Introduction

Lung cancer remains a leading cause of global

mortality (1), with tobacco use,

occupational exposure and genetic factors being key contributors to

its high incidence (2). Lung

adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma are the two

main subtypes of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (3). Notably, with the advent of precision

medicine, treatment strategies for LUAD have undergone

transformative changes, incorporating targeted therapy and

immunotherapy (4). However,

genetic mutations, acquired resistance and epigenetic modifications

inevitably lead to drug resistance in patients (5). Therefore, identifying novel

therapeutic markers to more accurately characterize LUAD is crucial

for overcoming treatment resistance.

Cancer cells, which exhibit uncontrolled

proliferation, require elevated cholesterol levels for membrane

synthesis and other vital functions (6), making cholesterol metabolism

reprogramming a common feature in cancer. Dysregulation of

proto-oncogenes and oncogenes results in notable increases in

cholesterol uptake and the production of its derivatives within

tumor cells (7,8). Additionally, the tumor

microenvironment (TME), characterized by factors such as acidity

and inflammation, further promotes cholesterol biosynthesis and

uptake (9,10). 22-Hydroxycholesterol, a metabolite

of cholesterol abundant in the TME (11), recruits neutrophils by binding to

CXCR2, thereby exerting immunosuppressive effects (12). Tumor-associated macrophages also

undergo functional and phenotypic alterations due to shifts in

cholesterol metabolism, contributing to tumor progression (13). In summary, cholesterol and its

metabolites drive tumor progression by enhancing tumor malignancy

and remodeling the TME. Therefore, statin-based inhibition of

active cholesterol metabolism has emerged as a promising antitumor

strategy (14).

The aim of the present study was to identify

potential biomarkers associated with cholesterol metabolism in the

diagnosis of LUAD. The study aimed to screen differentially

expressed genes related to cholesterol metabolism between LUAD and

normal lung tissues, analyze their gene functions, and prognostic

and clinical relevance, and perform cell experiments to validate

the functions of the selected genes. The current study established

a robust diagnostic and prognostic model for patients with

LUAD.

Materials and methods

Data collection and processing

RNA-sequencing data from patients with LUAD were

obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), Subsequently, R

project (v4.0.4; http://www.r-project.org/) was used for rigorous

quality control and screening to remove duplicate samples, ensuring

dataset uniqueness and reliability. Samples with a survival time of

<30 days were excluded to ensure complete and usable survival

data. A training set consisting of 485 LUAD samples and 59

paracancerous tissues was selected from TCGA, and a validation set

(GSE72094) (15) was obtained from

the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds), comprising 398

samples with complete clinical data. cholesterol metabolism-related

genes (CMRGs) were downloaded from MSigDB (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) (16), totaling 158 genes.

Consensus cluster analysis

Univariate Cox regression analysis was performed to

assess the relationship between CMRGs and prognosis. TCGA cohort

was clustered using the consensus clustering algorithm implemented

through the ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ R package (v3.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/3.0/bioc/html/ConsensusClusterPlus.html)

(17). Clustering was conducted

with the PAM algorithm based on 1-Pearson correlation distance,

with 80% of the samples repeated 1,000 times. The optimal number of

clusters was determined through analysis of the empirical

cumulative distribution function (CDF) plot. A Sankey diagram was

generated using the ‘ggplot2’ R package (v 3.3.0; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html).

Gene set enrichment analysis

(GSEA)

GSEA was performed using ‘c5.go.v7.5.1.symbols’

(Gene Ontology terms) and ‘c2.cp.kegg.v7.5.1.symbols’ (Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) from the molecular signature

database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) to explore

biological signatures and pathways across different clusters

(18).

TME analysis

Using the single sample GSEA algorithm, the activity

levels of 28 immune cell types were evaluated for each sample (in

the GSE72094 dataset) (19). The

ESTIMATE algorithm, applied to pre-screened immune-related gene

expression data, was used to predict cell infiltration and tumor

purity in LUAD tissues (TCGA) (20).

Construction of cholesterol metabolism

gene signature

Differentially expressed genes between clusters were

identified using ‘limma’ R package (v3.42.2; http://bioconductor.org/packages/3.10/bioc/html/limma.html)

analysis of variance (21), and

genes with a P-value of <0.05 and fold change of ≥2 were further

analyzed using univariate or LASSO Cox regression. The risk index

for each patient was calculated by multiplying the expression

levels of target genes by their corresponding coefficients. Based

on the median risk index, patients with LUAD were categorized into

high-risk and low-risk groups for subsequent analyses. Kaplan-Meier

curves and log-rank tests were used to assess survival differences,

with the same analysis applied to validate the prognostic model in

the GSE72094 dataset.

Nomogram development and

validation

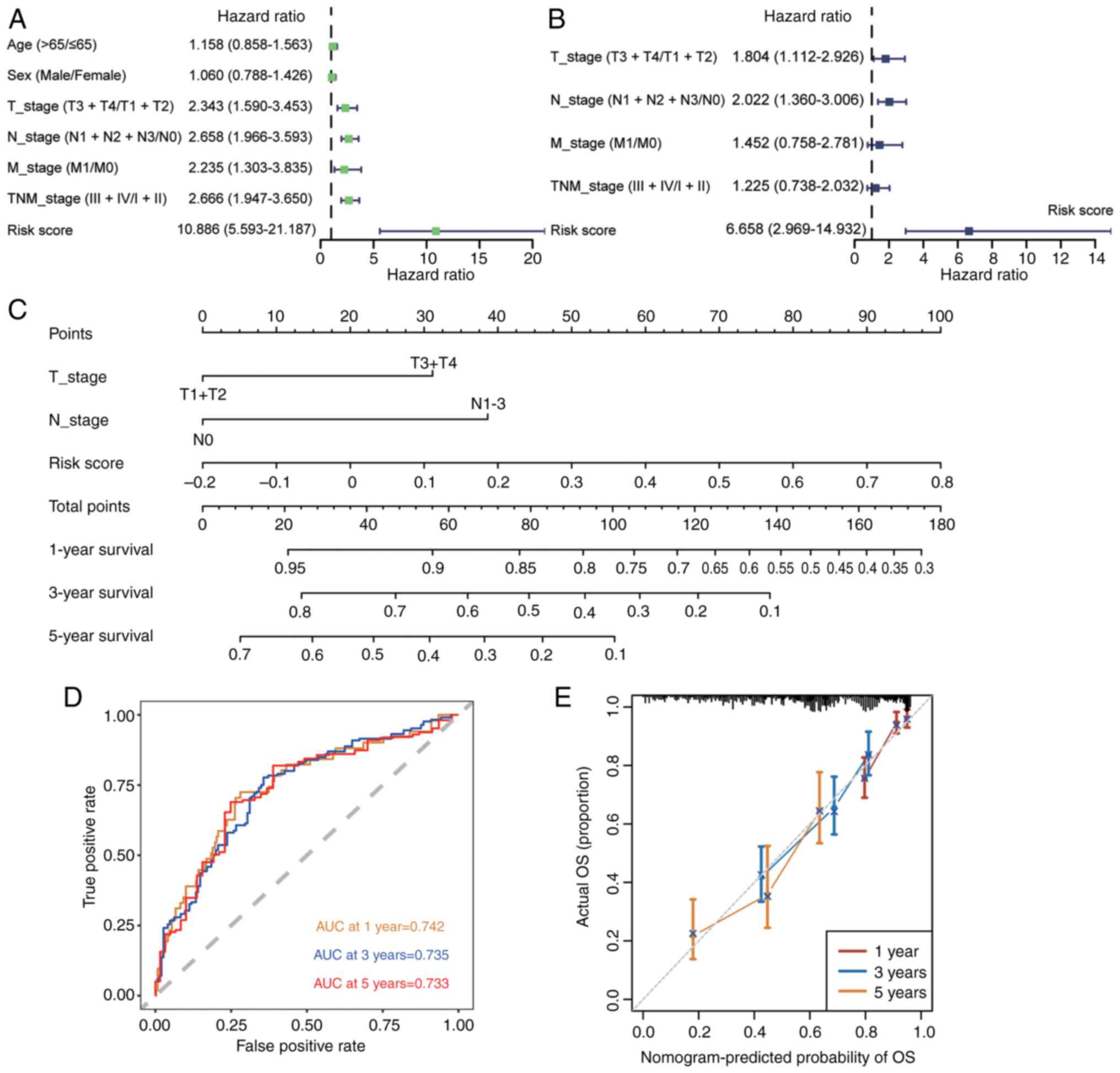

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

were conducted using R project to assess the independence of the

risk index from traditional clinical features. A nomogram was

created to visually represent the significant risk index

(P<0.05) alongside other risk factors. Calibration curves and

time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves were

generated to evaluate the prognostic predictive power of the

nomogram at various time points.

Analysis of tumor mutation burden

(TMB)

Somatic mutation data for LUAD cases were sourced

from TCGA database, with TMB calculated by quantifying somatic

non-synonymous mutations within defined genomic regions. The

‘maftools_2.24.0’ R package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/vignettes/maftools/inst/doc/maftools.html)

was used to analyze the correlation between risk scores and TMB

using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Prediction of immunotherapy and

chemotherapy response

The response of solid tumors to treatment with

immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) was predicted using the Tumor

Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu) algorithm, which

evaluates immune cell infiltration and dysfunction levels (22). The TIDE score for each patient with

LUAD (from TCGA dataset) was calculated based on their expression

profile, with higher TIDE scores indicating an increased potential

for ICI resistance. Additionally, the ‘pRRophetic_0.5’ R package

(https://github.com/paulgeeleher/pRRophetic2) was

employed to estimate the half maximal inhibitory concentration

values for various chemotherapy agents in patients with LUAD (from

TCGA dataset).

Cell culture

Two human LUAD cell lines, A549 and NCI-H1975, were

purchased from Wuhan Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd. A549 cells

were cultured in F12K medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), while NCI-H1975 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All of the media were

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (NEWZERUM Ltd.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Small interfering (si)RNAs were synthesized by Guangzhou RiboBio

Co., Ltd. with the following sequences and targets (5′-3′):

Non-targeting siRNA-negative control, antisense strand:

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA, sense strand: CUCCGAACGUGUCUCGUAA;

GJB3-siRNA1, antisense strand: AGACCUUGUACCCACAGCGGG, sense strand:

CGCUGUGGGUACAAGGUCUGC (target: CCCGCUGUGGGUACAAGGUCUGC);

GJB3-siRNA2, antisense strand: AGGACUCGCCCACGCUAGUUU, sense strand:

ACUAGCGUGGGCGAGUCCUGA, (target: AAACUAGCGUGGGCGAGUCCUGA);

GJB3-siRNA3, antisense strand: UGGCGCGGGACCUUGACCGUG, sense strand:

CGGUCAAGGUCCCGCGCCAAG (target: CACGGUCAAGGUCCCGCGCCAAG).

Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and A549 and

NCI-H1975 cells were used for transfection. Briefly, when the cell

confluence was 30–50%, Opti-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), 10 nm siRNA and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent were

successively added to a sterile microcentrifuge tube, gently mixed

and incubated for 20 min at room temperature (25°C). After 20 min,

the transfection complexes were successively added to the cell

culture dishes, gently mixed and placed in the cell incubator for 6

h at 37°C. Subsequent experiments were performed 48 h after

transfection.

Western blotting

After transfection, the cells were lysed with RIPA

buffer (Merck KGaA) containing protease inhibitors (Merck KGaA).

Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA kit (Nanjing

KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.), and proteins (30 µg/lane) were separated

by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels. Following transfer to PVDF membranes

(Merck KGaA), protein blocking was carried out with 5% skim milk at

room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were then incubated with

primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibody

incubation at room temperature for 1 h. Blots were detected using

Ultra-sensitive ECL chemiluminescent substrate (cat. no. BL523B;

Biosharp Life Sciences) and images were captured with a Tanon 5200

system (Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.). The following

antibodies were used for western blotting: GJB3 polyclonal antibody

(cat. no. 12880-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), E-cadherin

polyclonal antibody (cat. no. 20874-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

N-cadherin polyclonal antibody (cat. no. 22018-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), vimentin polyclonal antibody (cat. no. 10366-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), Snail1 polyclonal antibody (cat. no.

13099-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), β-actin recombinant antibody

(cat. no. 81115-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and Goat Anti-Rabbit

IgG H&L antibody (cat. no. BF03008; Biodragon).

Cell viability and proliferation

assays

Cell viability was evaluated using the Cell Counting

Kit (CCK)-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.). Cells were seeded in

96-well plates at 1,000 cells/well and cultured in a 5%

CO2 incubator at 37°C. After 6 h, the cells adhered to

the surface of the plates, and measurements at this time were

considered 0-h data. Subsequently, CCK-8 values were measured every

24 h, and the data at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h time points were

analyzed and plotted. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and

cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Subsequently,

100 µl complete medium containing 10% CCK-8 reagent was added to

each well, and incubation was continued for 1 h. Absorbance at

OD450 was measured using the MD SpectraMax Plus 384

(Molecular Devices, Inc.).

On day 5 of culture, cell proliferation was assessed

using the Click-iT EdU-488 Cell Proliferation Detection Kit (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), with 1 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 and 10

µM EdU used for detection. EdU staining experiments were performed

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Images were captured

using a Nikon ECLIPSE Ti-2 fluorescence microscope (Nikon

Corporation), with excitation/emission wavelengths of 346/460 nm

for Hoechst and 491/516 nm for EdU.

Colony formation assay

For colony formation assays, cells were seeded in

6-well plates at 1,000 cells/well and cultured in a 5%

CO2 incubator at 37°C, with the medium changed every 3

days. After 2 weeks, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at

room temperature for 60 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room temperature for 5

min. The colonies were rinsed with tap water, dried and images were

captured using a digital camera. The data were statistically

analyzed according to the area of crystal violet staining.

Migration and invasion assays

Cell migration and invasion were assessed using

24-well Transwell Tissue Culture Plate Inserts (pore size, 8.0 µm)

(Guangzhou Jet Bio-Filtration Co., Ltd.). For the migration assay,

2,000 cells/well were seeded in the upper chamber of an uncoated

Transwell insert, whereas for the invasion assay, the upper chamber

was coated with VitroGel™ 3D hydrogel (cat. no. VHM01;

Shanghai XP Biomed Ltd.) at room temperature for 10–15 min. The

cells were seeded in the upper chamber in serum-free medium,

whereas the lower chamber contained complete medium; the cells were

cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. After 24 h of

incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 60 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room

temperature for 5 min. After rinsing with tap water and drying,

images were captured using Nikon ECLIPSE Ti-2 light microscope

channel (Nikon Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and image processing were performed

using R software (version 4.1.3) (https://www.r-project.org/) and GraphPad Prism 9

(Dotmatics). Differences between continuous variables were analyzed

using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, while categorical variables were

assessed using the χ2 test. Survival analysis was

conducted using the log-rank test. Spearman's rank correlation was

applied for correlation analysis. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Features of cholesterol metabolism in

LUAD identified by consensus clustering

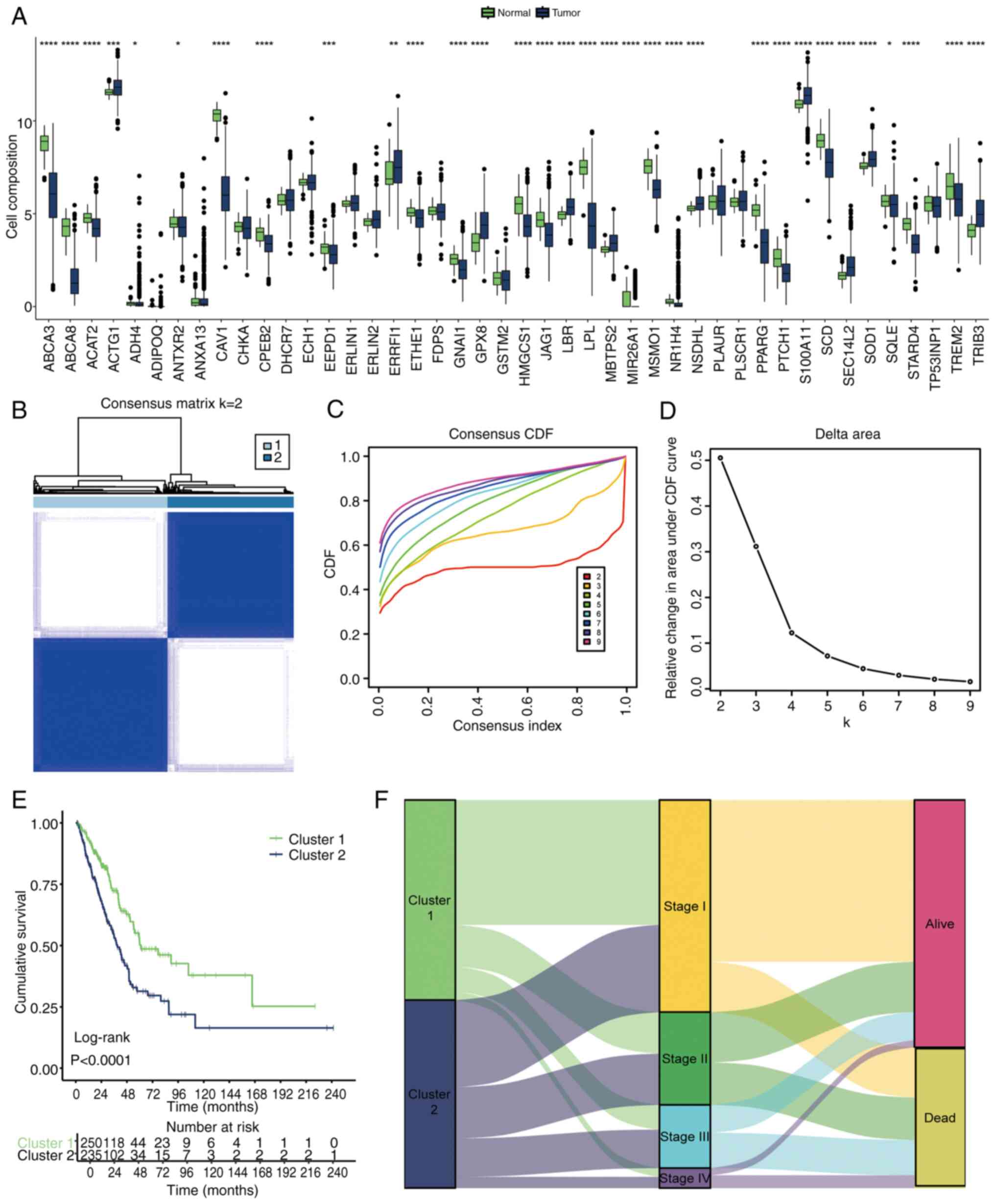

Univariate Cox regression analysis was performed on

158 CMRGs, revealing that 44 of these genes were significantly

associated with prognosis in LUAD (Table SI). Most of these 44 genes

exhibited marked differential expression between LUAD and normal

tissues (Fig. 1A). These 44 genes

were further used to classify LUAD into two distinct cholesterol

metabolism clusters based on their expression patterns (Fig. 1B). This clustering was validated by

observing relative changes in the CDF curves (Fig. 1C) and the area under the curve

(AUC) of CDF curves (Fig. 1D),

with the optimal division (k=2) indicating the ideal number of

clusters. When k=2, the delta area of CDF began to markedly

decrease, thus choosing k=2 gave the best clustering effect

(Fig. 1C and D). Survival analysis

showed a significant difference in prognosis between the two

clusters (Fig. 1E), with the

Sankey diagram highlighting that cluster 1 contained more patients

with lower Tumor-Node-Metastasis stages (23) and a better prognosis (Fig. 1F).

Potential functional pathways

analysis

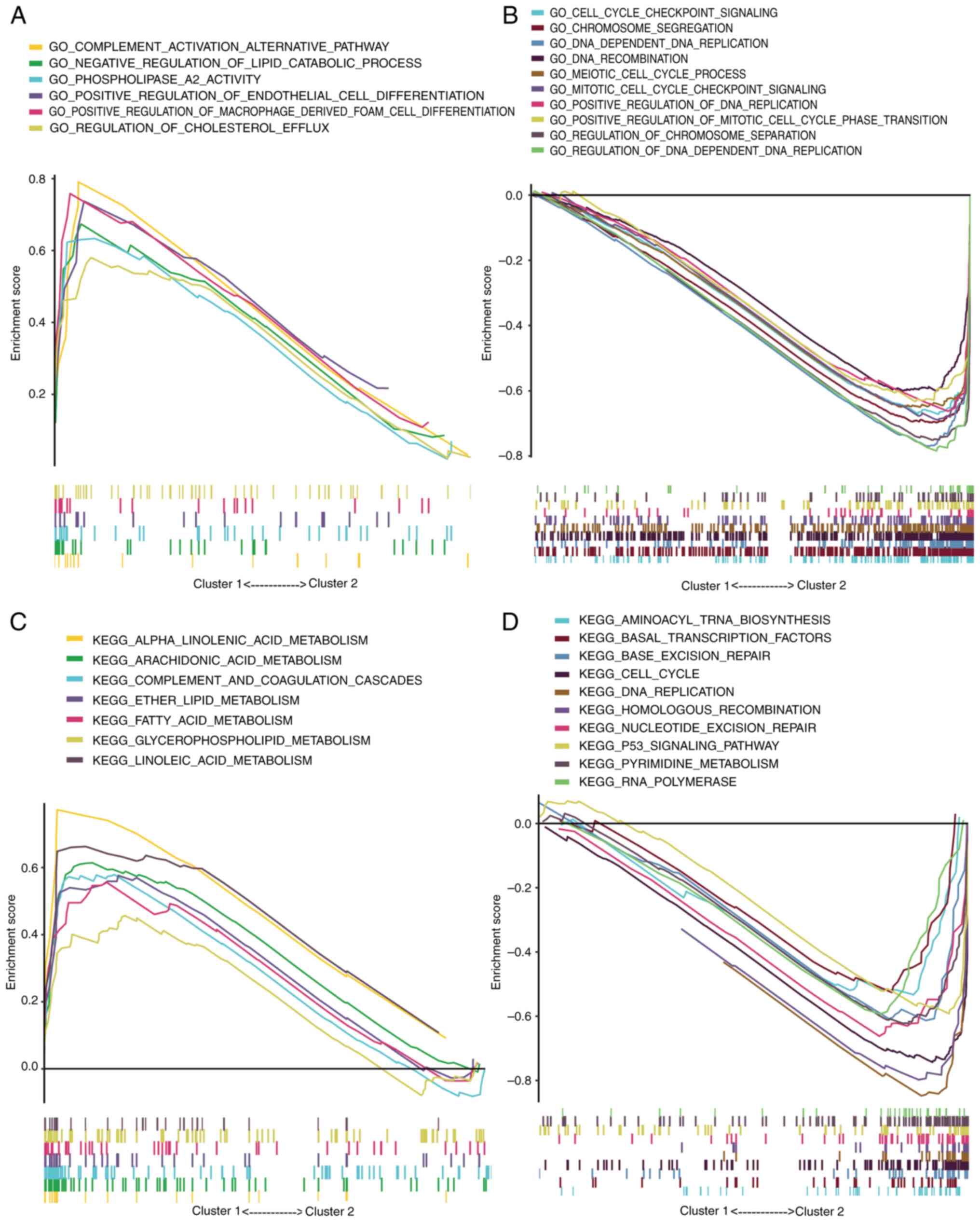

GSEA of Gene Ontology terms revealed that cluster 1

was primarily involved in ‘POSITIVE REGULATION OF ENDOTHELIAL CELL

DIFFERENTIATION’, ‘REGULATION OF CHOLESTEROL EFFLUX’ and ‘NEGATIVE

REGULATION OF LIPID CATABOLIC PROCESS’ (Fig. 2A). Given that enhanced cholesterol

metabolism in tumors is associated with poor prognosis (24), these processes in cluster 1, which

inhibit cholesterol metabolism and reduce the enrichment of

cholesterol metabolites, were linked to a more favorable prognosis.

Conversely, cluster 2 exhibited significant enrichment in processes

such as ‘CELL CYCLE CHECKPOINT SIGNALING’, ‘MEIOTIC CELL CYCLE

PROCESS’, ‘MITOTIC CELL CYCLE CHECKPOINT SIGNALING’, ‘DNA DEPENDENT

DNA REPLICATION’ and ‘DNA RECOMBINATION’, contributing to

accelerated tumor progression (Fig.

2B). These findings were corroborated by Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes pathway analysis (Fig. 2C and D).

Immune infiltration analysis

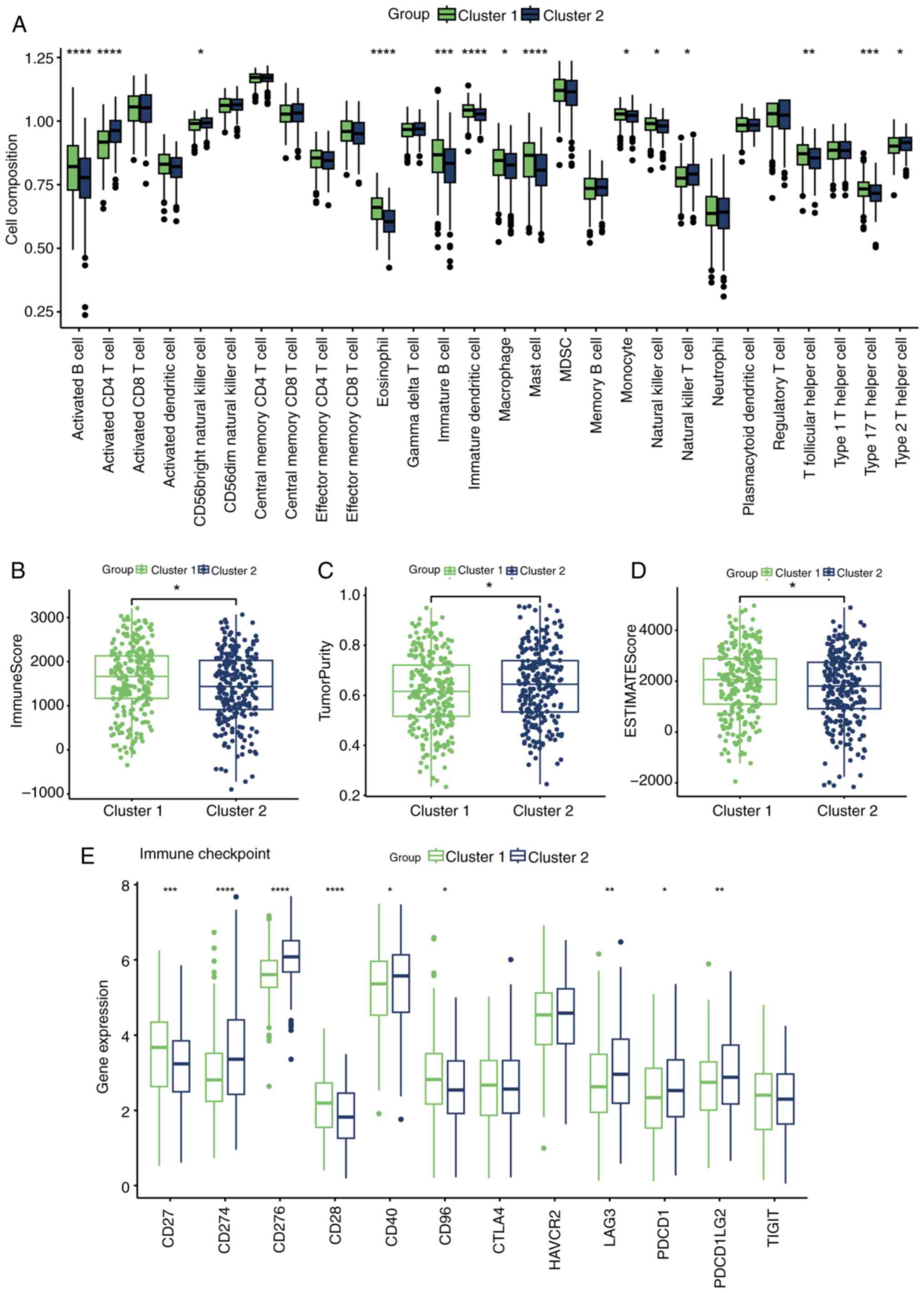

Cholesterol metabolism reprogramming has been shown

to be significantly associated with the formation of an

immunosuppressive microenvironment (6). To investigate this further, the

infiltration of 28 immune cell types was assessed across the

clusters. Cluster 1, with a better prognosis, exhibited more

abundant immune cell infiltration (Fig. 3A), with the majority of these cells

having antitumor effects, such as B cells, macrophages, mast cells,

natural killer cells, T follicular helper cells and type 17 T

helper cells (25). Additionally,

the ESTIMATE algorithm analysis confirmed the higher levels of

immune cell infiltration in cluster 1 (Fig. 3B-D). Furthermore, the expression of

immunosuppressive checkpoints is known to be associated with

immunotherapy responses (26), and

most immunosuppressive checkpoints commonly targeted in clinical

practice were more closely associated with cluster 2, such as

CD274, CD276, LAG3, PDCD1 and PDCD1LG2 (Fig. 3E).

Construction and validation of CMRG

signature

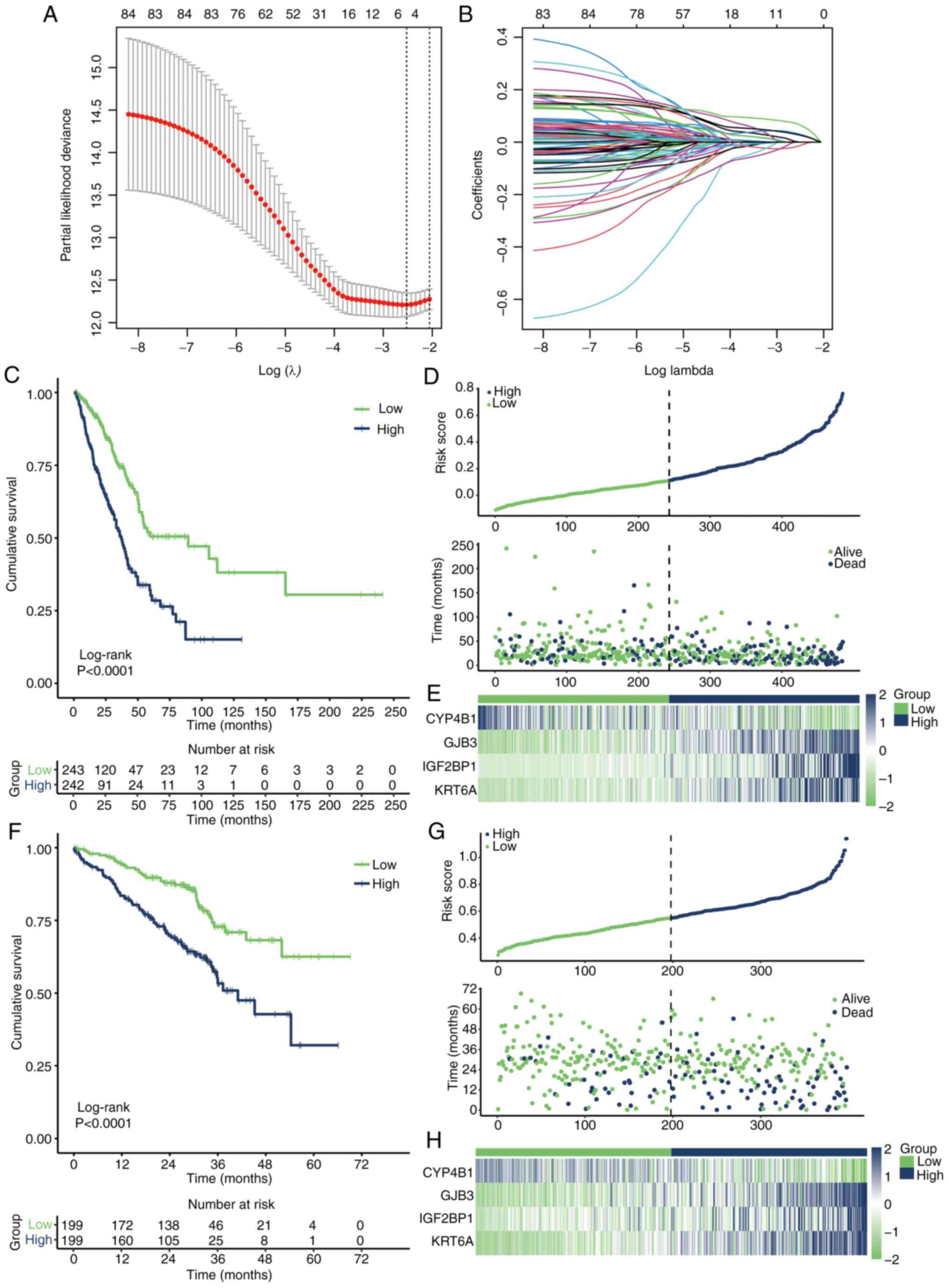

Limma differential analysis identified 124

differentially expressed genes between cluster 1 and cluster 2.

Univariate Cox regression identified 85 genes associated with

prognosis (Table SII). Using the

optimal λ value (Fig. 4A and B),

four key genes: CYP4B1, GJB3, IGF2BP1 and KRT6A, were identified as

significantly influencing the prognosis of the two clusters. The

risk score for each patient was calculated using the following

formula: Risk score=CYP4B1 × −0.01406345 + GJB3 × 0.03109533 +

IGF2BP1 × 0.06671392 + KRT6A × 0.02723521. This model effectively

distinguished patient prognoses in TCGA-LUAD cohort (Fig. 4C). The risk factor distribution

graph demonstrated a higher mortality rate in the high-risk group

(Fig. 4D), and the heatmap

illustrated the distribution of the four key genes across different

patients (Fig. 4E). Applying the

same risk score formula to the GSE72094 dataset yielded similar

results (Fig. 4F-H), further

validating the effectiveness of the prognostic model.

Construction and validation of the

nomogram

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

of the key features affecting prognosis found that CMRG risk

signature was an independent prognostic risk factor (Fig. 5A and B). Based on the CMRG risk

signature and clinical characteristics, a nomogram prediction model

was constructed (Fig. 5C). The AUC

values for 1-, 3- and 5-year predictions were 0.742, 0.735 and

0.733, respectively (Fig. 5D). In

addition, the prediction results of the nomogram closely aligned

with the actual outcomes (Fig.

5E).

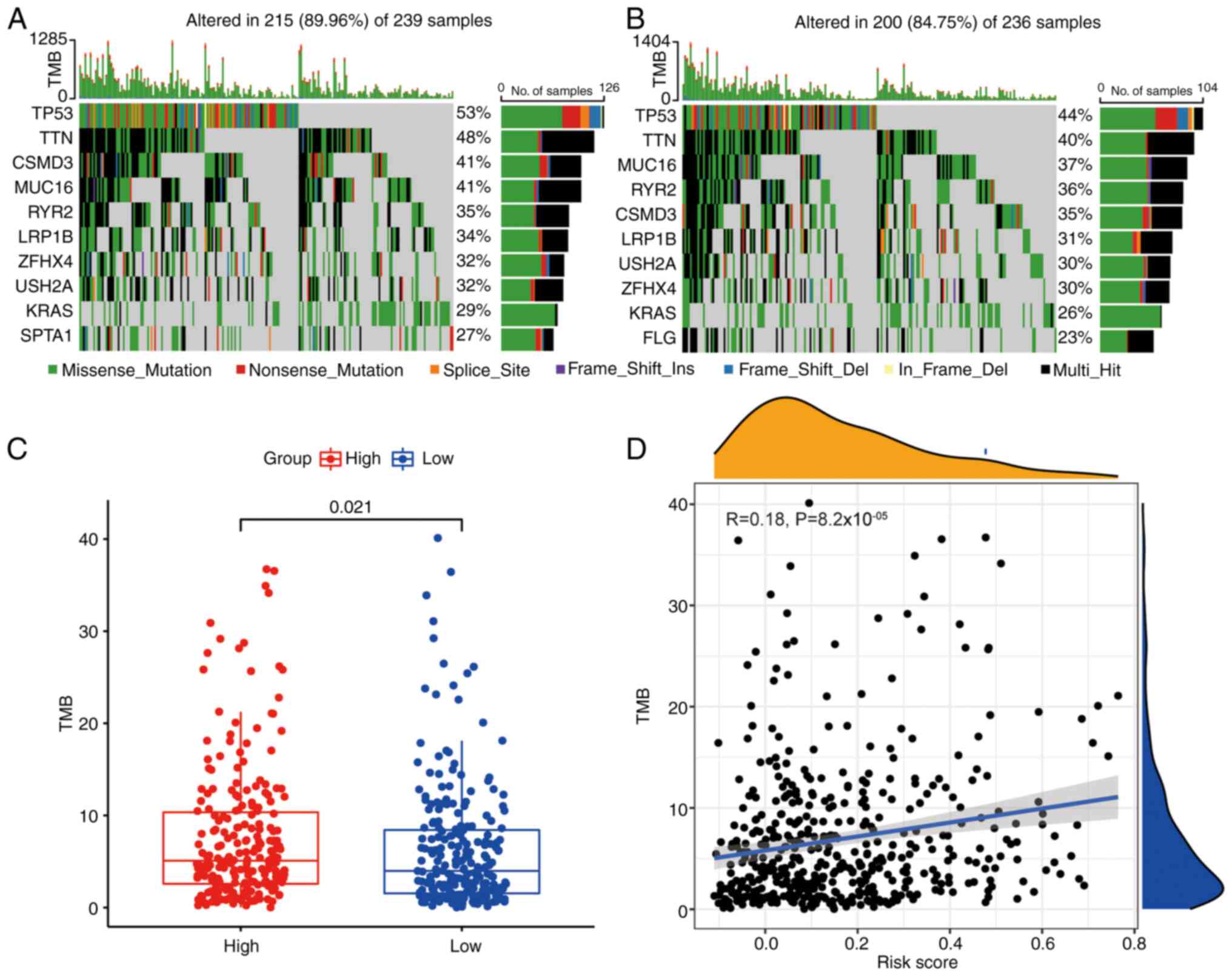

Analysis of TMB

Gene mutations are critical factors influencing

tumor prognosis (27). TMB

analysis of patients in different risk groups showed that most of

the top 10 mutated genes overlapped between the two groups

(Fig. 6A and B), but mutation

incidence was higher in the high-risk group (Fig. 6C). In addition, a low positive

association was confirmed between risk score and TMB (Fig. 6D).

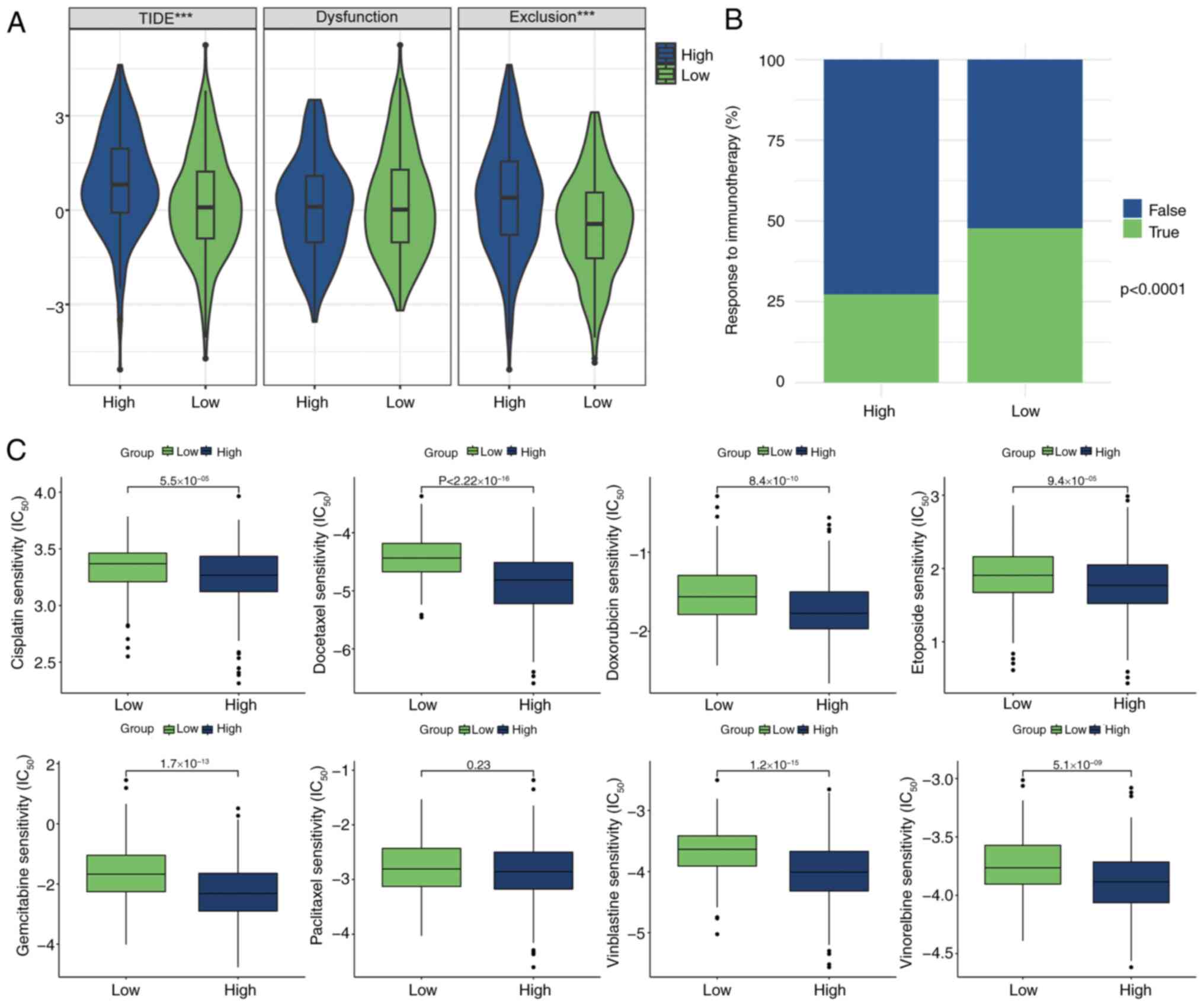

Prediction of immunotherapy and

chemotherapy response

Using the TIDE algorithm, the potential effects of

immunotherapy for patients with LUAD were successfully modeled and

predicted. Notably, high-risk patients exhibited higher exclusion

scores and TIDE values, while there was no significant difference

in dysfunction scores (Fig. 7A),

indicating a greater likelihood of drug resistance during

immunotherapy compared with low-risk patients. Further analysis

revealed that the percentage of low-risk patients responding

positively to immunotherapy was significantly higher than that of

high-risk patients (Fig. 7B),

providing valuable insights for clinical decision-making.

Additionally, the sensitivity of various chemotherapeutic agents

within the patient cohort was assessed. Multiple chemotherapy

drugs, such as cisplatin, docetaxel and doxorubicin, showed lower

half-maximal inhibitory concentration values in the high-risk

group, indicating that high-risk patients were more likely to

benefit from these chemotherapy drugs (Fig. 7C), offering an expanded

understanding of treatment options and providing a scientific

foundation for personalized treatment strategies.

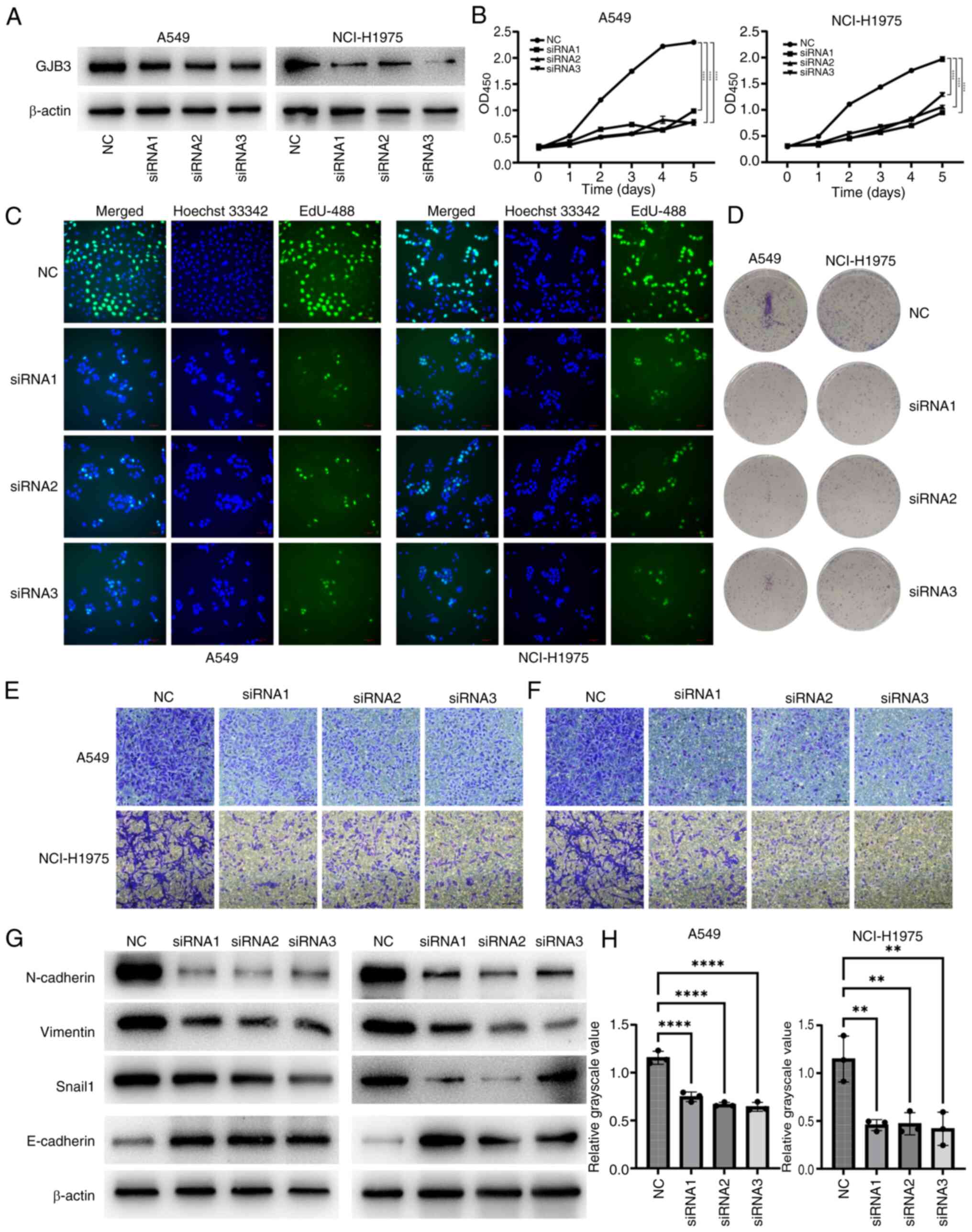

GJB3 promotes the proliferation,

invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of LUAD

Bioinformatics analysis revealed that GJB3 was

highly expressed in tumor tissues and functioned as an oncogene

(Table SII). This was confirmed

through in vitro validation. siRNA-mediated knockdown of

GJB3 expression in A549 and NCI-H1975 cells (Fig. 8A and H) resulted in significantly

reduced cell viability (Fig. 8B).

In addition, EdU staining and colony formation assays showed that

GJB3 knockdown decreased the proliferative capacity of both A549

and NCI-H1975 cells (Fig. 8C and

D, and S1). Transwell assays

further demonstrated that GJB3 knockdown inhibited the migration

and invasion of these cells (Fig. 8E

and F). Given that GJB3 encodes a key member of the connexin

gene family (28), its alteration

might impact EMT. Further examination revealed that GJB3 knockdown

downregulated the expression levels of vimentin, Snail1 and

N-cadherin, while upregulating E-cadherin levels in A549 and

NCI-H1975 cells (Fig. 8G), thus

indicating that GJB3 knockdown inhibited the EMT process in these

cell lines.

Discussion

The treatment of NSCLC faces notable challenges,

including treatment resistance and the need for personalized

therapies. Although traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy

remain essential components of NSCLC management, innovative

treatment strategies have emerged in recent years (29). Immunotherapy, such as

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, one of the most promising advancements,

has demonstrated marked therapeutic effects and survival benefits

by stimulating the immune system of patients to target and

eliminate cancer cells (30). By

contrast, targeted therapies, such as EGFR-tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (TKIs), ALK-TKIs and entrectinib, offer more tailored

treatment options by focusing on specific molecular markers on

tumor cells, enabling precise intervention. By identifying and

targeting these markers with specific drugs, targeted therapies

enhance treatment efficacy, improve patient quality of life and

minimize side effects (31–33).

Furthermore, genomics-guided therapy represents a new frontier in

personalized treatment for NSCLC. By analyzing the genetic profile

of tumors, this approach provides deeper insights into the genetic

characteristics, mutations and potential resistance mechanisms of

the tumor, enabling the development of more precise and effective

treatment strategies (34). The

combination of immunotherapy and targeted therapies has further

advanced NSCLC treatment, leveraging the synergistic effects of

both approaches to improve therapeutic outcomes while minimizing

adverse effects, thus offering patients greater survival benefits

and a better overall treatment experience (35).

Cholesterol serves a pivotal role in maintaining

cellular homeostasis (36). Due to

the limited availability of nutrients in local tissues, tumors

often experience relative nutrient deficiencies alongside the

accumulation of metabolic waste products (37). In response to these adverse

conditions, tumors undergo metabolic reprogramming to adapt

(38). Preclinical studies have

shown that inhibiting cholesterol synthesis can restrict tumor

progression (39,40), and promising results have been

reported from combining statins with other treatment modalities

(41,42). Identifying key molecules involved

in cholesterol metabolism and developing targeted drugs against

them are critical steps in advancing treatment for LUAD.

Cholesterol metabolism influences both tumor growth

and the immune microenvironment (43), indicating a complex crosstalk

between cholesterol metabolic status and the TME. Two distinct

clusters with different cholesterol metabolism profiles were

identified in the present study, with cluster 1 exhibiting richer

immune cell infiltration, which helps explain the prognostic

differences in patients with LUAD. Given the strong association

between cholesterol metabolism and prognosis in LUAD, a prognostic

model based on cholesterol metabolism was developed, involving

CYP4B1, GJB3, IGF2BP1 and KRT6A. CYP4B1, a member of the cytochrome

P450 enzyme superfamily, serves a key role in cholesterol and

derivative synthesis. Its elevated expression in bladder cancer has

been linked to an increased risk of the disease (44). IGF2BP1 influences tumor development

and therapeutic responses primarily by binding to mRNAs, regulating

their stability and translation (45). Müller et al (46) demonstrated that IGF2BP1 promotes

SRF expression in an m6A-dependent manner, driving tumor growth and

invasion. Additionally, Zhang et al (47) showed that IGF2BP1 overexpression

accelerates the malignant progression of endometrial cancer through

m6A methylation. Together, these studies highlight the importance

of IGF2BP1 in understanding cancer progression. KRT6A is positively

associated with both T-stage and N-stage in LUAD, and its knockdown

inhibits cell proliferation, invasion and the EMT process in LUAD

(48). Furthermore, GJB3 has been

shown to be markedly upregulated in the liver metastases of

pancreatic cancer, with overexpression enhancing the accumulation

of tumor-associated neutrophils and promoting liver metastasis

(49). The current study focused

on GJB3, which is a member of the cell junction protein family.

According to a previous report, high cholesterol metabolism can

affect cell adhesion and promote tumor metastasis (50), and GJB3 may have an important role

in this process. To further investigate its function, in

vitro experiments were conducted, revealing that GJB3 knockdown

inhibited the proliferative ability of LUAD cells, consistent with

the results from GSEA. Additionally, GJB3 knockdown suppressed the

migration and invasion of LUAD cells and reduced the expression of

EMT-related proteins. These findings suggested that GJB3 may serve

a critical role in LUAD progression and could serve as a potential

therapeutic target.

Cholesterol metabolism influences the TME and may

significantly affect the efficacy of immunotherapy (51). The CMRG score constructed in the

current study suggested that low-risk patients exhibited higher

response rates to immune checkpoint therapy, whereas high-risk

patients were predicted to show a better chemotherapy response.

This highlights new perspectives for the precision treatment of

patients with LUAD.

There are some limitations in the present study: The

sequencing data comes from previous patients, and the

characteristics of cholesterol metabolism were only studied in TCGA

and GSE72094 datasets. It is necessary to conduct larger

prospective studies to further confirm the effectiveness of the

prognostic model. Second, the cancer-promoting ability of GJB3 in

LUAD needs further validation in animals. Notably, the mechanism by

which GJB3 promotes the progression of LUAD by affecting

cholesterol metabolism needs to be further studied through

multi-omics, and in vitro and in vivo

experiments.

In conclusion, cholesterol metabolic status is

closely associated with the prognosis, TME and treatment response

in patients with LUAD. The cholesterol metabolism-related

prognostic model developed in the current study may not only

predict patient outcomes but could also provide valuable insights

into personalized treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2019A1515011601).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QY, WC and JW designed and supervised the

experiments. WC and WW performed the bioinformatics analysis. LG

and DL performed the experiments. QY and JY analyzed and

interpreted the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

QY, JW and WC reviewed the manuscript. LG and WC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 70:7–30. 2020.

|

|

2

|

Berg CD, Schiller JH, Boffetta P, Cai J,

Connolly C, Kerpel-Fronius A, Kitts AB, Lam DCL, Mohan A, Myers R,

et al: Air pollution and lung cancer: A review by international

association for the study of lung cancer early detection and

screening committee. J Thorac Oncol. 18:1277–1289. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Akçay S: Deciphering molecular overlaps

between COPD and NSCLC subtypes (LUAD and LUSC): An integrative

bioinformatics study. Medicine (Baltimore). 104:e439062025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF

and Heist RS: Lung cancer. Lancet. 398:535–554. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Mamdani H, Matosevic S, Khalid AB, Durm G

and Jalal SI: Immunotherapy in lung cancer: Current landscape and

future directions. Front Immunol. 13:8236182022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Huang B, Song BL and Xu C: Cholesterol

metabolism in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat

Metab. 2:132–141. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Bakiri L, Hamacher R, Graña O,

Guío-Carrión A, Campos-Olivas R, Martinez L, Dienes HP, Thomsen MK,

Hasenfuss SC and Wagner EF: Liver carcinogenesis by FOS-dependent

inflammation and cholesterol dysregulation. J Exp Med.

214:1387–1409. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang X, Huang Z, Wu Q, Prager BC, Mack SC,

Yang K, Kim LJY, Gimple RC, Shi Y, Lai S, et al: MYC-regulated

mevalonate metabolism maintains brain tumor-initiating cells.

Cancer Res. 77:4947–4960. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kondo A, Yamamoto S, Nakaki R, Shimamura

T, Hamakubo T, Sakai J, Kodama T, Yoshida T, Aburatani H and Osawa

T: Extracellular acidic pH activates the sterol regulatory

element-binding protein 2 to promote tumor progression. Cell Rep.

18:2228–2242. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

He M, Zhang W, Dong Y, Wang L, Fang T,

Tang W, Lv B, Chen G, Yang B, Huang P and Xia J: Pro-inflammation

NF-κB signaling triggers a positive feedback via enhancing

cholesterol accumulation in liver cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 36:152017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kloudova A, Guengerich FP and Soucek P:

The role of oxysterols in human cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab.

28:485–496. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Raccosta L, Fontana R, Maggioni D,

Lanterna C, Villablanca EJ, Paniccia A, Musumeci A, Chiricozzi E,

Trincavelli ML, Daniele S, et al: The oxysterol-CXCR2 axis plays a

key role in the recruitment of tumor-promoting neutrophils. J Exp

Med. 210:1711–1728. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Goossens P, Rodriguez-Vita J, Etzerodt A,

Masse M, Rastoin O, Gouirand V, Ulas T, Papantonopoulou O, Van Eck

M, Auphan-Anezin N, et al: Membrane cholesterol efflux drives

tumor-associated macrophage reprogramming and tumor progression.

Cell Metab. 29:1376–1389.e4. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kopecka J, Trouillas P, Gašparović AČ,

Gazzano E, Assaraf YG and Riganti C: Phospholipids and cholesterol:

Inducers of cancer multidrug resistance and therapeutic targets.

Drug Resist Updat. 49:1006702020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Schabath MB, Welsh EA, Fulp WJ, Chen L,

Teer JK, Thompson ZJ, Engel BE, Xie M, Berglund AE, Creelan BC, et

al: Differential association of STK11 and TP53 with KRAS

mutation-associated gene expression, proliferation and immune

surveillance in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 35:3209–3216. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Castanza AS, Recla JM, Eby D,

Thorvaldsdottir H, Bult CJ and Mesirov JP: Extending support for

mouse data in the molecular signatures database (MSigDB). Nat

Methods. 20:1619–1620. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wilkerson MD and Hayes DN:

ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence

assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 26:1572–1573. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK,

Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub

TR, Lander ES and Mesirov JP: Gene set enrichment analysis: A

knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression

profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:15545–15550. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Barbie DA, Tamayo P, Boehm JS, Kim SY,

Moody SE, Dunn IF, Schinzel AC, Sandy P, Meylan E, Scholl C, et al:

Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven

cancers require TBK1. Nature. 462:108–112. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martinez E,

Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Treviño V, Shen H, Laird PW,

Levine DA, et al: Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune

cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 4:26122013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X,

Li Z, Traugh N, Bu X, Li B, et al: Signatures of T cell dysfunction

and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med.

24:1550–1558. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Rami-Porta R, Nishimura KK, Giroux DJ,

Detterbeck F, Cardillo G, Edwards JG, Fong KM, Giuliani M, Huang J,

Kernstine KH Sr, et al: The international association for the study

of lung cancer lung cancer staging project: Proposals for revision

of the TNM stage groups in the forthcoming (ninth) edition of the

TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 19:1007–1027.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ehmsen S, Pedersen MH, Wang G, Terp MG,

Arslanagic A, Hood BL, Conrads TP, Leth-Larsen R and Ditzel HJ:

Increased cholesterol biosynthesis is a key characteristic of

breast cancer stem cells influencing patient outcome. Cell Rep.

27:3927–3938.e6. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Turley SJ, Cremasco V and Astarita JL:

Immunological hallmarks of stromal cells in the tumour

microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 15:669–682. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhang Y and Zhang Z: The history and

advances in cancer immunotherapy: Understanding the characteristics

of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic

implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 17:807–821. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Martínez-Jiménez F, Muiños F, Sentís I,

Deu-Pons J, Reyes-Salazar I, Arnedo-Pac C, Mularoni L, Pich O,

Bonet J, Kranas H, et al: A compendium of mutational cancer driver

genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 20:555–572. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Liu J, Wang X, Jiang W, Azoitei A, Eiseler

T, Eckstein M, Hartmann A, Stilgenbauer S, Elati M, Hohwieler M, et

al: Impairment of α-tubulin and F-actin interactions of GJB3

induces aneuploidy in urothelial cells and promotes bladder cancer

cell invasion. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 29:942024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Otano I, Ucero AC, Zugazagoitia J and

Paz-Ares L: At the crossroads of immunotherapy for

oncogene-addicted subsets of NSCLC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:143–159.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Sui H, Ma N, Wang Y, Li H, Liu X, Su Y and

Yang J: Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer:

Toward personalized medicine and combination strategies. J Immunol

Res. 2018:69849482018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Santoni-Rugiu E, Melchior LC, Urbanska EM,

Jakobsen JN, Stricker K, Grauslund M and Sørensen JB: Intrinsic

resistance to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant

non-small cell lung cancer: Differences and similarities with

acquired resistance. Cancers (Basel). 11:9232019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM,

Lin CC, Soo RA, Riely GJ, Ou SI, Clancy JS, Li S, et al: ALK

Resistance mutations and efficacy of lorlatinib in advanced

anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J

Clin Oncol. 37:1370–1379. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Drilon A, Siena S, Dziadziuszko R, Barlesi

F, Krebs MG, Shaw AT, de Braud F, Rolfo C, Ahn MJ, Wolf J, et al:

Entrectinib in ROS1 fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer:

Integrated analysis of three phase 1–2 trials. Lancet Oncol.

21:261–270. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wang Z, Zhang Q, Qi C, Bai Y, Zhao F, Chen

H, Li Z, Wang X, Chen M, Gong J, et al: Combination of AKT1 and

CDH1 mutations predicts primary resistance to immunotherapy in

dMMR/MSI-H gastrointestinal cancer. J Immunother Cancer.

10:e0047032022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wang M, Herbst RS and Boshoff C: Toward

personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer.

Nat Med. 27:1345–1356. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

King RJ, Singh PK and Mehla K: The

cholesterol pathway: Impact on immunity and cancer. Trends Immunol.

43:78–92. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Pavlova NN, Zhu J and Thompson CB: The

hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab.

34:355–377. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hanahan D: Hallmarks of cancer: New

dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12:31–46. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Li J, Liu J, Liang Z, He F, Yang L, Li P,

Jiang Y, Wang B, Zhou C, Wang Y, et al: Simvastatin and

Atorvastatin inhibit DNA replication licensing factor MCM7 and

effectively suppress RB-deficient tumors growth. Cell Death Dis.

8:e26732017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Mullen PJ, Yu R, Longo J, Archer MC and

Penn LZ: The interplay between cell signalling and the mevalonate

pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 16:718–731. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Lee J, Jung KH, Park YS, Ahn JB, Shin SJ,

Im SA, Oh DY, Shin DB, Kim TW, Lee N, et al: Simvastatin plus

irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFIRI) as first-line

chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal patients: A multicenter phase

II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 64:657–663. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Liu JC, Hao WR, Hsu YP, Sung LC, Kao PF,

Lin CF, Wu AT, Yuan KS and Wu SY: Statins dose-dependently exert a

significant chemopreventive effect on colon cancer in patients with

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A population-based cohort

study. Oncotarget. 7:65270–65283. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Liu X, Lv M, Zhang W and Zhan Q:

Dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism in cancer progression.

Oncogene. 42:3289–3302. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Imaoka S, Yoneda Y, Sugimoto T, Hiroi T,

Yamamoto K, Nakatani T and Funae Y: CYP4B1 is a possible risk

factor for bladder cancer in humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

277:776–780. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wang T, Kong S, Tao M and Ju S: The

potential role of RNA N6-methyladenosine in cancer progression. Mol

Cancer. 19:882020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Müller S, Glaß M, Singh AK, Haase J, Bley

N, Fuchs T, Lederer M, Dahl A, Huang H, Chen J, et al: IGF2BP1

promotes SRF-dependent transcription in cancer in a m6A- and

miRNA-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:375–390. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Zhang L, Wan Y, Zhang Z, Jiang Y, Gu Z, Ma

X, Nie S, Yang J, Lang J, Cheng W and Zhu L: IGF2BP1 overexpression

stabilizes PEG10 mRNA in an m6A-dependent manner and promotes

endometrial cancer progression. Theranostics. 11:1100–1114. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Yang B, Zhang W, Zhang M, Wang X, Peng S

and Zhang R: KRT6A promotes EMT and cancer stem cell transformation

in lung adenocarcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

19:15330338209212482020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Huo Y, Zhou Y, Zheng J, Jin G, Tao L, Yao

H, Zhang J, Sun Y, Liu Y and Hu LP: GJB3 promotes pancreatic cancer

liver metastasis by enhancing the polarization and survival of

neutrophil. Front Immunol. 13:9831162022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Mohammadalipour A, Showalter CA, Muturi

HT, Farnoud AM, Najjar SM and Burdick MM: Cholesterol depletion

decreases adhesion of non-small cell lung cancer cells to

E-selectin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 325:C471–C482. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Ngwa VM, Edwards DN, Philip M and Chen J:

Microenvironmental metabolism regulates antitumor immunity. Cancer

Res. 79:4003–4008. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|