were

previously reported to induce the apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 cells at

24 h post-exposure (7); therefore,

20 µM was used to assess cell death in the present study. The

expression levels of p-ERK1/2 and Bcl-2 were detected using western

blotting. Montelukast and zafirlukast decreased the expression

levels of p-ERK1/2 at 6 h (Fig. 2A and

B) and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 at 12 h post-exposure

(Fig. 2A and C). Both LTRAs did

not alter levels of ERK1/2 (Fig. 2A

and B). Next, cells were stained with JC-1 and 7-AAD to assess

mitochondrial membrane potential and cell death, respectively. Both

LTRAs increased the levels of cells with green fluorescent signal,

indicative of monomeric JC-1, at 12 h post-exposure (Fig. 2D and E). The levels of

7-AAD-positive cells after being exposed to montelukast and

zafirlukast were 48.98±7.22 and 31.61±2.04%, respectively, compared

with 3.97±0.50% in DMSO-treated cells at 12 h (data not shown).

Caspase 3/7 activity was also measured by flow cytometry. Both

drugs increased caspase 3/7 activity at 12 h post-treatment, with a

greater effect observed in montelukast-treated cells (Fig. 2F and G)

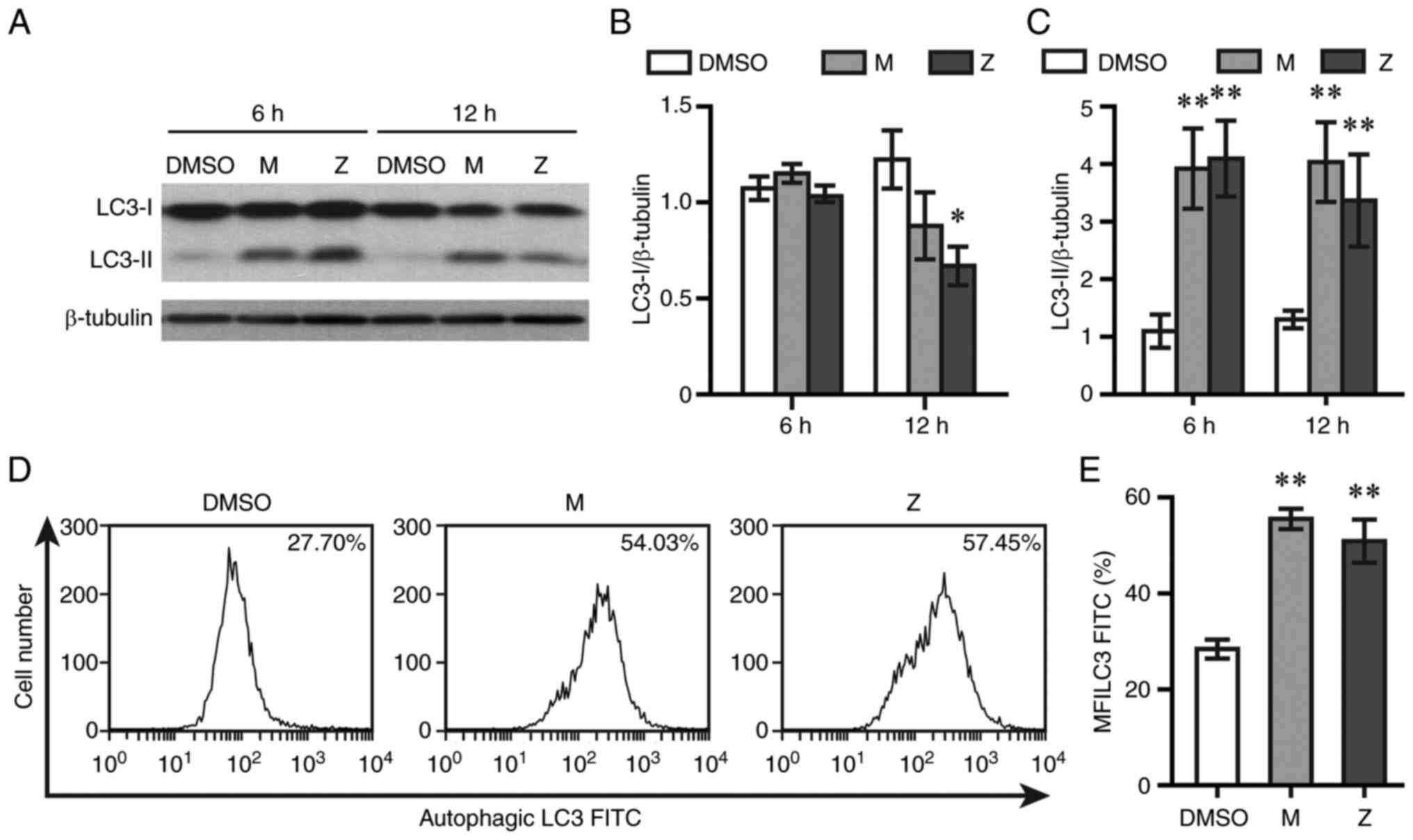

LTRAs trigger autophagy in MDA-MB-231

TNBC cells

To test whether autophagy was caused by LTRAs, LC3

levels were measured by western blotting and flow cytometry.

Montelukast and zafirlukast did not alter LC3-I levels at 6 h

post-exposure, while zafirlukast decreased LC3-I levels at 12 h

post-exposure (Fig. 3A and B).

Both drugs elevated LC3-II levels at 6 and 12 h post-treatment

(Fig. 3A and C). The expression of

lipidated LC3 sequestered into autophagosomes was determined by

using flow cytometry. Both drugs caused a rightward shift of

autophagic LC3 fluorescence intensity and increased the mean

fluorescent intensity of autophagic LC3 at 12 h post-exposure

(Fig. 3D and E).

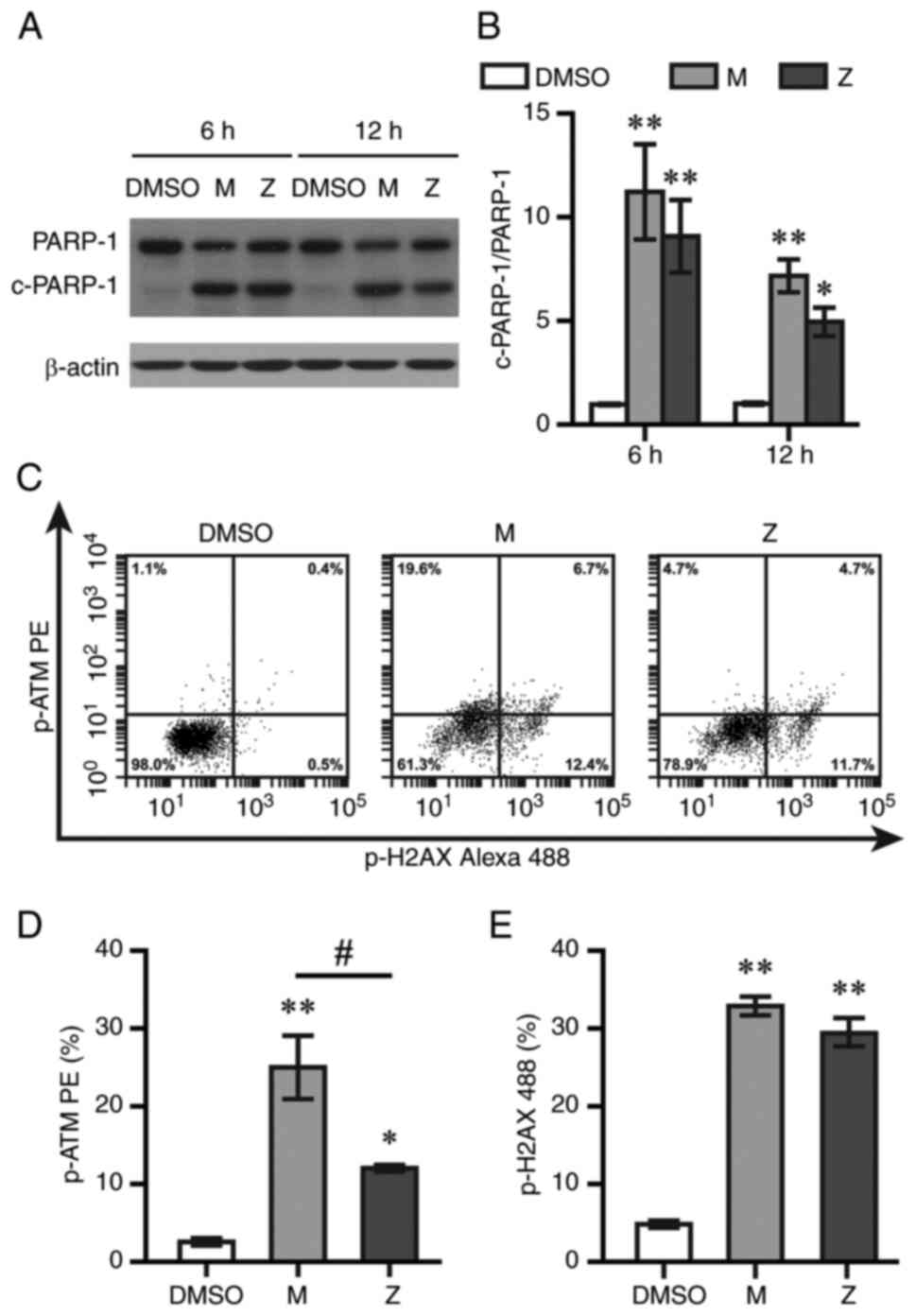

LTRAs induce DNA damage and

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and oxidative stress in MDA-MB-231 TNBC

cells

Apoptosis and autophagy are triggered in response to

DNA damage (13). The levels of

PARP-1, a key regulator of the DNA repair process, were measured by

western blotting in the present study. Montelukast and zafirlukast

increased levels of 89-kDa fragments of PARP-1 at 6 and 12 h after

treatment (Fig. 4A and B). Cells

with positive staining of p-ATM and p-H2AX, two DNA damage markers,

were counted by flow cytometry at 12 h post-exposure. Montelukast

and zafirlukast increased p-ATM and p-H2AX levels (Fig. 4C-E). Montelukast showed

significantly higher p-ATM levels than zafirlukast.

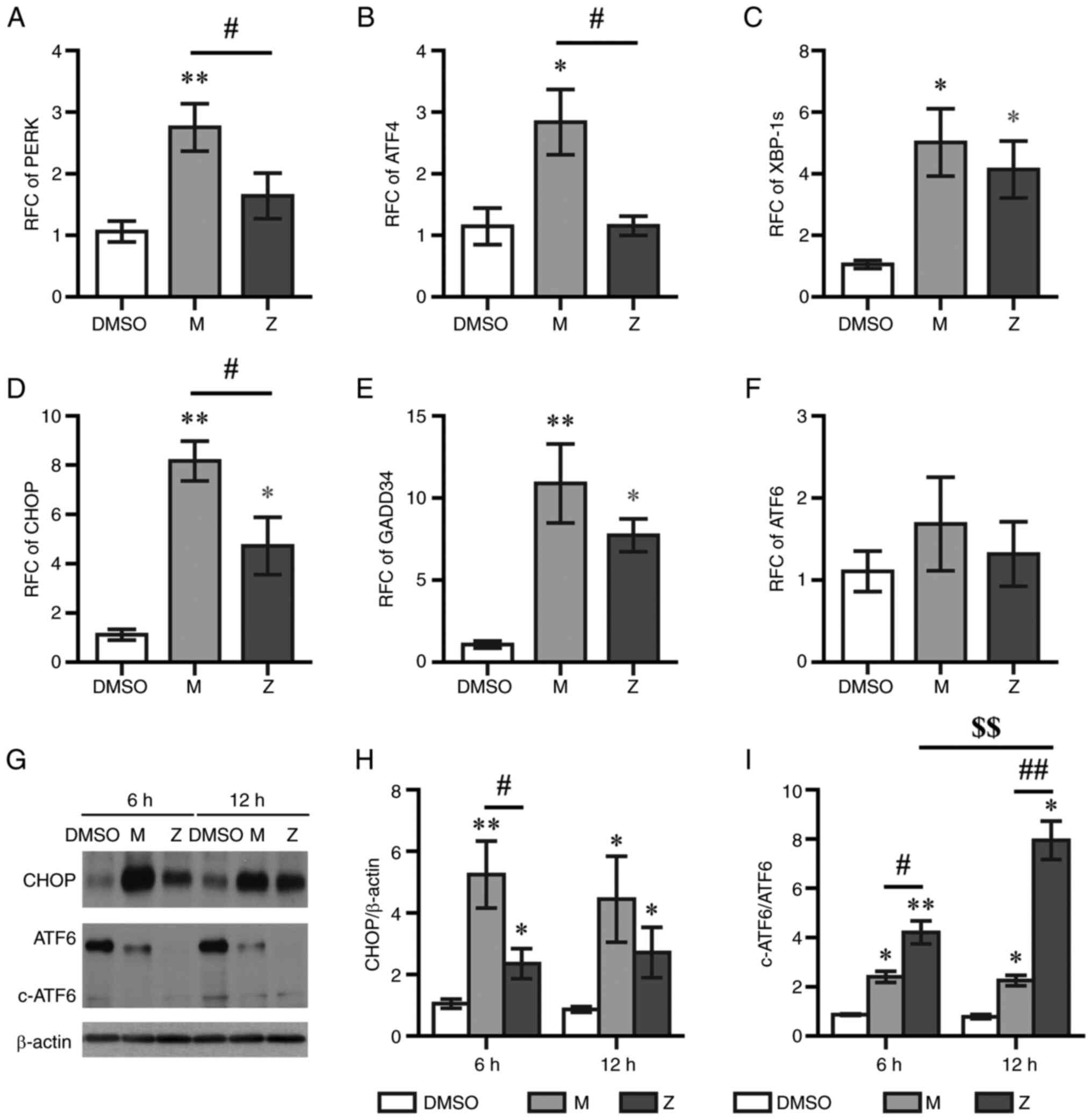

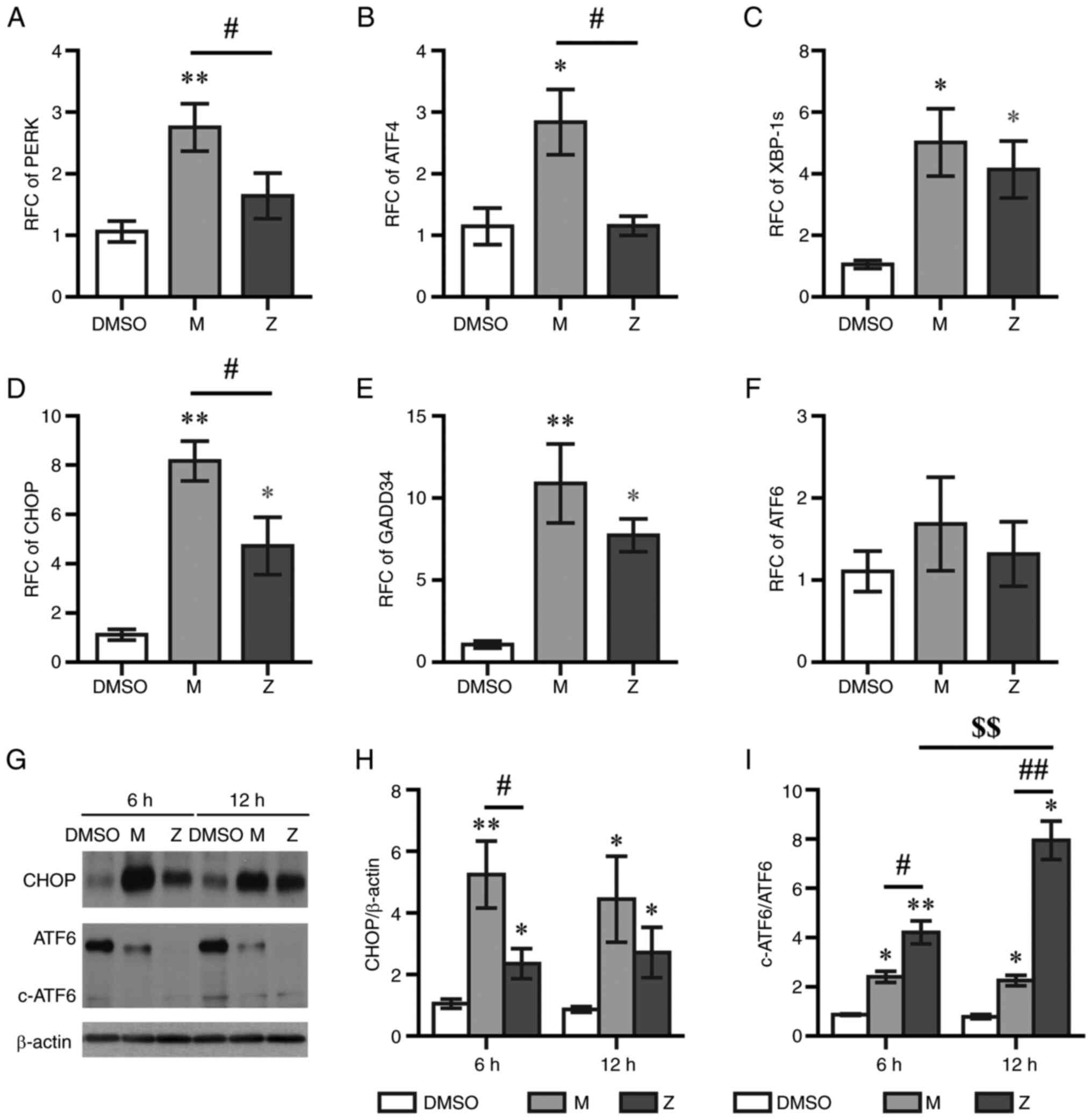

Activation of ER stress can lead to either autophagy

or apoptotic cell death (14,15).

In the present study, the expression of ER membrane-associated

sensors and signaling molecules was evaluated using RT-qPCR at 6 h

post-treatment. Montelukast, but not zafirlukast, upregulated the

expression levels of PERK and ATF4 (Fig. 5A and B). Both montelukast and

zafirlukast increased the mRNA expression levels of X-box binding

protein 1 splice variant (XBP-1s), CHOP and growth arrest and DNA

damage-inducible gene 34 (GADD34), but had no effect on ATF6 mRNA

levels (Fig. 5C-F). The protein

expression levels of CHOP in montelukast-treated cells were

significantly higher than those in zafirlukast-treated cells

(Fig. 5G and H). The activation of

ER stress triggers cleavage of ATF6 (16). Montelukast and zafirlukast

decreased the expression levels of total ATF6 protein (Fig. 5G), and the cleaved ATF6/ATF6 level

in zafirlukast-treated cells was greater than that in

montelukast-treated cells (Fig.

5I). The cleaved ATF6/ATF6 levels at 12 h post-zafirlukast

treatment were higher than those at 6 h.

| Figure 5.LTRAs upregulate endoplasmic

reticulum stress markers. Cells treated with M exhibited increased

mRNA expression levels of (A) PERK, (B) ATF4, (C) XBP-1s, (D) CHOP

and (E) GADD34. Z triggered only the expression of XBP-1s, CHOP and

GADD34. (F) Both LTRAs did not alter mRNA expression of ATF6. (G)

Western blotting showed the increase of CHOP and the decrease of

ATF6 expression. (H) M significantly increased the levels of CHOP

protein compared with Z. (I) Z significantly increased the levels

of c-ATF6/ATF6 compared with M. Data are expressed as the mean ±

SEM of 3-5 independent experiments. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs.

DMSO. #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs.

zafirlukast. $$P<0.01 vs. zafirlukast at 12 h. LTRA,

leukotriene receptor antagonist; M, montelukast; Z, zafirlukast;

ATF, activating transcription factor; XBP-1s, X-box binding protein

1 splice variant; GADD34, growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible

gene 34; c-, cleaved; RFC, relative fold change. |

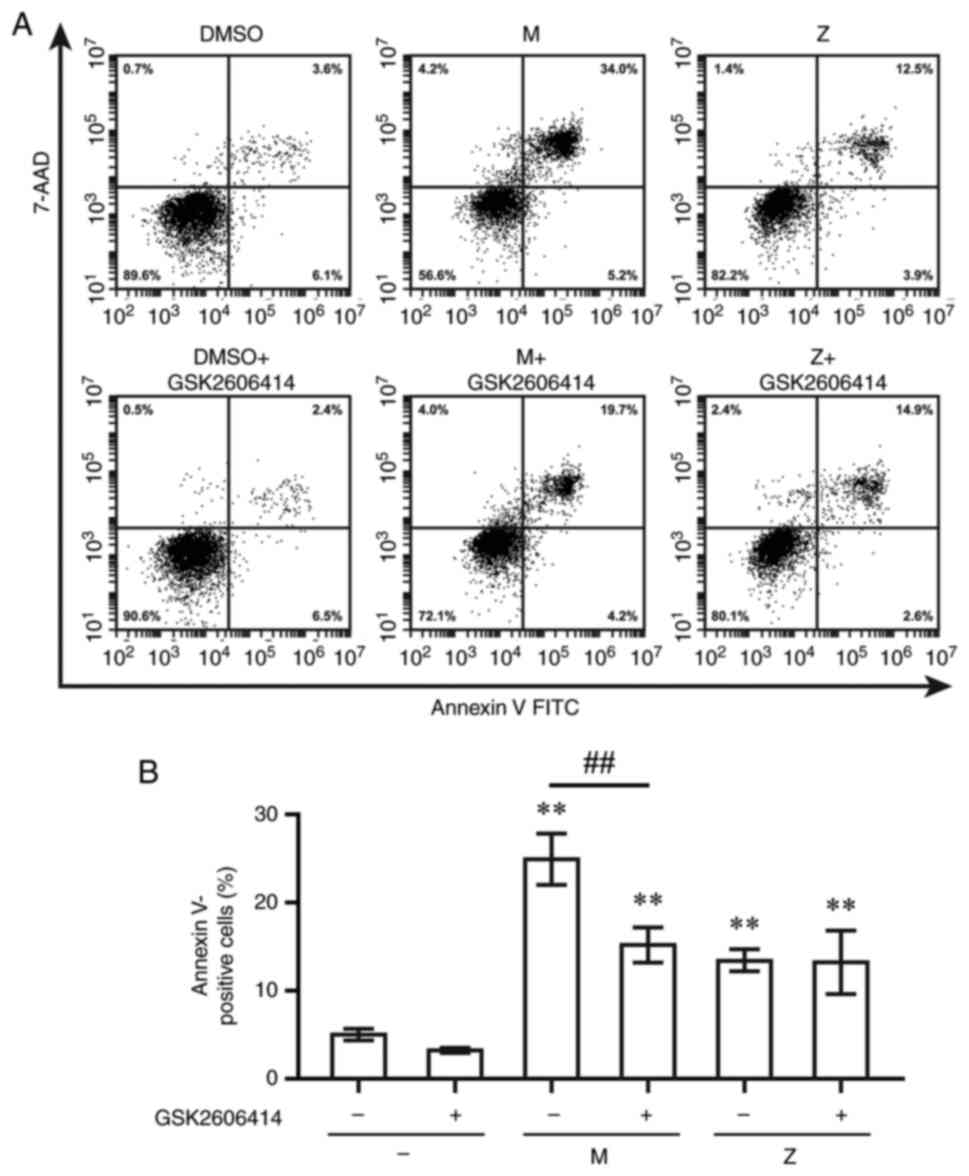

To determine the contribution of ER stress to

LTRA-induced apoptotic cell death, GSK2606414, a PERK inhibitor,

and siRNA targeting CHOP) were used. The percentage of cells with

Annexin V staining was measured at 12 h post-exposure to LTRAs.

Montelukast and zafirlukast increased the percentage of Annexin

V-positive cells; however, pre-treatment with GSK2606414 only

decreased the percentage of montelukast-induced Annexin V-positive

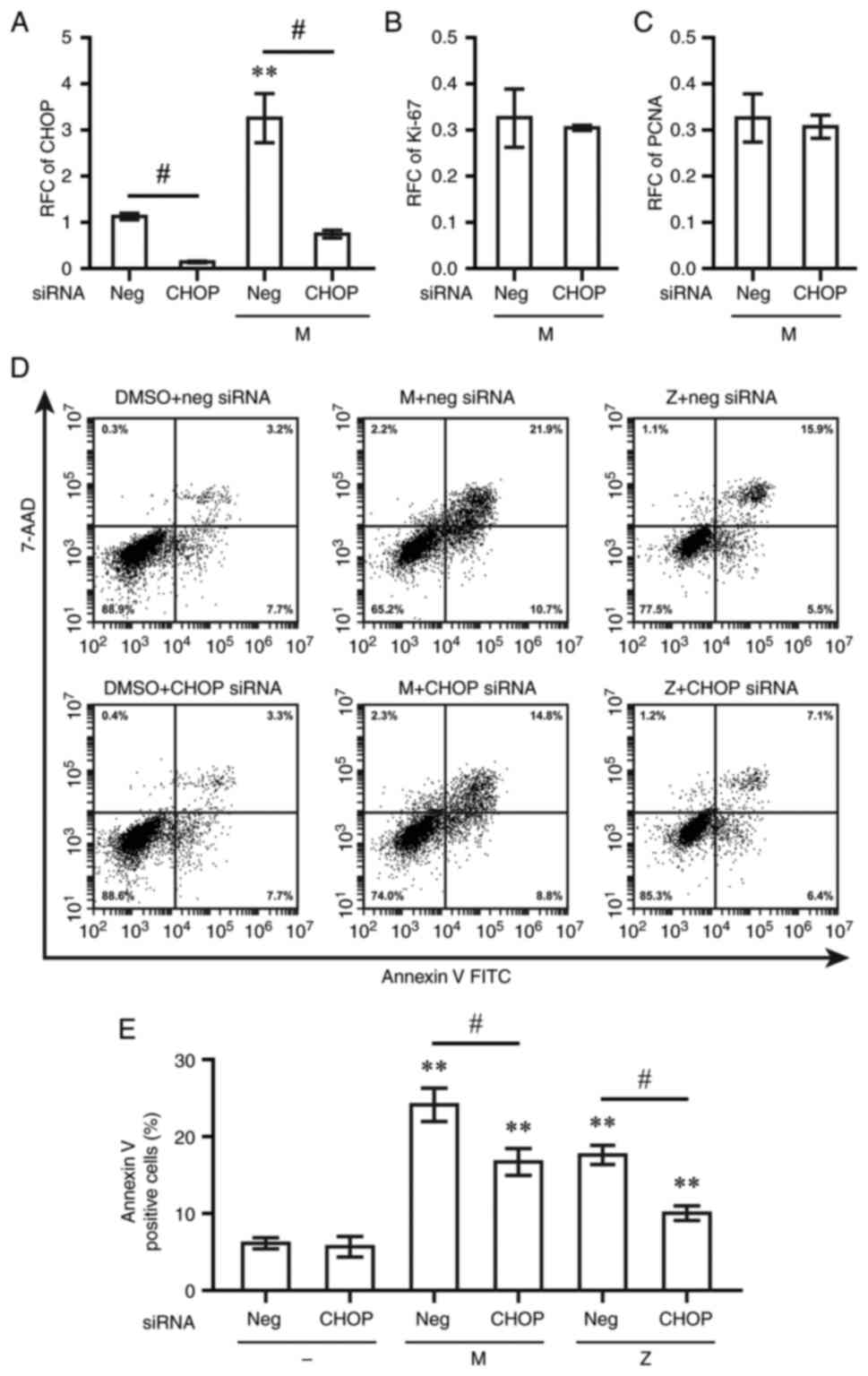

cells (Fig. 6). CHOP siRNA

decreased the CHOP mRNA levels to 14% compared to non-targeting

control siRNA (Fig. 7A). The mRNA

expression levels of CHOP triggered by montelukast were decreased

to 23% at 48 h post-transfection with CHOP siRNA compared with

cells with non-targeting control siRNA (Fig. 7A). By contrast, the downregulation

of Ki-67 and PCNA by montelukast was not reversed by CHOP siRNA

(Fig. 7B and C). Transfection with

CHOP siRNA resulted in lower levels of Annexin V-positive cells

than in the group transfected with the non-targeting control siRNA

following exposure to montelukast or zafirlukast (Fig. 7D and E).

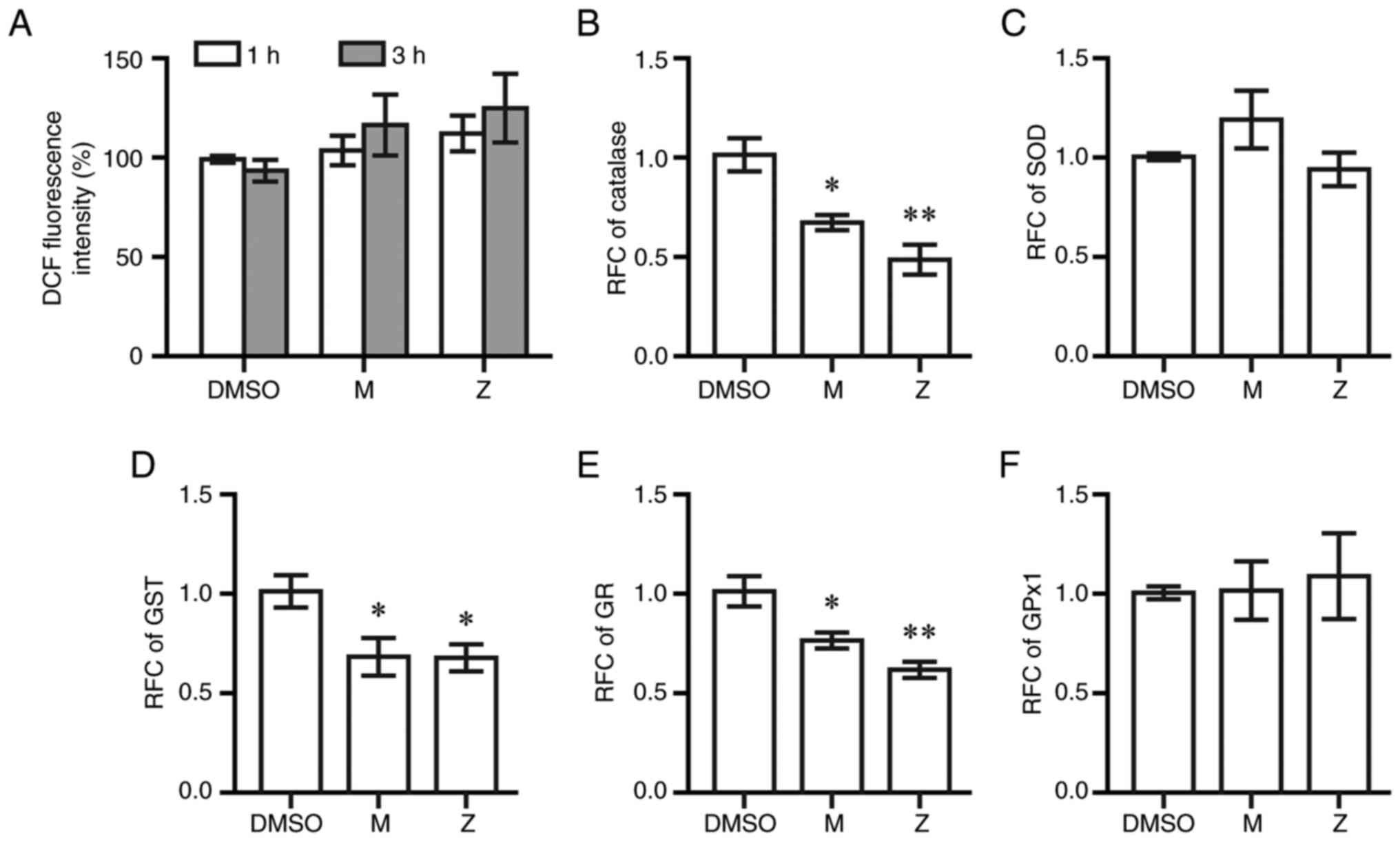

To examine whether LTRAs induced oxidative stress,

intracellular reactive oxygen species and the expression of

antioxidant enzymes were measured using DCF assays and RT-qPCR,

respectively. Montelukast and zafirlukast at 20 µM did not increase

DCF fluorescent intensity compared with DMSO at 1 and 3 h

post-treatment (Fig. 8A). Both

drugs decreased the expression of catalase, glutathione reductase

and glutathione S-transferase at 6 h post-exposure to montelukast

and zafirlukast; however, neither drug affected the expression of

superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase (Fig. 8B-F).

Discussion

Our previous findings showed that LTRAs, including

montelukast and zafirlukast, have the potential for BC treatment by

inhibiting cancer progression and inducing apoptosis in the absence

of hormonal stimuli (7). The

apoptotic effects of montelukast are more potent than zafirlukast

in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells. Zafirlukast induces cell cycle arrest at

G0/G1 phase, while montelukast treatment does

not induce cell cycle arrest at a specific phase and preferentially

induced cell death (7). The

present study demonstrated that montelukast and zafirlukast

differentially mediated CysLT1R signaling in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Montelukast and zafirlukast activates two ER stress sensors: ATF6

and IRE1; but only montelukast triggers PERK. The accumulation of

zafirlukast-treated cells in G0/G1 phase as

previously report (7) is mediated

by the upregulation of p27, and the decrease of CDK4 and cyclin D1.

Montelukast exhibited a greater effect than zafirlukast on the

upregulation of caspase 3/7, DNA damage and CHOP. Montelukast

activated all three pathways of ER stress: PERK, ATF6, and IRE1;

while zafirlukast only triggered the cleavage of ATF6 and XBP-1.

Both LTRAs also triggered autophagic response and decreased the

expression of antioxidant enzymes.

A key feature of cancer is the loss of cell cycle

regulation. Cell cycle arrest is the primary mechanism controlling

the proliferation of cancer cells and cell death (17). Ki-67 is a prognostic biomarker of

BC and was used in the recent American Joint Committee on Cancer

Staging System for BC (18,19).

In the present study, both LTRAs significantly decreased the

expression of two cell proliferating markers, Ki-67 and PCNA, in

MDA-MB-231 cells. The present results are consistent with a

previous study that showed inhibition of proliferation of non-tumor

and tumor-derived intestinal epithelial cells by LTRAs (20).

The upregulation of cyclin D1 promotes progression

of cells in the G1 phase while cyclin E is a key

regulator for cells to enter S phase. Cyclin D1 forms complexes

with CDK4 or CDK6 to trigger phosphorylation of retinoblastoma

protein (Rb), leading to the release of Rb from transcription

factor E2F. E2F then induces the synthesis of cyclin E and cyclin

A, which regulate the S phase (21). In the present study, zafirlukast

decreased the expression of cyclin D1 and CDK4 but showed no effect

on cyclin E expression. This suggested that the potential

G0/G1 cell cycle arrest was mediated by the

reduction of cyclin D1/CDK4 complexes. In addition to cyclin D1,

length of the G1 phase is regulated by the CDK inhibitor

p27. The inhibitory effect of p27 is key for entry into S phase

because p27 blocks the activity of cyclin E/CDK2, an initiator of

DNA synthesis. The inhibition of p27 expression decreases the

length of the G1 phase, and cyclin D1 inhibits the

activity of p27 (22). Therefore,

the G0/G1 cell cycle arrest induced by

zafirlukast in MDA-MB-231 cells in our previous study (7) may be mediated by the combination of

cyclin D1 downregulation and p27 upregulation. On the other hand,

decreased CDK4 expression without altered expression of cyclin D1,

cyclin E and p27 could explain the decrease of cell proliferation

without cell cycle arrest at specific phases induced by

montelukast. Our previous study showed that zafirlukast can

increase the levels of p53, p21 and p27 in U-87 MG glioblastoma

cells (10). In the present study,

zafirlukast decreased p21 expression. U-87 MG expresses wild-type

p53, while p53 in MDA-MB-231 is mutated (23). Although the most well-known

function of p21 is as a cell cycle inhibitor protein, there are

reports of p21 having oncogenic effects (24,25).

To date, three CDK 4/6 inhibitor agents

(palbociclib, ribociclib and abemaciclib) have been approved by the

Food and Drug Administration of United States and are available for

patients with BC. The major side effect of these CDK 4/6 inhibitors

is bone marrow suppression, resulting in anemia, neutropenia and

thrombocytopenia (26). LTRAs are

generally considered safe and well-tolerated drugs because of their

mild side effects (1,27). With the growing evidence of

anticancer effects and the inhibition of CDK4/6, LTRAs could be

repurposed as a chemopreventive agent or adjuvant in BC therapy. In

the present study, zafirlukast reduced the expression of both

cyclin D1 and CDK4; therefore, this drug may be a better candidate

than montelukast as a cyclin-CDK inhibitor. However, studies have

reported neuropsychiatric effects, such as depression,

hallucination and suicidal ideation, related to the use of

montelukast and zafirlukast (28,29).

The regulation of Bcl-2 by decreasing ERK1/2

activation following LTRA treatment has been reported in

glioblastoma (10), lung cancer

(9), leukemia (30) and colorectal cancer (31). In the present study, decreased

expression of p-ERK1/2 in the cells treated with LTRAs was observed

before a time-dependent reduction of Bcl-2 expression. Therefore,

LTRA-induced Bcl-2 downregulation in MDA-MB-231 cells is

potentially mediated by the inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

The activation of the ERK1/2 pathway triggers the degradation of

p27 (22). Therefore, the

upregulation of p27 observed in the present study could be mediated

by inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Bcl-2 expression maintains

the integrity of the mitochondrial outer membrane and prevents the

release of cytochrome c and caspase activation (32). In healthy cells, JC-1 dye enters

and forms aggregates with orange fluorescent signals. The decrease

of JC-1 aggregation by LTRAs indicated a loss of mitochondrial

membrane potential. Both LTRAs also increased levels of caspase

3/7-positive cells, indicating that LTRAs enhanced cell death via

the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in MDA-MB-231 cells.

The increase of caspase-3 activation by montelukast is consistent

with previous studies in colon cancer (33) and leukemia (30).

Caspase-mediated apoptotic cell death is

accomplished via cleavage of several key proteins, including

PARP-1. Cleavage of PARP-1 by caspases, a hallmark of apoptosis,

decreases DNA-binding capacity, which disrupts the routine repair

of DNA damage. Bcl-2 is an upstream regulator of PARP-1 activation

(34). Decreased Bcl-2 levels and

the upregulation of caspase 3/7 may lead to the increase of

cleaved-PARP-1 by LTRAs in MDA-MB-231 cells. This is consistent

with previous findings in chronic myeloid leukemia, which revealed

that montelukast triggers the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway by

increasing the activities of cytochrome c, caspase-3 and

cleavage of PARP-1 (20,30). The inhibition of PARP-1 can

increase ATM activation and promote H2AX phosphorylation (13). The elevation of cleaved-PARP-1,

p-ATM and p-H2AX by LTRAs in the present study indicated DNA damage

in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Autophagy serves a protective role in cancer cells

during chemotherapy, allowing cancer cells to alleviate cellular

stress, causing drug resistance. However, a number of cytotoxic

drugs promote cancer cell death via autophagy (35). The present study showed the

increased cleavage of LC3 (LC3-II), a marker of autophagy, and

decreased LC3-I in MDA-MB cells following LTRA treatment,

suggesting that the inhibition of leukotriene signaling could

induce autophagy. This observation aligns with the increase in

LC3-II induced by LTRAs in retinal pigment epithelial cells and a

rat model of hemorrhagic cystitis (36,37).

ER stress serves a dual role in cell survival and

death via apoptosis or autophagy in BC cells (14,15).

In the present study, the induction of key effectors involved in ER

stress and/or unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling by both

LTRAs was evidenced by an increase in ER stress markers, including

CHOP and XBP-1s, as well as the reduction of ATF6 due to

proteolytic cleavage. CHOP is a key link between the UPR and

pro-apoptotic activation (38).

The PERK/eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α/ATF4 pathway

plays an important role in the upregulation of CHOP in cancer cells

(39). Activation of IRE1 induces

the splicing of XBP-1 mRNA. XBP-1s and cleaved-ATF6 also trigger

CHOP expression (38). In the

present study, the higher levels of CHOP induced by montelukast

compared with zafirlukast are likely caused by the activation of

all three ER stress sensors: PERK, ATF6, and IRE1. In contrast,

zafirlukast did not upregulate the PERK/ATF4 pathway. GADD34 is one

of the downstream transcriptional targets of CHOP. This protein

acts as a part of negative feedback loop for the response essential

for cell survival by prolonged CHOP expression (40). In the present study, both LTRAs

triggered the expression of CHOP and GADD34.

CHOP is a key protein responsible for ER

stress-induced cell death by downregulating Bcl-2 (41). CHOP activates caspase-3 and PARP-1

(42), and induces the expression

of autophagy-related genes (38).

In BC, the increased expression of CHOP indicates ER stress-induced

autophagic cell death (14,15).

In the present study, the downregulation of CHOP by siRNA decreased

LTRA-induced apoptosis. Montelukast upregulated PERK and the

inhibition of PERK using its specific inhibitor reduced

montelukast-induced apoptosis. These results suggested that the

upregulation of ER stress contributed to LTRA-induced cell death.

The expression of CHOP has been shown to be associated with a lower

risk of recurrence and prolonged disease-free survival in patients

with BC (43). Therefore, the

increase of CHOP expression by LTRAs could be an important

mechanism for BC treatment. Upregulation of CHOP could lead to cell

cycle arrest. Although the downregulation of CHOP via siRNA did not

alter the decrease the expression levels of the proliferating

markers Ki-67 and PCNA in MDA-MB-231 cells, further studies on CHOP

knockdown and cell proliferation are of interest in other types of

cancers to investigate the role of ER stress in the inhibition of

cell proliferation.

Excessive oxidative stress leads to cell death.

Antioxidants and olaparib, a PARP-1 inhibitor, have been shown to

decrease zafirlukast-induced cell death in renal cell carcinoma

(44). In the present study,

montelukast and zafirlukast decreased the expression of antioxidant

enzymes including catalase, glutathione S-transferase and

glutathione reductase. Montelukast exhibits protective effects

against oxidative and ER stress in non-cancerous models (45–48).

Montelukast can ameliorate acetaminophen-induced liver injury and

methotrexate-induced kidney damage by decreasing oxidative stress

(45,46). Montelukast has also been shown to

decrease the expression of ER stress markers, including CHOP,

GADD34, ATF4 and IRE1a, in models of hepatotoxicity and diabetes

(47,48). These differential effects require

further studies in other cancerous cells.

The toxic concentrations of LTRAs required for

anticancer effects are greater than plasma concentrations used in

asthma treatment. Pharmacokinetic studies of a single dose of 10 mg

montelukast and 20 mg zafirlukast detected 0.63 µM of montelukast

and 0.58 µM of zafirlukast in human plasma (49,50).

Novel localized drug delivery using polymeric wafers, nanofibrous

scaffolds and hydrogels could increase drug concentrations at

cancer sites (51). It is also

possible to use nanocarriers to deliver LTRAs via intraductal

delivery (52). Graphine oxide

nanoparticles of montelukast have been shown to increase apoptosis

of inflammatory cells in a mouse asthma model (53). The volume of distribution of

montelukast and zafirlukast is ~10 and 70 l, respectively (49,54).

The greater the volume of distribution, the greater the tissue

accumulation. Zafirlukast, with a higher volume of distribution and

effects on both cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, could be a better

candidate than montelukast. The anti-inflammatory effects of LTRAs

for capsular contracture after breast augmentation have suggested a

potential role for these drugs in BC treatment (55,56).

Zafirlukast has been shown to prevent the metastasis of MDA-MB-231

cells to the bone and lung by blocking CysLT1R on platelets,

subsequently inhibiting platelet aggregation and adhesion on cancer

cells (57). In addition,

Montelukast may suppress the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in

MDA-MB-231 cells (58). The

knockdown of CysLT1R using siRNA or CRISPR may confirm the role of

this receptor in cell death pathways.

In conclusion, LTRAs effectively inhibited

MDA-MB-231 cells via multiple downstream signaling pathways,

including induction of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, autophagy, DNA

damage and ER stress. The use of one cell line is a limitation of

this study. The different effects on cell death and proliferation

induced by montelukast and zafirlukast should be further

investigated in other BC cells and animal models.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine

Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (grant no. RF_64093).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PV, NS and PW conceived the study. PV, TS and SP

analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. PV, KK and TS collected

data. PV and TS confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. PV

and TS edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Riccioni G, Bucciarelli T, Mancini B, Di

Ilio C and D'Orazio N: Antileukotriene drugs: clinical application,

effectiveness and safety. Curr Med Chem. 14:1966–1977. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tsai MJ, Chang WA, Chuang CH, Wu KL, Cheng

CH, Sheu CC, Hsu YL and Hung JY: Cysteinyl leukotriene pathway and

cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 23:1202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Magnusson C, Liu J, Ehrnstrom R, Manjer J,

Jirström K, Andersson T and Sjölander A: Cysteinyl leukotriene

receptor expression pattern affects migration of breast cancer

cells and survival of breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer.

129:9–22. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tsai MJ, Wu PH, Sheu CC, Hsu YL, Chang WA,

Hung JY, Yang CJ, Yang YH, Kuo PL and Huang MS: cysteinyl

leukotriene receptor antagonists decrease cancer risk in asthma

patients. Sci Rep. 6:239792016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jang HY, Kim IW and Oh JM: Cysteinyl

leukotriene receptor antagonists associated with a decreased

incidence of cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Front Oncol.

12:8588552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Maeda-Minami A, Hosokawa M, Ishikura Y,

Onoda A, Kawano Y, Negishi K, Shimada S, Ihara T, Sugamata M,

Takeda K and Mano Y: Relationship between leukotriene receptor

antagonists on cancer development in patients with bronchial

asthma: A retrospective analysis. Anticancer Res. 42:3717–3724.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Suknuntha K, Yubolphan R, Krueaprasertkul

K, Srihirun S, Sibmooh N and Vivithanaporn P: Leukotriene receptor

antagonists inhibit mitogenic activity in triple negative breast

cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 19:833–837. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Piromkraipak P, Sangpairoj K, Tirakotai W,

Chaithirayanon K, Unchern S, Supavilai P, Power C and Vivithanaporn

P: Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonists inhibit migration,

invasion, and expression of MMP-2/9 in human glioblastoma. Cell Mol

Neurobiol. 38:559–573. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tsai MJ, Chang WA, Tsai PH, Wu CY, Ho YW,

Yen MC, Lin YS, Kuo PL and Hsu YL: Montelukast induces

apoptosis-inducing factor-mediated cell death of lung cancer cells.

Int J Mol Sci. 18:13532017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Piromkraipak P, Parakaw T, Phuagkhaopong

S, Srihirun S, Chongthammakun S, Chaithirayanon K and Vivithanaporn

P: Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonists induce apoptosis and

inhibit proliferation of human glioblastoma cells by downregulating

B-cell lymphoma 2 and inducing cell cycle arrest. Can J Physiol

Pharmacol. 96:798–806. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Phuagkhaopong S, Ospondpant D, Kasemsuk T,

Sibmooh N, Soodvilai S, Power C and Vivithanaporn P:

Cadmium-induced IL-6 and IL-8 expression and release from

astrocytes are mediated by MAPK and NF-κB pathways.

Neurotoxicology. 60:82–91. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Schmittgen TD and Livak KJ: Analyzing

real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc.

3:1101–1108. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Aguilar-Quesada R, Munoz-Gamez JA,

Martin-Oliva D, Peralta A, Valenzuela MT, Matínez-Romero R,

Quiles-Pérez R, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G, Ruiz de

Almodóvar M and Oliver FJ: Interaction between ATM and PARP-1 in

response to DNA damage and sensitization of ATM deficient cells

through PARP inhibition. BMC Mol Biol. 8:292007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Clarke R, Cook KL, Hu R, Facey CO,

Tavassoly I, Schwartz JL, Baumann WT, Tyson JJ, Xuan J, Wang Y, et

al: Endoplasmic reticulum stress, the unfolded protein response,

autophagy, and the integrated regulation of breast cancer cell

fate. Cancer Res. 72:1321–1331. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sisinni L, Pietrafesa M, Lepore S,

Maddalena F, Condelli V, Esposito F and Landriscina M: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in breast cancer:

The balance between apoptosis and autophagy and its role in drug

resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 20:8572019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ye J, Rawson RB, Komuro R, Chen X, Davé

UP, Prywes R, Brown MS and Goldstein JL: ER stress induces cleavage

of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs.

Mol Cell. 6:1355–1364. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vermeulen K, Berneman ZN and Van

Bockstaele DR: Cell cycle and apoptosis. Cell Prolif. 36:165–175.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Finkelman BS, Zhang H, Hicks DG and Turner

BM: The Evolution of Ki-67 and Breast Carcinoma: Past observations,

present directions, and future considerations. Cancers (Basel).

15:8082023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhu H and Dogan BE: American Joint

Committee on Cancer's Staging System for Breast Cancer, Eighth

Edition: Summary for Clinicians. Eur J Breast Health. 17:234–238.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Paruchuri S, Mezhybovska M, Juhas M and

Sjolander A: Endogenous production of leukotriene D4 mediates

autocrine survival and proliferation via CysLT1 receptor signalling

in intestinal epithelial cells. Oncogene. 25:6660–6665. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR and

Berneman ZN: The cell cycle: A review of regulation, deregulation

and therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Prolif. 36:131–149. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stacey DW: Three observations that have

changed our understanding of cyclin D1 and p27 in cell cycle

control. Genes Cancer. 1:1189–1199. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hui L, Zheng Y, Yan Y, Bargonetti J and

Foster DA: Mutant p53 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is

stabilized by elevated phospholipase D activity and contributes to

survival signals generated by phospholipase D. Oncogene.

25:7305–7310. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Georgakilas AG, Martin OA and Bonner WM:

p21: A Two-Faced Genome Guardian. Trends Mol Med. 23:310–319. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Warfel NA and El-Deiry WS: p21WAF1 and

tumourigenesis: 20 years after. Curr Opin Oncol. 25:52–58. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Braal CL, Jongbloed EM, Wilting SM,

Mathijssen RHJ, Koolen SLW and Jager A: Inhibiting CDK4/6 in breast

cancer with palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib: similarities

and differences. Drugs. 81:317–331. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Matsuse H and Kohno S: Leukotriene

receptor antagonists pranlukast and montelukast for treating

asthma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 15:353–363. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Law SWY, Wong AYS, Anand S, Wong ICK and

Chan EW: Neuropsychiatric events associated with

leukotriene-modifying agents: A systematic review. Drug Saf.

41:253–265. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Marques CF, Marques MM and Justino GC:

Leukotrienes vs. Montelukast-Activity, Metabolism, and Toxicity

Hints for Repurposing. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 15:10392022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zovko A, Yektaei-Karin E, Salamon D,

Nilsson A, Wallvik J and Stenke L: Montelukast, a cysteinyl

leukotriene receptor antagonist, inhibits the growth of chronic

myeloid leukemia cells through apoptosis. Oncol Rep. 40:902–908.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Burke L, Butler CT, Murphy A, Moran B,

Gallagher WM, O'Sullivan J and Kennedy BN: Evaluation of cysteinyl

leukotriene signaling as a therapeutic target for colorectal

cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 4:1032016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sharpe JC, Arnoult D and Youle RJ: Control

of mitochondrial permeability by Bcl-2 family members. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1644:107–113. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Savari S, Liu M, Zhang Y, Sime W and

Sjolander A: CysLT(1)R antagonists inhibit tumor growth in a

xenograft model of colon cancer. PLoS One. 8:e734662013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Konopleva M, Zhao S, Xie Z, Segall H,

Younes A, Claxton DF, Estrov Z, Kornblau SM and Andreeff M:

Apoptosis. Molecules and mechanisms. Adv Exp Med Biol. 457:217–236.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li X, He S and Ma B: Autophagy and

autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Elrashidy RA and Hasan RA: Modulation of

autophagy and transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channels by

montelukast in a rat model of hemorrhagic cystitis. Life Sci.

278:1195072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Koller A, Bruckner D, Aigner L, Reitsamer

H and Trost A: Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 modulates

autophagic activity in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Sci Rep.

10:176592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hu H, Tian M, Ding C and Yu S: The C/EBP

Homologous Protein (CHOP) transcription factor functions in

endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and microbial

infection. Front Immunol. 9:30832018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Rozpedek W, Pytel D, Mucha B, Leszczynska

H, Diehl JA and Majsterek I: The Role of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP

signaling pathway in tumor progression during endoplasmic reticulum

stress. Curr Mol Med. 16:533–544. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Brush MH, Weiser DC and Shenolikar S:

Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein GADD34 targets

protein phosphatase 1 alpha to the endoplasmic reticulum and

promotes dephosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 2. Mol Cell Biol. 23:1292–1303. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Iurlaro R and Munoz-Pinedo C: Cell death

induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. FEBS J. 283:2640–2652.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hsu HY, Lin TY, Hu CH, Shu DTF and Lu MK:

Fucoidan upregulates TLR4/CHOP-mediated caspase-3 and PARP

activation to enhance cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity in human lung

cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 432:112–120. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zheng YZ, Cao ZG, Hu X and Shao ZM: The

endoplasmic reticulum stress markers GRP78 and CHOP predict

disease-free survival and responsiveness to chemotherapy in breast

cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 145:349–358. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wolf C, Smith S and van Wijk SJL:

Zafirlukast Induces VHL- and HIF-2alpha-dependent oxidative cell

death in 786-O clear cell renal carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Sci.

23:35672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Abdel-Raheem IT and Khedr NF:

Renoprotective effects of montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene

receptor antagonist, against methotrexate-induced kidney damage in

rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 387:341–353. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Pu S, Liu Q, Li Y, Li R, Wu T, Zhang Z,

Huang C, Yang X and He J: Montelukast prevents mice against

acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Front Pharmacol. 10:10702019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Fei Z, Zhang L, Wang L, Jiang H and Peng

A: Montelukast ameliorated pemetrexed-induced cytotoxicity in

hepatocytes by mitigating endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and

nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3)

activation. Bioengineered. 13:7894–7903. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Fleifel AM, Soubh AA, Abdallah DM, Ahmed

KA and El-Abhar HS: Preferential effect of Montelukast on

Dapagliflozin: Modulation of IRS-1/AKT/GLUT4 and ER stress response

elements improves insulin sensitivity in soleus muscle of a type-2

diabetic rat model. Life Sci. 307:1208652022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Cheng H, Leff JA, Amin R, Gertz BJ, De

Smet M, Noonan N, Rogers JD, Malbecq W, Meisner D and Somers G:

Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and safety of montelukast sodium

(MK-0476) in healthy males and females. Pharm Res. 13:445–448.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Dekhuijzen PN and Koopmans PP:

Pharmacokinetic profile of zafirlukast. Clin Pharmacokinet.

41:105–114. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Woodring RN, Gurysh EG, Bachelder EM and

Ainslie KM: Drug delivery systems for localized cancer combination

therapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 6:934–950. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Pandey M, Wen PX, Ning GM, Xing GJ, Wei

LM, Kumar D, Mayuren J, Candasamy M, Gorain B, Jain N, et al:

Intraductal delivery of nanocarriers for ductal carcinoma in situ

treatment: A strategy to enhance localized delivery. Nanomedicine

(Lond). 17:1871–1889. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Du C, Zhang Q, Wang L, Wang M, Li J and

Zhao Q: Effect of montelukast sodium and graphene oxide

nanomaterials on mouse asthma model. J Nanosci Nanotechnol.

21:1161–1168. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Accolate (zafirlukast). AstraZeneca

Pharmaceuticals LP; Wilmington, DE: 2009

|

|

55

|

Huang CK and Handel N: Effects of

Singulair (montelukast) treatment for capsular contracture. Aesthet

Surg J. 30:404–408. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Scuderi N, Mazzocchi M, Fioramonti P and

Bistoni G: The effects of zafirlukast on capsular contracture:

Preliminary report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 30:513–520. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Saier L, Ribeiro J, Daunizeau T, Houssin

A, Ichim G, Barette C, Bouazza L and Peyruchaud O: Blockade of

Platelet CysLT1R receptor with zafirlukast counteracts platelet

protumoral action and prevents breast cancer metastasis to bone and

lung. Int J Mol Sci. 23:122212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

El-Ashmawy NE, Khedr EG, Khedr NF and

El-Adawy SA: Suppression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

SIRT1/AKT signaling pathway in breast cancer by montelukast. Int

Immunopharmacol. 119:1101482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|