Introduction

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) has long

been recognized as a central contributor to atherosclerosis, the

underlying pathology of most cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Globally, CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality

(1). For several decades, elevated

LDL-C levels have provided the cornerstone of our understanding of

atherogenesis, and LDL-C has been the principal target of

lipid-lowering therapies (2).

In the management of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD),

European and American guidelines differ regarding the preferred

lipid markers for risk assessment and therapeutic targets. European

guidelines, particularly those from the European Society of

Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society, have

increasingly advocated for the use of non-high density lipoprotein

cholesterol (non-HDL-C) and apolipoprotein B (ApoB) as superior

indicators of atherogenic lipoprotein burden (3–5).

Non-HDL-C encompasses all atherogenic particles, including LDL,

very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), intermediate-density

lipoprotein (IDL) and lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)]. Therefore, non-HDL-C

is a more comprehensive marker than LDL-C, particularly in patients

with hypertriglyceridemia or metabolic syndrome. ApoB, which

directly reflects the number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles,

offers additional precision in risk stratification, especially when

discordance exists between LDL-C levels and particle number

(6). By contrast, the American

College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association

guidelines emphasize LDL-C as the primary target of lipid-lowering

therapy, largely due to its extensive historical validation in

randomized controlled trials (7,8).

Although non-HDL-C and ApoB are both acknowledged as

secondary or optional markers, they are not routinely prioritized

in clinical practice in the USA. This divergence reflects

differences in clinical emphasis: European guidelines prioritize a

comprehensive assessment of atherogenic risk, particularly in

complex cases, whereas American guidelines maintain a simpler,

population-level focus based primarily on LDL-C. However, as

evidence continues to accumulate regarding the prognostic value of

non-HDL-C and ApoB, clinical practices may converge in future

guideline updates.

Despite the widespread use of statins and aggressive

LDL-C reduction strategies, a considerable number of patients

continue to experience cardiovascular events, a phenomenon referred

to as residual risk (9,10). This has prompted researchers and

clinicians to look beyond total LDL-C and explore the heterogeneity

of LDL particles, particularly the role of small dense LDL (sdLDL),

in the pathogenesis of CVD (10,11).

sdLDL is a subfraction of LDL where the particles

are smaller in size, more compact in structure, and more

atherogenic compared with their larger, more buoyant LDL

counterparts (12–14). Although sdLDL comprises a

relatively small proportion of the total LDL mass, it has a

disproportionately large impact on vascular health (15,16).

Its unique metabolic and physicochemical characteristics, including

increased arterial wall penetration, prolonged plasma half-life and

heightened susceptibility to oxidative modification, render it

particularly potent in promoting endothelial dysfunction, foam cell

formation, inflammation and plaque instability (12). Unlike total LDL-C, which provides a

general estimate of cholesterol load, sdLDL is reflective of

vascular injury via an insidious lipid-driven mechanism (17,18).

The clinical significance of sdLDL is clearly

apparent in individuals with metabolic disorders (18). Patients with type 2 diabetes,

insulin resistance, obesity and metabolic syndrome often present

with a so-called lipid paradox, defined as having relatively normal

LDL-C levels but a high burden of sdLDL particles (19). In such cases, traditional lipid

profiles may underestimate cardiovascular risk, resulting in missed

opportunities for preventive intervention. This growing recognition

of sdLDL as a key contributor to residual cardiovascular risk has

started to challenge existing paradigms in cardiovascular risk

stratification and treatment, leading to the suggestion that a more

detailed, particle-based approach to lipidology is necessary

(20,21).

Despite the burgeoning evidence of its atherogenic

potential, sdLDL remains underutilized in routine clinical

practice. Its more widespread adoption has been restricted by a

number of barriers, including limited access to advanced lipid

testing, a lack of standardized measurement protocols and

inadequate integration into clinical guidelines (15,22).

Nevertheless, given advances in diagnostic technology, the

increasing availability of targeted therapies, and a shift towards

precision medicine, sdLDL is on the cusp of transitioning from

being primarily a research interest to recognition as a clinically

actionable biomarker.

The present review aims to provide a comprehensive

overview of sdLDL as an underestimated driver of atherosclerosis.

It explores the mechanistic underpinnings of sdLDL-induced vascular

damage, evaluates its diagnostic value and limitations in clinical

settings, and examines current and emerging treatment strategies

aimed at reducing sdLDL burden. Furthermore, the review discusses

future directions and the integration of sdLDL into risk assessment

models and personalized therapeutic pathways. Via this approach, it

highlights the importance of reconsidering how lipid-associated

cardiovascular risk should be assessed and treated.

The atherogenicity of sdLDL

sdLDL particles represent a highly atherogenic

subfraction of LDL-C that contributes disproportionately to the

initiation and progression of atherosclerosis (13,23).

Although these particles are a minor component of total LDL, their

biological behavior renders them potent drivers of vascular

pathology (24). Understanding the

atherogenic nature of sdLDL requires consideration of the

structural features of these particles, along with their metabolic

characteristics, interactions with the arterial wall, and role in

endothelial dysfunction and plaque formation (24–26).

There is currently no universally accepted cut-off

for defining an elevated sdLDL particle concentration. This lack of

standardization complicates the interpretation of sdLDL elevation

in different populations and clinical contexts (26). Metabolic remodeling of LDL results

in sdLDL particles that are cholesterol-depleted, triglyceride-rich

and prone to oxidation (24).

Critically, sdLDL particles have a prolonged half-life in plasma

due to reduced affinity for the LDL receptor. This leads to the

particles existing for a prolonged time in circulation, thereby

increasing the likelihood of them undergoing further atherogenic

modifications (27,28) (Table

I).

| Table I.Summary of key concepts in the

atherogenicity of sdLDL. |

Table I.

Summary of key concepts in the

atherogenicity of sdLDL.

| Aspect | Key points | Advantages | Challenges | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Definition and

relevance | sdLDL is a small,

dense sub-fraction of LDL-C with disproportionately high

atherogenic potential | Recognizing sdLDL

explains residual cardiovascular risk despite normal LDL-C | Not routinely

measured in clinical practice | (14) |

| Size and

structure | 18-20.5 nm

diameter; dense, triglyceride-rich, cholesterol-poor particles with

prolonged plasma residence time | Explains enhanced

atherogenic potential compared with that of larger LDL | Requires

specialized testing, e.g., NMR or gradient gel electrophoresis | (26) |

| Metabolic

characteristics | Poor LDL receptor

affinity; more likely to remain in circulation and undergo

oxidative modification | Identifies patients

with increased oxidative risk and prolonged lipid exposure | No standardized

thresholds across populations; high variability | (24) |

| Endothelial

penetration | Easily traverses

the endothelium and binds arterial wall proteoglycans | Helps explain early

subendothelial retention in atherogenesis | Challenging to

assess or visualize directly in vivo | (24) |

| Susceptibility to

oxidation | Enriched in

polyunsaturated fats and depleted in antioxidants such as vitamin

E, making it prone to oxidation | Oxidized sdLDL

triggers immune and inflammatory responses | Not distinguished

by standard lipid panels; requires indirect evidence | (31) |

| Pathological

effects of oxLDL | Promotes

endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and foam cell formation | Target for

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant therapies | Lack of specific

inhibitors of sdLDL oxidation in current practice | (32) |

| Inflammatory and

thrombotic role | Activates NF-κB,

promotes the release of cytokines, e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α, and

promotes platelet aggregation | Links lipid

abnormalities with systemic inflammation and thrombosis | Mechanistic

complexity makes therapeutic targeting challenging | (36) |

| Endothelial

dysfunction | Reduces nitric

oxide production; increases oxidative stress and vascular tone

loss | Early marker of

vascular injury; potential target for early interventions | Few treatments

directly reverse endothelial dysfunction associated with sdLDL | (29) |

| Plaque

instability | Associated with

thin fibrous caps, large necrotic cores, and macrophage-rich

plaques, which are features of rupture-prone lesions | Provides insight

into acute coronary syndrome pathogenesis | Imaging or

detecting sdLDL-rich plaques in vivo is limited | (48) |

| Clinical

associations | Elevated in

metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and

obesity, even when LDL-C appears normal | Identifies patients

with hidden high-risk beyond LDL-C levels | Frequently missed

in standard risk assessments | (93) |

| Epidemiological

evidence | Independently

associated with cardiovascular events, e.g., in the Quebec

Cardiovascular study and ARIC study | Strong

justification for inclusion in future risk prediction models | Longitudinal data

required to determine whether sdLDL reduction improves

outcomes | (52) |

| Clinical

implications | Should be

considered a therapeutic and diagnostic target in modern

cardiometabolic care | Guides precision

medicine strategies and residual risk management | Integration into

guidelines, broader awareness among clinicians, and cost-effective

testing are necessary | (24) |

A defining feature of sdLDL is its enhanced ability

to penetrate the endothelial barrier and accumulate within the

subendothelial space of arteries. Beyond their smaller size, sdLDL

particles exhibit altered surface characteristics-such as reduced

sialic acid content, increased negative charge, and lower

phospholipid content-that facilitate passage across the endothelium

(14,29). Once within the arterial intima,

these modifications also confer a stronger binding affinity to

proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix, promoting their

retention and thereby amplifying their atherogenic potential.

The particles become trapped by arterial wall

proteoglycans and, once retained, are highly susceptible to

oxidative modification, a key initiating event in atherogenesis

(15). This susceptibility to

oxidation is further increased by a relative lack of endogenous

antioxidants such as vitamin E, and by a lipid core enriched in

polyunsaturated fatty acids that are prone to peroxidation

(30).

Oxidized sdLDL (oxLDL) has been shown to exert a

range of pathological effects (13,16,31)

(Table II). It promotes

endothelial dysfunction by reducing nitric oxide bioavailability

and increasing the expression of vascular adhesion molecules,

including vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular

adhesion molecule-1 (22,30,32).

The adhesion molecules facilitate the recruitment of circulating

monocytes, which then migrate into the arterial intima and

differentiate into macrophages. These macrophages then internalize

oxLDL via scavenger receptors, becoming lipid-laden foam cells that

form the basis of early atherosclerotic plaques (32–35).

| Table II.Summary of the cellular and molecular

mechanisms of sdLDL in atherogenesis. |

Table II.

Summary of the cellular and molecular

mechanisms of sdLDL in atherogenesis.

| Mechanism | Key features | Molecular players

and outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Structural

features | Small size (15–20

nm), dense core, triglyceride-rich, cholesterol-depleted | Increased arterial

permeability; prolonged circulation due to reduced LDL receptor

affinity | (24) |

| Endothelial

dysfunction | Enhanced

endothelial penetration via proteoglycan binding | ↑ Oxidative stress;

↓ nitric oxide bioavailability; ↑ VCAM-1/ICAM-1 expression | (51) |

| Oxidative

susceptibility | Lipid core rich in

polyunsaturated fatty acids; low antioxidant content | Rapid oxidation to

oxLDL; activation of scavenger receptors, e.g., LOX-1 and CD36 | (40) |

| Foam cell

formation | Macrophage uptake

of oxidized sdLDL via scavenger receptors | Lipid-laden foam

cells; NLRP3 inflammasome activation; ↑ IL-1β and IL-6 | (35) |

| Inflammatory

signaling | NF-κB activation;

cytokine release | ↑ TNF-α, MCP-1;

recruitment of monocytes/macrophages; vascular inflammation | (42) |

| Plaque

instability | Promotion of

necrotic core formation; thin fibrous cap | Metalloproteinase

activation; smooth muscle cell apoptosis; ↑ plaque rupture

risk | (47) |

| Prothrombotic

effects | Platelet

activation; tissue factor expression | ↑ Fibrinogen; ↑

PAI-1; thrombus formation post-plaque rupture | (41) |

| Metabolic

interactions | Association with

insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridemia | ↑ ApoC-III; ↓ LDL

receptor clearance; CETP-mediated lipid exchange | (39) |

Beyond foam cell formation, sdLDL also contributes

to a pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic vascular environment

(22,24,26,36)

(Table II). It activates

transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), leading to

the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6

(IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α and monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1 (37–42). This inflammatory response drives

further immune cell infiltration, promotes smooth muscle cell

proliferation, and contributes to extracellular matrix remodelling

(37,43,44).

In addition, sdLDL induces platelet aggregation and

promotes a pro-coagulant state, thereby increasing the risk of

thrombotic events, including myocardial infarction and ischemic

stroke (37,43).

Elevated levels of sdLDL are closely associated with

endothelial dysfunction (29), an

early marker of vascular injury. sdLDL impairs vasodilation by

reducing the synthesis of nitric oxide and increasing oxidative

stress within endothelial cells (38). This disruption of vascular

homeostasis facilitates further lipoprotein infiltration and immune

cell activation, thereby sustaining a self-reinforcing cycle of

injury and repair (45).

In a study by Miceli et al (46), the histological analysis of human

atherosclerotic plaques confirmed that lesions enriched in sdLDL

are more likely to exhibit features of instability, including thin

fibrous caps, large necrotic lipid cores and extensive inflammatory

cell infiltration (47). Such

features increase the likelihood of plaque rupture, an event that

can trigger acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and sudden cardiovascular

death (48).

Clinically, sdLDL concentrations are often elevated

in individuals with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, obesity

and insulin resistance, all of which are conditions characterized

by atherogenic dyslipidemia (39,40,49–51).

Notably, patients with these metabolic disturbances may present

with normal or near-normal LDL-C levels, while harboring a

predominance of sdLDL particles, thereby evading conventional risk

stratification. Epidemiological studies, including the Quebec

Cardiovascular Study and the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

(ARIC) Study, have demonstrated that elevated sdLDL levels are

independently associated with an increased cardiovascular risk,

even after adjustment for total LDL-C and other traditional risk

factors (52).

Given its distinct biological behaviour and strong

association with residual cardiovascular risk, sdLDL should be

considered a critical target for both diagnostic assessment and

therapeutic intervention in modern cardio-metabolic care.

Diagnostic significance and limitations in

clinical practice

Although total LDL-C has long been a cornerstone of

cardiovascular risk assessment and lipid-lowering strategies, the

recognition of sdLDL as a highly atherogenic subfraction has

prompted a critical re-evaluation of traditional diagnostic

paradigms. Increasing evidence suggests that conventional lipid

panels, which typically measure total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C and

triglycerides, may not sufficiently capture the full spectrum of

lipoprotein-associated cardiovascular risk, particularly in

individuals with metabolic dysregulation (53,54).

In this context, sdLDL has emerged as a powerful and independent

predictor of ASCVD, especially in populations that may appear to be

at low risk according to conventional criteria (55–57)

(Table III).

| Table III.Diagnostic relevance and clinical

limitations of sdLDL. |

Table III.

Diagnostic relevance and clinical

limitations of sdLDL.

| Aspect | Key insights and

clinical relevance | Limitations and

challenges | Solutions and

opportunities | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Clinical

importance | sdLDL is a highly

atherogenic subfraction linked to residual cardiovascular risk,

even in patients with normal LDL-C | Often overlooked in

standard lipid panels and clinical guidelines | Use sdLDL to

improve risk stratification, particularly in patients with

metabolic syndrome or diabetes | (14) |

| Risk

stratification | Independently

predicts ASCVD events and coronary calcification; validated in

large cohorts, e.g., Quebec, ARIC and MESA | Predictive value

may vary by population or sdLDL threshold | Combine sdLDL with

other markers, e.g., apoB, LDL-P and/or HDL-C, for a more

comprehensive lipid risk profile | (56) |

| Measurement

methods | Techniques include

NMR, electrophoresis, precipitation, and enzymatic assays; direct

methods are becoming more accessible | High cost, low

availability, and lack of inter-laboratory standardization | Use validated,

standardized methods and maintain consistency across serial

testing | (20) |

| Cut-off values | sdLDL thresholds

differ by method and population; no universal reference ranges

exist | Lack of standard

cut-offs limits clinical decision-making | Develop and adopt

population-specific reference values; interpret results

contextually | (62) |

| Association with

diabetes | sdLDL is commonly

elevated in type 2 diabetes and contributes to cardiovascular

risk | Not all diabetic

patients show increased risk from sdLDL; context matters | Interpret alongside

glycemic control and other lipid metrics; use as an adjunct, not a

replacement | (58) |

| Therapeutic

use | Helps identify

residual risk in statin-treated patients; may inform therapy

intensification | No defined target

levels or verified benefits from lowering sdLDL directly | Use sdLDL to guide

treatment in high-risk patients pending outcome data | (78) |

| Pre-analytical

considerations | Stable in frozen

serum for up to 30 days; fasting preferred for accuracy | Hemolysis, lipemia

or icterus can compromise results; non-fasting samples reduce

accuracy | Standardize patient

preparation and reject samples that are compromised | (59) |

| Indirect

surrogates | Non-HDL-C and apoB

correlate with sdLDL and are practical for routine use | Not specific to

sdLDL and may underrepresent sdLDL burden in certain cases | Use when sdLDL

testing is unavailable; supplement with direct sdLDL if

necessary | (57) |

| Emerging tools | Tools such as the

LP-IR index and advanced sub-fraction profiling aid in precision

risk assessment | Limited clinical

validation and lack of interpretative guidelines | Investigate in

research; potential role in individualized therapy | (94) |

| Clinical

integration | sdLDL testing adds

value in selected patients with unexplained residual risk or

complex lipid profiles | Not incorporated

into current guidelines or risk calculators | Use as a

supplemental test, particularly in metabolic syndrome, lean

obesity, or discordant lipid phenotypes | (61) |

Numerous epidemiological studies have shown that

elevated sdLDL levels are strongly associated with an increased

risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, even after adjustment

for total LDL-C and other conventional risk factors (25,52,58,59).

This predictive strength is particularly notable in individuals

with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance, in

whom sdLDL concentrations are often elevated despite normal LDL-C

levels. In these populations, sdLDL is frequently accompanied by

high triglyceride and low HDL-C levels, forming a pro-atherogenic

lipid profile that accelerates plaque development and increases the

risk of plaque instability and cardiovascular events (20,39,60,61).

The clinical utility of sdLDL as a risk marker is

closely associated with its sensitivity and specificity. sdLDL

demonstrates a high sensitivity for detecting an increased ASCVD

risk in patients with metabolic dysfunction or residual risk, even

when LDL-C is optimally controlled (56,62).

Its small particle size, greater arterial wall penetration and

heightened susceptibility to oxidation allow sdLDL to reflect early

vascular injury and subclinical atherosclerosis that may not be

captured by standard lipid panels. However, the specificity of

sdLDL is context-dependent (61).

Although elevated sdLDL is highly specific for increased

cardiovascular risk in high-risk groups such as diabetics and

individuals with metabolic syndrome, its specificity may be lower

in the general population, where sdLDL levels can overlap between

healthy and at-risk individuals (24,60,63).

Furthermore, assay variability and lack of standardized cut-off

values can affect both sensitivity and specificity, underscoring

the requirement for harmonized measurement protocols.

The diagnostic performance of sdLDL is enhanced when

combined with other biomarkers, such as ApoB, or inflammatory

markers, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP),

which can improve sensitivity and specificity when identifying

individuals with the highest risk (64,65).

Despite its clear prognostic value, the routine

measurement of sdLDL in clinical practice remains limited, largely

due to technical barriers, a lack of standardization and its

absence from most current guidelines. Nevertheless, in select

high-risk populations, particularly those with persistent

cardiovascular risk despite optimal LDL-C levels, the

quantification of sdLDL may provide valuable additional prognostic

information to guide personalized treatment strategies. These

factors indicate that sdLDL may be considered as a sensitive and

clinically meaningful marker for ASCVD risk, particularly in

patients with metabolic abnormalities or unexplained residual risk.

Standardizing sdLDL assays and integrating sdLDL measurement into

risk assessment algorithms may facilitate early detection and

enable more targeted interventions for those patients at the

greatest risk of cardiovascular events.

A major diagnostic implication of sdLDL is that it

can identify individuals with elevated residual cardiovascular

risk, specifically those whose total LDL-C levels fall within the

normal or near-normal range but who harbour a high concentration of

small, dense and highly atherogenic LDL particles. This situation

is frequently observed in patients with type 2 diabetes, insulin

resistance, obesity, metabolic syndrome and certain individuals

with so-called ‘lean’ metabolic obesity (66). In such cases, relying on the

standard LDL-C metric may give a false sense of security, while

elevated sdLDL levels silently contribute to subclinical

atherosclerosis (67).

Numerous epidemiological and clinical studies have

demonstrated the independent prognostic value of sdLDL (68–70).

For example, the Quebec Cardiovascular Study showed that high

concentrations of sdLDL were strongly associated with an increased

risk of ischemic heart disease, even after adjusting for LDL-C and

other conventional risk factors (71,72).

Similar associations were observed in the ARIC study and the

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, where sdLDL predicted

coronary artery calcium progression and cardiovascular events

(73,74).

These findings underscore the importance of moving

beyond a simple assessment of total cholesterol, and also

considering lipoprotein quality and particle size distribution when

performing a clinical evaluation (75,76).

Importantly, sdLDL may contribute to residual

cardiovascular risk in patients with otherwise normal LDL-C levels.

Numerous studies have shown that individuals with elevated sdLDL

levels can experience major adverse cardiovascular events, even

when standard lipid metrics appear to be well controlled (77–79).

This has spurred interest in sdLDL as a potential

marker of hidden risk, particularly in patients with premature

coronary artery disease, recurrent events or a poor response to

statin therapy (78,80).

In addition, sdLDL has been associated with specific

clinical manifestations of ASCVD, including ACS and coronary artery

calcification (81,82). Higher sdLDL concentrations have

been shown to be associated with greater plaque burden, more

extensive coronary stenosis and higher levels of circulating

inflammatory markers, including hs-CFP and IL-6.

These associations suggest that sdLDL is not merely

a marker of risk but may also play an active role in the

progression and destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques. Despite

compelling evidence, the adoption of sdLDL measurement in routine

clinical practice remains limited. Current guidelines continue to

prioritize LDL-C, non-HDL-C and ApoB, partly due to the lack of

standardization in sdLDL assays and the scarcity of outcome-based

intervention trials. However, in select high-risk populations,

particularly those with metabolic dysfunction or persistent

cardiovascular risk despite optimal LDL-C control, sdLDL

quantification may offer additional prognostic value and support

more personalized treatment strategies.

As already discussed, despite its clinical

importance, the routine measurement of sdLDL remains limited in

practice (Table III). A key

barrier is the lack of standardization in analytical techniques.

Several methods are available to quantify sdLDL, including gradient

gel electrophoresis, ultracentrifugation, nuclear magnetic

resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and ion mobility analysis (83). Each technique has its own

advantages and limitations in terms of cost, accessibility,

resolution and reproducibility. Among these, gradient gel

electrophoresis and NMR spectroscopy are the most commonly applied

in research settings (84);

however, these techniques are not widely available in standard

clinical laboratories and are often cost-prohibitive for routine

use. Furthermore, there is currently no universally accepted

cut-off value for defining elevated sdLDL concentrations. This lack

of standardization complicates interpretation across different

populations and clinical contexts. In addition, sdLDL levels are

dynamic and can be influenced by diet, insulin sensitivity, weight

changes, physical activity and pharmacological interventions

(85). Consequently, interpreting

a single measurement in isolation may not reflect long-term

cardiovascular risk, unless values are monitored longitudinally or

assessed alongside other metabolic parameters.

In clinical practice, several indirect markers have

been proposed as surrogates for sdLDL burden. These include

non-HDL-C, which has gained particular attention as a more

comprehensive risk marker compared with LDL-C alone. By

encompassing the total concentration of atherogenic lipoproteins,

including LDL, VLDL, IDL and Lp(a), non-HDL-C correlates moderately

well with sdLDL levels, and has been shown to more reliably reflect

the overall atherogenic risk (86).

ApoB100 is another widely used surrogate. ApoB100 is

a structural protein present on all liver-derived atherogenic

lipoproteins, including VLDL, IDL and LDL. Since each of these

particles carries a single molecule of ApoB100, its measurement

serves as a reliable proxy for the total number of circulating

atherogenic particles. However, an important but often overlooked

limitation is that ApoB100 does not account for all atherogenic

lipoproteins, particularly those of intestinal origin (87,88).

For example, VLDL remnants, which are partially

lipolyzed derivatives obtained during VLDL metabolism, contain

ApoB100 and have well-documented atherogenic potential (88). These remnants can bind to arterial

wall proteoglycans, become retained in the subendothelial space,

and are subsequently internalized by macrophages. This process

activates Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR2 and TLR4), leading to

localized inflammation and the progression of atherosclerosis. By

contrast, chylomicron remnants, which originate from dietary fat

metabolism in the intestine, carry ApoB48 rather than ApoB100

(89). Although not detected by

ApoB100-based assays, chylomicron remnants contribute to

atherogenesis through distinct, yet equally pathogenic mechanisms.

They have been shown to activate TLR4 and the downstream NF-κB

signaling pathway, thereby promoting endothelial dysfunction,

monocyte adhesion and foam cell formation, which are key features

of early atheromatous plaque development (90,91).

This highlights a fundamental limitation of relying

solely on ApoB100 as a marker of atherogenic particle burden.

Although ApoB100 reliably quantifies liver-derived lipoproteins, it

fails to reflect the contribution of intestinally derived

particles, such as chylomicron remnants. Consequently, a more

nuanced approach to lipoprotein profiling may be necessary in

specific clinical contexts, particularly in patients with

postprandial dyslipidemia, insulin resistance or metabolic

syndrome, where chylomicron remnants may play a disproportionately

larger role in atherogenesis (92,93).

While these markers are not specific to sdLDL, they are practical

and cost-effective tools for the estimation of atherogenic risk in

settings where direct sdLDL quantification is not possible.

Emerging approaches, such as use of the Lipoprotein

Insulin Resistance Index and advanced lipoprotein subfraction

testing using ion mobility or NMR spectroscopy, may soon provide

clinicians with more nuanced insights into lipoprotein metabolism

(94). However, these technologies

must be carefully integrated into clinical workflows, with the

establishment of clear guidelines for their interpretation and

application in clinical decision-making.

The role of sdLDL in risk stratification and

treatment intensification is a critical factor requiring

consideration (95). Although

current guidelines prioritize LDL-C as the primary target for

lipid-lowering therapy, individuals with high sdLDL may benefit

from more aggressive lifestyle and pharmacological interventions,

even when their LDL-C levels appear to be acceptable. This raises

the question of whether sdLDL should be incorporated into risk

calculators or treatment algorithms, an area that remains

underexplored in current cardiovascular guidelines.

In summary, the diagnostic significance of sdLDL is

substantial and growing, particularly in the context of

cardiometabolic diseases. Its presence signifies a hidden yet

potent atherogenic threat that may be undetected by standard lipid

screening. However, limitations in measurement standardization,

cost, accessibility and clinical integration continue to hinder its

routine application. As our understanding of lipidology deepens,

and precision medicine becomes more central to cardiovascular

prevention, sdLDL is likely to gain prominence as both a biomarker

and a therapeutic target. Bridging the gap between scientific

evidence and clinical implementation is essential to harness the

full diagnostic power of sdLDL in the fight against atherosclerosis

and CVD.

Targeted treatment strategies for sdLDL

reduction

The clinical recognition of sdLDL as a highly

atherogenic lipoprotein subclass has prompted growing interest in

the development and refinement of therapeutic strategies that

specifically address elevated sdLDL concentrations. Traditional

lipid-lowering therapies have largely focused on the reduction of

total LDL-C, although a burgeoning body of evidence suggests that

not all therapies exert equivalent effects on sdLDL concentrations

or particle composition (67,96).

As our understanding of the role of sdLDL in atherogenesis deepens,

a more nuanced and tailored approach to treatment is likely to

become both necessary and feasible (Fig. 1).

Lifestyle modification remains the primary strategy

for managing increases in sdLDL levels. Among non-pharmacological

interventions, dietary changes, particularly those that reduce

simple carbohydrate intake and improve insulin sensitivity, have

been shown to significantly impact sdLDL particles (97). Diets low in refined sugars and rich

in monounsaturated fats, such as the Mediterranean diet, can induce

a change in the LDL particle distribution towards larger, less

atherogenic forms (98). A modest

weight loss of 5–10% body weight and increased physical activity

substantially reduce sdLDL levels, particularly in

insulin-resistant individuals (99). These findings reinforce the

suggestion that sdLDL is not merely a lipid abnormality but also a

marker of broader metabolic dysfunction.

Pharmacologically, statins remain the cornerstone of

lipid-lowering therapy, as they can effectively reduce total LDL-C

and sdLDL concentrations to a certain extent (100) (Fig.

1). However, their effect on sdLDL is variable, and often less

pronounced than their effect on larger LDL particles (101,102). Statins primarily act by

upregulating LDL receptors, which preferentially clear larger, less

dense LDL particles, leaving some sdLDL particles in circulation

(103,104). Nevertheless, when combined with

other agents or used in high-intensity regimens, statins can

contribute meaningfully to sdLDL reduction (105).

Fibrates, which activate peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α, are among the most

effective agents for lowering sdLDL, particularly in individuals

with hypertriglyceridemia and mixed dyslipidemia (106–108). By reducing triglyceride-rich

lipoproteins and promoting lipolysis, fibrates shift the LDL

particle distribution from small dense particles to larger and more

buoyant forms. Clinical studies, such as the Veterans Affairs

High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial (109) and the Fenofibrate Intervention

and Event Lowering in Diabetes trial (110) have demonstrated cardiovascular

benefits in high-risk patients, although the use of pioglitazone

must be balanced against potential side effects, including weight

gain, edema and an increased risk of heart failure (111).

Niacin, also known as vitamin B3, has historically

been effective in reducing sdLDL levels, raising HDL-C levels, and

improving overall lipoprotein particle size. However, it is no

longer frequently used due to its side-effect profile and lack of

outcome benefits in clinical trials (24,112). Its use may still be considered in

select cases of severe atherogenic dyslipidemia, particularly when

other therapeutic options are insufficient or contraindicated.

Formulations of ω-3 fatty acids, particularly

icosapent ethyl, a highly purified form of eicosapentaenoic acid

(EPA) marketed as Vazkepa, have demonstrated consistent benefits in

lowering triglyceride levels and improving lipoprotein quality

(113). Beyond triglyceride

reduction, treatment with icosapent ethyl has been shown to shift

the LDL particle distribution toward larger, more buoyant LDL

particles, thereby decreasing the proportion of small dense LDL

(sdLDL), which are strongly associated with atherogenic risk.

Subanalyses of the REDUCE-IT trial and subsequent lipidomic studies

confirmed that EPA therapy not only reduces residual cardiovascular

risk in statin-treated patients but also exerts favorable effects

on LDL particle size and composition, contributing to a less

atherogenic lipid profile (114,115). These changes in lipoprotein

remodeling may represent one of the mechanistic pathways through

which icosapent ethyl provides cardiovascular protection,

independent of triglyceride lowering (116,117).

The Reduction of Cardiovascular Events With

Icosapent Ethyl-Intervention Trial reported significant reductions

in cardiovascular events in patients treated with EPA therapy,

suggesting that modulation of sdLDL levels and inflammation may

have contributed to the observed clinical benefits (118).

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

(PCSK9) inhibitors, including alirocumab and evolocumab, primarily

lower LDL-C levels by enhancing receptor-mediated clearance.

Emerging evidence suggests they may also reduce sdLDL levels,

particularly when used in combination with statins (119–121). However, their high cost is a

barrier to widespread use, although they are increasingly

recommended for high-risk patients who have persistent dyslipidemia

despite receiving statin therapy.

Antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNA

therapies targeting apoB or angiopoietin-like protein 3 are under

investigation for their ability to modulate atherogenic

lipoproteins, including sdLDL (122). These experimental approaches

highlight the potential of precision lipid therapy, where targeting

specific molecular pathways may enable the individualized

management of atherogenic lipoprotein profiles.

While lowering sdLDL concentrations represents a

promising strategy for the reduction of ASCVD risk, it is essential

to consider potential side effects of intensive sdLDL-lowering

therapies, particularly with regard to the risk of bleeding. Most

traditional lipid-lowering agents, including statins, fibrates and

PCSK9 inhibitors, are not strongly associated with increased

bleeding. However, the broader impact that targeting sdLDL has on

hemostasis and vascular integrity is not completely understood,

especially given that novel pharmacological agents and combination

therapies are currently undergoing development. Probucol, an

antioxidative and lipid-lowering drug, exemplifies the complexity

of this issue. Historically used to treat atherosclerosis and

xanthomas, probucol effectively reduces LDL-C and sdLDL levels,

largely through its antioxidant properties and its effects on LDL

particle size and oxidation (123,124). Notably, a recent study by Lang

et al (125) suggested

that probucol may offer unique benefits for patients at high risk

of hemorrhage. The study suggested that probucol has potential as a

novel therapeutic option for cerebral infarction in patients with a

high risk of bleeding, as it appears to exert protective effects on

the vasculature without significantly increasing hemorrhagic

complications (125). This

observation is clinically relevant, as aggressively lowering the

lipid level, particularly with agents that alter platelet function

or endothelial stability, has sometimes been associated with an

increased risk of bleeding, particularly in patients receiving

concomitant antithrombotic therapy or those with cerebrovascular

disease (126,127).

The apparent safety of probucol in this context may

be attributed to its antioxidant effects, which stabilize

endothelial function and reduce oxidative stress, potentially

counteracting pro-hemorrhagic mechanisms. Nevertheless, it is

essential to carefully evaluate the safety profile of

sdLDL-targeting therapies in diverse patient populations. Although

probucol may be a potential therapeutic option for patients with

ASCVD and a high risk of bleeding, its use is limited by concerns

such as QT prolongation and other non-hemorrhagic adverse effects.

Furthermore, is is unclear whether the protective profile of

probucol can be generalized to other sdLDL-lowering agents.

Despite these therapeutic advances, the integration

of sdLDL-focused strategies into clinical practice guidelines

remains limited. Major guidelines, such as those from the ACC and

ESC, continue to prioritize LDL-C, non-HDL-C and apoB as primary

targets of therapy (128). While

sdLDL is recognized to increase cardiovascular risk, it has not yet

been incorporated into routine risk calculators or treatment

algorithms. This may be partly due to the lack of standardization

in sdLDL measurement, as well as limited outcome data directly

associating reductions in sdLDL concentration with hard

cardiovascular endpoints.

Despite its limited integration into guidelines,

there is growing support for the consideration of sdLDL

measurements in certain clinical scenarios. These include patients

with residual cardiovascular risk despite optimal LDL-C control,

individuals with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes, and those

with premature or familial atherosclerotic disease. In such cases,

the presence of an increased concentration of sdLDL may justify the

intensification of therapy or the use of combination treatment

approaches, even in the absence of overt LDL-C elevation.

Targeted reduction of sdLDL is most effective and

clinically relevant during the chronic phase of ASCVD or in

individuals at high long-term risk, such as those with metabolic

syndrome, type 2 diabetes or persistent residual risk despite

optimal LDL-C control (20,129).

Chronic management allows sufficient time for

lifestyle modifications and pharmacological therapies, including

statins, fibrates, PCSK9 inhibitors, probucol and w-3 fatty acids,

to be implemented in order to exert their full lipid-modifying and

anti-atherogenic effects.

Sustained lowering of sdLDL concentration during the

chronic phase of disease has been associated with limited

atherosclerosis progression, the stabilization of vulnerable

plaques and a reduced incidence of major adverse cardiovascular

events (25,60).

By contrast, the acute phase of ASCVD, such as acute

coronary syndrome or stroke, is not the primary window for

sdLDL-targeted interventions. Although lipid-lowering therapy is

often initiated or intensified during acute events for secondary

prevention, the specific impact of sdLDL reduction in this setting

is less well established, as acute interventions are focused on

patient stabilization, and the management of thrombosis and

immediate complications. Nevertheless, the early initiation of

sdLDL-lowering therapy during hospitalization for an acute event

may lay the foundation for effective long-term risk reduction

(130,131).

Therefore, sdLDL-lowering strategies should be

prioritized for long-term risk reduction and the prevention of

recurrent events, with their main benefits being realized during

ongoing, chronic management.

To facilitate the broader adoption of sdLDL-guided

therapy, it is necessary to integrate sdLDL measurements into the

risk stratification frameworks outlined in clinical guidelines,

supported by randomized trials and real-world data demonstrating

the predictive value and therapeutic responsiveness of sdLDL

levels. In addition, the development of cost-effective standardized

assays for sdLDL quantification is essential to ensure clinical

feasibility. Table IV summarizes

both established and emerging strategies for sdLDL reduction,

highlighting their mechanisms of action, clinical roles and other

key considerations.

| Table IV.Targeted treatment strategies for

reducing sdLDL levels. |

Table IV.

Targeted treatment strategies for

reducing sdLDL levels.

| Treatment | Type | Effect on

sdLDL | Mechanism of

action | Notes and clinical

considerations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Lifestyle

modification |

Non-pharmacologic | Reduces sdLDL

concentrations; shifts to larger LDL particles | Improves insulin

sensitivity; reduces refined carbohydrate intake; increases

physical activity | Foundation of all

therapies; particularly effective in metabolic syndrome | (24) |

| Statins | Pharmacologic | Modest and variable

reduction in sdLDL | Upregulate LDL

receptors, preferentially clearing larger LDL particles | Optimum results in

combination or high-intensity regimens | (60) |

| Fibrates | Pharmacologic | Significant

reduction in sdLDL | Activate PPAR-α;

reduce triglycerides; enhance lipolysis; shift LDL to larger

particles | Particularly

effective in patients with high TG and low HDL-C | (108) |

| Pioglitazone | Pharmacologic | Reduces sdLDL;

improves lipoprotein profile | Activates PPAR-γ;

enhances insulin sensitivity; reduces inflammation; lowers TG and

increases HDL-C | Benefits high-risk

patients; side effects include weight gain and edema | (54) |

| Niacin/vitamin

B3 | Pharmacologic | Reduces sdLDL;

increases HDL-C; improves LDL particle size | Decreases hepatic

VLDL production; reduces lipolysis of adipose tissue | Limited use due to

side effects and lack of outcome benefit | (24) |

| w-3 Fatty acids

(EPA) | Pharmacologic | Modulates sdLDL and

reduces TG | Reduces hepatic TG

synthesis; alters LDL particle composition | Reduced

cardiovascular events in the REDUCE-IT phase III trial | (113) |

| PCSK9

inhibitors | Pharmacologic | May reduce sdLDL

when combined with statins | Increase LDL

receptor recycling; enhance LDL clearance | High cost;

recommended for high-risk patients with residual dyslipidemia | (121) |

| Antisense/siR NA

therapies, e.g., targeting apoB or ANGPTL3 | Experimental | Potential for sdLDL

reduction | Inhibit synthesis

of apoB or ANGPTL3; reduce atherogenic lipoprotein production | Emerging tools in

precision lipid management | (141) |

The targeting of sdLDL is an important evolution in

the management of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease

prevention. While traditional therapies influence sdLDL levels

indirectly, emerging pharmacological agents and lifestyle

strategies provide more specific and effective approaches. Bridging

the gap between sdLDL recognition and its inclusion in clinical

practice guidelines will be a key step toward precision

cardiovascular medicine. As the evidence base expands,

incorporating sdLDL into diagnostics and treatment may enhance our

ability to address residual risk and improve outcomes for patients

at high risk of atherosclerotic disease.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine

learning (ML) in sdLDL research

The rapid evolution of AI and ML is profoundly

transforming cardiovascular research, particularly in the study of

sdLDL, a key but often underestimated driver of atherosclerosis.

Historically, the measurement and clinical interpretation of sdLDL

have faced substantial challenges. Standard lipid panels do not

directly quantify sdLDL, and conventional estimation equations,

such as the Friedewald or Martin equations, often yield imprecise

results, especially in patients with elevated triglyceride levels

or atypical lipid profiles (132,133). These limitations have limited the

integration of sdLDL metrics into the routine clinical risk

assessment and management of ASCVD (Table V).

| Table V.Summary of in sdLDL research. |

Table V.

Summary of in sdLDL research.

| Domain | AI/ML

contribution | Details and

examples | Challenges and

limitations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Measurement and

estimation | Accurate prediction

of sdLDL levels | ML models, e.g.,

gradient boosting and deep neural networks, outperform

Friedewald/Martin equations, even with high TGs | Variability in

sdLDL measurement techniques, e.g., NMR vs.

ultracentrifugation | (133) |

| Risk

stratification | Enhanced

cardiovascular risk prediction | AI integrates sdLDL

with apoB, Lp(a) and inflammation markers; outperforms Framingham

Risk Score (AUC >0.85) | Lack of

standardization and validation across population subgroups | (164) |

| Explainability | Interpretable

models via SHAP | sdLDL shown to

contribute comparably to systolic blood pressure and age in

predictive models | ‘Black box’

concerns reduce clinician trust in complex models | (154) |

| Personalized

medicine | Tailored therapy

for sdLDL reduction | AI predicts

individual responses to statins, PCSK9 inhibitors and lifestyle

changes | Requires

integration of high-resolution genetic and lipidomic data | (134) |

| Therapeutic

optimization | Adaptive treatment

planning | Reinforcement

learning guides drug/lifestyle interventions; neural nets track

plaque via coronary CT angiography | Longitudinal,

multimodal datasets are limited; high computational costs | (145) |

| Clinical trials and

interventions | AI-guided lifestyle

interventions show rapid sdLDL reduction | Customized

diet/exercise plans reduce sdLDL in weeks | Scalability and

cost of implementing AI-driven personalization in real-world

settings | (144) |

| Challenges | Data heterogeneity,

generalizability, ethical concerns | Inconsistent sdLDL

assays, bias in training data, lack of model transparency | Data privacy,

underrepresentation of certain demographic groups | (149) |

| Emerging

solutions | Federated learning,

explainable AI, digital twins | Cross-institutional

model training, transparent decision-making, virtual simulations of

sdLDL progression | Early stage of

development; limited clinical integration and regulatory

guidance | (155) |

| Future outlook | AI positions sdLDL

as central in precision cardiology | Transition from

niche biomarker to a core element in personalized atherosclerosis

prevention | Large-scale

validation studies and harmonization with clinical workflows are

necessary | (156) |

AI and ML technologies are now bridging these gaps

by leveraging large-scale, multidimensional datasets that include

clinical, biochemical, genetic and imaging data (134). ML algorithms can identify

complex, non-linear relationships among lipid parameters that are

not detected by traditional statistical methods (133). Advanced models, such as gradient

boosting machines and deep neural networks, can predict sdLDL

concentrations with high accuracy, even in the presence of

confounding factors such as elevated triglyceride levels or

metabolic syndrome. These models demonstrate substantially reduced

prediction errors compared with legacy equations, and maintain a

high performance across diverse patient subgroups (Table V).

Han et al (135) developed and validated a number of

ML models, including XGBoost, Random Forest and Logistic

Regression, to predict the likelihood of LDL-C target levels being

achieved in patients with coronary artery disease treated with

moderate-dose statins. These models, trained on a large hospital

dataset, achieved respectable area under the receiver operating

characteristic curve values of ~0.695, even following significant

dimensionality reduction. Notably, SHapley Additive exPlanations

(SHAP) analysis was included to interpret the predictions made by

the models, providing transparency and clinical insight that can

guide individualized treatment strategies.

Similarly, Olmo et al (136) applied ML-driven decision tree

algorithms to cluster patients based on LDL-C levels, family

history of coronary heart disease and age. This led to the

identification of distinct risk groups with progressively higher

levels of Lp(a). Their study of >2,300 patients from a

multicenter Spanish registry revealed that nearly 39% of patients

had elevated Lp(a) levels, defined as >50 mg/dl, highlighting

the importance of using ML to stratify patients and identify those

at higher cardiovascular risk.

In another recent application of AI in lipidomics,

Tavaglione et al (137)

leveraged neural network models to assess the contribution of

lipoproteins to liver fat accumulation and inflammation,

particularly in the context of metabolic dysfunction-associated

steatotic liver disease (MASLD; formerly known as non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease) and metabolic dysfunction-associated

steatohepatitis. Using data from the UK Biobank, the research team

found that the ability of isolated hypertriglyceridemia to predict

MASLD was stronger than that of isolated hypercholesterolemia, a

finding with potential implications for targeted screening and

early intervention in dyslipidemic populations (54).

Sezer et al (138) investigated both AI and

explainable AI (XAI) techniques, including Random Forests and

Gradient Boosting, for the prediction of LDL-C from standard lipid

panels. By applying SHAP and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic

Explanations techniques, they demonstrated how XAI can bridge the

gap between predictive accuracy and clinical interpretability.

Their findings further suggested that AI-based LDL-C predictions

may offer more reliable and cost-effective alternatives to

traditional estimation formulas, particularly in large-scale

screening scenarios.

Collectively, these studies highlight a growing

trend toward the adoption of AI and ML methods in the diagnosis and

management of lipid disorders. The integration of explainable

models with clinical variables such as LDL-C, Lp(a) and

triglycerides is supporting a shift from population-based

approaches to precision cardiovascular medicine. Notably, SHAP

analysis and XAI frameworks are enhancing the ability of clinicians

to trust and act on AI-driven outputs, a critical factor for

successful clinical adoption.

Beyond estimation methods, AI-driven approaches are

redefining cardiovascular risk stratification by incorporating

sdLDL as a dynamic, actionable biomarker. Unlike static risk

scores, ML models can account for the cumulative burden of sdLDL

exposure over time and integrate it with other risk factors,

including ApoB, Lp(a) and inflammatory markers. In large cohort

studies, these AI-enhanced risk models have consistently

outperformed traditional tools such as the Framingham Risk Score,

achieving area under the curve values >0.85 (139). Notably, XAI techniques, such as

SHAP analysis, have shown that the sdLDL percentage contributes as

much to risk prediction as do established factors such as systolic

blood pressure or age, thereby highlighting its clinical

significance (140).

The impact of AI is increasingly extending into the

realm of personalized medicine. Reinforcement learning and other

adaptive algorithms are being used to tailor interventions that

specifically target sdLDL reduction. These systems can model

individual responses to statins, PCSK9 inhibitors and lifestyle

modifications, thereby optimizing treatment regimens based on the

unique lipidomic and genetic profile of each patient (141). Clinical trials using AI-generated

dietary and exercise recommendations have already reported

significant reductions in sdLDL levels within weeks, demonstrating

the potential for rapid, individualized risk mitigation (142–144). In addition, neural networks that

analyze longitudinal imaging data, such as coronary computed

tomography angiography, can identify optimal windows for

intervention by tracking the progression of atherosclerotic plaques

in relation to sdLDL fluctuations (145,146).

Despite these advances, several challenges remain

that must be addressed before AI and ML can be fully integrated

into routine sdLDL management (147,148).

Data heterogeneity remains a major barrier, as

different measurement techniques, for example, ultracentrifugation

and NMR spectroscopy, may produce inconsistent results,

complicating model training and validation. Concerns about the

generalizability of AI models also persist, particularly when they

are trained on datasets that do not adequately represent diverse

populations. Ethical considerations, including algorithmic bias and

data privacy, also require ongoing attention to ensure equitable

and responsible deployment of these technologies. In addition, the

opaque nature of certain deep learning models may undermine the

trust of clinicians and hinder their clinical adoption, thereby

underscoring the requirement for transparent and interpretable AI

systems (149).

Looking ahead, the AI and ML field is moving towards

federated learning frameworks that enable collaborative model

development across institutions without compromising patient

privacy (150,151).

The integration of XAI should further enhance

clinician confidence by making the decision-making process clearer.

In addition, so-called ‘digital twins’ or virtual patient models

are emerging that may simulate sdLDL trajectories under various

treatment scenarios, and have the potential to revolutionize

individualized care and preventative strategies (152–155).

The convergence of AI, ML and sdLDL research

represents a paradigm shift in the fight against atherosclerosis

(156). By enabling precise

estimation, robust risk prediction and personalized intervention,

these technologies are poised to elevate sdLDL from an emerging

biomarker to a central pillar of precision cardiology. As

validation studies progress and implementation barriers are

addressed, AI-driven approaches have the potential to transform the

science and practice of CVD prevention and management.

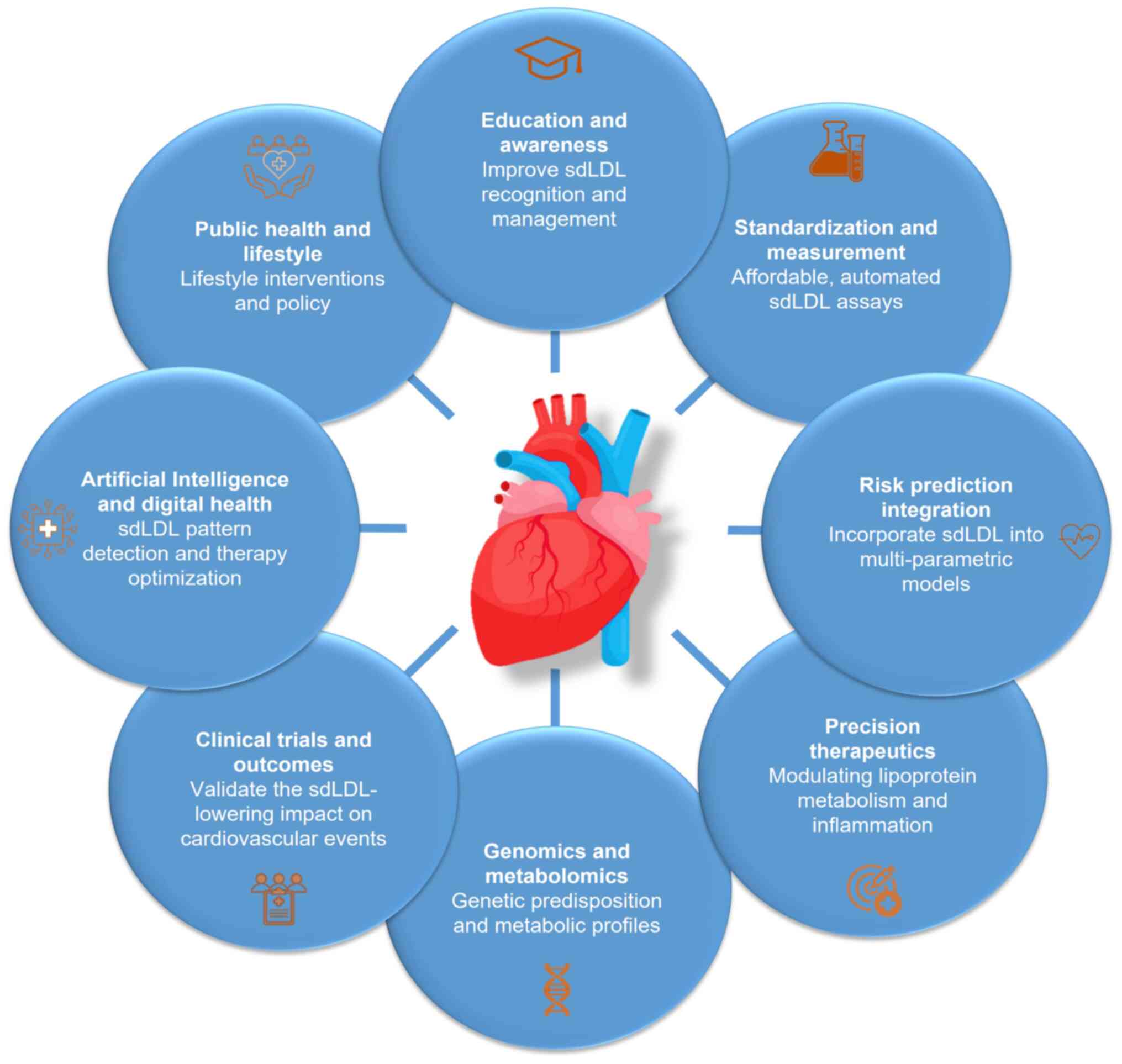

Future directions

As cardiovascular medicine enters an era

increasingly defined by precision and personalization, the

recognition of sdLDL as a critical contributor to residual

atherosclerotic risk opens numerous avenues for future research,

scientific innovation and clinical integration. The body of

evidence associating sdLDL with heightened cardiovascular morbidity

and mortality, despite standard lipid control, highlights the

necessity of redefining our understanding of lipoprotein pathology

and risk assessment (18,27). In the future, several key areas

must be addressed to fully harness the clinical potential of

sdLDL-focused strategies (Fig.

2).

First and foremost, it is essential to standardize

sdLDL measurements and increase their accessibility. Although

advanced techniques, including NMR spectroscopy, ion mobility

analysis and density gradient ultracentrifugation, have provided

invaluable insights into lipoprotein subfractions, these tools

remain largely confined to research settings (157,158). The development of affordable,

automated and reproducible assays for sdLDL detection is necessary

for widespread adoption in clinical practice (18,159). Furthermore, establishing

universally accepted cut-off values and reference ranges,

stratified by age, sex, ethnicity and comorbidities, will enhance

the interpretability and clinical relevance of sdLDL metrics.

Another critical priority is the integration of

sdLDL into existing cardiovascular risk prediction models. Current

tools, such as the ASCVD Risk Calculator and SCORE2, primarily

consider traditional lipid markers and broad demographic factors

(160). Incorporating sdLDL

concentrations into multi-parametric indices alongside ApoB,

triglycerides and inflammatory biomarkers, may substantially

improve the accuracy of risk stratification, particularly in

individuals with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes, or those

with normal LDL-C levels but persistent vascular disease.

At the therapeutic level, the evolution of precision

medicine approaches is necessary. Although current lipid-lowering

therapies, including statins and fibrates, partially reduce sdLDL

levels, more selective and sdLDL-targeted interventions are

required (161,162). Future pharmacological studies

should prioritize agents that modify hepatic lipoprotein secretion,

lipolysis and receptor-mediated lipoprotein to preferentially

reduce sdLDL formation and persistence. Furthermore, combinatorial

therapies addressing both lipid and inflammatory signaling pathways

may yield synergistic benefits for patients with a high sdLDL

burden.

Personalized treatment algorithms that incorporate

genetic and metabolic profiling could further enhance the targeting

of sdLDL. Advances in genomics and metabolomics may help to

identify individuals who are genetically predisposed to overproduce

or inefficiently clear sdLDL. This information, combined with

real-time lipidomic and glycemic monitoring, may guide

individualized therapeutic regimens and dynamic risk tracking over

time.

Longitudinal and interventional studies are required

to clarify the clinical benefits of lowering sdLDL levels. Although

the atherogenicity of sdLDL has been well documented, conclusive

evidence that reducing sdLDL leads to improvements in

cardiovascular outcomes remains elusive. Large, well-powered

randomized controlled trials are necessary to determine whether

targeting sdLDL levels, either through lifestyle or pharmacological

means, leads to measurable reductions in myocardial infarction,

stroke and cardiovascular death, particularly in high-risk

populations (Fig. 2).

The integration of AI and digital health

technologies in routine sdLDL assessment and management is a

promising strategy. ML algorithms could be trained to detect

patterns of sdLDL elevation based on indirect clinical and

biochemical markers, thereby reducing dependence on direct

measurement. AI-driven platforms may also leverage patient-specific

data streams from electronic health records and wearable devices to

optimize therapy selection, adherence and monitoring (134,163,164).

Lipidomics, an emerging discipline within the

broader field of metabolomics, focuses on the comprehensive

analysis of cellular lipid profiles using advanced analytical

chemistry techniques and high-throughput technological platforms.

Unlike traditional lipid panels that measure only a small number of

lipid classes, such as total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C and

triglycerides, lipidomics enables the simultaneous identification

and quantification of hundreds to thousands of distinct lipid

species within biological samples (165). This comprehensive approach is

achieved using sophisticated tools, including mass spectrometry,

NMR spectroscopy and liquid chromatography, which together provide

high resolution and sensitivity in lipid analysis (166,167).

The application of lipidomics in cardiovascular

research has enhanced our understanding of lipid metabolism and its

role in atherosclerosis (168).

Specifically, lipidomics allows for the detailed characterization

of lipoprotein subfractions, including sdLDL (157,169). By profiling the molecular

composition of sdLDL particles, including their enrichment in

triglycerides, depletion of cholesterol, and susceptibility to

oxidative modifications that increase atherogenicity, lipidomics

can reveal mechanistic links between specific lipid species and the

pathogenesis of ASCVD (170,171).

Lipidomics offers the potential to identify novel

lipid biomarkers that may improve risk stratification beyond

conventional measures (165). For

example, recent studies have uncovered unique lipid signatures that

are associated with increased sdLDL levels in patients with

metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance

(172–174). These signatures include specific

oxidized phospholipids, ceramides and sphingolipids, which have

been implicated in endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and plaque

instability. Integrating such lipidomic data with clinical and

genetic information may increase the precision and

individualization of risk assessment, as well as the development of

targeted therapies aimed at modulating pathogenic lipid

species.

Despite its promise, the clinical implementation of

lipidomics is hindered by a lack of standardized protocols, robust

data interpretation frameworks and cost-effective analytical

platforms. However, as technology advances and a deeper

understanding of lipid biology is obtained, lipidomics is poised to

become an indispensable tool in research and clinical practice,

particularly in the context of sdLDL and its role in residual

cardiovascular risk. Future studies leveraging lipidomic profiling

are likely to yield new insights into the molecular mechanisms of

atherogenesis, facilitating the transition towards precision

cardiovascular medicine.

Finally, promoting greater awareness and education

among clinicians and patients is paramount. Despite its clinical

significance, sdLDL remains under-recognized in numerous healthcare

settings. Medical curricula, continuing education programs and

clinical guidelines should be updated to reflect the evolving

understanding of sdLDL, ensuring that healthcare providers are

equipped to interpret, communicate and act on sdLDL-associated

information effectively.

In summary, the future of sdLDL research and

application lies in the convergence of technological innovation,

translational science and personalized care. By advancing

measurement techniques, integrating sdLDL into risk models,

validating targeted therapies and implementing health system-level

changes, insights into the pathophysiological role of sdLDL can be

translated into actionable clinical strategies. In so doing,

cardiovascular prevention may become both more comprehensive and

more precisely targeted.

Conclusion

Over the last few decades, our understanding of

atherosclerosis has evolved from a simplistic cholesterol-centric

view to a complex appreciation of lipid subfractions, inflammation,

endothelial dysfunction and metabolic interactions. Among these

factors, sdLDL has emerged as a critical, yet under-recognized,

contributor to CVD. Its unique physicochemical properties, such as

elevated arterial wall permeability, prolonged circulation time and

heightened susceptibility to oxidation, result in its

atherogenicity being greater than that of larger LDL particles. A

growing body of evidence demonstrates that sdLDL plays a central

role in promoting endothelial injury, foam cell formation,

inflammation and plaque instability, all of which are key features

of progressive atherosclerosis.

Despite these insights, sdLDL remains

insufficiently addressed in clinical diagnostics and practice

guidelines. Traditional lipid panels do not detect sdLDL, and so

potentially overlook high-risk individuals, particularly those with

metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes or normocholesterolemia. The

absence of routine sdLDL measurement may lead to suboptimal risk

assessment and missed opportunities for early intervention.

Integrating sdLDL into diagnostic protocols, either directly

through specialized testing or indirectly via surrogate markers

such as ApoB and non-HDL-C, could refine cardiovascular risk

prediction and guide personalized treatment strategies.

Therapeutically, although conventional

lipid-lowering agents such as statins and fibrates can reduce sdLDL

levels, emerging therapies, including w-3 fatty acid formulations,

PCSK9 inhibitors and RNA-targeting agents, have the potential to

provide more targeted and effective sdLDL modulation. Additional

clinical trials are required to determine whether specific

sdLDL-lowering strategies translate into improved long-term

cardiovascular outcomes. Alongside pharmacological innovations,

lifestyle modifications, particularly those aimed at improving

insulin sensitivity and reducing the levels of triglyceride-rich

lipoproteins, remain crucial for managing sdLDL-associated

risk.

Looking ahead, the future management of sdLDL must

be grounded in an integrative approach that combines advanced

diagnostics, precision therapeutics and population-level

interventions. Efforts should focus on standardizing measurement

techniques, educating clinicians and updating clinical guidelines

to reflect the evolving understanding of the pathophysiological

role of sdLDL.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by program-targeted funding from the

Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of

Kazakhstan: ‘Development of new screening methods, to prevent early

mortality and treatment of cardiovascular-diseases of

atherosclerotic genesis in patients with atherosclerosis’ (grant

no. BR21881970).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MB was responsible for writing, reviewing and

editing the manuscript, supervision and project administration. TS

was responsible for writing the original draft of the manuscript,

defining the scope and focus of the review, devising a literature

search strategy, formal analysis and conceptualization. TIR was

responsible for collecting data. SA was responsible for writing the

manuscript, methodology, analysis and conceptualization. AK was

responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript, formal

analysis, methodology and conceptualization. GM was responsible for

editing the manuscript, methodology and formal analysis. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Timur Saliev: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5696-6363.

References

|

1

|

Agnello F, Ingala S, Laterra G, Scalia L

and Barbanti M: Novel and emerging LDL-C lowering strategies: A new

era of dyslipidemia management. J Clin Med. 13:12512024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mukherjee D and Nissen SE: Lipoprotein (a)

as a biomarker for cardiovascular diseases and potential new

therapies to mitigate risk. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 22:171–179. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

German CA and Shapiro MD: Assessing

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk with advanced lipid

testing: State of the science. Eur Cardiol. 15:e562020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Antoniades C and West HW: ESC CVD

Prevention Guidelines 2021: Improvements, controversies, and

opportunities. Cardiovasc Res. 118:e17–e19. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS,

Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, et

al: 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute

and chronic heart failure: Developed by the task force for the

diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the

European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution

of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Rev Esp Cardiol

(Engl Ed). 75:5232022.

|

|

6

|

De Oliveira-Gomes D, Joshi PH, Peterson

ED, Rohatgi A, Khera A and Navar AM: Apolipoprotein B: bridging the

gap between evidence and clinical practice. Circulation. 150:62–79.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA,

Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A,

Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, et al: 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the

primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Executive summary: A

report of the American college of Cardiology/American heart

association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 74:1376–1414. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C,

Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S,

Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, et al: 2018

AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline

on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the American

college of Cardiology/American heart association task force on

clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 139:e1082–e1143. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Akyol O, Yang CY, Woodside DG, Chiang HH,

Chen CH and Gotto AM: Comparative analysis of atherogenic

lipoproteins L5 and Lp(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular

disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 26:317–329. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Proctor SD, Wang M, Vine DF and Raggi P:

Predictive utility of remnant cholesterol in atherosclerotic

cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 39:300–307. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Attiq A, Afzal S, Ahmad W and Kandeel M:

Hegemony of inflammation in atherosclerosis and coronary artery

disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 966:1763382024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|