Introduction

Endometriosis is a prevalent gynecological disorder

associated with female infertility. It affects approximately 10% of

women of reproductive age and 25–50% of women experiencing

infertility. This disorder is characterized by the growth of

endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity, leading to symptoms

such as inflammation, dysmenorrhea, infertility, and dyspareunia.

These symptoms significantly impair the quality of life for women

and are often accompanied by psychological burdens (1,2).

However, effective long-term management of

endometriosis remains challenging despite the availability of

treatment options that include both surgical and non-surgical

approaches. Surgical approaches for endometriosis include minimally

invasive techniques such as laparoscopy, laser ablation, and

electrocoagulation for early-stage cases, whereas advanced surgical

procedures such as laparotomy, oophorectomy, and colorectal surgery

are required for deep infiltrating endometriosis. However, these

interventions carry risks, including recurrence due to incomplete

excision, ovarian dysfunction, voiding impairment, and tissue

damage (3–5). Several non-surgical treatment options

are currently available for managing endometriosis, with the most

common approaches being hormone therapy and pain management.

Low-dose oral contraceptives, which contain estrogen and

progesterone, are widely used and are shown to alleviate menstrual

pain, ameliorate infertility, reduce dyspareunia, and shrink

endometriotic lesions. However, these treatments are associated

with adverse effects, such as nausea, headache, and breakthrough

bleeding, and an increased risk of thrombosis with long-term use.

Additionally, they are contraindicated in women who wish to

conceive (3–6). Other treatment options include

aromatase inhibitors and progestin-based medications. Aromatase

inhibitors are drugs that inhibit the enzyme aromatase, which

converts androgens, the precursors of estrogen, into estrogen,

thereby suppressing estrogen production. Although aromatase

inhibitors reduce dysmenorrhea and shrink lesions, they are

expensive and decrease bone mineral density (7,8).

Progestin-based medications, which suppress estrogen activity and

inhibit endometrial proliferation, also cause adverse effects such

as breakthrough bleeding, and their efficacy is typically lower

than that of low-dose oral contraceptives (9). Other treatment options, such as

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen), carry

cardiovascular risks with long-term use, whereas neuromodulators

and antidepressants (such as gabapentinoids) used for chronic pain

management may lead to dependency (10,11).

Hence, effective and safe treatment options must be explored for

endometriosis.

Recently, considerable progress has been made in

understanding the pathophysiology of endometriosis; genetic and

immunological factors involved in the ectopic occurrence,

proliferation, and invasion of endometrial tissue are gradually

being elucidated. For instance, interleukin (IL)-8 and endothelin,

secreted by ectopic endometrial tissue, promote inflammatory

responses mediated by immune cells and contribute to symptoms such

as pain and complications such as adhesions (12–14).

These advances in understanding have spurred efforts to develop

alternative treatment methods. Subsequently, natural compounds are

being researched as effective therapeutic options with minimal side

effects for endometriosis, and the potential of resveratrol, an

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compound, for the treatment of

endometriosis has been demonstrated (15–17).

However, the therapeutic utility of resveratrol is limited by its

low absorption rates. In contrast, ε-viniferin, a dimer of

resveratrol, exhibits increased lipophilicity, which enhances

membrane permeability and absorption in the gastrointestinal tract

and liver (Fig. 1).

Pharmacokinetic studies have also demonstrated high bioaccumulation

of ε-viniferin in white adipose tissue, suggesting that these

tissues may serve as a reservoir for its native form, enabling slow

release and prolonged systemic presence (18–20).

ε-viniferin is the main functional compound in wild

grapes (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata), with antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor effects (21–24).

It also has neuroprotective effects, which may be beneficial in the

treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and

Parkinson's diseases (25), and

preventive effects against obesity-related morbidities, such as

type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and fatty liver

(26). ε-viniferin inhibits

TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and

invasion in lung cancer cells by downregulating vimentin (27). Elevated levels of TGF-β1 have also

been implicated in the development of endometriosis by promoting

cell migration and invasiveness (28). Given these shared mechanistic

pathways, we hypothesized that ε-viniferin exerts beneficial

effects in endometriosis by inhibiting key processes involved in

the disease. However, its potential effects on endometrial cells

remain unclear.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the

anti-inflammatory effects of ε-viniferin and wild-grape extract,

along with their inhibitory effects on the migration and invasion

of human endometrial stromal cells (HESCs). We believe that our

findings would contribute to the development of ε-viniferin as a

potential therapeutic option for the effective management of

endometriosis.

Materials and methods

Materials

Wild-grape extract (cat. no. 30811033) and

ε-viniferin (cat. no. NS3013) were purchased from Maruzen

Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. and Nagara Science Co., Ltd.,

respectively.

Cell culture

Mouse macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7

(RRID:CVCL_0493, cat. no. TIB-71; American Type Culture Collection)

and human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 (RRID:CVCL_0006, cat.

no. RCB3686; Riken Bioresource Center) were cultured in RPMI1640

medium (cat. no. 189-02025; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical

Corporation) supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum

(cat. no. F7524, non-USA origin; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and 1%

(v/v) penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2. THP-1 cells (1.5×104 cells/well) were

seeded into 96-well plates and differentiated into macrophage-like

cells using 0.1 µg/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; cat.

no. P1585; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 72 h.

To investigate the potential application of

ε-viniferin for its anti-endometriotic effects, we used HESCs,

which are derived from ectopic endometrial tissues associated with

endometriosis and drive the abnormal migration and invasion of

endometrial tissue.

Immortalized HESCs (cat. no. T0533; Applied

Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada, http://www.abmgood.com/immortalized-human-endometrial-stromal-cells-hesc.html)

were cultured in Prigrow IV medium (cat. no. TM004; Applied

Biological Materials, Inc.) supplemented with 2 mM L-Glutamine

(cat. no. G275; Applied Biological Materials, Inc.), 10%

charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (cat. no. 12676-029; Gibco),

and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified

incubator containing 5% CO2.

Cell viability

RAW264.7 cells (3×104 cells/well) were

seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 1 h. Differentiated

THP-1 cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and

fresh medium before overnight incubation. HESCs (1.5×104

cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated

overnight. The test chemicals, namely, wild-grape extract at 0.03,

0.1, and 0.3 mg/ml and ε-viniferin at 3, 10, and 30 µg/ml, were

added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h at 37°C.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as the control. MTT reagent

(working concentration: 0.5 mg/ml; cat. no. 10009591; Cayman

Chemical) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The

supernatant was replaced with 100 µl of DMSO to dissolve the

formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a

microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Nitric oxide (NO) production

RAW264.7 cells (3×104 cells/well) were

seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 1 h. Test chemicals

were added to each well and incubated for an additional hour,

followed by exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/ml; cat.

no. L5293; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 24 h. The supernatant was

collected, and 50 µl aliquots were mixed with an equal volume of

Griess reagent in a 96-well plate. Absorbance was measured at 570

nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Measurement of IL-6 production

RAW264.7 cells (3×104 cells/well) were seeded into

96-well plates and incubated for 1 h

Differentiated THP-1 cells were washed with PBS and

fresh medium before overnight incubation. The test chemicals,

namely, wild-grape extract at 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 mg/ml and

ε-viniferin at 10, 20, and 30 µg/ml, were added to each well and

incubated for 1 h, followed by exposure to LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24

h. IL-6 concentration in the supernatants were measured using Mouse

IL-6 ELISA Kit (cat. no. M6000B; R&D Systems) for RAW264.7

cells and Human IL-6 ELISA Kit (cat. no. D6050; R&D Systems)

for THP-1 cells, following the manufacturer's protocol. Plates were

washed four times, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IL-6 was

added, followed by a 2 h incubation at 23–25°C. Substrate solutions

of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) and hydrogen peroxide were added to

each well after washing four times, and plates were incubated for

20 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was quenched

using diluted hydrochloric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm

using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

(ROS) production

RAW264.7 cells (3×104 cells/well) were

seeded into 96-well plates and incubated overnight. Test chemicals

at various concentrations were added, and the cells were incubated

for 1 h, followed by exposure to LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 h at 37°C.

ROS production was determined using DCFH-DA (20 µM; cat. no. 35845;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), an oxidant-sensitive fluorescent probe.

The medium was removed from each well, and the cells were washed

twice with Ca2+, Mg2+-free PBS (PBS-) and

incubated with DCFH-DA for 30 min. After removing the supernatant

and washing twice with PBS-, 200 µl PBS- was added to each well.

Fluorescence was measured with excitation and emission wavelengths

of 485 nm and 535 nm, respectively, using a fluorescence plate

reader (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices).

Measurement of DPPH radical scavenging

ratio

The scavenging effect was assessed using the DPPH

Antioxidant Assay Kit (cat. no. D678; Dojindo). Briefly, 20 µl of

the sample solution was added to each well of a 96-well microplate,

followed by 80 µl of assay buffer and 100 µl of

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) working solution. Wild-grape

extract solutions (at 0.1, 0.3, and 1 mg/ml) and ε-viniferin (at 3,

10, and 30 µg/ml) were used as samples. Trolox at 80 µg/ml was used

as a positive control. The plate was incubated for 30 min at room

temperature in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a

microplate reader (SpectraMax M5).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), and reverse transcription-PCR

(RT-PCR)

RAW264.7 cells (1×106 cells/well) were

seeded into 60 mm dishes and incubated for 24 h. Test chemicals

were added to each dish and incubated for 1 h, followed by LPS

treatment (100 ng/ml) for 4 h at 37°C. RNA was extracted using

TRIzol reagent (1 ml; cat. no. 15596018; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity

cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (cat. no. 4368814; Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Vilnius, Lithuania) at

25°C for 10 min, 37°C for 120 min, and 85°C for 5 min. For RT-qPCR,

cDNA was amplified in triplicate using KOD FX Neo PCR Buffer (14

µl) and dNTPs (cat. no. KFX-201; Toyobo Co., Ltd.). Target DNA

sequences for each primer pair were amplified in triplicate under

the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 sec,

followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 10 sec, and 70°C

for 20 sec, using the QuantStudio 3 system (Applied Biosystems,

Singapore). mGapdh and ACTB were used as internal

controls. Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (29).

For RT-PCR, PCR products were separated on a 2%

agarose gel, and the band intensities were analyzed using ImageJ

software (ImageJ 1.53e with Java 1.8.0_172; National Institutes of

Health). The following primer pairs were used: mouse iNOS,

5′- GTCTTGCAAGCTGATGGTCA-3′ (forward) and

5′-ACCACTCGTACTTGGGATGC-3′ (reverse); mouse Il1β,

5′-CGTGGACCTTCCAGGATGAG-3′ (forward) and

5′-GGAGCCTGTAGTGCAGTTGTC-3′ (reverse); mouse Il6,

5′-ACCACGGCCTTCCCTACTTC-3′ (forward) and

5′-CACAACTCTTTTCTCATTTCCACG-3′ (reverse); human IL6,

5′-AGACAGCCACTCACCTCTTCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-

TTCTGCCAGTGCCTCTTTGCTG-3′ (reverse); mouse Gapdh,

5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GATGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′

(reverse); and human ACTB, 5′-CTTCTACAATGAGCTGCGTG-3′

(forward) and 5′-TCATGAGGTAGTCAGTCAGG-3′ (reverse).

Wound healing assay

HESCs (1×105 cells/well) were seeded into

24-well plates and cultured overnight until confluence. A uniform

scratch was created across the center of the well using a 200 µl

pipette tip. Floating cells and the growth medium were removed, and

serum-free medium containing the test chemicals was added to each

well. Cells were incubated for an additional 8 h, and their

movement into the scratched area was recorded every 2 h using a

phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS100).

Matrigel invasion chamber assay

HESCs (5×104 cells/well) suspended in 500

µl serum-free Prigrow IV medium containing test chemicals were

seeded into commercial Matrigel-coated chambers (BD Matrigel

Basement Membrane Matrix; cat. no. 354480; Corning). The lower

chambers were filled with 750 µl of Prigrow IV medium with 10% FBS

and were incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Thereafter, non-invading cells

were removed by wiping the upper surface of the membrane with a

cotton swab, and invading cells on the lower surface of the

membrane were stained with Diff-Quick (cat. no. 16920; Sysmex)

according to the manufacturer's instruction and counted under a

phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS100).

PCR array

Total RNA was extracted from HESCs using the RNeasy

Mini Kit (cat. no. 74106; Qiagen, Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia,

Germany), treated with ε-viniferin for 8 h, and reverse transcribed

using the RT2 First Strand Kit (cat. no. 330401; Qiagen,

Germantown, MD, USA). The cDNA was applied to the Human Tumor

Metastasis PCR Array (cat. no. 330231; Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA)

using RT2 SYBR-Green ROX qPCR Mastermix (cat. no.

330520; Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Data were analyzed using the

2−ΔΔCq method (29).

Measurement of NF-κB activity

RAW264.7 cells (3×106 cells/well) were

seeded into 6-well plates and incubated for 1 h. Test chemicals at

various concentrations were added to each well and incubated for 1

h, followed by LPS treatment (100 ng/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. Nuclear

extracts were prepared using the Nuclear Extract Kit (cat. no.

40010; Active Motif) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

NF-κB binding activity was measured using nuclear extract (5 µg)

with the TransAM NF-κB p65 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (cat. no.

40096; Active Motif).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean±standard deviation

(SD). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism

version 10.0 (Dotmatics). Differences between the two groups were

analyzed using the Student's t-test. One-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test was used for

comparisons among more than two groups. Statistical significance

was set at P<0.05.

Results

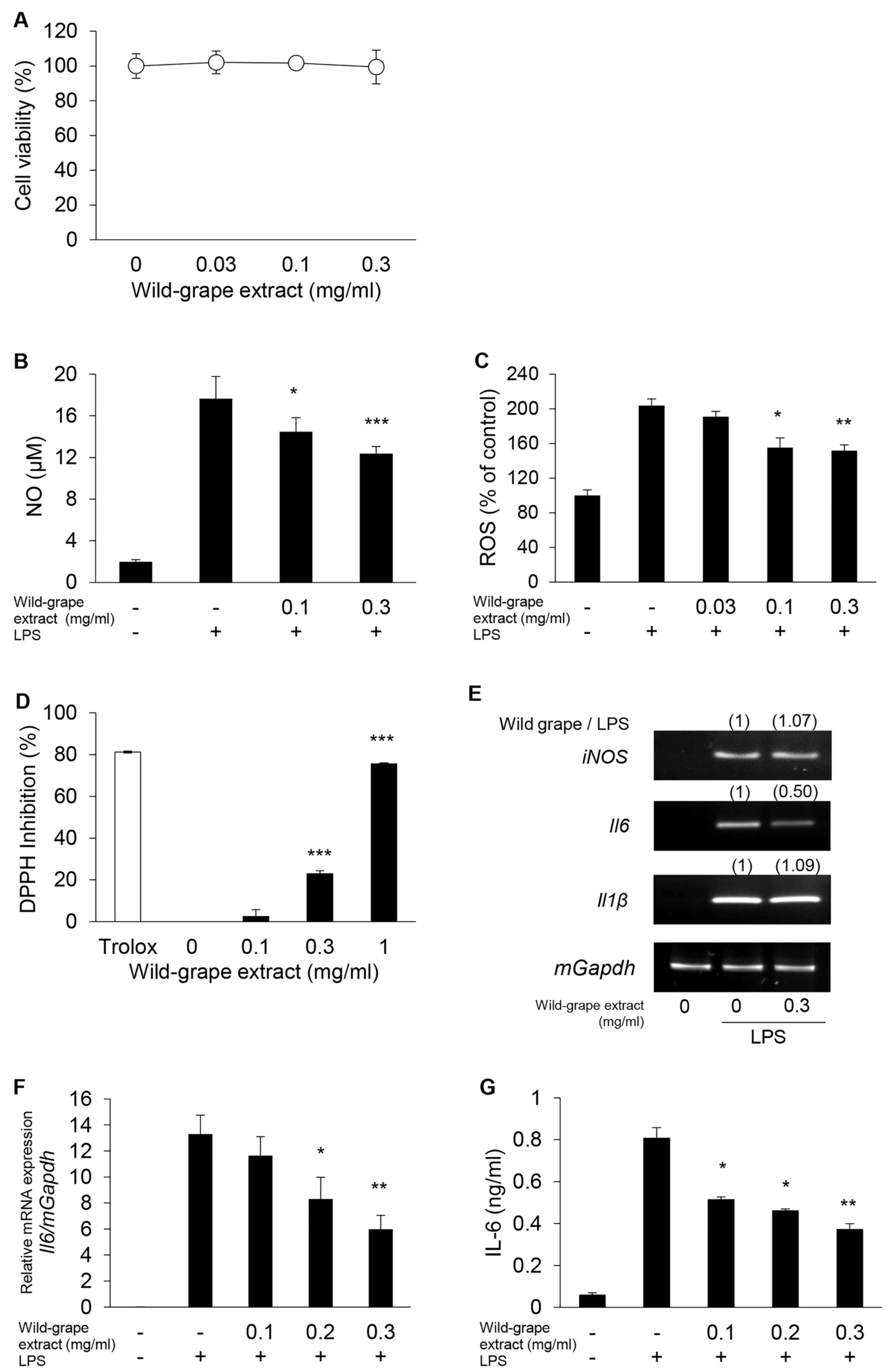

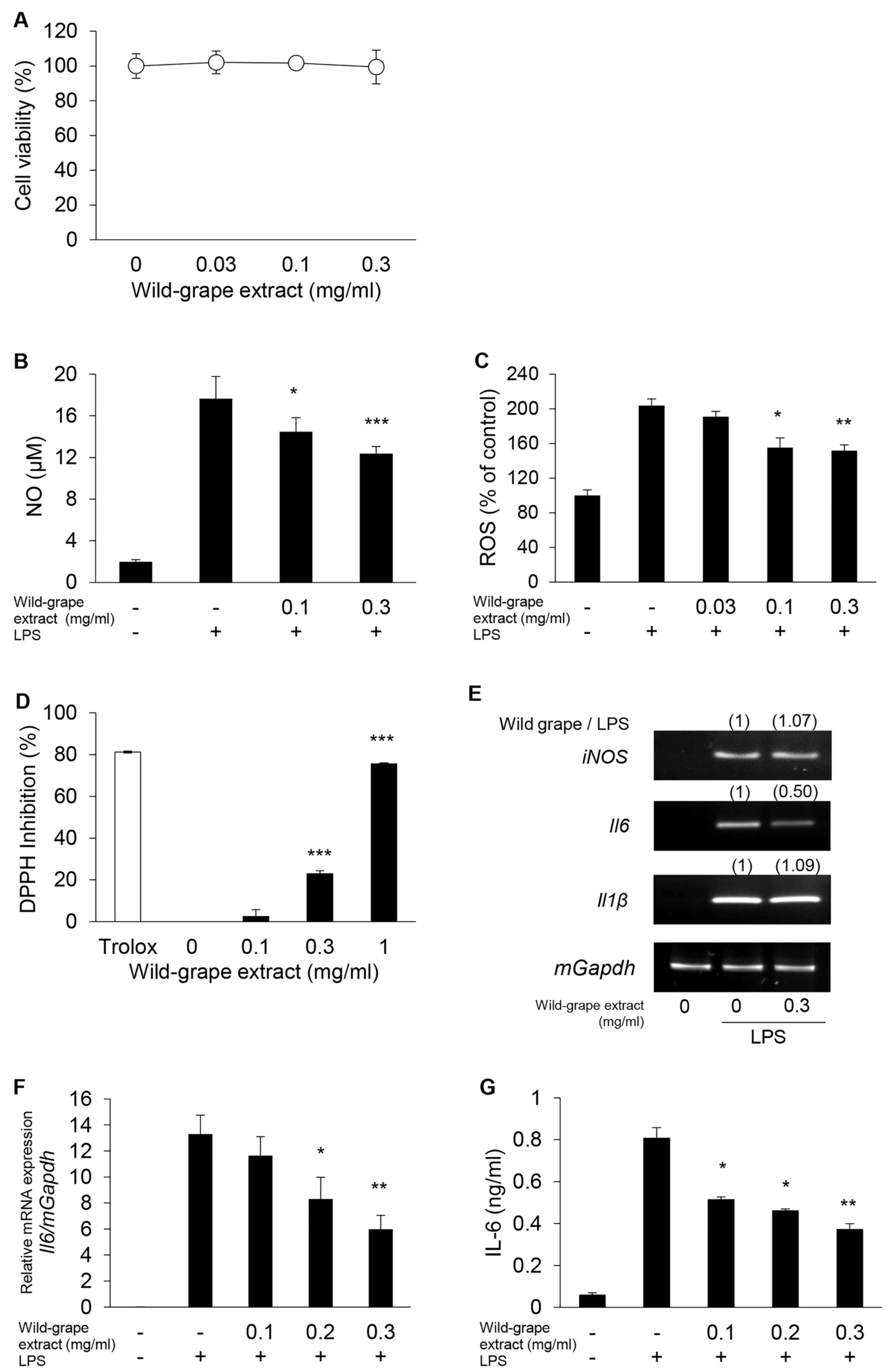

Wild-grape extract suppresses

inflammatory regulators and ROS in RAW264.7 cells

The anti-inflammatory effects of wild-grape extract

were evaluated in RAW264.7 cells. Wild-grape extract was not

cytotoxic to RAW264.7 cells after 24 h of treatment at

concentrations below 0.3 mg/ml (Fig.

2A). The extract suppressed LPS-induced NO and ROS production

in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 2B and C)

and exhibited significant dose-dependent antioxidant activity in

the DPPH assay (Fig. 2D). As

inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is responsible for NO

production, we explored the effect of wild-grape extract on

LPS-induced iNOS and the expression of downstream inflammatory

factors, IL-6 and IL-1β. Although wild-grape extract did not

inhibit LPS-induced iNOS or IL-1β expression, it significantly

inhibited LPS-induced IL-6 expression (Fig. 2E). We further validated this

inhibition using RT-qPCR and ELISA in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 2F and G). These findings indicate

that wild-grape extract suppresses ROS-activated IL-6 inflammatory

reactions in RAW264.7 cells.

| Figure 2.Inhibition of inflammatory regulators

and ROS production by wild-grape extract in RAW264.7 cells.

(A) Effect of wild-grape extract on cell viability after 24 h of

exposure, assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5

diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. (B) Inhibition of

LPS-induced NO production. (C) Reduction of LPS-induced ROS

production, measured based on fluorescent intensity. (D) In

vitro antioxidant activity determined using the DPPH

radical-scavenging assay. (E) Effect on LPS-induced expression of

iNOS, IL-6 and IL-1β. (F) Inhibition of LPS-induced IL-6

expression. (G) Inhibition of LPS-induced IL-6 secretion. RAW264.7

cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence

of wild-grape extract. n=3. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

vs. control without the extract. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NO,

nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DPPH,

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; iNOS, inducible NOS; IL,

interleukin; mGapdh, mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase. |

ε-viniferin reduces inflammation

through ROS suppression and NF-κB inhibition in RAW264.7 cells

We investigated the anti-inflammatory action of

ε-viniferin in RAW264.7 cells. ε-viniferin was not cytotoxic to

RAW264.7 cells after 24 h of treatment at concentrations below 10

µg/ml (Fig. 3A). ε-viniferin,

similar to wild-grape extracts, showed significant dose-dependent

antioxidant activity in the DPPH assay (Fig. 3B). Although ε-viniferin did not

suppress LPS-induced NO production (Fig. 3C), it suppressed LPS-induced ROS

production at non-toxic concentrations (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the

anti-inflammatory effects of ε-viniferin partially stem from the

suppression of ROS production.

| Figure 3.Inhibition of inflammatory regulator

production and NF-κB activity by ε-viniferin in RAW264.7 cells. (A)

Effect of ε-viniferin on cell viability after 24 h of exposure. (B)

In vitro antioxidant activity determined using the DPPH

radical-scavenging assay. (C) Inhibition of LPS-induced NO

production. (D) Inhibition of LPS-induced ROS production, measured

based on fluorescent intensity. (E) Effect of ε-viniferin on cell

viability after 4 h of exposure. (F) Inhibition of LPS-induced IL-6

expression. (G) Inhibition of LPS-induced IL-6 secretion. (H)

Inhibition of LPS-induced NF-κB activity. RAW264.7 cells were

stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of

ε-viniferin. N=3. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs.

control without ε-viniferin and LPS. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NO,

nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; IL, interleukin; DPPH,

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; mGapdh, mouse

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. |

We then explored the effects of ε-viniferin on IL-6

production in RAW264.7 cells because wild-grape extract inhibited

LPS-induced IL-6 production and IL-6 production is an early

response in LPS-induced inflammatory reaction. Within 4 h of

exposure, ε-viniferin was not cytotoxic to RAW264.7 cells at a

concentration of 30 µg/ml (Fig.

3E). However, it significantly inhibited LPS-induced IL-6

production both at gene and protein levels (Fig 3F and G).

We also tested the effect of ε-viniferin on NF-κB

activity, as this transcription factor is present upstream of IL-6,

and NF-κB activation was significantly suppressed by ε-viniferin in

a concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

3H). These results suggest that the NF-κB-mediated IL-6

signaling pathway is central to the anti-inflammatory effects of

ε-viniferin in RAW264.7 cells.

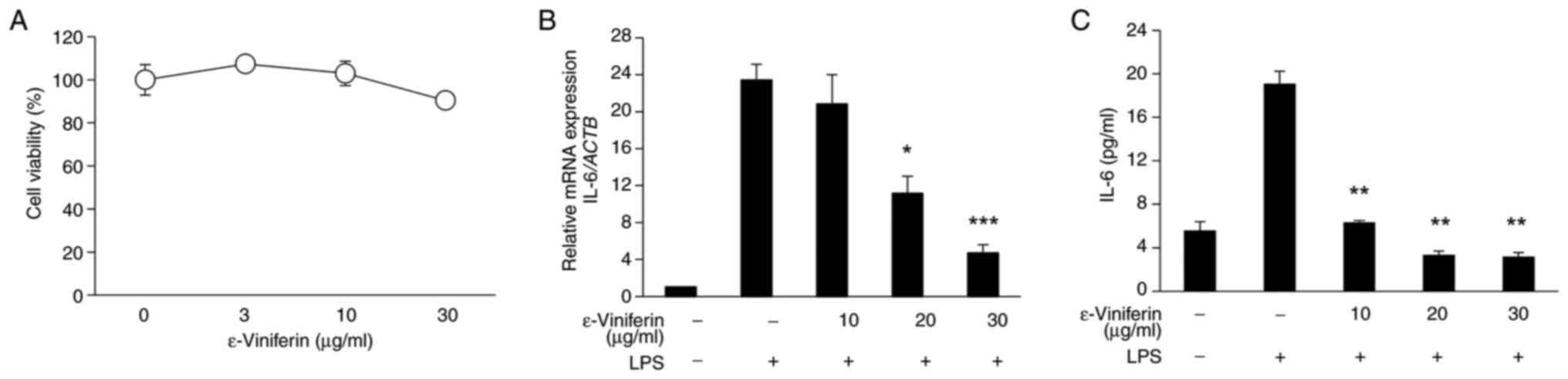

ε-viniferin exhibits anti-inflammatory

effects in human macrophage-like THP-1 cells

To further validate the anti-inflammatory effects of

ε-viniferin, we used THP-1 cells, which differentiate into

macrophage-like cells upon stimulation with phorbol esters such as

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA). ε-viniferin (30 µg/ml) was

not cytotoxic to THP-1 cells after 4 h of treatment (Fig. 4A). ε-viniferin significantly

suppressed LPS-induced IL6 mRNA expression at 20 µg/ml and

its protein production at 10 µg/ml (Fig. 4B and C). These results confirm that

ε-viniferin exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in both mouse- and

human-derived macrophage-like cells.

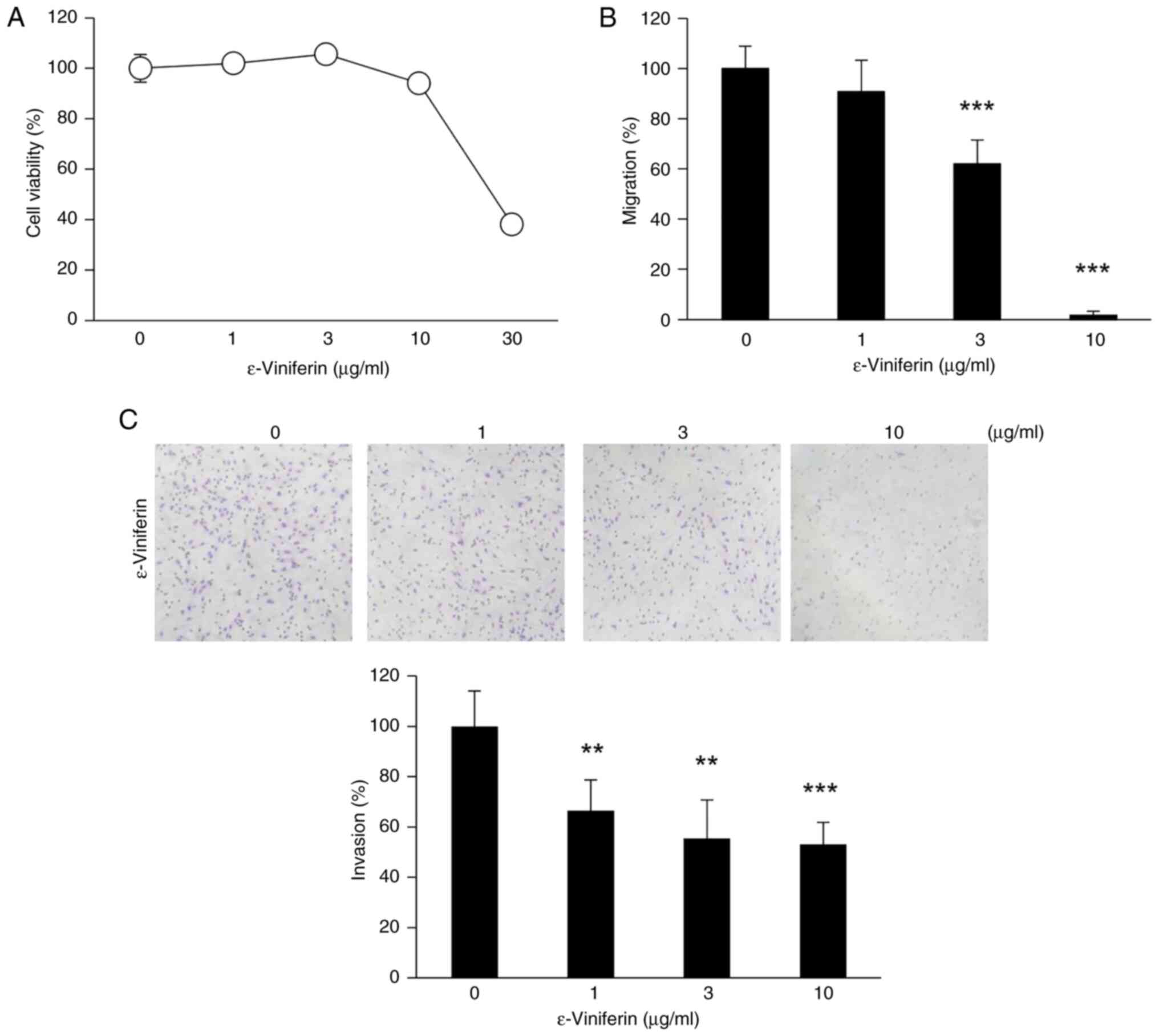

ε-viniferin inhibits migration and

invasion of HESCs and modulates inflammatory signaling

pathways

ε-viniferin was not cytotoxic to HESCs at

concentrations below 10 µg/ml (Fig.

5A). It suppressed HESC migration at a concentration of 1 µg/ml

and invasion at concentrations of 3 µg/ml and above (Fig. 5B and C). Similar inhibitory effects

on migration and invasion were observed with wild-grape extract

(Fig. S1A-C).

To further investigate the inflammatory signaling

pathways potentially involved in the anti-endometriotic effects of

ε-viniferin, a PCR array was employed (Fig. S2). Treatment of HESCs with

ε-viniferin upregulated CDKN2A, a gene that inhibits

abnormal cell growth and proliferation, and downregulated

TNFSF10, a regulator of inflammation. Additionally,

ε-viniferin suppressed the expression of metastasis-promoting genes

such as HPSE and FGFR4.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory

and anti-endometriotic effects of wild-grape extract and purified

ε-viniferin and demonstrated that both compounds effectively

suppressed LPS-induced inflammatory mediators, including NO, ROS,

and IL-6, in mouse and human macrophage cell lines. They also

inhibited the activation of NF-κB, a transcription factor that

regulates the expression of these mediators. These findings suggest

that wild-grape extract and purified ε-viniferin exhibit

anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting NF-κB mediated

inflammatory pathways. Furthermore, we validated the previously

demonstrated radical scavenging activity of ε-viniferin in

vitro. ε-viniferin consists of two stilbenol units linked

together, and its radical-scavenging activity is attributed to the

functional groups such as phenolic hydroxyl groups and double bonds

within this structure (30,31).

Previously, we reported the potential of NF-κB

inhibitor dehydroxymethylepoxyquinimicin (DHMEQ) in the treatment

of endometriosis (32). Based on

these findings and the observed NF-κB inhibition by ε-viniferin, we

further explored the potential application of ε-viniferin for its

anti-endometriotic effects. We demonstrated that ε-viniferin

effectively inhibited the migration and invasion of HESCs, a key

cell type implicated in endometriosis. Thus, ε-viniferin exhibited

potential for the treatment of endometriosis. Additionally, PCR

array analysis revealed that ε-viniferin suppressed the expression

of mobility-related genes, such as HPSE and FGFR4,

and the inflammation-promoting mediator TNFSF10. The

observed gene expression patterns revealed that ε-viniferin could

inhibit the progression of endometriosis by modulating inflammatory

regulators and metastasis-related pathways. To gain deeper

mechanistic insights into ε-viniferin's molecular targets, future

transcriptomic and/or proteomic analyses of HPSE and FGFR4

functions are warranted. In the present study, we focused on HESCs

to assess the direct anti-migratory and anti-inflammatory effects

of ε-viniferin. To further evaluate its therapeutic relevance in

the endometriotic microenvironment, future studies will examine

ε-viniferin's effects on other cellular components of endometriotic

lesions, including epithelial cells, immune cells, and vascular

endothelial cells.

While our current study focused on the NF-κB

pathway, it is important to explore broader signaling networks to

fully understand the therapeutic effects of ε-viniferin. Previous

studies (22,27) reported that ε-viniferin suppresses

inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and TGF-β, which are

associated with the JAK/STAT and TGF-β pathways. These findings

suggest that ε-viniferin may have broader anti-inflammatory effects

beyond NF-κB inhibition. In addition, our PCR array data showed

that ε-viniferin downregulated TNFSF10 (Fig. S2), a gene regulated by TRAIL and

involved in immune and apoptotic pathways. These results support

the potential of wider regulatory effects. Future studies will

investigate the JAK/STAT and TGF-β pathways to further clarify

ε-viniferin's therapeutic mechanisms.

Overall, our results suggest that ε-viniferin is a

promising anti-endometriosis agent with potent anti-inflammatory

effects, which are crucial for managing disease progression.

ε-viniferin-based therapy may be a safer, non-hormonal alternative

to conventional hormonal therapies, which often cause side effects

such as bone loss and menstrual irregularities. While these

findings strongly support the therapeutic potential of ε-viniferin,

further in vivo and clinical studies are necessary to

confirm its efficacy and long-term safety. Moreover, previous

pharmacokinetic studies have shown that ε-viniferin accumulates in

white adipose tissue and remains in the body for extended periods

(18–20). However, critical pharmacokinetic

parameters-such as absorption rate, metabolism, and plasma

half-life-remain uncharacterized in the context of endometriosis.

Pharmacokinetic modeling and in vivo biodistribution studies

are therefore planned to optimize its therapeutic use. As a

non-hormonal agent, ε-viniferin may also be considered for

combination therapy. Although its interaction with standard

hormonal treatments remains unexplored, previous studies have shown

that resveratrol, a structurally related polyphenol, enhances the

efficacy of hormonal therapies and improves the management of

endometriosis-related pain by reducing inflammation (33). These findings raise the possibility

that ε-viniferin may offer similar combinatorial benefits. To

enhance clinical applicability, we also plan to explore combination

therapies using ε-viniferin alongside standard hormonal treatments.

Together, our findings present a novel strategy for developing

anti-endometriosis therapies by targeting both inflammation and

cell migration, paving the way for future translational

research.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Kazuyuki Ino

(General Affairs Department, Fukuyu Hospital, Fukuyu Medical

Corporation, Fukuyu, Japan) for providing support in writing and

editing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion

of Science Kakenhi (grant no. 22H03062) and the Japan Agency for

Medical Research and Development (grant no. JP18fk0310118JSPS).

Additional financial support was provided by Fukuyu Medical

Corporation.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YL, KU, SK and YN contributed to the experimental

design and manuscript preparation. YL, SK, MH and HF conducted the

experiments. YH, AW and NK contributed to the experimental design.

YL, YN and SK confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The Department of Molecular Target Medicine, to

which KU belongs, is a funding-supported laboratory financially

supported by Fukuyu Medical Corporation (Nisshin, Japan); Brunaise

Co., Ltd. (Nagoya, Japan); Shenzhen Wanhe Pharmaceutical Company

(Shenzhen, China); and Meiji Seika Pharma (Tokyo, Japan). This

study is partly supported by Fukuyu Medical Corporation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

THP-1

|

human monocytic leukemia cell line

|

|

HESCs

|

human endometrial stromal cells

|

References

|

1

|

Zondervan KT, Becker CM and Missmer SA:

Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 382:1244–1256. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pessoa de Farias Rodrigues M, Lima

Vilarino F, de Souza Barbeiro Munhoz A, da Silva Paiva L, de

Alcantara Sousa LV, Zaia V and Parente Barbosa C: Clinical aspects

and the quality of life among women with endometriosis and

infertility: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health.

20:1242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Johnson NP and Hummelshoj L; World

Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium, : Consensus on

current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 28:1552–1568.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM and Flores VA:

Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: Clinical challenges

and novel innovations. Lancet. 397:839–852. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hee L, Kettner LO and Vejtorp M:

Continuous use of oral contraceptives: An overview of effects and

side-effects. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 92:125–136. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

De Corte P, Milhoranca I, Mechsner S,

Oberg AS, Kurth T and Heinemann K: Unravelling the causal

relationship between endometriosis and the risk for developing

venous thromboembolism: A pooled analysis. Thromb Haemost.

125:385–394. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Polyzos NP, Fatemi HM, Zavos A, Grimbizis

G, Kyrou D, Velasco JG, Devroey P, Tarlatzis B and Papanikolaou EG:

Aromatase inhibitors in post-menopausal endometriosis. Reprod Biol

Endocrinol. 9:902011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pavone ME and Bulun SE: Clinical review:

The use of aromatase inhibitors for ovulation induction and

superovulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 98:1838–1844. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Takagi H, Takakura M and Sasagawa T: Risk

factors of heavy uterine bleeding in patients with endometriosis

and adenomyosis treated with dienogest. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol.

62:852–857. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bally M, Dendukuri N, Rich B, Nadeau L,

Helin-Salmivaara A, Garbe E and Brophy JM: Risk of acute myocardial

infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: Bayesian meta-analysis of

individual patient data. BMJ. 357:j19092017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hägg S, Jönsson AK and Ahlner J: Current

evidence on abuse and misuse of gabapentinoids. Drug Saf.

43:1235–1254. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rahmioglu N, Nyholt DR, Morris AP, Missmer

SA, Montgomery GW and Zondervan KT: Genetic variants underlying

risk of endometriosis: Insights from meta-analysis of eight

genome-wide association and replication datasets. Hum Reprod

Update. 20:702–716. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nishimoto-Kakiuchi A, Sato I, Nakano K,

Ohmori H, Kayukawa Y, Tanimura H, Yamamoto S, Sakamoto Y, Nakamura

G, Maeda A, et al: A long-acting anti-IL-8 antibody improves

inflammation and fibrosis in endometriosis. Sci Transl Med.

15:eabq58582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yoshino O, Yamada-Nomoto K, Kobayashi M,

Andoh T, Hongo M, Ono Y, Hasegawa-Idemitsu A, Sakai A, Osuga Y and

Saito S: Bradykinin system is involved in endometriosis-related

pain through endothelin-1 production. Eur J Pain. 22:501–510. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bruner-Tran KL, Osteen KG, Taylor HS,

Sokalska A, Haines K and Duleba AJ: Resveratrol inhibits

development of experimental endometriosis in vivo and

reduces endometrial stromal cell invasiveness in vitro. Biol

Reprod. 84:106–112. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ricci AG, Olivares CN, Bilotas MA, Bastón

JI, Singla JJ, Meresman GF and Barañao RI: Natural therapies

assessment for the treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod.

28:178–188. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Rudzitis-Auth J, Menger MD and Laschke MW:

Resveratrol is a potent inhibitor of vascularization and cell

proliferation in experimental endometriosis. Hum Reprod.

28:1339–1347. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zghonda N, Yoshida S, Araki M, Kusunoki M,

Mliki A, Ghorbel A and Miyazaki H: Greater effectiveness of

ε-viniferin in red wine than its monomer resveratrol for inhibiting

vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Biosci

Biotechnol Biochem. 75:1259–1267. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Courtois A, Atgié C, Marchal A,

Hornedo-Ortega R, Lapèze C, Faure C, Richard T and Krisa S:

Tissular distribution and metabolism of trans-ε-viniferin

after intraperitoneal injection in rat. Nutrients. 10:16602018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kim J, Min JS, Kim D, Zheng YF, Mailar K,

Choi WJ, Lee C and Bae SK: A simple and sensitive liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for

trans-ε-viniferin quantification in mouse plasma and its

application to a pharmacokinetic study in mice. J Pharm Biomed

Anal. 134:116–121. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jiménez-Moreno N, Volpe F, Moler JA,

Esparza I and Ancín-Azpilicueta C: Impact of extraction conditions

on the phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of grape stem

extracts. Antioxidants (Basel). 8:5972019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sergi D, Gélinas A, Beaulieu J, Renaud J,

Tardif-Pellerin E, Guillard J and Martinoli MG: Anti-apoptotic and

anti-inflammatory role of trans ε-viniferin in a neuron-glia

co-culture cellular model of Parkinson's disease. Foods.

10:5862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Beaumont P, Amintas S, Krisa S, Courtois

A, Richard T, Eseberri I and Portillo MP: Glucuronide metabolites

of trans-ε-viniferin decrease triglycerides accumulation in an

in vitro model of hepatic steatosis. J Physiol Biochem.

80:685–696. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Huang C, Lin ZJ, Chen JC, Zheng HJ, Lai YH

and Huang HC: α-viniferin-induced apoptosis through downregulation

of SIRT1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Pharmaceuticals

(Basel). 16:7272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang S, Ma Y and Feng J: Neuroprotective

mechanisms of ε-viniferin in a rotenone-induced cell model of

Parkinson's disease: Significance of SIRT3-mediated FOXO3

deacetylation. Neural Regen Res. 15:2143–2153. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gómez-Zorita S, Milton-Laskibar I,

Eseberri I, Beaumont P, Courtois A, Krisa S and Portillo MP:

Beneficial effects of ε-viniferin on obesity and related health

alterations. Nutrients. 15:9282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chiou WC, Huang C, Lin ZJ, Hong LS, Lai

YH, Chen JC and Huang HC: α-viniferin and ε-viniferin inhibited

TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration and

invasion in lung cancer cells through downregulation of vimentin

expression. Nutrients. 14:22942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Soni UK, Chadchan SB, Kumar V, Ubba V,

Khan MTA, Vinod BSV, Konwar R, Bora HK, Rath SK, Sharma S and Jha

RK: A high level of TGF-B1 promotes endometriosis development via

cell migration, adhesiveness, colonization, and invasiveness†. Biol

Reprod. 100:917–938. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Szewczuk LM, Lee SH, Blair IA and Penning

TM: Viniferin formation by COX-1: Evidence for radical

intermediates during co-oxidation of resveratrol. J Nat Prod.

68:36–42. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Privat C, Telo JP, Bernardes-Genisson V,

Vieira A, Souchard JP and Nepveu F: Antioxidant properties of

trans-ε-viniferin as compared to stilbene derivatives in aqueous

and nonaqueous media. J Agric Food Chem. 50:1213–1217. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin Y, Kojima S, Ishikawa A, Matsushita H,

Takeuchi Y, Mori Y, Ma J, Takeuchi K, Umezawa K and Wakatsuki A:

Inhibition of MLCK-mediated migration and invasion in human

endometriosis stromal cells by NF-κB inhibitor DHMEQ. Mol Med Rep.

28:1412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Maia H Jr, Haddad C, Pinheiro N and Casoy

J: Advantages of the association of resveratrol with oral

contraceptives for management of endometriosis-related pain. Int J

Womens Health. 4:543–549. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|